?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Literature has established that the alarming female poverty rate is a crucial factor contributing to missing older women in India. Given this, the following research examines the role of an unconditional cash transfer programme (Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme) implemented in India on the household budget share incurred on cereals, pulses, vegetables; fruits and nuts, meat; eggs and fish, milk and milk products when the program recipient is an elderly woman. The paper uses the longitudinal household-level data (2004–05 and 2011–12) released by the India Human Development Survey and utilises a quasi-experimental framework of propensity score matching combined with fixed effects to estimate the effects of the pension on the disaggregated food budget share incurred by the pension recipient households. The findings in this paper suggest that women’s access to pension has a positive effect on budget share allocated on vegetables, fruits and nuts and meat, fish and eggs. The positive effects persist for continuous program recipients. Further, to address any concerns on endogeneity, an instrumental variable strategy has been used. This paper provides evidence that female pension recipient households in India do move towards nutrient-rich food items.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

There are two economic rationales behind cash transfer programmes targeted at women. The first rationale is based on the non-unitary household model that suggests expenditure allocations made by men and women are different. The standard unitary household model assumes that a household is a single entity and that members within the household are altruistic. The unitary model assumes that members of a household pool their income together. This implies that additional non-labour income would bring in the same welfare effect, irrespective of the programme recipient’s gender. The assumption of the income pooling hypothesis has been rejected by Thomas (Citation1993), Attanasio and Lechene (Citation2002), de Carvalho Filho (Citation2012), Ponczek (Citation2011), Duflo (Citation2003), Bergolo and Galván (Citation2018). Cash transfers targeted at women tend to increase the bargaining power of women, and this favours consumption expenditure decisions favoured by them (Armand et al., Citation2020; Adato, De la Briere, Mindek, & Quisumbing, Citation2000; Bergolo & Galván, Citation2018; De Brauw, Gilligan, Hoddinott, & Roy, Citation2014; Holmes & Jones, Citation2010; Rubalcava, Teruel, and Thomas, Citation2009).

The second economic rationale for transfers to be targeted at women is that they are economically vulnerable, more in the context of developing countries like India. Calvi (Citation2020) argues that in the Indian context, women at all ages are poorer compared to men, but the economic vulnerability increases several folds for women at an older age. A report by the UN Population Fund India (Citation2017) highlights that older women are more financially vulnerable than men. The work by Kalavar and Jamuna (Citation2011) highlighted an increase in the potential of disability among elderly women in India. Roy and Chaudhuri (Citation2008) found that older women in India report declining health status, lower healthcare utilisation and prevalence of disabilities compared to men. The gender differential in health outcomes can be explained through gender differences in socioeconomic status and the lack of financial empowerment of women. Anderson & Ray’s work (Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2019) has highlighted on excess female mortality at an older age in India. Increased son-preference is a vital factor responsible for younger missing women but, for missing women at the post-reproductive age, women’s reduced bargaining power is cited as an essential factor as this results in poverty among older women Calvi (Citation2020).Footnote1 The estimates provided by the author show that poverty rates among women of post-reproductive age are 80% higher than those recorded for men. There has been increasing work done by many NGOs which emphasises the problems of increased poverty and discrimination faced by elderly women and they also suggest the need to have income security for elderly women (Agewell foundation, and HelpAge India).Footnote2

In absolute terms, the number of elderly in India (60 years and above) has increased from 20.3 million in 1950 to more than 116 million recently (Agarwal, Lubet, Mitgang, Mohanty, & Bloom, Citation2020). The UN Population Division has projected the proportion of elderly in the population to increase from 8 per cent in 2010 to 19 percent in 2050.Footnote3 The elderly population in India is projected to be about 179 million in 2026, which makes social security issues focussed on elderly necessary (Chopra & Pudussery, Citation2014). Older women, compared to older men, are more marginalised and face higher vulnerability in India (Gopal, Citation2006). Evidence indicates from state surveys, over 59% of older women do not receive personal income or pensions in India, of this 42% are poor (Giridhar, Subaiya, & Verma, Citation2015). This clearly underlines the need to scale up social pension programs, still to precede, it is essential to understand the impact of the current social security arrangement on the economic vulnerability faced by elderly women.

The recent debates on old-age pensions and other cash transfer programs are focused heavily on the income pooling hypothesis, and this essentially tests the welfare effects of cash transfer between men and women. Less attention has been given to the welfare effects of the program centred on female program recipients. The work by Schady and Rosero (Citation2008) and Aker, Boumnijel, McClelland, and Tierney (Citation2016) has compared the welfare effects of unconditional cash transfer programs between women program recipients and women non-program recipients to understand the welfare effects generated among program participants. Aker et al. (Citation2016) studied the effects of electronic transfers in delivering an unconditional cash transfer program (Zap) in Niger. The programme identified women as primary recipients. The research ascertained that Zap improved dietary diversity by 9–16 per cent. Schady and Rosero (Citation2008) studied the impact of Bono de Desarrollo Humano (BDH), an unconditional cash transfer programme given to women in Ecuador, and estimated its impact on food expenditure.Footnote4 The transfer from BDH constituted only 10 per cent of the median household income. Their empirical findings provide evidence that women’s programme participation increases the share of spending incurred on food, compared with households where women did not participate in the programme.

Barrientos, Gorman, and Heslop (Citation2003) have highlighted that in developing countries poor people perceive older and widowed women as the poorest. IGNOAPS female program recipients constitute older women who also subsumes widows and destitute. Consequently, IGNOAPS encompasses a wider vulnerable group, compared to the widow's pension program that excludes older women who are not widowed. For this reason, old age pension covers a larger proportion of people compared to the widow’s pension program. Dutta, Howes, and Murgai (Citation2010) have pointed out that six million people in India receive an old-age pension compared to three million receiving widow’s pension.

The recent Sustainable Development Goals Equation(1)(1)

(1) recognise the need to alleviate poverty in all forms everywhere. This further emphasises the need to focus on the impact of poverty alleviation programs on older women. In this context, the following research aims to study the impact of the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Program (IGNOAPS), an unconditional cash transfer program given to the elderly in India, on elderly women’s household poverty. Household poverty is assessed through the budget share allocation on disaggregated food items. I have examined the impact of the program on the budget share allocation disaggregated food items including cereals, pulses, vegetables; fruits and nuts, meat; eggs and fish, milk and milk products. The disaggregated items shed light on the consumption habits of the pension recipients. It gauges if pension encourages households to consume nutritious and higher valued food items.

There have been previous empirical studies on IGNOAPS (Garroway, Citation2013; Kaushal, Citation2014; Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020) in which the authors examined the impact on aggregated welfare indicators. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of elderly women’s participation in IGNOAPS on the disaggregated household food expenditure. The disaggregated consumption expenditure studied here is useful for understanding the micro-welfare effects of the programme. This has policy implications as this sheds information on the change in consumption behaviour with the arrival of the old-age pension program. In this research, I have used the two rounds of household longitudinal data (2004–05 and 2011–12) released by the India Human Development Survey. Propensity score matching (PSM) has been used to construct a valid counterfactual group from the secondary dataset. The constructed control group has similar characteristics with the treatment (IGNOAPS) receiving households. The only difference between the treatment and control group is the women’s participation in IGNOAPS. To circumvent the effects of time-invariant unobservable characteristics such as cultural norms that shape taste and preference on the outcome variables, the method of fixed effects (FE) has been used in the PSM setting. We also examine the correlation between different treatment types received on the consumption outcomes. The different treatment types include a household that received the program in both rounds, households that has a pensioner only in 2011 – rounds or households with a pensioner only in the 2004–05 rounds. PSM-FE examines the effect of gaining a pensioner in either round on the outcome variables. Still, it does not consider the interchangeability of treatment status, whereby the program non-recipient (control group) in the 2004–05 round can constitute a program recipient in the 2011–12 rounds. Considering this, I examine the effect of continuous program recipients, which is households that have received the program in both rounds, on the outcome variables. For this analysis, I exclude households with IGNOAPS recipients in a single round, either 2004–05 or 2011–12.

A Difference in Differences (DID) model has been used in the PSM setting to examine the impact of having a pensioner only in the 2011 – rounds on the outcomes variables. The 2011 rounds also coincide with the program expansion that took place in 2007, where the beneficiary identification mechanism changed from destitute to Below Poverty Line household. All the regression estimates are weighted with the propensity score to address any concern on sample selection bias. To address remaining concerns on endogeneity, an instrumental variable (IV) strategy have been further used.

The empirical findings from PSM-FE model suggest that the IGNOAPS has a positive impact on the food budget share allocation on vegetables; fruits and nuts (26%), meat; eggs and fish (17%). We also find that continuous programme recipients have significantly increased their budget share on pulses; vegetables, fruits and nuts; milk and milk products. Further, there is a strong correlation between the length of exposure to the program and the consumption outcome. The IV estimates also confirm that female program recipients move from high calories and low-nutrient cereals to nutrient-rich food items.

The results from the DID estimates suggest that the expansion of the program in 2011 did not have any significant impact on the outcome variables studied here. The Difference in Differences results reinstates the earlier findings on IGNOAPS where the authors found substantial leakage in the program in 2011–12 rounds which deteriorated the welfare gains from the program (Asri, Citation2019; Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020). The following section gives a brief overview of the program studied here, followed by details of the data in Section 3, and the methodological framework is detailed in Section 4. Section 5 focuses on the empirical findings from this paper, and section 6 discusses the results.

2. Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Programme

The National Social Assistance Program (NSAP) was introduced by the central government of India in 1995 to provide a safety net for the vulnerable sections of society. There were three major components of the scheme: the National Old Age Pension Scheme (NOAPS), National Family Benefit Scheme (NFBS) and National Maternity Benefit Scheme (NMBS). In the initial phase, NOAPS was provided to destitute applicants aged 65 or older, and the Federal government provided Indian National Rupees (INR) 75 to eligible beneficiaries. In 2007, the scheme was renamed the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS). The eligibility criteria used in the scheme changed from someone being destitute to any person who has attained 65 years of age or over and belonging to a below the poverty line household. The scheme was formally launched in 2007. The central assistance to the beneficiaries also increased from INR 75 to INR 200. The second round of change happened in 2011. In a memorandum released by the Ministry of Rural Development in 2011, the age eligibility criterion for the program was reduced from 65 to 60 years. Also, cash transfers to recipients above 80 years of age increased from INR 200 to INR 500 (National Social Assistance Program, Government of India website, Citationn.d.). The central government provides a fixed amount as transfers based on the state poverty line. The state government are requested to top-up in addition to the central government's contributions. There are inter-state variations in the eligibility criteria used and the transfer amount provided program, as some states make a larger contribution compared to others. A detailed discussion of the program is provided by Kaushal (Citation2014).

Besides, the mechanism of pension delivery also varies across states; pensions are disbursed through bank accounts, postal payments, cash payments at the village office and post office (Chopra & Pudussery, Citation2014). Some of the bottlenecks involved in pension implementing process include: delay both at the identification of pensioners and distribution pension payments, and use of a flawed BPL criterion to recognise pensioners (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017). Income from NSAP is the only source of income for some families. Still, the delay in payments, the high transaction cost involved in obtaining the program, exclusion error, lack of clarity with the program eligibility criteria used and leakages are common causes of concerns (Marulasiddappa, Raonka, & Sabhikhi, Citation2014). Similarly, concerns related to inadequate pension benefits, inefficient delivery mechanisms; irregular payment has been raised by Chopra and Pudussery (Citation2014). Despite these weaknesses, the program helps beneficiaries to meet food expenses, basic needs and reduce their economic dependence on other family members and improves other aspects (Bhattacharya, Jos, MEHTA, & Murgai, Citation2015; Gupta, Citation2013). Although the literature provides evidence on beneficiaries improving food consumption, it is crucial to understand which items in food basket is favoured. This helps us to know if pension recipients (female) augment cereal consumption in the food basket or they move towards better-valued food, which remains unanswered.

3. Data

Previous research focusing on the program used data descriptive and qualitative methods for analysis (Chopra & Pudussery, Citation2014; Drèze & Khera, Citation2017; Dutta et al., Citation2010; Gupta, Citation2013; Marulasiddappa et al., Citation2014). There are very few empirical papers on this program (Garroway, Citation2013; Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020; Kaushal, Citation2014). Policy evaluations using rigorous quantitative methods provide insights on if a particular intervention works or not and sheds light on which aspects of the wellbeing is improved. Therefore, in this paper, I have combined matching with fixed effects to evaluate the impact of the program. Besides, I have also used PSM-DID to explore the changes made in the program identification strategy on disaggregated food consumption behaviour. Also, an IV strategy in the matched-fixed effects setting has also been employed to test the robustness of the results. The details of the dataset and the variables used are given below.

I have used the household-level panel data based on India Human Development Survey (IHDS) the survey was conducted in 2004–05 and 2011–12. Both the rounds (2004–05 and 2011–12 rounds) are nationally representative. The 2011–12 rounds re-interviewed 40,018 households (original and split households within the same village) of IHDS-1 survey. The panel data at the household-level have been constructed for 40,018 households which were monitored in both periods (Desai, Sonalde, Reeve Vanneman, and National Council of Applied Economic Research, Citation2010, and Citation2015).

3.1. Definition of the variables and construction

IHDS dataset collected information on the monthly consumption expenditure incurred on different food items. The 2005 price deflator provided in the dataset has been used to convert nominal to real expenditure. The details on the variables used in the study and its construction are in Appendix 1.

Since the dependent variables are aggregated at the household level, a similar household-level measure on the household having a women IGNOAPS recipient has been used. The dataset provides individual-level information on IGNOAPS beneficiary, transfer amount and their sex. The individual-level information has been aggregated at the household level, and a single measure has been developed to identify the beneficiary household.

Appendix 2 presents the descriptive statistics comparing the mean of outcome and the control variables in both rounds between households with women IGNOAPS beneficiaries with no women beneficiaries. Appendix 2 is based on the panel data after matching and weighted by the propensity score. The mean budget share allocation on cereals is higher for non-beneficiaries. Non-beneficiary household, on average, tends to own or cultivate in agricultural land; more likely to live in an urban area; receive more welfare programs. The household head among the non-beneficiaries is more likely to belong to the Muslim religion. In the subsequent section, I have presented the empirical framework used to test if women’s access to IGNOAPS improves the consumption of nutritious food in the household.

4. Empirical framework

4.1. Selection bias and Propensity Score Matching

The IHDS for 2004–05 and 2011–12 rounds provide information on the outcome variables and whether a woman receives IGNOAPS or not. Unlike experimental settings, where the treatment is randomly assigned, in the case of IGNOAPS households self-select themselves into treatment. It is possible that households, where women receive IGNOAPS, are systematically different compared to households where a woman does not receive the program and this result in selection bias, which biases the estimated treatment effect. The method of matching is used to eliminate selection bias arising between the program recipients and non-recipients, and then to estimate the average treatment effects on the treated.

In a propensity score matching model, we remove the systematic difference between the treatment and control group by conditioning the probability of receiving treatment on a broad range of ‘X’ covariates. Rosenbaum and Rubin (Citation1983) have shown that absolute matching is not possible. In the case of high dimensions vector ‘X’ covariates, it is difficult to pair treatment with the control units. The authors suggested pairing treatment with control units based on the probability score generated on ‘X’ covariates (p (X)). However, to use PSM, we need to satisfy two assumptions. The first assumption is balancing property, and the second assumption is unconfoundedness.

Balancing property

This property ensures that the observable characteristics (X) are conditional on the propensity score and the covariates (X) included are independent of treatment status (T). For any given propensity score, the treatment and control group should, on average, look identical (World Bank).Footnote5

Unconfoundedness

This assumption states that the outcome variables () are independent of the treatment status (T). This further means that selection in treatment assignment is dependent only on X covariates included (World Bank).Footnote6

PSM helps to pair participants in the program with matched non-participants. Matching is performed here based on observable characteristics that affect both treatment assignment and the outcome variables (Khandker, Koolwal, & & Samad, Citation2009). In a PSM framework, we model the probability of receiving treatment based on observable characteristics. This addresses selection bias in treatment assignment. The covariate that is used here for constructing propensity score includes the number of women in the household who are 60 years or older, belonging to BPL or Antyodaya (ultra-poor) households, highest adult education level in the household, household attending a public meeting in rural areas, household belonging to either scheduled castes or scheduled tribes, whether the household includes a widowed woman, women’s access to newspaper and radio. The choice of variables selected for the propensity score construction is based on the program characteristics, implementation strategy (Caliendo & Kopeinig, Citation2008) and previous research on the program (Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020). The beneficiary selection criterion is based on the age and the household belonging to BPL or ultra-poor household which has motivated the inclusion of both these covariates in program selection. The program implementation strategies adopted by the government (NSAP website) has suggested using mass media and rural meeting to disseminate information about the program, so these variables have been included in the propensity score model. From the sample, I find that a large proportion of women recipients in IGNOAPS are widows, which substantiate the inclusion of this variable. The variable on household head belonging to scheduled caste or tribe indicates both social and economic marginalisation. In the Indian context, scheduled caste or tribe represents a socially marginalised caste group.

The result of the probit model is reported in the Supplementary section (Supplementary 1). The results from the propensity score model constructed show that a household’s poverty status (BPL or Antyodaya), the presence of elderly members, belonging to a socially disadvantaged caste and including a widow all increase the probability of women receiving IGNOAPS. Higher educational attainments are positively correlated with better economic outcomes, and this lowers the probability of receiving IGNOAPS. Women’s access to radio and newspaper reduces the probability of them receiving IGNOAPS. Access to mass media is positively correlated with household wealth (Garroway, Citation2013), and this has an adverse effect on being a recipient of a poverty-alleviation program.

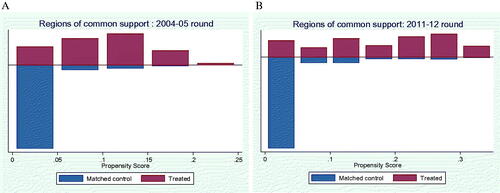

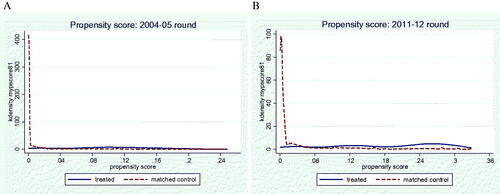

I have used kernel density matching algorithm to match treatment receiving households with non-treatment receiving households. The common support regions for treated and matched control households in both rounds are plotted in . Households that are outside the common support region have been dropped out of the analysis. In , the probability scores for the treatment and matched control units have been plotted to check the overlap assumption. show that the treatment and control groups have a similar distribution, which indicates that the overlap assumption has been attained.

Figure 1. Plot for common support regions for treatment and matched control households.

Source: Author’s calculation based on IHDS data.

Figure 2. Propensity score plot for treatment and matched control households.

Source: Author’s calculation based on IHDS data.

Households where men receive the program, households with two recipients, where one of the two recipients is male are dropped out of the analysis to evaluate the impact of the program when women constitute program recipients. There are very few observations in the dataset of households with three recipients. In all such instances, at least one of the recipients is a male. Hence, those households have been dropped from the estimation as well.

4.2. Fixed effects in the PSM setting

Post matching, I have applied a fixed effects model to estimate the effects of treatment on the outcome variable Equation(1)(1)

(1) .

(1)

(1)

The advantage of using a fixed effects model is that it is useful to eliminate the effects of time-invariant unobservable characteristics like cultural preference which shape consumption behaviour. The methodological framework of combining PSM with fixed effects was also used has been increasingly used in many studies (Imai and Azam (Citation2012), Kim, Kim, Park, and Kawachi (Citation2008) and Unnikrishnan and Imai (Citation2020). EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) has been estimated after using a fixed effects regression method.Footnote7 The fixed effects regression model has been estimated on the matched panel data. In Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1)

is the household food budget share incurred on the following items: cereals, pulses, vegetables; fruits and nuts, meat; eggs and fish, milk and milk products. All the outcome variables are expressed in log. The household (h) level information has been used for both periods (t) 2004–05 and 2011–12. The choice in the outcome variable is guided by Aker et al. (Citation2016). EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) identifies the impact of gaining a pensioner in either round on the household budget share allocation.

is the vector of household-level characteristics that that are controlled for in the specification. This includes number of persons in the household, household wealth (any agricultural land owned or cultivated), education (highest years of education attainment by an adult in the household), place of residence (household-based in an urban area), caste (if the household head belongs to scheduled caste or scheduled tribe), religion (if the household head is a Muslim), and the number of other welfare programmes received by the household. The choice of control variables used here is motivated by the literature of cash transfers, and the country-specific control variables are also selected.

represents time-invariant unobserved characteristics that affect consumption budget share. Time-invariant unobservable characteristics also include cultural factors that shape taste and preferences, and this influences choice for food consumption. The advantage of using a fixed effects regression is that it eliminates the effects of

on the results. The estimations are weighted by the propensity score to address sample selection bias, as women program beneficiaries constitute a sub-sample in the data. Weighting also takes into account the differential incentive of households to participate as the program eligibility criterion changed between the rounds (Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020).Footnote8

4.3. Differential exposure

I have further estimated the correlational effect of differential exposure to the program. Here, I compare the correlation between having a female pensioner in a single round vis-à-vis in both rounds on the outcome variables. From the sample, I find that 1620 households have female pensioner at least in one round, and 286 households had pensioners in both rounds. I have estimated an OLS model on the matched sample weighted with PS. OLS has been employed instead of FE to circumvent the issue on dropping time-invariant observations on pension recipients in both rounds. In Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) ,

the estimated effect of having access to IGNOAPS in a single round and

captures the effect of both rounds. It should be noted that the results estimated from Equationequation (2)

(2)

(2) is merely correlational and less likely to be a causal effect.

(2)

(2)

4.4. Continuous programme recipients and spatial price differences

PSM helps to identify a comparable counterfactual group from the sample. And the application of fixed effects helps identify the effect of gaining a pensioner on the outcome variable. However, it should be noted that the framework (PSM-FE) does not consider the inter-changeability of treatment status, which is the program non-recipient (control group) in the 2004–05 round can constitute as program recipient (treatment group) in the 2011–12 rounds. Therefore, I examine the effect of continuous program recipients, which is households that have received the program in both rounds, on the outcome variables.

Following Deaton (Citation1988), I used cluster fixed effects that interacted with time dummies in regression specifications to account for intertemporal spatial price differences. It is important to account for the prices of food items as it influences food budget shares incurred on different food items. However, IHDS does not detail the prices on all the outcome variables used. In the outcome variables studied here, only the prices of meat, eggs and fish and pulses are available.Footnote9 Deaton (1998) suggest that within the same cluster, the unit price of food is constant. The explanation given by the author is that surveys classify households into various clusters based on their geographical proximity, such that households that are located closer to each other are often classified as a single cluster. The rationale is that it minimises the transportation cost and travel time for enumerators. Although prices are not observed, unobserved cluster fixed effects should capture differences in prices. The interacted cluster fixed effects with time dummies capture the spatial price differences, which vary across time.

4.5. Impact of gaining a pensioner in the 2011–12 round

The program underwent a series of change by the second round, which includes the change in eligibility criterion and the revision in the amount provided in the program. Therefore, I have examined the impact of gaining a pension recipient only in the second round on the disaggregated expenditure shares. I have used a Difference in Differences model in the PSM setting to estimate this effect. The standard Difference in Differences requires a baseline where IGNOAPS has not been implemented. However, the program has been in place from 1995, but the IHDS rounds are recent. Therefore, I have dropped the pension recipients from the sample so that the 2004–05 rounds act as a baseline and evaluated the impact of gaining a new pension recipient in the 2011 rounds on the expenditure shares.

In Equationequation (4)(4)

(4)

captures the effect of the 2011 round,

is the impact of gaining a new female pensioner in the 2011 round. Galiani, Gertler, and Schargrodsky (Citation2005) has shown that in a two-round panel data

is equivalent to the interacted effect of gaining a new female pensioner in 2011 rounds (DID coefficient).Footnote10

(4)

(4)

4.6. Instrumental variable in the PSM-FE setting

The research aims to examine the impact of IGNOAPS on the budget share incurred on the disaggregated items. I have used matching with fixed effects to explore the impact of gaining a female pensioner on the outcomes studied here. The advantage of using a fixed-effects model is that it eliminates the effect of any time-invariant unobservable characteristics like the taste and cultural norms on the budget preferences of the household. Matching helps to remove any systematic difference between the treatment and the control group. Selection bias in treatment assignment can be due to both observable and unobservable characteristics, and PSM takes into account selection bias due only to observable characteristics. However, if any unobservable time-varying characteristics affect treatment assignment and the correlation between the treatment assignment variable (X) and the error term (u) violates the OLS assumption. From the robustness analysis following Oster (Citation2019), I find omitted variable bias arising from unobservable characteristics is not a major concern for most outcomes studied here, besides pulses (detailed in the next section). To circumvent the issue on unobservables on pulses, an instrument has been used. Instrumental variable (IV) strategies are used to address endogeneity.

The instrument that I have used here is the number of female program beneficiaries at the village level, converted into log terms for the sake of interpretation. IGNOAPS is a decentralised program, and the power to identify new recipients is vested with the local governments. There are different ways to gauge the effectiveness of a welfare program. The instrument on the number program beneficiaries at the village level indicates both institutional effectiveness at identifying beneficiaries and low transactional cost involved at obtaining the program.Footnote11 Evidence suggests that pensioners have to wait for a long-time to receive the program, and postal delivery of pension also facilitates corruption by the postal employees (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017). Besides, long-distance commutes to banks to withdraw pension payments also increases the transaction cost (Marulasiddappa et al., Citation2014). Other forms of barriers also include bureaucratic hurdles involved in getting the eligibility proofs required for the program, and all of this increases the transactional cost for obtaining IGNOAPS. A high transactional cost is a common characteristic featured in poverty-alleviation programs implemented in developing countries (Mkandawire, Citation2005). Program with high transaction cost has low intake unless the benefits substantially outweigh the cost of accessing the programme. So, in villages where there is a large program intake, the transaction cost for getting IGNOAPS is low, which in turn increases the participation in the program. Therefore, I expect the instrument to be positively related to the treatment assignment.

The first stage F-statistic has been computed to validate the strength of the instrument (discussed in the next section). However, there is no formal test available to examine the exclusion restriction (second stage). The exclusion restriction is violated if the instrument (number of beneficiaries in the village level) has a direct effect on the household budget share. This can occur for the following reason. IGNOAPS is targeted on poor elderly and villages that have a significant large elderly population and a high level of poverty rate will have more program beneficiaries. This violates the exclusion restriction as the instrument is correlated with poverty, and this has an implication on the household food budget shares. I performed state-level and village level analysis to corroborate this. The results are summarised in the subsequent paragraphs.

Analysis on the number of state-level program recipients (data is taken from the NSAP website) with the census information on the number of elderly present in each state suggests that it is not necessarily true that states with a large number of elderly (Goa, Kerala) also have an equivalent intake of the program.Footnote12

It is also possible that IGNOAPS fund flows are higher in certain villages because of the high level of poverty experienced in those villages, in which case, the instrument used is correlated with the outcome variables studied. This again violates the exclusion restriction. The estimates from the IHDS data show that IGNOAPS intake is larger in villages where the average monthly consumption expenditure is greater than the sample mean consumption expenditure, and this signifies that the exclusion restriction is not violated. Therefore, I do not foresee a direct effect between the instrument and the outcomes. The empirical results are discussed in the next section.

5. Empirical results

The estimated results from Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) to Equation(4)

(4)

(4) is reported in . Panel A is the estimate from the fixed effects model specified in Equationequation 1

(1)

(1) . Panel B and C are the estimated results from Equationequation 2

(2)

(2) and Equation3

(3)

(3) , the DID results (Equationequation 4

(4)

(4) ) is in Panel D.

Table 1. Estimated results on PS weighted matched panel

The results from the fixed effects estimates in Panel A suggest that compared to households with no female program recipients, households with female IGNOAPS recipient increase their food budget share on vegetables, fruits and nuts expenditure by 26%. Similarly, their allocation on meat, eggs and fish are also likely to boost by 17%. The average monthly expenditure of the pension recipient on vegetable, fruits and nuts is INR 889.12 and meat is INR 147.0. With the arrival of the pension, this average expenditure will boost to vegetables, fruit and nuts (INR 1120.29) and meat by INR 171.99. However, IGNOAPS does not have any significant impact on the food budget share expenditure allocation on cereals, pulses, and milk products. The income effect of the program implies that when household income increases, they move towards consumption of better quality diet. Bennett’s law is an extension of the income effect. Bennett’s law suggests that with an increase in income households preference move towards consuming from starchy cereals to more expensive diet like consuming more vegetables, fruits and meat (Meenakshi, Citation1996). This is reflected in the results presented here as with the arrival of the pension; the household income increases their preference move towards more expensive diet. In developing countries, cereals are cheaper compared to vegetables and fruits (Pingali, Citation2015).

The complete set of results with the control variable is provided in Supplementary 2. The control variable on household size, which is captured by the number of persons living in the household increases the household budget share incurred on all the food items. Large households will need to spend more on various food items, and this is reflected here. Household wealth proxied with owning agricultural land increases the budget allocation pulses and vegetables, and the highest level of education of the household adult another measurement of household wealth also increases budget share on all the food items besides cereals. Similarly, households living in urban area augments the spending on all the outcomes variables studied here, except cereals where there is no impact. Caste does not have a significant impact on the outcomes. Household head’s religion does not have any bearing on the disaggregated items, besides the budget share on cereals. I have also controlled for all the other welfare programs received by the household in order to separate the effects of IGNOAPS on the outcomes. Households that receive additional welfare programs increase their spending on all the food items studied here in exception to cereals. Additional specifications after controlling for the number of elderly women and a number of children have also been estimated.Footnote13 The overall effect of the program remains on vegetables, fruits and nuts (25%) and meat (16%) which is consistent with the results reported in Panel A ().

It is possible the estimated effect here is influenced by extreme low PS values. To further check the robustness of the results, I restricted the estimations for those observations whose PS is greater or equal to the average PS value (average = 0.028) in the sample, to avoid the influence of low PS values on the estimated effects. I find the program significantly improves the budget share allocation on vegetables, fruits and nuts (25%).Footnote14

In Panel B, the estimated results from the differential exposure (Equationequation 2(2)

(2) ) to the program have been tabulated. Differential exposure here gauges the effect of receiving a pension for a single round (IGNOAPS beneficiary in a single round) and being a pension recipient in two rounds (IGNOAPS beneficiary in both rounds). The single-round could be either 2004–05 or 2011–12. The results from Panel B are correlational and not causal.Footnote15 The results suggest that at means beneficiaries of both rounds significantly improved the budget share on pulses (10.8%) compared to beneficiaries in a single round (4.8%). Households, where women received IGNOAPS in a single round on average, increased their allocation on vegetables is (9.6%) and significant compared to recipients of two rounds (8.2%) but insignificant. The overall findings from Panel B suggest that a strong correlation between the length of exposure to IGNOAPS and improvement with diet quality.

PSM-FE examines the effect of gaining a pensioner in either round on the outcome variables. However, it should be noted that it does not consider the interchangeability of treatment status (see section 4.4). Therefore, in addition to the results presented in Panel A and B, I have examined the effect of being a continuous program recipient on the outcome variables (Panel C). It should be noted that 286 households have received the program in both rounds. I examine the effect of the continuous program recipients (286 households) on the consumption outcomes. However, I have excluded IGNOAPS recipients who have received the pension in a single round from the sample. I have also controlled spatial price differences using village fixed effects interacted with time dummy (discussed in section 4.4). The results suggest that continuous program recipients augment their budget share on pulses (15%), vegetables, fruits and nuts (20.7%), milk and milk products (49%). As an additional robustness measure, I have evaluated the results only on households receiving IGNOAPS recipients and not any other welfare programmes. For this estimation, I have dropped households that have received any other welfare programme from the sample. This helps to separate the income effect emanating from similar welfare programmes. The estimated results suggest that IGNOAPS recipients continues to augment budget share on pulses (13.9%), vegetables fruits and nuts (20.4%), and milk and milk products (55.4%).

IGNOAPS was introduced in 1995, and as detailed in section 2, the program did undergo changes over time. The changes include use of BPL card to identify beneficiaries and the reduction in the age eligibility criterion. Therefore, I have estimated the impact of gaining a pensioner in the 2011 rounds on the outcome variables. I have excluded pensioners from the 2004 to 2005 rounds so that the round acts as a baseline. The results from Panel D suggest that gaining a new pensioner in the 2011 round has not significantly impacted the welfare outcomes. Apart from the food budget share incurred on vegetables, they have reduced their budget share incurred on meat, eggs & fish and milk and milk products. This implies that the expansion of the program did not augment welfare effects. This is in line with previous research findings on IGNOAPS. The high-level exclusion targeting error in the program leads to a reduction in welfare effects (Asri, Citation2019; Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020).Footnote16

In addition, I have also estimated the impact of the amount received in IGNOAPS (transformed into Inverse Hyperbolic Since transformation) on the various outcomes. EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) has been re-estimated with replacing the key independent variable of being IGNOAPS beneficiary with the amount received from IGNOAPS (transformed into Inverse Hyperbolic Since transformation). Inverse Hyperbolic Since transformation (IHS) behaves similarly to a log-transformation, the difference being IHS it is defined at zero (Bahar & Rapoport, Citation2018; Jayachandran et al., Citation2017; Bellemare & Wichman, Citation2020). From the summary statistics reported in Appendix 2, we find that for the non-pension recipients, the IHS transformation helps to define the pension amount at zero. The findings reported in Supplementary 3 suggest the marginal effect of a 10% increase in IGNOAPS amount will increase vegetable expenditure by (0.3%), and meat expenditure by (0.2%). In the matched panel data, the average real pension amount (annual) received by the beneficiary in 2011–12 is INR 2222.1. The magnitude of the impact is smaller compared to the impact of being a pension recipient because the incremental increase in the pension amount is smaller.

5.1. Instrumental variable estimates and sensitivity test

5.1.1. Robustness test on unobservables

To check omitted variable bias arising from unobservable characteristics I have followed Oster (Citation2019) to calculate the proportion of unobservables required to vanish the estimated effect of female IGNOAPS beneficiary. Oster (Citation2019) has suggested using R-square movements before and after including observable controls to understand the significance of omitted variable bias arising from unobservable variables. Altonji, Elder and Taber (Citation2005), Oster (Citation2019) focussed on calculating the ratio of unobservables to the ratio of observables (denoted as δ), needed to make the estimated treatment effect (female IGNOAPS beneficiary) to be equal to zero (Berniell & Bietenbeck, Citation2020). Results reported in Supplementary 4 indicates the effect of IGNOAPS with and without the controls. The inclusion of the controls for all the outcome variables substantially increases the R-square values. The δvalues (reported in Cereals) suggest that the unobservables have to be three times large to make the effect of IGNOAPS equivalent to zero. The negative sign of δ suggest that the unobservables have to move in the opposing direction of the observables to make the effect of the treatment irrelevant (Berniell & & Bietenbeck, Citation2020). From the results reported in Supplementary 4, I find the unobservables has to be substantially large enough to make treatment coefficient to zero for most outcome variables, suggesting that omitted variable bias in the form of unobservable characteristics is not a major concern for most cases here. Besides the outcome on pulses for all the other outcomes variables in the study, the value of δ>1 suggesting the treatment effects are robust to unobservables (Berniell & Bietenbeck, Citation2020). Given that the treatment effects are not robust for the outcome on pulses, an instrument has been used to address this. For consistency, I have estimated the IV results on all the outcomes.

5.1.2. IV results

The estimates from the IV regression suggest that households with female IGNOAPS beneficiaries (instrumented with the number of beneficiaries at the village level in log terms) reduce their budget share on cereals (2.67%) and increase their share of expenditure on pulses (7.67%), vegetables (21.55%), meat (12.45%) and milk (9.90%). Results are given in Supplementary 5. Overall, the results from the IV estimates reinstate the findings from the PSM-FE regression estimates (, Panel A). Households with IGNOAPS recipients (female) move towards a better-quality diet compared to program non-recipients (female). The estimates from the IV regression need to be interpreted cautiously. IV standard errors are substantial compared to the OLS estimates, but they are preferred over OLS estimates as the latter is inconsistent in the presence of endogeneity.Footnote17

5.1.3. Alternate matching method

Although PSM helps build a valid comparison group to evaluate the impact of the old-age pension programme, there has been criticism on PSM as a valid pseudo-experimental method (King & Nielsen, Citation2019). Therefore, alternatively I have estimated results using direct covariate matching (DCM). Following Kirchweger, Kantelhardt, and Leisch (Citation2015), DCM is also considered uncomplicated and does not require a parametric specification and uses exact matching procedure (Kirchweger et al., Citation2015; Sekhon, Citation2009).

I have used program eligibility criteria: a household with a BPL/antyodya card and an elderly woman in the household for exacting matching. Further, I have specified control variables in the specification to account for other socio-economic characteristics that can affect the household budget share incurred on different items. The estimated result (average treatment effect on the treated) suggests that compared to program non-recipients, households with female IGNOAPS recipients significantly increases household budget share incurred on pulses (8.1%); vegetables, fruits and nuts (17.8%); meat and eggs (13%), milk and milk products (15%).

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have estimated the causal effect of an unconditional cash transfer program (IGNOAPS) received by women on various outcome variables. The outcome variables studied here represents budget share expenditure incurred disaggregated food items. IGNOAPS is not randomly assigned, and there could be a systematic difference between households where a woman receives the program (treatment) and the non-treatment receiving households. Therefore, PSM has been used to remove any systematic observable differences between the two groups. A fixed effects regression model has been used to eliminate the effect of time-invariant unobservable characteristics, which includes cultural factors that shape tastes and preferences. PSM is useful to remove any systematic observable differences between the treatment and the control group.

The PSM- fixed effects results suggest that households that have female IGNOAPS beneficiary increase their budget share on vegetables, fruits and nuts (26%) and meat, fish and eggs (17%). This confirms the presence of Bennett’s law whereby household shift towards better-valued food with the increase in income, and the results has been confirmed from the IV analysis. The findings from the paper also confirm that there is a strong correlation between the length of exposure to the program and the consumption outcomes. The results also suggest that after accounting for spatial price differences, continuous program recipients tend to boost their budget allocation on pulses, vegetables, fruits and nuts, milk and milk products. However, the DID estimates highlight that the impact of the program weakens over time with the changes made in the program eligibility criterion. This finding is consistent with previous research on the program.

From a policy perspective, first, women’s access to IGNOAPS does improve household budget share allocation high valued food items. This suggests that social assistance programs have the potential to reduce old-age consumption poverty and vulnerability among elderly women. Previous research on old age pension program highlights that even though the pension payment is modest, it does help pensioners to avoid food deprivation (Drèze & Khera, Citation2017). Second, women who are exposed to the program for a longer period has attained better outcomes suggesting the need to continue with the welfare programme. However, the changes made in the program eligibility criterion have reduced welfare effects. Therefore, the program should focus on reducing leakages (Asri,Citation2019; Unnikrishnan & Imai, Citation2020).

Due to data limitations, I have only examined the impact of the program on household food consumption behaviour. Future research can explore individual food consumption behaviour within the household. There are inter-state variations in the program eligibility criteria used which is not examined here. IHDS is representative at the national level and not at the state level, so it is not possible to incorporate the state-level variations with eligibility criterion in the analysis to obtain state-level estimates. The results here provide evidence on the impact of the pension at the national level. However, there could be differences in the effectiveness of the pension across-states due to variations with implementing capacity. Also, due to non-availability of price information for all the food items the system demand equations couldn’t be applied.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (616.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge valuable feedback from David Fielding, Kunal Sen, Katsushi Imai, an anonymous refereee, Supriya Ghritikapati, Abhishek Chakraborty, and Armando Barrientos . I am also thankful to the participants in internal seminar at the Global Development Institute, Spanish Economic Conference, 13th Association of Italian Studies on Population for their valuable feedback. However, the usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Missing women is a concept introduced by Amartya Sen. It highlights the relatively smaller proportion of women surviving compared to men and this widely seen in a developing countries like India and China.

2 https://www.agewellfoundation.org/pdf/reports/Older%20Women%20In%20India%20-%20A%20Note%20by%20Agewell%20Foundation%20-%20India.pdf; https://www.livemint.com/Politics/z6BacVOwf5SvmpD9P1BcaK/20-of-population-to-be-elderly-by-2050-HelpAge-India-repor.html

4 This programme was previously known as Bono Solidario.

5 siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTHDOFFICE/…/11_Matching_Technical.pptx

6 siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTHDOFFICE/…/11_Matching_Technical.pptx

7 The choice between fixed effects and random effects model is determined by the results from the Hausman test.

8 The treatment group gets the weight of one, and the weights for the control group it is PS/1-PS where PS stands for the propensity score as described by the authors. This has been adopted from Hirano and Imbens, Citation2001.

9 The estimated impact of IGNOAPS on the fixed effects model on the matched panel (Panel A: Table 3) for the outcome on food budget share incurred on meat, after incorporating the own prices and the prices of pulses, is positive but insignificant. The impact of IGNOAPS on budget share on pulses after accounting for its own prices and price of meat is negative and insignificant.

10 In order to examine the parallel trend assumption, I require at least three rounds of data. However, I have only two rounds of data which makes examination of the parallel trend assumption not possible. It should be noted that Ryan et al. (Citation2019) used Monte Carlo simulation to evaluate the effect of health policy intervention. Their findings suggest that compared to a standard DiD; single-group interrupted time-series analysis, multi-group interrupted time-series analysis-DiD with propensity score matching performs better (lower mean-squared error) in the event of violation of parallel trend assumption. The author highlights that since matching is performed based on observable characteristics and attaining the common support assumption ensures that the treatment and the control group have similar pre-intervention levels. Further, as pointed out by Unnikrishnan and Imai (552020) the treatment and control group are spread across villages in all the states (IHDS dataset) which would imply that the treatment and the control groups on average have similar trends.

11 The instrument is the women beneficiaries, as they constitute the focal point of this research.

12 The beneficiaries information was taken from the NSAP website: http://nsap.nic.in/nationalleveldashboardNew.do?methodName=getCenterData&schemeCategory=C&main=main

13 Results will be shared on request

14 From the descriptive data (Appendix 2), I observe 38.9% of the households in the treatment group has reported having belonged to scheduled caste/tribe in 2004, which is about 34.4% in 2011-12. Therefore, I have estimated a regression excluding people whose caste (scheduled caste and scheduled tribe) denomination has changed between the rounds. Exclusion of households whose caste denomination changes between rounds makes caste variable time-invariant. The overall FE-result remains consistent as the program significantly increases the budget share incurred on vegetables, fruits and nuts (24%).

15 In Panel A, I estimated the impact of gaining a pensioner in either round in the matched panel data and have employed household fixed effects. While in Panel B, it is the estimated results from OLS regression and no household fixed effects has been used. The fixed effects eliminate time-invariant characteristics, and it is not possible to incorporate households who received IGNOAPS in two-rounds and household fixed effects in the same model. Therefore, any direct comparison between Panel A and Panel B estimates could be misleading as the empirical strategies are different. It should also be noted that non-inclusion of the household fixed effects could also bias the estimates reported in Panel B.

16 An alternate model of equation (3) with replacing the primary independent variable as has been estimated;

here captures a new pensioner gain in the 2004-05 rounds. Here, I have dropped pensioners in 2011 rounds, so that it can act as a baseline. The alternate model probes the impact of having a pensioner in the first round on the outcome variables. This is useful to disintegrate the impact of the program in 2004 rounds. The results suggest that female pension recipient in the 2004 rounds reduces cereal and pulse budget share. However, they improve their allocation of vegetables, meat and milk & milk products which suggest that the impact of the program weakened in the second round. Besides pulses, the impact on other outcome variables studied here is not significant. The treatment group is not receiving the program in period-2 here. The treatment households could experience negative income shocks, which might affect the consumption of certain food items.

17 The strength of the instrument is determined by the computed first-stage F statistic. In the case of a single endogenous regressor, the computed first stage F-statistic should greater than 10 for the instrument to be strong (Staiger & Stock, Citation1997). The computed F-statistic (Table 4) is greater than ten; therefore, we reject the hypothesis on instruments being weak.

References

- Adato, M., De la Briere, B., Mindek, D., & Quisumbing, A. R. (2000). The impact of progresa on women's status and intrahousehold relations; Final report (No. 600-2016-40133).

- Agarwal, A., Lubet, A., Mitgang, E., Mohanty, S., & Bloom, D. E. (2020). Population aging in India: Facts, issues, and options. In Population change and impacts in Asia and the Pacific (pp. 289–311). Singapore: Springer.

- Aker, J. C., Boumnijel, R., McClelland, A., & Tierney, N. (2016). Payment mechanisms and antipoverty programs: Evidence from a mobile money cash transfer experiment in Niger. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 65(1), 1–37.

- Altonji, J. G., Elder, T. E., & Taber, C. R. (2005). Selection on observed and unobserved variables: Assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 151–184.

- Anderson, S., & Ray, D. (2010). Missing women: Age and disease. The Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1262–1300.

- Anderson, S., & Ray, D. (2012). The age distribution of missing women in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 2012, 87–95.

- Anderson, S., & Ray, D. (2019). Missing unmarried women. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(5), 1585–1616.

- Armand, A., Attanasio, O., Carneiro, P., & Lechene, V. (2020). The effect of gender-targeted conditional cash transfers on household expenditures: Evidence from a randomized experiment. The Economic Journal, 130(631), 1875–1897.

- Asri, V. (2019). Targeting of social transfers: Are India’s poor older people left behind? World Development, 115, 46–63.

- Attanasio, O., & Lechene, V. (2002). Tests of income pooling in household decisions. Review of economic dynamics, 5(4), 720–748.

- Bahar, D., & Rapoport, H. (2018). Migration, knowledge diffusion and the comparative advantage of nations. The Economic Journal, 128(612), F273–F305.

- Barrientos, A., Gorman, M., & Heslop, A. (2003). Old age poverty in developing countries: Contributions and dependence in later life. World development, 31(3), 555–570.

- Bhattacharya, S., Jos, M. M., MEHTA, S. K., & Murgai, R. (2015). From policy to practice: How should social pensions be scaled up? Economic and Political Weekly, 2015, 60–67.

- Bellemare, M. F., & Wichman, C. J. (2020). Elasticities and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 50–61.

- Bergolo, M., & Galván, E. (2018). Intra-household behavioral responses to cash transfer programs. Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. World Development, 103, 100–118.

- Berniell, I., & Bietenbeck, J. (2020). The effect of working hours on health. Economics & Human Biology, 39, 100901.

- Calvi, R. (2020). Why are older women missing in India? The age profile of bargaining power and poverty. Journal of Political Economy, 128(7), 2453–2501.

- Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of economic surveys, 22(1), 31–72.

- Chopra, S., & Pudussery, J. (2014). Social security pensions in India: An assessment. Economic and Political Weekly, 2014, 68–74

- Deaton, A. (1988). Quality, quantity, and spatial variation of price. The American Economic Review, 1988, 418–430.

- De Brauw, A., Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., & Roy, S. (2014). The impact of Bolsa Família on women’s decision-making power. World Development, 59, 487–504.

- de Carvalho Filho, I. E. (2012). Household income as a determinant of child labor and school enrollment in Brazil: Evidence from a social security reform. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(2), 399–435.

- Desai, S., & Vanneman, R. (2010). National Council of applied economic research, New Delhi. In India Human Development Survey (IHDS), 2005 (pp. 06–29). Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor].

- Desai, S., & Vanneman, R. (2015). India human development survey-ii (ihds-ii), 2011–12. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

- Drèze, J., & Khera, R. (2017). Recent social security initiatives in India. World Development, 98, 555–572.

- Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 1–25.

- Dutta, P., Howes, S., & Murgai, R. (2010). Small but effective: India’s targeted unconditional cash transfers.

- Fund, U. N. P. (2017). Caring for our elders: Early responses. India Ageing Report–2017.

- Garroway, C. (2013). How much do small old age pensions and widow’s pensions help the poor in India. Development Papers, 1306.

- Galiani, S., Gertler, P., &Schargrodsky, E. (2005). Water for life: The impact of the privatization of water services on child mortality. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 83–120.

- Giridhar, G., Subaiya, L., & Verma, S. (2015). Older women in India: Economic, social and health concerns. Increased Awarenes, Access and Quality of Elderly Services. BKPAI (Building Knowledge Base on Ageing in India), Thematic Paper, 2.

- Gopal, M. (2006). Gender, ageing and social security. Economic and Political Weekly, 2006, 4477–4486.

- Gupta, A. (2013). Old-age pension scheme in Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Economic and Political Weekly, 2013, 54–59.

- Holmes, R., & Jones, N. (2010). Cash transfers and gendered risks and vulnerabilities: Lessons from Latin America.

- Hirano, K., & Imbens, G. W. (2001). Estimation of causal effects using propensity score weighting: An application to data on right heart catheterization. Health Services and Outcomes research methodology, 2(3), 259–278.

- Imai, K. S., & Azam, M. S. (2012). Does microfinance reduce poverty in Bangladesh? New evidence from household panel data. Journal of Development studies, 48(5), 633–653.

- Jayachandran, S., De Laat, J., Lambin, E. F., Stanton, C. Y., Audy, R., & Thomas, N. E. (2017). Cash for carbon: A randomized trial of payments for ecosystem services to reduce deforestation. Science, 357(6348), 267–273.

- Kalavar, J. M., & Jamuna, D. (2011). Aging of Indian women in India: The experience of older women in formal care homes. Journal of women & aging, 23(3), 203–215.

- Kaushal, N. (2014). How public pension affects elderly labor supply and well-being: Evidence from India. World Development, 56, 214–225.

- Khandker, S. R., Koolwal, G. B., & Samad, H. A. (2009). Handbook on impact evaluation: Quantitative methods and practices. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

- Kim, M. H., Kim, C. Y., Park, J. K., & Kawachi, I. (2008). Is precarious employment damaging to self-rated health? Results of propensity score matching methods, using longitudinal data in South Korea. Social science & medicine, 67(12), 1982–1994.

- King, G., & Nielsen, R. (2019). Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis, 27(4), 435–454.

- Kirchweger, S., Kantelhardt, J., & Leisch, F. (2015). Impacts of the government-supported investments on the economic farm performance in Austria. Agricultural Economics, 61(8), 343–355.

- Meenakshi, J. V. (1996). Food consumption trends in India: Towards a better quality of diet. Journal of the Indian School of Political Economy, 8, 3533–3550.

- Marulasiddappa, M., Raonka, P., & Sabhikhi, I. (2014). Social security pensions for widows and the elderly. Indian Journal of Human Development, 8(1), 49–63.

- Mkandawire, T. (2005). Targeting and universalism in poverty reduction. Geneva: WHO.

- National Social Assistance Programme. n.d. Government of India, accessed from, http://nsap.nic.in/http://nsap.nic.in/Guidelines/modifications%202007.pdfhttp://nsap.nic.in/Guidelines/aps.pdf

- Oster, E. (2019). Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 37(2), 187–204.

- Pingali, P. (2015). Agricultural policy and nutrition outcomes–Getting beyond the preoccupation with staple grains. Food security, 7(3), 583–591.

- Ponczek, V. (2011). Income and bargaining effects on education and health in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics, 94(2), 242–253.

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

- Roy, K., & Chaudhuri, A. (2008). Influence of socioeconomic status, wealth and financial empowerment on gender differences in health and healthcare utilization in later life: Evidence from India. Social science & medicine, 66(9), 1951–1962.

- Rubalcava, L., Teruel, G., & Thomas, D. (2009). Investments, time preferences, and public transfers paid to women. Economic Development and cultural change, 57(3), 507–538.

- Ryan, A. M., Kontopantelis, E., Linden, A., & Burgess Jr, J. F. (2019). Now trending: Coping with non-parallel trends in difference-in-differences analysis. Statistical methods in medical research, 28(12), 3697–3711.

- Schady, N., & Rosero, J. (2008). Are cash transfers made to women spent like other sources of income? Economics Letters, 101(3), 246–248.

- Sekhon, J. S. (2009). Opiates for the matches: Matching methods for causal inference. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 487–508.

- Staiger, D., & Stock J. H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65, 557–586

- Thomas, D. (1993). The distribution of income and expenditure within the household. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 1993, 109–135.

- Unnikrishnan, V., & Imai, K. S. (2020). Does the old-age pension scheme improve household welfare? Evidence from India. World Development, 134, 105017.