?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this paper, we study the effect on intimate partner violence of a large public work programme in India that explicitly encourages female participation (MGNREGA). Based on detailed administrative data, we show that the work programme leads to more violence against women. We show that the effect is caused by female employment, and argue that it can be explained by a ‘male backlash’ mechanism, where husbands exercise violence to regain power within marriage.

1. Introduction

Violence against women and girls is a worldwide problem. In itself, violence is a stark human rights violation, but it also entails huge negative externalities in the form of preventing females from fully participating in society. Fearon and Hoeffler (Citation2014) calculate that the cost of intimate partner violence is as high as 5 per cent of GDP globally. The regional costs in much of Sub-Saharan Africa and South-Asia are likely to be much higher, given the higher incidence of domestic violence in these areas.

In this paper, we study the effects on intimate partner violence of a large public work programme in India, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The work programme guarantees all rural households 100 days of paid work each year, and it explicitly encourages female participation. Nearly half of total workdays are taken up by females (Dasgupta & Sudarshan, Citation2011; Ravi & Engler, Citation2015), in sharp contrast to the otherwise low female labour market participation in India (Klasen & Pieters, Citation2015; Mehrotra & Sinha, Citation2017).

A priori, it is unclear what effect such a work programme would have on domestic violence. On the one hand, MGNREGA provides a safety net of jobs, which could reduce violence caused by economic stress. On the other hand, it raises female employment in a way that could threaten established patriarchal norms, leading to more violence. The empirical literature on MGNREGA and intimate partner violence is too small to be conclusive: Amaral et al. (Citation2015) find that the programme leads to more violence against women, while Sarma (Citation2022) documents that it dampens the effect of adverse rainfall shocks on violence.Footnote1 Both papers explore the roll-out of MGNREGA and use aggregated data on police reported crimes. Our empirical analysis differs in two important ways. First, we make use of employment data at a fine geographical level and for a time period when the work programme was fully implemented all over India. Second, we use state-of-the-art survey data on domestic violence with a large sample, as opposed to data on reported crimes.Footnote2 This is an important advantage, as reported crimes are likely to be severely underreported. As an example, Palermo et al. (Citation2014) use more than 20 DHS surveys and show that only 7 per cent of females that reported abuse in the surveys had reported it to a formal source.

Our data on domestic violence are taken from the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) from 2015 to 2016. These data include GPS coordinates of survey clusters, which enable us to merge in administrative data on MGNREGA at the level of blocks – the second lowest administrative unit in India.Footnote3 The NFHS asks every woman who reports an experience with violence when the first violent episode happened. We use this information to construct a time-series of violence onsets and use this as our main outcome variable (see Cools et al., Citation2020). We are thus studying whether MGNREGA affects the likelihood of husbands crossing the line and becoming violent towards their wives.

We identify this effect using time variation in the number of workers within blocks during the time period 2012 to 2015. The main threat to this approach is time-varying shocks at the block level, correlated with MGNREGA prevalence. One example could be negative income shocks that increase the demand for public work, and at the same time, cause more violence due to economic stress. Our key argument is that such shocks do not automatically translate into more jobs. Extensive research show that implementation of the work programme is hindered by a number of hold-ups, and that the availability of jobs crucially depends on the will of local politicians and bureaucrats (Dutta et al., Citation2014; Khosla, Citation2011; Maiorano, Citation2014). We therefore find it plausible that local year-to-year variation in MGNREGA is quasi-exogenous to factors determining the prevalence of intimate partner violence.

We use data on droughts and night-time light to test whether our data are consistent with this assertion. We first document that the number of job card applications, which can be seen as a proxy for demand for work, increases in drought years. This is as expected, since droughts have an adverse effect on agriculture production and since demand for the relatively low-paid MGNREGA jobs is likely to increase in economic downturns. We then test whether we find a similar relationship with the actual number of jobs provided. We do not. That is reassuring for our identification (but not for the functionality of the work programme), as it suggests that local employment is driven primarily by availability of jobs rather than demand. We conduct a similar exercise using rural night-time light and document a strong and negative correlation between the amount of light (which presumingly is negatively related to economic activity) and the number of job card applications, but no relationship with the actual number of jobs provided.

Our main result is that MGNREGA leads to more intimate partner violence against women. In our preferred specification, we find that a 10 per cent increase in the number of jobs raises the probability of violence by about 1.3 per cent of the baseline. This result is robust to the inclusion of various time trends and time-varying controls, such as droughts and the amount of night-time light, and it survives a placebo exercise based on future MGNREGA employment.

The workfare programme provides the first real work opportunity for many women in rural India (Khera & Nayak, Citation2009), and we argue that the effect on violence is due to just that – and not other programme induced effects. We provide two tests of this. First, we make use of employment data by gender and show that the effect on violence is driven by the number of female workdays. Second, we investigate heterogeneity of our estimates and show that the effect on violence is stronger in areas with a low level of female labour force participation outside the work programme. These are the areas where the programme has the largest impact on whether or not women are working, and thus, the result is consistent with female employment being the mechanism.

Our paper is related to the rapidly growing literature on intimate partner violence and female labour market participation.Footnote4 Theories point in both directions. In household bargaining models, improved labour market conditions for females relative to men typically raises their bargaining power by improving the outside option of marriage. This could reduce violence as the threat of divorce becomes more credible (Farmer & Tiefenthaler, Citation1997). However, in patriarchal societies like much of rural India, the threat of divorce is practically non-existent (Bhalotra et al., Citation2018; Bulte & Lensink, Citation2019; Doyle & Aizer, Citation2018). Increased employment could in such circumstances lead to more, not less, violence. Consistent with the findings in our paper, Bhalotra et al. (Citation2018) document a positive relationship between intimate partner violence and favourable labour market conditions for females, using a sample of 31 low- and middle-income countries. Guarnieri and Rainer (Citation2018) similarly find a positive relationship between female employment and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa.

One hypothesis for why we see this pattern is that paid work empowers females and that husbands exercise violence to regain power within the marriage and to grab the extra resources (Eswaran & Malhotra, Citation2011; Heath, Citation2014; Krug et al., Citation2002). Female employment could also lead to psychological stress by threatening male identity and causing status inconsistencies (Akerlof & Kranton, Citation2000; Bertrand et al., Citation2015). This is argued to be especially likely if the man’s breadwinner status is challenged (Angelucci, Citation2008; Atkinson et al., Citation2005; Hornung et al., Citation1981; Jewkes, Citation2002; Macmillan & Gartner, Citation1999).

Our results are consistent with such a ‘male backlash’ mechanism, as we find that the effect on violence is strongest in areas where few women are working, and as these are the areas that are likely to have the strongest norms against female employment (see also Vyas & Watts, Citation2009). Our results are also consistent with the findings of Heise and Kotsadam (Citation2015), who find a stronger relationship between violence and female employment in countries with less gender equality, and Tur-Prats (Citation2017), who uses Spanish data to show that relatively better labour market conditions for females lead to more intimate partner violence, but only in areas with deep-rooted norms against female employment.

Overall, our paper confirms the earlier finding of Amaral et al. (Citation2015) that MGNREGA leads to more intimate partner violence. The fact that our paper is based on a more recent time period; a completely different empirical strategy; and a large state-of-the-art household survey on domestic violence as opposed to data on reported crimes, significantly strengthens the credibility of this finding.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we describe the relevant features of MGNREGA. In Section 3, we present our data and key variables, and in Section 4, we discuss our empirical approach. We present our findings in Section 5 and provide some concluding remarks in Section 6.

2. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) of 2005 is a right-to-work act that legally guarantees all rural households in India 100 days of paid work, each year. The programme was rolled out from 2006, and by 2008, it covered all parts of rural India. Typical work consists of manual tasks without any particular skill requirements, such as water conservation, land development, and rural sanitation. To get employment through MGNREGA, households apply to the Gram Panchayats (the village council, India’s lowest administrative unit), who verify the applications and hand out job cards to all eligible households.

The work programme has a strong gender dimension. Women are explicitly encouraged to partake, and nearly half of the allocated workdays are taken up by women (Dasgupta & Sudarshan, Citation2011; Ravi & Engler, Citation2015). This is a big achievement, given the otherwise low female labour force participation in India. The programme has several features that are likely to stimulate female participation. First, wages are equal for men and women, which is typically not the case elsewhere. MGNREGA wages are therefore higher than for other work opportunities for women in rural areas. Second, work is usually provided within the village. This is likely to be particularly attractive for women, who continue to be the main caretaker of children and older family members. Travelling long distances to work is difficult for these women.Footnote5 Third, the employment act requires child care facilities at the worksite when small children are present, and work hours are clearly regulated, in contrast to in the private market.

Khera and Nayak (Citation2009) argue that these factors – and that the programme is likely to sidestep local caste and community structures – help make the public jobs socially acceptable for women. In many cases, it therefore provides the first real work opportunity for women. Consistent with this, Kjelsrud and Kotsadam (Citation2021) find that more than 80 per cent of female MGNREGA workers do not have any other type of paid work.

The implementation of the programme builds on a principle of self-selection: every rural household that would like to work is legally entitled to do so. In practice, however, there is a considerable unmet demand for employment (Dutta et al., Citation2014; Maiorano, Citation2014; Ministry of Rural Development & Government of India, Citation2012). The supply of jobs varies greatly, even within small geographical areas, making availability of jobs an important determinant for who is employed (Gulzar & Pasquale, Citation2017). An estimated 19 per cent of all households failed to get work in MGNREGA in 2009-2010, and many employees work less than desired, and less than the guaranteed 100 days (Imbert & Papp, Citation2015).

Some of the reason for this is that implementation depends on a rather complex structure of politicians and bureaucrats, spread over several administrative levels. MGNREGA is centrally funded, but administered at the village and block level. The Gram Panchayats monitor on-going projects and suggest plans for new ones. The block-level administrations have to approve these plans, and more generally, make sure that availability of jobs matches demand within Gram Panchayats in their blocks. On paper, politicians should play little or no role in the implementation. In reality, state-level politicians (MLAs) have both incentives and opportunity to influence the programme implementation (Gulzar & Pasquale, Citation2017). Previous studies show that MLAs put pressure on local field officers to target certain blocks (Maiorano, Citation2014), and that they are able to manipulate the selection of works (Aiyar & Samji, Citation2009). There are also some evidence suggesting that Members of Parliament (MPs) are engaged in the local programme implementation (Gupta & Mukhopadhyay, Citation2016; Kjelsrud et al., Citation2020). In the end, the actual availability of jobs therefore depend on a combination of political will and administrative capacity.

3. Data and key variables

In this section, we describe our data sources and how we construct our key variables.

3.1. Intimate partner violence

Our main data source is the National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) from 2015 to 2016. The survey was conducted on a sample of about 700,000 female respondents, all of them 15–49 years of age. A little more than 9 per cent of these respondents were selected to the domestic violence module, which includes questions on the experiences of physical and sexual violence. Domestic violence is clearly a sensitive interview topic with a risk of underreporting. The NFHS interviewers are therefore trained to handle sensitive information and the guidelines for the module stress the absolute need for privacy and discretion. The data are collected using a modified version of the so-called Conflict Tactics Scale, which is found to be an advantageous method of recording domestic violence in surveys (Kishor, Citation2005).

The Conflict Tactics Scale is based on asking about different scenarios of violence, rather than a single yes/no question. Females are then considered to have experienced violence if they affirm to either one of the scenarios. The NFHS uses scenarios related to the following violent actions: (i) pushing, (ii) twisting of an arm or pulling hair, (iii) slapping, (iv) punch with a fist or something that could hurt, (v) kicking or dragging, (vi) choking or burning, (vii) attacking with a knife, gun or other weapon, (viii) physically forced sexual intercourse, (ix) physically forced other sexual acts, and (x) forced sexual acts through other threats. About 31 per cent of the female respondents state an experience with violence, using the above definition.

For women having experienced violence, the NFHS also asks when the first violent episode happened, in years after marriage. Since the survey includes information on date of marriage, we are able to construct a panel of women’s first violent episode. We merge this panel with several other data sources, as described below.

3.2. Creating a block-level dataset

The NFHS includes GPS coordinates of survey clusters that roughly corresponds to Gram Panchayats. The geocodes enable us to merge in other data using the Census of India as the link between the different sources.

The rural clusters in the NFHS are randomly displaced with up to 5 km.Footnote6 Because of this we aggregate all other data to Indian blocks. Note that we still risk that some of the NFHS clusters end up in wrong blocks due to the displacement. However, as the displacement is at random it should not introduce any particular bias in our estimation.

We first combine the NFHS coordinates with a map over all 2001 Census villages from the ML InfoMap. From this we obtain 2001 village identifiers. We then link village codes to Census villages as of 2011 using the official correspondence table. This gives us block identifiers as of 2011, which we use to merge in the other data.

We collect data on MGNREGA from the MGNREGA Public Data Portal. The data source has information on employment at the block level for the financial year 2011-2012 and onwards. We mainly make use of data for the years 2011-2012 to 2014-2015, and extract the following information: the number of MGNREGA workers, the number of days worked by gender and the number of job card applications.Footnote7 The data include names of blocks but does not have Census identifiers. We therefore match the MGNREGA data with the Census based on block names and a combination of fuzzy matching and manual checking. In total, we are able to match more than 92 per cent of the MGNREGA blocks to the Census (see Asher & Novosad, Citation2017; Gulzar & Pasquale, Citation2017; Kjelsrud et al., Citation2020, for similar type of matching in the Indian context).

We extract data on local rainfall from the SPEI global database (Beguería et al., Citation2010; Vicente-Serrano, Beguería, López-Moreno, et al., Citation2010). These data provide information on drought conditions with a 0.5° spatial resolution and a monthly time resolution. We merge this with the Indian Census based on the digital maps and aggregate to blocks. We define droughts based on the Standardised Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), which is a state-of-the art meteorological drought index that accounts for both precipitation and evapotranspiration when determining droughts (Vicente-Serrano, Beguería and López-Moreno, Citation2010). We use this to construct two indicator variables, denoting whether blocks experience an extreme or a severe drought during a particular year.Footnote8

We get data on night-time light from the Shrug open data platform (Asher et al., Citation2019). The data in Shrug are aggregated to Indian villages based on the DMSP-OLS annual measures of light luminosity during the night, measured at 1/120°. We calculate the average light luminosity in rural areas at the level of blocks by dividing the sum of night-light in each block by the number of cells. The DMSP-OLS light data span the years 1994 to 2013, which are two years short of our study period. To deal with this, we linearly extrapolate the data to the years 2014 and 2015. Our light variable is therefore a trend-measure of the amount of light at the block level.

We make use of two different data sources to derive estimates of female labour force participation outside the work programme. The first source is the Economic Census of 2013, which provides a full enumerations of all non-farm establishments, including informal firms, service sector firms, and publicly owned firms. It also includes information on the number of male and female workers. We use this to construct a measure of female labour force participation as the total number of female workers by blocks, divided by the total number of females (taken from the Indian Census). In the appendix, we make use of the Economic Census of 1998 to measure past prevalence of female labour force participation.Footnote9

The second source is the Employment-Unemployment survey from 2011 to 2012, collected by the National Sample Survey (NSS). The NSS is a national representative household survey, usually collected every fifth year. The survey enables us to create a broader measure of labour force participation that also includes casual workers, self-employed, and unemployed. We focus on married women in the age group 20 to 60 years, and rely on self-reported ‘principal activity’, which refers to the status during the last year (Klasen & Pieters, Citation2015).Footnote10 The disadvantage with the NSS is that it does not provide GPS coordinates. The finest geographical identifier is districts. We therefore harmonise the district codes with the Census and merge the data with our other sources based on this.

3.3. Sample restrictions and summary statistics

We focus on women being no more than in their fifth year of marriage at the time of survey. There are two reasons for this sample restriction.

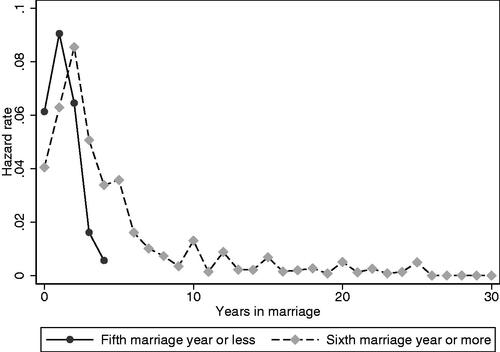

First, the MGNREGA employment data start in 2012 and the nature of the ‘first episode’ variable implies that females enter the sample at the time of marriage and exit if they experience violence. This means that all females experiencing violence before 2012 are excluded from the sample. In , we show a hazard plot, calculated as the number of females experiencing violence for the first time in a given marriage year, divided by the total number of females in the same marriage year without any earlier experience with violence. The figure shows that violence usually starts the first few years after marriage, and that it almost never starts more than 10 years after marriage. The females that married many years ago, and that potentially could have entered our estimation sample, would thus represent a very selected group of females from non-violent relationships.

Figure 1. Risk of first violence, by years in marriage.

Note: The hazard rates show the number of women who experience violence for the first time in a given marriage year, divided by the number of women at risk in that marriage year.

Second, we are worried that women being married for a long time would forget episodes from early in the marriage and therefore misreport the timing of the first violent episode (see Cools et al., Citation2020). The hazard rates in the figure support this suspicion, as women above their fifth marriage year tend to heap their reporting on 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years since marriage.Footnote11

In addition to this, we also remove visitors and females that have moved to a new location after the first violent episode. We do this since we are unable to allocate these violent episodes to a particular block.Footnote12 In total, our estimation sample consists of 11,151 marriage-years at risk, based on 4704 married women from 2223 blocks in 28 Indian states. In , we provide some key statistics from this estimation sample. The average number of MGNREGA workers fell steadily during our study period. In contrast, the number of job card applications was more or less stable – suggesting an increasing unmet demand for MGNREGA jobs. The female ratio, measured as the number of days worked by females over the total numbers of days worked, rose somewhat from 2012 to 2015.

Table 1. Summary statistics, MGNREGA

4. Empirical framework

In this section, we describe the empirical framework.

4.1. Main specification

Our empirical investigation is based on within-block variation in the number of MGNREGA workers over time. We run the following baseline specification:

(1)

(1)

where IPVibt denotes whether woman i from block b experienced intimate partner violence for the first time in year t, αb denotes block fixed effects, αm denotes years-since-marriage fixed effects, αa denotes (five years) age-group fixed effects, while αt denotes year fixed effects.

is a set of time-invariant individual characteristics (dummy variables for Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Buddhist, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes).Footnote13 We use the number of workers as our main measure of local MGNREGA prevalence. Our coefficient of interest is β1, which captures the relationship between MGNREGA and the likelihood of experiencing violence for the first time in a particular year.Footnote14

As the work programme is built on a principle of self-selection one might worry that programme participants are different from non-participants, also in their inclination to partner violence. It is important to stress that our setup does not use information on employment at the individual level – instead we explore the local prevalence of the work programme. The main threat to this approach is unobserved time-varying shocks that are correlated with MGNREGA employment, for example, negative income shocks that both increase the demand for work and that trigger more violence.

Our key argument is that such shocks do not automatically translate into more MGNREGA employment. Extensive research shows that implementation often is hindered by a number of hold-ups, and that the availability of jobs crucially depends on the will of local politicians and bureaucrats (see Section 2). Female employment is particularly likely to be unresponsive to demand shocks, we believe, as women’s participation depends on work being provided close to residence. We therefore find it plausible that year-to-year changes in programme implementation at the local level are quasi-exogenous to factors determining the prevalence of intimate partner violence. We explore this further below.

4.2. Assessing the empirical approach

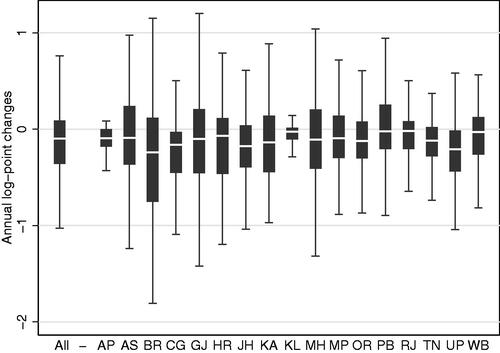

illustrates our identifying variation. The figure is a whiskers plot of the within-block time variation in the number of MGNREGA jobs (in log-points). The first plot is based on all blocks in our estimation sample, while the rest of the figure displays whiskers plot by the major Indian states. As can be seen, there is substantial year-to-year variation. Our conjecture is that this within-block variation is driven primarily by availability of jobs, not local demand. We test whether our data are consistent with this using the indicators of droughts and night-time light.

Figure 2. Annual changes in the number of MGNREGA workers, log-points.

Notes: The figure shows a whisker plot of annual log-point changes in the number of MGNREGA workers, based on the 2259 blocks in our estimation sample. The vertical boxes denote the 25th (lower hinge) and the 75th percentile (upper hinge).

Droughts can have significant adverse effects on agriculture production, and hence, on the income of many poor farmers (Kumar et al., Citation2014). A priori, we would therefore expect demand for the relatively low-paid MGNREGA jobs to increase during periods of droughts.Footnote15 We test this by regressing the number of job card applications on the drought indicators. Estimates are shown in the first two columns of . As can be seen, we find a strong and positive relationship between these variables, meaning that there are more job card applications in drought years. In the fourth and fifth columns, we run the same regressions using our main treatment variable, the number of MGNREGA workers, on the left-hand side. Reassuringly for our empirical setup, we find no significant relationship with the drought indicators. What this suggests is that local income shocks that affect demand for MGNREGA jobs do not affect actual employment at the local level.

Table 2. Relationship between MGNREGA, droughts, and night-time light

We use the amount of night-time light as a second indicator of local economic activity. This serves as a useful complement to the drought indicators, as night-light is likely to capture activities outside of agriculture (since agricultural production usually takes place during the day and therefore emits little light). Night-time light has also been shown to exhibit a reasonable correlation with overall economic activity in India (Prakash et al., Citation2019). It is still somewhat unclear exactly what night-light captures in rural areas.Footnote16 In the third column of , we present a regression of the number of job card applications on log night-time light, and we find a strong and negative relationship. This implies that there are more job card applications when the amount of light (and presumably economic activity) is lower. In the sixth column, we repeat this regression with the number of workers as the dependent variable. As for the drought indicators, we find no significant relationship.

In sum, we interpret the results in as support for our conjecture, that local time variation in MGNREGA employment is caused primarily by the availability of jobs.

5. Findings

In this section, we present our empirical findings and discuss likely mechanisms.

5.1. Main results

Our main results based on EquationEquation (1)(2)

(2) are presented in . In the first column, we do not include any controls, except the block fixed effects. The MGNREGA-coefficient is positive and highly significant. In the rest of the table, we gradually include years-since-marriage fixed effects, age-group fixed effects, year fixed effects and individual time-invariant controls. The year fixed effects reduce the coefficient somewhat, while the other fixed effects and controls barely have any impact. Our preferred estimate is shown in the fifth column and suggests that a 10 per cent increase in the number of workers raises the probability of violence by 0.08 percentage point.

Table 3. Impact of MGNREGA on intimate partner violence

One way of illustrating the magnitude of this effect is to compare the coefficient with the average yearly risk of violence in the estimation sample, of 6.1 per cent. Compared to this average, the estimated impact of a 10 per cent increase in MGNREGA amounts to a 1.3 per cent increase in violence, which is substantial.

As mentioned, the main threat to our estimation is unobserved time-varying shocks that are correlated with the number of MGNREGA jobs. To test whether our estimates are confounded by underlying trends in either violence or MGNREGA, we first regress violence in year t on changes in MGNREGA in year t + 2. Estimates are shown in the first column of . Reassuringly, future changes in employment have no effect on violence.

Table 4. Placebo and alternative time trends

In the rest of the table, we explore how sensitive our estimates are to alternative time trends. In Columns 2 to 5, we subsequently add a common time trend, state-specific trends, district-specific trends and block-specific trends. In Column 6, we include year × state fixed effects. Overall, the estimates are robust to all of these different specifications. In the appendix, we additionally show that our results survive the inclusion of various time-varying controls, including the number of job card applications, the drought indicators and the amount of night-time light.

5.2. Mechanisms

Our estimates suggest that MGNREGA leads to more domestic violence against women. A natural interpretation is that the effect is caused by female employment, as women barely participate in the regular labour market but occupy about half of the workdays in the programme. Below we investigate how plausible this interpretation is.

The MGNREGA Public Data Portal provides data on total workdays by gender. As a first test, we use these data to construct separate measures for men and women. The estimates in clearly suggest that the effect on violence is driven by female employment. Although imprecisely estimated, the regression in fact suggests that male employment reduces violence against women. This result is consistent with other findings in the literature. For example, Bhalotra et al. (Citation2018) find that beneficial female labour market conditions increase violence, while beneficial labour market conditions for males have the opposite effect.

Table 5. Impact of gender-specific MGNREGA on intimate partner violence

As a second test, we investigate whether the relationship between MGNREGA and violence depends on the level of female labour force participation outside of the work programme. To do so, we run the following specification:

(2)

(2)

where FLPb denotes female labour force participation. In the first column of , we use the measure from the Economic Census of 2013. For easy interpretation, we standardise labour force participation to mean zero and standard deviation one. As can be seen, the interaction coefficient is negative and statistically significant, meaning that the effect of MGNREGA on violence is smaller in areas with relatively high female labour force participation. In the second column, we interact MGNREGA with a simple dummy variable, taking the value of unity for blocks with a below median female labour force participation. The interaction coefficient is positive, but imprecisely estimated.

Table 6. Heterogeneity of MGNREGA effect by female labour force participation (LFP)

In Columns 3 and 4, we run similar regressions using the NSS measure of female labour force participation at the level of districts. The estimates in the third column are similar to those in the first column but less precisely estimated. The estimates in the fourth column suggest that the effect of employment on violence is driven entirely by districts with a female labour force participation below the median in the sample.Footnote17

In sum, the above results suggest that the effect on violence is largest in areas where the programme has the greatest impact on whether or not women are working, and not just on the number of days they work. Thus, the results are consistent with female employment being the mechanism.

Low levels of female labour force participation are likely to be associated with strong norms against female employment. Hence, our estimates are also consistent with ‘male backlash’ theories, where husbands turn to violence to regain power within the marriage.Footnote18 This is in line with the findings of Heise and Kotsadam (Citation2015), who document that the relationship between violence and female employment is stronger in countries with less gender equality, and Tur-Prats (Citation2017), who document that relatively better labour market conditions for females lead to more intimate partner violence in Spain, but only in areas with deep-rooted norms against female employment.

6. Conclusion

The literature on domestic violence and female employment is largely inconclusive, both theoretically and empirically. One argument is that employment improves women’s outside option of marriage, which might protect them from violence. Consistent with this, Aizer (Citation2010) and Anderberg et al. (Citation2016) find that favourable labour market conditions for females reduce domestic violence in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. The outside-option argument is however likely to be less relevant in patriarchal societies, like much of rural India, where the threat of divorce is practically non-existing. Female employment could in such societies lead to more violence by threatening male identity. Indeed, empirical studies from low-income countries often identify a positive relationship between employment and intimate partner violence (Bhalotra et al., Citation2018; Cools & Kotsadam, Citation2017; Guarnieri & Rainer, Citation2018; Luke & Munshi, Citation2011), but not always (Kotsadam & Villanger, Citation2020).

We add to this literature by studying the effect on intimate partner violence of the large public work programme, MGNREGA. To do so, we combine detailed administrative data on employment with household survey data from rural India. Our main result is that more female employment leads to more violence. In our preferred specification, we find that a 10 per cent increase in the number of MGNREGA jobs raises the probability of violence against women by about 1.3 per cent of the baseline level.

We also investigate heterogeneity of the relationship between violence and employment and find that the effect is strongest in areas with low female labour force participation. This is the areas that are likely to have the strongest norms against female employment. Thus, our findings are consistent with other studies showing that the risk of violence due to women working is largest in societies where the norms against female employment is strongest (Heise & Kotsadam, Citation2015; Tur-Prats, Citation2017; Vyas & Watts, Citation2009).

A recurring suggestion for how to improve female empowerment is to facilitate work outside the household. Globally, there is also a clear tendency of increased female labour force participation (Heath & Jayachandran, Citation2016). Our results are important in this context, and they suggest that efforts to stimulate employment should be combined with other types of efforts, such as combating patriarchal gender norms.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mathieu Couttenier and Lore Vandewalle for helping us with gathering data on droughts and to Andreas Kotsadam and Kalle Moene for useful discussions and suggestions. Replication files are available at: Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/ypw6bwdsyn.1

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Field et al. (Citation2019) study the effects on empowerment and domestic violence of depositing wages from MGNREGA directly into females’ bank account.

2 Sarma (Citation2022) uses the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) to provide supporting evidence for her findings at the household level. This evidence is only ‘supporting’, as the IHDS has a very small sample size, and most importantly, as the survey only asks respondents whether domestic violence is common in their communities, not about their own personal experiences.

3 We use the Census of India as an intermediator when doing this merge. The NFHS displaces the survey clusters by up to 5 km to assure anonymity. Because of this, we do not merge our data on finer geographical levels than blocks.

4 See Kotsadam and Villanger (Citation2020) for a nice overview of this literature.

5 Fifty-five per cent of all women having paid work outside agriculture in rural India work in their own village, according to the 2011 Census, and only 14 per cent commute more than 5 km. In contrast, 35 per cent of men having similar type of work commute more than 5 km.

6 In addition, a randomly selected 1 per cent of the rural clusters are displaced by up to 10 km.

7 Most of our other data are for calendar years. We match the financial year of 2011-2012 to the calendar year 2012, and so forth. This essentially implies that the MGNREGA data are lagged by 9 months compared to the violence data.

8 We define these based on standard thresholds. Extreme droughts are defined by SPEI ≤−2, while severe drought are defined by −2 < SPEI ≤−1.5.

9 We use the matching keys provided in the Shrug database (Asher et al., Citation2019) to merge the Economic Census to the Census of India 2011.

10 MNGREGA is not coded as a separate ‘principal activity’. To assure that we do not include this in our measure of labour force participation, we do not count females as participating in the labour market when they report employment in the ‘public sector’ as the principal activity and MGNREGA employment during the previous year.

11 Clearly, there might also be recall errors in the reported year of marriage. However, given that marriage is an important event for women in rural India, we do not believe this is an important issue in our context, particularly not for the sample of recently married women.

12 This restriction has very little impact on our estimates.

13 We do not include time-varying characteristics, such as asset ownership and educational attainments, as we only have this information from the survey date, and as such variables potentially could be affected by MGNREGA or violence.

14 To deal with zeroes, we use the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation (IHS) wherever we mention logs. Our main coefficient in (1) can be interpreted in the same way as with a log-transformation, but unlike the log, the IHS is defined for the value of zero (Burbidge et al., Citation1988).

15 In our estimation sample, about 4 per cent of the marriage years include an extreme drought, while 25 per cent include either an extreme or a severe drought.

16 Pérez-Sindín et al. (Citation2021) find that night-light is a good proxy for rural economic activity in Colombia.

17 In addition, we have tested for heterogeneity in terms of the following characteristics: total population, population share of SCs and STs, and availability of publicly provided goods from the Census, and average consumption expenditure and poverty rate from the NSS. We do not find a significant interaction coefficient for any of these variables. The results are available upon request.

18 In , we measure female labour force participation using the Economic Census of 2013, which coincides with our period of analysis. To potentially better capture long-term norms against female employment we repeat the heterogeneity analysis using measures of past prevalence of female labour force participation from the Economic Census of 1998. These regressions yield very similar results, as can be seen from .

References

- Aiyar, Y., & Samji, S. (2009, February). Transparency and accountability in NREGA: A case study of Andhra Pradesh (Working Paper No. 1). Accountability Initiative.

- Aizer, A. (2010). The gender wage gap and domestic violence. American Economic Review, 100, 1847–1859. doi:10.1257/aer.100.4.1847

- Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and Identity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 715–753.

- Amaral, S., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Sensarma, R. (2015). Employment programmes for the poor and female empowerment: The effect of NREGS on gender-based violence in India. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 27, 199–218.

- Anderberg, D., Rainer, H., Wadsworth, J., & Wilson, T. (2016). Unemployment and domestic violence: Theory and evidence. The Economic Journal, 126, 1947–1979. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12246

- Angelucci, M. (2008). Love on the rocks: Domestic violence and alcohol abuse in rural Mexico. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 8(1), 1–43.

- Asher, S., Lunt, T., Matsuura, R., & Novosad, P. (2019, February). The socioeconomic high-resolution rural-urban geographic dataset on India (SHRUG) (Working paper, ref. no. C-89414-INC-1). International Growth Centre.

- Asher, S., & Novosad, P. (2017). Politics and local economic growth: Evidence from India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(1), 229–273.

- Atkinson, M. P., Greenstein, T. N., & Lang, M. M. (2005). For women, breadwinning can be dangerous: Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1137–1148.

- Beguería, S., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., & Angulo-Martínez, M. (2010). A multiscalar global drought dataset: The SPEIbase: A new gridded product for the analysis of drought variability and impacts. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 91, 1351–1354.

- Bertrand, M., Kamenica, E., & Pan, J. (2015). Gender identity and relative income within households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 571–614.

- Bhalotra, S. R., Kambhampati, U. S., Rawlings, S., & Siddique, Z. (2018, January). Intimate partner violence and the business cycle (IZA Discussion Paper No. 11274). Institute of Labor Economics.

- Bulte, E., & Lensink, R. (2019). Women’s empowerment and domestic abuse: Experimental evidence from Vietnam. European Economic Review, 115, 172–191.

- Burbidge, J. B., Magee, L., & Robb, A. L. (1988). Alternative transformations to handle extreme values of the dependent variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 123–127.

- Cools, S., Flatø, M., & Kotsadam, A. (2020). Rainfall shocks and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 57, 377–390.

- Cools, S., & Kotsadam, A. (2017). Resources and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 95, 211–230.

- Dasgupta, S., & Sudarshan, R. (2011, February). Issues in labour market inequality and women’s participation in India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme (Working Paper No. 98). ILO, Policy Integration Department.

- Doyle, J., & Aizer, A. (2018). Economics of child protection: Maltreatment, foster care, and intimate partner violence. Annual Review of Economics, 10, 87–108.

- Dutta, P., Murgai, R., Ravallion, M., & Van de Walle, D. (2014). Right to work? Assessing India’s employment guarantee scheme in Bihar. The World Bank.

- Eswaran, M., & Malhotra, N. (2011). Domestic violence and women’s autonomy in developing countries: Theory and evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 44, 1222–1263.

- Farmer, A., & Tiefenthaler, J. (1997). An economic analysis of domestic violence. Review of Social Economy, 55, 337–358.

- Fearon, J., & Hoeffler, A. (2014, August). Benefits and costs of the conflict and violence targets for the post-2015 development agenda (Working Paper). Copenhagen Consensus Center.

- Field, E. M., Pande, R., Rigol, N., Schaner, S. G., & Moore, C. T. (2019, September). On her own account: How strengthening women’s financial control affects labor supply and gender norms (NBER Working Paper No. 26294). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Guarnieri, E., & Rainer, H. (2018, July). Female empowerment and male backlash (CESifo Working Paper No. 7009). CESifo.

- Gulzar, S., & Pasquale, B. J. (2017). Politicians, bureaucrats, and development: Evidence from India. American Political Science Review, 111, 162–183.

- Gupta, B., & Mukhopadhyay, A. (2016). Local funds and political competition: Evidence from the national rural employment guarantee scheme in India. European Journal of Political Economy, 41, 14–30.

- Heath, R. (2014). Women’s access to labor market opportunities, control of household resources, and domestic violence: Evidence from Bangladesh. World Development, 57, 32–46. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.028

- Heath, R., & Jayachandran, S. (2016, October). The causes and consequences of increased female education and labor force participation in developing countries (NBER Working Paper No. 22766). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 3, 332–340.

- Hornung, C. A., McCullough, B. C., & Sugimoto, T. (1981). Status relationships in marriage: Risk factors in spouse abuse. Journal of Marriage and Family, 43, 675–692.

- Imbert, C., & Papp, J. (2015). Labor market effects of social programs: Evidence from India’s employment guarantee. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(2), 233–263.

- Jewkes, R. (2002). Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet, 359, 1423–1429. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5

- Khera, R., & Nayak, N. (2009). Women workers and perceptions of the national rural employment guarantee act. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(43), 49–57.

- Khosla, R. (2011). Caste, politics and public good distribution in India: Evidence from NREGS in Andhra Pradesh. Economic & Political Weekly, 46(12), 63–69.

- Kishor, S. (2005, April). Domestic violence measurement in the demographic and health surveys: The history and the challenges (United Nations Expert Paper). UN Division for the Advancement of Women.

- Kjelsrud, A., & Kotsadam, A. (2021, November). Female employment and voter turnout – Evidence from India (Working paper). Oslo Business School, OsloMet.

- Kjelsrud, A., Moene, K., & Vandewalle, L. (2020, August). The Political competition over life and death – Evidence from infant mortality in India (Working Paper No. HEIDWP10-2020). The Graduate Institute of Geneva.

- Klasen, S., & Pieters, J. (2015). What explains the stagnation of female labor force participation in urban India? The World Bank Economic Review, 29, 449–478.

- Kotsadam, A., & Villanger, E. (2020, February). Jobs and intimate partner violence - Evidence from a field experiment in Ethiopia (CESifo Working Paper No. 8108). CESifo.

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360, 1083–1088.

- Kumar, P., Joshi, P. K., & Aggarwal, P. (2014). Projected effect of droughts on supply, demand, and prices of crops in India. Economic & Political Weekly, 49, 54–63.

- Luke, N., & Munshi, K. (2011). Women as agents of change: Female income and mobility in India. Journal of Development Economics, 94, 1–17.

- Macmillan, R., & Gartner, R. (1999). When she brings home the bacon: Labor-force participation and the risk of spousal violence against women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 947–958.

- Maiorano, D. (2014). The politics of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in Andhra Pradesh. World Development, 58, 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.006

- Mehrotra, S., & Sinha, S. (2017). Explaining falling female employment during a high growth period. Economic & Political Weekly, 52(39), 54–62.

- Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. (2012). MGNREGA Sameeksha, an anthology of research studies on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, 2006-2012. Orient BlackSwan.

- Palermo, T., Bleck, J., & Peterman, A. (2014). Tip of the iceberg: Reporting and gender-based violence in developing countries. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179, 602–612.

- Pérez-Sindín, X. S., Chen, T.-H. K., & Prishchepov, A. V. (2021). Are night-time lights a good proxy of economic activity in rural areas in middle and low-income countries? Examining the empirical evidence from Colombia. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 24, 100647.

- Prakash, A., Shukla, A. K., Bhowmick, C., & Beyer, R. C. M. (2019). Night-time luminosity: Does it brighten understanding of economic activity in India? Reserve Bank of India occasional Papers, 40(1), 1–24.

- Ravi, S., & Engler, M. (2015). Workfare as an effective way to fight poverty: The case of India’s NREGS. World Development, 67, 57–71.

- Sarma, N. (2022). Domestic violence and workfare: An evaluation of India’s MGNREGS. World Development, 149. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105688

- Tur-Prats, A. (2017, April). Unemployment and intimate-partner violence: A gender-identity approach (Working Paper No. 963). Graduate School of Economics.

- Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S., & López-Moreno, J. I. (2010). A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. Journal of climate, 23, 1696–1718. doi:10.1175/2009JCLI2909.1

- Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S., López-Moreno, J. I., Angulo, M., & El Kenawy, A. (2010). A new global 0.5 gridded dataset (1901-2006) of a multiscalar drought index: Comparison with current drought index datasets based on the Palmer Drought Severity Index. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 11, 1033–1043. doi:10.1175/2010JHM1224.1

- Vyas, S., & Watts, C. (2009). How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development, 21, 577–602.

Appendix

Table A1. Impact of MGNREGA on intimate partner violence, controlling for time-varying variables

Table A2. Heterogeneity of MGNREGA effect by past female labour force participation (LFP)