Abstract

Developing countries face uncertain trajectories for growth in the twenty-first century, with many finding themselves a ‘middle-income trap’. Extant theories in the politics of development that focus on domestic institutional strength and weakness represent necessary but not fully sufficient explanations for the trajectories of middle-income countries. In order to explain uncertain and uneven development outcomes in an era of heightened globalisation, this article seeks to explore the impact of international institutions, specifically the post-Cold War structures of trade and investment and global value chains, on the possibilities for growth for middle-income countries. The particular character of rules and norms defining trade and investment and the power dynamics behind their design suggest that international institutions as well as domestic factors explain disappointing and increasingly unequal development outcomes among middle-income countries.

Developments during the 2010s have highlighted globalisation’s drawbacks, after decades of enthusiasm for the project of international economic integration. Yet there remains a common consensus that increasing integration is essential for developing countries to grow, following a long-established dictum that trade, rather than aid or import-substituting industrialisation, represents the most plausible path for developing countries to achieve sustainable growth trajectories. Some commenters have argued against recent scepticism of trade in the western world precisely because of dire consequences for developing countries (Drezner Citation2019; Matfess Citation2019).

Economic outcomes among middle-income countries that have enthusiastically adopted international economic integration suggest a less sanguine view. From the 1990s until the mid-2000s, many outward-oriented emerging economies made progress, buoyed by global expansion and the commodities boom. Such optimism has given way to greater uncertainty and stasis; successful exporters have seen their growth trajectories falter relative to the earlier developers. The middle-income trap has emerged as a possible fate for many developing countries, signalling uncertain prospects for growth in the context of globalisation (Gill & Kharas, Citation2007, Citation2017).

Comparative studies of national development tend to treat growth outcomes as solely a function of domestic institutional quality. They explain rapid growth by the ability of state institutions to mobilise resources, coordinate actors, form coalitions, upgrade their capacities and thus compete in valuable global markets. In so doing, they implicitly frame these markets as open fields of opportunity for those capable of taking advantage. There is little theoretical scope for arguing that global markets, and the institutions that support them, might themselves have contributed to the middle-income trap.

This article argues that the global institutions that have governed economic integration in the post-Cold War era may in fact be the source of many of the growth constraints faced by developing countries. They have done so through the setting of agendas, the writing and revising of rules and norms, and the assignment of national economies into different production niches. This heightens the competition among developing countries for a place in higher value-added production among global value chains. It also limits the scope for demand in independently upgrading domestic capacities, because multinational firms taking advantage of international institutions vigorously control higher value-added activities are unlikely to reward upgrading investments independent of their own strategies. This significantly constrains the autonomous destinies of countries seeking growth through export and foreign direct investment. Far from following the benign objectives of lowering transactions costs, such institutions have made it more difficult for most developing countries to follow the growth trajectories of earlier developers.

This article explores two international institutional configurations. First, international institutions of trade and investment after the Cold War, represented by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and complementary trade and investment agreements, have given multinational firms greater and developing countries less autonomy in formulating arrangements of trade and investment, relative to the past. Second and relatedly, global value chains – multinational-led institutional arrangements that disaggregate production into the manufacturing of components across many countries – constrain the autonomous development of higher value-added production by developing countries, by determining which components of what value will be assigned to which firms and countries. In so doing, they actively suppress the demand for the upgrading of domestic institutions that is seen as the key activity for middle-income escape in all but a handful of cases.

The cumulative impact of these institutions represents a set of individual constraints on development trajectories. Countries who developed earlier and thus under a more forgiving international environment, in which international engagement and domestic upgrading supported one another, were able to capture high-value niches in global production and graduate from middle-income status. Among current middle-income countries, relatively few countries are serious contenders for middle-income graduation. They must compete with one another to achieve middle-income status through attempting to occupy and maintain high value-added niches in global production networks, and they are favoured by multinational investment at different levels for varied reasons that often have little to do with institutional virtue. Most other middle-income countries aspire to reach the level of success even of these contenders. These aggregate outcomes are imperfectly predicted by differences in domestic institutional capacity and autonomous efforts at domestic upgrading.

The quality of domestic institutions remains an important explanation for predicting success and failure across developing country cases. This article provides a more cohesive assessment of the challenges facing middle-income countries as a whole over the last thirty years, however, including the ways in which international institutions can shape domestic institutional quality. The difference is like that between running a long-distance race on a track or over snow; in both, the most capable runners might win the race, but in the latter, all would have a harder time and fewer might finish the course. But further, this article argues that that the external institutional environment might effectively prevent the upgrading of domestic institutions, by not providing the demand and the inputs necessary for such upgrading to translate into more valuable positions in production networks. Focussing solely on the internal capacities of individual developing countries to overcome the middle-income trap neglects the idea that particular institutional arrangements in the global economy may be making upgrading and thus escape from the middle-income category more difficult. The strategies of multinationals in structuring global production, supported by the changing institutions of trade and international investment, thus have a powerful influence on the destinies of middle-income countries that has been neglected by scholars and policymakers.

1. State strength, international institutions, and the middle-income category

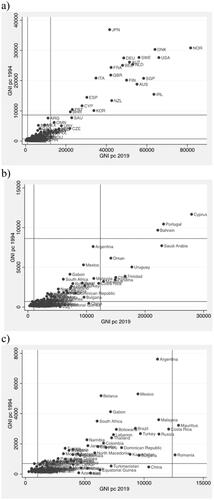

The middle-income trap represents an empirical phenomenon; many developing countries have managed to overcome the initial barriers of development in the transition from LDC status but face new and more daunting challenges in their quest to leave their status as developing countries altogether; many are stagnating. In order to engineer escape, most countries in the developing world have pursued export-oriented strategies and sought to attract foreign direct investment – over the last two decades, exports have more than doubled and FDI nearly quadrupled as a share of GDP for middle-income countries on average – but only a very small number of countries have graduated from the middle-income category through strategies of international integration. Of those 46 countries that are high income in 2019, only 12 were plausibly middle-income on the eve of the creation of the WTO in 1994. Of these, several are countries that entered the European Union; others, such as Oman and Panama, are countries with little industry. represents empirical snapshots of the middle-income category, in 1994 and 2019, excluding countries with populations under one million.

Figure 1. The middle-income category, 1994 and 2019.

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Note: The first and second lines represent low-middle income and middle-high income thresholds, respectively.

The second and third graphs reflect the few countries that were middle-income in 1994 and have succeeded in graduating since. East Asian ‘miracle’ economies had already graduated from middle-income status by the early 1990s; since then, no economy has graduated from middle-income status through export-led industrial development, at least absent other factors that explain their graduation. Given the overwhelming emphasis on exports and foreign investment in discussions of the development of middle-income countries, this article will largely explore the links between international integration and national growth.

1.1. The political economy of the middle-income trap

Most analysts have located unevenness of cross-national growth in variation in domestic policies or institutions. Economists have argued that specific development policy frameworks appropriate for middle-income countries today involve such activities as technological investments and export orientation, the nourishing of entrepreneurship and innovation and measures to address inequality and corruption (Eichengreen, Park, & Shin, Citation2013; Gill & Kharas, Citation2007; Paus, Citation2012). The key to middle-income trap escape lies with abandoning current product markets, making investments in new technologies, and expanding the supply of skilled workers; this requires domestic political change and the formation of ‘upgrading coalitions’ among political and economic actors, as governments must abandon the support of extant elites that might object to disruption and clientelistic networks of firms and workers demanding protection (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016; Iversen & Soskice, Citation2019, p. 30). In a recent special issue, an interdisciplinary group of scholars proposed a ‘political economy of development’ approach to the challenges of the middle-income trap; while acknowledging increased international competition, they emphasise domestic upgrading and innovation through coordination between public authorities and private actors (Kang & Paus, Citation2020).

Thus, the quality of domestic institutions has dominated scholarly and policy-making discussions of the middle-income trap; upgrading, competitiveness and thus middle-income graduation are largely understood to be a function of domestic political dynamics. When the external environment and its institutions are mentioned, it is often to highlight opportunities rather than constraints, such as how entering trade agreements might ‘pre-commit’ developers to domestic reform (Büthe & Milner, Citation2008; Gill & Kharas, Citation2017, p. 18). This forecloses the possibility that upgrading might actually require active international engagement, and that institutional frameworks complicate such engagement, on which more below.

1.2. Domestic institutions vs. international institutions

Specific arguments about the middle-income trap are nested within a much larger tradition that associates strong states and development. The comparative politics of national development has focussed on domestic institutions, largely to the exclusion of international factors, in the analysis of growth outcomes. In particular, scholars of the developmental state have explained remarkable economic successes of East Asian countries from low levels of development through mobilisation of powerful state institutions in order to accumulate capital, discipline the private sector, manage labour-capital relations and arrange for productive, long-term relationships with the international economy (see Haggard, Citation2018). Scholarship in institutional economics has explained cross-national variation in development through the presence or absence of inclusive domestic institutions that protect property rights, enforce contracts and enable innovation (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; North, Wallis, & Weingast, Citation2008). The World Bank has increasingly emphasised domestic institutional quality as central to growth outcomes.

Extant explanations have thus understood state capacity and enabling social structures as determining higher value-added export orientation, which determines relative successes in economic development and middle-income graduation (see Chang, Citation2002; Rodrik, Citation1997 for exceptions). Contrariwise, failures in economic growth are often traced back to failures in upgrading and export orientation strategies, which are then attributed to weaknesses in the state or domestic institutions, the prevalence of rent-seeking or interest-group resistance. Given the overriding emphasis on domestic capacity for explaining outcomes, external actors and institutions are rarely framed as malign influences in the dilemmas of national development since the decline of dependency theory in the 1990s (see Amsden, Citation2003).

At the same time, the rise of neo-liberal institutionalism in international political economy (IPE) presented global institutional frameworks as straightforwardly lowering the costs of transaction across borders and thus enabling both positive-sum cooperation and growth through expanded product and factor markets (Haggard & Simmons, Citation1987; Keohane, Citation1984). Their application to the domestic political economy of development – through ‘open economy politics’ – focussed on the ways that petty domestic politics might forestall beneficial policies of international integration (Büthe & Milner, Citation2008; Frieden & Rogowski, Citation1996; Milner, Citation1998; Milner & Kubota, Citation2005). Implicit in these analyses is that greater openness to trade and investment is unambiguously good for development, due to efficiency gains – although not inevitable due to domestic opposition – and that greater engagement with international institutions can facilitate this cooperation.

More recent work in international political economy has highlighted the dynamics of power operating within international institutional contexts, suggesting some scepticism as to the inherently positive-sum qualities of international economic integration (Barnett & Duvall, Citation2005; Drezner, Citation2008; Stone, Citation2011). But IPE scholars rarely apply the particular impact of power relations at the international level to dynamics within national political economies beyond advanced industrialised countries (see Farrell & Newman, Citation2015). Scholarship on the politics of development has meanwhile highlighted the ways that international institutions might be beneficial to workers and citizens within developing countries by constraining the options of developing country governments (A. Evans, Citation2021; Hafner-Burton, Citation2009).

In the study of the politics of national development today, international institutions are generally absent. This reinforces a focus on domestic institutions and their internal capacities and incentives to upgrade. In research into the middle-income trap, therefore, international institutions are treated as fixed parameters and not usually primary objects of inquiry for explaining either development or underdevelopment. This article suggests, by contrast, that international institutions can shape the terms of competition, leading to more countries ending up in the middle-income trap than under previous institutional regimes of the global economy, while limiting the scope of the upgrading that may represent a direction of escape.

While scholars have recognised the difficulties of escaping the middle-income category – Paus (Citation2020) refers to the ‘Red Queen Effect’, where countries have to run faster and faster just to stay still – extant analysis has not dwelt on how difficult this escape is and how few succeed in this pursuit. If the high-income category is a club, it would be an exclusive one indeed. This exclusivity raises questions of exactly how likely it is for developing countries to join, and indeed, whether long-standing members, and the rules they write for membership, might be acting to increase competition and restrict entry. The relative rarity of graduation from the middle-income category in the age of globalisation suggests that there might be institutional aspects of the international economy that are making the playing field more challenging relative to earlier developers, and that the design and operation of international institutions might be playing a role in this process. The next two sections will illustrate the dimensions of this impact, and the subsequent section discusses how international institutions might constrain the scope for domestic upgrading more specifically.

2. The institutions of trade and investment

Formal-institutional frameworks of trade and investment after the Cold War have had the cumulative effect of making middle-income graduation difficult. In the period between the end of World War II and of the Cold War, these dynamics were less in evidence. The framers of the postwar international order constructed institutions that would return higher levels of trade and investment to the international economy while also protecting the prerogatives of national sovereignty, or ‘embedded liberalism’ (Ruggie, Citation1982). Developing countries, particularly those just emerging from colonial rule, were at a structural disadvantage in this environment, despite rhetorical support for trade as a means to development (Gowa & Kim, Citation2005). Singh (Citation2017) has argued that individual developing countries have received trade concessions from forceful negotiation rather than such paternalism.

Nevertheless, the autonomy of developing countries was not entirely absent. It was most evident in foreign direct investment; countries sought and achieved important concessions from multinationals eager for access to still protected but increasingly valuable markets, including local content requirements and technology transfer (P. Evans, Citation1979). The success of trade integration for developing countries was more ambivalent (Aggarwal, Citation1985). But as developing countries demanded greater inclusion through the UN Conference on Trade and Development, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) responded by establishing a more inclusive ‘generalized system of preferences’ for poorer countries (see Krasner, Citation1982, Citation1985).

In the 1980s and early 1990s, however, the political strength of and solidarity among developing countries collapsed. Global recession, debt crises and fiscal unsustainability led the IMF and World Bank to establish structural adjustment programs, resulting in the retrenchment of the capacity of the state to govern the domestic economy across the developing world (see Naseemullah, Citation2017). The effects of reform programs on trade protection were explicit; conditionalities included the lowering of tariffs and the elimination of quotas and export licencing (Holmes & Jonas, Citation1984). Attracting foreign investment, even at adverse terms, seemed necessary to achieve macroeconomic stability. More generally, this period represented the triumph of notion that markets and private actors rather than states should govern economic interaction both within and across borders (see Ikenberry, Citation2001).

The most significant development of the trade regime after the Cold War was the birth of the WTO during GATT’s Uruguay Round in 1995. While most analysts acknowledge the significance of the creation of the WTO, they see broad continuity between the WTO and previous rounds of GATT. Yet that continuity masked substantial change in the means and ends of the overall institutional framework. At the close of the Uruguay Round, GATT 1947 was replaced by GATT 1994, a substantively similar but legally distinct instrument that created the WTO (Barton, Goldstein, Josling, & Steinberg, Citation2006, pp. 5–6). Following a stalemate over new areas of trade liberalisation seen as detrimental to developing countries, the United States and the EU withdrew completely from GATT 1947, threatening recalcitrant developing countries with permanent exclusion from their markets unless they acceded to the new rules to become WTO members (Barton et al., Citation2006, p. 167; Stone, Citation2011, p. 97). The nature of this ‘single undertaking’ was negotiated only among developed countries; for others, the options were to accept all its outcomes or reject them completely and risk exclusion (Steinberg, Citation2002).

The actual substance of the Uruguay Round settlement was presented as a grand bargain: developing countries would accede to new regulations in intellectual property, investment and trade in services in return for concessions on access to the industrial and agricultural markets of wealthy countries (Ostry, Citation2003). This bargain turned out to be one-sided, however. These negotiations did not lead to significantly greater access to US and EU agricultural markets (Gallagher, Citation2007). Industrial access was limited to the phasing out of the discriminatory Multi-Fiber Agreement in the relatively low-value textiles sector.

Changes in the operation of these institutions increased the power and autonomy of multinationals to determine the nature of trade and investment, relative to developing countries. This is because the objectives of the WTO shifted dramatically away from removing protectionist policies – tariffs, quotas, export licences, subsidies – towards the harmonisation of differences in domestic laws, regulations and practices among countries that have been interpreted as ‘non-tariff barriers’ to frictionless cross-border exchange. There were thus fundamental discontinuities between the two aims of the trade regime, both in terms of what trade itself means and the extent to which sovereignty is consistent with trade liberalisation (Barton et al., Citation2006, pp. 19–21).

Regulatory harmonisation has significant consequences for the autonomy of national developmental trajectories. It gives great power to those who determine the nature of regulatory norms. Farrell and Newman (Citation2015, pp. 499–505) argue that, in instances of regulatory clashes among Atlanticist economies, firms with superior resources and access to information are likely to drive new supranational regulatory norms. A natural corollary to that argument is that the most powerful firms in the most powerful countries can set transnational regulatory norms for both developed and developing countries (see Baldwin, Citation2007).

The attachment of particular regulatory issues – intellectual property, trade in services and investment – to trade liberalisation was a key part of the politics behind this shift. In the build-up to the Uruguay Round, technology- and services-intensive multinationals lobbied US and European governments to include these subsidiary agreements as part of the non-negotiable conditions of WTO membership. US and European negotiators then used the threats of trade sanctions to universalise stringent regulatory interpretations in these areas and impose these on developing countries, with concessions only in the speed of implementation. The Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) provision was predicated on global implementation of a radically expansive understanding of intellectual property rights sought by US and European multinationals, replacing the incremental approaches of the World Intellectual Property Organization (Drahos, Citation1995). While some argue that the more rigorous protection of property rights solves market failure that constrains innovation, there is little evidence that the previous order was stifling innovation or that increasing the strength and duration of patent protection has actually led to more innovation. Moreover, there has been significant domestic pushback to the proliferation of patents, in the hands of monopolistic multinationals, and their use as corporate weapons to stifle innovation, given that intellectual property is by its very nature an exclusionary club good (Schwartz, Citation2017).

The previously distinct institutional frameworks of trade and investment have also been linked under the Trade-Related Investment Measures provision, providing the basis for the use of multilateral trade sanctions for perceived abrogation of investment contracts. The increasing integration of investor protection in trade agreements as well as bilateral investment treaties has added to the coercive toolkit and strengthened the bargaining power of multinationals vis-à-vis host countries, especially given the multiple possible venues for dispute resolution, including investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms (Morrissey & Rai, Citation1995; St John, Citation2018).

Subordinate trade and investment agreements have additionally strengthened the interests of multinationals in relation to developing countries. Since the 1990s, regional agreements have proliferated, particularly among countries with dissimilar levels of development, thus increasing the power of dominant countries over less wealthy ones in more intimate institutional settings. These agreements have largely expanded the trade in components mostly within the largest multinationals and their subsidiaries across multiple sites of production (Baccini, Pinto, & Weymouth, Citation2017). Broad institutional continuities between the WTO and regional agreements allow for de facto complementarity, with even stricter provisions for intellectual property and investor protection. Furthermore, in cases of significant power symmetries, the capacities of dominant countries to threaten market exclusion to enforce intellectual property protection or investment contracts are even greater, even as the rules themselves are broadly the same (Mansfield & Reinhardt, Citation2003).

Wade (Citation2003) powerfully argued that the creation of the WTO constrains ‘the development space’ for poorer countries; many of the provisions of the WTO membership, particularly in services, investment and intellectual property, foreclose the possibilities of pursuing the independent industrial policies of East Asian developmental states. This intervention should have refocussed scholarship towards the potentially deleterious impact of the new institutionalisation of trade and investment for developing countries. But this has not occurred, partly because the early 2000s represented a time of global growth and commodities boom that did not suggest the pessimism of the next decade, and partly because for most scholars of the comparative politics of developing countries, domestic strengths and deficiencies – particularly in comparison to East Asian cases – remain much more naturally salient than more distant international influences for explaining growth.

3. Global value chains

The current shape of international institutions detailed above has also given multinationals significant autonomy to structure their investments, licencing and production arrangements in developing countries, building disaggregated but institutionalised networks of outsourcing across borders in order to maximise returns on investment. In this context, export-oriented firms and industries in developing countries find themselves assigned to particular niches in the production of components and end-use goods by investment and purchasing contracts, with little scope for strategic negotiation but with profound implications for national growth trajectories. Middle-income countries can find themselves stagnating relative to neighbours and competitors based on the collective decisions in corporate headquarters of multinationals.

Global value chains (GVCs) – defined as global inter-firm networks with constituent actors working together in the full range of activities that must be performed, from conception to fabrication to end use, for a product to reach consumers (Gereffi & Fernandez-Stark, Citation2011, p. 4) – represent a second set of international institutions that have significant consequences for middle-income countries. Before the current era of globalisation and the formulation of GVCs, production of manufactured goods largely occurred within one firm in one country, either for domestic or export markets, or within a multinational establishing a discrete subsidiary in a country to manufacture and market its goods there, often as a joint venture with local firms, with the most successful of these enterprises eventually entering export markets themselves (see Kurth, Citation1979). This gave national governments significant influence over the terms of foreign direct investment, or what P. Evans (Citation1979) has called ‘dependent development’.

The beginnings of the mass internationalisation of production were driven by changes in consumer tastes and rising labour costs in western countries (Piore & Sabel, Citation1984). After an initial burst of outsourcing, the disaggregation of production and marketing across national borders has been increasingly governed by vertically integrated, hierarchically organised GVCs and controlled by multinationals, as buyers or as final producers (see Gereffi, Citation2018). Changes in communications and transportation technology and the revolution in post-Fordist manufacturing techniques, as well as the institutionalisation of trade and investment discussed above, have enabled multinationals to achieve much greater disaggregation of production across borders, even while ensuring that most of the benefits still accrue to their shareholders as returns to branding and intellectual property. The manufacturing of one good, like a car or a computer, involves the assembly of components by firms in several different countries, working together in ‘just-in-time’ production under the direction of a lead multinational firm, which would capture a large proportion of the value of the end-product.

Research on GVCs has focussed on different forms of interfirm networks, their internal organisation, mechanisms of coordination and possibilities of upgrading among nodes. As a result, this research engages awkwardly with studies of national development – focussing instead on sectoral dynamics. Certainly, not all GVCs are equally disadvantageous: some types of GVC architecture, especially the ‘relational’ form with high levels of interdependence between buyers and sellers, have lower power imbalances and a higher capacity to facilitate upgrading for subordinate firms (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, Citation2005). But this form is less common with GVCs led by oligopolistic multinationals, particularly in more sophisticated product segments with high levels of intellectual property and a need for standardisation, such as electronics, machine tools and pharmaceuticals, which are usually the focus of development for many middle-income countries seeking to escape the middle-income category.

Multinationals, either alone or as oligopolists, are the sole authors of these high-technology GVCs. They naturally use them to maximise their advantages in limiting costs and thus maximising returns, because they own and thus naturally restrict intellectual property and brands that command product markets in developed countries, protected by trade and investment institutions. Gereffi (Citation2014) has suggested that the proliferation of rents, like copyrights and brand names, among those GVCs may explain inequitable outcomes within them (see also Kaplinsky, Citation2000). Multinationals governing GVCs themselves drive increasingly large amounts of international trade and investment, particularly in higher value-added segments; increasingly, countries ‘trade’ in intermediate components of final goods within multinationals and GVCs, in sectors as diverse as automobiles, electronics and pharmaceuticals, and much foreign investment aims at managing the export bases of components within such networks. Thus, international economic integration and non-commodity trade has increasingly meant integration into GVCs. The strategic decisions of lead firms fashion the nature and outcomes of international integration for middle-income countries, at least in the manufacturing of sophisticated products, and thus powerfully influence the possibilities of middle-income escape.

Multinationals balance multiple goals in arranging what gets produced where, however: they favour institutional capacity, certainly, but also access to valued potential markets, proximity or accessibility to other nodes, legacies of prior contacts and even the strategic interests of home countries. For this reason, efforts at augmenting domestic institutional capacity is unlikely to be sufficient for countries to attract multinational orders or investment, engage with multinationals in executing upgrading and achieve escape trajectories. Moreover, once a multinational has decided to engage with, invest in or source from firms in one country, that opportunity is less available to others. This means that the institutional strategies of multinationals have a powerful influence on the capacities of any one country to achieve middle-income escape.

4. International institutions and upgrading

A central difficulty in integrating domestic and global perspectives on industrial development and escape from the middle-income trap is that there is ambiguity over a key mechanism: that of upgrading, defined as ‘the production of goods and services with increasing value added, domestic linkages, and sustained productivity growth’ (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016, p. 609n). Scholars agree that for developing countries to become fully industrialised, they need to upgrade their extant institutions, particularly from those that emphasised raw capital accumulation to those that could support innovation. But what are the real causes of upgrading? Does it have roots in the international or domestic context?

Upgrading in the context of GVCs stands at the heart of mechanisms that link persistently weak (un-upgraded) domestic institutions and external pressures, particularly in the form of multinationals anchoring GVCs. Multinationals themselves tend to conduct their research and development activities in-house or with trusted collaborators, in their home countries (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016, pp. 627–629). Furthermore, as ‘deficient’ actors in collective action, multinationals are absent from and generally uninterested in supporting the formation of domestic coalitions in support of upgrading (see Hirschman, Citation1968). They also use international institutions, particularly in relation to intellectual property, to restrict unintentional the transfer of technology that might provide national firms with greater autonomy.

Multinationals thus place strict controls on the highest value-added activities, with a high IP content, either situating them in-house in home countries or under strict licence in few favoured sites. This severely limits the effective demand for upgraded domestic institutions; multinationals prefer to shift production in domestic countries because of lower costs, not because of emerging capacities for executing higher value-added activities. Because of this strategic orientation on the part of multinationals, the ‘if you build it, they will come’ logic of upgrading domestic institutions on the expectation of interest and investment – such as providing ‘overall sectoral coordinating institutes and public-private consultative councils, … judicial offices for effective contract enforcement and patent protection, … agencies specializing in areas such as innovation financing, testing and standards, [research and development] promotion, and vocational training’ (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016, p. 621) – is unlikely to succeed without close and continuous ex ante engagement with multinationals in the context of GVCs. After all, standards are set by international buyers and lead firms; it is impossible to proceed with trying to meet them through augmenting domestic capacities absent their involvement.

Successful upgrading therefore is a product of cooperative engagement among government agencies, domestic firms and multinationals, in essence a triple alliance (P. Evans, Citation1979) but one in which multinationals rather than states have determinative power. Such engagement is almost mandatory if any country wants to access the wealth of global markets through production of higher value-added products within GVCs. Even if developing countries upgraded their institutions and achieve the potential to produce higher value-added goods, there is not guarantee that they would be able to enter GVCs at higher levels, because entry and positionality is ultimately controlled by multinationals. Such activities are not sufficient for attracting their interest and attention, particularly if that overrides their global investment and sourcing strategies.

Even in the best case, it is also not clear whether GVCs, if they enable upgrading within a particular sectoral cluster, can facilitate economy-wide development. Pahl and Timmer (Citation2020) have found that GVC participation has led to sector-specific productivity growth but not employment generation for developing countries. This can lead to a division in developing economies between upgraded enclaves integrated into GVCs and a remainder of low-skill, labour-intensive domestic small and medium enterprises, one that might not be conducive to economy-wide upgrading, suggesting the preclusion of national growth through compressed development (Whittaker, Zhu, Sturgeon, Tsai, & Okita, Citation2010; see also Cardoso & Faletto, Citation1979; Rodrik, Citation2018). This highlights the harsh dynamics of power asymmetry within GVCs, which in turn links relationships between lead and subordinate firms to asymmetries between the industrialised and developing countries in which they are located (see Dallas, Ponte, & Sturgeon, Citation2019).

Furthermore, in GVCs acknowledged as ‘propulsive sectors’ (Hirschman, Citation1958) with significant forward linkages and spillovers, like electronics, there are additionally features of interfirm governance that present particular difficulties for upgrading and its translation to development. Sturgeon and Kawakami (Citation2011), studying the electronics hardware GVC, emphasise the high proportion of the value captured by lead firms even when subcontractors secure contracts, as firms compete with one another to provide relatively low-value-added mass manufacturing, as opposed to design. While domestic institutional features and certainly skills-upgrading are necessary for any nationally specific firm cluster to receive contracts in the production of intermediary components, there is little opportunity to capture the much greater returns from research, design and branding that are held by multinationals. Dedrick, Kraemer, and Linden (Citation2010) calculated that only one percent of the retail value of an Apple product returned to its Chinese subcontractor. Furthermore, much of the subcontracting has been directed towards geographically adjacent territories, like Taiwanese firms establishing production in mainland China or US multinationals locating low-cost, low-value manufacturing in northern Mexico (Sturgeon & Kawakami, 2011, pp. 129–132, 133–136). As a result, electronics GVC integration has led to dispersion only to a small handful of developing countries, suggesting that augmenting domestic capacity is hardly sufficient in terms of penetrating the most highly sought-after GVCs. Meanwhile, many of the studies of relational upgrading in developing countries have focussed on primary commodities and agriculture, which are unlikely to represent key strategies for middle-income category escape (for example, Grabs & Ponte, Citation2019; Pasquali, Krishnan, & Alford, Citation2021).

The mechanisms outlined here represent a key linkage between external and domestic variables in understanding the political economy of the middle-income trap. International institutions wield structural power to determine the effective demand for strong domestic institutions in the context of developing countries seeking to escape the middle-income trap through export orientation and international investment. This suggests concrete ways in which international institutions not only restrict opportunity but determine domestic ‘upgrading’ institutions.

Contemporary structures of international production undermine the ability of national governments to play a determinative role in upgrading domestic institutions and deploying them towards higher value-added production. In earlier eras, there was more active cooperation between developing and industrialised countries, as well as lead and subordinate firms. In South Korea, for example, normalisation of diplomatic relations with Japan in 1965 meant imports of intermediate goods and strategic foreign investment that focussed on high-technology production, such as in joint ventures between Mitsubishi and Hyundai in the automotive engine sector, and Sumitomo with Samsung in televisions and in the steel industry – which characterised the ‘flying geese’ model (Akamatsu, Citation1962; Amsden, Citation1989, pp. 175–176, 306–316). Even the state-led regime of R&D in Taiwan gave way to greater public-private cooperation and indeed the active participation of technology firms led by overseas Chinese entrepreneurs in innovation in the 1990s (Hsu & Chiang, Citation2001). In the contemporary global economy, however, such strategic interaction among states, multinationals and national firms has given way to greater national disaggregation and cross-border integration. This makes it more difficult for developing countries to use domestic upgrading institutions to facilitate higher value-added production and escape the middle-income trap, absent engagement with multinationals who have little obvious interest in supporting upgrading for its own sake. In the next section, I will explore these dynamics among sets of middle-income countries.

5. International institutions and outcomes among middle-income countries

There are therefore causal linkages and mechanisms between the international institutions of trade and investment, GVCs, and factors that could determine who might succeed and who might fail to escape from it. What do these dynamics look like in practice for states across the middle-income universe? A useful way of understanding the individual constraints facing developing countries to separate present and past middle-income countries into categories of graduates, contenders and aspirants ().

Table 1. Recent graduates, contenders, and aspirants.

In what follows, I will discuss some of the international institutional dynamics that constrain (or occasionally enable) some of these countries in their trajectories of escape.

5.1. Graduates

I define graduates are those countries that were plausibly in the middle-income country category in 1990, with gross national incomes per capita (current dollars, by the Atlas method) of less than $7690, and are now high-income countries, with incomes of over $12,536 in 2019. These include rentier Gulf states like Oman, wealthier Latin American countries like Chile and Uruguay, eastern and central European countries like the Czech Republic and Poland, and East Asian developmental states like South Korea.Footnote1 Slightly older graduates, not included in the analysis, are countries in southern Europe, Ireland and Israel.

As mentioned above, countries that graduated from middle-income status through state-driven and export-oriented industrialisation, such as the classic developmental states of East Asia faced salutary – and highly regionally and temporally specific – external environments that are unlikely to be replicated (Feenstra & Hamilton, Citation2006). This suggests that the successes of Northeast Asian cases might represent exceptions rather than models (Bernard & Ravenhill Citation1995; Cumings, Citation1984). Other middle-income graduates faced supportive external environments in other ways. Graduates from central and eastern Europe benefitted from the project of European integration after the end of the Cold War, becoming low-cost producers and recipients of significant FDI from western Europe; EU membership and the related opportunities for upgrading were determined as much by geopolitical considerations as innate potential.

Other middle-income graduates achieved their escape not from industrialisation. Gulf states enjoyed rentier returns from oil and gas production. Latin American cases left middle-income status through a slow recovery from decades of austerity and diversification into services (Cypher, Citation2018); Chile’s manufacturing value-added as a proportion of GDP fell from a high of 29 per cent in 1974 to 19 per cent in 1990. In these cases, domestic institutions were important, for managing the resource curse or the political conflict that often attends deindustrialisation, but not for attracting multinational investment and integration into GVCs.

5.2. Contenders

Contenders are countries with plausible prospects of achieving high-income status – those with national incomes at least two-thirds that of the $12,536 threshold of high-income status in 2019. This is a highly heterogenous group of countries, representing less than 10 per cent of the countries in the middle-income category. It also includes Russia, which has experienced deindustrialisation, a reorientation towards rentier-ism and exclusion from the international economy as a result of militarism. Contenders in Latin America include Argentina, a wealthier producer of primary commodities whose fortunes fluctuate with international prices, and Costa Rica, where services, especially in tourism and banking, constitute three-quarters of GDP. Brazil, as a South American economy with sophisticated industries like aerospace and long-term relations with multinationals as an export platform, represents an exception.

Several countries focussing on industrial development as a means of escaping middle-income status are nonetheless dependent on proximity and linkages to much more powerful countries, and thus choices of multinationals to invest, locate and potential engagement with upgrading. A large portion of Mexico’s industrial development is concentrated in maquiladoras along the US border, reliant on NAFTA-formulated supply chains unavailable to any other country; much of the rest of the Mexican economy involves rent-implicated activity (Bergin, Feenstra, & Hanson, Citation2009). Turkey benefits from proximity and institutionalised linkages to the European Union but also lower production costs relative to EU members, and suffers from significant domestic institutional weakness and populist policies. Romania and Bulgaria, as more recent EU members, also benefits greater regulatory certainty as well as lower costs. Such geographic advantages have led to institutional benefits and the potential for engagement over upgrading that are unavailable to most other countries.

Malaysia is a popular destination for outsourcing and investment, representing a case of upgrading institutions that are particularly successful in the globally integrated electronics industry (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016, pp. 632–633; Rasiah, Citation2010). In a more recent assessment, Raj-Reichert (Citation2020) argues that Malaysia’s deep integration into the electronics GVC and efforts at augmenting institutions has not actually yielded more valuable production niches, despite the government’s emphasis on skills, because reliance on FDI has led foreign contract manufacturers to maintain low value-added production, trapping the country in labour-intensive manufacturing. Given Malaysia’s relative promise as a contender and the electronics sector as a prototypical propulsive industry, the influence of multinationals and GVCs is worrying. Moreover, global production linkages have also encouraged enclave production, with limited spillovers. Malaysia’s electronics industry is concentrated around Kuala Lumpur and in Penang, a state with an ethnic Chinese minority and a regionally specific pro-growth coalition (Hutchinson, Citation2008). A World Bank assessment on Malaysia’s escape from the middle-income trap focussed exclusively on Penang, while an IMF analysis was not optimistic and noted Malaysia’s lag in developing dynamic local firms (Cherif & Hasanov, Citation2015; Yusuf & Nabeshima, Citation2009).

Of course, the most salient and powerful contender in the category is China. It has singular advantages; its agrarian transformation and industrialisation occurred in relative autarky, its governing structures are, while repressive, at least theoretically able to formulate and implement long-term strategies. Gereffi (Citation2008) compared China’s development and GVC integration favourably with Mexico’s. The reform of domestic institutions through arbitrage and bricolage, from a weak base, suggests some dynamism even in periods before international integration (Ang, Citation2016). China’s integration with global production and investment reflects (sectorally specific) institutional transformations and strategies of relative state control in the service of extracting value from integration while maintaining autonomy, thus suggesting close engagement between international and domestic actors over upgrading (Hsueh, Citation2011). China certainly seems to represent an exemplar of success in global production through the upgrading of institutions.

Yet this engagement might be sui generis to the case. Fuller (Citation2016) argues that its dynamism lies not with domestic state-owned firms nor with western multinationals but with firms owned by the Chinese diaspora, particularly those based in Taiwan, thus acting as a bridge between international and domestic institutions that can facilitate upgrading. Moreover, multinationals have felt the necessity of engaging with China, given its invaluable internal market and low-cost productive capacity. The Chinese state and affiliated companies have been subsequently requiring technology transfer as part of continuing ‘obsolescing bargains’ with multinationals trying to maintain access to the Chinese market (Lei, Citation2007). This has been more recently supplemented by massive state investments in surveillance and artificial intelligence technologies, as well as the naturally autarkic military-industrial complex.

5.3. Aspirants

Aspirant economies, representing the rest of the countries in the middle-income category, have hopes and might even have emerging strategies of escape, but are not in serious contention at this point. They also have yet to overcome significant domestic institutional disadvantages. Doner and Schneider (Citation2016, p. 663) highlight the challenges facing Thailand, relative to its neighbour Malaysia, in constructing an upgrading coalition. Doner (Citation2009) argues that Thailand’s early impressive efforts in structural change, from low- to middle-income status, have been challenged at upgrading thresholds by veto players and continued patronage demands. Across the world, we see similar evidence of struggles in upgrading, but also possibilities for it, even if in enclave form.

Yet for aspirants, overcoming veto players and forging upgrading coalitions represent only half the battle. Multinationals often make decisions on investment and purchasing and thus engagement on upgrading based on factors other than institutional quality. South Asia is a case in point. India is prominent among aspirants, even though India’s GNI per capita was 16 per cent that of the high-income threshold in 2019, thus solidly in the lower middle-income category. Even though India attracts a great deal of attention from foreign investors and buyers, the quality of its domestic institutions is not exceptional compared to others in the region, particularly Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Excepting measures of democratic consolidation, even Pakistan has comparable measures of domestic institutional quality (Naseemullah, Citation2019). For all their supposed interest, however, multinationals are not engaging with Indian firms or the state in the collaborative project of upgrading. The most significant attempts in opening India to greater foreign direct investment have been in retail and financial services rather than manufacturing. Furthermore, India’s relative successes in integrating into higher value-added niches in certain sectors, particularly pharmaceuticals and information technology, are legacies of industrial upgrading during the period of high statism, which are – as Wade (Citation2003) argues – now fundamentally inconsistent with the rules of international institutions (Naseemullah, Citation2017). Firms in these areas now undertake software services and contract manufacturing in middling niches in the respective global value chains, without much scope for higher value-added activity.

International integration that focusses not on industrial upgrading but rather primary commodities and non-traded services characterises many of the other countries in the aspirant category. South Africa is a case in point; it has experienced significant deindustrialisation, with manufacturing value-added going from more than a fifth of GDP between the 1960s and the 1990s to 12 per cent in the last decade. This is a in part consequence of neo-liberal reform; the ANC government’s orientation to the needs of the rentier-centred business community, international policy consensus and attracting international investors (Handley, Citation2005). This yielded engagement between international and domestic actors that foreclosed upgrading.

All of this suggests significant inequality among current members and recent alumni of the middle-income category. First, the paths taken by the classical developmental state cases, which involved active engagement between domestic and international institutions over upgrading, are essentially closed for later developers. The remarkable mobilisation of state strength in the context of an enabling regional environment that enabled economic transformation in East Asia contravenes the rules of trade and investment and has become unviable today. Thus the emphasis on domestic institutional strength and upgrading as necessary and sufficient for development is not a mantra that is now straightforwardly applicable to developing countries. In the current institutional context, multinationals make strategic decisions for investment based on market size and attractiveness, proximity or previous linkages in ways that limit the capacity for upgrading in most developing countries. More broadly, GVCs have made development more zero-sum, because their orders for higher value-added components or manufactured goods are finite, and firms across different countries must compete for them while attempting to engage multinationals in the complex process of upgrading. This has benefitted lead firms in achieving lower costs, but it means that while middle-income escape through international integration is more difficult. The politics behind the construction of international institutions have, at least in part, crafted this outcome.

6. Conclusion

I have argued that the nature of the middle-income trap – the low chances of any one country to graduate from the middle-income category – can be seen as the result of international institutions. The specific nature and consequences of international institutional structures in the post-Cold War era have played a role in making graduation difficult, relative to the opportunities faced by earlier developers, by heightening competition and suppressing the demand for upgrading. Yet research on the comparative politics of national development has continued to focus on the capacities of the state and domestic institutions to manage globalisation, generally framing international institutions as fixed parameters, while the dominant paradigm in international political economy has framed international institutions as axiomatically beneficial. This elides important dynamics and processes of power among countries and firms that constrain upgrading and middle-income escape.

Current international structures of production, and associated institutions, may be facing significant pressures to change. As the climate crisis becomes more acute, the sustainability of such disaggregated production is likely to be questioned given the carbon expenditure and broader environmental impact associated with transporting components thousands of miles to achieve slight reductions in production costs. The coronavirus crisis has highlighted the dangers of reliance on long supply chains. With more critical attention to the ways that international institutions may or may not be enabling the growth of middle-income countries, we might discover some more sustainable and less zero-sum avenues for national development.

Acknowledgements

For their comments, advice and criticisms, I would like to thank Amit Ahuja, Caroline Arnold, Catherine Boone, Jennifer Brass, Jonathan Chow, David Collier, Peter Kingstone, James Kurth, Jody LaPorte, Darius Ornston, Natalya Naqvi, Jessica Rich, Herman Schwartz, Paul Segal, Pon Souvannaseng, Paul Staniland, Andrew Sumner, two anonymous reviewers and the editors of JDS. Earlier versions of this paper were presented in seminars at King’s College London, Oxford University, and at the American Political Science Association and the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics annual meetings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Taiwan’s GNI per capita is not calculated by the World Bank, but its GDP per capita at 1990 was $8216, thus roughly at the high-income threshold.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail. London: Profile.

- Aggarwal, V. (1985). Liberal protectionism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Akamatsu, K. (1962). A historical pattern of economic growth in developing countries. The Developing Economies, 1, 3–25.

- Amsden, A. H. (1989). Asia’s next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Amsden, A. (2003). Goodbye dependency theory, hello dependency theory. Studies in Comparative International Development, 38(1), 32–38. doi:10.1007/BF02686320

- Ang, Y. Y. (2016). How China escaped the poverty trap. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Baccini, L., Pinto, P., & Weymouth, S. (2017). The distributional consequences of preferential trade liberalization. International Organization, 71(2), 373–395. doi:10.1017/S002081831700011X

- Baldwin, R. (2007). Political economy of the disappointing Doha round of trade negotiations. Pacific Economic Review, 12(3), 253–266. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0106.2007.00358.x

- Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in international politics. International Organization, 59(01), 39–75. doi:10.1017/S0020818305050010

- Barton, J., Goldstein, J., Josling, T., & Steinberg, R. (2006). The evolution of the trade regime. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bergin, P., Feenstra, R., & Hanson, G. (2009). Offshoring and volatility. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1664–1671. doi:10.1257/aer.99.4.1664

- Bernard, M., & Ravenhill, J. (1995). Beyond product cycles and flying geese. World Politics, 47(2), 171–209. doi:10.1017/S0043887100016075

- Büthe, T., & Milner, H. (2008). The politics of foreign direct investment into developing countries. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 741–762. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00340.x

- Cardoso, F., & Faletto, E. (1979). Dependency and development in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chang, H.-J. (2002). Kicking away the ladder. London: Anthem.

- Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2015). The leap of the tiger: How Malaysia can escape the middle-income trap. IMF Working Papers, 15(131), 1. doi:10.5089/9781513556017.001

- Cumings, B. (1984). The origins and development of the Northeast Asian political economy. International Organization, 38(1), 1–40. doi:10.1017/S0020818300004264

- Cypher, J. (2018). Interpreting contemporary Latin America through the hypotheses of institutional political economy. Journal of Economic Issues, 52(4), 947–986. doi:10.1080/00213624.2018.1527580

- Dallas, M., Ponte, S., & Sturgeon, T. (2019). Power in global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 26(4), 666–694. doi:10.1080/09692290.2019.1608284

- Dedrick, J., Kraemer, K. L., & Linden, G. (2010). Who profits from innovation in global value chains? Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(1), 81–116. doi:10.1093/icc/dtp032

- Doner, R. (2009). The politics of uneven development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doner, R., & Schneider, B. R. (2016). The middle-income trap. World Politics, 68(4), 608–644. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000095

- Drahos, P. (1995). Global property rights in information. Prometheus, 13(1), 6–19. doi:10.1080/08109029508629187

- Drezner, D. (2008). All politics is global. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Drezner, D. (2019, July 30). Elizabeth Warren’s trade plan is bad politics and worse policy. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/30/elizabeth-warrens-trade-plan-is-bad-politics-worse-policy/

- Eichengreen, B., Park, D., & Shin, K. (2013). Growth slowdowns redux (NBER Working Paper 18673). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Evans, A. (2021). The politics of pro-worker reforms. Socio-Economic Review, 18(4), 1089–1111. doi:10.1093/soceco/mwy042

- Evans, P. (1979). Dependent development. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2015). The new politics of interdependence. Comparative Political Studies, 48(4), 497–526. doi:10.1177/0010414014542330

- Feenstra, R., & Hamilton, G. (2006). Emergent economies, divergent paths. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frieden, J., & Rogowski, R. (1996). The impact of the international economy on national policies. In R. Keoane & H. Milner (Eds.), Internationalisation and donestic politics (pp. 285–300) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fuller, D. (2016). Paper tigers, hidden Dragons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, K. (2007). Understanding developing country resistance to the Doha round. Review of International Political Economy, 15(1), 62–85. doi:10.1080/09692290701751308

- Gereffi, G. (2008). Development models and industrial upgrading in China and Mexico. European Sociological Review, 25(1), 37–51. doi:10.1093/esr/jcn034

- Gereffi, G. (2014). Global value chains in a post-Washington consensus world. Review of International Political Economy, 21(1), 9–37. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.756414

- Gereffi, G. (2018). Global value chains and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gereffi, G., & Fernandez-Stark, K. (2011). Global value chain analysis: A primer. Durham, NC: Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitiveness.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805

- Gill, I., & Kharas, H. (2007). An East Asian renaissance. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Gill, I., & Kharas, H. (2017). The middle-income trap turns ten (World Bank Working Paper 7403). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Gowa, J., & Kim, S. Y. (2005). An exclusive country club: The effects of the GATT on trade, 1950–94. World Politics, 57(3), 453–478.

- Grabs, J., & Ponte, S. (2019). The evolution of power in the global coffee value chain and production network. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(4), 803–828. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbz008

- Hafner-Burton, E. (2009). Forced to be good. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Haggard, S. (2018). Developmental states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haggard, S., & Simmons, B. (1987). Theories of international regimes. International Organization, 41(3), 491–517. doi:10.1017/S0020818300027569

- Handley, A. (2005). Business, government and economic policymaking in the new South Africa, 1990–2000. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 43(2), 211–239. doi:10.1017/S0022278X05000819

- Hirschman, A. (1958). The strategy of economic development. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Hirschman, A. (1968). The political economy of import-substituting industrialization in Latin America. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82(1), 1–32. doi:10.2307/1882243

- Holmes, P., & Jonas, O. (1984). Trade liberalization in structural adjustment lending (World Bank Discussion Paper DRD107). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Hsu, C.-W., & Chiang, H.-C. (2001). The government strategy for the upgrading of industrial technology in Taiwan. Technovation, 21(2), 123–132. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(00)00029-8

- Hsueh, R. (2011). China’s regulatory state. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hutchinson, F. (2008). Developmental’ states and economic growth at the sub-national level. Southeast Asian Affairs, 2008(1), 223–244. doi:10.1355/SEAA08M

- Ikenberry, J. (2001). After victory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Iversen, T., & Soskice, D. (2019). Democracy and prosperity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kang, N., & Paus, E. (2020). The political economy of the middle income trap. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(4), 651–656. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1595601

- Kaplinsky, R. (2000). Globalisation and unequalisation. Journal of Development Studies, 37(2), 117–146. doi:10.1080/713600071

- Keohane, R. (1984). After hegemony. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Krasner, S. (1982). Structural causes and regime consequences. International Organization, 36(2), 185–205. doi:10.1017/S0020818300018920

- Krasner, S. (1985). Structural conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kurth, J. (1979). The political consequences of the product cycle. International Organization, 33(1), 1–34. doi:10.1017/S0020818300000643

- Lei, D. (2007). Outsourcing and China’s rising economic power. Orbis, 51(1), 21–39. doi:10.1016/j.orbis.2006.10.003

- Mansfield, E., & Reinhardt, E. (2003). Multilateral determinants of regionalism. International Organization, 57(4), 829–862. doi:10.1017/S0020818303574069

- Matfess, H. (2019, August 1). The progressive case for free trade. Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/8/1/20750506/elizabeth-warren-trade-policy-bernie-sanders-tpp-2020-democrats-progressives

- Milner, H. (1998). Rationalizing politics. International Organization, 52(4), 759–786. doi:10.1162/002081898550743

- Milner, H., & Kubota, K. (2005). Why the move to free trade? International Organization, 59(01), 107–143. doi:10.1017/S002081830505006X

- Morrissey, O., & Rai, Y. (1995). The GATT agreement on trade-related investment measures. The Journal of Development Studies, 31(5), 702–724. doi:10.1080/00220389508422386

- Naseemullah, A. (2017). Development after statism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Naseemullah, A. (2019). Violence, rents and investment. Comparative Politics, 51(4), 581–601. doi:10.5129/001041519X15647434970063

- North, D., Wallis, J., & Weingast, B. (2008). Violence and social orders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostry, S. (2003). The Uruguay round north-south grand Bargain. In D. Kennedy & J. Southwick (Eds.), The political economy of international trade law (pp. 285–300). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pahl, S., & Timmer, M. (2020). Do global value chains enhance economic upgrading? The Journal of Development Studies, 56(9), 1683–1705. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1702159

- Pasquali, G., Krishnan, A., & Alford, M. (2021). Multichain strategies and economic upgrading in global value chains. World Development, 146, 105598. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105598

- Paus, E. (2020). Innovation strategies matter. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(4), 657–679. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1595600

- Paus, E. (2012). Confronting the middle-income trap. Studies in Comparative International Development, 47(2), 115–138. doi:10.1007/s12116-012-9110-y

- Piore, M., & Sabel, C. (1984). The second industrial divide. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Raj-Reichert, G. (2020). Global value chains, contract manufacturers, and the middle-income trap: The electronics industry in Malaysia. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(4), 698–716. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1595599

- Rasiah, R. (2010). Are electronics firms in Malaysia catching up in the technology ladder? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 15(3), 301–319. doi:10.1080/13547860.2010.494910

- Rodrik, D. (1997). Has globalization gone too far? Washington, DC: Piie.

- Rodrik, D. (2018). New technologies, global value chains, and developing economies (NBER Working Paper 25164).

- Ruggie, J. G. (1982). International regimes, transactions, and change: embedded liberalism in the postwar economic order. International organization, 36(2), 379–415.

- Schwartz, H. (2017). Club goods, intellectual property rights, and profitability in the information economy. Business and Politics, 19(2), 191–214. doi:10.1017/bap.2016.11

- Singh, J. P. (2017). Sweet talk. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Steinberg, R. (2002). In the shadow of law or power? International Organization, 56(2), 339–374. doi:10.1162/002081802320005504

- St John, T. (2018). The rise of investor-state arbitration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stone, R. (2011). Controlling institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sturgeon, T. J., & Kawakami, M. (2011). Global value chains in the electronics industry: characteristics, crisis, and upgrading opportunities for firms from developing countries. International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development, 4(1-3), 120–147.

- Wade, R. (2003). What strategies are viable for developing countries today? Review of International Political Economy, 10(4), 621–644. doi:10.1080/09692290310001601902

- Whittaker, H., Zhu, T., Sturgeon, T., Tsai, M.-H., & Okita, T. (2010). Compressed development. Studies in Comparative International Development, 45(4), 439–467. doi:10.1007/s12116-010-9074-8

- Yusuf, S., & Nabeshima, K. (2009). Can Malaysia escape the middle-income trap? A strategy for Penang (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4971). Washington, DC: World Bank.