?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Does a legal reform with patriarchal interpretations of the religious law codes affect the wellbeing of the children? In this study, we show that reforming the legal system by adopting a religious law, with high enforcement in some Nigerian states, affects a woman's bargaining power and utility outside marriage, which could adversely affect a child's wellbeing. We find empirical support for this framework by using a difference-in-differences design that exploits variation in the women's religion, the state of residence, and the period of reform enforcement in Nigeria. The findings of this paper reveal that women exposed to the reforms are likely to report poor health investment and poor health outcomes in their children. The potential pathways through which the reform affects child wellbeing include early marriage entry and a decline in a woman's intra-household bargaining power.

1. Introduction

Lack of women empowerment resulting from gender-related laws inhibiting women’s litigant rights could have implications on children’s wellbeing (Ajefu, Singh, Ali, & Efobi, Citation2022). For example, in the year 2000, some states in Nigeria reformed their legal system to introduce the enforcement of religious law, and one of the consequences of such reform was the reduction of the litigant rights of Muslim women, which included the abolition of the legal protection for women against sexual abuse and other forms of domestic violence. Moreover, women's testimony in matters related to sexual relations was valued lower than their male counterparts under the new legal regime (Bourbeau, Umar, & Bauman, Citation2019). In principle, such reform could change the social norms in gender relations regarding women's utility outside marriage, marital matches, and her bargaining power in society. By implication, these changes could affect the wellbeing of the children of the affected women.

This paper seeks to examine the effect of the introduction of a legal reform that significantly changes women’s litigant rights matters on children’s wellbeing. It broadly speaks to the literature on the effects of changes in gender-related laws in the context of developing countries (Deininger, Goyal, & Nagarajan, Citation2013; Roy, Citation2015). Our focus is motivated for the following reasons: First, reducing women's litigant rights will affect intra-household relations and women's bargaining power within the spousal household. These changes in women's bargaining power could affect decisions over resource allocation toward a child's health and wellbeing (Chari, Heath, Maertens, & Fatima, Citation2017). Second, the reform's consequences of lowering women's utility outside marriage may have led to early marriage or marital relations with less preferred spouses and limitations in women's outside options, which could lead to a shift in women's ability to care for their children. This paper proposes a framework for analyzing the effect of the legal reform along the channels described above, and the analysis of this paper relies on data from the Nigerian Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

The DHS gathered data for periods before the reform enforcement in 1999 and periods after the reform for children (0–5 years) of the sampled women. Each survey includes information about the women in the household and each woman's children. However, the emphasis in this study is on women with children ages 0–5 years. For the outcome variables used in this paper, we define a child's wellbeing as an investment in the child's health, including the location of childbirth, number of antenatal visits, the likelihood of having vaccinations, and the number of breastfeeding months. The other indicator is the child's health outcomes, such as the child's size at birth and the likelihood of the child recording fever, cough, or diarrhea in the past week. Due to data limitation issues, we cannot consider other health outcomes, such as the anthropometric measures.

The key findings of this paper reveal that reforms with a codified conservative religious law that significantly diminishes a woman’s litigant rights have a negative effect on affected women’s investment in the health of their children, as well as a decrease in the number of antenatal visits and the probability of having vaccinations. Moreover, we identify adverse effects of women’s exposure to the reform on the health outcomes of the children of affected women, such as an increase in the likelihood of the child having fever and cough. We identify mechanisms such as a decrease in women’s intra-household bargaining (i.e. the woman is solely or jointly involved in decisions about how to spend her earnings), and the age at marriage entry above 18 years – an indicator of a woman’s utility outside marriage.

These findings are relevant as it shows the second-generation effects of implementing a religious law reform in Nigeria, which remains an inconclusive empirical and policy debate. For example, while Alfano (Citation2017) concludes that a similar reform may have improved a child's education and maternal investment in a child's wellbeing through increased breastfeeding months (Alfano, Citation2017), others find adverse effects on women's fertility decisions and intrahousehold bargaining (Godefroy, Citation2018). With increased fertility, for instance, one would expect adverse consequences on children's wellbeing following the quantity-quality tradeoff theoretical underpinnings (Becker & Lewis, Citation1973; Becker & Tomes, Citation1976). Moreover, adverse effects on the investment in a child's health and the overall health outcomes considered in this study could have a far-reaching effect on later life outcomes such as physical development and cognitive functioning. Stunting and non-health indicators such as education, learning, and other human capital formation outcomes are consequences of the reoccurrence of negative health incidence at the early stages of a child's development (Almond & Currie, Citation2011). Therefore, our findings suggest that reforms that affect women's legal rights constitute essential factors for wellbeing in later life through effects on the immediate child's wellbeing. These findings could be important in supporting policies to enhance women's rights in developing countries. Consequently, empowering women through legal reform changes that improve their legal rights could be essential to achieving long-term sustainable development outcomes.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the context, presents literature on the effect of legal reforms, and discusses the analytical framework underpinning the research analysis. Section 3 presents the data sources, variable definitions, and identification strategy. Section 4 presents the results, while Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Context

2.1. Context of the legal reform in Nigeria

The current Republic of Nigeria, the Fourth Republic, saw the adoption of the constitution that legally recognized 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory and the adoption of the Penal Code that incorporated the British legal system style. At the state level, the Sharia Court of Appeal (SCA) constitutionally decides civil matters, including Islamic personal law on marriage, marriage relations or divorce, and those related to inheritance and child custody for Muslims who choose to be arbitrated under this system. Other criminal matters (such as murder) are litigated in different circular or conventional courts (e.g. customary), and certain corporal punishments, such as amputation, are banned.

In 2000, the governors of some states in Northern NigeriaFootnote1 reformed their legal system, such that the SCA began to litigate criminal cases. This reform re-introduced the use of corporal punishment in sentencing. The re-introduced punishments were sentences for convictions related to theft, murder, and ‘illicit’ sexual relations – including extra-marital and homosexual affairs. The enforcement of this codified conservative religious law became pervasive since the reformFootnote2 for strict compliance by Muslims within the state, while non-Muslims could resort to the secular courts for arbitrations. There is no indication that Muslims residing in the enforcement locations could opt-out from adjudication under this new law. Suggesting that the reform enforcement is far-reaching and overwhelming in the enforcement location, and individuals of the affected religion are subject to the new reform (Godefroy, Citation2018).

There are criticisms of the implementation procedures of this reform, including the rushing of adjudication procedure, lack of qualified judicial personnel, and lack of required training of justice administration personnel, such as Judges, for effective judicial procedures. Further, the reform was criticized for inhibiting women's litigant rights, as women's testimony in matters related to sexual relations were of lower value than their male counterpart once such cases were adjudicated in the Sharia court. Thus, women are exposed to sexual assaults and violence within and outside the marital union because their protection under this legal system was significantly lowered. For example, a woman who reports a rape case in the Sharia court is considered to have confessed to illicit sexual affairs or falsely accused a man. In cases where rape is difficult to prove, the appellant faces the punishment of flogging for indulging in “illicit” sexual behaviour or bearing “false” witness against an accused male (Godefroy, Citation2018). Other evidence suggests that in cases of sexual assault, men were allowed to swear an oath of innocence, while women did not have this opportunity, denoting that the testimony of a man is highly rated than a woman.

In this new regime, women's testimonies are devalued to half a man's, and a woman requires at least two witnesses to prove a man's guilt. Once such guilt cannot be proved, a woman's litigation will either be upturned or completely abandoned (Ibrahim, Citation2012; Weimann, Citation2010). Overall, the reform has a disproportionate adverse application on women compared to men, including the attack on women in public places because of their appearances (such as engaging in outside activities without head coverings) and judges taking sides for male defendants in their legal interpretations while ignoring rules that might favour women on trial (Bourbeau et al., Citation2019).

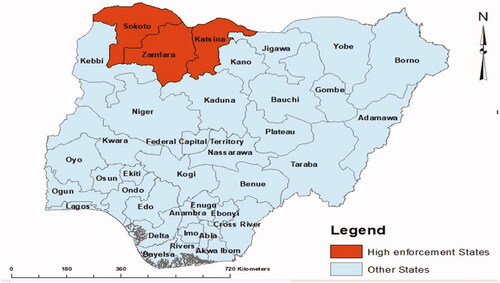

Three states – Sokoto, Zamfara and Katsina – account for 60% of the recorded cases under this reform (Weimann, Citation2010). in the appendix clarifies the location of these states in Nigeria. Therefore, for this study’s identification, these three states will be relevant for identifying a geographic variation in the extent of the reform application. The issue of interest that will be discussed in the subsequent section is the approach for identifying the effect of this reform on the health outcomes of the children of women exposed to the reform.

2.2. Legal reform and women’s rights

This study contributes to the literature on the generational consequences of institutional reforms that affect women's rights. Studies focusing on the socio-economic effects of religious laws have examined effects on women's rights, health, fertility, human capital formation, and economic attitudes (Clingingsmith, Khwaja, & Kremer, Citation2009; Godefroy, Citation2018; Guiso, Sapienza, & Zingales, Citation2003; Meyersson, Citation2014). Specifically, Meyersson (Citation2014) argues that the reign of a religious-political party (a form of institutional change) led to increases in female secular high school education, a reduction in adolescent marriages, an increase in female political participation, and an overall decrease in Islamic political preferences. Other studies consider religious beliefs and economic outcomes (Guiso et al., Citation2003), the adoption of religious law and fertility (Godefroy, Citation2018), and effects on increasing equality and harmony among ethnic groups (including greater acceptance of female education and employment) from religious practices (Clingingsmith et al., Citation2009).

Furthermore, other studies focus on the effect of institutional change on women's outcomes (Miller, Citation2008). The author highlights that reforms of the suffrage rights for American women led to immediate shifts in legislative behaviour and large, sudden increases in local public health spending and a decline in child mortality. Similarly, Kose, Kuka, and Shenhav (Citation2021) show that the political empowerment of women led to large generational consequences in human capital formation, such as higher earnings alongside education gains. Consistent with the focus on (religious and non-religious) institutional change that affects women’s socio-economic outcomes, our study's novelty focuses on how the enforcement of certain religious laws that disadvantages women in a developing country's context impacts the children of affected women.

Our paper also adds to the literature on the development effects of changes in gender-related laws. Deininger et al. (Citation2013) and Roy (Citation2015) considers the effect of gender-related reforms to India's inheritance law – the Hindu Succession Act – on daughters' likelihood to inherit land and other human capital accumulation outcomes. Other studies, such as Godefroy (Citation2018), examined the effects of a legal reforms that restricts women's litigant rights on fertility, showing that such reform increased the probability of additional childbirth and a shift in fertility decisions towards the husband's fertility preference. Moreover, Godefroy (Citation2018) notes that the impact of such reforms is seen through effects on women's fertility decisions, marital outcomes, and labour supply channel. Our paper differs from the existing literature by considering the investment in child health outcomes of women exposed to the religious law reform in Nigeria. Other studies have further linked similar religious laws to control over territory and shaping public institutions according to the law, leading to violent clashes between sympathizers of the law and opposing groups (Harnischfeger, Citation2004).

Glaze (Citation2018) asserts that the issue of protecting women's rights with the implementation of the religious law is not tied to the religious underpinning of the law. Rather, the interpretation of the law is determined by the historical forces that have shaped the country's cultural life. Moreover, studies such as Glaze (Citation2018) focus on women's rights in Sharia Law, while Harnischfeger (Citation2004) considers the origin of the law for territorial control. Our study asserts that implementing such laws by changing women's litigant rights affects the health investment and outcomes of the children of affected women.

2.3. Analytical framework

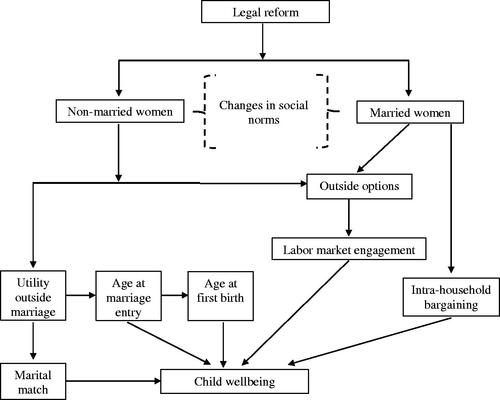

This section presents a simple framework in to guide the discussion of the links between religious reform and child’s wellbeing. In this framework, a nexus is established between the reform and women's investment in child's health outcomes through the changes in social norms that affect a woman's bargaining power, utility outside marriage, and her outside options. Considering the bargaining power channel, the legal regime studied in this paper is reported to inhibit women's rights in society, especially their rights to choose and bargain their sexual relations (Godefroy, Citation2018). This is mostly because of the patriarchal interpretation of the religious law codes (Odok, Citation2020). Outside mobility for women in such a society may be limited because of likely threats when they are outside their homes without a male accompanying them.

Regarding outside marriage utility, the reform enforcement is expected to diminish such utility. Women who enter marriage as a form of protection may see their decisions within the household shifting closer to the husband's/spouse's preferences to retain their status within the spousal household (Godefroy, Citation2018). Such a shift in decision-making power is analogous to lowering women's bargaining power in intra-household matters, which is expected for women to remain in the marital relationship because of the uncertainties or risks they may face outside marriage.

A woman's utility outside marriage can be seen through age at marriage entry and subsequently age at first birth. For example, due to the changes in the social norms, commonality of rapes, and personal attacks outside the home, families may be concerned about their daughters' safety. To protect their daughters, these families could engage in certain practices, including marrying out their daughters earlier (perhaps to less preferred matches), which could imply earlier age at first birth (Baird, McIntosh, & Ozler, Citation2019; Chari et al., Citation2017). More so, families may give their daughters out in marriage to a less preferred spouse to protect their daughters from the realities of this reform since single women are disproportionally and adversely affected by the new law (Godefroy, Citation2018). These actions may have other adverse consequences on premarital endowments and child’s wellbeing.

It is important to acknowledge that there could be interconnections between each channel being considered. However, such connections are not of interest because this study's analysis only considers them to establish possible pathways through which the reform affects a child's wellbeing.

In summary, improving women's rights in society tends to enhance their power within the household (Harari, Citation2019; Heath & Tan, Citation2020; Heggeness, Citation2020). These effects translate to gains for a child's wellbeing through access to resources and better bargaining for resource distribution for child health (Chari et al., Citation2017; Deutsch & Silber, Citation2019; Hahn, Nuzhat, & Yang, Citation2018; Li, Wu, & Zhou, Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2020). Therefore, the wellbeing of the children of women exposed to the reform is affected as the relative bargaining weight of wives declines with the reformFootnote3. This is expected because the ability to engage in economic activities outside the household or seek other outside opportunities to increase household resources for child wellbeing, will decline with adverse changes in a woman’s bargaining power (see the pathway in ).

3. Empirical strategy

3.1. Data and measures

We rely on two rounds of the Demographic Health Survey datasets – 1999 (pre-reform enforcement period) and 2003 (post-reform enforcement period) survey years. The DHS provides information about the health indicators of the child of women with current birth. The DHS also provides information about the bargaining power, age at marriage entry and first birth, and marital match, which are relevant mechanisms depicted in the framework that relate the reform enforcement to a child’s health. We do not consider the labour market channel as one cannot disentangle this channel from the bargaining power channel (Heath & Tan, Citation2020). The DHS data is nationally representative from the 36 states (and the federal capital territory – Abuja) and has a relatively large sample size, allowing us to flexibly account for the effects of the legal reform that may vary by state and religion. However, for the analysis, we only consider married women between ages 15–49 with current birth as of the survey year. This sample construction allows for a more precise identification of women who may be affected by the reform.

The analysis focuses on some outcome variables, as described:

Child Wellbeing: This is the main outcome variable that includes indicators of maternal investment in the health of her child and child health outcomes. (A.) Health investment: we consider four indicators from the DHS data, such as the location of birth for the current delivery of the child, i.e. childbirth at home, which is a binary indicator if the place of child delivery is home and 0 otherwise. Antenatal visits during pregnancy (reported as the number of antenatal visits). Child ever had a vaccination after birth (1 if yes and 0 otherwise), and the number of breastfeeding months for the current child. (B.) Health outcomes: we consider only the temporal health condition of the child as of the survey period. This study could have considered other enduring health outcomes such as anthropometric measures but was not adopted due to data limitations. For example, the data for anthropometric indicators were featured in the 1999 survey but had a lot of missing information. Noting such data limitations, we only considered the size of the child at birth (measured as '1' if the child is small or very small, and 0 if average or large), whether the child had a fever in the last two weeks ('1' if yes and 0 if no), had a cough in the last two weeks ('1' if yes and 0 if no), and recently had diarrhea (1 if yes and 0 if no). It is important to acknowledge the limitations of these indicators. They do not reveal much about the long-term child-health implications of the reform, and some of these indicators may be seasonally influenced and are mostly temporal health conditions. Nonetheless, they are relevant indicators for comparing the average child's health by the effect of the reform on women, particularly in a context of data limitation and where adverse changes in these health indicators could reflect constraints in women's ability to access necessities to prevent such illness, e.g. bed nets, warm clothing, and improved home sanitations or personal hygiene.

Supplementary Outcomes: following the analytical framework in section 2.3, this study considers indicators of intra-household bargaining power, utility outside marriage, and spouse’s quality. From the DHS data, we identify an indicator of intra-household bargaining to include a binary indicator if the woman is solely or jointly involved in the decision to spend earnings from her economic engagement (i.e. solely or jointly decides how to spend respondent’s money). We consider two indicators from the DHS data to measure a woman’s utility outside marriage. That is, a binary variable if the age at marriage entry is 18 years and above (i.e. Marriage entry age above 18yrs) and a binary variable if the age at first birth is 18 years and above (i.e. Age at first birth above 18yrs). Finally, we consider an indicator of the marital match as a binary variable if the sampled woman’s spouse has equal or higher education completion (i.e. Spouse has higher education completion).

Other Covariates: to improve the estimation results, we control for different covariates computed from the DHS such as the birth order of the child, the height of the woman, total children of the woman, the number of other wives in the household, and the partner’s age.

The summary statistics for the different investment indicators in a child’s health, child’s health outcomes, the supplementary outcomes, the covariates and the identification variables are all presented in .

Table 1. Summary statistics of the estimation sample

3.2. Identification strategy

This study exploits variation in the reform enforcement location and the enforcement's timing to estimate the effects of religious law reform on children’s wellbeing. Further, the effects can be identified by estimating the dummy variable capturing exposure to the enforcement, conditioned on location and time-fixed effects. The reform is such that it affects only individuals of a specific religion (i.e. Muslims) who resides in the enforcement states. One threat to the identification is migration, such that individuals or households may change location to minimize the reform’s effect. The robustness check in the subsequent section highlights that this issue may not be of concern for this study.

Accordingly, we consider the variable ‘affected’ to depict Muslim women who reside in the reform enforcement states, while the comparison is non-Muslim women in the reform enforcement states and other women (Muslim or non-Muslim) in the non-reform enforcement states. This variable will be conditioned on the time-fixed effect to identify periods before and after the reform. Specifically, in the nationwide DHS, where all women were surveyed before and after the reform passage, we consider an outcome Y for the child of the woman i of religion r in the period residing in state s. The variation in the timing of the passing of the reform and enforcement period (i.e. Post) is included in the estimation as an additional source of variation. Hence, the time variation is captured as survey years before (0 if 1999) versus after (1 if 2003).

The identification estimation is:

(1)

(1)

The variable of interest is which shows the effect of the reform on women affected by the reform while controlling for other covariates. We are ruling out factors that could differentially impact child’s outcomes apart from the reform enforcement in periods before the passage of the reform. We clarify this assumption using a placebo test, which will be discussed in section 4.2.

Given that this regression considers variation over time and space, it is possible that a child’s wellbeing could vary over time among women of different ages across states. Hence, our preferred analysis considers the specification that controls for the year- and state-fixed effects, to account for those factors that could influence child's health outcomes that are peculiar to the survey year and state of residence. We also account for the fixed effect for the interaction of age of the woman and state (i.e. age × state- fixed effects), which accounts for those factors that may affect child health outcomes that are peculiar to women of a certain age in a certain state of residence, e.g. age grade effect in accessing health infrastructures. The standard error is clustered at the level of the states.

4. Results

4.1. Reform and child wellbeing

We begin by presenting the relationship between the reform enforcement and a woman's investment in the health of her current child. The results in show a similar and consistent decline in such investments across the different model specifications. It suggests a consistent decline in the woman's investment in her child's health in periods after the reform enforcement began. Specifically, column 2 suggests that the reform adversely correlates with the number of antenatal visits by a significant 1.3 times, similar to the model that controls maternal education. For the likelihood of the child receiving any vaccination as of the survey year, the result also shows a negative effect of 17-percentage points decline and 20.1-percentage points decline for the model that accounts for maternal education. However, the significance level varies depending on the adjustment for maternal education. The reform's effects on the likelihood of childbirth at home and the number of breastfeeding months are consistent with our hypotheses of adverse effects. However, the estimates are insignificant at the traditional one or five percent level.

Table 2. Effects of the reform on a woman’s investment in child’s health

The next consideration is the child's health outcome. The results are presented in , with the estimate of some of the coefficients suggesting adverse correlational effects between the reform enforcement and child wellbeing. Specifically, the results in column 2 suggest a significant positive relationship with the likelihood of the child of the affected woman reporting to have had a fever in the past two weeks. This effect is a 38.9-percentage point increase (or 38.5-percentage points when adjusting for maternal education), and it is significant at a one per cent level. Further, the result shows a significant increase of 9.8-percentage points in the likelihood of the affected woman reporting that her child had a cough in the past two weeks.

Table 3. Effects of the reform on child’s health outcomes

Thus far, the results demonstrate that the changes in the litigant rights of women can substantially affect the investment in a child's health, with attendant implications on other indicators of a child's health. Given that these health indicators are early life circumstances and the frequency of their occurrence over the child's development stages could have enduring developmental implications, one can expect that the existence of the reform could have other enduring health or non-health implications for the child of the affected woman. For example, the reoccurrence of negative health incidents at the early stages of life could have other lasting impacts such as stunting, education, learning, and other human capital formation outcomes (Almond & Currie, Citation2011).

4.2. Design validation

To validate our estimates from this study’s design, we conduct three additional checks, including adjusting the specification for potential selective migration from the reform enforcement, excluding women who reside in neighboring states to the reform enforcement states, and performing a placebo test.

Selective migration may arise if the reform enforcement triggers households’ or individuals’ migration from reform enforcement states to other states to reduce the reform’s impact. Such endogenous migration could be a threat to our identification. The evidence from suggests that the likelihood of migrating across locations is not influenced by the reform enforcement, which is congruent with Harnischfeger (Citation2004) and Godefroy (Citation2018). The next consideration is whether the results are consistent when we exclude the sample of women residing in other neighbouring states to the reform enforcement states. Women in these neighboring states may be influenced by the reform enforcement, especially because some of these states adopted the reform but with minimal enforcement as the other high enforcement states. Excluding these women from the sample will imply that by construction, the only women in the high-enforcement states are those that reside in any of the three states (Sokoto, Zamfara, and Katsina), and there are no other women in the control states that may have been directly or indirectly exposed to the reform enforcement. in the appendix shows similar results to earlier Tables, although there were some deviations in the significant values.

Finally, we present a placebo test in space by arbitrarily reassigning the high-enforcement state to other states (apart from Sokoto, Zamfara, and Katsina). We exclude the three high-enforcement states, assign random numbers to the other states, and then select the states with the top three random numbers as the pseudo-high-enforcement states. The variable ‘ Post’ does not change. Hence, the policy variable Affected × Post is the interaction between Muslim women who resides in the pseudo-high-enforcement states and the fixed effect for the year of reform enforcement. The results in show zero effect of reform enforcement for all the earlier significant variables in and . Suggesting a robust estimate when subjected to a placebo test.

4.3. Mechanism

This section evaluates two potential pathways that could explain the changes in a child's wellbeing in response to the reform enforcement. First, given that the reform adversely affects women's litigant rights, such that women's voice in the community may be diminished due to changes in social norms regarding acceptable and non-acceptable behaviours for women, the reform will directly affect women's bargaining power and utility outside marriage. As highlighted in , such changes in the social norms may affect married women's intra-household bargaining as their decisions on issues may shift towards their husbands to remain in the marital relationship due to other outside marriage uncertainties. Such an effect could affect a child's wellbeing, consistent with the bargaining power literature (Chari et al., Citation2017; Deutsch & Silber, Citation2019; Hahn et al., Citation2018; Heath & Tan, Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2020). Arguing that changes in women's bargaining power affect access to resources and decisions about how resources should be channeled towards the wellbeing of children.

In this regard, we assess whether the bargaining power channel is credible by estimating Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) , with outcome variables as indicators of intrahousehold bargaining power. That is the likelihood of a woman solely or jointly deciding how to spend her money, with estimates presented in column 1 of . Column 2, 3, and 4 of includes the estimates of the alternate channel, which is the decline in a woman's utility outside marriage and marriage entry into a non-optimal marital match. These channels are mostly for non-married women, as depicted in . As discussed in section 2.3, this channel is expected as the social norm changes, resulting in the commonality of rapes and personal attacks outside the home. Therefore, concerned families could push their daughters towards earlier marriage entry, perhaps to a less preferred spouse. The consequences of such decisions may be seen in the reform's effect on the age at marriage entry, age at first birth (assuming that first births occur after marriage), and the differences in the spouse's quality.

Table 4. Examining mechanisms

The results in column (1) confirm a negative correlation between the reform enforcement and the likelihood that the sampled women report that they are solely or jointly involved in deciding how to spend the respondent's money. This relationship is a statistically significant 28.2-percentage point decline relative to women not affected by the reform enforcement, suggesting that adverse effect on women's bargaining power could be one channel linking the reform and child wellbeing. Column (2) further shows a significantly lower likelihood of marriage entry age above 18 years for affected women (by 17.7-percentage points) relative to women unaffected by the reform enforcement. The results for age at first birth above 18 years and the indicator of the marital match are not statistically significant, although the signs are consistent with hypotheses in the analytical framework.

5. Conclusion

We show in this paper that reform with a codified conservative religious law, which significantly diminishes a woman’s intrahousehold bargaining and limits her utility outside marriage because of the patriarchal interpretation of the laws, is likely to have adverse effects on a child’s wellbeing. Women exposed to the reform record a decline in the number of antenatal visits, and the child of such women are less likely to report that they have received any vaccination as of the survey year. More so, the children of the affected women are more likely to report having had a fever and cough in the past week before the actual survey period. Although the health outcomes considered in this study are transitory (due to data limitations), an increment in poor child health (no matter the health indicator) may significantly matter for the long-term human capital outcome.

The findings of this paper matter for sustainable development in a region already burdened with health challenges. In 2018, 74 percent of under-five deaths occurred in Africa and South-East Asia, and 76 percent of 1000 live births to mothers in countries in the African region are likely to die before their fifth birthday (World Health Organization, Citation2020). Further, 33.1 percent of children under age 5 in the African region are stunted, compared to 31.9 percent in South-East Asian countries and 6.4 percent in Western Pacific countries (World Health Organization, Citation2019). The cost of poor child health is significant, as sustainable development cannot be achieved without realizing a child’s rights, including the right to good health and overall wellbeing.

This study explains that due to the diminishing of women's rights in the society that enforced the reform, with consequences on within-household bargaining and utility outside marriage, there will subsequently be an adverse effect on a child's wellbeing. Studies have shown a direct link between a child's wellbeing and a mother's empowerment (Deutsch & Silber, Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2020). Other studies relate improvement in women's intra-household bargaining power for resource access and control of children's health outcomes (Hahn et al., Citation2018).

Finally, our results suggest that there can be important generational effects from the enforcement of religiously motivated policies and reforms. Our emphasis is not on the religion but the mode of the reform enforcement, as others have shown that similar religious rule with a secular approach causes increases in a woman’s development and empowerment (Meyersson, Citation2014). Thus, depending on their interpretation, there are immense benefits from the religious codes, which can propel women into considerably better bargaining positions within or outside the household. The findings of this paper suggest that such benefits could have generational health benefits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The twelve States are Zamfara, Katsina, Sokoto, Kebbi, Niger, Kaduna, Bauchi, Kano, Jigawa, Gombe, Yobe, and Borno. Some states (e.g. Kano) adopted a new Penal Code, whereas others (e.g. Niger) only added to the pre-Reform Penal Code some clauses specific to Muslims (see Godefroy, Citation2018).

2 Hisbah associations/groups were responsible for enforcing the codes of the legal reform, and the extent of the enforcement varies by state. They mostly patrol the neighborhood to observe any violations of the religious law.

3 Some studies (e.g. Chari et al., Citation2017; Kulkarni, Frongillo, Cunningham, Moore, & Blake, Citation2021) point to the adverse wellbeing of children from declining maternal bargaining power and autonomy 2021.

References

- Ajefu, J. B., Singh, N., Ali, S., & Efobi, U. (2022). Women’s inheritance rights and child health outcomes in India. The Journal of Development Studies, 58(4), 752–767. doi:10.1080/00220388.2021.2003333

- Alfano, M. (2017). Islamic law and investments in children: Evidence from the Sharia introduction in Nigeria. London: Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration.

- Almond, D., & Currie, J. (2011). Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(3), 153–172.

- Baird, S., McIntosh, C., & Ozler, B. (2019). When the money runs out: do cash transfers have sustained effects on human capital accumulation? Journal of Development Economics, 140(C), 169–185.

- Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2, Part 2), S279–S288. doi:10.1086/260166

- Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 84(4, Part 2), S143–S162. doi:10.1086/260536

- Bourbeau, H., Umar, M. S., & Bauman, P. (2019). Shariah criminal law in Northern Nigeria: Implementation of expanded Shariah penal and criminal procedure codes in Kano, Sokoto, and Zamfara States. Washington: United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

- Chari, A. V., Heath, R., Maertens, A., & Fatima, F. (2017). The causal effect of maternal age at marriage on child wellbeing: Evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics, 127, 42–55. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.02.002

- Clingingsmith, D., Khwaja, A., & Kremer, M. (2009). Estimating the impact of the Hajj: Religion and tolerance in Islam's global gathering. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1133–1170. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.3.1133

- Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. (1999). Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999. Retrieved from https://publicofficialsfinancialdisclosure.worldbank.org/sites/fdl/files/assets/law-library-files/Nigeria_Constitution_1999_en.pdf.

- Deininger, K., Goyal, A., & Nagarajan, H. (2013). Women’s inheritance rights and intergenerational transmission of resources in India. Journal of Human Resources, 48 (1), 114–141. doi:10.1353/jhr.2013.0005

- Deutsch, J., & Silber, J. (2019). Women’s empowerment and child malnutrition: The case of Mozambique. South African Journal of Economics, 87(2), 139–179. doi:10.1111/saje.12223

- Glaze, M. (2018). Historical determinism and women’s rights in Sharia law case. Western Reserve Journal of Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, 50 (1), 349–376.

- Godefroy, R. (2018). How women's rights affect fertility: Evidence from Nigeria. The Economic Journal, 129(619), 1247–1280. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12610

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People's opium? Religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 225–282. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00202-7

- Hahn, Y., Nuzhat, K., & Yang, H. (2018). The effect of female education on marital matches and child health in Bangladesh. Journal of Population Economics, 31(3), 915–936. doi:10.1007/s00148-017-0673-9

- Harari, M. (2019). Women’s inheritance rights and bargaining power: evidence from Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 68(1), 189–238. doi:10.1086/700630

- Harnischfeger, J. (2004). Sharia and control over territory: conflicts between “settlers” and “indigenes” in Nigeria. African Affairs, 103(412), 431–452. doi:10.1093/afraf/adh038

- Heath, R., & Tan, X. (2020). Intra-household bargaining, female autonomy, and labor supply: Theory and evidence from India. Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(4), 1928–1968. doi:10.1093/jeea/jvz026

- Heggeness, M. L. (2020). Improving child welfare in middle income countries: The unintended consequence of a pro-homemaker divorce law and wait time to divorce. Journal of Development Economics, 143, 102405. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102405

- Ibrahim, H. (2012). Practicing Shariah Law: Seven strategies for achieving justice in Shariah Courts. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association.

- Kose, E., Kuka, E., & Shenhav, N. A. (2021). Women’s enfranchisement and children’s education. American Economic Journal, 13(3), 374–405.

- Kulkarni, S., Frongillo, E. A., Cunningham, K., Moore, S., & Blake, C. E. (2021). Gendered intra-household bargaining power is associated with child nutritional status in Nepal. The Journal of Nutrition, 151 (4), 1018–1024. doi:10.1093/jn/nxaa399

- Li, L., Wu, X., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Intra-household bargaining power, surname inheritance, and human capital accumulation. Journal of Population Economics, 34(1), 35–61. doi:10.1007/s00148-020-00788-0

- Meyersson, E. (2014). Islamic rule and the empowerment of the poor and pious. Econometrica, 82(1), 229–269.

- Miller, G. (2008). Women’s suffrage, political responsiveness, and child survival in American history. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), 1287–1327. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.1287

- Odok, G. E. (2020). Disruption of patriarchy in northern Islamic Nigeria. Gender, Place, and Culture, 27(12), 1663–1681. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2019.1693346

- Roy, S. (2015). Empowering women? Inheritance rights, female education and dowry payments in India. Journal of Development Economics, 114, 233–251. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.12.010

- Weimann, G. J. (2010). Islamic criminal law in Northern Nigeria: Politics, religion, judicial practice. Amsterdam: Vossiuspers – Amsterdam University Press.

- World Health Organization. (2019). UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: Levels and trends in child malnutrition. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/jme-2019-key-findings.pdf?ua=1 (September 10, 2020).

- World Health Organization. (2020). Early child development – maternal and child mental health. Geneva: WHO.

Appendix

Table A1. Effects of the reform on migration

Table A2. Effects of the reform when excluding women from neighboring states

Table A3. Effects of the reform – Placebo Test