Abstract

Fishing provides livelihoods and food for millions of people in the Global South yet inland fisheries are under-researched and neglected in food and nutrition policy. This paper goes beyond the rural focus of existing research and examines how urban households may use fishing as a livelihood strategy for coping with food insecurity. Our study in Brazilian Amazonia is based on a random sample of households (n = 798) in four remote riverine towns. We quantitatively examine the inter-connections between fishing and food insecurity, and find that fishing is a widespread coping strategy among disadvantaged, food insecure households. Fisher households tend to be highly dependent on eating fish, and for these households, consuming fish more often is associated with a modest reduction in food insecurity risks. Fishing provides monthly non-monetary income worth ≤ USD54 (equivalent to ∼12% of mean monetary income), potentially reducing food insecurity risks almost as much as the conditional cash transfer Bolsa Família. We estimate that nearly half a million inhabitants of the region’s remote, riverine urban centres are directly dependent on a household member catching fish, a nutritious and culturally preferred food. Consequently, small-scale urban fishers must be recognised in policy debates around food and nutrition security and management of natural resources.

1. Introduction

Food insecurity and malnutrition are increasingly urbanised (Crush & Caesar, Citation2014; Kimani-Murage et al., Citation2014; Ruel, Garrett, Yosef, & Olivier, Citation2017), yet development agencies continue to frame these as predominantly rural problems (Battersby, Citation2017). Critical is that urban food insecurity and malnutrition is largely an outcome of poverty and related barriers in accessing affordable, nutritious food, rather than due to insufficient availability (Frayne, Crush, & McLachlan, Citation2014). We engage with Tacoli’s (Citation2017) call for research and policy attention around livelihoods which may enable the urban poor cope with food insecurity.

Our paper’s contribution is engaging with inland (non-marine) small-scale fishing as a livelihood through which urban households may be able to access nutritious and favoured foods and support their food security. Small-scale fisheries provide livelihoods for millions of rural people and make important, broader contributions to food and nutrition security (Belton & Thilsted, Citation2014; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition [HLPE], Citation2014; Loring et al., Citation2019). Importantly, fishing can provide poor households with welfare benefits through cash income and food (Béné, Citation2009; Hartje, Bühler, & Grote, Citation2018). Numerous studies explore related challenges around fisheries governance, access and sustainable use, and inter-linkages with marginalisation and pro-poor development (see Béné, Hersoug, & Allison, Citation2010). Yet urban small-scale fisheries are practically un-studied despite their enormous relevance to poverty alleviation and food insecurity policies (Kadfak, Citation2019). Accordingly, our study helps initiate an urban dimension within on-going debates about how small-scale fisheries contribute to food security and poverty alleviation in the Global South (Béné et al., Citation2016). Specifically, we focus on small-scale fishing as a livelihood activity for coping with poverty and food insecurity in Amazonia’s riverine provincial towns, far from major deforestation frontiers.

1.1. Neglect of small-scale inland fisheries

The benefits of inland capture fisheries for food security and livelihoods are poorly understood, especially in comparison to marine fisheries and aquaculture (Funge-Smith & Bennett, Citation2019). Small-scale fisheries offer significant ecological and social benefits relative to large-scale fishing, but are long neglected by scientists and policy-makers due to historical dominance of monitoring paradigms for industrial fishing in the Northern hemisphere (Kolding, Béné, & Bavinck, Citation2014). Consequently, inland fisheries are considered ‘invisible’ resources due to deficient monitoring and under-reporting, and they are largely ignored in food and nutrition policies (Lynch et al., Citation2017). For instance, inland fisheries provide over 40 per cent of reported finfish production (Lynch et al., Citation2016) yet are overlooked in the Sustainable Development Goals (Thilsted et al., Citation2016). Cooke et al. (Citation2016) argue that research assessing the importance of inland fisheries for food security and livelihoods is essential for integrating these systems into water management policy frameworks. Importantly, food insecurity causes imbalanced, less diverse and poor-quality diets, and when severe or long-term, induces malnutrition (Moradi et al., Citation2019). Fishes provide vital sources of energy, protein, micro-nutrients (for example, bioavailable calcium, zinc, iron) and omega-3 fatty acids important for child and maternal health (HLPE, Citation2014; Thilsted et al., Citation2016).

Within the fisheries literature there is an evolving, complex understanding of the linkages between poverty, vulnerability and food insecurity. Earlier research tended to convey rural small-scale fishers in the Global South as the ‘poorest of the poor’. The fisheries sector was considered to represent the most disadvantaged rural people (Béné, Mindjimba, Belal, & Jolley, Citation2001). Hence, fishing was framed as a livelihood of last resort for the chronically poor, reflecting the low productivity of this sector (see Béné, Citation2003). Although poverty can be transitory rather than chronic, even non-poor fishers can be highly vulnerable, through high exposure to shocks and stressors (for example, this study from Democratic Republic of the Congo, Béné, Citation2009). Yet, recent commentary emphasises how inland fisheries – which are mainly small-scale – can provide complimentary livelihoods and a safety net for the poor due to low entry barriers (Lynch et al., Citation2017). For instance, a large proportion of the littoral-sector fishers in Lake Tanganyika have other primary livelihoods (Lowe et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, in the Mekong, instead of representing a poverty trap, fishing enables households to reduce their food expenditure and reduce seasonal food insecurity (Hartje, Bühler, & Grote, Citation2016).

1.2. Provincial urban poverty

High rates of poverty and rapid population growth in smaller urban centres lead Christiaensen and Kanbur (Citation2017) to advocate reorienting public policy from its current metropolitan bias towards smaller towns. Ferré, Ferreira, and Lanjouw (Citation2012) find people living in smaller cities tend to be significantly poorer than their metropolitan counterparts. In Brazil, the trend is severe and, moreover, rural out-migrants arriving in these towns tend to experience deepening poverty in the years following arrival (Belik, Citation2015).

In Amazonia, rapid urbanisation has contributed to the vulnerability of urban populations (Mansur et al., Citation2016). Poverty and inequality in the region is also partly associated with relative inaccessibility. For example, imported foodstuffs are more expensive in remote riverine towns, exacerbating the challenges of limited employment and low incomes (Parry et al., Citation2018). They calculate over 900 thousand people live in 68 such towns, and find provision of education and healthcare is relatively weak in these places. Research in four of these towns shows high rates of childhood anaemia (Carignano Torres et al., Citation2022). Given that road-building in Amazonia preempts migration, social turmoil and disease outbreaks (Barcellos, Feitosa, Damacena, & Andreazzi, Citation2010), and drives deforestation and climatic change (Tallman et al., Citation2020), support is required to foster sustainable development pathways (and related livelihoods) in these towns. Amazonia’s small-scale fisheries may contribute to one such pathway.

1.3. Amazonia’s important inland fishery

In Amazonia, there is strong evidence that fishing and fish consumption are important in supporting riverine traditional populations, which are often poor and marginalised. Dietary dependence on fish is very high in the region, particularly among the rural poor. Rural Amazonians consume high quantities of fish (sometimes exceeding 200 kg/person/year (Isaac & de Almeida, Citation2011)) which contributes vital dietary protein in the context of a relatively non-diverse staple-food diet (Murrieta & Dufour, Citation2004; Silva, Citation2009). In Amazonia, there is long-standing interest in the practices of rural fishing communities, and commercial fleets feeding big cities (Batista & Petrere Júnior, Citation2003; Junior & Batista, Citation2019), and international markets (de Oliveira Moraes, Schor, & Alves-Gomes, Citation2010). Three decades ago, Bayley and Petrere (Citation1989) estimated that 61 per cent of the Amazon fishery’s yield was from local market and subsistence fishers yet small-scale fishers in smaller towns remain overlooked, and the invisibility of urban and rural semi-subsistence fishing contributes to under-estimation of landings (Lorenzen, Almeida, & Azevedo, Citation2006).

One of the few studies of wildlife-use among urban Amazonian populations found that income poverty was a significant predictor of engaging in fishing (Parry, Barlow, & Pereira, Citation2014). Moreover, around four-fifths of households in small urban centres ate fish nearly every day. Around half of the poorest households reported fishing whereas fishing was much less common among non-poor households (Parry et al., Citation2014, ). Pedrosa, Lira, and Maia (Citation2018) studied metropolitan estuarine fishers and shellfish gatherers in North-East Brazil, finding that urban fishers were somewhat invisible to policy-makers and had weak relationships with environmental and fisheries institutions. In addition, Kadfak (Citation2019) examined how rural fishers in Karnataka state, India had moved to peri-urban areas and fished as a way to manage risks.

Fish availability in Amazonia is highly seasonal because a flood pulse in the wet season strongly affects the social-ecological system, including the relative abundance and catchability of fish stocks (Junk, Soares, & Bayley, Citation2007; Tregidgo, Barlow, Pompeu, & Parry, Citation2020). The seasonal decline in fish catch rates causes severe seasonal food insecurity in rural areas with a four-fold increase in the likelihood of not eating for an entire day (Tregidgo et al., Citation2020). It is unclear whether urban fishers will likely be affected by, or respond to, seasonal variation in fishing and food insecurity in the same way.

1.4. Study aim and research questions

Our aim here is to understand the role of small-scale inland fishing in supporting the food security of urban Amazonians. In so-doing, we address important knowledge gaps around how urban fishing may contribute to livelihood strategies in the Global South. We adopt a broad definition of small-scale fishing because our experience tells us that, in Amazonia, this activity is often part of a diverse portfolio of livelihood strategies (sensu Smith, Khoa, & Lorenzen, Citation2005). Defining small-scale fishers only by stated occupation leads to under-reporting and may exclude the majority of households that fish (Nasielski, Kc, Johnstone, & Baran, Citation2016). Likewise, using centralised urban markets to study urban fisheries (for example, Hallwass, Lopes, Juras, & Silvano, Citation2011) will overlook those fishing for domestic consumption, sharing in social networks or selling (some) fish ad hoc. We envisage that fishing may contribute to urban household food security as either a supplemental subsistence activity or primary occupation.

Our empirical study is based on a random population sample of households in four riverine Amazonian towns, with surveys conducted in the wet and dry seasons. Our research was motivated by three questions. First, is fishing associated with multi-dimensional poverty and household food insecurity? Based on work in rural fishing communities, reviewed by Béné et al. (Citation2016), we hypothesize that urban fishers tend to be relatively poor and disadvantaged and use fishing as a strategy to cope with food insecurity whether or not it is their primary livelihood. Second, to what extent are urban fishers dependent on fish as food, considering expenditure on fish and frequency of consumption relative to other animal-based foods? We might expect a similar pattern as found in rural fishing communities, where small-scale fishing households tend to consume more fish (Hartje et al., Citation2016). Third, is success at fishing associated with lower perceptions of food insecurity? For each question, we also consider whether there is seasonal variation in the outcome (fishing activity, dependency, and food insecurity).

For Q1, we compare food insecurity levels of fishers and non-fishers and then use logistic regression to see if the decision to fish is associated with household food insecurity and socio-economic covariates. For Q2, we compare the consumption frequency of different animal-based foods (including fish) between fishers and non-fishers, and evaluate local market prices of these foods. We also compare domestic fish stores and recent expenditure on fish among the two groups. For Q3, we use propensity scores matching to understand the association between fishing and food insecurity, and whether additional fish consumption among fishers is associated with variation in household food insecurity. Accordingly, we examine whether the home consumption of caught fish is associated with variation in food insecurity, sensu Gomna and Rana (Citation2007) and HLPE (Citation2014, p. 36). We do not explicitly investigate the potential influence of cash income from selling fish (albeit this income would be captured in total household earnings), which is the other channel through which fishing may support food security (Hartje et al., Citation2018). We expect that fishing more (unmeasured) leads to higher fish consumption (measured, controlling for income), and this is associated with a reduction in food insecurity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and data collection

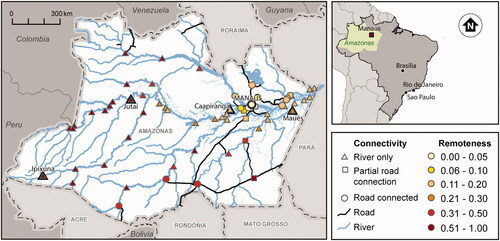

Our cross-sectional study was carried out in Amazonas State, Brazil. The sampling design was intended to be broadly representative of our ‘universe’ of interest; provincial, riverine Amazonian towns unconnected to the road network. We chose four such towns with varying accessibility to other urban centres within a hierarchical urban network () (Parry et al., Citation2018). Our definition of urban follows the official classification of urban and rural areas in each municipality; urban zoning is defined by municipal law. Although some Amazonian towns are relatively small, they provide services such as hospitals, secondary and university education, as well as private-sector services such as banks and shops. Important to our understanding of this food system is that even within towns, supermarket penetration is low, and foodstuffs are often accessed outside of market exchange (Supplementary Materials).

Figure 1. Sampled towns within the study universe of riverine urban centres unconnected to the road network in Amazonas State, Brazil.

Data were collected during the dry season (08-to-12/2015 with approximately one month in each town), and wet season (03-to-07/2016) with a sampling target of 100 households (not revisited) per town, per season. Our final sample was 798 households (Supplementary Materials; ). The questionnaire was piloted in Manaus and a nearby small town (Autazes), then adjusted.

Table 1. Regressor statistics: comparing fisher (n = 320) and non-fisher households (n = 478)

Households were randomly selected although we adjusted sampling density according to the number of households per census sector from the Brazilian government’s 2010 population census (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica [IBGE], Citation2010a). Sampling points were geolocated using Open Street Map and Google Earth, and a purchased image for Jutaí, and were restricted to the habitable area of each city, defined as ≤20 m radius of streets or river-edge. We approached the nearest household to each sample location for interview and noted the XY coordinates of all households. This research received ethical approval from Brazil’s national health research ethics committee (CONEP-CNS; protocolo 45383215.5.0000.0005) and Lancaster University (S2014/126).

Our structured questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic characteristics; origin (rural/urban), number of people, age, and formal education received. Economic questions included monthly earnings (receipt of salaries, rent or other remuneration), and governmental cash transfers (for example, state retirement pension, Bolsa Familia [Family Grant], Seguro Defeso [fisheries closed-season payments]). We asked if anyone in the household fished and, if so, how many times during the previous 30 days. We asked households on how many days during the previous seven days had they consumed meals including fish, beef, eggs, canned meat, sausage or chicken.

We measured perceptions of food insecurity using a questionnaire modified from the Brazilian Household Food Insecurity Scale (EBIA)(Supplementary Materials). Our modified 18-point scale captures access to food and recent experiences of hunger in the household that varied from 18 (severely food insecure) to 0 (food secure). The food insecurity levels we present follow the definitions underlying the EBIA (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios, Citation2013, p. 28).

Market prices of different forms of animal protein were assessed in each town by interviewing local shop-owners or market-stall owners (six per town per season, if all items were available. Total of 44 surveys) using a structured questionnaire (see Davies, Frausin, & Parry, Citation2017).

2.2. Data processing and analysis

Households were classified according to recent participation in fishing, whatever the scale of the activity. Households are fishers if someone fished in the last 30 days and non-fishers if not. We bounded monetary earnings at the 98th percentile because it was highly skewed, and winsorising prevents high-value outliers from disproportionately affecting the parameter estimate (Kerm, Citation2007). We assessed dietary characteristics using consumption rates of key animal-based foods.

To answer Q1 we first compared the relative food insecurity (membership of different levels and mean score) of fishers and non-fishers. We performed bivariate tests to assess socio-economic differences between the two household types, including participation in a local fishers’ organisation. Membership indicates being a (semi-)professional fisher. We performed a logistic regression to test how the decision to fish is associated with food insecurity and other socio-economic characteristics, enabling us to see how a unit change in a covariate relates to the odds of being a fishing household. Predictors included food insecurity score, number of household members (people), earnings, cash transfers, and season.

We answer Q2 using two kinds of analysis. First, we compared the consumption frequency of various animal-based foods between fisher and non-fisher households, and performed bivariate t-tests. Related, we visually assessed the relative frequency of fish consumption (days/week). Second, we compared the market price of fresh fish with two other important food-types, beef and chicken. Finally, we compared domestic stores of fish (frozen, refrigerated or salted) and expenditure on fish (previous seven days) between fishers and non-fishers.

To address Q3 we analysed how fishers’ perceived risks of food insecurity are associated with the frequency of fish consumption, controlling for other socio-economic characteristic variables. We assume that fish consumption (days/week) by fisher households partly reflects their success at catching fish. Given we expect the poorest and most vulnerable households use fishing as a coping mechanism we hypothesise that, when controlling for income, higher fish consumption will be associated with lower food insecurity among fishers. For non-fishers, we expect that fish consumption is not associated with variation in a household’s risks of food insecurity because they purchase their fish, and it can be substituted with other foodstuffs. We ran models including; fisher and non-fisher households (models 1 and 4), non-fisher households (model 2 and 5), and fisher households (model 3 and 6).

For Q3 we employed Poisson regression models and propensity score matching (PSM). Poisson regressions (models 1–3; all households, non-fishers only, and fishers only) used the total sample, with food insecurity score as the dependent variable and fish.eat.days, people, earnings, cash transfers, and season as predictors. PSM models (models 4–6, all households, non-fishers only, and fishers only) were designed to robustly assess the relationship between fishing and the perceived risks of food insecurity (excluding season as a predictor; see Supplementary Materials). We interpret both Poisson model and PSM results in terms of associations rather than causal effects.

3. Results

3.1. Fishing to cope with poverty and food insecurity?

Fishing was common; in 40 per cent of households someone had recently fished, from 25 per cent in Maues to 48 per cent in Caapiranga (Supplementary Materials; ). About 44 per cent of households fished during the dry season compared to 36 per cent in the wet season. Fisher households reported fishing an average of seven days per month (wet season mean = eight days; dry season = six days).

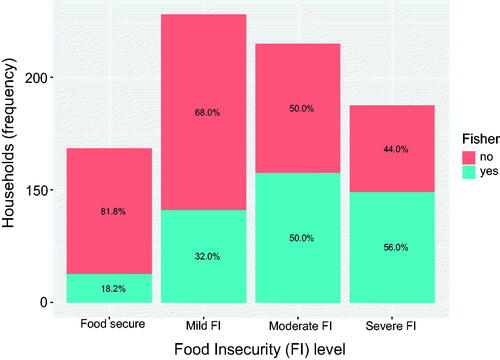

3.1.1. Food insecurity

Fishers were much more food insecure than non-fishers (). Nearly a third (30.6%) of fishing households were severely food insecure, compared to 16.1 per cent of non-fishers (Supplementary Materials; ). Moderate food insecurity was also higher among fishers (35.9%) than non-fishers (24.1%). A third of fishing households experienced mild food insecurity (25.6%) or were food secure (7.8%). In contrast, most non-fishers were either mildly food insecure (36.4%) or food secure (23.4%). Related, fishing increases along a gradient of food secure to severely food insecure (); only 18.2 per cent of food secure households fish, compared to most (56.0%) severely food insecure households.

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of food insecurity levels among surveyed urban households. Data are separated by recent fishing activity and percentages are shown within bars.

Table 2. Results from probability of fishing model (logit)

3.1.2. Social and economic characteristics

Socio-economic characteristics (people, earnings, cash transfers) varied significantly different between fisher and non-fisher sub-populations (). The mean food insecurity score was 40 per cent higher for fishers (p < .01). Fishing households were larger (mean 5.59 people versus 4.52) and had lower monthly earnings (mean R$1168 (USD316; mean exchange rate R$3.70: USD1, 08/2015-07/2016) than non-fishers (R$1481; USD400). Total cash transfers were not significantly different between fishers and non-fishers. Bolsa Família payments are conditional on income poverty and number of children, and the mean was R$165 (USD45) for fisher households and R$107 (USD29) for non-fishers. Cash transfers were not correlated with fishing or food insecurity (Supplementary Materials; ). Total mean monthly household income (combining earnings and cash transfers) was R$1721 (USD465) for fishers and R$2099 (USD568) for non-fishers.

A third of fisher households reported membership of their local fishers association (Supplementary Materials; ). Registered fishers in Brazil receive Seguro Defeso, and 11 per cent of non-fishers were registered as fishers, indicating either opportunistic registration to claim this benefit, or that our definition of fishers (based on previous 30 days of activities) excluded some household which are involved in fishing. Most fishers were non-registered, hence their fishing activity would be for subsistence or as an occasional source of income. Summarising, fishing households are generally more food insecure, larger, and slightly poorer than non-fishing households.

Table 3. Number of days in which different kinds of animal-based meals were consumed during the previous seven days, separated by fisher and non-fisher households

3.1.3. Decision to fish model

We found a strong positive, significant (p < .01) relationship between food insecurity and the probability of fishing (). An increase of 1 unit in the food insecurity score (relating to adopting one extra coping mechanism) is associated with 10.8 per cent greater odds of fishing. Household size is also a significant (p < .01) correlate of fishing; an extra household member is associated with 14.6 per cent greater odds of fishing. Bigger families are more food insecure and poor, given that larger households do not have significantly higher earnings (Supplementary Materials; ). Consequently, larger families have greater food needs, and more potential household members to go fishing. When controlling for other factors, earnings are apparently unrelated to fishing, whereas higher cash transfers are associated with reduced probability of fishing (p < .10).

Finally, even when controlling for earnings and food insecurity, going fishing is 38.1 per cent less likely in the wet season (p < .01). Overall, this analysis demonstrates that the propensity to go fishing is associated with food insecure households, larger households and the dry season.

3.2. How dependent are fishing households on eating fish?

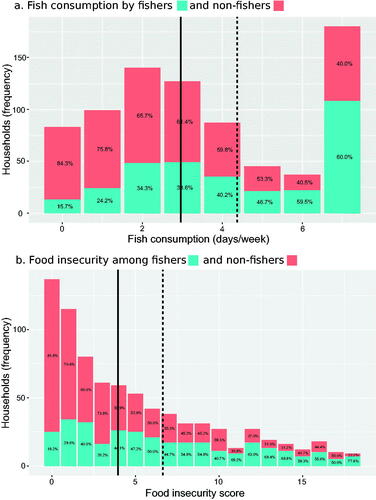

Fisher households tended to be highly dependent on eating fish. Fishers consume fish 48 per cent more often than non-fisher households (mean 4.4 and 3.0 days/week, respectively; ), suggesting that eating caught fish is a direct benefit of fishing. The relationship between fishing and fish consumption is non-linear with a bi-modal distribution (). For 33.8 per cent of fisher households, fish are consumed daily and are their principal animal-based food.

Figure 3. Frequency distribution of surveyed urban households for (a) fish consumption and (b) perceptions of food insecurity. Data are separated by fisher and non-fisher households and percentages are shown within bars. Vertical lines show mean consumption and food insecurity for fishers (dotted lines) and non-fishers (solid lines).

Fisher households had twice as much fish stored compared to non-fishers (mean 3.81 kg ± 0.51, versus 1.89 kg ± 0.20 SE; p < .001; Welch 2-sample t-test) and the median stores held by fishers (1.71 kg) was three times that of non-fishers (0.50 kg). However, fishers spent much less money on fish; a weekly mean of R$10.39 ± 1.14 (USD2.81 ± 0.31) or median of R$0, versus R$21.57 ± 1.20 (USD5.83 ± 0.32) or median of R$17 (USD4.60) for non-fishers. Put differently, only 33.4 per cent (107/320) of fisher households had spent money buying fish, versus 70.9 per cent (339/478) of non-fisher households. Only 62 (19.4%) fishers had sold any fish in the previous 30 days, indicating that most fishing is for domestic consumption, or possibly sharing with other households. Evidently, fishing enables households to access larger quantities of fish, and urban fishers typically spend little or nothing buying fish.

Broader food practices varied significantly between fisher and non-fisher households, based on consumption of animal-based foods (Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests; ). Fishers more regularly consume low-quality animal foods (sausage and canned meat; Davies et al., Citation2017). Conversely, fishers eat the more nutritious animal foods less often than non-fishers (chicken on 32% fewer days; beef on 30% fewer days). Our findings suggest that fish is the principal animal-based food eaten by fisher households, which are relatively poor and food insecure. For fishers, ‘fish days’ are as frequent as days with either chicken, meat and eggs, combined. For non-fishers, fish consumption is only around half as frequent as chicken, meat and egg consumption, combined.

Fish prices (mean = R$6.15/kg ± 6.61 SD) were slightly lower (but more variable) than chicken (R$7.06/kg ± 1.98 SD) and much less than beef on-the-bone (R$13.29/kg ± 4.77 SD). Non-fishers are less dependent on fish, and our findings indicate that necessity is probably why many poor urban households go fishing, and not because of relatively strong preferences for eating fish. Summarising, fish is the most important high-quality animal-based food for both fisher and non-fishers, although fishing enables the former to eat fish more regularly, and spend less. Moreover, fisher households tend to be relatively poor, and a sizeable minority are almost entirely dependent on fish for animal-based protein and other vital nutrients.

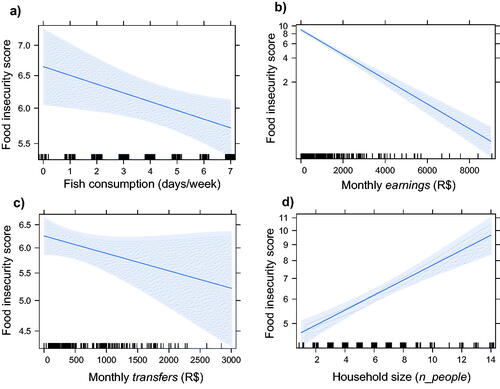

3.3. How does fishing relate to perceptions of food insecurity?

Fisher households were significantly more food insecure than non-fishers. When controlling for other variables, fishers’ risk of food insecurity is between 36.6 per cent (model 4) and 40.0 per cent (model 1) higher than non-fishers (). However, higher fish consumption among fishers is associated with a modest reduction in their food insecurity risks (). Specifically, eating fish on one extra day per week is associated with approximately 2 per cent lower risks (model 6 and model 4). Given that fishers eat, on average, 1.4 extra fish meals per week, this additional consumption may reduce their food insecurity risks only slightly – by between 2.2 per cent (model 4) and 3.0 per cent (model 6). If assuming a fisher catches all the fish they eat (mean 4.4 meals/week), then fishing would be associated with greater risk reductions of between 6.9 per cent (model 4) and 9.2 per cent (model 6). However, many fisher households eat fish daily and, for those daily-consumers catching all their own fish, we can expect larger potential reductions (−11.0% [model 4]; −14.6% [model 6]) in these risks. Conversely, among non-fishers, fish consumption is not associated with significant changes in food insecurity, when controlling for other factors.

Figure 4. Modelled relationships between household characteristics and food insecurity in fisher households (model 6; propensity score matching). Shading indicates 95 per cent confidence intervals. The marks along the x-axes are ‘rug plots’ which indicate the distribution of the data, analogous to a one-dimensional scatter plot.

Table 4. Fishers, non-fishers and food insecurity – model results

Earnings was associated with lower food insecurity risks for all household types (p < .01). Overall, increasing monthly household income by R$100 (USD27) is associated with 4 per cent lower food insecurity risks (models 1 and 4), with a similar effect for fishers (−3%; model 6, see ). Fisher households catching all the fish they eat (equivalent to eating fish 19 days/month), could be reducing their food insecurity risks by an amount (9.2% using the propensity scores model) comparable to earning R$200 (USD54) more per month (8% lower risks). Our price data shows R$200 could buy 32.5 kg of fish, equating to 1.7-kg fish/day, approximately the quantity an Amazonian family would consume for a main meal, plus carbohydrates. Summarising, fishing provides non-monetary income worth ∼ R$200/month for households that catch all the fish they eat.

The relationship between cash transfers and food insecurity was varied. Higher transfers were associated with lower food insecurity (p < .01) for the total sample (models 1 and 4) and non-fishers (models 2 and 5). However, transfers were not linked to significant variation in food security risks of fishers (). This is intriguing because average transfers are not significantly different between fishers and non-fishers (). Note this is a marginal effect of transfers – controlling for family size – hence it represents the effect of per capita transfers. There may be complex interactions between transfers, household labour, and food insecurity, in this mostly poor sub-population. For instance, starting to receive a retirement pension might coincide with reduced household labour, or prompt them to reduce or stop fishing. Larger households tend to be more food insecure (p < .01), although the burden of more people was lower in fisher households. When controlling for cash income, an extra person is associated with 5.7-5.8 per cent higher food insecurity risks in fisher households (models 3 and 6; ) compared to 10.3 per cent to 11.7 per cent among non-fishers (models 5 and 2).

Overall, food insecurity risks are 15.3 per cent higher in the wet season (model 1). When controlling for income and fish consumption frequency, non-fishers experience a 23.8 per cent wet season increase in food insecurity (model 2; p < .01). In contrast, there is no significant seasonal variation in fishers’ food insecurity, when controlling for income and fish meals. Moreover, fishers are relatively food insecure throughout the year. In the wet season, the average fisher is much more food insecure (mean score = 7.4 ± 0.44 SE, median =7) than the average non-fisher (mean = 4.4 ± 0.30 SE, median =2). Fishers’ food insecurity is also worse in the dry season (fishers: mean = 6.0 ± 0.37 SE, median =5; non-fishers: mean =3.5 ± 0.25 SE, median =3).

Summarising, fishing enables poor urban households to eat more fish and may facilitate a modest reduction in their food insecurity risks. However, fishing is only partially effective in compensating for the socio-economic disadvantages experienced by these households.

4. Discussion

Our study’s main contribution is showing that direct access to inland fisheries can provide urban households with a way of responding to poverty and severe food insecurity. We find that fishing is widespread in small Amazonian towns and provides participating households with their main source of high-quality nutrients. Nonetheless, these urban fishers are a diverse group in terms of their dependency on fishing, linked to variation in socioeconomic status, fishing practices and reasons for fishing. Overall, we find some evidence that eating more fish is associated with a modest reduction in their risks of food insecurity. Inland fisheries are considered ‘invisible’ resources largely ignored by policy-makers (Lynch et al., Citation2017) albeit the significance of inland fisheries for rural food security is increasingly recognised (Hartje et al., Citation2018; Youn et al., Citation2014). Finally, we estimate the scale of urban fisheries in Amazonia’s riverine, remote towns and cities; we argue that the voices of urban fishers must be heard in policy debates about fisheries management, urban planning, and protected areas management. Consequently, this study speaks to Lynch et al.’s (Citation2020) call for quantitative valuation (social, economic, nutritional) of inland fisheries, and contributes to debates about the role of small-scale fisheries in supporting food security (Béné et al., Citation2016; Fiorella et al., Citation2014; Hartje et al., Citation2018; HLPE, Citation2014).

4.1. Fishing as an urban livelihood of last resort?

In riverine Amazonian towns, severe food insecurity is widespread among socially disadvantaged households, many of which turn to fishing as a coping strategy. Fishing was more likely among larger households, and those trapped in poverty or living with food insecurity. These households use fishing to draw on their labour, skills and knowledge in order to gain non-monetary (and sometimes monetary, too) income in the form of culturally preferred foods. Amazonia’s fishery is widely accessible to the provincial urban poor because they require relatively few assets (for example, use of a canoe), and there are vast natural resources (but see Castello et al., Citation2013).

The backdrop for our findings is widespread urban poverty and food insecurity (sensu Ruel et al., Citation2017). For instance, in the Amazon estuary up to 90 per cent of people living in very poor urban neighbourhoods experience some level of food insecurity (De Lima et al., Citation2018). Our study corroborates these results, showing that fewer than one-in-six households are food secure whereas over half suffer moderate-to-severe food insecurity. In this sense, our results resonate with research on rural contexts in the Global South which has found fishing is – in many cases – a livelihood of ‘last resort’, and especially important for the poorest of the poor (see Béné et al., Citation2016).

Fishing one-day-in-four shows that it is generally an important livelihood rather than an occasional urban activity. Hence, our study confirms that fishing and other informal activities present vital livelihood options in provincial contexts where regular, secure employment is rare and hard to access (Lowe et al., Citation2019; Parry et al., Citation2014). Given such widespread participation in rural livelihoods, Amazonia’s riverine urban centres have been described as ‘rural cities’ (Padoch et al., Citation2008). Nevertheless, there are long-standing objections to the idea that fishers are inevitably from low-status, marginalised households (Béné, Citation2003; Smith et al., Citation2005). For instance, in coastal Kenya, fishers cover the whole socioeconomic spectrum and fishing as a livelihood varies between individuals and for an individual over time (sometimes they have other alternatives) (Carter & Garaway, Citation2014). This variation is important; fishers in our study are not only from poor households and many will be meeting livelihood objectives beyond food security, including selling fish for income. In our study towns, such sales would occur in the municipal fish market or selling in the street, either by cargo bicycle with an ice box, or a fisher may carry their catch and walk door-to-door, for smaller amounts. Nonetheless, only 19 per cent of fishers had sold any fish in the previous 30 days, indicating that most urban fishing relates to catching fish for domestic consumption.

4.2. Dietary dependence on fish

Urban fishers are heavily reliant on fish for dietary nutrients, and we show they are able to consume fish most days (median four-days per week) without spending precious cash. In the Global South many rural fishers go fishing, in part, to feed their families (Belton & Thilsted, Citation2014; Béné, Citation2009), and this seems to extend to inland urban fisheries, too. As reported by Hartje et al. (Citation2016), we found that fisher households eat fish more often than other households. This is significant because the Amazonian fishery is very diverse, including many highly nutritious species (Rocha et al., Citation1982). Moreover, we found that fishers also eat less of the other higher quality animal-based foods. Non-fishers consume fish several times per week, given its affordability in the urban markets we surveyed (sensu Thilsted et al., Citation2016) and strong cultural preferences for fish. However, non-fishers also consumed chicken, beef as well as cheaper, less-nutritious foodstuffs (for example, canned meat). This finding is relevant to emerging scholarship on the nutrition transition in Amazonia towards lower quality processed foods (Piperata, McSweeney, & Murrieta, Citation2016; van Vliet et al., Citation2015). Heilpern et al. (Citation2021) used modelling to explore large-scale nutrition transitions in the Peruvian Amazon, concluding that substituting inland capture fishing with chicken and farmed-fish could exacerbate iron deficiencies. Our results suggest the pace and health consequences of the nutrition transition can be softened when the urban poor have direct access to inland fisheries. It remains unclear how this finding may apply to other contexts in the Global South. Fishing livelihoods have been linked to improved food security – across income gradients – in rural Cambodia (Hartje et al., Citation2018) whereas, around Lake Victoria, engaging in fishing was not directly associated with fish consumption or improved food security (Fiorella et al., Citation2014).

Most of the provincial urban fishers we identified were non-professionals, probably fishing largely for their own consumption. For Smith et al. (Citation2005) this is a ‘survival’ strategy, in conjunction with other livelihoods. However, this merges into his ‘semi-subsistence diversification’ strategy because we observe that small-scale urban fishers in Amazonia may sell some surplus, trade or donate fish through their social networks. Nevertheless, many of our interviewees would not self-identify as fishers if asked their occupation (Nasielski et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2005) and our findings suggest the main way in which fishing as a livelihood is (partially) supporting urban food security is by providing a direct source of food, rather than income to buy food. Beyond this home consumption, we note that sharing and exchange of fish contributes to community connectedness in Amazonia, and supports food security in poor neighbourhoods (Lee et al., Citation2018). Semi-subsistence fishers are likely overlooked when studies identify fishers through urban markets (for example, Hallwass et al., Citation2011), rather than a randomised household survey (such as ours).

Around a third of the fishers in our sample are registered (semi)-professional fishers and supply local urban markets, at least sometimes. These fishers use more specialised practices intended to increase their catch and earnings though dedicating more time and higher levels of physical capital (for example, more ice, larger gill nets), social capital (for example, membership of fisher associations), and human capital (for example, skills, knowledge) (Smith et al., Citation2005). Of course this strategy also benefits non-fishers who buy fish in the local markets (sensu Lowe et al., Citation2019). In towns along the Amazon’s main-stem (for example, Jutaí), some fishing is geared towards catching catfishes (mainly Brachyplatystoma spp.) for export (de Oliveira Moraes et al., Citation2010; Fabré & Barthem, Citation2005). Given regional taboos against consuming catfishes, in these places part of the (semi)-professional urban fishers’ catch will not be eaten by local people. We found that non-fishers experience greater food insecurity during the wet season than in the dry season. This could relate to seasonal changes in the prices or local availability of important foodstuffs, including fish. Our experiences show that in Maués, for example, during the wet season tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) from aquaculture is one of the only fish-species consistently available, yet this ‘premium’ species (>R$10/kg (USD2.70)) is unaffordable to poorer households. Fabinyi, Dressler, and Pido’s (Citation2017) work on marine fisheries in the Philippines shows how trade is central to fully understanding the linkages between fish and food security because, for example, selling fish can enable households to buy other foodstuffs. Finally, although (semi-)professional urban fishers in Amazonia are more selective, productive, and invest more resources than rural fishers (Hallwass et al., Citation2011), we question whether this also applies to (semi-)subsistence urban fishers.

4.3. Can fishing alleviate urban food insecurity?

Eating fish more often – which evidently reflects success at fishing rather than market purchases – is associated with a modest reduction in food insecurity risks among urban fishers. We estimate that fishing provides households that catch all the fish they eat with non-monetary income worth ∼ USD$54 per month, equivalent to ∼12 per cent of fishers’ mean monetary income. If causal, this result means that fishing provides a reduction in urban food insecurity risks almost equivalent to the benefits of the conditional cash transfer, Bolsa Família. The precise relative potential benefits of each will depend on fishing frequency and success, and the means-tested amount a household receives in Bolsa Família. Nonetheless, this finding is important given the policy’s modest effectiveness in reducing food insecurity in Amazonia (Piperata et al., Citation2016), and demonstrates that access to natural capital is an important advantage of living in a provincial remote town. Fishing is associated with partial compensation for some of the structural challenges facing these marginalised urban populations; including low levels of investment, disconnect from other cities, income poverty and unemployment, and higher imported food prices (Parry et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, inland fisheries seemingly provide a safety net for poor, food insecure urban households. Our cross-sectional study does not allow for causal inference and we cannot rule out the possibility that – instead of providing a safety net – fisher households are poor (or food insecure) because they fish (that is, inland fisheries as a ‘trap’). The somewhat paradoxical finding that catching and eating fish intersects with urban food insecurity mirrors a broader geographical reality. At 30-kg per capita annually, fish consumption in Amazonas is over four times the Brazilian average yet food security in this state is 10 per cent lower than the national picture (IBGE, Citation2010b).

4.4. Seasonality in urban fishing?

More urban households go fishing in the low-water dry season, when fish in Amazonia tend to be easier to catch because they are concentrated in smaller water-bodies (that is, fish density increases). During the wet season, rivers rise and flood into forest ecosystems and fishes disperse (that is, fish density decreases), which research shows depresses catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) for fishers (Batista & Petrere Júnior, Citation2003; Pinaya et al., Citation2016). Amazonia’s rural fishers become more food insecure in the wet season and increase their fishing effort in an attempt to compensate for lower CPUE (Tregidgo et al., Citation2020). In the high-water wet season, we find that fishers go fishing more often and avoid worse food insecurity (when controlling for income), whereas non-fishers do not. Alternatively, urban fishers (who we show are relatively vulnerable in socioeconomic terms) may fish more during the high-water season in order to compensate for other seasonal challenges, unrelated to changes in fishing CPUE. For instance, these households may be relatively exposed to high-water season issues with transport and economic activity, other rural livelihoods, or exposure to particular infectious diseases. Landings data from the eastern Amazon also suggests that urban fishers increase fishing effort in the high-water to maintain their catch levels (Hallwass et al., Citation2011).

We show urban fishers are generally food insecure in both seasons, whereas non-fishers are less food insecure in the dry season. Controlling for fish consumption, fishers did not experience a significant seasonal change in food insecurity. Our experiences in Maués (see above) show that provincial urban households which depend on buying fish (that is, non-fishers) are sensitive to local scarcity and higher prices during the wet season. Fishers’ wet season food insecurity risks therefore appear to be associated with how many fish they can catch themselves (that is, their fishing success), rather than on market prices. Nonetheless, because fishers are generally poor they are probably relatively dependent on informal employment, which is often seasonal. Hence, fisher households may still be sensitive to seasonal variation in the relative affordability of various foodstuffs.

Lower urban participation in fishing during the dry season is intriguing. Do some urban households temporarily stop fishing in the wet season because they consider it futile or unproductive, relative to other uses of their time? Further research is required to address this and other related questions on seasonality and urban fishing in Amazonia. Compared to rural fishers, perhaps they are able to substitute fish with other animal foods more easily during the wet season? Alternatively, maybe only committed, specialised urban fishers persist in the wet season, and hence the ‘opportunistic’ dry season-only fishers experience hunger when rivers and lakes are in flood. Certainly, many urban fisher households lack the time, knowledge, or resources (for example, large, expensive gill nets) to go further afield in search of lucrative Colossoma macropomum, which is normally caught in the wet season. Regardless, we know that river-level fluctuations shape fishing practices, and influence their efficiency (Almeida, McGrath, & Ruffino, Citation2001; Mcgrath, Pena, Cardoso, Almeida, & Benatti, Citation2011; Tregidgo et al., Citation2020). Hydrological seasonality and related consequences for fisher families and other consumers in central Amazonia may partly explain seasonal variation in prenatal growth and preterm birth odds (Chacón-Montalván et al., Citation2021).

4.5. Implications for future research

We hope this study motivates further research into small-scale urban fisheries in Amazonia and beyond. The nutritional dimensions of urban fishing and related fish consumption are under-researched, and our reliance on a metric of meals-containing-fish has limitations. Given social-economic and dietary changes in recent decades (Piperata et al., Citation2016) and inter-specific variation in fishes’ nutritional composition (Hicks et al., Citation2019), research could develop more detailed insights into quantities and species consumed, including body parts and cooking methods. Globally, the nutritional benefits of consuming fish are well-recognised (for example, Imhoff-Kunsch, Briggs, Goldenberg, & Ramakrishnan, Citation2012) but we need the evidence for developing nutrition-sensitive policies interventions. Examples include initiatives to reduce losses and develop fish drying and smoking techniques to concentrate nutrients (Thilsted et al., Citation2016).

Conflicts around territories and access rights are virtually ubiquitous in fisheries (for example, Jönsson, Citation2019), and it is important to understand power imbalances and vulnerabilities within Amazonia’s urban fishery. Institutions determine the rights of different user groups; some fishers can be systematically excluded from decision-making processes due to social marginalisation, linked to social class and political disempowerment (Smith et al., Citation2005). In Amazonia, it is unclear how (semi)-subsistence urban fishers may come into conflict with either commercial fishers or rural fishing communities. Amazonia’s social-ecological system is in a state of flux, including more frequent and severe floods and droughts, political instability, urban expansion, and specific changes to fisheries including territorial controls associated with nature conservation, rural development, and over-fishing (Castello et al., Citation2013). For example, Tregidgo, Barlow, Pompeu, de Almeida Rocha, and Parry (Citation2017) found severe depletion of C. macropomum ≤ 1000 km from Manaus and depletion around provincial towns yet evidence of stable multi-species catches. Work should examine the capacities of different groups of urban fishers to adapt to gradual and abrupt changes in this large, complex inland fishery (see Lowe et al., Citation2019).

4.6. Putting small-scale urban fisheries on the agenda

Our findings suggest there is a significant, yet largely overlooked small-scale urban fishery in Amazonia, much larger than professional fishers alone. We draw on our sample to estimate the size of the small-scale urban fishery in highly river-dependent urban centres in the Brazilian Amazon. Based on extrapolation, and adjusting for estimated 2019 population sizes (IBGE, 2019), we calculate that 84,210 households ± 10,868 SE in urban centres unconnected to the road network are fishers (Supplementary Material). Albeit many of these people would not self-identify as a fisher if asked their occupation (see above). Nonetheless, we estimate that the food security of around 470,735 urban residents in central Amazonia ± 60,753 SE may be dependent on a household member catching fish. Members of fisher households constitute 45 per cent ± 6 SE of the population of these riverine urban centres. The confidence intervals (SE) of our region-wide estimates are based on the lowest and highest levels of household participation in fishing from the four fieldwork towns. There is also urban-based small-scale fishing in urban centres that are partially or fully connected the road network but we do not attempt to estimate participation in those locations.

Irrespective of the exact numbers, institutions within and beyond the state must dedicate attention and resources to these urban fisheries in order to ensure long-term, equitable access to fish stocks. Contextual challenges include helping vulnerable urban households to overcome barriers to participation, including how poor households can maintain access to the river when new public housing projects are located far from the river-edge (Parry et al., Citation2019). Policy-makers face the complex task of balancing the needs, right to food, and ecological impacts of Amazonia’s rural, provincial urban and metropolitan populations, all of whom rely somewhat on eating fish.

5. Conclusions

We used household-level data from remote riverine Amazonian towns to understand the relationships between small-scale inland fishing and urban food security through the pathway of home consumption of caught fish. We found that the poorest and most food insecure households were the most likely to go fishing. Fishing typically provided participating households with monthly non-monetary income worth ≤ USD54, equivalent to around 12 per cent of mean monetary income. These households eat more fish, diversify their diets with low-quality processed meats, and rarely consume higher quality relatively expensive animal-based foods. Most urban fishers are non-professional and poor, and appear to use fishing as a strategy of last resort for attempting to protect against severe food insecurity. This study’s main contribution is showing that many poor, food insecure households in urban Amazonia use fishing as a coping strategy and appear to be highly dependent on eating the fish they catch. Relatively high levels of fish consumption and dietary dependency by severely food insecure households show how the equitable management of, and access to, natural resources are critical to supporting food security for Amazonia’s provincial urban poor. Policy-makers should therefore recognise the livelihoods dependencies of the provincial urban poor and their rights to food security and health when establishing rules and restrictions on access to fisheries.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to G Davies, B Taylor, P Diggle, M Cunha, J Orellana and N Filizola for input into project design and planning. We thank data collectors including M Tavares, N Migon, G Correia, G Fink, M Freiré, L M L Silva and R F R Costa. Christina Hicks provided useful advice during the development of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Code (in the R programming language; for data cleaning, processing, and analysis) and processed data can be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almeida, O. T., McGrath, D. G., & Ruffino, M. L. (2001). The commercial fisheries of the lower Amazon: An economic analysis. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 8(3), 253–269. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2400.2001.00234.x

- Barcellos, C., Feitosa, P., Damacena, G. N., & Andreazzi, M. A. (2010). Highways and outposts: Economic development and health threats in the central Brazilian Amazon region. International Journal Health Geographics, 9, 1.

- Batista, V. D. S., & Petrere Júnior, M. (2003). Characterization of the commercial fish production landed at Manaus, Amazonas State. Acta Amazonica, 33(1), 53–66. doi:10.1590/1809-4392200331066

- Battersby, J. (2017). MDGs to SDGs – new goals, same gaps: The continued absence of urban food security in the post-2015 global development agenda. African Geographical Review, 36(1), 115–129. doi:10.1080/19376812.2016.1208769

- Bayley, P. B., & Petrere, M., Jr. (1989). Amazon fisheries: Assessment methods, current status and management options. In W. Junk, P. Bayley, R. Sparks, & D. Dodge (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Large River Symposium (Vol. 106, pp. 385–398). Honey Harbour, Ontario: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources – Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

- Belik, W. (2015). A heterogeneidade e suas implicações para as políticas públicas no rural Brasileiro [Heterogeneity and its Implications for Public Policies in Rural Brazil]. RESR, 53(1), 9–30.

- Belton, B., & Thilsted, S. H. (2014). Fisheries in transition: Food and nutrition security implications for the global South. Global Food Security, 3(1), 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2013.10.001

- Béné, C. (2003). When fishery rhymes with poverty: A first step beyond the old paradigm on poverty in small-scale fisheries. World Development, 31(6), 949–975. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00045-7

- Béné, C. (2009). Are fishers poor or vulnerable? Assessing economic vulnerability in small-scale fishing communities. The Journal of Development Studies, 45(6), 911–933. doi:10.1080/00220380902807395

- Béné, C., Arthur, R., Norbury, H., Allison, E. H., Beveridge, M., Bush, S., … Williams, M. (2016). Contribution of fisheries and aquaculture to food security and poverty reduction: Assessing the current evidence. World Development, 79, 177–196. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.007

- Béné, C., Hersoug, B., & Allison, E. H. (2010). Not by rent alone: Analysing the pro-poor functions of small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Development Policy Review, 28(3), 325–358. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00486.x

- Béné, C., Mindjimba, K., Belal, E., & Jolley, T. (2001). Evaluating livelihood strategies and the role of inland fisheries in rural development and poverty alleviation: The case of the Yaéré floodplain in North Cameroon. In A. L. Shriver (Ed.), Proceedings of the Tenth Biennial Conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (pp. 1–13). Corvallis, Oregon: International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade - College of Agricultural Sciences - Oregon State University.

- Carignano Torres, P., Morsello, C., Orellana, J. D., Almeida, O., de Moraes, A., Chacón-Montalván, E. A., Pinto, M. A., Fink, M. G., Freire, M. P., & Parry, L. (2022). Wildmeat consumption and child health in Amazonia. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–14.

- Carter, C., & Garaway, C. (2014). Shifting tides, complex lives: The dynamics of fishing and tourism livelihoods on the Kenyan Coast. Society & Natural Resources, 27(6), 573–587. doi:10.1080/08941920.2013.842277

- Castello, L., McGrath, D. G., Hess, L. L., Coe, M. T., Lefebvre, P. A., Petry, P., … Arantes, C. C. (2013). The vulnerability of Amazon freshwater ecosystems. Conservation Letters, 6(4), 217–229. doi:10.1111/conl.12008

- Chacón-Montalván, E. A., Taylor, B. M., Cunha, M. G., Davies, G., Orellana, J. D. Y., & Parry, L. (2021). Rainfall variability and adverse birth outcomes in Amazonia. Nature Sustainability, 4(7), 583–594. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00684-9

- Christiaensen, L., & Kanbur, R. (2017). Secondary towns and poverty reduction: Refocusing the urbanization agenda. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 9(1), 405–419. doi:10.1146/annurev-resource-100516-053453

- Cooke, S. J., Allison, E. H., Beard, T. D., Arlinghaus, R., Arthington, A. H., Bartley, D. M., … Lorenzen, K. (2016). On the sustainability of inland fisheries: Finding a future for the forgotten. Ambio, 45(7), 753–764.

- Crush, J., & Caesar, M. (2014). City without choice: Urban food insecurity in Msunduzi. Urban Forum, 25(2), 165–175. doi:10.1007/s12132-014-9218-4

- Davies, G., Frausin, G., & Parry, L. (2017). Are there food deserts in rainforest cities? Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 107(4), 794–811. doi:10.1080/24694452.2016.1271307

- De Lima, A. C. B., Almeida, O., Pinedo-Vasquez, M., Lee, T. M., Rirvero, S., & Mansur, A. (2018). Resiliencia Urbana Y Amenazas Climáticas: Vulnerabilidad y Planificaciónde Adaptación Para Ciudades Pequeñas En El Delta y Estuario Del Rio Amazonas [Urban resilience and climatic threats: Vulnerability and adaptation planning for small cities in the delta and estuary of the amazon river]. Medio Ambiente Y Urbanización, 88(1), 95–122.

- de Oliveira Moraes, A., Schor, T., & Alves-Gomes, J. A. (2010). Relações de trabalho e transporte na pesca de bagres no rio Solimões – AM [Labor relations and transportation in catfish fishing in the Solimões River – Amazonas]. Novos Cadernos NAEA, 13, 1.

- Fabinyi, M., Dressler, W. H., & Pido, M. D. (2017). Fish, trade and food security: Moving beyond ‘availability’ discourse in marine conservation. Human Ecology, 45(2), 177–188. doi:10.1007/s10745-016-9874-1

- Fabré, N. N., & Barthem, R. B. (2005). O manejo da pesca dos grandes bagres migradores: Piramutaba e dourada no eixo Solimões-Amazonas. Manaus, Amazonas: ProVárzea. Ibama, Mma.

- Ferré, C., Ferreira, F. H., & Lanjouw, P. (2012). Is there a metropolitan bias? The relationship between poverty and city size in a selection of developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review, 26(3), 351–382. doi:10.1093/wber/lhs007

- Fiorella, K. J., Hickey, M. D., Salmen, C. R., Nagata, J. M., Mattah, B., Magerenge, R., … Fernald, L. H. (2014). Fishing for food? Analyzing links between fishing livelihoods and food security around Lake Victoria. Food Security, 6(6), 851–860. doi:10.1007/s12571-014-0393-x

- Frayne, B., Crush, J., & McLachlan, M. (2014). Urbanization, nutrition and development in Southern African cities. Food Security, 6(1), 101–112. doi:10.1007/s12571-013-0325-1

- Funge-Smith, S., & Bennett, A. (2019). A fresh look at inland fisheries and their role in food security and livelihoods. Fish and Fisheries, 20(6), 1176–1195. doi:10.1111/faf.12403

- Gomna, A., & Rana, K. (2007). Inter-household and intra-household patterns of fish and meat consumption in fishing communities in two states in Nigeria. The British Journal of Nutrition, 97(1), 145–152.

- Hallwass, G., Lopes, P., Juras, A., & Silvano, R. (2011). Fishing effort and catch composition of urban market and rural villages in Brazilian Amazon. Environmental Management, 47(2), 188–200.

- Hartje, R., Bühler, D., & Grote, U. (2016). Food security in rural Cambodia and fishing in the Mekong in the light of declining fish stocks. World Food Policy, 2, 5–31.

- Hartje, R., Bühler, D., & Grote, U. (2018). Eat your fish and sell it, too – Livelihood choices of small-scale fishers in rural Cambodia. Ecological Economics, 154, 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.07.002

- Heilpern, S. A., Fiorella, K., Cañas, C., Flecker, A. S., Moya, L., Naeem, S., … DeFries, R. (2021). Substitution of inland fisheries with aquaculture and chicken undermines human nutrition in the Peruvian Amazon. Nature Food, 2(3), 192–197. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00242-8

- Hicks, C. C., Cohen, P. J., Graham, N. A. J., Nash, K. L., Allison, E. H., D'Lima, C., … MacNeil, M. A. (2019). Harnessing global fisheries to tackle micronutrient deficiencies. Nature, 574(7776), 95–98.

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. (2014). Sustainable fisheries and aquaculture for food security and nutrition. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome, Italy: FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Imhoff-Kunsch, B., Briggs, V., Goldenberg, T., & Ramakrishnan, U. (2012). Effect of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intake during pregnancy on maternal, infant, and child health outcomes: A systematic review. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 26, 91–107. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01292.x

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. (2010a). Censo demografico da população [Population Census]. Brasilia, Brazil: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. (2010b). Pesquisa de orçamentos familiares 2008-2009: Despesas, rendimentos e condições de vida [Household Budget Census 2008–2009: Expenses, income and living standards]. Brasilia, Brazil: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica. (2019). Estimativas da população residente para os municípios e para as unidades da federação com data de referência em 1° de julho de 2019 [Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Estimates of the resident population for municipalities and federation units with a reference date of July 1, 2019]. Retrieved from https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9103-estimativas-de-populacao.html

- Isaac, V. J., & de Almeida, M. C. (2011). El Consumo del pescado en la Amazonía Brasileña (COPESCAALC Documento Ocasional No. 13) [Fish consumption in the Brazilian Amazon (COOPELSALC – Ocasional Document nr. 13)]. Rome, Italy: FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Jönsson, J. H. (2019). Overfishing, social problems, and ecosocial sustainability in Senegalese fishing communities. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3-4), 213–230. doi:10.1080/10705422.2019.1660290

- Junior, C. H. H. F., & Batista, V. D. S. (2019). Frota pesqueira comercial na Amazônia central: composição, origem, espécies exploradas e mercado [Commercial fishing fleet in the Central Amazon: composition, origin, exploited species and market]. Revista Agroecossistemas, 11, 146–168.

- Junk, W. J., Soares, M. G. M., & Bayley, P. B. (2007). Freshwater fishes of the Amazon River basin: Their biodiversity, fisheries, and habitats. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 10(2), 153–173. doi:10.1080/14634980701351023

- Kadfak, A. (2019). More than just fishing: The formation of livelihood strategies in an urban fishing community in Mangaluru, India. Journal of Development Studies, 56, 1–15.

- Kerm, P. V. (2007). Extreme incomes and the estimation of poverty and inequality indicators from EU-SILC (IRISS Working Paper Series.). Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg: Centre d’Etudes de Populations, de Pauvreté et de Politiques Socio-Economiques. Retrieved from https://liser.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/extreme-incomes-and-the-estimation-of-poverty-and-inequality-indi

- Kimani-Murage, E. W., Schofield, L., Wekesah, F., Mohamed, S., Mberu, B., Ettarh, R., … Ezeh, A. (2014). Vulnerability to food insecurity in urban slums: Experiences from Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 91(6), 1098–1113. doi:10.1007/s11524-014-9894-3

- Kolding, J., Béné, C., & Bavinck, M. (2014). Small-scale fisheries: Importance, vulnerability and deficient knowledge. In S. Garcia, J. Rice, & A. Charles (Eds.), Governance of marine fisheries and biodiversity conservation: Interaction and coevolution (pp. 317–331). Sussex, UK: Willey-Blackwell.

- Lee, G. O., Surkan, P. J., Zelner, J., Olórtegui, M. P., Yori, P. P., Ambikapathi, R., … Kosek, M. N. (2018). Social connectedness is associated with food security among peri-urban Peruvian Amazonian communities. SSM - Population Health, 4, 254–262. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.02.004

- Lorenzen, K., Almeida, O., & Azevedo, C. (2006). Interações entre a pesca comercial e a de subsistência no Baixo Amazonas: Desenvolvendo um modelo bioeconômico [Interactions between commercial and subsistence fisheries in the Lower Amazon: Developing a bioeconomic model]. In O. Almeida (Ed.), Manejo de pesca na Amazônia (pp. 73–94). Peirópolis, Brazil.

- Loring, P. A., Fazzino, D. V., Agapito, M., Chuenpagdee, R., Gannon, G., & Isaacs, M. (2019). Fish and food security in small-scale fisheries. In R. Chuenpagdee & S. Jentoft (Eds.), Transdisciplinarity for small-scale fisheries governance (pp. 55–73). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Lowe, B. S., Jacobson, S. K., Anold, H., Mbonde, A. S., & O’Reilly, C. M. (2019). Adapting to change in inland fisheries: Analysis from Lake Tanganyika, East Africa. Regional Environmental Change, 19(6), 1765–1776. doi:10.1007/s10113-019-01516-5

- Lynch, A. J., Bartley, D. M., Beard, T. D., Cowx, I. G., Funge-Smith, S., Taylor, W. W., & Cooke, S. J. (2020). Examining progress towards achieving the ten steps of the rome declaration on responsible inland fisheries. Fish and Fisheries, 21(1), 190–203. doi:10.1111/faf.12410

- Lynch, A. J., Cooke, S. J., Deines, A. M., Bower, S. D., Bunnell, D. B., Cowx, I. G., … Riley, B. (2016). The social, economic, and environmental importance of inland fish and fisheries. Environmental Reviews, 24(2), 115–121. doi:10.1139/er-2015-0064

- Lynch, A. J., Cowx, I., Fluet-Chouinard, E., Glaser, S., Phang, S., Beard, T., … Claussen, J. (2017). Inland fisheries–invisible but integral to the UN Sustainable Development Agenda for ending poverty by 2030. Global Environmental Change, 47, 167–173. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.10.005

- Mansur, A. V., Brondízio, E. S., Roy, S., Hetrick, S., Vogt, N. D., & Newton, A. (2016). An assessment of urban vulnerability in the Amazon Delta and Estuary: A multi-criterion index of flood exposure, socio-economic conditions and infrastructure. Sustainability Science, 11, 1–19.

- Mcgrath, D. G., Pena, S., Cardoso, A., Almeida, O., & Benatti, J. H. (2011). Integrating comanagement and land tenure policies for the sustainable management of the lower Amazon floodplain. In M. Pinedo-Vasquez, M. L. Ruffino, C. Padoch, & E. S. Brondízio (Eds.), The Amazon varzea: The decade past and the decade ahead (pp. 119–135). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Moradi, S., Mirzababaei, A., Mohammadi, H., Moosavian, S. P., Arab, A., Jannat, B., & Mirzaei, K. (2019). Food insecurity and the risk of undernutrition complications among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition, 62, 52–60.

- Murrieta, R. S. S., & Dufour, D. L. (2004). Fish and farinha: Protein and energy consumption in Amazonian rural communities on Ituqui Island. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 43(3), 231–255. doi:10.1080/03670240490447550

- Nasielski, J., Kc, K. B., Johnstone, G., & Baran, E. (2016). When is a fisher (not) a fisher? Factors that influence the decision to report fishing as an occupation in rural Cambodia. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 23(6), 478–488. doi:10.1111/fme.12187

- Padoch, C., Brondízio, E., Costa, S., Pinedo-Vasquez, M., Sears, R. R., & Siqueira, A. (2008). Urban forest and rural cities: Multi-sited households, consumption patterns, and forest resources in Amazonia. Ecology and Society, 13(2). Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art2/

- Parry, L., Barlow, J., & Pereira, H. (2014). Wildlife harvest and consumption in Amazonia’s urbanized wilderness. Conservation Letters, 7(6), 565–574. doi:10.1111/conl.12151

- Parry, L., Davies, G., Almeida, O., Frausin, G., de Moraés, A., Rivero, S., … Torres, P. (2018). Social vulnerability to climatic shocks is shaped by urban accessibility. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(1), 125–143. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1325726

- Parry, L., Radel, C., Adamo, S. B., Clark, N., Counterman, M., Flores-Yeffal, N., … Vargo, J. (2019). The (in)visible health risks of climate change. Social Science & Medicine, 241, 112448. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112448

- Pedrosa, B. M. J., Lira, L., & Maia, A. L. S. (2018). Pescadores urbanos da zona costeira do estado de Pernambuco, Brasil [Urban fishermen in the coastal zone of the state of Pernambuco, Brazil]. Boletim Do Instituto de Pesca, 39, 93–106.

- Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios. (2013). Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios (PNAD)—Segurança Alimentar [National household sample survey]. Brasilia, Brazil: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica - IBGE.

- Pinaya, W. H. D., Lobon-Cervia, F. J., Pita, P., de Souza, R. B., Freire, J., & Isaac, V. J. (2016). Multispecies fisheries in the lower Amazon river and its relationship with the regional and global climate variability. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157050.

- Piperata, B. A., McSweeney, K., & Murrieta, R. S. (2016). Conditional cash transfers, food security, and health: Biocultural insights for poverty-alleviation policy from the Brazilian Amazon. Current Anthropology, 57(6), 806–826. doi:10.1086/688912

- Rocha, Y. R. D., Aguiar, J. P. L., Marinho, H. A., Shrimpton, R., Rocha, Y. R. D., … Shrimpton, R. (1982). Aspectos nutritivos de alguns peixes da Amazônia [Nutritional aspects of some Amazonian fishes]. Acta Amazonica, 12(4), 787–794. doi:10.1590/1809-43921982124787

- Ruel, M. T., Garrett, J., Yosef, S., & Olivier, M. (2017). Urbanization, food security and nutrition. In S. de Pee, D. Taren, & M. W. Bloem (Eds.), Nutrition and health in a developing world (pp. 705–735). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Silva, H. (2009). Socio-ecology of health and disease: The effects of invisibility on the caboclo populations of the Amazon. In C. Adams, R. Murrieta, W. Neves, & M. Harris (Eds.), Amazon peasant societies in a changing environment (pp. 307–333). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Springer.

- Smith, L. E. D., Khoa, S. N., & Lorenzen, K. (2005). Livelihood functions of inland fisheries: Policy implications in developing countries. Water Policy, 7(4), 359–383. doi:10.2166/wp.2005.0023

- Tacoli, C. (2017). Food (in)security in rapidly urbanising, low-income contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1554. doi:10.3390/ijerph14121554

- Tallman, P. S., Riley-Powell, A. R., Schwarz, L., Salmón-Mulanovich, G., Southgate, T., Pace, C., … Lee, G. O. (2020). Ecosyndemics: The potential synergistic health impacts of highways and dams in the Amazon. Social Science & Medicine, 295, 1–10.

- Thilsted, S. H., Thorne-Lyman, A., Webb, P., Bogard, J. R., Subasinghe, R., Phillips, M. J., & Allison, E. H. (2016). Sustaining healthy diets: The role of capture fisheries and aquaculture for improving nutrition in the post-2015 era. Food Policy, 61, 126–131. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.02.005

- Tregidgo, D. J., Barlow, J., Pompeu, P. S., de Almeida Rocha, M., & Parry, L. (2017). Rainforest metropolis casts 1,000-km defaunation shadow. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 8655–8659.

- Tregidgo, D. J., Barlow, J., Pompeu, P. S., & Parry, L. (2020). Tough fishing and severe seasonal food insecurity in Amazonian flooded forests. People and Nature, 2(2), 468–482. doi:10.1002/pan3.10086

- van Vliet, N., Quiceno-Mesa, M. P., Cruz-Antia, D., Tellez, L., Martins, C., Haiden, E., & Oliveira, M. R. (2015). From fish and bushmeat to chicken nuggets: The nutrition transition in a continuum from rural to urban settings in the Colombian Amazon region. Ethnobiology and Conservation, 4, 1–12.

- Youn, S.-J., Taylor, W. W., Lynch, A. J., Cowx, I. G., Beard, T. D., Bartley, D., & Wu, F. (2014). Inland capture fishery contributions to global food security and threats to their future. Global Food Security, 3(3-4), 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2014.09.005