Abstract

Disasters are a primary influence in the global development landscape given their unequal impacts across society and calls for transformative change in their aftermath. Recovering from disasters is one component of development that is coming under scrutiny. This is especially so in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, whose scale, scope, and cascading effects mean that the uncertain prospects for recovery will be complicated and endure long term. COVID-19 has forced a reappraisal of what recovery encompasses, who it is for, and how it can better enable preparedness for future disasters. Drawing upon interviews with a global community of experts specializing in different areas of disaster governance, this paper focuses on the lessons emerging for recovery-related theory and practice deriving from the pandemic. We elaborate a multi-dimensional framework to support those working on local recovery planning within communities and operating across different sectors. The framework captures the interconnected issues across six principal domains—communities, economic, infrastructure, environment, health, and governance—representing key impact areas around which strategies and multifaceted actions can be developed. We suggest a three-step process using a systems approach to develop a recovery strategy that operationalizes the framework and addresses the complexity of long-term recovery for development.

1. Introduction

Disasters are a primary influence on changes in the global development landscape. The United Nation’s (UN) Sustainable Development Goals reflect international commitments to ‘achieve a better and more sustainable future for all’ through actions, such as reducing losses from disasters and reducing societal vulnerabilities to climate-related hazards (Nohrstedt, Mazzoleni, Parker, & Di Baldassarre, Citation2021). Under the UN’s 2030 Agenda, a decade of action was envisaged to address climate change, poverty, and foster peaceful, inclusive societies. Five years after this agenda was established in 2015, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. According to the Inter-Agency on Financing for Development (UNIAFT), the pandemic threatens to create a ‘lost decade for development’ should the divergent trajectories of rich and lower-income countries continue, for example, in the absence of vaccine solidarity and economic reforms (UNIAFT, Citation2021). Considering such claims, the pandemic has intensified scrutiny of narrow economic logic and amplified calls for a reworking of conventional approaches to development (Leach, MacGregor, Scoones, & Wilkinson, Citation2021).

One component of development under scrutiny is the techniques, strategies, and policies through which countries seek long-term recovery from COVID-19. The pandemic’s effects on different sectors of society mean that recovery is complicated, requiring resourcing and enduring multi-level coordination across multisector stakeholder groups. For example, the ‘long shadow’ of COVID-19 is forecast to last over a decade, during which its deeply uneven impacts will amplify (British Academy, Citation2021). What recovery encompasses given the challenges, its key constituent parts, and how it can be governed and resourced, are critical questions for local decision-makers worldwide. A question of central concern in this paper is therefore on what a practice-oriented recovery framework looks like?

Recognizing post-disaster recovery as constitutive of development, we elaborate a multi-dimensional framework to support those responsible for recovery planning for any type of disaster. We argue that such a framework has much to learn from COVID-19 experiences which exposed gaps in understanding disaster recovery. For example, much research has focused on the recovery prospects of different sectors, organizations, and communities (e.g. McCartney, Pinto, & Liu, Citation2021), or calls for societal transformations in its aftermath (e.g. Gupta et al., Citation2021). Less attention has centered on recovery planning to enhance preparedness for future systemic shocks, especially governance, and the need to better integrate pandemic planning with recovery planning for other hazards. Existing public health guidance on recovery from pandemics does not fully accommodate their cascading effects on other interconnected sectors beyond the social determinants of health and restarting normal services (Schoch-Spana, Ravi, & Martin, Citation2022). Healthcare provision is usually pressured when disasters hit, so their position in any recovery framework is not particular to health-led disasters, like pandemics. Conversely, pandemics are poorly incorporated into planning and thinking on disaster recovery more broadly (e.g. Kennedy, Gonick, & Errett, Citation2021).

Thus, we elaborate a multi-dimensional recovery framework that builds upon lessons emerging for recovery-related theory and practice deriving from COVID-19. Our research draws upon ethnography and interviews undertaken in the early months of the pandemic with experts across twenty-one countries. Our active engagement during this febrile period advising international policy-practice partners generated insights on the need to overcome narrow approaches to recovery to encompass more than health and economic impacts. The ethnography stimulated initial thoughts on research needs, research questions, and early answers – and the interviews sought structured insight from a wider, international expert base to inform comprehensive answers. At that time, much of the available resources of governments were committed to response but planning for recovery in the pandemic’s wake had already been initiated in many places.

The recovery challenges anticipated following COVID-19 is clearly significant for our recovery framework. Indeed, the pandemic’s scale, scope, cascading effects on people, places, and processes, together with uncertain temporal boundaries, underpin its relevancy to other disaster types. To expose the array of weaknesses and vulnerabilities that enmesh global systems and local societies, COVID-19 is consequential for informing alternative approaches to recovery that encourage more inclusive development.

How to operationalize the recovery framework is of wider significance given the limitations of current approaches to disaster recovery that are less suited to address the complex, systemic, and intensifying risks in a connected and globalized world. Further, and cognizant of debates at the intersection between disaster and development studies (e.g. Schipper & Pelling, Citation2006), the implementation of this framework is embedded in a process of co-production with local communities to reflect their immediate and evolving circumstances. We outline a three-step process that is responsive to local cultures and conditions when developing a strategy that operationalizes the framework. This process can support recovery planning in a range of contexts in the global North and South.

This paper proceeds as follows. We first outline how recovery is understood and contested in theory and practice. Then the methodology is described in how, through analysis, the recovery framework was built. Our discussion follows, exploring the framework’s prospective practical application through a systemic approach to forming a recovery strategy, as well as designing a process to implement the strategy.

2. Post-disaster recovery for development

Our focus in this paper is on the process of recovery, which, following Sou, Shaw, and Aponte-Gonzalez (Citation2021) encapsulates:

The sustainable restoration or improvement of livelihoods and health, as well as economic, physical, social, cultural, and environmental assets, systems, and activities, of a disaster-affected community or society, which reduces future disaster risk and tackles underlying causes of risk through transformational renewal initiatives.

What recovery means, its purpose, timeframes, components, and governance, are actively debated, with scholarly conceptualizations tending towards approaches cognizant of its contingencies, inequalities, and variegations (Sou et al., Citation2021). As a critical starting point towards elaborating our framework, this section considers how recovery is understood in development policy-practice and research before outlining how COVID-19 has forced a reappraisal of the fundamentals.

2.1. Purposes and dimensions of recovery

Much research has sought to evaluate the success of government attempts to enact recovery (e.g. Ingram, Franco, Rumbaitis-del Rio, & Khazai, Citation2006). When done effectively and equitably, recovery generates positive outcomes for disaster-affected communities enhancing their preparedness to avoid or reduce future risks (UNISDR, Citation2015). Recovery’s purpose in the short-term is largely transactional, aiming, for instance, to reinstate damaged infrastructure and maintain the functioning of utilities and essential services. However, recovery is also enfolded within more transformative long-term agendas that take longer to accomplish – what has been called ‘renewal’ (Sou et al., Citation2021). Internationally, the latter intent is captured within the UN’s 2015 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and its much-invoked call to ‘Build Back Better’. Despite being the subject of critique (e.g. Sheller, Citation2020), the mobilization of this concept is prominent within the politics of COVID-19 recovery globally.

Recovery actions should start during, and then eclipse, the response to mitigate and lessen the impact of crises. Ideally, pre-disaster plans co-produced with local communities pro-actively establish the vision and principles for recovery in anticipation of future disasters, supported by flexible policies and proposed actions, a robust evidence base, monitoring, and evaluation frameworks (Berke, Cooper, Aminto, Grabich, & Horney, Citation2014). In practice, pro-active recovery planning is often absent or deficient, increasing the likelihood of outcomes that do not meet community needs; a key insight from post-tsunami Sri Lanka (Ingram et al., Citation2006). Given its complexities, the process may extend over years/decades, with the timeframe contingent on multiple factors including the spread and severity of disaster impacts, and the scale of resources made available (Davis & Alexander, Citation2015). The pathways and temporalities of recovery for places, organizations, households, and individuals are always heterogeneous.

Recovery is a difficult disaster management phase to get right. Typically, its ‘time-compressed’ character, when the short-term restoration of infrastructure and essential services must happen faster than during normal times (Olshansky, Hopkins, & Johnson, Citation2012), generates political pressure for instantaneous decisions that may foreclose equitable social change longer-term (Chandrasekhar, Zhang, & Xiao, Citation2014). In particular, the needs of vulnerable communities often go unmet, with strains on housing availability one of the domains where pre-existing inequities are often exacerbated in post-disaster contexts (Peacock, Van Zandt, Zhang, & Highfield, Citation2014). Thus, those most exposed to the effects of hazards like Hurricane Katrina may experience a ‘second-order disaster’, especially during a prolonged recovery, creating new or reinforcing previous vulnerabilities (Pescaroli & Alexander, Citation2018).

Critiques probe how the effectiveness of recovery is contingent on how it accommodates differences within and among communities. This includes research on marginalized and understudied groups, through the lens of gender, race, class, and ethnicity, among others, particularly intersecting with questions of social equity (Bolin & Kurtz, Citation2018). Research demonstrates the entanglement of recovery practices within processes that evidence the continuing effects of colonialism in the Caribbean, for example (Bonilla, Citation2020). Simultaneously, the framing of recovery (in terms of the ends that it pursues) has inhibited its potential for engendering transformation (Seale-Feldman, Citation2020).

How recovery is framed and enacted for inclusive developmental and exclusionary purposes, varies across communities. A growing literature explores the limitations of the ‘build back better’ approach to meet raised expectations post-disaster (Fernandez & Ahmed, Citation2019). Thus, thinking towards recovery demands attention to power relations, equity, and the global-local politics underpinning disasters. For example, ‘disaster capitalism’ is a prominent framing referring to the exploitation of disasters by powerful actors for enrichment and accumulation of power, often at the expense of communities (Klein, Citation2008). This takes many forms, including processes of financialization in places like Nepal where difficult topographies constrain the possibilities for land-based appropriations (Paudel, Rankin, & Le Billon, Citation2020).

Recovery also creates space for transformative action that enhances societal resilience to future shocks. Amid the challenging circumstances of disasters, possibilities exist for localized resistance to exploitative practices, the creation of support networks, and change through activating alternative ways of organizing society (Cretney, Citation2017). However, as Leach et al. (Citation2021) discuss, the severity of COVID-19’s impacts underscore the need for development models oriented towards solidarity, including new ways of policymaking in the face of increasingly complex and ‘unruly’ challenges. Novel thinking and doing are required across the global North and South. Failing to adopt an inclusive development approach to post-pandemic recovery, for Gupta et al. (Citation2021), risks exacerbating the vulnerability of poorer populations and threatens the UN’s 2030 Agenda.

2.2. Recovery frameworks post-COVID-19

The academic literature and policy context illustrates how recovery is situated within broader conditions that shape development trajectories. For example, frameworks are important tools supporting those working on recovery, whether in articulating a vision, prioritizing actions following impact assessments, or guiding the monitoring and evaluation of recovery activities (GFDRR, Citation2015). Thematically speaking, variance is apparent across countries in the broad categorization of recovery activities within key national disaster management policies, particularly in the prominence afforded to and effectiveness of health-related measures. Although the US Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Disaster Recovery Framework includes health/social services as a core capability domain, it is constrained in how it deals with the impact of pandemics (Barnett, Rosenblum, Strauss-Riggs, & Kirsch, Citation2020), and state disaster recovery plans are limited in addressing healthcare needs (Kennedy et al., Citation2021).

Pronounced scholarly interest in health-led disasters in the development and disaster literature has only coincided with COVID-19. The inadequate incorporation of pandemics within thinking on recovery is evident when comparing post-disaster recovery-oriented frameworks. A selection from the literature is shown in , which illustrates the principal categories used to represent recovery domains. These frameworks are diverse in their purposes and how they address recovery. For example, several frameworks are theoretically grounded and provide insights into concepts including adaptive capacity and community resilience (Cutter, Burton, & Emrich, Citation2010; Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, Citation2008). Others are practice-based and action-oriented, identifying barriers that impede recovery (Rouhanizadeh, Kermanshachi, & Nipa, Citation2020), and developing indicators to monitor coping post-disaster (Horney, Dwyer, Aminto, Berke, & Smith, Citation2017). Whereas several frameworks aspire to an ‘all-hazards’ approach, only one was explicitly elaborated in the context of pandemics (Boaden et al., Citation2020).

Table 1. A selection of recovery frameworks within academic literature

While different disasters require distinct types of recovery, COVID-19 exposed a failure to accommodate pandemics on two registers. First, health provision has not been featured as a principal category in recovery frameworks. This absence is problematic as, amid pandemics, the speed and success of recovery are dependent on public health measures. That underlying health conditions are a mortality risk, and poor mental health is anticipated as an enduring impact, amplifies the long-term imperative to tackle the social determinants of ill-health.

The Sendai Framework points to the importance of health in recovery from all disasters (not just pandemics) as the demands on healthcare services are commonplace. For example, the long-term psycho-social needs of those affected by the 2011 Fukushima ‘triple disaster’ are significant (Hasegawa, Ohira, Maeda, Yasumura, & Tanigawa, Citation2016). However, implementation challenges with Sendai are evident over the integration of health indicators, data collection, and reporting guidelines (Maini, Clarke, Blanchard, & Murray, Citation2017), while Djalante, Shaw, and DeWit (Citation2020) call for improved incorporation of health-related issues in disaster risk governance. Thus, better foregrounding of health within local recovery frameworks, particularly in poorer places with weaker public healthcare systems, is fundamental.

Second, where health has been considered it has not been fully integrated with the recovery of other sectors affected by pandemics. Existing frameworks are neither sufficiently expansive nor precise to embrace the array of recovery challenges raised by COVID-19. Even when the principal domains are as applicable to pandemics as other disaster types like hurricanes, a distinct set of underlying concerns is present. When it comes to housing issues, for instance, recovery challenges do not revolve around repairing physically damaged properties or returning a displaced population – they focus more on chronic homelessness. Pandemic-specific frameworks in medical and health sciences, although alert to the importance of factors that shape the social determinants of health (e.g. the economy, and infrastructure), have not paid sufficient attention to the cascading effects of pandemics on the recovery of other sectors (e.g. social distancing impacting public transport provision and use) (Schoch-Spana, Citation2020; Schoch-Spana et al., Citation2022). Better integrating pandemic planning with recovery planning for other hazards is required.

2.3. Disasters as complex challenges for governance and a recovery strategy

Apart from engaging with this policy context to locate gaps in current frameworks, our work is inspired by current thinking concerning the complexity of framework implementation. Critical to the implementation of recovery frameworks is their operationalization via the development of a feasible strategy. For example, Ingram et al. (Citation2006) argue that long-term recovery (e.g. renewal initiatives) should be designed and delivered as a separate project given its aims and complexity in addressing vulnerabilities and building new capabilities. Initiatives may flounder when simplistic transitions are made from short-term fixes into complex plans using the same approach, governance, and actors (Blackman, Nakanishi, Benson, & Freyens, Citation2016), which cannot deal with the expanded scope. Moreover, as Raju and Becker (Citation2013) discuss, although multi-agency coordination is critical, its scope is often limited to information sharing and dissipates once attention shifts from the disaster response.

A top-down governance approach also fails in dealing with complexity and can lead to community exclusion, tension, and poor outcomes (Blackman, Nakanishi, & Benson, Citation2017). This manifests, for example, in recovery programs overlooking the cultural requirements of communities in earthquake-stricken rural areas when reconstructing housing (Alipour et al., Citation2015). However, drawing from a small but growing literature within disaster management and development studies, systems thinking methodologies are specifically designed for systems operating in complex settings (Simonović, Citation2011). These methodologies and models can guide practitioners in the co-production of a recovery strategy that is responsive to and shaped by local needs (Eden, Citation1992). This is also informed by their application to the complexities of disasters, including in evaluating risk reduction programs (Shaw, Fattoum, Moreno, & Bealt, Citation2020).

3. Methodology

To explore recovery for development, a qualitative methodology was employed comprising semi-structured interviews. The ‘reflection-in-action’ enabled by this approach is valuable to make sense of unfolding situations and shift from reactive to proactive approaches to pre- and post-disaster recovery.

3.1. Data collection

Interviews were broadly structured around the issue of what a recovery framework should include. Interviews were conducted with a community of experts (n = 66) across five continents and 21 countries between April and July 2020 – see the Supplementary Material for interviewee breakdown. Although early in COVID-19 for some countries, to reiterate from above, recovery planning optimally begins as soon as disasters strike, with pre-disaster activities to enhance preparedness also indicative of good practice (e.g. co-production of community risk registers). Given working from home policies, interviews were conducted online and recorded with consent.

Respondents were purposefully selected for their expertise and ability to elucidate on COVID-19 recovery (Schutt, Citation2006). Further factors included ensuring geographic spread across the global North and South, as well as embeddedness within countries that have long histories of disasters, including pandemics, and/or are globally recognized for the effectiveness of their recovery practices. Recruited via the project team’s international networks, respondents encompass policymakers and practitioners working within central and local government, including resilience officers, emergency planners, and health officials. Others are currently or were recently employed within the private sector, civil society organizations, or academia. Most were engaged with pandemic response and recovery, while a small cohort offered insights from their experiential learning from past crises. Eliciting multi-disciplinary perspectives from diverse communities of practice and place is vital to informing disaster recovery processes (Jordan & Javernick-Will, Citation2014).

The interview data was complemented by ethnographic fieldwork principally consisting of regular online meetings with multiple local authorities and partner organizations, including in north and south America (Canada, Chile), Europe (UK), and the Middle East (Palestine). The knowledge generated through these interactions was mutually co-constitutive, with members of the research team providing expert insights and emergent lessons from elsewhere on recovery. In turn, the research team was afforded access to the organizations concerned as they planned recovery.

3.2. Data analysis

Cognitive mapping was used to represent, analyze, and synthesize the interview data. As an action-oriented technique suited to establishing a ‘systemic view’ of an issue, this process generates maps that encompass key ideas conveyed within qualitative data (Ackermann, Howick, Quigley, Walls, & Houghton, Citation2014). Ideas are represented diagrammatically as nodes signifying higher-level themes enmeshed within a network of actions, implications, or supporting information, all interlinked via arrows indicating the directionality of the argumentation (Shaw, Smith, & Scully, Citation2017). The composite map generated facilitates an iterative-inductive analysis and identification of themes through open coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). To ensure consistency, and therefore enhancing the dependability of the analysis. The mapping and coding process was structured into three parts.

The first part consisted of a calibration exercise involving the listening to and mapping of several interviews by the project team individually, with a comparative review of the maps at the end to ensure consistency. Three mapping levels were applied in descending order: (1) higher-level nodes relating to outcomes/goal-oriented concepts and broad areas for action (e.g. protecting vulnerable people), (2) mid-level nodes relating to underpinning actions or limitations/challenges (e.g. supporting people to stay in their homes to prevent infection), and (3) low-level nodes providing supporting detail or contextual/procedural information and examples illustrating the nodes (e.g. volunteers delivering food to the elderly).

The second involved dividing up and mapping the remaining interviews by individual team members. Regular team meetings aided discussion, comparison, and consensus-building on the development of the mapping trees during the analysis. The third part built a composite map by synthesizing all the individual interview maps. Theme clusters were identified from the composite map under six domains which inform the framework in .

Table 2. Multi-dimensional recovery framework for development

The ethnographic insights accumulated by team members enabled triangulation and sense-checking to ensure that the data aligned with lived realities. The emergent framework was presented within multiple policy-practice fora online, including internationally (e.g. via Resilient Cities Network), nationally (through a UK cross-government forum), and locally (working with partner local authorities in Chile, Canada, UK, and Palestine). These provided opportunities for feedback, validation, and ‘practice-testing’.

4. Findings

Our framework consists of six interdependent and overlapping domains (communities; economy; infrastructure; health; environment; governance) comprised of sub-categories that describe recovery action areas. While important for identifying discrete ways in which recovery should be achieved, matters arising through the research frequently cut across domains (e.g. introduction of pop-up cycle lanes helped achieve public health measures like physical distancing, while simultaneously relating to other sub-categories under Infrastructure, Environment, and Governance). Simply, five of the domains represent ‘what’ and ‘who’ is being recovered in terms of people, places, and processes, whereas governance is primarily an enabler about the ‘how to’.

Each domain includes sub-categories – see – which outline action areas and are illustrated below using interviewee quotations (identified by respondent numbers, e.g. R47). The sub-category headings are underlined below, to show their inter-connectedness to each other and the principal domain.

Perspectives are included below from those working in and/or focused on high-, middle- and lower-income countries, recognizing that COVID-19 is a ‘universal concern’ that exposed inequalities worldwide (Leach et al., Citation2021). Although the framework applies to countries across the global North and South, we recognize that the unique context of different communities should inform what each sub-themes means and how it is interpreted. This encompasses, for example, the design of recovery actions to address the impacts assessed and the creation of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Further, we acknowledge that additional considerations may be required in places experiencing acute intersecting and compound disasters including conflict (Hilhorst & Mena, Citation2021).

4.1. Communities

Recovering communities and taking a developmental approach where ‘empathy for people’ (R2) is central to recovery prevailed across the interviews. Among the recovery challenges identified is the need to alleviate the negative impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable people, including low-income families and those experiencing mental health problems. Concerns were voiced over the recovery implications arising from difficult to monitor public protection issues exacerbated during the lockdown. For example, school closures, ‘not being able to carry out routine checks’, and ‘face-to-face visits’ meant that dealing with potential instances of ‘neglect and abuse’ became more challenging for social services (R58). The full extent of the ‘secondary impacts’ on such concerns as child welfare and domestic abuse are only anticipated to emerge longer term.

The provision during recovery of ongoing welfare supports and emergency housing was deemed by several interviewees as important for migrants and refugees. Although measures were taken early in Portugal to ‘legalize’ the status of certain immigrants, therefore facilitating access to healthcare and social welfare supports, these did not apply to all (R29). Meanwhile, in the UK, asylum seekers in mass accommodation are among the identified groups in housing need most ‘at risk’ of eviction, homelessness, and rough sleeping (R47). However, uncertainties abound over the full impact of the pandemic on the demand dynamics for emergency housing, particularly given groups rendered newly vulnerable by loss of income and the (then) unclear endpoint of the ‘evictions ban’ on private landlords.

Sustaining volunteering and enhancing opportunities for community participation in recovery are two action areas where there has been increased civic engagement. Interviewees talked of an upsurge in humanitarian assistance from individuals, communities, and mutual aid groups, in what one Malaysian interviewee characterized as the sense that ‘everyone is expected to play a role in fighting the virus’ (R50). In Argentina, for instance, ‘spontaneous volunteers’ helped organize community kitchens for vulnerable people (R33). However, evidence from other disasters suggests that voluntary recovery assistance often dissipates and is unevenly distributed over time (Sou et al., Citation2021). Translating this elevated public interest into participatory policy and decision-making is aspired to by several interviewees relating to inclusivity and ownership of the recovery process.

Investing in education and skills during recovery is critical, particularly given that young people, the unskilled, and immigrants have been particularly impacted during COVID-19. Changing work practices, people leaving the workforce, and economic restructuring, support the need for proactive skills agendas and bolstering areas like ‘vocational training’ (R41). Assisting in restoring the cultural life of communities following lockdowns, for example, by creating safe ‘spaces for socializing and meeting people’, is viewed as a significant recovery activity (R40). Sociocultural needs and concerns are frequently marginalized in disaster contexts (Sou, Citation2019).

4.2. Economy

The pandemic provoked discussion of the development of new economic strategies for recovery, first, evident in relation to tourism. For example, in Iceland, ‘bubble tourism’ and the effectiveness of strategies employed elsewhere are informing thinking (R32). Second, the digital acceleration towards remote working, for some, meaning that organizations may no longer require a building ‘in one central location… to operate effectively and efficiently’ (R41), will have implications for how they function, and for local economies. Finally, innovation must continue to sustain organizations during recovery, albeit this capacity is shaped by multiple factors and many businesses have ‘not been able to reinvent’ (R51).

With much of the world forecasted at the outset of the pandemic to face an ‘ecosystem of unemployment’ (R40), public sector support mechanisms are vital to business regeneration/rejuvenation. The pandemic’s impacts, and recovery prospects for different sectors, organizations, and places, are variable across multiple dimensions. In short, ‘some [businesses] are going to be able to recover fairly quickly, others are not’ (R51), while some ‘will vanish’ (R10). Small and medium-sized enterprises ‘starving for cash to pay… employees’ (R31) are especially vulnerable to ongoing disruption. Such public supports range from expediting construction projects to funding ‘the reconfiguring of layouts’ to facilitate small business reopening (R58). In Portugal, reactivating ‘employment support services’ set-up after the 2008 financial crisis, but since much reduced, was anticipated considering the economic predictions (R29).

The recovery of the voluntary, community, and social enterprise sector presents challenges despite the upsurge in volunteering and mutual aid experienced in many places during the early months of the pandemic. The finances/fundraising of many charities have been severely disrupted. Further, the work of many NGOs in the Global South flipped from longer-term developmental activities to short-term emergency response, making it more difficult to engage in reflection and ‘think forwards’ towards pandemic recovery (R49). An anticipated lessening of international funding for civil society initiatives in low-income counties will exacerbate the challenges.

Pandemic recovery must also confront many concerns for labor and the workforce. Consistent with the Communities domain, a ‘people-centered’ approach to economic recovery was expected by interviewees. A facet of this relating to the changing nature of work was expressed by one who hoped that employers would ‘engage better with their workforce’ around issues like flexible working, childcare support, and employee well-being (R31). Relatedly, another interviewee wished for greater emphasis on the ‘social and economic value of key workers’, especially those within UK health and social care who are often poorly paid migrants from whom much is expected (R7).

Personal finances were expected to remain fragile during recovery. For example, whether temporary furlough schemes represent a ‘recession waiting room’, was asked by one private sector consultant (R51). How quickly governments phase out wage and welfare support and provide ‘pathways’ to employment will have significant implications, particularly for ‘casual workers’ who lost their jobs and whose ‘reserves have been used up’ (R13). Peoples’ financial vulnerability influenced their capacity to ‘bounce back individually’ (R48). The livelihoods of those working in the informal economy are precarious, especially given the limited access of many to financial ‘safety nets’, and the wider pandemic impact on their social networks (Gupta et al., Citation2021).

4.3. Infrastructure

The pandemic impacted infrastructure providers and customers with far-reaching implications for recovery. As remote working has already become ‘business as usual’ for certain sectors and organizations in India and elsewhere (R10), and with continued expansion anticipated in the delivery of public services and business activities online, energy, telecoms, and transportation networks are required to adapt to changing demands. Two areas of concern expressed in interviews related to the provision of urban and rural infrastructure. First, addressing the digital divide is a recovery issue. For instance, lockdown school closures in Portugal highlighted that many children ‘don’t have internet, tablets, or other ways to connect’ (R3). In one Colombian province ‘only forty-eight per cent have an internet connection’ (R40).

Second, public transport usage was down markedly in some metropolitan areas was ‘having a dramatic effect on [municipal] finances’, and getting people back aboard public transport during recovery was seen as critical to sustaining those services which were already ‘in deficit’ pre-pandemic (R36, R37). Cities were therefore taking actions to positively inform attitudes and provide public reassurance over safety, including running at reduced capacity to facilitate physical distancing. This was not universally the case, of course, and public transport ‘was very difficult to control’ and kept running within, as well as commuting into, Buenos Aires, Argentina, partly because many could not work remotely (R61). Further, ‘outside of major metropolitan areas’, as one interviewee underlined, public transport is already limited, and rural areas are often ‘lacking in investment’ (R31).

Waste management, especially in dealing with the increased volume associated with personal protective equipment (PPE), was also a concern. This issue registered with interviewees on several fronts, including uncertainty over how medical waste should be dealt with from a ‘health and safety’ perspective (R14). Indeed, ‘used masks and gloves’ were already littering public spaces and lakes, ‘posing not only an environmental, but health risks to people and animals’ (R19).

The pandemic reshaped global-local supply chains and logistics with implications for how governments reinstate local preparedness for future emergencies. Severe difficulties in procuring PPE, for example, exposed many limitations of the ‘just in time economy’ (R7). Consequently, several interviewees foresee significant changes in the manufacturing, purchasing, and storage of key resources for future crises. In the UK, this should encompass the better management of ‘national stockpiles’ of critical equipment (R7), with local authorities also needing to pursue greater ‘self-sufficiency’ in improving their resiliency (R2). From the perspective of Serbia, private sector organizations, given such ‘localization’ processes and the expected reduction in imports, were advised to ‘evaluate…the robustness of domestic supply chains’ (R19).

4.4. Environment

Disasters transform public attitudes and policies towards the environment (Pradhan et al., Citation2021). Among the ‘eco-friendly outcomes’ observed during the first COVID-19 lockdown were ‘cleaner air, water, and healthier lifestyles’ (R19). Societal awareness was heightened around the benefits of living sustainably, positively valuing, and using nature and green spaces for mental and physical well-being. ‘Locking in’ such behavioral changes during recovery, while simultaneously advancing strategies on climate change and de-carbonization, are challenges for the spatial planning and environmental health systems. For example, the creation of active travel infrastructure for cycling and walking, combined with enlarging public spaces, and measures to disincentivize private cars, was swiftly implemented by one Italian city (R14). Problematically, in this instance, car usage increased significantly (by 50%) in parallel with a reduction in public transport use, with worrying air quality implications for ‘one of the most polluted areas of Europe’.

Achieving a ‘green recovery’ supportive of climate resilience faces major obstacles. ‘Vested interests in sustaining coal and gas’ supported by some governments, for example, are resistant to a rapid transition from a hydrocarbon-based economy; the latter is driven by the short-term electoral cycles and implications of local job losses (R13). In the US, the politics of one state is such that climate change does not feature prominently in policies around energy generation and conservation, which are instead centered on mitigating the ‘utility cost burden on people’ (R48). While the pandemic may have shown ‘how quickly systems can change if we need them to’ (R5), the politics over decarbonization remains problematic. As one Australian interviewee stated, economic recovery now ‘has to take precedence’ over the environment (R16).

The positive environmental affordances of the pandemic are also unevenly distributed both between and within countries. ‘People who are privileged’ could enjoy the quality-of-life advantages afforded during lockdown (e.g. time with family, food, health, and the environment), in contrast to those without jobs or who ‘depend on [a subsistence] livelihood on a daily basis’ (R10). Indeed, ‘people living in the slums [in India and Bangladesh] don’t have the luxury of free access to water’ (R55), excluding many from the most basic of public health measures like regular hand washing.

4.5. Health

Interviewees underlined the need for investment during recovery in healthcare systems. Several interviewees in India talked about the relative success of Kerala state in dealing with the pandemic early on, partly thanks to ‘learning from an earlier Nipah virus outbreak’ and public authorities being ‘aggressive in setting up facilities for [community] testing’ (R10). Thus, developing healthcare infrastructure and capabilities are an urgent priority, echoing thinking aimed at reducing vulnerability in places with weaker public health systems (Gupta et al., Citation2021). So too is ensuring better connectivity between health and the wider system, including the collation of data pertinent to the management of excess deaths. Again, in the context of India, data on deaths as both direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 is difficult to capture because most ‘occur at home’ without being recorded in hospital databases (R55).

Allied to prioritizing health system investment is a wider reorientation that the pandemic prompts towards public health and well-being. Mental health and psycho-social supports, for instance, are recovery issues identified in many interviews as requiring immediate and longer-term action. Here, escalating challenges are driven in part by social isolation, the traumatic aftereffects of coronavirus, and coping with the sudden death of family and friends – ‘How do we deal with people who can’t grieve properly?’ (R2). Further, the expectation that society will have to learn to live with COVID and future pandemic-related risks stresses those for whom recovery means the freedom ‘to do everyday things without fear’ (R8).

4.6. Governance

The governance of recovery is enabled by legislation, policy, and guidance supported by timely information and data informing a robust evidence base, underpinned by appropriate resourcing and financial frameworks. Given the prominent role local government can play in disaster recovery, frameworks are significant in assisting or constraining the ambitions of authorities to implement recovery actions, which must be delivered in the context of pandemic ‘restrictions [in terms of public health measures] coming from national government’, as well as limited local powers and budgets (R14). Concurring with Diamond (Citation2020), several interviewees expressed fears that emergency powers recently introduced have emboldened authoritarianism globally.

The multi-dimensional impacts of the pandemic and resourcing challenges in delivering recovery strategies underscore the importance of partnerships and coordination spanning multiple sectors and governance levels. As ‘public officials are not able to solve social issues by themselves’, getting ‘everyone around the table’ was a priority undertaken within one municipality in Colombia (R40). Such partnerships involve creating structures that allow people from different organizations to work together. Here, ‘good practice’ includes early activation of recovery coordination structures, ‘not replicating response structures’, and co-producing objectives and success criteria with key stakeholders (R58).

However, the need to reexamine central-local government relations to enhance disaster preparedness was a concern for many interviewees. In large countries like India ‘top-down disaster management’ has proven ineffective, with ‘de-centralization… the only way to improve governance’ (R55). Cross-boundary working is also deemed problematic within several countries, including difficulties experienced aligning approaches between regions in Italy (R57), and ‘different governance models’ hampering the capacity to provide mutual support across Canadian provinces (R9). Developing a more effective coordination apparatus nationally while bolstering powers and coordination capabilities regionally and locally are therefore imperative.

Strategic communications are also vital. Among the key issues discussed was the need for clear and consistent messaging that the public can understand ‘and respond to well’ (R10). Tailoring information to reach people ‘where they live’, using traditional (e.g. telephone, notice boards) and multimedia channels (e.g. an ‘online one-stop shop’ (R2); and ensuring effective outreach to linguistically diverse groups including immigrant workers, for instance, through messaging in multiple languages to ‘reach out and inform’ (R32), are other examples. Foregrounding experts and trained communicators as more trustworthy messengers during a crisis, are also critical to mitigating significant issues of trust, mixed messaging, and ‘bad noise from media’ (R46).

Innovations and challenges in the governance of delivering recovery and renewal inform the pandemic lessons conveyed by interviewees. The early establishment of internal ‘cross-functional teams’ was designed by one US municipality to provide ‘bandwidth and [enable] collective thinking’ towards recovery – that is, to do more together in the limited resources available (R122). Particularly challenging for governance given that COVID-19 ‘impacts everything’, are the complexities of transitioning from the response to recovery phases, not least in avoiding ‘mission creep’ (e.g. deviating from initial recovery objectives) and in considering ‘when is the endpoint for recovery’ (R58). Indeed, this transition is especially complex during a prolonged pandemic marked by oscillating waves of infection.

5. Application of the recovery framework

Our research extends our understanding of COVID-19’s cascading impacts across interconnected societal sectors. The identification of the domains and sub-categories in is an important first step to ensuring the comprehensiveness of actions to pursue recovery for development. This comprehensiveness can allow cross-checking of impacts, needs, and lessons learned against a framework of what the disaster may have affected – ensuring nothing is missed when identifying recovery actions and reinstating local preparedness. At the same time, however, our research identifies aspects of practice that a global community of experts has reappraised owing to the consequences that the pandemic has already had. Below, we outline how these lessons might be implemented by local authorities undertaking recovery efforts pertinent to complex disasters characterized by cascading effects.

5.1. Creating a ‘localized’ recovery strategy

Our findings on implementing the multi-dimensional recovery framework are informed by ongoing critiques of managerialism across development studies – for it is organizations that strategize and organize recovery. As Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten (Citation2022, p. 241) assert, ‘managerialism is the belief that organisations operating in wildly varying places…can be optimally governed through universal standards of management practices’. Managerialism contends that a set of generalizable principles, enacted by people with generic and transferable skills, can be imposed regardless of differences across places. Imposing singular principles, managerialisms expansion worldwide hinders the democratic process because it extracts the political agency and decision-making of people. It bears ideological and political ramifications to be avoided.

Instead, we argue that recovery implementation should be informed by perspectives that seek to harness and enable retention of, the differences between places (Escobar, Citation2018). To do so, our guidance draws upon the concept of localization elaborated across development studies and policymaking (Barakat & Milton, Citation2020). We lean particularly on how localization emphasizes the process through which guidance might be translated across different settings by being shaped by and responsive to local cultures and conditions. We recognize that the local, however defined, is permeated with competing interests, power dynamics, and exclusionary practices along multiple dimensions (Pincock, Betts, & Easton-Calabria, Citation2021).

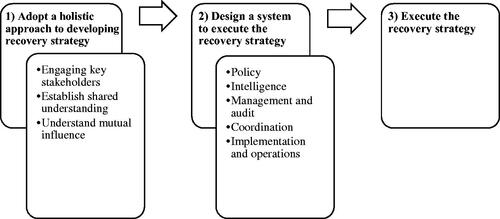

Advancing a strategy requires a process to ensure that recovery meets the needs of multiple domains and, here, principles from systems thinking are suited to broad-based planning. A systemic approach facilitates a holistic consideration of the recovery framework in and supports managing the governance structures to deliver it. To be sustainable, our framework should be interpreted as part of an interdependent strategy of social and organizational change rather than segregated areas of improvement for individual domains (e.g. focusing only on healthcare). The importance of holistic recovery is increasingly recognized (Corbin, Citation2015), including by international organizations (UNISDR, Citation2015). The strategy should incorporate all thematic domains and sub-categories. We propose a condensed process of three steps to operationalize the framework, as shown in , recognizing its iterative nature and interlinked components.

5.2. Adopt a holistic approach to developing the recovery strategy

The possibilities for meaningful community co-production and multi-sector partnership working in recovery vary across countries, political systems, and cultures, and invariably entail complex power relations. In advocating an approach to developing strategies that prioritizes inclusiveness, three practices in the systems thinking literature are relevant and important to operationalizing the recovery framework: engaging key stakeholders, establishing shared understanding, and understanding mutual influence.

Engaging key stakeholders Strategy co-production requires input from the agencies responsible for the six domains in the recovery framework. In turn, these agencies should ensure that their stakeholders contribute to, and support, the strategy and its implementation. The systems literature argues strongly for group decision-making and accommodating a wide spectrum of views in developing strategies for complex social change (Checkland & Poulter, Citation2010). Stakeholders should be identified and selected considering the framework themes. This is important to (1) earn the necessary support when the strategy is implemented, (2) utilize the knowledge, experiences, and perspectives of multiple stakeholders to identify vulnerabilities, risks, and needs of diverse communities and sectors, and (3) ensure agreement about the feasibility of the strategy (Ackermann et al., Citation2014).

It may be difficult to engage with the plethora of stakeholders in recovering from COVID-19 because it differentially impacts everyone and every organization. However, policy-makers, public agencies, businesses, charities, volunteers, and local communities need to be equal partners in the recovery system responsible for co-developing the strategy (Blakeney, Citation2002). Such ‘state-citizen alliances’, as Leach et al. (Citation2021) suggests, are crucial in recovering from disasters and are a ‘driver of transformations to follow’.

Establishing shared understanding of Diverse perspectives on how to recover from disasters may also conflict (e.g. GDP growth vs. ‘well-being economics’). The framework in provides a basis for stakeholders to establish a shared understanding of recovery and negotiate actions with others. Developing a mutual appreciation of the other’s motivations and experiences can underpin a common sense of direction, vision, and aspirations. The strategy development process is more effective when collectively working towards the same goal (Wulun, Citation2007). Developing shared understanding is only possible between those actively engaged within the strategy process, drawing attention towards the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the ‘how’ and ‘who’ decides upon the selection of stakeholders. Even with a localization agenda exclusionary practices can still perpetuate, as Pincock et al. (Citation2021) explore in the context of refugee-led organizations and humanitarian assistance programs in Uganda.

Understanding mutual influence Stakeholders and the agencies involved in the recovery strategy should also acknowledge the potential ramifications of their actions on the work of peer agencies and their strategic outcomes. Stakeholders may believe that optimizing their particular part optimizes the entire system (Stroh, Citation2015). However, a systemic approach requires an improving understanding of how a change/action in one domain has a consequential impact on another domain—thus aiming to optimize outcomes through spillover effects. Building mutual understanding requires acknowledgement of these interdependencies via communication between agencies. It is not always possible for agencies to work toward a single goal, but the aim is for sufficient alignment and collaboration so that actions do not knowingly cause detrimental outcomes elsewhere. In practice, the stakeholders involved should discuss their contribution to optimize the delivery of the recovery framework.

5.3. A system to execute the strategy

A recovery strategy will be challenged in practice by operational impediments to its execution. Evidence from multi-hazard disaster contexts indicates the difficulties typically experienced that can hinder recovery. This includes acute difficulties in maintaining the coherence of multi-partner recovery coordination structures over time (Raju & Becker, Citation2013). Poor coordination or a misaligned recovery strategy hampers reconstruction efforts in respect of damaged housing and physical infrastructure (Ritchie & Tierney, Citation2011). However, adopting systems thinking learning can mitigate these challenges and structure complex recovery processes.

To guide the recovery strategy, Beer (Citation1981) provides a five-component structure for the governance of recovery: policy, intelligence, management, coordination, and operations. Thus, for the actions to be pursued to achieve the recovery strategy, the operations component consists of the delivery teams responsible for implementation. This may include local authorities leading in the delivery of emergency housing for vulnerable communities in collaboration with multi-sector partners. The coordination component, in turn, assists in aligning the activities of the operational teams representing different agencies. Coordinators mitigate or resolve conflicts and competition between agencies to ensure the harmonious delivery of the strategy.

Pressures to adapt to the unpredictable environment is a challenge that relates to the intelligence component. Analyzing and foreseeing changes in the external environment and their implications (e.g. for the six principal domains and their sub-categories within the recovery framework), are important to sustaining the recovery process and achieving its objectives. For example, consistent access to reliable information, as Sou et al. (Citation2021) found in Puerto Rico, is an enabler of household disaster recovery. Integrated mechanisms allowing communities to relay their needs to recovery agencies should form part of a two-way information flow. The intelligence component, therefore, facilitates the identification of what is needed to adapt recovery actions to new conditions and information to exploit emergent opportunities and foresee cascading risks.

Finally, to decide the overall direction of recovery co-ordination structures, the policy component defines the scope of what should be included and leads to developing the strategy (Rios, Citation2012). Critically, this component helps to mutually determine the ethos, norms, and values that will govern the strategy (Beer, Citation1981). However, pursuing shared objectives is challenging given the diversity of stakeholders involved in disaster recovery who, among other factors, will have ‘different interests, tasks, and goals’ (Quarantelli, Citation1997, p. 48). Competing priorities problematize the development of a recovery strategy. A good place to start is by coalescing around a shared action plan for transactional recovery before developing a shared vision for inclusive development that tackles underlying causes of risk and inequalities

6. Conclusion

As explored in this article, the prolonged, uneven, and cascading effects of the COVID-19 pandemic challenges us to rethink post-disaster recovery. This reappraisal has concerned what recovery encompasses and who it is for. It has also considered how to design and implement a strategy that addresses the complexity of a long-term recovery for development. Thus, we have introduced a multi-dimensional, practice-oriented framework to support those working on recovery planning and implementation at a local level. The framework captures the interconnected issues across six principal domains – communities, economic, infrastructure, environment, health, and governance – representing the key areas of impact around which recovery strategies and renewal initiates can be progressed. These domains, together with their sub-categories, can be harnessed in assessing disaster impacts and the recovery needs of affected communities, as well as a checklist for generating ‘lessons learned’ to ensure better preparedness for concurrent and future disasters. They also advance the integration of disaster recovery with pandemic recovery planning, although further efforts are needed longer-term to address the related obstacles and opportunities (Schoch-Spana et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, we offer that designing and implementing a recovery strategy using a systems approach is an effective way to operationalize the framework. The three-step process proposed to elaborate such a strategy – adopting a holistic approach, designing a system to execute, and executing the strategy – accommodates the need for flexibility in planning for and delivering bespoke recovery actions with local communities. The pandemic has had highly uneven impacts across society, of course, and the degree of relevancy of specific framework components will differ and change as the needs of communities evolve. Interpretation is essential in adapting the framework to the circumstances of local communities, especially in ‘fragile’ places experiencing compound and intersecting disasters (Hilhorst & Mena, Citation2021).

Our focus has been on the elaboration of a framework that is suited to supporting strategic action by local public sector agencies and multi-sector partnerships to progress post-disaster recovery for development. The stimulus for such an approach emerged from long-standing engagement with policy-practice communities both before and in the early months of COVID-19. Our collaborative practice-testing of the framework and implementation strategy with local partners in multiple countries continues as they inform local pandemic recovery initiatives and evaluative activities. Longitudinal qualitative explorations of the processes and long-term outcomes of disaster recovery are scarce (Jordan & Javernick-Will, Citation2014; Sou et al., Citation2021). Our ongoing ethnographic engagement, together with the work of others situated at the interface of research and policy practice, can contribute towards generating much-needed theoretical and practical insights. The frequency and complexity of disasters, including pandemics, and their impacts on global development reinforce the need for applied research of this nature on recovery.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (11.9 KB)Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their consideration and insights on the first submitted version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackermann, F., Howick, S., Quigley, J., Walls, L., & Houghton, T. (2014). Systemic risk elicitation: Using causal maps to engage stakeholders and build a comprehensive view of risks. European Journal of Operational Research, 238(1), 290–299. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2014.03.035

- Alipour, F., Khankeh, H., Fekrazad, H., Kamali, M., Rafiey, H., & Ahmadi, S. (2015). Social issues and post-disaster recovery: A qualitative study in an Iranian context. International Social Work, 58(5), 689–703. doi:10.1177/0020872815584426

- Barakat, S., & Milton, S. (2020). Localisation across the humanitarian-development-peace nexus. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 15(2), 147–163. doi:10.1177/1542316620922805

- Barnett, D., Rosenblum, A., Strauss-Riggs, K., & Kirsch, T. (2020). Readying for a post-COVID-19 world: The case for concurrent pandemic disaster response and recovery efforts in public health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 26(4), 310–313.

- Beer, S. (1981). Brain of the firm (2nd ed.). Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- Berke, P., Cooper, J., Aminto, M., Grabich, S., & Horney, J. (2014). Adaptive planning for disaster recovery and resiliency: An evaluation of 87 local recovery plans in eight states. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 310–323. doi:10.1080/01944363.2014.976585

- Blackman, D. A., Nakanishi, H., Benson, A. M., & Freyens, B. (2016). Long-term disaster recovery as a complex problem: Giving disaster resilience new meaning. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2016(1), 10752. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2016.308

- Blackman, D., Nakanishi, H., & Benson, A. M. (2017). Disaster resilience as a complex problem: Why linearity is not applicable for long-term recovery. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 121, 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.09.018

- Blakeney, R. L. (2002). Providing relief to families. Washington, DC: Office for Victims of Crime, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/ovc_archives/bulletins/prfmf_11_2001/188912.pdf

- Boaden, R., Powell, D., Shaw, D., Bealt, J., O'Grady, N., Fattoum, A., & Furnival, J. (2020). Recovering from COVID-19: The key issues. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 1(2), 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.jnlssr.2020.06.002

- Bolin, B., & Kurtz, L. C. (2018). Race, class, ethnicity, and disaster vulnerability. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research (pp. 181–203). Cham: Springer.

- Bonilla, Y. (2020). The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA. Political Geography, 78, 102181. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102181

- British Academy (2021). The COVID decade: Understanding the long-term societal impacts of COVID-19. London: The British Academy.

- Campbell-Verduyn, M., & Hütten, M. (2022). Governing techno-futures: OECD anticipation of automation and the multiplication of managerialism. Global Society, 36(2), 240–260. doi:10.1080/13600826.2021.2021148

- Chandrasekhar, D., Zhang, Y., & Xiao, Y. (2014). Nontraditional participation in disaster recovery planning: Cases from China, India, and the United States. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 373–384. doi:10.1080/01944363.2014.989399

- Checkland, P., & Poulter, J. (2010). Soft systems methodology. In M. Reynolds & S. Holwell (Eds.), Systems approaches to managing change: A practical guide (pp. 191–242). London: Springer.

- Corbin, T. B. (2015). Leveraging disaster: Promoting social justice and holistic recovery through policy advocacy after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Management and Social Policy, 22(2), 5.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Cretney, R. M. (2017). Towards a critical geography of disaster recovery politics: Perspectives on crisis and hope. Geography Compass, 11(1), e12302. doi:10.1111/gec3.12302

- Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., & Webb, J. (2008). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change, 18(4), 598–606. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

- Cutter, S. L., Burton, C. G., & Emrich, C. T. (2010). Disaster resilience indicators for benchmarking baseline conditions. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 7(1), 51. doi:10.2202/1547-7355.1732

- Davis, I., & Alexander, D. (2015). Recovery from disaster. London: Routledge.

- Diamond, L. (2020). Democracy versus the pandemic: The coronavirus is emboldening autocrats the world over. Foreign Affairs, June 13. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-13/democracy-versus-pandemic

- Djalante, R., Shaw, R., & DeWit, A. (2020). Building resilience against biological hazards and pandemics: COVID-19 and its implications for the Sendai Framework. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100080.

- Eden, C. (1992). Strategy development as a social process. Journal of Management Studies, 29(6), 799–812. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.1992.tb00690.x

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse radical interdependence. Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fernandez, G., & Ahmed, I. (2019). Build back better’ approach to disaster recovery: Research trends since 2006. Progress in Disaster Science, 1, 100003. doi:10.1016/j.pdisas.2019.100003

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (2015). Guide to developing disaster recovery frameworks. Sendai Conference Version. GFDRR, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Development Programme.

- Gupta, J., Bavinck, M., Ros-Tonen, M., Asubonteng, K., Bosch, H., van Ewijk, E., … Verrest, H. (2021). COVID-19, poverty, and inclusive development. World Development, 145, 105527. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105527

- Hasegawa, A., Ohira, T., Maeda, M., Yasumura, S., & Tanigawa, K. (2016). Emergency responses and health consequences after the Fukushima accident; Evacuation and relocation. Clinical Oncology, 28(4), 237–244.

- Hilhorst, D., & Mena, R. (2021). When Covid-19 meets conflict: Politics of the pandemic response in fragile and conflict-affected states. Disasters, 45(S1), 74–94. doi:10.1111/disa.12514

- Horney, J., Dwyer, C., Aminto, M., Berke, P., & Smith, G. (2017). Developing indicators to measure post-disaster community recovery in the United States. Disasters, 41(1), 124–149.

- Ingram, J. C., Franco, G., Rumbaitis-del Rio, C., & Khazai, B. (2006). Post-disaster recovery dilemmas: Challenges in balancing short-term and long-term needs for vulnerability reduction. Environmental Science & Policy, 9(7–8), 607–613. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2006.07.006

- Jordan, E., & Javernick-Will, A. (2014). Determining causal factors of community recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disaster, 32(3), 405–427.

- Kennedy, M., Gonick, S. A., & Errett, N. A. (2021). Are we ready to build back “healthier?” An exploratory analysis of U.S. state-level disaster recovery plans. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8003. doi:10.3390/ijerph18158003

- Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. London: Penguin.

- Leach, M., MacGregor, H., Scoones, I., & Wilkinson, A. (2021). Post-pandemic transformations: How and why COVID-19 requires us to rethink development. World Development, 138, 105233.

- Maini, R., Clarke, L., Blanchard, K., & Murray, V. (2017). The Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction and its indicators – Where does health fit in? International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 8(2), 150–155. doi:10.1007/s13753-017-0120-2

- McCartney, G., Pinto, J., & Liu, M. (2021). City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities, 112, 103130.

- Nohrstedt, D., Mazzoleni, M., Parker, C. F., & Di Baldassarre, G. (2021). Exposure to natural hazard events unassociated with policy change for improved disaster risk reduction. Nature Communications, 12(1), 193.

- Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150.

- Olshansky, R. B., Hopkins, L. D., & Johnson, L. A. (2012). Disaster and recovery: Processes compressed in time. Natural Hazards Review, 13(3), 173–178. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000077

- Paudel, D., Rankin, K., & Le Billon, P. (2020). Lucrative disaster: Financialization, accumulation and post-earthquake reconstruction in Nepal. Economic Geography, 96(2), 137–160. doi:10.1080/00130095.2020.1722635

- Peacock, W. G., Van Zandt, S., Zhang, Y., & Highfield, W. E. (2014). Inequities in long-term housing recovery after disasters. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(4), 356–371.

- Pescaroli, G., & Alexander, D. (2018). Understanding compound, interconnected, interacting, and cascading risks: A holistic framework. Risk Analysis, 38(11), 2245–2257. doi:10.1111/risa.13128

- Pincock, K., Betts, A., & Easton-Calabria, E. (2021). The rhetoric and reality of localisation: Refugee-led organisations in humanitarian governance. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(5), 719–734. doi:10.1080/00220388.2020.1802010

- Pradhan, P., Subedi, D. R., Khatiwada, D., Joshi, K. K., Kafle, S., Chhetri, R. P., … Bhuju, D. R. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic not only poses challenges, but also opens opportunities for sustainable transformation. Earth’s Future, 9(7), e2021EF001996. doi:10.1029/2021EF001996

- Quarantelli, E. L. (1997). Ten criteria for evaluating the management of community disasters. Disasters, 21(1), 39–56. doi:10.1111/1467-7717.00043

- Raju, E., & Becker, P. (2013). Multi-organisational coordination for disaster recovery: The story of post-tsunami Tamil Nadu, India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 4, 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2013.02.004

- Rios, J. P. (2012). Design and diagnosis for sustainable organizations: The viable system method. Berlin: Springer.

- Ritchie, L. A., & Tierney, K. (2011). Temporary housing planning and early implementation in the 12 January 2010 Haiti earthquake. Earthquake Spectra, 27(1_suppl1), 487–507. doi:10.1193/1.3637637

- Rouhanizadeh, B., Kermanshachi, S., & Nipa, T. J. (2020). Exploratory analysis of barriers to effective post-disaster recovery. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 5, 101735.

- Schipper, L., & Pelling, M. (2006). Disaster risk, climate change and international development: scope for, and challenges to integration. Disasters, 30(1), 19–38.

- Schoch-Spana, M. (2020). An epidemic recovery framework to jump-start analysis, planning, and action on a neglected aspect of global health security. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71(9), 2516–2520. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa486

- Schoch-Spana, M., Ravi, S. J., & Martin, E. K. (2022). Modeling epidemic recovery: An expert elicitation on issues and approaches. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114554. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114554

- Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Seale-Feldman, A. (2020). The work of disaster: Building back otherwise in post-earthquake Nepal. Cultural Anthropology, 35(2), 237–263. doi:10.14506/ca35.2.07

- Shaw, D., Smith, C. M., & Scully, J. (2017). Why did Brexit happen? Using causal mapping to analyse secondary, longitudinal data. European Journal of Operational Research, 263(3), 1019–1032. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2017.05.051

- Shaw, D., Fattoum, A., Moreno, J., & Bealt, J. (2020). A structured methodology to peer review disaster risk reduction activities: The Viable System Review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 46, 101486. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101486

- Sheller, M. (2020). Island futures: Caribbean survival in the anthropocene. Duke University Press, Durham NC.

- Simonović, S. P. (2011). Systems approach to management of disasters: Methods and applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Sou, G. (2019). Sustainable resilience? Disaster recovery and the marginalization of sociocultural needs and concerns. Progress in Development Studies, 19(2), 144–159. doi:10.1177/1464993418824192

- Sou, G., Shaw, D., & Aponte-Gonzalez, F. (2021). A multidimensional framework for disaster recovery: Longitudinal qualitative evidence from Puerto Rican households. World Development, 144, 105489. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105489

- Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (2015). Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Geneva: UNISDR.

- United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development (2021). Financing for sustainable development report 2021. New York, NY: UNIAFT.

- Wulun, J. (2007). Understanding complexity, challenging traditional ways of thinking. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 24(4), 393–402. doi:10.1002/sres.840