Abstract

This article explores the historical origins of the open economic model that has prevailed in modern Hong Kong and Singapore through two major ‘critical junctures’ which shaped their respective institutional trajectories. In both countries, it was the British in the early nineteenth century that first laid the institutional foundations for an open economic model. The unique Anglo-Chinese alliance that emerged explains the widespread social acceptance of economic openness in both colonies, even in the post-war order when decolonisation typically meant a rejection of colonial economics. The aftermath of World War 2 then saw Singapore layering new developmental state institutions without totally abandoning its reliance on free trade. This was a point of divergence when the new Singapore developmental state disrupted the Anglo-Chinese institutional alliance that had previously underpinned capitalist development in both countries. My account thus elucidates the historical embeddedness and peculiarities of both countries’ political economy and why they are not so easily replicable as liberals recommend. I also provide evidence on the considerable economic progress that colonial capitalism had fostered, which places the achievements of Singapore’s state-led industrialisation in greater perspective.

Keywords:

1. Situating institutional development in time

Singapore and Hong Kong are two of the most economically prosperous nations today. Their real national income per capita in 2018 are USD 61,056 and USD 45,284, respectively (World Bank, Citation2022). Both achieved rapid economic growth in the late twentieth century, together with the other East Asian ‘Tiger Economies’. From 1960 to 2000, Singapore grew by a factor of 1592% and Hong Kong, by 1045% (World Bank, Citation2022). Both city-states also rank amongst the top in major development indicators such as the Human Development Index.

It is taken for granted that their economic growth occurred under an ‘open economic model’, defined as one highly open to international trade, labour, and capital flows, as well as a general adherence to private property rights and the rule of law. Significantly, the volume of trade today as a contribution to national income is 338% and 403% in Singapore and Hong Kong, respectively. Today, both are small and open city-states with a sizable presence of major businesses and expatriate population which dominate the labour force (Prime, Citation2012).

There are two related questions this article seeks to answer. First, why is it that, in the post-1945 WW2 aftermath, both countries largely continued with this open economic model at time when many counterparts started experimenting with either socialism or protectionism? Second, why did the continuation of this economic model not encounter the staunch anti-colonial resistance seen in other decolonising countries at the time? Even Singapore, which attained independence and established a developmental state arrangement, did not totally renounce economic openness but rather grafted upon this colonial tradition new interventionist institutions. The strategic locations of both city-states are an obvious answer, but this paper argues that the answers to these questions are best understood through a historical institutionalist analysis of the impact of British colonialism, particularly the way it was rooted in a unique Anglo-Chinese collaboration which allowed it to reproduce over time.

Accordingly, this article explores the historical evolution of the open economic model that has prevailed in modern Hong Kong and Singapore through two major ‘critical junctures’ which shaped their respective institutional trajectories: the arrival of the British in the early nineteenth century as well as the immediate aftermath of end of World War 2. The arrival of the British laid the institutional foundations for an open economic model that has persisted to varying degrees in both city-states. The unique Anglo-Chinese alliance that emerged explains the widespread social acceptance of economic openness in both colonies, even in the post-war order when decolonisation typically meant a rejection of colonial economics. The aftermath of World War 2 then saw Singapore layering new developmental state institutions without totally abandoning its reliance on free trade. This was a point of divergence when the new Singapore developmental state disrupted the Anglo-Chinese institutional alliance, which was a key mechanism that underpinned capitalist development in both countries.

Therefore, this paper situates the modern political economy of Hong Kong and Singapore within the framework of historical institutionalism, which is concerned with how temporal processes shape the origins and subsequent development of political and economic institutions (Fioretos et al., Citation2016). Accordingly, I employ the concepts of ‘critical junctures’ and ‘path dependence’, and show how the British arrival in early nineteenth century (1819–1841) established market-based governance that facilitated trade and immigration-based growth of both city-states till present-day. The British, upon arrival, encountered a unique ‘institutional tabula rasa’ in Hong Kong and Singapore, which was a permissive factor that accorded it unprecedented agency in shaping local governance. Crucially, the economic openness that was introduced saw the emergence of a class of Chinese community leaders who forged a productive alliance with official British rulers. The mutual convergence of interests and values formed the basis of a collaborative Anglo-Chinese relationship and was mechanism behind path-dependent institutional development.

However, this equilibrium was disrupted in post-war Singapore (1959–1965), where political contestation saw the new developmental state elites suppressing the political power of traditional Chinese community leaders – a development that never occurred in Hong Kong. The Chinese elites in Singapore had fractured in a way not seen in Hong Kong, and the political victorious faction led by Lee Kuan Yew layered a new technocratic approach onto existing governance while simultaneously being constrained by the need for economic openness. Consequently, post-war developments saw Hong Kong maintaining a laissez-faire path where local entrepreneurship occupied a central role, while Singapore grafted new developmental statist institutions which supplanted Chinese entrepreneurs.

My account contributes to the long-standing debate on the role of the state in East Asia’s development. On one hand, economic liberals portray both city-states as beacons of economic freedom – topping economic freedom indices—and how growth necessarily resulted from such an institutional adoption (see Mitchell, Citation2017; Rahn, Citation2014). These accounts depict Hong Kong and Singapore’s modern leaders, namely Lee Kuan Yew and John Cowperthwaite, as ‘political architects’ who forged the path of economic openness for their respective communities (Monnery, Citation2017; Tilman, Citation1989). Separately, developmental state scholars insist that East Asian nations were in no way beacons of economic freedom but in fact resorted to intrusive economic planning (Chu, Citation2016; Haggard, Citation2004). Singapore stands out in particular; it is said that its industrial policy interventions are amongst the most extensive ever practised (Chang, Citation2011), and thus its growth is a result of the ‘long arm of state intervention than it is of the invisible hand’ (Lim, Citation1983).

The problem with both accounts is that they are functionalist and simplistic. The political economy of free trade in Hong Kong and Singapore cannot be construed as a product of ‘intelligent design’ by policymakers but were an inheritance of British colonialism, which itself was shaped by contingent circumstances in the nineteenth century. Even Singapore’s developmental statism which began in 1959, were layered onto the existing layer of free trade practices without totally abolishing them. There are specific weaknesses of both positions. First, the weakness of the statist position is that it neglects the fact that Hong Kong and Singapore’s growth had started from a high base owing to flourishing trade and immigration during the colonial era.Footnote1 A longer historical analysis suggests that the highly vaunted achievements of the Singapore developmental state, are overstated. I show, through historical excavation of consumer advertisements and economic statistics, that a vibrant economy had already pre-existed the Singapore developmental state. The liberal position must also be tempered. While it is true that both are generally free economies, economic freedom statistics obscure structural differences that originated in the post-war period: in Singapore, domestic private entrepreneurship has historically taken a subordinate role to the state, which has crowded it out through extensive government-linked corporations and industrial policy (Audretsch & Fiedler, Citation2022; Cheang, Citation2022).

2. Inheriting British liberal ideas

Some scholars focus on the character of the colonisers when analysing its impact. In this regard, the British empire is said to be distinct, in its relatively liberal, humane and benign approach to ruling indigenous peoples (Lange et al., Citation2006). Certainly, Singapore and Hong Kong were recipients of British liberalism in the early nineteenth century, a time when a classical liberal ethos was emergent in wider Europe.

A distinctive feature of British colonial governance is its liberal flavour. This was personified by Singapore’s Stamford Raffles, who displayed classical liberal tendencies on matters relating to slavery, trade, and property ownership (Bastin, Citation2009). He had opposed Dutch mercantilism on humanitarian grounds, i.e., that its subjects were subject to the oppression of extractive Dutch practices (Collis, Citation2009, p. 60). Free trade was thus more than an economic instrument, but a liberating force through which the local people could become empowered. Raffles was also a well-known proponent of abolitionism, and his liberal sensibilities became institutionalised in Singapore’s first legal code, called the Raffles Regulations (see supplemental Appendix), which historians have acknowledged formed the basis for subsequent legal development ever since.

Similarly, the governance structure transplanted in Hong Kong had uniquely liberal characteristics which emphasised property ownership and economic openness. Even though local Chinese customs were accorded great latitude, they were still subject to an overall preference for British values of property rights and the rule of law (see supplemental Appendix). In an important dispatch in 1843, it was declared that:

the right of succession to immovable property and whatever regards the alienation of it should be regulated by English, and not by Chinese laws. Neither must any English subject be held amenable within the island of Hong Kong for any inflicted crime to any Chines tribunal or Chinse law. Again, if there by any Chinese law repugnant to those immutable principles of morality which Christians must regard as binding…the enforcement of any such law even against the Chinese must not be permitted. (Stanley, Citation1843)

At the same time however, it must be acknowledged that even within the British Empire, colonial experiences were diverse. Aside from Hong Kong and Singapore, other significant British colonies in Asia include Malaya, Burma, and India. Yet, none of these colonies were alike Hong Kong and Singapore in their embrace of market freedoms in the post-war era. Between 1947 and 1991, post-colonial India adopted heavy protectionism and dirigiste planning. Post-independence Burma also practised central planning all the way till 2011 under a succession of military dictators. Even though Malaysia did not practice central planning after gaining independence, its economic governance was heavily politicised along ethnic lines, with corruption and problems in the rule of law stymying its present-day development (Gomez, Citation2005).

As such, the character of the British is inadequate as an explanation for the institutional development of their respective colonies. One must look deeper into the local conditions on the ground and the dynamics faced between ruler and ruled, and how British governance evolved over time to produce distinct outcomes. I argue that a significant, though unique, permissive factor that shaped Hong Kong and Singapore was the fact that the British officials encountered an ‘institutional tabula rasa’ upon their arrival, which permitted them to realise their vision in a peculiarly unimpeded fashion.

3. Institutional tabula rasa as permissive factor

Historical institutionalists have analytically clarified the concept of ‘critical junctures’ in terms of its permissive and productive conditions: the former are necessary conditions that loosen structural constraints on individual agency and the latter are conditions that act within the former to bring about change and are reproduced even after the critical juncture closes (Soifer, Citation2012). Arguably, the most significant permissive factor that accorded agency to the British in Hong Kong and Singapore was the sparse local population at the time of their founding. This has far-reaching institutional implications, as the paper will elucidate.

Wishing to transcend traditional historical accounts which typically portray the arrival of the colonisers as a fundamental break from a traditional past, post-colonial historians have recently stressed the long-run continuity that had preceded the Europeans. In the context of Hong Kong and Singapore, it has been said that significant economic activity had already been present. For instance, farming was a ‘principal occupation’ in Hong Kong and there were ‘several villages of some size, as well as hamlets, and a few larger coastal villages which served as market towns for the villages and as home ports for a permanent boat population and visiting craft’ (Hayes, Citation2015). A slew of post-colonial accounts have recently emphasised the longue durée of Singapore’s history, i.e. the new 700-year history school of thought in which Singapore, previously known as ‘Temasek’ by regional seafaring communities, was part of a pan-Asian trade network (Guan et al., Citation2019).

I concede these facts but insist that in the immediate temporal context of the British arrival (1819 in Singapore and 1841 in Hong Kong), local political structures did not comprise a competing power base that frustrated British rule. This is more pronounced in the case of Singapore than in Hong Kong. While Hong Kong had some settled communities when the British arrived, the same cannot be said in Singapore. Numbering no more than a few hundred people using the best estimates, prior to 1819 Singapore had fallen into disrepair. This means that more than in Hong Kong, the British in Singapore had a blank slate upon which to build – a significant point implying that British institutions and policies did not clash with any pre-existing structures. Meanwhile, the immigrants who arrived after the British landed had no prior historical memory of any place called ‘Singapore’ and came from distant lands. Comparatively, in all the neighbouring regions that European powers encountered, whether present-day Burma, Cambodia, Vietnam, China and Thailand, there were pre-existing civilisations with deeply rooted cultural practices, severely frustrating colonial rule (Andaya, Citation1992).

Since there were no pre-existing civilisations or significant political structures that the British had to contend with, the political visions of Hong Kong and Singapore’s early founders were unimpeded. In Singapore, while local indigenous peoples existed prior to Raffles’ arrival, they were scattered across communities numbering at most a few hundred, without a coherent framework of governance. In fact, most historical accounts reveal that prior to the British arrival, Singapore was either very sparsely populated or almost abandoned. Constance Turnbull (Citation2009) notes that in January 1819, a month before the British arrival, Singapore had at most 1000 inhabitants, the majority of whom were Orang Laut, nomadic tribesmen who mainly lived on their boats. Other official estimates put their number to be even lower, at nothing more than 150, ‘living in a few shabby huts’ (Newbold, Citation1839, p. 2; Saw, Citation2012, p. 7). What is striking is that before the close of 1819, official records put the number at approximately 5874 and by the time the first population count was done, it had reached 10,683. In Hong Kong, it was only in the early years of British rule (from 1841 to 1845), that the population risen by more than 300%, driven by the influx of immigrants from abroad.

3.1. Upward trajectory

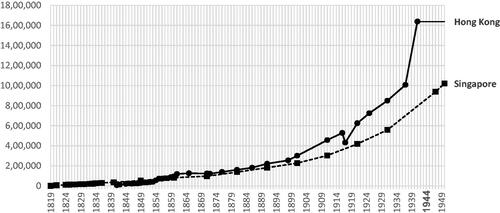

The significance of this critical juncture is demonstrated by the fact that neither territory exhibited a clear and upward trend of growth before the colonial period. The evidence presented here shows a rapid influx of immigrants into Hong Kong and Singapore soon after their British founding, and the ensuing trade-based growth. These were Chinese migrants who were motivated by economic profit and who heard about the establishment of both islands as free ports. The table displays the current author’s estimations of population growth in the aftermath of the British arrival ().

Figure 1. Population in colonial Hong Kong and Singapore, 1819–1950. Source: See supplementary data.

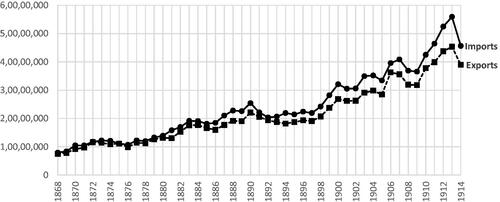

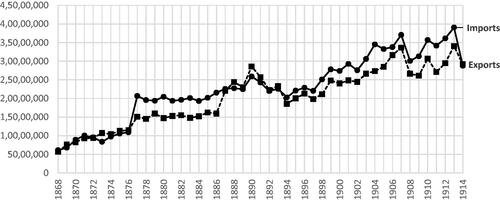

A similar trend can be observed with trade. Upon the arrival of the British, the volume of trade grew rapidly, leading to both places becoming centres of trade in the surrounding regions, with entrepôt trade being the main source of economic growth. The following figures, obtained from Latham (Citation1994), chart out the trade volume of the Straits Settlements and colonial Hong Kong from 1868 to 1914, and are based on the analyses of available Straits Settlements documents as well as estimations of Hong Kong’s trade since it was never officially collected ( and ).

Figure 2. Trade volume of Straits Settlements (in sterling pounds), 1868–1914. Source: See supplementary data.

Figure 3. Trade volume of Hong Kong (in sterling pounds), 1868–1914. Source: See supplementary data.

The abovementioned growth in trade and immigration deserves attention for two reasons. First, it substantiates the idea that the arrival of the British was indeed a significant critical juncture that affected the development of both city-states and constituted a major ‘break’ with the past. The open economic model of both countries and the results it has fetched, are a by-product of more than a century of trade and immigration increases.

Second and more significantly, it situates the contemporary economic achievements of both countries in historical context. This is valuable because it provides a sense of proportion that tempers the developmental state account of Singapore’s contemporary post-war development, a position that overwhelmingly credits the farsighted political leadership of its state elites since independence. Not only was Singapore a vibrant trade entrepot, a burgeoning consumer class had also been formed as a result of exposure to Western markets brought about by British trade.

This author has gathered advertisement materials in early Singapore from 1910 to 1960, which are particularly illuminating since they represent cultural documents that reflect, and even shape, socio-economic conditions. The advertisements suggest the emergence of a modern consumer class. Understandably, early advertising in the pre-war period focused mainly on the affluent classes who could afford upmarket products. While not reflective of the entire population, the emergence of such advertising signals the entrance of consumer mass production into Singapore society. Thereafter, advertising for the masses flourished in the post-war period due to increased literacy and improved living standards (Kuo, Citation1980).

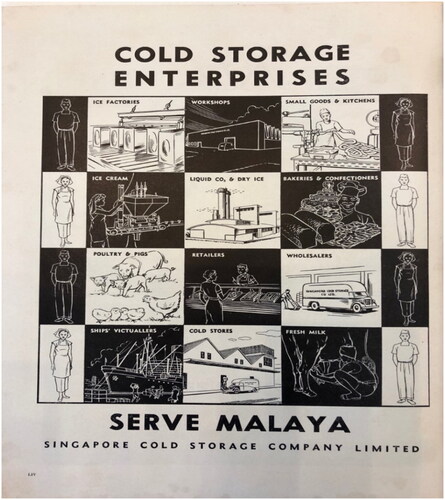

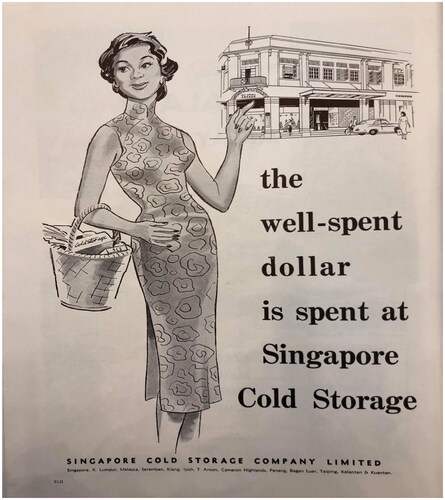

While such early advertisements are abundant, specific themes may be highlighted. In the area of food, Singapore society had witnessed the entrance of supermarkets, with Cold Storage as the first founded in 1903. Supermarkets had arrived at the scene partly due to the emergence of the refrigerator and improvements in food technology like canned food, carbonated water, and preservatives. In the early twentieth century, Singaporeans gained access to overseas food products, mostly through supermarkets (Kong & Sinha, Citation2015; Tarulevicz, Citation2013). The following ads capture the founding of Cold Storage. The first in 1956 illustrates the varied branches of the company’s activities in Singapore promoting itself as a boon to the local economy. The second in 1958 shows how middle-class Asian women were increasingly targeted, unlike the narrow European clientele of the early twentieth century ( and ).

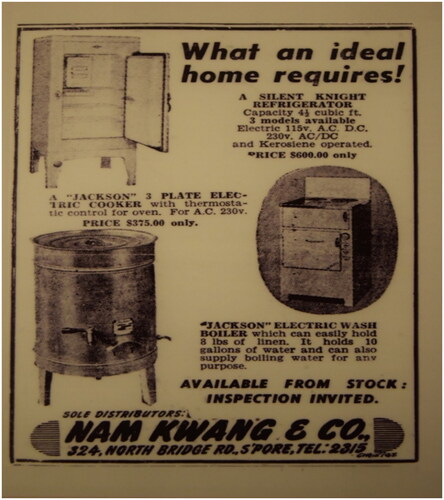

Aside from food, Singaporean society also benefitted from the advent of modern appliances like stoves, water filters and energy equipment, gradually introduced from the early twentieth century (Wong, Citation2018). While most household amenities were initially the luxuries of the upper class, the demand for such equipment was large enough for local dealerships to import them. After the war, with greater affluence and the rise in modern housing, advertising for home appliances like washing machines and refrigerators flourished and featured in many sources in various languages ().

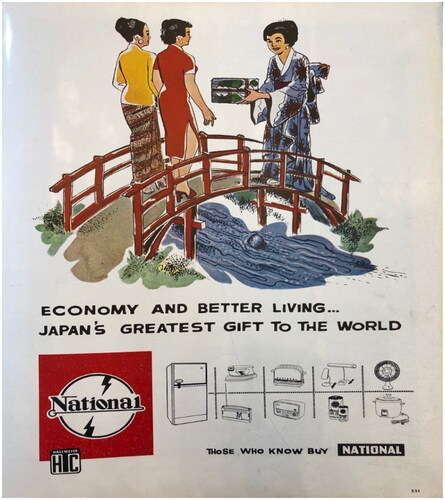

The following advertisement shows a woman in a kimono, representing Japanese brands like National—that had entered the local market—passing the ‘gift’ of better living and economy to women dressed in a cheongsam and sarong kebaya, representing the people of Malaya ().

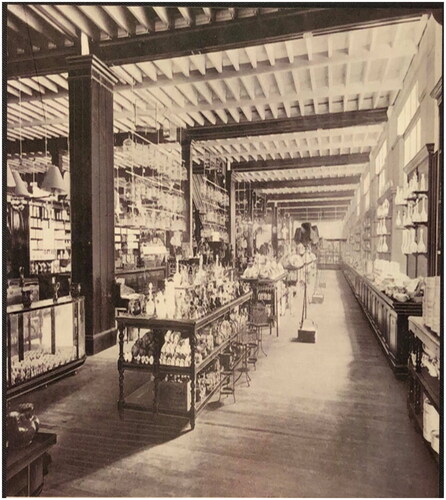

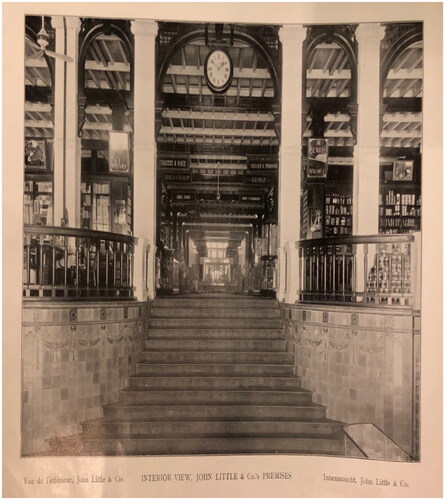

Early Singapore also witnessed the growth of the consumer market for retail and fashion products. Department stores—a Western phenomenon since the industrial revolution—reflected and then enhanced a growing retail culture (Whitaker, Citation2011). The first few were introduced in Singapore housed the latest fashion from overseas and were made more available to the masses over time. Colonial Singapore soon acquired the reputation of a shopping haven and retail ads were commonplace, including stores from High Street and Raffles Place (MacPherson, Citation1998).

John Little, Singapore’s oldest department store, was founded in 1845. By the 1900s, it had become one of the foremost retail outlets in Asia and by the mid-twentieth century, its narrow clientele expanded to include the growing middle class. The first image shows the glassware and crockery department. The second, from the same pictorial book, gives an interior view of the store. These photos published in Views of Singapore positioned it as a local attraction for locals ( and ).

Figure 8. Glassware and crockery room John Little & Co., 1910s. Views of Singapore, National Library Board Singapore.

Figure 9. Interior View, John Little & Co.’s premises, 1910s. Views of Singapore, National Library Board Singapore.

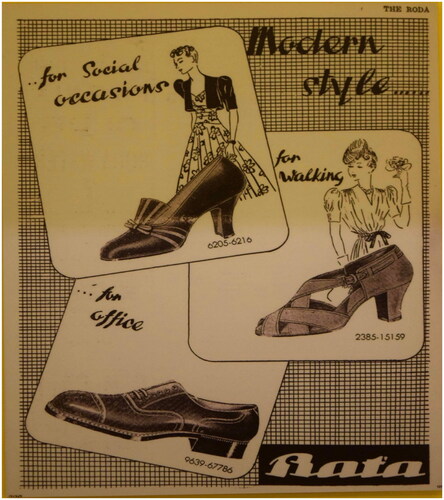

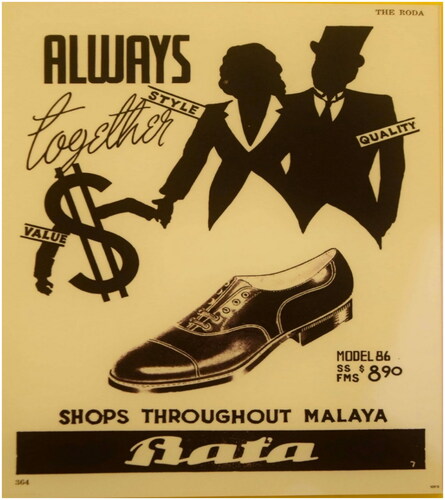

One retail brand that heavily served the consumer mass market was the shoe company Bata which was Europe’s largest shoe manufacturer by 1905. Through competitive pricing and their own sources of cheap rubber, Bata could acquire a significant market share of ordinary Singapore consumers. The 1931 ad below published in The Straits Times positions the brand as one ‘where quality is higher than price’. By selling its mass-produced shoes from Czechoslovakia, Bata purveyed footwear at ‘ridiculously low prices’. Before WW2, Bata’s two factories in Malaya were producing over two million pairs of shoes a year. The 1939 and 1940 ads offer style, quality, and value as Bata’s main selling points ().

These cultural documents highlight the fact that Singapore was long a beneficiary of the economic developments in the Western world. Many new products became available in early-twentieth century Singapore following the development of mass manufacturing in the industrial West (Wharton, Citation2015). Admittedly, given the high shipping costs and relative poverty of Singaporeans, these goods were available only to the upper classes. After the 1920s, and especially after WW2, these products became available to the mass consumer market as shopping became a leisure activity for the masses. This is also reflected through the widening range of publications and advertisements catered to the general consumer (Balasingamchow, Citation2018).

4. Anglo-Chinese linkages and institutional reproduction

The importation of British capitalism led to the mass arrival of Chinese immigrants from neighbouring regions, who in turn collaborated with the British colonisers in mutually beneficial economic practices and who also shaped governance structures. This Anglo-Chinese relationship is central to understanding why the open economic model was successfully transplanted and why it persisted into the twentieth century. This is a unique feature of colonialism in Hong Kong and Singapore which distinguishes them from other colonies where colonial rule was either rejected by the locals, or subject to severe antagonism between the rulers and the ruled. Both city-states not only continued with market-led growth in the twentieth century, but either continued wholesale with British governance (Hong Kong till 1997) or adapted it without fundamentally rejecting it (Singapore).

The fact that both cities were sparsely populated when the British arrived means that the institutions and values they imported did not fundamentally brush against any pre-existing civilisation or culture. This is highly significant. The history of European colonisation is replete with instances of repression of local peoples, to varying degrees. British rule, although relatively benign compared to other European powers, nonetheless faced much local opposition and cultural ‘misalignment’ in various regions. In India, where the local people’s relationship with the British was always tense at best, independence meant favouring socialism, and relinquishing colonial capitalism, which was seen has exploitative and having impoverished society (White, Citation2012, pp. 246–274). Nehru believed that colonial economics had impoverished India and sought socialist state intervention as a corrective (Kaushik, Citation1985). The experience in Burma was far more antagonistic, since British annexation was a product of successive and often bloody Anglo-Burmese Wars. Not only did post-independence Burma not join the Commonwealth (an exception amongst former British colonies) it went down the path of military dictatorship and socialism. Burma’s anti-colonial socialism also had strong religious undertones, especially since its traditional Buddhism had been suppressed by the British (Ileto, Citation1992, pp. 216–219). Colonial rule in various regions is necessarily complex, and much has been written about how it played out in numerous contexts (Trocki, Citation1994). The key distinction here is that both Hong Kong and Singapore were particularly unique in that they were largely ‘blank slates’ that the British could realise their institutional vision in.

The largely favourable embrace of British rule by Hong Kongers and Singaporeans is not mentioned here as an uncritical apology for colonialism, but it is to recognise the importance of how exogenously imported institutions may either be rejected or received locally depending on indigenous conditions. Scholars have shown how institutions imposed by foreign actors often fail to take hold due to a lack of appreciation of the local conditions (Boettke et al., Citation2008; Boettke & Nicoara, Citation2015). What occurred in this case was a uniquely permissive tabula rasa that allowed the political vision of the British to be realised and reproduce over time. In the years that followed, a local Chinese-centric community emerged and developed practices, norms and governance institutions that closely interacted with imported British institutions.

4.1. Shared interests and values

Chinese immigrants played a vital role in institutional development in both colonies. They did not just dominate numerically (see Supplementary Data) but are well known for their economic motivation and business prowess. These migrants not only excelled in key sectors such as mercantile trading, artisanal crafts, and finance, but also formed business networks that continue to dominate the Asian economy today (Mackie, Citation1998; Brown, Citation2000; Gerke and Menkhoff, Citation2003). It is unsurprising that the Anglo-Chinese relationship was grounded on mutual economic interest.

More importantly, there was a shared cultural convergence over the dignity of commerce. Nineteenth century Britain possessed a strong classical liberal ethos that emphasised free trade and bourgeois values (McCloskey, Citation2010). That this was never perfectly practised is beside the point; what matters is that there was a clear consciousness in the British psyche that perceived empire through this perspective. Understandably, it was once said that Hong Kong was ‘not a place for conquest or acquisition’, but ‘the most hopeful place for the commerce of Britain and the world at large’ (Welsh, Citation1993, p. 320). These ‘bourgeois values’ include the importance of work ethic, thrift, and the accumulation of wealth – values that formed part of the Western story of development. Coincidentally, these values resonated with the Chinese immigrant community that coalesced in both city-states, a trend that comports with a general pattern of immigrant entrepreneurs flourishing in places where entrepreneurial liberty and dignity exist (Nicoara, Citation2021). These migrants were primarily motivated by economic gain, grounded in their dream of becoming rich and buttressed by a confidence in upward social mobility. As Edwin Lee (Citation1991, p. 252) has said, ‘a Chinese man might have to work long years before he realised any improvement in his financial position, but the beauty is that he would go on working in pursuit of his dreams no matter how long it took.’

Chinese material values are based on a Confucian outlook prizing a strong work ethic, motivating the individual to work hard, save, persevere, and acquire wealth and status. In other words, wealth and status achieved through hard work, acumen, and discipline are believed to be honourable, bringing merit to the individual, family, clan, and lineage (Redding, Citation1990). Sociological research has documented how ‘for this group of people, becoming an entrepreneur almost seemed like a mission’ (Chan & Chiang, Citation1994, p. 45). Put differently, the Confucian emphasis on social honour was bestowed on those who pursued entrepreneurship and wealth creation, which bears a striking resemblance to the bourgeois virtues said to animate Western capitalist development.

British Malaya provides an important comparative. There, Chinese immigration never matched the extent seen in Singapore (see Supplementary Data), and various Islamic ‘sultanates’ retained political power before and even after, the British arrival. The cultural convergence in Singapore never took hold in Malaya. If Singapore’s governance was based on an Anglo-Chinese collaboration, Malaya’s was based on an Anglo-Malay collaboration under ‘indirect rule’. The problem is that while in Singapore the Chinese enjoyed both economic and political power under the British, power was divided in Malaya between the minority Chinese who were economically dominant vs the majority Malays who were politically dominant. Consequently, in Singapore there was widespread social acceptance of global capitalism which continued after World War 2. Leading historian Constance Turnbull declared that modern Singapore is ‘traced back to the imposition of free trade and British control, and to a decisive break with Malay traditions’ (Hack, Citation2012, p. 19). However, in Malaya, the Chinese-Malay tension sowed the seeds for fractious ethnic politics till present day, and a pervasive belief in independent Malaysia in the need for protectionism to shield indigenous peoples from globalising forces—a common trend in Southeast Asia except Singapore (Owen, Citation1999, pp. 167–171).

4.2. Chinese elites as bridging social capital

The mechanism that explains the historical persistence and institutional reproduction of colonial governance was the role that the immigrant Chinese played as ‘bridging social capital’. Specifically, they acted as an institutional intermediary which connected the formal layers of British rule with the local Chinese community. In the early years of British rule, the Chinese communities had their own informal governance mechanisms of dispute resolution, community welfare and the like, constituting a ‘distinct world’ from the official British structures that had been imposed. Over time however, this gulf was closed in a process of ‘institutional melding’, facilitated by Anglo-Chinese collaboration.

The importance of these Chinese elites is a result of several factors. First, they became wealthy, partly due to their abovementioned values, their efforts, and also due to the opportunities provided by the British. One of the unintended consequences of British rule was the spread of English education through Christian missionary activity. Due to early Christian activism and the British desire to spread civilizing values, English became a medium of instruction. In particular, the Morrison Education Society in Hong Kong provided an education to Chinese like the prominent Tong Brothers (Smith, Citation1985).

Second, their wealth and English-orientation allowed them to rise to social prominence, which in turn translated into political capital. These Chinese elites enjoyed careers as interpreters, government clerks, advisors, and compradors. Importantly, this outcome was never intended by the British colonial officials who arrived but was an unintended consequence they could not have foreseen. The emergence of this class, ‘created a man that stood between two cultures, a man who was not altogether at home either. He was not wholly in the Chinese model, nor was he altogether Western. This dual aspect…enabled him to fill a needed place in the meeting of the Chinese nation with foreigners promoting trade and commerce’ (Munn, Citation2005, p. 10).

These Chinese elites were not mere intermediaries but were recognised within the formal structures of British governance, and over time, were central in forging a distinct Anglo-Chinese framework in both countries. Without this ‘bridge’, the economic exchange, which thrived in the colonial era, would not have been possible. This is best demonstrated by two specific intermediating institutions: the ‘agency house’ and ‘comprador system’ which formed the bedrock of the colonial capitalist economy.

Agency houses and compradors were intermediating institutions that linked the British and Chinese, forming the basis for Hong Kong and Singapore to be considered Anglo-Chinese joint ventures. The agency house was an organisation which helped British and European merchants sell their surplus goods abroad and to indigenous merchants on a commission basis. These firms had evolved spontaneously to fill that need and were operated by indigenous merchants who were agents of overseas manufacturers (Wong, Citation1991; Brown, Citation1994, p. 65). This institution was not only critical for the development of connecting Singapore to the international division of labour, but also tied local and overseas merchants together institutionally. Prominent agency houses include Jardine and Matheson in Hong Kong, and Guthrie & Co., and Alexander Johnston & Co. in Singapore.

The agency house lacked information about the supply, quality, and creditworthiness of the indigenous traders of Straits produce—the principal consumers of imported manufactured goods—and so needed to rely on Chinese traders as middlemen. In the early years where formal property protection was under-developed, informal Chinese business networks played a significant role as intermediaries. The international traders in agency houses had to rely on an informal institution called the ‘comprador system’. The comprador was a well-respected and wealthy Chinese merchant and a trade facilitator who provided a credit function for individual Chinese merchants and their overseas counterparts by reducing the default risk. This made otherwise uncertain business deals possible.

The importance of the link between the agency house and the comprador should be recognised, for in their absence, the two-way trade in manufactured goods that the economy relied on would have been limited. Their ‘relationship of interdependence contributed to the flourishing of an entrepôt trade and the evolution of Singapore into an international port’ (Chan & Ng, Citation2001, p. 41). The growing prosperity of Chinese compradors also led to the establishment of local banking institutions and large Chinese banks, providing much needed capital to the trade economy which still dominates the local banking industry today (Tan, Citation1961; Lee, Citation1974).

4.3. King’s Chinese in Singapore

Chinese leaders were not mere intermediaries, but also held vital political positions that inter-linked both the formal British authority and the social structures of indigenous communities. The economic wealth of leading Chinese entrepreneurs and their motivation for heightened moral standing translated into great political influence in the community. The wealthy Chinese entrepreneurs in Singapore, Seah Eu Chin and Tan Kim Seng, are prime examples; both were given key political positions and shaped legal institutions. They also gained membership in the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, an important forum that decided on trade policy matters (Yen, Citation2014, pp. 299–293).

The most significant segment of this community of Chinese merchants in Singapore was an elite class of Chinese leaders: the English-educated, Straits-Chinese, also called the ‘King’s Chinese’. First, they were important in culturally linking the British and the local Chinese. These individuals were Chinese but had been exposed to Western ideas through their education (Yong, Citation1992). Their ability to navigate effectively in both Chinese and British social circles meant that they helped link both groups culturally. They were also important in the endogenous institutional development of Singapore considering that they constituted the political elite, working closely with the British to promote mutual interests (Williams, Citation1962, p. 689).

Penetrating into and then represented in formal bodies, such as the Legislative Council, they also furthered Chinese interests in official circles (Yong, Citation1992). This group included the famous philanthropist Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong-Siang, the first Asian to be knighted and who was critical to the development of Singapore civil society and the early civil service (Yong, Citation1967; Song, Citation1984; Sim, Citation1950). The biggest achievement of this Straits-Chinese faction came in 1959 when they won self-governance for Singapore under the PAP banner (Yong, Citation1992). This Straits-Chinese constituency was the social ‘glue’ that enabled the harmonious interaction of formal British institutions and informal Chinese norms during the colonial era.

Embraced by the British, the commercial interests and immigrant values of the dominant Chinese community could therefore be formally represented, constituting a key mechanism that drove the endogenous evolution of market institutions in Singapore. This coalition of Straits-Chinese elites was responsible for demanding market-based institutions in colonial Singapore, namely, more effective protections of property in formal British courts, English commercial law, and an efficient civil service. In fact, the 1867 colonial constitution, which formalised a civil service and further entrenched English laws in Singapore, was introduced only after much agitation by this merchant class while the Crown was wary of extra financial commitments (Turnbull, Citation2009). Thus, the establishment of market institutions in colonial Singapore were a product of bottom-up evolution, rather than an exogenous imposition.

4.4. Self-governance in Hong Kong

The harmonious British-Chinese linkage was also present in Hong Kong and was especially pronounced due to the high degree of self-governance that the locals enjoyed, with numerous voluntary organisations fulfilling social needs.

One key example is housing. Contrary to many accounts which accord pride of place to the intentional efforts of the colonial government in the 1970s to build public housing, NGOs took the leading position in this regard for most of Hong Kong’s history. Prior to MacLehose’s 1970 reforms, improvements were slow. The gaps in state housing were filled by the church. This included the Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee (CIC), which played a crucial role in the Yaumatei Resettlement projects that aimed to resettle those residing at the Yaumatei typhoon shelters. The government had initially refused to take responsibility for these people (Butenhoff, Citation1999). The CIC thus mobilised for change and filled the gap, and thereby expanded its civil society contributions.

Kaifongs were a form of Chinese-led mutual-aid society that provided social welfare. According to the former Assistant Secretary for Chinese Affairs, these associations plugged the gap in state welfare services (Hayes, Citation1996). Kaifongs first emerged in the immediate post-war period to provide essential social welfare services, especially for the large influx of Chinese refugees. They were also critical providers of humanitarian aid and developed necessary medical infrastructure that formed the subsequent backbone of welfare provision in Hong Kong (Hodge, Citation1972).

A famous case study of Chinese self-governance that has been the subject of much research is the Tung Wah hospital, which was crucial in the provision of public health services because it met needs that were unfulfilled by the government. Medical historian Chan-Yeung (Citation2019) showed that it arguably did more than the government in Hong Kong’s early years in caring for the sick and destitute. This hospital not only provided medical care, but also acted as bridges between the Chinese and the colonialists. Tung Wah was also instrumental in many aspects of Hong Kong society, including education, culture, and business (Smith, Citation1976). The hospital’s rich history facilitated important economic, political, and cultural networks, concomitantly reinforcing its role as an important social institution.

Being pillars of the community, they served as mediators between the Chinese population and the British state. Yip et al. (Citation2018) identified various instances in which the Tung Wah Group had demonstrated close links with the government. These included acting as communicators between the refugees and the government during the 1950s. So valuable was this partnership that Governor Grantham paid a tribute to them for upholding ‘the great democratic tradition of public service’ (Yip et al., Citation2018, pp. 342–344). Tung Wah epitomises community self-governance. It is one of the numerous Chinese self-governing institutions that contributed to Hong Kong’s development, not only by meeting needs unmet by the state, but also by forging a productive partnership with the British state (Chiu & Lui, Citation2000).

The institutions discussed so far are clearly rooted in liberal principles ascendent in nineteenth century Britain. Self-governance institutions in Hong Kong are rooted in voluntarism, and it is unsurprising that contemporary Hong Kongers retain a strong sense of self-reliance. The key positions held by Chinese elites allowed them to form crucial intermediating institutions, without which the open economic model would not have worked and persisted. Chinese intermediaries, in the language of New Institutional Economics, lowered the transactions costs of economic exchange.

5. State-entrepreneurship divergence

Modern Hong Kong and Singapore today are intimately shaped by their British experience. Their respective institutional trajectories, however, have not been congruent. Instead, the two states witnessed a divergence in the mid-twentieth century where another critical juncture had an impact. Post-war Hong Kong continued its laissez-faire path till 1997 but Singapore ‘grafted’ new developmental state institutions in the years leading up to independence.

Institutional scholars have identified how developments set in motion in one critical juncture may sow the seeds for endogenous change in a subsequent critical juncture (see Capoccia, Citation2016). What was different in Singapore was that the Anglo-Chinese collaboration led to the prominence of one specific faction of Chinese, as compared to in Hong Kong where the Chinese community were more homogenous. Specifically, at the end of World War 2, a political cleavage opened, and pitted the ‘King’s Chinese’, led by Lee Kuan Yew and his People’s Action Party, against traditional community leaders who were predominantly Chinese-speaking, more inward-looking and less modernist in worldview. The outcome of this political contestation took Singapore down a different institutional pathway: one that retained free trade but subsumed under technocratic governance.

The political victory of Lee’s coalition in 1959 led to the gradual establishment of ‘developmental state’ institutions (a process that culminated in 1965 with the achievement of independence), which emphasised a modernist worldview over a traditional one. The Western-educated developmental state elites saw themselves as a technocratic class who would transform Singaporean society through scientistic, rationalist social engineering (Loh, Citation2019). Understandably, these elites also possessed a confidence in economic planning, based on their ‘high level of formal education with more specifically, extensive training in economics’ (Huff, Citation1994, p. 359). This explains their preference for a developmental state model: it was a pragmatic instrument to combine market forces and the wealth it generates, yet subsumed under rational state control.

Crucially, this second critical juncture is the historical origin point for what many have observed as modern Singapore’s weak domestic entrepreneurship. The new developmental state opposed the prevailing domestic businesses of the time, who were typically Chinese small-medium enterprises, as being unsuited to the modern economy. Lee famously stated that ‘the old family business (of the Chinese) is one of the problems of Singapore. It is not so with European or foreign enterprise’ (Josey, Citation1980). The entrepot trade sector, dominated by traditional Chinese firms since the colonial era, were seen as an impediment to the government’s ‘big-push’ industrialization plan and attraction of multinational corporations. Unsurprisingly, the local Chinese enterprises were sidelined, and in some cases persecuted, especially when they opposed government policy.

The state’s opposition to Chinese enterprise was also because the leaders in that sector had a diametrically different vision for Singapore’s future and represented a political competitor that had to be suppressed. These business leaders clashed with the state on a range of disputes involving education and language policy, workers’ rights, and the merger with Malaysia (Thum, Citation2012). Chinese clan societies, called huiguan, and various Chinese business associates were especially targeted (Bellows, Citation1993; The Straits Times, Citation1959). A prominent example involved Ko Teck Kin, President of Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce, who was publicly humiliated after repeatedly defending Chinese as a medium of education in schools and for his opposition to industrialisation in favour of the trade sector. Numerous clashes occurred between 1959 and 1966 and caused the traditional Chinese power base to eventually be ‘marginalised politically, socially, culturally and economically’ (Visscher, Citation2002, p. 140).

The nascent developmental state’s desire to consolidate political hegemony meant that it must suppress competing Chinese enterprises and their political base, but its reliance on performance legitimacy also means it remains wedded to a high reliance on economic openness. Singapore as we know it today is a unique hybrid of both the market and developmental state traditions, a melding of two historical critical junctures.

Post-war Hong Kong saw no similar push towards decolonisation and thus no challenge to the prevailing British mode of governance, which was essentially continued. Crucially, the colonial state chose not to play a ‘directive’ role in the economy as an entrepreneurial substitute in the way Singapore did. This divergence explains why in the academic literature today, Hong Kong is celebrated for its vibrant entrepreneurship, which is tepid in Singapore (see Cheang, Citation2022).

Post-war Hong Kong’s vibrant entrepreneurship originated in the massive influx of immigrants who fled Mainland China, to escape Chinese communism, famines, and political upheaval. Many were from Shanghai who had a track record of industrial experience (Wong, Citation1988). They brought with them their industrial knowledge, connections, and capital into Hong Kong. Many of these immigrants were upper-class Chinese capitalists with considerable business pedigree, a feature that fuelled post-war Hong Kong’s market-driven industrialisation. In a striking echo of history, these Shanghainese immigrants were a ‘new type of Chinese people who could speak and write English fluently and were familiar with Western culture’ which made them attractive partners of colonial administrators (Goodstadt, Citation2005, p. 10). Additionally, Wong Siu-Lun’s extensive interviews (1988) with Shanghai industrialists detected a self-selection effect, such that the most resourceful and resilient of them were the ones who eventually settled in Hong Kong, cementing their economic dominance.

Coupled with the inflow of industrial capital, these new immigrants were responsible for contributing to Hong Kong’s post-war economic take-off. Notably, Hong Kong’s industrialisation, which saw the rise of manufacturing, textiles, and consumer electronics industries, was achieved not through state initiatives as in Singapore, but unexpected immigration, like in earlier times. The picture that emerges from this is that while industrialisation occurred in both Singapore and Hong Kong, the former achieved it through top-down socio-economic engineering, where the industrial structure was forcefully altered, while the latter achieved it spontaneously (Yu, Citation1998). This distinction is crucial, because it forms the historical basis for why even though both city-states are generally open economies, Singapore’s capitalism, unlike Hong Kong’s, is a top-down variant with the state playing a central role.

6. Conclusion

This article has presented a historical institutionalist account of Hong Kong and Singapore’s political economy. Political decisions made in two critical junctures, the early nineteenth century during the British arrival, and the post-war aftermath, have cast a long shadow on institutional development. In the first critical juncture, the importation of British governance had to a positive cycle of open economic growth and Chinese immigration which built on itself. Contra colonial and post-colonial scholars, I insist that both the Chinese and British are equally important in shaping institutional development. The collaborative Anglo-Chinese relationship facilitated trade & exchange and forged a modern layer of governance that lasted till the post-war period.

The second critical juncture disrupted this equilibrium and saw Hong Kong persisting in its previous path, with no pressure for change, while Singapore experienced a process of ‘institutional grafting’, whereby a new layer of developmental state institutions supplemented its previous trade-based economic system. The Singaporean King’s Chinese, who in the earlier period were British partners, achieved political dominance and imposed a state-led, MNC-heavy industrial strategy at the expense of traditional Chinese enterprise.

My article is not merely a historical recounting but contributes considerable nuance to contemporary debates over the role of the state in East Asia’s development. Both liberal and statist accounts may be critiqued and fruitfully synthesised. Developmental state accounts typically point to the extensive industrial policy practised by East Asia and how intrusive state intervention is necessary for development. This view has a grain of truth but will struggle to account for the fact industrial change was achieved in Hong Kong through adaptive Chinese entrepreneurs who, in a bottom-up process altered the economic structure. Additionally, this position overemphasises the heroic actions undertaken by developmental elites such as in Singapore, but downplays the considerably high base that development had started from – as seen from abovementioned consumer class and vibrant advertising industry that had been forged.

My argument more strongly cuts against the liberal position. This camp is right to highlight the fact that both Singapore and Hong Kong are the most open economies in the world. What the economic freedom indices–which economic liberals heavily draw from – cannot elucidate is the way this open economic model is a historical legacy from British colonialism. The historical embeddedness of Hong Kong and Singapore’s capitalism tempers the many overzealous calls for them to be emulated. My historical analysis also reveals the complex, Janus-faced nature of Singapore’s political economy, with a general openness to the foreign sector layered under a technocratic state that has extensively shaped domestic enterprise. The historical account here explains the paradox of Singapore: a high-growth capitalist economy, but one that also suffers from problems of weak domestic entrepreneurship that numerous scholars have pointed out.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (394.2 KB)Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Hanniel Lim for his research and editorial assistance in this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Colonialism persisted in Hong Kong till 1997 but ended in Singapore in 1965 when it became sovereign.

References

- Andaya, B. W. (1992). Political development between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Cambridge history of Southeast Asia (Vol. I, pp. 402–459). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Audretsch, D. B., & Fiedler, A. (2022). Does the entrepreneurial state crowd out entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 60, 1–17.

- Balasingamchow, Y-M. (2018). Introduction. In A. Patkar (Ed.), Between the lines: Early print advertising in Singapore, 1830s–1960s (pp. 2–19). Singapore: National Library Board.

- Bastin, J. (2009). Letters and books of Sir Stamford Raffles. Singapore: Didier Millet.

- Bellows, T. J. (1993). The Singapore polity: Community, leadership, and institutions. Asian Journal of Political Science, 1(1), 113–132. doi:10.1080/02185379308434020

- Boettke, P., & Nicoara, O. (2015). What have we learned from the collapse of Communism? In P. Boettke & C. Coyne (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Austrian Economics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Boettke, P., Coyne, C., & Leeson, P. (2008). Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 67(2), 331–358. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2008.00573.x

- Brown, R. (1994). Capital and entrepreneurship in South-East Asia. London, UK: Macmillan Press.

- Brown, R. (2000). Chinese big business and the wealth of Asian nations. London, UK: Palgrave.

- Butenhoff, L. (1999). Social movements and political reform in Hong Kong. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Capoccia, G. (2016). Critical Junctures. In O. Fioretos, T. G. Falleti, & A. Sheingate (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chan, K., & Chiang, S. (1994). Stepping out: The making of Chinese entrepreneurs. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Chan, K., & Ng, B. (2001). Singapore. In T. Gomez & M. Hsiao (Eds.), Chinese business in Southeast Asia (pp. 38–61). Richmond, VA: Curzon Press.

- Chang, H. J. (2011). Reply to the comments on ‘Institutions and economic development: theory, policy and history’. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(4), 595–613. doi:10.1017/S174413741100035X

- Chan-Yeung, M. (2019). A medical history of Hong Kong: 1942–2015. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Cheang, B. (2022). What can industrial policy do? Evidence from Singapore. Review of Austrian Economics, 1–34. doi:10.1007/s11138-022-00589-6

- Chiu, S. W., & Lui, T. L. (2000). The dynamics of social movements in Hong Kong: Real and financial linkages and the prospects for currency union. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Chu, Y. W. (2016). The Asian developmental state: Reexaminations and new departures. New York, NY: Springer.

- Collis, M. (2009). Raffles: The definitive biography. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.

- Colonial Office. (1871, February). 129/149 Petition from the Chinese community of Hong Kong. London, UK.

- Endacott, G. (1973). A history of Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Fioretos, O., Falleti, T. G., & Sheingate, A. (2016). Historical institutionalism in political science. In O. Fioretos, T. G. Falleti, & A. Sheingate (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Fraser, J. (1962). Housing estates in Hong Kong. Ekistics, 11(68), 39–41.

- Gerke, S., & Menkhoff, T. (2003). Chinese entrepreneurship and Asian business networks. London, UK: Routledge.

- Gomez, E. (2005). The state, governance, and corruption in Malaysia. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Corruption and good governance in Asia. London, UK: Routledge.

- Goodstadt, L. (2005). Uneasy partners: The conflict between public interest and private profit in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Gordon, G. H. (1843). [Letter to H. Pottinger]. Records of the Colonial Office (COI129/3). London, UK: Colonial Office.

- Guan, K. C., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T. Y. (2019). Seven hundred years: A history of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia.

- Hack, K. (2012). Framing Singapore’s history. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Studying Singapore’s past: C.M. Turnbull and the history of modern Singapore (pp. 17–64). Singapore: NUS Press.

- Haggard, S. (2004). Institutions and growth in East Asia. Studies in Comparative International Development, 38(4), 53–81. doi:10.1007/BF02686328

- Hayes, J. (1996). Friends and teachers: Hong Kong and its people 1953–87. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Hayes, J. (2015). Hong Kong Island Before 1841. In J. Carroll & C.-K. Mark (Eds.), Critical readings on the modern history of Hong Kong (Vol. 2, pp. 549–580). Koninklijke Brill.

- Hodge, P. (1972). Urban community development in Hong Kong. Community Development Journal, 7(3), 154–164. doi:10.1093/cdj/7.3.154

- Huff, W. (1994). The economic growth of Singapore. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ileto, R. (1992). Religion and anti-colonial movements. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Cambridge history of Southeast Asia (Vol. II, pp. 197–248). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Josey, A. (1980). Lee Kuan Yew, the crucial years. Singapore: Times Books International.

- Kaushik, P. D. (1985). ECONOMIC CREED OF THE POST INDEPENDENCE CONGRESS: THE NEHRU-INDIRA PHASE. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 474–486.

- Kong, L., & Sinha, V. (2015). Food, foodways and foodscapes: Culture, community and consumption in post-colonial Singapore. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Kuo, E. (1980). The sociolinguistic situation in Singapore. In E. Afrendas & E. Kuo (Eds.), Language and society in Singapore (pp. 175–202). Singapore: Singapore University Press.

- Labouchere, H. (1856). [Letter to J. Bowring]. London, UK: Records of the Colonial Office (COI129/55).

- Lange, M., Mahoney, J., & Vom Hau, M. (2006). Colonialism and development: A comparative analysis of Spanish and British colonies. American Journal of Sociology, 111(5), 1412–1462. doi:10.1086/499510

- Latham, A. J. (1994). The dynamics of intra-Asian trade, 1868–1913: The great entrepots of Singapore and Hong Kong. In A. J. H. Latham & Heita Kawakatsu (Eds.), Japanese Industrialization and the Asian Economy (pp. 145–171). London: Routledge.

- Lee, E. (1991). Community, family and household. In E. Chew & E. Lee (Eds.), A history of Singapore (pp. 242–267). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, S.-Y. (1974). The monetary and banking development of Singapore and Malaysia. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

- Lim, L. (1983). Singapore’s success: The myth of the free market economy. Asian Survey, 23(6), 752–764. doi:10.2307/2644389

- Loh, K. S. (2019). Albert Winsemius and the transnational origins of high modernist governance in Singapore. In L. Z. Rahim & M. Barr (Eds.), The limtis of authoritarian governance in Singapore’s developmental state (pp. 71–91). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mackie, J. (1998). Business success among Southeast Asian Chinese: The role of culture, values, and social structures. In R. Hefner (Ed.), Market cultures: Society and morality in the new Asian capitalisms (pp. 129–146). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- MacPherson, K. L. (1998). Asian department stores. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

- McCloskey, D. (2010). Bourgeois dignity: Why economics can’t explain the modern world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Mitchell, D. (2017). The recipe for Singapore’s prosperity. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/commentary/recipe-singapores-prosperity.

- Monnery, N. (2017). Architect of prosperity: Sir John Cowperthwaite and the making of Hong Kong. London, UK: London Publishing Partnership.

- Morse, H. B. (1910). The international relations of the Chinese empire. Shanghai, CN: Kelly and Walsh.

- Munn, C. (2005). Introduction. In C. Smith (Ed.), Chinese Christians - Elites, middlemen and the church in Hong Kong (pp. 1–12). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Newbold, T. (1839). Political and statistical account of the British settlements in the Straits of Malacca. London, UK: John Murray.

- Nicoara, O. (2021). The comparative liberty-Dignity context of innovative immigrant entrepreneurship. In A. John, & D. W. Thomas (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and the market process (pp. 123–149). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Owen, N. (1999). Economic and social change. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Cambridge history of Southeast Asia (Vol. II, pp. 139–200). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Prime, P. B. (2012). Utilizing FDI to stay ahead: The case of Singapore. Studies in Comparative International Development, 47(2), 139–160. doi:10.1007/s12116-012-9113-8

- Rahn, R. (2014). Economic freedom versus big government. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/commentary/economic-freedom-versus-big-government

- Raffles, S., & Hooker, B. (1968). Raffles’ Singapore regulations—1823. Malaya Law Review, 10(2), 248–291.

- Redding, G. (1990). The spirit of Chinese capitalism. New York, NY: De Gruyter.

- Saw, S.-H. (2012). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Sayer, G. (1980). Hong Kong, 1841–1862: Birth, adolescence, and coming of age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Sim, V. (1950). Biographies of prominent Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: Nan Kok Publication.

- Smith, C. (1976). Notes on Tung Wah hospital, Hong Kong. Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 16, 263–280.

- Smith, C. (1985). Chinese Christians: Elites, middlemen, and the church in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Soifer, H. D. (2012). The causal logic of critical junctures. Comparative Political Studies, 45(12), 1572–1597. doi:10.1177/0010414012463902

- Song, O. (1984). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Stanley, F. (1843). [Letter to H. Pottinger]. London, UK: Records of the Colonial Office (COI129/2).

- Tan, E. (1961). The Chinese banks incorporated in Singapore and Malaya. In T. Silcock (Ed.), Readings in Malayan economics. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press.

- Tarulevicz, N. (2013). Eating her curries and kway: A cultural history of food in Singapore. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- The Straits Times (1959). PAP wants all Chinese clan groups abolished. Retrieved from https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19591110-1.2.7

- Thum, P. (2012). The limitations of monolingual history. In N. Tarling (Ed.), Studying Singapore’s past: CM Turnbull and the history of modern Singapore (pp. 98–120). Singapore: NUS Press.

- Tilman, R. (1989). The Political leadership: Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP team. In K. S. Sandhu, & P. Wheatley (Eds.), Management of success (pp. 53–69). Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

- Trocki, C. (1994). Political structures in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In N. Tarling (Ed.), The Cambridge history of Southeast Asia. (Vol. 2, pp. 79–130). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Turnbull, C. M. (2009). A history of Singapore, 1819–2005. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Visscher, S. (2002). Business, ethnicity and the state: The representational relationship of the Singapore Chinese chamber of commerce and the state. Retrieved from https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:research.vu.nl:publications%2F60208f34-2264-49b1-953e-7f6f9ecbed47.

- Welsh, F. (1993). A history of Hong Kong. London, UK: HarperCollins.

- Wharton, C. (2015). Advertising: Critical approaches. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Whitaker, J. (2011). The department store: History, design, display. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- White, L. (2012). The clash of economic ideas. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, L. (1962). The dynamism of early Singapore. Second biennial conference proceedings. Chinese Taipei, China: International Association of Historians of Asia.

- Wong, G. (2018). The modern Malayan Home. In A. Patkar (Ed.), Between the lines: Early print advertising in Singapore, 1830s–1960s (pp. 118–137). Singapore: National Library Board.

- Wong, K.-L. (1991). Commercial growth before the second world war. In E. Chew & L. Edwin (Eds.), A history of Singapore (pp. 41–65). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Wong, S.-L. (1988). Emigrant entrepreneurs: Shanghai industrialists in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- World Bank (2022). GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$) - Hong Kong SAR, China, Singapore [Line graph]. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=HK-SG.

- Yen, C-h. (2014). Ethnic Chinese business in Asia: History, culture and business enterprise. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Yip, K-C., Wong, M., & Leung, Y. (2018). Documentary history of public health in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

- Yong, C. (1967). Chinese leadership in nineteenth-century Singapore. Journal of the Island Society, 1(1), 1–18.

- Yong, C. (1992). Chinese leadership and power in colonial Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International.

- Yu, T. (1998). Adaptive entrepreneurship and the economic development of Hong Kong. World Development, 26(5), 897–911. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00013-8

Appendix

Table A1. Brief description of the six articles of the 1823 Raffles’ regulations

Table A2. Primary archival sources of British statements announcing free trade policy orientation in Hong Kong