?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Compulsory schooling laws are often suggested as a means of combating youth crime, but little is known about how effective they are in emerging economies. Using the exogenous changes in compulsory high school enrolment after the 2009 Brazilian Constitutional Amendment 59, we investigate its impact on youth crime indices, violent and less violent ones. We compared municipalities that received federal funding to increase high school enrolment with those that did not, using difference-in-difference models to estimate the effects on selected youth crime indices. Our findings suggest that the Amendment had little or no effects on reducing youth crime. We observe small crime reduction when the incapacitation effects of the Amendment were largely outweighed by the negative effects of sudden overcrowding in classrooms with overburdened teachers providing inadequate supervision, and insufficient crime monitoring in public schools with shorter school hours. Adverse effects of overcrowding were worse in poor municipalities with more disadvantaged students and fewer resources that exactly balanced out the incapacitation effects, producing zero effects on crime. The effectiveness of compulsory schooling laws in reducing youth crime thus depends on the balance between the incapacitation effects and overcrowding effects.

1. Introduction

Researchers have suggested that compulsory schooling laws (CSL) could be effective in reducing crime, based on successful implementations in the United States, UK, and Sweden (Hjalmarsson, Holmlund, & Lindquist, Citation2015; Lochner & Moretti, Citation2004; Machin, Marie, & Vujić, Citation2011). However, for CSL to generate a positive impact, schools need to function well with adequate classroom space and quality teachers so that classes are not over-crowded, students are closely supervised, teaching and learning quality are not compromised. Without these conditions, schools could potentially become a breeding ground for crime (Billings, Deming, & Ross, Citation2016; Jacob & Lefgren, Citation2003), for example, through social interactions and conflicts within crowded school premises (for example, Glaeser, Sacerdote, & Scheinkman, Citation1996). The success of CSL is, therefore, not guaranteed, especially in countries with crowded public schools, overburdened teachers and shorter school hours. In this study, we aim to investigate the impact of CSL on violent youth crime in Brazilian municipalities following the introduction of compulsory high schooling for 15–17 year-olds that occurred after a constitutional amendment in November 2009.

Brazil is an important case in point. It is a major example of an emerging economy that faces significant challenges in its public education system. These challenges include overcrowded classrooms, overworked teachers, multiple daily sessions with shorter school hours (Bruns, Evans, & Luque, Citation2012; Cavalcanti, Guimarães, & Sampaio, Citation2010; Nardi, Cunha, Bizarro, & Dell’Aglio, Citation2012), and a high incidence of youth crime at school (Murray, Cerqueira, & Kahn, Citation2013; Reichenheim et al., Citation2011; World Health Organization, Citation2016). In 2009, the government made a constitutional amendment to increase mandatory schooling from 6–14 years old to 4–17 years old. The Amendment required collaboration between state authorities and municipalities until 2016, under the National Education Plan, with technical and financial assistance from the federal government to the states and municipalities as per Article 212 (see Section 2). We focus on compulsory high schooling of 15–17 year-olds after the Amendment to examine its effects on youth crime.

Using various official sources, we build a unique municipality-level annual panel database for 5560 Brazilian municipalities from 2006 to 2013. We do not extend the sample to 2016 because all municipalities were treated by then. A ‘Treated’ municipality is defined as one that had received additional federal educational transfers and increased high school enrolment during 2010–2013 (post-Amendment) relative to its value in 2009; the rest are treated as the control group.Footnote1 The introduction of the federal Amendment is unlikely to be influenced by municipalities since high schools are governed by the states. Additionally, there is little coordination (horizontal and vertical) between the different levels of government (Abrucio, Sano, & Sydow, Citation2010); so the municipal and state education secretaries responsible for implementing the Amendment are unlikely to influence the state police force in charge of crime prevention policies; the treatment is, therefore, likely to be uncorrelated to the level of youth crimes in the municipality.

Since crime data are not available specifically for 15–17 year-olds, we use 15–19 year-olds as the relevant age group. We used the Brazilian Health Ministry data on violence-related deaths among 15–19 year-olds as our key outcomes to address the absence of reliable crime data (Cardia, Adorno, & Poleto, Citation2003). Selected crime indices include 15–19 deaths by assault, deaths by gun, and their sum, labelled as violent deaths. We also consider less violent aggression related hospitalisation measures. We construct the crime level in logs and the rates per 10,000 15–19 population. We use a difference-in-difference (DD) model to compare the selected crime indices (levels and rates) between treated and control municipalities before (2006–2009) and after (2010–2013) adopting the Amendment, thus deriving the impact of CSL.

Since the Amendment could be implemented until 2016, it is possible that the sample treated municipalities did not adopt it randomly during 2010–2013. To address this potential endogeneity of adoption, we include the municipality fixed effects that would account for the municipality-level unobserved factors, for example, the distance of the municipality from the state capital proxying close link/monitoring by the state. There may still remain some time-varying municipality level unobserved factors. In order to minimise this omitted variable bias, we conduct various robustness tests: (a) rule out pre-Amendment trends; (b) include additional control variables including state-level unobserved trends; (c) eliminate known competing explanations; (d) eliminate omitted confounding factors using impact threshold analysis. Nevertheless, we cannot guarantee complete elimination of all potential sources of bias.

Results indicate that the Amendment has been associated with a small reduction in 15–19 gun and assault deaths when measured in the logarithm of total deaths on each account; the treated municipalities experienced two to three percentage points lower deaths due to guns or assault and four percentage points for violent deaths after 2009. However, this trend does not hold true for crime rates, probably highlighting the limited variation of the rates (given low levels of crime); also, non-linear nature of the relationship between treatment and crime could be better captured by log(crime). The treatment effect is not significant for less violent crimes measured by 15–19 aggression related hospitalisation indices (log and rate) or when using treatment intensity that accounts for overcrowding more precisely than the binary treatment variable. The results remain consistent even when municipalities with own policing, own high schooling, or those located in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area with additional crime-fighting policies are excluded. We also identify some variations in the effects of the Amendment on gun and assault deaths by gender, population size, crime level, degree of urbanisation, and poverty.

In the absence of any evidence of increased incentives (employment/income) or additional policing in treated municipalities, the results can only be explained by the incapacitation effect of the Amendment since it ensured that high school students were held in schools during school hours. However, the benefits of incapacitation may be outweighed partially or fully by adverse effects of sudden overcrowding in already crowded classes with overburdened teachers providing inadequate class supervision and crime monitoring in public schools with shorter school hours. Whether the Amendment was effective to reduce youth crime thus depends on the relative magnitude of these two effects: youth crime falls if incapacitation effects are larger than adverse effects of overcrowding. However, if these two effects exactly balance each other out, there will be no crime reduction. While wealthier municipalities with more resources were better able to minimise the adverse effects of overcrowding and tackle youth crime even as class size grew, resource-constrained poor municipalities with more disadvantaged/overaged students were unable to do so; they witnessed no improvement in youth crime after 2009.

Our analysis integrates various strands of the literature. Studies on economic deterrents of crime have shown that CSL reduces crime in developed countries (Beatton, Kidd, Machin, & Sarkar, Citation2016; Hjalmarsson et al., Citation2015; Lochner & Moretti, Citation2004; Machin et al., Citation2011; Meghir, Palme, & Schnabel, Citation2012). On the other hand, existing studies mainly from the US document that education may increase the earnings from crime (for example, Levitt & Lochner, Citation2001). Bell, Costa, and Machin (Citation2016) find crime reduction effects of CSL was higher for the black relative to the white in the United States. We find that the size of crime reduction after CSL is negligible relative to existing studies.Footnote2

Focusing on emerging economies, Berthelon and Kruger (Citation2011) found a lower incidence of risky adolescent behaviour after a reform that extended the school day in Chile. Chioda, Mello, and Soares (Citation2016) report that the 2008 extension of Bolsa Família to ensure CSL of 15–17 year-olds had significantly reduced crime in São Paulo municipality because there was a cash transfer incentive. The 2009 Amendment did not offer any such incentive.

Existing studies highlight the role of neighbourhood interactions on crime (Damm & Dustmann, Citation2014; Glaeser et al., Citation1996; Moreira et al., Citation2013). Jacob and Lefgren (Citation2003) showed that school incapacitation did not lower all crimes because of a lack of supervised school activities. Better school quality is associated with fewer serious crimes and fewer days spent in incarceration in the United States (Deming, Citation2011) while the concentration of disadvantaged youths in a school may breed criminal networks within school premises (Billings et al., Citation2016). Crime may decline if chronically underperforming schools are closed in Philadelphia (Steinberg, Ukert, & MacDonald, Citation2019). Our finding that the efficacy of CSL in reducing crime is contingent on the size of the incapacitation effects relative to adverse effects of overcrowding after CSL in Brazil adds to this literature.

There are several ways in which our study differs from previous research. Firstly, we focus on crime committed by young people, rather than looking at overall crime rates as some previous studies have done. Secondly, we expand on Chioda et al. (Citation2016) study of youth crime in São Paulo, by examining youth crime across many Brazilian municipalities, taking advantage of the regional variation in crime across the country. Thirdly, we use a modified version of CSL, which differs from the versions used by Berthelon and Kruger (Citation2011) and Chioda et al. (Citation2016), and is more similar to the successful CSL in the UK and the United States. Using the 2009 Brazilian Amendment, we explain why it failed to achieve the expected reduction in youth crime.

The paper is developed as follows. Section 2 provides the information on the implementation of the Amendment; Section 3 describes the data and explains the empirical strategy. Section 4 analyses the results and the final section concludes.

2. Implementation of the Amendment

While Brazil has been able to widen access to primary and high schools, the quality of its schools is low (see supplementary materials section). Common problems include overcrowding in classes, two or more school shifts with shorter school days than in other countries, overburdened teachers, drug use and anti-social behaviour, and exposition of youths to violence (Moreira et al., Citation2013). About 40 per cent of high school age youth drop out (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021), who are susceptible to various criminal activities. Tackling youth crime thus remains a policy priority of the government (World Bank, Citation2013).Footnote3

2.1. Administration of the Amendment

The Brazilian Constitution has offered successive legal provisions for securing the right to access primary and secondary education. Amendment 59 of 2009 increased the duration of compulsory schooling to age 4 to 17 years, requiring that the states and municipalities complete the progressive extension by 2016. Previous mandatory schooling age was 6 to 14 years.

The adoption of Amendment 59 required allocating more resources to ensure that all 4–17 year-olds attend school as enrolments rose. Article 212 of Amendment 59/2009 stipulates that the national government must allocate a minimum of 18 per cent of tax revenues, including transfers, annually for education, while the states, the federal district, and municipalities must allocate at least 25 per cent. With decentralised governance, most federal funds are directly given to the municipalities. If a municipality overseeing primary and middle schools wishes to comply with the Amendment, it must also work with the state responsible for high schools to increase enrolments for 15–17 year-olds, as the municipality receives most of this funding from the state.

The implementation of compulsory education for children aged 4–17 years in public schools was monitored by the Federal Government, with the Public Ministry responsible for conducting a census to ensure compliance. The Constitution of 1988 (art. 208, § § 1° e 2°), the Law of guidelines and base of 1996 (Law no 9394 of December 20 of 1996), and the Law no 12,796 of 2013 all regulated the punishment for municipalities that failed to comply with the rule. After 2016, both public institutions and parents could be punished for failing to abide by Amendment 59, as required by Law no 12,796 of 2013. Additionally, the Child and Adolescent Statute, Law no 8.069 of 1990, and the Brazilian penal code also specify punishment for parents who do not enrol their children in school.

3. Data and empirical strategy

We compiled an annual dataset of 5560 Brazilian municipalities for 2006–2013 from several official sources (see ). This is because the municipalities could inflate the enrolment figures prior to 2006. We excluded 2014–2016 because all municipalities become treated by 2016.

Given widespread age-grade distortion in Brazil, many 18–19 year-olds often continue to attend high schools (Bruns et al., Citation2012), thus justifying our focus on the 15- to 19-year age group. We consider the following violence-related deaths among 15–19 year-olds available from the DATASUS information system of the Health Ministry: (a) death by assaults, (b) death by guns, (c) aggregation of (a) and (b) to construct a composite index of violent deaths. We take natural logarithms of violent crime (a)–(c) in our analysis; the latter allows us to account for any non-linearity in the relationships between the outcomes and the treatment. We also convert violent crime levels (a)–(c) into the corresponding youth crime rates per 10,000 of 15- to 19-year population, thus standardising the crime levels. Additionally, we consider less violent crime indices about aggression-related hospitalisation – both logs and rates. summarises the descriptive statistics, indicating the extent of missing information, especially for crime indices, as well as the inter-municipal variations in these variables.

3.1. Treatment variable and its transparency

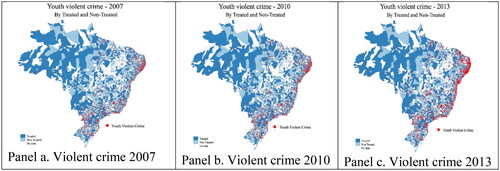

Adoption of the 2009 Amendment meant an increase in high school enrolment funded by federal transfers to the municipality. We use a binary treatment variable labelled Treated’: the variable takes a value 1 if a municipality had experienced an increase in 15–19 high school enrolment and also received additional federal transfers during 2010–2013 (relative to 2009); it is zero otherwise. Supplementary Figure S1 rules out changes in 15–19 population in treated/control municipalities after 2009. Sample high school enrolment had increased in 53.6 per cent of municipalities between 2010–2013 and 97 per cent of these municipalities had received additional federal transfers for different levels of schooling, giving rise to a mean value of Treated 52.4. shows the inter-municipal variation in the incidence of violent youth crime in treated and control municipalities in 2007, 2010, and 2013. Darker (lighter) blue indicates treated (control) municipalities while the red circles show the violent youth crime. Even though there appear to be minimal changes in youth crime over time, they demonstrate significant regional variations across the country (also see means and standard deviations of 15–19 crime and enrolment figures in ).

By Amendment 59, municipalities with higher 15–19 population are more likely to experience greater high school enrolment. To test this, we regress Treated on the 15–19 municipality population along with state dummies, year dummies and State Year dummies. We also test if the effect of the 15–19 population on the likelihood of being treated is higher in municipalities where the Mayor and the Governor are allied (see Section 2), indicated by a binary variable taking a value 1 if the Mayor’s party is in alliance with that of the state Governor.

The estimated coefficient of the logarithm of 15–19 population in column (1) is positive and statistically significant (), thus confirming a direct and statistically significant correspondence between 15–19 population and being Treated in the full sample. A comparison of the corresponding estimates in columns (2)–(3) shows that the average marginal effect of an additional 15–19 youth is about four percentage points higher for allied (0.211) than non-allied (0.172) municipalities, thus highlighting the role of Mayor-Governor alliance in adopting the Amendment.

3.2. Tests of identifying assumptions

Since the consistency of DD estimates is based on the assumption of parallel trends between treatment and control municipalities, we follow McCrary (Citation2008) to test this and regress selected youth crime indices (both logs and rates) on Treated, year dummies and also their interactions Treated Yeart, t = 2006,…, 2013; a test of parallel trends requires that the estimated interaction coefficients are statistically insignificant in the pre-2010 years. Using the year 2006 as the reference group, the Supplementary Table S1 confirms this for most outcomes except for log(assault deaths) in 2008; though it is weakly significant at a 10 per cent level. Furthermore, the joint tests of significance of the interaction terms for the pre-2010 years using an F-test validate the parallel trends between treated and control municipalities for all outcomes before 2009.

Second, using an event study approach, we test if there are pre-trends in the outcome variables in the years before the treatment date 2009. Following Borusyak and Jaravel (Citation2017), we define Kit = t – Ei (E being the event date) denote the ‘relative time’—the number of years relative to the event date 2009. The indicator variable for being treated can therefore be written as:

(1)

(1)

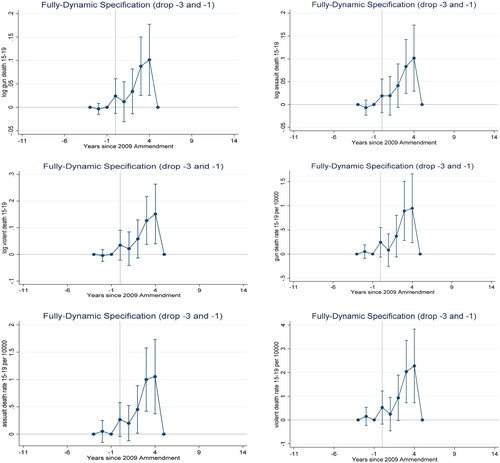

A common way to check for pre-trends in outcome Y is to plot the path of γˆk before and after the treatment, as summarised in (various panels) for selected crime indices, logs and rates. There is no obvious pre-trends in any outcome in . Furthermore, we conduct F-tests as follows. Start from the fully dynamic EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) for any Y and drop any two terms corresponding to k1, k2 < 0 pertaining to pre-event years (semi-dynamic specification). This is the minimum number of restrictions for point identification to pin down a constant and a linear term in Kit. The F-test compares the residual sums of squares under the semi-dynamic and fully dynamic specification. We choose k= −3, −1 corresponding to years 2006 and 2008 (both before 2009). F-statistics for all the outcomes are large and statistically significant at least at 5 per cent levels,Footnote4 indicating that we reject the null (that is, fully dynamic specification) in favour of the semi-dynamic specification, thus over-ruling the presence of any pre-trend in treatment.

Since policing is under Brazil’s state secretary of security provision, it is unlikely that municipal policing had changed in the treated municipalities in the post-Amendment years- we provide some evidence. The municipal police dummy takes a value 1 if the municipality has its own police force; it is zero otherwise. Only 13 per cent of all sample municipalities maintained their own municipal policing, which polices specific buildings but does not fight crime on the streets. The estimates, summarised in column (1) of Supplementary Table S2, suggest that Treated*Yeart, t = 2001….2013 dummies remain insignificant for all t, thus validating our conjecture.

3.3. Empirical model

Having established the identifying conditions in our sample, we shall now estimate the following difference-in-difference model of youth crime indices Cijt – gun deaths, assault deaths, and also violent deaths (logs and rates), in municipality i located in state j in year t (t = 2006,…, 2013) as follows:

(2)

(2)

We also consider less violent aggression related youth hospitalisation index for 15–19 year-olds (see Section 4.1.3) as alternative crime indices. Here Treated = 1 if there is an increase in enrolment and federal transfers (relative to 2009) in i-th municipality in year t where t> =2010 and 0 otherwise. Post is a second binary variable that takes a value 1 for year> =2010 and 0 otherwise. Municipality level fixed effects (Mi) would account for the unobserved municipality-level time-invariant factors (for example, the distance of the municipality from the state capital as a proxy for close link with the state authority) that may indirectly influence the selected crime indices. Since the states govern high schools, we include state-level time-trends SjTt to account for state-level unobserved time trends, for example, any change in state policy that may also influence municipality level crime indices.

The set of control variables X includes various time-varying municipality characteristics to minimise omitted variable bias. First, we include if the mayor’s party is the same as the President’s party, expecting that this may induce the municipality to adopt the federal Amendment early. Second, we include a 15-plus illiteracy rate expecting municipalities with higher illiteracy may be more likely to adopt the Amendment early. Third, we include GDP per capita, Gini index, inter-municipal transport and other communication services, presence of municipal internet services, number of public health clinics, number of public libraries, municipal policing, and number of public sports facilities that may influence the supply of crime. Lack of income and employment opportunities may boost the likelihood of crime. Access to transport/communication services may facilitate access to jobs, thereby reducing the proneness to crime. New transport/communication may also provide new ways of committing crimes. Access to health facilities and public libraries may facilitate quality education, thereby raising the costs of committing crime. Municipalities with own policing may further enhance the cost of committing crime.

Identification is ensured in a number of ways. First, the municipalities could not influence the timing of the introduction of the 2009 Amendment by the federal government. Second, there is lack of coordination between state and municipal education secretaries implementing the Amendment and the state secretary of security controlling crime (Abrucio et al., Citation2010). Third, the coordination between the states and municipalities was crucial for the Amendment’s implementation because the municipalities were the main recipients of federal funds allocated for this purpose. The latter may indicate that the federal funds received by the treated municipalities could be correlated with some socioeconomic characteristics that could also influence the crime outcomes for reasons other than the treatment. Supplementary Table S3 highlights some key differences between treated and control municipalities, thus inducing us to augment the set of control X further to ensure exogeneity of the treatment: we include log of 15- to 19-year-old population, mayor being aligned with the state governor, the governor being aligned with the president, share of public expenditure, fraction of public expenditure on education and health (as a share of GDP), number of Bolsa Familia recipients.

To test the robustness of our treatment group, Treated, we also construct alternative treatment variables: (i) net treatment variable, Treated Net, that takes a value 1 if there is an increase in the high school enrolment net of high school dropout and an increase in federal educational transfers during 2010–2013 relative to the year 2009; it is 0 otherwise. (ii) In contrast, a continuous Treatment Intensity variable considers the size of the annual increase in high school enrolment rate (along with an increase in federal transfers) in the treated municipalities during 2010–2013 relative to that in 2009. The continuous treatment intensity index may thus provide a more accurate measure of overcrowding compared to the binary indices. presents descriptive statistics for these variables: the value of the variable varies between 1 and 31 and its skewness is 4.49.

While we include municipality fixed effects, there may still remain some municipality level time-varying unobserved factors that we try to eliminate in Section 4.2 – we drop municipalities with own police, municipalities that run high schools and also the Rio municipalities that launched additional crime prevention programmes to tackle gangs of armed drug traffickers. We also conduct the impact threshold estimates to eliminate any bias arising from unobservable confounding factors. Our analyses have thus been designed to minimise the potential for any estimation bias. Nevertheless, we cannot guarantee the complete elimination of all potential sources of bias.

The coefficient of interest is α3, which yields the differential effect of the Amendment on selected crime indices among treated (relative to control) municipalities after 2009.

All standard errors are clustered at the municipality level to minimise any autocorrelation of errors across years for a given municipality.

4. Empirical findings and discussion

4.1. Baseline estimates

shows both OLS (panel 1) and municipality FE (panel 2) estimates of α3 (the coefficient of interest of the interaction term, TreatedPost) as per EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) for DD estimates of crime rates per 10,000 15–19 year-olds (columns 1–3) and those of the logarithm of the total crimes (columns 4–6).

Table 1. Transparency of the treatment variable

Table 2. Difference-in-difference estimates for crime indicators in rates and levels – OLS and municipality FE estimates, 2006–2013

Ceteris paribus, the estimated coefficients of PostTreated, for both rates and log crime indices, are all negative using OLS and FE but statistically significant only for log(crime) indices. However, the size of the FE estimates tends to be somewhat bigger in absolute terms in panel 2, indicating the downward biases of the OLS estimates due to municipality-level omitted factors. Municipality FE estimates remain our preferred estimates as argued in Section 3.3: treated (relative to control) municipalities experienced between two and four percentage points lower violent crimes related deaths due to guns and/or assault after adopting the Amendment. Panel 3 estimates include additional controls, while panel 4 estimates use panel 2 controls, but panel 3 sample for each outcome to facilitate direct comparison. Both confirm the robustness of the panel 2 estimates. Overall, log(crime) indices work better to capture the treatment effect than crime rates, partly because levels and variations in crime rates are limited; also logs capture the possible nonlinear effect of the treatment on crime.

All standard errors are clustered at the municipality level in ; however, since states largely provide high schooling, Supplementary Table S4 confirms that baseline estimates of panel 2 hold even after clustering the standard errors at the state level.

4.1.1. Alternative treatment variables

We employ two more treatment variables- Treated Net and Treated Intensity. These estimates (with municipality FE) as per EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) are summarised in panels 1 and 2 of Supplementary Table S5. Ceteris paribus, the estimated coefficient of the interaction term Post

Treated is negative and statistically significant for various log(crime indices) using Treated Net (panel 1), indicating a significant reduction of log crime indices in treated municipalities after the 2009 Amendment. As before, the crime rates estimates remain statistically insignificant.

Considering the Treated Intensity variable (panel 2), the estimated coefficient of PostTreated is negative for all three log(crime) indices, and the absolute size of the treatment effects appear bigger but statistically significant only for log(assault deaths). Treated Intensity takes into consideration the enrolment size indicating extent of overcrowding in classes after the 2009 Amendment. These weaker results contrast that obtained using the binary treatment variables, Treated or Treated Net.

4.1.2. Effects of CSL on youth hospitalisation and suicides

In the absence of direct information on youth participation in organised/unorganised crime, Supplementary Table S6 shows the estimates of less violent aggression related hospitalisation among 15–19 year-olds. This is negative but remains statistically insignificant for both rate and log of hospitalisation, documenting that the Amendment was more effective in lowering violent youth crimes only.

Second, we consider the effects of the CSL on suicides, both rates and logs. While Young, Sweeting, and Ellaway (Citation2011) find that regular school attendance may lower the incidence of suicides, Supplementary Table S7 does not show any significant effect of CSL on suicides.

4.1.3. Placebo tests

We use a fake treatment year 2008, before the 2009 introduction of the Amendment and assess its impact on all violent crime indices. Estimates shown in Supplementary Table S8 confirm that the fake treatment year does not produce any significant effect on any crime indices (rates and logs) either in the full sample (panel 1) or in the truncated sample 2006–2009 (panel 2).

4.2. Eliminating competing explanations

We try our best to ensure that our estimates are not biased because of any unobserved confounding events. First, we drop the municipalities with own police force from our sample. Results shown in panel 1 of Supplementary Table S9 confirm the similarity of these estimates with those in (panel 2): the estimates of PostTreated are negative and statistically significant only for log crime indices.

There are 21 sample municipalities in Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area that launched the Police Pacification Unit (UPP for short) in 2008. These municipalities received pacifying police forces and innovative and aggressive actions to deal with the urban cycle of violence to tackle gangs of armed drug traffickers. Estimates in panel 2 of Supplementary Table S9 confirm the similarity of these estimates to panel 2 estimates.

Since 27 per cent of municipalities also provide high school education, we test the robustness of our baseline estimates by dropping these – baseline estimates are confirmed in panel 3 of Supplementary Table S9.

4.2.1. Test of unobserved confounding factors

We have controlled for many municipality characteristics, including municipality and StateYear fixed effects. The treatment effects could still be potentially biased because of any omitted municipality-level time-varying factor, for example, the time-varying unobserved relationship between the municipality and the state/federal level. We, therefore, conduct an impact threshold analysis of unobserved confounding variables (ITCV) following Frank (Citation2000) and Frank, Maroulis, Duong, and Kelcey (Citation2013). We run ITCV for the key explanatory variable Treated

Post in determining various log(crime) indices where the estimated coefficient was statistically significant. This calculates the percentage of observations for each potentially confounding variable to invalidate the current estimates of Treated

Post for any outcome, determining the strength of a hypothetical confounding variable.

We obtained the following threshold estimates for log(crime) indices as per panel 2. (i) To invalidate the inference for log(gun deaths), 21.67 per cent (5375) cases would have to be replaced with cases for which there is an effect of 0. (ii) To invalidate the inference for log(assault deaths), 29.69 per cent (8269) cases would have to be replaced with cases for which there is an effect of 0. (iii) To invalidate the inference for log(violent deaths), 24.99 per cent (5888) cases would have to be replaced with cases for which there is an effect of 0. For each outcome variable, these ITCV estimates exceed the threshold by a significant margin (between 20% and 30%), giving further confidence in our treatment effects.

4.3. Possible explanations

CSL is expected to lower crime through boosting incentives and/or through incapacitation effects during school hours. There were no cash transfers or increase in under-17 employment rates in the treated municipalities after 2009 (see Section 4.2), thus ruling out any incentive effects of the Amendment. As such, the observed treatment effects of CSL after 2009 can be solely attributed to the incapacitation effect. However, the benefits of incapacitation may partly be outweighed by adverse effects of sudden overcrowding in already crowded classes with overburdened teachers providing inadequate class supervision and crime monitoring in public schools with shorter school hours.

To examine this further, we assess the impact of the Amendment on various school quality indices in treated municipalities: (1) class size proxied by the number of secondary students in day and night schools per class; (2) number of secondary night school students as a share of total secondary students; (3) fail rates at the secondary level, and (4) age-grade distortion at the secondary level, which is an index of grade repetition in Brazil.

Panel 1 of shows that the estimated coefficients of TreatedPost are positive and significant for class size (day and night), night class size, and age-grade distortion index, indicating pressure on class size (both day and night schools). Most public schools that operate in shifts have shorter school hours; night school students have all day available to work or commit crimes. The addition of overaged disadvantaged students in already overcrowded day and night public schools (operating over the recommended class size of 20) may worsen school quality if teachers, already overburdened with non-teaching tasks (OECD, 2021) and teaching in two or three shifts are unable to provide extra supervision and crime monitoring needed. Accordingly, after 2009, disadvantaged youths in schools may use social interactions or conflicts to promote school violence, as suggested by Malta et al.’s (Citation2014). Violence at school may not only stimulate more violent behaviour and physical damage, but also adversely affect student performance and social development. This has the potential to partially or completely negate the favorable impact of the Amendment's incapacitation measures in deterring crime, thus resulting in less crime reduction relative to existing studies.Footnote5 If the benefits of incapacitation partially outweigh the adverse effects of overcrowding, youth crime is likely to fall, which we observe for logarithm of violent youth crime indices. If the benefits of incapacitation exactly compensate the adverse effects of overcrowding, youth crime may remain unchanged. This is observed for hospitalisation indices and also when we replace the binary treatment variable by treatment intensity variable. There is, however, no evidence that the adverse effects of overcrowding outweigh the benefits of incapacitation in our sample so that youth crime increases after CSL.

Table 3. Treatment effects on school quality indices – municipality FE estimates

4.4. Heterogeneous effects in poor/non-poor municipalities

To understand the nature of the overcrowding effects of CSL, we further explore the differential effects of the Amendment in poor and non-poor municipalities. We follow the Health Ministry’s definition to classify a municipality as poor if its income per capita is less than half of the national minimum wage. It is non-poor otherwise.

Supplementary Table S10 shows that poor (relative to non-poor) municipalities have significantly bigger class sizes, less graduate teachers, higher dropout, higher age-grade distortion index, and more disadvantaged Bolsa Familia members. Poor municipalities not only spend less on education, but are also less likely to have a municipal education board that monitors school performance or a safety board that oversees school safety and security. Poor municipalities have lower income/employment opportunities too that lowers the incentive effects of CSL. Considering these varying demand and supply factors for schooling, it is anticipated that wealthier communities will experience a more significant decrease in crime after CSL than their less affluent counterparts – we test this below.

Panel (1) of highlights that the crime reduction effects of CSL are negative for both poor and non-poor municipalities, but turn out to be significant only in non-poor municipalities, indicating that the poor municipalities fail to reap any crime reduction after the Amendment, supporting our conjecture.

Table 4. Heterogeneous impact on youth crime by poor/non-poor municipalities

We dig it further to assess whether these observed effects can be attributed to higher class size – the average number of students per class in both day and night schools in municipalities- in poor and non-poor municipalities. Panel 2 of shows that poor municipalities fail to realise any crime reduction irrespective of class size – smaller or larger than the median class size. However, non-poor municipalities are able to lower youth crime (see panel 3) after 2009 even with larger than median class size.

To explain these results, we consider that shows the differences in school quality between poor and non-poor municipalities. The Treated × Post estimates in panels 2 and 3 of indicate that both treated poor and non-poor municipalities experienced increases in class size and age-grade distortion after 2009, though these effects were larger in poor municipalities, as supported by the F-tests. In other words, inadequate class supervision and crime monitoring may induce more social interaction and conflicts among more disadvantaged students in poor municipalities. The differential effectiveness of the Amendment in reducing crime in poor and non-poor municipalities again depends on the balance between the benefits of incapacitation effects and the adverse effects of overcrowding.

4.5. Other heterogeneous effects

Finally, we consider how the effects of the Amendment differ by: (a) gender; (b) low/high population; (c) low/high urban population; and (d) low/high crime, defined by the corresponding medians in cases (b)–(d).

We focus only on log(crime) estimates since crime rate estimates are rarely statistically significant. It is evident from panel (1) of Supplementary Table S11 that the over-all crime reduction effects of the treatment are seen only for male crime as incidence of female crime is rather rare. Panel (2) shows that treatment effects are negative and significant for the more populous municipalities, but remain insignificant for the less populous ones, as expected. Panel (3) shows the estimates for more/less urbanised municipalities, respectively, classified by urban population shares >50 per cent and < =50 per cent. Negative and statistically significant crime reduction effects of the Amendment are found only for the more urbanised municipalities. Splitting the sample into low/high 2009 violent crime levels, panel (4) reports significant crime reduction effects only for more crime-prone municipalities. By virtue of Supplementary Table S10, municipalities with larger populations, higher levels of urbanisation, and higher levels of crime are less likely to be poor and are more likely to benefit from incapacitation effects (net of adverse overcrowding effects) after CSL, thus experiencing a reduction in youth crime.

5. Concluding remarks

The paper investigates the impact of the CSL on various youth crime levels and rates, using the exogenous variation in high school enrolment caused by the Constitutional Amendment 59 in 2009. Results show weak or no impact of CSL on youth crime reduction in our sample. It is documented that after 2009, there were no additional crime prevention policies or incentives, and therefore the observed changes in youth crime can be attributed to the incapacitation effect of CSL. The benefits of incapacitation of CSL was, however, partially negated by the sudden overcrowding of already packed classes and overwhelmed teachers who could not effectively supervise and monitor the students during the shorter school hours in public schools. This results in smaller than anticipated reduction in youth crime, which was largely driven by the experience of wealthier municipalities. However, the benefits of incapacitation were exactly balanced out by the adverse effects of overcrowding in case of impoverished municipalities so that there was no reduction in youth crime after 2009. This leads to the conclusion that policies such as CSL should be carefully implemented, taking into account the social and economic context of the schools and municipalities they serve.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (609.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We are much grateful to the Managing Editor and two anonymous referees of the Journal for very constructive feedback on earlier drafts. We thank the University Global Partnership Network (UGPN) between the University of Surrey and the University of São Paulo for funding this research and Thais Souza for excellent research assistance. We have benefitted greatly from discussions with Valdir Assef Jr., Siddhartha Bandyopadhyay, Carlo Devillanova, Reynaldo Fernandes, Jeff Grogger, Ana Kassouf, Stephen Machin, Olivier Marie, Leandro Piquet, Bibhas Saha, Yared Seid, Wang-Sheng Lee, Katrin Sommerfeld, Patrick Button and seminar/workshop participants at the University of São Paulo Crime Workshop, Surrey-UGPN conference on Crime and Public policy interventions, CSAE Annual Conference in Oxford, IZA-Sole conference as well as other Universities for valuable feedback on earlier versions of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We experiment with both binary and continuous treatment variables.

2 Lochner and Moretti (Citation2004) report that one extra year of schooling reduces violent and property crime by 11 per cent to 12 per cent. Machin et al. (Citation2011) find that a one-year increase in average schooling levels reduces conviction rates for property crime by 20 per cent to 30 per cent and violent crime by roughly one-third to one half among males.

3 See Supplementary Material section.

4 F-statistics are 3.80, 4.34, and 3.89, respectively, for logarithm of gun deaths, assault deaths, and violent deaths; the corresponding F-stat for crime rates are 3.47, 4.61, and 4.16, respectively.

5 See note 2.

References

- Abrucio, F., Sano, H., & Sydow, C. (2010). Radiografia do associativismo territorial brasileiro: tendências, desafios e impactos sobre as regiões metropolitanas [Radiography of Brazilian territorial associations: trends, challenges and impacts on metropolitan regions]. In F. Magalhães (Ed.), Regiões Metropolitanas No Brasil [Metropolitan regions in Brazil] (pp. 197–234). Brasilia: Interamerican Development Bank.

- Beatton, T., Kidd, M. P., Machin, S., & Sarkar, D. (2016). Larrikin youth: New evidence on crime and schooling (CEP Discussion Paper, CEPDP1456). London: Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

- Bell, B., Costa, R., & Machin, S. (2016). Crime, compulsory schooling laws and education. Economics of Education Review, 54, 214–226. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.09.007

- Berthelon, M., & Kruger, D. (2011). Risky behavior among youth: Incapacitation effects of school on adolescent motherhood and crime in Chile. Journal of Public Economics, 95(1-2), 41–53. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.09.004

- Billings, S., Deming, D., & Ross, S. (2016). Partners in crime: Schools, neighbourhoods and the formation of criminal networks (NBER Working Paper No. 21962). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Borusyak, K., & Jaravel, X. (2017). Revisiting event study designs. Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2826228

- Bruns, B., Evans, D., & Luque, J. (2012). Achieving world-class education in Brazil. mimeo. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/993851468014439962/pdf/656590REPLACEM0hieving0World0Class0.pdf

- Cardia, N., Adorno, S., & Poleto, F. (2003). Homicídio e violação de direitos humanos em São Paulo [Homicide and violation of human rights in São Paulo]. Estudos Avançados, 17(47), 43–73. doi:10.1590/S0103-40142003000100004

- Cavalcanti, T., Guimarães, J., & Sampaio, B. (2010). Barriers to skill acquisition in Brazil: Public and private school students’ performance in a public university entrance exam. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 50 (4), 395–407. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2010.08.001

- Chioda, L., Mello, J., & Soares, R. (2016). Spillovers from conditional cash transfer programs: Bolsa Família and crime in urban Brazil. Economics of Education Review, 54, 306–320. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.04.005

- Damm, A. P., & Dustmann, C. (2014). Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior? American Economic Review, 104(6), 1806–1832. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1806

- Deming, D. J. (2011). Better schools, less crime? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 2063–2115. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr036

- Frank, K. A. (2000). Impact of a confounding variable on a regression coefficient. Sociological Methods & Research, 29(2), 147–194. doi:10.1177/004912410002900200

- Frank, K. A., Maroulis, S. J., Duong, M. Q., & Kelcey, B. M. (2013). What would it take to change an inference? Using Rubin’s causal model to interpret the robustness of causal inferences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 35(4), 437–460. doi:10.3102/0162373713493129

- Glaeser, E. L., Sacerdote, B., & Scheinkman, J. A. (1996). Crime and social interactions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(2), 507–548. doi:10.2307/2946686

- Hjalmarsson, R., Holmlund, H., & Lindquist, M. J. (2015). The effect of education on criminal convictions and incarceration: Causal evidence from micro-data. The Economic Journal, 125(587), 1290–1326. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12204

- Jacob, B., & Lefgren, L. (2003). Are idle hands the devil’s workshop? Incapacitation, concentration and juvenile crime. American Economic Review, 93(5), 1560–1577. doi:10.1257/000282803322655446

- Levitt, S., & Lochner, L. (2001). The determinants of juvenile crime. In J. Gruber (Ed.), Risky behavior among youths: An economic analysis (pp. 327–374). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226309972.003.0008

- Lochner, L., & Moretti, E. (2004). The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American Economic Review, 94(1), 155–189. doi:10.1257/000282804322970751

- Machin, S., Marie, O., & Vujić, S. (2011). The crime reducing effect of education. The Economic Journal, 121(552), 463–484. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02430.x

- Malta, D. C., Porto, D. L., Crespo, C. D., Silva, M. M. A., Andrade, S. S. C. D., Mello, F. C. M. D., … Silva, M. A. I. (2014). Bullying in Brazilian school children: Analysis of the national adolescent school-based health survey (PeNSE 2012). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17(suppl 1), 92–105.

- McCrary, J. (2008). Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 698–714.:10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.005

- Meghir, C., Palme, M., & Schnabel, M. (2012). The effect of education policy on crime: An intergenerational perspective (NBER Working Paper No. 18145). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Moreira, D. P., Vieira, C. J. E. S., Pordeus, A. M. J., Lira, S. V. G., Luna, G. L. M., Silva, J. G., & Machado, M. F. A. S. (2013). Exposição à violência entre adolescentes de uma comunidade de baixa renda no Nordeste do Brasil [Exposure to violence among adolescents in a low-income community in the northeast of Brazil]. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 18 (5), 1273–1282. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232013000500012

- Murray, J., Cerqueira, D. R. D C., & Kahn, T. (2013). Crime and violence in Brazil: Systematic review of time trends, prevalence rates and risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(5), 471–483. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.003

- Nardi, F. L., Cunha, S. M. D., Bizarro, L., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2012). Uso de drogas e comportamento antissocial entre adolescentes de escolas públicas no Brasil [Drug use and antisocial behavior among adolescents attending public schools in Brazil]. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 34(2), 80–86. doi:10.1590/S2237-60892012000200006

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Education policy outlook in Brazil: With a focus on international policies (OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No. 37). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/e97e4f72-en

- Reichenheim, M. E., De Souza, E. R., Moraes, C. L., de Mello Jorge, M. H. P., Da Silva, C. M. F. P., & de Souza Minayo, M. C. (2011). Violence and injuries in Brazil: The effect, progress made, and challenges ahead. Lancet, 377(9781), 1962–1975. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60053-6

- Steinberg, M., Ukert, B., & MacDonald, J. M. (2019). Schools as places of crime? Evidence from closing chronically underperforming schools. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 77, 125–140. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2019.04.001

- World Bank. (2013). Making Brazil safer: Analysing the dynamics of violent crime (mimeo 70764). Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- World Health Organization. (2016). World health statistics 2016: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: Author.

- Young, R., Sweeting, H., & Ellaway, A. (2011). Do schools differ in suicide risk? The influence of school and neighbourhood on attempted suicide, suicidal ideation and self-harm among secondary school pupils. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 874–875. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-874