Abstract

Photoelicitation is a creative and multidimensional visual methodology used to stimulate participant subjectivities and situated knowledges. International development research documenting this method often amounts to methodological ‘how-to’ discussions around procedural ethical considerations (e.g. of consent, confidentiality, anonymity and dissemination). Notwithstanding their instructions and recommendations, scholarship is almost exclusively concerned with ethics with respect to participant produced photographs. Less considered are elaborations around unanticipated ‘ethically important moments’ that occur unexpectedly in the here and now dynamic of researcher-supplied photoelicitation. Appropriately, this article presents a methodological reflection of the author’s unpreparedness for participant confessional stories and emotional responses about identity and racism evoked by INGO fundraising photographs of Black African poverty in a qualitative study with British African diasporic communities. It concludes with a two-pronged recommendation of critical reflexivity as an ethical safeguard whereby researchers 1) interrogate their positionalities, and 2) assess the ethical appropriateness of using photos with audience groups who share racialised identities and relationships with those featured in the fundraising imagery. Here, critical reflexivity is defined as the process through which researchers examine who they are and their role within the research context. While ethical safeguard refers to a certain ethical discernment and responsiveness that guards against some of the potentially harmful implications of ethical unpreparedness.

1. Introduction

A relatively few but growing number of international development scholars and practitioners have commented on and problematised the epistemological and methodological appropriateness, utility and complementarity of photo-visual methodologies compared with more conventional forms of knowledge production/data collection, such as interviews and focus group discussions (see e.g. Kaplan, Citation2005; Dogra, Citation2012; Warrington & Crombie, Citation2017; Ademolu & Warrington, Citation2019; Ademolu, Citation2021). Amidst the heterogeneity of visual methods, one such approach that has received burgeoning attention is photoelicitation. Photoelicitation is the incorporation of photographs or other visual mediums in interviews to generate and contextualise verbal discussion (Collier & Collier, Citation1986). Publications documenting this methodology, while explicating its virtues and pitfalls, largely amount to methodological ‘how-to’ and ‘one ought not to’ discussions around procedural ethics e.g. of informed consent, confidentiality, data protection and photo anonymisation, copyright and dissemination.

Notwithstanding these important insights, scholarship is almost exclusively concerned with ethics with respect to participant-produced photographs. Less considered however are reflexive elaborations around unanticipated ‘ethically important moments’ (Guillemin & Gillam, Citation2004), that occur unexpectedly in the here and now of researcher-supplied photoelicitation research. As such, are we to assume that the risk aversion of committee-approved institutional ethics implicitly confers a blanket preparedness for all ethical issues in photoelicitation inquiries? What are, and how do we understand, situationally-driven ‘ethically important moments’ that arise spontaneously within photoelicitation development studies? How can critical reflexivity be instrumentalised as an anticipatory action to safeguard against, negotiate and process the ethics of photo-use for development researchers? These speculative questions and presumptions undergird the intellectual inquiry of this present article.

The article presents a retrospective methodological reflection of using photoelicitation methodology in a qualitative focus group-based, audience-reception study with UK African Diasporic communities (Ademolu, Citation2018). That is, Black British populations of African heritage—an audience group notably underrepresented in photoelicitation studies. Specifically, using two examples of ethically important moments encountered in this study around identity and racism, it documents and problematises my (un)preparedness for participant confessional stories and emotional responses provoked by INGO (international non-governmental organisation) fundraising photographs of Black African poverty. The selected ethically important moments were those which compelled me to ruminate more than I otherwise would have done on my interactions with, observations of, and assumptions about participants, as well as the overall ethics of the photoelicitation process.

The article’s relevance and contributions are three-fold. First, it provides important and timely methodological elaborations to the transdisciplinary photoelicitation literature, particularly the researcher-supplied approach, in this case, with UK African Diasporic communities. Black African diaspora are not just an underrepresented group that need to be included because of their previous exclusion within research. Rather they are a significant audience group with a distinct relationship to the imagery as the evidence presented in this article shows. Second, by focusing on ethically important moments, the article offers a useful critique for development researchers of ethical issues that might arise unexpectedly in (their) photoelicitation studies. Third and relatedly, it amplifies broader calls to centre critical reflexivity in social science investigations.

This article presents interrelated components that are divided into four sections. First, a brief review of the photoelicitation and visual ethics literature is provided which will highlight contemporary debates and considerations of ethics within international development. Second, applying Guillemin and Gillam’s (Citation2004) notion of ‘ethically important moments’, it then outlines key differences between ‘procedural’ and ‘situational’ ethics. Third, a contextualisation of the research and researcher background follows, leading to the ‘meat’ of this article—the presentation and reflective discussion of impromptu ethical moments involving confessional stories and emotional responses that arose during African Diasporic participant discussions. Fourth, it concludes with a two-pronged recommendation of critical reflexivity as an ‘ethical safeguard’ whereby researchers 1) interrogate their positionalities, and 2) assess the ethical appropriateness of using photos with audience groups who share racialised identities and relationships with those featured in the fundraising imagery.

2. Photoelicitation in development research and ethical considerations

While not new to social science investigations, scholarly documentations (reflective and otherwise) of photography and photographs—printed, digitalised and video—as creative accompaniments to more traditional written and oral forms of empirical study (Harper, Citation2002), remain relatively few and scattered within international development (Warrington, Citation2020; Ademolu, Citation2021). This observation is particularly discernible within the fundraising communications subfield of development scholarship. Among the few that exist, we find a relatively small but burgeoning body of charity sector literature which are largely commissioned reports by development INGOs and policy institutions (see e.g. Young, Citation2012; Flores & Malik, Citation2015; Warrington & Crombie, Citation2017; Girling, 2018; Crombie & Girling, Citation2022) offering critical insights into how donor audiences and so-called beneficiaries of aid receive, understand and engage with international development and humanitarian communications. Notably, there remains an even smaller academic representation in this space (see e.g. Dogra, Citation2012; Ademolu & Warrington, Citation2019; Ademolu, Citation2021).van der Gaag and Nash (Citation1987) Images of Africa, is the earliest and perhaps the most seminal of all these contributions. In the aftermath of 1984 Ethiopian Famine, and the unprecedented media attention it spawned, INGOs undertook a detailed review of their visual communications. Spearheaded by an international research collaboration between UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), and European NGOs—critical examinations of African representation were foregrounded. The Oxfam-sponsored three-part qualitative study shared photographs of poverty campaigns in workshop activities to explore, among other things, UK public thoughts and opinions of Africa.

More recent and similarly noteworthy is The People in the Pictures report commissioned by Save the Children UK (SCUK) (Warrington & Crombie, Citation2017). In an attempt to review its image-making policies and practices, a sample of SCUK’s visual communication materials—fundraising content, online news features, television advertisements and short films—were used in interviews and focus groups in the UK, Jordan, Bangladesh and Niger to solicit public and contributorFootnote1 perspectives on their visual storytelling. Notably, it is important to mention here that this study, unlike previous examples, was perhaps the first time that contributor responses had been sought. As Warrington (ibid: p. v) cautions ‘the debate about representation shouldn’t exclude the very people we are representing’.

Relatedly, What Development Means to Diaspora Communities (Flores & Malik, Citation2015), a bondFootnote2-commissioned research project, incorporated photographs in workshops to examine the thoughts and concerns of three UK-based diaspora communities—British Muslims, British Africans, and London-based Latin Americans aged between 14 and 65 years—on the language and messaging of INGO fundraising communications. While Young’s (Citation2012) comprehensive participatory research completed on behalf of the African and Caribbean Support Organisation Northern Ireland (ASCONI) utilised fundraising communications—such as websites, newsletters and social media communications by INGOs including Concern, Oxfam, Trócaire and SCUK—to explore perceptions of Africa by donor audiences of African heritage in focus groups.

Academics and practitioners alike, both within and beyond the international development field, have lauded and appraised photoelicitation for promoting communication and embodied connections across varied literacies, intelligences and learning differences (Clark-Ibáñez, Citation2004; Hill, Citation2014). Photoelicitation has also been praised for eliciting subconscious and tacit knowledge, especially in combination with Arts and Crafts mixed media such as drawing or collage (Frith & Harcourt, Citation2007; Hall & Mitchell, Citation2008) where this can be somewhat difficult to tease out in written and oral communication alone. Others have shared how photoelicitation stimulates a certain kind of resourcefulness and problem-solving among marginalised populations who lack platforms to articulate their subjectivities (Wang, Citation1999). For instance, Photovoice—a solutions-focused participatory action research (PAR) method and communication/advocacy tool—has received critical attention in the international development field. Photoelicitation is fundamental to many Photovoice projects where participants are encouraged to talk or write about the images they choose to take (for a thoughtful scholar/practitioner in this field see e.g. Fairey, Citation2018). Researchers have used this technique to invite study participants—often children and other populations—to take photographs that identify, discuss and re(add)dress community needs, challenges and priorities. Such approaches have been particularly appealing to development practitioners as they stimulate individual empowerment while advancing a critical dialogue to advocate community-driven social transformation (Wang & Burris, Citation1997; Evans-Agnew & Rosemberg, Citation2016).

Nonetheless, there is appreciable debate and caution from even the most enthusiastic proponents of this approach around the additional complexities of guaranteeing informed consent, confidentiality, relational boundaries and safety (Prins, Citation2010). Scholars in this domain outline good practice and provide visual ethics guidelines concerning the ownership and use of photographs as intellectual property (e.g. Guillemin & Drew, Citation2010); the ethics of online dissemination and communication of participant photos and scholarly publication (e.g. Creighton et al., Citation2018; Tani, Citation2014); and the potential infringement to people’s safety due to increased publicity (e.g. Joanou, Citation2009; Black, Davies, Iskander, & Chambers, Citation2018). Similarly, others have discussed the consent and anonymity of those photographed (e.g. Wang & Redwood-Jones, Citation2001). While Samuels (Citation2004) and Liebenberg (Citation2009) caution against researcher ‘agenda’ and (disproportionate) influence over the analytical interpretation of photographs.

Other publications offer ethical advice on using visual methods with systemically marginalised and oppressed communities and/or those who may require additional protections for visual research, such as those with developmental and intellectual disabilities (e.g. Boxall & Ralph, Citation2009; Hill, Citation2014); people with HIV/AIDS (e.g. Thupayagale‐Tshweneagae & Mokomane, Citation2014); migrants, sexual/gender minorities, youth and substance misusers (e.g. Pittaway, Bartolomei, & Hugman, Citation2010); and global South populations worried about misinterpretations of their photos (e.g. Warrington, Citation2020).

This brief and nonexhaustive list of publications offer important recommendations and contemplations encouraging a certain critical consciousnesses of ethical considerations among practitioners who practice photoelicitation in their projects. However, empirical and conceptual contributions around the ethical nuances involved in the unpredictability of researcher-supplied photoelicitation outside of institutionalised procedures are scant. Among the few who have considered these issues with varying degrees of reflection include Esin and Lounasmaa (Citation2020), who shared the ethical challenges they faced while facilitating visual storytelling workshops in the Calais ‘Jungle’ refugee camp which was comprised of communities from Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and other places. Specifically, they explain the fundamental complexities inherent in balancing a decolonising practice that privileges authorship and ownership with the practicalities of managing the threat of compromising the participants future resettlement in the European Union.

In my review of the literature, the only publication to specifically write about ethically important moments in relation to international development and humanitarian-aid communications, is Warrington (Citation2020). In her chapter contribution for a publication dedicated to the ethics and integrity of visual methodologies, Warrington provides a thoughtful reflective commentary on the ethical decisions and dilemmas encountered during the course of a researcher-supplied photoelicitation project for SCUK. She recounts the unintended ramifications and ‘difficult predictions’ (p. 52), surrounding the use of a selection of printed and online communication materials in interviews and focus groups with The People in the Pictures—i.e. those communities who had contributed their (or child/ren’s) image and story to SCUK content. In particular, Warrington states that ‘in a few cases the images were…a visual reminder of their child’s serious illness, or their own poverty’ which induced a variety of emotional responses in the here and now investigatory moment of photoelicitation.

A few other scholars have commented on the challenges of remaining faithful to Independent Ethics Committees (IEC) at the expense of preparing for impromptu ethical scenarios (e.g. Khanlou & Peter, Citation2005; Mok, Flora, & Tarr, Citation2015). For example, this scholarship has advised that consents and/or protocols might receive IEC approval, even if they unreflectively fail to apply similar ethical precaution around the potentially negative reception and misinterpretation of photos in research. This insightful but limited offering provides a solid pathway for thinking about the murky ethics of photoelicitation. However, considerable attention is almost exclusively on participant-produced material, and specifically in the context of Photovoice. This is as opposed to photographs supplied by the researcher themselves within the context of development research—the focus of this present article.

Moreover, while publications espouse the relevance and application of core ethical principles in the context of IEC to photoelicitation and visual research generally, detailed reflective interrogations of ethics concerning participant emotions, emotional sensitivities and confessional stories are underreported. This is despite the fact that several authors attest to the role and negotiation of emotions (Burkitt, Citation2012), the ‘emotive’ (Holland, Citation2007), ‘emotional work’ (Reed & Ellis, Citation2020) and ‘emotional safety’ (Beale, Cole, Hillege, McMaster, & Nagy, Citation2004) in the relational, intersubjective and often affective nature of research. Emotions are even more pronounced and salient in photoelicitation studies where the use of visual stimuli may prompt intentional and sometimes unintended emotional and embodied connections to memories, confessional accounts and discomfort that are both meaningful and ethically challenging (Collier & Collier, Citation1986; Frith & Harcourt, Citation2007).

Notwithstanding the seriousness of the ethical complexities highlighted in these contributions, there remains an important demand for additional scholarship in this area of enquiry which explicate and advance the status of ethically important moments in international development research utilising photoelicitation. Appropriately, it would be remiss for me not to comment on the lack of literature on photoelicitation in international development. An explanation for this is offered in a series of my personal speculations and observations. 1) the novelty of photoelicitation is such that it is an underutilised method in the field so is yet to gain prominence in international development scholarship. 2) Because of this, practitioners/scholars seldom publish written reflections of the method in international development journals at least. 3) Conversely, examples do exist, however they are largely found in research method/ology journals that are ostensibly more accepting of submissions that raise and answer critical questions around nuanced conceptions of ethics in the selection and use of photographs.

3. ‘Procedural’ versus ‘situational’ ethics

The process of obtaining ethical approval from IEC to undertake research involves a certain consciousness of important ethical considerations. However, even with careful preparation all ethical contingencies cannot be accounted for in fieldwork. A distinction is often made between procedural ethics sometimes referred to as paper ethics (Armstrong, Gelsthorpe, & Crewe, Citation2014) and situational ethics, which Guillemin and Gillam (Citation2004) call ‘ethics in practice’. Generally, the former involves a formal and bureaucratised ethics governance including ethical approval processes and ethical research guidelines. The latter involves navigating ethical issues that arise unpredictably in the research process. Hammersley and Atkinson (Citation2007) advises that IEC often lack a sophisticated understanding of contextual uncertainties within research which almost always place a demand on researchers to account for and problematise ‘context’ in their decisions and interactions in the field. These uncertainties are almost unavoidable. For example, Katz (Citation2006, p. 55) argues that the box-ticking compliance of procedural ethics obfuscates knowing that researchers ‘often encounter people and behaviour they cannot anticipate’. Additionally, reflecting on the limitations of IEC approval relative to the frontline realities of research practice, I (Ademolu, Citation2023a, p. 17) too have argued that:

…even with appropriate pre-fieldwork preparation and an assumed assiduity to all eventualities, it is naïve, perhaps unreasonable to deduce that researchers are subsequently programmed with a certain clairvoyant sensibility of fieldwork, by which they can almost intuitively foretell and forestall the challenges and dynamics of human interaction with a great degree of certainty. Rather the ‘in the moment’ encounters of the research process are not always foreshadowed.

As such, the ethically important moments shared here are ones that are comprehended and problematised through a backward-looking reflection, that is, my a posteriori examination of what has already happened. Notwithstanding Warin’s (Citation2011, p. 82) assertion that ‘a positivist research culture still exerts a powerful influence on the content and style of written publications’, Guillemin and Gillam (Citation2006) advise that methodological transparency of ethical difficulties provides a roadmap of applied knowledge and experience for researchers, especially the novice, to negotiate fieldwork with greater ease of mobility. Importantly, by airing ethically important moments, the utility of critical reflexivity is foregrounded in advocating for researchers to engage in a continuous and iterative process of interrogating who they are and their role within the research context (Guillemin & Gillam, Citation2004).

4. Methodology and researcher background

The ethically important moments presented in this article are exemplified using two cases from a larger audience-reception study involving British African Diasporic communities responding to INGO communications of Black African poverty. Specifically, the study examined the complex and oftentimes contentious relationship(s) of diasporic self-identification and development engagement among first-and-second-generation Nigerians in Southwark, London, and Manchester, England. This was demonstrated in the context of their everyday consumption of African representation in the fundraising advertisements of international development and humanitarian-aid charities (see, Ademolu, Citation2021). My candid experiences of these two cases involving participant confessional stories and emotional responses demonstrate how UK INGO fundraising images have and continue to reinforce and perpetuate racist and culturally insensitive stereotypes. Moreover, these experiences also demonstrate the negative impact this has on UK audiences who share racialised identities with those featured in such fundraising imagery.

The research motivation stemmed from (and has subsequently inspired) a small but burgeoning array of publications and symposiums interested in the distinctiveness of UK African diasporic viewpoints regarding the content, context, impact and ethical appropriateness of INGO communications (see e.g. Young, Citation2012; Flores & Malik, Citation2015; Dillon, Citation2021). This interest sits in tandem with, and are largely informed by, clarion calls for INGOs to be more reflexive about (the politics of) Black racial representation in their photography (Warrington & Crombie, Citation2017; Ademolu, Citation2023b). So too, there is a growing recognition that UK diasporic propensity to engage in global development is in part affected by their latent perceptions of and concerns around INGO fundraising communications portraying their countries and communities of origin in problematic ways (Opoku-Owusu, Citation2003; Wambu, Citation2006; Ademolu & Warrington, Citation2019; Ademolu, Citation2021).

A qualitative methodological approach was used comprised of 7 photoelicitation focus group discussions to examine diasporic reception and interpretation of African representation among a sample of 31 self-identifying British Nigerians. Of the participants, 16 (51%) were women and 15 (49%) men, aged between 18 and 65, with the average age being 30 years. The sample included participants with various levels of education and career phases ranging from university students to those employed in professional and nonprofessional jobs (see Appendix 1). These discussions were conducted between 2015 and 2016 face-to-face in private meeting rooms in local libraries and community organisations. Discussions were semi-structured in format following a series of questions informed by the overarching empirical aims, and audiotaped transcriptions were coded and analysed verbatim using an interpretive description thematic analysis (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, Citation2011).

A set of 8 photos from 8 leading UK INGOs were shared within the focus groups and chosen by purposeful sampling as appropriate for qualitative research (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994). This sampling strategy involved identifying and selecting photographs of Black African poverty exclusively, across the different multi-media communication platforms (e.g. official websites and social media) of a broad range of INGOs. Appropriately, the sample corpus comprised downloaded digital images showing people, settings and situations deemed characteristic of those typically used by popular UK INGOs in their fund/awareness-raising campaigns. To add some temporal context, it is important to note here that the kinds of photos used within the project are still used by the same INGOs as I prepare this manuscript for publication in 2023. However, the on-going debates on visual representation within the international development communications and fundraising sub-field has impacted their frequency and scale compared to more nuanced and contextual preferences.

The study was approved by the University of Manchester, UK. All participants provided informed consent following a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose and the expectations (and limitations) of their participation. As with Moran and Gatwiri (Citation2022, p. 1336), to avoid ‘speaking for the participants’, where possible participant-chosen pseudonyms and direct quotations are used. Relatedly, the photo sample included in this article (total of 3) are, at the request of their original copyright holders, anonymised, with the name of the associated INGO, written captions, image URL and other identifiable details removed. As such, the sample presented here are personal photographed copies of the downloaded and laminated originals used in the group discussions. The remaining 5 photos are not included for various reasons including copyright holders’ ethical policies around archiving ‘dated’ images and a desire to, as one agency cautioned, ‘move on’ from the pictures.

As Stanley and Wise (Citation1990, pp. 157–61) advise, ‘one’s self can’t be left behind. Our consciousness is always the medium through which research occurs’. As such, before this doctoral research my knowledge about photoelicitation was limited having only used photographs in interviews once before as part of my master’s programme dissertation, where its application was not sufficiently informed by methodological literature, or systematic. Instead, photoelicitation and my perception of its cool cachet was romanticised as some shiny new toy (in juxtaposition to the sameness of conventional qualitative methods) for me to amateurishly trial via the guide of my casual self-direction. I therefore lacked a sophisticated appreciation of its methodological promise and its implications for research.

While I had contemplated ethical considerations concerning my personal life, my engagement with research ethics as an academic discourse and practice did not exceed knowing the standard procedural obligations around voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, and protection from harm (Armstrong et al., Citation2014). Neither had I fully considered—let alone prepared for—possible ethically important moments not covered by the procedural safeguards of the IEC. Instead, I approached the study with an almost quixotic optimism, wishing to only abide by my perspicacity of procedural ethics, showing professionalism, respect and openness, with the hope that diasporic members would feel safe and comfortable enough to share their thoughts and experiences with me.

As a London-born, partly SouthwarkFootnote3-raised Black Brit of Nigerian heritage, who at the time was a doctoral student at the University of Manchester, UK, my identity and socialisation conveniently positioned me as an insider with my participants. While this insider status was brought to the attention of my supervisors ahead of data collection, I focused more on my ethnocultural ties to Black British and specifically Nigerian diasporic communities, organisations, as well as my familiarity with the study locations. Nevertheless, neither my supervisors nor I critically reflected on the potential problems, pitfalls and ethical shortcomings of my presumed de-facto insider status, especially for co-ethnic studies like this that are supposedly (more) impressionable to culturally-skewed normative assumptions, expectations and speculative truths (see Ademolu, Citation2023a).

Similarly, although I contemplated my specialist knowledge of and personal frustrations with INGO representations of Black African poverty, the methodological implications of this—e.g. on data and observational interpretations—were heretofore superficially questioned. As such, I did not fully appreciate how the biased and assertive beliefs and attitudes accompanying this might position me as an outsider to my participants.

Certainly, my insider-cum-outsider status illustrates the inevitable differences in identity and socialisation that exists between researchers and participants which impact field relationships. As such, anything that is documented and written by researchers must always be considered a ‘partial truth’ (Clifford, Citation1986). With that said, I am not claiming the objectivity of my observations, interview conversations, or interpretations. To maintain an outward semblance of neutrality is not only empirically delusional but functions to neglect the position of power conferred upon researchers at the time of textual composition and characterises a dishonest attempt to represent participants.

5. Ethical (Un)preparedness in action: photo-elicited confessions and emotions

A few authors have offered recommendations on how to incorporate and present photographs in interviews and group discussions. Notably, Harper (Citation2002, p. 20) emphasised the idea of ‘breaking the frame’, whereby photos are presented from what he describes as an ‘unusual angle’ to encourage participants to comprehend a new awareness of their social reality. Diamond and Hestenes (Citation1996) contributed to breaking the frame in the sequencing of their photo presentation, in which participants—in their study of children’s conceptualisation of various disabilities, were shown different black and white photographs one after the other. While Weinger (Citation1998) presented participants with a set of two contrasting images at a time.

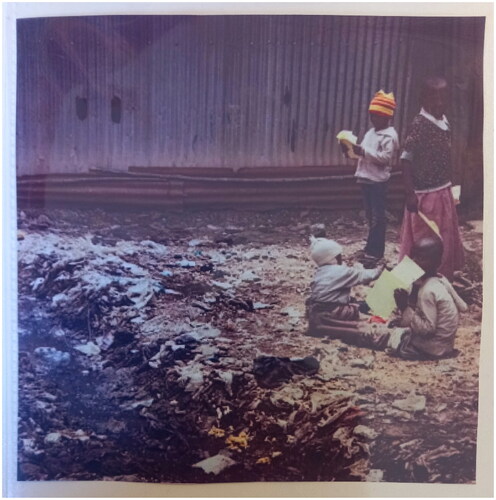

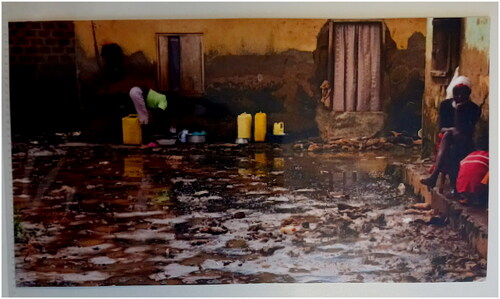

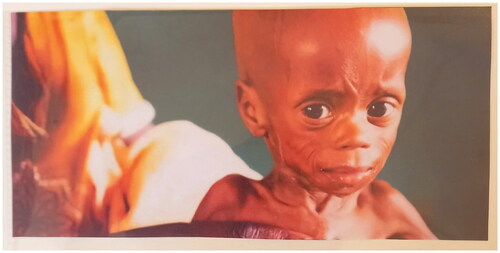

This present study used a set of 8 approximately A5 sized (148x210 mm (15x21cm)) printed, scissor-cut, coloured and laminated fundraising photographs to stimulate diasporic responses to representations of African impoverishment. The photographs included both close-up and distant framings of Black children, families, local communities, livestock and buildings, who/which were positioned and framed within and against agrarian environments, arid climates and urban decay. While ‘breaking the frame’ was not necessarily my motivation in picture selection, the content and form of the photographs nonetheless influenced participants’ reception and interpretation.

All pictures were kept in a document folder within punched plastic wallet sleeves, which at the start of the group discussions I placed at the centre of the small oval-shaped boardroom table. Often without instruction, one self-appointed volunteer from each focus group would empty the wallets and spread out the laminated photos for all participants to see, manoeuvre and inspect—most of the time indiscriminately, sometimes picture-by-picture across the table—reminiscent of scattered playing cards. As such, not only did I observe a certain performative element of photoelicitation in participants’ enthusiastic grand revealing of photographs, but also a tactile-kinaesthetic involvement, encouraging the movement or (man)handling of pictures—the picking-up, placing-down, side-by-side comparing, turning-over and flicking-away. I also saw the physicality, the motion of bodily movement and gestures, where participants sprung to their feet leaving their chairs as they responded to and scrutinised photographs from the vantagepoint of their raised postures and towering eyes. Others circulated the table and roamed the room in prolonged thought or while humming unintelligible sounds of mild irritation. The animatedness—for want of a better word, of participants’ tactile involvement with and corporeal response to the photographs was curious. Even more surprising, however, were the elicitations of confessional stories and emotional responses around issues of identity and racism accompanying their animatedness. These unintended accompaniments offered meaning and a contextual seriousness to participants’ somewhat idiosyncratic forms of engagement in the photoelicitation process.

5.1. Confessions of unreconciled and appropriated identities

As the facilitator, it was particularly interesting to witness the swiftness at which participants almost impulsively problematised, picked-apart, and even sneered at the photographs with reference to theorisations and social commentaries on race and racial identification. At first these discussions amounted to abrupt and highly impassioned utterances of abstract, impersonal thoughts reflecting a combination of serious intellectualism and colloquial informality—something more akin to an academic conference. As such, within this conversational space, race orientated the momentum of the participants’ intellectual critique of the photographs.

Nonetheless, as the photoelicitation sessions progressed towards my questioning of whether participants’ own raced identities affected how they engaged with and negotiated understandings of the photos, discussions became decidedly anecdotal, context specific and contemplative. It was at this precise point that participants seemingly allowed themselves the space and opportunity to be personally and pointedly censorious with their thoughts about the fundraising depictions of Black African poverty. Beyond their more abstract academic evaluations, it was at this juncture of the conversional flow that I observed a tonal and attitudinal shift away from the general impersonal to the affronted personal. Specifically, some participants interpreted the photos as a racist, personal offence, while others suggested that they were some kind of pictorial propaganda mythologising the distinctiveness of their supposed racial and/or ethnocultural inferiority. For the latter, these images then, were essentially a subterfuge or pretext for achieving an ulterior or hidden end, that is, the mischaracterisation of ‘my people’ as Edwin (27, Group 1) put it, referencing the photo below ().

As such, the discourse of race, identity and African representation coalesced in the photoelicitation environment in a way that both spoke to and spoke about participants’ own diasporic selfhood. So much so, that this led to cross-talking interruptions of a staccato and erratic rhythm, where some participants spoke on top of themselves vying for an elbowroom of readiness to express their own personal monologues. From one person to the next, they disclosed psychological conflictions and challenges when viewing photos that, as 25-year-old student Segun described, ‘trivialised Black people like me’, stating:

These pictures here on this table, which we have passed around and looked at…are distorting mirrors, you know those funny, curvy mirrors at the funfair? This is what these pictures are, we Brown folk identify ourselves in them, albeit a grossly misshaped version of who we think ourselves to be. We know what they are saying about Blacks, about Africans, that we are nothing more but beggars, that we are the lowest of all the low and that’s racist, without a doubt. It’s hard to digest all these charity images in front of me, because how do you reconcile with them when we are the very people they are racially caricaturing?

(Group 2)

When I look at these photos, they remind me of some buried insecurities…the pure hatred I had for my skin and who I was…I’m not just Black but…I’m that dark dark African Black, jet-Black and I wanted to do away with that. I wanted to lighten my skin, to be less African I guess, less like these photos you see on Comic ReliefFootnote5 and Save the Children.

(Bethany 48, Group 4)

Something as (outwardly) innocuous as the presentation and sharing of a select few photographs characteristic of those embedded in the UK public consciousness, turned out to have greater resonance and impact for diasporic members. This after the fact realisation was the first of multiple consciousness-raising moments of becoming aware of conflicts and contradictions of diasporic existence in the photoelicitation process. I did not give serious weight to what can be best described as the trans-locational or transportive potential of the photoelicitation environment through which still, square-cropped images, of a detached and unrelated temporal and spatial distinction, opened portals of embodied connections. That is, photo-viewing-and-talking-about arouse diasporic self-referential (and self-interpreting) disclosures of identity bound by relational ties and conditions of exchange.

I would not have fathomed for instance that the commonness of a picture showing people positioned in a water-logged slum dwelling (), conveying the phenomenon of insecure settlements in underdeveloped urban areas excluded from environmental protection, would elicit seemingly unrelated narrations of skin bleaching and identity dissonance.

I found myself navigating the choppiness of uncharted territories regarding the ability for photoelicitation to draw out, call forth and stir up sentiments and sensibilities from the privacy of diasporic minds, into manifestation. Equally eye-opening was how this environment informed compelling admissions poured on the photoelicitation ground without caution and self-censorship. Without sounding more poetical than this discussion already is, these confessional moments unclothed me, leaving me in the nudity of my naive and misguided thoughtlessness that meant I misjudged my preparation. My faithful commitment to IEC bureaucracies limited the ethical consciousness and literacy that photoelicitation required. As such, dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s of the IEC process was only partial groundwork for anticipating the ambivalences of ‘ethically important moments’ (Guillemin & Gillam, Citation2004) in the here and now interaction of photoelicitation.

Relatedly, I had also unintentionally downplayed or underestimated the instructive role of participants’ raced identities in/for how they derived meaning from, and were in turn affected by, photoelicitation. I erroneously speculated that diasporic responses to photographs would merely amount to some form of eye-rolling vexation at INGOs, instead of heavy, detailed narrations of identity issues. As such, my presumptions of annoyed but demure responses were clouded by my own personal annoyances being less acute and sensitive than the participant sample. Unfortunately, my experiences (as a co-ethnic member) were the subjective reference points against which participants were (mis)judged, and which exposed the tunnel vision of my egoic vantage point.

5.2. Emotional memories of racism

Accompanying admissions of self-identities fraught with contradiction were poignant documentations of childhood memories and current encounters of racism. From one intense rendition of taunts, teasing, bullying and physical violence to the next, participants drew on their individual identities as Black, African, Nigerian or an amalgamation of all three in recollections of everyday racism, abuse and discrimination.

While personal to each participant, it was curious how these accumulated stories formed the basis of a collective, and ostensibly commonsensical memory, such that each account shared among the congregation of diasporic individuals within group discussions amplified and legitimatised the other.

19-year-old Ezekiel, for example, recalled how the photographs reminded him of being called a ‘monkey in dungarees’ by a supposed friend when he was 9-years-old. While another participant shared a time that an ‘elderly white neighbour joked that Madonna should adopt me next’—a reference to the global fanfare (at the time) surrounding the transnational adoption of orphaned Black Malawian children by the white American signer, Madonna.

Similarly, 29-year-old data handler Quentin shared:

It was tough growing up as an African…I remember white kids in my estate where I lived used to throw gravel and banana peels at me and mum and make monkey chants. Just awful.

(Group 5)

I was called everything under the sun, even by some well-meaning people who maybe didn’t know better, they called me shoe polish, soot, chimney sweep, bush baby, you name it. This picture took me back to that time, I see myself in it. Even now, as old as I am, I get the odd snide racist comment but certainly nothing on the level of what I received growing up [in Britain]

(Group 3)

Collier and Collier (Citation1986) claim that while associations between past personal traumas or catastrophes and our current selves are not (always) easily made, the stir of emotions when memories are unlatched is one of the most powerful attributes of photoelicitation. They caution, however, that such memories could be invasive and difficult for participants to digest given the latent impact of those encounters. Given this, it was somewhat unfathomable to me before the photoelicitation discussions that participants might share an interpersonal closeness of such magnitude that they found some semblance of themselves and manifestations of (their) racialised trauma in the pictures. As such, these pictures were cultural sites of emotional intensity and relation in which participants almost involuntarily recalled memories of past and current traumas instigated by ‘people who look like me’ (Olaleyi 20, Group 7).

Immanuel’s disclosure—in fact, the emotional recollections of all participants—made me feel personally responsible for unlatching a Pandora’s Box of potential re-trauma, and while there were no tears, the pensiveness of participants’ memories qualified this emotion. Of course, as is expected of all researchers—from novice to experienced—all ethical safety measures and duties of care were observed to protect participants’ wellbeing (Guillemin & Drew, Citation2010). Curiously however, the group discussions engendered a sense of diasporic camaraderie, communion, and healthy interdependence which offered comfort when disclosing traumas aroused from the photos. It is therefore important to consider the possible differences between using photoelicitation in group discussions as opposed to individual interviews. Would these ethical moments be different? Generally, group discussions involve specific ethical issues that are not fully translated to those elicited by individual interviews, and this is further complicated by the use of photoelicitation methodology (Sim & Waterfield, Citation2019). This is due to the unpredictability of the discussion and the interactions among participants. If the photoelicitation discussion group encourages over-disclosure, as it did in my case, this accentuates the problem. As such, emotional responses and trauma are potentially aroused through the influence of collective and collaborative conversation on provocative and/or emotionally-sensitive topics like Black racialised poverty and human vulnerability. This is amplified not just by the public nature of these group conversations but, more importantly, the additional embodied experiences, expressions and relationality generated by a group when they engage with photos that the group all identifies with (Walstra, Citation2020; Church & Quilter, Citation2021). This is not to say, however, that interviews and group discussions are so methodologically worlds apart that similar ethically important moments do not and cannot emerge from the former as it does the latter.

Interestingly, despite feeling responsible for the onslaught of diasporic emotions, I also felt immensely privileged to have been privy to, and trusted with, the confidentialities of the participants’ honest stories. Undoubtedly, the closeness of shared ethnic identities between the participants and I facilitated a safe, comfortable space of relatability and communal familiarity in which these memories were affirmed and normalised. Perhaps this would have been different in discourses between people less closely bound by identity (Clifford, Citation1986). However, it is equally important not to overestimate nor romanticise the potentially positive impact of sharing identities and/or experiences with research participants (Author, 2023).

These ethically important moments were not ethical dilemmas demanding immediate action, in that there was no prescription specifying a right and wrong resolution to problem-presenting scenarios. In keeping with Guillemin and Gillam’s (Citation2004) advice, critical reflexivity in this context nonetheless highlighted critical points, gaps and opportunities in a qualitative photoelicitation study. This not only signalled insufficient ethical preparation above and beyond IEC approval, but it also reinforced the importance of interrogating one’s positionality and of careful photograph selection to develop a nuanced conception of ethics and an ethical sensibility for potential issues emerging from this methodology.

6. Recommendations for international development photoelicitation

Taking important lessons learned from these ethically important moments, it is critical that photoelicitation researchers consider critical reflexivity as an ethical safeguard whereby they (1) problematise their positionalities, and (2) assess the ethical appropriateness of using photos with audience groups who share racialised identities and relationships with those featured in the fundraising imagery.

Appreciating the social dynamics and complexities of social science research—including within the international development discipline—is integral to critical reflexivity. Researcher-supplied photoelicitation methodologies, however, are seldom subject to serious and sustained reflection beyond the procedural safeguards of the IEC. Yet this article has demonstrated the ethical unpredictabilities that arise when researchers select and show photos that trigger emotional responses and possible traumatic recollections. Critical reflexivity is essential here to supplement the limitations of protectiveness offered by procedural ethics, which oftentimes appear out of step or misaligned with the ethical spontaneities and negotiations of social science investigations (Armstrong et al., Citation2014). As such, critical reflexivity is central to how we not only prepare for and actually practice photoelicitation and comes into play in the development field generally where procedural ethics alone are insufficient.

This article offers a methodological reflection as an attempt to revisit and interrogate my past actions, decisions and encounters using research-supplied photoelicitation. However, I caution against unfairly haunting oneself with ruminations about woulda/coulda/shoulda scenarios, where we obsessively reflect, a little longer than we should, on how we might, given different circumstances, account or atone for various mishaps, missteps and missed opportunities. This type of ruminative retrospective review of past research does not necessarily alter or develop future decisions but leads to ‘nonproductive and preservative inaction’ (Freeman, Citation2004, p. 243). By being critically reflective, we can, however, use these experiences and acquired wisdom to behave differently in the future by developing a certain consciousnesses. This consciousness, which should be developed with a proactive and deliberate intention, can help us consider the potential ethical problems of photoelicitation before using the method. Moreover, it can help us consider how to respond to certain scenarios, and understand the reasons behind our responses, even in scenarios that at this stage only be speculated about. In developing this acumen, reflective researchers will be more primed to prepare for and respond appropriately to ethically important moments occurring within photoelicitation.

As such critical reflexivity is not afterthought addendum to our ethical responsibilities but instead should be considered a specific research practice utilised for photoelicitation enquiries. It is therefore an integral part of research culture more broadly. By understanding critical reflexivity in this way, it becomes an ethical safeguard, not in the sense that it is an antidote to all ethical dilemmas, but rather in the way that it cultivates an ethical discernment and responsiveness that guards against some of the potentially harmful implications of unpreparedness. Of course, I am not suggesting here that critical reflexivity grants researchers clairvoyant abilities to predict all future ethically important moments; that would be a fallacious assumption and logically impossible. Rather, development scholars/practitioners using researcher-supplied photoelicitation should be forward-thinking in their assessment of unanticipated ethical scenarios. This includes recognising emotional responses, disclosures and discomfort that might accompany this visual research method.

The unpredictability of fieldwork means that freedom from all such risks is virtually impossible. Understanding that unexpected responses and behaviours from participants (and ourselves) are sometimes part and parcel of development research and, specifically, photoelicitation methodologies, is critical.

Equally important is the need for researchers to take a step back to examine and interrogate their positionalities, to understand who and what they are in the research process and how this is revealed in the planning and conduct of photoelicitation. We are all positioned and sensitised by our intersectional identities, personal experiences and multiple social belongings. These considerations, and the assumptions, prejudices and other subjectivities associated with them, influence the lens of our ‘contemplative eye’ (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992, p. 69), forestalling and/or allowing for certain insights, interactions and interpretations. As documented here, the novice within me failed to take seriously the influence of my ‘co-ethnic’ researcher status and what this meant for my ethical (un)preparedness, racialised normative assumptions, observational interpretations and reactions to ethically important moments.

Finally, critical reflexivity is important for assessing the ethical appropriateness and potential problems of showing fundraising photographs to audiences who share distinct racialised identities and relationships with the imagery. As Warrington (Citation2020, p. 59) cautions, the ‘ethical stakes’ are potentially greater the closer the relationship of participants is to those featured in the image. Within this frame, it is important that researchers recognise that it is not just their own positionality they should scrutinise and account for, but their participants’ too. Indeed, photographs and not neutral, depoliticised material things without context, meaning and impact. Rather, they are cultural sites within which racialised groups such as Black communities of African heritage reference and see themselves, encouraging emotional and traumatic memories and experiences.

In light of this, and in recognition of similar recommendations emerging from Warrington’s (Citation2020) reflective chapter on predicted and unpredicted ethical issues when using photoelicitation, I suggest that researchers ask themselves the following three questions when assessing the likelihood of fundraising photographs eliciting heightened emotional responses and possible trauma for viewers:

Do participants share similar ethnoracialised and cultural identifications with who and what is portrayed in the photo(s)?

Could participants have had similar histories, realities or some other related aspects of their past and present biographies, to the person(s), issues and situations featured?

Might these photos elicit emotional or troubling responses and memories among identifying participants?

7. Conclusion

Photoelicitation is a creative and multidimensional visual methodology used to stimulate participant subjectivities and situated knowledges. International development research documenting this method often amounts to methodological ‘how-to’ discussions around procedural ethical considerations (e.g. of consent, confidentiality, anonymity and dissemination). Despite these important insights, scholarship on the ethics of photoelicitation is almost exclusively concerned with participant-produced photographs. Less considered are reflexive elaborations around unanticipated ‘ethically important moments’ (Guillemin & Gillam, Citation2004), that occur unexpectedly in the here and now of researcher-supplied photoelicitation research. Within this context, this article offered a critical retrospective reflection of using photoelicitation methodology in a qualitative focus group-based, audience-reception study with UK African Diasporic communities.

Specifically, it documented my unpreparedness for participant confessional stories and emotional responses about identity and racism, triggered by fundraising photos depicting Black African impoverishment. For these diasporic audiences, their ethnoracialised and cultural identities played a central role in the photoelicitation environment in such a way that they self-reference in their reception and interpretation of images. Not only does this demonstrate a photograph’s potential to articulate and sensitise identities and emotional memories other than those of their immediate appearances, but my candid experiences of these ethical moments also highlight how INGO fundraising images have and continue to reinforce and perpetuate racist and culturally insensitive stereotypes, and the negative consequences this has on audiences who share racialised identities with those featured in such images.

Taking important lessons learned from these reflections, the article recommended critical reflexivity as an ethical safeguard whereby international development researchers incisively interrogate their positionalities and scrutinise their photograph selection when using photoelicitation. Critical reflection is also encouraged when making important assessments around the ethical appropriateness of using photos that audience groups may identity with and relate to in unique and defining ways.

Far from being an endpoint or a magic wand, critical reflexivity as an ethical safeguard does not suggest that all ethically important moments are observed clairvoyantly and halted before they emerge. Rather it encourages a certain ethical sensibility and attentiveness that shields against the potentially harmful repercussions of unpreparedness. As such, we must not rely on a blind faithfulness in IEC approval especially given that procedural ethics is often short-sighted regarding some ethical dilemmas and ambiguities that arise unexpectedly in fieldwork.

The article’s relevance and contributions are three-fold. First, it provides important and timely methodological elaborations to the transdisciplinary photoelicitation literature, particularly the researcher-supplied approach—in this case, with UK African Diasporic communities. Black African diaspora are not just an underrepresented group that need to be included because of their previous exclusion within research. Rather, they are a significant audience group with a distinct relationship to the imagery as the evidence presented in this article shows. Second, by focusing on ethically important moments, the article offers a useful critique for development researchers of ethical issues that might arise unexpectedly in their photoelicitation studies. Third, and relatedly, it amplifies broader calls to centre critical reflexivity in social science investigations.

While the study is UK-based and informed by a Black African racialised analysis, its reflexive considerations nonetheless have broader application beyond these contexts. It is hoped the methodological reflections and recommendations will be a useful resource—among other aforecited publications—for both academic and development practitioners in their preparations for and practice of photoelicitation. With that said, this article encourages other researchers to produce written critical reflections on their use of researcher-supplied photoelicitation in different contexts and with other audience groups.

Finally, as with my previous publications on INGO photographs, it is hoped that this article contributes to shortening the acknowledged academic-practitioner communication gap within the international development space, and especially the fundraising and communications sub-field, in order to broaden and consolidate the research sharing base.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Those featured in the images and their communities

2 The UK membership body for INGOs

3 A borough in South London

4 e.g., an overly formal and educated accent problematically racialised as ‘white’ and classed as ‘middle-upper’

5 A popular UK-based charity founded in 1985

References

- Ademolu, E. (2018). Rethinking audiences: Visual representations of Africa and the Nigerian diaspora (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://research.manchester.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/rethinking-audiences-visual-representations-of-africa-and-the-nig

- Ademolu, E., & Warrington, S. (2019). Who gets to talk about NGO images of global poverty? Photography and Culture, 12(3), 365–376. doi:10.1080/17514517.2019.1637184

- Ademolu, E. (2021). Racialised representations of Black African poverty in INGO communications and implications for UK African diaspora: Reflections, lessons and recommendations. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, e1718. doi:10.1002/nvsm.1718

- Ademolu, E. (2023a). Birds of a feather (don’t always) flock together: Critical reflexivity of ‘Outsiderness’ as an ‘Insider’ doing qualitative research with one’s ‘Own People. Qualitative Research, 0(0), 146879412211495. doi:10.1177/14687941221149596

- Ademolu, E. (2023b). Visualising Africa at diaspora expense? How and why humanitarian organisations ignore diaspora audiences in their ‘ethical’ communications. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 28(2), e1783. doi:10.1002/nvsm.1783

- Armstrong, R., Gelsthorpe, L., & Crewe, B. (2014). From paper ethics to real-world research: supervising ethical reflexivity when taking risks in research with ‘the risky. In Lumsden K., & Winter A. (Eds.), Reflexivity in criminological research: Experiences with the powerful and powerless (pp. 207–219). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Beale, B., Cole, R., Hillege, S., McMaster, R., & Nagy, S. (2004). Impact of in-depth interviews on the interviewer: Roller coaster ride. Nursing & Health Sciences, 6(2), 141–147. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2004.00185.x

- Black, G. F., Davies, A., Iskander, D., & Chambers, M. (2018). Reflections on the ethics of participatory visual methods to engage communities in global health research. Global Bioethics = Problemi di Bioetica, 29(1), 22–38. doi:10.1080/11287462.2017.1415722

- Boxall, K., & Ralph, S. (2009). Research ethics and the use of visual images in research with people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(1), 45–54. doi:10.1080/13668250802688306

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An invitation to reflective sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Burkitt, I. (2012). Emotional reflexivity: Feeling, emotion and imagination in reflexive dialogues. Sociology, 46(3), 458–472. doi:10.1177/0038038511422587

- Church, S., & Quilter, J. (2021). Consideration of methodological issues when using photo-elicitation in qualitative research. Nursing Res, 29(2), 25–32.

- Clark-Ibáñez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507–1527. doi:10.1177/0002764204266236

- Collier, J., & Collier, M. (1986). Visual anthropology: photography as a research method. Albuquerque: New Mexico Press.

- Clifford, J. (1986). Partial truths. In: Clifford J., & Marcus G. (Eds.), Writing culture (pp. 1–26). Santa Fe: School of American Research.

- Creighton, G., Oliffe, J., Ferlatte, O., Bottorff, J., Broom, A., & Emily, J. (2018). Photovoice ethics: Critical reflections from men’s mental health research. Qualitative Health Research, 28(3), 446–455. doi:10.1177/1049732317729137

- Crombie, J., & Girling, D. (2022). Who owns the story? Live financial testing of charity vs participant led storytelling in fundraising. Retrieved from https://amrefuk.org/media/25fjc0ua/amref-health-africa_who-owns-the-story_report_final.pdf

- Diamond, K. E., & Hestenes, L. L. (1996). Preschool children’s conceptions of disabilities: The salience of disability in children’s ideas about others. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16(4), 458–475. doi:10.1177/027112149601600406

- Dillon, E. (2021). Shifting the lens on ethical communications in global development: A focus on NGDOs in Ireland.

- Dogra, N. (2012). Representations of global poverty: Aid, development and international, NGOs. London: I.B., Tauris.

- Emerson, M. R., Fretz, I. R., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Esin, C., & Lounasmaa, A. (2020). Narrative and ethical (in)action: creating spaces of resistance with refugee-storytellers in the Calais ‘Jungle’ camp. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(4), 391–403. doi:10.1080/13645579.2020.1723202

- Evans-Agnew, R. A., & Rosemberg, M. A. (2016). Questioning photovoice research: Whose voice? Qualitative Health Research, 26(8), 1019–1030. doi:10.1177/1049732315624223

- Fairey, T. (2018). These photos were my life: Understanding the impact of participatory photography projects. Community Development Journal, 53 (4), 618–636. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsx010

- Flores, G., & Malik, A. (2015). What development means to diaspora communities. BOND, 1–3.

- Freeman, A. (2004). Cognition and Psychotherapy. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Frith, H., & Harcourt, D. (2007). Using photographs to capture women’s experiences of chemotherapy: Reflecting on the method. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1340–1350. doi:10.1177/1049732307308949

- Guillemin, M., & Drew, S. (2010). Questions of process in participant generated visual methodologies. Visual Studies, 25(2), 175–188. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2010.502676

- Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and “ethically important moments” in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(2), 261–280. doi:10.1177/1077800403262360

- Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2006). Telling moments: Everyday ethics in health care. Australia: IP Communications.

- Hall, J., & Mitchell, M. (2008). Exploring student midwives creative expression of the meaning of birth. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3(1), 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2007.09.004

- Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345

- Hill, L. (2014). Some of it I haven’t told anybody else’: Using photo elicitation to explore experiences of secondary school education from the perspective of young people with a diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Educational and Child Psychology, 31(1), 79–89. doi:10.53841/bpsecp.2014.31.1.79

- Holland, J. (2007). Emotions and research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 10(3), 195–209. doi:10.1080/13645570701541894

- Joanou, J. (2009). The bad and the ugly: Ethical concerns in participatory photographic methods with children living and working on the streets of Lima, Peru. Visual Studies, 24(3), 214–223. doi:10.1080/14725860903309120

- Kaplan, E. (2005). British attitudes towards the UK’s international priorities. The Chatham house/YouGov survey 2001. London: Chatham House.

- Katz, J. (2006). Ethical escape routes for underground ethnographers. American Ethnologist, 33(4), 499–506. doi:10.1525/ae.2006.33.4.499

- Khanlou, N., & Peter, E. (2005). Participatory action research: Considerations for ethical review. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 60(10), 2333–2340. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.004

- Liebenberg, L. (2009). The visual image as discussion point: Increasing validity in boundary crossing research. Qualitative Research, 9(4), 441–467. doi:10.1177/1468794109337877

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. USA: Sage Publications.

- Mok, T. M., Flora, C., & Tarr, J. (2015). Too much information: Visual research ethics in the age of wearable cameras. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science, 49(2), 309–322. doi:10.1007/s12124-014-9289-8

- Moran, C., & Gatwiri, K. (2022). #BlackLivesMatter: Exploring the digital practises of African Australian youth on social media. Media, Culture & Society, 44(7), 1330–1353. doi:10.1177/01634437221089246

- Murphy, E., & Dingwall, R. (2007). Informed consent, anticipatory regulation and ethnographic practice. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 65(11), 2223–2234. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.008

- Opoku-Owusu, S. (2003). What can the African diaspora do to challenge distorted media perceptions about Africa? London: African Foundation for Development.

- Pain, H. (2012). A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(4), 303–319. doi:10.1177/160940691201100401

- Pittaway, E., Bartolomei, L., & Hugman, R. (2010). Stop stealing our stories’: The ethics of research with vulnerable groups. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 2(2), 229–251. doi:10.1093/jhuman/huq004

- Prins, E. (2010). Participatory photography: A tool for empowerment or surveillance? Action Research, 8(4), 426–443. doi:10.1177/1476750310374502

- Reed, K., & Ellis, J. (2020). Uncovering hidden emotional work: Professional practice in paediatric post-mortem. Sociology, 54(2), 312–328. doi:10.1177/0038038519868638

- Samuels, J. (2004). Breaking the ethnographer’s frames reflections on the use of photo elicitation in understanding Sri Lankan monastic culture. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1528–1550. doi:10.1177/0002764204266238

- Sim, J., & Waterfield, J. (2019). Focus group methodology: some ethical challenges. Quality & Quantity, 53(6), 3003–3022. doi:10.1007/s11135-019-00914-5

- Stanley, L., & Wise, S. (1990). Feminist praxis: Research, theory and epistemology in feminist sociology. London: Routledge.

- Tani, S. (2014). The right to be seen, the right to be shown: ethical issues regarding the geographies of hanging out. YOUNG, 22(4), 361–379. doi:10.1177/1103308814548102

- Thupayagale‐Tshweneagae, G., & Mokomane, Z. (2014). Evaluation of a peer‐based mental health support program for adolescents orphaned by AIDS in South Africa. Japan Journal of Nursing Science : JJNS, 11(1), 44–53. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2012.00231.x

- van der Gaag, N., & Nash, C. (1987). Images of Africa: The UK report. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Walstra, V. (2020). Picturing the Group: Combining Photo-elicitation and Focus Group Methods. Anthrovision, 8(8.1), 1–23. doi:10.4000/anthrovision.6790

- Wambu, O. (2006). AFFORD's experience with the ‘Aiding & Abetting’ project. The Development Education Journal, 12(3), 21–23.

- Wang, C. C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health, 8(2), 185–192. doi:10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185

- Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 24(3), 369–387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309

- Wang, C. C., & Redwood-Jones, Y. A. (2001). Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from flint photovoice. Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 28(5), 560–572. doi:10.1177/109019810102800504

- Warin, J. (2011). Ethical mindfulness and reflexivity: Managing a research relationship with children and young people in a 14-year Qualitative Longitudinal Research (QLR) Study. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(9), 805–814. doi:10.1177/1077800411423196

- Warrington, S., & Crombie, J. (2017). The people in the pictures: Vital perspectives on save the children’s image making. Save the Children UK. Retrieved from https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/people-pictures-vital-perspectives-save-childrens-image-making/

- Warrington, S. (2020). The people in the pictures research: Taking care with photo elicitation. In Dodd, S. (Ed.), Ethics and integrity in visual research methods: Advances in research ethics and integrity (pp. 43–63). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Weinger, E. (1998). Children living in poverty: Their perception of career opportunities. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 79(3), 320–330. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.993

- Young, O. (2012). African images and their impact on public perception: What are the human rights implications? Belfast: Institute for Conflict Research.