?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We examine the effects of violent crime on corporate investment and financing decisions of Brazilian firms. Exploring city variation in homicides, we find that an increase in the growth rate of homicides is associated with significantly lower corporate investments, with lower labour investments, and with a higher likelihood of layoffs. Spikes in violent crime are also associated with more conservative financing policies, reflected in higher cash holdings, in lower R&D (research and development) expenditures, and in lower dividend payments. Homicides further affect investment efficiency and financing choices, decoupling investment from debt finance and profitability. Moreover, the negative association between homicides and investment is significantly stronger in smaller firms, which highlights the uneven costs of violent crime in reducing firm growth.

1. Introduction

Since the seminal work of Becker (Citation1968), interest in the economic effects of crime gained prominence in the academic and policy debates. Empirical evidence often supports the view that crime is associated with deterioration in economic activity (Mirenda, Mocetti, & Rizzica, Citation2022; Pinotti, Citation2015; Soares, Citation2004). Since investment and consumption are negatively affected by risk and uncertainty, criminality can constrain business activities in several ways, such as goods damage, crime prevention and surveillance costs, and importantly, the threat of victims’ loss of life (Anderson, Citation1999).

However, the role of crime in affecting investment at the microeconomic level remains little understood in the financial development literature. While a few studies suggest that crime reduces investment and growth, empirical evidence remains scant, and mostly circumstantial. Some studies have focused either on an aggregated level (Detotto & Otranto, Citation2010) or on very specific and localised types of investment, such as building activity within neighbourhoods (Acolin, Walter, Tillyer, Lacoe, & Bostic, Citation2022; Lacoe, Bostic, & Acolin, Citation2018). However, while firms are important promoters of investment, the potential effect of crime on corporate investment has received limited attention. A few exceptions include Mirenda et al.’s (Citation2022) study on the impact of organised crime infiltration on firm growth in Italy, and Pshisva and Suarez’s (Citation2010) study on kidnappings and investment in Colombia.

We examine the effect of crime on investment, focusing on the Brazilian experience in dealing with violent crime. Brazil is a highly pertinent case study, having one of the highest and fastest-growing violent crime rates among the largest economies (Cerqueira, Citation2014; Chong & Yañez-Pagans, Citation2017; Di Tella, Edwards, & Schargrodsky, Citation2010; Murray, de Castro Cerqueira, & Kahn, Citation2013). For instance, Murray et al. (Citation2013) suggest that between 1980 and 2010 about one million homicides were recorded in Brazil, a shocking war-like figure that highlights the relevance of homicides as a leading crime indicator potentially affecting economic choices, and weighing significantly on managers’ risk-taking behaviour and corporate investment decisions. However, how exactly increased exposure to violence affects risk-taking attitudes remains unsettled. For instance, Nasir, Rockmore, and Tan (Citation2020) provide evidence that the escalation in violence resulting from the war on drugs in Mexico increased risk-aversion, whereas Callen, Isaqzadeh, Long, and Sprenger (Citation2014) show that exposure to violence in Afghanistan is positively associated with preferences for certainty in economic decisions. In contrast, Voors et al. (Citation2012) show that, in Burundi, exposure to violence is associated with increased risk-seeking behaviour, instead. We investigate the impact of violent crime on corporate risk-taking attitudes of Brazilian firms, examining whether increases in city-level homicides affect how much firms invest, the sensitivity of investment to financing sources and growth conditions, such as cash flows, credit, and growth opportunities, and the riskiness of key corporate policies, such as cash holdings, dividend payout, and R&D expenditures.

Our empirical analysis examines Brazilian firms, covering the period between 2003 and 2018. Estimates from corporate investment regressions show that a faster growth rate in city-level homicides is associated with significantly lower corporate investments. Our findings remain robust to the inclusion of control variables at the firm (lagged investment, size, growth, cash flows, and leverage) and state (employment, economic growth, and population) levels, and to models accounting for key sources of unobserved heterogeneity with the inclusion of firm and time fixed effects.

To test for economic transmission channels, we estimate interactions between homicides growth rates and several firm variables affecting investment: size, cash flows, leverage, and growth opportunities. We find that violent crime renders investment significantly more sensitive to firm size, but less sensitive to cash flows and to debt finance. Hence, violent crime hurts investments more in small firms, and disconnects investments from profitability and credit availability, which signals some degree of inefficiency. We also show that growth in homicides is significantly associated with higher cash holdings (a variable that reflects financial conservatism), but with less investment in innovations (R&D) and dividend payments. These findings altogether suggest that spikes in violent crime render firms more conservative in their investment, financing, and pay-out policies.

We conduct several tests to strengthen our empirical analyses and the identification. We run sensitivity analyses on our baseline GMM model (regarding choice, type, and number of instruments, specification, and so forth), ensuring its robustness. Examining plant-level data, we show that increases in homicides are associated with smaller plant sizes, with a lower growth rate of labour investments, and with a higher likelihood of layoffs even after controlling for economic growth. We also explore an exogenous shock to crime in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Following the investments made for the 2016 Olympic games in the city of Rio, the public finances of Rio’s state collapsed, triggering a spike in violent crime mostly linked to deterioration in policing and law enforcement. Meanwhile, the neighbouring state of São Paulo managed to reduce violent crime significantly, resulting from effective public policies, and unification of power within a single crime faction. Our DiD estimates suggest that, following this relevant shock to public safety resulting in higher crime, firms from the state of Rio significantly cut investment compared to firms from São Paulo.

We also run a series of robustness tests (presented in the Supplementary Materials). We show that sharp increases in homicides are associated with a contemporaneous reduction of investment which shows weak signs of recovery even after two years. Conversely, sharp decreases in homicides are not associated with higher investments, which suggests that investment responds asymmetrically to surges in crime. We analyse the role of income transfers as a policy shock negatively affecting crime (for example, Akee, Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, Citation2010). Using state-level changes in income transfers from the Bolsa Familia program, we demonstrate that while increases in transfers (which plausibly reduce crime) are not associated with higher investment, decreases in transfers (which plausibly increase crime) are associated with lower investments.

Our study accords several contributions. More generally, higher crime rates have been linked to several economic outcomes, such as slower growth (Detotto & Otranto, Citation2010; Pinotti, Citation2015), higher levels of income inequality (Soares, Citation2004), lower business confidence (Almeida & Montes, Citation2020), to a weaker performance of the tourism sector (Biagi & Detotto, Citation2014), and to weaker entrepreneurship (Rosenthal & Ross, Citation2010). At the micro-level, crime has been associated with reductions in production and higher likelihood of market exit (Camacho & Rodriguez, Citation2013; Rozo, Citation2018), with reduced firm presence in crime-ridden localities (Blumenstock et al., Citation2020), with sub-optimal agricultural production in conflict areas (Arias, Ibáñez, & Zambrano, Citation2019; Singh, Citation2013), with poorer financial performance (Gaviria, Citation2002), and with slower growth in micro-enterprises (BenYishay & Pearlman, Citation2014). Specifically related to investments, the literature suggests that higher crime is associated with lower private (Acolin et al., Citation2022; Lacoe et al., Citation2018) and foreign (Ashby & Ramos, Citation2013; Blanco, Ruiz, & Wooster, Citation2019; Daniele & Marani, Citation2011) investments. We provide fresh empirical evidence on the negative impact of crime at the micro level by examining how corporate investment responds to surges in crime, thus showcasing the negative spillovers of crime on firm growth.

We extend, and corroborate, the Colombian evidence presented by Pshisva and Suarez (Citation2010), whereby crime lowers investment mostly through a credit channel, by showing that in addition to access to debt, crime also renders investment by Brazilian firms less sensitivity to internal cash flows, but more sensitive to firm size. Such findings suggest that violent crime decouples investment from debt and profitability, while depressing investment more strongly in smaller firms. Such crime-induced inefficiency seems in line with Mirenda et al. (Citation2022), as they show that infiltration by organised crime decouples firms’ revenues from growth, deteriorating their finances, and leading to market exit. Given the interlocked relationships of investment and financing policies (Agrawal & Mandelker, Citation1987; Almeida & Campello, Citation2007; Fama, Citation1978), we present new evidence on the effect of violent crime on how much firms invest and how their investments respond to different sources of finance and to surrounding economic conditions. Our findings also inform the debate on the effect of violence on economic risk-taking behaviour (Callen et al., Citation2014; Nasir et al., Citation2020; Voors et al., Citation2012), as we show that surges in violence are associated with more conservative firm policies.

Our study also speaks to a broader financial economics literature examining corporate investment decisions. The sensitivity of investment to heterogeneous firm and industry characteristics (such as growth opportunities, cash flows, leverage, ownership structure, corporate governance, and product market competition) has been extensively examined (Ahn, Denis, & Denis, Citation2006; Almeida & Campello, Citation2007; Frésard & Valta, Citation2015; Goergen & Renneboog, Citation2001; Hirth & Viswanatha, Citation2011; Jiang, Kim, Nofsinger, & Zhu, Citation2015; Kang, Kumar, & Lee, Citation2006; Sanford & Yang, Citation2022). In contrast, how the risks posed by the environment external to firms affects their investment decisions and risk-taking attitudes remains far less understood, and the literature in this area is still maturing. For instance, a growing body of recent studies suggests that factors such as political and economic policy uncertainty (Bonaime, Gulen, & Ion, Citation2018; Julio & Yook, Citation2012; Nguyen & Phan, Citation2017), macroeconomic risk (Chen & Strebulaev, Citation2019), and corruption (Colonnelli, Lagaras, Ponticelli, Prem, & Tsoutsoura, Citation2022; Du & Heo, Citation2022; Giannetti, Liao, You, & Yu, Citation2021; Sena, Duygun, Lubrano, Marra, & Shaban, Citation2018; Xu & Yano, Citation2017) all exert important constraints on corporate investments. However, the effect of external risks stemming from social interactions, like criminality and violence, which are at play often within the immediate communities where firms are inserted and operate (for example their cities), has so far remained at the fringe of the debate. To the best of our knowledge, our study is among the pioneers in this literature to identify the effects of city-level violent crime on corporate investment and financing decisions.

The balance of the paper is as follows. Section Two brings the data and the research design. Section Three reports the main results. Section Four concludes.

2. Research design

2.1. Data and variables

Our dataset combines data from two sources. Firm-level data is obtained from Osiris (Bureau Van Dijke). City-level homicides and state economic data is sourced from IPEA – Institute of Applied Economic Research (see in the Appendix for variable definitions and summary statistics). Based on their registered trading address, we match the firms to their cities. While homicides data goes back to 1980, we are able to collect firm-level data starting from 2003 due to limited data availability (mostly given by a fairly small number of firms prior to that). Hence, our dataset covers the period between 2003 to 2018, featuring investment data for 539 non-financial firms, including publicly listed and privately held firms located in 106 cities and in 20 states.Footnote1

We measure investment (investmentit) as Capex (capital expenditures) scaled by Total Assets (Babenko, Lemmon, & Tserlukevich, Citation2011; Fahlenbrach, Citation2009). To measure violent crime, we employ the growth rate of city homicides per 100,000 persons (). We focus on homicides growth rather than levels following the evidence presented by Lacoe et al. (Citation2018) whereby investment is more sensitive to crime in fast-changing crime environments. Intuitively, managers are aware of historical crime levels in their locations, such that high levels do not necessarily come as a surprise. However, growth in crime rates is harder to predict, being thus more relevant to the uncertainties surrounding investment. Our choice for homicides as our measurement of crime is in line with the extant literature. For instance, both Nasir et al. (Citation2020) and Pshisva and Suarez (Citation2010) provide clear evidence that escalation in the violence connected with drug wars (such as homicides and kidnappings) affects risk-taking attitudes, such as individual and corporate investment decisions. Our focus on violence and in homicides as our proxy for crime is also consistent with growing evidence from the literature that shows that crimes that lead to loss of life (for instance, terrorism) are those that can significantly affect managerial sentiment, perceived uncertainty, risk preferences, and therefore corporate investments (for example see Dai, Rau, Stouraitis, & Tan, Citation2020; Chen, Wu, & Zhang, Citation2021).Footnote2

In our baseline model, we control for several firm variables known to affect investment. We control for the natural log of Total assets as a proxy for firm Size (Firth, Lin, & Wong, Citation2008), for Sales growthFootnote3 as a proxy for Growth opportunities (Fisman & Love, Citation2007), for EBITDA/Assets as a proxy for Cash flows (Lang, Ofek, & Stulz, Citation1996), and for Debt/AssetsFootnote4 as a proxy for leverage (Ahn et al., Citation2006). We also include state-level controls capturing local economic conditions, such as Employment growth (net employment creation scaled by resident population),Footnote5 Economic growth (rate of change in state GDP), and Population (natural log of resident population).

2.2. Econometric model

We estimate a dynamic corporate investment regression model. Investment is regressed against lagged Investment, city Homicides growth, plus firm controls collected in vector (Size, Growth, Cashflows, and Leverage), and state-level controls collected in vector

(Employment, Growth, and Population).Footnote6 We include firm fixed effects (αi) to control for firm (and city) unobserved heterogeneity. For instance, unobserved characteristics of managers can affect investment and correlate with risk perception.Footnote7 As we do not observe important variables affecting investment (for example cost of capital, local interest rates, and so forth), lagged investment plays an important mitigating role by encapsulating adjustment costs (Eberly, Rebelo, & Vincent, Citation2012). We include year fixed effects (τ) to absorb economic cycles and attenuate serial correlation concerns. The standard errors are clustered at the state level, in line with the crime and investment literature (for example Pshisva & Suarez, Citation2010). The investment regression model is shown in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) :

(1)

(1)

Due to the inclusion of lagged investment and of the firm fixed effects, OLS is not suitable, thus we employ system GMM – Generalized Method of Moments (Greene, Citation2003; Roodman, Citation2009). The system GMM procedure involves instrumenting the explanatory variables by either GMM-style instruments (lagged levels) for variables which are predetermined (correlated with past errors) or endogenous (correlated with both past and current errors), or by IV-style instruments. In our baseline model, we follow standard practice and instrument past investment as endogenous, with GMM-type instruments. We follow evidence from the investment literature suggesting that leverage, growth, and cashflows may not be strictly exogenous determinants of investment (for example Blundell, Bond, Devereux, & Schiantarelli, Citation1992; Lang et al., Citation1996), instrumenting these variables as predetermined with GMM-type instruments too. While both endogenous and predetermined variables rely on GMM-type instruments, predetermined variables use lags 1 and longer as instruments, whereas endogenous variables use lags 2 and longer. Firm Size, Homicides growth, and the state-level control variables are initially instrumented by IV-style instruments. However, we relax these assumptions and run more stringent models as sensitivity checks, in which we allow for feedback effects between investment and homicides by setting homicides as predetermined or endogenous (instrumented by GMM-style instruments). Furthermore, we test additional specifications with all the firm and state-level controls also instrumented by GMM-style instruments.

However, imposing more stringency may come with trade-offs and risks, since by increasing the set of variables instrumented by GMM-style instruments, the number of instruments proliferate quickly, possibly leading to over-instrumentation which can affect the reliability of the diagnostics tests. Thus, we further run sensitivity analyses to mitigate typical problems that can be encountered in GMM models, such as the issue of over-instrumentation. We utilize collapsed instruments, which significantly reduce the number of instruments. We also test with the forward orthogonal deviations transformation as to deal with the issue of gaps in the panel. We test additional models with the Difference GMM estimator replacing the System GMM, and test with static OLS models.

3. Results

3.1. The effect of homicides on corporate investments

reports the main findings. Model (1) shows our baseline model, in which we find that an increase in city homicides growth is significantly and negatively associated with firm investment. Models (2–6) show sensitivity analyses on the GMM specification. Model (2) is a more conservative estimate in which we instrument homicides and all firm and state covariates as predetermined, with GMM-style instruments. To mitigate the proliferation of instruments, in this model we utilize collapsed instruments which significantly reduces the number of instruments. Nevertheless, we continue to observe a significantly negative effect of homicides on investment. In terms of economic significance, this model returns a coefficient equal to −0.010 for homicides growth. We interpret this coefficient as suggesting that a 1 percentage point (p.p.) increase in homicides growth is associated with a 0.010 (1.0 p.p.) reduction in firm investment. For a sample average investment of 0.04 (4 p.p.), this suggests that firms cut investment by a quarter following a 1 p.p. increase in homicides (although the economic effects may vary depending on the specifications).

Model (3) shows a sensitivity check where we reduce the number of instruments by modelling past investment as the only endogenous explanatory variable instrumented by GMM-style instruments. Model (4) is robustness check where we use orthogonal deviations of the GMM-instrumented variables, which attenuates estimation issues related to gaps in the panel. Model (5) considers homicides as an endogenous variable in the GMM procedure. In Model (6) we employ the difference GMM estimator instead of the system estimator. The findings remain robust to all these sensitivity tests. Overall, we observe large and significant Wald chi2 statistics which suggest the explanatory variables can jointly explain investment. The statistically insignificant and small chi2 and z statistics presented in the table suggest accepting the null of both Hansen’s J and Arellano-Bond AR2 tests across all the GMM models, regardless of instrument type, number, or specifications.Footnote8

A pertinent question that emerges is whether the negative association between investment and homicides is attributable to firms cutting investment when homicides increase, or to firms increasing investments when homicides decrease. The findings from model (7) refer to a model where we focus on increases in homicides only (measured as a dummy =1 if homicides growth¿0, and =0 otherwise). We find a significantly negative association between increases in homicides and firm investment, which suggests that firms indeed cut investments following surges in violence. In model (8) we run a sensitivity check, re-estimating model (7) via static OLS (with firm fixed effects) to ensure our findings are robust to methods other than GMM. We find a significantly negative association between increases in homicides and investment again.Footnote9 Regarding the controls, we observe a significantly positive association between lagged and current investment, which in fact corroborates the coherence of the dynamic structure of the model. While the coefficients of the controls show some variation across specifications, we find some evidence suggesting a positive association between investment and firm size, leverage, cash flows, and growth which are most in line with the empirical investment literature (we revisit these findings in Section 3.2, when estimating interactive effects).Footnote10 The state controls suggest a positive association of investment and GDP growth, and a negative association of investment with employment growth and population.

3.1.1. Examining key corporate policies beyond investment: cash holdings, R&D, and dividends

We now examine whether homicides have spill-over effects into key corporate policies: cash holdings, innovations (R&D), and dividends. shows the results.

In model (1), the dependent variable is Cash Holdings (Cash & Equivalents/Assets); in model (2) R&D investments (a dummy = 1 if firms report R&D expenditures, and =0 otherwise); and Dividends (Dividends/Sales) in model (3). Overall, the findings indicate that a faster growth of Homicides is significantly associated with higher cash holdings, but with lower investments in R&D and with lower dividend payments. Such findings altogether suggest that, in addition to being associated with depressed investment, spikes in homicides are also associated with financial conservatism as reflected in higher corporate savings (cash holdings), more funds being withheld by means of reduced dividend payments, and weaker risk-taking as encapsulated by lower R&D expenditures. We again accept the null of the Hansen’s J and Arellano-Bond specification tests in all the models.

3.2. Heterogeneous effects

Having established a negative link between homicides and investment, our next task is to identify economically credible transmission channels. We investigate two potential catalysts of heterogeneity: sources of finance, and the extent to which firms convert profitable opportunities in investment.

Several factors condition how firms finance investments, such as whether financing constraints are binding (Almeida & Campello, Citation2007), whether external finance is costly (Lyandres, Citation2007), as well as the degree of imperfections in credit markets (Ağca & Mozumdar, Citation2008). Smaller firms usually face higher borrowing constraints. When financial markets are more developed, typically firms rely less on internal funds to finance (Khurana, Martin, & Pereira, Citation2006). Firms may rely on external debt to finance investment and growth (Rahaman, Citation2011), although corporate debt might also serve a monitoring role through which it limits investment when managerial agency costs are elevated (Lang et al., Citation1996). We postulate that, by exacerbating credit market imperfections through the higher risk it encapsulates, violent crime may influence how firms choose to finance their investments. Furthermore, since crime undermines business confidence (Almeida & Montes, Citation2020), we test whether homicides affect the sensitivity of investment to profitability and growth.

Column (A) reported in shows the interactions between homicides and key drivers of investment: firm size, leverage, cash flows, and growth. Columns (B), (C), and (D) report the marginal effects of homicides growth evaluated at the 25th percentile (B), 50th percentile (C), and 75th percentile (D) of the distributions of each of the firm covariates interacted with homicides.

While investment displays a significantly positive sensitivity to firm size, a higher growth rate of homicides significantly reinforces this relationship. A plausible explanation is that, by exacerbating risk, violent crime undermines the investment capacity of smaller firms, which often face borrowing constraints. This finding highlights the uneven cost of crime in terms of investment, since smaller firms seem to be more strongly affected by surges in violence. The marginal effects confirm that homicides have a weaker impact in larger firms. The marginal effects of homicides are close to zero at the 25th percentile of Size, but negative below that. For instance, at the 10th percentile, the marginal effects are estimated at −0.005 (not tabulated for brevity), suggesting small firms cut investment when homicides increase. The marginal effects are positive as we approach the 75th percentile of Size (0.01), thus suggesting that larger firms respond to surges in crime by increasing investment. Next, we examine the interaction with leverage. We find that, while investment responds positively to leverage, a higher growth rate in homicides decouples investment from debt finance. This finding concurs with those reported by Pshisva and Suarez (Citation2010), whereby the authors suggest that reduced credit access might channel the negative impact of kidnappings to investment in Colombia. The marginal effects analysis suggests that the impact of homicides becomes stronger the higher leverage is. This finding is economically reasonable since higher crime can induce risk-aversion and affect the behavior of both borrowers and lenders. We also find a significantly negative interaction with cashflows, suggesting that crime decouples investment from profitability. This may signal inefficient investment, since although firms enjoy profitable investment opportunities, they become more hesitant in converting these options into real investment as violent crime escalates. However, we do not find any significant interactions with sales growth.Footnote11

3.3. Plant-level evidence

One remaining concern refers to the location of firms. Our data matches firms to cities of registration, thus our initial assumption was that firms operations are circumscribed to their cities. However, in reality most firms operate multiple plants which are spread around many different localities. In this section, we run sensitivity checks with plant-level data to mitigate such concerns.

As the Osiris dataset does not feature plant-level data, we utilise a different data source in this test. We use the plant (establishment) microdata from RAIS (Relação Anual de Informações Sociais), which is an administrative dataset maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor.Footnote12 The dataset includes data on the identification of the firm, the location of the plant, the industry, and the number of employees. However, unlike commercial databases such as Osiris, this dataset does not provide financial data, which limits the variables we can use in this test.

We use the data on the number of employees as a proxy for size and employment. We then aggregate the data at the firm-city level. We are able to gather data from 2006 to 2018, and run the test with a large sample of 5,472 firms located in 910 cities. We employ three alternative dependent variables in the tests: (i) we use the natural log of the total number of employees ((LN) Employees)) as a proxy for plants’ overall size; (ii) we calculate the growth rate in the number of employees (Δ (LN) Employees)) as a proxy for the growth in firms’ labour investments (net hirings); and (iii) we use the variable Layoffs which is calculated as a dummy =1 when the growth rate of the number of employees is negative (Δ (LN) Employees¡0)), and =0 otherwise.Footnote13

We regress all the three dependent variables against city homicides growth. While we are unable to include the same firm controls as in our baseline model because such data is unavailable, we control for the lagged dependent variable, and for firm and year fixed effects to minimize omitted variable bias to the best of our possibilities. We also include the city-specific growth rate of GDP to control for firms’ localised incentives to grow and hire (fire) workers. shows the results.

Model (1) shows the findings with (LN) Employees as dependent variable. We find a significantly negative coefficient for city homicides growth, suggesting that higher crime is associated with lower plant scale. We find a positive association between GDP growth and the scale of plants operated by firms, which suggests that firms grow more when the local economy expands. Model (2) shows the findings with the growth rate of the number employees as the dependent variable. We find a significantly negative association between homicides and the growth rate of labour investments (net hirings). Thus, beyond affecting capital investments, homicides are also associated with lower labour investments. Model (3) tests again whether homicides affect large and small firms differently. We find a negative base effect of homicides and a positive interaction with size (measured as the log of the number of plants), corroborating the view that the impact of homicides is weaker in larger firms. Finally, model (4) shows an alternative specification where we regress the Layoffs dummy against a discrete variable =1 when homicides increase, and =0 otherwise. We find that when homicides increase, firms are more likely to fire workers. Since we control for city economic growth (which is negatively associated with layoff likelihood, as expected), this effect is orthogonal to a purely growth-led channel and thus plausibly related to the higher risk surrounding surges in crime or possibly due to workers’ productivity losses that may be linked with spikes in crime. The statistically insignificant chi2 (Hansen) and z statistics (Arellano-Bond) suggest accepting the null in both tests. Overall, our findings remain robust to a neater and more granular treatment of firms’ locations, and suggest that crime, beyond depressing capital investments, has negative repercussions for employment too.

3.4. A shock to homicides in Rio vs São Paulo

This section explores an episode of surge in violent crime in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Following the heavy toll of the 2016 Olympic games to Rio’s public finances, the government administration was forced to declare a state of financial emergency, leading to dramatic budget shortfalls affecting healthcare, education, and public security. The deterioration in Rio’s social net, coupled with rife corruption by public officials, received significant international media coverage. For instance, an article published in The Financial Times highlights that Political paralysis wrought by the corruption scandals has created a vacuum that Brazil’s criminal gangs are rapidly trying to fill.Footnote14

With policing and law enforcement deteriorating, gangland feuds between crime factions gained ground. Following a period of stable crime (due to positive economic cycles in previous years), Homicides grew by about 16 per cent in 2016. Meanwhile in the neighbouring state of São Paulo, criminality fell significantly, resulting from effective policies, and from consolidation of power by a single faction (the case of São Paulo in combating crime is explored in De Mello & Schneider, Citation2010)

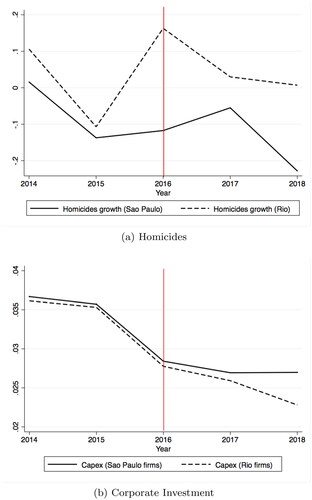

Panel (a) in compares Homicides growth in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo around 2016 (the year that marks the re-escalation of violence in Rio). We can spot that Homicides grew more or less in parallel in the two states before that, but following the financial collapse in Rio, homicides overshoot there, while remaining stable in São Paulo. Meanwhile, Panel (b) in shows that corporate investment by Rio and São Paulo firms follow similar trends prior to the event, decoupling afterwards, with Rio firms cutting investment vis-a-vis São Paulo firms.

We explore the collapse in Rio’s finances as a shock to Homicides in a difference-in-differences approach. Rio and São Paulo, in addition to being neighbouring states, are the two main economic powerhouses in Brazil. Since in Brazil police enforcement is controlled at the state-level (and not at the city-level), we include all firms headquartered in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in the test. We set firms headquartered in Rio as treated firms (=1) and firms headquartered in São Paulo as control firms (=0). We code a dummy =1 from 2016 onwards, and =0 before that. We estimate a standard DiD model, as specified in EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) . shows the results.

(2)

(2)

We begin with model (1) which includes the DiD coefficient, firm, and year fixed effects.Footnote15 We find a significantly negative coefficient DiD, indicating that firms in Rio cut investment vis-a-vis firms in São Paulo following the escalation in Homicides. The results of model (2), which includes firm controls, remain robust. In model (3), we apply Propensity Score Matching (PSM), matching Rio firms to their closest counterparts in São Paulo (based on Size, Growth, Cash flows, and Leverage), finding a statistically significant and negative DiD coefficient once again.

There are a few remaining concerns that require our attention. First, the reduction in investment might be due to deterioration in economic conditions following the shock to public finances, rather than via the escalation in violence. Second, the worsening of public finances may have affected government subsidies and incentives to the economy. Third, the prevalence of certain industries in Rio and São Paulo are notably different (for example the Oil & Gas industry is more present in Rio).

In model (4), we control for current and past economic growth and employment conditions. The DiD coefficient remains significant and negative, suggesting that the reduction in investment by Rio firms compared to São Paulo firms following the shock is orthogonal to purely economic conditions, being thus (plausibly) channeled via the abnormal increase in homicides in Rio. The size of the estimated DiD coefficient suggests that, following the shock, firms in Rio cut investment by 1.2 percentage points in excess of São Paulo firms, which seems a meaningful economic effect.

In model (5), we include a triple interaction between the Treat × Post dummy and a dummy =1 for state-owned firms, and =0 for privately-owned firms. The triple interaction plausibly controls for the loss of state financial support flowing via subsidies to the corporate sector. We find a significantly negative triple interaction, whereas the DiD remains significantly negative again. These findings suggest a stronger drop in investment when the state is a shareholder. Lastly, in column (6) we replace the firm fixed effects with industry and state fixed effects to net out any unobservable confounds at the industry and regional levels, observing robust findings again.

4. Conclusions

We examine the effect of violent crime on corporate investment decisions of Brazilian firms. We find that a higher growth rate in city homicides is associated with lower investment. Our results further suggest several transmission mechanisms through which violent crime affects the way firms finance investments. Higher crime rates make investment less responsive to debt finance, and decouple investment from profitability, thus suggesting that, due to escalation in crime, firms may lose confidence in their business environments despite enjoying access to finance and profitable opportunities. Our findings further suggest that violent crime triggers conservative policies, reflected in higher cash holdings, in lower dividend payments, and in lower innovative investments (R&D).

Our study sends important messages to policy makers in Brazil specifically, but also in other comparable emerging economies also facing crime-related challenges. We provide renewed empirical evidence on the negative implications of violent crime to economies and societies, reflected in lower and less efficient investment, and consequently weaker growth by firms. These findings highlight the potential growth benefits of public policies that (i) tackle crime (for example human capital development, education, and so forth), (ii) securitize external financing (for example access to credit and equity markets), and (iii) reduce uncertainty (for example boosting private insurance markets), and especially so in more violent locations. Many economists talk about the so-called poverty traps, which are pervasive economic failures that hamper growth in developing economies. Our study dissects how exactly violent crime disrupts investment, financing, and growth at the micro-economic (firm) level, which likely reverberates at the macro (regional) level by means of slower economic growth.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (93.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor and the two anonymous referees for the insightful and helpful comments. Any errors are our own. The firm-level data used in the study is from Osiris (Bureau van Dijk). The data is proprietary, and it can be purchased from BVD by subscription. The city-level crime and economic data is maintained by IPEA and can be download at www.ipea.gov.br. Code available upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We only observe the city location of the firms once at the headquarters level, and the sample includes both active and inactive firms, hence allowing for entry and exit.

2 Logically, other types of pettier crimes (like robberies) could impact investment decisions too, but our interpretation from the extant literature is that such lighter crimes are more relevant in contexts where investment is conducted by individuals or by smaller businesses, whereas for larger corporations (our focus) the literature suggests that violent crimes are more relevant.

3 We use Sales growth primarily since our data includes public and private firms.

4 We also test models using Bank Debt/Assets as an alternative proxy for credit (not reported for brevity), observing similar results.

5 Unemployment rates are periodically estimated for certain metropolitan areas in selected states only. Thus we use Employment creation as a broader (substitute) measure available to all states.

6 Such state variables capture economic conditions that could correlate with Homicides and affect Investment (for example in cities or states with higher unemployment firms may invest more as labour costs are cheaper, but higher unemployment may increase crime), and that are available for our full sample period. Moreover, city fixed effects (encapsulated by the firm effects) control for unobservable city characteristics that are time invariant, like secular attitude towards violence.

7 As we do not observe shifts in the locations of firms in our data, city fixed effects are encapsulated by the firm fixed effects.

8 We test for over-identifying restrictions with the Hansen’s J test (which is robust to heteroskedastic errors) and for second-order serial correlation in the error term with the Arellano-Bond test. We observe small chi2 test statistics for the Hansen’s J test, and small z test statistics for the Arellano-Bond test, which in both cases suggest accepting the null hypotheses of both tests in all the models. Furthermore, the chi2 statistic remains small and statistically insignificant even when strongly reducing the instrument count (for example model (3)), which suggests that instrument proliferation is unlikely to be affecting the reliability of the tests’ diagnostics.

9 To ensure we fully capture the uncertainties surrounding investment which are related to crime, we test additional models (not reported for brevity) including homicides in levels both contemporaneously and lagged by one and two periods. In all cases, we find coefficients equal to 0.000, which corroborate the view that managers care more about changes in crime than about levels.

10 One important issue to be considered is that crime can also impact the location of firms. To control for location preferences, we estimate an additional model (not reported for brevity) where we control for the number of peer firms (from the same industry) that also locate in the same city. We find a significantly negative correlation (of about -0.11) between the number of peer firms present in cities and the cities’ homicides (which suggests that firms locate less often in more violent cities). We then include the number of peer firms locating in the same state as a control variable in our investment models. While we observe an insignificant impact on firm investment, this control variable cleanses the correlation between location preferences and homicides from the investment equation.

11 Furthermore, we also tested interactions with variables capturing differences in the ownership structure of firms: we interact homicides with government ownership, and with foreign ownership. However, we did not find any significant interactions, which suggests that ownership structure does not affect the relation between investment and city homicides growth.

12 The RAIS dataset has been widely employed in studies relying on micro-level data (for instance, see Colonnelli et al, Citation2022).

13 Briefly commenting on key summary statistics: on average sample firms operate 2 plants per city, the average (standard deviation) number of firm-city employees is 552 (2514), whereas the average (standard deviation) growth rate in the number of employees is 0.035 (0.284).

14 The full story is entitled Rio violence exposes Brazil’s missed chance.

15 The individual coefficients of Treati and Postt are subsumed by the firm and year fixed effects.

References

- Acolin, A., Walter, R. J., Tillyer, M. S., Lacoe, J., & Bostic, R. (2022). Spatial spillover effects of crime on private investment at nearby micro-places. Urban Studies, 59(4), 834–850. doi:10.1177/00420980211029761

- Ağca, Ş., & Mozumdar, A. (2008). The impact of capital market imperfections on investment–cash flow sensitivity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(2), 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2007.02.013

- Agrawal, A., & Mandelker, G. N. (1987). Managerial incentives and corporate investment and financing decisions. The Journal of Finance, 42(4), 823–837. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1987.tb03914.x

- Ahn, S., Denis, D. J., & Denis, D. K. (2006). Leverage and investment in diversified firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(2), 317–337. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.03.002

- Akee, R. K., Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2010). Parents’ incomes and children’s outcomes: A quasi-experiment using transfer payments from casino profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), 86–115. doi:10.1257/app.2.1.86

- Almeida, A. F. G., & Montes, G. C. (2020). Effects of crime and violence on business confidence: Evidence from Rio de Janeiro. Journal of Economic Studies, 47(7), 1669–1688. doi:10.1108/JES-07-2019-0300

- Almeida, H., & Campello, M. (2007). Financial constraints, asset tangibility, and corporate investment. Review of Financial Studies, 20(5), 1429–1460. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhm019

- Anderson, D. A. (1999). The aggregate burden of crime. The Journal of Law and Economics, 42(2), 611–642. doi:10.1086/467436

- Arias, M. A., Ibáñez, A. M., & Zambrano, A. (2019). Agricultural production amid conflict: Separating the effects of conflict into shocks and uncertainty. World Development, 119, 165–184. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.11.011

- Ashby, N. J., & Ramos, M. A. (2013). Foreign direct investment and industry response to organized crime: The Mexican case. European Journal of Political Economy, 30, 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2013.01.006

- Babenko, I., Lemmon, M., & Tserlukevich, Y. (2011). Employee stock options and investment. The Journal of Finance, 66(3), 981–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01657.x

- Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217. doi:10.1086/259394

- BenYishay, A., & Pearlman, S. (2014). Crime and microenterprise growth: Evidence from Mexico. World Development, 56, 139–152. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.020

- Biagi, B., & Detotto, C. (2014). Crime as tourism externality. Regional Studies, 48(4), 693–709. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.649005

- Blanco, L. R., Ruiz, I., & Wooster, R. B. (2019). The effect of violent crime on sector-specific FDI in Latin America. Oxford Development Studies, 47(4), 420–434. doi:10.1080/13600818.2019.1611754

- Blumenstock, J., Ghani, T., Herskowitz, S., Kapstein, E., Scherer, T. L., & Toomet, O. (2020). How do firms respond to insecurity? Evidence from Afghan corporate phone records. Mimeo.

- Blundell, R., Bond, S., Devereux, M., & Schiantarelli, F. (1992). Investment and Tobin’s Q: Evidence from company panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 51(1-2), 233–257. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(92)90037-R

- Bonaime, A., Gulen, H., & Ion, M. (2018). Does policy uncertainty affect mergers and acquisitions? Journal of Financial Economics, 129(3), 531–558. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.05.007

- Callen, M., Isaqzadeh, M., Long, J. D., & Sprenger, C. (2014). Violence and risk preference: Experimental evidence from Afghanistan. American Economic Review, 104(1), 123–148. doi:10.1257/aer.104.1.123

- Camacho, A., & Rodriguez, C. (2013). Firm exit and armed conflict in Colombia. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(1), 89–116. doi:10.1177/0022002712464848

- Cerqueira, D. R. D. C. (2014). Causas e consequências do crime no Brasil [Causes and consequences of crime in Brazil]. Rio De Janeiro: Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES).

- Chen, W., Wu, H., & Zhang, L. (2021). Terrorist attacks, managerial sentiment, and corporate disclosures. The Accounting Review, 96(3), 165–190. doi:10.2308/TAR-2017-0655

- Chen, Z., & Strebulaev, I. A. (2019). Macroeconomic risk and idiosyncratic risk-taking. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(3), 1148–1187. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhy066

- Chong, A., & Yañez-Pagans, M. (2017). Impact of long run exposure to television on homicides: Some evidence from Brazil. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(1), 18–31. doi:10.1080/00220388.2016.1171843

- Colonnelli, E., Lagaras, S., Ponticelli, J., Prem, M., & Tsoutsoura, M. (2022). Revealing corruption: Firm and worker level evidence from Brazil. Journal of Financial Economics, 143(3), 1097–1119. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.12.013

- Dai, Y., Rau, P. R., Stouraitis, A., & Tan, W. (2020). An ill wind? Terrorist attacks and CEO compensation. Journal of Financial Economics, 135(2), 379–398. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2019.06.005

- Daniele, V., & Marani, U. (2011). Organized crime, the quality of local institutions and FDI in Italy: A panel data analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(1), 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.04.003

- De Mello, J. M., & Schneider, A. (2010). Assessing São Paulo’s large drop in homicides: The role of demography and policy interventions. In R. Di Tella, S. Edwards, & E. Schargrodsky (Eds.), The economics of crime: Lessons for and from Latin America (pp. 207–235). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Detotto, C., & Otranto, E. (2010). Does crime affect economic growth? Kyklos, 63(3), 330–345. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00477.x

- Di Tella, R., Edwards, S., & Schargrodsky, E. (Eds.). (2010). The economics of crime: Lessons for and from Latin America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Du, Q., & Heo, Y. (2022). Political corruption, Dodd–Frank whistleblowing, and corporate investment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 73, 102145. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102145

- Eberly, J., Rebelo, S., & Vincent, N. (2012). What explains the lagged-investment effect? Journal of Monetary Economics, 59(4), 370–380. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2012.05.002

- Fahlenbrach, R. (2009). Founder-CEOs, investment decisions, and stock market performance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 44(2), 439–466. doi:10.1017/S0022109009090139

- Fama, E. F. (1978). The effects of a firm’s investment and financing decisions on the welfare of its security holders. American Economic Review, 68(3), 272–284.

- Firth, M., Lin, C., & Wong, S. M. (2008). Leverage and investment under a state-owned bank lending environment: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(5), 642–653. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.08.002

- Fisman, R., & Love, I. (2007). Financial dependence and growth revisited. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2-3), 470–479. doi:10.1162/jeea.2007.5.2-3.470

- Frésard, L., & Valta, P. (2015). How does corporate investment respond to increased entry threat? Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 5(1), cfv015. doi:10.1093/rcfs/cfv015

- Gaviria, A. (2002). Assessing the effects of corruption and crime on firm performance: Evidence from Latin America. Emerging Markets Review, 3(3), 245–268. doi:10.1016/S1566-0141(02)00024-9

- Giannetti, M., Liao, G., You, J., & Yu, X. (2021). The externalities of corruption: Evidence from entrepreneurial firms in China. Review of Finance, 25(3), 629–667. doi:10.1093/rof/rfaa038

- Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. (2001). Investment policy, internal financing and ownership concentration in the UK. Journal of Corporate Finance, 7(3), 257–284. doi:10.1016/S0929-1199(01)00022-0

- Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Hirth, S., & Viswanatha, M. (2011). Financing constraints, cash-flow risk, and corporate investment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(5), 1496–1509. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.09.002

- Jiang, F., Kim, K. A., Nofsinger, J. R., & Zhu, B. (2015). Product market competition and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 35, 196–210. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.09.004

- Julio, B., & Yook, Y. (2012). Political uncertainty and corporate investment cycles. The Journal of Finance, 67(1), 45–83. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01707.x

- Kang, S. H., Kumar, P., & Lee, H. (2006). Agency and corporate investment: The role of executive compensation and corporate governance. The Journal of Business, 79(3), 1127–1147. doi:10.1086/500671

- Khurana, I. K., Martin, X., & Pereira, R. (2006). Financial development and the cash flow sensitivity of cash. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(4), 787–808. doi:10.1017/S0022109000002647

- Lacoe, J., Bostic, R. W., & Acolin, A. (2018). Crime and private investment in urban neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Economics, 108, 154–169. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2018.11.001

- Lang, L., Ofek, E., & Stulz, R. (1996). Leverage, investment, and firm growth. Journal of Financial Economics, 40(1), 3–29. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(95)00842-3

- Lyandres, E. (2007). Costly external financing, investment timing, and investment–cash flow sensitivity. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), 959–980. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.07.001

- Mirenda, L., Mocetti, S., & Rizzica, L. (2022). The economic effects of mafia: Firm level evidence. American Economic Review, 112(8), 2748–2773. doi:10.1257/aer.20201015

- Murray, J., de Castro Cerqueira, D. R., & Kahn, T. (2013). Crime and violence in Brazil: Systematic review of time trends, prevalence rates and risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(5), 471–483. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.003

- Nasir, M., Rockmore, M., & Tan, C. M. (2020). Do the lessons from micro-conflict literature transfer to high crime areas?: Examining Mexico’s war on drugs. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(1), 26–44. doi:10.1080/00220388.2017.1400016

- Nguyen, N. H., & Phan, H. V. (2017). Policy uncertainty and mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52(2), 613–644. doi:10.1017/S0022109017000175

- Pinotti, P. (2015). The economic costs of organised crime: Evidence from Southern Italy. The Economic Journal, 125(586), F203–F232. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12235

- Pshisva, R., & Suarez, G. A. (2010). Capital crimes: Kidnappings and corporate investment in Colombia. In R. Di Tella, S. Edwards, & E. Schargrodsky, (Eds.), The economics of crime: Lessons for and from Latin America (pp. 67–93). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Rahaman, M. M. (2011). Access to financing and firm growth. Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 709–723. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.09.005

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(1), 86–136. doi:10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Rosenthal, S. S., & Ross, A. (2010). Violent crime, entrepreneurship, and cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1), 135–149. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.001

- Rozo, S. V. (2018). Is murder bad for business? Evidence from Colombia. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(5), 769–782. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00735

- Sanford, A., & Yang, M. J. (2022). Corporate investment and growth opportunities: The role of R&D-capital complementarity. Journal of Corporate Finance, 72, 102130. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102130

- Sena, V., Duygun, M., Lubrano, G., Marra, M., & Shaban, M. (2018). Board independence, corruption and innovation. Some evidence on UK subsidiaries. Journal of Corporate Finance, 50, 22–43. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.028

- Singh, P. (2013). Impact of terrorism on investment decisions of farmers: Evidence from the Punjab insurgency. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(1), 143–168. doi:10.1177/0022002712464850

- Soares, R. R. (2004). Development, crime and punishment: Accounting for the international differences in crime rates. Journal of Development Economics, 73(1), 155–184. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2002.12.001

- Voors, M. J., Nillesen, E. E. M., Verwimp, P., Bulte, E. H., Lensink, R., & Soest, D. P. V. (2012). Violent conflict and behavior: A field experiment in Burundi. American Economic Review, 102(2), 941–964. doi:10.1257/aer.102.2.941

- Xu, G., & Yano, G. (2017). How does anti-corruption affect corporate innovation? Evidence from recent anti-corruption efforts in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45(3), 498–519. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2016.10.001

Appendix

shows summary statistics for the sample firms. The investment rate is about 0.04 (4%) for the average firm in the sample. There is significant heterogeneity in homicide rates in firms’ cities across Brazilian states, with southern states like Sao Paulo and Santa Catarina being the least violent states (less than 15 homicides per 100,000, on average), whereas in northern states violent crime is more pronounced, like in Ceara, Bahia and Pernambuco (over 40 homicides per 100,000). While some states record sizeable reductions in homicides (like -12% in Sao Paulo), other states experienced strong spikes in violent crime (like +6% in Ceara). Firm investment also shows relevant variability across states, and so does Employment, and GDP growth as well.

Table 1. The effects of homicides on corporate investments

Table 2. The effects of homicides on corporate policies

Table 3. Heterogeneous effects

Table 4. Plant-level evidence

Table 5. A shock to homicides in Rio vs São Paulo

Table A1. Variable definitions and summary statistics