Abstract

Millennial students, shaped by the rapid change in technology and connectivity, pose a challenge in devising new teaching and learning pedagogies. The team-based learning (TBL) approach has been used in several disciplines and is indicated as an effective way to use active learning techniques to help students improve their academic performance. The authors applied the TBL pedagogy to deliver the second term of a final-year core module of an economics undergraduate degree. The TBL intervention aimed to enrich students’ experience in learning, contextualizing, and applying economics to different issues and policies. The empirical analysis suggests that the authors achieved their aims. Their findings indicate that TBL improved students’ academic performance, reduced several achievement gaps, and enriched the students’ learning experience, making it more enjoyable.

Larry K. Michaelsen first developed team-based learning (TBL) in the late 1970s in response to increasing class sizes and his pedagogical views that a student-centered approach, focused on constructing knowledge, would offer better learning opportunities than traditional teacher-centered lecturing, motivated by transmitting knowledge, passively received by students. Universities in the United States have used TBL since the 1980s, but its uptake in UK higher education institutions has been slower but growing in popularity, as more educators recognize its pedagogical value. Several disciplines in higher education have adopted a partial or full version of TBL, notably in medical and engineering schools, while TBL applications in economics have been limited.

The TBL pedagogy rests on two key features (Michaelsen, Davidson, and Major Citation2014); firstly, the teacher is a facilitator instead of a dispenser of information, while students actively engage in problem-solving activities. Secondly, every aspect of TBL is specifically designed to develop and promote self-managed learning in a small learning group (Parmelee et al. Citation2012; Parmelee, Hudes, and Michaelsen Citation2013).

We viewed TBL as being a suitable tool to address equality and inclusion and a means to enrich our students’ learning experience and to improve their performance. In this study, we share our teaching experience with TBL and present our results. Our contribution is original in two main aspects: for the TBL design and for assessing the quality of the TBL overall learning experience, from a quantitative and a qualitative point of view. In designing the TBL intervention, we chose to implement its full original version, rather than parts of it, to deliver the second term of a two-term final core undergraduate module in economics. The material covered in Term 2 built and deepened the material introduced in Term 1. Given our previous knowledge of the students, following a stringent set of criteria, we could create balanced teams in terms of gender, ethnicity, and ability in order to address diversity, inclusion, and achievement gap issues.

The second element of originality is our focus on the overall quality of the TBL experience in learning economics. Because of its measurability, academic achievement is often used as an indicator of education quality, but students’ emotional health, perceptions, and views of their learning experience are also part of quality outcomes. To assess education quality via achievement, we used the data of two cohorts of students at two subsequent levels of progression. We applied a difference in differences (DID) approach and panel model to evaluate and quantify the effects of the TBL intervention on students’ performance. Our results confirm some previous findings that TBL had a positive impact on grades in economic courses. In addition to this more established result, we also found an encouraging reduction in the attainment gap for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) students.

To assess the quality of experience, we will look at three types of student engagement: behavioral engagement, such as class attendance, being in contact with teammates and giving and receiving teammate feedback on behavior; cognitive engagement, such as the effort to understand information and master complex skills; and emotional engagement, such as positive reactions to classmates, academic tasks and materials, and teachers. We will report on each of these dimensions.

Team-based learning (TBL): Theoretical background and literature review

We recognize three theories at the core of the TBL pedagogy: the constructivism theory of learning, the social interdependence theory (SIT), and the structure-process-outcome theory (SPOT). The constructivism theory of learning (Bruner Citation1960; Larkin and Richardson Citation2013) is a student-centered theory that focuses on explaining how individuals learn (Espey Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Haidet, Kubitz, and McCormack Citation2014), and not just on what they learn. This theory differs from a behaviorism theory of learning (Skinner Citation1974) that focuses on what can be learned and how the environment could induce a change in behavior and prompt the learning. The constructivist pedagogy replaces the passive transmission of knowledge with an active learning approach. The primary role of teachers is to create and maintain a collaborative problem-solving environment and facilitate group activities and discussions.

The other two theories behind TBL pedagogy are related to active learning in a small group. These theories are the SIT and the SPOT. The first one (Johnson and Johnson Citation1999) claims that interactions across members of a group are governed by the way goals are set, and these interactions, in turn, determine members’ outcomes. Positive interdependence is one type of social interaction that arises when the achievement of a member’s goal depends on the other members also reaching their goals. In this case, there is a mutual interest in promoting each other’s efforts to achieve common goals, interact, share resources, and manage conflicts. (Davidson, Major, and Michaelsen Citation2014). This kind of promotive interaction is indeed what TBL encourages and delivers (Johnson, Johnson, and Smith Citation2014).

The second theory, the SPOT, has provided a well-established framework for measuring and improving the quality of health care services (Donabedian Citation1980). It posits a linear sequential relation between structure, process, and outcomes of a situation (Johnson and Johnson Citation1989, Citation2005) and cascading effects from changes in structure into variations in process and outcome. In an educational setting, SPOT implies that by changing the structure (i.e., the context in which the learning is organized and the design of the learning activities), there will be effects on the process through which learning occurs (i.e., interactions), which in turn will affect students’ outcomes (i.e., learning achievements, well-being, self-efficacy, and confidence).

Because structure and process influence the quality of outcomes, the TBL approach focuses on the outcomes sought, and it follows a “design backward and deliver forward” criterion. The backward design requires instructors to identify the intended learning goals (i.e., outcomes) to create team application exercises conducive to the outcomes (i.e., process) and to organize the context and resources needed (i.e., structure) to enable the process. Thus, the instructor is trained to choose the outcomes before choosing the textbook or the activities. The process (i.e., group interactions) of learning in a small group is instrumental to the wanted outcomes, and without it, there would be no direct link between the outcomes and the structure.

TBL is not the only group learning approach. It differs in several aspects from problem-based learning (PBL) and cooperative learning (CL), alternative small group pedagogies. Firstly, according to some criteria, TBL groups are formed by the instructor and are permanent for the entire duration of the module. Students are expected to prepare for each session, and team members are highly accountable for their contributions to team performance and success. Secondly, due to the nature of learning activities, teamwork is collaborative rather than cooperative, so the tasks cannot be split and distributed among group members, but they need to be tackled by all members at the same time, as they need to converge their thinking in producing a single collective decision.

There is a substantial body of literature around TBL, covering descriptive, explanatory, and experimental research in nursing, medical, education, and business literature. Haidet, Kubitz, and McCormack (Citation2014) conducted a literature review of TBL and found that since 1996 the number of publications in this field has increased rapidly. Most applications implemented the full TBL method, while a quarter used only a partial version of this pedagogy. Recently, Swanson et al. (Citation2019) conducted a comprehensive search of TBL interventions, mostly in the fields of medicine and pharmacy, and carried out the synthesis and a meta-analysis of 30 studies to quantify and evaluate the effect of TBL on content knowledge outcomes. Their findings provide conclusive evidence that TBL enhances knowledge of the subject matter.

TBL has proved to be very successful in significantly increasing the motivation and learning performances of low-achieving students (Beaudin et al. Citation2017; Dolmans et al. Citation2015), improving students’ engagement and retention (Ibrahim and Saleem Citation2018; Jeno et al. Citation2017), influencing critical thinking, teamwork and gender diversity (Betta Citation2016), and improving final grades (Artz, Jacobs, and Boessen Citation2016). Sisk (Citation2011) conducted a systematic review study, and Liu and Beaujean (Citation2017) produced a meta-analysis of TBL. They all concluded that, with TBL, generally, students were satisfied, showed higher engagement in classes, and scored higher grades than in a standard individual exam. Lately, TBL has been used to examine the elements of “excellence” to investigate the learning environment and institutional context in influencing the perception of “excellence” in a teaching excellence framework (TEF) environment (Cohen and Robinson Citation2018).

Although TBL was first implemented in business schools, it has a more extended history in a wide range of medical courses. It is only recently that it has been considered as a suitable pedagogy in the field of economics. Imazeki (Citation2015) collected two years (4 semesters) of data for students enrolled in an economics module course delivered using the TBL approach. Using surveys and students’ grades, she concluded that TBL was suitable for modules with a strong focus on applications and analysis and that, overall, students engaged in in-depth discussion and group work and enjoyed the experience. Green (Citation2021) incorporated some core elements of TBL into an Essentials of Economics II module; he used the TBL application exercise element to promote class discussion around policy questions and decisions. In his view, these exercises led to lively debates, broadened students’ perspectives, and helped them to produce informed arguments on current key issues.

Espey (Citation2018b) surveyed several cohorts of economics students at different levels of progression during their degrees. She compared the students’ perceptions about the skills they gained in a typical versus a TBL course. Students recognized significant learning gains in a TBL environment for most skills, particularly for the critical thinking ones. These views were held consistently at any level of progression, achievement, and demographic characteristics.

Abio et al. (Citation2019) applied TBL in teaching economic theory modules. The empirical results show that TBL improves academic performance and increases class attendance, independently of the type of students. Nevertheless, the benefits are more notable in the groups of students retaking a course than the groups of students who enroll for the first time. Also, TBL fosters independent and continuous study, ameliorates the in-class learning environment, and stimulates team and collaborative work and interactions among many students. Moreover, all students become much more aware of the progress in their learning aptitudes and knowledge. Ruder, Maier, and Simkins (Citation2021) illustrate how the framework design and the highly structured components of the TBL approach work together to motivate pre-class preparation and in-class engagement. In their study, Simkins, Maier, and Ruder (Citation2021) focus on similar aspects and describe how the practice of repeated retrieval of key core concepts during the various phases of a TBL unit is a highly effective teaching strategy widely recognized by evidence-based learning science research.

Hettler (Citation2015), in his investigation, examined differences in student outcomes and experiences with TBL based on several demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status), focusing on students in principles-level economics and found small yet significant improvements in learning outcomes of low-income and minority students when compared to others.

Clerici-Arias (Citation2021) discussed the TBL experience in a principles of economics module at Stanford University and highlighted an additional qualitative side effect of the TBL approach: it altered the gender and ethnic composition of the classes, resulting in an increased representation of female and nonwhite students.

Based on the above evidence, we argue that the TBL method lends itself very well to our discipline because it helps students master the discipline’s higher-order learning and analytical skills. As expressed by Swanson et al. (Citation2019), the teaching of economics meets two conditions that make TBL most effective: firstly, modules often require students to understand a substantial amount of information and, secondly, most modules require students to apply this content to answer complex questions, to solve problems, and evaluate policies and scenarios.

TBL: Key features and the three -stage/phase design

Individual accountability and collaborative learning are critical features of the TBL 3-phase model, illustrated in . As explained earlier, these three phases are designed backward and delivered forward, so the last phase to be delivered is the first phase to be designed. However, here we refer to each phase according to the TBL delivery.

Table A2. Within-Groups (WG).

Table 1. Team-Based Learning (TBL), three-stage model.

In phase one, the pre-class preparation stage, students read the essential material selected and made available by the teacher two weeks before the TBL class. The second phase consists of two steps: the individual and then the group testing of the assigned reading material using a timed, closed-book, multiple choice question quiz. The quiz, called Individual Readiness Assurance Test (iRAT), assesses students individually. Students are then asked to join their teams, retake the same closed-book, timed quiz, renamed tRAT (Team Readiness Assurance Test), agree collaboratively, and commit to a team answer. The TBL standard practice for the tRAT is to provide real-time feedback using an Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique (IF_AT) card, a scratch-and-win type of testing card.Footnote1 After the tRAT test, the whole class discusses the correct answers, and a mini-lecture is delivered to address and clarify complicated issues and concepts. Both facilitators and each member of the team are aware of individual and team scores. Because both scores matter for the final grade, the design of phase two aims to prompt preparation and accountability before class and encourage collaboration to improve individual performance.

The third phase—the application phase—is designed to engage students in deepening their learning by applying the concepts that were tested in phase two. Teams are given common tasks requiring students to use new resources, search for data and empirical evidence, test hypotheses, and investigate new theories. This phase fosters group discussion and collaboration and leads students to explore new areas to reinforce and deepen their understanding of the topic.

TBL: Our design

We have been applying TBL for two consecutive years to two sets of cohorts of a 30-credit, final-year core module (Macroeconomics and Microeconomics in Context 2) for a Bachelor of Science course in economics. In designing the entire module, we chose to apply TBL only in the second term and to keep a traditional delivery (two-hour lecture and one-hour seminar/tutorial) and a standard assessment (simulation exercise) in the first term of the module.

In planning TBL activities for the second term, we could count on two valuable facts: firstly, we knew students well since we had already taught and assessed them in their second year for an intermediate level module (i.e., Macroeconomics and Microeconomics in Context 1); because of this previous knowledge, we were able to create well-balanced groups. Secondly, as it is showed in , the final-year core module had a topic-led structure, which made it possible to apply two different approaches in the two terms. We developed specific macro and micro themes in Term 1, using a traditional delivery, and we deepened the theoretical and empirical content of those themes in Term 2 by using TBL and real-world applications.

Table A3. Across-Groups (AG).

Table 2. Structure of the Level 6 Undergraduate, 30-credit Module.

During the summer, before the start of the academic year, we created teams of 5 or 6 members. We selected the teams’ members carefully, assuring that each team reflected the criteria of diversity and inclusivity in terms of abilities (using students’ second-year grades), gender, and ethnicity. Each group had a cumulative second-year grade to ensure balance in abilities across groups. On the first day of class, we informed the students about the Term 2 TBL delivery. We announced the groups and explained that membership was assigned and permanent to guarantee that the team-development process could come to fruition (Michaelsen, Davidson, and Major Citation2014). Because teams had not been self-selected by their members, we organized in Term 1 a team bonding fun activity (called Escape Room) to help team members to become closer, build trust and ease of communication, and prompt loyalty to one another and the team. We also believed that a positive shared experience could reveal team members’ strengths and weaknesses, and we asked each team to report back this type of feedback.

Facilitating the full delivery of TBL requires a specially designed and well-equipped classroom to allow group work/activity and to provide enough space for movements of both students and facilitators (Yuretich and Kanner Citation2015). We used a large room with separate and removable chairs and square tables suitable for up to eight students; individual laptops; a video player; whiteboards for each group; two projectors; and a visualizer. The room was booked for three consecutive hours, and all the cohorts attended at the same time in the same room. Both of us acted as facilitators during the entire TBL session.

In our approach, we have followed all TBL recommended activities rigorously, including the regular anonymous peer feedback, to monitor students’ learning experience. We also have enriched it by adding initiatives, such as the team bonding experience mentioned above and the regular short individual surveys, which we introduced after our first run of TBL, to make students feel heard and give them voices over their teaching and learning experience. These initiatives will be explained in detail in the last section when we present students’ views and feedback. We proceed in the next section to present our data, methodology, and quantitative results.

TBL: Quantitative analysis. Data, methodology, and results

Our data set consists of a collection of grades recorded at levels 5 and 6 for coursework submitted in Term 1 and Term 2 by the two cohorts, as approved by the end of the year (May) Progression and Award Boards (PABs).Footnote2 Our data are, therefore, a pooled set of repeated cross-sections. The cross-sections are the cohort of 2018 and the cohort of 2019, and each cross-section has a panel dimension, sampled four times: twice at level 5, for two pieces of coursework, called Essay_Debt in Term 1 and Essay_Patchwork in Term 2, and twice at level 6, for two pieces of coursework, called simulation Essay_Growth in Term 1 and TBL_Task in Term 2. Each subpanel (i.e., each cohort) is perfectly balanced because it refers to the same cross-sectional units (same cohort) observed at multiple points in time. The pieces of coursework assigned in Term 1 and Term 2 to the two cohorts were precisely the same at both level 5 and level 6. These four pieces of coursework enable us to compare within and across levels of performance and test if, for the two cohorts, the TBL intervention produced similar results. For instance, for each level, we can test for any significant difference between Term 1 and Term 2 performances and then compare these differences. Moreover, we could test for any difference in across-level performance for each term and compare them. All these comparisons would help understand the possible impact of the TBL intervention in Term 2 of the program’s final year.

shows the results of some tests on the pooled data of the cohort of 2018 and the cohort of 2019. The statistical tests performed on the pooled data show that, when we compare the standard essay type of coursework, we do not find any statistically significant differences in their means. So, for instance, if we take level 5, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the two pieces of coursework (Essay_Debt and Essay_Patchwork) have the same mean. We reach similar conclusions if we compare the essay type of coursework submitted in Term 1 of levels 5 and 6 (Essay_Debt and Essay_Growth). However, there are statistically significant differences in means when comparing essay standard coursework and TBL_task type of assessment, with the latter showing a consistent higher mean and a lower SD than the former.

Table 3a. Coursework Performance: Pooled Data (combining cohorts).

It is important to stress here that, despite the absence of statistically significant differences in means and standard deviations of traditional essay types of assessments across terms and levels of progression, we noticed some systematic differences across ethnic groups and gender that were not revealed by the aggregate. In particular, Black, Asian, and ethnic minority (BAME) students performed better than the White group in theoretical essays (Term 1), such as Essay_Debt, but they performed worse when facing more applied-analytical tasks, such as Essay_Patchwork (Term 2), with a noticeable drop in performance in Term 2, as indicated in . Given the very high percentage of BAME students in our cohorts, these patterns and gaps in achievement prompted us to intervene and use the TBL approach.

Methodology, part 1: Difference in differences (DID) analysis and results

The results of prompted us to investigate more carefully the effect of the TBL intervention. The TBL intervention, with its mix of theoretical and applied tasks and continuous provision of feedback, was aimed to improve students’ learning experience and academic performance via higher engagement and more active learning and ultimately reduce any systematic differentials in achievement.

To study the effect of the TBL intervention, we conducted a difference in differences (DID) analysis. The DID approach uses panel data to measure the differences between the treatment and control groups in the changes that occur over time in the outcome variable. In our case, it aimed at capturing the effect of TBL intervention by comparing TBL versus non-TBL delivery and assessments to investigate how the two performances differed. In this study, we could pool all students into one sample because the two cohorts had been assessed precisely in the same way (i.e., with the same essays and same TBL exercises). Each student in the pooled group was sampled four times (twice in the autumn term and twice in the spring term), thus being in both the control and treatment groups. Term 1 was treated as the control group because, across time, Term 1 retained standard teaching delivery and essay type assessment. On the other hand, Term 2 was considered the treatment group because, in this term, the delivery and type of assessment were changed from standard (pretreatment) into TBL types (treatment).

The DID methodology assumes that the unobserved differences between treatment and control groups are the same over time in the absence of treatment. Following this methodology, we tested for the presence of treatment effect by using the difference between the control and pretreatment groups at level 5 and comparing it with the difference between the control and the treatment groups at level 6. Our tests and results showed that the pre- and post-treatment trends were not the same and that the treatment had some effects. In , we present the panel and the treatment effect, showing the data for the DID analysis.

Table 4. Difference-in-Differences (DID)(*).

The possible issue that arises with DID analysis is that something other than the treatment could change in one group, but not in the other, concurrent with the treatment. This event would lead to a violation of the parallel trend assumption. However, in our case, the two groups are identical because, as explained, we have observations on the same individual at different levels of progression. Moreover, the assigned coursework did not change across cohorts, guaranteeing consistency in assessing the two cohorts. These two factors guarantee the DID estimate’s accuracy, given that the composition of the individuals belonging to the two groups remained unchanged over time and across assessments.Footnote3

As explained earlier, looking at the overall cohort’s average performance is not enough because the average can hide a differential in the performance of some cohort categories, such as ethnic and gender groups. We proceeded by assessing the “aggregate” effect of the treatment and, secondly, by analyzing the impact on the distribution of specific groups of students, such as BAME students, females, and quartiles.

The columns of show the results of the DID estimates of three models. In the second model, we included a covariate to control for a “learning effect” factor. This time trend captures the idea that, as students progress into higher levels, they gain “experience” via a learning-by-doing process, and they become better in their time management skills. We also added a Cohort_2018 dummy to control for possible specific cohort effects. We did not introduce any ethnicity or gender covariates at this stage because the control and treatment groups are identical. Our findings suggest that in all DID regressions, the TBL intervention produced the intended effect in increasing students’ performance by approximately 7 percentage points.

Table 3b. Balanced Panel: Composition.

Table 5. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Estimation Results.

We tested for possible ethnicity and gender effects by adding into the DID quartile regressions the covariates BAME (a dummy variable with value zero for White students and value 1 for nonwhite students) and Gender (a dummy variable with value zero for female students and value 1 for male students). reports the results for different quartiles. To avoid collinearity, we omitted the time trend “experience” in the quartile regressions.

Table 6. Difference-in-Differences (DID) Quartile Estimation Results (Covariates: BAME, Gender, Experience, and Cohort 2018 [first cohort with TBL]).

The results suggest that, when controlling for BAME and Gender, there is evidence of a significant positive TBL treatment effect at the lower and median quartiles, which disappears at the upper quartile. Artz, Jacobs, and Boessen (Citation2016) found in their study that TBL benefits all students in the top or bottom quartile of the grade point average distribution. They concluded that this learning approach is very robust for helping the entire spectrum of students’ abilities in the classroom.

To gain a better understanding of the possible role played by ethnicity and gender, we proceeded further and used regression analysis. Based on the results of , we estimated five models: the “Term-Gap” model, two “within-groups” models, and two “across-groups” models. The results are reported and discussed in the next section.

The first model, the “Term-GAP” (TG) specification, used the pooled data of all the two cohorts’ grades to explain differences in achievements between Term 2 and Term 1 at each level of progression. In this specification, the controlling factors are ethnicity (BAME), Gender, and level 6 progression, all represented by dummy variables.

The second specification focused on the performance of only Term 2 (treatment group), recorded for both cohorts at each level of progression. Thus, this model was a “within-group” (WG) type of model, and it was used to assess the effects that controlling factors such as ethnicity (BAME), Gender, and type of cohort (all expressed by dummy variables) could have on students’ Term 2 performance as they progressed to a higher level. The third model was the same as model two, but the focus was on the performance of the control group (Term 1) instead of the treatment group (Term 2).

The fourth specification focused only on the two cohorts’ final-year performances, thus only on grades of the Term 2 (treatment) group and Term 1 (control) group of the level 6 progression stage. We termed this specification the “across group” (AG) model. It was used to assess the effects of ethnicity (BAME), Gender, type of assessment, and type of cohort (all expressed by dummy variables), on students’ final-year performances. The fifth model was the same as model four, but the focus was on level 5 performances of both cohorts rather than on their final-year grades.

For each model, we ran a fixed-effect and a random-effectFootnote4 specification and tested these effects using the Hausman test. We also applied the Breusch-Pagan (BP) test to check for panel effects. The results of the tests, reported in in the appendix, indicated that, for some of the models, namely the GAP and the within-group at level 6, there was no evidence of significant differences across entities and that OLS regression was appropriate. These tests also indicated that the random-effect specification was chosen over the fixed-effect one in all the cases that required panel model estimates.

Methodology, part 2: Regression analysis and results

The results of the five estimated models are reported in .

Table 7. Regression Analysis.

Due to the presence of interaction terms across covariates, each regression’s constant term represents the reference category of each of the statistically significant dummies. The Term-Gap model reveals the presence of a negative BAME effect, which disappears totally at level 6 (the sum of the coefficient of the main effect and the interaction term effect). This result means the following two things: firstly, before the TBL intervention, BAME students tended to show a “term-gap” as their grades on more empirical assessments (Term 2) were systematically lower than their grades on more theoretical assessments (Term 1). This discrepancy did not occur to White students. Secondly, with the introduction of TBL, this term-gap disappeared at level 6. By looking at the marginal effects in , we notice a small gender effect for BAME students: at level 6, BAME male students show an improvement of this term-gap slightly higher than the BAME female term-gap.

Table 8. Marginal Effects.

One could rightly argue that a reduction in the term-gap between Term 1 and Term 2 grades could be the result of either increased performance in Term 2 or of decreased performance in Term 1 or both. To understand the reason behind this improvement in the term-gap better, we need to look at the other models specified earlier and use the information in and .

Model 3 looks at the trajectory of Term 1 grades across levels of progression, thus within the control group. In this group (essay type, more theoretical assessments), the BAME students outperformed the non-BAME students at level 5, but this grade differential disappeared at level 6, when the White students improved their grades, while the BAME students did not. The relevant column of the marginal effects () also shows that the White group’s improvement is slightly more pronounced for White females than for White males. This within-control group result of model 3 suggests that, indeed, the BAME effect found in the Term-Gap model in the final year is more likely to be driven by an improvement in the BAME students’ performance in Term 2 rather than by a drop in their grades in Term 1. This result is what model 2 also confirms: if we consider the Term 2 grades’ trajectory, thus within the treatment group, all students improved their performance in their final year, with the White students doing marginally better than the BAME students. Combining these three models, it emerges that there are some significant BAME effects within the treatment group: the TBL intervention enabled all BAME students to improve (or to avoid a worsening) in their performance in more empirical and data application tasks, while at the same time sustaining (or improving) the performance of the White group.

Lastly, models 4 and 5 reaffirm a similar narrative. When looking at the performances across the treatment and control groups for level 5 (model 5), the treatment group (Term 2) BAME students underperformed White students but outperformed them in the control group (Term 1); hence, at level 5, because the two effects counteracted each other, there is no difference between the aggregates (BAME plus White) of the treatment and control groups. This result is shown more clearly in the last column of , where the average marginal effect of the dummy “Term 2” is zero, being the average of the opposite marginal effects of the BAME versus White groups.

However, when looking at the performances across the treatment and control groups at level 6, model 4, we find a different story. The BAME and White differential performances disappear. At level 6, while all students in the control and treatment groups improved their grades, the performance of the treatment group, which coincided with the TBL initiative, showed a more substantial improvement than the control group (Term 1). This result is shown in the penultimate columns of and .

We did not find any strong gender effect: in general, females in both BAME and White groups performed marginally better than their male counterparts, but it is the BAME male group that showed the greatest catching up, reducing the grade gap across Term 1 and Term 2 tasks, possibly because they had started from a lower position.

We conclude that our TBL intervention, focusing on equality and inclusion, has benefited all students, particularly the BAME group, reducing their historical attainment gaps. Within each group, females have tended to perform marginally better than males, possibly because they are better at collaborative problem-solving (Espey Citation2018a; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Citation2017). However, BAME male students have been those who have shown the most significant overall improvement in tackling assignments with more empirical analysis and data-driven tasks.

In our view, the main reason for these encouraging results is the way we created the teams.Footnote5 We noticed that under the TBL term, all groups showed a reduction in the standard deviation and an increase in average, with two exceptions. The first exception was a group with fewer BAME students among all groups of the 2018 cohort. The following year, the second exception was the one with the lowest BAME and fewest BAME females among all groups of the 2019 cohort.

The link between gender and teamwork has been investigated by Bear and Woolley (2011) and Weber, Wittchen, and Hertel (Citation2009), who recognized the influence of female roles in motivating team collaboration. In teaching principles of microeconomics, Lage, Platt, and Treglia (Citation2000) surveyed teachers and students to compare traditional lecture-oriented teaching versus a more interactive, small group “inverted” approach, similar to TBL. Instructors noted that women students were more active and more comfortable in an inclusive and collaborative learning environment than in a traditional setting. Female students placed a higher educational value on interactive, small-group learning than male students did. Given the gender bias demographic, a more collaborative approach to learning in economics could help attract more women and create a diverse community of learners.

In a TBL context, Espey (Citation2018a) investigated how group characteristics influence team and individual grades. The study reported that having a high percentage of females and members with high GPAs in a group has an impact on team achievements. Individual performances were correlated with group gender diversity and individual effort in team activities (when triangulated with peer assessment). Artz, Jacobs, and Boessen (Citation2016) found that team ability has only a small effect on individual performance: higher-performing teams marginally improve their members’ performances by more than low-performing teams do. From an instructor’s perspective, this finding implies there is some leeway in allocating resources in team formation.

TBL: Qualitative results. Students’ feelings and voices

What do students think and feel about TBL’s more intense involvement and engagement? Fernando and Marikar (Citation2017) reported that “participatory” teaching methods are highly popular among students and their learning experience improves and intensifies significantly with group activities. Huggins and Stamatel (Citation2015), in their exploratory analysis between lecturing or TBL, concluded that students considered TBL to be more effective in improving oral communication and creative thinking skills.

To better understand the quality of student learning experience in the process and the outcomes, we observed students’ behaviors and used surveys or reflective reports to collect their views and feedback at various points of Term 1 (standard delivery) and Term 2 (TBL delivery). We organize the gathered information into three types of engagements: behavioral, cognitive, and emotional.

Behavioral engagement: Class attendance, escape room experience, and peer-to-peer evaluation

In this type of engagement, we include class attendance, contact with teammates, including peer-to-peer feedback on behavior. In terms of students’ engagement, we noticed that, with TBL, attendance was appreciably better than what we had experienced in the past with the same students.

We also observed that the camaraderie level was very high among students, and it became more intense as they engaged in TBL class activities. To prompt team bonding and identity, we provided each team with vouchers for an Escape Room activity. We asked them to submit an individual short report before Term 2 about the group’s strengths and weaknesses and their view of the overall experience. This entertaining group activity requires members’ collaboration to achieve a common goal. Students’ feedback was very positive and captured the essence of the activity. We report in some of their comments.

Table 9. Escape Room Feedback—Recurring Themes.

In the TBL term, students were asked to comment on each other’s engagement and behavior anonymously. We conducted peer-to-peer feedback twice, so students could adjust behavior if necessary. Anonymous peer-to-peer feedback is one of the TBL defining elements. Michaelsen, Davidson, and Major (Citation2014) identify four reasons that peer assessment and feedback are crucial for TBL. Firstly, to deal with the potential issue of “free-riders” in each group and promoting incentives for members to do their fair share. Secondly, it will help members to enhance both each other’s ability to work together effectively (process-related) and to contribute ideas and information (content-related). Thirdly, with groups working independently, only individual members can provide feedback. Finally, it helps team members develop interpersonal skills to provide incentives and opportunities for helping each other (Michaelsen, Knight, and Fink Citation2004).

We collected peer-to-peer evaluations via an online Peer Feedback System that allows each member of the group to send and receive anonymous feedback from each of their teammates. We used a short questionnaire and instructed students to consider factors such as preparation, contribution, respect for others, and flexibility. A summary of their comments and answers to the four questions on behavior can be found in . While feedback was anonymous to students, it was visible to us, and we could recognize trends we had observed during the TBL units and appreciate how honest and constructive this feedback was.

Table 10. Peer-to-Peer Anonymous Feedback—Recurring Themes.

Cognitive engagement: Effort to understand information and master complex skills

Under TBL, students were provided with continuous real-time feedback on their in-class work and achievements. An overwhelming number of students had a very positive experience, embraced this new pedagogy, and viewed collaborative group work as an enriching experience in fully integrating into their respective groups, having a better and more in-depth understanding of the topic area. This module received a higher student evaluation score in Term 2 (under TBL) than in Term 1 and one of the highest scores (4.7 out of 5) of the Department and the Faculty. summarizes some formal feedback received from the students.

Table 11. Students’ Views of their Learning Experience.

Emotional engagement: Control-Value theory

Emotion is a kind of internal drive that can exert a powerful effect on behavioral choice. In our application of the TBL approach, we were interested in understanding and monitoring students’ emotional engagement and their feelings and reactions to learning activities. We piloted an initiative in our second implementation of TBL to monitor students’ overall feelings about the module in both terms of the academic year to capture if and how the TBL delivery could change their in-class moods and feelings.

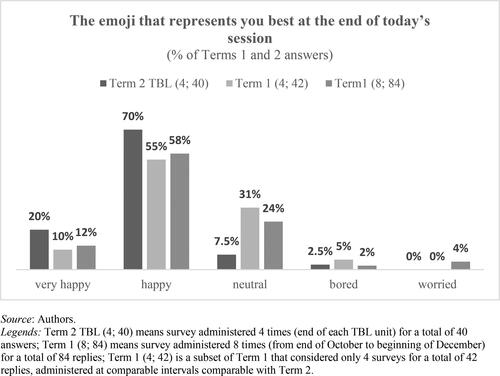

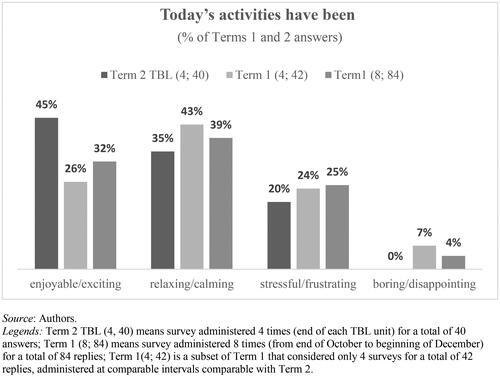

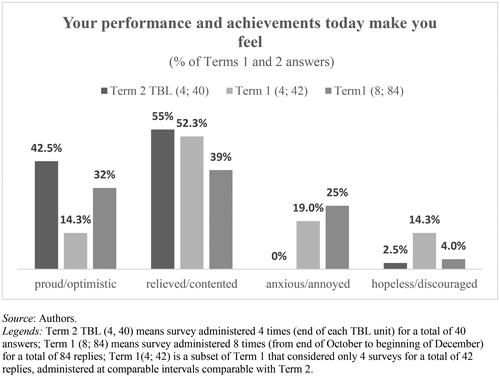

We introduced a short anonymous survey (3 questions), administered via Mentimeter, repeated at regular intervals throughout the academic year at the end of interactive teaching and learning sessions (seminars). Each student selected a coded name, known only to them, which was used throughout the year. Therefore, the survey was anonymous and enabled us to monitor each coded name’s feelings throughout the year. It was based on Control-Value Theory (CVT), one of the leading contemporary theories for mapping and measuring an individual’s feelings and emotions (Pekrun Citation2006) with learning processes and performance.

The CVT categorizes this plethora of emotions using two orthogonal dimensions: their valence (i.e., the degrees of pleasure or displeasure elicited by the task or the outcome to be achieved) and their levels of arousal or activation (i.e., the degree of stimulation and engagement that the task elicits). These two dimensions produce a range of feelings known as the “Circumplex Model” of emotions (Russell Citation1980). Students can experience four basic categories of emotions in an educational setting and a range of other emotions in between each category. For instance, if a student finds that they can master what they consider valuable, they can experience positive activating emotions (such as enjoyment, hope, and pride). These emotions are thought to promote intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, self-control and self-regulation, flexible learning strategies, and positively affect academic performance.

On the other hand, negative deactivating emotions, such as hopelessness and boredom, would reduce motivation and effort, implying adverse performance effects. The other two types of emotions, the positive deactivating ones (such as relief) and the negative activating ones (such as anger, anxiety, and shame), are more complex to analyze and can have variable effects on students’ learning. For instance, if a student anticipates a failure in a test that they believe to be important for their career goals, they will feel anxious or have anger. These negative emotions elicit extrinsic motivation in the effort to avoid failure and could simultaneously undermine intrinsic motivation and the joy of learning and prompt the use of more rigid learning strategies.

Although the links between emotions and subsequent learning and performance are complex, there is a general agreement among psychologists that the achievement emotions could significantly influence students’ learning process, academic motivation, engagement, effort, and ultimate performance. In exploring the achievement emotions in the traditional academic context, Pekrun et al. (Citation2011) showed an association between positive emotions and students’ effort, self-regulation, and an association between negative emotions and lower performances and more external control. Their study highlights the importance of designing learning environments that foster a high degree of control and high value for students.

Our pilot study suggests that the TBL experience is associated with more positive (pleasant and activating) emotions than with the standard delivery method, with almost all respondents (90%) reporting to have felt happy at the end of a TBL session, to have found the activity exciting or relaxing (80%), and to have felt proud and contented (97.5%) for their achievements of the day.

Conclusions, limitations, and future research

In our experience, team-based learning (TBL) and collaborative learning have helped to address the attainment gap by directly involving students in the classroom, offering a more interactive and inclusive learning environment. We think that, with TBL, we were able to provide a better structure and scaffolding to implement a more effective constructivist approach to teaching and, as recognized by our students themselves, enhance students’ readiness for the complex work environment. Students benefited from the regular, instantaneous, and in-class feedback. We enjoyed the whole process despite the very time-consuming nature of setting up a TBL course, and it seems that students found TBL an enriching and enjoyable learning experience.

However, we acknowledge that TBL still has several shortcomings and limitations and creates challenges for teachers and students. One of the main challenges for teachers is to design genuinely collaborative assignments where students work together on the same task in producing a single collective decision. Failing to provide such assignments can result in an inequitable and low-quality experience for individuals. Another challenge is to find relevant, tangible, and relatable tasks. The success of TBL depends directly on the nature of the task, which needs to be relevant and viable so that students can answer questions and find solutions within their knowledge base, the content of the syllabus, and their skillset. Failing to set the correct level of challenge may lead to frustration, disengagement, or boredom (Roberson and Franchini Citation2014).Footnote6

From a student’s point of view, one of the TBL challenges is the ability to connect with the group in terms of motivation and effort. Group identity requires bonding, a time-consuming process, as members need to learn to function in their respective groups. It becomes even more complicated when other differences—gender, ethnicity, age, and culture—are included.

Despite the abundant empirical and anecdotal evidence on TBL’s positive aspects, there is still a need to produce more “high-quality” experimental studies (Silz Carson et al. Citation2021; Sisk Citation2011; Liu and Beaujean Citation2017) to assess and evaluate the effectiveness of the TBL approach, taking into account the specific learning and cultural styles of the millennial students. This generational group is very different from previous ones that responded better to traditional lecture and text/exam methods. The millennials seem to be multitasking, comfortable in an electronic world, and preferring learning in a relaxed group environment (Ellis Citation2016).

Our immediate challenge, with the recent global pandemic (COVID-19), is to develop a strategy to adapt different aspects of TBL for online and blended learning delivery for i-generation students and to offer an inclusive, diverse, enriching, and enjoyable learning experience of economics. We foresee a high potential for this pedagogy for both students and teachers and believe TBL can help develop the homo economicus into a homo socialis.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no relevant financial or nonfinancial competing interests to report.

Notes

1 We bought and used IF_AT cards. Students truly enjoyed this activity, which promoted team development and interaction. We allowed two reply attempts. Once the team agreed on a group answer, students would use the card and scratch off the coating over the selected choice to see if the answer was correct. If unsuccessful, the second attempt would give two marks, half of the marks allotted for a successful first attempt.

2 In this study, we use the UK academic convention to indicate the years of academic progression with levels: levels 4, 5, 6 are used to indicate the first, second, and final year of an undergraduate academic program. The set included all failures as approved by the May PAB. Many of these failures were allowed referred or deferred coursework in the summer term and passed by submitting a piece of alternative assessment. However, to understand the impact of the intervention better and to preserve the consistency of assessment instruments, we decided: a) to keep only students’ first attempts to succeed, whether a failure or a pass, and did not replace original grades with resit grades; b) to exclude cases of nonsubmission due to reasons covered by extenuating circumstances that allowed a resit in August using an alternative instrument. Moreover, to have a balanced panel, we also excluded those students who were in placement and had returned to complete the final year and those pupils who started their final year as “direct entry” students for whom we did not have any record of their 2nd year program performance (called level 5 in the UK system). These groups are included in a subsequent study where we make use of an unbalanced panel. It is worth noticing that, despite removing those “unmatchable” 14 students, the BAME and gender composition of the balanced panel was the same as the unbalanced one. We think, therefore, that by excluding those students we did not create an issue of self-selectivity.

3 The parallel trend assumption is critical to ensure the internal validity of the DID model. It requires that, in the absence of treatment, the difference between the “treatment” and “control” groups is constant over time. Although there is no statistical test for this assumption, visual inspection is useful when using observations over many time points. As explained in this study, we had noticed that for both cohorts (and for previous cohorts), the difference between the Term 1 and Term 2 performances was stable. It has also been proposed that the shorter the period of testing, the more likely the assumption is to hold. In our case, we looked at only two years of performances for each cohort. Moreover, our two cohorts had been exposed to similar previous academic experience before the treatment because they shared the same course structure (in terms of modules, content, and assessment types at levels 4 and 5, before the treatment) and exactly the same summative tasks (at levels 5 and 6). All these factors contribute to suggesting that the parallel assumption was not violated.

4 The reason for using gender and ethnicity covariates in the RE model is that, even though these factors are “fixed” as individual characteristics and do not vary across times and types of assessments, they may nevertheless exert time-variant effects because some kind of assessments can be “more” congenial to a specific gender or ethnic group. To avoid gender/BAME stereotypes and considering that the purpose of the intervention was to reach equity and inclusion in formative assessment, we controlled for Gender and BAME, allowing these factors to have differential effects across assessments and progression levels.

5 We created 7 teams of 6 students each for Cohort 1 (2018) and 5 teams for Cohort 2 (2019), of which 3 teams had 5 members and 2 teams had 6 members. The total number of students in cohorts was 42 and 27, respectively, which totaled to 69 students in the unbalanced panel. However, the balanced panel had a reduced number of students (55) due to consistency adjustments explained in note 2.

6 From the students’ formal and informal feedback, we conclude that our TBL experience’s success depended considerably on the additional resources, financial and nonfinancial, utilized in the delivery of this course. In particular, we received funds to buy vouchers for team building activities (escape room) and training to deliver TBL. We also dedicated a significant amount of time and made constant efforts to plan, organize and implement the TBL initiative.

References

- Abio, G., M. Alcaniz, M. Gomez-Puig, G. Rubert, M. Serrano, A. Stoyanova, and M. Vilalta-Bufi. 2019. Retaking a course in economics: Innovative teaching strategies to improve academic performance in groups of low-performing students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 56 (2): 206–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1389289.

- Artz, G. M., K. Jacobs, and C. R. Boessen. 2016. The whole is greater than the sum: An empirical analysis of the effect of team-based learning on student achievement. NACTA Journal 60 (4): 405–11.

- Bear, J. B., and A. W. Woolley. 2011. The role of gender in team collaboration and performance. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 36 (2): 146–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1179/030801811X13013181961473.

- Beaudin, L., A. N. Berdiev, A. S. Kaminaga, S. Mirmirani, and E. Tebaldi. 2017. Enhancing the teaching of introductory economics with team-based, multi-section competition. Journal of Economic Education 48 (3): 167–75. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2017.1320608.

- Betta, M. 2016. Self and others in team-based learning: Acquiring teamwork skills for business. Journal of Education for Business 91 (2): 69–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1122562.

- Bruner, J. S. 1960. The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Clerici-Arias, M. 2021. Transitioning to a team-based learning principles course. Journal of Economic Education 52 (3): 249–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1925184.

- Cohen, J., and C. Robinson. 2018. Enhancing teaching excellence through team-based learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 55 (2): 133–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2017.1389290.

- Davidson, N., C. H. Major, and L. K. Michaelsen. 2014. Small-group learning in higher education—Cooperative, collaborative, problem-based, and team-based learning: An introduction by the guest editors. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 25 (3&4): 1–6. http://celt.miamioh.edu/ject/issue.php?v=25&n=3%20and%204.

- Dolmans, D., L. Michaelsen, J. Van Merrienboer, and C. Van Der Vleuten. 2015. Should we choose between problem-based learning and team-based learning? No, combine the best of both worlds! Medical Teacher 37 (4): 354–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.948828.

- Donabedian, A. 1980. Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring. Volume 1. The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

- Ellis, N. 2016. Reaching the millennial student: Comparative analysis of team-based learning student outcomes over traditional lecture/test instructional methods. Presentation at Interior Design Educators Council Conference. Portland, Oregon, March 9–12. Interior Design Matters: 2016 IDEC Annual Conference Proceedings, 358–61.

- Espey, M. 2018a. Diversity, effort, and cooperation in team-based learning. Journal of Economic Education 49 (1): 8–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2017.1397571.

- ——— 2018b. Enhancing critical thinking using team-based learning. Higher Education Research & Development 37 (1): 15–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344196.

- Fernando, S., and F. Marikar. 2017. Constructivist teaching/learning theory and participatory teaching methods. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching 6 (1): 110–22. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1157438.pdf. doi: https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v6n1p110.

- Green, A. 2021. TBL Fridays: Using team-based learning to engage in policy debates in an introductory class. Journal of Economic Education 52 (3): 257–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1925186.

- Haidet, P., K. Kubitz, and W. T. McCormack. 2014. Analysis of the team-based learning literature: TBL comes of age. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 25 (3-4): 303–33. http://celt.miamioh.edu/ject/issue.php?v=25&n=3%20and%204.

- Hettler, P. L. 2015. Student demographics and the impact of team-based learning. International Advances in Economic Research 21 (4): 413–22. https://doi.org/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11294-015-9539-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-015-9539-7.

- Huggins, C. M., and J. P. Stamatel. 2015. An exploratory study comparing the effectiveness of lecturing versus team-based learning. Teaching Sociology 43 (3): 227–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X15581929.

- Ibrahim, I. A., and W. F. Saleem. 2018. Team based learning: An innovative teaching strategy for enhancing students’ engagement. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 6 (1): 159–74. https://www.ijier.net/ijier/article/view/940/692. doi: https://doi.org/10.31686/ijier.vol6.iss1.940.

- Imazeki, J. 2015. Getting students to do economics: An introduction to team-based learning. International Advances in Economic Research 21 (4): 399–412. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11294-015-9541-0. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-015-9541-0.

- Jeno, L. M., A. Raaheim, S. M. Kristensen, K. D. Kristensen, T. N. Hole, M. J. Haugland, and S. Maeland. 2017. The relative effect of team-based learning on motivation and learning: A self-determination theory perspective. CBE—Life Sciences Education 16 (4): ar59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-03-0055.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 1989. Cooperation and competition: Theory and research. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 1999. Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Johnson, D. W., and R. T. Johnson. 2005. New developments in social interdependence theory. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 131 (4): 285–358. doi: https://doi.org/10.3200/MONO.131.4.285-358.

- Johnson, D. W., R. T. Johnson, and K. A. Smith. 2014. Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 25 (3&4): 85–118. http://celt.miamioh.edu/ject/issue.php?v=25&n=3%20and%204.

- Lage, M. J., G. J. Platt, and M. Treglia. 2000. Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. Journal of Economic Education 31 (1): 30–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480009596759.

- Larkin, H., and A. Richardson. 2013. Creating high challenge/high support academic environments through constructive alignment: Student outcomes. Teaching in Higher Education 18 (2): 192–204. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.696541.

- Liu, S. N. C., and A. A. Beaujean. 2017. The effectiveness of team-based learning on academic outcomes: A meta-analysis. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 3 (1): 1–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000075.

- Michaelsen, L. K., N. Davidson, and C. H. Major. 2014. Team-based learning practices and principles in comparison with cooperative learning and problem-based learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 25 (3&4): 57–84. http://celt.miamioh.edu/ject/issue.php?v=25&n=3%20and%204.

- Michaelsen, L. K., A. B. Knight, and L. B. Fink. 2004. Team based learning: A transformative use of small groups in college teaching. Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2017. PISA 2015 results (volume V): Collaborative problem solving. Paris: OECD, Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). doi: https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264285521-en.

- Parmelee, D., P. D. Hudes, and L. K. Michaelsen. 2013. Team-based learning. In A practical guide for medical teachers, 4th ed., ed. J. Dent and R. Harden. 173–82. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier.

- Parmelee, D., L. K. Michaelsen, S. Cook, and P. D. Hudes. 2012. Team-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE guide no. 65. Medical Teacher 34 (5): e275–e287. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179.

- Pekrun, R. 2006. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumption, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review 18:315–41. https://doi.org/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9.

- Pekrun, R., T. Goetz, A. C. Frenzel, P. Barchfeld, and R. P. Perry. 2011. Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology 36 (1): 36–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002.

- Roberson, B., and B. Franchini. 2014. Effective task design for the TBL classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 25 (3&4): 275–302. http://celt.miamioh.edu/ject/issue.php?v=25&n=3%20and%204.

- Ruder, P., M. H. Maier, and S. P. Simkins. 2021. Getting started with team-based learning (TBL): An introduction. Journal of Economic Education 52 (3): 220–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1925187.

- Russell, J. A. 1980. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39 (6): 1161–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714.

- Silz Carson, K., H. Adams, J. Gonzalez-Ramirez, C. Heinicke, J. M. Latham, M. Maier, C. L. Malakar, P. Ruder, and S. P. Simkins. 2021. Challenges and lessons: Design and implementation of a multi-site evaluation of team-based learning. Journal of Economic Education 52 (3): 241–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1925185.

- Simkins, S. P., M. H. Maier, and P. Ruder. 2021. Team-based learning (TBL): Putting learning sciences research to work in the economics classroom. Journal of Economic Education 52 (3): 231–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1925188.

- Sisk, R. J. 2011. Team-based learning: Systematic research review. The Journal of Nursing Education 50 (12): 665–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20111017-01.

- Skinner, B. F. 1974. About behaviorism. New York: Knopf.

- Swanson, E., L. V. McCulley, D. J. Osman, N. Scammacca Lewis, and M. Solis. 2019. The effect of team-based learning on content knowledge: A meta-analysis. Active Learning in Higher Education 20 (1): 39–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417731201.

- Weber, B., M. Wittchen, and G. Hertel. 2009. Gendered ways to motivation gains in groups. Sex Roles 60 (9-10): 731–44. https://doi.org/https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s11199-008-9574-4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9574-4.

- Yuretich, R. F., and L. C. Kanner. 2015. Examining the effectiveness of team-based learning (TBL) in different classroom settings. Journal of Geoscience Education 63 (2): 147–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.5408/13-109.1.

Appendix

Table A1. Overall Term-GAP.