ABSTRACT

Literature presents evidence of the exponential rise of distributed leadership both as a focus of research and as leadership development in education in the twenty first century (Hairon, S., and J. W. Goh. 2015. “Pursuing the Elusive Construct of Distributed Leadership: Is the Search Over?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 43 (5): 693–718; Hall, D. 2013. “The Strange Case of the Emergence of Distributed Leadership in Schools in England.” Educational Review 65: 467–487), in addition to the growing criticism of the theory’s dominance and its ‘acquired taken-for-granted status’ (Lumby, J. 2016. “Distributed Leadership as Fashion or fad.” Management in Education 30 (4): 161–167). This paper thus seeks to provide a systematic review of the literature on distributed leadership published between 2010 and 2022 through a methodical collection, documentation, scrutiny, and critical analysis of the research publications. The review seeks to identify trends in distributed leadership knowledge production according to the study type/purpose, topical foci, methodological approach, focus group, and geographic distribution via a narrative synthesis approach (Oplatka, I., and K. Arar. 2017. “The Research on Educational Leadership and Management in the Arab World Since the 1990s: A Systematic Review.” Review of Education 5 (3): 267–307).

Introduction

We inhabit a ‘leadership-obsessed culture’ where leadership is often considered as the only determining factor of the success or otherwise of an educational organisation, resulting in a society pushing us to deny ‘ambiguities, incoherencies, and shifts in our great leaders’ (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011, 3). The emergence of distributed leadership as a concept was propelled by the recognition of the limitations of the ‘charismatic hero’ (Fullan Citation2005), as well as the need to ease the burden of principals and senior leaders who have become overloaded (Hartley Citation2010a). Diamond and Spillane (Citation2016) shifted the unit of analysis to the leadership activity itself, due to their dissatisfaction with traditional approaches to school leadership exploration with their often-exclusive focus on the traits and characteristics of people in leadership positions, and their thinking in particular organisational contexts, ignoring people who did not hold traditional leadership positions.

The rise of distributed leadership is part of a wider proliferating rise of leadership studies in the Educational Leadership, Management and Administration (ELMA) field as evidenced in meta-analyses mapping knowledge production in the field. Hallinger and Kovacevic (Citation2021) identify four main ‘schools of thought’ across four generations of ELMA scholarship, spanning across Leadership for Learning; Leading Change; Leading Teachers; and School Effectiveness and School Improvement, demonstrating a paradigm shift that remodelled the research focus alongside the identity of ELMA as a field of study. Taking a topographical perspective, Tian and Huber (Citation2021) synthesise the following trends in ELMA knowledge production between 2007 and 2016, namely theoretical development of instructional, transformational, distributed, and system leadership; the increasing critique of neoliberalism and New Public Management in education systems; increased awareness of local contexts and adaptation of ELMA theories accordingly, in addition to the rising value of comparative studies.

Literature presents evidence of the exponential rise of distributed leadership both as a focus of research and as leadership development in education in the twenty first century (Hairon and Goh Citation2015; Hall Citation2013), as well as a popular site for theorising, with major projects and texts which seek to present models and evidence of effective practice in schools (Gunter, Hall, and Bragg Citation2013). In fact, distributed leadership emerges as the most frequently used concept employed to theoretically frame educational leadership research in the field from 2005 to 2014, displaying robust interconnections and co-occurrence with concepts such as trust, instructional leadership, transformational leadership, organisational theory, and social justice theory. Wang (Citation2018) concludes that this is evidence of the evolution rather than a paradigm shift of the incremental knowledge accumulation in the educational leadership research field. Running parallel to this growth in distributed leadership has been the growing criticism of the theory’s dominance and its ‘acquired taken-for-granted status’ (Lumby Citation2016, 161). Harris and DeFlaminis (Citation2016, 141) thus argue that ‘No other leadership concept, it seems, has caused so much controversy, angst and debate as distributed leadership’. Adopting a retrospective approach, Gronn (Citation2016, 172) questions the trajectory of distributed leadership, concluding that ‘because distributed leadership provides merely part of the story of what goes on in educational organisations … it has lost the analytical gloss that once it may have had’, furthermore proposing a leadership configuration following a hybrid pattern considering degrees of co-existing individualism and collectivism. Moreover, school leadership distribution perceptions and practices vary across countries, with country or governmental context proving to be a vital consideration in a global investigation of distributed leadership due to the impact of policy on distributed leadership formations (Liu Citation2020), as demonstrated by Printy and Liu’s (Citation2021) cross-country study using TALIS 2013 data. OECD country policies related to professional development, teacher and student appraisal, school evaluation, initiatives in instructional leadership, accountability demands, encouragement in team building and mentoring, in addition to authority for various leadership responsibilities within an individual country could act as either a blessing or a bane for leadership distribution.

Education practitioners and policymakers have been lured by the attractive notion of leadership distribution for various reasons. Mayrowetz (Citation2008) explores the value of distributed leadership in a pragmatic sense, pointing out four benefits that can be generated through its practice. It may be regarded as a theoretical lens for exploring the leadership dynamics; as a means for furthering democracy (despite distributed leadership and democracy being very distinct, as outlined by Woods Citation2004); as a way of improving organisational efficiency and effectiveness; and finally, as leading towards human capacity-building. A distributed perspective focuses on how leadership practice is ‘stretched over’ people; how school subject matter moulds leadership practice; and how authority and legitimacy procedures impact on the relationship between the policy environment and teaching practice (Diamond and Spillane Citation2016).

Definitions of distributed leadership abound in literature, with the past decade witnessing the emergence of variegated perspectives that have contributed to contestation and debate across ELMA (Youngs Citation2020). Harris (Citation2005, 1) describes it as ‘collective leadership responsibility rather than top-down authority’, subscribing to Spillane’s (Citation2005) ‘leader plus’ perspective, moving us from a ‘person solo’ to a ‘person plus’ perspective, suggesting multiple leaders at multiple levels. This is premised on a collective approach to capacity building in schools (Harris and Lambert Citation2003) through a recognition that leadership practice is constructed through shared action and interaction. Bennett et al. (Citation2003) identify three characteristics of distributed leadership: as an emergent property of a network of interacting individuals; operating within undefined boundaries that can only vary along a continuum between wide and restricted; and with widely distributed expertise and leadership opportunities. Zepke (Citation2007, 305) builds on Gronn’s (Citation2002, 543) definition of distributed leadership as ‘structurally conjoint agency’, describing it as a ‘community for action’ where power flows from leader to leader as new leadership roles emerge and are nurtured. Mayrowetz (Citation2008, 425) argues that the term ‘distributed leadership’ has been widely applied to notions of school leadership and adapted in education discourses – leading to the coexistence, persistence, and prevalence of diverse conceptualizations and interpretations of the term – thus encouraging researchers to ‘talk past each other’. Harris (Citation2013a) distinguishes one common misuse of the term in literature which renders it more difficult to demarcate its ‘precise’ meaning – using it as an umbrella term to encompass any mode of shared, collaborative, or extended leadership practice. Confusion is further engendered by its positioning as the antithesis of top-down, hierarchical leadership – a position critiqued by Harris (Citation2013a, 548), for whom distributed leadership is a form of co-leadership involving ‘both formal and informal leaders, it is not an either/or’ (emphasis added). It is this ‘loose’ application of the term which may lead to some confusion – in the words of Hartley (Citation2010a, 281), ‘If distributed leadership is indeed a loose cannon, open to doctrinal disputes, then it is perhaps of little surprise that its operationalisation within empirical research is less than consistent’. In tracing the conceptual development and thought of distributed leadership in ELMA, Youngs (Citation2022) reveals how entitative ontology informs most distributed leadership in ELMA that has distanced itself from leadership studies literature over time. This developed notwithstanding the fact that the nomenclature ‘distributed leadership’ first appeared in the leadership field in the 1980s, making its first appearance in a small number of ELMA publications in the 1990s to becoming a commonplace term in ELMA from the start of the millennium. It is for these reasons (conceptual plurality and the absence of a clearly defined model) that I decided to use the term ‘distributed leadership’ only, rather than including synonyms in the search, as well as requiring the term to be located within the title of the publication. (Further details are provided in the Methodology section).

Notwithstanding, the dearth of research surrounding the meanings and implications of distributed leadership (Storey Citation2004), as well as the under-theorisation of identity and power issues within distributed leadership (Crawford Citation2012) led to empirical research in which the author explored distribution dilemmas within policy-mandated multisite school collaboratives (Mifsud Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c), followed by a problematization of this particular school leadership discourse through Foucault’s notion of governmentality (Mifsud Citation2021). This paper seeks to make a further contribution to the literature narrative around the concept of distributed leadership by identifying trends in distributed leadership knowledge production via a systematic review of the literature published between 2010 and 2022, adding to previous analyses covering empirical research conducted up to the last decade (Gunter, Hall, and Bragg Citation2013; Tian, Risku, and Collin Citation2015).

The review was guided by the following research questions:

What is the nature of the literature in terms of study type and purpose (empirical, theoretical/conceptual, review/commentary)?

What research topics and/or conceptual models are addressed in the distributed leadership publications between 2010 and 2022?

What methodological approaches (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) have been adopted and data collection tools used?

What is the geographic distribution of the distributed leadership literature published globally?

The following section outlines the methodological approach adopted that enabled me to narrow down the ‘canon’ of literature on distributed leadership upon which this systematic literature review drew to identify trends in the distributed leadership literature narrative.

Methodology

The main conceptual framework followed for this systematic review of literature on distributed leadership was that developed by Hallinger (Citation2013), that has also been adopted by other systematic reviews of educational leadership (for example, Bellibas and Gumus Citation2019; Gumus et al. Citation2018) combined with aspects from Oplatka and Arar’s (Citation2017) methodology in relation to the literature search procedure and data analysis (as will be explained in detail further on in this section). As the central topics guiding my research questions and goals together with the conceptual perspective guiding the review have been outlined in the preceding sections, I will now delineate the sources and types of data employed; data extraction; data evaluation, analysis, and synthesis; concluding with the major results, limitations, and implications of the review.

Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were selected as the primary search engines for the electronic sourcing of publications. An advanced search for articles with all of the words ‘distributed leadership in education’ between 2010 and 2022 anywhere within the article yielded 1,100,000 results. This was considered to be very broad, so given the very specific focus of the review, the search was narrowed down to key terms present only in the title of the publication, rather than anywhere within the article. The following search terms were used: ‘distributed leadership in education’; ‘leadership distribution’; ‘distributed leadership model’; ‘distributed leadership school principals’; ‘distributed leadership theory’; ‘challenges of distributed leadership’; ‘implementation of distributed leadership’; and ‘distributed leadership policy’, yielding a total of 296 results.Footnote1 This also included a manual search via the search engines of the journals listed in that featured the highest number of articles, in order to ensure that all relevant articles with ‘distributed leadership’ in the title were included. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied to further narrow the search and yield the sources and type of data satisfying the purpose of the review. The focus of empirical research had to encompass compulsory schooling covering primary and secondary levels, thereby excluding both further and higher education as well as the field of early childhood studies where the context in early childhood is notably different from schools. Journal articles and chapters were included, while theses, conference papers and grey literature were not considered due to issues of peer review. No minimum number of citations were required for inclusion purposes. English language peer-reviewed journals by the major publishers (Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Sage, Elsevier, Emerald, and Wiley, among others) were included, thus ensuring exhaustive coverage in terms of depth and breadth in relation to researchers’ academic career stages across the widest geographical distribution possible. I repeated both the manual and electronic searches for publications until I was confident that all likely sources had been exhausted, by striving to provide a comprehensive coverage of all the works published about distributed leadership in compulsory schooling between 2010 and 2022. I am aware, however, that even the most thorough review may sometimes fail to cover the entire scope of studies on the most specific of topics. 128 publications across 46 English language journals made up the ‘canon’ of literature for this review. The publications from this ‘canon’ cited in this article are marked with an asterisk (*) in the reference list. Out of these 128 publications, 16 are book chapters. A list of the journals (presented in alphabetical order) is presented in below.

Table 1. Journals in which the distributed leadership articles were published between 2010–2022.

The next step involved reading all the publications to extract the relevant data for analysis and synthesis in response to the research questions. The following data was collected: author, title, and date of publication; journal; country where empirical research was undertaken; context (primary or secondary); key terms; main issues/topic; empirical or theoretical; methodology (if empirical); and the focus group of the publication. This data was entered in an Excel spreadsheet as raw text and the various rows were colour coded according to the methodological approach adopted (theoretical – bright blue, empirical/qualitative – yellow, empirical/quantitative – red, empirical/mixed methods – light green). This coding allowed me to select and sort data, thus facilitating presentation according to study type to initiate evaluation, analysis, and synthesis. Notwithstanding my use of descriptive statistics to indicate trends in the variables under exploration, the main thrust of this review being qualitative, a narrative synthesis that ‘explores heterogeneity descriptively rather than statistically and is appropriate for use with results from different types of empirical research’ (Booth, Papaioannou, and Sutton Citation2012, 91) was carried out. This allowed me to construct an initial framework of themes by content according to the methodological approach adopted. I consider my critical-synthesis approach to be somewhat distinctive from other research mapping projects (as outlined in McGinity, Heffernan, and Courtney Citation2022), however, as the latter declared, I would like to clarify that:

[My] judgement reflects [my] positioning as critical scholar; undoubtedly, school-effectiveness researchers would have come to different conclusions. [I] see this not as evidence of a bias to be eradicated, but of self-reflexivity, which, as critical sociologist of educational leadership, is an integral aspect of trustworthiness … [I] refute the notion that this is the best way to know the field; [I] insist on the important role of qualitative, subjective interpretation in typologising and mapping, and relish those moments of contestability in the outcomes (Citation2022, 223).

Data overview: some preliminary statistics

I will now present some preliminary descriptive statistics that expound the empirical research trends in distributed leadership in compulsory schooling settings published between 2010 and 2022, that situates distributed leadership within the educational leadership scenario, before moving on to the narrative synthesis that qualitatively explores an analysis of this particular research discourse within a framework of study type/purpose, research focus/topic, and methodology.

Academics investigating the concept of distributed leadership between 2010 and 2022 published their outputs in 46 peer-reviewed English language academic journals, as already outlined in the previous section. The highest number of articles (n = 25) were published in Educational Management Administration and Leadership, while the International Journal of Leadership in Education emerged as the next preferred publication outlet (n = 13). The rest of the academic journals featured in each had 5 or less publications featuring distributed leadership directly in the title. This concurs with McGinity et al.’s (Citation2022) observation regarding publication sites, in terms of the field being scattered beyond those journals with a sole focus on educational leadership. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, published by Sage with a 5-year impact factor of 4.297 and the 2021/2022 impact factor retained at 4.208, remains the journal of choice for many as it celebrates its golden anniversary. The International Journal of Leadership in Education, published by Taylor and Francis, with an impact factor of 1.45, also serves an international audience in terms of submissions and readership audience. Empirical research has been carried out in 28 specific countries spanning over the 5 continents of Europe, North America, Asia, Australia, and Africa, besides the 32 countries participating in the ‘Teaching and Learning International Survey’ (TALIS) 2013, data from which was used as a secondary source to examine variables contributing to or hindering the practices of distributed leadership. The internationalisation of the educational leadership field concurs with previous assertions regarding global engagement in empirical research (Hallinger and Chen Citation2015; McGinity, Heffernan, and Courtney Citation2022). It is interesting to note the geographical distribution of empirical research both across and within continents. Europe came out as the leading continent with a number of its countries providing the research site for 28 studies, with North America closely following at 25 empirical research publications. Asia remains a strong contender with 23 empirical research publications, with Australia and Africa exhibiting a very weak presence of empirical research in distributed leadership. It is also worth mentioning that no studies were conducted in South America. European studies are dominated by the United Kingdom and Finland, with the USA dominating North America by a notable majority. On the other hand, Asian studies are predominantly from Singapore. Moreover, most of the studies are from English-speaking countries despite the educational leadership field in terms of distributed leadership research is spreading to wider linguistically diverse contexts. A list of the countries, presented per continent, together with the number of empirical studies in each is presented in below.

Table 2. Geographical distribution of empirical research.

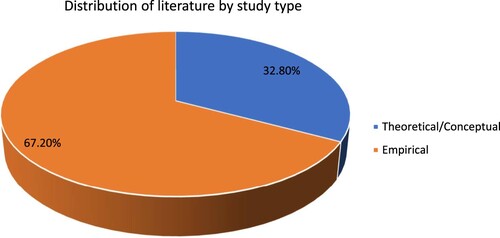

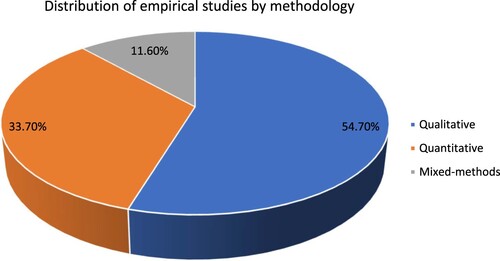

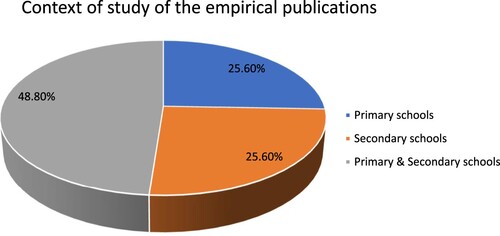

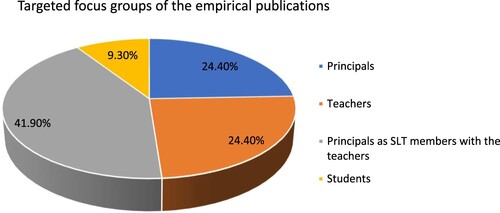

One third of the publications were theoretical (n = 42 out of 128, 32.8%), while the rest were empirical (n = 86 out of 128, 67.2%) (). The methodological approach adopted tipped the scales towards the qualitative at 54.7% (n = 47 out of 86), followed by the quantitative studies at 33.7% (n = 29 out of 86) and also including 11.6% of mixed-methods papers (n = 10 out of 86) (). The context was divided equally among primary and secondary education (n = 22 each, at 25.6%), with almost double the number of studies (n = 42, at 48.8%) tackling both levels of compulsory schooling (). In terms of the targeted focus groups, there was an identical number of papers directed at principals and teachers separately (n = 21 papers per category, at 24.4%), with almost the double amount targeting both the principals as Senior Leadership Team members with the teachers (n = 36 publications, at 41.9%), with another small number (n = 8 publications, at 9.3%) including students (). The percentages of these four variables are depicted in the figures below, according to study type; methodology; context; and target group. The next section presents a narrative synthesis of the main themes that emerged from data analysis.

Theoretical underpinnings of distributed leadership as presented in the literature

A narrative synthesis of the 42 literature sources representing theoretical/conceptual studies of distributed leadership yielded four main approaches as taken up by the educational leadership scholars, that I encapsulate as: 1) exploring the rationale behind the dominance of distributed leadership in the educational leadership field; 2) problematising distributed leadership as the ideal type for educational leadership theory, policy, and practice; 3) querying the implementation of distributed leadership in schools and the effectiveness of its transformative potential (in school reform); and 4) attempting to map distributed leadership approaches and conceptual dimensions. These identified themes fall broadly within the critical, and socially critical positions of mapping distributed knowledge production as outlined by Gunter, Hall, and Bragg (Citation2013).

Why does distributed leadership dominate the educational leadership field?

Bolden (Citation2011) reviews conceptual and empirical literature on the concept of distributed leadership in order to identify its origins, key arguments and areas for further development. Consideration is given to the similarities and differences between distributed leadership and related concepts, including ‘shared’, ‘collective’, ‘collaborative’, ‘emergent’, ‘co-‘, and ‘democratic’ leadership. Despite the relatively common theoretical bases, usage of these concepts is relative and contextual. Bolden (Citation2011) further notes that despite the rapid growth of distributed leadership theory since the turn of the twenty-first century, research remains restricted to the field of school education, carried out by UK academics to a larger extent than US-based academics. The geographic research dimension has shifted as the present systematic literature review has shown evidence of interest in and engagement with distributed leadership in schools by both UK and US-based academics. Bolden (Citation2011) advocates a ‘critical’ perspective in the adoption of distributed leadership, that facilitates reflection on the purposes and discursive mechanisms of distributed leadership, while simultaneously considering the ‘rhetorical’ significance of distributed leadership in the (re)construction of leader identities and mobilisation of collective engagement. ‘The key contribution of distributed leadership, it would seem, is not in offering a replacement for other accounts, but in enabling the recognition of a variety of forms of leadership in a more integrated and systematic manner’ (Citation2011, 264).

While Crawford (Citation2012) acknowledges other approaches to shared leadership, she uses distributed leadership to explore how this idea has become part of the rhetoric of both leadership practice and policy, ‘seized upon by schools and policymakers’, with the result of academics finding space for both solo and distributed leadership in organisations, but apparently forgetting the idea of the school as a ‘complex, adaptive, living organism’ (Citation2012, 616). Consequently, Lumby (Citation2016) suggests that the dominance of distributed leadership ‘can best be understood as a fashion or a fad rather than as a rational choice’ (Citation2016, 161), given its growth as the preferred leadership concept. The techniques used to privilege distributed leadership are based on logical, emotional, and moral arguments. Lumby (Citation2016) further argues that the focus on distributed leadership serves as a displacement activity, drawing people’s attention away from the main purpose of leadership that revolves around addressing the rampant inequality of opportunities experienced by students in school settings.

Rhetoric versus reality: is distributed leadership the ideal model in practice?

Academics have sought to problematise distributed leadership as the ideal ‘model’, mostly drawing on the argument of the rhetoric versus reality disparity in practice. Corrigan (Citation2013) contrasts the oppositional messages found in the literature, while examining differences between theory and practice associated with its application. More specifically, the treatment of power and accountability within the distributed leadership theoretical framework is difficult to reconcile. Corrigan (Citation2013) questions the theory’s resurgence given the inherent problems associated with its theory and practice. Woods (Citation2016) reiterates that a much greater understanding is needed of power in the practice in distributed leadership, that is characterised by multiple authorities constructed in the interactions between people. Rather than the existence of a uniform hierarchy of formal authority, people’s positioning is dynamic and changeable. Lumby (Citation2013) explores the ways power is enacted in the theorisation of distributed leadership and its eventual promotion. Opportunities to contribute to leadership are unequal while silence on persistent structural barriers remains. The theory’s ‘confusions, contradictions and utopian depictions’ are argued to be ‘a profoundly political phenomenon, replete with the uses and abuses of power’ (Citation2013, 581).

Likewise, Youngs (Citation2020) calls for the further development of critical perspectives related to power and issues of social justice in distributed leadership, with Lumby (Citation2019) propagating distributed leadership in schools as an ‘ideal’ type suitable for post bureaucratic organisations. Jarvis (Citation2021) argues how both ‘collegiality’ and ‘distributed leadership’ have occasioned a good deal of debate and are used interchangeably due to their conceptual elasticity. He thus attempts to clarify their meanings in relation to each other, with collegiality as an approach characterised by equality whereas distributed leadership is more aligned with utility, concluding that ‘The theoretical base for educational leadership will, at the very least, have to undergo a measure of stress-testing in the near future’ (Citation2021, 4).

A relatively small amount of literature has also sought to problematise the distributed leadership concept from a social theory lens. Mifsud (Citation2021) problematises this particular school leadership discourse drawing on the work of Michel Foucault, more specifically his notion of governmentality, with a focus on the analytics of government. Distributed leadership, perceived as one of the various educational leadership discourses, emerges as a regime of government, an assembling process, and a mode of subjectification. School leadership is presented as being about distributed leadership to foster empowerment and autonomy, where the governmentality at play thus uses distributed leadership as a means of attaining the desired leadership goals (Gillies Citation2013). Hartley (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) takes a different stance by drawing on social theory to explore the notion of bureaucracy in educational organisations. Drawing upon the recent social theory of the firm proposed by Paul Adler and Charles Heckscher, he applies the concept of collaborative community to distributed leadership. In another publication, Hartley (Citation2010a) applies Burrell and Morgan’s (Citation1979) widely-cited ‘Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis’ to research on distributed leadership in education, revealing that as an idea, distributed leadership seems to recognise the lessening/easing of rigid demarcations, but as a practice it impacts against state-sponsored standardisation, thus ‘the heterarchy of distributed leadership resid[ing] uneasily within the formal bureaucracy of schools’ (Citation2010b, 282, original emphasis).

The implementation of distributed leadership and the effectiveness of its transformative potential in schools

What are the implications of distributed leadership (as a theory, policy, and practice) for those in formal leadership positions in schools? Distributed leadership implies a fundamental re-conceptualisation of leadership as practice, while challenging conventional wisdom about the relationship between formal leadership and organisational performance (Harris Citation2013b). ‘The “so what” of distributed leadership is the recognition that the core task of the formal leader is to support those with the expertise to lead, wherever they reside within the organization’ (ibid, 551). However, distributed leadership implies shifts in power, authority, and control. The role of the principal, in particular, is affected and changed as leadership is more widely shared within the organisation (Harris Citation2012). Researchers located in the non-Western context investigate the numerous and diverse factors which have prevented the actualisation of distributed leadership in developing countries (e.g. Williams Citation2011; Salahuddin Citation2010). According to Williams (Citation2011), this is due to overlapping factors in which context, people, and practice interrelate. Context-based factors reside in the remnants of the authoritarian ethos; a tradition of teacher non-participation in the decision-making process at school level; the under-representation of women in leadership positions; the slow pace of the implementation of education policy; and sporadic funding for staff development programmes.

Literature also provides examples of research-informed frameworks for advancing meaningful school improvement using a distributed leadership approach (Supovitz, D'Auria, and Spillane Citation2019). On what should leaders focus their attention and how should they prioritise their improvement efforts? How can they identify, understand, and make headway on the difficult challenges that will substantially enhance the educational experiences of their students, and how can they bring their staff together with commitment around these improvement efforts? Little attention has been paid to the effectiveness of distributed leadership despite its rising popularity in research (Jambo and Hongde Citation2020). The looseness and breadth of the distributed leadership concept pose a threat to its transformative potential leading to improvements in classroom practices and student learning outcomes. Hence, Hairon, Goh, and Lin (Citation2014) tease out three dimensions: empowerment; interactive relations for shared decisions; and leadership development, that aid the transformative potential of distributed leadership, with sensitivity to the local context.

Mapping distributed leadership approaches and conceptual dimensions

Thorpe, Gold, and Lawler (Citation2011) offer a means by which forms of distributed leadership might be conceptualised to be better incorporated into researchers’ scholarship and research to extend the contributions to the more analytical and critical literature on distributed leadership, given the presence of normative approaches in the developing field of distributed leadership.

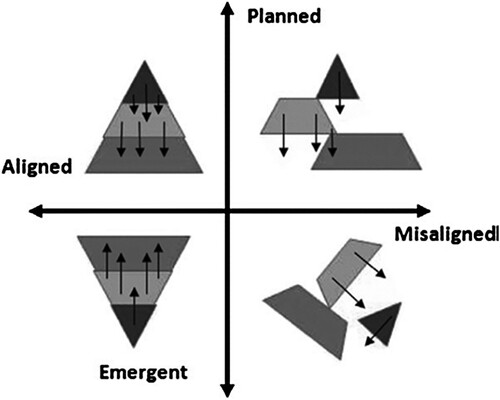

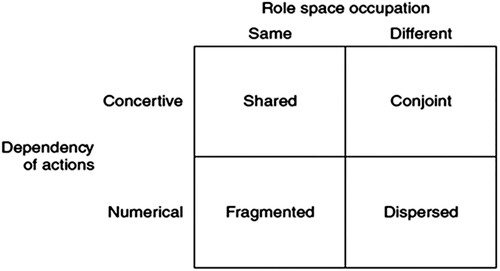

As illustrated in below, they plot the development of thinking on distributed leadership along two dimensions, 1) the continuum between ‘planned’ activity at one end to ‘emergent’ activity at the other; and 2) the continuum between ‘aligned’ activity and ‘non-aligned’. These dimensions offer four quadrants to provide a framework for discussions of distributed leadership: 1) the aligned-planned quadrant is ‘classical distributed leadership’; 2) the misaligned-planned is ‘mis-planned distributed leadership’; 3) the emergent-aligned ‘emergent distributed leadership’; and 4) the misaligned-emergent ‘chaotic distributed leadership’. ‘Classical Distributed Leadership’ is the model most familiar to us. With ‘Mis-planned Distributed Leadership’, there is the intention to use distributed leadership but either the structures are inappropriate or the people ambivalent. ‘Emergent Distributed Leadership’ recognises the informality and spontaneity of leadership configurations coming from different points within the organisation. ‘Chaotic Leadership’ may develop locally but in haphazard ways, with a focus on local contexts and goals. Feng et al. (Citation2017) build on Thorpe et al.’s (Citation2011) framework, coming up with four types of distributed leadership combinations: 1) ‘shared distributed leadership’; 2) ‘conjoint distributed leadership’; 3) ‘fragmented distributed leadership’; and 4) ‘dispersed distributed leadership’, all based on ‘dependency of actions’ that may be concertive or numerical, and ‘role space occupation’ that varies between sameness and difference.

Figure 5. Dimensions of distributed leadership (adapted from Thorpe, Gold, and Lawler Citation2011, 244).

Fitzsimons, James, and Denyer (Citation2011) identify four alternative approaches to exploring distributed leadership, each embracing different ontological views and leadership epistemologies, as illustrated in below. These four approaches that are 1) relational-entity; 2) relational-structural; 3) relational-processual; and 4) relational-systemic are defined by the nature of leadership; the nature of relationship; the role of context; and the research methods to study leadership. (For more details, refer to Fitzsimons, James, and Denyer Citation2011, 320, ). According to Fitzsimons, James, and Denyer (Citation2011),

Exploring the fine-grained dynamics of relationships within teams will produce very different research agendas, depending on whether the leadership is theorized as something held by entity, a pattern of nodes embedded in a system of relations, a process, or as a self-in-relation (Citation2011, 325),

Figure 6. Dimensions of distributed leadership (adapted from Feng et al. Citation2017, 288).

Research topics and methodological matters: distributed leadership according to qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research

An overview of methodological ‘development’ in the distributed leadership field in the last decade

The search process that eventually narrowed down my distributed leadership ‘canon’ to 128 literature sources according to inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the previous section, yielded 86 empirical publications constituting 67.2% of the whole. The majority were qualitative studies (n = 47, at 54.7%), closely followed by those applying a quantitative approach (n = 29, at 33.7%), while only 11.6% utilised mixed methods (n = 10). This empirical research was conducted in 28 countries representing 5 continents, besides secondary data from the 32 countries participating in the TALIS 2013 survey being utilised in some of the quantitative studies (n = 9). In contrast to Tian et al.’s (Citation2015) findings that represented research conducted in the Anglo-American world, my search revealed distributed leadership research spreading over a broader geographical and cultural spectrum since 2013, with the majority of the empirical research taking place in Central and Western Europe, followed by North America, and closely by Asia, with the rest situated in Australia and Africa (in descending order).

On a similar note to the research quantity and geographical distribution, the scale and methodology have also evolved comparatively over the last decade, following a similar trend in educational leadership research identified by McGinity, Heffernan, and Courtney (Citation2022). Ethnographic case studies emerged at the forefront of qualitative studies, with the most common data collection tools being semi-structured interviews, focus groups, observations, and the still infrequent use of policy analysis, that indicates distributed leadership research moving outwards from its sole focus on school leaders and teachers in schools to embrace the external factors that necessitate the unfolding of distributed leadership to explore whether and how it unfolds in practice. The small number of publications published between 2010 and 2022 utilising a mixed methods approach used a combination of questionnaires and interviews, sometimes accompanied by sociometric analysis data; Q-sort methodology; multi-rater and formative feedback; and explanatory sequential design. The quantitative studies also demonstrated a development in terms of methodological scope via the adoption of t-tests; Likert-scale surveys; exploratory factor analysis; hierarchical linear modelling; and structural equation modelling.

Empirical research carried out over the last decade has managed to partly fill the gap in the application of distributed leadership initially identified by Bennett et al.’s (Citation2003) review, and tackled by Tian et al.’s (Citation2015) subsequent review from 2002 to 2013, but the three approaches identified in the latter meta-analysis and revolving around the conditions conducive to distributed leadership; the effects of distributed leadership practice; and potential risks of distributed leadership applications, have since developed, expanded and evolved in diverse and interesting ways in both the qualitative and quantitative studies.

Distributed leadership research and qualitative methodology: distribution responsibilities; effects on organisational commitment; contribution to policy reform; and overlapping issues

The empirical publications adopting a qualitative methodology focus around four main issues: 1) the distribution of leadership responsibilities; 2) the effects of distributed leadership on organisational commitment; 3) the contribution of distributed leadership to policy reform; and 4) the exploration of distributed leadership in relation to overlapping issues.

Bush and Glover (Citation2012) explore high-performing Senior Leadership Teams as a manifestation of distributed leadership. These are characterised by internal coherence and unity, a focus on high standards, two-way communication with internal and external stakeholders, coupled with a commitment to distributed leadership. Other studies focusing on the distribution of leadership roles and responsibilities among different stakeholders reveal how these non-hierarchical arrangements build on team members’ expertise enabling strong communities of practice that can bring about educational innovations (Bouwmans et al. Citation2019; Clarkin-Phillips Citation2011). Literature also presents us with views of the principals themselves about the development, emergence, and implementation of distributed leadership in their school (Larsen and Rieckhoff Citation2014; Arar and Taysum Citation2020) with leaders’ beliefs about distributed leadership categorised in five dimensions: ‘understandings’, ‘what’, ‘how’, ‘why’, and ‘to whom’ (Tam Citation2019).

Distributed leadership is regarded as a means of bolstering organisational commitment (Hulpia and Devos Citation2010; Melville, Jones, and Campbell Citation2014) with a specific focus on teachers (Youngs Citation2014), leading to the organisational outcomes of efficacy, increased trust, job satisfaction, and teacher retention (Angelle Citation2010). Teachers are situated at the core of distributed leadership (Holloway, Nielsen, and Saltmarsh Citation2018; Lárusdóttir and O’Connor Citation2017).

Is distributed leadership aptly catered for in the policy framework? Abrahamsen and Aas (Citation2016) analyse how Norwegian policy documents translate international discourses and re-contextualize national constructs of school leadership by identifying discursive shifts in ideas about school leadership roles and practices. More recently, Plessis and Heystek (Citation2020) identify policy ambiguities and blind spots in the South African regulatory and policy framework in relation to distributed leadership, arguing that due to its accountability demands and bureaucratic structure, the education system does not permit the practice of heterarchical distributed leadership among the public-school principals. Similar findings are reported on the relationship between leadership theory and policy reform in Malaysia where leadership enactment is entrenched in cultural norms rather than policy prescriptions (Bush and Ng Citation2019). Empirical research presents us with similar evidence in the Middle East. Hashem (Citation2022) argues how the ‘Al faza’a’ hegemonic leadership practices may present an implicit cultural barrier to distributed leadership in Jordanian public schools in the implementation of the education reform for knowledge economy programme.

Leadership distribution makes a vital contribution to education reform (Patterson et al. Citation2021; Malin and Hackmann Citation2017; Amels et al. Citation2021; Ho et al. Citation2022). Notwithstanding, teachers and teacher leaders do face obstacles in their attempts at reform implementation for student success that revolve around dealing with conflict; negotiating competing responsibilities; as well as frustration with lack of influence and impact (McKenzie and Locke Citation2014). Empirical studies explore the relation of democracy to distributed leadership (Mifsud Citation2017a; Woods and Woods Citation2013), as well as incorporating power relations (Mifsud Citation2017b). Other studies investigate distributed leadership and its connection with social justice and democratic values (Woods and Roberts Citation2016).

Distributed leadership research and quantitative methodology: distributed leadership in relation to school improvement; teachers’ job satisfaction; and school climate

On the other hand, the quantitative empirical research that mostly revolves around dimensionality issues in its attempt to build a theoretical (measurement) model of distributed leadership (Hairon and Goh Citation2015), focus around three main factors that are: 1) the relationship between distributed leadership and school improvement/student performance; 2) distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction; and 3) distributed leadership and school climate.

Studies that attempt to explore the relationship between distributed leadership and school improvement do so via the juxtaposition of various variables revolving around the school principal and the teachers. Research seeks to determine the presence or otherwise between distributed leadership and teacher affective commitment (Ross, Lutfi, and Hope Citation2016); teachers’ perceptions of the levels of distributed leadership practices and the indicators of school effectiveness (Al-Harthi and Al-Mahdy Citation2017); as well as the nexus between distributed leadership, teacher academic optimism and teacher organisational commitment (Thien, Adams, and Koh Citation2021; Thien and Chan Citation2022). Another variable often explored along with teachers’ academic optimism is student achievement (Chang Citation2011; Malloy and Leithwood Citation2017). Other studies explore the contribution of distributed leadership to school improvement capacity and student performance (Heck and Hallinger Citation2010; Dampson, Havor, and Laryea Citation2018; Liu Citation2021).

School improvement is dependent on teachers’ motivation and commitment that is directly correlated to student achievement, hence the rationale behind a mapping of teachers’ perceptions of distributed leadership in order to yield inter-correlations between distributed leadership and identified components (Wan, Law, and Chan Citation2018; Tashi Citation2015; Özdemir and Demircioğlu Citation2015). Other variables under scrutiny include the relationship between distributed leadership, professional collaboration, teachers’ job satisfaction, and self-efficacy (Torres Citation2018, Citation2019; Liu, Bellibaş, and Gümüş Citation2021; Sun and Xia Citation2018; Bektaş, Kılınç, and Gümüş Citation2020; Liu and Werblow Citation2019) mostly using data from the TALIS 2013 survey.

School climate is another factor that plays a major part in teachers’ job satisfaction and hence school improvement and student achievement, while very much depending on the level of distributed leadership practices present. Bellibas and Liu (Citation2018) investigate the extent to which leadership styles predict school climate. Bellibaş, Gümüş, and Liu (Citation2021) further examine the influence of principal leadership on teaching practices to reveal the in/direct effects of distributed leadership models on teachers’ instructional quality. Inspired by the theoretical framework of distributed leadership as a dynamic process with the reciprocal interaction of the leader, the subordinate and the situation, Liu, Bellibas, and Printy (Citation2018) explore the reciprocal effects of school contextual variables, and staff characteristics, and influences on the extent of leadership distribution.

This systematic review on distributed leadership research demonstrates a widening of the field both in terms of issues under investigation at compulsory school level, conceptual models applied, as well as geographical spread and culture variation. Notwithstanding the inherently similar broad foci underpinning distributed leadership empirical research, one detects clear distinctions between qualitative and quantitative studies. While qualitative studies divulge their attention to actual enactment and implementation issues revolving around leadership distribution responsibilities, bolstering organisational commitment, contributing to policy reform, and seeking interlapping with related issues, quantitative research seeks to determine a relationship between distributed leadership and the variables of school improvement, teachers’ job satisfaction, and school climate, broadly speaking.

Discussion, recommendations, and conclusions

In this concluding section, some general insights about literature on distributed leadership published between 2010 and 2022 are provided around study type and purpose, research topics and conceptual models, methodological approaches and data collection tools, targeted focus group and context, as well as geographical distribution. My broad search revealed the increase in studies done about distributed leadership in the last decade, which is well aligned with and moves forward from the content of previous review studies that specifically focused on distributed leadership research (Bennett et al. Citation2003; Tian, Risku, and Collin Citation2015; Gumus et al. Citation2018). This is also evidenced by the number of sources that I ended up with for my ‘canon’ after so narrowly applying my inclusion and exclusion criteria following my dual electronic/manual search.

Empirical research around distributed leadership has been carried out in 28 countries spanning five continents with Europe taking the lead. 32.8% of the publications were theoretical/conceptual which was another development on previous reviews. The most favoured methodological approach in the empirical papers (constituting 67.2% of the total) was qualitative (54.7%), followed by quantitative (33.7%), the latter also showing an increase, especially in the use of high-level statistical analysis, with only very few mixed methods studies (11.6%). The context was distributed equally among primary and secondary schooling, with the most popular focus group being the principals. It is also interesting to note the distributed leadership themes that were covered in the publications following a narrative synthesis of the 128 literature sources. The main topics discussed in the theoretical papers are: the rationale behind the dominance of distributed leadership theory; problematising distributed leadership and its implementation in schools; mapping distributed leadership approaches; and the application of a social theory lens for distributed leadership. These topical foci were somewhat mirrored in the empirical papers in distinct and not-so-distinct ways. This systematic literature review has thus identified the expansion and evolution of distributed leadership research in the twelve-year span under study, attesting to the fact that distributed leadership is not a fading concept, but what I consider to be an ‘always-in-the-limelight’, progressive and maturing notion. The topical foci make a valid and timely contribution to the theoretical field of school leadership more specifically and to the educational leadership narrative more widely, while simultaneously making the case for the recommendation of future studies in this specific field.

Notwithstanding the rapid development of distributed leadership scholarship since the last decade as ‘the normatively preferred leadership model in the twenty-first century’ (Bush Citation2013, 543), there are still blank spots that can be filled, as indicated by the findings of this systematic literature review. Despite the increase in the number of theoretical/conceptual papers, more scepticism, critique, and problematization of the actual distributed leadership concept both in theory and practice are needed. Additionally, authorship within this very specific field who ‘trouble’ the distributed leadership concept remains limited to a very small pool of critically-minded academics – these can nurture a wider community for a change in mindset from the normative/descriptive/functional to the critical/theoretical. Interpretation of distributed leadership empirical studies through a social theory lens remains very limited, with the present review identifying only a very small number which stand out as insignificant in relation to the rest (Mifsud Citation2017a; Ho, Chen, and Ng Citation2016). This demonstrates that the important relationship between theory and practice is still sorely lacking in leadership studies (Mifsud Citation2021), which would allow possibilities for the generation of novel perspectives on the leadership phenomenon (Gunter Citation2010). The use of theory was simply an add-on, an afterthought rather, akin to ‘intellectual hairspray’ (McGinity, Heffernan, and Courtney Citation2022, 225) rather than applied to the distributed leadership findings and analysis. Despite some advance in the area, the under-theorisation of identity and power issues within distributed leadership, as identified by Crawford (Citation2012), is still very much present. This is also reiterated by Diamond and Spillane (Citation2016) who suggest studying the implications of status asymmetries in leadership practice. This calls for an exploration of how the characteristics of those who are interacting (e.g. race, class, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) shapes interaction in a distributed leadership perspective. Another related under-theorised area to explore in school settings would be the power flows among the various hierarchical levels within distributed leadership settings. In terms of methodological design, more methodological innovation can be employed via the application of mixed methods research, and also by moving away from the sole focus of interview and focus groups as the main data collection tools for empirical qualitative research. Engagement with more creative methods utilising more unconventional media would provide novel avenues for research into the practice and phenomenon of distributed leadership.

This systematic review has also identified a gap with regards to a disaggregation in geographical distribution in the conduct of empirical studies in distributed leadership and their eventual publication in English language journals. There is a notable absence of studies from South America, while very few studies have been carried out in Australia and Africa. This analysis thus reveals gaps of where we are missing explorations of distributed leadership in different cultural contexts, a fruitful area for expanding future research into the relationship between distributed leadership and culture/context. This will prove beneficial to policymakers in addressing the gap identified and partially tackled by Printy and Liu (Citation2021) of utilising educational policy profiles to explore distributed leadership perceptions and eventual enactments from a global perspective. The cultural context, coupled with country-specific policy initiatives or educational movements would help to move the sole focus from the West and shed light on the impact of policy in relation to the extent of and operation of distributed leadership in discrete contexts within the global education policyscape. This review is thus expected to inform policymakers about shared challenges in practice of the implementation of distributed leadership in schools. Further studies addressing the above-mentioned caveats could possibly provide novel insights into the much-contested notion of distributed leadership in compulsory schooling.

This review study makes an important contribution to educational theory, policy, and practice in the field of distributed leadership in compulsory schooling for publications between 2010 and 2022. However, the study has some limitations, as all review studies do. While this review analysed a substantial database of 128 (academic) publications, it did not include theses or conference proceedings, nor did it cover grey literature. Moreover, due to the very specific nature of the systematic review, only literature targeting distributed leadership in compulsory schooling contexts (as described earlier) was analysed. There is a substantial body of literature exploring distributed leadership in higher education settings which would make for a future systematic review of this leadership discourse/theory at universities. This development challenges Bolden’s (Citation2011) claim of distributed leadership research being restricted solely to the field of school education. My approach relies on titles containing the key words, so those relevant publications omitting the term ‘distributed leadership’ from the title were not returned. Besides a very painstakingly thorough advanced search on the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases, I repeated a similarly exhaustive manual investigation as previously outlined in the methodology section, for all the works published between 2010 and 2022. I am aware, however, that even the most meticulous review may sometimes fail to cover the entire scope of studies on the most specific of topics. Additionally, while I spent significant time and effort to minimise slip-ups such as missing information or incorrect categorisation during the research process, there could still potentially be some minor mistakes given the high volume of publications used in the analysis. Finally, it might be argued that some over-generalizations were made during the content analysis of the documents, at the stage of identifying the distributed leadership topics covered in the theoretical, qualitative, and quantitative publications, however, the author attempted to counteract this by citing specific examples. Another point I would like to make deals with the disaggregation of distributed leadership empirical research in geographical distribution. While the author identified a blank spot in terms of the presence and/or absence of studies in terms of cultural context, one must bear in mind that this systematic review targeted publications in English language journals only. Including foreign language publications (that goes beyond the qualitative interpretive scope of this literature review) may reveal different patterns in terms of global geographical distribution.

To conclude, this systematic literature review with a specific qualitative focus on distributed leadership publications from 2010 to 2022 is significant in terms of the provision of novel insights into distributed leadership scholarship that make a positive contribution to leadership theory, policy, and practice. I consider this present analysis as a response to Gunter et al.’s (Citation2013, 573) invitation for ‘scholarly analysis of the literatures about distributed leadership … [that] requires a thorough read and analysis and engagement with the literature as literatures’. And that is how and why this systematic literature review sets out to explore the burgeoning discourses of distributed leadership that have unfurled between 2010 and 2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Denise Mifsud

Dr. Denise Mifsud is Associate Professor in Educational Leadership, Management and Governance in the Department of Education at the University of Bath. She has many years of practitioner experience in education settings in both teaching and top-level leadership roles within the Ministry for Education, Malta. She previously held a full-time lecturing post at the University of the West of Scotland as well as being a part-time lecturer at the University of Malta. She is also an Associate Fellow of the Euro-Mediterranean Centre for Educational Research within the same university. She was awarded her PhD by the University of Stirling in 2015. Research areas of interest include educational policy analysis, generation, reception and enactment; critical leadership theories, with a particular interest in educational leadership, especially distributed forms; school networks and educational reform; teacher education; teacher leadership; power relations; Foucauldian theory; Actor-Network theory, as well as qualitative research methods, with a particular focus on narrative, as well as creative and unconventional modes of data representation. She is a member of several professional organizations, in addition to being an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. She is an elected member of the BELMAS Council, as well as co-convenor of the Critical Educational Leadership & Policy Studies BELMAS RIG, and also co-convenor of the Social Theory and Education BERA SIG. She has published in several international top-rated journals, in addition to monographs and edited volumes. She has won awards by the AERA, EERA and SERA for her publications.

Notes

1 This article search was conducted in January-February 2022, hence other studies published after this date have not been included. Due to the submission, peer review and publication process and the timeline involved, subsequent relevant contributions may therefore have been excluded due to reasons beyond the author’s control.

References

- *Abrahamsen, H., and M. Aas. 2016. “School Leadership for the Future: Heroic or Distributed? Translating International Discourses in Norwegian Policy Documents.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 48 (1): 68–88. doi:10.1080/00220620.2016.1092426

- *Al-Harthi, A. S. A., and Y. F. H. Al-Mahdy. 2017. “Distributed Leadership and School Effectiveness in Egypt and Oman: An Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Educational Management 31 (6): 801–813.

- Alvesson, M., and A. Spicer, eds. 2011. Metaphors we Lead by: Understanding Leadership in the Real World. London, UK: Routledge.

- *Amels, J., M. L. Krüger, C. J. Suhre, and K. van Veen. 2021. “The Relationship Between Primary School Leaders’ Utilization of Distributed Leadership and Teachers’ Capacity to Change.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 49 (5): 732–749. doi:10.1177/1741143220915921

- *Angelle, P. S. 2010. “An Organizational Perspective of Distributed Leadership: A Portrait of a Middle School.” RMLE Online 33 (5): 1–16. doi:10.1080/19404476.2010.11462068

- *Arar, K., and A. Taysum. 2020. “From Hierarchical Leadership to a Mark of Distributed Leadership by Whole School Inquiry in Partnership with Higher Education Institutions: Comparing the Arab Education in Israel with the Education System in England.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 23 (6): 755–774. doi:10.1080/13603124.2019.1591513

- *Bektaş, F., AÇ Kılınç, and S. Gümüş. 2020. “The Effects of Distributed Leadership on Teacher Professional Learning: Mediating Roles of Teacher Trust in Principal and Teacher Motivation.” Educational Studies 48 (5): 602–624.

- Bellibas, M. S., and S. Gumus. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Educational Leadership and Management Research in Turkey: Content Analysis of Topics, Conceptual Models, and Methods.” Journal of Educational Administration 57 (6): 731–747. doi:10.1108/JEA-01-2019-0004

- *Bellibaş, MŞ, S. Gümüş, and Y. Liu. 2021. “Does School Leadership Matter for Teachers’ Classroom Practice? The Influence of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Instructional Quality.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 32 (3): 387–412. doi:10.1080/09243453.2020.1858119

- *Bellibas, M. S., and Y. Liu. 2018. “The Effects of Principals’ Perceived Instructional and Distributed Leadership Practices on Their Perceptions of School Climate.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 21 (2): 226–244. doi:10.1080/13603124.2016.1147608

- Bennett, N., C. Wise, P. A. Woods, and J. Harvey. 2003. Distributed Leadership: A Case Study. Nottingham, UK: National College for School Leadership.

- *Bolden, R. 2011. “Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Research.” International Journal of Management Reviews 13 (3): 251–269. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x

- Booth, A., D. Papaioannou, and A. Sutton. 2012. Systematic Approaches to Successful Literature Review. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- *Bouwmans, M., P. Runhaar, R. Wesselink, and M. Mulder. 2019. “Towards Distributed Leadership in Vocational Education and Training Schools: The Interplay Between Formal Leaders and Team Members.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (4): 555–571. doi:10.1177/1741143217745877

- Burrell, G., and G. Morgan. 1979. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- *Bush, T. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: The Model of Choice in the Twenty-First Century.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 41 (5): 543–544. doi:10.1177/1741143213489497

- *Bush, T., and D. Glover. 2012. “Distributed Leadership in Action: Leading High-Performing Leadership Teams in English Schools.” School Leadership & Management 32 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1080/13632434.2011.642354

- *Bush, T., and A. Y. M. Ng. 2019. “Distributed Leadership and the Malaysia Education Blueprint: From Prescription to Partial School-Based Enactment in a Highly Centralised Context.” Journal of Educational Administration 57 (3): 279–295. doi:10.1108/JEA-11-2018-0206

- *Chang, I. H. 2011. “A Study of the Relationships Between Distributed Leadership, Teacher Academic Optimism and Student Achievement in Taiwanese Elementary Schools.” School Leadership & Management 31 (5): 491–515. doi:10.1080/13632434.2011.614945

- *Clarkin-Phillips, J. 2011. “Distributed Leadership: Growing Strong Communities of Practice in Early Childhood Centres.” Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice 26 (2): 14–25.

- *Corrigan, J. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: Rhetoric or Reality?” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 35 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2013.748479

- *Crawford, M. 2012. “Solo and Distributed Leadership: Definitions and Dilemmas.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 40 (5): 610–620. doi:10.1177/1741143212451175

- *Dampson, D. G., F. M. Havor, and P. Laryea. 2018. “Distributed Leadership an Instrument for School Improvement: The Study of Public Senior High Schools in Ghana.” Journal of Education and e-Learning Research 5 (2): 79–85. doi:10.20448/journal.509.2018.52.79.85

- Diamond, J. B., and J. P. Spillane. 2016. “School Leadership and Management from a Distributed Perspective: A 201 Retrospective and Prospective.” Management in Education 30 (4): 147–154. doi:10.1177/0892020616665938

- *Feng, Y., B. Hao, P. Iles, and N. Bown. 2017. “Rethinking Distributed Leadership: Dimensions, Antecedents and Team Effectiveness.” Leadership & Organization Development Journal 38 (2): 284–302. doi:10.1108/LODJ-07-2015-0147

- *Fitzsimons, D., K. T. James, and D. Denyer. 2011. “Alternative Approaches for Studying Shared and Distributed Leadership.” International Journal of Management Reviews 13 (3): 313–328. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00312.x

- Fullan, M. 2005. Leadership and Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Gillies, D. 2013. Educational Leadership and Michel Foucault. London, UK: Routledge.

- Gronn, P. 2002. ““Distributed Leadership”.” In Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration, Part two, edited by K. Leithwood, and P. Hallinger, 613–696. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Gronn, P. 2016. “Fit for Purpose no More?” Management in Education 30 (4): 168–172. doi:10.1177/0892020616665062

- Gumus, S., M. S. Bellibas, M. Esen, and E. Gumus. 2018. “A Systematic Review of Studies on Leadership Models in Educational Research from 1980 to 2014.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 46 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1177/1741143216659296

- Gunter, H. M. 2010. “A Sociological Approach to Educational Leadership.” British Journal of the Sociology of Education 31 (4): 519–527. doi:10.1080/01425692.2010.484927

- *Gunter, H. M., D. Hall, and J. Bragg. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: A Study in Knowledge Production.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 41 (5): 555–580. doi:10.1177/1741143213488586

- *Hairon, S., and J. W. Goh. 2015. “Pursuing the Elusive Construct of Distributed Leadership: Is the Search Over?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 43 (5): 693–718. doi:10.1177/1741143214535745

- *Hairon, S., J. W. P. Goh, and T. B. Lin. 2014. “Distributed Leadership to Support PLCs in Asian Pragmatic Singapore Schools.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 17 (3): 370–386. doi:10.1080/13603124.2013.829586

- Hall, D. 2013. “The Strange Case of the Emergence of Distributed Leadership in Schools in England.” Educational Review 65: 467–487. doi:10.1080/00131911.2012.718257

- Hallinger, P. 2013. “A Conceptual Framework for Systematic Reviews of Research in Educational Leadership and Management.” Journal of Educational Administration 51 (2): 126–149. doi:10.1108/09578231311304670

- Hallinger, P., and J. Chen. 2015. “Review of Research on Educational Leadership and Management in Asia: A Comparative Analysis of Research Topics and Methods, 1995–2012.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 43 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1177/1741143214535744

- Hallinger, P., and J. Kovacevic. 2021. “Science Mapping the Knowledge Base in Educational Leadership and Management: A Longitudinal Bibliometric Analysis, 1960–2018.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 49 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1177/1741143219859002

- Harris, A. 2005. Crossing Boundaries and Breaking Barriers: Distributing Leadership in Schools. London: Specialist Schools Trust.

- *Harris, A. 2012. “Distributed Leadership: Implications for the Role of the Principal.” Journal of Management Development 31 (1): 7–17. doi:10.1108/02621711211190961

- Harris, A. 2013a. “Distributed Leadership: Friend or foe?” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 41 (5): 545–554. doi:10.1177/1741143213497635

- *Harris, A. 2013b. Distributed Leadership Matters: Perspectives, Practicalities, and Potential. USA: Corwin Press.

- Harris, A., and J. DeFlaminis. 2016. “Distributed Leadership in Practice: Evidence, Misconceptions and Possibilities.” Management in Education 30 (4): 141–146. doi:10.1177/0892020616656734

- Harris, A., and L. Lambert. 2003. Building Leadership Capacity for School Improvement. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- *Hartley, D. 2010a. “Paradigms: How far Does Research in Distributed Leadership ‘Stretch’?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 38 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1177/1741143209359716

- *Hartley, D. 2010b. “The Management of Education and the Social Theory of the Firm: From Distributed Leadership to Collaborative Community.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 42 (4): 345–361. doi:10.1080/00220620.2010.492958

- *Hashem, R. 2022. “‘Al Faza’a’leadership: An Implicit Cultural Barrier to Distributed Leadership in Jordanian Public Schools.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 50 (1): 26–42. doi:10.1177/1741143220932580

- *Heck, R. H., and P. Hallinger. 2010. “Testing a Longitudinal Model of Distributed Leadership Effects on School Improvement.” The Leadership Quarterly 21 (5): 867–885. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.07.013

- *Ho, J. P. Y., V. D. T. Chen, and D. Ng. 2016. “Distributed Leadership Through the Lens of Activity Theory.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44 (5): 814–836. doi:10.1177/1741143215570302

- *Ho, J., D. Hung, P. H. Chua, and N. Binte Munir. 2022. “Integrating Distributed with Ecological Leadership: Through the Lens of Activity Theory.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 17411432221077156.

- *Holloway, J., A. Nielsen, and S. Saltmarsh. 2018. “Prescribed Distributed Leadership in the era of Accountability: The Experiences of Mentor Teachers.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46 (4): 538–555. doi:10.1177/1741143216688469

- *Hulpia, H., and G. Devos. 2010. “How Distributed Leadership Can Make a Difference in Teachers’ Organizational Commitment? A Qualitative Study.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 565–575. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.08.006

- *Jambo, D., and L. Hongde. 2020. “The Effect of Principal's Distributed Leadership Practice on Students’ Academic Achievement: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Higher Education 9 (1): 189–198.

- *Jarvis, A. 2021. “Untangling Collegiality and Distributed Leadership: Equality Versus Utility. A Perspective Piece.” Management in Education. 08920206211057980.

- *Larsen, C., and B. S. Rieckhoff. 2014. “Distributed Leadership: Principals Describe Shared Roles in a PDS.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 17 (3): 304–326. doi:10.1080/13603124.2013.774051

- *Lárusdóttir, S. H., and E. O’Connor. 2017. “Distributed Leadership and Middle Leadership Practice in Schools: A Disconnect?” Irish Educational Studies 36 (4): 423–438. doi:10.1080/03323315.2017.1333444

- Liu, Y. 2020. “Focusing on the Practice of Distributed Leadership: The International Evidence from the 2013 TALIS.” Educational Administration Quarterly 56 (5): 779–818. doi:10.1177/0013161X20907128

- *Liu, Y. 2021. “Distributed Leadership Practices and Student Science Performance Through the Four-Path Model: Examining Failure in Underprivileged Schools.” Journal of Educational Administration 59 (4): 472–492. doi:10.1108/JEA-07-2020-0159

- *Liu, Y., MŞ Bellibaş, and S. Gümüş. 2021. “The Effect of Instructional Leadership and Distributed Leadership on Teacher Self-Efficacy and job Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Supportive School Culture and Teacher Collaboration.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 49 (3): 430–453. doi:10.1177/1741143220910438

- *Liu, Y., M. S. Bellibas, and S. Printy. 2018. “How School Context and Educator Characteristics Predict Distributed Leadership: A Hierarchical Structural Equation Model with 2013 TALIS Data.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46 (3): 401–423. doi:10.1177/1741143216665839

- *Liu, Y., and J. Werblow. 2019. “The Operation of Distributed Leadership and the Relationship with Organizational Commitment and job Satisfaction of Principals and Teachers: A Multi-Level Model and Meta-Analysis Using the 2013 TALIS Data.” International Journal of Educational Research 96: 41–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2019.05.005

- *Lumby, J. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: The Uses and Abuses of Power.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 41 (5): 581–597. doi:10.1177/1741143213489288

- *Lumby, J. 2016. “Distributed Leadership as Fashion or fad.” Management in Education 30 (4): 161–167. doi:10.1177/0892020616665065

- *Lumby, J. 2019. “Distributed Leadership and Bureaucracy.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 47 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1177/1741143217711190

- *Malin, J. R., and D. G. Hackmann. 2017. “Enhancing Students’ Transitions to College and Careers: A Case Study of Distributed Leadership Practice in Supporting a High School Career Academy Model.” Leadership and Policy in Schools 16 (1): 54–79. doi:10.1080/15700763.2016.1181191

- *Malloy, J., K. Leithwood, et al. 2017. “Effects of Distributed Leadership on School Academic Press and Student Achievement.” In How School Leaders Contribute to Student Success, edited by K. Leithwood, J. Sun, and K. Pollock, Vol. 23, 69–91. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50980-8_5

- Mayrowetz, D. 2008. “Making Sense of Distributed Leadership: Exploring the Multiple Usages of the Concept in the Field.” Educational Administration Quarterly 44 (3): 424–435. doi:10.1177/0013161X07309480

- McGinity, R., A. Heffernan, and S. J. Courtney. 2022. “Mapping Trends in Educational Leadership Research: A Longitudinal Examination of Knowledge Production, Approaches and Locations.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 50 (2): 217–232. doi:10.1177/17411432211030758

- *McKenzie, K. B., and L. A. Locke. 2014. “Distributed Leadership: A Good Theory but What if Leaders Won't, Don't Know How, or Can't Lead?” Journal of School Leadership 24 (1): 164–188. doi:10.1177/105268461402400106

- *Melville, W., D. Jones, and T. Campbell. 2014. “Distributed Leadership with the aim of ‘Reculturing’: A Departmental Case Study.” School Leadership & Management 34 (3): 237–254. doi:10.1080/13632434.2013.849681

- *Mifsud, D. 2017a. “Distribution Dilemmas: Exploring the Presence of a Tension Between Democracy and Autocracy Within a Distributed Leadership Scenario.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 45 (6): 978–1001. doi:10.1177/1741143216653974

- *Mifsud, D. 2017b. “Distributed Leadership in a Maltese College: The Voices of Those among Whom Leadership Is ‘Distributed’ and Who Concurrently Narrate Themselves as Leadership ‘Distributors’.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 20 (2): 149–175. doi:10.1080/13603124.2015.1018335

- Mifsud, D. 2017c. Foucault and School Leadership Research: Bridging Theory and Method. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- *Mifsud, D. 2021. “Foucault’s Governmentality and Educational Leadership Discourses: Unmasking the Politics Underlying the Apparent Neutrality of Distributed Leadership.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse, edited by F. English, 1–26. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oplatka, I., and K. Arar. 2017. “The Research on Educational Leadership and Management in the Arab World Since the 1990s: A Systematic Review.” Review of Education 5 (3): 267–307. doi:10.1002/rev3.3095

- *Özdemir, M., and E. Demircioğlu. 2015. “Distributed Leadership and Contract Relations: Evidence from Turkish High Schools.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 43 (6): 918–938. doi:10.1177/1741143214543207

- *Patterson, J. A., H. AlSabatin, A. Anderson, M. Klepacka, J. Lawrence, and B. Miner. 2021. “A Distributed Leadership Perspective on Implementing Instructional Reform: A Case Study of an Urban Middle School.” Journal of School Leadership 31 (3): 248–267. doi:10.1177/1052684620904942

- *Plessis, A., and J. Heystek. 2020. “Possibilities for Distributed Leadership in South African Schools: Policy Ambiguities and Blind Spots.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 48 (5): 840–860. doi:10.1177/1741143219846907

- Printy, S., and Y. Liu. 2021. “Distributed Leadership Globally: The Interactive Nature of Principal and Teacher Leadership in 32 Countries.” Educational Administration Quarterly 57 (2): 290–325. doi:10.1177/0013161X20926548

- *Ross, L., G. A. Lutfi, and W. C. Hope. 2016. “Distributed Leadership and Teachers’ Affective Commitment.” NASSP Bulletin 100 (3): 159–169. doi:10.1177/0192636516681842

- *Salahuddin, A. N. M. 2010. “Distributed Leadership in Secondary Schools: Possibilities and Impediments in Bangladesh.” Arts Faculty Journal 4: 19–32.

- Spillane, J. P. 2005. “Distributed Leadership.” The Educational Forum 69 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1080/00131720508984678

- Storey, A. 2004. “The Problem of Distributed Leadership in Schools.” School Leadership & Management: Formerly School Organisation 24 (3): 249–226. doi:10.1080/1363243042000266918