Abstract

Given the consensus on the importance of teacher reflection and the paucity of research on affective motivational challenges and outcomes of in-service teacher reflection, this study examined the hypothesis that support of in-service teachers’ basic psychological needs (for relatedness, competence, and autonomy) in collaborative reflection settings would predict increased reflectivity, which, in turn, would predict increased autonomous motivation for and sense of accomplishment in teaching. Employing self-determination theory, we analyzed beginning- and end-of-year data from 92 Israeli in-service teachers participating in a programme designed to promote collaborative reflective inquiry. The results confirmed our hypothesis, suggesting facilitators’ support for teachers’ psychological needs may foster teacher reflection and, consequently, their motivation for teaching, with implications for teachers’ well-being, and the quality of their professional learning and their teaching. The findings provide evidence that psychological challenges in promoting in-service teachers’ reflection can be overcome and offer a theoretical framework for designs that contend with these challenges. This study adds to research on reflection by suggesting reflection may improve teaching by bolstering teachers’ motivation. It adds to teacher motivation research by suggesting teacher motivation is malleable, even for veteran teachers, and may be fostered through properly designed PD.

Introduction

The concept of teacher reflection has become a central theme in teacher professional learning (Brookfield, Citation2017; Fendler, Citation2003; Hatton & Smith, Citation1995). Yet promoting teacher reflection is challenging, in both pre-service (e.g., Husu et al., Citation2008; Mulryan-Kyne, Citation2020; Svojanovsky, Citation2017) and in-service (e.g., Horn & Garner, Citation2022; Korthagen, Citation2016; Marcos et al., Citation2009) teacher education. In recent decades, accumulating evidence suggests discussions of problems-of-practice in teacher communities can trigger and support in-service teacher collaborative reflection (Horn & Little, Citation2010; Zhang et al., Citation2011). At the same time, this research argues that professional norms, including individualism, privacy, presentism, and normalization, undermine collaborative reflection (Hargreaves & Shirley, Citation2009; Horn & Little, Citation2010; Little, Citation1990). Yet this research seldom focuses on the psychological aspects involved in promoting reflection, in particular, meeting motivational psychological needs known to support learning (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). The present study aimed to fill this gap in the literature by looking at psychological conditions that may support in-service teacher individual reflection in collaborative reflection professional development (PD) settings.

It is increasingly acknowledged that the quality of teacher instruction depends not only on cognitive constructs (such as knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions) but also on affective ones (such as emotions, motivation, and wellbeing; Korthagen, Citation2016; Mälkki, Citation2019). A few scholars have suggested that reflection can promote such motivational and emotional outcomes, for example, by protecting from burnout and a sense of helplessness (Labaree, Citation2000; Larrivee, Citation2008). Yet the literature on teacher reflection predominantly considers cognitive and practical outcomes (Korthagen, Citation2016), with little empirical research on the benefits of reflection for in-service teachers’ motivation and wellbeing. Moreover, although research on teacher motivation is growing, empirical evidence of how designed PD processes may promote it remains rare (Daumiller et al., Citation2023; Watt et al., Citation2021).

We suggest that self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017, Citation2020), a macro theory of motivation, may offer a fruitful conceptual framework for exploring antecedents and outcomes of teacher reflection. Based on SDT, we examined the basic psychological needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy in a collaborative reflection PD setting as possible antecedents of teachers’ reflectivity. SDT suggests frustration of these basic needs may impede engagement in learning, reflection, and exploration, whereas their support may enhance engagement in such activities (Reeve et al., Citation2004; Ryan & Deci, Citation2017; Soenens et al., Citation2005). SDT further highlights the reasons or sources for behavior, repeatedly demonstrating the advantages of autonomous motivation for teaching (for a review, see Slemp et al., Citation2020).

To advance understanding of the benefits of reflection and ways to support it, we examined an Israeli in-service PD programme aiming to foster collaborative reflection. We view reflection as a conscious purposeful examination of practice that aims at improvement and includes critically thinking about assumptions, beliefs, goals, choices, and actions (Brookfield, Citation2017; Clarà, Citation2015; Hatton & Smith, Citation1995; Valli, Citation1997). Using SDT, we explored whether perceptions of psychological needs support in a collaborative reflection PD setting predicted increased reflectivity (i.e., the tendency to reflect) and whether this, in turn, predicted teachers’ autonomous motivation and sense of personal accomplishment in teaching. The study contributes to the field of teacher reflection by focusing on in-service teachers and examining hitherto unexplored antecedents and outcomes of reflection. It contributes to the field of teacher motivation by examining whether motivation may be supported by reflection.

Teacher reflection

Benefits of reflection

Teacher reflection is widely endorsed as a hallmark of professional competence (Brookfield, Citation2017; Larrivee, Citation2008). It has become a primary goal in many (if not most) preparation and in-service PD programmes (Anderson, Citation2019; Mulryan-Kyne, Citation2020; Svojanovsky, Citation2017). Whilst there is no agreed-upon definition of teacher reflection (Zeichner & Liston, Citation2013), most scholars draw on Dewey’s (Citation1933) and Schön’s (Citation1983) conceptions. Dewey (Citation1933) highlighted reflective thinking as scientific, rational problem-solving, in which justifications and consequences are systematically considered, rather than taking appetitive, impulsive action. Dewey emphasized a purposeful, reasoned search for a solution that explores underlying beliefs and knowledge and stems from a sense of uncertainty. Such a search includes describing the situation and then questioning initial understandings, with an attitude of open-mindedness, responsibility, and whole-heartedness (Dewey, Citation1933). Schön (Citation1983) expanded Dewey’s work by differentiating intuitive reflection-in-action from the application of scientific principles to practice. Schön emphasized the artistry of practitioners as they face non-routine, complex, ambiguous, practical problems, framing and reframing them, testing their interpretations and solutions, and combining reflection and action. He further argued that due to "overlearning" in routine situations, practitioners may develop tacit understandings or unconscious repetitive practice which they need to problematize.

Following Dewey and Schön, Marc Clarà defined reflection as “a thinking process which gives coherence to a situation which is initially incoherent and unclear” (2015, p. 263), offering it as a descriptive notion that can be further specified. In this study, we adopt Clara’s definition, and like others before us, we further specify it as a conscious purposeful examination of practice that aims at improvement and includes critically thinking about assumptions, beliefs, goals, choices, and actions (e.g., Brookfield, Citation2017; Hatton & Smith, Citation1995; Valli, Citation1997). This definition encompasses teachers trying to make sense of instructional challenges as they reason about different ways to manage them. It excludes, for example, teachers celebrating success or simply “blowing off steam”.

Defined as a thinking process (Clarà, Citation2015), reflection may be viewed primarily as an individual operation, but it may also be seen as a shared, distributed, collaborative process. Such a view is aligned with contemporary learning theories that conceptualize learning and knowing as situated, social, and distributed (Putnam & Borko, Citation2000). It is also aligned with the growing consensus that high-quality PD entails collaborative spaces for teachers to explore their practice together (Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, recent research on teacher reflection focuses less on, for example, individual reflective writing and more on collaborative reflection. In collaborative reflection, teachers examine their practice with colleagues, learning from others’ experiences by comparing and contrasting perspectives, assumptions, considerations, and alternative courses of action. In collaborative reflection, teachers jointly construct new understandings through dialogue (Burhan-Horasanlı & Ortaçtepe, Citation2016; Chong & Kong, Citation2012; Godínez Martínez, Citation2018; Kim & Silver, Citation2016; Sulzer & Dunn, Citation2019).

In addition to cognitive support, collaborative reflection may offer social and emotional support (Korthagen et al., Citation2006). Indeed, a growing body of literature argues for collaborative reflection in teacher communities (for a recent review, see Lefstein, Louie et al., Citation2020). Albeit not always explicitly, this literature integrates Dewey’s and Schön’s concepts of reflection with the concept of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991), viewing teacher collaborative reflection as a process of enculturation into the teaching community of practice (Lefstein, Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, such research commonly focuses on group reflective discussions about problems-of-practice represented by classroom artifacts, such as video-recordings and student work (e.g., Horn & Little, Citation2010; Van Es et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2011). In accordance with the situated learning perspective, this line of research assumes that through the enculturation process, teachers internalize the discourse in which they participate, or in other words, the way they talk becomes the way they think (Horn & Garner, Citation2022; Lefstein, Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2020). Thus, by routinely participating in collaborative reflective discussions with other community members, teachers become more reflective about their practice. In this study, we explored changes in teachers’ individual reflectivity (i.e., their tendency to reflect) within the context of collaborative reflection settings.

Although there is a consensus on the importance of teacher reflection, both individually and collaboratively, hard empirical evidence demonstrating its benefits is relatively scarce, particularly for in-service teachers (Fendler, Citation2003; Vescio et al., Citation2008). Relative to pre-service teachers, in-service teachers have more knowledge and experience on which they can draw for reflective processes (Calderhead, Citation1989), but their professional status might make it harder for them to share problems-of-practice and expose their doubts (Eshchar-Netz et al., Citation2022). Some evidence, however, suggests promoting reflection through on-going collaborative PD can positively impact perceptions and instruction (Hoekstra & Korthagen, Citation2011). Sherin and Van Es (Citation2009), for example, found teachers’ participation in a two-year video club focusing on collaborative reflection developed their ability to notice and attend to students’ mathematical ideas, not just in their video-club meetings but also in their classroom instruction (see also Godínez Martínez, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2011). Further evidence of the benefits of collaborative reflection for in-service teachers is found in studies investigating in-school professional learning communities (Levine & Marcus, Citation2010; Vescio et al., Citation2008). Yet evidence showing participation in collaborative reflection-based PD enhances teachers’ tendency to individually reflect on their teaching practices is lacking.

The literature on reflection suggests teacher reflection may go beyond enhancing professional knowledge and skills. It may also be beneficial for affective dimensions of professional development, possibly protecting veteran teachers from automatization and burnout (Schön, Citation1983) and helping them make sense of the complexity of teaching, thus supporting their sense of efficacy in the classroom (Labaree, Citation2000). It may boost their sense of autonomy and mastery of their teaching by allowing them to focus on problems-of-practice that matter to them (Calderhead, Citation1989; Larrivee, Citation2008). Until now, such affective outcomes for in-service teachers have not been empirically explored. Therefore, we explored whether reflection promotes teaching autonomous motivation and sense of accomplishment.

Challenges in cultivating reflection

Despite the evidence of the benefits of reflection, scholars report significant challenges to enhancing teacher reflection, especially in fostering beyond-surface-level reflection (Fox et al., Citation2019; Godínez Martínez, Citation2018; Kim & Silver, Citation2016; Körkkö et al., Citation2016; Larrivee, Citation2008). In many schools, prevailing norms impede collaborative reflection among in-service teachers. Norms of presentism (Hargreaves & Shirley, Citation2009) prioritize the “urgent” over the “important,” neglecting reflection in favor of surface-level problem-solving, logistic coordination, and “tips and tricks” (Horn et al., Citation2017). Norms of isolation, privacy, and individualism prevent teachers from sharing their practice with colleagues and collaboratively and critically reflecting on them (Horn & Little, Citation2010; Little, Citation1990). When teachers do discuss their practice, they prefer sharing success stories, normalizing problems, framing them in unproductive ways, and avoiding disagreement (Horn & Little, Citation2010; Louie, Citation2016; Segal, Citation2019; Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2018; Citation2019). Moreover, “escalating pressure to be accountable for students reaching imposed standards of performance increases the likelihood of teachers using teaching strategies that prioritize efficiency and expediency, which may come at the expense of ongoing reflection on teaching practices” (Larrivee, Citation2008, p. 341; see also Feniger et al., Citation2023).

Reflection is emotionally and cognitively demanding. Critically scrutinizing practice entails questioning the taken-for-granted, facing difficult questions to which there are not always satisfying answers (Horn & Garner, Citation2022), and contending with uncertainty (Dewey, Citation1933; Spalding et al., Citation2002). Reflection exposes the shortcomings of practice, constraining perceptions and beliefs, mistakes, and bad judgment, all of which can be threatening, even paralyzing (Schön, Citation1983). Sharing these weaknesses with colleagues in collaborative reflection is even more challenging than in individual reflection, increasing vulnerability and posing a threat to teachers’ face (Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2019). This is especially so for veteran teachers and may result in defensive avoidance of reflection (Eshchar-Netz et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). Yet the literature on collaborative reflection in teacher communities usually focuses on the obstacles related to school culture mentioned above and on cognitive dimensions, such as teacher beliefs and perceptions, with little attention to emotional and motivational challenges (Hoekstra & Korthagen, Citation2011; Korthagen, Citation2016). Given the motivational and emotional threats that collaborative reflection may involve for in-service teachers, it is surprising that little research has directly examined psychological aspects that may help manage these threats and thus support constructive collaborative reflection and related individual reflection.

Motivational antecedents and outcomes of teacher reflection

SDT (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000, Citation2017) is one of the most productive educational motivation theories, repeatedly proven to advance understanding of how various educational environments support motivation and engagement for students (Michou et al., Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2020) and teachers (e.g., Korthagen & Evelein, Citation2016; Roth, Citation2014). A recent meta-analysis, based on 98 studies exploring teacher motivation through the SDT framework (Slemp et al., Citation2020), demonstrated SDT’s contribution to teacher research, highlighting ways to support teacher well-being and motivation to teach and improve their teaching.

SDT distinguishes between autonomous and controlled motivations. Controlled motivation refers to performing a behavior with a sense of pressure or compulsion. The behavior may be controlled by external rewards and punishments (e.g., teaching a particular subject to please the principal) or by inner compulsion (e.g., teaching in a way that the teacher is very skilled at, despite its shortcomings, to boost self-esteem or avoid embarrassment). Controlled motivation leads to constricted and shallow functioning and performance (e.g., Collie et al., Citation2019; Grolnick & Ryan, Citation1989). Autonomous motivation refers to acting with a sense of volition and choice, either identifying with the goals of the activity or enjoying it (e.g., teaching a particular subject in a particular way because the teacher perceives it as important, interesting, or enjoyable). Autonomous motivation facilitates a sense of freedom to adopt a more open and flexible stance that leads to more exploratory and responsive modes of behavior (e.g., Michou et al., Citation2021; Roth et al., Citation2007; Soenens et al., Citation2005).

A rich body of research addresses the benefits of autonomous motivation and the shortcomings of controlled motivation, in terms of performance, adjustment, and wellbeing, with effects demonstrated across ages, cultures, contexts, and domains (e.g., Collie et al., Citation2019; Grolnick & Ryan, Citation1989; Slemp et al., Citation2020). Moreover, SDT research has extensively explored conditions promoting or undermining autonomous (versus controlled) motivation (e.g., Michou et al., Citation2021), thus providing a conceptual and empirical foundation to explore antecedents of the capacity and tendency for reflection.

SDT posits autonomous motivation is facilitated by the satisfaction of three primary psychological needs: competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). To be autonomously motivated to perform a task, people need to feel competent—a sense of mastery and ability to succeed. Competence support includes provision of structure (as opposed to chaos), communication of optimally challenging expectations, explanations of consequences, and informational feedback. Relatedness—a sense of belonging with and care by others—is equally essential for autonomous motivation. People act autonomously when they feel socially safe, loved, and appreciated, especially when actions are challenging and involve risk. Lastly, autonomy is high when our behavior corresponds with our values, interests, and preferences. Autonomy support includes affording choice, self-initiative, and participation in decision-making, providing meaningful rationales and relevance, and refraining from controlling language or actions (Collie et al., Citation2019; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

A meta-analysis of 102 independent samples (Slemp et al., Citation2020) demonstrated that teachers’ psychological need satisfaction was negatively associated with distress and positively related with their wellbeing and autonomy supportive teaching. These associations were mediated by autonomous motivation for teaching. For example, Korthagen and Evelein (Citation2016) found the satisfaction of pre-service teachers’ psychological needs in the classroom was associated with positive teaching outcomes, such as leadership behavior and autonomy support for students. Others found need satisfaction predicted the degree to which experienced in-service physical education teachers were autonomously motivated in their teaching (in the USA; Carson & Chase, Citation2009) or tried to understand their students and offer instrumental support (in the UK; Taylor et al., Citation2008). Pelletier et al. (Citation2002) examined experienced in-service teachers in Canada and showed that the more they felt pressured by colleagues, administration, and curriculum (i.e., their need for autonomy was frustrated), the less autonomously motivated they were in their work, and, in turn, the more controlling they were with their students.

Facilitating teacher reflection through basic needs satisfaction

We suggest support for the three basic needs (relatedness, competence, autonomy) may foster collaborative reflection because it may reduce ego-involvement, including fear of criticism, embarrassment, and loss of face. When teachers feel competent, related (which involves protection from ego-threats), and autonomous (engaged in personally valuable or/and interesting PD) they may feel secure enough to question some of their practices, thus allowing them to reflect and learn with and from their peers. Past research has examined the outcomes of supporting teachers’ psychological needs (Slemp et al., Citation2020), but we found only one published study on the relations between needs support and teacher reflection. Using the SDT framework, Dreer (Citation2020) found a significant association between pre-service teachers’ basic needs support during field experiences and levels of individual reflection. Other research on conditions that enhance teacher reflection indirectly suggests that supporting teachers’ psychological needs can enhance their reflection, even though the findings are not conceptualized this way. For example, in two studies, pre-service teachers pointed to the importance of relatedness by indicating strategies supporting their reflection were characterized by interactions with trusted others (Korthagen et al., 2006; Spalding et al., Citation2002). Similarly, analysis of post-lesson reflective discussions demonstrated the importance of autonomy support for reflection by showing that in-service teachers were more likely to reflect on their practice if they were the ones to introduce the topic of discussion and if they themselves identified incoherence as a starting point for the discussion (Kim & Silver, Citation2016). Another example comes from a qualitative longitudinal study that demonstrated reflection was perceived as more effective and meaningful to in-service than pre-service teachers, because of its direct relevance to their on-going practice (Jindal‐Snape & Holmes, Citation2009; see also Attard, Citation2012). Evidence of the role of competence support can be found, for example, in Clarke’s (Citation1995) work where familiarity with content and a mentor’s confidence in a pre-service-teacher’s abilities were crucial factors supporting reflection. In contrast, open wh-questions such as “What do you think about it?” or “What happened in that part?” were found to lead to little, if any, reflection, because they were perceived (by in-service teachers) as a prelude to negative assessment (Kim & Silver, Citation2016).

The research cited above points to the importance of supporting teachers’ needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy to cultivate their reflection. Yet most work has explored these associations indirectly and seldom focused on in-service teachers. Guided by SDT conceptions and the limited empirical work described above, we hypothesized that the provision of support for in-service teachers’ basic psychological needs (competence, relatedness, autonomy) in a PD setting would predict reflectivity. That is, when teachers feel they participate in relevant, constructive, clearly structured discussions, where they are cared for, valued, and encouraged to voice their opinions, including criticism and frustrations, they may feel secure enough to reflect collaboratively and hence individually and to explore new courses of actions.

Relations among teachers’ needs support, reflection, autonomous motivation, and sense of personal accomplishment

Little research has connected teacher reflection (individual and collaborative), psychological needs support, and autonomous motivation for teaching (Dreer, Citation2020; Kaplan, Citation2014). As Watt and colleagues point out, “Motivation researchers have long considered teachers to play an important role in influencing students’ motivation for learning. Until quite recently they paid scant attention to teachers’ own motivation for teaching” (Watt et al., Citation2021, p. 1). This applies to teacher motivation as conceptualized by SDT and other dominant motivation theories, such as achievement goals theory (Butler, Citation2012; Daumiller et al., Citation2023; Kaplan, Citation2014; Roth, Citation2014). An exception to this trend is the relatively vast exploration of teacher self-efficacy, burnout, and attrition (Beymer et al., Citation2022; Chong & Kong, Citation2012; Richardson et al., Citation2014). In the following, we describe some of the empirical findings on teachers’ autonomous motivation and suggest possible relations to reflection.

Autonomously motivated teachers invest significant effort in teaching because of the interest they take in teaching, the pleasure they derive from it, or the value they attribute to it (Roth, 2014). This enables them to overcome periodic obstacles and prevents negative experiences from leading to exhaustion or burnout (Eyal & Roth, Citation2011; Friedman & Farber, Citation1992). Autonomous motivation for teaching is positively associated with teachers’ sense of personal accomplishment, that is, their sense that teaching enables them to realize their abilities and feel satisfied (Roth et al., Citation2007). Teachers’ autonomous motivation for teaching can protect them from depersonalization (Benita et al., Citation2019) and is positively correlated with autonomy-supportive teaching behaviors (Pelletier et al., Citation2002; Taylor & Ntoumanis, Citation2007) and with students’ autonomous motivation to learn (Roth et al., Citation2007).

Entering the teaching profession with autonomous motivation and a sense of personal accomplishment does not ensure that this motivation is sustained over time (Kyriacou & Kunc, Citation2007; Richardson & Watt, Citation2014). School contextual support for teachers’ competence, relatedness, and autonomy (e.g., through the principal’s leadership) can positively affect teachers’ autonomous motivation, whilst lack of support may negatively affect it (Benita et al., Citation2019; Eyal & Roth, Citation2011; Korthagen & Evelein, Citation2016). Whether contextual support of teacher needs within PD experiences (such as collaborative reflection) can support autonomous motivation for teaching has not been explored (Kunter & Holzberger, Citation2014). Research on the effectiveness of PD programmes, and those focusing on teacher reflection in particular, have not explored the relations between needs support, autonomous motivation, and sense of accomplishment. More broadly, since most research on teacher autonomous motivation is correlational and cross-sectional, allowing limited causal inferences (Richardson et al., Citation2014), scholars call for longitudinal, interventional, or semi-experimental studies that will shed light on the factors fostering teacher motivation for teaching (Kaplan, Citation2014).

In this study, we examined the hypothesis that teacher autonomous motivation and sense of accomplishment are fostered by the enhancement of teacher reflection. We based our hypothesis on literature that theoretically argues for the power of reflection to induce a sense of professional renewal (Schön, Citation1983) and to support teacher agency (Leijen et al., Citation2020) and sense of mastery and control (Larrivee, Citation2008), thus enhancing autonomous motivation for and sense of accomplishment in teaching.

Research hypotheses

In light of the consensus on the importance of teacher reflection but the paucity of research on the affective motivational challenges to and outcomes of in-service teacher reflection, we sought evidence of: (1) the effect of needs support on in-service teachers’ reflection; and (2) the effects of reflection on teachers’ motivation and wellbeing. More specifically, we tested the hypotheses that: (1) teachers’ perceptions of receiving support for their psychological needs (competence, relatedness, autonomy) in a PD programme would predict changes over time in reflectivity, and (2) these changes would predict changes in teachers’ autonomous motivation for and sense of personal accomplishment in teaching. We examined these hypotheses longitudinally; we could therefore control for time 1 measurement of reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and sense of accomplishment when we tested the association between perceptions of needs support and these variables in time 2.

Method

Context

This pre/post intervention survey study was part of a large design-based implementation research project in collaboration with the Israel Ministry of Education. The project was part of a reform aiming to support in-service teacher learning and leadership by implementing inquiry-into-practice in teacher learning communities and supporting their professional discourse (see Lefstein, Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2020). The larger research project examined teacher professional discourse and various related aspects of professional learning in teacher communities (e.g., Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2019, Citation2020).

Participants in the programme were predominantly teachers in elementary schools, with each school nominating 2–4 leading teachers. Leading teachers were expected to facilitate weekly in-school team meetings focused on collaborative reflective inquiry into problems-of-practice, that is inquiry in which teachers explored together their own and each other’s practice and reconsidered assumptions, beliefs, goals, choices, and actions, with the aim of improving their instruction and student learning. When joining this programme, the selected leading teachers participated in regional PD workshops (60 h) and received monthly in-school coaching visits. The workshop groups comprised 10–25 leading teachers each and were facilitated by research team members and/or district coaches trained by the research team.

In the workshops, leading teachers learned to facilitate collaborative reflective inquiry into problems-of-practice by participating in such inquiry, discussing its theoretical foundations, reflecting on its benefits and shortcomings, and facilitating it themselves. This included viewing together representations of classroom interactions and artifacts (e.g., classroom videos, student work), identifying problems-of-practice that these representations capture (e.g., how to give constructive feedback for a “wrong answer” in a diverse classroom), describing in detail the background related to the problem, the instruction depicted in the representation, student thinking, affect and behavior, and the subject matter involved. This was followed by a set of questions aimed at making sense of the focal problem, revealing underlying connections (between teaching, learning, and subject matter) and challenging related perceptions, interpretations, expectations etc. (e.g., What constitutes a “wrong answer”? What does this answer tell us about student thinking or affect? What is constructive feedback?). Based on this reasoning, which ideally gives voice to participants’ different ideas, the group explores various novel ways to manage the problem and their advantages and shortcomings, referring both to the classroom depicted in the representation and their own classrooms. To support these discussions, the workshop introduced facilitation tools, such as conversational protocols (McDonald et al., Citation2013; see Appendix A for an example).

At the beginning of the year, the workshop facilitators provided representations of practice for the group to practice reflective inquiry. The facilitators selected these representations from a library that offers representations of different school subjects, various grade levels, and various problems of practice. With time, leading teachers were expected to bring representations of practice from their own classrooms and share them for collaborative reflection. This means there was great variance between groups in terms of the representations and the problems they reflected on. It also means that in most meetings, participants explored others’ work, but they were expected to, at least once, engage in collaborative reflection on their own practice, and they were always encouraged to make explicit reflective connections to their own teaching. These experiences were accompanied by discussions of the benefits and challenges of individually reflecting about one’s practice and how reflective inquiry with colleagues can support the development of this capacity.

In Israel, initial teacher education for elementary schools typically takes place in a three-year college of education programme combining disciplinary and pedagogical content and results in a Bachelor’s degree and a teaching certificate. To obtain a teaching license, teachers need to complete a loosely supervised induction year. Further participation in formal PD programmes and Master’s degrees depends on inspectors, principals, or the teachers’ choice and is incentivized by rank and salary promotion. Connecting PD with material rewards may hinder teachers’ PD autonomous motivation (Naaman & Vedder-Weiss, Citation2023). Yet the design and facilitation of this PD programme included practices that could support participants’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. These practices included, for example: exploring problems that teachers find relevant and important and therefore choose to share, and encouraging them to voice their own ideas and challenge taken-for-granted assumptions (autonomy support); repeatedly emphasizing ethical guidelines (see appendix B) that construct a safe space for teachers to “open their classroom doors” and share their difficulties without fear of value judgment (relatedness); and adopting a generative stance in problem framing, presenting problems as actionable and manageable, as well as using scaffolds to facilitate the group reflection, such as video-viewing guidance (competence support).

Data collection

The data were collected in two large Israeli school districts during the 2016–2017 academic year (third year of the programme). Forty schools and 150 leading teachers participated in the programme that year; for 108 teachers, this was their first year. We administered pre- and post-surveys in all first-year leading teacher workshops (eight groups led by different facilitators, an average of 13 leading teachers per group); 92 teachers completed the pre-survey, but seven did not complete the post-survey. Therefore, the final sample comprised 85 teachers; 90% women, mean age 41.6 (SD = 7.5.), 17.4 mean years of seniority (SD = 6.7). All had an academic degree (43% Bachelor’s; 57% Master’s).

We administered the pre-survey (T1) at the beginning of the school year, personally visiting the workshops, handing out the printed survey, and allocating time to complete it. We administered the post-survey (T2) electronically. Teachers’ reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and sense of personal accomplishment were measured twice (at the beginning and end of the year); teachers’ perceptions of needs support provided by the group facilitators was measured only in the post-survey, when the teachers and facilitators were well acquainted, thus allowing a reliable estimation of teachers’ sense of facilitators’ support. This design allowed us to test the extent to which teachers’ sense of facilitators’ support predicted changes over time in teachers’ reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and sense of personal accomplishment. The surveys were anonymous and voluntary, meeting the requirements of the University ethics committee and the Chief Scientist at the Ministry of Education.

Measures

We used a Likert-type scale for the teachers’ survey responses, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (see appendix C).

Needs support

We modified the short version of the Teacher as Social Context survey (Wellborn, Citation1991) to measure teachers’ perceptions of the degree to which their workshop facilitator was supportive of their psychological need for competence, relatedness, and autonomy. The competence support subscale includes four items (e.g., “I feel the facilitator supports the development of my teaching capacity”), with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90. The autonomy support subscale includes four items (e.g., “I feel the facilitator encourages me to express my opinion and ideas”), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77. The relatedness support subscale includes five items (e.g., “I feel the facilitator cares about me”), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. Past research found high correlations among the three measures of the basic needs support and therefore combined them into one measure (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). We also found high correlations (between 0.58 and 0.75) and therefore combined the three sub-scales into one measure of basic needs support. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Reflectivity

The reflectivity measure was based on Luyckx et al. (Citation2008) scale that aligns with our definition of reflection as conscious examination aimed at improvement. We modified the scale to tap teaching as the focus of individual reflective tendency. The measure includes five items (e.g., “When I am failing to constructively connect to a student, I try to explore how to do it better”; “When I do not meet the goals I set in class, I try to understand why”). Cronbach’s alphas for pre- and post-measures were 0.80 and 0.85, respectively.

Autonomous motivation for teaching

We adapted the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (Ryan et al., Citation1991) to assess teachers’ interest, curiosity, and passion for teaching. The measure consists of six items (e.g., “I have great interest in my profession”; “I love my job”), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 and 0.84 in the first and second measurements, respectively.

Personal accomplishment

Personal accomplishment was assessed using Roth et al.’s (2007) shortened version of the scale constructed by Friedman and Farber (Citation1992), including three items (e.g., “I feel teaching allows me to utilize my abilities to the fullest”). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 in the first measurement and 0.77 in the second.

Analysis procedures

Teachers were nested in groups but given the small number of groups (eight), a full multilevel linear modeling was not suitable. Yet, to account for clustering we used cluster-robust standard errors (CR-SE) while estimating a single-level general linear model (McNeish et al., Citation2017). The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the dependent variables were low (nearly zero for autonomous motivation and personal accomplishment, and about 8% for reflection). However, the ICC for the perceptions of needs support was substantial (23%).

The analysis first included zero-order correlations for descriptive statistics and mean comparison between variables in T1 and T2 (t-tests). Then, to examine whether needs support predicted reflectivity at the end of the year, beyond initial levels of reflectivity, we used multiple regression analysis, controlling for reflectivity at T1. For this analysis, we used SPSS with estimation of cluster-robust standard errors (CR-SE). Finally, to examine whether perceptions of needs support predicted changes in teacher reflectivity throughout the year, which, in turn, predicted changes in autonomous motivation and sense of personal accomplishment, we used mediation analysis. In this analysis, we controlled for reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and personal accomplishment in T1. Since bootstrapping has been advocated as an alternative to normal-theory tests of mediation (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2004), we calculated the bootstrap confidence interval (with 20000 resampling) separately for each dependent variable (autonomous motivation, personal accomplishment), using Tofighi and MacKinnon (Citation2016) Monte Carlo confidence intervals code for R.

Findings

Descriptive statistics, including zero-order correlations among the studied variables in T1 and T2, are presented in . Correlations between the perception of needs support and the outcome variables of reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and personal accomplishment at T2 were positive and significant (0.44, 0.24, and 0.24, respectively).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Since the intervention was focused on enhancing reflectivity as a significant component of teacher professional learning, we first examined changes in this variable from T1 to T2. The mean level of reflectivity was 3.76 (SD = .61) in T1 and 4.16 (SD = .60) in T2. Means comparison using t-tests revealed the change was significant, t = 2.15 (df = 83), p = .02. Thus, on average, reflectivity increased during the first year of participating in the programme. We also hypothesized the change would be predicted by teachers’ perceptions of the extent to which the group facilitators were supportive of their psychological needs. Therefore, we conducted CR-SE, regressing reflection in T2 simultaneously on reflection in T1 and needs support. The results supported our hypothesis. Reflectivity in the first measurement predicted reflectivity in the second measurement (β = .370; t = 2.726; p =.009). More importantly, when we controlled for reflectivity in T1, perceptions of needs support were significantly associated with reflectivity in T2 (β = .304; t = 3.230; p =.002). This suggests perception of needs support predicted reflectivity at the end of the year, above and beyond levels of reflectivity at the beginning of the year. In other words, the more teachers perceived their facilitator as supporting their needs, the more reflective they were at the end of the year, irrespective of their reflectivity before the programme began.

In addition, we found a significant increase in autonomous motivation over time (see ), from 4.14 (SD = .50) in T1 to 4.36 (SD = .49) in T2; t = 1.96 (df = 83), p = .03. The increase in personal accomplishment (3.91 to 4.17) was not significant (but marginally so); t = 1.65 (df = 83), p = .051.

Findings from mediation analysis

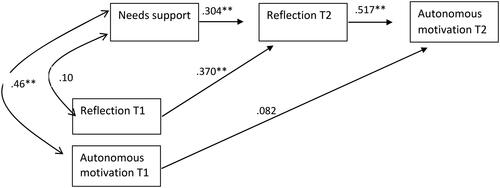

We hypothesized that when controlling for reflectivity, autonomous motivation, and personal accomplishment in T1, reflectivity in T2 would mediate the associations between facilitators’ needs support and autonomous motivation and personal accomplishment in T2. Bootstrapping mediation analysis (Tofighi & MacKinnon, Citation2016) showed that for autonomous motivation as a dependent variable, the 95% confidence interval was {.055; .285}, with an indirect effect value of 0.157. Because these intervals did not contain 0, the conditional indirect effect significantly differed from 0, at α = .05. presents the path diagram based on this analysis.

Figure 1. Basic needs support predicts changes over time in teachers’ reflection and teachers’ autonomous motivation.

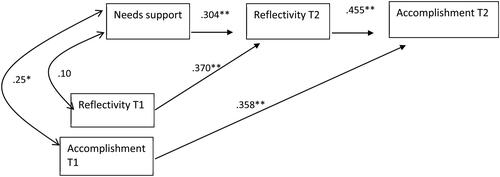

For personal accomplishment as a dependent variable, the 95% confidence interval was {.041; .269}, with an indirect effect value of 0.138. Again, because these intervals did not contain 0, the conditional indirect effect significantly differed from 0, at α = .05. presents the path diagram based on this analysis.

Figure 2. Basic needs support predicts changes over time in teachers’ reflectivity and in teachers’ sense of accomplishment.

*p <.05; ** p <.01.

The mediation analysis supported our hypothesis that perception of facilitators’ needs support predicted teacher reflectivity at the end of the year, and this, in turn, predicted autonomous motivation for teaching and sense of personal accomplishment in teaching. Moreover, perceptions of needs support predicted changes in reflectivity throughout the year, which, in turn, predicted changes in motivation and wellbeing. In sum, when initial autonomous motivation and personal accomplishment were controlled, increased reflectivity predicted increases in autonomous motivation and personal accomplishment (even though, on average, we did not find a significant increase in teacher sense of accomplishment during the year).

Summary of findings

The findings showed that teachers’ reflectivity and autonomous motivation for teaching increased during their first year in a PD programme focusing on collaborative reflective inquiry. Teachers’ sense of accomplishment had a similar trend, but the change was not significant. More importantly, the more teachers perceived facilitators as supporting their psychological needs in the collaborative reflection setting, the more likely they were to become more reflective and consequently to feel more autonomously motivated for and fulfilled by their teaching, irrespective of their initial levels of reflection, motivation, and sense of accomplishment.

Discussion

This study aimed to offer evidence that would advance the understanding of how to support in-service teachers’ reflection and the effect of reflection on in-service teachers’ motivation and wellbeing. It examined the hypotheses that: (1) teachers’ perceptions of receiving support for their psychological needs (competence, relatedness, autonomy) in a PD programme focused on collaborative reflection would predict changes over time in reflectivity; (2) these changes would predict changes in their autonomous motivation for teaching and sense of personal accomplishment in teaching. The findings confirmed these hypotheses, thereby providing evidence that psychological challenges in promoting reflection can be overcome for in-service teachers and offering a theoretical framework for designing an environment to promote teacher collaborative and individual reflection. The findings also expand outcomes of reflection to include motivational aspects. Thus, this study adds to teacher reflection research by suggesting teacher reflection may improve teaching not only by promoting professional knowledge and skills but also by promoting teacher motivation and well-being. It also adds to teacher motivation research by suggesting teacher motivation is malleable, even for veteran teachers, and may be fostered through PD designed to support teacher collaborative reflection and their need for relatedness, competence, and autonomy. Since teacher professional learning and their motivation for teaching are important for the quality of their teaching (Korthagen, Citation2016; Mälkki, Citation2019; Roth, Citation2014), these have important implications for classroom instruction and student learning.

Supporting and enhancing teacher reflection

Research on in-service teacher collaborative reflection has mostly focused on obstacles related to school culture and teacher discourse norms, neglecting psychological challenges and needs (Horn & Little, Citation2010; Larrivee, Citation2008). Our findings suggest supporting basic psychological needs is important to foster in-service teachers’ reflection. In our sample, reflectivity increased more for teachers who perceived their facilitators as better supporting their basic needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy in collaborative reflection settings. These findings align with previous research noting the challenges of promoting teacher reflection (Dreer, Citation2020), including teachers’ sense of a lack of skill and negative assessment (Clarke, Citation1995; Kim & Silver, Citation2016), their fear of criticism, embarrassment, and loss of face (Vedder-Weiss et al., Citation2019), and their sense that reflection does not address relevant issues (Attard, Citation2012; Jindal‐Snape & Holmes, Citation2009; Kim & Silver, Citation2016). This body of research, however, has seldom offered evidence that these challenges can be overcome for in-service teachers, nor has it offered a theoretical framework for designs that might contend with them.

The findings of this study suggest interventions seeking to promote reflection through on-going PD should consider how their design and facilitation support relatedness, competence, and autonomy in collaborative reflection. They should consider how to support teachers’ perception that the collaborative reflection facilitators care about them, appreciate their ideas, and acknowledge their will and voice and how the process can enhance their sense of competent reflection and, consequently, their teaching. For example, in the programme we studied, teachers were encouraged to reflect on problems they chose to share, ones they found personally relevant and important (sense of autonomy), and felt comfortable enough to display (sense of relatedness). Teachers were encouraged to voice their own ideas and challenge basic teaching assumptions (autonomy support), whilst the ethical guidelines that construct a safe space (e.g., the effort to suspend judgment) were repeatedly emphasized (relatedness support). They were encouraged to adopt a generative stance, framing problems as actionable and manageable and using scaffolds to facilitate the group reflection (competence support).

Supporting teachers’ need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in a collaborative reflection setting is easier said than done, especially as there may be tensions between the different needs and the means to support them. For example, one way to support autonomy in this context is to increase teachers’ sense of ownership and relevance by allowing them to choose the objects of reflection and to anchor reflective inquiry in representations of problems they bring from their own classrooms. Yet teachers are often hesitant to share problems-of-practice and classroom representations because they do not feel sufficiently competent and secure to discuss their problems with others; they would rather discuss someone else’s problems or deliberate over an unrelated representation, even at the cost of reduced relevance (Zhang et al., Citation2011). Thus, for a programme to optimally support all three psychological needs simultaneously, it must be designed so that it retains relevance and teachers’ interest (thereby satisfying the need for autonomy) but is not too ego-threatening (i.e., it does not undermine the needs for relatedness and competence).

Alternatively, one could argue for the provision of needs support in several stages. This could be achieved by, for example, engaging in critical reflection only after having established a safe environment for reflection through distinct, structured social activities. But teacher PD time is a limited and precious resource, and teachers - particularly experienced teachers - expect (often justifiably) direct applicability from the outset. Devoting extensive time to establishing a secure base for reflection may improve teachers’ sense of relatedness but could impair their sense of autonomy and competence. Furthermore, it may foster “contrived collegiality” (Hargreaves & Dawe, Citation1990) if the sense of relatedness is not rooted in a substantive collaborative goal. Further research is necessary to examine the relative impact of supporting the different psychological needs at different stages of PD and to empirically compare the outcomes of designs that support the three needs simultaneously with those of designs supporting them differentially.

Based on contemporary learning theories (Horn & Garner, Citation2022; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Putnam & Borko, Citation2000), the findings of this study indirectly suggest that psychologically supported by the facilitators, the teachers in the sample were able to productively participate in the PD reflective discourse and appropriate it, internalizing it as the way they thought about their practice. Thus, collaborative reflection was supported by needs support in the PD setting, and this, in turn, supported the development of teachers’ tendency to individually reflect on their practice, beyond the immediate context of the PD. According to the situative perspective, such increased individual reflectivity contributes reciprocally to the group’s ability to have productive collaborative reflective discussions. However, we did not examine the PD workshops and the facilitators’ actual behavior nor did we assess the quality of collaborative reflection discussions and other factors shaping it, such as peers’ psychological support. Future research should more directly explore the relations between needs support, collaborative reflection, and individual reflection. Such research could also examine which facilitation practices of collaborative reflection and which design principles support teachers’ psychological needs. It could also examine the role peers play in supporting each other’s psychological needs in collaborative reflection settings.

Motivational outcomes of teacher reflection

Previous research has demonstrated the importance of collaborative reflective inquiry for teacher PD, highlighting cognitive outcomes, such as professional knowledge and skills (Godínez Martínez, Citation2018; Levine & Marcus, Citation2010; Vescio et al., Citation2008). However, little work has investigated affective outcomes of reflection, such as autonomous motivation for teaching or personal wellbeing. Our findings add to the research on reflection by suggesting teacher reflection may improve teaching by bolstering teachers’ motivation and wellbeing. Thus, the findings reveal an additional benefit of teacher reflection and an additional rationale for supporting it. PD programmes fostering teacher reflection not only contribute to teachers’ knowledge and skills but can also support their autonomous motivation and sense of personal accomplishment in teaching.

We offer three explanations for the positive relations between increases in teacher reflectivity and increases in autonomous motivation and personal accomplishment. Whilst these explanations are interrelated, each emphasizes different benefits.

First, reflection can constitute professional renewal, reigniting interest in practices and processes that have become routine, even automatic. It can defamiliarize practice, shedding new light on everyday professional experiences, and this, in and of itself, may entail a sense of renewal. For example, in the programme we studied, teachers were encouraged to question taken-for-granted beliefs and practices and to explore novel alternatives. Teachers with a reflective orientation may view teaching as a continuous process of inquiry, a challenging and rewarding journey of curiosity and discovery (McGugan et al., Citation2023). Thus, they enjoy their teaching and find it fulfilling. In this sense, reflection may have particular merit for veteran teachers, as it helps them overcome the shortcomings of specialization, such as automatization and burnout:

As a practice becomes more repetitive and routine… [the practitioner] may suffer from boredom or burn-out…through reflection, he can surface and criticize the tacit understandings that have grown up around the repetitive experiences of a specialized practice, and can make new sense of the situation of uncertainty or uniqueness which he may allow himself to experience. (Schön, Citation1983, pp. 60–61)

Third, reflection may be experienced as an autonomous professional act and thus can prevent burnout resulting from teachers sensing their practice is controlled by policymakers and administrators, and their autonomy is subject to goals and standards set by others (Bryk et al., Citation2010; Dyson, Citation2020). In the current era of standardization and accountability, “the best antidote to take control of their teaching lives is for teachers to develop the habit of engaging in systematic reflection about their work” (Larrivee, Citation2008, p. 341). When teachers examine their practice in relation to goals they set for themselves, and when they initiate and regulate inquiry into problems-of-practice they find relevant and important, this may strengthen their sense of ownership of and control over their teaching, supporting their professional “emancipation” (Calderhead, Citation1989, p. 45). Such teachers may better identify with their practice, feeling it represents their beliefs and allows them to fulfill their destination.

Based on our findings, we argue designing PD to support teachers’ needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy in collaborative reflection settings can increase their reflectivity, which, in turn, can increase their motivation and wellbeing. Correlational research does not permit causal inference, however. Thus, one could also argue for the reverse causality, whereby teachers who were more autonomously motivated and had a stronger sense of accomplishment were more likely to be reflective and to increase their reflectivity, especially when encouraged to do so. Yet a longitudinal design that allows control for variables over time provides the best approximation for a claim for directionality. Our analysis shows that when controlling for initial reflectivity, perceptions of needs support predicted changes in reflectivity over time. In addition, increased reflectivity predicted increases in autonomous motivation over time, when controlling for initial level of autonomous motivation. These findings reinforce our assertion and further suggest teacher motivation is malleable, even for veteran teachers, and may be fostered through properly designed PD. More research is required to understand the mechanism of reflection’s effect on motivation in light of the three explanations above. Future work could also explore the effect of different teacher reflection models on motivation and possible variations between novice and veteran teachers.

Limitations and conclusions

Because of the relatively small number of groups and their small sizes, our ability to account for class and teacher levels was limited. Future research that more closely examines different facilitators, including their practices and relations to needs satisfaction, reflectivity, and motivational outcomes, could contribute to unpacking the effects revealed by our study.

Aspects of biased subjective estimations and social desirability might have played a role in teachers’ responses to the self-report tools we used. Whereas the common measurement of teachers’ reflection operationally defines it as a competency (e.g., Larrivee, Citation2008), our measurement focused on teachers’ tendency to reflect on their practice. Tendencies such as reflection, which do not always have a behavioral manifestation, are difficult to observe and therefore, despite the limitations, might be best measured using self-reports (Trapnell & Campbell, Citation1999). Given the variations in the definition of reflection, future research might employ a multidimensional measurement of reflection (Larrivee, Citation2008) to clarify relations between needs support and specific dimensions of reflection, as well as between the latter and teacher motivation, going beyond self-reports and turning to other methods to measure reflection.

Despite these limitations, this study suggests teachers’ reflection and autonomous motivation for teaching are malleable and may be enhanced by providing opportunities for collaborative reflection in ways that intentionally support teachers’ need for relatedness, competence, and autonomy. These could have significant implications for teachers’ well-being, the quality of their professional learning and collaboration with colleagues, and thus the quality of their teaching and their students learning.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, J. (2019). In search of reflection-in-action: An exploratory study of the interactive reflection of four experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102879

- Attard, K. (2012). Public reflection within learning communities: An incessant type of professional development. European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2011.643397

- Benita, M., Butler, R., & Shibaz, L. (2019). Outcomes and antecedents of teacher depersonalization: The role of intrinsic orientation for teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1103–1118. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000328

- Beymer, P. N., Ponnock, A. R., & Rosenzweig, E. Q. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of cost: Associations among job satisfaction, attrition intentions, and challenges. The Journal of Experimental Education, 91(3), 517–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2022.2039997

- Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey Bass.

- Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Easton, J. Q., & Luppescu, S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago University Press.

- Burhan-Horasanlı, E., & Ortaçtepe, D. (2016). Reflective practice-oriented online discussions: A study on EFL teachers’ reflection-on, in and for-action. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.002

- Butler, R. (2012). Striving to connect: Extending an achievement goal approach to teacher motivation to include relational goals for teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028613

- Calderhead, J. (1989). Reflective teaching and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 5(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(89)90018-8

- Carson, R. L., & Chase, M. A. (2009). An examination of physical education teacher motivation from a self-determination theoretical framework. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 14(4), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980802301866

- Chong, W. H., & Kong, C. A. (2012). Teacher collaborative learning and teacher self-efficacy: The case of lesson study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.596854

- Clarà, M. (2015). What is reflection? Looking for clarity in an ambiguous notion. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114552028

- Clarke, A. (1995). Professional development in practicum settings: Reflective practice under scrutiny. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(3), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00028-5

- Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2019). Teachers’ motivational approach: Links with students’ basic psychological need frustration, maladaptive engagement, and academic outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.002

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

- Daumiller, M., Janke, S., Butler, R., Dickhäuser, O., & Dresel, M. (2023). Merits and limitations of latent profile approaches to teachers’ achievement goals: A multi-study analysis. PloS One, 18(4), e0284608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284608

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process (2nd ed.). DC Heath and Company.

- Dreer, B. (2020). Towards a better understanding of psychological needs of student teachers during field experiences. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(5), 676–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1744557

- Dyson, L. (2020). Walking on a tightrope: Agency and accountability in practitioner inquiry in New Zealand secondary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 93, 103075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103075

- Eshchar-Netz, L., Lefstein, A., & Vedder-Weiss, D. (2023). Too old to learn? The ambivalence of teaching experience in an Israeli teacher leadership initiative. Teaching and Teacher Education, 130, 104186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104186

- Eshchar-Netz, L., Vedder-Weiss, D., & Lefstein, A. (2022). Status and inquiry in teacher communities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103524

- Eyal, O., & Roth, G. (2011). Principals’ leadership and teachers’ motivation: Self‐determination theory analysis. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(3), 256–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111129055

- Fendler, L. (2003). Teacher reflection in a hall of mirrors: Historical influences and political reverberations. Educational Researcher, 32(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032003016

- Feniger, Y., Goldshtein, J., & Vedder-Weiss, D. (2023). Professional learning communities under test-based accountability: Evidence from an Israeli intervention programme. Journal of Education Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2253201

- Fox, R. K., Dodman, S., & Holincheck, N. (2019). Moving beyond reflection in a hall of mirrors: Developing critical reflective capacity in teachers and teacher educators. Reflective Practice, 20(3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1617124

- Friedman, I. A., & Farber, B. A. (1992). Professional self-concept as a predictor of teacher burnout. The Journal of Educational Research, 86(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1992.9941824

- Godínez Martínez, J. M. (2018). How effective is collaborative reflective practice in enabling cognitive transformation in English language teachers? Reflective Practice, 19(4), 427–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1479688

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.2.143

- Hargreaves, A., & Dawe, R. (1990). Paths of professional development: Contrived collegiality, collaborative culture, and the case of peer coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(90)90015-W

- Hargreaves, A., & Shirley, D. (2009). The persistence of presentism. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 111(11), 2505–2534. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911101108

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Hoekstra, A., & Korthagen, F. A. J. (2011). Teacher learning in a context of educational change: Informal learning versus systematic support. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110382917

- Horn, I. S., & Little, J. W. (2010). Attending to problems of practice: Routines and resources for professional learning in teachers’ workplace interactions. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209345158

- Horn, I. S., Garner, B., Kane, B. D., & Brasel, J. (2017). A taxonomy of instructional learning opportunities in teachers’ workgroup conversations. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116676315

- Horn, I., & Garner, B. (2022). Teacher learning of ambitious and equitable mathematics instruction. Routledge.

- Husu, J., Toom, A., & Patrikainen, S. (2008). Guided reflection as a means to demonstrate and develop student teachers’ reflective competencies. Reflective Practice, 9(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940701816642

- Jindal‐Snape, D., & Holmes, E. A. (2009). A longitudinal study exploring perspectives of participants regarding reflective practice during their transition from higher education to professional practice. Reflective Practice, 10(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940902786222

- Kaplan, A. (2014). Theory and research on teachers’ motivation: Mapping an emerging conceptual terrain. In P. W. Richardson, S. A. Karabenick, & H. M. Watt (Eds.), Teacher motivation: Theory and practice (pp. 74–88). Routledge.

- Kim, Y., & Silver, R. E. (2016). Provoking reflective thinking in post observation conversations. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(3), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116637120

- Körkkö, M., Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., & Turunen, T. (2016). Professional development through reflection in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.014

- Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(8), 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.022

- Korthagen, F. A. (2016). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: Towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

- Korthagen, F. A., & Evelein, F. G. (2016). Relations between student teachers’ basic needs fulfillment and their teaching behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.021

- Kunter, M., & Holzberger, D. (2014). Loving teaching: Research on teachers’ intrinsic orientations. In P. W. Richardson, S. A. Karabenick, & H. M. Watt (Eds.), Teacher motivation: Theory and practice (pp. 105–121). Routledge.

- Kyriacou, C., & Kunc, R. (2007). Beginning teachers’ expectations of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.002

- Labaree, D. F. (2000). On the nature of teaching and teacher education: Difficult practices that look easy. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003011

- Larrivee, B. (2008). Development of a tool to assess teachers’ level of reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 9(3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802207451

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lefstein, A., Louie, N., Segal, A., & Becher, A. (2020). Taking stock of research on teacher collaborative discourse: Theory and method in a nascent field. Teaching and Teacher Education, 88, 102954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102954

- Lefstein, A., Vedder-Weiss, D., & Segal, A. (2020). Relocating research on teacher learning: Toward pedagogically productive talk. Educational Researcher, 49(5), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20922998

- Leijen, Ä., Pedaste, M., & Lepp, L. (2020). Teacher agency following the ecological model: How it is achieved and how it could be strengthened by different types of reflection. British Journal of Educational Studies, 68(3), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2019.1672855

- Levine, T. H., & Marcus, A. S. (2010). How the structure and focus of teachers’ collaborative activities facilitate and constrain teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.001

- Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers’ professional relations. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 91(4), 509–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819009100403

- Louie, N. L. (2016). Tensions in equity-and reform-oriented learning in teachers’ collaborative conversations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.001

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.004

- Mälkki, K. (2019). Coming to grips with edge-emotions: The gateway to critical reflection and transformative learning. In T. Fleming, A. Kokkos, F. Finnegan (Eds.), European perspectives on transformation theory (pp. 59–73). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marcos, J. J. M., Miguel, E. S., & Tillema, H. (2009). Teacher reflection on action: What is said (in research) and what is done (in teaching). Reflective Practice, 10(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940902786206

- McDonald, J. P., Mohr, N., Dichter, A., & McDonald, E. C. (2013). The power of protocols: An educator’s guide to better practice. Teachers College Press.

- McGugan, K. S., Horn, I. S., Garner, B., & Marshall, S. A. (2023). Even when it was hard, you pushed us to improve: Emotions and teacher learning in coaching conversations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103934

- McNeish, D., Stapleton, L. M., & Silverman, R. D. (2017). On the unnecessary ubiquity of hierarchical linear modeling. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 114–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000078

- Michou, A., Altan, S., Mouratidis, A., Reeve, J., & Malmberg, L. E. (2021). Week-to-week interplay between teachers’ motivating style and students’ engagement. The Journal of Experimental Education, 91(1), 166–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2021.1897774

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. (2020). Supporting reflection and reflective practice in an initial teacher education programme: An exploratory study. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 502–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1793946

- Naaman, K., & Vedder-Weiss, D. (2023). Teacher Learning Motivation: Why Does He/She Join a PD Program? The Eight International Conference on Teacher Education. MOFET Institute, Israel.

- Pelletier, L. G., Séguin-Lévesque, C., & Legault, L. (2002). Pressure from above and pressure from below as determinants of teachers’ motivation and teaching behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(1), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.186

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers: A Journal of the Psychonomic Society, Inc, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03206553

- Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176586

- Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

- Richardson, P. W., Karabenick, S. A., & Watt, H. M. (Eds.). (2014). Teacher motivation: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. (2014). Why people choose teaching as a career: An expectancy-value approach to understanding teacher motivation. In Teacher motivation (pp. 3–19). Routledge.

- Roth, G. (2014). Antecedents and outcomes of teachers’ autonomous motivation: A self-determination theory analysis. In P. W. Richardson, H. M. G. Watt, & S. A. Karabenick (Eds.), Teacher motivation: Theory and practice. pp xiii–xxii. Rutledge.

- Roth, G., Assor, A., Kanat-Maymon, Y., & Kaplan, H. (2007). Autonomous motivation for teaching: How self-determined teaching may lead to self-determined learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 761–774. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.761

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

- Ryan, R. M., Koestner, R., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Ego-involved persistence: When free-choice behavior is not intrinsically motivated. Motivation and Emotion, 15(3), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00995170

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Segal, A. (2019). Story exchange in teacher professional discourse. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102913.

- Sherin, M., & Van Es, E. A. (2009). Effects of video club participation on teachers’ professional vision. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108328155

- Slemp, G. R., Field, J. G., & Cho, A. S. (2020). A meta-analysis of autonomous and controlled forms of teacher motivation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103459

- Soenens, B., Berzonsky, M. D., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., & Goossens, L. (2005). Identity styles and causality orientations: In search of the motivational underpinnings of the identity exploration process. European Journal of Personality, 19(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.551

- Spalding, E., Wilson, A., & Mewborn, D. (2002). Demystifying reflection: A study of pedagogical strategies that encourage reflective journal writing. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 104(7), 1393–1421. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810210400704

- Sulzer, M. A., & Dunn, M. B. (2019). Disrupting the neoliberal discourse of teacher reflection through dialogical-phenomenological texts. Reflective Practice, 20(5), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1651713

- Svojanovsky, P. (2017). Supporting student teachers’ reflection as a paradigm shift process. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 338–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.001

- Taylor, I. M., & Ntoumanis, N. (2007). Teacher motivational strategies and student self-determination in physical education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 747–760. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.747

- Taylor, I., Ntoumanis, N., & Standage, M. (2008). A self-determination theory approach to understanding the antecedents of teachers’ motivational strategies in physical education. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.1.75