Abstract

Media are the arena where the discursive struggle over identities, cultures and geographies is carried out. Media organize our ways of thinking and acting vis-à-vis our ideas and perceptions of “us” and of “others.” With the proliferation of participative information technology, (young) media users reinforce or challenge media events through activities like sharing, liking and commenting. The MiDENTITY project addresses this phenomenon from a pedagogic perspective and provides a case study on the implementation of Critical Geographic Media Literacy in geography education. Its central purpose is to empower students to develop a self-determined way of media use thereby reflecting on their own online practices of social in- and exclusion.

Introduction

On a global scale, social coherence and political stability is threatened by an upsurge of populist politics, ethnic radicalization and religious fundamentalism (Hillebrand Citation2015, 8). In many countries including Austria and the U.S., political polarization has increasingly divided the electorate into several antagonistic camps that no longer acknowledge and embrace the existence of cross-cutting identities and interests among them and within the entire democratic spectrum. Instead of harnessing the transformative potential of opposing views, adverse groups view each other as a threat to their nation and ways of life (Somer and McCoy Citation2019, 8–9; McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Citation2018, 17). While such issues are not entirely new, the presidency of Donald Trump has certainly pushed them into the foreground. Using Twitter, he regularly engages in partisan politics, dehumanizes ethnic groups and entire countries, and labels the mainstream media as fake news (Mason, Krutka, and Stoddard Citation2018). As a parallel development, the media culture that informs democratic decision making and participation has become much more complex and diverse (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). Media environments effectively structure human interaction and can be understood as technologies that “give form to a culture’s politics, social organization, and habitual ways of thinking” (Postman Citation2000, 10). With the emergence of social online technologies, fundamental changes to the way information is consumed and shared have occurred. Editing and publishing text can be done from almost everywhere and by everybody with a cellphone or a tablet, information consumption has largely become public because of social media, and news are passed in real-time between online friends and peers, so that they are less likely to be challenged (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017, 11–12). This new era of ubiquitous information exchange is furthermore characterized by a public incredulity toward any claims of professional expertise (Mihailidis and Viotty Citation2017). In the limelight of fake news, disinformation and “twitter politics,” the once accepted distinction between factual truths and lies has gradually dissolved, so that the idiosyncratic concept of the (mediated) opinion has begun to replace more solid forms of science-based truths (Gordon Citation2018, 53). As a result, tendencies of social disruption are accelerated by various types of filter bubbles that increasingly reflect and shape how we perceive ourselves, those around us and what we take for “real” (Pariser Citation2011). From a psychological point of view, the algorithmic functioning of social media creates user-specific “truth effects” that can assume the status of common sense within the “echo chambers” in which they are circulated (Rochlin Citation2017, 389ff.). The ensuing multidimensional struggles over power of interpretation have adequately been described as “media spectacles” (Kellner Citation2009) that play out the hopes and fears of societies via the endless re-interpretation and merging of storylines of popular and/or tragic events around the world.

Such play of signification necessarily relates to geography. Geography functions as an apparatus of spatial intelligibility that plays a key role in the mediation and imagination of people, cultures and their respective locations (Shields Citation1991). In that vein, technologies of communication have ever since characterized processes of globalization. They have created contacts that would otherwise not exist and provided users and recipients with a spatial understanding of important matters such as identity, war, peace and development (Conover and Miller Citation2014, 85). Places, countries and regions are therefore not naturally meaningful and/or unchangeable. Rather, they are socially constructed and contingent on the interests, desires and concerns of those who seek to make them intelligibly within the realm of knowledge (Norton 1996, 357; Mui Ling 2003, 258). In this regard, place-making discourses are necessarily constitutive of power relations. Drawing from Foucault (1977, 27), “power and knowledge directly imply another, [so that] there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time the constitution of power relations.” Thus, matters of “reality” and “truth” are not cast in stone but the specific outcomes of power-knowledge configurations that may change over time and make way for alternative ways of imagining the world (Glasze and Mattissek 2009, 12). In the context of the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, for example, large parts of the world’s Muslim population are still shrouded in a discourse of hostile Orientalism (Gregory 2004) that perpetuates the old colonial logic of western dominance over the deviant “Eastern Other” (see Said 1978). Somewhat surprisingly, the Orientalist theme has been identified as one of the major negative stereotypes among young Austrians in the course of the MiDENTITY project. Even though Austria is neither a typical post-colonial nation nor a country with a large Muslim population, Viennese high school students clearly identified “Oriental looks” (e.g., men with beards and a darker complexion) as threatening.

As this suggests, young adults are particularly vulnerable to disinformation, manipulation and even hate speech via the media since they spend considerable time online and use content-sharing platforms like Snapchat and YouTube as their main sources of information and means of communication (Anderson and Jiang 2018; Rideout and Robb 2018). Against that background, schools, teachers and innovative geographers play an import role in providing learners with the necessary tools needed to better navigate a highly complex world that is characterized by a digitally augmented flow of (problematic) information, entertainment and advertising (Conover and Miller 2014). Lukinbeal (2014, 44) points out that as more diverse information becomes available about individuals, societies and cultures, geographic media literacy becomes more important, since “there is a need to engage in how space, place, subjectivity, and society are made meaningful through media and how these processes create, perpetuate, or subvert geographical knowledge as well as our participation in the world”. Geography, in that sense, is first and foremost an active pursuit. As Heffron (2012, 44) points out in the current update of the original Geography for Life Standards published in 1994 (Bednarz et al. 1994), it is essential that geography is understood as a subject that combines content knowledge with skills that enable learners to apply geographic thinking to make well-reasoned decisions and to solve actual problems. Such a geographic lens on the world would need to incorporate three basic assumptions:

Geographic representations, analyses, and technologies support problem-solving and decision-making by enabling students to interpret the past, understand the present, and plan for the future;

Human cultures and identities are deeply connected to the physical and human features that define places and regions;

Spatial patterns on Earth are ever changing and human actions contribute to the changes as people constantly modify and adapt to the realities of their cultural and physical environments. (Heffron and Downs 2012 qtd. in Heffron 2012, 44)

Essentially, the three assumptions cover what a geographically trained person knows and can do. They all acknowledge that geographic intelligibility and meaning is derived at the interface of human communication and action. In other words, the focus is on human driven geo-spatial processes instead of naturally occurring geographic phenomena and entities. In that vein, the sociologist Law (1994) has called long-ago for an orientation in the social sciences and elsewhere that acknowledges verbs (which denote processes) rather than nouns (which tend to refer to firm substances) since the world is never as complete or simple as substantives would suggest.

This line of thinking is also reflected in the 21st Century Skills Map for Geography (Partnership for Citation21st Century Skills 2009), which is the result of extensive research and feedback from educators and business leader across the United States. The skills map is designed in cooperation with the National Council for Geographic Education (NCGE). Its main goal is to provide teachers, learners and policymakers with concrete examples of relevant 21st century skills that should be implemented into the subject of geography. Among Creativity & Innovation, Critical Thinking & Problem Solving, etc., Media Literacy is identified as a core requirement. It involves:

Understanding how media messages are constructed, for what purposes and using which tools, characteristics and conventions;

Examining how individuals interpret messages differently, how values and points of view are included or excluded and how media can influence beliefs and behaviors;

Possessing a fundamental understanding of the ethical/legal issues surrounding the access and use of information. (Partnership for Citation21st Century Skills 2009, 6)

As this shows, understanding the formative power of media culture is a clear concern from a geographic point of view. MiDENTITY addresses this pressing issue in an Austrian context and presents a civic/media education approach to geography teaching that shall equip young people with adequate skills to cope with the modern conundrum of mediated uncertainty and manipulation with regard to matters of discourse, identity and space.

Unlike in Germany or the U.S., in Austria geography is designed as an interdisciplinary subject that combines the fields of geographic, economic and civic education with the aim to empower learners to responsibly partake in the global and diverse living conditions of today. Accordingly, this article explores how geography education can further high school students’ skills and abilities to adequately orient themselves in a highly complex, spatially interwoven world that is increasingly brought to their attention by the media. Which strategies can help students understand that matters of “true” or “false” and “good” or “bad” are often contingent on (political) perspectives? Which analytical tools do they need to realize that social identities are constructed by means of representing and articulating certain actors with certain (stereotypical) traits (Hall 2009 [1997]); and finally, how can learners be motivated to interact with (online) peers and “others” in a responsible-minded way?

The article presents findings from the MiDENTITY project. This cross-institutional research project had a duration of two years (2017–2019) and was funded by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research within the frame of the research program Sparkling Science.1

It involved 79 high school students (grade ten) and teachers from three different schools in Vienna as well as researchers from the Department of Geography at Vienna University. The input phase of the project consisted of three consecutive half-day classroom workshops that engaged learners over a full academic year. The workshops were designed to gradually explore the production and circulation of spatial, ethnic and national stereotypes via the media and investigated mechanisms of in-group and out-group building in pupils’ (social) media practices and peer-to-peer interaction. Central was the development of a specific handbook for Critical Geographic Media Literacy, based on the circuit of culture (Du Gay et al. 1997; Hall 2009 [1997]) and Fairclough’s (2003) approach to critical discourse analysis. Both concepts were adapted and simplified for the intended recipients and context. This paper mainly focuses on the first workshop for the reason that the project’s central purpose is to put critical geographic media literacy into practice. However, a comprehensive overview on the entire project is given.

In the following, theoretical foundations are discussed as far as relevant for this paper. Subsequently, our specifically designed toolkit for critical media analysis in geography education is presented. Lastly, the paper reflects on challenges and chances in terms of doing critical media analysis in the geography classroom.

Critical media literacy, language and the contestation of space

Over the last two decades, there has developed a growing need for media education in the school curriculum. Kellner and Share (2007) give an overview of the most influential approaches to teaching (critical) media literacy, ranging from a protectionist approach (keep media away from young people) to a more open media and arts education approach (focusing on creativity and self-expression) to the actual critical media literacy model (CML) we are proposing here for ideology critique and civic education (Kellner 2000, 220). There is emphasis on the productive abilities of learners. As Lukinbeal (2014, 43) explains,

through learning and applying principles of analysis and understanding as well as engaging critical pedagogy and learner-centered education practices, geographic media literacy can provide deeper levels of learning as we shift our educational model away from interpreters of pregiven texts to producers of meaning.

It is worthwhile to highlight the learner-centeredness in Kellner’s and Lukinbeal’s approach. Only when students are encouraged to make their own decisions, reflect on their actions and the possible outcomes, they begin to perceive themselves as self-efficacious members of society who recognize both their opportunities and their responsibilities (Gudjons 2014).

In the 21st century, critical media literacy has become a widely accepted and broadly applicable educational model that expands the notion of critical literacy (e.g., from literary theory) to mass communication, popular culture and the chances and challenges of new technological affordances. It enables students to critically analyze the relationship between media, information and power, and it helps them realize their creative potential as active prosumers in the media saturated environment of today (Kellner and Share 2007). Following Kellner and Share (2005, 369), this generally “involves gaining the skills and knowledge to read, interpret, and produce certain types of texts and artifacts and to gain the intellectual tools and capacities to fully participate in one’s culture and society.” Translated to the requirements of critical geographic literacy, this could involve the analysis of phenomena, texts or events that help students grasp how space is used to include, exclude, empower or dominate particular social groups (Morgan 2000, 283). For instance, privately managed spaces such as gated communities and shopping malls generally restrict access to less affluent or ethnically stigmatized members of society. Such control of urban space thus shows in an exemplary way that inclusion and exclusion is a matter of human definition and intervention. Asking such questions gives individuals power over their culture by enabling them to perceive the status quo of a given situation as contingent. Furthermore, they are empowered to actively recreate meanings and identities by transforming the social conditions of their societies and cultures (Kellner and Share 2005, 381). At the core of this lies a post-modernist understanding of the relationship between the symbolic (text, language, images, etc.) and the material world.

As Weedon (1997, 21) points out, language is not a mirror of reality but the productive site where our subjectivities and forms of social interactions are constantly shaped and altered. It is a social-semiotic repository that can be creatively utilized to construct identities and social conditions (Cameron and Kulick 2003, 102). Probably the most comprehensive and accessible account on language, representation and culture has been put forward by Paul du Gay and Stuart Hall. In their influential model of “The Circuit of Culture,” Du Gay et al. (1997) understand culture as a shared set of meanings, which is neither finite nor forever fixed but continuously transformed by so-called signifying practices – that is, the use of signs (e.g., text, language, body language, images, sound, etc.) in order to create meaning. In this process (called representation), meaning is negotiated by producers and consumers as both meaningfully interpret the signs that are being used (Hall 2009 [1997], 3). Meaning making furthermore depends on the modes of regulation in a particular context. Regulation determines what is accepted as normal or legal and thus governs the three other coordinates of the circuit: production, consumption and identity. Production and consumption entail the cultural economy side of the model since they offer the supply and demand aspects of identities in the making. That way, what we consume (e.g., fashion) and produce (e.g., a social media profile) contributes to the reading of ourselves and may also define our individual sense of belonging. Our (multiple) identities thus also depend on the available systems of meaning that are provided by our culture. They make intelligible who we can possibly be and how we are readable to others (Hall 2009 [1997], 3f.). To belong to the “same” culture thus implies to be able to read similar signs, follow similar rules, have similar values and relate to similar ideas. Foucault has defined such bodies of knowledge as discourses, meaning “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (Foucault 1972, 49). In this process, discourse and language are co-constitutive. Language is a carrier of discourse and simultaneously the supposedly innocent means by which our world becomes understandable, communicable, manageable und also re-imaginable.

Considering the protean nature of language and representation vis-à-vis their huge cultural force, it is mandatory that learners understand that geographical labeling (and any labeling of sorts) does not necessarily provide an accurate or neutral depiction of their social and spatial surroundings. Rather, it effectively creates worlds, offers possibilities, and produces action (Morgan 2002). With school geography in mind, Kim (2019) proposes a deconstructive reading of geo-related matters and representations to promote a more critical thinking about (mediated) global issues. He argues that it is necessary to disturb students’ totalizing geographical ideas in order to foster a fairer understanding of global others and more responsible action toward them. With a critical pedagogy of space in mind, MiDENTITY has opted to specifically develop a ready-to-use program and tool kit for young adults that can help them make use of the emancipatory potential of the deconstruction of discourse in the geography classroom and in everyday life. For this purpose, we have harnessed some of the main tenets of critical discourse analysis.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as proposed by Fairclough (2003) and Gee (2001) turns the interplay between text and discourse into a heuristic opportunity. Texts (spoken, written, etc.) are seen as social practices capable of shaping reality by means of the concrete language, grammar, structure, metaphors and arguments they use as well as the range of social possibilities that they convey. By using particular structures, expressions, and ideas rather than others, particular worldviews are privileged whereas others are silenced (Fairclough 2003, 23f.). As political instruments, texts can either assure or challenge mainstream discourses (Gee 2001, 2); however, they cannot refuse to take a stance. Finally, one must keep in mind the power of the reader as the final creator of “meaning” and “reality.” Whatever recipients deduce from the writings and readings of others will always depend on their individual worldviews (Widdowson 1998, 149). Critical discourse analysis thus acknowledges the contingency of textual meaning and seeks to account for plausible ways of reading texts. Although there is no right interpretation of a text and it is impossible to grasp all possible ways of reading a particular text, the strength of the method lies in its applicability in a multitude of research settings (e.g., all social issues involve discourse) and its strength to reveal what type of reading possibilities certain texts might encode (Wodak 1999). Consequently, and for the purpose of this paper, the combination of the above outlined circuit of culture with key assumptions of critical discourse analysis offers a promising heuristic framework to better understand how young people assign meaning to themselves and others as they consume and produce information via their social media accounts.

So far, a considerable number of researchers and educators have attempted to implement forms of (critical) media analysis in school and university teaching. However, since MiDENTITY has a geographic background, we have mainly focused on and drawn from work that combines media analysis with matters of belonging, identity and place-related imaginations. To that effect, Kostogriz and Tsolidis (2008) worked with students from the Greek diaspora in Australia and investigated how they would define their multinational identities. In the self-images the learners created, aspects of communication with family members living abroad, popular culture, traveling and cultural heritage appeared to be among the most relevant aspects, demonstrating how young people of the diaspora linked their transnational sense of self to memory, communication and a range of shared spatial moorings. Charlton et al. (2011, 2014) and Wyse et al. (2012) collaborated with pupils and teachers of two primary schools in Great Britain. In a text-based setting, they explored how these children negotiated place-related identity in their reading and writing practices as well as in spoken interaction. The project of Charlton et al. (2014, 170)

[is instructive because it] potentially encourages a move away from thinking about the local as fixed, something children should “learn about,” and more towards how children and their stories so far, along with the other living and non-living trajectories they encounter, contribute to the construction and re-creation of “their place.”

Equally focusing on reading as a practice of geographic meaning making, Spring (2016) carried out a series of group discussions and individual interviews with teenagers from two different Canadian communities. All participants were keen readers and given the task to interpret matters of place-identity in their own lives and in two young-adult fiction texts. Findings show that the teenagers’ interpretation of the novels largely corresponded with their personal conceptualizations of place and identity. However, as Spring (2016, 368) notes, some participants also demonstrated the ability to move beyond their personalized preconcepts. This indicates not only their critical reading abilities, but also their disposition to envision matters of place and identity in ways that differ from generic cultural templates.

Both aspects are important for the critical media analysis (CMA) model devised for the MiDENTITY project since the emancipatory skill of deconstruction is combined with the creative potential of alternative imagination. Taking a step into that direction, Somdahl-Sands (2015) has drawn from Said (1978) and investigated students’ Orientalist mental maps of the Middle East. Students examined suitable media sources and discussed their findings in a blog format with their peers. As participants analyzed their colleagues’ responses, they became cognizant of how media representations have shaped their geographic imaginations by including or omitting certain points of view and/or giving/not giving voice to counter narratives. Presenting an equally useful approach, Haigh (2016) outlines the advantages of implementing Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) in geography education. Pointing out that many learners have difficulties in naming and recognizing hidden ideological implications in media discourse, Haigh (2016, 165) proposes a structured investigation of four levels of causation that can lie beneath any visible media phenomenon, ranging from systemic causes to worldviews and subconscious belief systems. Haigh’s findings indicate that a profound analysis of underlying narratives, myths and power-configurations is a viable vehicle for critical geographic thinking, self-exploration and civic education. Childs (2014) takes a similar approach but with a stronger focus on popular culture, addressing the problematic category of “race.” He investigates how black stereotypes are perpetuated in rap music, where false commercial identities are frequently linked to violence, materialism, and demonized images of African Americans in order to promote higher album sales (Childs 2014, 296). His study suggests that as the United States are becoming more ethnically diverse, it becomes increasingly important for young people to recognize how the media shapes their ideas about “racial” identity and the impact it has on their self-perception and their perception of others. This, of course, also holds true for Austria. However, Childs (2014, 294) concedes that matters of “race” and “racial” prejudices are still not sufficiently addressed in the classroom due to the sensitivity of the topic. Addressing that issue, Bondy and Pennington (2016) explore how critical media analysis can be utilized to raise awareness about the damaging effects of “racial” bias, demonstrating how learners can actually challenge such exclusionary practices in a classroom context. The study investigates how Latin@s2 (but this could also be other minority groups) are represented in the U.S. media and how frequent negative associations (e.g., depictions as illegal aliens, criminals) influence how young people come to understand Latin Americans in terms of citizenship and civic rights. Bondy and Pennington provide a teaching model that combines elements of media analysis with creative assignments. Students are encouraged to write counter-narratives to mainstream representations of latin@-culture, so that “students enact the power to determine whose stories [of what being Latin@ means] are told and how” (Bondy and Pennington 2016, 108). Thus, students do not only perceive how the media shapes their understanding of the world, people and cultures, they are also given the opportunity to explore the potential of semiotic counter action. That is, they become aware that it is in their power to tell different stories that speak back to the false reality they perceive as imposed. In essence, this mirrors the two basic ideas behind the CMA tool kit we have developed in the course of the MiDENTITY project. Firstly, learners shall realize that stereotypes about people and cultures can be deconstructed by critically interrogating various forms of media. Secondly, they shall learn how problematic media content can be challenged by media users’ shared practices.

The literature suggests that there have been several attempts to incorporate critical media education in schools and academia. Yet, it can be argued that there is still a scarcity of studies that combine critical media analysis with aspects of “doing” place-related identities online. In a joint venture of geography and Cultural Studies, MiDENTITY makes visible the relations between learners’ (social) media practices and their conceptions of self and other against the background of society, democracy and civic education. In the following section, the background, aims and structure of the MiDENTITY project is outlined. Subsequently, our specifically designed critical media analysis toolkit is presented.

MiDENTITY—What is it about?

The interdisciplinary MiDENTITY project is a cooperation between researchers, high-school students and teachers. Central to the project are the questions of how young people from Vienna define themselves, how they delineate their various in-groups and how they perceive their out-groups in terms of nation, ethnicity and culture. Issues of uneven power-relations and hierarchies between social groups are considered from a civic education perspective. Students should thus be empowered to use and evaluate social media in a critical and emancipatory manner. To achieve this, MiDENTITY combines three main aims:

The first aim was to explore young people’s strategies of identity construction in the migration society of Vienna, drawing upon insights from a multidisciplinary framework, including Critical Geography, Cultural Studies, and Migration Pedagogy (see Mecheril 2010). Quantitative and qualitative methods were used to investigate which discourses mattered for the identity categories of Viennese high school students in terms of nation, ethnicity and culture. A comprehensive online survey was delivered to all secondary schools in Vienna. The survey yielded a large number of valid results (n = 1372), which were used to design a group discussion format to gain more detailed insights. In eight discussion rounds, 79 students from three different schools were encouraged to reflect on matters of in- and out-group bias, and the concept of identity. The findings from the group discussions indicate that national stereotypes are frequently used to naturalize negative forms of ethnic othering (e.g., aggressiveness as supposedly natural national trait) and that participants generally acknowledge the hybridity of their own identities (e.g., they identify as Turkish-Austrians), while they perceive others in rather exclusive and mono-dimensional ways (e.g., African foreigners).

The second aim was to introduce learners to our critical media analysis toolkit. The toolkit is structured in the form of a handbook with a step-by-step guide that accompanies learners through their individual critical media analysis projects. Furthermore, the toolkit is designed for flexible use. While it is primarily intended for high school students, it is also meant to be used in teacher training, so that techniques and methods can be transferred to more Austrian schools.

The third aim of MiDENTITY was to address the everyday online behavior of participants from a civic education point of view. Learners were encouraged to reflect on their individual (media) practices and envision them in more socially inclusive ways. This was facilitated by the close interaction between researchers and students during the whole project, which gave room for intense discussions about complex concepts such as “identity,” “belonging,” related emotions, and practices of in- and exclusion.

MiDENTITY is based on moderate constructivism (Reich 2008) and aims at learner-centeredness (Gudjons 2014) first and foremost. Thus, learning tasks should be relatable to foreknowledge and learner interests. Following the didactic principles of construction, reconstruction and deconstruction, students are actively involved in the construction of meaning, the reproduction of already established interpretations and the critical interrogation of supposedly right judgements and true values (Reich 2008). Additionally, the concept of migration pedagogy (Mecheril 2010, 2016) plays an important role. Acknowledging the growing importance of migration in Austria, practices of ethnic and cultural exclusion are problematized in a classroom context, so that students are encouraged to rethink their practices of self-positioning and defining others.

Project design – Collaboration between researchers, students and teachers

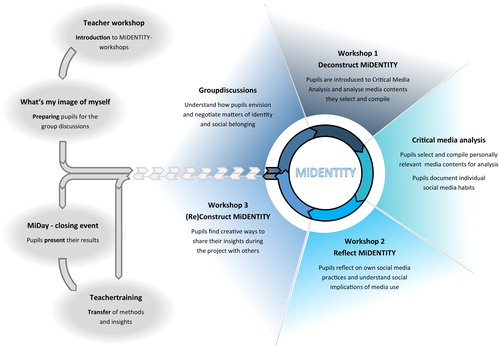

The collaboration with the three classes from three different schools in Vienna lasted throughout the first year of the project. illustrates the organization of workflow. An initial meeting with the teachers (Teacher Workshop) was convened to plan the activities at school and to introduce our critical media analysis toolkit. Subsequently, the group-discussions marked the first face-to-face contact between students and researchers. The group discussions served as an icebreaker and yielded interesting insights regarding students’ strategies of self-positioning, othering, and their use of markers of identity. Departing from the term “identity” over an impulse-picture, the discussions were loosely guided by pre-set questions, each one allowing for an open-ended debate. The focus groups consisted of eight to ten students from the same class and two members of the research-team as moderator and minute-taker. The discussion setting was different to regular classes. Learners were the experts from whom we as researchers wanted to learn. This created confidence and a positive atmosphere, so that both researchers and students looked forward to the remaining stages of the project, which consisted of three half-day-workshops, a phase of instructed text analysis and reflection at home. Finally, the project was topped off with a festive closing event with the participants of all three schools. Thus, all 79 students had to undergo the same training and had to complete the same tasks.

As this article focuses on the first workshop “Deconstruct MiDENTITY” and the actual implementation of critical media analysis in a classroom context, this aspect is described in greater detail further below. At this point, suffice it to say that the main goal of the first workshop was to practice critical media analysis with the learners. They produced their own media stories, shared them with their peers and analyzed each other’s contributions in a closed online format. For the sake of completeness and clarity, a short description of the two other workshops is included. In the second workshop, “Reflect MiDENTITY,” we emphasized the relationship between identity politics and social media usage. Learners were encouraged to understand that liking, disliking, and commenting on social media are social practices that create self-images and that make users intelligible to others. The third workshop, “(Re)construct MiDENTITY” was then aimed at sharing learning outcomes beyond the classroom. Each group of students had to choose one core message or insight which they considered particularly important. Their task was to find a creative way to communicate their message to people from their communities, families, friends, and/or other students. Attempts ranged from articles for the school magazine to elaborate videos on YouTube. All contributions were presented at the University of Vienna during the MiDENTITY – Day. This was the closing event, where all students of the three schools finally came together to share their insights and talk about their experiences.

The MiDENTITY-handbook – Toolkit for critical geographic media literacy

The critical media analysis handbook itself is a compilation of assignments that guide the analytic steps carried out by the students. In a first step, the learners worked in pairs and created an individual media story by compiling various existing pieces of media coverage pertaining to a larger topic of their choice. This was achieved with the help of the online curation tool Scoop.it, which enabled learners to easily browse, visualize and share information in creative ways. The second step involved the actual analysis of a story shared by another pair of students from another school. Finally, the analysis was handed back to the original teams and made visible to all participating students for the purpose of reflection and further discussion. In the main analytical part (second step), these five categories were used, addressing the following questions:

• Representation: What is shown, what is not? Which voices are included/excluded? Which actors are associated with which actions? How reliable is the source?

• Regulation: What is presented as “true”? What is presented as “good,” “right” or “moral”? How is this effect achieved? What ideologies/myths/views of the world can be found?

• Signs: How are these impressions and “truths” produced? What means – linguistic, visual etc.- are employed to communicate them? How are these means combined? What connotations do they relate to? What emotions could they provoke? What do they provoke in me?

• Production: Where does the money go? How are consumers guided through the text? Who is communicating with whom and about what? What is the objective of the text / media product? What is the role of advertising? What is the information-entertainment-relation?

• Identities – Target Groups: Who are the addressees of the text? Which social groups use/ produce these media? What do they use it for? What may be their goals? What possibilities do they have to participate? What role do “echo-chambers” play in the construction of identities in the story? (see Du Gay et al. 1997, modified for the purpose of the MiDENTITY project).

These five analytical categories comprise the main part of the MiDENTITY handbook. They were introduced to the students during Workshop 1 (compare ). To approach the rather complex heuristic design and to familiarize the students with the overall goals of CMA, several learner centered activities preceded the actual analytical tasks. For instance, a major aim was to raise awareness about underlying ideological tendencies in and different perspectives on texts in general.

Workshop 1 – Deconstruct MiDENTITY

At first, learners were familiarized with the methods and procedures of critical media analysis. Therefore, the researchers analyzed examples of popular media texts (e.g., advertising posters) together with the students to introduce the five analytical categories specified above. Impressions and associations of the student group were used to illustrate that the same media text can be approached from different angles and that one should thus always consider multiple reading positions. After this initial input, students worked in three teams to analyze examples of different media-texts prepared by the research-team under a specific focus. In this practical session, they were given the opportunity to employ the framework of critical media analysis and adapt it specifically to the task. Upon completion, each team gave an elevator pitch to their colleagues to report on the aspects they had concentrated on and the insights they had gained.

Group one focused on the aspects of target-groups, production and representation. They were asked to compare three articles that promoted different approaches to dieting and working out for a “healthy” body weight. One article was taken from a men’s health magazine, another one from a women’s magazine and a third one from a website about DIY medical advice. The students had to read the articles in detail and define the intended target groups. Students were then asked to identify the markers of identity presented in the different texts for each target group (e.g., what body-features are constructed as desirable for whom?). Finally, they were encouraged to explore possible underlying ideological assumptions in the texts (e.g., what counts as normal, healthy, etc.?) vis-à-vis the commercial interests that may have been involved.

Group two focused on the categories signs, production and target groups. They listened to two different radio broadcasts on the same news topic. The first was from the Austrian national radio, the second from a privately-owned channel. The students were encouraged to make a comparison regarding the ratio of information and entertainment (infotainment), the role of advertising, intertextuality (e.g., references to online offerings) and the possible target groups of the channels. Learners also looked for concrete expressions and terms that could indicate less obvious connotative/ideological contents.

Group three watched a video advertising fast food. The assignment focused on representation, signs, production and target groups. Learners investigated how the male and female characters enacted “their” gender roles regarding eating habits, the sharing of domestic tasks and preferred spare time activities. The goal was to identify what was represented as “right,” “good,” and “normal” in the video in order to better understand underlying ideologies and gender stereotypes. On the level of signs, students were encouraged to interpret how sounds, imagery and text interacted. Subsequently, they considered which emotions these compositions might have triggered in them. Finally, learners reflected upon possible target groups of the video and related the assumed interests of these groups to the overall communicative strategy of the clip.

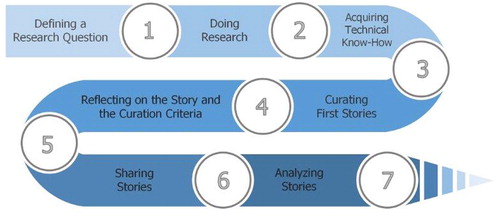

Next, students worked in pairs. They were given time to decide on a larger topic area that they would want to talk about on social media. In order to facilitate the process, students were given a list of prechosen topics. At the time, all of these topics were controversially discussed in Austria and any media research about these topics by the students would likely have revealed conflicting discourse positions. For instance, topics included “National pride (e.g., in the context of sports),” “Face cover ban in Austria,”3 “Citizenship” or “Flight and Migration.” Students were asked to pick a topic or field and narrow it down to the aspects they were interested in. That way, we intended to create a natural social media situation, where users come across a story or a topic they find interesting and subsequently put it up for discussion. Accordingly, learners followed seven steps ():

Defining a research question: The students had to find a real “research question” that helped them focus on a specific aspect of their larger topics.

Doing research: The students then searched online for further information with the help of the basic research-guidelines specified in the handbook. Those included explanations on the working logics of search engines and how to use them most effectively, as well as instructions on how to check the trustworthiness and quality of a source.

Acquire technical know-how: The curation tool Scoop.it was introduced and connected with previously installed Facebook accounts. Students’ Facebook accounts were specifically created for the MiDENTITY project and added to a closed group. As learners worked in pairs, they shared one Facebook and one Scoop.it account. Instruction was given on how to use Scoop.it to create a new media-story from preexisting content by rearranging it and commenting on it, etc.

Curating first stories: For a test-run, students were encouraged to build their first story consisting of at least three topical media texts which they had to find, select, arrange and comment on.

Reflecting on the story and the curation criteria: Students reflected on their decision-making processes considering questions such as: On what grounds did we choose our media-texts? Why did we decide on a specific order? Why did we opt for that media-product and not for another one?

Sharing stories: Students shared their stories with their peers in the closed Facebook group.

Analyzing stories: Students critically analyzed their peers’ stories, posting their comments to the group.

Working with the MiDENTITY handbook

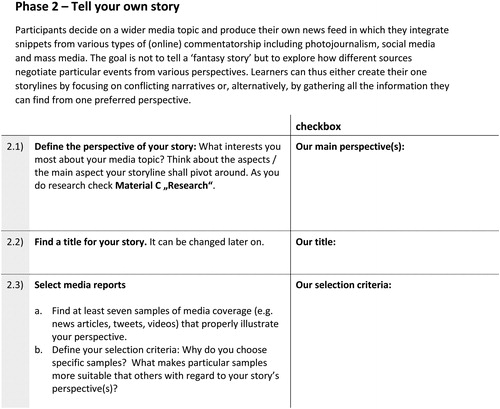

After students had successfully completed the first workshop, they were adequately prepared for the next project phase. Working mostly independently, pairs were given six weeks to either broaden their stories from workshop one or compile a new, more substantial story from the topic range. Learners took responsibility for their own small research projects, following the seven steps outlined above with the help of their handbook and the support of their teachers. Once a topic had been decided on, students had to define a research question and choose a title for their story. They then reflected on their selection criteria. It was necessary to explain convincingly why certain pictures, posts, articles and videos etc. had been chosen while others had been ignored. By their choice of content, the order they arranged it in, the title and their comments, students were able to add new layers to the existing stories, twist them, challenge them, contrast them or enhance them by combining them intertextually. Students were free to concentrate on one specific way of interpretation or compare different ones. They could either argue from their own perspective or attempt to find arguments from a conflicting position. Either way, a chosen reading position had to be explained with reasonable examples.

The educational aim of this task was to create an opportunity for the students where they could perceive themselves as story-makers with the power to really spread a message. At the same time, they were encouraged to reflect on their daily decision making when they use social media. This was done to raise their awareness about their responsibilities as producers and publishers of content. Consequently, each assignment in the handbook included a checkbox for reflective notes. illustrates how the guidelines and assignments of the handbook were organized.

After the participants had finished and shared all their stories, each student team analyzed one story posted by another pair. The research team made certain that exchanges were always across schools in order to ensure the anonymity of all participants. The analytical tasks and steps included the close reading of all the fragments of the story as separate media products as well as a contextual analysis which looked at the story as a whole, revealing its full meaning potential. In their analyses, students followed the guidelines and assignments specified in the handbook on the basis of the five analytical categories explained above. Additionally, they could draw on further information on source-checking, ideologies/worldviews and rhetorical elements that is equally provided by the handbook.

At the end of this phase, the results of the analyzed media stories were handed back to the original story authors and shared with the entire group of student-researchers. By reading what their peers have commented on their stories, the authors became aware about the possible effects of their stories. They experienced that their intentions had maybe been misunderstood or ignored at some point, or they realized that others focused on elements they had included without giving them a second thought. Sometimes, they noticed that they had initiated reflection processes in their readers; alternatively they had the impression that their arguments had failed to come across. In a nutshell, processes of meaning-making became more tangible and visible to most participants. In his reflection on the workshops, one student admitted:

I learned that I better don’t trust all media. There are a lot of fake news around trying to influence people. That’s why I started to double check posts which seem funny to me. (reflection of a participating student, translated from German)

Discussion and conclusion

In the 21st century, critical geographic media literacy has become an essential skill. It builds an understanding of the role of the (participatory) media as a world-shaping device and it helps learners perceive how the meaning of cultures, places and people is constantly challenged or cemented via an endless flow of communication. We have argued that young people need adequate strategies and insights to competently take part in the contested media worlds of today and that they should be able to do so in a socially responsible way. As this article has suggested, the multifaceted subject of geography is particularly suited to create learning opportunities to promote such an endeavor. Based on quantitative and qualitative findings, we developed a toolkit for critical media analysis in the geography classroom. The toolkit was then successfully tested within the course of the MiDENTITY project, a collaboration between researchers of the University of Vienna and three schools in Vienna.

The open project design of MiDENTITY (workshops instead of standard lessons) and the action- and learner-centered approach facilitated intensive learning phases and individual learning results. It proved fruitful to put students in the role of experts. That is, they were not asked to give correct answers to default questions but were invited to explore a topic of their choice together with the university researchers. Based on the concepts of citizen science and action research, students specified their own research questions and independently worked on their topics. Due to the nonhierarchical setting, MiDENTITY opened opportunities for student feedback and critical discussions without the fear of being judged and graded by a teacher. This also promoted peer feedback and interactive learning from others. In their project diaries, for instance, some students reported that they had not been aware about the manifold layers of meaning that can reside in one cultural product, e.g., a poster. They also stated that they would henceforth interpret media stories more critically. Furthermore, many learners acknowledged their willingness to reconsider their social media practices and to be more careful about the contents they like or share. For some students, the reflection on their media use was eye opening as they realized how much time they spend on social media – in some cases, more than eight hours daily. Consequently, some students told us that they started self-experimenting with media abstinence.

Some technical aspects caused problems in our workshops. Mainly, this was due to the use of a freeware-version of Scoop.it, which was chosen because it offered the best set of functions for our intended purpose. Storify, another online compilation tool, had been used successfully by Mihailidis and Cohen (2013) in their study on digital media literacy education. However, it was unreliable at the time we planned our workshops and was finally shut down in October 2018. Even though Scoop.it performed adequately in our testing phase, it confronted us with unexpected difficulties in the classroom. As soon as a large number of students attempted to simultaneously access the website via the same Wi-Fi spot, the service became extremely unreliable and denied user logon.

Besides, the time-management of the project turned out to be more challenging than expected. Even though the three teachers, who were mainly involved in the project, coordinated the workshops at their schools professionally, organization proved to be difficult since access to computers and the flexibility of school timetables was limited. Consequently, the project came into conflict with the school curriculum. This caused difficulties for the involved teachers who had to find a workable balance between project activities and standard curriculum teaching. However, the Austrian government’s new issuance for Digital Basic Education (BMBWF 2018) in all schools of lower secondary education may help raise the “legitimacy” of future project work on critical media education. In this regard, we support Carr and Porfilio’s (2009) claim for a compulsory curriculum for critical media literacy at all school levels.

Varying skill levels and a great linguistic diversity among students were challenging too. While we had taken this into account beforehand, some already simplified tasks of critical media analysis still turned out to be very demanding for students with a rather limited command of the German language. Carver et al. (2014, 236) faced similar problems when implementing frame analysis in a biology class. In other cases, the learners appeared to be convinced to “know it all already” and therefore failed to engage with the tasks wholeheartedly.

However, these challenges provided the research team with valuable insights for the future adaption of the materials and the workshop designs. Firstly, there may be a need to further simplify our toolkit for critical media analysis. A possible way to achieve this would be to focus only on one media product and not on compiling actual media stories online. Another option would be to break down the analytical procedure into smaller parts and adapt them as suitable. This would allow for smaller learning steps at a time. Since face-to-face discussions with students gave us the best insight in their learning processes, we would consider limiting the use of online curation tools. It can also be an option to omit online tools entirely and produce a story in the form of an analog collage instead. This might appear contradictory to our original intention since the focus of the project was on social media. However, critical thinking is not limited to the deconstruction of specific cultural artifacts. That is, insights gained in an analog setting can and should be transferred to the virtual world at a later stage. It is conceivable that this could help avoid situations where weaker learners are overwhelmed by the complexity of actual (online) media spectacles, so that they can be introduced to CMA more slowly and gradually.

Lastly, it should be pointed out that our case study focuses particularly on the local socio-spatial context and issues that were occurring in Austria during the time of the case study. While migration and negative stereotyping played a huge role in this context, it is conceivable that the application of critical geographic media literacy in other countries/regions may have a different focus and design.

To conclude, this article has suggested that critical media literacy is an indispensable skill for teachers and students alike. This is especially true in the context of geography, which is a subject that combines content knowledge with critical skills that enable learners to apply geographic thinking to make informed decisions and to solve actual problems. Consequently, the MiDENTITY team aims to further entrench critical geographic media literacy as a part of geography teaching in teacher training and at schools in Austria over the next years.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christiane Hintermann

Christiane Hintermann is Assistant Professor for Geography and Economic Education and Human Geography at the Department of Geography and Regional Research at Vienna University. Her research areas include didactics of geography and economic education, civic education and intercultural education as well as geographic migration research, geographic memory research and their interrelations with educational questions and concerns.

Felix Magnus Bergmeister

Felix Magnus Bergmeister studied Geography and Economic Education and obtained his PhD in the field of human geography. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Geography and Regional Research at Vienna University. His research interests include didactics of geography and economic education, cultural studies, media studies, and critical development studies.

Viola Anna Kessel

Viola Kessel studied Geography and Economic Education as well as Spanish as a foreign language. She is a geography teacher and was engaged in the MiDENTITY project at the Department of Geography and Regional Research at Vienna University as a junior researcher. Currently, she works in the field of educational cooperation at the Goethe-Institut in Buenos Aires.

Notes

1 The main characteristic of the highly competitive program is the integration of pupils of different ages (primary and secondary level) in research projects as young scientists who work side by side with researchers (https://www.sparklingscience.at/en/).

2 The @-symbol is used in Spanish to refer to women and men as it mirrors the suffixes - a (female) and –o (male).

3 The Anti-Face-Veiling-Act entered into force in Austria in October 2017. The law bans people from covering their faces in public places. A violation is sanctioned with an administrative penalty of 150 Euro (cf. BGBl. I Nr. 68/2017).

References

- Anderson, M., and J. Jiang. 2018. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/05/PI_2018.05.31_TeensTech_FINAL.pdf.

- Bednarz, S. W., N. C. Bettis, R. G. Boehm, R. M. Downs, J. F. Marran, R. W. Morrill, and C. L. Salter. 1994. Geography for life: National geography standards. Washington: National Geographic Society.

- BMBWF. 2018. Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Bildung, mit der die Verordnung über die Lehrpläne der Neuen Mittelschulen sowie die Verordnung über die Lehrpläne der allgemeinbildenden höheren Schulen geändert werden. (= BGBl. II Nr. 71/2018). https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2018_II_71/BGBLA_2018_II_71.pdfsig.

- Bondy, J. M., and L. K. Pennington. 2016. Illegal aliens, criminals, and hypersexual spitfires: Latin@ youth and pedagogies of citizenship in media texts. The Social Studies 107 (3):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00377996.2016.1149045.

- Cameron, D., and D. Kulick. 2003. Language and sexuality. Cambridge: UP.

- Carr, P. R., and B. J. Porfilio. 2009. Computers, the media and multicultural education: Seeking engagement and political literacy. Intercultural Education 20 (2):91–107. doi: 10.1080/14675980902922200.

- Carver, R., E. Bruu, F. Wiese, and J. Breivik. 2014. Frame analysis in science education: A classroom activity for promoting media literacy and learning about genetic causation. International Journal of Science Education, Part B 4 (3):211–39. doi: 10.1080/21548455.2013.797128.

- Charlton, E., G. C. Hodges, P. Pointon, M. Nikolajeva, E. Spring, L. Taylor, and D. Wyse. 2014. MyPlace: Exploring children’s place-related identities through reading and writing. Education 3-13 42 (2):154–70. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2012.662521.

- Charlton, E., D. Wyse, G. C. Hodges, M. Nikolajeva, P. Pointon, and L. Taylor. 2011. Place-related identities through texts: From interdisciplinary theory to research agenda. British Journal of Educational Studies 59 (1):63–74. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2010.529417.

- Childs, D. J. 2014. Let's talk about race: Exploring racial stereotypes using popular culture in social studies classrooms. The Social Studies 105 (6):291–300. doi: 10.1080/00377996.2014.948607.

- Conover, G. D., and J. C. Miller. 2014. Teaching human geography through places in the media: An exploration of critical geographic pedagogy online. Journal of Geography 113 (2):85–96. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2013.846396.

- Du Gay, P., S. Hall, L. Janes, H. Mackay, and K. Negus. 1997. Doing cultural studies. The story of the Sony Walkman. London: Sage/The Open University.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse of language. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York: Pantheon.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and punish: The birth of the modern prison. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York: Pantheon.

- Gee, J. P. 2001. Discourse analysis: Theory and method. New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Glasze, G., and A. Mattissek. 2009. Diskursforschung in der Humangeographie: Konzeptionelle Grundlagen und empirische Operationalisierungen. In Handbuch Diskurs und Raum: Theorien und Methoden für die Humangeographie sowie die sozial- und kulturwissenschaftliche Raumforschung, ed. G. Glasze and A. Mattissek, 11–60. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Gordon, M. 2018. Lying in politics: Fake news, alternative facts, and the challenges for deliberative civics education. Educational Theory 68 (1):49–64. doi: 10.1111/edth.12288.

- Gregory, D. 2004. The colonial present: Afghanistan: Blackwell.

- Gudjons, H. 2014. Handlungsorientiert lehren und lernen. Schüleraktivierung - Selbsttätigkeit – Projektarbeit. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Haigh, M. 2016. Fostering deeper critical inquiry with causal layered analysis. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 40 (2):164–81. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2016.1141185.

- Hall, S. 2009 [1997]. Introduction. In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices, ed. S. Hall, 1–12. London: Sage Publications.

- Heffron, S. G. 2012. GFL2! The updated geography for life: National geography standards, second edition. The Geography Teacher 9 (2):43–8. doi: 10.1080/19338341.2012.679889.

- Heffron, S. G., and R. M. Downs, eds. 2012. Geography for life: National geography standards. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Council for Geographic Education.

- Hillebrand, E. 2015. Die populistische Herausforderung. – Eine Einführung. In Rechtspopulismus in Europa: Gefahr für die Demokratie? ed. E. Hillebrand, 7–11. Bonn: Dietz.

- Kellner, D. 2009. Media spectacle and media events: Some critical reflections. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/essays/2009_Kellner_MediaEventsJulyFINAL.pdf.

- Kellner, D., and J. Share. 2005. Toward critical media literacy: Core concepts, debates, organizations, and policy. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 26 (3):369–86. doi: 10.1080/01596300500200169.

- Kellner, D., and J. Share. 2007. Critical media literacy is not an option. Learning Inquiry 1 (1):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s11519-007-0004-2.

- Kellner, D. 2000. Multiple literacies and critical pedagogies. In Revolutionary pedagogies: Cultural politics, instituting education, and the discourse of theory, ed. P. Trifonas, 195–221. New York: Routledge.

- Kim, G. 2019. Critical thinking for social justice in global geographical learning in schools. Journal of Geography 118 (5):210–3. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2019.1575454.

- Kostogriz, A., and G. Tsolidis. 2008. Transcultural literacy: Between the global and the local. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 16 (2):125–36. doi: 10.1080/14681360802142054.

- Law, J. 1994. Organizing modernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lukinbeal, C. 2014. Geographic media literacy. Journal of Geography 113 (2):41–6. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2013.846395.

- Mason, L., D. Krutka, and J. Stoddard. 2018. Media literacy, democracy, and the challenge of fake news. Journal of Media Literacy Education 10 (2):1–10. doi: 10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-2-1.

- McCoy, J., T. Rahman, and M. Somer. 2018. Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: Common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. American Behavioral Scientist 62 (1):16–42. doi: 10.1177/0002764218759576.

- Mecheril, P. 2010. Migrationspädagogik. Weinheim: Julius Beltz.

- Mecheril, P. 2016. Handbuch Migrationspädagogik. Weinheim: Julius Beltz.

- Mihailidis, P., and J. N. Cohen. 2013. Exploring curation as a core competency in digital and media literacy education. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2013 (1):2. doi: 10.5334/2013-02.

- Mihailidis, P., and S. Viotty. 2017. Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: Civic expression, fake news, and the role of media literacies in ‘post-fact’ society. American Behavioral Scientist 61 (4):441–54. doi: 10.1177/0002764217701217.

- Morgan, J. 2000. Critical pedagogy: The spaces that make the difference. Pedagogy, Culture and Society 8 (3):273–89. doi: 10.1080/14681360000200099.

- Morgan, J. 2002. Teaching geography for a better world? The postmodern challenge and geography education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 11 (1):15–29. doi: 10.1080/10382040208667460.

- Mui Ling, H. 2003. From travelogues to guidebooks: Imagining colonial Singapore 18191940. Sojourn 18 (2):257–78.

- Norton, A. 1996. Experiencing nature: The reproduction of environmental discourse through Safari tourism in East Africa. Geoforum 27 (3):355–73. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7185(96)00021-8.

- Pariser, E. 2011. The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. London: Penguin.

- 21st Century Skills Map for Geography. 2009. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519501.pdf.

- Postman, N. 2000. Building a bridge to the eighteenth century: How the past can improve our future. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc

- Reich, K. 2008. Konstruktivistische Didaktik: Lehr- und Studienbuch mit Methodenpool. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

- Rideout, V., and M. B. Robb. 2018. Social media, social life: Teens reveal their experiences. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media.

- Rochlin, N. 2017. Fake news: Belief in post-truth. Library Hi Tech 35 (3):386–92. doi: 10.1108/LHT-03-2017-0062.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism. London: Routledge.

- Shields, R. 1991. Places on the margin: Alternative geographies of modernity. London: Routledge.

- Somdahl-Sands, K. 2015. Combating the orientalist mental map of students, one geographic imagination at a time. Journal of Geography 114 (1):26–36. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2014.882966.

- Somer, M., and J. McCoy. 2019. Transformations through polarizations and global threats to democracy. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681 (1):8–22. doi: 10.1177/0002716218818058.

- Spring, E. 2016. Where are you from? Locating the young adult self within and beyond the text. Children’s Geographies 14 (3):356–71. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2015.1055456.

- Wardle, C., and H. Derakhshan. 2017. Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Weedon, C. 1997. Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Widdowson, H. G. 1998. The theory and practice of critical discourse analysis. Applied Linguistics 19 (1):136–51. Accessed August 23, 2018. . doi: 10.1093/applin/19.1.136.

- Wodak, R. 1999. Critical discourse analysis at the end of the 20th century. Research on Language & Social Interaction 32 (1):185–93. doi: 10.1207/S15327973RLSI321&2_22.

- Wyse, D., M. Nikolajeva, E. Charlton, G. C. Hodges, P. Pointon, and L. Taylor. 2012. Place-related identity, texts, and transcultural meanings. British Educational Research Journal 38 (6):1019–39. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2011.608251.