Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon and in relation to geospatial conceptualizations focusing on the geographical concepts of location, distribution and interaction. Data consists of 134 responses from 12-13-year-old students who completed an assignment in the Swedish national test in geography (2013). The responses were analyzed using thematic analysis. Data was complemented with interviews in 2017. Results show that many students hold alternative conceptions of the Gulf Stream in relation to geographical concepts, which implies that instruction should focus on students’ geographical contextual understanding, including map-reasoning skills.

Introduction

This paper engages with geography education and focuses on 12-13-year old students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream. This Atlantic Ocean current is an important geographical phenomenon in the context of Northern Europe and North America, and has received much attention lately in the light of climate change.

In this study, students’ conceptions of the Gulf Stream were investigated from a conceptual change perspective, assuming that students develop their conceptual understanding of natural phenomena by using their existing knowledge. Some of these conceptions can be described as alternative conceptions, which are conceptions that differ from scientific expert views, and are generated from everyday experience and culture (Lane, Carter, and Bourke Citation2019; Mintzes, Wandersee, and Novak Citation1997; Sexton Citation2012). Findings in science and geoscience education research has shown that students bring their alternative conceptions into the classroom and use these as a lens for organizing and interpreting scientific knowledge in order to construct meaning. Furthermore, alternative conceptions, in contrast to scientific views, may appear more functional and useful to students in their everyday life. They may be firmly embedded in students’ wider conceptual framework, restricting them in developing new complex scientific conceptions (Duit and Treagust Citation2003; Lane and Coutts Citation2015; Lane, Carter, and Bourke Citation2019; Sexton Citation2012).

Although there is on-going research on students’ alternative conceptions concerning a wide range of natural phenomena in geography and geoscience education (Cheek Citation2010; Dove Citation2016), few studies have investigated students’ conceptions about the ocean, and from our knowledge, none with a focus on ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream. Furthermore, understanding scientific concepts, principles and processes in the oceans is important in both physical geography as well as ocean science education. However, physical geography also includes different geographical perspectives which provide students with a more holistic understanding of the ocean. This is vital in a time where we need to respond to complex issues such as climate change and pressures on ocean resources (Tran, Payne, and Whitley Citation2010). Lane and Coutts (Citation2012) describe deep geographical knowledge of natural phenomena as being acquired by students when these are explored in relation to the distinct geographical concepts of place, scale, location, spatial distribution, interaction and interdependence. Furthermore, students’ understanding of natural phenomena in relation to these concepts are particularly important for research and practice in geography education, as it introduces students to how the discipline views and explains the world, as well as the nature of its gaze (Lambert and Morgan Citation2010; Lane, Carter, and Bourke Citation2019). Such a geographical gaze or perspective has been discussed in terms of geographical or relational thinking (Lambert Citation2016) in a European context, and as spatial thinking in an American context (Jo Citation2018). Students who have acquired deep geographical knowledge of natural phenomena (e.g., tropical cyclones, earthquakes, and ocean currents) should not only be able to explain the scientific concepts, principles and processes underlying these, but also explain these in relation to geographical contexts, concepts and perspectives, thus, demonstrating an understanding of geographical questions such as: ‘where’, ‘why here’ and ‘to what extent’. This type of reasoning requires both spatial thinking and contextual geographical knowledge, and can therefore be described as geospatial thinking (Favier and van der Schee Citation2014; Huynh and Sharpe Citation2013; Ishikawa Citation2013, Citation2016; Jo Citation2018), or as we propose, acts of geospatial conceptualization. In this context, the act of conceptualization can be described as a process involving stages in learning where students progressively define, classify, analyze and apply concepts (Gregory and Lewin Citation2015; Lane, Carter, and Bourke Citation2019). Goodchild (Citation2001) has argued that “geographic” is embedded in spatial, thus the former term is essentially the same as the term geospatial (see Golledge, Marsh, and Battersby Citation2008). Here we use geospatial conceptualization and geographical concepts.

This study contributes to this field of research by investigating 12- to 13-year-old students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon in relation to different types of geospatial conceptualizations, focusing on three central geographical concepts. The empirical study is based on student responses in the Swedish national test in Geography for grade 6.

The following questions directed the present study:

What are students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon?

How do students understand the Gulf Stream in relation to the geographical concepts of location, distribution and interaction?

The structure of this article is inspired by the Model of Educational Reconstruction (MER). The model builds on the European continental tradition of Didaktik and emphasizes that the teachers’ understanding of students’ conceptions and science content needs to be equally considered when designing instruction. According to Duit et al. (Citation2012) science content should not be viewed as given but needs to undergo a reconstructional process, where elementary ideas (basic phenomena, principles, and processes) are transformed into a content structure for instruction. In this process, elementary ideas have to be detected in relation to the aims of instruction while considering students’ perspectives (e.g., alternative conceptions). The model has been used as a framework for designing teaching of geoscience topics such as plate tectonics, wind systems, water springs, glaciers and the ice age (Felzmann Citation2017; Reinfried et al., 2015). The model includes three components; i) analysis and clarification of science subject matter and its educational significance, ii) investigation of students’ perspectives on the chosen subject, and, iii) design and evaluation of learning environments. This article focuses mainly on the two first aspects of the model.

At first, we provide scientific research of the Gulf Stream, describing its path, processes, effects on climate, plants and animals and ways this ocean current is important for humans. We also present how the Gulf Stream becomes a reconstructed content for students, relating science content to the content in textbooks and the syllabus in middle school geography in Sweden. The focus of this article is students’ conceptions and understanding of the Gulf Stream, and previous research, perspectives, material and methods of the study are presented. The results and discussion sections present students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon and in relation to different geospatial conceptualizations focusing on the geographical concepts of location, distribution and interaction. We conclude by bringing forth implications for instruction and discuss future research in terms of interventions studies.

The Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream was first described by the explorer Ponce de León in 1513, when sailing from Puerto Rico and crossing the current north of Cape Canaveral on the way to Tortuga. At that time, Spanish ships were sailing on the Gulf Stream to gain favorable winds on their return voyage to Spain. Furthermore, there have been many attempts to explain the mechanisms of the Gulf Stream throughout history (Stommel Citation1965) and today we recognize the Gulf Stream as one of the most powerful ocean currents in the world. This current transport warm water from its origins in the Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico to its end in the North Atlantic (Berger Citation2009; Meinen and Luther Citation2016), creating a warm climate and a natural habitat for plants and animals in parts of Europe and Scandinavia.

Processes

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) is a system of ocean currents in the Atlantic, carrying warm upper waters northwards through the Atlantic, which gradually cool and release heat to the atmosphere when exposed to the dry and cold atmosphere in the high latitudes. While wind-driven stress is the main driving force of basin-wide circulation in the upper part of the water column, deep convection also contributes to the circulation of deep water in the Atlantic Ocean. Deep water is formed when it reaches the polar and sub-polar regions where it becomes cold and saline enough to sink due to the processes of thermal contraction, evaporation and brine rejection. Whilst evaporation removes the distilled water and leaves the salt in the ocean, brine rejection increases the salinity even further as water freezes to ice. As a result, deep water continuously sinks and fills the abyss and then slowly returns to the south throughout the Atlantic Ocean (Cushman-Roisin and Beckers Citation2011; Kuhlbrodt et al. Citation2007; Rayner et al. Citation2011).

Location and distribution

The Gulf Stream, which is the northward upper limb of AMOC, originates in the Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico and flows to the high latitudes of the North Atlantic Ocean (Dong, Baringer, and Goni Citation2019; Meinen and Luther Citation2016). It flows through the Straits of Florida, where it is named the Florida current, and then meanders across the Mid-Atlantic Bight and returns to the coastline on the eastern seaboard of Canada. When progressing eastward in the Atlantic it is named the North Atlantic current (Meinen and Luther Citation2016) or North Atlantic drift, which represents the northern arm of the Gulf Stream in the mid and high Atlantic (O’Hare, 2011). On its way, the transport in the Gulf Stream changes from being a contained flow in a channel to a meandering free jet, and in the end as a topography-controlled boundary current. When passing through the western North Atlantic it becomes wider and much deeper (approximately 4000 meters) (Meinen and Luther Citation2016).

Interaction

Climate and climate change

The transport of warm water by the Gulf Stream and the release of heat to the atmosphere, is often described as the reason why Europe has mild winters when compared to other places at the same latitude. However, reasons for this zonal anomaly are still debated among scientists. One side argues that it is due to the heat stored during the summer in the upper 100 meters of the Atlantic Ocean off shore of Europe, and later released to the atmosphere as a result of Westerlies mixing the surface waters in the winter (Riser and Lozier Citation2013; Seager et al. Citation2002). The other side argues that the heat stored in these surface layers in the eastern Atlantic Ocean at the latitudes of Northern Europe would only be sufficient to keep the winters mild until December during an average year. Hence the remainder of the winter needs an additional heat source, which most likely is the Gulf Stream (Palter Citation2015; Rhines, Hakkinen, and Josey Citation2008; Riser and Lozier Citation2013). One interesting theory of the Gulf Stream by Kaspi and Schneider (Citation2011) acknowledges these two sides to some extent, focusing on the atmospheric circulation where the jet stream and arctic air are emphasized. The theory describes how heat is released by the Gulf Stream along the east coast of the USA, which creates a low-pressure system near Iceland and a high-pressure system on the eastern edge of North America. The low-pressure system delivers heat to Europe via the jet streams´ south-westerly winds, picking up heat released during the winter along the Gulf Stream. Simultaneously, arctic air is drawn into the high-pressure system in North America, making the temperature differences more obvious between Europe and North America (Riser and Lozier Citation2013). Another topic under discussion concerns a more sluggish Gulfstream in the future, which depends on the stability, or a possible shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Circulation (AMOC) due to climate change. A shutdown is also considered as one of the possible tipping points in the climate system (Castellana et al. Citation2019) and accordingly of specific interest from a general earth system perspective. Whether the Gulf Stream is slowing down or not has also been debated among scientists. For example, Rossby et al. (Citation2014) states there has been no decrease in surface transport at all in the Gulf Stream during the past 20 years. Additionally, Riser and Lozier (Citation2013) describes a shutdown is unlikely as the strength and path of this current depend largely on the large-scale mid-latitude winds, which do not change significantly whilst the Arctic ice melts. On the other hand, new research shows that the AMOC has indeed weakened during the mid-twentieth century, and that the Gulf Stream is changing, induced by the on-going climate change (Caesar et al. Citation2018; Caesar et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, in line with latter research, models predict that a slowdown (or potential shutdown) may lead to cooling of the North Atlantic region and less precipitation in northern latitudes (Jackson et al. Citation2015).

Nature - plants and animals

Many animals and plants, such as various forms of plankton, drift in the ocean during various stages of their life. This also includes large animals such as fish and sea turtles who spend their juvenile life drifting, the former as (e.g., larvae, eggs) (Hays Citation2017). For example, hatchling loggerhead turtles disperse from land, become entrained in the Gulf Stream and transported by the North Atlantic gyre during many years of growth (Witherington Citation2002). The Gulf Stream also transports Sargassum, brown algae that act as floating habitats, supporting various fish, birds, sea turtles, invertebrates and marine mammals and acts as a nursing ground for juvenile fish off the US southeast coast (Casazza and Ross Citation2008). Ocean currents are important in the evolution of ecosystems and sensitive to change, thus climate change may alter many ecosystems in the Atlantic Ocean in the future.

Humans

Berger (Citation2009) describes that the way the Gulf Stream affects people depends on the dominant air pressure systems (the North Atlantic Oscillation), which is more or less a regular variation in differences in air pressure at sea level in Iceland and off the coast of Iberia. When there is a large difference in pressure between these locations (Iceland Low and Azores High are both strong) humans will benefit. The low-pressure system drags in moisture-laden air from the south, which has been warmed by the Gulf Stream system. Then the south-westerly winds drive warm water into the Norwegian Sea and up to the Svalbard archipelago. At the same time the Azores High makes the trade winds stronger, which helps turning the gyre, making the Gulf Stream stronger. This in turn leads to upwelling of cold water outside Iberia and the African coast, containing nutrients which make fish thrive and algae grow. In contrast, when the difference in pressure is small between these locations (Iceland Low and Azores High are both weak), the trade winds, westerlies and the Gulf Stream weakens. As a result, winters become colder and dryer in north Western Europe and upwelling of cold water decreases off Iberia and north western Africa and the local fishing industry suffers. In addition, people in the US may also experience a negative effect from the Gulf Stream; as this current receives heat from the Caribbean Sea, storms are fueled along the southern east coast (Berger Citation2009).

The Gulf Stream: Reconstructed content for students

For decades, geography has been the only subject covering Earth Science in the Swedish compulsory school, and it has always been a small part of the curriculum. Similar to many other countries, oceanography has been a neglected domain in the curriculum (Guest, Lotze, and Wallace Citation2015; King Citation2010; Tran, Payne, and Whitley Citation2010) with little focus on ocean processes and currents. The Swedish syllabus year 4-6 states that geography education “should give pupils the opportunity to develop knowledge about different human activities and processes produced in nature that have an impact on the forms and patterns of the Earth’s surface”. Furthermore, the syllabus also states that instruction should focus on “the significance of, and distribution of water as well as the hydrological cycle.” (Swedish National Agency for Education 2011).

Textbooks are important aspects of instruction and part of educational reconstruction according to MER. Geography textbooks used in Swedish teacher education, are in general up to date with research. For example, Strahler and Strahler (Citation2013), describe the Gulf Stream as being affected by north large-scale atmospheric system (the North Atlantic oscillation) similar to the description by Berger (Citation2009). Furthermore, this textbook also describes the formation of deep-water currents similar to Rayner et al. (Citation2011). However, when investigating textbooks in year 4-6 middle school geography in Sweden, it becomes evident that ocean currents including the Gulf Stream are covered to a limited extent, often described only on a single page. Many of these textbooks contain a map of cold and warm ocean currents in the world and a brief description of mechanisms that set ocean water in motion such as winds, and density differences in the formation of deep water. In addition, these often describe that the Gulf Stream brings warm water and heat to northern Europe, with an example of how this affects humans, such as ice-free ports in Norway, enabling shipping of goods in wintertime. Some geography textbooks in year 4-6 hardly mention ocean currents at all or have reduced the description of the Gulf Stream to only a sentence in the glossary. The latter is problematic as educational research show that teaching tend to be governed by content in textbooks and earlier curricula (Molin and Grubbström Citation2013), although the Gulf Stream plays a key role for the climate, ecosystem and human activities in northern Europe, northern America and other parts of the world. In the grading instruction for teachers in the national test in geography year 6, students were expected to hold the following knowledge of the Gulf Stream for a pass (grade E).

Knowing that the Gulf Stream is an ocean current in the Atlantic Ocean.

Knowing how the Nordic region is affected by the Gulf Stream, either by relating to climate, nature or humans.

Previous research

Students’ understanding of ocean science, currents, and processes

Research in geoscience education shows that many students have problems understanding concepts such as continents and oceans in relation to plate tectonics. Marques and Thompson (Citation1997) found that students aged 16-17 assume that oceans are always deepest and continents always highest in the middle. Furthermore, research in marine science and oceanography education have identified several misconceptions about the oceans held by university students. Some of these are related to ocean currents such as: 1) ocean currents are caused by tides, 2) ocean currents in the northern and southern hemisphere move in the same direction, 3) the Gulf Stream is a river in the ocean (Feller Citation2007), although the Gulf Stream is more accurately described as a rim of the warm water lens rotating in the North Atlantic (Berger Citation2009). Similar problems have also been identified among young students. Guest, Lotze, and Wallace (Citation2015) concluded that students aged 12-18 have limited understanding of ocean science, in particular chemical and physical topics and Ballantyne (Citation2004) report that 10-11-year-old students have difficulties to understand concepts such as tides, currents, and waves. Similarly, Cummins and Snively (Citation2000) reported that students’ (aged 9-11 years) knowledge about ocean currents was very low.

Students’ understanding of natural phenomena and geographical concepts

Apart from research on students’ understanding of tropical cyclones by Lane and Coutts (Citation2012), studies that have investigated students’ understanding of natural phenomena have not primarily focused on understanding of these phenomena in relation to geographical concepts. One reason is that alternative conceptions are more difficult to identify in geography education due to the complex epistemology and ontology of the discipline, drawing on theories from physical and human geography as well as spatial science (Lane and Coutts Citation2015).

Spatial distribution, location, and scale

Lane and Coutts (Citation2012) show that students commonly described tropical cyclones as small-scale phenomena, like the size of a classroom and with a lifespan of no more than a few hours and many students mistook tropical cyclones for tornados. This was evident as they associated them with rotating tubes of air, such as in the movie “Twister”. This alternative conception was also supported by results showing that students link the distribution and location of these to foremost America, where tornados are frequent. Some of the alternative conceptions among students seemed difficult to change; although students were given satellite images showing real tropical cyclones they did not change conceptions of scale.

Interaction

Lane and Coutts (Citation2012) conclude that many students believe that fatalities of tropical cyclones are related to debris falling from the sky, or houses collapsing. Some students also described that a vacuum form in the eye of the cyclone (depleted of oxygen) or that everything freezes to ice in the eye, similar to the movie “The Day After Tomorrow”. Similar, few people have experienced a disaster in their life and may instead rely on the images displayed in disasters films when shaping their perceptions of risk (Haney, Havice, and Mitchell Citation2019). Previous research also shows that students hold a wide range of conceptions concerning how the ocean will respond to climate change. In the US, an interview study with 7th graders concerning their conceptions of global warming and climate change, shows that the majority of students believed that ocean levels will rise due to increasing precipitation and melting of polar ice, or decline due to increased evaporation. A smaller number of students believed that oceans would only become warmer or not change at all (Shepardson et al. Citation2009). In addition, Shepardson et al. (Citation2009) concluded that students mainly focused on the physical state of the ocean rather than how the weather/climate or life in the ocean will be affected by climate change. Thus, presently there is little research on how students understand the interaction between the ocean and the environment. However, an interview study of 4th-11th graders in the US by Brody and Koch (Citation1990) revealed that at least half of the students believed that coral reefs exist throughout the whole Northern Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, some students described that deep aquatic plants do not need light, and that the oceans are limitless resources with no political boundaries.

Methods and material

The empirical study is based on a thematic analysis of student responses in the Swedish national test in Geography for grade 6, complemented by focus groups interviews with students.

Sampling process

Written responses in the national test in geography

From the Swedish national test in geography year 2013, data were collected from a total of 134 students in the ages 12 to 13. This was completed with permission by the ethical review board in Sweden. As the study only involved students’ written responses, not including any personal data, the requirement for consent was waived by the ethical review board. Furthermore, in 2013 the national tests in the four social science subjects were dispersed randomly across all schools in Sweden for students in year 6, meaning that students were only tested in one of these subjects. Which test students in a particular school were given was announced to the teachers two weeks in advance. In 2013, the test in geography was taken by 23969 students, which represented approximately one quarter of all students in this age group. The purpose of the national test in geography was to support equal and fair assessment and grading in geography, as well as to generate data for analysis regarding to what extent knowledge requirements (grade criteria) in geography were fulfilled in a school, mandator (e.g., municipality) and at a national level. The social science teachers in each school administrated the tests, and were also responsible for grading them and reporting the results to the Swedish National Agency for Education/national test unit in geography. In 2013, the national test in geography contained 28 items related to four different geographical capabilities; sustainable development, knowledge and skills of maps, geographical relationships, and natural processes and landforms. All items in the test were intended to measure one of these capabilities and together cover the syllabus in geography year 4-6 (cf. Arrhenius, Lundholm, and Bladh Citation2021). One item focused on the Gulf Stream, and the questions in the assignment asked students to describe:

What is the Gulf Stream?

Where is the Gulf Stream located on the map?

How does the Gulf Stream affect climate, nature, and humans in the Nordic region?

A map was included in the assignment where the students were instructed to draw the route of the Gulf Stream ().

Students’ written answers to these questions and drawings in the map provide the basis for this study.

The Swedish National Agency for Education, in collaboration with the national test unit in geography, gathered results from a pre-selected amount of all completed tests, using a sampling procedure based on students’ birth date. This is done in order to conduct statistical analysis from the tests. The teachers administrating the test were instructed to report results online of students who were born on the 10th, 20th, and 30th of every month. Additionally, teachers were also instructed to send a copy of the complete paper test of students born on the 10th. In 2013, teachers reported the results from 1944 students, including 578 complete paper tests, to the Swedish National Agency for Education/the national test unit in geography. The data sampled for this study, known as the “large sample,” is taken from the 578 paper tests received. A randomized sampling procedure was undertaken to investigate students’ conceptions of the Gulf Stream on a national level. Every third response of the assignment on the Gulf Stream from these 578 complete paper tests was extracted until saturation was reached (134 responses), meaning that no additional themes and subthemes could be identified. Similar to the large sample, the characteristics of the smaller sample represented different schools and geographical areas in Sweden, different grades and were made up of approximately a 50/50 split between boys and girls (cf. Arrhenius, Lundholm, and Bladh Citation2021).

Interviews

With parental consent and permission by the ethical review board in Sweden, focus group interviews with 24 students aged 12-13 were conducted in 2017. The purpose with these interviews was to gain a deepened contextual understanding of students’ conceptions in the national test. The focus groups interviews were conducted with students of the same age as in the national test, at three schools with students of different socioeconomic background and in groups of 6-8. Before the focus groups interview started, students were instructed to complete three assignments from the test in 2013, where one of these was the assignment about the Gulf Stream. The students were given the same questions as in the assignment in the national test, and were also able to elaborate their answers. Importantly, during the interviews, the students were given follow-up questions and questions for clarification in relation to their responses to the questions (a, b and c) in the assignment. Gill et al. (Citation2008) suggests that focus group interviews are a suitable method for exploring possible explanations but also to clarify and challenge data collected by other methods. In addition, separate interviews with their teachers were conducted after the focus group interviews. These can be described as semi-structured (Brinkmann Citation2013), similar to the interviews with the students. The teachers were asked of their experience of teaching students aged 12-13 about the Gulf Stream as well as plausible explanations for students’ conceptions.

Analysis

Responses from the test-takers in 2013 were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) where the analysis focuses on contextual understanding of both latent and manifest content (Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas Citation2013). The responses concerning questions a) and b) in the assignment were analyzed using an inductive approach. However, concerning question c) in the assignment, the main themes were already given (climate, nature, humans), thus a deductive approach was initially used, complemented with an inductive approach to identify subthemes within these main themes (e.g., plants and animals within the theme of nature). Furthermore, the analysis of the three questions (a, b, c) focused on students’ alternative conceptions. However, some of these conceptions were more or less scientifically correct, but lacked important components and were therefore labeled partial scientific conceptions (cf. Arrhenius, Lundholm, and Bladh Citation2021).

Students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon

The first analysis explored students’ conceptions of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon (question a) by focusing on concepts in the written responses that were directly manifested in the text (e.g., current, ocean current) but also on latent content in the use of everyday words (e.g., stream, sea streams). An inductive approach was taken to identify major themes, as there was no previous research on students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream on which the analysis could draw on. The analysis concluded on three different themes; definition, location, and function.

Students’ conceptualizations of the Gulf Stream – location and distribution

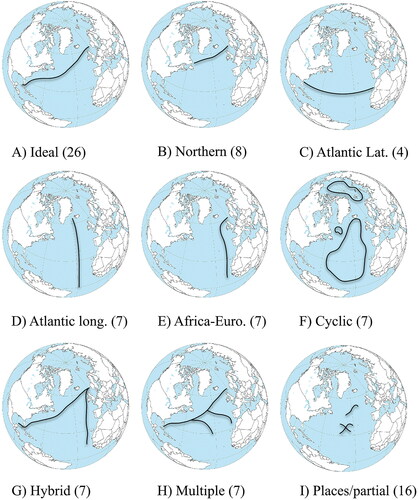

This analysis focused on students’ conceptualizations of the location and distribution of the Gulf Stream, represented by students’ conceptualization of the path (route) of the Gulf Stream (question b). An inductive approach was undertaken to identify major themes. The analysis concluded on nine main themes (e.g., ideal route, northern route, Atlantic latitudinal route), including several subthemes related to these main themes.

Students’ conceptualizations of the Gulf Stream – interaction

Finally, students’ conceptualizations of the interactions of the Gulf Stream were analyzed (question c), focusing on the main themes: Climate, Nature, Humans. The analysis investigated manifest content discussed by students in relation to these themes as well as latent content where students discussed other related concepts such as temperature and climate changes, plants and animals, and people. In the analysis, an inductive approach was taken to identify subthemes within these three main themes. The analysis concluded on five subthemes in relation to the main theme of climate (e.g., climate in general, seasons), three subthemes in relation to the main theme of nature (e.g., plants, animals), and three subthemes in relation to the main theme of humans (e.g., health and recreation, agriculture and trade).

Trustworthiness

By letting researchers with similar educational and professional backgrounds, code the same material and then compare results, high reliability is likely to be ensured (Drisko and Maschi Citation2015; Krippendorff Citation2004). The two researchers who were involved in the coding procedure have both taught geography at the high school level as well as at university level. Additionally, both have worked with the school geography curriculum at a national level. One of the researchers is a professor holding a PhD in geography and the other researcher a PhD student in geography education holding a licentiate degree in geography. The researchers have previously conducted research on alternative conceptions in geoscience and geography education using thematic analysis (cf. Arrhenius, Lundholm, and Bladh Citation2021). Discussions concerned deviant interpretations of some of the responses, for instance which theme a specific response belonged to concerning students’ conceptualization of the path of the Gulf Stream, and labels of subthemes within the main themes. This discussion led to validation, concluding that the main themes and subthemes were representative in describing students’ understanding.

Results

This section presents students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon and in relation to their geospatial conceptualizations, especially the geographical concepts of location, distribution and interaction. Interpretations of students’ conceptions by the authors are illustrated in and excerpts from students’ written responses are presented in the text and in .

Figure 2. The maps (A-I) show examples of the major themes of students’ conceptualizations of the path (route) of the Gulfstream.

Table 1. Students’ conceptions of the path of the Gulfstream (themes, subthemes).

Table 2. Students’ conceptions of how the Gulf Stream (GS) affects climate.

Table 3. Students’ conceptions of how the Gulf Stream (GS) affects nature.

Table 4. Students’ conceptions of how the Gulf Stream (GS) affects humans.

Students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon

National test

The analysis of the responses in the national test revealed three themes - (definition) of the Gulf Stream, the route (location) and ways it affects us (function). The majority of the students defined the Gulf Stream as a “current”, “warm current” or an “ocean current”, and a few students described the Gulf Stream as a “cold current” or just “water”. Concerning location, some students described the route in more detail, such as “from the Gulf of Mexico to Norway”, whilst other gave a more general description such as “a long current in the ocean”. These statements (question a) were often described in line with students’ drawings on the map in the assignment (question b), but sometimes not. Many students also described the way the Gulf Stream affects us by stating “the Gulf Stream brings heat to the Nordic region and Europe”. Also, combinations of these themes were found among the majority of the students. The most common ones included the themes of definition and location, or definition and function.

An example of definition and function: “It is a kind of current in the water which collects the heat and then it affects the climate here in the north.”

An example of definition and location: “The Gulf Stream is a stream that collects water from the south and transports the water up to the north.”

Focus group and interviews with teachers

Analysis of the focus group interviews showed that students discussed the three themes in a similar way as students in the national test. In addition, students were asked about their associations with the concept of currents, whereas some students explained they were thinking of electrical currents, a concept they had encountered in physics. However, most students explained they associated the concept with rapids in rivers, and to what they had watched in movies and TV-series.

Examples: “I am thinking about ocean currents, can go under water, like a stream. It was something like in a TV-series called Riverdale. It was a girl who got trapped under the ice and was transported downstream.” and “I watched a movie where turtles travelled with a current. The movie was called Finding Nemo.”

Students’ conceptualizations of the Gulf Stream – location and distribution

National test

The analysis of the responses in the national test revealed nine different ways of conceptualizing the path (route) of the Gulf Stream (see ).

The result showed that some of the identified main themes were linked to each other. In route A and B, the differences in students’ drawings were likely related to how they interpreted the map projection in the assignment. Although route D and E were drawn from different point of departure, it could be assumed students held a joint idea of water coming from a warm location and moving to a cold location. Furthermore, several subthemes were identified within the identified themes (see ). While most subthemes within a theme shared similarity in the way students drew the path of the Gulfstream (e.g., route A & B), other subthemes such as in route F, instead shared a similar attribute (ring-shaped). Finally, there were also responses where students did not provide an answer (blank) or could not be categorized. The latter consisted often of drawings showing a single dot, or faint undiscernibly pencil strokes on the map in the assignment.

Focus group and interviews with teachers

The statements of the students in the focus groups confirmed some of the links between the different themes identified in the national test, but also provided plausible explanations of students’ drawings of some of the other themes. Many students in the focus groups depicted the path of the Gulf Stream similar to the Ideal route (A), and some similar to the Northern route (B) (see, and ). When the students were asked why they depicted the path further to the north, they explained that the map in the assignment was turned/twisted in a way they had not seen in maps in school. This is illustrated by the following utterances:

“But this map, now I see it. Now when I think about it, I see it is kind of turned/twisted in a certain way, and that is why it should be there. One should have these flat maps, not the round globe.” and “I don’t know but it felt like the maps we have seen, then it felt like it was quite high up, not all the way down here.”

Concerning the Atlantic latitudinal route (C), one of the teachers proposed that students might have mixed up the map in the assignment with historic maps showing former trade routes. Although the students in the focus groups did not depict route C, they suggested that students in the national test might have assumed that the line on the map (showing 30 degrees north), represented the equator, a place where students generally believe there is lots of warm water. An example: “I think they connect to that as being the equator, which is there, and the equator is warm, therefore there has to be a warm stream there.” This idea was also supported by one of the teachers. Furthermore, some students in the focus groups depicted the Gulf Stream as the Atlantic longitudinal route (D), similar to students in the national test. When asked about their drawn route, they were not sure where the Gulf Stream starts from exactly, just that it brings warm water from the south. An example: “I am thinking it is kind of warm there (points to the south), and it is cold in the north.” Similar reasoning concerned the African-European route (E), although it was not depicted by the students in the focus groups. They suggested that students in the national test were thinking of Africa as a place where the warm water may originate. An example: “They may think it is warm here” (pointing to Africa on the map). Similar to route C and E, the Hybrid route (G), was not depicted among the students in the focus groups. However, one of the teachers had seen students draw the Cyclical routes (F) in the Atlantic Ocean before, but not in the Arctic region. In addition, one student proposed that students in the national tests were thinking that heat was exchanged, as they were drawing a circle in the Atlantic. An example: “They think in circles, as a fridge, like a reversed fridge.” Finally, the remaining routes (G-I) were not discussed with the students either in the focus groups or with their teachers, as these patterns had not yet been identified when the interviews were conducted.

Students’ conceptualizations of Gulf Stream – interaction

National test

Climate: Five different subthemes were identified among the written test responses, which contained both scientific and alternative conceptions (see ). The most common subtheme, Climate in general, contained students’ descriptions of the Nordic region being warmer due to the Gulf Stream. In another subtheme, many students described how the Baltic Sea and lakes in the Nordic region are warmer than usual due to the Gulf Stream, or described that no ice forms along the coast in Norway during the winter, due to the heat from the Gulf Stream. Many of the responses in these subthemes contained alternative conceptions, such as that climate has not changed at all despite the presence of the Gulf Stream or that the Gulf Stream is the cause of seasons in the Nordic region.

Nature: The two major subthemes identified were plants and animals, and a few students also discussed how soils are affected by the Gulf Stream (see ). Many students described that certain plants and animals can live in the Nordic region in general, and some students elaborated that it may be due to adaption to a warmer climate. These subthemes also contained some alternative conceptions such as some species of fish may get trapped in the current, or the Gulf Stream creates rainforests along its way. Students who depicted the Cyclical routes or the Atlantic latitudinal route of Gulf Stream, in particular, held many of these conceptions.

Humans: The major subthemes identified were health and recreation, agriculture and trade, and catastrophes (see ). The majority of the students related a warmer climate to better living conditions involving activities such as swimming in lakes in the summer, or being able to spend more time outdoors in general due to a warmer climate. The subtheme catastrophes included many alternative conceptions, the most common one was where students assumed that in the absence of the Gulf Stream people in the Nordic region would freeze to death.

Focus group and interviews with teachers

In the focus groups most of the students associated the term climate with temperature, but also with climate change. Furthermore, many students were worried about the climate changes and discussed what would happen if the Gulf Stream would change or disappear. Students were found to have difficulties understanding the problem of the Gulf Stream slowing down due to increased precipitation in the north Atlantic and increased discharge of fresh water from glaciers on Greenland. Thus, the notion of deep water forming in the Atlantic seemed unknown to the students and generated new questions such as “What, is it some kind of hole that the water is stored in?” Some students held alternative conceptions concerning effects of the heat exchange from the Gulf Stream and discussed whether the heat from the Gulf Stream could tan humans in the same way as UV-radiation from the sun, and considered this as problem if the Gulf Stream would disappear. Furthermore, the majority of the students in the focus groups associated the term nature with plants (mainly trees and forests), and animals. Some students discussed the consequences for plants and animals if the Gulf Stream was not present in terms of less fruit and animals suffering. Other students also stated that many plants and animals would not be able to live in the Nordic region in the absence of the Gulf Stream. Finally, the students in the focus groups described how the Gulf Stream affects humans in the Nordic region. Many of these descriptions were similar to responses in the national tests, for example that people can bath more in lakes and the sea, as the Gulf Stream makes the water warmer.

Discussion

Students’ understanding of the Gulf Stream as a geographical phenomenon

The majority of the students described and defined the Gulf Stream as a current, or a warm current, and location and function were often a part of their descriptions. Consistent with Lane and Coutts (Citation2012), our findings show that media (movies and TV-series) play a role in students’ conceptualization of natural phenomena. In particular the movie “Finding Nemo” seems to have influenced the ways students understand the Gulf Stream.

Students’ conceptualizations of the Gulf Stream – location and distribution

The route of the Gulf Stream was often described in a different manner than compared to what is currently known by science. In general, students’ descriptions of the route were based on their understanding of the physical aspects in relation to the geographical context, such as bringing warm water from where it is warm (e.g., the equator).

None of the students included locations where convection of deep water takes place in the Atlantic Ocean, or described the North-Atlantic current as the extension of the Gulf Stream to Europe. This may be a result of simplified models of ocean currents in textbooks in school, which may fail to show the true complexity, for example in flow patterns as described by Hays (Citation2017). Students who depicted the Gulf Stream according to route B were drawing the point of departure of the Gulf Stream more northerly than its actual path. This may have many reasons, but one explanation can be the frequent use of conformal maps (Mercator projection) in schools. Flat maps cannot contain all the qualities of the globe; they often contain distortions, such as areas with incorrect relative sizes or shapes, as well as distorted distances and angles. The Mercator projection distorts areas to an extreme degree, but also shapes to a less extent, for instance giving North America a widened girth on its northern extremities (Olson Citation2006). Although map projection is a complicated concept for high school students (Golledge, Marsh, and Battersby Citation2008), it is important knowledge for young student to acquire in order to understand maps from oblique angles (Liben and Downs Citation2003). When students are exposed to a map projection, such as the one used in the assignment, some of them may not compensate for the different location of the continents thus depicting the path of the Gulf Stream in the middle of the map and placing it further north than its actual path. Furthermore, a plausible explanation for the drawings of route C is that students were associating the path of the Gulf Stream with other maps, for example showing trade routes. As for drawings of Route D and E, it is plausible that the students did not know the specific route except that it originates from a warm place on earth, which students commonly associate with the equator. Finally, students’ drawings were also influenced by the framing of the assignment questions and the map projection, which highlights the relation between the Nordic region and the Atlantic Ocean with the Gulf Stream.

Students’ conceptualizations of the Gulf Stream – interaction

Climate: The results show that many students were aware that the Nordic region has a warmer climate than other areas at similar latitudes due to the presence of the Gulf Stream. Students also described that the Gulf Stream makes oceans warmer and increases evaporation, which is similar to findings by Shepardson et al. (Citation2009) as to how students believe climate change will affect the ocean in general. The results also show alternative conceptions concerning how the Gulf Stream interacts with climate, as some students seemed to assume that the Gulf Stream is the main cause of seasons in northern Europe. Other students also suggested that tides are caused by ocean currents (in this case the Gulf Stream), which is similar to findings by Feller (Citation2007). In addition, the students did not provide any explanations regarding the drivers of the Gulf Stream or the cause of its weakening. This may be a result of students having difficulties with understanding the scientific content underlying concepts such as ocean currents similar to findings by Ballantyne (Citation2004) and Guest, Lotze, and Wallace (Citation2015). Furthermore, some students also expressed a concern regarding how climate change will affect the Gulf Stream in the future, and many students stated that the Nordic region may become colder to some degree if the Gulf Stream weakens, which is more or less in line with current scientific predictions. Other students assumed that northern Europe will become as cold as the North Pole or northern Siberia, and these alternative conceptions may have been shaped by contemporary catastrophic movies and TV-series similar to findings by Lane and Coutts (Citation2012). Some of these conceptions may influence how students understand timescales in processes in ocean currents. For example, the movie “The Day After Tomorrow” have been criticized for presenting the alternative conception of the thermohaline circulation (THC) collapsing in days, which in reality would rather occur over several decades (Haney, Havice, and Mitchell Citation2019).

Nature: The students in the focus groups mainly discussed the concept of nature in terms of plants and animals and how these have adapted to the present climate due to the presence of the Gulf Stream. Some of students’ conceptions were similar to findings by Shepardson et al. (Citation2009) in the sense that the Gulf Stream is an agent which changes the climate (similar to humans) and that plants and animals will respond to that change. However, some alternative conceptions were closely related to the specific route of the Gulf Stream, for instance, some students drawing route C proposed that rainforests are growing along the Gulf Stream, which is similar to the findings by Brody and Koch (Citation1990). This alternative conception may be a result of students assuming that latitude 30 degrees north on the map in the assignment represented the equator. Some students describing route F also held conceptions of fish being trapped in a circular flow. To some extent this is accurate as species may be transported passively by currents in the ocean as described by Hays (Citation2017). On the other hand, currents do not form impregnable barriers that large animals cannot escape from, as some students described.

Humans: The majority of the students related the effects of the Gulf Stream on humans to their everyday experiences, such as bathing in lakes or walking outside in t-shirts during the summer. However, the Gulf Stream was also described as providing humans in Europe with better agriculture conditions, and making shipping easier in the Northern region due to less ice along the coast in the winter.

Limitations

The national test in Sweden is a unique piece of material as it contains students’ responses from a wide range of schools and geographical areas. As the study includes a representative sample of Swedish students within this age group, we believe that the results can be generalized to students in Sweden of similar age and therefore provide a solid ground for future intervention studies. A limitation of the study is related to time as four years had already passed after the national test was taken by the students in 2013 until the interviews were conducted in 2017. However, findings from the focus groups indicate similar problems in understanding the Gulf Stream as identified in the national test.

Implications for instruction

The results show that the students’ drawings of the path of the Gulf Stream were often related to how they believed the Gulf Stream interacts with climate, nature and humans. Consequently, students must be able to describe the path of Gulf Stream on a map in a correct manner, in order to draw relevant conclusions about this ocean current. The results are important for instruction in multiple ways. Firstly, we would like to stress that students’ geospatial conceptualization is best supported in situations when the path of the Gulf Stream is discussed together with geographical contextual information of the Gulf Stream, and with a focus on interaction in terms of effects on climate, humans, plants and animals. We also propose that instruction should identify and target students with low spatial ability and help them develop their map-based reasoning skills (Ishikawa Citation2016). According to Dunn (Citation2011) map quizzes have the potential to encourage and evaluate students’ understanding of concepts such as location. Secondly, many students were experiencing problems with understanding the map projection in the assignment. Therefore, we suggest instruction should focus on helping students achieving a basic understanding of the reference system (longitude and latitude), as a way for students to detect visually what type of map projection they are dealing with (Olson Citation2006). Finally, the results show that few students could explain the physical processes involved in the Gulf Stream and how climate change may change these. We suggest that instruction should include at least a basic introduction of the drivers that set water in motion in oceans, such as wind driven stress as well as processes involved in the formation of deep water. Instruction should also describe how climate (e.g., high, lows) and climate change (e.g., increased precipitation, melting ice sheets on Greenland) may affect the flow of the Gulf Stream in a short- and long-term perspective. In addition, using computer animations in instruction may support 12-13 year olds understanding of these processes, in particular as students’ main problem in geoscience is understanding concepts which they have not directly experienced (Cheek Citation2010). We believe, this would strengthen students’ knowledge of ocean and climate processes in general, as well as deepen their geographical understanding of how the Gulf Stream interacts with climate and nature (e.g., plants, animals) as well as human activity.

Future research

We encourage research which focuses on designing instruction that targets what has been reported here on students’ geospatial conceptualizations, map reasoning and processes. We believe it is important to conduct interventional design based research. For example, investigating how integrative geographical analysis could be further developed and in what way students understanding of processes in oceans currents can be improved by using computer animations in instruction. Thus, applying the final step described in the Model of Educational Reconstruction which concerns the design and evaluation of teaching and learning environments aiming at changing students’ alternative conceptions (Duit et al. Citation2012). Today, glaciers and ice sheets are rapidly melting, oceans are becoming warmer and the Gulf Stream is changing due to climate change. Further research on students’ understanding of these processes and instruction that can support conceptual change is thus of importance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers as well as the editors for their insightful and constructive comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mattias Arrhenius

Mattias Arrhenius is a PhD-student in Educational Science at the Department of Humanities and Social Science Education, Stockholm University, and teacher in geography and natural sciences at secondary high school. His research interests concern conceptual change and instruction in geography education.

Gabriel Bladh

Cecilia Lundholm is a professor in Educational Science with a specialization in teaching and learning in the social sciences at the Department of Humanities and Social Science Education, Stockholm University. Her research interests concern conceptual change and instruction in social science education, as well as climate, environmental and geography education, and the role of social science knowledge affecting pro environmental action and climate policy support.

Cecilia Lundholm

Gabriel Bladh is a professor in Social Science Education at Karlstad University. Current research focus is on subject specific education as a thematic field and especially geography education. He is appointed associate professor (docent) in Human Geography, and areas of specialization also include outdoor education, landscape research, theoretical perspectives connected to nature-society relations, and the history of geographical ideas.

References

- Arrhenius, M., C. Lundholm, and G. Bladh. 2021. Swedish 12-13-year old students’ conceptions of the causes and processes forming eskers and erratics. Journal of Geoscience Education 69 (1):13–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2020.1820838.

- Ballantyne, R. 2004. Young students’ conceptions of the marine environment and their role in the development of aquaria exhibits. GeoJournal 60 (2):159–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000033579.19277.ff.

- Berger, W. H. 2009. Ocean: Reflections on a century of exploration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brinkmann, S. 2013. Qualitative interviewing. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brody, M., and H. Koch. 1990. An assessment of 4th-, 8th-, and 11th- grade students´ knowledge related to marine science and natural resource issues. The Journal of Environmental Education 21 (2):16–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1990.9941927.

- Caesar, L., G. D. McCarthy, D. J. R. Thornalley, N. Cahill, and S. Rahmstorf. 2021. Current Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation weakest in last millennium. Nature Geoscience 14 (3):118–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00699-z.

- Caesar, L., S. Rahmstorf, A. Robinson, G. Feulner, and V. Saba. 2018. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556 (7700):191–209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0006-5.

- Casazza, T. L., and S. W. Ross. 2008. Fishes associated with pelagic Sargassum and open water lacking Sargassum in the Gulf Stream off North Carolina. Fishery Bulletin 106:363–348.

- Castellana, D., S. Baars, F. W. Wubs, and H. A. Dijkstra. 2019. Transition probabilities of noise-induced transitions of the Atlantic Ocean circulation. Scientific Reports 9 (1), 20284.

- Cheek, K. 2010. A summery and analysis of twenty-seven years of geoscience conception research. Journal of Geoscience Education 58 (3):122–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.5408/1.3544294.

- Cummins, G., and G. Snively. 2000. The effect of instruction on children´s knowledge of marine ecology, attitudes toward the ocean, and stances toward marine resource issues. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 5:305–24.

- Cushman-Roisin, B., and J. Beckers. 2011. Introduction to geophysical fluid dynamics: physical and numerical aspects. 2nd ed. Waltham, MA: Academic Press.

- Dong, S., M. O. Baringer, and G. J. Goni. 2019. Slowdown of the Gulf Stream 1993–2016. Scientific Reports 9 (1), 6672.

- Dove, J. 2016. Reasons for misconceptions in physical geography. Geography 101 (1):47–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2016.12093983.

- Drisko, J. W., and T. Maschi. 2015. Content analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Duit, R., H. Gropengiesser, U. Kattman, M. Komorek, and I. Parchmann. 2012. The model of educational reconstruction - A framework for improving teaching and learning science. In Science education research and practice in Europe: Retrospective and prospective, ed. D. Jorde and J. Dillon, 13–37. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

- Duit, R., and D. F. Treagust. 2003. Conceptual change: a powerful framework for improving science teaching and learning. International Journal of Science Education 25 (6):671–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690305016.

- Dunn, J. M. 2011. Location knowledge: Assessment, spatial thinking, and new national geography standards. Journal of Geography 110 (2):81–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2010.511243.

- Favier, T. T., and J. A. van der Schee. 2014. The effects of geography lessons with geospatial technologies on the development of high school students’ relational thinking. Computers & Education 76:225–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.004.

- Feller, R. J. 2007. 110 Misconceptions about the ocean. Oceanography 20 (4):170–3. doi: https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2007.22.

- Felzmann, D. 2017. Students´ conceptions of glaciers and ice ages: Applying the model of educational reconstruction to improve learning. Journal of Geoscience Education 65 (3):322–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.5408/16-158.1.

- Gill, P., K. Stewart, E. Treasure, and B. Chadwick. 2008. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal 204 (6):291–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192.

- Golledge, R. G., M. Marsh, and S. Battersby. 2008. Matching geospatial concepts with geographic educational needs. Geographical Research 46 (1):85–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00494.x.

- Goodchild, M. F. 2001. A geographer looks at spatial information theory. In Spatial Information Theory: Foundations of Geographic Information Science. Proceedings, International Conference, COSIT 2001, ed. D. R. Montello, 1–13, Morro Bay, CA, September. New York: Springer.

- Gregory, K. J., and J. Lewin. 2015. Making concepts more explicit for geomorphology. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 39 (6):711–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133315571208.

- Guest, H., H. Lotze, and D. Wallace. 2015. Youth and the sea: Ocean literacy in Nova Scotia, Canada. Marine Policy 58:98–107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.04.007.

- Haney, J., C. Havice, and J. T. Mitchell. 2019. Science or fiction? The persistence of disaster myths in Hollywood films. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 37 (3):286–305.

- Hays, G. C. 2017. Ocean currents and marine life. Current Biology : Cb 27 (11):R470–473. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.044.

- Huynh, N. T., and B. Sharpe. 2013. An assessment instrument to measure geospatial thinking expertise. Journal of Geography 112 (1):3–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2012.682227.

- Ishikawa, T. 2013. Geospatial thinking and spatial ability: An empirical examination of knowledge and reasoning in geographical science. The Professional Geographer 65 (4):636–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2012.724350.

- Ishikawa, T. 2016. Spatial thinking in geographic information science: Students geospatial conceptions, map-based reasoning, and spatial visualization ability. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (1):76–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1064342.

- Jackson, L. C., R. Kahana, T. Graham, M. A. Ringer, T. Woollings, J. V. Mecking, and R. A. Wood. 2015. Global and European climate impacts of a slowdown of the AMOC in a high resolution GCM. Climate Dynamics 45 (11–12):3299–318. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-015-2540-2.

- Jo, I. 2018. Spatial thinking in secondary geography: A summary of research findings and recommendations for future research. Boletim Paulista de Geografia 99:200–12.

- Kaspi, Y., and T. Schneider. 2011. Winter cold of eastern continental boundaries induced by warm ocean waters. Nature 471 (7340):621–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09924.

- King, C. 2010. An Analysis of Misconceptions in Science Textbooks: Earth science in England and Wales. International Journal of Science Education 32 (5):565–601. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902721681.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kuhlbrodt, T., A. Griesel, M. Montoya, A. Levermann, M. Hofmann, and S. Rahmstorf. 2007. On the driving processes of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Reviews of Geophysics 45 (2):1–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2004RG000166.

- Lambert, D. 2016. Geography. In The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, ed. D. Wyse, L. Hayward, and J. Pandya, 391–408. London: Sage.

- Lambert, D., and J. Morgan. 2010. Teaching geography 11-18: A conceptual approach. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Lane, R., J. Carter, and T. Bourke. 2019. Concepts, conceptualization, and conceptions in Geography. Journal of Geography 118 (1):11–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2018.1490804.

- Lane, R., and P. Coutts. 2012. Students’ alternative conceptions of tropical cyclone causes and processes. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 21 (3):205–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2012.698080.

- Lane, R., and P. Coutts. 2015. Working with students’ ideas in physical geography: A model of knowledge development and application. Geographical Education 28:27–40.

- Liben, L. S., and R. M. Downs. 2003. Investigating and facilitating children´s graphic, geographic, and spatial development: An illustration of Rodney R. Cooking´s legacy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 24 (6):663–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2003.09.008.

- Marques, L., and D. Thompson. 1997. Misconceptions and conceptual change concerning continental drift and plate tectonics among Portuguese students aged 16-17. Research in Science & Technological Education 15 (2):195–225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0263514970150206.

- Meinen, C. S., and D. S. Luther. 2016. Structure, transport, and vertical coherence of the Gulf Stream from the Straits of Florida to the Southeast Newfoundland Ridge. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 112:137–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2016.03.002.

- Mintzes, J. J., J. H. Wandersee, and J. D. Novak. 1997. Meaningful learning in science: The human constructivist perspective. In The educational psychology series. Handbook of academic learning: Construction of knowledge, ed. G. D. Phye, 405–47. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Molin, L., and A. Grubbström. 2013. Are teachers and students ready for the new middle school geography syllabus in Sweden? Traditions in geography teaching, current teacher practices, and student achievement. Norwegian Journal of Geography 67 (3):143–7.

- ÒHare, G. 2011. Updating our understanding of climate change in the North Atlantic: The role of global warming and the Gulf Stream. Geography 96 (1):5–15.

- Olson, J. M. 2006. Map projections and the visual detective: How to tell if a map is equal-area, conformal, or neither. Journal of Geography 105 (1):13–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340608978655.

- Palter, J. B. 2015. The role of the Gulf Stream in European climate. Annual Review of Marine Science 7:113–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015656.

- Rayner, D., J. J.-M. Hirschi, T. Kanzow, W. E. Johns, P. G. Wright, E. Frajka-Williams, H. L. Bryden, C. S. Meinen, M. O. Baringer, J. Marotzke, et al. 2011. Monitoring the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 58 (17–18):1744–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.10.056.

- Reinfried, S., U. Aeschbacher, P. M. Kienzler, and S. Tempelmann. 2015. The model of educational reconstruction – a powerful strategy to teach for conceptual development in physical geography: the case of water springs. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (3):237–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2015.1034459.

- Rhines, P. B., S. Hakkinen, and S. A. Josey. 2008. Is oceanic heat transport significant in the climate system? In Arctic-subarctic ocean fluxes, ed. R. R, Dickson, J. Meincke, and P. B, Rhines, 87–109. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer-Verlag.

- Riser, S. C., and M. S. Lozier. 2013. Rethinking the Gulf Stream. Scientific American 308 (2):50–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0213-50.

- Rossby, T., C. N. Flagg, K. Donohue, A. Sanchez-Franks, and J. Lillibridge. 2014. On the long-term stability of the Gulf Stream transport based on 20 years of direct measurements. Geophysical Research Letters 41 (1):114–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058636.

- Seager, R., D. S. Battisti, J. Yin, N. Gordon, N. Naik, A. C. Clement, and M. A. Cane. 2002. Is the Gulf Stream responsible for Europés mild winters? Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 128 (586):2563–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.01.128.

- Sexton, J. M. 2012. College students’ conceptions of the role of rivers in canyon formation. Journal of Geoscience Education 60 (2):168–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.5408/11-249.1.

- Shepardson, D. P., D. Niyogi, S. Choi, and U. Charusombat. 2009. Seventh grade students’ conceptions of global warming and climate change. Environmental Education Research 15 (5):549–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903114592.

- Skolverket [Swedish National Agency for Education]. 2011. Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet [The curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Stommel, H. 1965. The Gulf Stream: a physical and dynamical description. 2nd ed. Berkeley: California University Press.

- Strahler, A. H., and A. N. Strahler. 2013. Introducing physical geography. New York: John Wiley.

- Tran, L. U., D. L. Payne, and L. Whitley. 2010. Research on learning and teaching ocean and aquatic sciences. NMEA, Special report# 3, The Ocean Literacy Campaign, 22–6. Ocean Springs, MS.

- Vaismoradi, M., H. Turunen, and T. Bondas. 2013. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences 15 (3):398–405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048.

- Witherington, B. 2002. Ecology of neonate loggerhead turtles inhabiting lines of downwelling near a Gulf Stream front. Marine Biology 140 (4):843–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-001-0737-x.