Abstract

Using the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) datasets for geography, we explore relationships between geography achievement in the eighth grade and contextual variables related to the content and organization of the geography/social studies curriculum. Differences in student achievement are associated with grade-level variations in exposure to geography as well as the organization of social studies as discrete versus integrated subjects. The achievement gaps observed in this study underscore the need for research into the characteristics of geography curricula and the extent that variance in student outcomes is explained by differential access to geography in schools.

Introduction

Requirements for teaching geography in the United States vary considerably from state to state as well as within states (Brysch Citation2013; United States Government Accountability Office Citation2015). Zadrozny (Citation2017) noted that geography in lower secondary education is included as a strand, not a standard in most states and is just one of many social studies content knowledge and skills that are to be taught. As of 2018, the year of the most recent NAEP Geography assessment, only three states had separate standards tied to a specific geography course taught in grades 6-8. The remaining states had either a strand within social studies or a combination of both strand and geography course standards (Zadrozny Citation2018).

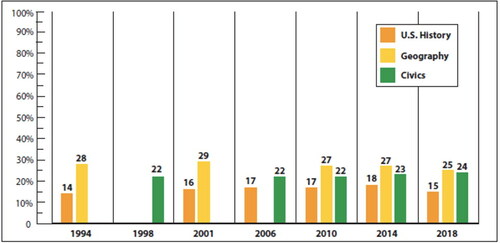

This heterogeneous educational landscape means geography is not always offered as a discrete stand-alone course, and if students do take a geography course it is most likely often an elective and may be the only geography course they take (Jones Citation2006). A Government Accountability Office report (GAO 2015) on the status of geography education showed that instruction time dedicated to English and math has heavily increased, while instruction in geography in many schools has been reduced or eliminated. Consequently, many eighth graders may not be acquiring the geographic knowledge, skills, and perspectives needed to gain a greater understanding of the world, prepare for future careers, and take informed action in areas of social welfare, public health, and the environment (Bednarz, Heffron and Huynh, Citation2013, p. 16). This is also true across the social studies, where there has been little in the way of national progress in improving student outcomes to proficient levels as measured by NAEP ().

Figure 1. Percentage of students at or above the NAEP Proficient level in Geography, Civics, and U.S. History (1994–2018). Source: Heafner (Citation2020).

Understanding the relationship between curriculum and achievement is critical for the development of appropriate interventions and reforms tailored to help students succeed. A related recommendation in National Geographic’s Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education calls for research that examines the components and characteristics of exemplary geography curricula (Bednarz, Heffron, and Huynh Citation2013). Yet research is also needed that views the geography curriculum from the lens of educational equity, for example by investigating the extent that achievement gaps are linked to systemic disparities in who has access to geography education in the nation’s schools.

This paper analyzes specific data points from the 2018 NAEP Geography assessment to explore the relationship between student achievement in the 8th grade and the content and organization of the geography curriculum in schools. We address the following research questions:

What is the relationship between geography achievement and the grades at which students learn geography?

What is the relationship between geography achievement and how the geography/social studies curriculum is organized (i.e., as stand-alone vs. integrated course subjects)?

What is the relationship between geography achievement and the types of geography topics and perspectives that are taught in the curriculum?

In the sections that follow, we present the methods used to explore statistical relationships between achievement and curriculum variables from the 2018 NAEP Geography datasets. Results are presented both in the aggregate and with NAEP achievement scores disaggregated by gender, race, and ethnicity. Taking our results into account, we conclude this article by offering recommendations for teacher professional development and further research into the relationships between achievement, differential access to geography in school curricula, and the nature of the geography subject matter students are exposed to in schools.

Methods

As a nationally representative assessment, NAEP offers a broad view of what students in the United States know and can do in geography. The most recent NAEP Geography assessment was administered in 2018 to 8th grade students. NAEP Geography also incorporates student and school questionnaires that provide additional information on students’ demographics and the content and organization of the geography/social studies curriculum.

We used the NAEP Data Explorer (NDE) to analyze relationships between geography achievement scores and variables representing geography/social studies curriculum content and organization (for a detailed background on the NDE, see Solem (in press)). To address our research questions, we focused on data from the 2018 NAEP Geography assessment. Statistical analyses performed with the NDE are based on the full sample of students and therefore support generalization to a national population of learners. An extended discussion about the NAEP assessment sampling design and methodology appears in the preceding article by Solem and colleagues.

The data reports for the present study are based on the following NDE specifications:

· Subject: Geography

· Grade: 8

· Year: 2018

· Scale: Composite (Space and Place, Environment and Society, Spatial Dynamics and Connections)

· Jurisdiction: National

· Statistic: Average Scale Score and Percentages

Generating data reports with these specifications enabled us to compare overall student scores on NAEP Geography in relation to NAEP curriculum variables related to grade level offerings of geography and different types of curriculum organization. We were also able to examine the proportions of students who learn geography prior to the 8th grade and who attend schools where the social studies curriculum is organized by discrete vs. integrated subjects. For each research question, comparisons between geography achievement scores were made using t-tests with an alpha level of 0.05. The preface for this issue offers additional details about NAEP scale scores and the geography assessment framework.

Results

Geography achievement is higher for students who reported taking a course in the 6th grade and 7th grade that included geography as a main focus or some geography content, compared with students who did not have a geography course in those grades (or didn’t remember) (). However, achievement was lower for students who took a course in 8th grade with a main focus on geography compared with eighth graders who did not take geography that year. The percentages of students taking a course with at least some geography content were higher in grades 6, 7, and 8 compared with students who did not learn geography at those grade levels.

Table 1. Average scale scores and percentages for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learned geography (reported by students), 2018.

When these data are disaggregated by race and ethnicity, two patterns emerge (). The first is a racial/ethnic gap in achievement in each grade, with lower scores for Black and Hispanic students compared with White students. Results were inconsistent for Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and multiracial students, but there were a few significant results indicating lower scores compared with White students.

Table 2. Average scale scores and percentages for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learned geography (reported by students), disaggregated by student race/ethnicity, 2018.

The second pattern is an achievement gap related to gender. Scores for female students are lower than the scores for male students (). Female students who took “a class that included some” geographical focus in the 6th, 7th, and 8th grades consistently had lower scores compared with male students.

Table 3. Average scale scores and percentages for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learned geography (reported by students), disaggregated by student gender, 2018.

The NAEP program also collects school-reported information about when students learn geography. Geography achievement is higher for students attending schools where students study geography in 5th and 6th grades (). A little over a third of schools provide geography instruction in grades 6 and 7, whereas 14 percent of schools offer geography instruction in grade 8 and only four percent of schools provide geography instruction in 5th grade.

Table 4. Average scale scores for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learn geography (reported by schools), 2018.

When the achievement data are disaggregated, racial and ethnic achievement gaps are observed once again (). For the most part, there are no differences in the scores between male and female students associated with the grades in which students learn geography ().

Table 5. Average scale scores for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learn geography (reported by schools), disaggregated by student race/ethnicity, 2018.

Table 6. Average scale scores for grade 8 geography, by grade in which students learn geography (reported by schools), disaggregated by student gender, 2018.

There are also significant differences in geography achievement associated with the way the social studies curriculum is organized. Compared with schools where social studies courses are available as discrete subjects, geography achievement is lower for students who attend schools where social studies subjects are fully integrated in the curriculum (). However, when the achievement data are disaggregated, the higher level of geography achievement associated with schools offering discrete social studies subjects is only observed for White students (). Overall, most eighth graders attend schools where the social studies curriculum includes a mix of discrete and integrated courses.

Table 7. Average scale scores and percentages for grade 8 geography, by how social studies is organized (reported by teachers), 2018.

Table 8. Average scale scores for grade 8 geography, by how social studies is organized reported by teachers), disaggregated by race/ethnicity, 2018.

NAEP background questionnaires also gather information on the topics covered in the social studies curriculum. Curriculum coverage variables have changed in NAEP assessments since 1994. In 2018, students were asked to indicate how much they studied the following topics in social studies this year:

The use of physical or digital maps (e.g., a road map, MapQuest, or Google Maps) and globes;

Natural resources (e.g., oil, forests, or water);

Countries and cultures;

Environmental issues (e.g., pollution, recycling, climate change, or genetically modified food).

Compared with students who responded “not at all” to these questions, geography achievement is generally lower for students who reported having studied these topics ().

Table 9. Average scale scores for grade 8 geography, by studying subjects in social studies (reported by students), 2018.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that geography achievement in the 8th grade can be improved by providing opportunities for students to take geography courses in earlier grades. Students who study geography in earlier grades, such as 5th and 6th grade, apparently acquire a foundation of knowledge that benefits them once they are assessed in the 8th grade. This result further suggests that when students do not get access to geography at an early age they fall behind their peers in knowledge and skills. Given the achievement gaps observed in this study, future research using restricted data from NAEP should investigate the extent that these gaps are associated with students having differential access to geography curricula in lower secondary education.

We observed higher levels of geography achievement at schools where the social studies curriculum is organized as discrete subjects. Although these results may compel geographers to recommend a wholesale nationwide expansion of geographic learning opportunities in the years of schooling leading up to eighth grade, this is probably an unlikely prospect in most states. As Downs notes (2016, p. 78):

While geographers may believe systemic change is necessary, it cannot be our realistic nor our achievable goal. Requests that geography become a stand-alone subject, offered at most grades, taught by trained teachers (and supported by the latest equipment) is a pipe dream beyond our reach, at least in the USA. That dream would require systemic change because the K–12 curriculum is a highly conservative and fiercely contested zero-sum game. Geography’s gain would be another discipline’s loss.

If Downs is correct in arguing against thinking about the geography curriculum in terms of the quantity of grade-level offerings, then what else might be done to improve student outcomes and close the racial, gendered, and socioeconomic achievement gaps identified in the preceding study by Solem and colleagues? Insofar as the curriculum is concerned, the results of our study suggest a need to focus on the quality of the geography subject matter in schools from the perspective of different groups of students.

Recall our finding that only White students appeared to benefit from studying geography in a curriculum organized by discrete subjects, and that boys outperformed girls who reported taking some geography courses. Why would this be the case? Is there something about the present nature of school geography that appeals primarily to White and male students, which may motivate and interest them to a greater degree than their female, Black, and Hispanic peers?

Although NAEP offers extensive data to conduct empirical research in geography education, deeper analysis of the curriculum content variables from the NAEP Geography assessment is unlikely to provide answers to these questions. This is evident in the results of our study: when asked about various course topics, such as physical maps, environmental issues, natural resources, or countries and cultures, students who said they studied those topics performed worse on the NAEP assessment.

Because NAEP does not capture the local specificity of curriculum content, we cannot determine exactly what geography topics and perspectives are taught in different schools and how this content is perceived by different groups of students. This introduces a need for research into the nature of the subject matter in geography curricula, the ways teachers and textbooks convey the subject, and the degree to which geography curricula are inclusive of student geographies.

The concern we raise here is not new. It echoes an observation about geography education made long ago by Janice Monk and her colleagues associated with NCGE’s Finding a Way project. According to Monk (Citation1997, p. 7):

"Finding A Way" is an in-service teacher education project that is being carried out under the sponsorship of the National Council for Geographic Education in the United States. It aims to help teachers stimulate interest and achievement in geography among girls of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The effort was initiated in 1991 by a Task Force within the National Council for Geographic Education. The Task Force was made up of a small group of women geographers who had several concerns. We saw that in the significant expansion of geographic education that began to take place in the mid 1980s in the United States, gender and multicultural issues were virtually invisible, despite the substantial amount of research and writing in education and in university geography on these themes since the 1970s. In this respect geographic education lacked the innovations that had been appearing in history, social studies, and literature teaching since the 1970s.

The Finding a Way initiative received funding support from the National Science Foundation following a primary research study in ethnically diverse classrooms in Florida and Alabama. That work yielded some findings that we feel resonate with the results of the NAEP analyses reported in this issue of the Journal of Geography. Specifically (Monk Citation1997, p. 8):

by Grade 9, minority boys were outperforming minority girls, though gender differences were not pronounced among White students;

that attitudinal differences were notable by school and grade level;

that among higher-achieving students, boys were more likely to describe the discipline as ‘fun,' ‘easy,' ‘cool,‘ 'exciting,' and ‘interesting,' and girls to see it as ‘boring,' and ‘stupid;'

that girls were more likely to describe geography by the content it covers than to identify with it affectively;

that boys had a wider range of ideas about careers associated with geography than girls did.

As an attempt to foster racial and gender equity in geography classrooms, the Finding a Way project published a set of 27 learning modules on the geography of diversity with a major emphasis on incorporating the voices of women, children, and other underrepresented groups into the instructional content. Module topics included the changing roles of women over the life course; white privilege; child labor in the global economy; contested neighborhoods; everyday geographies of children; environmental social justice; impacts of boy preference in less-developed countries; gender, place, and identity; gender in the landscape; women in the international division of labor; and women and social change movements (Monk et al. Citation2000).

Finding a Way remains a rather unique entity in the corpus of geography education curriculum initiatives. It is an example of what a geography curriculum might look like when it originates in a cultural perspective that accounts for gender, race, ethnicity, and other student characteristics and experiences.

Moving forward, we believe geographers would be well served by conducting local experiments in curriculum and instruction that acknowledge the increasing expectations of teachers to practice culturally responsive instruction for a rapidly diversifying student body (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2020). Inevitably, it is the responsibility of teachers to engage in the process of selecting and contextualizing disciplinary subject matter for students (Null Citation2017). Critical educational theorists such as Lisa Delpit (Citation1988) argue that a traditional focus on content knowledge, such as the notion of ‘cultural literacy’ popularized in the work of E.D. Hirsch (Citation1983, Citation1987), gives little or no regard to the socioeconomic and demographic diversity of learners in school classroom environments. This unequal power relationship tends to marginalize girls, minorities, LGBTQ + students, and others whose contexts are not considered or recognized in curricula, thus contributing to negative experiences with subject matter and education more broadly. Consider this argument in the context of research examining achievement gaps on the NAEP US History assessment (Fitchett, Heafner, and Lambert Citation2017, p. 18):

Research suggests that the official canon, with an emphasis on White males, is not representative of the diverse population of U.S. schools (Brown Citation2011; Cornbleth and Waugh Citation1995). Lacking historical positionality beyond the marginalized or the victim, non-White students are more likely to look upon such a narrative with scepticism and dissonance (Chikkatur Citation2013; Epstein Citation2009; VanSledright Citation1998). Consequently, they find learning history/social studies boring, inversely affecting their motivation to learn historical material (Stodolsky, Salk, and Glaessner Citation1991; Tanaka and Murayama Citation2014).

In this light, we recommend for geographers to revisit prevailing assumptions about what subject matter should be taught in schools. Geographers need to discuss openly and critically the disciplinary perspectives that inform the design and development of future geography curricula and standards. Cultural geographers, especially, should assume a greater role in this process. To do this, a greater emphasis needs to be put on professional development to ensure K-12 educators are aware and equipped with the best knowledge and practices to implement in the classroom. Examples of this include project based-learning and diverse learning opportunities that are specific to geography content and student contexts.

References

- Bednarz, S.W., Heffron, S., & Huynh, N.T. (Eds.). 2013. A road map for 21st century geography education: Geography education research (A report from the Geography Education Research Committee of the Road Map for 21st Century Geography Education Project). Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers.

- Brown, K. D. 2011. Breaking the cylce of Sispyhus: Social education and the acquisition of critical sociocultural knowledge about race and racism in the United States. The Social Studies 102 (6):249–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2011.563726.

- Brysch, C. 2013. Status of Geography Education in the United States. National Geographic Society Education Foundation. https://gato-docs.its.txstate.edu/jcr:42d98ff7-42d2-418c-b14a-55f288f9d99c/State_of_Geography_Report.pdf

- Chikkatur, A. 2013. Teaching and learning African American history in a multicultural classroom. Theory & Research in Social Education 41 (4):514–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2013.838740.

- Cornbleth, C., and D. Waugh. 1995. The great speckled bird: Multicultural politics and education policymaking. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Delpit, L. 1988. The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review 58 (3):280–99. doi: https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.3.c43481778r528qw4.

- Epstein, T. 2009. Interpreting national history. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fitchett, P. G., T. L. Heafner, and R. G. Lambert. 2017. An analysis of predictors of history content knowledge: Implications for policy and practice. Education Policy Analysis Archives 25(:65. doi: https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.2761.

- Heafner, T. 2020. The sky is not falling, but we need to take action: A Review of the results of the 2018 8th-grade social studies assessments. Social Education. 84(4), p. 25–260. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1268269

- Hirsch, E. D. Jr, 1987. Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

- Hirsch, E. D. Jr., 1983. Cultural literacy. The American Scholar 52 (2):159–69.

- Jones, M. C. 2006. High Stakes Teaching: The First Course in Geography. Journal of Geography 105 (2):87–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340608978665.

- Monk, J. 1997. Finding a Way. New Zealand Journal of Geography 104 (1):7–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0028-8292.1997.tb00016.x.

- Monk, J., R. Sanders, P. K. Smith, J. Tuason, and P. Wridt. 2000. Finding a Way: A program to enhance gender equity in the K-12 classroom. Women's Studies Quarterly. 28 (3/4): 177–181.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Changing expectations for the K-12 Teacher workforce: policies, preservice education, professional development, and the workplace. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/25603.

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2018. National assessment of educational progress (NAEP), geography assessment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement. https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/geography/

- Null, W. 2017. Curriculum: From theory to practice (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Solem, M. in press. The NAEP Data Explorer: Digging deeper into K-12 geography achievement and why it matters., The Geography Teacher. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19338341.2021.1895864.

- Stodolsky, S. S., S. Salk, and B. Glaessner. 1991. Student views about learning math and social studies. American Educational Research Journal 28 (1):89–116. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312028001089.

- Tanaka, A., and K. Murayama. 2014. Within-person analyses of situational interest and boredom: Interactions between task-specific perceptions and achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology 106 (4):1122–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036659.

- United States Government Accountability Office. 2015. K-12 Education Most Eighth Grade Students Are Not Proficient in Geography. Retrieved September 9, 2020 from https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-7

- VanSledright, B. 1998. On the importance of historical positionality to thinking about and teaching history. International Journal of Social Education 12 (2):1–18.

- Zadrozny, J. 2017. Social Studies and Geography Survey of Middle and High Schools. San Marcos, TX: Grosvenor Center for Geographic Education.

- Zadrozny, J. 2018. An Analysis of the Alignment between National and State Geography Standards. Unpublished doctoral diss. Texas State University.