ABSTRACT

Attitudes toward Muslims are at the core of addressing the anti-Muslim environments Muslims encounter in college and society writ large. Using longitudinal data, this study shows that colleges can spur the development of appreciative attitudes toward Muslims by non-Muslim students when they engage in two or more informal or formal social engagements across religious and spiritual identity differences. Institutional campus culture is also meaningfully connected to Muslim appreciation. Implications for research, policy, and practice are discussed.

In the United States, Muslims experience Islamophobia and anti-Muslim prejudice in their day-to-day life and routinely encounter conditions that are contentious, hostile, and dangerous (Pew Research Center [PRC], Citation2018). Muslims face marginalization driven by misinformation and prejudice coupled with social and political movements that pivot on Christian privilege to strengthen the hold of Christianity on American society and summarily dismiss other religious traditions (Edwards, Citation2017, Citation2018a). Christian nationalist movements foreground conservative Christian epistemologies while demonizing and dismissing minoritized religions like Islam as legitimate expressions of American identity (Morey et al., Citation2019; Whitehead & Perry, Citation2020). Muslims are frequently dehumanized by and in oppressive systems. Therefore, combating Islamophobia and fostering Muslim appreciation is a continued topic of national importance.

College campuses have been shown repeatedly to be unwelcoming to Muslim students in part due to the structural challenges (e.g., availability of prayer spaces or halal food) and in part due to the hostility, insensitivity, and Islamophobia they encounter on campus (Ahmadi et al., Citation2019; Barakat, Citation2018; Cole et al., Citation2020; Garrod & Kilkenny, Citation2014). Disrupting anti-Muslim attitudes is complicated. Some have demonstrated that providing non-Muslims with accurate information about Muslims and Islam helps negate prejudicial attitudes (Williamson, Citation2020). Others have asserted that attitudes toward Muslims are not only motivated by psychological perceptions of difference but by systemic structures that perpetuate the image of Muslims as outsiders (Gerteis et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2020). Although interfaith engagement in the collegiate environment is positively related to appreciative attitudes toward Muslims (Rockenbach, Mayhew, Bowman, et al., Citation2017; Shaheen, Dahl, et al., Citation2022), it remains unclear whether the college experience meaningfully combats Islamophobic attitudes in students across social identities in the long run. By using latent growth modeling from data collected at three timepoints and capturing the entirety of the college experience, we answer the following questions:

Do non-Muslim students increase in their appreciation of Muslims during their collegiate experience?

What environmental factors (conditions, contexts, practices, and engagements) contribute to change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims across four years of college-going?

How are student identities connected to these change trajectories?

Conceptual framework

The study is grounded in the Interfaith Learning and Development model (ILD), a “theory in practice” (Mayhew & Rockenbach, Citation2021, p. 1) that describes how students grow to honor differences across religious, secular, and spiritual (RSS) narratives and specifies development in four domains: appreciative knowledge toward religious and non-religious groups, self-authored worldview commitment, pluralism, and appreciative attitudes toward RSS diversity. A detailed explanation of the first three domains can be found in Mayhew and Rockenbach’s (Citation2021) work. This study is focused on one specific outcome: Appreciative attitudes toward Muslims. The focal outcome of Muslim appreciation is concerned with not only how individuals feel about people of different worldviews but is attuned to the “nuanced impressions that students have of specific groups” (p. 4). Appreciative attitudes encompass students’ perceptions of the positive contributions that a group makes to society, how ethical the people in a group are perceived, perceptions of commonality with members of that group, and positive regard toward that group.

The ILD takes an ecological approach to conceptualizing the collegiate environment by defining the environment in terms of nested spheres of influence (see ). At the center are interfaith experiences that occur within the collegiate environment. These engagements can be formal, informal, academic, or social. Interfaith engagement occurs within a particular disciplinary context operationalized as the college major, and is included to account for its influence on student learning (see Bryant & Astin, Citation2008). The relational context encompasses student interactions and captures both productive (e.g., provocative, supportive) and unproductive interactions (e.g., coercive, discriminatory). The institutional context includes conditions (e.g., selectivity, control), culture, climate, and organizational behaviors (e.g., spaces for interfaith engagement). These contexts encompass and influence every activity that occurs within an institution. The institution is, of course, situated within a larger national context that shapes the college environment and experiences therein at a particular time. This elaborate conceptualization of the environment encompasses not only individual student behaviors but the larger contexts in which students live, study, and interact.

Figure 1. The Interfaith Learning and Development Framework (Mayhew & Rockenbach, Citation2021).

Importantly, the ILD is attuned to the role of student characteristics in influencing the college environment and outcomes. Such characteristics include pre-college interfaith engagement and exposure to religious differences and student demographics such as race, religion, sexual orientation, and generation status, all of which interface with collegiate contexts to shape interfaith learning and development. The statistical analysis conducted for this study focused on the institutional context, relational context, disciplinary context, and engagement behaviors, as well as on the role of student characteristics.

Literature review

To situate our study, first, we review data and literature about Muslims in the U.S. with a focus on experiences and perceptions of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim attitudes. Then, we address the complexities of the Muslim identity, specifically its intersections with race and nationality, and the roles of racism, nativism, and colonialism in perpetuating Islamophobic attitudes. Finally, we turn to changes in diversity attitudes that occur in the college environment to address areas where our research makes significant contributions.

Experiences of Muslims in the United States

Islamophobia and anti-Muslim attitudes have been documented as fixtures in the lives of Muslims. Islamophobia is “the unfounded hostility toward Islam” and the consequences of “unfair discrimination against Muslim individuals and communities and to the exclusion of Muslims from mainstream political and social affairs” (Runnymede, Citation1997, p. 4). National data suggest that more than half of U.S. Muslims experience prejudice, discrimination, or other manifestations of Islamophobia (PRC, Citation2018). Describing the experiences of Muslims after the 9/11 attacks and the 2016 presidential elections, Lean (Citation2019) writes, “[Muslims”] daily lives became increasingly complicated. Going to work or school, a quotidian journey became, in some cases, a risk. Where their religious identity was obvious … the possibility of confrontation and backlash was palpable” (p. 37). Muslims, in short, navigate a hostile and volatile national climate that affects every aspect of their lives.

Similarly, college campuses have been shown to be hostile environments for Muslim students (e.g., Ahmadi et al., Citation2019; Barakat, Citation2018; Cole & Ahmadi, Citation2010; Garrod & Kilkenny, Citation2014). Most recently, Cole et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated how Muslim students experience insensitivity, coercion, and discrimination at colleges and universities, especially those that do not prioritize interfaith engagement. Furthermore, the narratives of Muslim women in Yousafzia’s (Citation2020) study confirmed earlier assertions that Muslims on campus are hyper-visible, subject to stereotyping, and are called to represent their entire religion. Both the academic and social environments present Muslim students with chilly exchanges that engender the sense of alienation they experience and perpetuate Islamophobic attitudes from their peers (Garrod & Kilkenny, Citation2014). Given what we know about Muslims and Muslim students, it is imperative that we interrogate attitudes toward Muslims to graduate college students who appreciate and value the Muslim community, and who are ready to confront Islamophobia. A discussion of the attitudes toward Muslims requires accounting for the intersection of multiple systems of marginalization, which we explore next.

The complexity of the Muslim identity

The Muslim identity encompasses all aspects of a person’s being. Islam tends to be a hyper-visible identity because of the outward displays of Islam (e.g., hijabs) that often lead to feelings of hyper-visibility. One cannot talk about Islam without addressing dimensions of race and ethnicity, as Islam is increasingly becoming racialized, especially in the way Islam is perceived (Dana et al., Citation2017; Karaman & Christian, Citation2020). Similarly, one cannot talk about Islam without talking about inter-national attitudes, as many conflate being Muslim with being Arab or Middle Eastern (Abu Rabia, Citation2017; Shammas, Citation2017). Muslims come from all races and ethnic origins, and they navigate the world through the lenses of these identities. Thus, Islamophobia is deeply connected to other forms of social prejudice, inequality, and -isms, namely racism, nativism, and sexism.

The agenda of the Trump presidential administration is perhaps the clearest, most recent example of the interplay between Islamophobia and racism. Trump was able to “interweave Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment into a seamless tapestry of threats that resonated with and amplified existing nativist sentiments” (Gottschalk, Citation2019, p. 47). The result was fiery anti-Muslim rhetoric that was reflected in laws and policies (e.g., travel bans imposed by executive orders; Gerteis et al., Citation2020; Rana et al., Citation2020) and the explicit Islamophobia it induced during Trump’s tenure. The discussion of the appreciation of Muslims is interlocked with other forms of oppression and systems of marginalization. Advancing equity and inclusion requires understanding worldviews as nuanced, diverse, embedded in culture, and implicated in power and marginalization. This motivated us to ask research questions that specifically address the impact of different social identities.

Interfaith engagement and attitudinal changes in college

Attending a higher education institution has been associated with an increased appreciation for diversity and for marginalized groups. There is evidence that college motivates a profound change in attitudes for some students, but not all, and more importantly, not toward all types of difference (Mayhew et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the question of whether colleges and universities are fulfilling their promises of educating responsible, justice-minded students, remains relevant. The utility of the college experience lies in the many connected spheres of the college environment that bring people together (Hurtado et al., Citation2012), where students’ contact with those who are different from them challenges attitudes and enhances positive perceptions (Allport, Citation1954; Hurtado et al., Citation2012; Ross, Citation2014). When it comes to religious, secular, and spiritual (RSS) diversity, there has been a growing interfaith movement in higher education.

Educators have engaged in interfaith work as “a response and remembering of the role of faith in the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness” (Carter et al., Citation2020, p. 29). Within the academic research sphere, Mayhew and Rockenbach (Citation2021) presented the ILD, which was shown to be useful for understanding the conditions and practices most conducive to positive interfaith outcomes (e.g., Mayhew et al., Citation2020; Rockenbach et al., Citation2015; Rockenbach, Lo, et al., Citation2017; Rockenbach, Mayhew, Correia-Harker, et al., Citation2017). Organizations such as Interfaith America (formerly Interfaith Youth Core) have helped bring more interfaith engagement to educational spaces (Interfaith America, Citationn.d.) with a focus on developing appreciative knowledge, meaningful relationships, and positive attitudes across RSS differences (Carter et al., Citation2020). But which approaches increase appreciation of Muslims in particular?

Research suggests that appreciation of Muslims comes with informal social interactions, especially those that provoke meaningful challenges of perceptions and attitudes (Garner & Selod, Citation2015; Rockenbach, Mayhew, Bowman, et al., Citation2017). When students interact meaningfully, they come to understand and appreciate one another. Some, however, assert that interfaith engagement without a social justice orientation is not enough (Edwards, Citation2018b) and call for “a critical interfaith praxis” that “acknowledges how systems of oppression impact educational structures, practices, and dominant narratives and aims to reestablish cultural ways of knowing to foster self-determination and authentically engage in social justice projects” (Carter et al., Citation2020, p. 29). With regard to Muslims and Islam, researchers have grappled with the intersections of identity marginalization (Shaheen, Citation2020) and revealed the intricacies of navigating social pressure that dictates multiple identity performances within and outside higher education (Bodine Al-Sharif & Zadeh, Citation2020). The experiences of Muslims are shaped both by the interpersonal micro-level interactions and the systematic macro-level climate and culture.

This study builds on previous efforts in higher education research to understand how college can enhance attitudes toward Muslims. In Rockenbach, Mayhew, Bowman et al. (Citation2017), the authors used cross-sectional data to show that a positive campus climate is associated with better attitudes and vice versa and that students who engage in interfaith activities are more likely to show appreciation toward Muslims. The cross-sectional analysis did not allow for accounting for pre-college attitudes or changes over time. This limitation was addressed by Shaheen, Dahl et al. (Citation2022), who surveyed students at the beginning and at the end of their first year in college. Similar findings regarding campus climate were found, and the longitudinal nature of the data allowed the authors to confidently say that the positive changes in attitudes were related to first-year experiences. In addition, Shaheen, Dahl et al. (Citation2022) distinguished between formal interfaith engagement (e.g., organized interfaith panel) and informal engagement (e.g., studying with someone of a different worldview). More specifically, the authors demonstrated that at least two formal engagements were needed for development to occur, whereas one informal engagement was sufficient to spur development in appreciative attitudes. A question that remained was whether development continues beyond the first year in college and what educators can do to support long-term changes in attitudes. Before turning to how this study builds on these previous works, we will take the time to explicate our positionality and connection to the research.

Researchers’ positionality

The authors of this work and the larger project represent multiple religious, spiritual, and secular worldviews. We share a commitment to fostering productive engagement across identity differences and a recognition of the positive impact such engagement has on individuals and societies. We engage in this research with a common understanding that supporting students’ growth from tolerance to appreciation is a key function of higher education institutions. We bring a wide range of methodological expertise and various experiences in data analysis, all of which inform how we approach research analysis and interpretation. Rather than listing our individual social identities as a declaration of positionality, we choose to focus on the connection of the lead author to this manuscript.

The lead author is a queer Muslim whose relationship with Islam has evolved over the years to become a salient identity as a means of resisting hegemonic structures that influence Islam and its image in society. He recognizes Islamophobia, along with other forms of prejudice, as social realities that can be mitigated and addressed through intentional educational practices. He emphasizes the potential and duty of higher education institutions to operate as agents of positive change. He engages in this work that interrogates attitudes toward Muslims with a unique understanding that comes from his identities and experiences in higher education and a dedication to uplifting the place of marginalized religious communities within a predominately Christian culture.

Methods

Data source

Data were collected as part of the Interfaith Diversity Experiences and Attitudes Longitudinal Survey (IDEALS). IDEALS included a nationally representative sample of students attending 122 colleges and universities across the United States, which were stratified by institution type, geographic region, selectivity, and affiliation (e.g., public, religiously affiliated, private nonsectarian). The survey was administered to students at three different timepoints: The start of students’ first year of college (Summer or Fall of 2015), the end of students’ first year of college (Spring or Fall of 2016), and the end of students’ fourth year of college (Spring of 2019). At the first timepoint, 20436 students from 122 institutions responded. At the second timepoint, the response rate was 43.0%, with 122 institutions represented; and at the third timepoint, the response rate was 36.0%, with 118 institutions represented.

Analytic sample

We focused our study on a subset of students who responded to the IDEALS survey for at least two of the three timepoints (N = 9,470 students), as two data points offered enough information from which to model trends in students’ appreciative attitudes over time (in conjunction with the use of full information maximum likelihood (FIML) — a robust approach to handling missing data in structural equation modeling). We further reduced the analytic sample to include only students who did not identify as Muslim at the first timepoint (N = 9,270 students) to understand how non-Muslim students develop an appreciation for their Muslim peers. The resulting subset of 9,270 students comprised the analytic sample for the current study.

Measures

Appreciative attitudes toward Muslims

At each of the three timepoints of data collection, the IDEALS instrument measured students’ appreciative attitudes toward Muslims using four items: (1) In general, people in this group make positive contributions to society; (2) In general, individuals in this group are ethical people; (3) I have things in common with people in this group; (4) In general, I have a positive attitude toward people in this group. Students responded by noting their level of agreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Disagree strongly; 2 = Disagree somewhat; 3 = Neither agree nor disagree; 4 = Agree somewhat; 5 = Agree strongly). The construct comprised of those four items was used as the focal outcome in our analyses, resulting in reliable measurement for the analytic sample of non-Muslim students (N = 9,270; α = 0.842 at the first timepoint; α = 0.865at the second timepoint; α = 0.858at the third timepoint).

Interfaith learning and development framework

Variables comprising the interfaith learning and development framework (ILD; Mayhew & Rockenbach, Citation2021) were constructed from institutional-level and student-level responses to the IDEALS instrument; the ILD is illustrated in . All continuous variables were standardized and thus can be interpreted as a change in effect size units, whereas categorical variables were effect coded, thereby allowing for comparison of individual categories to an overall sample mean.

Environmental factors

The environmental factors included ILD components comprising the institutional context and relational context. With regard to the institutional context, institutional campus climate and institutional campus culture were measured using empirically validated factor scores constructed from the larger IDEALS study. Reliability for all factor scores remained acceptable with this study’s analytic sample of non-Muslim students (). Data for the institutional campus conditions variables were retrieved from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). Institutional campus behaviors were computed based on the total number of programs, spaces, opportunities, and policies reported by institutional representatives. Similar to the institutional climate and culture, students’ experiences with the relational context on campus were measured using factor scores constructed from the larger IDEALS study; they, too, maintained good reliability when applied to the analytic sample in this study, as reported in .

Table 1. Factors and items used for measurement of ILD institutional and relational contexts.

In accordance with the ILD, variables related to students’ interfaith engagement behaviors and disciplinary context were also included. For interfaith engagement behaviors, students self-reported the activities on campus in which they participated; those activities included formal and informal, as well as academic and social interfaith activities that were made available on campus. For disciplinary context, students self-reported their primary academic major.

Student identities

At the student level, identity variables included students’ self-reported gender identity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, generation status (i.e., whether they were first-generation college students), RSS identification, and political leaning. All multi-categorical variables (e.g., race/ethnicity, worldview identification) were effect coded. Effect coding eliminates the need to identify a reference group for the interpretation of analytical results and instead allows for direct comparison of each subgroup to an overall sample mean (Mayhew & Simonoff, Citation2015).

Other student inputs

As represented in the ILD, additional student-level variables capturing students’ pre-college experiences and knowledge — specifically, their pre-college interfaith activities, high school GPA, and appreciative knowledge of Islam — were also measured via the IDEALS instrument and included in the current study’s analyses. Students’ appreciative knowledge of Islam was measured based on whether students could accurately answer a question pertaining to Islam (“In the Muslim tradition, fasting takes place from dawn until dusk during the month of Ramadan.”) at one or more of the survey timepoints.

Data analysis

We used latent growth modeling (LGM) to evaluate and explain change over time in non-Muslim college students’ appreciative attitudes toward Muslims. LGM is a method that models students’ longitudinal growth trajectories for a particular outcome over time (Seclosky & Denison, Citation2018). Additionally, LGM allows for the identification of the factors that help explain the growth of the outcomes over time (Seclosky & Denison, Citation2018); in other words, it allowed us to first model change in non-Muslim students’ appreciative attitudes toward Muslims during college, and then to identify institutional behaviors and educational practices that may have contributed to that change. Given the complex and hierarchical nature of our dataset — with respondents attending 122 institutions across the United States — design-based multilevel modeling was applied at all stages of data analysis. This approach uses robust standard errors to account for the clustering of students within their unique institutional contexts.

Describing change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims

In order to evaluate whether non-Muslim students increased in their appreciation toward Muslims during the collegiate experience (RQ1), we constructed an LGM with appreciative attitudes toward Muslims as our outcome variable, measured at the three IDEALS survey timepoints. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to account for missing data (Grimm et al., Citation2017); though, as noted, all students in the analytic sample responded to at least two survey administrations, thus providing sufficient information from which to construct individual growth trajectories. Fit of the data to the constructed model was evaluated using several statistical indices; indicative of good model fit is a small, non-significant chi-square test; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.05; comparative fit index (CFI) greater than 0.95; and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) less than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Once the accepted model fit was confirmed, we obtained growth parameters from the model to explain the change in non-Muslim students’ appreciation toward Muslims during their four years of college. The first growth parameter — the intercept — quantified the mean baseline of appreciative attitudes toward Muslims when students entered college. The second growth parameter — the slope — quantified the mean change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims at each timepoint. Of note, a statistically significant (p < .05) slope indicates that the change documented in an outcome over time is significantly different from zero; in other words, a significant, positive slope is interpreted as an indicator that there is substantive growth over time in the outcome of interest.

Predicting change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims

In order to evaluate the environmental factors (RQ2) and student identities (RQ3) that contributed to growth in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims during college, the variables comprising the Interfaith Learning and Development Framework (ILD; Mayhew & Rockenbach, Citation2021) were incorporated into the model. Including these as covariates in the model allowed us to examine the extent to which each variable predicted students’ baseline appreciative attitudes (i.e., the intercept) and students’ change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims over time during their four years of college (i.e., the slope). Of note, a statistically significant (p < .05) slope indicates that the change documented in an outcome over time is significantly different from zero; in other words, a significant, positive predictor of the slope is interpreted as a variable associated with substantive growth over time in the outcome of interest. For all analyses, the outcome variables were standardized based on Time 1 responses.

Limitations

Several limitations could be recognized with regard to this study’s sample, which is robust and diverse yet not representative of the population. Because the sample was limited to non-Muslim students, no sampling weights were used to mitigate response bias. As a result, the analytical sample overrepresents white students, women, and Christians while underrepresenting other demographic backgrounds. In addition, and due to the number of institutions represented in the sample, the number of institutional-level predictors was limited and did not include geographical region variables. How different populations appreciate Muslims could be related to the region in which they reside, given some trends that could be seen in other indicators, such as political affiliation and voting patterns across geographies. Including such variables in future studies could account for such patterns to provide more directed insights about institutional contexts.

Further, limitations in some of the constructs must also be explicated. The single question included in the appreciative knowledge item is insufficient for capturing appreciative knowledge and is, therefore, a limited indicator of appreciation. Based on previous works (e.g., Mayhew & Rockenbach, Citation2021; Patel & Meyer, Citation2011), we maintained that appreciative knowledge is a theoretically justified variable and was kept in the model as a control. The Likert scale used in the responses makes it difficult to ascertain growth among groups that start with very positive attitudes and have less room to grow due to the ceiling effect.

Results

Describing change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims

Model fit indices were retrieved for the latent growth model: (χ2 (48) = 320.10, p < .001; RMSEA [95% CI] = 0.025 [0.022, 0.027]; CFI = 0.960; SRMR = 0.012). These indices were well within accepted standards (e.g., Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), with RMSEA below 0.05, CFI greater than 0.95, and SRMR below 0.08. Although the chi-square test of model fit was significant, we relied on the totality of the evidence — which was otherwise quite good — to ascertain model fit. Additionally, it is common for large samples, such as the one used in this study, to produce a significant chi-square test of model fit, even for well-fitting models (Hamilton et al., Citation2003).

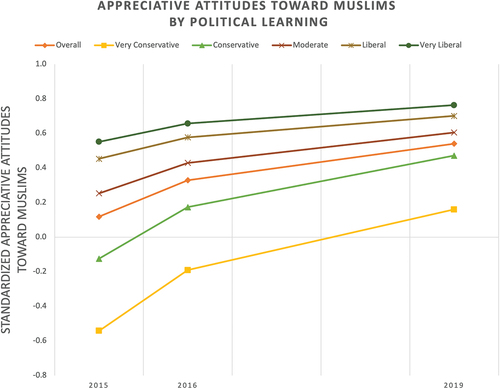

Both the intercept and slope parameters retrieved from the model were positive and significant (intercept = 0.118, p < .001; slope = 0.211, p < .001). Relevant to the question as to whether non-Muslim students increased in their appreciation toward Muslims during the collegiate experience (RQ1) was the significant, positive slope. That slope indicated that the non-Muslim students in the analytic sample did, in fact, report growth in their appreciative attitudes toward Muslims during their four years of college. This growth trend is depicted in .

Predicting change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims

Several significant predictors of the latent slope emerged, indicating environmental factors and student identities associated with growth in Muslim appreciation during college (see ). Environmental factors associated with change in Muslim appreciation during college included the institutional context, relational context, and interfaith engagement behaviors.

Table 2. Predictors of change (slope) in Muslim appreciation with associated entry (intercept) effects.

Institutional context

With regard to the institutional context, institutional control, institution-level changes in appreciative attitudes, and interfaith diversity programs on campus were all associated with changes in Muslim appreciation over time. Specifically, students who attended private institutions experienced more growth in appreciative attitudes during their four years of college (B = 0.069, p = .004). Additionally, students attending campuses with more appreciative campus cultures (i.e., campuses where students in the aggregate grew more appreciative of Muslims) reported significantly lower Muslim appreciation upon entry to college (B = −0.121, p < .001) while also reporting more growth in Muslim appreciation over their four years of college (B = 0.094, p < .001). Although students attending institutions with more pluralistic campus cultures (i.e., campuses where students in the aggregate grew more pluralistic over time) reported significantly lower Muslim appreciation at college entry (B = −0.049, p = .047), campus pluralism was not associated with a change in appreciative attitudes over time.

Finally, the total number of religious, spiritual, or interfaith diversity programs provided on campus predicted a change in students’ appreciative attitudes toward Muslims over four years. Specifically, students attending institutions with more religious, spiritual, or interfaith diversity programs provided on campus had less growth in Muslim appreciation over time (B = −0.018, p = .013). Other institutional campus behaviors — those pertaining to the number of religious, spiritual, or interfaith spaces, curricular opportunities, and policies on campus — did not have a statistically significant effect on students’ appreciation attitudes toward Muslims.

Relational context

Dimensions of the relational context were associated with either an increase or decrease in growth in Muslim appreciation. Students who reported finding space for support and spiritual expression on their campuses reported higher Muslim appreciation at college entry (B = 0.056, p < .001), and they also experienced more growth in Muslim appreciation over four years (B = 0.040, p < .001). Conversely, students who experienced more negative engagement on campus reported less growth in Muslim appreciation during their time in college (B = −0.029, p = .004).

Although students who reported more coercion on campus started college with significantly lower levels of Muslim appreciation (B = −0.055, p = .004), and alternatively, students who reported experiencing more provocative encounters with worldview diversity on campus started college with significantly higher levels of Muslim appreciation (B = 0.072, p < .001), coercion and provocative encounters were not associated with growth in appreciation.

Interfaith engagement behaviors

Formal social interfaith engagement behaviors were the only type that predicted change in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims during college. Specifically, students who participated in two or more formal social interfaith activities experienced more growth in Muslim appreciation during college (B = 0.057, p = .003). Similarly, students who participated in two or more informal social activities also experienced more growth in appreciation (B = 0.107, p = .002). Although formal social behaviors were the types that predicted growth in appreciation over time, other types of behaviors predicted students’ appreciation at baseline; participation in at least one formal academic behavior (B = −0.071, p = .035, at least one informal academic behavior (B = 0.078, p = .006), and two or more informal academic behaviors (B = 0.067, p = .048) were associated with higher Muslim appreciation at the start of college.

Student identities

Aspects of students’ identities associated with change in Muslim appreciation during college included gender identity, sexual orientation, and political leaning. First, women entered college with higher levels of appreciation toward Muslims (B = 0.142, p < .001), and experienced more growth in appreciation toward Muslims over four years (B = 0.035, p = .001). Second, although students who identified as LGBTQ+ entered college with significantly higher levels of appreciation toward Muslims than those who identified as heterosexual (B = 0.081, p = .007), they experienced less growth in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims during their four years of college (B = −0.043, p = .003).

Finally, the relationship between political leaning and Muslim appreciation — both at baseline and over time — varied based on students’ political leaning (). Students who identified as very conservative or conservative reported lower levels of Muslim appreciation than their peers at college entry (very conservative: B = −0.660, p < .001; conservative: B = −0.243, p < .001), but then experienced more growth in that appreciation during their college years (very conservative: B = 0.140, p < .001; conservative: B = 0.087, p < .001). Conversely, students who identified as moderate, liberal, or very liberal reported higher levels of Muslim appreciation than their peers at college entry (moderate: B = 0.135, p < .001; liberal: B = 0.335, p < .001; very liberal: B = 0.433, p < .001), but then experienced less growth in that appreciation during their four years of college (moderate: B = −0.035, p = .003; liberal: B = −0.087, p < .001; very liberal: B = −0.105, p < .001).

Figure 3. Growth trajectory for standardized appreciative attitudes toward Muslims by time point by political leaning.

Race/ethnicity predicted non-Muslim students’ appreciative attitudes toward Muslims only at college entry, with Asian/Pacific Islander students starting college with significantly less appreciation toward Muslims (B = −0.116, p < .001) and Latinx and white students starting college with significantly more appreciation toward Muslims (Latinx: B = 0.052, p = .046; white: B = 0.078, p < .001). Similarly, with regard to RSS identification, students with minoritized RSSIs started college with higher levels of appreciative attitudes toward Muslims (B = 0.089, p = .019), and students with nonreligious RSSIs started college with lower levels of appreciative attitudes toward Muslims (B = −0.087, p < .001).

When it came to student-level variables pertaining to students’ pre-college experiences and knowledge, only pre-college interfaith activities were related to changes in Muslim appreciation during college. In fact, students’ pre-college interfaith activities predicted both their appreciative attitudes toward Muslims at college entry and over four years; students who reported participating in more pre-college interfaith activities entered college with higher levels of Muslim appreciation (B = 0.151, p < .001), but then experienced less growth in that appreciation during their four years of college (B = −0.040, p < .001). Although students with greater high school GPAs and more appreciative knowledge of Islam both started college with more Muslim appreciation (high school GPA: B = 0.058, p < .001; appreciative knowledge: B = 0.280, p = .001), neither predicted change in that appreciation over four years.

Discussion

According to the growth model analysis, colleges and universities succeed in spurring the development of the appreciative attitudes of non-Muslims toward Muslims during the collegiate years. Regardless of pre-college characteristics, institutional characteristics, student demographics, or areas of study, students leave college significantly more appreciative of Muslims compared to when they first arrived. Previous research has demonstrated that students at the end of the first year also become more appreciative of Muslims compared to when they started college (Shaheen, Dahl, et al., Citation2022), perhaps as a result of the exposure to diversity coupled with intentional first-year experience programs (Bowman, Citation2013). The present study shows that growth continues beyond the first year in college. Beyond the first year, institutions continue to have a positive influence on students. This finding is especially promising, given the timing of the survey administration (2015–2019), a period that captured the 2016 presidential elections and the tenure of Donald Trump in the White House. That era was turbulent for Muslims, given the explicit anti-Muslim attitudes of the Trump administration (Pertwee, Citation2020). Nevertheless, non-Muslim students were able to navigate negative messaging about Muslims and emerge at the end of college with an increased appreciation of Muslims. Reaffirming the positive role of higher education in fostering positive outcomes, our findings should come as good news to educators.

Campus culture and climate matter for facilitating growth in appreciative attitudes toward Muslims. When educators foster a culture of appreciation, the benefits extend to students regardless of their attitudes upon matriculation. We add our voices to others (e.g., Selznick et al., Citation2021; Shaheen, Dahl, et al., Citation2022) who emphasized the importance of fostering a culture of appreciation on campus. Indeed, institutions that provide spaces for support and spiritual expression are more likely to enroll students who are appreciative of Muslims and to continue to support their growth throughout their college experience. Students who indicate that their campuses are safe places to express their worldviews, that faculty and staff accommodate their religious needs, and that classes are a safe place to express their worldviews, regardless of their worldview identification, become more appreciative of Muslims and less likely to display Islamophobia or anti-Muslim attitudes as graduates.

When it comes to engagement, only social engagement predicted growth in Muslim appreciation. Our findings align with previous research about interfaith attitudes in general (Patel & Meyer, Citation2011), attitudes toward Muslims in particular (Rockenbach, Mayhew, Bowman, et al., Citation2017), and the long-demonstrated role of intergroup contact as a context for democratic healing (Allport, Citation1954). This study provides an added nuance to the role of social engagement: students who participated in at least one social activity did not demonstrate significant growth across four years, whereas students who participated in two or more did. In contrast, students who engaged in one or more informal social engagements during the first year showed significant growth in appreciation at the end of the first year compared to when they arrived on campus (see Shaheen, Dahl, et al., Citation2022). Putting those two findings in dialogue, we contend that interfaith engagement cannot be one-and-done but must be part of a sustained campus effort to promote formal interfaith opportunities and facilitate informal encounters.

In contrast, academic forms of interfaith engagement were not significant predictors of growth. The appreciation of Muslims cannot be taught in a classroom alone but must be experienced through sustained contact with diversity and difference. Although interfaith academic engagement could contribute to positive interfaith learning and development outcomes (e.g., Rockenbach et al., Citation2015), in the long-term and specifically related to countering Islamophobia, academic engagement seems to fall short. That said, a significant predictor of growth was spaces for support and spiritual expression. This construct includes an item directly pertaining to classroom spaces (i.e., My classes are safe places for me to express my worldview). This relationship suggests that the perception of classroom spaces as inviting for expressions of diverse RSS identities, not necessarily teaching appreciation in the classroom, can play a role. There is potential for classroom spaces to be positive contributors to appreciative attitudes when they invite the open expression of beliefs and exposure to diverse RSS narratives (see Shaheen et al., Citation2021; Shaheen, Mayhew, et al., Citation2022).

Interestingly, the total number of religious, spiritual, or interfaith programs provided by the institution was a negative predictor of the rate of growth (i.e., the slope) but was not predictive of appreciation at matriculation (i.e., the intercept). In other words, institutions with more programs did not attract and enroll students who were already more or less appreciative of Muslims compared to their peers. The variable did predict the rate of growth: campuses with more programs available have a lower rate of increase in appreciation compared to campuses with fewer programs available. Simultaneously, students who engaged in two or more of these activities were more likely to grow than those who did not. These two findings together indicate a potential disconnect between institutional behavior and student behavior in that the abundance of programs available seemed to stall development, yet student engagement in such programs conversely boosted development. A closer examination of this disconnection is important for future studies to consider the complex relationship between the availability of programs and actual engagement.

Finally, race/ethnicity was not predictive of growth in Muslim appreciation. This finding mirrors other nationally-representative data that show little indication of affective solidarity between Muslims and racially-minoritized groups (see Ponce, Citation2020). The lack of a strong indication of affective solidarities suggests that “even society’s main minority groups see Muslim Americans as outsiders” (Ponce, Citation2020, p. 2788). These characteristics did not emerge as significant predictors of growth in appreciation over time. Students who identified as LGBTQ+ came to college with higher appreciation compared to their heterosexual peers and, perhaps as a result, grew at a lower rate. A similar observation could be made about students who are liberal. In contrast, those who identified as “very conservative” or “conservative” started college with less appreciation for Muslims compared to everyone else. Signifying the transformative impact of higher education, conservatives showed significant growth in appreciative attitudes over time, and the gap between liberals and conservatives seemed to narrow by the end of college, all things being equal. Conservative students did come to college with less appreciation. However, despite the raging Islamophobic rhetoric that accompanied the 2016 Trump presidential campaign (Rana et al., Citation2020), conservative students who engaged socially with people of other social identities seemed to have partially overcome the pre-college socialization that may have led them to come to college with less favorable attitudes toward Muslims.

Implications

Despite the frequent critique of campus social engagements as superfluous to the “real” purpose of college, students need sustained social interactions with diversity to reduce Islamophobia and advance appreciation of Muslims. Educators need to think creatively about facilitating such interactions in a formal setting. Students can attend religious services for a tradition that is not their own or participate in a campus interfaith group. Student affairs professionals need to connect with local Muslim communities to establish relationships that allow for social engagement to occur on and off campus. Students can also attend a lecture or a panel discussing religious diversity and interfaith cooperation with a specific focus on the Muslim identity. Institutions can establish interfaith-themed residence halls that include educational modules or service activities that engage different religious groups, including Islam. Campus-wide communications from administrators (e.g., university president) about religious diversity can have an impact on attitudes. For example, a message from the university president about Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting, and subsequent Eid celebrations could go a long way in countering Islamophobic messaging. Even having halal food options in the dining halls or extending dining hall hours during Ramadan to allow Muslims access to food later in the evening could be effective. After all, how could non-Muslims dine with Muslim friends if they cannot find food they can eat on campus?

The finding about the role of academic engagement (or lack thereof) provides an opportunity for educators to rethink how interfaith academic encounters could be facilitated. Connecting the academic with the social could help integrate the academic environment through co-curricular interfaith initiatives. For example, a course in sociology could have a service component that engages people of a particular faith community or that addresses interfaith concerns. What if the introduction to sociology class facilitated students and faculty volunteering at a local faith community like a mosque? Academic engagement should not be detached from the social realities of students. Rather, classroom engagement could interweave social awareness and productive contact into its structure, provided that faculty are invested in elevating the developmental reach of the courses they teach.

Finally, the lack of association between racial and ethnic identities and appreciation does not negate the racialization of the Muslim identity and the importance of considering the complexity of interlocking systems of marginalization in shaping attitudes. Insights from previous research affirm that conversations about racism and Islamophobia are necessary and must continue to be foregrounded along with other intersectional considerations, such as the intersections of gender and socioeconomic status. The findings about political orientation and appreciative attitudes toward Muslims signal the potent effect of political rhetoric on attitudes during the time of data collection and therefore highlight the need for educators to pay closer attention to the social identities of the students who engage in interfaith programs and initiatives to reach a broad spectrum of students, including politically conservative students. Educators need to lean further into the coupling of religion and politics — the two are undoubtedly connected, but self-described political orientation does not necessarily represent interfaith attitudes. Knowing that a student is conservative does not necessarily mean that the student is outwardly Islamophobic. The college environment provides the ideal opportunity to explore the interconnected nature of religion and politics. A panel about conservatism and Islamophobia, for example, could provide an avenue for liberals and conservatives alike to engage in productive dialogue.

Conclusion

Despite the turbulent national climate for Muslims between 2015 and 2019, findings from this longitudinal data show that collegiate environments were successful at combating anti-Muslim prejudice and promoting appreciative attitudes toward Muslims. Humanizing Muslims in college involves social exchange, the type of relationship-building that welcomes and embraces. Humanizing the exchange between Muslim and non-Muslim students could disrupt simplistic narratives that assume that those with some political identification also hold defined views about Muslims and Islam. Relationships matter, perhaps now more than ever. To disrupt postsecondary Islamophobic expression, students must have the opportunity to have and build relationships with Muslim peers. Educators are central to providing and optimizing these opportunities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abu Rabia, H. M. (2017). Undergraduate Arab international students’ adjustment to U.S. universities. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(1), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n1p131

- Ahmadi, S., Sanchez, M., & Cole, D. (2019). Protecting Muslim students’ speech and expression and resisting islamophobia. In D. L. Morgan & C. H. F. Davis (Eds.), Student activism, politics, and campus climate in higher education (1st ed., pp. 97–111). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429449178-6

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Perseus.

- Barakat, M. (2018). Advocating for Muslim students: If not us, then who? Journal of Educational Administration and History, 50(2), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2018.1439903

- Bodine Al-Sharif, M. A., & Zadeh, S. H. (2020). A tale of two sisters: A duoethnographical study of religious conversion. In J. T. Snipes & S. Manson (Eds.), Remixed and reimagined: Innovations in religion, spirituality, and (inter)faith in higher education (pp. 105–121). Myers Education Press .

- Bowman, N. A. (2013). How much diversity is enough? The curvilinear relationship between college diversity interactions and first-year student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 54(8), 874–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-013-9300-0

- Bryant, A. N., & Astin, H. S. (2008). The correlates of spiritual struggle during the college years. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2008.0000

- Carter, I. M., Montes, A., Gonzalez, B., Wagoner, Z., Reyes, N., & Escoffery-Runnels, V. (2020). Critical interfaith praxis in higher education: The interfaith collective. In J. T. Snipes & S. Manson (Eds.), Remixed and reimagined: Innovations in religion, spirituality, and (inter)faith in higher education (pp. 29–43). Myers Education Press.

- Cole, D., & Ahmadi, S. (2010). Reconsidering campus diversity: An examination of Muslim students’ experiences. Journal of Higher Education, 81(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11779045

- Cole, D., Ahmadi, S., & Sanchez, M. E. (2020). Examining Muslim student experiences with campus insensitivity, coercion, and negative interworldview engagement. Journal of College and Character, 21(4), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2020.1822880

- Dana, K., Wilcox-Archuleta, B., & Barreto, M. (2017). The political incorporation of Muslims in the United States: The mobilizing role of religiosity in Islam. Journal of Race, Ethnicity, & Politics, 2(2), 170–200. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2017.4

- Edwards, S. (2017). Intergroup dialogue & religious identity: Attempting to raise awareness of Christian privilege & religious oppression. Multicultural Education, 24(2), 18–24.

- Edwards, S. (2018a). Critical reflections on the interfaith movement: A social justice perspective. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000053

- Edwards, S. (2018b). Distinguishing between belief and culture: A critical perspective on religious identity. Journal of College and Character, 19(3), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2018.1481097

- Garner, S., & Selod, S. (2015). The racialization of Muslims: Empirical studies of Islamophobia. Critical Sociology, 41(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920514531606

- Garrod, A., & Kilkenny, R. (Eds.). (2014). Growing up Muslim: Muslim college students in America tell their life stories. Cornell University Press.

- Gerteis, J., Hartmann, D., & Edgell, P. (2020). Racial, religious, and civic dimensions of anti-Muslim sentiment in America. Social Problems, 67(4), 719–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spz039

- Gottschalk, P. (2019). Donald Trump at the intersection of nativism, Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment: American roots and parallels. In P. Morey, A. Yaqin, & A. Forte (Eds.), Contesting Islamophobia: Anti Muslim prejudice in media, culture and politics (pp. 47–69). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Grimm, K. J., Ram, N., & Estabrook, R. (2017). Growth modeling: Structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. The Guilford Press.

- Hamilton, J., Gagne, P. E., & Hancock, G. R. (2003). The effect of sample size on latent growth models [Paper presentation]. Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476862.pdf

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hurtado, S., Alvarez, C. L., Guillermo-Wann, C., Cuellar, M., & Arellano, L. (2012). A model for diverse learning environments. In J. C. Smart & M. B. Paulsen (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 27, pp. 41–122). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2950-6_2

- Interfaith America. (n.d.). https://www.interfaithamerica.org/

- Karaman, N., & Christian, M. (2020). “My hijab is like my skin color”: Muslim women students, racialization, and intersectionality. Sociology of Race & Ethnicity, 6(4), 517–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649220903740

- Lean, N. (2019). American foreign policy, self-fulfilling prophecy and Muslims as enemy others. In P. Morey, A. Yaqin, & A. Forte (Eds.), Contesting Islamophobia: Anti Muslim prejudice in media, culture and politics (pp. 29–46). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Mayhew, M. J., & Rockenbach, A. N. (2021). Interfaith learning and development. Journal of College and Character, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2020.1860778

- Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. B., Bowman, N. A., Seifert, T. A., Wolniak, G. C., Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2016). How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works (Vol. 3). Jossey-Bass.

- Mayhew, M. J., Rockenbach, A. N., & Dahl, L. S. (2020). Owning faith: First-year college-going and the development of students’ self-authored worldview commitments. The Journal of Higher Education, 91(6), 977–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1732175

- Mayhew, M. J., & Simonoff, J. S. (2015). Non-white, no more: Effect coding as an alternative to dummy coding with implications for higher education researchers. Journal of College Student Development, 56(2), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0019

- Morey, P., Yaqin, A., & Forte, A. (Eds.). (2019). Contesting Islamophobia: Anti-Muslim prejudice in media, culture and politics. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Patel, E., & Meyer, C. (2011). The civic relevance for interfaith cooperation for colleges and universities. Journal of College and Character, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-1639.1764

- Pertwee, E. (2020). Donald Trump, the anti-Muslim far right and the new conservative revolution. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(16), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1749688

- Pew Research Center. (2018, January 3). New estimates show U.S. Muslim population continues to grow. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/03/new-estimates-showu-s-muslim-population-continues-to-grow/

- Ponce, A. (2020). Affective solidarities or group boundaries? Muslims’ place in America’s racial and religious order. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(15), 2785–2806. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1691741

- Rana, J., Alsultany, E., Deeb, L., Fadda, C., Abdul Khabeer, S., Ali, A., Daulatzai, S., Grewal, Z., Hammer, J., & Naber, N. (2020). Pedagogies of resistance: Why anti-Muslim racism matters. Amerasia Journal, 46(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00447471.2020.1761278

- Rockenbach, A. N., Lo, M. A., & Mayhew, M. J. (2017). How LGBT college students perceive and engage the campus religious and spiritual climate. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(4), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1191239

- Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Bowman, N. A., Morin, S. M., & Riggers-Piehl, T. (2017). An examination of non-Muslim college students’ attitudes toward Muslims. The Journal of Higher Education, 88(4), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.1272329

- Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Correia-Harker, B. P., Morin, S., & Associates. (2017). Navigating pluralism: How students approach religious difference and interfaith engagement in their first year of college. Interfaith Youth Core.

- Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., Morin, S., Crandall, R. E., & Selznick, B. (2015). Fostering the pluralism orientation of college students through interfaith co-curricular engagement. The Review of Higher Education, 39(1), 25–58. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2015.0040

- Ross, S. N. (2014). Diversity and intergroup contact in higher education: Exploring possibilities for democratization through social justice education. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(8), 870–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.934354

- Runnymede Trust. (1997). Islamophobia: A challenge for us all. http://www.runnymedetrust.org/uploads/publications/pdfs/islamophobia.pdf

- Seclosky, C., & Denison, D. B. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook on measurement, assessment, and evaluation in higher education (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Selznick, B. S., Mayhew, M. J., Dahl, L. S., & Rockenbach, A. N. (2021). Developing appreciative attitudes toward Jews: A multi-campus investigation. The Journal of Higher Education, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1990632

- Shaheen, M. (2020). Creating my borderlands: Queer and Muslim identity development through a scholarly personal narrative. In J. T. Snipes & S. Manson (Eds.), Remixed and reimagined: Innovations in religion, spirituality, and (inter)faith in higher education (pp. 89–103). Myers Education Press.

- Shaheen, M., Dahl, L. S., Mayhew, M. J., & Rockenbach, A. N. (2022). Inspiring Muslim appreciation in the first-year of college: What makes a difference? Research in Higher Education, 64(2), 177–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-022-09701-y

- Shaheen, M., Mayhew, M. J., & Rockenbach, A. N. (2022). Religious coercion on public university campuses: Looking beyond the street preacher. Journal of College Student Development, 63(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2022.0007

- Shaheen, M., Mayhew, M. J., & Staples, B. A. (2021). StateChurch: Bringing religion to public higher education. Religions, 12(5), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050336

- Shammas, D. (2017). Underreporting discrimination among Arab American and Muslim American community college students: Using focus groups to unravel the ambiguities within the survey data. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815599467

- Whitehead, A. L., & Perry, S. L. (2020). Taking America back for god: Christian nationalism in the United States. Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, S. (2020). Countering misperceptions to reduce prejudice: An experiment on attitudes toward Muslim Americans. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 7(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.22

- Yousafzia, A. (2020). Identity performance of Muslim international women in campus microsystems: A narrative inquiry. In J. T. Snipes & S. Manson (Eds.), Remixed and reimagined: Innovations in religion, spirituality, and (inter)faith in higher education (pp. 151–168). Myers Education Press.