Abstract

Leisure crafting (i.e., proactive leisure activities targeted at goal-setting, human connection, and personal development) may have context-free and work-related benefits for individuals. With Study 1 of the present paper, we aimed at making causal inferences about leisure crafting outcomes: A 4-week randomized controlled trial compared an online leisure crafting intervention against a control group on context-free outcomes (meaning in life, need satisfaction, self-efficacy and context-free creativity) and work-related outcomes (work engagement, seeking challenges, and employee creativity). Analyses revealed that the intervention group experienced a greater increase in meaning, self-efficacy, work engagement and employee creativity compared to the control group. Study 2, a cross-sectional survey, replicated the findings of Study 1; additionally, it revealed positive links between leisure crafting and other-ratings of subjective well-being and context-free creativity. We discuss and integrate the findings of our studies and formulate recommendations on how organizations can use leisure crafting to create a happy workforce.

Amy and Zoe are both busy professionals who love to read books in their spare time. Amy has no agenda in her hobby; every now and then she simply buys books that she sees in bookstore windows or hears about from others and tries to read at least a little when she finds some time. Zoe is more particular about her hobby. She makes reading lists that guide which book she will buy, according to the themes that she wants to read about. She blocks time slots for reading her book during which she refuses to be interrupted by her spouse or kids. She recently initiated a weekly book club together with a number of friends and in the back of her mind, she flirts with the idea of writing her own book one day.

While the former employee of the aforementioned example most likely represents what we all recognize as a hobby or what Stebbins (Citation1982, p. 253) called “casual leisure”; the latter employee, Zoe, goes one step further. Her leisure behavior could be referred to as “leisure crafting”, which is defined as “the proactive pursuit of leisure activities targeted at goal setting, human connection, learning and personal development” (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016, p. 508). We note that while both employees do the same leisure activity, what differs is the mindset with which they approach it. Accordingly, the present paper addresses leisure crafting as a cognitive behavioral strategy that individuals adopt throughout the pursuit of leisure activities rather than as a certain type of activity.

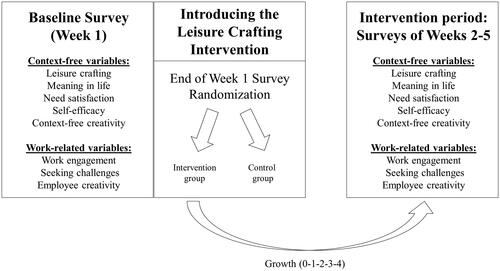

We suggest that leisure crafting can be a powerful way in which employees manage their work-life balance. Individuals nowadays are not defined only by their jobs; instead, they have to juggle between the demands as well as the joys of different life domains. For example, next to the widely studied family domain (Clark, Citation2000), the domain of leisure activities (also simply known as “hobbies”) has been addressed as one that can give people a sense of fulfillment, purpose and life satisfaction (Guest, Citation2002; Stenseng & Phelps, Citation2013). However, the complex nature of contemporary jobs and recent societal developments (e.g., COVID-19 crisis) often blur the boundaries between work and private life (Trougakos et al., Citation2020) and make it challenging to pursue meaningful leisure activities systematically. Therefore, it is imperative to propose simple, attainable, and understandable ways to inform, train and empower individuals as to how they can use the full potential of their leisure time. The main goal of the present study is to conduct and test an online leisure crafting intervention that trains individuals on how to develop themselves and grow via leisure crafting (see , for our research design and expectations).

Currently, there are only a handful of published empirical studies connecting the concept of leisure crafting with different benefits for individuals (e.g., Abdel Hadi et al., Citation2021; Chen, Citation2020; Hamrick, Citation2022; Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016; Petrou et al., Citation2017). Using survey methodology, these studies have uncovered the positive correlates of leisure crafting with individual context-free as well as work-related outcomes. Even though survey studies represent a valuable methodology within a nascent research field, intervention research methodology, and especially the randomized controlled trial design, arguably goes one step further. Randomized controlled trials increase our ability for causal inferences and they reduce the possibility of spurious causality and biases (Kristensen, Citation2005; Mukherjee & Dhar, Citation2023). Therefore, our first contribution to the literature is that—to the best of our knowledge—we conduct the first known intervention to target Petrou and Bakker’s (Citation2016) leisure crafting conceptualization. Accordingly, participants are trained to recognize and practice three distinct elements of leisure crafting (i.e., goal-setting, learning and human connection), which are parallel to the three basic human needs, proposed by the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Our overarching expectation is that by “learning” how to enact leisure crafting via an intervention, individuals will gain more access to a number of context-free positive outcomes (i.e., meaning in life, need satisfaction, self-efficacy, context-free creativity) as well as a number of spillover effects on positive work-related outcomes (i.e., work engagement, seeking challenges, and employee creativity). This distinction between work-related and context-free benefits is in agreement with existing literature on work-life balance (e.g., Demerouti et al., Citation2005). What this distinction essentially means in practice is that leisure crafting helps individuals increase their quality of life overall (context-free benefits) but also acts as a resource that helps individuals perform in a life domains where performance is relevant and necessary, such as at work (De Bloom et al., Citation2020).

Related to our first contribution, our second contribution is that our intervention field study helps to bridge the gap between science and practice, and thus ensure ecological validity (Radaelli et al., Citation2014). In other words, we already know from survey studies that leisure crafting, which respondents incidentally report, seems to be beneficial. But what happens if we actually “train” employees to enact leisure crafting behaviors? Will they understand the concept of leisure crafting and learn to display it, and if they do, will that have an effect on their lives? Those are questions that can be effectively answered only via intervention research in the field. Our aspiration is to develop an intervention that can be used by professionals to coach employees to increase their quality of life not only via their actions at work but also outside of it, thus, maximizing their potential for a happy life.

The theoretical rationale for our expectations draws on the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017) and the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) and on how these theories have been used by theoretical frameworks of spillover within life domains (e.g., De Bloom et al., Citation2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012). Based on these theories, it can be inferred that leisure crafters, who try to align their leisure activities according to their basic human needs, have access to a broad range of wellbeing and performance outcomes (e.g., Ng et al., Citation2012; Tang et al., Citation2020). In other words, leisure crafters shape a satisfying, meaningful and functional life. Furthermore, by providing access to new skills and meaningful relationships with others, leisure crafting has the potential to enhance personal resources (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016). According to the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001), humans value resources and strive to sustain them but also to capitalize on them. This means that resources can have double benefits: They are important in their own right and also because they can be used to generate other resources. Thus, resources that are generated via leisure crafting will not simply stay within the leisure domain but they have the potential to spill over to other life domains. As such, they will affect and improve other life domains (e.g., work) and, thereby, also impact peoples’ lives overall (De Bloom et al., Citation2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012).

Last but not least, even though an intervention is the primary aim of our study, we will also conduct a follow-up cross-sectional survey study on the correlates of leisure crafting. This follow-up study will cross-examine the findings of our intervention via a different methodology and it will also deal with common-method bias by employing other-ratings.

Conceptualizing leisure crafting

To date, two leisure crafting conceptualizations, accompanied by respective operationalizations, have been proposed. Petrou and Bakker (Citation2016) suggested that leisure crafting refers to the proactive pursuit of leisure activities targeted at autonomous goal setting, learning and human connection. This definition is strongly aligned with the three basic human needs proposed by the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), namely, autonomy, competence and relatedness. More recently, Tsaur et al. (Citation2023) proposed that leisure crafting consists of increasing structural and social leisure resources, increasing leisure challenges and decreasing leisure barriers. This form of leisure crafting is aligned with the job-demands resources model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), viewing any (work) environment as consisting of resources, challenges and demands. Both of these conceptualizations have been proposed together with a relevant questionnaire that can be used to operationalize leisure crafting accordingly (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016; Tsaur et al., Citation2023).

The present paper uses the leisure crafting conceptualization and operationalization proposed by Petrou and Bakker (Citation2016) for two reasons. First and most importantly, the stance of our intervention study is that active and committed leisure pursuit is particularly satisfying and enriching for individuals when it enables them to pursue their basic human needs. These three needs, addressed by the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), are present in Petrou and Bakker’s (Citation2016) leisure crafting operationalization. To demonstrate, this operationalization refers to autonomous behavior (e.g., “I try to set myself new goals to achieve through leisure activities”), learning (e.g., “I try to increase my skills through leisure activities”) and relatedness (e.g., “I look for inspiration from others through my leisure activities”). This type of leisure crafting is thus aimed at optimizing the resource-enhancing potential of leisure activities that may be already inherently resource-providing. This is different from the approach of Tsaur et al. (Citation2023), who state that leisure crafting is aimed at achieving a balance between leisure demands and resources (e.g., see item “I avoid injury during activity participation” from subscale “decreasing leisure barriers” or item “I expect outstanding performance in my leisure participation” from subscale “increasing challenging leisure demands”). In that sense, while the former operationalization addresses how leisure may address basic human needs and, thereby, enhance one’s resources pool, the latter conceptualization defines leisure crafting as directly impacting demands and resources. For the purposes of an intervention, we find it more straightforward to instruct participants to pursue leisure activities in a way that addresses their human needs (e.g., “try to use your activity in order to learn something new every week” or “in order to get inspiration from others or to inspire others”), rather than instructing participants to directly alter their leisure demands or resources (e.g., “try to avoid injuries” or “achieve outstanding performance in leisure participation”).

Second, previous studies addressing the positive outcomes of leisure crafting used Petrou and Bakker’s (Citation2016) conceptualization and as we strived to test the robustness of these previous findings and to extend them, we also preferred to use Petrou and Bakker’s (Citation2016) conceptualization. These previous studies have uncovered that leisure crafting has various context-free benefits for individuals, such as, need satisfaction Petrou & Bakker (Citation2016) and meaning-making (Petrou et al., Citation2017). In addition to these effects for individuals’ life overall, empirical research has revealed that leisure crafting may help individuals ripe benefits in specific life domains, such as their work. Specifically, leisure crafting has been connected to less work stress (Abdel Hadi et al., Citation2021) and even to employee creativity (Hamrick, Citation2022).

Our focal outcomes

To select our focal outcomes and to substantiate our predictions, we draw on existing empirical research on leisure crafting (e.g., Hamrick, Citation2022; Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016; Petrou et al., Citation2017). However, because existing empirical research on leisure crafting is scant, we also make use of theoretical work on crafting different life domains (e.g., De Bloom et al., Citation2020), theoretical work on the spillover between life domains (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012) and also empirical work on positive outcomes of leisure behavior in general and not leisure crafting per se (e.g., Iwasaki, Citation2007). Even though leisure studies have addressed very diverse benefits of leisure, we have decided to focus on three important pillars within the potential outcomes of leisure crafting: Learning (e.g., creativity or self-efficacy), meaning (e.g., meaning in life), and positive affect and/or satisfaction (e.g., need satisfaction or work engagement). We follow work-life balance literature (Demerouti et al., Citation2005) and we categorize our outcomes within two clusters, namely, context-free outcomes and work-related outcomes of leisure crafting.

Context-free positive outcomes of leisure crafting

In the present paper, we focus on various context-free potential benefits of leisure crafting. Those include (a) meaning in life, defined as the felt significance about one’s being and existence (Steger et al., Citation2006), (b) the satisfaction of basic human needs, namely, autonomy, competence and relatedness (Sheldon et al., Citation2001), (c) self-efficacy, defined as the confidence in one’s ability to deal with demanding life situations (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, Citation1995) and (d) context-free creativity, defined as the generation of creative ideas throughout one’s life overall (Kaufman & Baer, Citation2004).

Meaning in life

People who tie their identity only to one thing, person, or life domain may feel constrained and less fulfilled (Ruderman et al., Citation2002). However, by pursuing active and serious leisure activities, people see in themselves multiple roles rather than one single role. Therefore, they create narratives and identities about their place in the world and construct meaning around their lives and life in general (Bailey & Fernando, Citation2012). A notable similarity between active leisure behavior and meaning in life is that they both entail a “survive and thrive” dynamic (Iwasaki, Citation2007). For example, via leisure crafting, individuals may deal with life challenges (e.g., via the human connection aspect of leisure crafting) but they can also capitalize on what they are good at (e.g., via the goal-setting and learning component of leisure crafting). Exactly this dual role is what drives individuals and, thus, can create a meaningful life. People create meaning by surviving difficulties (e.g., processing trauma) but also by growing or developing on an area of their choice. Previous research that uses weekly survey methodology has confirmed the link from leisure crafting to meaning (Petrou et al., Citation2017).

Need satisfaction

Unlike casual leisure activities, leisure crafting has three elements that originate from the three basic human needs of the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). The fact that leisure crafting is a proactive pursuit and people set their own goals likely satisfies people’s need for autonomy. Trying to learn and develop during leisure activities likely satisfies the need for competence. The need for relatedness can be satisfied when people strive to inspire others or get inspired by others. The idea that crafting initiatives help individuals address their basic human needs in different contexts of their life is in agreement with theoretical work on crafting one’s life domains (De Bloom et al., Citation2020). A previous weekly diary study has indeed revealed that on weeks when participants reported more leisure crafting, they also reported higher satisfaction of their autonomy and relatedness needs (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016).

Self-efficacy

It is exactly this element of serious long-term and committed activities and the associated feeling of growth and fulfillment that we propose will help leisure crafters to feel also more efficacious (i.e., an individual’s belief in their capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments; Bandura, Citation1997). Leisure entails joys (Wei et al., Citation2015) but also frustrations, for instance, juggling incompatible demands of different life domains or encountering resistance from people in other life domains (Godbey et al., Citation2010). Through positive physiopsychological states such as joy, but also through dealing with challenges successfully, leisure crafters should feel empowerment and ownership of their lives, enhancing their self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997). Additionally, looking for inspiration from others through leisure activities may act as a positive vicarious experience that boosts self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997).

Context-free creativity

Last but not least, leisure activities, from physical (Bollimbala et al., Citation2021) to intellectual activities (Wang, Citation2012) are associated with a need to solve problems and be creative. In fact, many leisure activities have a creative or artistic nature (Trnka et al., Citation2016). More relevant to our scope, the experiences of leisure crafters that are parallel to the three leisure crafting dimensions have been found to increase creativity. For example, structure gained via goal-setting resembles the exploitation creative process (i.e., people persevere until they find really creative ideas; Nijstad et al., Citation2010). Similarly, the competence gained by leisure crafters naturally enhances their task-related knowledge which is a basic requirement for creativity (Amabile, Citation2013). Finally, learning new things and connecting with others offers access to new mental perspectives which are vital for creativity (Perry-Smith, Citation2014). Therefore, we expect active leisure crafters to increase their creativity throughout their lives (i.e., context-free creativity). Taken together, we, thus, formulate:

Hypothesis 1: Compared to a control group, participants in the leisure crafting intervention will experience growth in context-free positive outcomes, namely, meaning in life (1a), need satisfaction (1b), self-efficacy (1c) and context-free creativity (1d).

Work-related positive outcomes of leisure crafting

In addition, our paper focuses on various potential work-related benefits of leisure crafting. Those include (a) work engagement, defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006), (b) seeking challenges, defined as the proactive pursuit of challenge within one’s job (Petrou et al., Citation2012) and (c) employee creativity, defined as the production of novel ideas that are useful and appropriate for one’s job (Miron et al., Citation2004).

Work engagement

According to the well-studied perspective of spillover, individuals tend to repeat or carry-over positive experiences of one life domain into another. For example, the positivity that they generate or the skills that they learn via leisure behavior have parallel benefits as they can help employees remain positive at work or deal with job challenges and thus, to experience work engagement (Delle Fave & Massimini, Citation2003; Mojza et al., Citation2011; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012). In that sense, people are inventive and they like to capitalize on their gains in multiple ways (Hobfoll, Citation2001). We, therefore, propose that people who engage in leisure crafting gain access to a positive energy (e.g., via human connection) and enthusiasm (e.g., via learning) that may be carried over to their work, increasing their enthusiasm about their job tasks and, thereby, their work engagement.

Seeking challenges

As with any type of crafting, leisure crafting is proactive in its nature (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016). Based on the aforementioned spillover reasoning, people who craft one life domain, should be expected to craft other life domains as well, which has been confirmed empirically (Demerouti et al., Citation2020). The idea here is that people who know (or learned) how to craft will not stay in one life domain; rather they will craft more life domains in order to maximize their life satisfaction (De Bloom et al., Citation2020). More specifically, when individuals discover the joy of leisure projects, they may proactively decide to craft their job as well, which is known as job crafting (Tims et al., Citation2012). Arguably, seeking challenges has been found to be the job crafting dimension with the strongest correlation with leisure crafting (Petrou et al., Citation2017). Employees who explore new terrains via leisure crafting may decide to double their gains by starting up new projects at their work as well (e.g., seek self-chosen and appealing job challenges).

Employee creativity

Last but not least, the ideas and inspiration obtained throughout leisure time will empower leisure crafters to employ them in other domains as well. If one learns to become more creative via leisure activities, it is legitimate to expect that this creativity will be utilized to achieve other well-valued (e.g., work) goals as well. Empirical research has indeed revealed that people with hobbies are also creative employees (Davis et al., Citation2014). As we explained earlier, the gains of leisure crafters (e.g., contact with others or goal-setting) are known antecedents of (context-free) creativity. Therefore, because of the interplay between different life domains (De Bloom et al., Citation2020), the newly acquired tools of leisure crafters can produce multiple benefits by being employed to creatively solve also job-related problems. This idea has received empirical support in a longitudinal study among entrepreneurs (Hamrick, Citation2022). Taken together, we formulate:

Hypothesis 2: Compared to a control group, participants in the leisure crafting intervention will experience a growth in work-related positive outcomes, namely, work engagement (2a), seeking challenges (2b) and employee creativity (2c).

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedure

Prior to data collection, we obtained permission by the Ethics Committee of Erasmus University Rotterdam (reference: 20-067). Respondents were 261 employees within different occupational sectors in The Netherlands, recruited with network sampling by research assistants (Demerouti & Rispens, Citation2014). Selection criteria were that respondents work at least two days per week and have at least one hobby or are willing to find one for the period that the study lasts. Out of 776 individuals who were contacted, 594 (76.55%) individuals responded to the invitation to take part in the study. They were randomly assigned to either an intervention or control condition using simple randomization (Kim & Shin, Citation2014) in the online survey software Qualtrics. The baseline questionnaire was equal for every participant, except that participants in the intervention condition received the online intervention at the end of the questionnaire. From these 594 individuals, n = 102 filled out less than two weekly questionnaires and were therefore not included in the final analyses. Further, in hindsight, we removed data from n = 219 respondents who did not work at least two days a week (i.e., they answered “no” to the filter question about whether they have a paid job for at least two days a week), and n = 16 who reported practising a hobby throughout the study on average less than once a week or they reported that the effort they invested in their intervention (if they belonged to the intervention group) was rated with less than 5.0 on a 1-10 answering scale. The final sample consisted of N = 257 respondents (n = 101 in the intervention group and n = 156 in the control group; response rate = 34%).

Participants in the intervention group (20 men, 80 women and one “other”) were on average 26.9 years old (SD = 12.6). They worked a mean of 20.9 hours (SD = 12.7) per week for an average 4.7 years (SD = 6.6) in occupational sectors, such as healthcare (20%), trades (13%), education (11%), or government (10%). Most of them worked for an organization (85% vs. 11% were self-employed and 4% indicated “other”) and had no managerial position (78% vs. 22% were supervising others). Only five (5%) opted to fill in the questionnaire in English; the rest (95%) completed the questionnaire in Dutch. Participants were either employees-only (42%) or they combined their work with study at the university where the research assistants worked (58%). Using a scale ranging from 1 = “no effort” to 10 = “I have done my best”, they rated their average compliance to the intervention throughout the four weeks with 6.86 (SD = 1.18). Participants in the control group (37 men, 119 women) were on average 30.3 years old (SD = 14.1). They worked a mean of 22.3 hours (SD = 12.1) per week for an average 6.5 years (SD = 9.2) in occupational sectors, such as healthcare (19%), commerce (15%), government (8%), culture and entertainment (8%) etc. Most of them worked for an organization (88% vs. 8% were self-employed and 5% indicated “other”) and had no managerial position (81% vs. 19% were supervising others). They filled in the questionnaire in English (10%) or in Dutch (90%) and were either employees-only (51%) or employees who also studied (49%).

Three student research assistants recruited participants via their professional and personal/social networks, as well as via the snowball technique or via social media (e.g., inviting users of hobby-related Facebook groups to participate in a study with the potential to help them achieve self-development via their hobby). After they agreed, participants received an e-mail invitation with the link to the first weekly (online) survey and information about the purpose of the study, confidentiality, and voluntary participation. Once they gave their informed consent, they proceeded with the survey. In total, there were five weekly surveys (Week 1 was the baseline measurement and Weeks 2-5 comprised the intervention period); invitations were sent each Friday and a reminder was sent to participants who had not filled in their survey each Monday morning. Respondents who completed all five surveys participated in a lottery for five 50-euro’s gift vouchers (or they automatically received study credits if they were students).

The leisure crafting intervention

To the best of our knowledge, there is no prior work testing interventions that use our leisure crafting operationalization. Therefore, we looked at methodological recommendations for two-group Latent Growth Curve Modeling (LGCM) analyses (see below section “analytic approach”) and we aimed at 100 respondents as a minimum sample size for each one of our two groups (i.e., experimental and control group; Fan, Citation2003). In the intervention group, we aimed to increase participants’ leisure crafting. We draw on literature addressing awareness-raising, goal-setting and self-reflection as essential antecedents of behavioral change (Epton et al., Citation2017; Kersten-van Dijk et al., Citation2017). These three elements are congruent with several job crafting interventions (i.e., targeted at employee actions that lead to growth via one’s job rather than via one’s leisure; Mukherjee & Dhar, Citation2023) that our leisure crafting intervention mirrors. Accordingly, at the end of weekly survey 1, participants of the intervention group were asked to find a quiet place and time and watch a 5-minute online training session about how they can achieve self-development via their free-time activities. We made sure that we used the term “self-development” (rather than “leisure crafting”) everywhere so that they remain “blind” to the focal outcome of interest, namely, leisure crafting. Essentially, the video comprised an online PowerPoint presentation with a small screen showing a female trainer presenting the three main components of leisure crafting, namely, goal-setting, learning and development, and human connection (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016). The full presentation can be found on YouTube, both in English and in Dutch (Petrou, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). After they watched the video, participants were asked to create their self-development plan by writing down which leisure activities (hobbies) they will use for their self-development throughout the coming four weeks and on which day(s) of the week, and consequently how they will make sure that they will attain the three components of leisure crafting via their leisure activities. On each one of the following four weekly surveys, participants in the leisure crafting intervention were asked to think back to their self-development of the previous week and reflect on what went well, what went less well and how they would like to improve this next week (see Appendix I for the self-development plan of Week 1 and the self-reflection questions of Weeks 2-5).

Instruments

Respondents of both groups answered the same questions on all five weekly surveys, but participants in the control condition did not see the video, the self-development plan and the self-reflection questions (i.e., they did not receive the intervention). All items followed the formulation “During the previous week…”. Following previous practice and recommendations for preventing respondents’ fatigue effects (Ohly et al., Citation2010), where possible, we used shortened scales for our measures. Where a shortened scale was not available, we selected items (1) on basis of their factor loadings and (2) making sure that the selected items represented all dimensions of the original questionnaire. All items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree.”

Manipulation check

Leisure crafting was measured as a means of a manipulation check with a 6-item shortened version of the leisure crafting questionnaire by Petrou and Bakker (Citation2016; alpha ranged from .85 to .93 over the five weeks). The item selection can be found in Appendix II.

Context-free outcomes

Meaning in life was measured with three items from the “presence” subscale of Steger et al.’s (Citation2006) questionnaire (e.g., “… I had a good sense of what makes my life meaningful”, alpha ranged from .83 to .90). Need satisfaction was measured with three items from Sheldon et al. (Citation2001; e.g., “… I felt that my choices expressed my ‘true self’”), each one capturing a different human need (for a similar approach, see Zeijen et al., Citation2020); alpha ranged from .59 to .69. Self-efficacy was measured with five items from Schwarzer and Jerusalem’s (Citation1995) questionnaire (e.g., “… no matter what came my way, I was able to handle it”, alpha ranged from .79 to .87). Context-free creativity was measured with a single item from Kaufman and Baer’s (Citation2004) questionnaire (“… I have been creative in my daily life overall”).

Work-related outcomes

Work engagement was measured with six items (e.g., “I felt strong and vigorous while working”) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006; see also, Bakker & Xanthopoulou, Citation2009, for a similar approach); alphas ranged from .90 to .94. Seeking challenges was measured with three items from Petrou et al. (Citation2012; e.g., “… I have asked for more responsibilities”; alphas ranged from .90 to .95). Employee creativity was measured with four items from Miron et al. (Citation2004; e.g., “… I had a lot of creative ideas”; alpha ranged from .85 to .92).

Analytical approach

We used the Mplus software to analyze the data and we conducted multi-group Latent Growth Curve analyses, running a separate model for each observed outcome variable, represented by its respective mean score (see Kroese et al., Citation2013 for a similar approach). For each outcome, we first ran the model separately for each group (intervention and control) to ensure that the models fitted the data well. Finally, to assess the growth (i.e., increase) in all outcome variables across groups, we created the final multi-group model, which calculated the intercept and the slope of the outcome variable for each group, using a linear growth pattern (0-1-2-3-4). To assess the difference between the slopes of the two groups, we calculated the difference between the means of the slopes of each group, and we asked for 95% confidence intervals for intercepts and slopes as well as for the differences between the slopes for the two groups.

Results

Dropout analyses

To assess whether participants who dropped out after the baseline survey (n = 15 in intervention and n = 11 in the control group) differed from those who remained in the study, we conducted t-tests comparing drop-outs with completers on the study outcomes measured at baseline. None of these comparisons were significant.

Measurement models

Even though our main analyses used observed scores, in preliminary analyses, we assessed factorial validity for leisure crafting and for all outcome variables (except the single item of context-free creativity) by conducting multilevel CFA in Mplus. To simplify our models, we conducted analyses separately for non-work-related variables and for work-related outcomes. The 4-factor solution for non-work-related variables that included a different factor for leisure crafting, meaning, self-efficacy and need satisfaction, respectively, had excellent fit to the data, χ2 (227) = 517.43, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04 (within) and .07 (between), and considerably better than a 3-factor solution (combining meaning with need satisfaction), a 2-factor (adding self-efficacy to the previously combined factor) and a 1-factor solution. Similarly, The 3-factor solution for work-related variables that included a different factor for work engagement, seeking challenges and employee creativity had excellent fit to the data, χ2 (124) = 236.90, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .03 (within) and .05 (between), and considerably better than a 2-factor solution (combining work engagement with seeking challenges) and a 1-factor solution.

Randomization checks

We conducted two randomization checks. First, we compared participants in the intervention condition against participants in the control condition on baseline study outcomes, irrespective of study completion (n = 187 in intervention and n = 194 in control group). Analyses revealed that the two groups did not differ significantly on any of the variables, except need satisfaction: Specifically, the intervention group scored lower (M = 5.03) than the control group (M = 5.30); t (298.6) = −2.45, p = .015.

We then repeated the same procedure but for the final sample that was used for analyses (N = 101 in intervention and N = 156 in control group). Analyses revealed that the groups did not differ significantly on any baseline outcome, with two exceptions: The intervention group (M = 5.02) scored lower than the control group (M = 5.32) on need satisfaction, t (182.044) = −2.35, p = .02. Similarly, the intervention group (M = 4.62) scored lower than the control group (M = 5.07) on meaning; t (255) = −2.69, p = .008. To further address these baseline group differences, we decided to repeat our main analyses for two new randomly selected sub-samples, whereby the intervention and the control group have been matched in terms of their baseline levels of need satisfaction and meaning (see later on, section “additional analyses”).

Descriptive statistics and manipulation check

The mean scores of all study variables separately for the two groups can be found in . Before testing our hypotheses, we run multi-group latent growth curve analyses with leisure crafting as the outcome variable. Results (see ) revealed that the growth of leisure crafting over the five weeks was significant for the intervention group and non-significant for the control group. More importantly, the slope for the intervention group was significantly steeper than the slope for the control group. These results seem to suggest that our manipulation was successful.

Table 1. Sample size, mean scores and standard deviations of all study variables for intervention group and control group.

Testing our hypotheses

Looking at the context-free outcome variables of , it can be concluded that the intervention group displayed a significant positive slope in meaning, need satisfaction, self-efficacy, and a non-significant slope on context-free creativity, meaning that participants in the intervention group show an increase in meaning, need satisfaction, and self-efficacy during the intervention period. The control group displayed a non-significant slope for all outcome variables, meaning there was no increase in outcomes during the intervention period. Most importantly, comparisons with confidence intervals revealed that the slope of the intervention group was significantly steeper than the slope of the control group on meaning, need satisfaction, self-efficacy but not context-free creativity. This means that the intervention group experienced greater growth than the control group on meaning, need satisfaction and self-efficacy, providing support to Hypothesis 1a, 1b, 1c, but not to Hypothesis 1d.

Table 2. Multi-group Latent Growth Modeling (LGCM) results for intervention and control group.

Regarding work-related outcomes, the intervention group displayed a significant positive slope for work engagement, seeking challenges, and employee creativity. The control group displayed a positive and significant slope for work engagement and seeking challenges and a negative significant slope for creativity. However, when we compared the slopes of the two groups, the intervention group was found to have a steeper slope than the control group on work engagement and employee creativity and not on seeking challenges. This means that the intervention group experienced greater growth than the control group on work engagement and employee creativity but not seeking challenges, providing support to Hypothesis 2a and 2c but not 2b.

Additional analyses

To address baseline differences between the two groups on meaning and need satisfaction, we conducted Propensity Score Matching using SPSS 27 with the Python 3.0 add-on. We randomly generated two samples: one (n = 101 in experimental and n = 102 in control) where the two groups were equivalent in terms of meaning and one (n = 101 in experimental and n = 99 in control) where the two groups were equivalent in terms of need satisfaction. We then rerun our main analyses. Results were not different when we used the sample that was matched on meaning with meaning as an outcome variable (i.e., the intervention group displayed a significantly steeper slope; estimate = −.08, CI = −.15/-.01). However, when we used the sample matched on need satisfaction with need satisfaction as an outcome, the difference between the slopes of the two groups was no longer significant (estimate = −.07, CI = −.13/.00). Our additional analyses, thus, provide further support to Hypothesis 1a but they fail to provide further support to Hypothesis 1b.

Discussion

The present study hypothesized that an online leisure crafting intervention will result in both context-free and work-related benefits for the participants. Our results confirmed our expectations for meaning in life, self-efficacy, work engagement and employee creativity. Results were not robust for need satisfaction and they were non-significant for seeking challenges and context-free creativity.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first intervention to target Petrou and Bakker’s (Citation2016) leisure crafting conceptualization among employees, increasing our ability for causal inferences. Our results reveal that learning how to enact leisure crafting made participants to, indeed, display higher leisure crafting (i.e., the manipulation check was significant) and also enhanced their potential as humans (e.g., experience of meaning and self-efficacy) and also in their role as an employee (i.e., experience of an engaging and creative working life). This means that leisure crafting is a concept that has both face validity in practice (i.e., people understand it and are able to learn it) and predictive validity (i.e., once they learn it, this actually has an effect on their life). Despite the fact that the intervention was online, without face-to-face contact with a trainer and conducted throughout the challenging COVID-19 times of remote work, its effects were notable. Our intervention shows that employees who are willing to commit and show perseverance in practicing their leisure activities (and perhaps resist temptations to opt for more a more casual approach of leisure activities) find the power to build a more meaningful and more fulfilling life. Our results are in line with prior work addressing active leisure activities as essential tools in improving people’s quality of life (Iwasaki, Citation2007). Similarly, our studies offer empirical validation to life-domain spillover theoretical frameworks (e.g., De Bloom et al., Citation2020; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012). Accordingly, behavior in one life domain (e.g., leisure crafting) enriches another life domain (i.e., heightened employee creativity).

It is worth speculating why our participants experienced an increase in their work-related but not in their context-free creativity. Perhaps the single item that we used to measure context-free creativity (Kaufman & Baer, Citation2004) resembles more creative personality than creative performance. When creativity is domain-relevant (e.g., work-related), it is more specific, and individuals have a frame within which to operate. As such, it could be easier to increase creativity in a certain domain, rather than overall domain-free creativity (Baer, Citation2015), which may need more time to improve.

Furthermore, our participants did not increase their seeking-challenges behaviors over time. One interpretation may have to do with the fact that one’s resources are finite and not abundant (Beal et al., Citation2005) and individuals need to make choices as to how many new challenges they will initiate, otherwise, they may get overwhelmed. In other words, even though active leisure crafters carry over their positivity and creativity to work, they do not necessarily have the time or energy to start new work projects; especially if they already pursue challenging projects in other life domains. An additional interpretation may have to do with the relatively young age and low working hours of our sample. A previous meta-analysis suggests that the lower the tenure and the working hours of employees, the more difficult it becomes to seek new challenging projects at work (Rudolph et al., Citation2017).

Last but not least, our groups of participants displayed baseline differences on need satisfaction and the intervention effect on need satisfaction became non-significant when the two groups were matched on their baseline levels. This means that the results regarding need satisfaction should be interpreted with caution (also because of the low alpha of the need satisfaction scale). This result also suggests that the intervention may be only successful for participants with relatively low levels of need satisfaction (and, thus, sufficient room for improvement). In other words, as participants displayed fairly high need satisfaction levels from the beginning of the study, it is also possible that ceiling effects prevented us from finding results. The result of the intervention on need satisfaction may also be an indication that the effect of the intervention on need satisfaction was not strong enough. Perhaps it could be that in such a short time (i.e., the actual intervention only lasted four weeks) participants can fulfill needs such as autonomy or relatedness, while competence needs more time to be fully attained (see Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016; for a similar discussion point).

Study 2

After conducting our intervention, we aimed to replicate our findings using a different methodology (i.e., a cross-sectional survey study). Study 2 was designed to address correlations between self-reported leisure crafting and all context-free and work-related variables of Study 1 (also self-reported). In addition, it could be that Study 1 may have suffered from common-method bias. Therefore, in Study 2, we aimed to employ additional other-ratings for some of the measured outcomes. In addition to using other-ratings for everyday creativity (i.e., which can be observed by others; Sordia et al., Citation2022), we decided to measure a new variable as a potential context-free outcome of leisure crafting, namely, other-rated subjective well-being. Subjective well-being can be easily observed by others (Lepper, Citation1998) and has been theorized to be a consequence of engagement in leisure activities (Brajša-Žganec et al., Citation2011). Similar to the reasoning of our expectations for all context-free benefits of leisure crafting, we expect that by shaping a more fulfilling and satisfying life, leisure crafters should enhance their overall quality of life and, thus, feel happier (i.e., experience higher subjective meaning of life).

Method

Participants and procedure

Prior to data collection, we obtained permission by the Ethics Committee of Erasmus University Rotterdam (reference: 21-044). Respondents were 195 employees within different occupational sectors in The Netherlands and in Germany, recruited with network sampling by research assistants (Demerouti & Rispens, Citation2014; also see Study 1). Selection criteria were that respondents were based in The Netherlands or in Germany and that they had a paid job for at least two days per week. Out of 379 individuals who were contacted, 234 respondents completed the questionnaire (response rate = 62%). After removing data from 39 participants based in countries outside The Netherlands or Germany, 195 respondents formed the data for the analyses. Participants (77 men and 118 women) were on average 32.5 years old (SD = 13.8). They worked a mean of 33.1 hours (SD = 12.3) per week for an average 6.1 years (SD = 8.5) in occupational sectors, such as healthcare (16%), commerce (12%), education (7%), government (6%), or communications (6%). Most of them worked for an organization (91% vs. 9% were self-employed) and had no managerial position (78% vs. 22% were supervising others). From the 195 participants, 123 found an important other who gave an other-rating about the main respondent. The important others were on average 33.3 years old (SD = 14.7) and they were mainly partner/spouse (54.5%) or friend of the main respondent (24.4%), followed by sibling (7.3%), parent (4.9%), colleague (3.3%), daughter/son (3.3%), or “other” (2.4%).

Five student research assistants recruited participants via their professional and personal/social networks, as well as via social media and via the snowball technique. After they agreed, participants received an e-mail invitation with the link to the online survey and information about the purpose of the study, confidentiality and voluntary participation. Once they gave their informed consent, they proceeded with the survey. Couples of respondents and “important others” who both completed their surveys entered a lottery for 30 gift vouchers worth 20 euro’s each.

Instruments

The same instruments as in Study 1 were used to measure all study variables. In addition, we used 3 items (“energetic”, “enthusiastic”, “inspired”) to measure positive valence/high activation subjective well-being and three items (“at ease”, “satisfied”, “relaxed”) to measure positive valence/low activation subjective well-being; both scales have been validated by Schaufeli and Van Rhenen (Citation2006). Alphas for all scales can be found in .

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations between all study variables of study 2 (N = 195).

Results and discussion

As can be seen in , self-reported leisure crafting correlated positively and significantly with all the self-rated context-free and work-related study variables. In addition, self-rated leisure crafting also correlated positively and significantly with other-rated context-free creativity and other-rated subjective well-being; however, that was the case only for the high-activation and not for the low-activation subscale. Even though the link between leisure activities and well-being has been found with one overall factor of well-being, this was the case in studies using self-reports (e.g., Brajša-Žganec et al., Citation2011). It could be that when well-being is other-rated and needs to be observed by others, the link becomes stronger when it concerns people who are active, thus, influencing others (e.g., “energetic”) rather than people who are in a state of low activation and, thus, keep to themselves (e.g., “satisfied”).

Overarching discussion

Using different methodologies (i.e., intervention and survey study; self-reports and other-ratings), our two studies showcase leisure crafting as a strategy with the potential to lead to happier people and happier employees. Using these different methodologies allowed us to make stronger causal inferences about leisure crafting than previous studies (Abdel Hadi et al., Citation2021; Chen, Citation2020; Hamrick, Citation2022; Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016; Petrou et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the fact that the intervention was conducted in the field ensures ecological validity (i.e., the results can be applied to real-life settings). Focussing only on the outcomes that were cross-validated by both studies, our results show that active leisure crafting leads to more meaning, self-efficacy, work engagement and employee creativity and, thus, that leisure crafters have an overall fulfilling life. These findings provide support to theoretical frameworks and previous empirical findings about if and how crafting different life domains may shape a happy life (De Bloom et al., Citation2020; Mukherjee & Dhar, Citation2023). The findings are also in line with the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) and the spillover framework (e.g., Snir & Harpaz, Citation2002; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012) that suggest that resources generated in one domain can be used to generate other resources and as such lead to positive outcomes in other life domains, such as work.

Although our conceptualization of leisure crafting (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016) was rooted in the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017), and we expected that leisure crafting would lead to the satisfaction of basic needs, the leisure crafting intervention did not show a robust increase in need satisfaction whilst a positive association was found in the cross-sectional study. An explanation could be that the intervention first led to need satisfaction in the leisure domain and was—given the short duration of the intervention—not yet developed into general need satisfaction, which was measured in this study (Milyavskaya et al., Citation2013).

Another notable difference between the two studies is that while the intervention did not improve context-free creativity, leisure crafting was related to context-free creativity that was reported cross-sectionally (self-reported and other-rated). One possible explanation may have to do with the measurement of creativity. That is, if our single item that measures overall context-free creativity is perceived by our respondents as an item representing creative personality (also see discussion of Study 1), it is not surprising that this link is confirmed in a cross-sectional survey and not in a 4-week intervention study. This result may suggest that, generally speaking, active leisure crafters are perceived (by themselves and by others) as creative individuals. But this creative personality perhaps cannot change within only four weeks’ time.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Our studies are not without limitations. First, we compared an intervention to a no-intervention control group in Study 1. We, thus, cannot rule out the possibility that the found effects are due to nonspecific intervention effects (i.e., factors other than the leisure intervention itself), such as placebo effects and other research participation effects (McCambridge et al., Citation2014). It is possible that participants improve simply because they are contacted, consented and measured. Given that control participants did not show an increase in most study outcomes over time, we think this issue did not seriously impact our findings. However, knowing that one receives a potentially effective intervention could have contributed to the reported effects. Therefore, we suggest that future research incorporates a placebo intervention to rule out the possibility of placebo effects. Second, all variables in Study 1 and most variables in Study 2 were self-reported, which is associated with common-method bias. The other-ratings of Study 2 only partly address this issue.

Another limitation of our research is that young female employees are overrepresented in our samples, especially in our intervention study. It may not be entirely surprising that a leisure-related intervention study attracts mostly female participants, perhaps because women show more intrinsic motivation and learning goal orientation in leisure-skills classes (Anderson & Dixon, Citation2009). However, about half of our participants in Study 1 were working students, meaning that their job was a side-job and not a full-time job. This could suggest that they do not have equal chances to grow at their work, compared to the rest of the respondents. Conversely, one could argue that exactly because their work identity may be less strong, they have more room for improvement. Therefore, results regarding work-related benefits should be interpreted with caution and future research should replicate them among full-time employees. Alternatively, future research with larger samples could split the intervention and experimental groups into smaller groups to test whether the intervention works better for students vs. non-students. Notably though, even if we only focus on context-free outcomes, our intervention did have an effect on meaning in life and self-efficacy, two arguably important and central concepts shaping people’s self-perceptions. Especially throughout the COVID-19 crisis, depression among the youth has been documented as a serious issue (e.g., Courtney et al., Citation2020) and our intervention seems to suggest that leisure activities could potentially work as a remedy for young populations throughout moments of crisis.

Furthermore, in Study 1, we have not analyzed what participants have exactly written in their self-reflection. Because leisure crafting is challenging, we believe that even partially successful leisure crafting attempts are adequate for the intervention effects to occur. However, future research could qualitatively analyze the self-reflection of the participants and incorporate it in the analyses or employ other-ratings to cross-validate the behavior of the participants and for, example, distinguish between leisure crafting and causal leisure behavior that has been displayed by the participants.

Next, the scale reliability for need satisfaction in Study 1 was modest, even though acceptable according to standards advocated by Nunnally (Citation1978). In any case, the overall discussion of our paper has refrained from focusing on the results regarding need satisfaction since those were compromised by the propensity score matching analyses.

As a final note, even though no total lockdowns relating to COVID-19 took place during our research, working from home was the rule rather than the exception in most companies in the Netherlands. Our speculation is that as our intervention produced some of the desired effects in a context of working from home, with limited social contacts and without live contact with an intervention trainer, if the intervention is replicated on-site or at least with a live trainer, it will produce stronger effects. Of course, only future research can test this assumption.

Practical implications

The core idea that we want to communicate to organizations and practitioners is that people are not only employees, parents or hobbyists. Instead, they are active agents operating within and proactively (re)shaping different life domains. While managers may worry that granting employees the autonomy to pursue active hobbies may undermine their work motivation, our results suggest otherwise. The participants of our intervention were all employees with a paid job and they experienced not only a more fulfilling life overall but also a more engaging and creative work life.

Organizations can stimulate leisure crafting among employees in several ways. For example, they can adopt flexible work practices (as to when and where the work can be carried out) so that employees experience the freedom to craft their leisure the way they want. However, in addition to simply allowing or tolerating leisure, another way could be to actively support it. For example, organizations can actively support or finance free-time self-development classes or training of their employees. Or they can implement interventions like the one we tested (either online or face-to-face) or provide training sessions and masterclasses about how leisure crafting can be used by employees in the most optimal ways.

Conclusion

Leisure activities and hobbies are not a luxury; they are a way of life with the potential to offer many benefits to people who practice them. When pursuing hobbies happens in a long-term and committed way (i.e., leisure crafting), this can lead to a fulfilling and meaningful life as well as a creative and engaging work life.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/vxwpz/, DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/VXWPZ

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abdel Hadi, S., Bakker, A. B., & Häusser, J. A. (2021). The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 34(5), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1903447

- Amabile, T. M. (2013). Componential theory of creativity. In E. H. Kessler (Ed.), Encyclopedia of management theory (pp. 134–139). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452276090.n42

- Anderson, D. M., & Dixon, A. W. (2009). Winning isn’t everything: Goal orientation and gender differences in university leisure-skills classes. Recreational Sports Journal, 33(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1123/rsj.33.1.54

- Baer, J. (2015). The importance of domain-specific expertise in creativity. Roeper Review, 37(3), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2015.1047480

- Bailey, A. W., & Fernando, I. K. (2012). Routine and project-based leisure, happiness, and meaning in life. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2012.11950259

- Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2009). The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor–partner interdependence model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1562–1571. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017525

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

- Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1054–1068. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1054

- Bollimbala, A., James, P. S., & Ganguli, S. (2021). Impact of physical activity on an individual’s creativity: A day-level analysis. The American Journal of Psychology, 134(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.134.1.0093

- Brajša-Žganec, A., Merkaš, M., & Šverko, I. (2011). Quality of life and leisure activities: How do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 102(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/sI1205-010-9724-2

- Chen, I. S. (2020). Turning home boredom during the outbreak of COVID-19 into thriving at home and career self-management: The role of online leisure crafting. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(11), 3645–3663. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2020-0580

- Clark, S. C. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

- Courtney, D., Watson, P., Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B. H., & Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: Challenges and opportunities. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 65(10), 688–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720935646

- Davis, L. N., Davis, J. D., & Hoisl, K. (2014). Spanning the home/work creative space: Leisure time, hobbies and organizational creativity. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2014, p. 13376). Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2014.13376abstract

- De Bloom, J., Vaziri, H., Tay, L., & Kujanpää, M. (2020). An identity-based integrative needs model of crafting: Crafting within and across life domains. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(12), 1423–1446. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000495

- Delle Fave, A., & Massimini, F. (2003). Optimal experience in work and leisure among teachers and physicians: Individual and bio‐cultural implications. Leisure Studies, 22(4), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360310001594122

- Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2014). Improving the image of student‐recruited samples: A commentary. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12048

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 266–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.07.001

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., Hewett, R., Haun, V., De Gieter, S., Rodríguez-Sánchez, A., & Skakon, J. (2020). From job crafting to home crafting: A daily diary study among six European countries. Human Relations, 73(7), 1010–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719848809

- Epton, T., Currie, S., & Armitage, C. J. (2017). Unique effects of setting goals on behavior change: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12), 1182–1198. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000260

- Fan, X. (2003). Power of latent growth modeling for detecting group differences in linear growth trajectory parameters. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10(3), 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_3

- Godbey, G., Crawford, D. W., & Shen, X. S. (2010). Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. Journal of Leisure Research, 42(1), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2010.11950197

- Guest, D. E. (2002). Perspectives on the study of work-life balance. Social Science Information, 41(2), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018402041002005

- Hamrick, A. B. (2022). Stress [ed] out, leisure in: The role of leisure crafting in facilitating entrepreneurs’ work stressor—creativity relationship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 18, e00329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00329

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Iwasaki, Y. (2007). Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: What are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life? Social Indicators Research, 82(2), 233–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9032-z

- Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2004). Sure, I’m creative—But not in mathematics!: Self-reported creativity in diverse domains. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 22(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.2190/26HQ-VHE8-GTLN-BJJM

- Kersten-van Dijk, E. T., Westerink, J. H., Beute, F., & IJsselsteijn, W. A. (2017). Personal informatics, self-insight, and behavior change: A critical review of current literature. Human–Computer Interaction, 32(5-6), 268–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2016.1276456

- Kim, J., & Shin, W. (2014). How to do random allocation (randomization). Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery, 6(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2014.6.1.103

- Kristensen, T. S. (2005). Intervention studies in occupational epidemiology. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(3), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2004.016097

- Kroese, F. M., Adriaanse, M. A., Vinkers, C. D., Van de Schoot, R., & De Ridder, D. T. (2013). The effectiveness of a proactive coping intervention targeting self-management in diabetes patients. Psychology & Health, 29(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.841911

- Lepper, H. S. (1998). Use of other-reports to validate subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 44(3), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006872027638

- McCambridge, J., Kypri, K., & Elbourne, D. (2014). Research participation effects: A skeleton in the methodological cupboard. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(8), 845–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.002

- Milyavskaya, M., Philippe, F. L., & Koestner, R. (2013). Psychological need satisfaction across levels of experience: Their organization and contribution to general well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.10.013

- Miron, E., Erez, M., & Naveh, E. (2004). Do personal characteristics and cultural values that promote innovation, quality, and efficiency compete or complement each other? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(2), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.237

- Mojza, E. J., Sonnentag, S., & Bornemann, C. (2011). Volunteer work as a valuable leisure‐time activity: A day‐level study on volunteer work, non‐work experiences, and well‐being at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910X485737

- Mukherjee, T., & Dhar, R. L. (2023). Unraveling the black box of job crafting interventions: A systematic literature review and future prospects. Applied Psychology, 72(3), 1270–1323. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12434

- Ng, J. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Duda, J. L., & Williams, G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(4), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447309

- Nijstad, B. A., De Dreu, C. K., Rietzschel, E. F., & Baas, M. (2010). The dual pathway to creativity model: Creative ideation as a function of flexibility and persistence. European Review of Social Psychology, 21(1), 34–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463281003765323

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000009

- Perry-Smith, J. E. (2014). Social network ties beyond nonredundancy: An experimental investigation of the effect of knowledge content and tie strength on creativity. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(5), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036385

- Petrou, P. (2021a, February 5). Training: Self-development via hobbies [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LXpTxa6TwXE

- Petrou, P. (2021b, February 5). Training: Self-development via hobbies [in Dutch, Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/RB7vAV3GygA

- Petrou, P., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Crafting one’s leisure time in response to high job strain. Human Relations, 69(2), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715590453

- Petrou, P., Bakker, A. B., & van den Heuvel, M. (2017). Weekly job crafting and leisure crafting: Implications for meaning‐making and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12160

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1783

- Radaelli, G., Guerci, M., Cirella, S., & Shani, A. B. (2014). Intervention research as management research in practice: Learning from a case in the fashion design industry. British Journal of Management, 25(2), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00844.x

- Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., Panzer, K., & King, S. N. (2002). Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069352

- Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford.

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2006). Over de rol van positieve en negatieve emoties bij het welbevinden van managers: Een studie met de Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS) [About the role of positive and negative emotions in managers’ well-being: A study using the Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS)]. Gedrag & Organisatie, 19(4), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.5117/2006.019.004.002

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-Nelson.

- Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1037//O022-3514.80.2.325

- Snir, R., & Harpaz, I. (2002). Work-leisure relations: Leisure orientation and the meaning of work. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(2), 178–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2002.11949968

- Sordia, N., Jauk, E., & Martskvishvili, K. (2022). Beyond the big personality dimensions: Consistency and specificity of associations between the Dark Triad traits and creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 16(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000346

- Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. The Pacific Sociological Review, 25(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388726

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

- Stenseng, F., & Phelps, J. (2013). Leisure and life satisfaction: The role of passion and life domain outcomes. World Leisure Journal, 55(4), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2013.836558

- Tang, M., Wang, D., & Guerrien, A. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis on basic psychological need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in later life: Contributions of self-determination theory. PsyCh Journal, 9(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.293

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. The American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027974

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Trnka, R., Zahradnik, M., & Kuška, M. (2016). Emotional creativity and real-life involvement in different types of creative leisure activities. Creativity Research Journal, 28(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2016.1195653

- Trougakos, J. P., Chawla, N., & McCarthy, J. M. (2020). Working in a pandemic: Exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1234–1245. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000739

- Tsaur, S. H., Yen, C. H., Yang, M. C., & Yen, H. H. (2023). Leisure crafting: Scale development and validation. Leisure Sciences, 45(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1783728

- Wang, A. Y. (2012). Exploring the relationship of creative thinking to reading and writing. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2011.09.001

- Wei, X., Huang, S., Stodolska, M., & Yu, Y. (2015). Leisure time, leisure activities, and happiness in China: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(5), 556–576. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2015-v47-i5-6120

- Zeijen, M. E., Petrou, P., Bakker, A. B., & Gelderen, B. R. (2020). Dyadic support exchange and work engagement: An episodic test and expansion of self‐determination theory. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(3), 687–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12311

Appendix I

Self-development plan (Week 1)

Please, answer the following questions so that you create your own “self-development” plan through leisure activities.

Which activity or activities do you plan to focus on during the following four weeks?

Which days of the week, what time and for how long do you plan to perform these activities?

How will you make sure that doing these activities will lead to the first desired self-development outcome that you have learned about today in your online training video? Namely, goal-setting?

[…] Namely, learning?

[…] Namely, human connection?

Self-development plan & self-reflection (Weeks 2-4)

Reflect on your personal development plan

What activities did you perform, when and for how long?

What went well? What did you learn and what were the things that you consider to be positive outcomes?

What went less well?

(only in Weeks 2-3) How do you plan to improve this next week?

Appendix II

The shortened leisure crafting scale

During the previous week….

… I tried to find challenging activities outside of work.

… I tried to increase my skills through leisure activities.

… I tried to increase my learning experiences through leisure activities.

… I tried to set myself new goals to achieve through leisure activities.

… I looked for inspiration from others through my leisure activities.

… I looked for new experiences through leisure activities to keep myself mentally stimulated.