Abstract

This study examined the interrelationships among parental play belief, household playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese children. Participants were teachers and parents of 140 children (52.1% boys, mean age = 4.35). Parents reported their parental play belief and their child’s playfulness through a questionnaire, while teachers reported children’s kindergarten play behaviors and social competence. Multiple regressions and path analytic model revealed that children’s kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors were correlates of their social competence; and that children’s social spontaneity, social play, and reticent behaviors act as potential mediators underlying the relationship between parental play belief and social competence. These findings suggest that parents holding positive play belief may promote their child’s social competence by shaping children’s household playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors. They also highlight the utility of promoting parental play belief, children’s social spontaneity, and kindergarten social play.

Play is the prime activity for children to acquire and exercise their competencies in establishing positive interpersonal relationships (e.g., Bodrova & Leong, Citation2018; Vygotsky, Citation1967) and, thus, extensive research has examined how play impacts children’s social competence (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2015; Denham & Brown, Citation2010; Eggum-Wilkens et al., Citation2014; Fung & Cheng, Citation2017; Lindsey & Colwell, Citation2013; Rentzou, Citation2014; Veiga et al., Citation2022). Parents’ belief in the roles of play in child development (i.e., parental play belief; Hyun et al., Citation2021) was suggested as a factor impacting household play environment and interaction (Lin & Li, Citation2018). Playfulness, defined as one’s tendency to take part in playful circumstances (Barnett, Citation1991; Lieberman, Citation1977), was suggested as another factor that governs children’s play behaviors and shapes their social development (Barnett, Citation2018). However, prior research examining the links between children’s playfulness, play behaviors, and social competence yielded inconsistent findings (e.g., Barnett, Citation2018; Fink et al., Citation2020; Fung & Chung, Citation2022). Fung and Chung (Citation2022) reported that children’s parent-rated playfulness negatively predicted their teacher-rated peer problems. Although Fink et al. (Citation2020) reported that playfulness was a positive predictor of children’s teacher-rated peer play interaction, playfulness was unrelated to their internalizing problems or peer preference in the kindergarten context. Similarly, Barnett (Citation2018) revealed that kindergarten children’s playfulness was unrelated to their teacher-rated social competence at grade one. Research examining their interrelationships with consideration of parental play belief is even rarer.

Kindergarten is an important context that determines children’s early social development. Children have different social needs to integrate into the kindergarten environment (e.g., coordinating peer play and participating in group learning activities) (Beaty, Citation2014). Although playfulness may govern children’s play characteristics across different contexts (Barnett, Citation1991), children are facing a different set of supplemental (e.g., additional playmates) and constraining (e.g., the need to comply with class schedule) factors in the school context. Thus, the applicability of household playfulness in predicting children’s kindergarten play behaviors remains an open question, and little attempt has been made to examine how these characteristics and behaviors jointly relate to children’s social competence.

Parents, teachers, and officials of the Education Bureau in Hong Kong are aware of the importance of play to children’s early development (Bautista et al., Citation2021). The employment of play in Hong Kong early childhood education can be traced back to the curriculum guides in 1982 (Fung & Cheng, Citation2012). The latest Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide (Curriculum Development Council of HKSARG, Citation2017) further upholds the use of the play-based approach and specifically emphasizes the role of free play in nurturing children’s balanced development and promoting their free exploration and expression. Despite the continuous effort to encourage the pedagogy of play, different stakeholders are ambivalent about the effectiveness of play in promoting children’s learning and development (Bautista et al., Citation2021; Fung & Cheng, Citation2012). Particularly, early years practitioners struggle to convince parents of the value of play in fostering children’s school readiness (Bautista et al., Citation2021), while didactic and structured teaching is still prevalent in kindergarten classrooms (Keung & Fung, Citation2021). Local research validating the efficacy of play in early childhood education is vital to altering the deep-rooted beliefs in academic readiness (Bautista et al., Citation2021). The present study aimed to address the mentioned gaps by investigating the interrelationships among parental play belief, playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence in a sample of Hong Kong Chinese children.

Parental play belief, play, and social competence

Parental play belief can impact children’s household play experiences in different ways. Family values and expectations (e.g., academic focus; Hyun et al., Citation2021) can hinder children’s household play experience. Conversely, parents who value the roles of play are more likely to provide varied play materials and opportunities and engage in parent-child play (Lin & Li, Citation2018). Moreover, these parents tend to endorse children’s play preferences and ideas (Fung & Chung, Citation2022). Therefore, by establishing a household context that promotes quality play, parental play belief may nurture children’s affinities with various play styles (e.g., playfulness). These characteristics may also be manifested in the kindergarten context and collectively shape children’s social development. Specifically, higher affinities with peer play offer children increased opportunities to practise their prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping, sharing, cooperating, turn-taking), perspective taking, impulse control, conflict resolution, and communicative skills (Fung & Chung, Citation2023). These competencies are fundamental to children’s social competence (Campbell et al., Citation2016; Fung & Cheng, Citation2017). Despite the sound theoretical foundation connecting parental play belief with children’s play and social competence, limited research has examined their interconnectedness. Lin and Yawkey (Citation2014) reported a positive relationship between Taiwanese parents’ play belief and their child’s social competence, but the results neither accounted for any factors reflective of children’s play nor explored the potential mechanism underlying the relationship. The current study extended the previous work by including children’s playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors as possible mediators in the further examination of the relationship between parental play belief and social competence.

Parental play belief, playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence

According to Lieberman’s (Citation1977) framework, playfulness represents children’s style of play, which reflects their personality and orientation. Its indicators include physical spontaneity (activity level and physical dexterity), social spontaneity (fondness for social communication and peer play), cognitive spontaneity (likeliness to have imaginative and creative ideas), manifest joy (levels of exuberance and positive emotions), and sense of humor (tendency to create and enjoy funny atmosphere). Barnett (Citation1991, Citation2018) further validated and confirmed these five aspects representing children’s playfulness. In the present study, children’s playfulness was conceptualized by referring to Lieberman’s (Citation1977) model. Prior research has revealed several precursors of children’s playfulness, including childbirth order (Keleş & Yurt, Citation2017), overexcitabilities (Fung & Chung, Citation2021), household play materials (Bulgarelli et al., Citation2018), and parental play supportiveness (Fung & Chung, Citation2022). Parental play belief may shape parents’ behaviors (e.g., higher autonomy in play or increased spending on play materials) and, in turn, change the level of parental play supportiveness and household play environment (Hyun et al., Citation2021; Lin & Li, Citation2018).

Although playfulness characterizes children’s play across situations (Barnett, Citation1991), contextual factors may influence the expression of playfulness, particularly in the kindergarten context. Considering the importance of peer play in promoting early social development, Parten (Citation1932) categorized kindergarten children’s play behaviors according to the level of social participation. Drawing on this classic paper on early play behaviors (Parten, Citation1932), a line of research has examined kindergarten play by classifying children’s behaviors as social play (peer interactive play with pretense), rough play (rough-and-tumble or play fighting), solitary-active play (pretend play by oneself), solitary-passive play (construction or exploration by oneself), and reticent behaviors (e.g., Coplan et al., Citation2001; Coplan & Armer, Citation2007; Leung, Citation2017). Reticent behaviors are commonly defined as children’s unoccupied and onlooking acts during play (Coplan & Armer, Citation2007; Parten, Citation1932), and these behaviors were negatively correlated with their social competence (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2015; Choo et al., Citation2012; Coplan et al., Citation2001). Although unoccupied behavior (e.g., staring or wandering aimlessly) may be uncommon among kindergarteners, Parten (Citation1932) revealed that children could display a variety of social participation, including onlooker behaviors (e.g., watching, listening, or talking to players without entering), irrespective of their age. On the contrary, the two peer play types (i.e., social play and rough play) are specifically linked with children’s positive social development (e.g., Fung & Cheng, Citation2017; StGeorge & Freeman, Citation2017).

Kindergarten social play, such as sociodramatic play, involves multiple players and various communicative (e.g., sharing and planning, defining rules and situations, assigning roles and materials) and symbolic skills (e.g., object substitution, pretense actions) (Bodrova & Leong, Citation2018; Fung & Cheng, Citation2017). Kindergarten rough play reflects the voluntary play fighting (e.g., kicking, grappling, wrestling) among peers that involves many physical actions and positive affect (Fletcher et al., Citation2013; Pellis & Pellis, Citation2007). Therefore, children with higher social and cognitive spontaneity are more likely to take part in kindergarten social play, whereas those with higher physical spontaneity may display more kindergarten rough play (Fung & Chung, Citation2021). However, certain environmental constraints may influence how children’s playfulness is represented in kindergarten. For example, children with high cognitive spontaneity are more likely to use unusual objects to invent their play (Barnett, Citation2018; Fung et al., Citation2021), but a structured classroom with a tight schedule and mainly theme-related materials (e.g., Hong Kong; Bautista et al., Citation2021) may limit how their imagination and creativity are observed in kindergarten social play. Likewise, children with high physical spontaneity may not be allowed to engage in kindergarten rough play due to teachers’ need to maintain class order. Although kindergarten-age children may or may not display similar styles of play at home and school (Berndt & Bulleit, Citation1985), very limited research has investigated their relationships.

Further complicating the situation, prior research investigating the interrelationships among playfulness, play behaviors, and social competence has yielded inconsistent findings. For example, Fung and Chung (Citation2022) revealed a negative relationship between parent-reported playfulness (Children’s Playfulness Scale; Barnett, Citation1991) and teacher-rated peer problems (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Goodman, Citation1997) among kindergarten children, whereas Barnett (Citation2018) and Fink et al. (Citation2020) reported that children’s playfulness (Children’s Playfulness Scale or Child self-reported playfulness) was unrelated to teacher-rated social competence (Social Competence subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children; Harter, Citation1985) or peer-rated social preference (Coie et al., Citation1982). Leung (Citation2017) reported that children’s social play was negatively related to their disruptive and withdrawn behaviors, but Rentzou (Citation2014) indicated a nonsignificant relationship. Separately, the evolutionary account of dominance hierarchy (Fletcher et al., Citation2013; Pellis & Pellis, Citation2007) theorized that children engaging in more rough play could develop better skills in recognizing dominant behavioral cues and, thus, avoid social struggle. Anderson et al. (Citation2019) also reported that father-child rough play negatively predicted children’s future aggressive behaviors. Moreover, a review conducted by StGeorge and Freeman (Citation2017) reported a positive link between father-child rough play and children’s social competence. Despite the theoretical (e.g., dominance hierarchy; Fletcher et al., Citation2013; Pellis & Pellis, Citation2007) and empirical basis (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2019; StGeorge & Freeman, Citation2017) supporting the positive role of rough play in children’s early social development, contradictory findings were also reported (e.g., Paquette et al., Citation2003; Veiga et al., Citation2022). For instance, Veiga et al. (Citation2022) reported a positive link between rough play and children’s physical aggression at home and school.

The inconsistent findings may be attributed to different reasons. First, this line of research examined the relationship between play behaviors and social competence without considering various play types (e.g., social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors) simultaneously. Another possible reason is the variation in children’s play styles across the home and school contexts. Therefore, a comprehensive examination of the interrelationships among playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence, considering their multidimensional nature, is warranted. To our best knowledge, the present study is the first to examine their interconnectedness with the consideration of multiple aspects of playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and parental play belief as the antecedent to examine its direct and indirect relationships with social competence. Findings from this study not only shed light on the inconsistent findings in relation to children’s playfulness, play behaviors, and social competence but also address parents’ and teachers’ ambivalence about the efficacy of play in supporting children’s formal school transition (Bautista et al., Citation2021; Fung & Cheng, Citation2012).

Theoretical framework

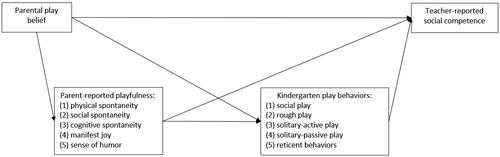

Grounded on the developmental theories emphasizing the importance of play (Bodrova & Leong, Citation2018; Vygotsky, Citation1967), this study tested a conceptual framework contending how parental play belief would shape children’s playfulness, which would, in turn, direct their kindergarten play behaviors and social competence (). Despite previous evidence revealing a positive relationship between parental play belief and children’s social competence (Lin & Yawkey, Citation2014), more recent research demonstrated this association might be mediated through playfulness (Fung & Chung, Citation2022). Specifically, parental play belief was positively associated with both parent-rated and teacher-rated social competence of kindergarten children after controlling different socioeconomic factors (Lin & Yawkey, Citation2014). Nevertheless, the direct relationship between parents’ supportiveness on household play and teacher-rated social competence was nonsignificant after considering children’s playfulness as the underlying process (Fung & Chung, Citation2022). These results point to the possible indirect relationship between parental play belief, children’s playfulness, and social competence.

The present study

In this study, playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors are expected to mediate the relationship between parental play belief and social competence. To develop an understanding of how different aspects of playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors would be associated, five aspects of playfulness (i.e., physical spontaneity, social spontaneity, cognitive spontaneity, manifest joy, and sense of humor) and five types of kindergarten play behaviors (i.e., social play, rough play, solitary-active play, solitary-passive play, and reticent behaviors) were included in determining their relationships. We also examined the relationship between the five types of kindergarten play behaviors and children’s social competence. The findings potentially inform how parental play belief would shape children’s playfulness, how playfulness would be shown in kindergarten, and how these factors collectively predict social competence.

Considering the specific role of peer interaction in early social development (Beaty, Citation2014; Fung & Cheng, Citation2017), the hypotheses of the present study were formulated by focusing on two specific types of kindergarten peer play activities, namely social play and rough play, and the relevant aspects of playfulness (i.e., social, cognitive, and physical spontaneity) (Fung & Chung, Citation2021). Based on the literature reviewed (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2019; Barnett, Citation2018; Fung & Chung, Citation2022; Leung, Citation2017; Lin & Li, Citation2018), nine hypotheses were developed, as shown below:

Hypothesis 1: the relationships of parental play belief with parent-reported physical spontaneity, social spontaneity, and cognitive spontaneity would be positive and significant;

Hypothesis 2: the relationships of parent-reported cognitive spontaneity and social spontaneity with teacher-reported social play would be positive and significant;

Hypothesis 3: the relationship between parent-reported physical spontaneity and teacher-reported rough play would be positively significant;

Hypothesis 4: the relationships between teacher-reported social play and rough play with social competence would be positive and significant;

Hypothesis 5: the direct relationships of parental play belief with kindergarten social play and rough play would be nonsignificant;

Hypothesis 6: the direct relationship between parental play belief and teacher-reported social competence would be nonsignificant;

Hypothesis 7: the direct relationships of parent-reported social spontaneity, cognitive spontaneity, and physical spontaneity with teacher-reported social competence would be nonsignificant;

Hypothesis 8: the indirect relationship between parental play belief and teacher-reported social competence via parent-reported cognitive spontaneity, social spontaneity, and teacher-reported social play would be positive and significant;

Hypothesis 9: the indirect relationship between parental play belief and teacher-reported social competence via parent-reported physical spontaneity and teacher-reported rough play would be positive and significant.

Together, the nine hypotheses describe the proposed relationships between parental play belief and children’s social competence, mediated by children’s household playfulness (i.e., cognitive and social spontaneity or physical spontaneity) and the corresponding kindergarten play behaviors (i.e., social play or rough play). In other words, the potential influence of parental play belief on social competence is not direct but transmitted through children’s playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were 140 parents (125 mothers, 15 fathers) and 22 teachers (all females) of 140 children (52.1% male, mean age = 4.35) from a local kindergarten located in Hong Kong, China. Kindergarten programs in Hong Kong are usually for three years: K1 (3 to 4 years), K2 (4 to 5 years), and K3 (5 to 6 years). In this study, 55 children were at K1, 44 were at K2, and 41 were at K3. 58% of the children were the first child in the family; 41% of them had elder siblings, whereas 26% of them had younger siblings. For parental age, 79% were between 31 and 40, and 16% were between 41 and 50. For parental education, 71% completed college or above, and 29% completed secondary school. Over 80% of the teachers obtained a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and had more than four years of teaching experience ().

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

Procedure

Ethics approval and written consent were given by the ethics review board of the respective university and the principal of the participating kindergarten, respectively. Informed consent and questionnaire forms were later sent to the parents through the kindergarten to invite their participation. Parents returned the consent and questionnaire to report their parental play belief and their child’s playfulness, and the class teachers of the participating children were then invited to join this study. Participating teachers reported their student’s kindergarten play behaviors and social competence. All questionnaires could be completed in 10 minutes.

Measures

Parental play belief

Parental play belief was assessed by the play support subscale of the Parent Play Belief Scale (Fogle & Mendez, Citation2006), which was employed in research with kindergarten children (LaForett & Mendez, Citation2017) and among Chinese parents (Hyun et al., Citation2021). Parents rated the 17 items (e.g., Play helps my child learn to express his or her feelings, Play can help my child develop better thinking abilities) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The average score represented parental play belief.

Household playfulness

Children’s household playfulness was assessed by the Children’s Playfulness Scale (Barnett, Citation1991), which was widely employed in local and international research (e.g., Barnett, Citation2018; Fung & Chung, Citation2022; Keleş & Yurt, Citation2017). The scale contained 23 items under five subscales: physical spontaneity (four items; e.g., The child runs (skips, hops, jumps) a lot in play), social spontaneity (five items; e.g., The child assumes a leadership role when playing with others), cognitive spontaneity (four items; e.g., The child invents own games to play), manifest joy (five items; e.g., The child demonstrates exuberance during play), and sense of humor (five items; e.g., The child gently teases others while at play). Parents rated the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all like) to 5 (exactly like). The average scores of the five subscales represented children’s corresponding aspects of playfulness.

Kindergarten play behaviors

Children’s kindergarten play behaviors were assessed by the Preschool Play Behavior Scale (Coplan et al., Citation1994), which was locally validated with adequate reliability and validity (Leung, Citation2017). The scale contained 18 items under 5 subscales: social play (six items; e.g., Plays make-believe with other children), rough play (two items; e.g., Plays rough-and-tumble with other children), solitary-active play (two items; e.g., Engages in pretend play by himself/herself), solitary-passive play (four items; e.g., Plays alone, building things with blocks and/or other toys), and reticent behaviors (four items; e.g., Wanders around aimlessly). Teachers rated the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The average scores of the five subscales represented children’s corresponding types of kindergarten play behavior.

Social competence

Children’s social competence was assessed by the prosocial, peer problems, and conduct problems subscales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Citation1997), which was employed in local research (Li et al., Citation2019) with adequate reliability and validity (e.g., Du et al., Citation2008; Lai et al., Citation2010). The prosocial (e.g., Shares readily with other children), peer problems (e.g., Rather solitary, tends to play alone), and conduct problems (e.g., Often has temper tantrums or hot tempers) subscales each contained five items. Teachers rated the items on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 3 (certainly true), and the coding was reversed where appropriate such that a higher score represents better social competence. The average score of the three subscales represented children’s social competence.

Data analysis

Correlations among the study variables were first examined. Considering the multidimensionality yet interconnectedness of playfulness and play behaviors, multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine (i) how different aspects of playfulness collectively predicted children’s kindergarten play behaviors and (ii) how various kindergarten play behaviors jointly predicted children’s social competence. The identified correlates were further subjected to a path analysis to explore the possible indirect relationships of parental play belief with children’s playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence, with parental education, child age, gender, and birth order statistically controlled. The path model was estimated with the lavaan package (version 0.6-11) in R (version 4.2.0; R Core Team, Citation2022). The lavaan.survey package (version 1.1.3.1; Oberski, Citation2014) was also employed in the path analysis to account for the nested sampling structure of the data (i.e., children clustered within classrooms) (Jackson & Cunningham, Citation2017; Stühmann et al., Citation2020). Goodness of fit was determined by the Chi-square index (non-significant χ2), comparative fit index (CFI ≥ .95), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ .06), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR ≤ .08) (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Results

Preliminary analyses

shows the descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alphas, and bivariate correlations of the study variables. The data were complete with no missing values, and the skewness and kurtosis of all variables fell between plus and minus one. Parental play belief was positively associated with various aspects of playfulness (r = .34 to .51, p < .001) but unrelated to kindergarten play behaviors and social competence. Children’s social play in kindergarten was positively related to social spontaneity (r = .28, p < .001) and manifest joy (r = .17, p < .05). In contrast, their reticent behaviors were negatively associated with social spontaneity (r = −.31, p < .001), sense of humor (r = −.21, p < .05), and physical spontaneity (r = −.17, p < .05). Moreover, children’s solitary-passive and rough play were significantly correlated with their cognitive spontaneity (r = −.19, p < .05) and social spontaneity (r = .20, p < .05), respectively. Further, children’s social competence was significantly related to their reticent behaviors (r = −.50, p < .001) as well as their social (r = .40, p < .001), solitary-passive (r = −.28, p < .001), and solitary-active (r = −.27, p < .001) play. Different aspects of playfulness (r = .34 to .64, p < .001) and various kindergarten play behaviors (r = −.19 to .64, p < .05) were significantly associated with each other. Therefore, multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate their distinctive relationships.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and bivariate correlations of study variables.

reveals the multiple regression models predicting children’s kindergarten play behaviors from playfulness. Overall, children’s playfulness significantly predicted their social play (F = 2.52, p < .05, R2 = .09) and reticent behaviors (F = 3.25, p < .01, R2 = .11). In particular, social spontaneity emerged as the only significant predictor of social play (β = .36, SE = .13, p < .01) and reticent behaviors (β = −.33, SE = .12, p < .01). shows the multiple regression model predicting children’s social competence from different kindergarten play behaviors (F = 14.64, p < .001, R2 = .35). Children’s social play (β = .16, SE = .04, p < .001), rough play (β = −.10, SE = .03, p < .001), and reticent behaviors (β = −.14, SE = .04, p < .001) appeared as the significant predictors of social competence. Taken together, children’s social spontaneity and their kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors were included in a path analytic model to explore their possible mediating roles in the relationship between parental play belief and social competence.

Table 3. Multiple regressions predicting children’s kindergarten play behaviors from parent-reported playfulness.

Table 4. Multiple regression predicting children’s teacher-reported social competence from kindergarten play behaviors.

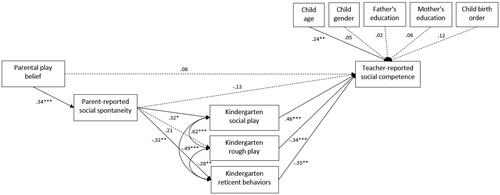

Path model for predicting social competence

presents the path model for predicting social competence from parental play belief, social spontaneity, kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors controlling for parental education, child age, gender, and birth order. The path model fits the data well: χ2 (df = 20, N = 140) = 26.46, p = .15, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI: .00, .10), SRMR = .06, R2 Social play = .09, R2 Rough play = .04, R2 Reticent behaviors = .10, R2 Social competence = .40. The three types of kindergarten play behaviors were significantly correlated (r = −.28 to .62, p < .01).

Figure 2. Path model for predicting social competence from parental play belief, social spontaneity, kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors controlling for parental education, child age, gender, and birth order. Standardized coefficients are reported. Solid paths are statistically significant. Dashed paths are non-significant. The direct relationships of parental play belief with various kindergarten play behaviors, which were all non-significant, were modeled but not displayed for clarity. * p <.05; ** p <.01; *** p <.001. Fit indices: χ2 (df = 20, N = 140) = 26.46, p =.15, CFI =.97, RMSEA =.05 (90% CI:.00,.10), SRMR =.06, R2 social play =.09, R2 rough play =.04, R2 reticent behaviors =.10, R2 social competence =.40.

The direct relationship of parental play belief with social spontaneity was positive and significant (β = .34, SE = .08, p < .001), whereas those with kindergarten play behaviors and social competence were non-significant. The direct relations of social spontaneity with kindergarten social play (β = .32, SE = .16, p < .05) and reticent behaviors (β = −.32, SE = .12, p < .01) were significant. In contrast, those with rough play and teacher-reported social competence were non-significant. The direct links from kindergarten social play (β = .46, SE = .04, p < .001), rough play (β = −.34, SE = .02, p < .001), and reticent behaviors (β = −.34, SE = .05, p < .01) to social competence were all significant. The indirect relationships of parental play belief with kindergarten social play (βind = .11, p < .05, 95% CI = [.02, .31]) and reticent behaviors (βind = −.11, p < .05, 95% CI = [-.28, −.04]) as mediated through social spontaneity were significant, but the one with rough play was non-significant. On the other hand, the indirect relationships between social spontaneity and teacher-reported social competence via kindergarten social play (βind = .15, p < .05, 95% CI = [.01, .14]) and reticent behaviors (βind = .11, p < .01, 95% CI = [.01, .09]) were both significant, but not the one via rough play. Further serial mediation analyses revealed that the indirect relationship between parental play belief, social spontaneity, and social competence as mediated through reticent behaviors (βind = .04, p < .05, 95% CI = [.01, .04]) was significant, but those via social play (at a trend level, βind = .05, p = .08, 95% CI = [-.01, .06]) and rough play (βind = −.02, p = .17, 95% CI = [-.03, .01]) did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

This study investigated the interrelationships among parental play belief, playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence of Hong Kong Chinese children. The results highlight children’s kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors as independent correlates of their social competence. The findings also underscore the indirect relationships between parental play belief and social competence as mediated through children’s social spontaneity, social play, and reticent behaviors. These results extend the existing studies (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2019; Barnett, Citation2018; Fung & Chung, Citation2022; Leung, Citation2017; Lin & Li, Citation2018) by suggesting how parental belief in the importance of play in early development may shape children’s social competence and revealing how children’s playfulness in the household context was translated into their kindergarten play behaviors.

Relationships among parental play belief, playfulness, and kindergarten play behaviors

Aligning with Hypothesis 1, parental play belief was positively correlated with children’s physical, social, and cognitive spontaneity (). Parents who value the role of play in early development are more likely to provide play opportunities and materials, endorse children’s play choices, and engage in household play (Hyun et al., Citation2021; Lin & Li, Citation2018). These factors can nurture children’s playfulness (Bulgarelli et al., Citation2018; Fung & Chung, Citation2022). Nevertheless, with all aspects of playfulness considered simultaneously, only social spontaneity significantly predicted children’s kindergarten social play and reticent behaviors (). The findings aligned with previous evidence suggesting that social play and reticent behaviors are often perceived as the two extremes of the kindergarten play continuum that children’s social spontaneity may impact (e.g., Coplan et al., Citation2001; Coplan & Armer, Citation2007).

Partially consistent with Hypothesis 2, children’s social spontaneity, but not their cognitive spontaneity, predicted their kindergarten social play engagement. This finding informs how children express their playfulness in different contexts. Although playfulness represents children’s general play characteristics or styles, children need to adapt to various constraints that may alter their play behaviors (e.g., availability of playmates, play materials, and teachers’ guidance and expectations), particularly in kindergarten. Children with high cognitive spontaneity tend to generate and contribute imaginative ideas to play. However, suppose these children are preoccupied with imaginative ideas but unable to communicate with peers constructively (e.g., rigidly requesting play partners to follow certain ideas). In that case, their behaviors can create social conflicts. For example, Fung and Cheng (Citation2017) reported that the beneficial impact of kindergarten sociodramatic play on social competence might be more salient in girls than in boys, as boys tend to use more aggressive approaches in conflict resolution. This speculation also highlights the importance of social spontaneity as the successful coordination of peer play is one of the predominant social goals of kindergarten children (Beaty, Citation2014). Alternatively, parental ratings on cognitive spontaneity may not align with teachers’ ratings on social play as this category of kindergarten play is characterized by both social and cognitive (i.e., pretense) elements (e.g., Bodrova & Leong, Citation2018; Fung & Cheng, Citation2017). Children’s social spontaneity is more overt and observable through their social interaction. In contrast, children’s cognitive spontaneity, which involves mental processes such as symbolic representation, object substitution, or broad association (Fung et al., Citation2021), is more covert and difficult to observe. Consequently, teachers may be less able to capture the cognitive elements in kindergarten social play, while parent-reported social spontaneity emerged as the only significant predictor.

Contrary to Hypothesis 3, children’s physical spontaneity was unrelated to their kindergarten rough play. Although rough play typically involves many physical actions, children may exhibit their physical spontaneity through other activities such as chasing, climbing, hopping, and jumping that are not necessarily categorized as rough play. Equally likely, children may comply with kindergarten’s rules and regulations and conform to teachers’ supervision such that those with high physical spontaneity may effortfully suppress their tendency to engage in kindergarten rough play. Further, prior research revealed that rough play is more common in European American than Asian families (Roopnarine, Citation2011). Thus, cultural differences in parental endorsement and engagement of rough play may impact how physical spontaneity was manifested in the kindergarten by the current sample of Chinese children.

Children with high social spontaneity not only engaged in more social play but also displayed lower levels of reticent behaviors. Aligning with Parten’s (Citation1932) proposition of kindergarten social play participation, children who are shy or less confident in social situations may use onlooker behaviors such as walking around or standing and watching as a means to gain access to ongoing peer play (Beaty, Citation2014). Perhaps, during activity transition, higher levels of social spontaneity may drive these children to enter group play by using more active approaches like sharing, contributing, or verbally requesting (Beaty, Citation2014), whereas those with lower levels of social spontaneity tend to use more passive onlooking behaviors of hovering, observing, or questioning (Coplan & Armer, Citation2007; Parten, Citation1932). Further studies investigating children’s play behaviors and development should take the nuances of various reticent behaviors into account.

Concurring with Hypothesis 5, the direct links of parental play belief with kindergarten social play, rough play, and reticent behaviors were all nonsignificant. In contrast, the indirect relationships of parental play belief with kindergarten social play and reticent behaviors as mediated through children’s social spontaneity were significant. These results suggested how parental play belief may shape children’s household play characteristics and further translate into their kindergarten play behaviors. Parents who endorse the importance of play tend to take part in household play activities (Fung & Chung, Citation2022; Lin & Li, Citation2018). Possibly, the increased accompaniment and enjoyment associated with interactive household play may especially promote children’s social spontaneity, and this affinity draws them to an increased level of kindergarten social play and a lower level of reticent behaviors. Together, the present results disentangled and contributed to our understanding of the relationships of parental play belief with children’s playfulness and kindergarten play behaviors.

Relationships among parental play belief, playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence

Partially concurring with Hypothesis 4, children’s kindergarten social play positively predicted their social competence. With existing findings (e.g., Fung & Cheng, Citation2017; Gagnon & Nagle, Citation2004; Uren & Stagnitti, Citation2009), social play is a natural and joyful context for children to exercise and develop their social skills and therefore, it is not surprising to find their positive association. Notably, the present results demonstrated that children’s reticent behaviors uniquely and negatively predicted their social competence after controlling for their levels of social play. Children not participating in kindergarten social play may prefer solitary-active or solitary-passive play due to social disinterest or having their own play plan (Coplan & Armer, Citation2007), while these two solitary play types were unrelated to social competence in the present results. In contrast, increased reticent behaviors may have further implications for early social development. Following the argument above, kindergarten children may use passive onlooker behaviors as the approach to enter ongoing peer play, and those who show more reticent behaviors can be regarded as immature players (Parten, Citation1932). These immature players may be interested in peer play, but they were less effective in entering a group, which lowered the opportunities for practising their social skills. However, caution should be taken in this interpretation as it is equally probable that children with higher social competence tend to engage in more social play and display less reticent behaviors.

As expected in Hypotheses 6 and 7, the direct links of parental play belief and playfulness with social competence were non-significant. Instead, the indirect-only mediations (Choe et al., Citation2021; Hair et al., Citation2021) between social spontaneity and social competence via children’s kindergarten social play and reticent behaviors were both positive and significant. The serial mediation among parental play belief, social spontaneity, and social competence via reticent behaviors was significant, whereas the one via social play only emerged at a trend level (barely supporting Hypothesis 8). Together, these findings are in line with recent evidence revealing that the possible impact of parental play supportiveness on children’s social development may be exerted through their playfulness (Fung & Chung, Citation2022) and also extend to show how these play characteristics are manifested behaviorally in the kindergarten context. Aligning with Hyun et al.’s (Citation2021) proposition, positive parental play belief not only facilitates children’s formative experiences through interactive play at home but also in kindergarten. Although Chinese parents may possess an ambivalent mindset with respect to the tension between playing and learning (e.g., Fung & Cheng, Citation2012; Hyun et al., Citation2021; Lin & Li, Citation2018), the positive links among parental play belief, children’s play characteristics and behaviors, and social competence were evidenced in the present results. Play can be a medium through which Chinese parents shape their child’s early social development.

Surprisingly, in the path model, children’s rough play negatively predicted their social competence, which is against Hypothesis 4. Relatedly, given physical spontaneity was unrelated to children’s kindergarten play behaviors, Hypothesis 9 (i.e., positive serial mediation among parental play belief, physical spontaneity, rough play, and social competence) was not supported. These findings contradict those from a research line showing a positive relationship between children’s rough play and social competence (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2019; Fletcher et al., Citation2013; StGeorge & Freeman, Citation2017). Nevertheless, this line of research mainly resorted to the parental rating of social competence and did not examine its association with rough play with other types of play behaviors considered. The present results revealed that rough play in the kindergarten context was negatively related to children’s social competence, at least from teachers’ perspectives. A recent study (e.g., Veiga et al., Citation2022) also demonstrated a positive relationship between children’s rough play frequency and aggressive behaviors in both school and household contexts. Therefore, the theoretical framework proposing the facilitative role of rough play in early social development, such as the evolutionary account of dominance hierarchy (Fletcher et al., Citation2013; Pellis & Pellis, Citation2007), warrants further examination using longitudinal data obtained in multiple contexts.

Limitations

The present study has at least four limitations. First, this study relied on informants’ ratings of parental play belief (i.e., by parents), playfulness (i.e., by parents), and kindergarten play behaviors and social competence (i.e., by teachers). Although this approach involves informants corresponding to the relevant contexts (Campbell et al., Citation2016), the results may be subject to common method bias. Further studies may obtain parents’ belief through interviews and employ additional observational measures like the Test of Playfulness (Bundy et al., Citation2001) and the Play Observation Scale (Rubin et al., Citation2001) to validate the present findings. Future work may also examine how alternative parental factors (e.g., academic focus) would predict children’s playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence to expand the present findings. Second, the present sample size is small. Future research with a larger sample size enables the employment of more sophisticated statistical approaches (e.g., structural equation modelling) to model various aspects of playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence as latent factors. Third, the present study was correlational, and the results from the path analysis indicated no direction of effects. Longitudinal studies with repeated measures of parental play belief, playfulness, kindergarten play behaviors, and social competence are needed to better inform the causality. Lastly, this study was specific to the Hong Kong Chinese kindergarten context, and therefore, the generalizability of the findings to other regions, countries, and cultures cannot be assumed.

Conclusions and implications

Despite these limitations, the present study contributed to the literature by demonstrating how parental belief in play can shape children’s social competence through their characteristics of playfulness, particularly social spontaneity and daily kindergarten play behaviors. Although the play-based curriculum has been advocated for more than a decade in Hong Kong, its implementation still faces some obstacles, and one of them is the lack of concrete evidence supporting the role of play in children’s academic readiness (Bautista et al., Citation2021; Fung & Cheng, Citation2012). Given that social competence is a crucial determinant of children’s school readiness (e.g., Blair & Raver, Citation2015; Campbell et al., Citation2016; Hernández et al., Citation2016), findings from this study informed the policy not only support of the play-based approach but also extended practitioners’ understanding in the meaning of and the relationship between play and playfulness (Keung & Fung, Citation2021).

Moreover, prior evidence suggested that parents and teachers are unsure about play implementation and that they may struggle to strike a balance between adult-driven and child-centered activities (Fung & Cheng, Citation2012; Hyun et al., Citation2021; Lin & Li, Citation2018). For example, the early childhood curriculum guide in Hong Kong (Curriculum Development Council of HKSARG, Citation2017) advocates for free play but, at the same time, recommends teachers design play or game-like activities that align with the curriculum goals and contents (Bautista et al., Citation2021). Parents, practitioners, and policymakers should better consider children’s views and characteristics to resolve the dilemma. On the one hand, to establish an environment that allows children to learn through play effectively, practitioners should better understand children’s characteristics (e.g., playfulness) and the factors that determine how these characteristics are displayed in the kindergarten context (e.g., culture, parental play belief, conformity to rules and expectations). On the other hand, instead of answering “what is play in the kindergarten context” by solely referring to adults’ perspectives, more attempts should be made to learn the answers from children (Bautista et al., Citation2021). For example, Keung and Fung (Citation2021) reported that Hong Kong kindergarten children perceived play as a situation that allow them to physically manipulate playful materials and socially communicate with partners.

Ethics statement

Approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Education University of Hong Kong (ref: 2019-2020-0391). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the institution’s ethical standards and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Compliance with ethical standards

This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is not available due to ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, S., StGeorge, J., & Roggman, L. A. (2019). Measuring the quality of early father–child rough and tumble play: Tools for practice and research. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(6), 889–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09513-9

- Barnett, L. A. (1991). The playful child: Measurement of a disposition to play. Play & Culture, 4(1), 51–74.

- Barnett, L. A. (2018). The education of playful boys: Class clowns in the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00232

- Bautista, A., Yu, J., Lee, K., & Sun, J. (2021). Play in Asian preschools? Mapping a landscape of hindering factors. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 22(4), 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491211058035

- Beaty, J. J. (2014). Observing development of the young child (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Berndt, T. J., & Bulleit, T. N. (1985). Effects of sibling relationships on preschoolers’ behavior at home and at school. Developmental Psychology, 21(5), 761–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.5.761

- Blair, C., & Raver, C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

- Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2018). Tools of the Mind: The Vygotskian-based early childhood program. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 17(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.17.3.223

- Bulgarelli, D., Bianquin, N., Besio, S., & Molina, P. (2018). Children with cerebral palsy playing with mainstream robotic toys: Playfulness and environmental supportiveness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1814–1814. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01814

- Bundy, A. C., Nelson, L., Metzger, M., & Bingaman, K. (2001). Validity and reliability of a test of playfulness. OTJR, 21(4), 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944920102100405

- Campbell, S. B., Denham, S. A., Howarth, G. Z., Jones, S. M., Whittaker, J. V., Williford, A. P., Willoughby, M. T., Yudron, M., & Darling-Churchill, K. (2016). Commentary on the review of measures of early childhood social and emotional development: Conceptualization, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.008

- Chen, X., Chen, H., Li, D., Wang, L., & Wang, Z. (2015). Early childhood reticent and solitary-passive behaviors and adjustment outcomes in Chinese children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(8), 1467–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0028-5

- Choe, S. Y., Lee, J. O., & Read, S. J. (2021). Parental psychological control perceived in adolescence predicts jealousy toward romantic partners in emerging adulthood via insecure attachment. Social Development, 30(4), 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12514

- Choo, M. S., Xu, Y., & Haron, P. F. (2012). Subtypes of nonsocial play and psychosocial adjustment in Malaysian preschool children. Social Development, 21(2), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00630.x

- Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(4), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557

- Coplan, R. J., & Armer, M. (2007). A “Multitude” of solitude: A closer look at social withdrawal and nonsocial play in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives, 1(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00006.x

- Coplan, R. J., Gavinski-Molina, M.-H., Lagacé-Séguin, D. G., & Wichmann, C. (2001). When girls versus boys play alone: Nonsocial play and adjustment in kindergarten. Developmental Psychology, 37(4), 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.464

- Coplan, R. J., Rubin, K. H., Fox, N. A., Calkins, S. D., & Stewart, S. L. (1994). Being alone, playing alone, and acting alone: Distinguishing among reticence and passive and active solitude in young children. Child Development, 65(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00739.x

- Curriculum Development Council of HKSARG. (2017). Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide. https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/major-level-of-edu/preprimary/ENG_KGECG_2017.pdf

- Denham, S. A., & Brown, C. (2010). Plays nice with others: Social-emotional learning and academic success. Early Education & Development, 21(5), 652–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.497450

- Du, Y., Kou, J., & Coghill, D. (2008). The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in China. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2(1), 8–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-2-8

- Eggum-Wilkens, N. D., Fabes, R. A., Castle, S., Zhang, L., Hanish, L. D., & Martin, C. L. (2014). Playing with others: Head Start children’s peer play and relations with kindergarten school competence. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.04.008

- Fink, E., Mareva, S., & Gibson, J. L. (2020). Dispositional playfulness in young children: A cross-sectional and longitudinal examination of the psychometric properties of a new child self-reported playfulness scale and associations with social behaviour. Infant and Child Development, 29(4), e2181. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2181

- Fletcher, R., StGeorge, J., & Freeman, E. (2013). Rough and tumble play quality: Theoretical foundations for a new measure of father-child interaction. Early Child Development and Care, 183(6), 746–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.723439

- Fogle, L. M., & Mendez, J. L. (2006). Assessing the play beliefs of African American mothers with preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(4), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.08.002

- Fung, C. K. H., & Cheng, D. P. W. (2012). Consensus or dissensus? Stakeholders’ views on the role of play in learning. Early Years, 32(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2011.599794

- Fung, W., & Cheng, R. W. (2017). Effect of school pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in peer interactions: Gender as a potential moderator. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0760-z

- Fung, W. K., & Chung, K. K. H. (2021). Associations between overexcitabilities and playfulness of kindergarten children. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100834

- Fung, W. K., & Chung, K. K. H. (2022). Parental play supportiveness and kindergartners’ peer problems: Children’s playfulness as a potential mediator. Social Development, 31(4), 1126–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12603

- Fung, W. K., & Chung, K. K. H. (2023). Playfulness as the antecedent of kindergarten children’s prosocial skills and school readiness. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 31(5), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2023.2200018

- Fung, W. K., Chung, K. K. H., & He, M. W. (2021). Association between children’s imaginational overexcitability and parent‐reported creative potential: Cognitive and affective play processes as potential mediators. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(4), 962–969. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.501

- Gagnon, S. G., & Nagle, R. J. (2004). Relationships between peer interactive play and social competence in at-risk preschool children. Psychology in the Schools, 41(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10120

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Mediation analysis. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_7

- Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the perceived competence scale for children. University of Denver Press.

- Hernández, M. M., Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., VanSchyndel, S. K., Spinrad, T. L., Silva, K. M., Berger, R. H., Diaz, A., Terrell, N., Thompson, M. S., & Southworth, J. (2016). Emotional expression in school context, social relationships, and academic adjustment in kindergarten. Emotion, 16(4), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000147

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hyun, S., McWayne, C. M., & Mendez Smith, J. (2021). “I See Why They Play”: Chinese immigrant parents and their beliefs about young children’s play. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 56, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.03.014

- Jackson, S. L., & Cunningham, S. A. (2017). The stability of children’s weight status over time, and the role of television, physical activity, and diet in elementary school. Preventive Medicine, 100, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.026

- Keleş, S., & Yurt, Ö. (2017). An investigation of playfulness of pre-school children in Turkey. Early Child Development and Care, 187(8), 1372–1387. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1169531

- Keung, C. P. C., & Fung, C. K. H. (2021). Pursuing quality learning experiences for young children through learning in play: how do children perceive play? Early Child Development and Care, 191(4), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1633313

- LaForett, D. R., & Mendez, J. L. (2017). Play beliefs and responsive parenting among low-income mothers of preschoolers in the United States. Early Child Development and Care, 187(8), 1359–1371. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1169180

- Lai, K. Y. C., Luk, E. S. L., Leung, P. W. L., Wong, A. S. Y., Law, L., & Ho, K. (2010). Validation of the Chinese version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in Hong Kong. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(12), 1179–1186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0152-z

- Leung, C. (2017). The concurrent validity of the Hong Kong versions of the Penn Interactive Peer Play and the Preschool Play Behavior Scale. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(4), 478–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2017.1345810

- Li, X., Lam, C. B., & Chung, K. K. H. (2019). Linking maternal caregiving burden to maternal and child adjustment: Testing maternal coping strategies as mediators and moderators. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(2), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-019-09694-0

- Lieberman, J. N. (1977). Playfulness: Its relationship to imagination and creativity. Academic Press.

- Lin, X., & Li, H. (2018). Parents’ play beliefs and engagement in young children’s play at home. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.144197

- Lin, Y.-C., & Yawkey, T. (2014). Parents’ play beliefs and the relationship to children’s social competence. Education, 135(1), 107–114.

- Lindsey, E. W., & Colwell, M. J. (2013). Pretend and physical play: Links to preschoolers’ affective social competence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 59(3), 330–360. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2013.0015

- Oberski, D. (2014). lavaan.survey: An R package for complex survey analysis of structural equation models. Journal of Statistical Software, 57(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v057.i01

- Paquette, D., Carbonneau, R., Dubeau, D., Bigras, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2003). Prevalence of father-child rough-and-tumble play and physical aggression in preschool children. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173483

- Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among pre-school children. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27(3), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074524

- Pellis, S. M., & Pellis, V. C. (2007). Rough-and-tumble play and the development of the social brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00483.x

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rentzou, K. (2014). Preschool children’s social and nonsocial play behaviours. Measurement and correlations with children’s playfulness, behaviour problems and demographic characteristics. Early Child Development and Care, 184(4), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.806496

- Roopnarine, J. L. (2011). Cultural variations in beliefs about play, parent-child play, and children’s play: Meaning for childhood development. In A. D. Pellegrini (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 19–37). Oxford University Press.

- Rubin, K. H., Cheah, C. S. L., & Fox, N. (2001). Emotion regulation, parenting and display of social reticence in preschoolers. Early Education & Development, 12(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1201_6

- StGeorge, J., & Freeman, E. (2017). Measurement of father-child rough-and-tumble play and its relations to child behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 709–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21676

- Stühmann, L. M., Paprott, R., Heidemann, C., Ziese, T., Hansen, S., Zahn, D., Scheidt-Nave, C., & Gellert, P. (2020). Psychometric properties of a nationwide survey for adults with and without diabetes: The "disease knowledge and information needs – Diabetes mellitus (2017)" survey. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8296-6

- Uren, N., & Stagnitti, K. (2009). Pretend play, social competence and involvement in children aged 5–7 years: The concurrent validity of the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2008.00761.x

- Veiga, G., O’Connor, R., Neto, C., & Rieffe, C. (2022). Rough-and-tumble play and the regulation of aggression in preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 192(6), 980–992. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1828396

- Vygotsky, L. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet Psychology, 5(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040505036