Abstract

The present paper utilized the case study of an incarcerated serial killer (“Keith”) to demonstrate how combining three assessment techniques (the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, the Rorschach task, and a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological measures) within a multilevel personality assessment framework might elucidate possible personality-based underpinnings of extreme and repetitive violence—representing a “next wave” of serial killer research while also highlighting the empirical and clinical value of an empirically-neglected multilevel assessment approach. Gacono and Meloy’s multimethod “levels” model was selected as a multilevel framework, and Leary’s recommended examination of inter-level consistency was utilized as an integrative strategy. Results indicated marked divergencies among Keith’s data levels in areas of executive abilities, psychotic symptoms, affective/emotional disconnectivity, and sexual disturbance that suggested areas for potential change (perhaps in therapy), while consistencies among levels in social cognition and object relations suggested more stable characteristics that may be resistant to modification. The application of multilevel personality assessment methods to extremely and repetitively violent persons represents an important clinical approach worthy of future study—potentially having implications for research, clinical and forensic assessment, and treatment, and advancing empirical and clinical understandings of the continuum of interpersonal violence.

Serial killers—positioned at the outermost end of the interpersonal violence continuum—may represent some of the most severe forms of personality disturbances known in the behavioral sciences. Early clinical case studies of serial sexual homicide (Krafft-Ebing, 1886/1965; Lombroso, 1876/2006) and critical foundational advances by the FBI in the latter part of the last century (Ressler et al., Citation1988) have advanced understanding of these individuals somewhat, though progress has slowed, perhaps due to the statistical rarity of serial killing and the highly restricted access to its perpetrators. Researchers have indicated the importance of assessing personality features that may be unique to serial killers, suggesting that relatively stable personality traits may play a key role in repeated acts of interpersonal violence (Culhane et al., Citation2016; Douglas et al., Citation2013). While studies of serial killers using self-report personality inventories (e.g., Angrilli et al., Citation2013; Culhane et al., Citation2016) are less-common, more-numerous examinations of the presence and prevalence of personality disorders have provided useful data (e.g., Chan et al., Citation2015; Geberth & Turco, Citation1997; and others )—though findings have been mixed. Furthermore, conceptualizing serial killers strictly on the extreme end of personality pathology may fail to capture the possibly more-nuanced personality functioning in these individuals.

For over a half-century, the Rorschach task has been used in attempts to elucidate the psychological and personality functioning of homicide perpetrators. Rorschach case studies of single-victim and familial mass murderers (Gacono, 1992, Citation1997; Lewis & Arsenian, Citation1982; McCully, Citation1978, Citation1980; Meloy, 1992; Nørbech, Citation2020), descriptive Rorschach studies of samples of murderers (Kahn, Citation1965, Citation1967; Perdue, Citation1964; Satten et al., Citation1960), and comparative Rorschach studies incorporating murderers (Greco & Cornell, Citation1992; Kaser-Boyd, Citation1993; Perdue & Lester, Citation1973) and sexual murderers (Gacono et al., Citation2000; Huprich et al., Citation2004; Meloy et al., Citation1994) have indicated disturbances in personality and psychological functioning, in domains of engagement and cognitive processing, perception and thinking problems, stress and distress, and self and other representation. Findings are not always consistent across studies, though this may be due in part to the heterogeneity of murderers as a population (i.e., psychological, motivational, and behavioral), or to the different methods and systems historically used for scoring the Rorschach. While limited Rorschach data from serial killers have been presented individually (Kraus, Citation1995; Schlesinger, Citation1998) and collectively (Meloy et al., Citation1994), individual Rorschach case studies of serial killers are exceptionally rareFootnote1 (Gacono & Meloy, 1994).

The neurobiological model may also play a critical role in the understanding of serial killers’ ability to repeatedly kill. Neuropsychological studies have identified key impairments in executive functioning (EF) in violent and aggressive individuals, thought to be associated with structural and functional deficits in the frontal lobe (Schug & Fradella, Citation2015). Generally speaking, murderers have shown low average to average performance across functional domains—though EF findings have been mixed (Azores-Gococo et al., Citation2017; Hanlon et al., Citation2010). Premeditated murderers significantly outperform affective/impulsive murderers (Hanlon et al., Citation2013), as do mass murderers when compared to single-victim murderers (Fox et al., Citation2016). Neuropsychological studies of serial killers in particular are uncommon, though two rare serial killer case studies have also indicated mixed EF findings (Angrilli et al., Citation2013; Ostrosky-Solís et al., Citation2008). Interestingly, while brain imaging studies of murderers have shown reduced prefrontal functioning in murderers compared to normal controls, frontal lobe functioning in predatory murderers appears intact relative to affective murderers, as it does in multiple murderers relative to single-victim murderers (Raine, Citation2013). Researchers have also proposed that serial killers are characterized by functional impairments in Theory of Mind (ToM) abilities (i.e., mentalization, or estimating the mental states of others), and have associated autism spectrum disorder—the prototypical condition associated with significant ToM impairments—with various serial killers in developmental models (e.g., Silva et al., Citation2002, Citation2005). However, findings are mixed (e.g., Angrilli et al., Citation2013), and ToM functioning has not been systematically explored in serial killer populations. Ultimately, while neurobiological studies of violence may explain how an individual is able to perpetrate multiple killings, it may be measures of personality functioning—which are largely missing from these studies—that provide critical information regarding why. To that end, a “next wave” of serial killer research that moves beyond singular methods of assessment may now be the key to furthering empirical understanding of personality-based underpinnings of extreme and repetitive violence.

Multilevel personality assessment

Mid-twentieth century interpersonal researchers and personality theorists began proposing multi-layered conceptualizations of personality (known as the “levels hypothesis”), with individual layers representing different “levels of consciousness” characterized by different degrees of accessibility (i.e., observability by the self and others) and acceptability (i.e., to the individual themselves; see review in Stone & Dellis, Citation1960). Empirical discussions of how to best gather and combine data reflecting each layer soon followed—marking the dawn of multilevel personality assessment. Leary (Citation1957) originally proposed five levels in the interpersonal dimension of personality—(I) public communication, (II) conscious descriptions, (III) private symbolization, (IV) the unexpressed unconscious, and (V) values—each with its own specific meaning, function, and sources of assessment data. Leary argued that critical information could be gleaned from observing discrepancies and inconsistencies among levels (structural variability), time spans (temporal variability), and cultural and environmental factors (situational variability). He gives the following illustrative examples of structural variability:

“The subject who presents himself as a warm-hearted, tender soul may produce dreams or fantasies which are bitterly murderous. Social interactions, as observed by others, may be quite different from the subject’s own view of them” (p. 243).

He further emphasized the significance of inter-level consistency and its implications for conceptualization and treatment:

“There is evidence… that the more stable the organization of personality—that is, the more data from Levels II, III, and I tend to repeat the same themes—the less variation we can expect in the personality organization over time. Conversely, the more conflict or oscillation among the levels of personality, the more change we can predict will take place in the future; and this includes change in therapy” (p. 247).

Stone and Dellis (Citation1960) subsequently described particular groups of patients (i.e., pseudoneurotic or with pseudocharacterological schizophrenia) who showed thought disturbances on “depth” but not “surface” psychological tests—unlike patients with schizophrenia who showed significant disturbances on both. These authors proposed a personality organized by levels of impulse-control mechanisms existing on a continuum (from primitive and undifferentiated to highly organized and differentiated), and posited that the structure of a test (high versus low) reflected the level of personality or impulse-control system (more conscious versus less conscious) tapped by the test—suggesting the diagnostic value of multilevel assessment and importance of test selection.

A handful of contemporary researchers have since expanded upon these concepts in various lines of empirical inquiry, noting the research and practical applications of multilevel assessment in case conceptualization, treatment planning, clinical decision-making, and intervention. McAdams (Citation1992) emphasized the importance of studying personality organization and integration (as opposed to focusing upon general, decontextualized traits such as the “Big Five”) and highlighted the value of considering multiple layers of information (e.g., “middle-level units” of cognitive expression, or “conditional patterns” in individuals’ open-ended descriptions of themselves)—as well as an idiographic perspective—in personality research. Benjamin (Citation1994) proposed a three-surface SASB model (focus on other, focus on self, and introjected focus) with practical applications for psychotherapy, while Bornstein (Citation2003) proposed four types of outcome measures (self-reports, secondhand/archival data, analogs/indirect measures, and directly observed behavior) and four methodologies (idiographic, correlational, epidemiological, and experimental) for personality disorder research. More recently, Dawood and Pincus (Citation2016) demonstrated the value of multisurface interpersonal assessment batteries in cognitive-behavioral therapy contexts. Furthermore, while the limitations of relying upon singular methods of assessment have been noted (e.g., Bornstein, Citation2003; McAdams, Citation1992; Monahan et al., Citation2001; Stone & Dellis, Citation1960), multilevel assessment nonetheless remains a neglected area of assessment research (Dawood & Pincus, Citation2016) which has not found its way into the mainstream of clinical practice. Continued clinically-informative research could serve to revitalize empirical interest in this area.

Proposal and methods

The present paper serves to address apparent needs in two separate literatures—the need for integrative personality assessment in the “next wave” of serial killer research, and the need to study the practical application of an empirically-overlooked multilevel personality assessment framework. Here I will attempt both—by using the case study of an incarcerated serial killer to demonstrate how three assessment techniques (structured clinical interviewing, the Rorschach, and neuropsychological tests) may be combined within a multilevel assessment framework for the purposes of furthering the empirical understanding of individuals with propensities for extreme and repetitive violence.

Case

Keith Hunter Jesperson is a 66-year-old incarcerated male. He has been the subject of several true crime books, television programs, and audio podcasts which vary in terms of credible biographical information and actual clinical value. In 2015, I recruited him into my larger, ongoing research study on biopsychosocial etiological factors and neurocognitive functioning in multiple homicide offenders. Data were collected via telephone interviews and two separate face to face site visits. Keith provided both written and verbal consent for the publication of his identity and research data. The study and all of its procedures are approved by the Institutional Review Board at California State University, Long Beach, as well as by the Research Committee at Oregon State Penitentiary.

Materials and procedure

Standard psychological tests—commonly used in research, clinical, and forensic assessment and with established reliability and validity—are administered to participants as part of the larger study. As a researcher, licensed psychologist, and practicing forensic psychologist, I have had extensive graduate-, post-graduate-, and professional-level training and experience with the administration of these measures in research, clinical, and forensic settings. All measures were administered and scored according to test designer and manufacturer specifications. These consisted of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First et al., Citation1997), and the Rorschach task (Rorschach, 1921/1942), a comprehensive neuropsychological testing battery, assessing domains of intellectual functioning (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence—Second Edition [WASI-II]), learning and memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [RAVLT], Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth Edition [WMS-IV] Logical Memory I and II subtests), psychomotor speed (Grooved Pegboard Test [GPT]), EF (Comprehensive Trail-Making Test [CTMT], Iowa Gambling Task [IGT], Porteus Mazes Test [PMT], Tower of London—Drexel University: 2nd Edition [TOLDX], Wisconsin Card Sorting Test [WCST]), malingering and effort (Dot Counting Test [DCT], Test of Memory Malingering [TOMM]), and Theory of Mind (ToM), or the ability to attribute mental states to oneself or other people (Premack & Woodruff, Citation1978; assessed via the Revised Version of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test [RMET; Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001]).

Gacono and Meloy (1994) proposed a multimethod “levels” model of understanding personality (Levels I – IV: behavior, conscious cognitions, unconscious structure and function, and biology) that recognizes its biopsychosocial dimensional complexity and emphasizes the importance of integrating multiple forms of data in personality assessment (observation, self-report measures, projective testing, and brain imaging and psychophysiological measures, respectively). This biopsychosocially-oriented model—originally introduced within the context of assessing aggressive and psychopathic personalities—was seen as a suitable fit for the data collected here and selected as the operational framework for multilevel assessment. Furthermore, as Gacono and Meloy did not specify an integrative strategy for data among levels in their proposed model, Leary’s (Citation1957) recommended approach of examining inter-level consistency was adopted to serve this purpose.

Historical data and clinical features

Keith was born and raised in western Canada and is the third-oldest of five children (two brothers and two sisters). He denied any knowledge of perinatal complications or delays in meeting developmental milestones, and was raised by both of his biological parents. His father worked as a welder, owned a machine shop, and designed and patented several machinery products. His mother was a homemaker. Keith described his father as both “a good father” and “a hard-working drunk with severe mood swings.” He provided very little information about his mother. Keith appears to have gotten along adequately with his parents, who were not affectionate toward him. He reported that he often knew of—but did not witness firsthand—verbal and physical conflict between them. While he denied any family history of mental illness or documented criminality, he indicated that his father had killed a man in a hit and run accident (for which he was never caught). Keith reported distant relationships with his siblings while growing up. While he suffered no sexual abuse or neglect during his formative years, he was repeatedly physically abused by both parents. At age 12, his family moved to the U.S., where he later graduated high school but did not attend college. He had a stable work history (39 different jobs since age 15), including employment as a machinist, heavy equipment operator, and long-haul truck driver. He is divorced, and has three children (two daughters and a son). Keith suffered from a number of head injuries beginning at age 8, and denied any significant mental health history. He first used alcohol at age 12, and reported some occasional binge drinking, as well as driving while under the influence of alcohol on approximately 12 occasions (ages 16 − 26). He denied any other history of substance use. Keith was polite and cooperative throughout all interviews and psychological testing sessions. He did not present with any overt signs or symptoms of mental illness.

Assessment findings

Level I: “Observational” data

Keith’s serial killing was a defining behavioral focus in the present case studyFootnote2, and was considered an analogue to Gacono and Meloy’s (1994) behavior level data (normally obtained via observation), in the spirit of Leary’s (Citation1957) “public communication” level of assessment (i.e., overt behavior rated by others). While Keith’s murders were not directly observed in the empirical sense, accounts of his offense characteristics have been widely publicized, and thus reflect independently “observable” documented behaviorsFootnote3. Keith is currently serving four life sentences for murder at Oregon State Penitentiary. He has confessed to killing eight women in several different states across the U.S., and these victims have been confirmed. Keith’s first homicide occurred at age 34, and he killed his subsequent victims over a five-year period until his arrest at age 39Footnote4. Most of Keith’s homicides were associated with his employment as a long-haul truck driver, in terms of victim acquisition, methodology, and victim body disposal. His victims were casual acquaintances, sex workers, and one long-time girlfriend, who—with the exception of his first victim—were encountered at truck stops or other locations related to his work. His crime scenes (again, with the exception of the first victim) were the interior of the cab of his semi-trailer truck. His method of killing was generally manual strangulation by hand or fist, though he also punched his first victim in the face several times before strangling her, and used plastic zip ties to strangle another victim. After one murder, he allegedly strapped the victim’s body to the undercarriage of his truck and dragged it on the highway, face down, to prevent identification by investigators. He disposed of his victims’ bodies near freeways (e.g., in ravines or wooded areas) and in parking lots. Most of Keith’s murders appear to be sexual homicides (i.e., involving sexual intercourse with the victim immediately before their deaths) that he often contemplated in advance (usually while driving in his truck alone or while victims were riding with him). Keith was also arrested for assault at age 35 (after his first homicide) when, while seated in his automobile, he twisted and nearly broke the neck of a 21-year-old woman after she rejected his sexual advances. At one point, Keith publicly communicated information about his killings using anonymous written messages signed with a smiling face. Aside from his six convictions for murder and arrest for assault, he has no documented criminal history.

Level II: SCID-II data

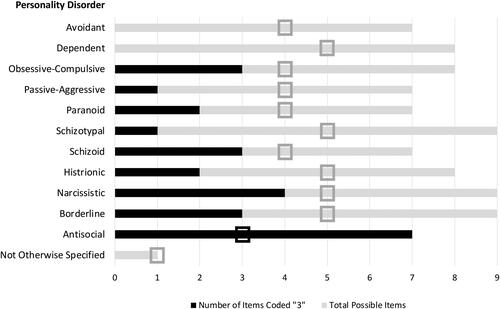

A summary of Keith’s SCID-II diagnostic scores for each personality disorder (i.e., the number of SCID-II items on which he scored a “3,” indicating the definite presence of a given personality disorder trait) are presented dimensionally in . Keith met diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). He is an adult, has evidence of conduct disorder before the age of 15 (using a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others, and shoplifting), and has a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others since age 15 (as evidenced by maximum item scores for recurrent unlawful behaviors, deceitfulness, impulsivity, irritability and aggressiveness, reckless disregard for others’ safety, consistent irresponsibility, and lack of remorse). He met four of the five narcissistic personality disorder criteria (grandiosity, entitlement, lack of empathy, and arrogance/haughtiness), and three of the four schizoid personality disorder criteria (neither desires nor enjoys close relationships, almost always chooses solitary activities, and lack of interest in sexual experiences with others). He also met three of the four obsessive-compulsive personality disorder criteria (excessive devotion to work and productivity, reluctance to delegate tasks/work unless others submit to his exact way of doing things, and rigidity and stubbornness), and three of the five borderline personality disorder criteria (unstable and intense interpersonal relationships; impulsivity; and inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger). Additionally, Keith was characterized by lesser-degrees of passive-aggressive, paranoid, schizotypal, and histrionic personality traits.

Level III: Rorschach data

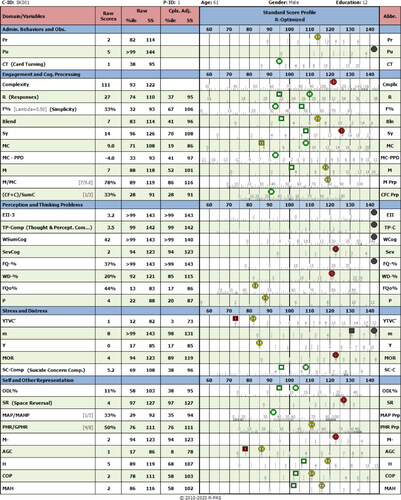

Keith’s Rorschach protocol was coded and interpreted using the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS; Meyer et al., Citation2011), because of its evidenced-based, internationally-oriented approach, and demonstrated utility in the assessment of many different types of individuals, including murderers (Mihura & Myer, 2018; Nørbech, Citation2020). Keith was administered all ten inkblots and provided a sufficient number of responses (R = 27). His two Prompts (SS = 114, Above Average range) and five Pulls (SS = 144, Above Average range) suggest defensiveness, ambitiousness, striving to please, and/or poor psychological boundaries. His protocol was very productive and complex (Complexity = 111, SS = 122, High range), and is valid and interpretable with some additional considerationsFootnote5. Keith’s Summary Scores and Profiles are presented in , and his protocol and R-PAS code sequence in the online Appendices A and B.

Figure 2. R-PAS summary scores and profiles (complexity adjusted)—Page 1.

Note. Raw scores, percentiles, and scaled scores are listed in columns 2 and 3, while Complexity Adjusted percentiles and scaled scores are listed in column 4. In column 5 (“Standard Score Profile R-Optimized”), scores are depicted visually as icons: circles (raw scores) and boxes (Complexity Adjusted scores). These icons are also color coded based on 10-point Standard Score “bins”—where green open icons fall within the middle range (90 – 110), yellow icons with one bar in the next range outward (80 – 89 and 111 – 120), red icons with two bars in the next range outward (70 – 79 and 121 – 130), and black icons in the extreme ranges (< 70 and > 130). Scores can also be conceptualized in terms of performance ranges which follow a similar 10-point bin classification—though these are slightly modified for some variables (known as “Page 2 variables”) in the following manner: Average (85 – 115), Below Average (70 – 84), Low (< 70), Above Average (116 – 130), and High (> 130). As can be seen, some of Keith’s scores remain unchanged even when adjusted for Complexity (e.g., MC – PPD). Reprinted with permission.

In the engagement and processing domain, Keith’s average performance on a number of variables (F%, Blend, MC – PPD, Sy, (CF + C)/SumC, Mp/(Ma + Mp), V, R8910%, C, Vg%, FD) suggest he can adequately engage with complex and subtle aspects of his experiences and relationships. His Space Integration responses (SI = 5, SS = 114, Above Average) suggest cognitive effort and motivation, a capacity for complex processing, and mature EF. However, he appears to look at the world in an idiosyncratic manner (Dd% = 44%, SS = 133, Above Average; W% = 30%, SS = 85); and his responses also indicate emotional avoidance, very limited emotional reactivityFootnote6, and marked inhibition (WSumC = 2.0, SS = 70, Below Average), and a preference for reflection and reason—for “living in his head” as opposed to “living in the moment” (M/MC = 78%, SS = 116, Above Average). In fact, his abstract, symbolic, intellectual/pseudo-intellectual manner of information processing (IntCont = 5, SS = 110, Above Average) further suggests a defensive style that distances him from uncomfortable emotions, and that he prefers to intellectually examine feelings rather than experience or express them.

Regarding perception and thinking problems, Keith’s responses incorporated a significant degree of general psychopathology (EII-3 = 3.2, SS = 143, Very High), at levels typically associated with psychotic disorders (TP-Comp = 3.5, SS = 142, Very High). While he evidenced some breakthrough primitive content and poor interpersonal accuracy, his EII-3 score was driven predominantly by cognitive slippage and perceptual inaccuracy. Regarding the former, Keith likely has significant problems thinking and reasoning in an accurate, logical, and effective manner; and experiences thought processes that are severely disturbed, confusing, and disorganized (WSumCog = 42, SS = 143, Very High). His protocol contained 21 Level 1 Cognitive Codes (i.e., mild to modest examples of thinking problems) and two Level 2 Cognitive Codes (i.e., moderate to severe disruptions in thinking). The latter (SevCog = 2, SS = 123, High) is noteworthy, given that even one Level 2 Cognitive Code within a protocol is considered unusual. In fact, Keith produced 19 language-and-reasoning Level 1 Cognitive Codes (DV1 = 14, DR1 = 5), and one language-and-reasoning Level 2 Cognitive Code (DV2) in II-R3 (“Right up here… and the knees clashing down here… and their heads then… is this… this… fired in with red… in their heads…”). Regarding perceptual inaccuracy, a significant proportion of Keith’s responses did not match the shape of the inkblots (FQ-% = 37%, SS = 143, Very High)—even when attending to common, obvious, and conventional features (Wd-% = 20%, SS = 115, Above Average; FQo% = 44%, SS = 86, Below Average), or identifying popular objects (P = 4, SS = 87, Below Average). Keith also produced two perceptually-based Level 1 Cognitive Codes (INC1 = 2), as well as one perceptually-based Level 2 Cognitive Code (CON) in VIII-R21, where he perceives area D6 to be a “corset” or a “gown” on a “rack” or “hanger,” while simultaneously perceiving the bottom area of D6 to be the “hips of a woman.” Keith’s perceptual inaccuracy may translate into significant and generalized difficulties with reality testing, where his idiosyncratic and distorted perceptions weaken his ability to effectively understand the self, other, and the environment, and to navigate day-to-day challenges (though the majority of Keith’s perceptually-based Cognitive Codes occurred when he was perceiving human content, suggesting he may have particular difficulties understanding the self and/or other).

In the stress and distress domain, Keith’s scores (PPD, SC-Comp, C’, CBlend) were largely unremarkable and in the Average to Below Average ranges. His responses indicate he may be less likely to attend to and articulate the inconsistencies, uncertainties, and nuances in his environment. This may be adaptive simplification, whereby he experiences less implicit distress related to anxiety, irritation, sadness, or helplessness. It also suggests that he is less sensitive to the subtleties of his own internal experiences, or to those occurring within interpersonal experiences (YTVC’ = 1, SS = 73, Low). He appeared to be experiencing some distracting ideation that is often associated with environmental stressors (m = 8, SS = 131, Above Average), which can interfere with purposeful or goal-directed thinking. In Keith’s case, however, this appears to be without the commonly-associated helplessness and distress (Y = 0, SS = 85, Low through Average). As such, he may typically respond to environmental stressors with rumination but not feeling.

Keith reported an above-average number of morbid images (MOR = 4, SS = 119), which suggest identification with being damaged, flawed, or somehow harmed by life and external events. Keith’s uncommon MOR responses would normally indicate a dysphoric and negative view of the world; however, these responses also suggest he may identify with the “damager” (aggressor) rather than the “damaged” (victim). Specifically, while he did not express enjoyment of the morbidity, he appeared nonchalant about it. Also, two of Keith’s MOR responses contained personally relevant themes (VI-R13 “cutting two things apart,” and VI-R14 “almost like a bad weld”—echoing his previous experience as a welder) in which he identifies with the “damager.” He does so in a third MOR response as well (V-R12) describing a defective “boomerang” which “might take the legs out of a birdFootnote7.” On a different interpretive note, responses V-R11 (“a moth… really bad wing structure”) and V-R12 (“a really bad lookin’ boomerang”) deal with damage or malformations to mechanisms of flight, possibly representing his own inability to “fly away” or free himself from current or past circumstances (e.g., marital difficulties, incarceration). Finally, his consecutive MOR responses (V-R11, V-R12, VI R13, and VI-R14), suggest he may transitorily lapse in and out of these identifications.

Keith also reported an above-average number of images that are typically censored in social interactions (CritCont% = 41%, SS = 116)Footnote8, which appeared primarily related to sexual and morbid content. Such primitive thought content may overrun Keith’s censorship capabilities, suggesting that he has difficulties making benign or ordinary interpretations of emotional events or taking a realistic distance on his experiences. Keith’s significant number of sexual responses (Sx = 4, SS = 133, Very High) is noteworthy given the consensus among researchers that preoccupation with sexuality on the Rorschach suggests sexual disturbance (Morgan & Viglione, Citation1992). His sexual responses were not characterized by sadistic themes, and pertained only to women’s reproductive anatomy (I-R1, “ovaries”) and sexual clothing (VIII-R20, “girdle”; VIII-R21, “corset”; and X-R26, “bra”). However, themes of degradation and shame appeared in one response (X-R26, “a woman standing in middle of… of something there… with her bra hanging down too low…”), and his aforementioned contamination of human detail and sexual content (VIII-R21) suggests a sexual objectification of women.

In terms of self and other representation, Keith’s scores reflecting potential for mature and healthy interactions, interpersonal relationships, and emotional closeness (COP, H, MAH, MAP/MAHP, NPH/SumH, T), level of interest in and attentiveness to people (SumH), self-absorption and/or need for mirroring support (r), implicit dependency needs (ODL%), passive versus active inclinations in behaviors or attitudes (p/(a + p)), envisioning and being aware of aggressive intents or actions (AGM), and concerns about physical illness or body integrity (An) were in the Average range. He does not appear to process information in a vigilant, guarded, and detail-oriented manner (V-Comp = 3.7, SS = 89, Average). He also reported a low number of aggressive images—suggesting he is less likely to have aggressive thoughts and concerns in mind (AGC = 1, SS = 78, Below Average)Footnote9—and did not appear to unusually identify with aggressive activity (AGM = 1, SS = 110, Average). On balance, Keith envisions human images or activity in problematic ways (PHR/GPHR = 50%, SS = 111, Above Average)Footnote10, and lapses into significant misunderstandings or misperceptions of people’s thoughts and intentions, resulting in disturbed interpersonal relations (M- = 2, SS = 123, High). His responses characterized by poor human representation contained imagery that is aggressive (II-R3, “two people fighting”), damaged (VI-R13, “a bad torch job”), partial (VIII-R21, “hips of a woman”), and sexual (VIII-R21, “corset, stockings,” and X-R26, “bra”). All are also distorted, illogical, and/or confused in varying degrees—with the most extreme being VIII-R21 (described above), in which he fuses human detail with sexually suggestive clothing. His two M- responses (VI-R21, X-R26) also suggest that the particular contexts in which he lapses into inaccurate understandings of others involve sex and/or damage, injury, flaws, or sadness. Additionally, Keith’s perceptual reversals (SR = 4, SS = 127, Above Average), suggest creativity, individuality, or healthy self-assertive strivings, which may be expressed as oppositional behavior and associated with an aversion to feeling controlled or pressured by others. Finally, Keith likely expects challenges from others and responds to insecurity about this with an aggrandizing and self-justifying defensive reaction (PER = 3, SS = 125, Above Average). As such, others may find him to be defensive, self-centered, and irritating.

Level IV: Neuropsychological data

Keith’s scores, percentiles, and performance descriptions are listed in . Regarding intellectual functioning, Keith’s verbal comprehension would be considered in the low average range, and his perceptual reasoning would be considered in the average range. While Keith’s performance on verbal comprehension and perceptual reasoning indices may be considered purer measures of his verbal and nonverbal intellectual abilities separately, the significant discrepancy among index scores suggests they cannot be interpreted as a unitary Full Scale IQ estimate, and thus do not accurately reflect his overall intellectual abilitiesFootnote11. With regard to learning and memory, Keith may be an initial slow learner who eventually “catches on” and learns at an average level. For example, His RAVLT Trial I – V score was in the Borderline range. This score was most-negatively impacted by his performance on the initial trials of this test (Trial I T Score = 29, Mild Impairment range, and Trial II T Score = 32, Borderline range). However, his RAVLT Delayed Recall T Score was in the Average range, indicating that he eventually learned the word list. I also incorporated the WCST Trials to Complete 1st Category score into this domain as it speaks to learning (i.e., learning the first rule of card sorting, sorting the cards by color) as well as EF (i.e., cognitive flexibility). It took Keith 24 attempts to complete the first category, which would be considered in the mild impairment to borderline ranges—his worst score on the WCST. On balance, his IGT scores suggest he was able to effectively learn the difference between the risky and non-risky decks. Furthermore, he performed in the average range on measures of attention and psychomotor speed. Keith demonstrated no broad-based deficits in executive functioning. With the singular exception of his aforementioned (and perhaps anomalous) WCST Trials to Complete 1st Category score, he performed at or above the Average range on all measures within this domain. In fact, his CTMT Trail 4 and IGT Net Total scores would be considered in the High Average range—the latter suggesting a relative strength in his decision-making abilities.

Table 1. Neuropsychological test performance.

Regarding Theory of Mind, Keith’s total score on the RMET (i.e., the total number of items he answered correctly) was 22 out of 36. This score indeed appears similar to the RMET scores of individuals with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism (M = 21.9, SD = 6.6) reported by Baron-Cohen and colleagues (2001)—a group with significantly lower RMET scores compared to general population controls, students, and individuals matched for IQ with the Asperger syndrome/autism group. Z-score calculations indicated Keith’s RMET performance would be considered in the low average range compared to the general population controlsFootnote12, and in the borderline range relative to a majority of studies culled from a systematic review of 23 studies (Vellante et al., Citation2013)Footnote13. Additionally, Keith performed worse on RMET items depicting male faces (10, or 71.4% of all incorrect items) compared to female faces (4, or 28.6% of all incorrect items), though a Chi-Square analysis revealed that this difference (χ2 [1,36] = 3.20, p = 0.07) was not statistically significant at p < .05. Subsequent exploratory Chi-Square analyses revealed that Keith also performed worse on items depicting negatively-valenced mental states (e.g., “upset”) compared to positively-valenced ones (e.g., “playful”), though this difference was not significant (χ2 [1,36] = 1.03, p = 0.31). Interestingly, this relationship remained unchanged for male faces (χ2 [1,36] = 1.02, p = 0.31), but appeared to strengthen for female faces (χ2 [1,36] = 2.47, p = 0.12), suggesting that he may have particular difficulties identifying negative mental states in the faces of women.Footnote14 Keith’s RMET results are presented in the online Appendix C.

Discussion: Integrative conceptualization and hypothesis testing using multilevel assessment

What follows is a demonstration of how Gacono and Meloy’s (1994) proposed multimethod “levels” model (as an operational framework for multilevel assessment) and Leary’s (Citation1957) observation of inter-level consistency (as an integrative strategy) might facilitate hypothesis-testing related to personality-based etiological mechanisms in extreme and repetitive violence using case study data.

Executive dysfunction

Keith’s serial killing (Level I), at first glance, may suggest violence associated with dysfunction in the frontal lobe. However, consistent with previous brain imaging findings in serial and predatory killers (Raine, Citation2013), Keith does not appear to be characterized by widespread frontal lobe deficits. His SCID-II ASPD and borderline personality traits (Level II: recurrent unlawful behaviors, impulsivity, and irritability) suggest behavioral manifestations of cognitive set-shifting, decision-making, and behavioral control deficits; and he may experience disinhibition or problems following or internalizing rules (Level III: Rorschach Pulls). On balance, his neuropsychological and Rorschach performance (Levels III and IV) indicates EF that is intact (CTMT, TOL, WCST) and even above-average for some specific abilities (CTMT Trail 4, IGT, Rorschach SI). Keith also demonstrated marked emotional inhibition—he is more likely to reflect and reason rather than react spontaneously to emotions, impulses, or circumstances (Level III: Rorschach WSumC, M/MC). Keith may, however, experience EF difficulties that are more contextually-based. For example, his complex cognitive processing (Level III: Rorschach Complexity) may be a liability during unstructured emotional or interpersonal situations or periods of psychological difficulty or disturbance, wherein he is unable to let things be simple or uncomplicated, and may have ideas, motivations, and behaviors that are difficult to understand, as well as confusion, poor psychological boundaries, and overwhelming ideas and emotions that are upsetting and poorly-controlledFootnote15. He may also be affected by distracting thoughts resulting from environmental stressors (Level III: Rorschach m), and may be prone to censorship failures of personally or socially aversive or taboo (e.g., sexual) imagery (Level III: Rorschach CritCont%). Furthermore, his heightened creativity and individuality (Level III: Rorschach SR) may be expressed as oppositionality at times, particularly when he feels controlled or pressured by others.

Social cognition deficits

Keith’s deficits in social cognition align with studies noting such deficits in individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation2001), ASPD (Newbury-Helps et al., Citation2017), and psychopathic traits (Sharp & Vanwoerden, Citation2014). Keith experienced difficulties identifying mental states in the facial expressions of others (particularly men), and had specific difficulties identifying negatively-valenced mental states in women (Level IV: RMET)Footnote16. He also appears to view the world idiosyncratically, live in his head, intellectualize, and misunderstand and misperceive others—particularly in sexual and morbid contexts (Level III: Rorschach). Keith’s mentalizing difficulties may reflect a heightened social reflection impulsivity (a failure to process relevant information during social decision-making resulting in aberrant interpretations of ambiguous social situations), which has been linked to aggression (Brennan & Baskin-Sommers, Citation2019). His SCID-II schizoid personality traits (Level II) may further indicate isolativeness secondary to social cognition deficits.

Psychotic symptoms

Indicators of other potential etiological factors in Keith’s serial killing behavior were revealed upon examination of his assessment data. For example, his cognitive slippage and perceptual inaccuracies (Level III: Rorschach WSumCog, FQ-%) may suggest the presence of a psychotic disorder. Researchers have noted that specific delusions (e.g., persecutory, threat/control-override, misidentification syndromes) and particular qualities of command auditory hallucinations may be associated with violence, while other symptoms of psychotic illness, such as social withdrawal, may actually reduce violence risk (Schug & Fradella, Citation2015). While Keith’s SCID-II paranoid and schizotypal personality traits (Level II) reflect concerns about the loyalty, trustworthiness, and malevolent intentions of others, they do not rise to the level of delusional ideation. In fact, the isolativeness indicated by his schizoid personality traits (Level II) is proportionally more prominent (see ). Furthermore, Keith has no history of perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucinations—Level II); and while his perceptual accuracy with the unstructured Rorschach material is markedly poor (Level III), his ability to perceive and reason with visual stimuli in structured contexts (Level IV: WASI PRI) appears intact. His overall neuropsychological performance (Level IV) is also not consistent with the broad-based cognitive deficits associated with psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia (Schug & Raine, Citation2009). Overall, Keith’s idiosyncratic manner of viewing the world (Level III: Rorschach Dd%, W%), signs of thought disorder, and poor reality testing may suggest subclinical psychotic symptomatology, though the traditional pathways linking psychosis and violence are not reflected in his killings.

Object relations disturbances

Keith’s SCID-II, neuropsychological, Rorschach, and historical data suggest unconscious remnants of his early parental relationships and experiences which may have contributed to poor self and other conceptualization, interpersonal difficulties, and a propensity for interpersonal violence. Keith’s father (a respected business owner, inventor, and community member; an emotionally labile “drunk” who permitted alcohol use among his children; a harsh disciplinarian and spouse abuser; and himself an uncaught murderer), sent Keith ambivalent messages about right and wrong during his formative years (Level II), and modeled oppositionality (“his way or the belt”) and the objectification of womenFootnote17. To this “good father,” Keith was merely “baggage he just took with him to places”—a possible source of Keith’s ambitiousness, striving to please (Level III: Rorschach Pulls), aggrandizing, and self-justifying (Rorschach PER)Footnote18. Keith’s mentalizing difficulties specific to males (Level IV: RMET) suggest another artifact of this enigmatic paternal relationship. Keith’s mother (a caretaker who “knitted us clothes… made sure we had what we needed,” and herself a physical abuser), a distant and unimportant figure in Keith’s life, appears to have provided him with insufficient physical affection (Level II)Footnote19. His difficulties identifying negative mental states in women (Level IV: RMET) may reflect this troubled maternal relationship, and his unstable and intense interpersonal relationships (SCID-II) may reflect his early and prolonged exposure to parental conflict. Additionally, Keith’s concept of the self as grandiose (Levels II and III: SCID-II, Rorschach PER) and deeply injured (Level III: Rorschach MOR) is consistent with the “inherent conflict and core psychopathology” of sexual killers (Gacono & Meloy, 1994, p. 289), and echoes his significant history of abuse and head injuriesFootnote20. His aggressive identifications are subtle (Level III: Rorschach AGC, AGM, MOR)—though like many antisocials his aggressive impulses may be ego syntonic, causing him to experience less aggression in the present (Gacano & Meloy, 1994). Keith’s serial killings may further reflect a form of sadistic behavior and—as such—represent rituals of reenactment relating to past traumatic events. His perceptually-based Rorschach Cognitive Codes may indicate a vulnerability to the temporarily distorted person perception and orientation thought to occur during such reenactments (Juni, Citation2009). In aggregate, while Keith’s childhood experience of his parents is likely not a direct causal factor in his serial killing, his data may suggest an unconscious, object relations-based predisposition to interpersonal violence in adulthoodFootnote21.

Affective/emotional disconnectivity

Keith’s emotional detachment may represent an additional vulnerability to interpersonal violence. While his nonverbal intellectual capabilities do not suggest any biologically-based right hemispheric dysfunction (Level IV: WASI-II PRI), he nonetheless appears emotionally avoidant, inhibited, and unreactive (Level III: Rorschach WSumC, M/MC, IntCont), and even evidenced affective disconnect in his serial killing behaviors (i.e., anonymous communications about the murders signed with smiling faces—Level I). This emotional uncoupling may reflect experiential avoidance (altering the internal experience of emotion) or emotional inexpressivity (inhibiting the outward expression of emotion), which are associated with heightened emotion dysregulation and increased risk for aggression (Tull et al., 2007). While Keith’s interpersonal/relational aggression problems (Level II: SCID-II) may be a byproduct of conscious, deliberate suppression of emotions (Kim & James, Citation2015), his emotional disconnectivity may also reflect an unconscious isolation of affect (Freud, Citation1926). Regardless of their origins, Keith’s bottled-up emotions may have served as the explosive fuel for his repeated acts of extreme violence, requiring only the presence of an interpersonal “spark” to ignite and set them in motion.

Sexual disturbance

Keith’s signs of sexual disturbance suggest a further vulnerability to interpersonal violence. All of Keith’s killings occurred in close temporal proximity to sexual interactions with his victims—either during or immediately after sexual intercourse (Level I). Sexual preoccupations are evident in his Rorschach responses (Level III), marked by themes of degradation, shame, and objectification of womenFootnote22. Further, while he indicated a robust sexual history and adequate capacity for sexual gratification, he denied sexual interest (Level II: SCID-II)Footnote23. This incongruency suggests an immature or autistic understanding of sexual thoughts, behaviors, gratification, and/or relationships, which may have contributed to Keith’s eroticization of sexual control. He also evidences difficulties interpreting sexual cues and navigating sexually-ambiguous interactions with others (Levels II and IV)Footnote24. In these instances, deviations from Keith’s maladaptive sexual scripts (i.e., by his victims) were likely met with violent reactions, while sexual conditioning to this violence led to more killings.

Summary, implications, and conclusion

The present paper used the case study of an incarcerated serial killer to demonstrate how three assessment techniques might be combined within a multilevel assessment framework to elucidate possible personality-based underpinnings of extreme and repetitive violence—representing what may be the “next generation” of serial killer research, and highlighting the potential empirical and clinical value of an underutilized multilevel assessment approach. With Keith—a serial killer—this approach revealed fundamental disconnects from two worlds (his outer social one and his inner emotional one) resulting in a pathway toward extreme violence marked by isolation and rejection, interpersonal difficulties, and problematic emotional experiences. Furthermore, marked divergencies among data levels in areas of executive abilities, psychotic symptoms, affective/emotional disconnectivity, and sexual disturbance suggest areas for potential change (perhaps in therapy), while congruencies among levels in social cognition and object relations suggest more stable characteristics that may be resistant to modification. Perhaps more importantly—as Keith’s data show—the multifaceted etiologies of extreme and repetitive violence arguably cannot be captured by singular assessment methods alone, and reliance upon one technique may lead to inaccurate case conceptualization and potentially negative clinical and forensic consequences. The application of combinatory assessment methods, however, could illuminate clinical benefits for “hard to reach” antisocial groups (Newbury-Helps et al., Citation2017) and extend to all points along the interpersonal violence continuum.

Finally, Keith’s is but one example of the complex types of personalities that may confound current mainstream assessment approaches, and more work is needed. Moving forward, methods of combining multilevel assessment data must be developed and refined, with case studies providing suitable vehicles for initial efforts. Theory-driven, data-supported operationalization of levels should also continue to be explored, with more-comprehensive selections of measures eventually being integrated in order to optimize “coverage” of functioning at each level. Research studies incorporating larger sample sizes might soon follow, and methods showing conceptual promise could then be empirically examined regarding their utility in treatment. With established empirical validity, clinicians might then begin to incorporate multilevel assessment into standard evaluation and treatment practices, where it may continue to advance, inform, and promote personality assessment science.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (564.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The author has no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Notes

1 A PsycInfo search using the search terms “serial homicide or serial killer or serial murderer” and “Rorschach” or “Rorschach Inkblot Test” or “personality assessment” or “projective tests” yielded no results.

2 It is important to note that Keith’s serial killing does not represent entirely—or even significantly—the sum of his behavior over the course of his lifetime. However, while it began in his middle thirties, it was an enduring pattern of behavior that lasted five years—nearly one-quarter of his adult lifetime at that point (and may well have continued were it not for his apprehension), and was woven seamlessly into his social environment and employment as a long-haul truck driver (which were also intertwined).

3 In forensic evaluations, other sources of Level I criminal behavior data could theoretically include victim and witness statements, surveillance and police body-worn camera footage, and even DNA evidence (suggesting a behavioral link between perpetrator and victim). Unfortunately, none of these were available here.

4 At the time of assessment, Keith had been incarcerated for approximately 22 years. As such, a valid argument could be made for the effects of long-term incarceration potentially impacting his performance on one or more assessment measures. However, the lion’s share of research in this area is decades old, fraught with methodological limitations, and aggregately suggests that while the psychological functioning of some inmates deteriorates in response to confinement, others show no significant change, and still others are marked by improved functioning (Wormith Citation1984). Additionally, longitudinal studies—which are rare—tend to have short time intervals (Dettbarn, Citation2012). Nonetheless, the present results should be considered within the context of Keith’s long-term incarceration (and aging), and attempts were made to do so when interpreting his data here.

5 When Complexity scores are outside of the average range (i.e., lower than 85 or higher than 115), it is recommended that the statistically-derived Complexity Adjusted scores also be plotted and interpreted, for the purposes of allowing the examiner to compare the examinee to other individuals of the same level of Complexity. In other words, the Complexity Adjusted scores estimate what an individual’s scores would be if his or her protocol had a median level of complexity (Meyer et al., Citation2011). I interpreted Keith’s Rorschach protocol using Complexity Adjusted scores, while also presenting his original raw scores for comparison. Both sets of scores are presented numerically and visually in Table 2. For the purpose of the present discussion, scaled scores (SS) mentioned below will represent Keith’s Complexity Adjusted scaled scores (i.e., from column 4), and will often be presented along with his raw scores (from column 2) and performance range descriptors (e.g., Average, Below Average).

6 See Footnote 4. Dettbarn (Citation2012) noted improvements in emotional stability and depression (as indicated by personality tests) in a longitudinal study of incarcerated individuals, compared over an average time frame of 14.6 years.

7 This comment may also be interpreted as incapacitating an already-vulnerable creature, which is analogous to his own killings and victims.

8 This score may also reflect possible efforts to shock, provoke, or entertain me—the examiner—given the quality of playfulness and absence of fear or dysphoria observed while Keith was describing disturbing contents.

9 Deliberate censoring may have also played a role in this low score

10 See Footnote 4. Ginter (Citation2020) noted that research suggests an “emotional flatness” often develops in incarcerated persons that negatively impacts their human interactions and understanding of others, and that higher PHR scores would therefore be expected from these individuals. In this context, Keith’s elevated PHR/GPHR ratio may also reflect the effects of long-term incarceration, though he did not endorse any emotional coldness, detachment, or flattened affectivity on the SCID-II.

11 Keith’s performance – verbal IQ discrepancy (P > V) resembles those associated with antisocial behavior across age, gender, and racial groups (Isen, Citation2010), though he is not characterized by the hallmark early academic failures theorized to play an important role in the development of antisociality. Previous studies (Dettbarn, Citation2012; Wormith, Citation1984) suggest the effects of long-term incarceration on his intellectual functioning would be minimal.

12 The only normative comparison made in this sample due to the comparatively high IQ scores characterizing the student and IQ-matched control groups (where mean RMET scores were approaching and even above 30).

13 Given Keith’s demographic characteristics, the five studies deemed most appropriate and relevant were those with English-speaking samples, healthy or “normal” adult participants, in which all 36 RMET items were administered and RMET scores were reported (Ahmed & Miller, Citation2011; Caroll & Chiew, Citation2006; Cook & Saucier, Citation2010; Kenyon et al., Citation2012; Valla et al., Citation2010). One limitation is that the participants in these samples were significantly younger than Keith, and age-related decline in ToM may have affected his RMET scores—though his intact EF suggests his reduced RMET performance may not be age-related (see Cho & Cohen, Citation2019).

14 The small “sample size” of RMET items (i.e., n = 36) likely reduced statistical power in these analyses. Some items were ambiguous in terms of positive or negative mental state valence.

15 Significant psychosocial stressors occurring at the time of the Keith’s first murder also suggest this may have played a role in the onset of his serial killing.

16 The empirical irony of these results from a serial killer who publicly communicated facts about his murders using anonymous messages signed with a smiling face should not be lost here.

17 Keith indicated that his mother was excluded from family trips when his father became ashamed of her significant weight gain. In the several months between his parents’ divorce and his mother’s death, Keith observed his father dating a new woman. About this, Keith stated, “Mother was home dying of cancer and he was out travelling around with his new girl.”

18 This theme of being “tolerated” resonates with Keith’s first murder. He reported that the catalyst for that event occurred while having sex with his victim, when she stated, “hurry up and get it over with.” At this point he became angry and violent, and began to strike her. He also mentioned that this reminded him of what his ex-wife used to say during sexual intercourse when they were married.

19 Keith was 30 years old when his mother succumbed to cancer. About this, he stated, “Want to hear something sad? A week before Mom passes away, Dad invites us kids up to say goodbye to her. He says: ‘go in there to kiss your mother goodbye.’ I went into her bedroom, laid next to her and had to explain why I couldn’t kiss her goodbye because it would have been the only kiss I would have given her in my life. Didn’t want to remember it that way. So we hugged instead.”

20 These included having an automobile battery explode near him at age 16, falling 25 feet from a climbing rope in a high school gym during wrestling practice at age 17, a head-on truck collision at age 19, and an end-over-end truck crash at age 33. He also experienced numerous sports-related head injuries while playing hockey (as a child) and boxing (as an adult), and suffered zinc poisoning while welding inside an enclosed garage at age 21. The “school fall” injury at age 17 is particularly noteworthy, as he also injured his left leg, subsequently required three operations and several years’ use of crutches, and was awarded a significant amount of money in a lawsuit.

21 For example, parental harsh punishment and warmth may indirectly affect adult antisocial behavior via intermediary factors such as adolescent conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits (Goulter et al., Citation2020). Putative genetic influences and gene-by-environment interactions must also be considered (Raine, Citation2013).

22 Keith reported his most satisfying sexual experiences occurred with his girlfriend following the breakup of his marriage. This woman reportedly frequently wanted sex, which was lustful and made Keith feel desired and not rushed, questioned, shamed, or judged.

23 Regarding the latter, Keith stated, “sex: if you get it, you get it… if you don’t, you don’t… that’s why we have prostitutes, right?… a prostitute on the road is a convenience.” Keith’s unwillingness to acknowledge even a normative sexual interest may reflect a number of factors, such as changes in his level of sexual desire due to age or being incarcerated, or a conscious effort to distance himself from the sexual aspects of his killings.

24 For example, in item 30 of the RMET, he mistook the “flirtatious” female face for “disappointed.” Keith’s interactions with his victims (predominantly sex workers, encountered while trucking) often occurred within sexualized and sexually-ambiguous contexts.

References

- Ahmed, F. S., & Miller, L. S. (2011). Executive function mechanisms of Theory of Mind. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 667–678.

- Angrilli, A., Sartori, G., & Donzella, G. (2013). Cognitive, emotional and social markers of serial murdering. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 27(3), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2013.771215

- Azores-Gococo, N. M., Brook, M., Teralandur, S. P., & Hanlon, R. E. (2017). Neuropsychological profiles of murderers of children. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(7), 946–962. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817699437

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test Revised Version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger Syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 42(2), 241–251.

- Benjamin, L. S. (1994). SASB: A bridge between personality theory and clinical psychology. Psychological Inquiry, 5(4), 273–316. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0504_1

- Bornstein, R. F. (2003). Behaviorally referenced experimentation and symptom validation: A paradigm for 21st-century personality disorder research. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.1.1.24056

- Brennan, G. M., & Baskin-Sommers, A. R. (2019). Physical aggression is associated with heightened social reflection impulsivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(5), 404–414.

- Carroll, J. M., & Chiew, K. Y. (2006). Sex and discipline differences in empathising, systemizing and autistic symptomatology: Evidence from a student population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 949–957.

- Chan, H. C., Beauregard, E., & Myers, W. C. (2015). Single-victim and serial sexual homicide offenders: Differences in crime, paraphilias and personality traits. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health: CBMH, 25(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1925

- Cho, I., & Cohen, A. S. (2019). Explaining age-related decline in theory of mind: Evidence for intact competence but compromised executive function. PLoS One, 14(9), e0222890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222890

- Cook, C. M., & Saucier, D. M. (2010). Mental rotation, targeting ability and Baron-Cohen's Empathizing-Systemizing Theory of Sex Differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 712–716.

- Culhane, S. E., Hildebrand, M. M., Mullings, A., & Klemm, J. (2016). Self-reported disorders among serial homicide offenders: Data from the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 16(4), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2016.1196099

- Dawood, S., & Pincus, A. L. (2016). Multisurface interpersonal assessment in a cognitive-behavioral therapy context. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(5), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2016.1159215

- Dettbarn, E. (2012). Effects of long-term incarceration: A statistical comparison of two expert assessments of two experts at the beginning and the end of incarceration. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 35(3), 236–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.02.014

- Douglas, K. S., Hart, S. D., Groscup, J. L., & Litwick, T. R. (2013). Assessing violence risk. In I. B. Weiner & R. K. Otto (Eds.), Handbook of forensic psychology (4th ed., pp. 385–442). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press.

- Fox, J. M., Brook, M., Stratton, J., & Hanlon, R. E. (2016). Neuropsychological profiles and descriptive classifications of mass murderers. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 30, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.014

- Freud, S. (1926). Inhibitions, symptoms and anxiety. in The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 20. Hogarth Press. 1959, pp. 75–176.

- Gacono, C. B., & Meloy, J. R. (1994). The Rorschach assessment of aggressive and psychopathic personalities. Routledge.

- Gacono, C. B. (1992). Sexual homicide and the Rorschach. British Journal of Projective Psychology, 37(1), 1–21.

- Gacono, C. B. (1997). Borderline personality organization, psychopathy, and sexual homicide: The case of Brinkley. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Contemporary Rorschach interpretation (pp. 217–237). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gacono, C. B., Meloy, J. R., & Bridges, M. R. (2000). A Rorschach comparison of psychopaths, sexual homicide perpetrators, and nonviolent pedophiles: Where angels fear to tread. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 757–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200006)56:6<757::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-I

- Geberth, V. J., & Turco, R. N. (1997). Antisocial personality disorder, sexual sadism, malignant narcissism, and serial murder. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 42(1), 49–60.

- Ginter, A., Berger, S. E., Parekh, B., & Miranda, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence of incarcerated populations as measured by the Rorschach Inkblot Technique. Open Access Journal of Addiction and Psychology, 3(2) https://doi.org/10.33552/OAJAP.2020.03.000559

- Goulter, N., McMahon, R. J., Pasalich, D. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2020). Indirect effects of early parenting on adult antisocial outcomes via adolescent conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(6), 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1613999

- Greco, C. M., & Cornell, D. G. (1992). Rorschach object relations of adolescents who committed homicide. Journal of Personality Assessment, 59(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5903_11

- Hanlon, R. E., Brook, M., Stratton, J., Jensen, M., & Rubin, M. H. (2013). Neuropsychological and intellectual differences between types of murderers: Affective/impulsive versus predatory/instrumental (premeditated) homicide. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(8), 933–948. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813479779

- Hanlon, R. E., Rubin, L. H., Jensen, M., & Daoust, S. (2010). Neuropsychological features of indigent murder defendants and death row inmates in relation to homicidal aspects of their crimes. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 25(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acp099

- Huprich, S. K., Gacono, C. B., Schneider, R. B., & Bridges, M. R. (2004). Rorschach Oral Dependency in psychopaths, sexual homicide perpetrators, and nonviolent pedophiles. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(3), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.585

- Isen, J. (2010). A meta-analytic assessment of Wechsler's P > V sign in antisocial populations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.003

- Juni, S. (2009). Conceptualizations of hostile psychopathy and sadism: Drive theory and object relations perspectives. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 18(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08037060701875977

- Kahn, M. W. (1965). A factor-analytic study of personality, intelligence, and history characteristics of murderers. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 227–228.

- Kahn, M. W. (1967). Correlates of Rorschach reality adherence in the assessment of murderers who plead insanity. Journal of Projective Techniques & Personality Assessment, 31(4), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/0091651X.1967.10120391

- Kaser-Boyd, N. (1993). Rorschachs of women who commit homicide. Journal of Personality Assessment, 60(3), 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6003_3

- Kenyon, M., Samarawickrema, N., DeJong, H., Van den Eynde, F., Startup, H., Lavender, A., Goodman-Smith, E., & Schmidt, U. (2012). Theory of mind in bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 377–384.

- Kim, M. Y., & James, L. J. (2015). Neurological evidence for the relationship between suppression and aggressive behavior: Implications for workplace aggression. Applied Psychology, 64(2), 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12014

- Krafft-Ebing, R. V. (1965). Psychopathia sexualis: A medico-forensic study. (F. S. Klaf, Trans.) Arcade Publishing. (Original work published 1886).

- Kraus, R. T. (1995). An enigmatic personality: Case report of a serial killer. Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine, 10(1), 11–24.

- Leary, T. (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality: A functional theory and methodology for personality evaluation. Resource Publications.

- Lewis, C. N., & Arsenian, J. (1982). Psychological resolution of homicide after 100 years. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46(6), 647–657. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4606_15

- Lombroso, C. (2006). Criminal man. (N. H. Rafter & M. Gibson, Trans.). Duke University Press. (Original work published 1876).

- McAdams, D. P. (1992). The Five-Factor Model in personality: A critical appraisal. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 329–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00976.x

- McCully, R. S. (1978). The laugh of Satan: A study of a familial murderer. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4201_12

- McCully, R. S. (1980). Satan’s eclipse: A familial murderer six years later. British Journal of Projective Psychology & Personality Study, 25(2), 13–17.

- Meloy, J. R. (1992). Revisiting the Rorschach of Sirhan Sirhan. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(3), 548–570. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5803_10

- Meloy, J. R., Gacono, C. B., & Kenney, L. (1994). A Rorschach investigation of sexual homicide. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6201_6

- Meyer, G. J., Viglione, D. J., Mihura, J. L., Erard, R. E., & Erdberg, P. (2011). Rorschach performance assessment system: Administration, coding, interpretation, and technical manual. Rorschach Performance Assessment System, LLC.

- Mihura, J. L., & Meyer, G. J. (Eds.). (2018). Using the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS). The Guilford Press.

- Monahan, J., Steadman, H. J., Silver, E., Appelbaum, P. S., Robbins, P. C., Mulvey, E. P., Roth, L. H., Grisso, T., & Banks, S. (2001). Rethinking risk assessment: The MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, L., & Viglione, D. J. (1992). Sexual disturbances, Rorschach sexual responses, and mediating factors. Psychological Assessment, 4(4), 530–536. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.4.530

- Newbury-Helps, J., Feigenbaum, J., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Offenders with antisocial personality disorder display more impairments in mentalizing. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(2), 232–255. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_246

- Nørbech, P. C. B. (2020). Sadomasochistic representations in a rage murderer: An integrative clinical and forensic investigation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(2), 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1506459

- Ostrosky-Solís, F., Vélez-García, A., Santana-Vargas, D., Pérez, M., & Ardila, A. (2008). A middle-aged female serial killer. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 53(5), 1223–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00803.x

- Perdue, W. C. (1964). Rorschach responses of 100 murderers. Corrective Psychiatry & Journal of Social Therapy, 10(6), 323–328.

- Perdue, W. C., & Lester, D. (1973). Those who murder kin: A Rorschach study. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 36(2), 606. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1973.36.2.606

- Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 515–526.

- Raine, A. (2013). The anatomy of violence. Vintage Books.

- Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Douglas, J. E. (1988). Sexual homicide: Patterns and motives. Lexington.

- Rorschach, H. (1942). Psychodiagnostics. Grune & Stratton. (Original work published 1921).

- Satten, J., Menninger, K., Rosen, I., & Mayman, M. (1960). Murder without apparent motive: A study in personality disorganization. American Journal of Psychiatry, 116, 48–53.

- Schalling & Rosen (1968). Porteus Maze differences between psychopathic and non-psychopathic criminals. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 7(3), 224–228.

- Schlesinger, L. B. (1998). Pathological Narcissism and serial homicide: Review and case study. Current Psychology, 17(2–3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-998-1007-6

- Schug, R. A., & Fradella, H. F. (2015). Mental illness and crime. Sage Publications.

- Schug, R. A., & Raine, A. (2009). Comparative meta-analyses of neuropsychological functioning in antisocial schizophrenic persons. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.004

- Sharp, C., & Vanwoerden, S. (2014). The developmental building blocks of psychopathic traits: Revisiting the role of theory of mind. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(1), 78–95.

- Silva, J. A., Ferrari, M. M., & Leong, G. B. (2002). The case of Jeffrey Dahmer: Sexual serial homicide from a neuropsychiatric developmental perspective. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 47(6), 15574J–155713. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS15574J

- Silva, J. A., Leong, G. B., Smith, R. L., Hawes, E., & Ferrari, M. M. (2005). Analysis of serial homicide in the case of Joel Rifkin using the neuropsychiatric developmental model. American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 26(4), 25–55.

- Stone, H. K., & Dellis, N. P. (1960). An exploratory investigation into the levels hypothesis. Journal of Projective Techniques, 24, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853126.1960.10380975

- Tull, M. T., Jakupcak, M., Paulson, A., & Gratz, K. L. (2007). The role of emotional inexpressivity and experiential avoidance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and aggressive behavior among men exposed to interpersonal violence. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 20(4), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701379249

- Valla, J. M., Ganzel, B. L., Yoder, K. J., Chen, G. M.., Lyman, L. T., Sidari, A. P., Keller, A. E., Maendel, J. W., Perlman, J. E., Wong, S. K. L., & Belmonte, M. K. (2010). More than maths and mindreading: Sex differences in empathizing/systemizing covariance. Autism Research, 3(4), 174–184.

- Vellante, M., Baron-Cohen, S., Melis, M., Marrone, M., Petretto, D. R., Masala, C., & Preti, A. (2013). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test: Systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 18(4), 326–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2012.721728

- Wormith, J. S. (1984). The controversy over the effects of long-term incarceration. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 26(4), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjcrim.26.4.423