Abstract

A representative sample (n = 2282) of Swedish adults completed the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, which measures moral intuitions concerning care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity. A subset (n = 607) completed a measure of intuitions about liberty. Measurement invariance was estimated across sex, age, education, income, left-right placement, religiosity, and party preference groups, based on multigroup confirmatory factor analyses of two-, three-, five-, six-, and eight-factor models, as well as bifactor models (with methods factors or a general factor). Acceptable configural, metric, and scalar invariance was obtained for most group comparisons, particularly based on the more complex models. The clearest exceptions were (1) configural non-invariance in comparisons involving participants with very low education or income, and (2) scalar non-invariance in comparisons of ideological groups based on three- and six-factor models but not the eight-factor model, which distinguished lifestyle liberty from government liberty.

Moral foundations theory (Graham et al., Citation2013; Haidt & Graham, Citation2007; Haidt & Joseph, Citation2004) suggests that intuitions about moral rightness rest upon at least five foundational moral concerns: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity. The first two are “individualizing” insofar as they make individuals sacrifice their self-interest for the welfare of others, while the latter three are “binding” insofar as they bind individuals into collectives for which they sacrifice their self-interest (Haidt, Citation2008). Subsequently, a sixth foundation, involving concern with liberty, was proposed as a potential extension of the taxonomy (Graham et al., Citation2013; Haidt, Citation2012).

This taxonomy is widely used in personality and social psychological research, and it has shed new light a wide variety of phenomena, including prosocial behavior, the psychology of law, receptivity to misinformation, mental illness, environmentalism, and immoral behavior (e.g., Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Jonason et al., Citation2017; Kang et al., Citation2016; Nilsson et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Silver, Citation2017). Nevertheless, the evidence for validity in the assessment of moral foundations based on the standard Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham et al., Citation2011) is mixed.

Factor structure

Confirmatory factor analysis based on data collected with the original 30-item MFQ (with six items for each foundation) has indicated acceptable fit for the original five-factor model (e.g., Davies et al., Citation2014; Graham et al., Citation2011; Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015; Yilmaz et al., Citation2016). Although the comparative fit index (CFI) frequently falls short of conventional fit criteria in these studies, this value is generally too low, and therefore not informative, when the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of the independence model is low (<.158 is a benchmark suggested by Kenny, Citation2015), which is typically the case here.

At the same time, some studies have suggested that the taxonomy overestimates the number of factors. Iurino and Saucier (Citation2020) found that the five-factor model failed to converge unproblematically across a diverse set of countries based on analyses of a 20-item short version of the original MFQ (with four items per foundation), although individualizing and binding items loaded on separate factors. Harper and Rhodes (Citation2021) found three factors corresponding to individualizing, binding, and liberty intuitions in British voters, based on exploratory factor analyses of the original 30-item MFQ and nine items concerning lifestyle and government liberty (Iyer et al., Citation2012). Similarly, confirmatory factor analyses of the 30-item MFQ have shown small differences in fit between a hierarchical model with individualizing and binding superordinate factors and the standard five-factor model (Davies et al., Citation2014; Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015).

By contrast, other studies have suggested that the foundations can be further subdivided. Zakharin and Bates (Citation2021) split the binding intuitions into five factors (clan loyalty, country loyalty, hierarchy, sanctity, and purity) based on an analysis of misfit in the five-factor model in a sample of UK respondents and subsequently found that this model improved fit in three replication samples. With respect to liberty, exploratory factor analyses have shown that items concerning government liberty and lifestyle liberty load on separate factors in the US and Sweden (Iyer et al., Citation2012; Nilsson, Erlandsson et al., Citation2020). It should be noted, however, that these fine-grained models are data-driven and atheoretical, while the original moral foundations model was based on theoretical criteria for demarcating moral foundations (see Graham et al., Citation2013).

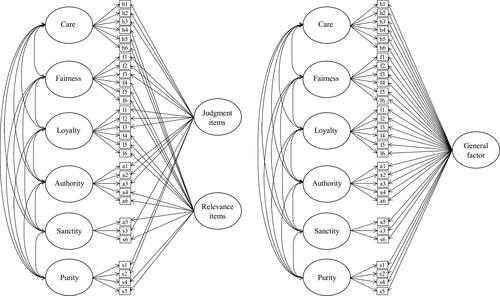

Zakharin and Bates (Citation2021) also tested a series of bifactor models, including models with method factors and a general factor, which yielded further improvements in model fit. The reason for including method factors is that the original MFQ was designed to include both items that capture abstract theories about what is morally relevant (i.e., “relevance items”) and items that capture contextualized moral judgments (i.e., “judgment items”) in order that it would be more diverse in terms of item formats and less susceptible to response biases (Graham et al., Citation2009, Citation2011). It is therefore conceivable that variation in responses stems in part from the foundation that the item taps into and in part from whether it is a judgment item or a relevance item, and this can be adequately modeled through a bifactor model (Reise, Citation2012). It is, furthermore, conceivable that some of the variation in the responses is shared among items from different foundations, by virtue of shared response effects or social desirability effects or because there might exist a general moral disposition that affects all moral foundations. General factors of this sort are ubiquitous in personality trait data, although their nature is debated. Some researchers have argued that there is a substantive general factor of personality associated with adaptive functioning at the apex of the trait hierarchy (e.g., Rushton & Irwing, Citation2011), while others have argued that general factors are measurement artifacts that stem from socially desirable responding (Bäckström et al., Citation2009) or halo effects (Anusic et al., Citation2009) and vary across instruments (Hopwood et al., Citation2011).

Measurement invariance

A further challenge is that even if good model fit is obtained, this does not necessarily mean that the measured constructs are invariant (or equivalent) across groups or populations. Measurement invariance is a prerequisite for accurate mean-level comparisons across groups (Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016). For instance, if purity items with religious connotations would load strongly on the purity factor in one group but weakly in another and the opposite was true for purity items without religious connotations, then the purity construct would have different meanings in the two groups (i.e., it would not be invariant). Because a high purity score would mean different things in the two groups, a mean-level comparison between the groups would not be meaningful. Furthermore, tests of associations between moral foundations and other constructs also implicitly assume that the moral foundations are invariant across subgroups in the sample (Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016). If, for instance, purity would be non-invariant across sex, age, or education groups, then correlations between purity and other constructs could be difficult to interpret.

The literature is replete with mean-level comparisons of moral intuitions across political and religious groups, sexes, and countries, as well as tests of association between moral foundations and other constructs (e.g., Atari et al., Citation2020; Feinberg & Willer, Citation2013; Graham et al., Citation2011; Iyer et al., Citation2012; Koleva et al., Citation2012; Nilsson, Erlandsson et al., Citation2020; Nilsson et al., Citation2019). Yet evidence of measurement invariance is scarce. Doğruyol et al. (Citation2019) obtained configural invariance (i.e., equivalence of model form) but not metric invariance (i.e., equivalence of item loadings on factors) in comparing Western and non-Western countries using the original MFQ, while Iurino and Saucier (Citation2020) failed to obtain configural invariance across three sets of diverse countries with a 20-item short version of the original MFQ. Davis et al. (Citation2016) obtained metric but not scalar invariance (i.e., equivalence in item intercepts) in a comparison of Black and White individuals in the US using the original MFQ. Furthermore, studies using network analysis have found substantial differences in the networks of the moral foundations between Iran and the US (Atari et al., Citation2020) and between liberals and conservatives in the US and New Zealand (Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2021). However, Atari et al. (Citation2020) found metric invariance in 96-99% and scalar invariance in 55-86% of cases in comparisons of men and women in 67 countries. These studies generally used the original 30-item MFQ (except for one study in Turner-Zwinkels et al., Citation2021).

Overview of research

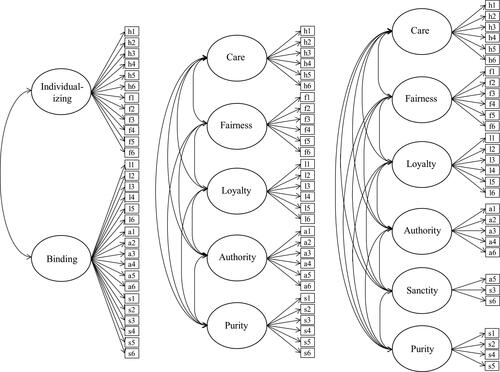

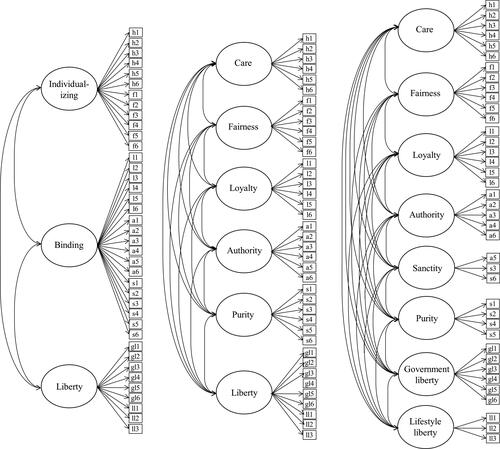

This article reports measurement invariance across sex, age, income, education, political self-placement, religious self-placement, and party preference groups. Swedish adults (n = 2282) completed the original MFQ (Graham et al., Citation2011), and a subset of them (n = 607) completed a measure of intuitions concerning liberty (Iyer et al., Citation2012). Measurement invariance was assessed in terms of confirmatory factor analyses based on two-, five-, and six-factor models, which are illustrated in ; and for the subset of participants, in terms of three-, six-, and eight-factor models, which are illustrated in . The most complex models were based on the seven-factor model specified by Zakharin and Bates (Citation2021), except that clan loyalty and country loyalty were represented by one loyalty factor to prevent multicollinearity. Follow-up analyses added method factors (relevance and judgment item types) and a general factor to the six-factor model (Zakharin & Bates, Citation2021), as illustrated in , to further probe the robustness of the results. These analyses permitted an assessment of measurement invariance based on the best performing out of all theoretically plausible models (that could be properly fitted) in the literature, and of the robustness of results across model variations, without relying on the heavily criticized (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014) approach in which a “partially invariant” model is fitted post hoc through stepwise model modifications.

Figure 3. Bifactor models with six moral intuitions factors and methods factors (left) or a general factor (right).

This research was conducted in Sweden, which is a social democratic welfare state and postindustrial democracy with a Protestant cultural heritage and one of the most secular, liberal, and egalitarian populations in the world (Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2010). Sweden has a multiparty system, in which the left (socialist, social democratic, and green parties) and the right (social liberal, liberal-conservative, and social conservative parties) differ primarily in terms of attitudes to equality, while social conservative (or traditionalist) ideology varies more within than between the left and the right (Nilsson, Montgomery et al., Citation2020). The familiar associations between right (vs. left) ideology and lower care and fairness and higher loyalty, authority, and purity (Graham et al., Citation2009; Haidt & Graham, Citation2007; Kivikangas et al., Citation2021) have been replicated in Sweden (Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015). The effects were the strongest for the fairness and authority foundations, while concern with purity was low across the ideological spectrum and not uniquely associated with right (vs. left) self-placement adjusting for other foundations (Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015), which may be explained in terms of the receding importance of traditional religiosity in Sweden (Inglehart & Welzel, Citation2010). The political value of blind patriotism is also particularly weakly endorsed by Swedes (Nilsson, Montgomery et al., Citation2020). Sweden is a good example of a modern liberal democracy, in which politics has increasingly become a means of self-expression, divorced from traditional religious and socio-economic structures (Caprara & Vecchione, Citation2017).

Materials and methods

Data, files for running the analyses, and supplemental documents are openly accessible: https://osf.io/38wsj

The research was carried out in compliance with all relevant regulations concerning research ethics. The Swedish law regarding ethics assessment of research on humans covers research that involves a physical operation, a manipulation, or the collection of biological materials or sensitive information that can be linked to an identified person. None of this applied to the current research. The participants were informed about the purposes and procedures of the research and provided their informed consent to participate.

Participants

Three samples that had been recruited from a nationwide panel of randomly selected Swedish adults were aggregatedFootnote1 (total N = 2282 after two participants with missing values had been excluded; 49.9% women, 50.1% men; Mage = 50.2, SD = 16.1). Quota sampling ensured national representativeness in terms of age, sex, and geographic region. Associations between moral foundations and other variables have been reported elsewhere (Nilsson, Montgomery et al., Citation2020; Nilsson et al., Citation2016, Nilsson, Erlandsson et al., Citation2020).

Measures

Moral foundations

Moral intuitions were measured with the original Swedish MFQ (Graham et al., Citation2011; Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015). It measures each of the five foundations with three relevance items and three judgment items. All participants responded on Likert scales ranging from 0 (“Not at all relevant”) to 5 (“Extremely relevant”) for relevance items and 0 (“Completely disagree”) to 5 (“Completely agree”) for judgment items. Some participants (n = 607) responded to two relevance items and seven judgment items concerning liberty (Iyer et al., Citation2012). These items were placed among similar MFQ items with identical response scales. Reliabilities are reported in “Supplement 1 – Reliabilities.pdf” (https://osf.io/97yek).

Groups

For tests of the two-, five-, and six-factor models of the MFQ, the participants were categorized into two sexes (men: n = 1142; women: n = 1138), eight age groups (constructed through automatic binning; ns from 228 to 338), four education groups (ns from 149 to 632), seven income groups (ns from 120 to 573), seven ideological self-placement groups (from farthest to the left to farthest to the right; ns from 138 to 448), four religious groups (from vey non-religious to very religious; ns from 164 to 371), and nine party preference groups (ns from 56 to 331). For the tests of three-, six-, and eight-factor models (with intuitions about liberty), the participants were categorized into two sexes (men: n = 301; women: n = 305), four age groups (ns from 126 to 169), two education groups (low: n = 306; high: n = 301), three income groups (low: n = 152; medium: n = 239; high: n = 157), and three left-right placement groups (left: n = 141; center: n = 271; right: n = 192). Detailed descriptions of items and categorizations can be found in “Supplement 2 - Groups.pdf” (https://osf.io/pndhu/).

Statistical procedure

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed in AMOS 25.0 with the maximum likelihood method and items as indicators. The most complex models initially contained seven and nine factors, but they were reduced to six and eight factors respectively because multicollinearity emerged in some cases (ϕ > 1) when clan loyalty and country loyalty were modeled as distinct factors. Measurement invariance was evaluated in terms of the fit of a multigroup model (configural invariance) and the reduction of fit when factor loadings (metric invariance) and intercepts (scalar invariance) were constrained to be equal across groups. Follow-up analyses were performed based on the six-factor model of the MFQ to probe sources of configural misfit. In some cases, complex bifactor models could not be properly fitted. All reported results are based on models that did run correctly.

The analyses were based on traditional tests of strict measurement invariance rather than the novel approach of testing approximate measurement invariance (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014; Luong & Flake, in press). This is because the goal of the research was to evaluate measures of moral intuitions rather than perform group-level comparisons. Methods that test approximate measurement invariance (e.g., the alignment method) permit meaningful group comparisons even when strict scalar invariance is not obtained.

Results

Fit statistics are shown in (two-, five-, and six-factor models of the MFQ) and (three-, six-, and eight-factor models of the MFQ and liberty). With respect to configural invariance, RMSEA was below .06 in every case, which indicates good fit, but the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) was frequently above .08, which indicates misfit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999); the RMSEA of the independence model was consistently very low (.047-.096), which renders the absolute value of CFI uninformative (Kenny, Citation2015).

Table 1. Measurement invariance for two-, five-, and six-factor models of moral intuitions (the MFQ).

Table 2. Measurement invariance for three-, six-, and eight-factor models of moral intuitions (the MFQ and liberty).

Changes were generally smaller than .015 in RMSEA, .030 (metric invariance) and .015 (scalar invariance) in SRMR, and .010 in CFI, which indicates metric and scalar measurement invariance (Chen, Citation2007; Cheung & Rensvold, Citation2002). There were some exceptions. Changes in CFI indicated marginal scalar non-invariance for sex based on the five-factor model (ΔCFI = .011), education based on two-, five-, and six-factor models (ΔCFI from .011 to .012), as well as left-right and party groups based on the six-factor model (ΔCFI = .015/.013) (see ). With items about liberty included, clear scalar non-invariance emerged for left-right groups based on three- and six-factor models (ΔCFI = .032/.031) but not the eight-factor model (ΔCFI = .008), and marginal scalar non-invariance emerged for sex based on all models (ΔCFI from .015 to .018) and age for three- and six-factor models (ΔCFI = .012) (see ).

The mismatch between RMSEA and SRMR as indicators of configural fit can likely be explained by the fact that SRMR increases and RMSEA decreases with the number of degrees of freedom (Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016). Simply reducing the number of age groups from eight to four (which reduces the degrees of freedom) yielded acceptable estimates (RMSEA = .041, SRMR = .0808; ΔCFI ≤ .004, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0025). Results from bifactor models with a general factor or method factors included, which are presented in , yielded further evidence of configural, metric, and scalar invariance across age groups and sexes.

Table 3. Measurement invariance for bifactor models.

Post hoc analyses revealed that configural misfit with respect to education and income was caused mainly by participants with the lowest education and income. More acceptable estimates could be obtained for income (RMSEA = .033, SRMR = .0908; ΔCFI ≤ .002, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0006) and education (RMSEA = .042, SRMR = .0747; ΔCFI ≤ .016, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0041) if participants with very low income (n = 120) and education (n = 149) respectively were excluded. With all participants included, even bifactor models that could be successfully fitted (including method factors for education and a general factor for income) failed to yield adequate SRMR estimates (see ). Adequate fit (on most fit indices) could be attained with all participants included only by collapsing the two highest and the two lowest groups, which reduced the number of income groups from seven to five (original model: RMSEA = .035, SRMR = .0880; ΔCFI ≤ .002, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0004; bifactor model: RMSEA = .029, SRMR = .0674; ΔCFI ≤ .001, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0002) and the number of educational groups from four to two (original model: RMSEA = .053, SRMR = .0754; ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0042; for metric invariance, ΔCFI = .005, for scalar invariance, ΔCFI = .020; bifactor model: RMSEA = .035, SRMR = .0483; ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0033; for metric invariance, ΔCFI = .008, for scalar invariance, ΔCFI = .014).

Similar post hoc analyses revealed that participants who scored the farthest to the left contributed the most to configural misfit. Excluding this group (n = 138) improved configural invariance (RMSEA = .032, SRMR = .0934; ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0038; for metric invariance, ΔCFI = .002; for scalar invariance, ΔCFI = .017). Improved fit could be obtained with all participants included as well when the seven initial groups were collapsed into leftist, center, and rightist categories (RMSEA = .045, SRMR = .0929; ΔCFI ≤ .005, ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0017). The only bifactor model for left-right orientation that could be properly fitted across all model steps (including method factors) indicated that adequate measurement invariance was obtained across these three groups (see ). With respect to party preference, slightly lower SRMR for configural fit could be obtained, along with adequate metric and scalar invariance on most indices, either with a bifactor model that included method factors (see ) or by collapsing party preferences into ideological groups (progressive left, social democratic, social liberal, liberal-conservative, social conservative; RMSEA = .033, SRMR = .0949; ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0010; for metric invariance, ΔCFI = .001, for scalar invariance, ΔCFI = .018). A bifactor model comparing ideological groups produced further improvement in fit (RMSEA = .024, SRMR = .0757; ΔRMSEA ≤ .001, ΔSRMR ≤ .0003; for metric invariance, ΔCFI = .003, for scalar invariance, ΔCFI = .016). No bifactor model could be properly fitted for religious groups, most likely due the low number of cases.

Discussion

This research was the first to comprehensively test measurement invariance of moral foundations across socio-demographic, ideological, and religious groups within a country’s population. Analyses of data from nationally representative samples of Swedish adults were performed based on all known models of moral foundations. Acceptable measurement invariance was obtained in most cases, which implies that moral foundations can be meaningfully compared across population strata. There were however some notable exceptions.

Measurement invariance and Non-Invariance

SRMR did frequently indicate a degree of configural misfit while RMSEA indicated good fit. In some cases, this mismatch could be attributed simply to the large number of degrees of freedom. Most notably, adequate fit estimates were obtained for comparisons across age groups when the number of groups was reduced, which indicates that the high initial SRMR is not a cause for concern. In other cases, the high SRMR for configural fit proved to be more problematic. This was true particularly for comparisons across education and income groups, due to greater model misfit among participants who were the lowest on education and income. This finding suggests that caution should be exercised in making comparisons across groups that differ substantially in terms of education and income. The MFQ was originally developed and validated based on data from self-selected online samples with disproportionately high education (Graham et al., Citation2011). It is therefore possible that the standard models do not generalize well to other social groups.

It is also conceivable that the overrepresentation of immigrants from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia in low educated and unemployed segments of the Swedish population (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018, Citation2021) contributed to model misfit in these groups. Ethnicity, country of birth, or parents’ country of birth were unfortunately not measured in this research. This is a significant limitation. Some recent studies have suggested that the original moral foundations taxonomy may fail to account for the structure of moral intuitions outside of the Western cultural sphere (Atari et al., Citation2020; Iurino & Saucier, Citation2020). Future studies should therefore also take potential measurement non-invariance across, for instance, ethnic, migrant, or linguistic groups within countries across the world into consideration. Measurement invariance across population strata may be lower particularly in countries with greater social and economic disparities or greater demographic and linguistic diversity. Future studies may, furthermore, benefit from recent advances in the quantification of cultural distance between and within nations (Muthukrishna et al., Citation2020). Some past studies (e.g., Doğruyol et al., Citation2019) have relied on a crude dichotomy between WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) and non-WEIRD populations (for a critique, see Apicella et al., Citation2020).

With respect to political orientation, the findings were mixed. SRMR indicated a degree of misfit for groups partitioned in terms of party preference and self-placement on a scale from left to right. Bifactor models with method factors (for judgment- and relevance items) were needed to obtain adequate configural, metric, and scalar invariance on all fit indices for the MFQ. There was, however, clear scalar non-invariance across left-right self-placement groups when the analyses were based on three- and six-factor models of the MFQ together with intuitions about liberty (). A likely explanation is that the liberty scale (Iyer et al., Citation2012) encompasses different types of liberty, which differ in importance along the political spectrum. Indeed, the scalar non-invariance disappeared when the analyses were based on the eight-factor model, which distinguished lifestyle liberty and freedom from the government. This finding shows that it important to subdivide intuitions about liberty into smaller components when comparisons across political groups are made.

The comparisons across sexes also yielded scalar non-invariance, albeit marginally. This result persisted across model variations. In cases such as this, a statistical method that does not require exact measurement invariance can be used to make comparisons across groups (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014; Marsh et al., Citation2018). Indeed, Atari et al. (Citation2020) were able to properly compare men and women in terms of moral foundations using this approach, and Brandt et al. (Citation2021) recently used it to estimate relations between left-right self-placement and scales measuring authoritarian and egalitarian preferences (which are related to the moral foundations).

Although the purpose of the current research was to investigate measurement invariance, it may be noted that results of subsequent mean-level comparisons between political groups and sexes (see “Supplement 3: Demographic differences.pdf”: https://osf.io/uhjxt/) were similar to those reported in other studies. In a recent meta-analysis, Kivikangas et al. (Citation2021) found that right (vs. left) self-placement was robustly negatively associated with the care and fairness foundations and positively associated the loyalty, authority, and purity foundations across countries, while social conservative (vs. liberal) self-placement was most strongly associated with loyalty, authority, and purity, particularly in European countries. Similarly, social democratic (vs. progressive) party preference on the left and social conservative (vs. liberal) party preference on the right were most robustly associated with intuitions concerning loyalty, authority, purity, and sanctity, while right (vs. left) self-placement and party preference were consistently associated with all foundations in the expected manner in the current researchFootnote2. Atari et al. (Citation2020) found that women tended to score higher than men on the care, fairness, and purity foundations across countries. In the current study, women scored higher on the care and fairness foundations but marginally lower on the authority and sanctity foundations.

Dimensionality of moral foundations

The results of the tests of measurement invariance were similar between calculations based on two- and five-factor models of the MFQ and three- and six-factor models of the MFQ and liberty, consistent with findings indicating that the individualizing-binding distinction captures most of the variance in intuitions about care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity in Western countries (Davies et al., Citation2014; Harper & Rhodes, Citation2021; Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015). The six- and eight-factor models (modified from Zakharin & Bates, Citation2021, and Iyer et al., Citation2012) tended to perform marginally better than the original models. This is consistent with the notion that religiosity and intuitions about purity may be distinct at least in highly secular countries such as Sweden (Nilsson & Erlandsson, Citation2015); religiosity was indeed a lot more strongly associated with sanctity than with purity in this study and the sanctity items were endorsed to a much lesser extent than the purity items were (“Supplement 3: Demographic differences.pdf”: https://osf.io/uhjxt/). These results cast doubt on the universal viability of unidimensional models of moral intuitions concerning purity and liberty, as assessed with the original scales (Graham et al., Citation2011; Iyer et al., Citation2012). They suggest that a theoretical framework with at least eight factors organized under at least three broader domains (individualizing intuitions subsuming care and fairness; binding intuitions subsuming loyalty, authority, purity, and sanctity; liberty intuitions subsuming lifestyle liberty and government liberty) could be an improvement over previous models for the original scales in terms of optimizing the combination of explanatory parsimony and fit.

At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that what is to count as a moral foundation in the first place is a theoretical question. Specific theoretical criteria for foundationhood have been proposed (Graham et al., Citation2013), and these are not necessarily satisfied by factors derived from empirical analyses. Depending on whether a factor is considered to represent a distinct moral foundation or not, model fit could be optimized either through modification of the taxonomy or through refinement of the measure. Indeed, Graham et al. (Citation2013) envisioned a theory-method co-evolution of moral foundations theory, through which theoretical constructs would inspire new measures and data from measurement would guide theory development.

It is surprising that the MFQ has not been subjected to more psychometric refinement given its widespread adoption as an assessment tool in psychological science and the intent of its creators. However, Atari et al. (Citation2022) did recently propose a first revised version of the MFQ (the MFQ-2). They broke the fairness foundation into separate equality and proportionality foundations on theoretical grounds while retaining the other four original foundations. They constructed a new pool of moral judgment items to measure the six posited foundations and thereafter refined and validated the instrument across a culturally diverse set of populations. The MFQ-2 generally exhibited desirable psychometric characteristics and outperformed the original MFQ (the MFQ-1) in terms of capturing variance in other relevant moral, political, and personality psychological constructs. Another notable finding was that the structure (or network) of the moral foundations failed to conform to the binding-individualizing distinction in some populations that are culturally distant from WEIRD contexts (e.g., Nigeria, Morocco, Peru, and Saudi Arabia). Hierarchical models that rely on this superordinate distinction may therefore not be viable in all cultural contexts.

The recent development of the MFQ-2 represents a major advance. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that some of the foundations have seemingly become narrower (and perhaps therefore more homogeneous). In the MFQ-2, the purity items focus mainly on religiously based sexual taboos (e.g., “I admire people who keep their virginity until marriage”), while the MFQ-1 contains items that focus on disgust as well (e.g., “People should not do things that are disgusting, even if no one is harmed”); and in the MFQ-2, all of the strongly loading loyalty items concern country loyalty (e.g., “Everyone should defend their country, if called upon”). The purity and loyalty foundations also exhibited the most measurement non-invariance across populations and the strongest associations with cultural distance (with higher scores among non-WEIRD populations: Atari et al., Citation2022; see also Saucier et al., Citation2015). The findings of Zakharin and Bates (Citation2021) and the results of the current research illustrate the possibility of distinguishing between religiously based purity (or sanctity) and disgust-based purity and between loyalty to an impersonal collective, such as a nation, and loyalty to narrower communities, such as family and friends, with whom the individual has personal relationships (see also Voelkel & Brandt, Citation2019). Future studies might explore, for instance, whether more fine-grained hierarchical models with separate facet scales that are tailored to measure different types of purity, loyalty, and liberty intuitions could improve predictive power and measurement invariance of the MFQ-2 even more, particularly with highly secular and liberal cultural settings taken into consideration. Such a model could potentially remain faithful to the overarching theoretical structure posited by moral foundations theorists (Atari et al., Citation2022; Haidt, Citation2012) while further increasing the breadth and power of the model.

Concluding remarks

The results of this research suggest that the original MFQ permits meaningful generalizations across population strata, at least in WEIRD populations. Caution should be exercised particularly with respect to generalizations that encompass groups with very low education and income. Attention should be paid also to the distinctions between lifestyle and government liberty and between religious purity (or sanctity) and disgust-based moral judgments. Above all, researchers should seek to further synthesize theoretical analyses of the nature of moral intuitions and empirical findings from culturally, socio-demographically, and linguistically diverse populations. Sensitivity to contextual contingencies is essential for the development and proper application of increasingly sophisticated measures.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/38wsj/. To obtain the author's disclosure form, please contact the Editor.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (241.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The author reports that there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data set is accessible through the Open Science Framework project-page: https://osf.io/hrv4s/

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The dataset initially included data from four samples. One sample was dropped after peer review because the Likert response scale for MFQ judgment items differed between this sample (1 to 7) and the others (0 to 5).

2 For Sample 1 (see “Supplement 2 – groups.pdf”: https://osf.io/pndhu/), more thorough analyses of associations between binding and individualizing sum scores and party preference have been reported elsewhere (Nilsson, Montgomery, et al., Citation2020)

References

- Anusic, I., Schimmack, U., Pinkus, R. T., & Lockwood, P. (2009). The nature and structure of correlations among Big Five ratings: The halo-alpha-beta model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1142–1156. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017159

- Apicella, C., Norenzayan, A., & Henrich, J. (2020). Beyond WEIRD: A review of the last decade and a look ahead to the global laboratory of the future. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(5), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.015

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Multiple-group factor analysis alignment. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.919210

- Atari, M., Haidt, J., Graham, J., Koleva, S., Stevens, S. T., & Dehghani, M. (2022, March 4). Morality beyond the WEIRD: How the nomological network of morality varies across cultures. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/q6c9r

- Atari, M., Graham, J., & Dehghani, M. (2020). Foundations of morality in Iran. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(5), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.014

- Atari, M., Lai, M. H. C., & Dehghani, M. (2020). Sex differences in moral judgements across 67 countries. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 287. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1201

- Bäckström, M., Björklund, F., & Larsson, M. R. (2009). Five-factor inventories have a major general factor related to social desirability which can be reduced by framing items neutrally. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.013

- Brandt, M. J., He, J., & Bender, M. (2021). Registered report: Testing ideological asymmetries in measurement invariance. Assessment, 28(3), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120983891

- Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2017). Personalizing politics and realizing democracy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199982868.001.0001

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Davies, C. L., Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire: Independent scale validation in a New Zealand sample. Social Psychology, 45(6), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000201

- Davis, D. E., Rice, K., Van Tongeren, D. R., Hook, J. N., DeBlaere, C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Choe, E. (2016). The moral foundations hypothesis does not replicate well in Black samples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(4), e23–e30. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000056

- Doğruyol, B., Alper, S., & Yilmaz, O. (2019). The five-factor model of the moral foundations theory is stable across WEIRD and non-WEIRD cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109547

- Feinberg, M., & Willer, R. (2013). The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science, 24(1), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612449177

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral Foundations Theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 55–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141

- Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

- Haidt, J. (2008). Morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 3(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00063.x

- Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Pantheon.

- Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

- Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004). Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus, 133(4), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526042365555

- Harper, C. A., & Rhodes, D. (2021). Reanalysing the factor structure of the moral foundations questionnaire. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1303–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12452

- Hopwood, C. J., Wright, A. G., & Donnellan, M. B. (2011). Evaluating the evidence for the general factor of personality across multiple inventories. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(5), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.06.002

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2010). Changing mass priorities: The link between modernization and democracy. Perspectives on Politics, 8(2), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710001258

- Iurino, K., & Saucier, G. (2020). Testing measurement invariance of the moral foundations questionnaire across 27 countries. Assessment, 27(2), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118817916

- Iyer, R., Koleva, S., Graham, J., Ditto, P., & Haidt, J. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLoS One, 7(8), e42366 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042366

- Jonason, P. K., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Okan, C. (2017). Good vs. evil: Predicting sinning with dark personality traits and moral foundations. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.002

- Kang, L. L., Rowatt, W. C., & Fergus, T. A. (2016). Moral foundations and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A preliminary examination. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 11, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2016.06.004

- Kenny, D. A. (2015, November 24). Measuring model fit. Retrieved January 31, 2022, from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm

- Kivikangas, J. M., Fernández-Castilla, B., Järvelä, S., Ravaja, N., & Lönnqvist, J.-E. (2021). Moral foundations and political orientation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(1), 55–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000308

- Koleva, S. P., Graham, J., Iyer, R., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially Purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006

- Luong, R., & Flake, J. K. (in press). Measurement invariance testing using confirmatory factor analysis and alignment optimization: A tutorial for transparent analysis planning and reporting. Psychological Methods.

- Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Parker, P. D., Nagengast, B., Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., & Dicke, T. (2018). What to do when scalar invariance fails: The extended alignment method for multi-group factor analysis comparison of latent means across many groups. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 524–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000113

- Muthukrishna, M., Bell, A. V., Henrich, J., Curtin, C. M., Gedranovich, A., McInerney, J., & Thue, B. (2020). Beyond Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) psychology: Measuring and mapping scales of cultural and psychological distance. Psychological Science, 31(6), 678–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620916782

- Nilsson, A., & Erlandsson, A. (2015). The moral foundations taxonomy: Structural validity and relation to political ideology in Sweden. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.049

- Nilsson, A., Erlandsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2016). The congruency between moral foundations and intentions to donate, self-reported donations, and actual donations to charity. Journal of Research in Personality, 65, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.001

- Nilsson, A., Erlandsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2019). The complex relation between receptivity to pseudo-profound bullshit and political ideology. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(10), 1440–1450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219830415

- Nilsson, A., Erlandsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2020). Moral foundations theory and the psychology of charitable giving. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2256

- Nilsson, A., Erlandsson, A., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2020). Who are the opponents of nudging? Insights from moral foundations theory. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2020.1756241

- Nilsson, A., Montgomery, H., Dimdins, G., Sandgren, M., Erlandsson, A., & Taleny, A. (2020). Beyond ‘liberals’ and ‘conservatives’: Complexity in ideology, moral intuitions, and worldview among Swedish voters. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2249

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review : DR, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

- Reise, S. P. (2012). Invited paper: The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(5), 667–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2012.715555

- Rushton, P., & Irwing, P. (2011). The general factor of personality: Normal and abnormal. In T. Chamorro-Premuzic, S. von Stumm, & A. Furnham (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences (pp. 132–161). Wiley Blackwell.

- Saucier, G., Kenner, J., Iurino, K., Bou Malham, P., Chen, Z., Thalmayer, A. G., Kemmelmeier, M., Tov, W., Boutti, R., Metaferia, H., Çankaya, B., Mastor, K. A., Hsu, K.-Y., Wu, R., Maniruzzaman, M., Rugira, J., Tsaousis, I., Sosnyuk, O., Regmi Adhikary, J., … Altschul, C. (2015). Cross-cultural differences in a global “survey of world views. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114551791

- Silver, J. R. (2017). Moral foundations, intuitions of justice, and the intricacies of punitive sentiment. Law & Society Review, 51(2), 413–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12264

- Statistics Sweden. (2018). Utrikes föddas utbildningsbakgrund 2017 [Educational background 2017 among foreign born persons]. https://www.scb.se/publikation/36497

- Statistics Sweden. (2021). Sysselsättning bland flyktingar och deras anhöriga 2019 [Employment by refugees and their family members in 2019]. https://www.scb.se/publikation/41967

- Turner-Zwinkels, F. M., Johnson, B. B., Sibley, C. G., & Brandt, M. J. (2021). Conservatives' moral foundations are more densely connected than liberals' moral foundations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220916070

- Voelkel, J. G., & Brandt, M. J. (2019). The effect of ideological identification on the endorsement of moral values depends on the target group. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(6), 851–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218798822

- Yilmaz, O., Harma, M., Bahçekapili, H. G., & Cesur, S. (2016). Validation of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire in Turkey and its relation to cultural schemas of individualism and collectivism. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.090

- Zakharin, M., & Bates, T. C. (2021). Remapping the foundations of morality: Well-fitting structural model of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire. PLoS One, 16(10), e0258910 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258910