Abstract

Traditionally, narcissistic characteristics are considered relatively stable, although clinical accounts and recent research show that additional narcissistic states are variable and fluctuate in actuality. Narcissism research tends to focus on cross-sectional, group-based, trait approaches. Momentary ecological assessments allow one to discover individuals’ true colors by observing narcissistic experiences while they unfold in real-time and real-world settings. Within momentary ecological assessments, inspecting single cases enables insight into individual dynamics and presentations. Consequently, this research collected grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic trait and state data 10 times a day for 6 days. Based on the highest trait scores, two individual cases are presented per category: predominantly grandiose narcissistic, predominantly vulnerable narcissistic, and combined narcissistic. Overall, the descriptions provide evidence for the dynamics within and between grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic states. Further, broad patterns for each narcissistic dimension were uncovered, in which the grandiose subdimension experienced mainly grandiosity, and the vulnerable and combined subdimensions experienced both grandiosity and vulnerability. Out of the three, the combined subdimension experienced the highest instability and levels of daily vulnerability. However, each individual case showed unique fluctuation patterns that highlight the importance of personalized, real-life assessments in research and clinical care.

Research investigating individuals’ everyday expressions of psychopathologies is gathering momentum. One of the areas benefitting from daily life research is narcissism. Generally, narcissism is characterized by a cognitive-affective preoccupation with the self. One conceptualization of narcissism proposes two subdimensions within the original dimension: grandiose narcissism (GN) and vulnerable narcissism (VN; Cain et al., Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2011). GN is, inter alia, linked to higher self-esteem, entitlement, aggression, superiority, and win–lose interpersonal approaches, whereas VN is related to contingent self-esteem, negative affectivity, a need for external validation, and social isolation (e.g., Miller et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2018; Pincus et al., Citation2014). Alike personality (disorders), narcissism is largely thought to be inflexible over time (e.g., Cobb-Clark & Schurer, Citation2012; Grapsas et al., Citation2020), with diagnostic criteria stating that the “pattern is stable” across time and situations (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022, p. 735). However, this apparent stability contradicts clinical observations (Pincus et al., Citation2014) as diagnostic criteria based on results from global, retrospective, laboratory, or cross-sectional designs might not always align with real-life presentations that include momentary processes and context sensitivity. Indeed, an increasing amount of evidence suggests that personality, whether it be traits or disorders, includes rather dynamic elements (Debast et al., Citation2014; Warner et al., Citation2004). Thereupon, an updated theoretical conceptualization of narcissism was brought forward that incorporates the whole trait theory, suggesting interacting trait (general characteristics), state (momentary emotions, behaviors, and thoughts), and within-situation (situational triggers) levels (Ackerman et al., Citation2019). Consequently, narcissistic manifestations need to be investigated outside of previous cross-sectional, between-person designs to test this conceptualization.

To move observations into daily life, methods such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA; Shiffman et al., Citation2008; Stone & Shiffman, Citation1994) are gaining popularity. EMA can assess individuals multiple times a day, over days, weeks, or months, to gain insight into dynamic processes and individual differences that unravel in actuality. Indeed, EMA research investigating narcissism and its state-trait isomorphisms (i.e., trait-related behavior; e.g., Fleeson, Citation2001; Kingsbury & Bernard, Citation2023) demonstrated that narcissistic expressions in daily life fluctuate, with higher traits relating to stronger, more frequent fluctuations (e.g., Edershile & Wright, Citation2021; Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023). Specifically, narcissistic states varied (general movement), were unstable (high magnitudes in movement), and showed inertia (lingering emotions), from moment to moment within individuals. Further, theoretically, GN and VN are viewed as two different entities sharing a core. This separation was first challenged by research using retrospective clinical observations (Gore & Widiger, Citation2016; Hyatt et al., Citation2018). Additionally, EMA research found cross-over oscillations between them in which GN individuals exhibited both GN and VN states in daily life (Edershile & Wright, Citation2021). Primarily, this cross-over occurred when grandiose leadership/authority and exploitativeness/entitlement traits were higher (Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023). Contrastingly, VN individuals maintained mostly VN states (Edershile & Wright, Citation2021), yet VN egocentrism related to greater average GN levels. Although these quantitative studies are crucial to further our understanding of dynamic processes in daily life, they tend to portray participants as a homogeneous group. Generalized group-level results are difficult to apply to an individual’s symptoms (McDonald et al., Citation2017; Scholten et al., Citation2022) and variations, for example, in treatment responses (Verhagen et al., Citation2016). Thus, considering an individual’s idiographic and heterogeneous cases is critical (Voigt et al., Citation2018), as they enable a tailored understanding of an individual’s experience. Accordingly, investigating theoretical assumptions within an individual is recommended by using N-of-1 designs (Craig et al., Citation2008; Kwasnicka et al., Citation2017). The aim of idiographic approaches is to retreat from the idea that individual variation is a source of noise and rather appreciate it as an element of clinical characterization (Verhagen et al., Citation2022). Subsequently, this study aims to bring the previous quantitative research regarding everyday narcissism dynamics to life. It will provide additional details and explicit examples of an individual’s narcissistic fluctuations to vivify underlying theories and illustrate characteristics of specific cases. Two cases for each narcissistic trait variation will be presented: predominantly grandiose, predominantly vulnerable, and combined grandiose and vulnerable. Their cases will be presented to provide insight into whether they experience GN and VN fluctuations and how their state experiences interact with their individual trait presentations. Based on the previous EMA research (Edershile & Wright, Citation2021; Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023), it would be expected that individuals who classified as predominantly grandiose experience mostly GN states and occasional VN states, whereas VN individuals experience mostly VN states and few to no GN states. The combined cases have not been previously considered within the narcissistic daily life literature. Although the three-factor narcissism solution (Crowe et al., Citation2019) proposes a third dimension (self-centered antagonism) between GN and VN, this represents a shared core rather than combined GN and VN characteristics. However, clinical experiences recognize that GN and VN may cooccur. A recent meta-analysis investigated this and found that VN increased at high levels of GN (Jauk et al., Citation2022). Moreover, clinical research found that, for example, relatives describe narcissistic individuals in terms of both grandiose and vulnerable characteristics (Day et al., Citation2020). Indeed, many clinically driven theories support cooccurrence of GN and VN, at least from a state perspective. For instance, in schema therapy, narcissistic individuals could experience aggrandizer modes followed by vulnerable child modes (Behary & Dieckmann, Citation2011). Similarly, the dual-action model of narcissism proposes compensatory grandiose and negative vulnerable schemas that can be situationally triggered and inhibit each other (e.g., Sachse, Citation2020). Subsequently, one could expect our combined cases to fluctuate regularly between GN and VN states but to be mutually exclusive.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of a larger data set (N = 230) collected in a community sample to investigate narcissistic states in daily life (for more details, please see Freund, Castro-Alvarez, et al., Citation2023; Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023).Footnote1 From this pool, n = 6 were selected. Only participants who completed more than 80% of the EMA question rounds (i.e., more than 48 out of 60) and did not take psychoactive medication were considered. From these, we picked the two participants with the highest grandiose narcissistic trait averages with below sample mean VN traits, two with the highest vulnerable narcissistic trait averages with below sample mean GN traits, and two with the highest scores when the grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic trait averages were combined.

Materials

Grandiose narcissistic traits

GN traits were assessed with the 37-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; Morf & Rhodewalt, Citation1993; Raskin & Hall, Citation1979). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The NPI contains four subcomponents: Leadership/Authority, Self-Absorption/Self-Admiration, Superiority/Arrogance, and Exploitativeness/Entitlement (Emmons, Citation1987). The NPI has a high test–retest value (r = .81; del Rosario & White, Citation2005), adequate to excellent internal consistencies (α = .68–.87; Brown & Zeigler-Hill, Citation2004; Emmons, Citation1987), and good construct validity (r = .37–.71; Raskin & Terry, Citation1988).

Vulnerable narcissistic traits

VN traits were measured with the 10-item Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, Citation1997). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The HSNS contains two subcomponents: Oversensitivity to Judgment and Egocentrism (Fossati et al., Citation2009). It has good test–retest reliability (r = .63), adequate internal consistencies ranging from α = .62 to .71 (Fossati et al., Citation2009), and good construct validity (Hendin & Cheek, Citation1997).

Grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic states

Grandiose states in daily life were measured on a 7-point Likert scale using four items “I feel glorious/prestigious/brilliant/powerful.” Vulnerable states were measured using the four items “I feel ignored/misunderstood/resentful/underappreciated.” The items were the highest loading factors (Edershile et al., Citation2019; Edershile & Wright, Citation2021), collected from the Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (Rosenthal et al., Citation2020) and Narcissistic Vulnerability Scale (Crowe et al., Citation2018). The items for each narcissistic dimension were averaged to form a grandiose and a vulnerable global momentary assessment score. Previous reliability of the scales was adequate (ωwithin = .73−.80; ωbetween = .95−.97; ωwithin = .78−.80; ωbetween = .95−.98; Edershile & Wright, Citation2021).

Additional trait and state measures

Narcissism tends to relate to impairments in interpersonal behaviors that could impact narcissistic experiences in daily life. Two trait measurements were added to provide a supplemental context on the cases’ general interpersonal functioning. First, the Interpersonal Adjectives Scale (IAS-R; Wiggins et al., Citation1988) assessed the interpersonal circumplex (interpersonal traits, behaviors, and motives) that previously linked GN to cold-dominant and VN to cold-submissive functioning (Du et al., Citation2022). Second, the Communion-Agency Scale (Li et al., Citation2007) assessed mitigated and unmitigated agency and communion; that is, the unwilling or sincere focus on the self or others. GN was previously linked to describing oneself as positively agentic (e.g., intelligent) and negatively communal (e.g., unemphatic; Grijalva & Zhang, Citation2016).

Moreover, participants received a morning questionnaire each participation day, asking about their hours of sleep and perceived sleep quality. Further, to add context to the measured instances, the EMA rounds included questions about participants’ current experiences. Two items measured a threatened ego, or experiencing self-image peril (“I am ashamed of myself” and “I am a failure”), one item assessed dominance (“How do you currently feel?” Submissive to dominant), one item measured affiliation (“How do you currently feel?” Hostile/cold to caring/friendly), one item assessed agency, or self-enhancement focus (“I want to get ahead of others”), one item measured communion, or social focus (“I want to get along with others”), nine items assessed positive and negative affect (e.g., “I feel content/down/cheerful”), and eight items enquired about the current activity and previous events (e.g., “What are you doing,” “Who are you with,” or “How was the event?”). For the full list of EMA items, please see https://osf.io/4gk6e.

Procedure

The research was completed online during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. After filling out demographical data and trait measures, participants started the EMA data collection the following Monday. Using the mEMA app (https://ilumivu.com), participants received one morning questionnaire and 10 EMA question rounds per day for 6 days. The rounds consisted of 31 questions that took about 2 min to complete. They started at the participants’ usual wake-up time, were semirandomized across 75-min intervals, and ended after 12 hr. Participants were prompted through push notifications to complete new question rounds within 15 min. After participation, they received an Amazon voucher worth up to 35€.

Data processing

Means and standard deviations were calculated for each participant for each variable. Z scores were calculated for each baseline variable based on the larger sample (N = 230). Pearson correlations were conducted between the global narcissistic states and the other state variables using SPSS version 27. Additionally, to give meaning to the correlations on a larger scale, the correlations were repeated using the full sample, and their r values were computed into z scores for each participant. Moreover, as markers for within-person variability, instability, and inertia within the GN and VN states, the instantaneous standard deviation, mean square successive difference, and inertia coefficients were calculated using the R packages dplys (Wickham et al., Citation2023) and lme4 (Bates et al., Citation2023).Footnote2

Case descriptions

Predominantly grandiose

Emma

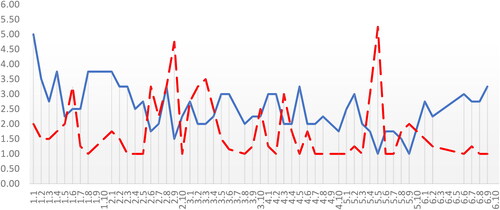

Our first case, Emma, is a Dutch female who was 20 years old at the time of participation. She completed high school, was a student, and was in a relationship. She completed 87% of the EMA question rounds. She spent most of her time at home, alone, working, or relaxing (). Emma scored comparatively high on GN traits and low on VN traits ().Footnote3 Her interpersonal circumplex scores suggest that she perceived herself to be generally dominant, arrogant, and extraverted while being warm and agreeable (). This is further reflected in her relatively high agency and communion traits.

Figure 1. Plots of each case’s interpersonal circumplex. Note. PA = assured-dominant, HI = unassured-submissive, BC = arrogant-calculating, JK = unassuming-unargumentative, DE = cold-hearted, LM = warm-agreeable, FG = aloof-introverted, NO = gregarious-extraverted.

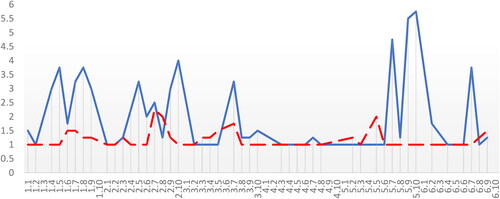

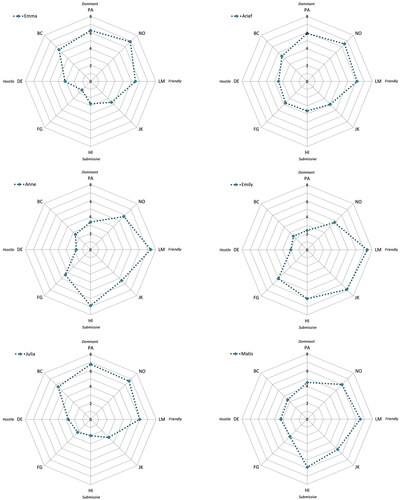

Figure 2. Emma’s daily grandiose (solid, blue) and vulnerable (dashed, red) narcissistic states. Note. The y-axis shows the momentary narcissistic state endorsement; the x-axis shows the consecutive ecological momentary assessment (EMA) question rounds starting from Day 1, Round 1 on the left.

Table 1. Means (standard deviations) and time percentages of activity data for each case.

Table 2. Average means of the trait items for each case.

In daily life (), this trend continued with relatively high dominance, affiliation, and communion endorsements. Her affect seemed regular, on average, on a day-to-day basis, with positive affect being in the midrange and negative affect being on the lower end. Emma’s grandiosity and vulnerability in daily life reflected her trait scores. She scored relatively high on grandiose states, which were more or less evenly split across the four items (brilliant, glorious, powerful, and prestigious). Although Emma did not engage in vulnerable states extensively (), she endorsed feeling resentful the most and with the largest variability out of the four vulnerable state items. However, throughout participation, Emma did not feel vulnerable most of the time, continuously returned to baseline (i.e., not experienced it at all = 1), but rather experienced brief bursts. This was observed, for example, on Day 5, Instance 3, where her vulnerability went up to a 3.5, only to return to 1 by Instance 5. Further, on average, Emma was indeed on the lower end of inertia within her vulnerable states, compared to our other cases (). However, her grandiosity fluctuated regularly throughout the week. Apart from Day 1, it remained relatively high, showing variability but midrange instability, which further presented with great inertia within her grandiosity (). Interestingly, it seems that her momentary grandiosity and vulnerability were mutually exclusive where grandiose states related negatively to feeling resentful and underappreciated and vulnerable states negatively to all grandiose emotions ( and ), with one exception at the beginning of Day 5. She further showed a pattern in which positive affect positively related to grandiosity and negatively to vulnerability, and the reverse for negative affect. Moreover, her grandiose states coincided with feelings of dominance, affiliation, agency, and liking and being satisfied with an activity, whereas stressful events related to less grandiose endorsements. Emma’s vulnerability was accompanied by feelings of a threatened ego, low dominance, affiliation, communion, and dislike and dissatisfaction with an activity. Overall, these suggest that while she was feeling powerful and positive about herself, she experienced boosts in grandiosity, and while she was feeling dissatisfied and dissocial, she sustained vulnerability.

Table 3. Means and standard deviations of the momentary state items for each case.

Table 4. Pearson correlations between global grandiose states of the six cases and other momentary states.

Table 5. Pearson correlations between global vulnerable states of the six cases and other momentary states.

Arief

Arief was a 21-year-old Indonesian male. He completed an academic bachelor’s degree, was looking for employment, and single. He completed 87% of the EMA question rounds. He spent most of his time at home, with family, working or eating and drinking. Arief scored comparatively high on grandiose narcissistic traits, most notably on the leadership/authority subcomponent, and low on vulnerable narcissistic traits. According to his interpersonal circumplex he perceived himself as generally dominant, arrogant, and extraverted while warm and agreeable. He further showed rather high agency traits.

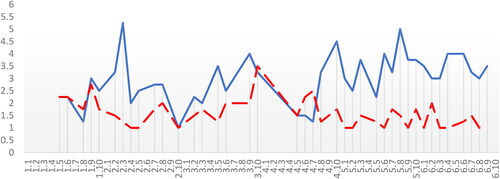

In daily life, Arief experienced rather high affiliation and communion. His affect seemed regular, with positive affect being in the midrange and negative affect being on the lower end. Arief’s vulnerability in daily life was relatively low, as was his grandiosity in comparison to his grandiose trait score and our other cases. At the item level, it stood out that he mainly felt powerful in his grandiosity and ignored in his vulnerability. The feeling of being ignored also had the most variability.

Arief’s narcissistic patterns in daily life show that, apart from Day 4, he experienced high instability and lower inertia in his grandiose feelings, meaning that his emotions spiked greatly and rapidly instead of building up over time ( and ). The spikes in grandiosity related to increased feelings of affiliation, communion, positive affect, and pleasantness of events; liking, satisfaction, and competency in his activities; reduced threatened ego; and high-arousal negative affect (). Simultaneously, Arief experienced less vulnerability than grandiosity. Regardless, although the instability and variability in vulnerability were rather low, there were some observable fluctuations. Interestingly, the fluctuations in vulnerability did not seem to link to any other emotion except the dislike of activities (). However, given that Arief spent most of his time with his family and endorsed feeling ignored the most, it seems that Arief experienced grandiosity when feeling positive about himself, others, and activities, and vulnerability when he was alone and disliked what he was doing.

Summary: Predominantly grandiose

Emma and Arief shared specific characteristics in traits and states. For one, on a trait level, they seem to have a similar self-image, scoring highest on the same octants of the interpersonal circumplex, agency, and communion. Second, in daily life, their state grandiosity was higher than their state vulnerability. Both experienced little vulnerability, which mainly remained at baseline; however, fluctuations still occurred. Per contra, their patterns of grandiose narcissistic fluctuations differed quite substantially. Whereas Emma experienced more stable and higher levels of grandiosity, Arief experienced more instability leading to seemingly random spikes in grandiosity. Further, some overlap became apparent, both Emma and Arief experienced higher grandiosity when their affect was positive, they liked and were satisfied with their activity, and they felt affiliation (i.e., warmth and agreeableness toward others).

Predominantly vulnerable

Anne

Anne was a 36-year-old Dutch female. She completed an applied bachelor’s degree, was employed, and was in a relationship. She completed 82% of the EMA question rounds. She spent most of her time at home or work, with her partner, working, eating and drinking, or socializing. Anne scored relatively high on vulnerable narcissistic traits, most notably on the oversensitivity to judgment subcomponent, and low on GN traits. Her interpersonal circumplex scores suggested that she perceived herself as generally submissive, unargumentative, warm-agreeable, and extraverted.

In daily life, Anne’s average grandiosity was in the mid- to high-range, falling above the mean of our overall sample (M = 2.52). She experienced seemingly low levels of vulnerability, but these levels were still higher than those of our predominantly grandiose cases. Out of the vulnerability items, she endorsed feeling underappreciated the most. Regarding the nonnarcissistic states, she gravitated toward feeling high dominance, affiliation, and communion on a day-to-day basis. Her affect was relatively regular, except for low-arousal positive affect, which, on average, was close to the highest possible score.

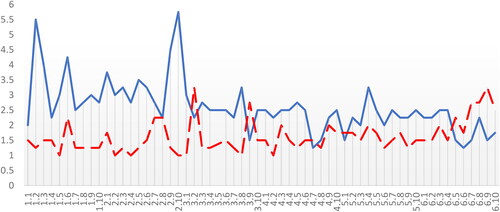

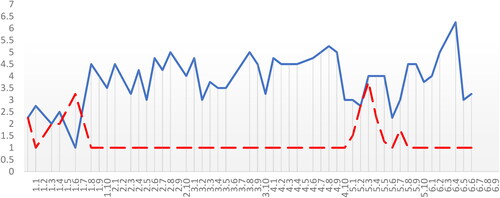

Throughout her participation, Anne experienced continuous fluctuations within her VN and GN states ( and ). Although generally her vulnerability and grandiosity were not related, underappreciated forms an exception, as it related negatively to her grandiose moments, as did low-arousal negative affect (). On average, her grandiosity showed relatively high inertia () and spiked (i.e., showed instability) when she liked, was satisfied, and felt confident regarding her activities. Curiously, her vulnerable states were not systematically related to any other emotional states.

Emily

Emily was a 22-year-old female from the United Kingdom. She completed high school, was a student, and was in a relationship. She completed 97% of the EMA question rounds. She spent most of her time at home, working or relaxing, and relatively evenly split her time between her partner and being alone. Emily scored comparatively high on VN traits, most notably on the oversensitivity to judgment subcomponent, and low on grandiose narcissistic traits. Her interpersonal circumplex scores suggested that she perceived herself as generally submissive, unargumentative, and warm-agreeable while also being extraverted. Additionally, she further described herself as aloof-introverted. Moreover, Emily scored relatively high on communion and unmitigated communion.

In daily life, Emily experienced average levels of grandiosity and vulnerability. Out of the vulnerability items, she endorsed feeling ignored the most. Moreover, she felt rather high levels of affiliation and communion. Her affect was fairly regular, though, with higher levels of low-arousal positive affect.

Moreover, Emily experienced continuous fluctuations within her vulnerable and grandiose narcissistic states ( and ). Her grandiosity was the highest on Days 1 and 2 and evened out during the consecutive days. Similarly, on average, she experienced relatively high inertia within her grandiosity. Her vulnerability experienced spikes during Days 3 and 4 and reached its peak toward the end of the last day. Emily’s grandiosity and vulnerability were mutually exclusive, with the exception that feeling resentful did not relate to her vulnerable states (). Further, her grandiose moments coincided with positive affect, feeling affiliation and communion, and experiencing pleasant events. High-arousal negative affect, a threatened ego, and stressful events related to less grandiose endorsements. On the other hand, high-arousal negative affect, stressful events, feeling agentic, and a lack of affiliation and communion positively related to her vulnerability.

Summary: Predominantly vulnerable

Both Anne and Emily experienced higher grandiosity than vulnerability in daily life. However, their vulnerability was still observably high and showed variability without going back to baseline for prolonged periods of time. Further, they experienced short time periods in which their vulnerability was greater than their grandiosity (e.g., Anne: Day 4, Instance 5–7; Emily: Day 6, Instance 5–10) and they consistently showed some level of vulnerability.

Combined subdimension

Julia

Julia was an 18-year-old German female. She completed high school, was a student, and was in a relationship. She completed 90% of the EMA question rounds. She spent most of her time at home, alone, working, or relaxing. Julia scored comparatively high on both GN and VN traits, most notably on the leadership/authority and oversensitivity to judgment subcomponents. Her interpersonal circumplex scores showed that she saw herself as generally dominant, arrogant, and extraverted while warm and agreeable. This was further reflected in her rather high agency and communion traits.

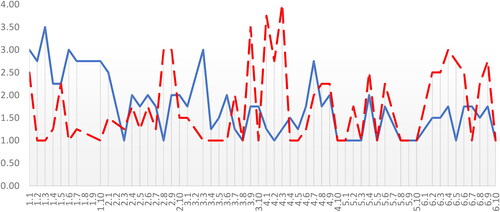

In daily life, Julia experienced average levels of vulnerability. She endorsed feeling ignored and underappreciated the most (), with underappreciated showing the largest variability. Although she still had average levels of grandiosity, gravitating toward feeling brilliant and powerful, her state grandiosity was the lowest out of our six cases. Moreover, she felt rather high levels of dominance, affiliation, and agency. Her affect was fairly average, though, with higher levels of low-arousal positive affect.

On a day-to-day basis, Julia experienced continuous fluctuations within her VN and GN states ( and ). Both narcissistic states showed movement and visible spikes. The VN states were, on average, especially unstable and characterized by inertia (). Depending on the day, she felt rather grandiose or vulnerable. For example, on Day 1, her grandiosity was higher than her vulnerability at all times. On the contrary, on Day 6, except for Instance 7, her vulnerability was prevalent. However, interestingly, for example, on Day 5, Julia’s vulnerability and grandiosity were in sync, following similar patterns. Julia’s narcissistic states did not coincide heavily with other emotions, apart from high- and low-arousal positive affect positively and high-arousal negative affect negatively relating to grandiose emotions, and increased agency and high-arousal negative affect relating to vulnerable emotions. Given that Julia did not have a large variety of company nor location in her activities, there were no means of detecting any within-situation influences on her momentary states.

Matis

Matis was a 19-year-old Lithuanian male. He completed high school, was employed, and was single. He completed 87% of the EMA question rounds. He spent most of his time at home, alone, while working. Matis scored high on both GN and VN traits, most notably on the self-absorption/self-admiration subcomponent. According to his interpersonal circumplex scores, he perceived himself to be both dominant and submissive, unargumentative, extraverted, and warm and agreeable. Again, this was reflected in his high agency and communion traits.

In daily life, Matis experienced high communion. His affect was approximately evened out between positive and negative, as well as high- and low-arousal affect. Matis’s grandiosity and vulnerability in daily life were both relatively average. At the item level, it stood out that he felt primarily brilliant and powerful in his grandiosity and misunderstood and underappreciated in his vulnerability.

Matis’s narcissistic patterns showed that he experienced variability in both his grandiose and vulnerable states. His vulnerability demonstrated large instability and inertia ( and ), except for Day 6. To some extent, his vulnerability related negatively to his grandiosity, at least to feeling brilliant and glorious. Experiencing a threatened ego, stressful and unpleasant events, and negative affect coincided with the vulnerability. The lack of feeling dominant, communal, positive affect, and like, satisfaction, and competency with his activity further accompanied his vulnerability. Matis’s grandiosity showed a different pattern, seemingly with more inertia and less instability. His grandiose states related negatively to vulnerability, except for feeling misunderstood. Feeling grandiose was associated with the absence of a threatened ego and negative affect, and the presence of affiliation, communion, positive affect and satisfaction, company, and liking of the current activity.

Summary: Combined subdimension

Overall, the combined grandiose and vulnerable cases showed yet another pattern of narcissistic experiences in daily life. Although the mean levels did not stand out, the observable fluctuations did. There was a larger variety of interactions between grandiose and vulnerable states, which, at times, moved in opposite directions but also cooccurred. The average vulnerable instability and inertia were especially noticeable and it was overall visible that vulnerability played a more significant role than in our other cases. Although unique contributors to feeling vulnerable were not immediately apparent, it seemed that overall, our combined cases were highly reactive and switched between experiencing increased grandiosity and vulnerability multiple times a day.

Discussion

In addition to recent quantitative studies into daily life dynamics of narcissism, this article showcases individual differences regarding the experience of grandiose and vulnerable states in daily life. To this end, six cases were chosen based on their narcissistic trait scores; two for each subdimension of cases: predominantly grandiose, predominantly vulnerable, and combined subdimensions. Focusing on these individual cases led to conclusions regarding their overlap, as well as their heterogeneity.

Differences in narcissistic subdimensions

For all cases, grandiosity and vulnerability fluctuated throughout participation and can thus be viewed as evolving states complementing traditional traits. Although the ways in which the fluctuations occurred (i.e., variability, instability, and inertia) were largely individual, several patterns became visible. First, the predominantly grandiose subdimension (Emma and Arief) experienced grandiosity on a day-to-day basis, which, on average, remained relatively high. The vulnerability they experienced stayed relatively low but was triggered in individual moments. Further, it was unique for this subdimension that the vulnerability always returned to baseline; that is, it was not experienced at all for hours or even days at a time. Second, the predominantly vulnerable subdimension (Anne and Emily) demonstrated similar levels of grandiosity to the previous subdimension, but higher and more consistently present levels of vulnerability. Their vulnerability showed increased movement, and if it returned to baseline, it did not remain there for long (i.e., no more than two intervals, i.e., ∼1.5 hr). Finally, the combined subdimension (Julia and Matis) experienced the greatest interplay between and presence of both grandiosity and vulnerability. Further, they showed the most extensive variation and inertia and the largest instability in vulnerability. Both their grandiosity and vulnerability showed great fluctuations, seemingly portraying the most reactive of the subdimension cases.

Consequently, these observations add an intriguing insight regarding narcissistic subdimension patterns. Although clinically narcissistic presentations are primarily based on grandiose symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022), theory and research have acknowledged and established both grandiose and vulnerable presentations within the two-factor model (e.g., Miller et al., Citation2021). Research investigating this model quantitatively in daily life reported that predominantly grandiose individuals experience periods of both grandiosity and vulnerability, whereas predominantly vulnerable individuals experience mainly vulnerability (Edershile & Wright, Citation2021; Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023; Gore & Widiger, Citation2016). However, the cases in this study all experienced grandiosity and vulnerability, irrespective of the subdimension. Further, contrary to previous findings and thus highlighting the value of exploring single cases, our predominantly grandiose cases experienced mostly grandiosity and little vulnerability in daily life, and our predominantly vulnerable cases experienced greater grandiosity than vulnerability. Moreover, the previously unconsidered, combined cases experienced the most vulnerability. In previous group-level analyses, these combined cases would have contributed to GN and VN findings separately, as, on a trait level, they were assessed and analyzed independently from each other. Thus, it is conceivable that the deviating results stem from the current assessment and analysis of independence-based results. This suggests that, moving forward, one assessment including both GN and VN might be better suited to capture the fluidity of narcissistic dimensions. The current observations provide a unique contribution to the field and support narcissism as a complex system with time-variant dynamics, but they need to be replicated and investigated further. For example, previous research paired narcissism with personality impairment to shed light on the dimensions’ underlying mechanisms (e.g., Kampe et al., Citation2021; Pincus et al., Citation2016). As such, incorporating levels of personality functioning with an integrative GN and VN measure could provide a rich, individualized assessment that could clarify the mechanisms at play during the fluctuations.

Moreover, several within-situation variables coincided with narcissistic states in at least half of our cases, irrespective of the subdimension. As such, experiencing affiliation, communion, both high- and low-arousal positive affect, and liking, being satisfied with, and feeling competent about an activity accompanied grandiosity. Further, feelings of a threatened ego and both high- and low-arousal negative affect related to experiencing less grandiose states. Contrastingly, increased high-arousal negative affect, reduced affiliation, communion, and disliking an activity accompanied vulnerable states. The broad theme appears to be that grandiosity relates to positive emotions and ostensible prosociality, and vulnerability to negative emotions and disheartening sociality. Although these observations are correlational and do not imply causation, they do present exploration targets to further develop our understanding of narcissism’s complex mechanisms. Further, they support the inclusion of within-situation levels that have been proposed to interact with state, and subsequently trait, expressions of narcissism in recent conceptualizations (Ackerman et al., Citation2019).

Individuality within narcissistic subdimensions

We purposely did not only select one case per category to demonstrate that a one-size-fits-all approach, even within subdimensions, might overlook individual differences. Unique patterns became apparent within the case descriptions. For example, our predominantly grandiose cases both experienced fluctuations and high levels of grandiosity; however, Julia’s grandiosity remained elevated at all times, whereas Arief’s grandiosity was unstable and showed spikes that periodically returned to baseline. Alternately, within the combined subdimension, Julia’s grandiosity showed more large spikes than Matis’s. Further, contrary to our expectations based on, for example, the clinical dual-action model (Sachse, Citation2020), GN and VN states did not systematically inhibit each other, as, at times, Julia experienced roughly the same level of grandiosity and vulnerability. Nonetheless, Matis tended to have one state that was prevalent over the other. Moreover, including the correlation’s z scores enabled an overview beyond statistical correlations and placed the correlations into context. Although observing the cooccurrence of the different states via the correlations is valuable, the individual cases’ z scores based on the larger sample further demonstrated idiosyncrasies. Most of the significant correlations were mirrored by greater z scores; however, individual deviations emerged. For example, Anne’s grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic states did not significantly cooccur with high-arousal positive affect, nor were they mutually exclusive. However, her z score demonstrated that she did experience grandiosity and high-arousal positive affect at the same time substantially less than most of the larger sample and vulnerability and high-arousal positive affect simultaneously substantially more. All these varied idiosyncrasies would be neglected without individualized assessment and evaluation. Thus, customized care and research can aid treatment approaches and further our understanding of individual narcissistic experiences in natural environments by displaying changes in behavior and experiences within an individual that group-based observations could not illustrate (McDonald et al., Citation2017). Although narcissism’s conceptualization is still under investigation, these personalized observations indicate that although cross-sectional assessments possess their own value, they represent rather broad characteristics and only one side of the complex, idiographic, and dynamic processes involved in narcissism.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

To our knowledge, this was the first research to provide rich descriptions of cases that reported naturally occurring narcissistic experiences measured in real-time and real-life settings. The strengths of the utilized measurement include reduced assessment error and recall bias, enabled detection of sensitive changes (Verhagen et al., Citation2016), and valuable specificity that will benefit current narcissism conceptualizations and highlight the necessity of idiographic assessment and within-situation context. However, limitations remain. Although the current cases scored rather high on the narcissistic trait scales, they were not formally diagnosed and therefore were subclinical. Thus, replication in a clinical sample is needed. Further, future research should prolong the observation time to examine if the observed patterns are periodical; that is, if weeks or months differ from each other within an individual. Moreover, although the combination of the NPI and HSNS to assess trait narcissism is a well-founded approach, future research should replicate the results with different assessment scales that measure divergent aspects of narcissism as well as integrated, dimensional solutions. Varying narcissism assessments that measure different ranges of narcissistic aspects are invaluable (Rogoza et al., Citation2018), but combining them further with personality functioning assessments could be fruitful in disentangling underlying mechanisms that are shared between or are individual to each dimension. Finally, data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic provided a unique insight but might have also introduced some constraints. The resulting social isolation could have limited the participants’ exposure to external influences that might, in turn, have limited emotional reactivity and situational diversity. Considering that especially VN states were defined by emotions that tend to require an external party (e.g., feeling ignored or misunderstood), these might have been underrepresented.

Summary

The presented cases indicate that there could be broad patterns in how predominantly grandiose, predominantly vulnerable, and combined narcissistic cases encounter their narcissistic states. The predominantly grandiose cases experienced daily grandiosity with little to no vulnerability. The predominantly vulnerable cases experienced both grandiosity and vulnerability daily, as did the combined cases, but they further demonstrated the largest variation and presence of vulnerability. However, personal differences were still observed, which underlines the importance of idiosyncrasy to detect an individual’s true colors.

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the Ethics Review Committee Psychology and Neuroscience at Maastricht University (227_104-09-2020).

Open Scholarship

![]()

![]()

![]()

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XC4E2, https://osf.io/978qj and https://osf.io/4gk6e?view_only=f998f41c4e6e4c5fb64b5d1732ba8b19.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Notes

1 The larger project (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9YFXS) and the current manuscript (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XC4E2) were preregistered.

2 All data sets and syntax and scripts are available at https://osf.io/8vrn3/files/osfstorage.

3 Compared to our overall sample (grandiose M = 3.76, vulnerable M = 3.71; Freund, Eisele, et al., Citation2023) and other research with similar sample characteristics (e.g., grandiose M = 2.87, vulnerable M = 3.06; Hart et al., Citation2020).

References

- Ackerman, R. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Wright, A. G. (2019). Current conceptualizations of narcissism. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000463

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2023). Lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using ‘eigen’ and S4. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html

- Behary, W. T., & Dieckmann, E. (2011). Schema therapy for narcissism: The art of empathic confrontation, limit-setting, and leverage. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 445–456). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118093108.ch40

- Brown, R. P., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2004). Narcissism and the non-equivalence of self-esteem measures: A matter of dominance? Journal of Research in Personality, 38(6), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.11.002

- Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006

- Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Schurer, S. (2012). The stability of big-five personality traits. Economics Letters, 115(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.015

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 337, a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Crowe, M. L., Edershile, E. A., Wright, A. G., Campbell, W. K., Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Development and validation of the Narcissistic Vulnerability Scale: An adjective rating scale. Psychological Assessment, 30(7), 978–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000578

- Crowe, M. L., Lynam, D. R., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2019). Exploring the structure of narcissism: Toward an integrated solution. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1151–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12464

- Day, N. J. S., Townsend, M. L., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2020). Living with pathological narcissism: A qualitative study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Regulation, 7(19), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00132-8

- Debast, I., van Alphen, S. P., Rossi, G., Tummers, J. H., Bolwerk, N., Derksen, J. J., & Rosowsky, E. (2014). Personality traits and personality disorders in late middle and old age: Do they remain stable? A literature review. Clinical Gerontologist, 37(3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2014.885917

- Del Rosario, P. M., & White, R. M. (2005). The narcissistic personality inventory: Test-retest stability and internal consistency. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.08.001

- Du, T. V., Thomas, K. M., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2022). Differentiations in interpersonal functioning across narcissism dimensions. Journal of Personality Disorders, 36(4), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2022.36.4.455

- Edershile, E. A., Woods, W. C., Sharpe, B. M., Crowe, M. L., Miller, J. D., & Wright, A. G. (2019). A day in the life of Narcissus: Measuring narcissistic grandiosity and vulnerability in daily life. Psychological Assessment, 31(7), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000717

- Edershile, E. A., & Wright, A. G. C. (2021). Fluctuations in grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic states: A momentary perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(5), 1386–1414. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000370

- Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.11

- Fleeson, W. (2001). Toward a structure-and process-integrated view of personality: Traits as density distributions of states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.1011

- Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Dornetti, L., Marcassoli, I., Maffei, C., & Cheek, J. (2009). Tracking the hypersensitive dimension in narcissism: Reliability and validity of the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale. Personality and Mental Health, 3(4), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.92

- Freund, V. L., Castro-Alvarez, S., Peeters, F., & Lobbestael, J. (2023). Crossing the line: Switches in Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissistic states. PsyArXiv. https://psyarxiv.com/qeh3n

- Freund, V. L., Eisele, G. V., Peeters, F., Lobbestael, J. (2023). Ripples in the water: Fluctuations of narcissistic states in daily life. PsyArXiv. https://psyarxiv.com/x3fqj/

- Gore, W. L., & Widiger, T. A. (2016). Fluctuation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Personality Disorders, 7(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000181

- Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. (2020). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 15(1), 150–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619873350

- Grijalva, E., & Zhang, L. (2016). Narcissism and self-insight: A review and meta-analysis of narcissists’ self-enhancement tendencies. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636

- Hart, W., Kinrade, C., & Breeden, C. J. (2020). Revisiting narcissism and contingent self-esteem: A test of the psychodynamic mask model. Personality and Individual Differences, 162, 110026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110026

- Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A re-examination of Murray’s Narcissism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204

- Hyatt, C. S., Sleep, C. E., Lynam, D. R., Widiger, T. A., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Ratings of affective and interpersonal tendencies differ for grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A replication and extension of Gore and Widiger (2016). Journal of Personality, 86(3), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12325

- Jauk, E., Ulbrich, L., Jorschick, P., Höfler, M., Kaufman, S. B., & Kanske, P. (2022). The nonlinear association between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: An individual data meta-analysis. Journal of Personality, 90(5), 703–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12692

- Kampe, L., Bohn, J., Remmers, C., & Hörz-Sagstetter, S. (2021). It’s not that great anymore: The central role of defense mechanisms in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 661948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.661948

- Kingsbury, C., & Bernard, P. (2023). Dynamic patterns of personality states, affects and goal pursuit before and during an exercise intervention: A series of N-of-1 trials combined with ecological momentary assessments. Health Psychology Bulletin, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zm39x

- Kwasnicka, D., Dombrowski, S. U., White, M., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2017). N-of-1 study of weight loss maintenance assessing predictors of physical activity, adherence to weight loss plan and weight change. Psychology & Health, 32(6), 686–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1293057

- Li, S. M., Tseng, L. C., Wu, C. S., & Chen, C. J. (2007). Development of the agency and communion scale. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 35(10), 1373–1378. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.10.1373

- McDonald, S., Quinn, F., Vieira, R., O'Brien, N., White, M., Johnston, D. W., & Sniehotta, F. F. (2017). The state of the art and future opportunities for using longitudinal n-of-1 methods in health behaviour research: a systematic literature overview. Health Psychology Review, 11(4), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2017.1316672

- Miller, J. D., Back, M. D., Lynam, D. R., & Wright, A. D. C. (2021). Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211044109

- Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x

- Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Vize, C., Crowe, M., Sleep, C., Maples-Keller, J. L., Few, L. R., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Vulnerable narcissism is (mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 86(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12303

- Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (1993). Narcissism and self-evaluation maintenance: Exploration in object relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(6), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167293196001

- Pincus, A. L., Cain, N. M., & Wright, A. G. C. (2014). Narcissistic gradiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in psychotherapy. Personality Disorders, 5(4), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000031

- Pincus, A. L., Dowgwillo, E. A., & Greenberg, L. S. (2016). Three cases of narcissistic personality disorder through the lens of the DSM-5 alternative model for personality disorders. Practice Innovations, 1(3), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000025

- Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

- Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

- Rogoza, R., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Campbel, W. K. (2018). Measurement of narcissism: From classical applications to modern approaches. Studia Psychologica, 18(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.21697/sp.2018.18.1.02

- Rosenthal, S. A., Hooley, J. M., Montoya, M., van der Linden, S. L., & Steshenko, Y. (2020). The narcissistic grandiosity scale: A measure to distinguish narcissistic grandiosity from high self-esteem. Assessment, 27(3), 487–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119858410

- Sachse, R. (2020). Personality disorders: A clarification-oriented psychotherapy treatment model. Hogrefe Publishing.

- Scholten, S., Lischetzke, T., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2022). Integrating theory-based and data-driven methods to case conceptualization: A functional analysis approach with ecological momentary assessment. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 32(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2021.1916639

- Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

- Stone, A. A., & Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16(3), 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/16.3.199

- Verhagen, S. J., Hasmi, L., Drukker, M., van Os, J., & Delespaul, P. A. (2016). Use of the experience sampling method in the context of clinical trials. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 19(3), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2016-102418

- Verhagen, S., van Os, J., & Delespaul, P. (2022). Ecological momentary assessment and other digital technologies for capturing daily life in mental health. In D. Stein, N. Fineberg, & S. Chamberlain (Eds.), Mental health in a digital world (1st ed., pp. 81–108). Academic Press.

- Voigt, A. L. A., Kreiter, D. J., Jacobs, C. J., Revenich, E. G. M., Serafras, N., Wiersma, M., Os, J. v., Bak, M. L. F. J., & Drukker, M. (2018). Clinical network analysis in a bipolar patient using an experience sampling mobile health tool: An n = 1 study. Bipolar Disorder: Open Access, 04(01), 121. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1077.1000121

- Warner, M. B., Morey, L. C., Finch, J. F., Gunderson, J. G., Skodol, A. E., Sanislow, C. A., Shea, M. T., McGlashan, T. H., & Grilo, C. M. (2004). The longitudinal relationship of personality traits and disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.217

- Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K., & Vaughan, D. (2023). Dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html

- Wiggins, J. S., Trapnell, P., & Phillips, N. (1988). Psychometric and geometric characteristics of the Revised Interpersonal Adjective Scales (IAS-R). Multivariate Behavioral Research, 23(4), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2304_8