In volume 152, issue 3 (2018), the article “Moderating Effects of Prevention-Focus on the Paths from Two Insecure Attachment Dimensions to Depression” published in error. The entire article is reprinted here in this special issue using the same page numbers as the originally printed article. The original article can be found in volume 152, issue 3 at Taylor and Francis Online. Any citations of the article should be as follows:

Lee, D.-G., Park, J. J. Bae, B. H. and Lim, H.-W. Moderating Effects of Prevention-Focus on the Paths from Two Insecure Attachment Dimensions to Depression. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 152(3), 151–163.

Abstract

The present study investigated the moderating effects of prevention-focus on the paths from the dimensions of insecure attachment (attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety) to depression. Two hundred twenty eight Korean college students completed the Experience in Close Relationship – Revised Scale; the Regulatory Focus Strategies Scale; and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Results revealed a significant moderating effect for prevention-focus on the path from attachment avoidance to depression, but not on the path from attachment anxiety to depression. They further suggest that different interventions are needed for different combinations of persons' insecure attachment dimensions and levels of prevention-focus. Counseling implications and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders in South Korea, costing over 7 to 10 trillion Korean Won (63 to 85 billion US Dollars) per year over the five-year period from 2007 to 2011 (Lee, Baek, Yoon, & Kim, Citation2013). The number of patients diagnosed with depression has increased steadily, a 12% increase in 2015 from 2011. Moreover, the lifetime prevalence of depression diagnosis has increased progressively from 4.0% in 2001 through 5.6% in 2006, to 6.7% in 2011 (Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, Citation2015). This high rate is also cross-cultural; according to Blazer, Kessler, McGonagle, and Swartz (Citation1994), 17.1% of the US population (15–54 years of age) suffer from depressive disorder at one time or another during their lifetime. Depression is such a common illness that detailed investigation of its manifold causes or precedent variables is pivotal.

Depression is conceptualized as a product of the interaction between dysfunctional cognition and negative interpersonal relationship patterns (Safran, Citation1990). In this conceptualization, the roots of depression can often be found in insecure attachment with childhood caretakers (Whisman & McGarvey, Citation1995). In fact, several empirical studies on the relationship between attachment and depression in adults have suggested that insecure attachment is a significant precedent variable to predict depression (Besser & Priel, Citation2003; Gnilka, Ashby, & Noble, Citation2013; Jinyao et al., Citation2012; Pietromonaco & Barrett, Citation1997; Robert, Gotlib, & Kassel, Citation1996). In particular, a history of insecure attachment, along with self-criticism and dependence, is found to significantly predict depression (Besser & Priel, Citation2003). Compared to those who have secure attachment, individuals who have insecure attachment are more prone to depression (Myhr, Sookman, & Pinard, Citation2004; Reis & Grenyer, Citation2004; Robert et al., Citation1996).

According to Bowlby's (Citation1973) theory, infants develop an internal working model of attachment based on their relationships with their parents. This internal working model is a cognitive structure containing mental representations for understanding the world, self, and others. Bowlby argued that representations of early attachment patterns become internalized and form the basis for attachment patterns to others in adulthood. Bartholomew and Horowitz (Citation1991) went further to propose four attachment categories (secure, preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing) by splitting the representations of both self and others into positive or negative valence. However, no empirical study has so far determined the exact methods to differentiate the four categories. For this reason, Wei, Mallinckrodt, Russell, and Abraham (Citation2004) argued that attachment is better conceptualized using continuous dimensions, rather than discrete categories.

Insecure attachment fall into two dimensions – attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, Citation1998, Cameron, Finnegan, & Morry, Citation2012). Attachment avoidance is defined as the fear of interpersonal closeness or dependence on others. It can develop when caretakers do not respond to or ignore their children's emotional needs. Attachment anxiety taps the fear of being rejected or abandoned. It can develop when caretakers respond to their children's emotional needs in an inconsistent manner. Those who have insecure attachment are known to resort to two different behavioral strategies (Cassidy, Citation2000; Ponizovsky & Drannikov, Citation2013). A deactivating strategy, in which behavior or thought is used to maximize their distance from others and suppress their negative feelings in order to avoid frustration caused by others, is associated with attachment avoidance. In contrast, a hyper-activating strategy, in which behavior or thought is used to maximize their proximity to others and exaggerate their emotional distress in order to elicit others' compassion, reflects attachment anxiety. Wei, Vogel, Ku, and Zakalik (Citation2005) showed that those with high levels of attachment anxiety use emotional reactivity (i.e., a hyper-activating strategy), leading to psychological maladjustment, such as depression, while those who have high levels of attachment avoidance rely on emotional cutoff (i.e., a deactivating strategy), which also results in increased risks of depression.

What remains unexplained in the literature is the inconsistent relationship between attachment avoidance and depression. Some studies found a significant relationship (e.g., Wei, Mallinckrodt, Larson, & Zakalik, Citation2005) but other studies found no relationship (e.g., Wei, Heppner, Russell, & Young, Citation2006; Wei, Russell, & Zakalik, Citation2005), despite the consistent findings about the significant positive association between attachment anxiety and depression (e.g., Simpson & Rholes, Citation2004; Wei, Mallinckrodt et al., Citation2005; Wei, Russell et al., Citation2005). The inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between attachment avoidance and depression indicate that there are different mechanisms involved in the transitions from the two insecure attachment dimensions to depression, and specifically that there exists another variable significantly moderating the path from attachment avoidance to depression.

Our speculation is further supported by a previous study (Wei, Mallinckrodt, Russell, & Abraham, Citation2004) which examined possible moderating effects of some selected psychological attributes (e.g., maladaptive perfectionism, couple adaptation, etc.) on the links between the two insecure attachment dimensions and depression. Wei et al. (Citation2004) found that maladaptive perfectionism significantly moderates the link from attachment anxiety to depression but not the link from attachment avoidance to depression. The results could be interpreted to suggest that that attachment anxiety, characterized by hyper-activating strategies (e.g., hypervigilance to signs of others' rejection), become more strongly associated with depression when accompanied by excessive worry about others' negative evaluation (i.e., maladaptive perfectionism); in contrast, attachment avoidance, characterized by deactivating strategies (e.g., emotional suppression and defensive distancing), blockades the effect of excessive worry about others' evaluation on the relationship between attachment avoidance and depression. Then the question to be asked is whether there exist other variables that are more sensitive to deactivating strategies which influence the transition from attachment avoidance to depression.

In pursuit of this question, the present study investigated whether “prevention-focus,” one of Higgins's (Citation1997) self-regulatory strategies, acts as a moderator of the attachment avoidance–depression relationship. Prevention-focus encompasses the motivation to obtain security, avoid undesired end states, and satisfy one's ought self (Haws, Dholakia, & Bearden, Citation2010; Higgins, Citation1997; Klenk, Strauman, & Higgins, Citation2011). In contrast to promotion-focus which involves advancing success and seeking to attain positive outcomes, prevention-focus reflects behavioral avoidance of threat or failure (Higgins, Citation1997; Ståhl, van Laar, & Ellemers, Citation2012). From a motivational perspective, individuals high on prevention-focus scales exhibit a stronger tendency to avoid taking risks to achieve desired outcomes than their counterparts' low said scales (Bryant & Dunford, Citation2008).

Prevention-focus as a basic motivational principle resembles behavioral manifestations of deactivating strategies to cope with attachment challenges. Given that prevention-focus is positively correlated with perceived stress (Schokker, Links, Luttik, & Hagedoorn, Citation2010), it could be presumed to be correlated with depression. This may provide a clue to the inconsistent findings regarding the correlations between attachment avoidance and depression found in the literature (e.g., Wei et al., Citation2006; Wei, Mallinckrodt et al., Citation2005). It is reasonably inferred that individuals high on prevention-focus would avoid situations likely to include conflict and experience more difficulty in coping with their interpersonal problems. In contrast, those low on prevention-focus are less likely to evade a high-conflict situation and have better chances to resolve their interpersonally problematic situations.

On the other hand, prevention-focus is not likely to act as a moderator of the attachment anxiety–depression relationship as the magnitude of correlation between attachment anxiety and depression is relatively large (e.g., r = .49 in Wei et al., Citation2004). Furthermore, attachment anxiety and a hyper-activating strategy are conceptually unrelated to prevention-focus in that they accompany strong emotional responses than the emotional cut-off and deactivating strategies.

The present study empirically examines the differential moderating effects of prevention-focus on the links between two insecure attachment dimensions (i.e., attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety) and depression in Korean college students. In this study, we aim to contribute to the expanded understanding of the paths from insecure attachment (source variable) to depression (symptom variable) by revealing different mechanisms involved in the two separate insecure attachment dimensions. In addition, we intend to empirically validate the moderating effect of prevention-focus on the attachment avoidance-depression relationship, which provide an explanation for the inconsistent findings regarding attachment avoidance and depression in the previous studies (e.g., Wei et al., Citation2006; Wei, Mallinckrodt et al., Citation2005). This study proposes two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Prevention-focus acts as a significant moderator of the attachment avoidance–depression relationship.

Hypothesis 2: Prevention-focus does not act as a significant moderator of the attachment anxiety–depression relationship.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 228 college students (89 men and 139 women) who enrolled in a psychology course at a private university in Seoul, South Korea. They were comprised of 86 freshman (37.7%), 31 sophomore (13.6%), 54 junior (23.7%), and 58 senior students (25.0%). The average age was 22.27 years (SD = 2.06). For this research, IRB review and approval were obtained. We solicited student participation via email, and those who consented to participation completed our online survey using Qualtrics.

Measures

Insecure Attachment Measure

To measure participants' levels of insecure attachment, the Korean version of the Experiences in Close Relationship-Revised (ECR-R) Scale was used. The ECR-R developed by Brennan et al. (Citation1998) was translated and validated in Korean by Kim (Citation2004). The Korean version of the ECR-R consists of two domains including attachment anxiety (18 items, e.g., “I'm afraid that I will lose my partner's love.” “I often worry that my partner will not want to stay with me.”), attachment avoidance (18 items. e.g., “I prefer not to be too close to romantic partners.” “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close.”). The scale includes 10 reverse-coded items and utilizes a Likert format, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate more severe insecure attachment. In Kim (Citation2004), the internal consistencies calculated using Cronbach's alpha statistic (alpha coefficient, hereafter) were .89 for attachment anxiety and .85 for attachment avoidance. In this study, the alpha coefficients for attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were .77 and .91, respectively.

Prevention-Focus Measure

To measure participants' levels of prevention-focus, the Korean version of the Regulatory Focus Strategies Scale (RFSS) was used. The RFSS developed by Ouschan, Boldero, Kashima, Wakimoto, and Kashima (Citation2007) was translated and validated in Korean by Chun and Lee (Citation2008). The Korean version of the RFSS consists of two domains including promotion focus (8 items) and prevention-focus (8 items. e.g., “To achieve something, it is most important to know all the potential obstacles.” “To achieve something, one must be cautious.” “To avoid failure, it is important to keep in mind all the potential obstacles that might get in your way.”). For the purpose of the study, only the prevention-focus subscale was used. The scale is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) with higher scores indicating higher inclination to use prevention-focus. Chun and Lee (Citation2008) reported the alpha coefficient for prevention-focus to be .79. In this study, the alpha coefficient was calculated as .75.

Depression Measure

To measure participants' levels of depression, we used the Korean version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D developed by Radloff (Citation1977) was translated and validated in Korean by Chon, Choi, and Yang (Citation2001). The scale includes 20 items with a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most or all of the time) with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptoms (e.g., “I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me.” “I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor.”). Chon et al. (Citation2001) reported the alpha coefficient for the CES-D to be .91. In this study, the alpha coefficient was .91.

Data Analysis

To test the moderating effect of prevention-focus on the link between insecure attachment and depression, we used structural equation modeling (SEM), with maximum likelihood estimation, using AMOS 21.0. The use of SEM for examining moderation gives better results than the use of regression analysis. SEM improves the statistical power to detect moderation, by controlling for measurement errors occurring from the low reliability of the interaction term. It further provides a set of overall model-fit indices to determine the adequacy of model fit to the data (Busemeyer & Jones, Citation1983). In this study, an unconstrained approach was used to estimate the latent interaction among the four factors because the unconstrained approach with imposing no constraints can give an estimate almost identical to that obtained with a fully constrained approach (Marsh, Wen, & Hau, Citation2004). As the factors (i.e., attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, prevention-focus, and depression) are unidimensional, item parceling was employed to obtain more precise structural estimates and better model fit. Specifically, we used a domain representative parceling technique (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, Citation2002) and matched-pair strategy (Jackman, Leite, & Cochrane, Citation2011) to aggregate item parcels to use as indicators. Mean centering was applied for the indicators of the latent variables to be used for moderator model tests.

Using techniques from Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988), we examined the fit of the measurement model to the data. Then we tested structural models of interaction among the four measurement factors. Model fit indices used for determining the best fitting model included the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The following cut-off values for goodness-of-fit were used: for CFI and TLI .90 or above as an indicator of good fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999); for RMSEA .05 or below good fit and .06–.08 reasonable fit, and below .10 mediocre fit (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1992); and .06 or below for SRMR good fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

Lastly, we inspected how the moderating effect of prevention-focus on the insecure attachment–depression relationship differs by the levels of prevention-focus (high versus low). Given that SEM using AMOS 21.0 does not allow for testing a conditional effect by the levels of a moderator in the relationship between a predictor and a criterion variable (Hayes, Citation2013a), the process macro (model 1, Hayes, Citation2013b) in SPSS 21.0 was utilized.

Results

provides descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation coefficients for all study variables. Through the item parceling procedure, attachment anxiety had three indicators (anxiety 1, 2, 3); attachment avoidance three indicators (avoidance 1, 2, 3); prevention-focus three indicators (prevention 1, 2, 3); and depression four indicators (depression 1, 2, 3, 4). The indicators all met the normality assumption since no indicator presented skewness and kurtosis value greater than the absolute value of 2 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). The results from the correlation analyses revealed non-significant or weak correlations between the prevention-focus and depression indicators, but significant positive correlations among the remaining indicators.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlation Matrix for the Indicators (N = 228).

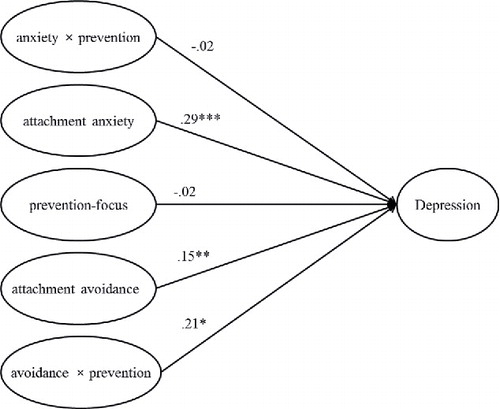

The results from a confirmatory factor analysis showed that the measurement model was well fitted to the current data [χ2 (59, N = 228) = 157.94, CFI = .96, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .09, & SRMR = .05]. The factor loadings of the indicators ranged from .70 to .92, all above .50, indicating that the indicators adequately represented the latent constructs (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010). Subsequently, testing structural models with the moderation effect of prevention-focus on the relationships among attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and depression were performed. The structural model and the path coefficients for the predictor variables are provided by and .

Figure 1. Path Coefficients for the Moderation Effect of Prevention-Focus on the Relationships Between Insecure Attachment and Depression. Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients were used for the path coefficients. Covariance estimates for extraneous variables were not provided for the presentation purpose.

Table 2. Path Coefficients for the Moderation Effect of Prevention-Focus on Depression.

The results indicated that the moderation model with prevention-focus as a moderator fit the data [χ2 (137, N = 228) = 299.32, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, RMSEA = .07, & SRMR = .05]. In , the path from the interaction term of avoidance and prevention to depression was significant (b = .21, p < .05), which then supports our Hypothesis 1. On the other hand, the path from the interaction term of anxiety and prevention to depression was not significant (b = −.02, ns), which then affirms our Hypothesis 2. In addition, the main effect of attachment anxiety on depression was significant (b = .29, p < .001), indicating that higher degrees of attachment anxiety lead to higher levels of depression. However, the non-significant main effect of prevention focus on depression (b = −.02, ns) indicated no direct relationship between those two factors. The estimates for the effect size of moderation of prevention-focus on the relationship between attachment avoidance and depression (Aiken & West, Citation1991) was .04, which is a small effect (Cohen, Citation1992). Given that according to Aguinis, Beaty, Boik, and Pierce (Citation2005), the average effect size in social science research is .01, the effect size of moderation for prevention-focus in this study is considered to be interpretable.

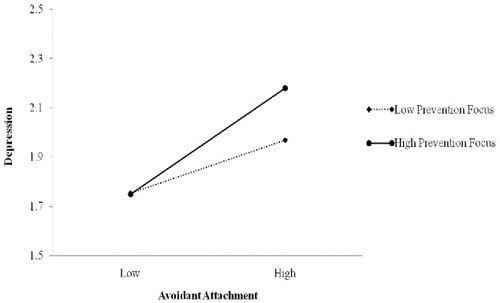

A simple slope test was performed to examine the effect of attachment avoidance on depression at 1 standard deviation (SD) above and below the mean value of prevention-focus (Aiken & West, Citation1991). Hayes's (Citation2013b) process macro (model 1) was used to calculate the values used for the plotting. graphically represents the interaction pattern of prevention-focus on the link from attachment avoidance to depression.

Figure 2. The Moderating Effect of Prevention-Focus on the Relation Between Avoidant Attachment and Depression.

The results demonstrated the robust significant positive effects of attachment avoidance on depression at 1 SD above (b = .12, p < .05) and also at 1 SD below (b = .24, p < .001). Moreover, increased prevention-focus (at 1 SD above) has a greater effect on the link from attachment avoidance to depression than does reduced prevention-focus (at 1 SD below). This indicates that prevention-focus has exacerbating effects on depression induced from attachment avoidance.

Discussion

The existing literature on attachment has suggested that insecure attachment is related to a range of social and psychological problems including depression (Lopez & Brennan, Citation2000; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2003). The present study advances the literature by examining differential moderating effects of prevention-focus on the paths from insecure attachment's dimensions (attachment avoidance versus attachment anxiety) to depression in particular. The results affirm that prevention-focus acts as a significant moderator for the path from attachment avoidance to depression but not for the path from attachment anxiety to depression. In other words, our results from Korean students indicate that high levels of prevention-focus will intensify the propensity of persons with avoidant attachment to be depressed; avoidant attachment behaviors (emotional suppression and defensive distancing) interact with prevention-focus strategies (avoidance of risk-taking), which could exacerbates their maladaptive interpersonal coping and results in greater propensity toward depression. By contrast, levels of prevention-focus exert no influence on the propensity of persons with the anxious attachment to be depressed.

Our results resonate with the previous findings on attachment and self-regulation (Semin et al., Citation2005; Wei, Russell et al., Citation2005). Individuals with high attachment avoidance generally have low trust in others and are less likely to expect emotional support from others (Cann, Norman, Welbourne, & Calhoun, Citation2008). They tend to be resistant to self-disclosure and interpersonal dependency (DeVito, Citation2014) and easily motivated to use a deactivating strategy (defensive distancing and emotional cut-off) in pursuing their senses of reassurance (Bryant & Dunford, Citation2008). Moreover, prevention-focused individuals are inclined to perceive their goals as duties and obligations, and thus experience higher levels of worry and anxiety, than their promotion-focused counterparts (Semin et al., Citation2005). They act to ensure the absence of negative outcomes that mismatch to desired end-states (Higgins, Roney, Crowe, & Hymes, Citation1994). Therefore, when individuals with high levels of attachment avoidance have high propensity to use a prevention-focus in coping with their interpersonal conflicts, they are very likely to deny the existence of the problem itself or withdraw from situations they may have to encounter interpersonal problems. This may temporarily fulfill their wish to be self-reliant but increases the possibility of harming relationships, leading to depression in the long run. In addition, our finding of no significant moderating effect of prevention-focus on the path from attachment anxiety to depression seems to support the previous studies where individuals suffering from anxious attachment show excessive fear or anxiety concerning separation from an attachment figure (Park & Lee, Citation2008; Wallin, Citation2007). They may use a prevention-focus to gain some reassurance; however, their emotional gains would not affect the progression of attachment anxiety to depressive symptoms.

Overall, the findings of the current study provide useful information for practitioners who work with people who have insecure attachment and depressive symptoms. Counselors may need to examine their clients' levels of prevention-focus, and by alleviating the clients' prevention-focus orientation, help them better cope with loss and fear likely to experience in conflict situations. Thus the intervention for attachment avoidant individuals' depression should include strategies to encourage them to exercise a promotion-focus in their pursuit of interpersonal goals, as alternate strategies to the employment of emotional cut-off and defensive distancing to gain temporal reassurance. On the other hand, when counseling with clients with high levels of attachment anxiety, counselors should be reminded that alleviation of prevention-focus would not be an effective intervention for attachment anxious individuals' depression.

The present study has several limitations. First, regulatory focus theory posits two independent orientations: prevention-focus and promotion-focus. The present study addressed the function of prevention-focus in the transition from insecure attachment to depression only, not that of promotion-focus. We could not include the function of promotion-focus in the analysis, as the data for doing so was not available. Hypothetically, anxious attachment behaviors (hyper-activating strategies) may interact with promotion-focus strategies (advancing success and seeking to attain an attachment figure's approval), which could increase the quality and quantity of interpersonal interactions and consequently prevent depression. Second, in the present study, a cross-sectional research design was used. Thus the relationships reported in this study are correlational; the assessment of cause and effect relationships needs further investigation with a longitudinal research design. Third, the remaining logical possibility is that regulatory focus acts as a mediator, not a moderator, of the insecure attachment–depression relationship.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the present study has important methodological features that should be highlighted. This study is differentiated from the previous literature, which mostly addressed insecure attachment as a unified variable with few exceptions (e.g., Wei et al., Citation2006; Wei et al., Citation2004), in that it examined the subdomains of insecure attachment as two individual variables. Our approach is supported by Park and Lee (Citation2008) which claims that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance need to be examined separately – the former is associated with mental representations of self and the latter mental representations of others (i.e., positive or negative perceptions of others). In essence, our finding of a significant moderating effect of prevention-focus on the path from attachment anxiety to depression provides an explanation for the inconsistent relationship between attachment avoidance and depression in the literature (e.g., Wei et al., Citation2006; Wei et al., Citation2005; Wei, Russell et al., Citation2005).

References

- Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. (2005). Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 94–107. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.94

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2003). A multisource approach to self-critical vulnerability to depression: The moderating role of attachment. Journal of Personality, 71(4), 515–555. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.7104002

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

- Blazer, D. G., Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., & Swartz, M. S. (1994). The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(7), 979–986. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.7.979

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rhodes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Bryant, P., & Dunford, R. (2008). The influence of regulatory focus on risky decision‐making. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 335–359. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00319.x

- Busemeyer, J. R., & Jones, L. E. (1983). Analysis of multiplicative combination rules when the causal variables are measured with error. Psychological Bulletin, 93(3), 549–562. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.93.3.549

- Cameron, J. J., Finnegan, H., & Morry, M. M. (2012). Orthogonal dreams in an oblique world: A meta-analysis of the association between attachment anxiety and avoidance. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 472–476. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.001

- Cann, A., Norman, M. A., Welbourne, J. L., & Calhoun, L. G. (2008). Attachment styles, conflict styles and humour styles: Interrelationships and associations with relationship satisfaction. European Journal of Personality, 22, 131–146. doi:10.1002/per.666

- Cassidy, J. (2000). Adult romantic attachments: A development perspective on individual differences. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 111–131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.111

- Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Chon, K. K., Choi, S-J., & Yang, B-C. (2001). Integrated adaptation of CES-D in Korea. Korean Journal of Health Psychology, 6(1), 59–76.

- Chun, S., & Lee, K-H. (2008). The examination of path model among neuroticism, state anxiety, self-efficacy, and career exploration behavior: Based on the regulatory focus theory. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 22(4), 93–110.

- DeVito, C. C. (2014). The link between insecure attachment and depression: Two potential pathways. Unpublished master's thesis. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

- Gnilka, P. B., Ashby, J. S., & Noble, C. M. (2013). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism as mediators of adult attachment styles and depression, hopelessness, and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 78–86. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00074.x

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013a). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013b). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS (version 2.13) [Software]. Retrieved from http://www.processmacro.org/download.html

- Haws, K. L., Dholakia, U. M., & Bearden, W. O. (2010). An assessment of chronic regulatory focus measures. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 967–982. doi:10.1509/jmkr.47.5.967

- Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. (2015). Total medical care cost [Healthcare Big Data Hub]. Retrieved from http://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapJdgeChargeInfo.do.

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

- Higgins, E. T., & Roney, C. J. R., Crowe, E., & Hymes, C. (1994). Ideal versus ought predilections for approach and avoidance: Distinct self-regulatory systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(2), 276–286. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.276

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jackman, M. G., Leite, W. L., & Cochrane, D. J. (2011). Estimating latent variable interactions with the unconstrained approach: A comparison of methods to form product indicators for large, unequal numbers of items. Structural Equation Modeling, 18(2), 274–288. doi:10.1080/10705511.2011.557342

- Jinyao, Y., Xiongzhao, Z., Auerbach, R. P., Gardiner, C. K., Lin, C., Yuping, W., & Shuqiao, Y. (2012). Insecure attachment as a predictor of depressive and anxious symptomology. Depression and Anxiety, 29(9), 789–796. doi:10.1002/da.21953

- Kim, S-H. (2004). Adaptation of the experiences in close relationships-revised scale in to Korean: Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory approaches. Unpublished master's thesis. Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- Klenk, M. M., Strauman, T. J., & Higgins, E. T. (2011). Regulatory focus and anxiety: A self-regulatory model of GAD-depression comorbidity. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 935–943. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.003

- Lee, S., Baek, J., Yoon, Y., & Kim, J. (2013). A study on the socioeconomic impact and management of mental health problems: Focusing on Depression. (NHIS Report No. 2013–02). Seoul, ROK: National Health Insurance Service. Retrieved from Research on National Health Insurance Service website: http://www.nhis.or.kr/bbs7/boards/B0069/6682?boardKey=39&sort=sequence&order=desc&rows=10&messageCategoryKey=&pageNumber=1&viewType=generic&targetType=12&targetKey=39&status=&period=&startdt=&enddt=&queryField=T&query=2013-02

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

- Lopez, F. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(3), 283–301. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.47.3.283

- Marsh, H. W., Wen, Z. & Hau, K. T. (2004). Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods, 9(3), 275–300. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2003). The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 35). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Myhr, G., Sookman, D., & Pinard, G. (2004). Attachment security and parental bonding in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison with depressed out-patients and healthy controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, 447–456. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00271.x

- Ouschan, L., Boldero, J. M., Kashima, Y., Wakimoto, R., & Kashima, E. S. (2007). Regulatory focus strategies scale: A measure of individual differences in the endorsement of regulatory strategies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10(4), 243–257. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00233.x

- Park, J-E., & Lee, E-H. (2008). Adolescents' insecure attachments and problem behaviors: The moderating role of empathic ability. The Korean Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 20(2), 369–389.

- Pietromonaco, P. R., & Barrett, L. F. (1997). Working models of attachment and daily social interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(6), 1409–1423. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1409

- Ponizovsky, A. M., & Drannikov, A. (2013). Contribution of attachment insecurity to health-related quality of life in depressed patients. World Journal of Psychiatry, 3(2), 41. doi:10.5498/wjp.v3.i2.41

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306

- Reis, S., & Grenyer, B. (2004). Fear of intimacy in women: Relationship between attachment styles and depressive symptoms. Psychopathology, 37, 299–303. doi:10.1159/000082268

- Robert, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 310–320. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.310

- Safran, J. D. (1990). Towards a refinement of cognitive therapy in light of interpersonal theory: I. Theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 10(1), 87–105. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(90)90108-M

- Schokker, M. C., Links, T. P., Luttik, M. L., & Hagedoorn, M. (2010). The association between regulatory focus and distress in patients with a chronic disease: The moderating role of partner support. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(1), 63–78. doi:10.1348/135910709X429091

- Semin, G. R., Higgins, T., de Montes, L. G., Estourget, Y., & Valencia, J. F. (2005). Linguistic signatures of regulatory focus: How abstraction fits promotion more than prevention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(1), 36–45. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.36

- Simpson, J. A., & Rholes, W. S. (2004). Anxious attachment and depressive symptoms: An interpersonal perspective. In W. S. Rholes & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Adult attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications (pp. 408–437). New York, NY: Guilford Press

- Ståhl, T., van Laar, C., & Ellemers, N. (2012). The role of prevention focus under stereotype threat: Initial cognitive mobilization is followed by depletion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1239. doi:10.1037/a0027678

- Tabachinick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Wei, M., Heppner, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Young, S. K. (2006). Maladaptive perfectionism and ineffective coping as mediators between attachment and subsequent depression: A prospective analyses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 67–79. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.67

- Wei, M., Mallinckrodt, B., Larson, L. A., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Attachment, depression, and validation from self and others. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 368–377. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.368

- Wei, M., Mallinckrodt, B., Russell, D. W., & Abraham, W. T. (2004). Maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator and moderator between adult attachment and depressive mood. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(2), 201–212. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.201

- Wei, M., Russell, D. W., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 602–614. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.602

- Wei, M., Vogel, D. L., Ku, T., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, affect regulation, psychological distress, and interpersonal problems: The mediating role of emotional reactivity and emotional cutoff. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 14–24. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.14

- Wen, Z., Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K. T. (2010). Structural equation models of latent interactions: An appropriate standardized solution and its scale-free properties. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/10705510903438872

- Whisman, M. A., & McGarvey, A. L. (1995). Attachment, depressotypic cognitions, and dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(6), 633–650. doi:10.1007/BF02227858