Abstract

Many employees worldwide combine a job with serious, goal-oriented ambitions in the athletic domain. However, scientific knowledge about day-to-day linkages between work and sports is lacking. We filled this gap in the literature by examining how experiences at work can enrich sports after work. Extending the work-home resources model to the work-sports interface, we posited that proactive work behaviors positively relate to work engagement – a state that may permeate into the sports domain and relate to positive sports outcomes. We conducted a diary study among 170 working recreational runners (598 measurement occasions). Within a three-week period, participants completed two surveys on days they worked and ran after work. Survey 1, completed at the end of the workday, covering proactive work behavior and work engagement, and survey 2, completed after running and covering running performance. The results of multilevel structural equation modeling indicated that on days employees showed more proactive behavior, they also reported higher work engagement. In turn, on days they reported higher work engagement, they recorded a steadier running pace. We discuss how these findings support the phenomenon of work-to-sports spillover and contribute to the current understanding of the interplay between work and sports.

Work and sports and physical exercise are central life domains for many people across the globe. Does active involvement in one domain relate to experiences in the other domain? Role enrichment theory proposes that experiences in one role may improve the quality of life in another role (Greenhaus & Powell, Citation2006). However, to the best of our knowledge, research on the positive spillover of experiences from work to sports and physical exercise is lacking. Do positive work experiences spill over to sports and physical exercise experiencesFootnote1?

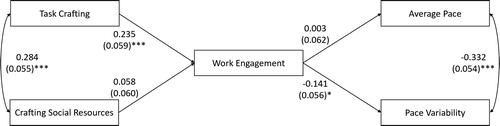

In our study, we fill this gap and investigate the short-term effects of combining work and sports, studying whether and how positive work experiences can enhance running experiences. To this end, we draw on the work-home resources (W-HR) model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012), which depicts antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of work-home enrichment. Applying the W-HR model to the work-sports interface, we aim to clarify the link between work activities, linking mechanisms, and sports outcomes. Specifically, we propose that the more employees proactively take control over the workday through job crafting (i.e. antecedent), the more engaged they will be at work (linking mechanism), and the better their running performance (i.e. outcome) will be (see ).

Figure 1. Structural model of within-person job crafting, work engagement, and running pace.

Note. Path coefficients are presented as standardized coefficients and standard errors in parentheses. The same paths are modeled at the between-person level. For ease of presentation, we exclude the control variables in this representation.

*p < .05, ***p < .001.

With this focus, we aim to make three contributions to the literature. First, we aim to generate new insights on work-to-sports spillover by extending the W-HR model to an entirely new context and translating the basic premises of this model to spillover among working athletes. Previous W-HR research has primarily focused on the work-family interface and has shown that work experiences may affect the family domain (e.g. Du et al., Citation2018). However, to our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated whether experiences or behaviors at work can serve to augment or enrich working athletes’ sports performance. Nevertheless, as many athletes hold a job alongside their goal-oriented sports activities, it is highly relevant to gain insight into the intricacies of this combination and uncover strategies they can apply on a daily basis to make their jobs into an asset for their athletic ambitions. To assess the occurrence and mechanisms of work-to-sports spillover, we use the heuristics of the W-HR model to illuminate the specific work-to-sports spillover processes that have yet to be examined. Specifically, we propose work engagement (i.e. vigor, dedication, and absorption; Schaufeli et al., Citation2002) as the linking mechanism between job crafting (e.g. the adjustment of one’s work situation to create more comfortable working conditions) with running performance.

Second, previous spillover measures explicitly required employees to assess their enrichment experiences (e.g. “My involvement in my work makes me cheerful and this helps me be a better family member”; Kacmar et al., Citation2014). Such assessment is highly complex and cognitively taxing. It requires respondents to form a mental image of multiple states at once (i.e. work involvement, feelings of cheerfulness, and performance as a good family member) and evaluate the linkages between those states. We, therefore, employ separate measures of experiences and states involved in work-sports enrichment and determine their linkages based on statistical associations. This approach is less subject to recall bias and may offer stronger evidence for possible enrichment processes.

Third, following the W-HR model, we investigate short-term enrichment processes. Research in the sports domain is largely based on the interindividual perspective (Dunton, Citation2017), is focused on differences between persons, and does not consider within-person variation or dynamic patterns of change. We use a quantitative diary method aimed at capturing within-person fluctuations in behaviors and experiences over time (Ohly et al., Citation2010). This within-person approach is necessary to understand how work behavior is related to one’s energy level and how energy may in turn relate to running (performance) on a daily basis. The findings may provide new insights into the nature of the work-sports interface. It might give athletes (and coaches) a better understanding of how their work behavior might be linked to their training performance and how energy levels might differ from day to day. Thus, this study can contribute not only to a conceptual understanding of spillover mechanisms specific to the work-sports interface but also to theory and practice in the sphere of athletic training and coaching.

Theoretical Background

Research indicates that work affects the home domain, causing work-home conflict (Amstad et al., Citation2011) or enrichment (Lapierre et al., Citation2018). In the W-HR model, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (Citation2012) used a demands and resources perspective to detail the mechanisms that trigger these work-home processes. In the work domain, job demands are aspects that require sustained effort (e.g. high workload; Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Job resources refer to a heuristic concept that can comprise a wide variety of individual states, and they are aspects that help people grow and deal with job demands; they can be contextual and outside the self (e.g. social support) or personal and proximate to the self (e.g. positive affect; Hobfoll, Citation2002).

Within the work domain, ample research suggests that employees feel more energetic at work when sufficient resources are available to counterbalance demands (Nahrgang et al., Citation2011). From a cross-domain perspective, the same idea can be proposed. Regarding the work-home interface, when enough resources are available, an enriching work-home process may occur. Such enrichment might happen when contextual resources (e.g. feedback, opportunities for growth) in one domain facilitate outcomes and functioning in another domain through gains in personal resources (e.g. time, energy, positive emotions, knowledge and skills; Lapierre et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, a depleting work-home process may occur when job demands drain personal resources, limiting the potential for high performance in another domain (Amstad et al., Citation2011).

With the W-HR model, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (Citation2012) suggested that personal resources are the linking pins between domains. If personal resources are drained, a depleting spillover process may occur. Sonnentag and Jelden (Citation2009), for example, found that on days employees experienced more situational constraints at work (e.g. outdated material, error in technical equipment), they had less energy (i.e. vigor), which was related to spending less time on sports activities. Indicating an enrichment process, on the other hand, the accumulation of resources may prompt an enrichment process. Research among employees and their spouses, for example, showed that on days employees helped colleagues at work, they reported higher positive affect and provided more support to their spouses at home (Lin et al., Citation2017). Through affective continuity (cf. Song et al., Citation2008), positive affect that is generated at work is carried into the home domain and plays a central role in daily work-life spillover processes.

Because work engagement may vary from day to day, many work-life spillover studies are based on a diary approach. Such an approach employs a quantitative study design in which participants repeatedly complete a survey with a specified time lag between the survey administrations (e.g. daily, weekly). In such designs, the assumption is that the targeted experiences or behaviors fluctuate over time and that fluctuations in one experience coincide with fluctuations in another. This design allows researchers to establish associations between concepts based on periodic fluctuations within persons rather than based on more standard comparisons between persons (Ohly et al., Citation2010). The use of this method provides insight into short-term microlevel processes of daily experiences (Bakker, Citation2014) and reduces retrospective bias (Reis & Gable, Citation2000). Studying changes within individuals is particularly suitable for testing psychological processes (Hamaker, Citation2012); one might explain, for example, why a runner feels vigorous in today’s training but much less so in the next training. This approach is especially valuable given our focus on running performance. Differences in running performance between people are determined by many external factors (e.g. technique) and the amount of running across the lifespan (Young et al., 2008), making it hard to disentangle the effects of specific predictors. To control for such factors, we mainly focus on within-person fluctuations in work experiences and running outcomes.

Toward a Work-Sports Spillover Process: Work Engagement as a Linking Pin

Based on the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012), we argue that “personal resources developed in one domain subsequently facilitate performance in the other domain” (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012, p. 549). Within the broad concept of personal resources, we focus on work engagement. Work engagement reflects a positive and fulfilling state of mind (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002) that can be highly valuable in enhancing performance within the work domain and may facilitate cross-domain enrichment (Christian et al., Citation2011). Work engagement is characterized by highly activated positive affect (Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2011) and is defined in terms of vigor (i.e. high energy levels), dedication (i.e. enthusiasm about work), and absorption (i.e. concentration). We regard work engagement as a promising linking pin between the work and sports domains because it contains physical, psychological, and affective components, and it is a positive state of mind characterized by positive affect (Bakker & Oerlemans, Citation2011), high energy levels, enthusiasm, and concentration (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002).

Work engagement and the simultaneous experience of positive physical, psychological, and affective states may predispose individuals to experience more positive states after work. These individuals might then draw upon these positive states in the subsequent domain. Researchers have indeed demonstrated that the positive state of work engagement can persist after the workday and promote functioning in other domains, contributing to work-life enrichment (e.g. Kim & Beehr, Citation2020; Rastogi & Chaudhary, Citation2018; Straub et al., Citation2019). Work engagement has also been linked to more specific outcomes, such as employees’ willingness to invest in their relationships with their life partners in the home domain (Bakker et al., Citation2012) as well as life satisfaction and community involvement (Eldor et al., Citation2020). On a daily basis, work engagement has been shown to relate to sharing positive work experiences at home (Ilies et al., Citation2017) and better recovery during off-job time (McGrath et al., Citation2017).

We propose that this positive active state of work engagement may also spill over to the sports domain. When people feel more engaged at work, they simultaneously experience positive affective, energetic, and cognitive states, providing them with a range of positive elements that can help them in subsequent sports activities. Indeed, a study among runners indicated that positive elements (e.g. feeling positive, energetic) are ideal for running (Lane et al., Citation2016). Specific to the mechanism we study, on days they experience high work engagement, people may leave their work feeling positive and energized, which are states that previous research has linked to better performance in the sports and exercise domain (Beedie et al., Citation2000). We thus focus on daily work engagement as the linking pin that translates positive work experiences into positive running experiences.

Our focus in terms of running experiences is on running performance in terms of both average running pace and pace variability. Previous studies indicate that better runners show a higher average running pace and lower pace variability (e.g. Breen et al., Citation2018; Santos-Lozano et al., 2014). This suggests that a stable running pace with limited fluctuations (i.e. lower pace variability) is preferable. Better runners appear to be capable of controlling their pace, possibly due to better physical fitness (e.g. Santos-Lozano et al., 2014). However, other factors might also influence pacing (Nikolaidis & Knechtle, Citation2018). For example, research has linked cognitive fatigue to impaired running performance (MacMahon et al., Citation2014). On days when people are more engaged at work, they feel more positive and energized. Based on the W-HR model, we propose that people will be able to tap into this source of energy while running, which should enable them to run faster and regulate their pace more successfully.

Hypothesis 1. Daily work engagement is positively related to daily average running pace.

Hypothesis 2. Daily work engagement is negatively related to daily pace variability.

Proactive Work Behavior as a Catalyst of Work-Sports Spillover

Next, we focus on job crafting as a strategy that athletes can pursue at work to increase their work engagement and trigger the enrichment mechanism. Job crafting refers to proactively optimizing work tasks and relationships (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) or job demands and resources (Tims & Bakker, Citation2010) with the aim of increasing the fit between the job and one’s needs and abilities. Job crafting is relatively independent of management (Parker et al., Citation2010), is a self-initiated bottom-up process (Tims et al., Citation2012), and is prevalent in different types of industries and jobs (e.g. blue-collar jobs, Nielsen & Abildgaard, Citation2012); it is a powerful strategy to enhance all types of positive states (Teng et al., Citation2020), including work engagement (Rudolph et al., Citation2017). Moreover, job crafting relates to daily and weekly fluctuations in work engagement because the extent to which individuals engage in job crafting also fluctuates from day to day (e.g. Petrou et al., Citation2012) and week to week (e.g. Petrou et al., Citation2017). Job crafting can be directed at different aspects of the job. In our study, we focus on crafting work tasks (e.g. mentoring new staff members; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) and crafting the social work environment (e.g. asking colleagues for support; Tims et al., Citation2012), as these types of crafting seem most likely to fluctuate on a daily basis.

De Bloom et al. (Citation2020) proposed that crafting motives, efforts, and outcomes across domains are linked; positive (or negative) crafting experiences may spill over to other domains. De Bloom and colleagues (2020) gave the following example: if an employee crafts her work to feel more competent, she might feel more satisfied, which may enhance her mood and interaction with her partner at home. In line with this proposition, Rastogi and Chaudhary (Citation2018) conducted a survey study on job crafting and spillover and found that job crafting and work engagement related to self-reported work-family enrichment (e.g. being a better family member). Similarly, job crafting and work-family enrichment were found to be positively related for employees working in service-oriented jobs (Loi et al., Citation2020). Translating and extending these preliminary findings to employees’ fluctuating experiences in combining work and sports, we propose that on days when athletes perform more job crafting, they will be more engaged at work, which will benefit their running experience in the sports domain in terms of a faster and more stable running pace. We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3. Daily (a) task crafting and (b) crafting of social job resources have a positive indirect relationship with daily average running pace through daily work engagement.

Hypothesis 4. Daily (a) task crafting and (b) crafting of social job resources have a negative indirect relationship with daily pace variability through daily work engagement.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We recruited participants through several running associations and social media channels. People were eligible for the study if they (a) had a paid job for at least 32 h a week and (b) had practiced running for at least one year (to ensure they took running seriously). We raffled three running watches; there was no other compensation for participation. The organizations that distributed the survey and the company that offered the watches were not involved in the study.

The study consisted of three surveys: a general survey, a work survey, and a running survey. By clicking on the distributed link, participants (N = 802) were redirected to the general survey, including an informed consent form. After completing the general survey, the participants received an email linking to an empty schedule. We asked them to fill out their schedule for the next three weeks for days when they worked as well as trained. Based on this information, the principal researcher constructed a personalized survey schedule for each participant. We then sent the participants an invitation to complete the work and run surveys on the training days indicated on their personal schedules.

Of all eligible participants, 43.64% (n = 350) completed their personal schedules and continued in the study. We included only those runners (n = 241) who trained after work because we were interested in daily work-to-sports spillover. During their workdays, the participants received an email linking to the work survey. Next, after their training, they received a separate email linking to the running survey. To avoid bias, the surveys were valid for a limited amount of time: the work surveys had to be completed before training, and the running surveys had to be completed shortly after training.

As we were interested in daily fluctuations, we excluded all participants who completed only one day of surveys (n = 69; Nezlek, Citation2011). The final sample included all participants (n = 170, 86 females) who completed two or more days of surveys (Mage = 41.16, SD = 10.82), yielding 598 measurement points in total. Among all participants, 54.10% had a bachelor’s degree, and 27.10% a master’s degree. Moreover, 28.20% had a supervisory position. The reported work sectors included finance and business (16.50%); healthcare (15.30%); government (11.20%); industry (7.60%); retail and catering (7.10%); and other sectors such as education, construction, and agriculture. The respondents had, on average, nearly 8 years of running experience, trained 2.69 times a week (SD = 0.91), and covered 9.89 (SD = 4.14) kilometers per training. These numbers indicate that the respondents were committed runners.

Measures

Work-Related Survey

All work-related survey questions were tailored to refer specifically to that workday, were translated into Dutch if necessary and were completed at the end of the workday before training. Items were answered on a 7-point Likert scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree).

Job Crafting

We measured two aspects of job crafting: task crafting and crafting of social job resources. Task crafting refers to modifying task scope or content (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001). We based our measure on the 5-item task crafting subscale of the Job Crafting Questionnaire (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, Citation2013). An example item is “Today, I changed the scope or types of tasks that I complete at work” (α = .82). Crafting social job resources refers to increasing the amount of social job resources; it was measured with a 5-item subscale of the Job Crafting Scale (Tims et al., Citation2012). An example item is “Today, I asked my colleagues for advice” (α = .79).

Work Engagement

We measured work engagement with Breevaart et al. (Citation2012) daily version of the Dutch 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). The survey includes 3 items for each dimension of work engagement, for example, “When I got up this morning, I felt like going to work” (vigor); “Today, my job inspired me” (dedication); and “Today, I was immersed in my work” (absorption). In line with previous studies (e.g. Daniel & Sonnentag, Citation2014), we treated work engagement as one construct, represented by the average scale score based on all 9 items (α = .91).

Running-Related Survey

The running-related survey was answered after each training session.

Training Performance

The participants self-reported their average and maximum paces using their tracking device. We transformed all scores into meters per second. Average running pace referred to the overall mean pace of a single training session. Pace variability reflected the difference between the maximum pace reached during training and the average pace of that training. A lower score implies fewer fluctuations, and lower pace variability indicates better performance (e.g. Breen et al., Citation2018).

Control Variables

The type of training and injury may cause strong fluctuations in average running pace and pace variability within persons, which could confound our results. We therefore included them as control variables on the daily level. Type of training reflected whether participants had performed endurance training (n = 282), interval training (n = 189), or another type of training (n = 127). Injury referred to the extent to which participants had an injury that bothered them during their training, indicated on a 7-point Likert scale anchoring 1 (not painful at all) to 7 (very painful).

Analytical Strategy

Our two-level design involved repeated measures (n = 598) nested within individuals (n = 170), yielding multilevel data. This design allowed us to detect links between concepts within persons (Ohly et al., Citation2010). That is, this design allowed us to consider whether changes within people in job crafting were related to changes within people in work engagement and running pace. We therefore conducted multilevel structural equation modeling using the lavaan package (Rosseel, Citation2012) in R (R Core Team, 2017). Multilevel modeling is a regression technique developed for analyzing data with observations that are clustered within higher-level units (e.g. measurement occasions within individuals; Hox, 2010). We used the full information maximum likelihood estimator to deal with missing data (as suggested by Newman, Citation2014). Following the recommendation by Preacher et al. (Citation2010), we modeled paths at the within-person (Level 1) and between-person (Level 2) levels. We did not center our variables because variables that are measured at the within-person level are implicitly partitioned into within and between components (Preacher et al., Citation2010).

Our predictors were task crafting and social crafting, our intermediate variable was work engagement, and our outcomes were average running pace and pace variability. We controlled for injury in relation to average running pace and pace variability, and we controlled for type of training in relation to pace variability. We tested the effects at the within-person level and allowed the residuals of task crafting and crafting of social resources to correlate at the within-person and between-person levels. Our analyses focused on the within-person level processes across the different days, consistent with our hypotheses that focused exclusively on within-person fluctuations.

To evaluate the fit of our final model, we followed Hu’s and Bentler’s (1999) recommendations and evaluated the comparative fit index (CFI; ≥ 0.95), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; ≥ 0.95), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; ≤ 0.08), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; ≤ 0.06).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC1; Bryk & Raudenbush, Citation1992) ranged between 42% and 74%. These values indicate substantial within-person variance (between 26% and 58%) to explain (e.g. Du et al., Citation2018; Sonnentag et al., Citation2020). The value of 1 minus ICC1 indicates the within-person variance in the daily measured variables. The lower the ICC1 is, the higher the within-person variance. shows the aggregated means, standard deviations, and within-person correlations for the study variables.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables (n = 170 participants).

Hypothesis Testing

We tested our hypotheses in a model with similar paths at the within-person and between-person levels. This model showed good fit: χ2 = 33.37, p = .057; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04 (within). For an overview of the standardized path estimates, see .

We hypothesized a positive association between daily work engagement and daily average running pace (H1). In our model, with injury controlled, daily work engagement was not significantly related to average running pace (standardized CI = [-0.119; 0.124]). Therefore, we rejected Hypothesis 1. In Hypothesis 2, we expected a negative association between daily work engagement and daily pace variability after injury and training type were controlled. Supporting this hypothesis, the results suggested that on days when employees reported higher work engagement, their pace variability was lower (standardized CI = [-0.251; -0.032]), indicating more pace stability.

Next, in Hypothesis 3, we predicted a positive indirect relationship between daily job crafting and average running pace via daily work engagement. While daily task crafting (standardized CI = [-0.119; 0.350]) was positively related to daily work engagement, daily social crafting was not (standardized CI [-0.060; 0.177]). After injury was controlled, the indirect relationships between job crafting and average running pace through work engagement were nonsignificant: task crafting (H3a): β = 0.001, SE = 0.015, standardized CI = [-0.028; 0.029]; social crafting (H3b): β = 0.000, SE = 0.004, standardized CI = [-0.007; 0.007]. These results offer no support for the premise that work engagement mediates the relationship between job crafting and average running pace.

Finally, Hypothesis 4 proposed a positive indirect relationship between daily job crafting and daily pace variability via daily work engagement. With injury and training type controlled, the indirect relationship of task crafting with pace variability through work engagement was significant: β = −0.033, SE = 0.016, standardized CI = [-0.064; -0.002]. As such, consistent with Hypothesis 4a, on days when employees were more proactive at work, their work engagement was higher, which then related to a lower pace variability. The indirect relationship between social crafting and pace variability through work engagement was not significant: β = −0.008, SE = 0.009, standardized CI = [-0.026; 0.010]. These results offered no support for Hypothesis 4 b.

Discussion

We used a quantitative daily diary design to examine our hypothesis that individuals would feel more engaged at work on days they proactively optimized their job characteristics (i.e. job crafting), which, in turn, would relate to average running pace and pace variability. Overall, our findings supported the basic premises of the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012) in a work-sport context by showing that daily task crafting (but not social crafting) is negatively related to pace variability through daily work engagement. While the relationships seem to be relatively weak, the results are consistent and suggest that positive experiences from the work domain spill over to the running domain on a daily basis.

Theoretical Contributions

Whereas some researchers have regarded work as an undermining factor for sports activities (Sonnentag & Jelden, Citation2009) and other researchers have regarded sports activities as a facilitating factor for work (de Vries et al., Citation2017), research examining work as a facilitating factor for sports activities is – to the best of our knowledge – lacking. The present study fills this gap in the literature and makes several contributions. First, our findings extend the W-HR model by applying the basic propositions to the work-sports interface and showing that some work experiences spill over to the sports domain. Previous spillover research has primarily focused on the work-to-family interface (e.g. Ilies et al., Citation2017; McNall et al., Citation2011). The present study expands this research by showing that proactive behaviors at work in terms of task crafting are related to performance in the sports domain. It is important to examine the work-sports interface because many people across the globe are involved in both life domains, and both life domains have been shown to be important for well-being, such that work (e.g. McKee-Ryan et al., Citation2005) and exercise (Penedo & Dahn, Citation2005) provide many health benefits (e.g. reduced depression, higher life satisfaction). Applying the heuristics of the W-HR model to specific processes in the work-sports interface, our study suggests that the crafting of activities at work fosters daily work engagement, which is related to better performance in the sports domain. We contribute to the spillover literature by showing a significant albeit weak link of concrete behaviors and engagement at work with concrete experiences in the sports domain. This finding suggests that the positive psychological experience of work engagement spills over to running performance.

A second contribution of our study is that we addressed specific antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of the work-sports process. Previous research has primarily relied on explicit measures to assess spillover processes, asking participants to self-report spillover (e.g. Lapierre et al., Citation2018). This method requires participants to reflect on a complex process that occurs mostly on a subconscious level. We provided indications for spillover by separately assessing the trigger (i.e. job crafting), mechanism (i.e. work engagement), and outcome (i.e. positive reflection and running performance), defining spillover based on the statistical co-occurrence of these indicators (cf. Du et al., Citation2018). Although self-reported, this approach is less susceptible to biases and subjective interpretation because it does not require participants to judge their own enrichment experience.

Third, we captured the dynamic short-term process of work-sports spillover, showing that this spillover process happens from day to day. Prior research has shown that, generally, when individuals have more positive experiences in one domain (e.g. sports), they are more likely to also have positive experiences in another domain (e.g. work). In a cross-sectional study, for example, Luth et al. (Citation2017) found that when individuals, in general, experienced cycling to be positively integrated in their identity, they were more likely to be satisfied with their work. Our findings indicate that intraindividual changes in work engagement are related to intraindividual changes in pace variability. That is, on days when individuals experience more work engagement, they are more likely to run at a more stable pace. This study provides insight into the daily cycle of cross-domain behavior; we show that behavior in the work domain can spill over to the sports domain on a daily basis. This insight extends research on the relationship between behavior or habits in different domains more globally because we map the dynamic short-term process, which may have different implications for practice.

Additionally, Molan et al. (Citation2019) suggested that job crafting theory may be valuable for coaches, staff, and management in the athletic context, and we extended this suggestion using a cross-domain perspective. Sonnentag and Jelden (Citation2009) found that job stressors were related to having less energy after work, which was related to less time spent on sports activities. Furthermore, adults reported a lack of time and resources as a reason for sports activity being compromised (Hyde et al., Citation2013). What if work can generate resources and create energy that could be used (to be active) in the sports domain? Therefore, a strategy to boost job resources (e.g. job crafting), such as energy or vigor, to counterbalance work-related stressors or demands might be highly valuable for sports outcomes. We thus argue that job crafting could also be beneficial for working athletes because it might improve the work experience and, consequently, the sports experience. Our findings indicated that pace variability is lower on days when employees use more task crafting strategies, which boost their boost work engagement. In general, lower pace variability implies better performance (Breen et al., Citation2018). Therefore, even if one’s pace is relatively slow but more stable than on other days, we would argue that this reflects better performance, as we compared daily pace variability to individuals’ own stability levels.

Our expectations regarding crafting the social work environment (i.e. crafting social resources) were not met. Based on our study, it seems that crafting social resources is not significantly related to work engagement and that the input of crafting social resources is not powerful enough to permeate into the sports domain. To explain these unexpected findings, we draw on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). In a diary study by Bakker and Oerlemans (Citation2019), crafting social resources was positively related to momentary work engagement via the need for relatedness but not via the need for autonomy or competence. Furthermore, crafting structural resources was positively related to momentary work engagement via the needs for autonomy and competence but not via the need for relatedness. It is possible that the needs for autonomy and competence are more important for work engagement than the need for relatedness.

It should also be noted that high daily work engagement did not translate into a higher average daily running pace. A possible explanation for this nonsignificant finding is that improving the average pace requires specific training (e.g. Skovgaard et al., Citation2014). Research also shows that specific exercises in trained runners only lead to subtle changes in running pace (Tønnessen et al., Citation2015). These subtle changes are difficult to trace, especially given the limited number of observations per participant in the current study. Considering the effort required to improve running pace, the three-week duration of our study, and the small standard deviation of average pace, the nonsignificant results seem plausible. Furthermore, the ICC1 of the average running pace was .74, indicating that most of the variance in the average running pace can be explained by differences between people rather than within people.

Limitations and Future Research

As with all research, our findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, it is important to note that the effect sizes in our study are small. This could be expected, as De Bloom et al. (Citation2020) argue that relationships between concepts within the work domain are more proximal and therefore stronger than more distal relationships between concepts across domains. Indeed, the results of other spillover studies have shown standardized effect sizes of a comparable magnitude (e.g. Kim & Beehr, Citation2020; Siu et al., Citation2015; Siu et al., Citation2010). Rastogi and Chaudhary (Citation2018) examined the relationship between job crafting and work-family enrichment through work engagement in a cross-sectional design and found standardized effect sizes between .10 and .20, which were larger than the effect sizes for the indirect effects in our study. All these studies, however, measured work-family enrichment with self-reports of spillover and measured the constructs in general (e.g. “My job inspires me”), whereas we targeted specific daily experiences (e.g. “Today, my job inspired me”). Furthermore, as great effort is required to improve running pace (Tønnessen et al., Citation2015), we cannot expect daily behavior or experiences to induce large changes in running pace. An important remark, however, is that small effects may accumulate and eventually result in large effects (Abelson, Citation1985). If daily proactive behavior and positive experiences repeatedly relate to small incremental changes, there might be a larger cumulative effect in the longer term (e.g. gradual daily improvements in running performance). Nevertheless, it is still important to realize that the effect sizes are small and might have limited practical significance.

Second, all variables in our study were measured via self-reports, and our results might have been influenced by common method variance. However, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003), we temporally separated the work-related measures from the training-related measures. Furthermore, the running performance metrics were qualitatively different from the response scales used for the other self-reports. This created methodological separation between the variables of interest and decreased the risk of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). However, future studies may consider using other reports (e.g. coaches) to replicate the current findings.

The pace variability metrics in our study might have been suboptimal. In the current study, we used self-reported performance and the difference in average and maximum pace. In previous studies, however, authors used registered performance and the difference between runners’ actual 5-km split time and their mean 5-km time to calculate a pacing index (e.g. Breen et al., Citation2018). Unfortunately, we had no means of using tracking devices or tracking runners’ split times during their training. To identify pace variability in the best possible way, we included average pace and calculated the difference between maximum and average pace. Nevertheless, registered split times might have produced a more reliable measure of pace variability. Moreover, the participants in the discussed studies (i.e. Breen et al., Citation2018; Santos-Lozano et al., Citation2014) were marathon runners, who might differ from amateur runners in several aspects, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other groups of runners. Nevertheless, the performance of (elite) marathon runners can be considered a prime example of excellence, thus offering valuable insights into indicators of high performance. We, therefore, believe our pace variability metric is still a respectable indicator of running performance in amateur runners.

Furthermore, our definition of running performance based on running pace and pace variability does not allow inferences about the actual physical and psychological sensations athletes experienced while running. The regulation of running pace and the intensity of exercise are complex and coordinated by several neural processes in different regions of the brain (Abbiss et al., Citation2015). For future research, it could be interesting to examine other measures that have been used to analyze running performance, such as ratings of perceived exertion (i.e. sensations during exercise; Abbiss et al., Citation2015). Additionally, the use of more sophisticated wearable performance devices to monitor real-time physiological effects during the day could provide us with more insight into the spillover process (see Li et al., Citation2016 for a selection of devices). Other psychological aspects, such as athlete engagement, might further elucidate the work-to-sports spillover process.

We cannot be certain that the work-sports spillover process examined in this study was causal or that no other variables interacted with or influenced this process. For example, researchers have shown that sleep plays an essential role in sports performance (e.g. Fullagar et al., Citation2015) and work-family conflict (Litwiller et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, the results of a study among nursing home workers suggested that sleep might have a domino effect across domains: poor sleep quality was related to low work productivity, which was in turn related to more work-family conflict (Lawson & Lee, Citation2018). Unfortunately, we are unable to determine whether sleep quality could be an alternative explanation for our results. Another important variable that might influence the spillover process is positive affect; it is possible that people do more crafting, experience more work engagement and have better running performance simply because they just feel good on certain days. After all, positive affective states have been suggested to relate to the initiation and continuation of proactive behavior (Parker et al., Citation2010). Researchers, therefore, could consider investigating sleep quality and controlling for positive affect in future work-life spillover studies.

Future research could also examine additional predictors or mechanisms to enhance our understanding of spillover, as findings and conclusions will relate to the specific concepts that we studied here. It could be interesting to examine cognitive forms of job crafting in addition to task or social crafting. Employees might adjust how they think and feel about their work (i.e. cognitive crafting; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), which may enrich the sports domain such that a positive mood is maintained during sports. Previous research suggests that such a positive mental state can facilitate thriving in sports (Brown et al., Citation2018).

Last, whereas we focused on enrichment, the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012) also depicts how combining different roles can sometimes be distressing. Given that combining multiple roles can be straining (Amstad et al., Citation2011) and enriching (Lapierre et al., Citation2018), future studies could extend our work by adding unfavorable work-to-sports spillover effects to the equation. For example, building on the study by Sonnentag and Jelden (Citation2009), who found that job stressors were negatively related to time spent on sports activities, we could examine the role of job stressors in sports performance. Furthermore, stable individual traits (Hobfoll, Citation2002) may play an important role in shaping these contrasting spillover pathways (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012), and these traits have been suggested to explain why some people experience more conflict or enrichment than other people. For example, optimists might be less likely to experience work-sports conflict and more likely to experience work-sports enrichment.

Although we focused on amateur athletes with substantial day jobs, the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, Citation2012) may also be highly relevant to elite athletes. In that case, the focus on work could be replaced by a focus on leisure time activities and experiences and their potential spillover to the sports domain. For example, future research could consider the impact of leisure crafting on sports performance. Leisure crafting reflects “the proactive pursuit of leisure activities targeted at goal setting, human connection, learning and personal development” (Petrou & Bakker, Citation2016, p. 508). An elite soccer player could, for example, spend some of her free time helping children with special needs build confidence. This form of crafting might add fulfillment and meaning to this athlete’s life. This, in turn, could provide athletes with vitality and motivation that may contribute to better performance.

Practical Implications

Our findings have practical implications. As work can provide additional energy for sports, athletes could be educated about the possibility that their behavior at work could boost their experiences and outcomes in the sports domain. Managers and HR departments are advised to be aware of the merits of job crafting and give employees the opportunity to take control over their workdays (e.g. through flexible work schedules). Organizations may want to offer job crafting interventions. Such interventions have been shown to result in changes in job crafting behaviors and constructs, such as work engagement (e.g. Gordon et al., Citation2018) and positive affect (Van den Heuvel et al., Citation2015). Stimulating job crafting could be beneficial for employees, their work teams, and their managers, as well as for stakeholders in the employees’ athletic setting (e.g. sports teams, sponsors).

With regard to the athletic setting, coaches and associations could consider the integration of work and athletics (Pink et al., Citation2018) and encourage athletes’ development in different life domains. Coaches are advised to be aware that having a job alongside an athletic career can enrich the athletic experience rather than merely acting as a distracting factor. Therefore, coaches could explicitly pay attention to nonathletic occupational aspects of their athletes’ lives. They could include the athlete’s work context in their coaching realm and encourage athletes to optimize their (work)days and harmonize training obligations with their nonathletic demands, creating a strong foundation for bidirectional enrichment processes.

Because our study is the first to illuminate the domain of work-to-sports enrichment and because the effect sizes we found are small, some caution in the interpretation of our results and implications is necessary. Additional research is needed to examine the replicability, generalizability, and substantiality of our findings.

Conclusion

The findings of the present quantitative diary study support the work-to-sports spillover process, showing that behaviors and experiences at work, specifically task crafting and work engagement, are linked to experiences in the athletic domain. Our findings support the premise that employees are better able to regulate their running pace on days when they proactively change their tasks at work because they experience higher work engagement. By showing a positive spillover effect of work-to-sport, this study is the first to fill this gap in the literature and provide insights into how work life positively affects sports life. Adopting a within-person approach with separate measures of work aspects and sports aspects, we illuminate a unique, day-to-day work-sports spillover process. This paper thus provides empirical support, albeit somewhat preliminary given the small effect sizes, for a positive link between work and sports. Small daily changes might add up to larger changes in the longer term. Notwithstanding the study’s limitations, the current findings add to our understanding of the unique work-sports enrichment process and indicate that active involvement at work can be instrumental in enhancing athletes’ running experience.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anniek Postema

Anniek Postema is a PhD candidate at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Arnold B. Bakker

Arnold B. Bakker is a Professor and chair of the research group Work and Organizational Psychology of the Institute of Psychology at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Heleen van Mierlo

Heleen van Mierlo is an Assistant Professor in Work and Organizational Psychology at the Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Notes

1 We refer to physical activity that is planned, structured and repetitive (Caspersen et al., Citation1985). To improve readability, we will use the term “sports” to refer to “sports and physical exercise”.

References

- Abbiss, C. R., Peiffer, J. J., Meeusen, R., & Skorski, S. (2015). Role of ratings of perceived exertion during self-paced exercise: What are we actually measuring? Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 45(9), 1235–1243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0344-5

- Abelson, R. P. (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97(1), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129

- Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022170

- Bakker, A. B. (2014). Daily fluctuations in work engagement: An overview and current directions. European Psychologist, 19(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000160

- Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2011). Subjective well-being in organizations. In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), Handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 178–189). Oxford University Press.

- Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2019). Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: A self- determination and self-regulation perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

- Bakker, A. B., Petrou, P., & Tsaousis, I. (2012). Inequity in work and intimate relationships: A spillover-crossover model. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 25(5), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2011.619259

- Beedie, C. J., Terry, P. C., & Lane, A. M. (2000). The profile of mood states and athletic performance: Two meta-analyses. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200008404213

- Breen, D., Norris, M., Healy, R., & Anderson, R. (2018). Marathon pace control in masters athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 13(3), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0730

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Hetland, J. (2012). The measurement of state work engagement: A multilevel factor analytic study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(4), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000111

- Brown, D. J., Arnold, R., Reid, T., & Roberts, G. (2018). A qualitative exploration of thriving in elite sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1354339

- Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Application and data analysis methods. Sage.

- Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 100(2), 126–131. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20056429

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

- Daniel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2014). Work to non-work enrichment: The mediating roles of positive affect and positive work reflection. Work & Stress, 28(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.872706

- De Bloom, J., Vaziri, H., Tay, L., & Kujanpää, M. (2020). An identity-based integrative needs model of crafting: Crafting within and across life domains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(12), 1423–1446. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000495

- de Vries, J. D., van Hooff, M. L., Guerts, S. A., & Kompier, M. A. (2017). Exercise to reduce work-related fatigue among employees: A randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(4), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3634

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499

- Du, D., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2018). Daily spillover from family to work: A test of the work-home resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000073

- Dunton, G. F. (2017). Ecological momentary assessment in physical activity research. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 45(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000092

- Eldor, L., Harpaz, I., & Westman, M. (2020). The work/nonwork spillover: The enrichment role of work engagement. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051816647362

- Fullagar, H. K. H., Skorski, S., Duffield, R., Hammes, D., Coutts, A. J., & Meyer, T. (2015). Sleep and athletic performance: The effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 45(2), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0260-0

- Gordon, H. J., Demerouti, E., Le Blanc, P. M., Bakker, A. B., Bipp, T., & Verhagen, M. A. (2018). Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.002

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

- Hamaker, E. L. (2012). Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (p. 43–61). The Guilford Press.

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2680.6.4.307

- Hox, J. J. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hyde, A. L., Maher, J. P., & Elavsky, S. (2013). Enhancing our understanding of physical activity and wellbeing with a lifespan perspective. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i1.6

- Ilies, R., Liu, X. Y., Liu, Y., & Zheng, X. (2017). Why do employees have better family lives when they are highly engaged at work? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(6), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000211

- Kacmar, K. M., Crawford, W. S., Carlson, D. S., Ferguson, M., & Whitten, D. (2014). A short and valid measure of work-family enrichment. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035123

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2020). The long reach of the leader: Can empowering leadership at work result in enriched home lives? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000177

- Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J., Friesen, A. P., Beedie, C. J., Fullerton, C. L., & Stanley, D. M. (2016). How should I regulate my emotions if I want to run faster? European Journal of Sport Science, 16(4), 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2015.1080305

- Lapierre, L. M., Li, Y., Kwan, H. K., Greenhaus, J. H., DiRenzo, M. S., & Shao, P. (2018). A meta‐analysis of the antecedents of work–family enrichment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2234

- Lawson, K. M., & Lee, S. (2018). Better previous night sleep is associated with less next day work-to-family conflict mediated by higher work performance among female nursing home workers. Sleep Health, 4(5), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.07.005

- Li, R. T., Kling, S. R., Salata, M. J., Cupp, S. A., Sheehan, J., & Voos, J. E. (2016). Wearable performance devices in sports medicine. Sports Health, 8(1), 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738115616917

- Lin, K. J., Ilies, R., Pluut, H., & Pan, S. Y. (2017). You are a helpful co-worker, but do you support your spouse? A resource-based work-family model of helping and support provision. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 138, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.12.004

- Litwiller, B., Snyder, L. A., Taylor, W. D., & Steele, L. M. (2017). The relationship between sleep and work: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(4), 682–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000169

- Loi, R., Xu, A. J., Chow, C. W. C., & Chan, W. W. H. (2020). Linking customer participation to service employees’ work‐to‐family enrichment: The role of job crafting and OBSE. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(2), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12291

- Luth, M. T., Flinchbaugh, C. L., & Ross, J. (2017). On the bike and in the cubicle: The role of passion and regulatory focus in cycling and work satisfaction. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 28, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.10.003

- MacMahon, C., Schücker, L., Hagemann, N., & Strauss, B. (2014). Cognitive fatigue effects on physical performance during running. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 36(4), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0249

- McGrath, E., Cooper‐Thomas, H. D., Garrosa, E., Sanz‐Vergel, A. I., & Cheung, G. W. (2017). Rested, friendly, and engaged: The role of daily positive collegial interactions at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(8), 1213–1226. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2197

- McKee-Ryan, F. M., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- McNall, L. A., Masuda, D. A., Shanock, L. R., & Nicklin, J. M. (2011). Interaction of core self-evaluations and perceived organizational support on work-to-family enrichment. The Journal of Psychology, 145(2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2010.542506

- Molan, C., Kelly, S., Arnold, R., & Matthews, J. (2019). Performance management: A systematic review of processes in elite sport and other performance domains. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1440659

- Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021484

- Newman, D. A. (2014). Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 372–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114548590

- Nezlek, J. B. (2011). Multilevel modeling for social and personality psychology. Sage.

- Nielsen, K., & Abildgaard, J. S. (2012). The development and validation of a job crafting measure for use with blue-collar workers. Work and Stress, 26(4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.733543

- Nikolaidis, P. T., & Knechtle, B. (2018). Pacing strategies in the ‘Athens classic marathon’: Physiological and psychological aspects. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1539–1539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01539

- Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research. An introduction and some practical recommendations. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000009

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732

- Penedo, F. J., & Dahn, J. R. (2005). Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 18(2), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013

- Petrou, P., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Crafting one’s leisure time in response to high job strain. Human Relations, 69(2), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715590453

- Petrou, P., Bakker, A. B., & Van den Heuvel, M. (2017). Weekly job crafting and leisure crafting: Implications for meaning‐making and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12160

- Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1783

- Pink, M. A., Lonie, B. E., & Saunders, J. E. (2018). The challenges of the semi-professional footballer: A case study of the management of dual career development at a Victorian Football League (VFL) club. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.12.005

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Rastogi, M., & Chaudhary, R. (2018). Job crafting and work-family enrichment: The role of positive intrinsic work engagement. Personnel Review, 47(3), 651–674. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2017-0065

- Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2000). Event-sampling and other methods for studying everyday experience. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 190–222). Cambridge University Press.

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5-12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

- Santos-Lozano, A., Collado, P. S., Foster, C., Lucia, A., & Garatachea, N. (2014). Influence of sex and level on marathon pacing strategy. Insights from the New York City race. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(11), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1367048

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

- Siu, O. L., Bakker, A. B., Brough, P., Lu, C.-Q., Wang, H., Kalliath, T., O'Driscoll, M., Lu, J., & Timms, C. (2015). A three-wave study of antecedents of work-family enrichment: The roles of social resources and affect. Stress and Health : journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 31(4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2556

- Siu, O-l., Lu, J-f., Brough, P., Lu, C-q., Bakker, A. B., Kalliath, T., O'Driscoll, M., Phillips, D. R., Chen, W-q., Lo, D., Sit, C., & Shi, K. (2010). Role resources and work-family enrichment: The role of work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.06.007

- Skovgaard, C., Christensen, P. M., Larsen, S., Andersen, T. R., Thomassen, M., & Bangsbo, J. (2014). Concurrent speed endurance and resistance training improves performance, running economy, and muscle NHE1 in moderately trained runners. Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(10), 1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01226.2013

- Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). The job crafting questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i2.1

- Song, Z., Foo, M.-D., & Uy, M. A. (2008). Mood spillover and crossover among dual-earner couples: A cell phone event sampling study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.443

- Sonnentag, S., Eck, K., Fritz, C., & Kühnel, J. (2020). Morning reattachment to work and work engagement during the day: A look at day-level mediators. Journal of Management, 46(8), 1408–1428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319829823

- Sonnentag, S., & Jelden, S. (2009). Job stressors and the pursuit of sport activities: A day-level perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014953

- Straub, C., Beham, B., & Islam, G. (2019). Crossing boundaries: Integrative effects of supervision, gender and boundary control on work engagement and work-to-family positive spillover. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2831–2854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1340324

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027974

- Teng, E., Zhang, L., & Lou, M. (2020). Does approach crafting always benefit? The moderating role of job insecurity. The Journal of Psychology, 154(6), 426–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2020.1774484

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Tønnessen, E., Svendsen, I. S., Olsen, I. C., Guttormsen, A., & Haugen, T. (2015). Performance development in adolescent track and field athletes according to age, sex and sport discipline. PLoS One, 10(6), e0129014–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129014

- Van den Heuvel, M., Demerouti, E., & Peeters, M. C. (2015). The job crafting intervention: Effects on job resources, self‐efficacy, and affective well‐being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12128

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

- Young, B. W., Medic, N., Weir, P. L., & Starkes, J. L. (2008). Explaining performance in elite middle-aged runners: Contributions from age and from ongoing and past training factors. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(6), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.6.737