Abstract

Over the past decade, evidence has accumulated to suggest that bisexual people experience higher rates of poor mental health outcomes compared to both heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals. However, no previous meta-analyses have been conducted to establish the magnitude of these disparities. To address this research gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported bisexual-specific data on standardized measures of depression or anxiety. Of the 1,074 full-text articles reviewed, 1,023 were ineligible, predominantly because they did not report separate data for bisexual people (n = 562 studies). Ultimately, 52 eligible studies could be pooled in the analysis. Results indicate that across both outcomes, there is a consistent pattern of lowest rates of depression and anxiety among heterosexual people, while bisexual people exhibit higher or equivalent rates in comparison to lesbian/gay people. On the basis of empirical and theoretical literature, we propose three interrelated contributors to these disparities: experiences of sexual orientation-based discrimination, bisexual invisibility/erasure, and lack of bisexual-affirmative support. Implications for interventions to improve the health and well-being of bisexual people are proposed.

In the first decades of scholarship on sexual minority mental health, bisexual people were largely invisible, often due to pooling with other sexual orientation groups. In most studies, bisexual people were either lumped together with all other sexual minority individuals for comparisons between lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) and heterosexual groups, or were classified as either lesbian/gay or heterosexual on the basis of the gender/sexFootnote1 of their current partner (Ulrich, Citation2011). This practice was identified in a 2012 content analysis of PubMed-indexed studies containing the term “bisexual” or “bisexuality” that were published in 1987, 1997, or 2007. Of the 348 studies they examined, Kaestle and Ivory (Citation2012) found that only 12.9%, 10.3%, and 17.9% (for the three time periods, respectively) reported separate data for bisexual participants. Monro, Hines, and Osborne (Citation2017) reported similar findings from their content analysis of books in the area of sexuality studies published between 1970 and 2015. More than one-quarter of the texts identified did not name bisexuality at all, despite inclusion of lesbian and gay content. As a result, little was known about the specific health needs or concerns of bisexual people for many years (Kaestle & Ivory, Citation2012; Rust, Citation2009).

This practice has shifted in the most recent decade, however, perhaps finally in response to the critiques of bisexual academics and activists (e.g., Firestein, Citation1996; Rust, Citation2000c, Citation2009) who have long made the argument for more meaningful inclusion of this “silenced sexuality” (Barker & Landridge, Citation2008) in academic research, health care provision, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer (LGBTQ) community activism. In more contemporary research on sexual minority mental health, many studies now disaggregate data from bisexual participants. This disaggregation has proved to be significant, because much of the resulting research has revealed disparities in mental health outcomes for bisexual people, relative to both lesbian/gay and heterosexual comparison groups (e.g., Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, & McCabe, Citation2010; Jorm, Korten, Rodgers, Jacomb, & Christensen, Citation2002; Pakula, Shoveller, Ratner, & Carpiano, Citation2016; Steele, Ross, Dobinson, Veldhuizen, & Tinmouth, Citation2009). Indeed, in their recent narrative summary of empirical research on bisexual health, Feinstein and Dyar (Citation2017) concluded that “there is strong evidence that bisexual individuals are at increased risk for mental health and substance use problems” (p. 1).

Despite this growing body of evidence, to our knowledge only one systematic review (Pompili et al., Citation2014) exists, and no meta-analyses have been conducted specifically to examine the mental health status of bisexual people. Consistent with the trends in research more generally, early systematic reviews examining mental health among sexual minority people combined data from bisexual, gay, and lesbian groups (e.g., King et al., Citation2008; Lewis, Citation2009; Meyer, Citation2003), potentially obscuring important differences. Pompili et al. (Citation2014) conducted a systematic review specifically to examine the risk of suicidal behavior among bisexual people; they concluded that bisexual people had an increased risk for suicide attempts relative to both heterosexual and gay/lesbian people. We could identify only two other systematic reviews that, though not specifically focused on bisexuals, included a separate analysis for bisexual people; these similarly reported that group differences in rates of depression, suicidality (Plöderl & Tremblay, Citation2015), and above-threshold scores on the General Health Questionnaire (Semlyen, King, Varney, & Hagger-Johnson, Citation2016) were strongest for the bisexual group. Data from systematic reviews and meta-analyses that disaggregate data from bisexual people are therefore warranted to contribute to a more fulsome understanding of this body of evidence. Pooling across studies provides a more accurate estimate of the magnitude of disparities and allows for systematic investigation of factors that may produce important variations within them (e.g., gender/sex, age).

To address this research gap, the current study had two broad goals: (a) to use systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize the evidence for disparities in the prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people relative to both heterosexual and gay/lesbian comparison groups; and (b) to draw from the available qualitative, quantitative, and theoretical literature on bisexual mental health to hypothesize the mechanisms that could explain any observed disparities. We focus on depression and anxiety specifically in this report due to their high past-year and lifetime prevalence rates in the general population (e.g., Bostwick et al., Citation2010); among mental health conditions, these two collectively are likely to reflect the greatest burden for bisexual people.

We approach this work as a team of bisexual and allied researchers operating from within a transformative paradigm (Mertens, Citation2003, Citation2007), that is, an orientation to research which foregrounds attention to social justice and draws from a plurality of methodological approaches in an attempt to address social inequities through knowledge production (Mertens, Citation2003). Drawing from this orientation, we note that we have deliberately and reflexively chosen our focus on depression and anxiety, experiences that are framed through a biomedical lens as “negative outcomes.” This focus is because we believe that a more complete understanding of these experiences is necessary to develop effective clinical and social interventions for those bisexual people who need them. However, at the same time, we agree that biomedical interpretations of psychological distress associated with experiences of oppression are problematic (Barker, Citation2015), and as a consequence, we take up experiences of oppression explicitly in our interpretation of our findings (in sections that follow).

Further, it is important to emphasize that across studies the majority of bisexual people do not report depression, anxiety, or other negative health outcomes. Although it is beyond the scope of the current article to review in depth, we want to acknowledge the value of research, particularly in the area of positive psychology, that has begun to characterize the positive aspects of bisexual identity and experience (e.g., Flanders, Tarasoff, Legge, Robinson, & Gos, Citation2017; Rostosky, Riggle, Pascale-Hague, & McCants, Citation2010), as well as sites of bisexual resistance (e.g., Barker, Citation2015; Eisner, Citation2013). Ultimately, our hope is that learnings from both perspectives can be complementary to each other in the development of interventions and social actions to support the well-being of all bisexual people.

What Is Bisexuality?

Before discussing our review of the literature, it is necessary to operationalize bisexuality, considering that this term is used in various ways across different academic disciplines and communities. This variability stems from the variety of ways in which the broader construct of sexual orientation can be operationalized; as many have noted, sexual orientation can be defined on the basis of sexual attraction, sexual behavior, or self-identity, and these three definitions overlap only partially with one another (e.g., Meyer, Rossano, Ellis, & Bradford, Citation2002).

The concept of bisexuality, however, introduces even more complexity to these three definitions. For example, a behavioral definition of bisexuality will capture a different group of bisexuals depending on the time frame used (e.g., lifetime versus past year); these differences are very relevant to understanding health disparities because they confound bisexual status with number of sexual partners (i.e., by definition, bisexual behavioral status requires at least two partners over some time frame, while monosexual behavioral status requires only one; Bauer & Brennan, Citation2013). Identity-based definitions may be similarly complex, in that identity labels such as queer, pansexual, and Two-Spirit are often used to denote multigender/sex attraction or relationships, either alone or in combination with the bisexual label (Ross et al., Citation2017). To encompass the breadth of relevant self-identities, researchers have proposed potential umbrella terms such as plurisexual (Mitchell, Davis, & Galupo, Citation2015) or nonmonosexual (Dyar, Feinstein, Schick, & Davila, Citation2017) to include all individuals with the potential for multigender/sex attraction.

For the purposes of the current study, our interest is in bisexuality broadly defined, that is, including those who could be classified as bisexual on the basis of multigender/sex attraction, sexual behavior, and/or choice of bisexual or another plurisexual self-identity. However, we recognize that the specific definition of bisexuality applied can yield different answers to a question about health disparities. For this reason, we examine bisexual definition as a potential source of heterogeneity in our meta-analyses to follow. We return in later sections to a discussion of the extent to which our findings can be generalized across the multiple facets of this broad definition of bisexuality.

Method

Search Strategy

Our search strategy was developed by the first author in collaboration with a coauthor who has a background in library and information sciences. The strategy was then reviewed by a professional librarian prior to execution. The first author executed the search, which included the following databases: MEDLINE (OVID, including e-pub ahead of print, in process, and other nonindexed citations), PsycINFO (OVID), CINAHL (EBSCO), LGBT Life (EBSCO), and Scopus, from 1995 to December 15, 2016. We chose 1995 as the earliest date for two reasons: (a) out of concern that study designs in sexual minority research conducted prior to 1995 might largely lack rigor (e.g., insufficient inclusion of sampling settings that would adequately reach bisexual people) and (b) considering that the prior systematic review on suicidality among bisexual people (Pompili et al., Citation2014) found no studies published prior to 1995 despite searching as far back as 1987.

Subject headings and keywords were selected as appropriate for each database. For example, the MEDLINE search included the following search terms: “bisexuality” (subheading), “bisexual*” (title, abstract, or author keyword), “major depression” (subheading), “affective disorders” (subheading), “atypical depression” (subheading), “depress*” (title, abstract, or author keyword), “mood disorder” (title, abstract, or author keyword), “anxiety” (subheading), “anxiety disorders” (subheading), “stress disorders, post-traumatic” (subheading), “anxiety” (title, abstract, or author keyword), “posttraumatic stress” (title, abstract, or author keyword), “panic” (title, abstract, or author keyword), and “obsessive compulsive” (title, abstract, or author keyword). We also checked the reference lists of recent review articles (e.g., Feinstein & Dyar, Citation2017; Plöderl & Tremblay, Citation2015) to identify any relevant citations that might have been missed in our search (we found none).

Study Selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion in our review if they were published in a peer-reviewed source since 1995 in English, French, or Spanish. These three languages were chosen for feasibility reasons (because they were spoken by our author team), but were also the three most common languages across all databases searched. For inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies had to report original quantitative data on one of our outcomes of interest specific to bisexual people, as defined on the basis of self-identity, sexual behavior, or sexual attraction. We excluded studies that recruited participants through a clinical setting (e.g., mental health or substance use treatment service), in that these samples would be expected to have rates of depression and anxiety higher than those in the general population. Similarly, we excluded studies in which the samples were entirely composed of groups known to be at elevated risk for mental health problems (e.g., HIV-positive people, homeless people).

With the aid of the Covidence systematic review application (http://www.covidence.org), titles and abstracts for each potential source were independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers according to the noted criteria; any conflicts were resolved by the first author. During title/abstract screening, qualitative, theoretical, and review articles potentially of interest for the second part of the study (i.e., narrative review of mechanisms) were also flagged and itemized separately. Articles that passed title/abstract screening were similarly assessed by two independent reviewers at the full-text screening stage to determine whether original data specific to bisexual people were reported as one of the outcomes of interest; conflicts were again resolved by the first author.

Data Extraction

Data reporting the outcomes of interest for bisexual, gay/lesbian, and/or heterosexual groups were extracted into a standardized data extraction spreadsheet. We extracted data separately for all groups reported in an individual article (e.g., on the basis of gender/sex, age) and also extracted other relevant data, including sample size, year of data collection, and sample type (e.g., population based, convenience). Initial data extraction was checked by a second reviewer. Immediately prior to final analysis, all included data were checked again by one of the first two authors.

In our initial extractions, we included data on any outcomes that could broadly be defined as indicators of depression or anxiety. At the analysis stage, we determined which outcomes were reported in sufficient studies that data were appropriate to pool (i.e., at least two studies reporting on different data sets). We found that the most commonly reported outcomes were indicators of current symptoms, which were measured using a variety of standardized instruments and reported either as a continuous variable or as a binary outcome using an accepted cutoff score to indicate clinically important levels of symptoms. Considering the relatively limited available data, we opted to pool together studies that used different measurement tools, so long as the tools were published, standardized measures (e.g., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Beck Depression/Anxiety Inventory; subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory). The only other time frames for which sufficient data (i.e., more than one study) were available to pool were past 12 months and lifetime. Again, considering the relatively limited data, for these time frames we opted to pool data that reported on major depressive episode, major depressive disorder, and any mood disorder. For anxiety, we found that the majority of studies reported on any anxiety disorder; the only specific anxiety disorder for which sufficient data were also available for pooling was generalized anxiety disorder.

Consistent with Cochrane recommendations (Higgins et al., Citation2011), we did not use a quality assessment tool to appraise individual articles but rather used sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of potentially important indicators of quality. For our data set, we determined sample type to be the most significant quality indicator for which sufficient data were available for analysis; other potential indicators of quality were either inadequately reported (e.g., response rate) or had insufficient variability for analysis (e.g., data collection medium, which was very predominantly self-report in the included studies).

Statistical Analysis

For the continuous outcomes, we included only studies that reported mean scores and standard deviations for a bisexual group and a comparison group to calculate a pooled standardized mean difference between groups. For binary outcomes, we used prevalence data to first calculate a pooled estimate of the proportion for bisexual, lesbian/gay, and heterosexual groups, and then subsequently calculated a pooled odds ratio (OR) for the difference in proportion between bisexual and lesbian/gay, and bisexual and heterosexual groups. For the calculation of the pooled OR, we included ORs we calculated ourselves on the basis of proportion data; and where no proportion data were reported, we included unadjusted ORs reported by study authors. Considering that relatively few studies reported adjusted ORs, and that there was not consistency in the variables adjusted in these models, we opted to report only unadjusted ORs and excluded studies that reported only adjusted ORs and no proportion data. For all studies that reported multiple groups of bisexual people (e.g., on the basis of gender/sex or age) we treated the data from each group as a separate estimate in our analyses, so long as the groups were mutually exclusive.

For continuous outcomes and ORs, we used restricted maximum likelihood random effects models to calculate pooled estimates for each outcome; for proportions, we used the DerSimonian-Laird estimator (Viechtbauer, Citation2010). Random-effects analysis was selected a priori considering the diversity across studies in terms of study design, measure of the outcome, and sampling method (Borenstein, Hedges, & Rothstein, Citation2007). Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using I2, which estimates the proportion of the total variance in the estimate that is due to study heterogeneity (Higgins & Thompson, Citation2002). Due to the variability in settings, populations, and outcome measures, high heterogeneity was anticipated a priori. While statistical heterogeneity may preclude data pooling in some meta-analyses of clinical or pharmacological effects, for the present study we present pooled estimates even in the context of high heterogeneity, with the aim of investigating and hypothesizing potential study-level covariates that contribute to between-study differences (Davis, Mengersen, Bennett, & Mazerolle, Citation2014; Higgins & Green, Citation2011).

We explored potential sources of heterogeneity by calculating pooled estimates for the following subgroups, where at least two studies or subsamples were available: (a) gender/sex (female, male, which were the only categories reported in most studies); (b) age (as defined in the original studies: adolescent [typically aged < 18 years], young adult [typically aged 18 to 30 years], adult [age range extending beyond 30 years]); and (c) sample type (population based, LGBTQ convenience, other convenience, or network). Population-based samples were randomly selected from defined sampling frames that include measures of sexual identity, behavior, or attraction. LGBTQ convenience samples were those recruited from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer-specific venues or sources, such as Pride events or LGBTQ-specific online forums (sometimes in addition to non-LGBTQ sources). Other convenience samples were those recruited from non-LGBTQ-specific venues and sources. Finally, network samples included participant-driven sampling methods, such as snowball sampling or respondent-driven sampling.

We used the R metafor package (Schwarzer, Citation2007; Viechtbauer, Citation2010) for all analyses.

Narrative Review

Our critical analysis of literature examining potential mechanisms for disparities in depression and anxiety among bisexual people relative to people of other sexual orientations utilized a narrative literature review approach, sometimes also described as a nonsystematic literature review (Cook & West, Citation2012). Unlike systematic literature reviews, which synthesize every available eligible study on a given topic, narrative reviews allow for a more flexible and selective approach to literature synthesis. For this reason, a narrative review was more appropriate for our goal of examining potential mechanisms, in that this approach facilitated inclusion of literature from various disciplines and utilizing various methodologies and approaches (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, and theoretical) that were not always directly comparable to one another. Because of this flexibility, narrative reviews are useful in drawing new insights from multidisciplinary bodies of literature (Cook & West, Citation2012).

The search conducted for the systematic literature review portion of our project served as the starting point for our narrative review; mechanistic studies (including qualitative and theoretical papers) were flagged in the screening process, as described previously. These identified studies were then supplemented with additional articles identified through subsequent targeted searching (e.g., for studies addressing intersections of bisexuality and racialized identities), with articles identified from the reference lists of previously included articles, and with seminal articles in the field already known to the author team. This collective body of literature was then reviewed by the first author, who independently identified key themes across studies. The proposed themes were discussed with the other authors, and further expanded or supported with additional literature where indicated, to result in the final version of our narrative review presented here.

Results

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

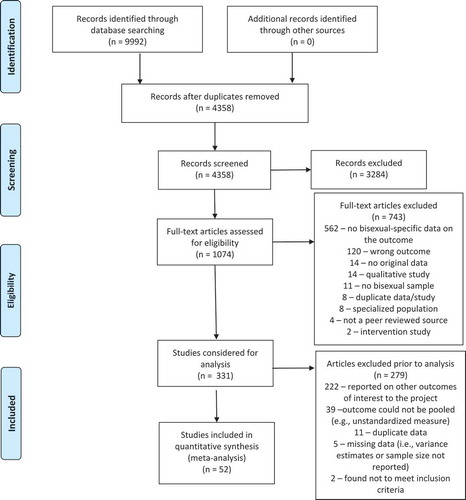

After removal of duplicates, 4,358 studies were screened at the title/abstract stage, and 1,074 studies were included for full-text review. Of note, 562 (75.6%) of the 743 studies excluded at the full-text-review stage were excluded because they did not report bisexual-specific data on the outcomes of interest (i.e., had pooled bisexual participants with other sexual minorities) (see ).

Of the 331 studies that passed full-text screening, a total of 109 articles reporting on depression or anxiety were considered for inclusion in the meta-analysis (the remainder reported data for other mental health and substance use outcomes of interest in our larger systematic review project; results from these outcomes will be reported elsewhere). A further 57 articles had to be excluded from our analysis for reasons including missing data (e.g., no variance estimates reported), because the outcome was measured in a manner that was inappropriate to pool with the other studies (e.g., unusual time intervals, such as past three years depression diagnosis), and because the study reported data that were also reported in another included study (e.g., multiple studies reporting data from the same population-based surveys, such as the U.S. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health and the U.S. National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions). In these latter cases, the publication reporting the maximum number of usable comparisons (i.e., subgroup analyses) was selected for inclusion in our analysis. These exclusions resulted in a final total of 52 studies that could be included in the meta-analysis. A full listing of both the included and excluded studies is available in the Supplemental Materials, and a summary of the characteristics of the included studies is provided in . In brief, the included studies were very predominantly conducted in North America, very predominantly used an identity-based measure of bisexuality, were largely drawn from population-based surveys, and predominantly included adult or young adult samples.

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies Included in a Meta-Analysis of Depression and Anxiety Among Bisexual People (N = 52)

Depression

Continuous measures of current depressive symp-toms

A total of 19 individual studies reporting 25 estimates was available for the comparison of continuous depression scores between bisexual and lesbian/gay groups (each study with multiple estimates reported data separately for men and women). These 25 estimates yielded a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.21 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.27) (see ). Between-study heterogeneity (I2) was 50.7%. Expressed as a Cohen’s d value of 0.21, this translates into a small effect size, thus indicating that depression scores of bisexual people are higher than those of lesbian/gay people by an average of 0.21 standard deviations.

Figure 2. Standardized mean difference (SMD), continuous measures of current depression, bisexual compared with lesbian/gay groups.

Eleven studies reported 14 estimates for the comparison of continuous depression scores between bisexual and heterosexual groups, resulting in a pooled SMD of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.37, 0.47) (see ). Between-study heterogeneity (I2) was 0.01%. Expressed as a Cohen’s d value of 0.42, this reflects a medium effect size; thus, the depression scores of bisexual people are on average 0.42 standard deviations higher than those of heterosexual people.

Current binary indicators of depression

A total of 23 individual studies reported 26 estimates of the proportion of bisexual participants reporting current depression using a binary indicator (e.g., scoring over an established cutoff value on a continuous depression measure). These studies yielded a pooled prevalence of depression of 0.23 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.27) with between-study heterogeneity (I2) of 94.6% (please note that all meta-analysis figures not included in the text are available in the online Supplemental Materials). In comparison, the 20 studies reporting data for a lesbian/gay comparison group yielded a pooled depression prevalence of 0.18 (95% CI: 0.16, 0.21; I2 = 91.2%), and the 17 studies reporting data for a heterosexual comparison group yielded a pooled depression prevalence of 0.13 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.15; I2 = 99.8%). Converting these proportion data into odds ratios (OR) yielded a pooled OR of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.70; I2 = 73.3%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to lesbian/gay participants (see ) and a pooled OR of 2.38 (95% CI: 1.86, 3.05; I2 = 91.7%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to heterosexual participants (see ).

Past 12 months major depression or mood disorder

Only four studies reported bisexual-specific data for past 12 months major depression, major depressive episode, or mood disorder according to a diagnostic assessment (e.g., Diagnostic Interview Schedule; Robbins, Helzer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, Citation1981); pooling other (unstandardized) assessments of past 12 months depression/mood disorder resulted in prevalence levels that were not interpretable (i.e., past 12 months prevalence rates that were higher than lifetime prevalence rates).

Pooling the five estimates provided in these four studies resulted in a past 12 months prevalence of 0.30 (95% CI: 0.31, 0.51) among bisexual people, with between-study heterogeneity of I2 = 92.0. In comparison, the pooled prevalence estimate was 0.30 (95% CI: 0.17, 0.44; I2 = 95.7%) for the gay/lesbian group and 0.16 (95% CI: 0.07, 0.28; I2 = 98.5%) for the heterosexual group. Converting these proportion data into OR yielded a pooled OR of 1.03 (95% CI: 0.57, 1.84; I2 = 62.3%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to lesbian/gay participants and a pooled OR of 3.17 (95% CI: 1.60, 6.27; I2 = 49.5%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to heterosexual participants.

Lifetime major depression or mood disorder

Again, only four studies reported bisexual-specific data for lifetime major depression, major depressive episode, or mood disorder according to a diagnostic assessment. Pooling the five estimates provided in these four studies yielded a pooled prevalence of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.31, 0.55; I2 = 88.4) among bisexual people, 0.42 (95% CI: 0.29, 0.55; I2 = 96.1%) for the gay/lesbian group, and 0.25 (95% CI: 0.16, 0.36; I2 = 99.8%) for the heterosexual group. Expressed as an OR, the pooled OR was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.74, 1.37; I2 = 53.7%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to lesbian/gay participants and 2.09 (95% CI: 1.15, 3.81; I2 = 76.3%) for the comparison of bisexual participants to heterosexual participants.

Anxiety

Continuous measures of current anxiety symp-toms

Ten studies reported 13 estimates of continuous anxiety scores among bisexual people relative to a comparison group. These estimates yielded a SMD of 0.21 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.27; I2 = 27.7%) for the comparison of anxiety scores between bisexual and gay/lesbian people, equivalent to a small effect size of 0.21 standard deviations. The comparison of bisexual people with heterosexual people, for which only four studies were available, yielded a SMD of 0.37 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.54; I2 = 63.6%), equivalent to a small to moderate effect size.

Current binary indicators of anxiety

Seven studies reported 10 estimates of current anxiety based on a binary indicator; these resulted in a pooled prevalence estimate of 0.24 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.28; I2 = 92.7%). In comparison, the pooled prevalence of anxiety among lesbian/gay participants (based on five studies) was 0.14 (95% CI: 0.11, 0.17; I2 = 94.8%) and among heterosexual participants (based on three studies) was 0.06 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.09; I2 = 99.8%). Expressed as an OR, comparing current binary indicators of anxiety between bisexual and lesbian/gay participants yielded a pooled OR of 1.61 (95% CI: 1.37, 1.89; I2 = 62.0%), and the three studies providing a comparison between bisexual and heterosexual participants yielded a pooled OR of 3.29 (95% CI: 2.79, 3.87; I2 = 64.8%).

Past 12 months, any anxiety disorder

Four studies reported five estimates of past 12 months anxiety disorder (McNair, Kavanagh, Agius, & Tong, Citation2005 reported estimates for both young adult and adult samples). Among bisexual participants, this yielded a pooled prevalence estimate of 0.52 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.70; I2 = 96.3%). In comparison, the pooled prevalence for past 12 months anxiety disorder among lesbian/gay people was 0.46 (95% CI: 0.29, 0.63; I2 = 97.9) and among heterosexual people was 0.33 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.56; I2 = 99.9). Converted to an OR, the pooled OR for bisexual people compared to lesbian/gay people was 1.36 (95% CI: 1.07, 1.73; I2 = 29.6%) and compared to heterosexual people was 1.88 (95% CI: 1.09, 3.24; I2 = 83.6%).

Lifetime, any anxiety disorder

Only three studies reported on lifetime anxiety disorder among bisexual people, providing a total of four estimates; only one of these studies included a heterosexual group (Bolton & Sareen, Citation2011, which reported estimates for men and women separately and therefore permitted pooling). The pooled prevalence of lifetime anxiety disorder was 0.60 among bisexual people (95% CI: 0.38, 0.79; I2 = 95.0%), 0.53 among lesbian/gay people (95% CI: 0.38, 0.67; I2 = 95.0%), and 0.29 among heterosexual people (95% CI: 0.16, 0.44; I2 = 99.9%). The pooled OR for lifetime anxiety disorder among bisexual people compared to lesbian/gay people was 1.35 (95% CI: 0.82, 2.22; I2 = 73.4%) and compared to heterosexual people was 2.70 (95% CI: 1.93, 3.77; I2 = 34.1).

Lifetime, generalized anxiety disorder

The only specific anxiety disorder for which sufficient data were available for meta-analysis was generalized anxiety disorder. Two studies reporting three estimates yielded a pooled prevalence of lifetime generalized anxiety disorder of 0.15 among bisexual people (95% CI: 0.08, 0.24; I2 = 73.1%), 0.13 among lesbian/gay people (95% CI: 0.08, 0.19; I2 = 77.8%), and 0.07 among heterosexual people (95% CI: 0.03, 0.13; I2 = 99.7%). Expressed as a pooled OR, the comparison of bisexual people to lesbian/gay people yielded an OR of 1.13 (95% CI: 0.63, 2.02; I2 = 46.6%) and the comparison of bisexual people to heterosexual people yielded an OR of 2.60 (95% CI: 1.88, 3.61; I2 = 0%). Again, this latter comparison was based on only one study (Bostwick et al., Citation2010).

Effects of gender/sex

Where data were available, we pooled analyses separately for women and men (there were insufficient data available to pool for bisexual people of other genders). For continuous measures of current depressive symptoms, the pooled SMD for bisexual women in comparison to lesbians was 0.28 (95% CI: 0.20, 0.36; I2 = 48.2%), while the comparison between bisexual and gay men yielded a pooled SMD of 0.15 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.26; I2 = 10.4%). A similar pattern of an increased magnitude of disparity for women was apparent in the binary indicators of current depression as well (pooled OR for bisexual women in comparison to lesbians of 1.74; 95% CI: 1.33, 2.27; I2 = 71.7%; pooled OR for bisexual men in comparison to gay men of 1.07; 95% CI: 0.84, 1.36; I2 = 53.7%). This gender/sex difference was not apparent in the comparison with heterosexual groups, however (SMD of 0.41 for women and 0.42 for men; 95% CI: 0.35, 0.48 and 0.14, 0.70 respectively; a similar result for the analysis of binary indicators of current depression is provided in the online Supplemental Materials).

For continuous measures of current anxiety symptoms, the pooled SMD for bisexual women in comparison to lesbians was 0.22 (95% CI: 0.13, 0.31; I2 = 47.2%), and for bisexual versus gay men was 0.18 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.33; I2 = 0). Because only one study reported a comparison of bisexual versus heterosexual men in current symptoms of anxiety, gender/sex-specific estimates could not be pooled for this outcome. However, for binary indicators of current anxiety, the pooled OR among bisexual women compared to lesbians was 1.98 (95% CI: 1.61, 2.44; I2 = 18.9%), while the pooled OR for binary indicators of current anxiety among bisexual men compared to gay men was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.16, 1.54; I2 = 0%).

Effects of age

We examined potential effects of age only for continuous and categorical measures of current depression, considering that data stratified by age were sufficiently reported only for these outcomes. The studies comparing current depressive symptoms between bisexual and gay/lesbian adolescents yielded a small and nonsignificant SMD of 0.13 (95% CI: −0.03, 0.30; I2 = 65.5%). In comparison, the pooled SMD for young adult samples was 0.19 (95% CI: 0.11, 0.27; I2 = 0%) and for adult samples was 0.24 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.34; I2 = 64.2%). However, there was no difference between the pooled ORs for adolescent, young adult, and adult samples when current binary indicators of depression were examined (data provided in online Supplemental Materials).

In comparing bisexual and heterosexual participants, the pooled SMD for adolescents was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.33, 0.54; I2 = 24.1%), for young adults was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.35, 0.48; I2 = 0%), and for adults was 0.44 (95% CI: 0.30, 0.58; I2 = 0%). The pattern was again different for binary indicators of current depression, where there was a markedly higher pooled OR for the adolescent samples (adolescent OR = 4.82; 95% CI: 3.97, 5.85; I2 = 0%; young adult OR = 2.40; 95% CI: 1.82, 3.16; I2 = 50.6%; adult OR = 2.00; 95% CI: 1.41, 2.84; I2 = 94.5%).

Effects of sample type

The majority of studies drew from either population-based samples or convenience samples recruited through LGBTQ venues; pooled SMD in continuous current depression scores for bisexual versus lesbian/gay samples recruited through these two methods were comparable (population based: SMD = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.33; I2 = 19.2%; LGBTQ convenience samples: SMD = 0.27; 95% CI: 0.18, 0.35; I2 = 53.4%; similar findings for binary current indicators of depression, as reported in Supplemental Materials). In contrast, the pooled SMD for convenience samples recruited through non-LGBTQ venues was smaller (SMD = 0.03; 95% CI: −0.20, 0.25; I2 = 63.1%). A similar pattern, though less pronounced, was present in the data for continuous measures of current anxiety symptoms (population based: SMD = 0.20; 95% CI: 0.00, 0.39; I2 = 6.1%; LGBTQ convenience samples: SMD = 0.23; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.31; I2 = 38.0%; non-LGBTQ convenience samples: SMD = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.27; I2 = 0%).

In comparing bisexual and heterosexual individuals, there were insufficient data using LGBTQ convenience samples for analysis. Effects for population-based and non-LGBTQ convenience samples were similar (for continuous measures of current depression symptoms, population based: SMD = 0.44; 95% CI: 0.36, 0.52; I2 = 13.5%; non-LGBTQ convenience samples: SMD = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.50; I2 = 0%; for binary measures of current depression, population based: OR = 3.01; 95% CI: 2.42, 3.75; I2 = 87.2%; LGBTQ convenience samples: OR = 1.16; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.73; I2 = 21.2%; non-LGBTQ convenience samples: OR = 1.43; 95% CI: 1.18, 1.74; I2 = 0%). There were insufficient data reporting on continuous measures of current anxiety symptoms to compare sampling approaches between bisexual and heterosexual people.

Effects of bisexual definition

As shown in , the studies included in this review very predominantly defined bisexuality on the basis of self-identification. For continuous measures of current depression symptoms, the 14 studies using an identity-based definition yielded a pooled SMD between bisexual and lesbian/gay groups of 0.24 (95% CI: 0.17, 0.30; I2 = 49.1%). In comparison, the four studies that used an attraction-based definition yielded a pooled SMD between bisexual and lesbian/gay groups of 0.08 (95% CI: −0.11, 0.27; I2 = 45.8%). Notably, three of these four attraction-based studies were of adolescent samples, with the fourth reporting data from a follow-up wave of participants initially recruited during adolescence. Using binary indicators of current depression, there was no apparent difference between estimates based on identity versus attraction definitions (identity: OR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.21, 1.81; I2 = 75.1%; attraction: OR = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.20, 1.60; I2 = 0%). For the depression outcomes, none of the included studies reporting a lesbian/gay comparison group used a behavioral definition of bisexuality.

In comparing continuous current depression scores between bisexual and heterosexual groups across these three definitions of bisexuality, the pooled SMD was very comparable between identity-based and attraction-based definitions but lower for the two studies that used a behavioral definition (identity based: SMD = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.50; I2 = 0.01%; attraction based: SMD = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.33, 0.54; I2 = 24.1%; behavior based: SMD = 0.21; 95% CI: −0.04, 0.45; I2 = 0%). Using binary indicators of current depression, behavior-based studies also reported a smaller effect (identity based: OR = 2.30; 95% CI: 1.77, 2.97; I2 = 89.5%; attraction based: OR = 4.73; 95% CI: 3.91, 5.72; I2 = 0%; behavior based: OR = 1.43; 95% CI: 1.18, 1.74; I2 = 0%).

Summary

Across both outcomes (depression and anxiety) operationalized in a variety of ways (e.g., as a continuous measure of current symptoms; as a lifetime diagnosis), our analysis suggests a consistent pattern of lowest rates of depression/anxiety among heterosexual people, while bisexual people exhibit higher or equivalent rates in comparison to lesbian/gay people. Gender/sex and age both appear to be important moderators of the relationship between bisexuality and mental health. While there is no consistent pattern with respect to sampling type, there is some evidence that identity-based definitions yield disparities of greater magnitude than do attraction-based definitions. In the section that follows, we draw from empirical and theoretical literature to try to understand and explain these findings.

Literature Review

Despite the relatively small number of studies that could be included in our meta-analysis, there is a robust body of empirical and theoretical literature to help us understand why bisexual people might be at disproportionate risk for depression and anxiety. This literature comes predominantly from North America and the United Kingdom, and out of the social sciences, rather than health sciences (that is, the fields of psychology, sociology, and other disciplines such as gender studies). In the remainder of this article, we engage with this literature and consider it in light of the results of our meta-analysis to theorize about the mechanisms underlying the observed mental health disparities.

Our narrative review of this body of work identified three interrelated potential contributors to poor mental health outcomes among bisexual people: sexual orientation–based discrimination, bisexual invisibility and erasure, and a lack of bisexual-affirmative support. We provide a brief summary of literature addressing each of these themes in the sections that follow. Because experiences of these three proposed contributors differ in relation to other important social locations that bisexual people embody (in particular, in relation to gender/sex, age, racialization and socioeconomic status), we close with a brief discussion of the literature that examines the experiences of bisexual people living at these intersections.

Sexual orientation–based discrimination

In Meyer’s (Citation2003) seminal paper on the minority stress framework, he postulated that the disproportionate rates of poor mental health outcomes observed among sexual minority people relative to heterosexuals can be explained by the additional burden of the minority stress processes sexual minorities experience in relation to their socially stigmatized identity. Specifically, Meyer (Citation2003) proposed that experiences of both distal (e.g., experienced prejudice and discrimination) and proximal (e.g., internalized homophobia, expectations of rejection) forms of minority stress unique to sexual minority individuals can account for their increased risk for outcomes such as depression and anxiety.

While there is a robust body of evidence supporting the validity of the minority stress framework in relation to the mental health of lesbian/gay people (e.g., Fingerhut, Peplau, & Gable, Citation2010; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, Citation2008) as well as sexual minority people as a combined group (e.g., Lewis, Derlega, Griffin, & Krowinski, Citation2003; Mohr & Sarno, 2016), there is less evidence in support of the model to explain outcomes among bisexual people specifically, because across studies that have compared sexual orientation groups in this regard, bisexual people were found to report fewer discrimination events than gay or lesbian people (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, West, & McCabe, Citation2014; Herek, Citation2009; McLaren, Citation2016).

One potential explanation for this finding could be that the fundamental tenet of the minority stress framework does not apply to bisexual people; that is, that bisexual people do not experience sexual orientation–specific minority stress processes that affect their mental health. This explanation could be read through the lens of “heterosexual privilege,” or the notion that bisexual people, when partnered with different gender partners, can “pass” as heterosexual and, as a result, may be buffered from sexual orientation–related minority stress. This explanation, however, is not supported by the results of our meta-analysis: a heterosexual privilege explanation would predict levels of mental health outcomes more similar to those of heterosexuals than those of lesbian/gay individuals, rather than our finding of similar or higher levels of poor mental health outcomes among bisexuals compared to lesbian/gay people. More evidence refuting the heterosexual privilege argument comes from Dyar, Feinstein, and London’s (Citation2014) survey study of more than 100 bisexual women that found those partnered with men reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than did those partnered with women.

An alternative explanation is that bisexual people experience different forms of minority stress that may not be well captured by the quantitative instruments often used in analyses of the minority stress framework. For example, in explaining their findings of lower rates of discrimination among bisexual respondents, Bostwick et al. (Citation2014) highlighted that “experiences of stigma, prejudice and discrimination are at least qualitatively different for bisexuals” (p. 41; emphasis in the original). This explanation is supported by the results of studies that have highlighted bisexual people’s experiences of discrimination in forms that are particular to bisexuality and other nonmonosexual identities and experiences (i.e., those that involve attraction to and/or relationships with people of more than one gender/sex) (e.g., Ross, Dobinson, & Eady, Citation2010). In the remainder of this section, we review the evidence that characterizes these experiences of biphobia (i.e., negativity, prejudice, and/or discrimination against bisexual people; Ross et al., Citation2010) and monosexim (i.e., structural dismissal or disallowal of bisexuality and other nonmonosexual orientations; Ross et al., Citation2010), their impact on mental health, and implications for measurement.

In a review of attitudes toward bisexuality, Israel and Mohr (Citation2004) identified four types of negative attitudes toward bisexuality: heterosexism (negative attitudes toward same-sex relationships/attractions in general); attitudes that question the authenticity of bisexual identities; attitudes focused on the sexual desires and practices of bisexual people (often characterizing them as sexually deviant in some capacity); and attitudes related to loyalty (characterizing bisexual women in particular as less trustworthy as partners). In our own qualitative research, these attitudes have been described by bisexual people as important determinants of their mental health (Ross et al., Citation2010), and more recent qualitative and mixed methods research also describes bisexual people’s encounters with the negative attitudes characterized by Israel and Mohr (Citation2004) (Flanders, Robinson, Legge, & Tarasoff, Citation2016; Hayfield, Clarke, & Halliwell, Citation2014; Hertlein, Hartwell, & Munns, Citation2016). In Flanders, Tarasoff, and colleagues’ (Citation2017) daily diary study of positive identity experiences among young bisexual people, they found that some participants categorized a lack of negative response or a neutral response to their bisexuality from others as a positive identity experience. As Flanders, Tarasoff, et al. (Citation2017) argued, interpreting the absence of negative or neutral response as positive “says a great deal about the prevalence of biphobia and monosexism” in society (p. 1027).

Support for the hypothesis that bisexual people do, in fact, experience discrimination also comes from the small body of evidence that has assessed nonbisexual people’s attitudes toward bisexuality or bisexual people. As reviewed by Israel and Mohr (Citation2004), both quantitative and qualitative studies have established that the negative attitudes about bisexuality described are common among lesbian (Rust, Citation1993), gay (Mohr & Rochlen, Citation1999), and heterosexual (Eliason, Citation2001) people. Further, multiple studies with predominantly heterosexual samples have established that attitudes toward bisexual people are more negative on average than are attitudes toward lesbian or gay people (Eliason, Citation2001; Herek, Citation2002). Perhaps most striking is Herek’s (Citation2002) finding that attitudes toward bisexual people were more negative than attitudes toward nearly every other group assessed (including various cultural and religious groups), with the exception only of people who use injection drugs.

Most recently, Dodge and colleagues (Citation2016) assessed attitudes toward bisexuality among a national U.S. probability sample of 2,843 individuals as part of the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. In some respects, Dodge et al.’s (Citation2016) findings reflect a positive shift in the years since earlier work on attitudes. Participants in this study were most likely to endorse the Neither agree nor disagree option for each of the items in the bisexual attitudes measures used. In this regard, attitudes toward bisexuality may have shifted over time from being extremely negative (e.g., in Herek’s Citation2002 study), to a predominant attitude of neutrality. As Dodge et al. (Citation2016) noted, however, these findings depart from findings regarding attitudes toward gay and lesbian people collected in North America over the past decade. Across studies, these attitudes have shifted to be substantially more positive (e.g., Gallup, Citation2016). For example, in both the United States and Canada, the percentage of individuals saying that homosexuality should be accepted by society grew at least 10 percentage points between 2007 and 2013 (Pew Research Center, Citation2013). It is notable, of course, that this research on attitudes toward bisexuality has been almost exclusively conducted in the United States, and attitudes toward all minority sexual orientation groups remain negative in many other parts of the world (Pew Research Center, Citation2013).

Acknowledgment that bisexual-specific forms of discrimination are qualitatively different from manifestations of homophobia has led to the development of additional tools to specifically measure the discrimination experiences of bisexual people—and in particular, the Anti-Bisexual Experiences Scale (ABES, Brewster & Moradi, Citation2010). The ABES queries bisexual-specific forms of discrimination identified on the basis of prior literature (e.g., “People have not taken my sexual orientation seriously because I am bisexual”; “People have treated me as if I am obsessed with sex because I am bisexual”). Respondents are asked to report how frequently each experience has occurred for them separately for heterosexual referents and gay/lesbian referents (Brewster & Moradi, Citation2010). Research has established a relationship between ABES scores and mental health outcomes (Brewster, Moradi, Deblaere, & Velez, Citation2013).

Measurements of internalized stigma may be similarly problematic for understanding the experiences of bisexual people. For example, the original version of one of the most widely used measures of internalized homophobia includes items referencing a wish that one experienced different sex attraction (e.g., Herek, Cogan, Gillis, & Glunt, Citation1998). Other internalized homophobia scales include items assessing one’s comfort interacting with the gay/lesbian community (e.g., Szymanski & Chung, Citation2001), which may be confounded by bisexual people’s experiences of discrimination within those communities (discussed further in the text that follows). To our knowledge, only one validated instrument has been developed to specifically measure internalized biphobia: the internalized binegativity subscale of the Bisexual Identity Inventory (Paul, Smith, Mohr, & Ross, Citation2014). Preliminary analyses have suggested strong associations between internalized binegativity and depression (Paul et al., Citation2014), but research on the association between internalized biphobia and mental health is in its early stages.

In sum, there is ample evidence that bisexual people experience sexual orientation–based discrimination, and that this discrimination is qualitatively different from the discrimination faced by lesbian and gay individuals in its basis in monosexism. Considering this, our data showing equivalent or elevated rates of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to lesbian/gay people are consistent with the minority stress framework (Meyer, Citation2003), although further research, including tools that capture bisexual-specific discrimination, as well as both lesbian/gay and heterosexual comparison groups, is required to empirically test these relationships.

Bisexual invisibility and erasure

One factor that has been extensively theorized to be relevant to bisexual mental health is the invisibility of bisexuality in society (Ulrich, Citation2011). In his seminal writing on this topic, Kenji Yoshino (Citation2000) described the “epistemic contract of bisexual erasure,” wherein both heterosexual and gay/lesbian communities are invested in maintaining the “monosexual presumption” (p. 369)—that is, the assumption that all individuals are either heterosexual or gay/lesbian, and therefore bisexuality does not exist.

Yoshino (Citation2000) goes on to explain that both heterosexual and gay/lesbian people benefit from bisexual erasure, in that (a) both are invested in the notion of fixed identity categories (which bisexuality can be seen to destabilize); (b) both are invested in retaining biological sex as a fundamental category of social organization (which can be seen as irrelevant in the context of bisexuality); and (c) both may be invested upholding monogamous norms (which bisexual people are at least perceived to trouble).

A fairly extensive body of empirical literature supports the notion of bisexuality as either passively invisible, or actively erased, in societies where lesbian/gay identities are much more visible. For example, Raymond (Citation2015) traced the (in)visibility, erasure, and co-optation of bisexual activism through the growth of the lesbian/gay movement in the United States. As he described, “[N]ational organizations dealing with sexual orientation were originally established with bisexual and transgender participation, but their later organizational cultures and programmatic activities were primarily focused on the gay and lesbian communities” (p. 145; emphasis in the original). This bisexual erasure has concrete implications for bisexual individuals as it plays out in the law. Marcus (Citation2015) examined the terminology used in recent U.S.-based LGBT rights cases and described “an almost complete systemic erasure of bisexuals in briefings and opinions” (p. 291). This erasure extends into the domain of refugee claims, wherein claims from individuals seeking asylum from persecution associated with bisexuality have been far less successful than other sexual orientation–based claims (Rehaag, Citation2009).

There has been a fairly extensive body of research illuminating the invisibility of bisexuality in media representations. Just as lesbians and gay men have been described as vulnerable to the lack of adequate representation of their identities in mainstream culture (Gross, Citation2012), bisexual people may be similarly affected. Media analyses of bisexuality have predominantly highlighted the invisibility of bisexual people in popular culture, noting that where characters move between relationships with same- and different-gender partners, their sexual orientation is typically presumed to have changed, rather than to be bisexual (Alexander, Citation2007; GLAAD, Citation2015). Research suggests various mechanisms through which this social invisibility of bisexuality could contribute to poor mental health outcomes for bisexual people. For example, Johnson (Citation2016) conducted an Internet survey, with a convenience sample of more than 600 bisexual people, which asked respondents about their perceptions of media representation of bisexuality and any connections between this representation and mental health. Of those participants who had been diagnosed with at least one mental health condition, nearly 40% reported that they felt their condition or its symptoms was at least somewhat affected by media representation of bisexuality. In open-ended responses, participants explained that the lack of positive media representations of bisexuality was a barrier to coming out, in that they perceived and/or anticipated that it had or would contribute to negative responses on the part of important support people. This perception is supported by research examining the impact of lesbian/gay media portrayals, in that recollection of positive media portrayals is associated with more positive attitudes toward lesbian/gay people (e.g., Bonds-Raacke, Cady, Schlegel, Harris, & Firebaugh, Citation2008). Bisexual participants in Johnson’s (Citation2016) study also highlighted the lack of positive portrayals of bisexuality in media as a barrier to identifying and accepting their own bisexual identity. This is consistent with the findings from our qualitative study of 55 bisexual people in Ontario (Ross et al., Citation2010). In the words of one participant, “I didn’t even know bisexuality existed until I was in my early twenties… . It didn’t occur to me that there was something other than straight or gay” (p. 500).

Bisexual invisibility in media is likely reflective of the broader invisibility of bisexuality in society and everyday life (Ulrich, Citation2011). Although little research is available to elucidate the specific mechanisms, the lived experience of invisibility and erasure as a bisexual person may manifest in ways that increase risk of negative mental health outcomes. For example, we hypothesized that not seeing oneself represented in dominant culture may be related to a decreased understanding of self, lower self-esteem, a sense of disconnection from peers and community, and an internal and/or external denial of one’s sexuality.

Lack of bisexual-affirmative support

As a product of sexual orientation–based discrimination, bisexual invisibility, and bisexual erasure, many bisexual people lack a community of support that is affirmative of their sexual identity. Drawing again on the minority stress framework, Meyer (Citation2003) postulated that support from a community of like others may serve to buffer the effects of sexual orientation–based discrimination, and evidence from general sexual minority samples has confirmed that this relationship holds true across the life span and among various communities within the LGB community (e.g., in research with youth [Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, Citation2010], older adults [Kuyper & Fokkema, Citation2010], and African American men who have sex with men [Wong, Schrager, Holloway, Meyer, & Kipke, Citation2014], as just a few examples). Qualitative research suggests this also holds true for bisexual people specifically, in that support from other bisexuals, as well as bisexual-affirmative support from individuals of other sexual identities, has been identified by bisexual people as very beneficial for them (MacKay, Robinson, Pinder, & Ross, Citation2017; Ross et al., Citation2010). At the same time, however, this research also indicates that many bisexual people lack an affirmative community of support (Dodge et al., Citation2012; Hayfield et al., Citation2014; MacKay et al., Citation2017; Ross et al., Citation2010).

The reasons for this lack of community link directly to the other key themes of our narrative review. Specifically, many bisexual people report feeling unsupported and/or unwelcome (i.e., experience biphobia and monosexism) in their attempts to engage with lesbian/gay communities, yet at the same time often encounter homophobia and heterosexism in their relationships with heterosexual people (Hayfield et al., Citation2014; Ross et al., Citation2010). Results of quantitative studies assessing bisexual peoples’ experiences of biphobia and monosexism also shed light on the impact of discrimination on access to bisexual-affirmative support. For example, a large quantitative study of 745 bisexual people found that, using the ABES, participants reported only marginally more experiences of bisexual-specific discrimination from heterosexual, as compared to gay/lesbian, referents (Roberts, Horne, & Hoyt, Citation2015).

In light of these discrimination experiences, one potential opportunity for accessing bisexual-affirmative support would be through bisexual-specific communities. However, though there are flourishing and long-standing bisexual communities in some geographic regions, in many others (and particularly in small or rural areas), organized bisexual communities do not exist (Dodge et al., Citation2012; Ross et al., Citation2010). This is despite the fact that analysis of large data sets consistently finds the number of bisexual people to be equivalent to, if not larger than, the number of gay/lesbian people (Yoshino, Citation2000). As such, in regions where lesbian/gay communities exist, insufficient bisexual people to warrant such communities cannot explain their absence. This lack of bisexual-specific community support is therefore likely a consequence of bisexual invisibility and erasure—yet, at the same time, contributes to the persistence of these problems (Flanders, Dobinson, & Logie, Citation2015).

Also relevant to bisexual mental health is accessibility of bisexual-affirmative support through formal mental health systems. Here too, however, qualitative evidence suggests there are substantial gaps (Flanders et al., Citation2015). For example, in our qualitative study of 55 bisexual people in Ontario, Canada, participants described a variety of negative encounters with mental health professionals, in which these professionals enacted the very negative attitudes about bisexuality that have been described in the general population, such as assumptions that bisexuality is not a healthy, stable sexual identity and that a clinician’s role is to support the client in transitioning to a monosexual identity (Eady, Dobinson, & Ross, Citation2011). Participants also reported that their mental health providers lacked adequate knowledge about bisexuality—even when they sought services within LGBTQ-specific settings—and that they were often required to educate their providers before those providers could provide adequate care. As a result of these unsupportive experiences, the majority of participants reported avoiding formal mental health services, even in times of significant need (Eady et al., Citation2011).

These findings were echoed and extended in a more recent qualitative study by our research team, which explored 41 bisexuals’ experiences of mental health help seeking (MacKay et al., Citation2017). Our findings indicated that some bisexual people anticipated and/or experienced a lack of bisexual-affirming support at each stage of the help-seeking process, from contemplation to service access. While some participants worked hard to identify a provider who was competent in working with bisexuals, others did not know how to locate competent providers or even that this was an option. For participants who accessed mental health services, many reported experiencing microaggressions from providers. These negative experiences often led to increased stress, the termination of services, and, for some individuals, reluctance to seek further help from the mental health system. In contrast, visible and accessible bisexual-affirmative services and service providers were identified as an important service access facilitator (MacKay et al., Citation2017).

Taken together, these studies suggest that many bisexual people lack both informal and formal bisexual-affirmative supports. This lack of bisexual-affirmative support likely produces and/or exacerbates mental health vulnerabilities, both by virtue of the unavailability of support to buffer the impact of discriminatory experiences (i.e., which might otherwise prevent mental distress) and by virtue of the lack of adequate supports to aid people in addressing mental distress when it arises.

Important intersections

There is ample evidence that the experiences of sexual minority people are not homogenous. Therefore, research in this area needs to attend to important differences associated with intersections of other socially significant identities and experiences (Bowleg, Citation2008; Robinson & Ross, Citation2013). Although the relatively limited body of bisexual-specific research restricts the extent to which we are currently able to understand how these identities and experiences intersect with bisexuality in determining depression and anxiety, we review some of the available evidence here.

It is notable that, across population-based studies of sexual orientation and health, there tend to be significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of bisexual people compared to their gay/lesbian counterparts. Specifically, these population-based data suggest that bisexual people are often younger (Jorm et al., Citation2002; Tjepkema, Citation2008; Bostwick et al., Citation2014, among women only; Jabson, Farmer, & Bowen, Citation2014; Gorman, Denney, Dowdy, & Medeiros, Citation2015), more often female (Bostwick et al., Citation2014; Jabson et al., Citation2014; Tjepkema, Citation2008), and of lower socioeconomic status (Bostwick et al., Citation2014; Jabson et al., Citation2014; Jeong, Veldhuis, Aranda, & Hughes, Citation2016; Tjepkema, Citation2008) than gay/lesbian people. Although reports of potential differences in the proportion of racialized people among bisexual versus nonbisexual samples are inconsistent (e.g., Tjepkema, Citation2008, reported fewer bisexual than heterosexual or gay/lesbian people are White in a Canadian population-based sample; Gorman et al., Citation2015, found a higher proportion of Black respondents among bisexual women than heterosexual or lesbian women in a U.S. population-based sample; many other studies report no differences), it is important to note racism as an important determinant of mental health for sexual minority people of color (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni, & Walters, Citation2011; Bostwick et al., Citation2014; Díaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, Citation2001). We therefore consider intersections of bisexuality with age, gender/sex, socioeconomic status, and racialized identities in turn.

With respect to age, there is some evidence that young adult bisexual people may experience poorer mental health outcomes than their adult bisexual counterparts. In our team’s mixed methods study of more than 400 bisexual people in Ontario, Canada, we found higher rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and past-year suicidality among participants aged 16 to 24, relative to participants aged 25 and older (Ross et al., Citation2014). These findings align with data from population-based studies of adolescent or college student samples, many of which have reported the highest rates of poor mental health outcomes among bisexual participants (e.g., Azagba, Asbridge, Langille, & Baskerville, Citation2014; Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, Citation2010; Li, Pollitt, & Russell, Citation2016). It is notable, however, that in our meta-analysis, we did not find a larger magnitude of disparity between bisexual and gay/lesbian people in studies reporting on adolescent samples; indeed, we found some (albeit inconsistent) evidence that the magnitude of the disparity between sexual orientation groups may increase postadolescence. This may be because adolescence/young adulthood is a challenging time for sexual minority young people regardless of their specific sexual identity (Saewyc, Citation2011), as many face discrimination from peers, family members, and other significant people in their lives (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, Citation2009). Although we could identify few qualitative or theoretical studies examining mental health among bisexual youth specifically, it may be that bisexual youth face additional challenges in developing and disclosing a sexual identity label that is not only stigmatized but also highly invisible and poorly understood by many potential support people (Flanders et al., Citation2015; Ross et al., Citation2010). In their quantitative study of nearly 400 bisexual youth, Pollitt, Muraco, Grossman, and Russell (Citation2017) found that depressive symptoms were positively correlated with disclosure stress and negatively correlated with support from close friends and from family; in multivariate analyses, support from parents buffered the relationship between family disclosure stress and symptoms of depression. However, the determinants of bisexual mental health we have discussed (bisexual-specific discrimination; bisexuality invisibility; lack of bisexual affirmative support) may be modified by age, in that their effects may become stronger as bisexual people age. Additional research is needed to explore the impact of minority stress on bisexual identity development among youth and to determine how monosexist discrimination in particular might impact on mental health across the life course.

With respect to gender/sex, ample population-based evidence has established that women, beginning in adolescence, report higher rates of depression and anxiety relative to men, and a variety of biopsychosocial factors have been proposed to explain these differences (Romans & Ross, Citation2010). For example, Hyde, Mezulis, and Abramson (Citation2008) have proposed the ABC (affective, biological, cognitive) model to articulate the complex interrelationships that likely underlie these differences. The disproportionate number of bisexual women, relative to bisexual men, in many research samples may therefore be an important contributor to findings of higher rates of mental health problems in studies where these gender/sex differences have not been adjusted in analyses. However, the limited gender/sex-stratified data we could identify for this meta-analysis found that even among samples limited to women the highest rates of depression and anxiety were often in the bisexual group (e.g., Alexander, Volpe, Abboud, & Campbell, Citation2016; Katz-Wise et al., Citation2015; Lehavot & Simoni, Citation2011). Indeed, when the gender/sex-stratified data available for analysis were pooled, effect estimates were consistently higher for comparisons of bisexual women to lesbians, than for bisexual men compared to gay men (data previously presented). Taken together, these data suggest that bisexuality and gender/sex intersect in important ways to produce mental health vulnerabilities among women.

Although the factors that contribute to this particular vulnerability cannot be clearly determined on the basis of the existing literature, qualitative and theoretical writing indicates that bisexuality as an identity category is socially constructed differently for women as compared to men (Rust, Citation2000a). For example, common beliefs about bisexuals as hypersexual may in some ways position bisexual women as more “deviant” than bisexual men, in the context of social norms that discourage women’s and promote men’s sexual activity, respectively (Lefkowitz, Shearer, Gillen, & Espinosa-Hernandez, Citation2014). That is, in a context where women’s sexuality is broadly suppressed, positioning a specific group of women (in this case, bisexuals) as hypersexual may have particularly negative consequences for them relative to men, whose sexuality is not policed in the same way. Indeed, there is some evidence that stereotypes about bisexual women as hypersexual may be associated with sexual violence among young bisexual women, in that young bisexual women have described contexts in which their consent was (inaccurately) presumed solely on the basis of their bisexual identity (Flanders, Ross, Dobinson, & Logie, Citation2017). Monosexist beliefs about bisexuals as hypersexual may therefore contribute to the high rates of sexual violence among bisexual women relative to individuals of other sexual orientation groups (Alexander et al., Citation2016; Drabble, Trocki, Hughes, Korcha, & Lown, Citation2013; Walters, Chen, & Breiding, Citation2013), and in turn, contribute to rates of poor mental health (Morris & Balsam, Citation2003).

Although the studies available for our analysis did not provide sufficient data for us to stratify by gender (that is, differentiating between bisexual transgender and cisgender participants), it is notable that many bisexual people identify their gender within the transgender umbrella. For example, in our own research, approximately 25% of our sample of bisexual people in Ontario identified with a transgender or nonbinary gender identity label (Bauer, Flanders, MacLeod, & Ross, Citation2016). Transgender people experience very high rates of depression and other mental health outcomes associated with transphobic discrimination (Rotondi, Bauer, Scanlon, et al., Citation2011a; Rotondi, Bauer, Travers, et al., Citation2011b). Further, stereotypes that position bisexuality as a “confused” or unstable identity may be particularly problematic for transgender people who require access to gender-affirming medical care through gatekeepers in the psychiatric system (Ross et al., Citation2010). More research is needed to better understand the relationship between bisexual identity, gender/sex, and mental health.

With respect to socioeconomic status, available data indicate that bisexual people tend to be more economically vulnerable across a range of indicators of socioeconomic status, including measures of income, employment, and education (e.g., Gorman et al., Citation2015; Tjepkema, Citation2008). These differences may be very important in understanding health disparities associated with bisexuality; indeed, Gorman and colleagues’ (Citation2015) analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data illustrated that adjusting for socioeconomic differences substantially attenuated differences in self-reports of poor physical health among bisexuals, heterosexuals, and gay/lesbian respondents. To our knowledge, analogous analyses have not been conducted to investigate the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage on mental health among bisexual people, and little research has explored the experience of poverty among bisexual people. Our team has conducted a mixed methods analysis of this topic and identified four potential pathways through which bisexuality and poverty may intersect to impact mental health; intersections of social stigmatization associated with both bisexuality and poverty were central to these pathways (Ross et al., Citation2016).

We could identify very few studies that specifically investigated the intersection of bisexual and racialized identities in relation to mental health. However, research and writing examining this intersection more generally describes unique experiences for bisexual Indigenous (Robinson, Citation2017), Black (Dodge, Jeffries, & Sandfort, Citation2008), and mixed-race (Dworkin, Citation2008) people, among others (Collins, Citation2004). Many of these experiences could have important implications for mental health. For example, some people may experience challenges in the process of identity development when attempting to integrate two highly stigmatized identities (Collins, Citation2004). Further, some bisexual people of color have described experiencing particular challenges with sexual orientation disclosure and affirmation in the context of racial and cultural communities that they experience as or anticipate will be biphobic and/or heterosexist (Flanders et al., Citation2015; Ross et al., Citation2010). More attention to the specific experiences of bisexual people of color is therefore necessary in this field.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis revealed that, for both depression and anxiety, measured in a variety of ways, bisexual people experience higher rates of poor outcomes relative to heterosexual people, and also experience as high or higher rates of poor outcomes relative to gay and lesbian people. In our narrative review, we identified three key potential contributors to these mental health disparities: sexual orientation–based discrimination; bisexual invisibility and erasure; and lack of bisexual-affirmative support.

The findings of our meta-analysis are consistent with other meta-analytic studies that report findings specific to bisexual people (Plöderl & Tremblay, Citation2015; Semlyen et al., Citation2016), as well as a recent narrative review on bisexual mental health (Feinstein & Dyar, Citation2017), in their indication that bisexual people are at elevated risk for poor mental health. We extend upon these existing data by reporting separate pooled-effect estimates for bisexual people in comparison to both gay/lesbian and heterosexual comparison groups. Doing so across a variety of depression and anxiety outcomes enables us to clearly establish that bisexual people experience at least the same level of mental health disparity relative to heterosexuals as do our gay/lesbian counterparts, and in many cases, demonstrate a small but statistically significant elevation in rates of poor outcomes relative to lesbian and gay people as well.

In our opinion, one of the most important findings of this review is the relative lack of literature that explicitly addresses bisexual mental health. It is disheartening that more than 500 articles had to be rejected at the full-text review stage because they did not report data separately for bisexual participants, and we were particularly disappointed to see that this is still a common practice even among recently published papers. This is despite high-profile recognition that bisexual people have been understudied relative to gays and lesbians (e.g., Institute of Medicine, Citation2011) and research reports and guidance documents recommending that data from bisexual participants be disaggregated from those of other sexual minority participants (Badgett & Goldberg, Citation2009; Barker et al., Citation2012; Bauer & Jairam, Citation2008).