Abstract

The relations between self-reported aspects of gender identity and sexuality were studied in an online sample of cisgender (n = 4,954), transgender (n = 406), and gender-diverse (n = 744) groups. Aspects of gender identity and sexual fantasies, attraction, behavior, and romantic relations were assessed using the Multi-gender Identity Questionnaire (Multi-GIQ) and a sexuality questionnaire. Results show a wide spectrum of gender experiences and sexual attractions within each group, an overlap among the groups, and very weak relations between atypical gender identity and atypical sexuality. At the group level, aspects of gender identity and sexuality were mainly predicted by gender and sex-gender configuration, with little contribution of sex assigned at birth. A principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that measures of gender identity and of sexuality were independent, the structure of sexuality was mostly related to gender, whereas the structure of gender identity was mostly related to sex-gender configuration. The results of both approaches suggest that measures of gender identity could roughly be divided into three classes: one including feeling as a man and feeling as a woman; a second including measures of nonbinary and “trans” feelings; and a third including feeling as a “real” woman and feeling as a “real” man. Our study adds to current scientific data that challenge dichotomous conventions within gender identity and sexuality research. Possible social and clinical implications are discussed.

The idea that biological sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation are directly linked has long prevailed in scientific research (for review, see Rees-Turyn, Doyle, Holland, & Root, Citation2008). According to this view, each of two biological sexes (male/female) is associated with a typical, coherent gender identity (boy/man, girl/woman) and sexual attraction toward the “other”Footnote1 sex (Diamond & Butterworth, Citation2008; Richardson, Citation2007). Relatedly, it is often assumed that atypical development of one construct (biological sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation) leads to atypical development of the other constructs (for a critical review of this assumption, see Jordan-Young & Rumiati, Citation2012; Ponse, Citation1978; Richardson, Citation2007).

The existence and experiences of bisexual individuals and individuals with nonbinary gender identities challenge the binary conceptualization of sexual orientation and gender identity, respectively. Indeed, studies of sexual orientation have revealed that it is a multidimensional construct (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, Citation2012) that is better defined as a spectrum rather than categorically (reviewed in Savin-Williams, Citation2016). Similarly, narratives of transgender individuals (i.e., individuals whose self-labeling is different from their birth-assigned category) reveal that while some may identify with the “other” biological sex unequivocally (Bockting & Coleman, Citation2007; Girchick, Citation2008; Wilson, Citation2002), others may embrace identities that reject the gender binary by incorporating both male and female identifications, by fostering gender ambiguity, by alternating between different gender identities, or by rejecting gender identity altogether (Diamond, Pardo, & Butterworth, Citation2011; Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017; Richards et al., Citation2016). This is also true for individuals who self-identify as genderqueer, gender diverse, or by other nonbinary gender identity labels (here we refer to these individuals collectively as “gender diverse”) (Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017).

In two recent studies we have shown that gender identities that transcend the either/or (i.e., either a man or a woman) conceptualization are also present among cisgender individuals (i.e., individuals whose self-labeling is the same as their birth-assigned category). Using the Multi-gender Identity Questionnaire (Multi-GIQ; Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel, Tarrasch, Berman, Mukamel, & Ziv, Citation2013) we found that cisgender participants presented a range of gender identity experiences with different levels of feeling as the “other” gender, wishing to be the “other” gender, and/or wishing to have the body of the “other” sex (Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013). In other words, feelings and wishes that are usually considered typical of individuals with transgender or nonbinary identity labels were also present in cisgender individuals (for a similar finding in children, see Martin, Andrews, England, Zosuls, & Ruble, Citation2017).

The two studies also challenged the common assumption that an atypical sexuality predicts an atypical gender identity by showing that the observed variability in gender identity in cisgender individuals was only weakly related to sexual attraction and to self-labeled sexual orientation (Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013).

Much less in known about gender identity and sexuality in individuals who do not self-identify as cisgender. Studies of gender identity in transgender individuals mostly focus on the gender experience as the affirmed gender (Bockting & Coleman, Citation2007; Diamond et al., Citation2011). Regarding sexuality, historically, transgender individuals were assumed to be predominantly attracted to the same sex assigned at birth or to both sexes before transitioning, and heterosexual in relation to their felt gender identity after transitioning (Diamond et al., Citation2011). Several studies indeed found an elevated prevalence of same-sex and bisexual attraction in samples of transgender individuals before transitioning compared to cisgender samples (Blanchard, Citation1989; Blanchard, Clemmensen, & Steiner, Citation1987; Cerwenka et al., Citation2014; Lawrence, Citation2010; Nieder et al., Citation2011, Zucker, Lawrence, & Kreukels, Citation2016). Other studies, however, revealed considerable diversity in the sexual desires and identifications of transgender individuals before and after transitioning that parallels the diversity seen in cisgender individuals (Auer, Fuss, Höhne, Stalla, & Sievers, Citation2014; Hines, Citation2007; Kuper, Nussbaum, & Mustanski, Citation2012; Meier, Pardo, Labuski, & Babcock, Citation2013; Rowniak & Chesla, Citation2013). A study of the relations between sexuality and gender identity in a clinical sample of gender-dysphoric male-assigned individuals did not find significant differences between different sexual orientation groups (Deogracias et al., Citation2007).

The aim of the present study was to assess, using an online version of the Multi-GIQ, gender identity, sexuality, and the relations between the two in individuals who self-label as transwoman, transman, or transgender (we will use the term “transgender” when referring to the three groups together); in individuals who self-label as genderqueer or other (we will use the term “gender diverse” when referring to these groups together); and in cisgender individuals (note that data on the group of cisgender individuals included here have been reported in Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018).

The Multi-GIQ (Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013) was developed on the basis of existing questionnaires for the assessment of gender dysphoria in clinical populations, such as the Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults (Deogracias et al., Citation2007; for a description of how the questionnaire was developed, see Joel et al., Citation2013; for the full text of the questionnaire, see the appendix). The Multi-GIQ differs from previous gender identity questionnaires in that it assesses several aspects of gender identity without presupposing that some aspects (e.g., wishing to be the “other” gender, feeling as the “other” gender) are dysphoric or nonconforming. It includes items that assess feeling as a woman, feeling as a man, feeling as both a man and a woman, feeling as neither, perceiving one’s affirmed gender as “real,” contentment with affirmed gender, the wish to be the “other” gender, contentment with one’s sexed body, and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited to complete an Internet questionnaire with special effort to recruit participants from sexual minority groups (“minority” in terms of the prevalence in the population). No means were taken to guarantee random sampling of the population. Invitations were sent to several groups and organizations that concentrate on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues and posted on relevant online forums as well. Invitations were also posted on the Facebook profiles of the researchers. The invitation included an explicit request to forward the invitation to as many people as possible.

Procedure

The questionnaire was administered over the Internet. On the first page participants were informed about the research aims (studying how people perceive their gender identity), were assured that they were allowed to stop filling the questionnaire at any point and that their contribution and responses would be anonymous, and were asked to give their consent to participate in the study. Ways of contacting the researchers were presented. By pressing “Continue” the Multi-GIQ was displayed and was followed by the sexuality and demographic questionnaires. All questions of the Multi-GIQ and sexuality questionnaires were presented one at a time; the questions of the demographic questionnaire were presented simultaneously. Participants could press “Next” without answering a question but could not go back and change their chosen answers.

Measures

The Multi-GIQ includes 24 questions that are either gender neutral (e.g., Q24: “In the past 12 months, have you wished you had the body of the ‘other’ sex?”) or presented twice, once as if meant for a female participant and once as if meant for a male participant (e.g., Q3: “In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a woman?”; Q4: “In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a man?” (Joel et al., Citation2013). Nine variables were analyzed, of which six were scores on single items of the Multi-GIQ and three were created on the basis of theoretical considerations by averaging the scores of two questions (in these cases, Not relevant was treated as a missing value). The nine variables were feeling as a man (Q4, Q13), feeling as a woman (Q3, Q14), feeling as both genders (Q15, Q16), feeling as neither gender (Q17), satisfaction being the affirmed gender (Q2 and Q1 for men and women, respectively), wishing to be the “other” gender (Q21 and Q20 for men and women, respectively), dislike of the sexed body (Q23 and Q22 for male- and female-assigned participants, respectively), wishing to have the body of the “other” sex (Q24), and feeling the affirmed gender is “real” (Q10 and Q9 for men and women, respectively). Questions Q11 and Q12, which pertain to buying and wearing clothes of the “other” sex, were excluded because it was not clear how the term sex was understood by trans and gender-diverse individuals. Four items that were used in Joel et al’s (Citation2013) study to measure “gender as performance” (i.e., perceiving one’s assigned gender as performative) were not included in the final analysis because of low reliability (α = .02 and .49 for “woman as performance” and “man as performance,” respectively). Similarly, items Q18 and Q19 (“… have you felt that it is/it would be better for you to live as a woman/man than as a man/woman?”), which were included in Joel et al. (Citation2013) in the satisfied being a man/woman variables, were not used in the present analysis because of low correlations (r = .15 and .26 for men and women, respectively) with the items that directly tested them (“… have you felt satisfied being a woman/man?”). In addition to the nine variables that assess different aspects of gender identity, we created a tenth variable that assesses the degree to which a participant’s response pattern deviates from the response pattern expected of a participant with a “binary” (i.e., either a man or a woman) gender identity. For example, a man with a binary perception of gender may be expected to always feel as a man and never feel as a woman, both genders, in-between genders, and neither gender. This variable ranged from 0 (Completely binary) to 4 (Highly nonbinary; to obtain this score one had to have the same score on feeling as a man and feeling as a woman, as well as the maximal score on feeling as both genders, in-between genders, and neither gender).

The sexual orientation questionnaire includes eight questions relating to sexual fantasies, sexual attraction, sexual behavior, and romantic relationships. Each question was repeated twice, relating once to women and once to men (e.g., “How would you rate the level of your sexual attraction to men?” and “How would you rate the level of your sexual attraction to women?”). For the attraction questions, the response options were Very high, High, Medium, Low, Very low, None. For the other questions the response options were Very often, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Very rarely, Never. The items from this questionnaire were used in the following manner: All eight items were used in the principal component analysis (PCA). Only attraction to women and attraction to men were used to assess sexuality in the six groups, because only the response options for these items allow independence between attraction to men and attraction to women. Last, to control for possible effects of sexual orientation on gender identity, we used a score created by subtracting the score on attraction to women from the score on attraction to men as a covariate in the analyses of the different aspects of gender identity. (For all analyses including the covariate, see Online Table S4.) This score ranges between strong and exclusive attraction to men (+5), through similar attraction to men and women (between +1 and −1), to strong and exclusive attraction to women (−5).

In addition to filling in the sexual orientation questionnaire, participants were asked to mark a sexual orientation category with which they identify (Exclusively heterosexual, Mostly heterosexual, Bisexual, Mostly homosexual, Exclusively homosexual, Pansexual, Asexual or Other). We did not use these data because some trans and gender-diverse individuals categorized themselves based on their sex at birth while others related to their current gender.

The demographic questionnaire included items concerning sex at birth (Male, Female, Intersex), rearing gender (boy, girl) and adult gender (Man, Woman, Transman, Transwoman, Transgender, Genderqueer, and Other), age, place of origin, residency (Urban, Suburban, Rural), education, and religion. In addition, feminist and queer attitudes were assessed, each by a single item (“Do you hold feminist/queer views?”).

Data Analysis

To analyze the data we used three types of independent variables: sex assigned at birth: female assigned or male assigned (intersex-identified individuals were not included in the current study and will be reported separately); gender: men, women, or gender diverse (e.g., the value women includes ciswomen and transwomen); and sex-gender configuration: cis, trans, or gender diverse. Note that the difference between the variables gender and sex-gender configuration are in the grouping of the cis and trans groups: The cismen and ciswomen groups are grouped together and the transmen and transwomen groups are grouped together under the sex-gender configuration variable, whereas the cismen and the transmen are grouped together and the ciswomen and the transwomen are grouped together under the gender variable.

To test whether the groups differed in the demographic variables, we used analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for interval variables (age), Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables (education, degree of religiosity), and chi-square test followed by a standardized residuals analysis for nominal variables (current living area, childhood living area). We treated as significant standardized residuals that were larger than 2 or smaller than −2 (Sharpe, Citation2015). The measures obtained from the gender identity and sexuality questionnaires were analyzed using two-factor ANOVAs, with the main factors being sex assigned at birth and gender or sex assigned at birth and sex-gender configuration, depending on the specific variable analyzed.

Due to the fact that analyses of large-scale data might produce significant results for small between-groups differences, Cohen’s d was also calculated. All Cohen’s ds are reported in absolute value. Effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, Citation1992). In calculating Cohen’s d we weighted the variances according to the proportion of each sex-gender configuration group in the Sexual Health in Flanders survey (Van Caenegem et al., Citation2015). Of the few studies focusing on nonbinary individuals as well as cisgender and transgender individuals, this study is the most recent and is based on two population-based studies (Richards et al., Citation2016). We have also adopted Cohen’s (Citation1992) criterion for interpreting the size of significant correlations, treating correlations of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 as small, medium, and large, respectively.

Finally, to examine the relations between the different aspects of gender identity and sexuality in each of the sex-gender configurations, we conducted a PCA with a varimax rotation on the items from the Multi-GIQ and the sexual orientation questionnaire. We omitted variables for which the highest loading was under 0.4 or for which the difference between the highest and lowest absolute loadings was under 0.1.

Results

Demographics

Table S1 shows the distribution of participants according to sex assigned at birth and current gender. Table S2 shows chi-square analyses of current and childhood living area, and Table S3 shows ANOVA and Mann-Whitney U test analyses of age, religiosity, and education levels. There were several differences, mostly small, between some of the six sex-gender configuration groups.

The 8,021 cisgender, transgender, and gender-diverse individuals who responded to the questionnaire were from 105 countries, of which half had fewer than five participants. Because the largest samples came from countries in which English is the native language (United States, United Kingdom, and Canada), we included only 6,113 participants from countries in which English is the native language. Of these, we excluded six cisgender (out of 4,960) and three transgender (out of 409) individuals who scored 0 on feeling as the affirmed gender and above 0 on feeling as the “other” gender (e.g., a cisgender man who felt only as a woman and not at all as a man). The final analysis included 6,104 participants (United States, 70.2%; United Kingdom, 14.1%; Canada, 10.7%; Australia, 3.0%; Ireland, 0.8%; New Zealand, 0.9%; South Africa, 0.3%).

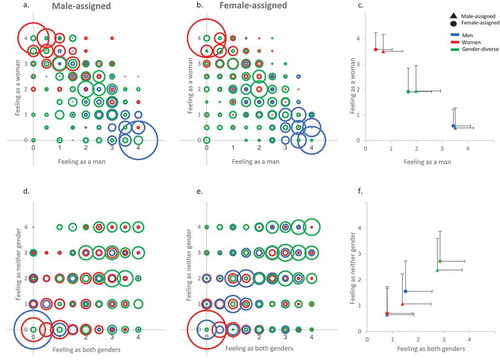

Feeling As a Man, Feeling As a Woman, Feeling As Both Genders and Feeling As Neither Gender

and present feeling as a man (x-axis) and feeling as a woman (y-axis) in male-assigned () and female-assigned () participants who currently self-identify as man (cis or trans, in blue), woman (cis or trans, in red), or otherwise (what we refer to here as gender diverse, in green). presents the means and standard deviations of the six groups. The perception of gender identity was highly variable within each group and overlapping among the different groups, including some overlap between the cisgender women and men groups. The results of a gender × sex assigned at birth ANOVA for each of the variables () revealed that, regardless of the sex assigned at birth, men felt more as a man than women did (for the size of the differences, see ) and the gender-diverse group was in between the men and women groups. Similarly, the women group felt more as a woman than the men group did, and the gender-diverse group was in between. Sex assigned at birth was weakly related at the group level to feeling as a man in the women and gender-diverse groups (the male-assigned group scored higher than the corresponding female-assigned group) but not in the men’s group; nor was it related to feeling as a woman in any of the groups (all ps > 0.65).

Table 1. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for the Multi-Gender Identity Questionnaire Variables

Table 2. Cohen’s d for Significant Comparisons Between Gender and Sex-Gender Configuration Categories

Figure 1. (a–b) Scatter plots and (c) mean and standard deviation of feeling as a man (x-axis) and feeling as a woman (y-axis) in the three gender groups (marked in different colors) in male-assigned (a), female-assigned (b), and all (c) participants. (d–e) Scatter plots and (f) mean and standard deviation of feeling as both genders (x-axis) and feeling as neither gender (y-axis) in the three gender groups in male-assigned (d), female-assigned (e), and all (f) participants. The size of each circle is proportional to the percent of individuals from a given gender category with an identical score on the two measures.

and present feeling as both genders (x-axis) and feeling as neither gender (y-axis) in male-assigned () and female-assigned participants () who currently self-identify as man (cis or trans, in blue), woman (cis or trans, in red), or gender diverse (in green). presents the means and standard deviations of the different groups. Feeling as both genders and feeling as neither gender showed a large within-group variability and between-groups overlap in participants’ responses on these two measures. The results of a sex-gender configuration × sex assigned at birth ANOVA for each of the variables () showed that average levels of feeling as both genders were solely determined by the sex-gender configuration so that the gender-diverse group felt, on average, as both genders more than the cisgender group, and the transgender group was in between the cisgender and gender-diverse groups (). Average levels of feeling as neither gender were mainly determined by the sex-gender configuration with a small contribution (in terms of effect size; see ) of sex assigned at birth. Thus, on average, the gender-diverse group felt as neither gender more than the cisgender group, and the transgender group was in between the cisgender and gender-diverse groups. In addition, in the gender-diverse and transgender groups, female-assigned individuals felt on average more as neither gender compared with male-assigned individuals.

Deviation From a “Binary” Gender Experience

presents deviation from a binary gender experience in the six groups. In all groups, scores were highly variable, occupying the entire range of binary to nonbinary possibilities. The three sex-gender configuration groups showed different patterns of variability, with the gender-diverse group having almost no participant with a totally binary score, whereas this was the most frequent score in the cisgender and transgender groups. The cisgender and transgender groups were very similar, except that the proportion of binary individuals was lower in the two transgender groups compared with the two cisgender groups (χ2 = 99.41, p < .001).

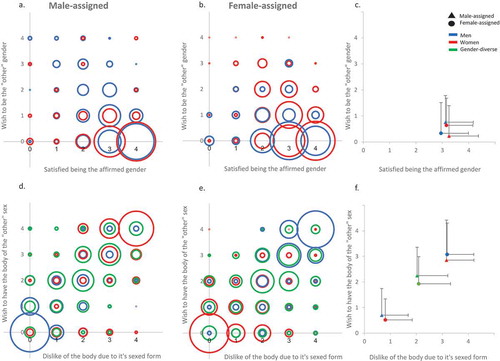

Satisfaction With One’s Affirmed Gender and the Wish to Be the “Other” Gender

Because the only response options in the relevant questions were “man” or “woman,” the gender-diverse group was not included in this analysis. and present satisfaction with one’s affirmed gender and wish to be the “other” gender, respectively, in participants who were male assigned () or female assigned at birth () and who currently self-identify as man (cis or trans, in blue) or woman (cis or trans, in red). presents means and standard deviation of the four groups. Levels of satisfaction with the affirmed gender and the wish to be the “other” gender were highly variable within groups and highly overlapping between groups. The results of a sex-gender configuration × sex assigned at birth ANOVA for each of the variables () showed that the mean levels of satisfaction with one’s affirmed gender were high and were similar in the four groups, except for a small difference between transwomen and transmen (). Mean levels of wish to be the “other” gender were low and were determined solely by sex-gender configuration ( and ) so that the cisgender group wished to be the “other” gender more than the transgender group (d = 0.62).

Figure 3. (a–b) Scatter plots and (c) mean and standard deviation of satisfied being the affirmed gender (x-axis) and wish to be the “other” gender (y-axis) in the three gender groups (marked in different colors) in male-assigned (a), female-assigned (b), and all (c) participants. (d–e) Scatter plots and (f) mean and standard deviation of dislike of the body due to its sexed form (x-axis) and wish to have the body of the “other” sex (y-axis) in the three gender groups in male-assigned (d), female-assigned (e), and all (f) participants. The size of each circle is proportional to the percent of individuals from a given gender category with an identical score on the two measures.

Dislike of One’s Sexed Body and the Wish to Have the Body of the “Other” Sex

and present dislike of one’s sexed body and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex in participants who were male assigned () or female assigned at birth () and who currently self-identify as man (cis or trans, in blue), woman (cis or trans, in red), or gender diverse (in green). presents means and standard deviations of the six groups. As with the previous variables, dislike of one’s sexed body and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex showed considerable variance within groups and overlap between groups. The results of a sex-gender configuration × sex assigned at birth ANOVA for each of the variables () showed that, at the group level, both measures were determined by the sex-gender configuration, with a small contribution of the sex assigned at birth to the wish to have the body of the “other” sex (). As a group, the transgender participants scored higher on dislike of one’s sexed body than the cisgender group, and the gender-diverse group was in between; the transgender group wished to have the body of the “other” sex more than the cisgender group, and the gender-diverse group was in between. In addition, there was a small difference within the cisgender and gender-diverse groups, such that male-assigned participants wished to have the body of the “other” sex more than female-assigned participants. The difference (in the opposite direction) between the transgender men and women groups was not significant (p = 0.20).

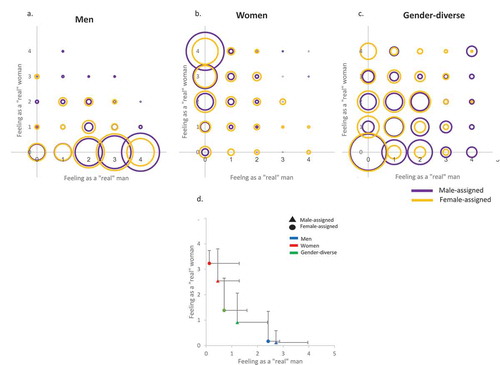

Feeling As a “Real” Man and Feeling As a “Real” Woman

through present feeling as a “real” man (x-axis) and feeling as a “real” woman (y-axis) in participants who currently identify as man (cis or trans, ), woman (cis or trans, ), or gender diverse (). Participants are divided according to the sex assigned at birth as male (purple) or female (orange). presents means and standard deviations of the six groups. As can be seen, feeling as a “real” man or woman was highly diverse within groups and highly overlapping among groups. The results of a gender × sex assigned at birth ANOVA for each of the variables () showed that mean levels of the two variables were mainly determined by gender: In women, the average feeling as a “real” woman was high and the average feeling as a “real” man was low; the reverse was true for men. The average score on the two variables was intermediate in the gender-diverse group (). In addition, there were small- to medium-sized differences within each gender group. Thus, groups of male-assigned participants felt more as a “real” man compared to the same gender group of female-assigned participants. Similarly, the cisgender women group felt more as a “real” woman compared to the transgender women group, and the female-assigned gender-diverse group felt more as a “real” woman compared to the male-assigned gender-diverse group. The cisgender and transgender men groups did not significantly differ on this measure (p = 0.98).

Figure 4. (a–c) Scatter plots and (d) mean and standard deviation of feeling as a “real” man (x-axis) and feeling as a “real” woman (y-axis) in the three gender groups in male-assigned and female-assigned participants (marked in different colors). The size of each circle is proportional to the percent of individuals from a given gender category with an identical score on the two measures.

Attraction to Women and Men

Figures S1a and S1b present attraction to men (x-axis) and attraction to women (y-axis) in male-assigned (Online Figure S1a) or female-assigned (Online Figure S1b) participants who currently identify as man (cis or trans, in blue), woman (cis or trans, in red), or gender diverse (in green). Attraction to men and attraction to women were highly variable within groups and widely overlapping between groups. Over the entire sample, the two measures showed a large negative correlation (r = −.53, p < .001), but the size of the correlation varied widely between groups, being highest in the cisgender men group (r = −.78, p < .001) and lowest in the female-assigned gender-diverse group (r = −.06, p = .18). The correlation between attraction to men and attraction to women in the cisgender women, transgender men, transgender women, and male-assigned gender-diverse groups was similar (i.e., not significantly different) and in between the correlation in the cisgender men and female-assigned gender-diverse groups (r = −.43, r = −.47, r = −.35, and r = −.31, respectively, all ps < .001).

Deviation From a Heterosexual Sexual Attraction and Deviation From a “Binary” Gender Experience

To assess the assumed relations between deviations from a binary gender experience and from a heterosexual sexuality, we calculated the correlations between the nonbinary score and the attraction to men-women score, which was recalculated by subtracting attraction to the “other” gender from attraction to my gender (“my” and “other” gender were determined according to one’s self-identified current gender identity for the cisgender and transgender groups, and according to sex assigned at birth for the gender-diverse groups). The correlation was medium (r = .25, p < .001) over the entire sample, and trivial (r < 0.1) and nonsignificant in each of the groups, except for the cisgender women group, in which the correlation was medium (r = .25, p < .001).

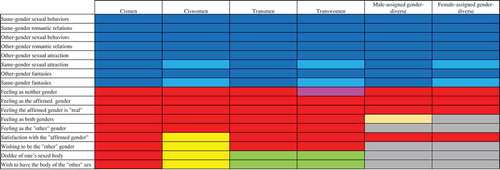

Relations Between Gender Identity and Sexuality

shows the components derived from the PCA of the gender identity and sexuality variables in each of the cisgender, transgender, and gender-diverse groups (See Online Table S5 for the complete component loadings from the PCA). Parallel components are colored identically. Overall, variables related to sexuality loaded on components separate from those related to gender identity, and the structure of gender identity and sexuality depended on both gender and sex-gender configuration. More specifically, in the cisgender men, transgender men, and male-assigned gender-diverse groups, all the sexuality items loaded on a single component, whereas in the cisgender women, transgender women, and female-assigned gender-diverse groups, these measures loaded on two components. One component included same-gender fantasies and same-gender attraction, and the second component included same-gender sexual behaviors and romantic relations as well as “other”-gender sexual behaviors, romantic relations, sexual attraction, and fantasies.

Figure 5. A comparison of a principal component analysis of all the variables from the Multi-GIQ and sexuality questionnaires in the six sex-gender configuration groups. Parallel components are marked in an identical color.

The structure of gender identity was very similar in the two transgender groups, which were the only ones to have a body dysphoria component, which included dislike of one’s sexed body and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex. All other items (feeling as the affirmed gender, feeling the affirmed gender is “real,” feeling as the “other” gender, feeling as both genders, satisfaction with the affirmed-gender, and wishing to be the “other” gender) loaded on a single component, with the exception of feeling as neither gender, which did not load on any component in the transwomen group. The structure of gender identity was also very similar in the two gender-diverse groups, in which one component included the body dysphoria items together with measures related to nonbinary feelings (i.e., feeling as the “other” gender, wishing to be the “other” gender, and feeling as both genders; the latter did not load on any component in the male-assigned gender-diverse group), and the other component included mainly measures related to feeling as the gender that matches one’s sex assigned at birth (feeling as the affirmed gender, feeling the affirmed gender is “real,” satisfaction with the affirmed gender, and feeling as neither gender). Interestingly, satisfied being my gender loaded on this latter component. This is in contrast to the cisgender women group, in which this item was grouped with wish to be the “other” gender, dislike of one’s sexed body, and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex, in a component that may be termed “gender dysphoria.” In cisgender women, all other items (feeling as the affirmed gender, feeling the affirmed gender is “real,’ feeling as the “other” gender, feeling as both genders, and feeling as neither gender) loaded on a second component. The cisgender men group differed from the cisgender women group in having only one component of gender identity. Interestingly, apart from the body dysphoria component, the structure of gender identity in the cisgender men group was very similar to that in the two transgender groups. The similarity between the cisgender men and transgender men groups becomes even more striking when sexuality is also considered. In both groups, all the gender-identity-related variables (except the two body dysphoria items) loaded on one component, and all the sexuality variables loaded on another component.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that individuals who self-label as cisgender, transgender, or gender diverse report a wide range of gender identity-related experiences and of combinations of sexual attraction to women and men; in all groups, gender identity and sexuality are only weakly correlated; and atypical gender identity is only weakly related to atypical sexuality.

Before further describing and discussing the results, we would like to state the strengths and limitations of our study. The present study is one of very few quantitative studies of gender identity and sexuality of gender-diverse individuals (Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017) and includes a much larger sample of gender-diverse and transgender individuals compared to previous studies (for a critical review of past studies, see Mueller, De Cuypere, & T’Sjoen, Citation2017). In addition, because the present study was not conducted in a clinical setting, it may have recruited transgender individuals with a broader spectrum of gender experiences. However, the use of a convenience sample and the fact that no means were taken to achieve random sampling make it unrepresentative of the general population in countries where English is a formal language. In fact, the present study includes an overrepresentation of individuals from minority groups, such as transgender and nonheterosexual. Even the heterosexual cisgender individuals who responded to our invitation may have been a biased sample of this population, because the invitation revealed the study’s major aims and was published, among others, in LGBT-focused Internet sites. We therefore view our results more as reflecting the range of experiences individuals in the different sex-gender configuration groups may have, and the extent of overlap among these groups, than as providing exact estimates of the proportion of each experience in each of the different groups or of the size of the differences between groups.

On all measures of gender identity and sexuality, scores of individuals from the three sex-gender configuration groups overlapped extensively. In all groups, gender-identity-related feelings ranged from highly binary (i.e., feeling as one gender only) to highly “queer” (i.e., feeling as both genders or as neither), and from highly cis-like (i.e., satisfaction with one’s gender and body) to highly trans-like (i.e., wishing to be the “other” gender or have the body of the “other” sex). Sexual attraction was similarly characterized by a wide range of combinations of attraction to women and to men, from attraction to only one gender, to both genders, or to none. These findings replicate results from previous studies conducted on cisgender (Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013) and gender-diverse individuals (Joel et al., Citation2013) and extend them to transgender individuals.

In line with our previous findings of weak relations between measures of sexuality and measures of gender identity in cisgender individuals, here we found that, in all groups, measures of gender identity and of sexuality loaded on different components. In addition, deviation from a binary gender identity was only weakly related to deviation from heterosexual sexuality. These findings are in line with the conceptualization of gender identity and sexuality as distinct constructs (Burman, Citation2005; Connell, Citation1985; Diamond & Butterworth, Citation2008; Jackson, Citation2006; Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013; Morgan, Citation2013; Shively & DeCecco, Citation1977; Striepe & Tolman, Citation2003; Vanwesenbeeck, Citation2009) but out of line with the assumption that atypical development of one of these constructs leads to atypical development of the other construct (critically reviewed in Jordan-Young & Rumiati, Citation2012; Ponse, Citation1978; Richardson, Citation2007).

Because gender identity and its relation to sexuality in the cisgender individuals included in the present study were described in Jacobson and Joel (Citation2018), here we focus on similarities and differences between the cisgender (men and women), transgender (men and women), and gender-diverse (male-assigned and female-assigned) groups. In general, the present study demonstrates similarities between same-gender groups (e.g., cisgender and transgender women) on some measures and between same sex-gender configuration groups (e.g., transgender men and transgender women) on other measures, but not between same sex assigned at birth groups (e.g., cisgender women and transgender men). This is clearly evident in the structure of gender identity and sexuality as revealed by the results of PCA. Similarities were found between the two transgender groups and between the two gender-diverse groups (in the structure of gender identity) and between the transmen and cismen groups (in the structure of gender identity and sexuality). Although the cisgender women and female-assigned gender-diverse groups had the same structure of sexuality, suggesting similarity between same sex at birth groups, this structure of sexuality was also shared by the transgender women group. This sexuality structure was different from that observed in the cisgender men, transgender men, and male-assigned gender-diverse groups. The observation that the same sexuality structure is seen in groups sharing the same gender but different sex assigned at birth refutes the possibility that sex at birth determines the structure of sexuality. This is of interest given recent evolutionary-based explanations for differences between ciswomen and cismen in sexual attraction (e.g., that women’s sexuality is more flexible than men’s; Kuhle & Radtke, Citation2013), as it suggests that these differences reflect gender, that is, the social construction of sex, rather than sex itself. Although clearly the current self-labeling of female and male gender-diverse individuals is not “woman” and “man,” it is possible that many of them were, and still are, treated as women and men, and that this leads, in turn, to the structure of their sexuality being similar to that of ciswomen and transwomen, and of cismen and transmen, respectively.

The results of the PCA and of the comparisons between groups on single measures of gender identity suggest that these measures could roughly be divided into three classes. One class includes feeling as a man and feeling as a woman. On these measures, the average score of each group was mainly determined by gender (i.e., man, woman, gender diverse). The finding of similar average scores of the cisgender and transgender groups on these measures is in line with previous reports of similar gender-identity-related cognitions in transgender and cisgender individuals (Olson, Key, & Eaton, Citation2015).

The second class includes measures of nonbinary feelings (feeling as both genders, feeling as neither gender), and trans feelings (wish to be the “other” gender, dislike of one’s sexed body, and the wish to have the body of the “other” sex). At the group level, these measures were mainly determined by sex-gender configuration (i.e., cis, trans, gender diverse), with little or no effect of gender or sex assigned at birth. The only exception was feeling as neither gender, for which the mean score was higher for female-assigned participants compared to male-assigned participants in the gender-diverse and transgender groups. One possible explanation for this difference may be the earlier and more strict gender socialization of boys compared to girls (Gilligan, Citation1982, Citation2011), which may result in more girls than boys feeling as neither gender (that is, in addition to not feeling as a boy, they also do not strongly feel as a girl). In line with this possibility, Martin et al. (Citation2017) found that 60.3% of the six- to 11-year-old children in their study who reported relatively low similarity to both genders were girls.

As may be expected, at the group level, nonbinary feelings were high in the gender-diverse groups and low in the cisgender groups. These feelings were also low in the transgender groups, although higher than in the cisgender groups. These observations were supported by inspection of the scatterplots of the nonbinary score, which revealed that transgender individuals were more evenly distributed on this measure compared to the cisgender and gender-diverse groups, the distributions of which were skewed toward the binary and nonbinary ends of this measure, respectively. Our finding that transgender individuals vary in their degree of binary experience more than cisgender individuals is in line with a wide body of literature stressing the diversity and complexity of gender experience within the transgender community (Bockting & Coleman, Citation2007; Diamond et al., Citation2011; Girchick, Citation2008; Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017; Richards et al., Citation2016; Wilson, Citation2002). Our present and previous studies (Jacobson & Joel, Citation2018; Joel et al., Citation2013) add to existing literature the observation that similar complexity may be found in cisgender individuals.

For the two body dysphoria items, the two transgender groups had the highest average scores, the two cisgender groups had the lowest average scores, and the two gender-diverse groups were in between. In addition, in both trans groups, the two body dysphoria items loaded on one component, whereas all other measures of gender identity loaded on a different component (except for feeling as neither gender in the transwomen group). The similar structure of gender identity may suggest similar identity formation processes in transmen and transwomen. Furthermore, that the two body dysphoria items loaded on a separate component suggests that body dysphoria in transgender individuals is not necessarily inherent to their felt gender identity. This possibility is consistent with evidence that many transgender individuals do not simply feel “trapped in the wrong body” (Diamond et al., Citation2011) and the claim that body modifications may sometimes serve the social expectation that one’s psychological experience of gender be aligned with the physical appearance of one’s body, rather than an inherent need of the transgender individual for such an alignment (Siebler, Citation2012).

The three trans feelings (i.e., the two body dysphoria items and the wish to be the “other” gender) were related in the gender-diverse groups with feeling as the “other” gender and feeling as both genders (not in the male-assigned group). This finding may reflect a perception of the sexed body as limiting gender expression, whether by its physical characteristics or through the societal limitations imposed on it (Butler, Citation1990). Such a perception may also account for the relatively high body dysphoria feelings in the gender-diverse groups compared with the cisgender groups, and is in line with reports that some gender-diverse individuals may wish to align their appearance with their gender experience (Matsuno & Budge, Citation2017).

In the ciswomen group, the three trans feelings were linked with satisfaction with the affirmed gender. In all other groups, satisfaction with affirmed gender was linked to feeling as the affirmed gender (and to other aspects of gender identity, which differed between the different groups). The association between (dis)satisfaction with affirmed gender and body dysphoria in cisgender women may reflect the multiple ways in which the social reaction to the female body may cause dissatisfaction or suffering to women in Western societies (Fredrickson & Roberts, Citation1997; Kahalon, Shnabel, & Becker, Citation2018)—from policing its form, which may lead to the development of body image issues and eating disorders (Calogero, Davis, & Thompson, Citation2005), to sexual victimization (White, Donat, & Bondurant, Citation2001; for a review, see Szymanski, Moffitt, & Carr, Citation2011).

The third class of gender identity measures includes two: feeling as a “real” woman and feeling as a “real” man. At the group level, these measures were determined by both gender and sex assigned at birth, so that within each gender group (man, woman, gender diverse), feeling as a “real” man was higher in male-assigned participants compared to female-assigned participants, and feeling as a “real” woman was higher in female-assigned participants compared to male-assigned participants (except for the men group, in which male- and female-assigned participants scored similarly). While the differences between the different gender groups are self-explanatory, the differences within each gender group according to sex assigned at birth most probably reflect the normative association between sex and gender, which may be influencing feeling as a “real” man and a “real” woman also in the transgender and gender-diverse groups.

Comparison between average levels of attraction to women and to men in the six groups seems meaningless, because these clearly depend on the composition of each group in terms of sexual orientation, which differed among groups. Comparing the six gender groups in terms of the correlations between attraction to women and attraction to men may, however, be of interest. These correlations were very high in the cisgender men group, negligible in the female-assigned gender-diverse group, and medium in the remaining four groups. The high correlation in the cisgender men group may be interpreted as reflecting a more rigid sexuality in this group (Bailey et al., Citation2016; Diamond, Citation2000, Citation2003; Diamond & Butterworth, Citation2008), which may be related to the unique ways in which sexuality serves to distinguish masculinity from femininity and to construct manhood (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005; Poteat & Anderson, Citation2012) and to the earlier and stricter socialization of boys compared to girls (Gilligan, Citation1982, Citation2011). The negligible correlation in the female-assigned gender-diverse group may reflect the other pole of gender socialization during childhood, combined with current gender identity as gender diverse, which by definition refutes binary definitions of gender and sexuality.

The different role sexuality plays in gender socialization in men and women may also underlie the separation between same-gender sexual attraction and fantasies from the other sexuality variables in cisgender women, transgender women, and female-assigned gender-diverse groups, but not in the cisgender men, transgender men, and male-assigned gender-diverse groups, where all sexuality items loaded on a single component. Thus, in women (cis and trans) and female-assigned gender diverse individuals, sexual behavior and sexual attraction to one sex may coexist alongside sexual attraction and fantasies toward the second sex, more than in men (cis and trans) and in male-assigned gender-diverse individuals. This finding is in line with literature suggesting greater sexual fluidity in women compared to men (Baumeister, Citation2000; Diamond, Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Peplau & Garnets, Citation2000), although, as explained above, our findings suggest this is a gender difference rather than a sex difference.

Conclusions

The present study adds to a large body of research that questions binary representations of gender and sexuality (for a recent review, see Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & van Anders, Citation2018). Whereas gender-diverse individuals are expected to vary widely in their gender identity and sexuality, the present study highlights that a similar range of experiences is also found among cisgender and transgender individuals. Moreover, the overlapping spectrums of gender identification found in each of the groups suggests that although these groups differ on average on some variables, their gender identities belong on the same grid. This finding is important in countering stigma and prejudice often aimed at gender minority groups (Bockting, Miner, Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, Citation2013).

The high variability in gender identity in the transgender group undermines the common demand from transgender individuals who seek hormonal or surgical interventions to identify solely with one of two genders (Fausto-Sterling, Citation2000). Our study further reveals that in transgender individuals the wish to modify the body, if experienced, may be distinct from other aspects of gender identity. Broadening the norms regarding how gender identities can be expressed and loosening the demand for alignment of gender expression and physical appearance may increase choice regarding body modifications in transgender individuals and decrease stress associated with atypical gender expressions in cisgender, transgender, and gender-diverse individuals.

Last, the fact that deviation from a binary gender identification was only weakly related to deviation from heterosexual sexuality does not support the common assumption that an “atypical” gender identity would entail an “atypical” sexuality, and vice versa (for a critical review, see Jordan-Young & Rumiati, Citation2012; Ponse, Citation1978; Richardson, Citation2007). This fact and the fact that gender identity and sexuality consistently emerged on separate components point to the conclusion that they are mostly independent phenomena and should be conceptualized as such, both clinically and scientifically, although attention should be given to their intersections (Warner & Shields, Citation2013).

Supplemental Table S1

Download MS Word (151.5 KB)Supplemental Figure S1

Download Zip (272.2 KB)Notes

1 We use sex to refer to the birth-assigned category, female or male, and gender to refer to the self-identified social category, usually woman or man. The term “other” sex/gender is used to relate to the other sex or gender between the two options, and the quotation marks are meant to highlight the fact that there are more possible categories than just male and female, or man and woman.

References

- Auer, M. K., Fuss, J., Höhne, N., Stalla, G. K., & Sievers, C. (2014). Transgender transitioning and change of self-reported sexual orientation. PLoS One, 9, 1–11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110016

- Bailey, J. M., Vasey, P. L., Diamond, L. M., Breedlove, S. M., Vilain, E., & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17, 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616

- Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 347–374. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.347

- Blanchard, R. (1989). The classification and labeling of nonhomosexual gender dysphorias. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 18, 315–334.

- Blanchard, R., Clemmensen, L. H., & Steiner, B. W. (1987). Heterosexual and homosexual gender dysphoria. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 16, 139–152.

- Bockting, W. O., & Coleman, E. (2007). Developmental stages of the transgender coming out process: Toward an integrated identity. In R. Ettner, S. Monstrey, & E. Eyler (Eds.), Principles of transgender medicine and surgery (pp. 185–208). New York, NY: The Haworth Press.

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Romine, R. E. S., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 943–951. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

- Burman, E. (2005). Contemporary feminist contributions to debates around gender and sexuality: From identity to performance. Group Analysis, 38, 17–30. doi:10.1177/0533316405049360

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Calogero, R. M., Davis, W. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The role of self-objectification in the experience of women with eating disorders. Sex Roles, 52, 43–50. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-1192-9

- Cerwenka, S., Nieder, T. O., Briken, P., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Cuypere, G. D., Haraldsen, I. R., … Richter-Appelt, H. (2014). Intimate partnerships and sexual health in gender-dysphoric individuals before the start of medical treatment. International Journal of Sexual Health, 26, 52–65. doi:10.1080/19317611.2013.829153

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

- Connell, R. W. (1985). Theorizing gender. Sociology, 19, 260–272. doi:10.1177/0038038585019002008

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639

- Deogracias, J. J., Johnson, L. L., Meyer-Bahlburg, H., Kessler, S. J., Schober, J. M., & Zucker, K. J. (2007). The Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. Journal of Sex Research, 44, 370–379. doi:10.1080/00224490701586730

- Diamond, L. M. (2000). Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual-minority women over a two-year period. Developmental Psychology, 36, 241–250. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.241

- Diamond, L. M. (2003). Was it a phase? Young women’s relinquishment of lesbian/bisexual identities over a 5-year period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 352–364. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.352

- Diamond, L. M. (2008a). Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 5–14. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5

- Diamond, L. M. (2008b). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Diamond, L. M., & Butterworth, M. (2008). Questioning gender and sexual identity: Dynamic links over time. Sex Roles, 59, 365–376. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9425-3

- Diamond, L. M., Pardo, S. T., & Butterworth, M. R. (2011). Transgender experience and identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 629–647). New York, NY: Springer.

- Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000). Sexing the body: Gender politics and the construction of sexuality. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gilligan, C. (2011). Joining the resistance. Oxford, UK: Polity Press.

- Girchick, L. B. (2008). Transgender voices: Beyond women and men. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

- Hines, S. (2007). TransForming gender: Transgender practices of identity, intimacy and care. Bristol, England: Policy Press.

- Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., & van Anders, S. M. (2018). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/amp0000307

- Jackson, S. (2006). Gender, sexuality and heterosexuality: The complexity (and limits) of heteronormativity. Feminist Theory, 7, 105–121. doi:10.1177/1464700106061462

- Jacobson, R., & Joel, D. (2018). An exploration of the relations between self-reported gender identity and sexual orientation in an online sample of cisgender individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1–20. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1239-y

- Joel, D., Tarrasch, R., Berman, Z., Mukamel, M., & Ziv, E. (2013). Queering gender: Studying gender identity in ‘normative’ individuals. Psychology & Sexuality, 5, 291–321. doi:10.1080/19419899.2013.830640

- Jordan-Young, R., & Rumiati, R. I. (2012). Hardwired for sexism? Approaches to sex/gender in neuroscience. Neuroethics, 5, 305–315. doi:10.1007/s12152-011-9134-4

- Kahalon, R., Shnabel, N., & Becker, J. (2018). Experimental studies on state self-objectification: A review and an integrative process model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1268. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01432

- Kuhle, B. X., & Radtke, S. (2013). Born both ways: The alloparenting hypothesis for sexual fluidity in women. Evolutionary Psychology, 11, 304–323.

- Kuper, L. E., Nussbaum, R., & Mustanski, B. (2012). Exploring the diversity of gender and sexual orientation identities in an online sample of transgender individuals. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 244–254. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.596954

- Lawrence, A. A. (2010). Sexual orientation versus age of onset as bases for typologies (subtypes) for gender identity disorder in adolescents and adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 514–545. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9594-3

- Martin, C. L., Andrews, N. C., England, D. E., Zosuls, K., & Ruble, D. N. (2017). A dual identity approach for conceptualizing and measuring children’s gender identity. Child Development, 88, 167–182. doi:10.1111/cdev.12568

- Matsuno, E., & Budge, S. L. (2017). Non-binary/genderqueer identities: A critical review of the literature. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9, 116–120. doi:10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8

- Meier, S. C., Pardo, S. T., Labuski, C., & Babcock, J. (2013). Measures of clinical health among female-to-male transgender persons as a function of sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 463–474. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-0052-2

- Morgan, E. M. (2013). Contemporary issues in sexual orientation and identity development in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1, 52–66. doi:10.1177/2167696812469187

- Mueller, S. C., De Cuypere, G., & T’Sjoen, G. (2017). Transgender research in the 21st century: A selective critical review from a neurocognitive perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 1155–1162. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17060626

- Nieder, T. O., Herff, M., Cerwenka, S., Preuss, W. F., Cohen‐Kettenis, P. T., De Cuypere, G., … Richter‐Appelt, H. (2011). Age of onset and sexual orientation in transsexual males and females. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 783–791. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02142.x

- Olson, K. R., Key, A. C., & Eaton, N. R. (2015). Gender cognition in transgender children. Psychological Science, 26, 467–474. doi:10.1177/0956797614568156

- Peplau, L. A., & Garnets, L. D. (2000). A new paradigm for understanding women’s sexuality and sexual orientation. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 329–350. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00169

- Ponse, B. (1978). Identities in the lesbian world: The social construction of self. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Poteat, V. P., & Anderson, C. J. (2012). Developmental changes in sexual prejudice from early to late adolescence: The effects of gender, race, and ideology on different patterns of change. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1403. doi:10.1037/a0026906

- Rees-Turyn, A., Doyle, C., Holland, A., & Root, S. (2008). Sexism and sexual prejudice (homophobia): The impact of the gender belief system and inversion theory on sexual orientation research and attitudes toward sexual minorities. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2, 2–25. doi:10.1080/15538600802077467

- Richards, C., Bouman, W. P., Seal, L., Barker, M. J., Nieder, T. O., & T’Sjoen, G. (2016). Non-binary or genderqueer genders. International Review of Psychiatry, 28, 95–102. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1106446

- Richardson, D. (2007). Patterned fluidities: (Re)imagining the relationship between gender and sexuality. Sociology, 41, 457–474. doi:10.1177/0038038507076617

- Rowniak, S., & Chesla, C. (2013). Coming out for a third time: Transmen, sexual orientation, and identity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 449–461. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-0036-2

- Savin-Williams, R. C. (2016). Sexual orientation: Categories or continuum? Commentary on Bailey et al. (2016). Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17, 37–44. doi:10.1177/1529100616637618

- Sharpe, D. (2015). Your chi-square test is statistically significant: Now what? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 20, 2–10.

- Shively, M. G., & DeCecco, J. P. (1977). Components of sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 3, 41–48. doi:10.1300/J082v03n01_04

- Siebler, K. (2012). Transgender transitions: Sex/gender binaries in the digital age. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 16, 74–99. doi:10.1080/19359705.2012.632751

- Striepe, M. I., & Tolman, D. L. (2003). Mom, dad, I’m straight: The coming out of gender ideologies in adolescent sexual-identity development. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 32, 523–530. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_4

- Szymanski, D. M., Moffitt, L. B., & Carr, E. R. (2011). Sexual objectification of women: Advances to theory and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 6–38. doi:10.1177/0011000010378402

- Van Caenegem, E., Wierckx, K., Elaut, E., Buysse, A., Dewaele, A., Van Nieuwerburgh, F., … T’Sjoen, G. (2015). Prevalence of gender nonconformity in Flanders, Belgium. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1281–1287. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0452-6

- Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2009). Doing gender in sex and sex research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 883–898. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9565-8

- Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 85–101. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y

- Warner, L. R., & Shields, S. A. (2013). The intersections of sexuality, gender, and race: Identity research at the crossroads. Sex Roles, 68, 803–810. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0281-4

- White, J. W., Donat, P. L. N., & Bondurant, B. (2001). A developmental examination of violence against girls and women. In R. K. Unger (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of women and gender (pp. 343–357). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Wilson, M. (2002). ‘I am the Prince of pain, for I am a princess in the brain’: Liminal transgender identities, narratives and the elimination of ambiguities. Sexualities, 5, 425–448. doi:10.1177/1363460702005004003

- Zucker, K. J., Lawrence, A. A., & Kreukels, B. P. (2016). Gender dysphoria in adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 217–247. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093034

APPENDIX

The Multigender Identity Questionnaire

In the past 12 months, have you felt satisfied being a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

2. In the past 12 months, have you felt satisfied being a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

3. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

4. In the past 12 months, have you thought of yourself as a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

5. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you have to work at being a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

6. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you have to work at being a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

7. In the past 12 months, have you felt pressured by others to be a “proper” woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

8. In the past 12 months, have you felt pressured by others to be a “proper” man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

9. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you were a “real” woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

10. In the past 12 months, have you felt that you were a “real” man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

11. In the past 12 months, when you went into a department store to buy yourself clothing, did you shop in a department labeled for your sex?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

12. In the past 12 months, have you worn the clothes of the other sex?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

13. In the past 12 months, have you felt more like a man than like a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

14. In the past 12 months, have you felt more like a woman than like a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

15. In the past 12 months, have you sometimes felt like a man and sometimes like a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

16. In the past 12 months, have you felt somewhere in between a woman and a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

17. In the past 12 months, have there been times when you’ve felt that you are neither a man nor a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

18. In the past 12 months, have you felt that it is/it would be better for you to live as a man than as a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

19. In the past 12 months, have you felt that it is/it would be better for you to live as a woman than as a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never

20. In the past 12 months, have you had the wish or desire to be a man?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

21. In the past 12 months, have you had the wish or desire to be a woman?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

22. In the past 12 months, have you disliked your body because of its female form?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

23. In the past 12 months, have you disliked your body because of its male form?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never, Not relevant

24. In the past 12 months, have you wished you had the body of the “other” sex?

Always, Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never