ABSTRACT

Even though sexual activity frequently takes place with another person, research rarely focuses on how partners influence each other’s sexual lives. This study used the sexual dyad to compare the concept of actual versus perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and explored how each is related to older partnered individuals’ sexual satisfaction. Further, the study assessed the robustness of the association between sexual interest discrepancy and sexual satisfaction, if any, by controlling for emotional intimacy. The actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) using structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to examine 677 heterosexual couples ages 60 to 75 in Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal. Although a couple’s actual discrepancy in sexual interest was not predictive of female and male partners’ sexual satisfaction, perceived discrepancy was negatively associated with sexual satisfaction in both partners after controlling for emotional intimacy. This indicates that the subjective feelings of being sexually dissimilar seem to be more important to sexual satisfaction than the actual mismatch among partners in older heterosexual couples. Moreover, the finding that emotional intimacy is linked with sexual satisfaction underscores the importance of a broader perspective on sexuality among older adults.

Conceptual definitions of sexual satisfaction are scarce. An assessment of a layperson’s understanding of being sexually satisfied within heterosexual relationships defined it “as the emotional experience of frequent mutual sexual pleasure” (Pascoal et al., Citation2014, p. 27). This definition stresses that partnered sexuality is a joint activity, involving desires, feelings, and pleasure as mutual experiences. Despite this, the majority of studies assess sexual health from an individualistic perspective (Mark & Leistner, Citation2014). For example, an extensive amount of research based on individual-level data points to the prevalence of sexual desire problems in older individuals (Laumann et al., Citation2005; Mitchell et al., Citation2013; Waite et al., Citation2009). Loss of sexual desire appear to be especially prevalent among older women (Lindau & Gavrilova, Citation2010; Waite et al., Citation2009). Contrary to an individualistic approach, it seems important to understand sexual desire problems within a couple context (Mark & Lasslo, Citation2018; Mark & Leistner, Citation2014). For instance, findings based on a self-selected online survey of U.S. adults aged 50 to 85 years showed a significant and positive association between individuals’ reports on wanting sex as much as their partner and sexual satisfaction (Gillespie, Citation2017a). Moreover, several theoretical conceptualizations about interpersonal processes—such as sexual desire discrepancy (Mark, Citation2015; Mark & Lasslo, Citation2018; Willoughby et al., Citation2014), little sexual synchronicity (Gillespie, Citation2017a, Citation2017b), mismatched emphasis on sex (Orr et al., Citation2019), and perceived sexual incompatibility with partner (Witting et al., Citation2008)—have all been negatively associated with important relationship aspects, such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual activity, relationship quality, relationship stability, and couple conflict.

According to the sexual synchronicity model, both sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction among older men and women are affected by communication and three intertwined forms of sexual synchronicity/asynchronicity (Gillespie, Citation2017b; Gillespie et al., Citation2017). The first form, situational asynchronicity, refers to conditions outside of the couple’s relationship that disrupt the possibility for sexual activity (e.g., conflicting time schedules or health incapability). The second form, behavioral asynchronicity, refers to partners being different in their sexual interests and behaviors, and the absence of sexual reciprocity (e.g., one partner requesting but not giving oral sex). The third form, attitudinal asynchronicity, pertains to differences in sexual attitudes (e.g., the way partners evaluate the importance of sex in older age). Although initial evidence suggests a negative relationship between sexual desire discrepancy and sexual satisfaction (Mark, Citation2015), research exploring mismatches in sexual interest in older heterosexual couples is lacking. Our aim in this study was to focus on the interpersonal dynamics of sexual interest by exploring the links between two sexual discrepancy concepts (actual discrepancy in sexual interest within couples versus individuals’ perceived discrepancy in sexual interest) and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual couples aged 60 to 75 years.

Actual versus Perceived Discrepancy Concepts

A study among heterosexual dating couples with a mean age of 20 years found that the perception of a discrepancy in sexual desire was negatively associated with both men’s and women’s sexual satisfaction (Davies et al., Citation1999). In men, however, the study did not show a significant association between a couple’s actual desire discrepancy score (measured by a divergence between his and her reports of the level of sexual desire) and sexual satisfaction. Furthermore, no significant association was found between the individual’s perception of desire discrepancy and the couple’s actual desire discrepancy score, which may indicate conceptual differences between the two measures. The possibility that there may be systematic differences in actual and perceived desire discrepancies complements the findings of three dyadic studies indicating perceptual biases in the estimation of a partner’s sexual desire, with men being particularly likely to underperceive their female partners’ level of desire in all three studies (Muise et al., Citation2016). Women also significantly underperceived their partners’ sexual desire, but only in one of the three studies. Another study exploring the association between sexual satisfaction and actual versus perceived desire discrepancies among two samples of long-term couples (on average aged 30 to 40 years) found that greater perceived, but not actual, sexual desire discrepancy was negatively related to sexual satisfaction (Sutherland et al., Citation2015). A limitation of this study was that couples’ actual and perceived desire discrepancies were assessed in separate samples and that different measures were used to assess the two concepts.

Emotional Intimacy in Aging Couples

Some studies suggest that sexual satisfaction and well-being in older women and men are not matters of quantity but quality (Forbes et al., Citation2017; Gillespie, Citation2017b; Lodge & Umberson, Citation2012; Ménard et al., Citation2015). For instance, research findings seem to indicate that, compared to penetrative intercourse, other types of intimate physical activities such as exchanging affection (kissing, cuddling, hugging, caressing) become more essential as a source of sexual satisfaction as people age (Clarke, Citation2006; Hinchliff & Gott, Citation2004; Hinchliff et al., Citation2018; Sandberg, Citation2013). In addition, emotional intimacy, defined as “a perception of closeness to another that is conducive to the sharing of personal feelings, accompanied by expectations of understanding, affirmation, and demonstrations of caring” (Sinclair & Dowdy, Citation2006, p. 194), seems to be associated with what is perceived as “good sex.” For example, a qualitative study investigating facilitators of “optimal” sexuality in older age indicated a strong link between relationship quality (closeness, emotional intimacy, trust, feelings of love, caring for each other, and communication) and “optimal sexual experiences” (Ménard et al., Citation2015, p. 87). It is interesting that while a growing number of qualitative approaches point to the importance of emotional and sexual intimacy in older ages (Clarke, Citation2006; Hinchliff & Gott, Citation2004; Hinchliff et al., Citation2018; Lodge & Umberson, Citation2012; Ménard et al., Citation2015; Sandberg, Citation2013), quantitative studies exploring the relationship between emotional intimacy and sexual satisfaction in older heterosexual couples are lacking.

Aims

Four considerable gaps in the research literature can be observed. First, despite the fact that sexual relations are inherently dualistic (Byers & Rehman, Citation2014; De Jong & Reis, Citation2014), few studies have used dyadic approaches to explore sexual satisfaction, particularly in older adults (Muise et al., Citation2018; Štulhofer et al., Citation2020). This is regrettable, as recent evidence demonstrates how dynamics within couples can promote relationship quality and sexual satisfaction in midlife and older couples (Fisher et al., Citation2015; Orr et al., Citation2019). Second, despite the fact that initial research points to the significance of emotional intimacy and physical affection later in life (Clarke, Citation2006; Lodge & Umberson, Citation2012; Sandberg, Citation2013), scant attention has been directed to the dynamics of older couples’ sexuality and their perceived emotional support. The third gap in the literature concerns the lack of an interpersonal perspective on sexual interest (Dewitte et al., Citation2020; Mark, Citation2015). For instance, while it is common to explore the lack of sexual interest in older individuals (Laumann et al., Citation2005; Mitchell et al., Citation2013), understanding an individual’s sexual interest relative to their partner’s sexual interest seems highly understudied in aging couples. A fourth gap in the literature concerns inconsistencies on how to conceptualize sexual discrepancy concepts (Mark, Citation2012, Citation2015). Preliminary studies point to conceptual and empirical differences between actual and perceived desire discrepancy (Davies et al., Citation1999; Sutherland et al., Citation2015). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored these concepts in older heterosexual couples.

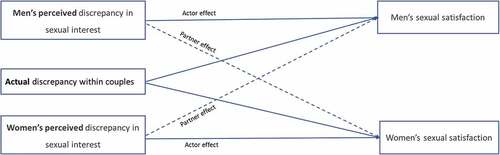

Based on these four literature gaps and building on a recent exploration of the mechanisms underlying the association between perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction among older heterosexual partnered adults (Fischer et al., Citation2020), the present study aimed to (1) examine how discrepancies among partners’ self-reported sexual interest score compare to a person’s perceived discrepancy by applying similar methodologies within the same sample; (2) assess if and how each concept is related to sexual satisfaction in older heterosexual couples using dyadic analysis; and (3) explore the robustness of the associations between sexual interest discrepancy and sexual satisfaction by controlling for perceived emotional intimacy. The theoretically expected associations of the dyadic model are depicted in .

Figure 1. The actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) schematically illustrating the association between discrepancy in sexual interest (actual and perceived) and each partner’s sexual satisfaction, statistically controlling for age and country affiliation. Perceived emotional intimacy was used as an additional control in the second path-analytic APIM (control variables and covariances are not depicted in the conceptual model)

Using dyadic data collected from European heterosexual couples aged 60 to 75 years, the study addressed three specific research questions:

RQ1: Is there a significant difference between perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and actual discrepancy in sexual interest within the couple?

RQ2: What are the associations between actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction in older couples?

RQ3: Finally, does controlling for perceived emotional intimacy change the associations between actual and perceived discrepancy and sexual satisfaction, if any?

Method

Procedure

Data for this multinational survey on healthy sexual aging were collected in late 2016 and early 2017. Using probability-based sampling, the international polling organization Ipsos recruited 3,816 individuals aged 60 to 75 years from Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal. In keeping with the working definition of “older age” used by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN), the inclusion criteria for both partners was defined as being at least 60 years old (WHO, Citation2001). Due to concerns for falling response rates and the uncertainty of whether decreasing cognitive skills would impede participation in respondents who were older than age 75, the upper age limit was set at 75 years. Potential subjects were contacted by phone using the national phone registries in Norway, Denmark, and Belgium. Due to the absence of an updated and complete national phone registry, multistage stratified sampling was implemented in Portugal. Individuals who confirmed their participation during the telephone recruitment interview received a 200-item postal/mail questionnaire with a prepaid return envelope. The rates of those who actually returned the completed and approved questionnaire after having confirmed their participation during the recruitment interview were 68% in Norway, 57% in Belgium, 52% in Denmark, and 26% in Portugal. For a more detailed description of the sample and the recruitment process, see Træen et al. (Citation2019).

In addition to recruiting individual participants, we aimed to collect data from both members of a couple. The objective was to recruit at least 100 couples in each country within the targeted age range of 60 to 75 years. During the telephone recruitment interview, Ipsos asked the prospective participant whether he or she lived with a partner, and if they could talk to this partner. In cases where the partner was at home, Ipsos continued the interview with the partner (reciting all recruitment text). If the partner was not available, Ipsos asked for the partner’s name and telephone number, as well as the best time to call. Sampled couples were asked to fill out the questionnaire in private and submit it separately. In the current study, all analyses were based on this dyadic subsample of 677 heterosexual couples (218 from Norway, 207 from Denmark, 135 from Belgium, and 117 from Portugal). The project team had no information about the percentages of partners who refused, could not be reached, or did not complete the recruitment process.

Questionnaire

The survey contained approximately 200 items covering questions on participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, physical and mental health, lifestyle, satisfaction with life, body image, relationship factors, sexual behavior, sexual attitudes, sexual function, and sexual satisfaction, with most of the indicators being used in previous sex surveys (Træen et al., Citation2019). Questions were initially written in English and thereafter translated—applying translation and back-translation procedures—into the countries’ respective languages (Norwegian, Danish, Dutch/French, and Portuguese) by native speakers on the project’s research team and staff from Ipsos.

Measures

The main components of the proposed model were sexual satisfaction, actual discrepancy in sexual interest (defined as actual differences in self-reported sexual interest among partners), perceived discrepancy in sexual interest (defined as a person’s own sexual interest compared to the perception of his or her partner’s sexual interest), and emotional intimacy (see Appendix A for wording and construction of all items).

Sexual Satisfaction

Two single-item indicators assessed sexual satisfaction. One item assessed participants’ satisfaction with their sexual life in the past year on a 5-point scale (1 = Completely dissatisfied, 5 = Completely satisfied), and one asked participants to assess how satisfied they were with their current level of sexual activity on a 5-point scale (1 = Very satisfied, 5 = Very dissatisfied). Scores from the latter item were reverse-recoded, so higher scores denoted higher sexual satisfaction. The indicator demonstrated a satisfactory internal consistency reliability in our dyadic sample (coefficient α =.90).

Actual Discrepancy in Sexual Interest

All participants were asked to indicate their sexual interest (i.e., “I am not interested in sex”) while having their regular partner or spouse in mind. The item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree), where higher scores denoted greater interest in sex. To assess the actual discrepancy in sexual interest within couples, we computed the difference between each partner’s score (the absolute value of the male partner’s interest in sex subtracted from the absolute value of the female partner’s interest in sex). Difference scores ranged from 0 (no actual difference in partners’ sexual interest) to 4, with higher scores indicating greater discrepancy in sexual interest within a couple. Since both members of each couple had the same discrepancy score, the new construct is a dyad-level indicator (Kenny et al., Citation2006).

Perceived Discrepancy in Sexual Interest

To assess perceived discrepancy in sexual interest, we computed the absolute difference between a participant’s own sexual interest (i.e., “I am not interested in sex”) and the participant’s perception of his or her partner’s sexual interest (i.e., “My partner has no interest in sex”). Both items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree) (Fischer et al., Citation2020). Perceived discrepancy scores ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating no mismatch between the partners’ interest in sex; the higher the score, the greater the perceived discrepancy in sexual interest.

Emotional Intimacy

Adopted from Sinclair and Dowdy (Citation2006), the validated five-item Emotional Intimacy Scale assessed a person’s perceived emotional support in his or her closest relationship (e.g., “My thoughts and feelings are understood and affirmed by this person”). All items were measured on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree) and were reverse-scored, so higher scores reflect higher emotional intimacy. The scale had excellent internal consistency reliability in the dyadic sample (coefficient α = .90).

Statistical Analysis

We used the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny et al., Citation2006) to examine intimate partners’ influence on each other’s sexual satisfaction. One advantage of APIM is that it enables the estimation of individuals’ sexual satisfaction, taking into account both intrapersonal (actor) effects and interpersonal (partner) effects. In the current study, actor effects refer to how an individual’s perceived discrepancy in sexual interest influences his or her own sexual satisfaction, while partner effects refer to how the individual’s perceived discrepancy in sexual interest influences his or her partner’s sexual satisfaction () (Cook & Kenny, Citation2005; Kenny et al., Citation2006). Because actual discrepancy in sexual interest is a dyad-level variable—in other words, both partners have the same discrepancy score—the distinction between actor and partner effects is not feasible here. Perceived emotional intimacy was used as a control in the second path analytic APIM. All analyses controlled for age and country of residence (three dummy variables, with Norway as a reference category, were used).

Actor and partner effects were estimated using a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach (Kenny et al., Citation2006). Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI; values ≥ 0.95 represent good fit) (Hu & Bentler, Citation1998; Kenny et al., Citation2006), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values ≤ 0.08 indicate acceptable fit and ≤ 0.05 indicate good fit) (Byrne, Citation2016). Due to the size of our sample (677 dyads), the model’s chi-square value was expected to be significant regardless of actual fit (Kenny et al., Citation2006). To handle missing values, we applied the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method (Graham, Citation2012). Except for descriptive and bivariate analyses, which were carried out in SPSS 25.0, all statistical analyses were conducted in IBM AMOS, Version 25.0 (Arbuckle, Citation2017).

Results

Sample Characteristics

On average, male partners were older than female partners (Mmen = 68.0, SD = 4.04; Mwomen = 66.1, SD = 3.92, t (676) = 15.24, p < .001; η2 = .26) (). Most couples reported either secondary (40% of men and 42% of women) or tertiary/college education (lower to higher university level) (39% of men and 37% of women). The majority of partners were retired (79% of men, 70% of women) and living in a small town or rural area (37% and 29%, respectively). The vast majority of the couples had been in the relationship for 30 years or more (81%). With regard to the level of sexual activity (sexual intercourse, masturbation, petting, or fondling) in the past year, the vast majority reported that they had been sexually active (89% of men and 87% of women), with almost all participants reporting that their most recent sexual partner had been their spouse (99%). Because all recruited couples were heterosexual, all dyad members could be distinguished/differentiated from each other by sex (Kenny et al., Citation2006).

Table 1. Individual and relational characteristics of couples, aged 60 to 75 years, from four European countries (n = 677 dyads)

Female partners reported being more sexually satisfied than their male partners, t(668) = −3.65, p < .001, η2 = .02 (). No significant difference in reported levels of emotional intimacy was found between male and female partners. Actual discrepancy in sexual interest was observed in 56% of the couples. A discrepancy between how an individual’s sexual interest compared to his or her partner’s perceived sexual interest was observed in 38% of the male partners and 31% of the female partners.

Table 2. Overview of the studied variables: Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages (n = 677 dyads)

The strongest within-couple correlation was found between male and female sexual satisfaction (r = .53, p < .001), while the weakest association was observed between male and female perceived discrepancy in sexual interest (r = .27, p < .001).

Comparison of Actual versus Perceived Discrepancy

To test for group differences in the discrepancy concepts (research question 1), a paired-sample t test was conducted (). Couples’ actual discrepancy in sexual interest was significantly higher than both male (p < .001) and female partners’ perceived discrepancy interest in sex (p < .001). No significant difference between male and female partners’ perceived discrepancy was found (p < .059).

Table 3. Bivariate analyses: Differences in discrepancy in sexual interest in older heterosexual couples

Actor and Partner Effects

The results of path-analytic APIM analysis (Models 1 and 2) are presented in . Both models were a good fit to the data (Model 1: χ2(15) = 18.10, CFI = .999; RMSEA = .017, 90% confidence interval [CI] = [.000–.042]; Model 2: χ2(144) = 415.26, CFI = .961; RMSEA = .053, 90% CI = [.047–.059]).

Table 4. Relationships between actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction in older couples from four European countries

To answer research question 2, we assessed the associations between actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction while controlling for age and country (Model 1). Three patterns in the findings emerged. First, the greater the discrepancy in sexual interest that partnered women and men perceived, the lower their reported sexual satisfaction (actor effects). Second, male partners’ perceived discrepancy in sexual interest was negatively related to their female partners’ sexual satisfaction; the greater the male partner’s perceived discrepancy, the lower the female partner’s sexual satisfaction (partner effect). Third, actual discrepancy in sexual interest was unrelated to sexual satisfaction in both partners.

Concerning research question 3, we found that, when controlling for age, country, and emotional intimacy (Model 2), the pattern of relationships between discrepancy in sexual interest (actual and perceived) and sexual satisfaction did not substantially change. In addition, we observed a positive association between emotional intimacy and reported sexual satisfaction, but only as actor (and not partner) effects; that is, the more emotional intimacy partnered men and women perceived, the greater their own sexual satisfaction.

Considering the other control variables, country of residence was not significantly associated with either male or female partner’s sexual satisfaction. Age, which was used as another control variable, was negatively related to male sexual satisfaction (b = −.03; p < .05) but positively related to female sexual satisfaction (b = .02; p < .05). Overall, APIM explained 25% of the variance in female and 26% of variance in male sexual satisfaction.

Discussion

Compared to other couple-related research (e.g., studies of romantic relationships), the implementation of dyadic approaches in sexual satisfaction research is limited (Byers & Rehman, Citation2014; Muise et al., Citation2018). In the current study, a dyadic sample of heterosexual adults was used to investigate actual versus perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and to explore their role in older couples’ sexual satisfaction. We found that while a couple’s actual discrepancy in sexual interest did not predict individual sexual satisfaction, perceived discrepancy was negatively associated with sexual satisfaction in both men and women. In addition, reported emotional intimacy was positively related to sexual satisfaction, but only as actor (and not partner) effects.

Concerning research question 1, exploring the differences between actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest, we found that actual discrepancy in sexual interest within couples was significantly higher than individually perceived discrepancies in sexual interest. This finding is similar to that of Davies et al. (Citation1999), who found a higher prevalence of couples’ actual desire discrepancy than the individuals’ perception of desire discrepancy. One possible explanation for why older adults perceive less within-couple differences in sexual interest may be due to the unintentional use of heuristic shortcuts, where the individual uses personal characteristics/preferences as a point of reference when assessing their partners’ characteristics/preferences (Davis et al., Citation1986; Schul & Vinokur, Citation2000). For instance, in three dyadic studies that sampled established couples, Muise et al. (Citation2016) found that individuals were inclined to project their own level of sexual desire onto their intimate partner––assuming similarity between their own levels of sexual desire and the levels of sexual desire of their partners. Despite the possibility that projection may lead to biased judgments (Schul & Vinokur, Citation2000), assumed similarity, such as perceived sexual compatibility, has been found to increase the likelihood of being sexually satisfied (Mark et al., Citation2013; Offman & Matheson, Citation2005). Moreover, it has recently been suggested that individuals’ sexual satisfaction may be a result of motivated cognitions strategies (De Jong & Reis, Citation2014). Specifically, according to De Jong and Reis, individuals are motivated to overperceive sexual similarity as a strategy to reduce vulnerability in their sexual relationship––thereby promoting positive feelings of security, safety, intimacy, and sexual satisfaction. Motivational cognition strategies may also explain why the average levels of perceived discrepancy in sexual interest were generally low in our sample.

In exploring the association between actual and perceived discrepancies in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction (research question 2), it was found that as older adults perceive a greater discrepancy between their own and their partners’ interest in sex, they tend to report lower sexual satisfaction. This finding is consistent with previous research, suggesting a negative link between perceived desire discrepancy and sexual satisfaction in several samples of partnered adults (Bridges & Horne, Citation2007; Davies et al., Citation1999; Fischer et al., Citation2020; Gillespie, Citation2017a; Sutherland et al., Citation2015). Moreover, it is consistent with Gillespie’s (Citation2017b) model of sexual synchronicity, where feeling “out of sync” (p. 453) can lead to lower sexual satisfaction in aging men and women. Interestingly, actual mismatch in partners’ sexual interest did not predict their sexual satisfaction levels. This suggests that perceptions may be more important than reality––a finding which has also been evident in other research areas (Cohen et al., Citation2012; Hinnekens et al., Citation2020; Mark et al., Citation2013; Montoya et al., Citation2008; Murray et al., Citation2002). This means that the subjective feelings of being sexually similar/dissimilar seem to be more important to sexual and/or relationship satisfaction than a couple’s actual sexual (mis)match (De Jong & Reis, Citation2014; Mark et al., Citation2013). Our findings strongly support conceptual, methodological, and empirical distinctions between perceived and actual sexual interest and/or desire (Davies et al., Citation1999; Sutherland et al., Citation2015).

In addition to the aforementioned actor effects, we found one gender-specific partner effect. Men’s perceived discrepancy in sexual interest significantly contributed to their female partners’ sexual satisfaction. One possible explanation may be that the male partner’s perceived discrepancy in sexual interest elicits feelings of pressure or sexual obligation, which in turn decreases the female partner’s sexual satisfaction. For instance, both partner conflicts due to sexual desire discrepancies and feelings of obligation to meet partners’ sexual desires are common among older women (Hartmann et al., Citation2004).

Regarding research question 3, we found that controlling for emotional intimacy did not change the pattern of significant/nonsignificant relationships between discrepancy in sexual interest (actual and perceived) and sexual satisfaction in aging couples. In addition, we found positive associations between individuals’ emotional intimacy and older adults’ sexual satisfaction. These findings are similar to those of earlier studies where emotional intimacy was found to be associated with sexual satisfaction (Štulhofer et al., Citation2014).

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the current research include a dyadic approach to the examination of processes of mutual influence in older couples’ sex lives and a statistical, high-powered, large-scale sample. However, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, it should be noted that actual discrepancy in sexual interest, although different from the measure of perceived discrepancy, is not an objective measure. It is likely that individuals use different benchmarks when they evaluate their levels of sexual interest. This means that two partners may in fact have the same level of sexual interest but report different scores (or vice versa) due to specific personal benchmarks. We acknowledge that calculating actual discrepancy in sexual interest through an item measuring each partner’s agreement with the statement “I’m not interested in sex” may cause variability in how partners interpret the item and may encourage misinterpretations of the finding (Schick et al., Citation2014). To address this limitation, we suggest that future studies build their discrepancy measures on components assessing not the degree but the absolute frequency of each partners’ sexual interest (e.g., “Thinking about the past month, how often have you been interested in engaging in some kind of sexual activity with your partner?”; with response options from 1 = Not at all to 7 = Many times a day). Further, it is important to note that although we found that couples differed in their actual and perceived levels of sexual interest, the means of the reported discrepancies were fairly small. It is likely that couples with major desire discrepancies may not have wanted to participate in a study on sexual health, or that those couples already have dissolved their relationships and thus were no longer accessible for recruitment (Fisher et al., Citation2015; Heiman et al., Citation2011). Although individual data were collected in national probability-based samples of adults’ aged 60 to 75 years in Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal, the sampling procedure of the dyadic subsample did not ensure that our findings are representative of the respective European populations at that age. It is likely that more liberal and sexually positive older couples are overrepresented in the sample (Bogaert, Citation1996; Dunne et al., Citation1997; Strassberg & Lowe, Citation1995). Exactly how this sampling bias has affected our findings is not clear, but it may limit the generalizability of results. In addition, we were unable to recruit nonheterosexual couples, so this study’s findings cannot be extended to older same-sex couples.

Another limitation pertains to the use of single-item measures to assess sexual satisfaction. We acknowledge that the psychometric properties of multiple-item scales may outweigh those of a single-item measure. However, comparable one-item measures of sexual satisfaction have been used in many large-scale national surveys (Corona et al., Citation2010; Field et al., Citation2013; Heiman et al., Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2016). Further, there is evidence that single-item measures of sexual satisfaction demonstrate convergent validity with several sexual satisfaction scales (Mark et al., Citation2014; Štulhofer et al., Citation2010). In addition, Mark et al. (Citation2014) found support for convergent validity by assessing the association between a single-item measure of sexual satisfaction and participants’ relationship satisfaction. Following Mark et al. (Citation2014), we correlated the additive indicator of sexual satisfaction with participants’ relationship satisfaction and found significant positive associations between the two theoretically related concepts (rmen = .36, p < .001; rwomen = .40, p < .001). Next, it was originally planned to select countries that would reflect different geographical regions in Europe (south, north, east, and west), which we assumed would differ in their sexual cultures. Owing to financial constraints and problems finding research associates from Eastern Europe, the selected countries (Norway, Denmark, Belgium, and Portugal) rather represent the national affiliation of the final project team (Štulhofer et al., Citation2019). Finally, given the cross-sectional design of our study, the direction of paths between emotional intimacy, actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest, and sexual satisfaction could not be established. Consequently, the terms actor and partner “effects” were used in a methodological, not causal, sense. Longitudinal dyadic studies would be needed to explore the direction of these associations.

Conclusion

Previous research on sexual desire discrepancy suggested several important conceptual and methodological points: (1) the construct should be explored in both short-term and long-term relationships and (2) the construct should be carefully specified to minimize inconsistent findings (Davies et al., Citation1999; Mark, Citation2012, Citation2015; Sutherland et al., Citation2015). The current study’s findings provide evidence supporting the need to differentiate between actual and perceived discrepancy in sexual interest/desire. We found that only perceived discrepancy in sexual interest predicted sexual satisfaction in older couples (Davies et al., Citation1999; Sutherland et al., Citation2015). In addition, the finding that emotional intimacy was important for sexual satisfaction in older heterosexual couples adds to an emerging body of literature concerning diverse, intimate, and erotically flexible pathways to healthy sexual aging (Clarke, Citation2006; Hinchliff et al., Citation2018; Müller et al., Citation2014; Sandberg, Citation2013; Štulhofer et al., Citation2020).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2017). Amos (Version 25.0) [ Computer Program]. IBM SPSS.

- Bogaert, A. F. (1996). Volunteer bias in human sexuality research: Evidence for both sexuality and personality differences in males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02437932

- Bridges, S. K., & Horne, S. G. (2007). Sexual satisfaction and desire discrepancy in same sex women’s relationships. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 33(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230600998466

- Byers, E. S., & Rehman, U. S. (2014). Sexual well-being. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus, & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology: Vol. 1. Person-based approaches (pp. 317–337). American Psychological Association.

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Clarke, L. H. (2006). Older women and sexuality: Experiences in marital relationships across the life course. Canadian Journal on Aging, 25(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1353/cja.2006.0034

- Cohen, S., Schulz, M. S., Weiss, E., & Waldinger, R. J. (2012). Eye of the beholder: The individual and dyadic contributions of empathic accuracy and perceived empathic effort to relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027488

- Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405

- Corona, G., Lee, D. M., Forti, G., O’Connor, D. B., Maggi, M., O’Neill, T. W., Pendleton, N., Bartfai, G., Boonen, S., Casanueva, F. F., Finn, J. D., Giwercman, A., Han, T. S., Huhtaniemi, I. T., Kula, K., Lean, M. E. J., Punab, M., Silman, A. J., Vanderschueren, D., Wu, F. C. W., & The Emas Study Group. (2010). Age-related changes in general and sexual health in middle-aged and older men: Results from the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1362–1380. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uio.no/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01601.x

- Davies, S., Katz, J., & Jackson, J. L. (1999). Sexual desire discrepancies: Effects on sexual and relationship satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28(6), 553–567. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018721417683

- Davis, H. L., Hoch, S. J., & Ragsdale, E. K. E. (1986). An anchoring and adjustment model of spousal predictions. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/209045

- De Jong, D. C., & Reis, H. T. (2014). Sexual kindred spirits: Actual and overperceived similarity, complementarity, and partner accuracy in heterosexual couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(10), 1316–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214542801

- Dewitte, M., Carvalho, J., Corona, G., Limoncin, E., Pascoal, P., Reisman, Y., & Štulhofer, A. (2020). Sexual desire discrepancy: A position statement of the European Society for Sexual Medicine. Sexual Medicine, 8(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2020.02.008

- Dunne, M. P., Martin, N. G., Bailey, J. M., Heath, A. C., Bucholz, K. K., Madden, P. A., & Statham, D. J. (1997). Participation bias in a sexuality survey: Psychological and behavioural characteristics of responders and non-responders. International Journal of Epidemiology, 26(4), 844–854. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/26.4.844

- Field, N., Mercer, C. H., Sonnenberg, P., Tanton, C., Clifton, S., Mitchell, K. R., Erens, B., Macdowall, W., Wu, F., Datta, J., Jones, K. G., Stevens, A., Prah, P., Copas, A. J., Phelps, A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2013). Associations between health and sexual lifestyles in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382(30), 1830–1844. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62222-9

- Fischer, N., Træen, B., Štulhofer, A., & Hald, G. M. (2020). Mechanisms underlying the association between perceived discrepancy in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction among partnered older adults in four European countries. European Journal of Ageing, 17, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00541-x

- Fisher, W. A., Donahue, K. L., Long, J. S., Heiman, J. R., Rosen, R. C., & Sand, M. S. (2015). Individual and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife couples: Dyadic analysis of the International Survey of Relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1609–1620. https://doi.org/1007/s10508-014-0426-8

- Forbes, M. K., Eaton, N. R., & Krueger, R. F. (2017). Sexual quality of life and aging: A prospective study of a nationally representative sample. Journal of Sex Research, 54(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1233315

- Gillespie, B. J. (2017a). Correlates of sex frequency and sexual satisfaction among partnered older adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1176608

- Gillespie, B. J. (2017b). Sexual synchronicity and communication among partnered older adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1182826

- Gillespie, B. J., Hibbert, K., & Sanguinetti, A. (2017). A review of psychosocial and interpersonal determinants of sexuality in older adulthood. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(3), 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0117-2

- Graham, J. W. (2012). Missing data: Analysis and design. Springer.

- Hartmann, U., Philippsohn, S., Heiser, K., & Rüffer-Hesse, C. (2004). Low sexual desire in midlife and older women: Personality factors, psychosocial development, present sexuality. Menopause, 11(6), 726–740. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GME.0000143705.42486.33

- Heiman, J. R., Long, J. S., Smith, S. N., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M. S., & Rosen, R. C. (2011). Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3

- Hinchliff, S., & Gott, M. (2004). Intimacy, commitment, and adaptation: Sexual relationships within long-term marriages. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(5), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504045889

- Hinchliff, S., Tetley, J., Lee, D., & Nazroo, J. (2018). Older adults’ experiences of sexual difficulties: Qualitative findings from the English Longitudinal Study on Ageing (Elsa). Journal of Sex Research, 55(2), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1269308

- Hinnekens, C., Stas, L., Gistelinck, F., & Verhofstadt, L. L. (2020, February). “I think you understand me.” Studying the associations between actual, assumed, and perceived understanding within couples. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(1), 46–60. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uio.no/10.1002/ejsp.2614

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press.

- Laumann, E. O., Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Paik, A., Gingell, C., Moreira, E., & Wang, T. (2005). Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: Prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250

- Lee, D. M., Nazroo, J., O’Connor, D. B., Blake, M., & Pendleton, N. (2016). Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0465-1

- Lindau, S. T., & Gavrilova, N. (2010). Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. British Medical Journal, 340(c810), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c810

- Lodge, A. C., & Umberson, D. (2012). All shook up: Sexuality of mid- to later life married couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74(3), 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00969.x

- Mark, K. P. (2012). The relative impact of individual sexual desire and couple desire discrepancy on satisfaction in heterosexual couples. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 27(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2012.678825

- Mark, K. P. (2015). Sexual desire discrepancy. Current Sexual Health Reports, 7(3), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-015-0057-7

- Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

- Mark, K. P., & Lasslo, J. A. (2018). Maintaining sexual desire in long-term relationships: A systematic review and conceptual model. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1437592

- Mark, K. P., & Leistner, C. E. (2014). The complexities and possibilities of utilizing romantic dyad data in sexual health research. Health Education Monograph, 31(2), 68–71. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kristen_Mark/publication/273995495_The_Complexities_and_Possibilities_of_Utilizing_Romantic_Dyad_Data_in_Sexual_Health_Research/links/5511b00d0cf270fd7e315e7b/The-Complexities-and-Possibilities-of-Utilizing-Romantic-Dyad-Data-in-Sexual-Health-Research.pdf

- Mark, K. P., Milhausen, R. R., & Maitland, S. B. (2013). The impact of sexual compatibility on sexual and relationship satisfaction in a sample of young adult heterosexual couples. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28(3), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2013.807336

- Ménard, A. D., Kleinplatz, P. J., Rosen, L., Lawless, S., Paradis, N., Campbell, M., & Huber, J. D. (2015). Individual and relational contributors to optimal sexual experiences in older men and women. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2014.931689

- Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Ploubidis, G. B., Jones, K. G., Datta, L., Field, N., Copas, A. J., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Phelps, A., Johnson, A. M., & Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: Findings form the Third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382(9907), 1817–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta‐analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096700

- Muise, A., Maxwell, J. A., & Impett, E. A. (2018). What theories and methods from relationship research can contribute to sex research. Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 540–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1421608

- Muise, A., Stanton, S. C. E., Kim, J. J., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Not in the mood? Men under- (not over-) perceive their partner’s sexual desire in established intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(5), 725–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000046

- Müller, B., Nienaber, C. A., Reis, O., Kropp, P., & Meyer, W. (2014). Sexuality and affection among elderly German men and women in long-term relationships: Results of a prospective population-based study. Public Library of Science, 9(11), e111404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111404

- Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., Bellavia, G., Griffin, D. W., & Dolderman, D. (2002). Kindred spirits? The benefits of egocentrism in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.563

- Offman, A., & Matheson, K. (2005). Sexual compatibility and sexual functioning in intimate relationships. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 14(1–2), 31–39. https://search.proquest.com/docview/220809399?accountid=14699

- Orr, J., Layte, R., & O’Leary, N. (2019). Sexual activity and relationship quality in middle and older age: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (Tilda). The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(2), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx038

- Pascoal, P. M., Narciso, I., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people’s definitions. Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.815149

- Sandberg, L. (2013). Just feeling a naked body close to you: Men, sexuality and intimacy in later life. Sexualities, 16(3–4), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713481726

- Schick, V., Calabrese, S. K., & Herbenick, D. (2014). Survey methods in sexuality research. In D. L. Tolman & L. M. Diamond (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology: Vol. 1. Person-based approaches (pp. 81–98). American Psychological Association.

- Schul, Y., & Vinokur, A. D. (2000). Projection in person perception among spouses as a function of the similarity in their shared experiences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(8), 987–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002610008

- Sinclair, V. G., & Dowdy, S. W. (2006). Development and validation of the Emotional lntimacy Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 13(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1891/jnum.13.3.193

- Strassberg, D. S., & Lowe, K. (1995). Volunteer bias in sexuality research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541853

- Štulhofer, A., Buško, V., & Brouillard, P. (2010). Development and bicultural validation of the New Sexual Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Sex Research, 47(4), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903100561

- Štulhofer, A., Ferreira, L. C., & Landripet, I. (2014). Emotional intimacy, sexual desire, and sexual satisfaction among partnered heterosexual men. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2013.870335

- Štulhofer, A., Jurin, T., Graham, C., Janssen, E., & Træen, B. (2020). Emotional intimacy and sexual well-being in aging European couples: A cross-cultural mediation analysis. European Journal of Ageing, 17, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00509-x

- Štulhofer, A., Hinchliff, S., Jurin, T., Carvalheira, A., & Træen, B. (2019). Successful aging, change in sexual interest and sexual satisfaction in couples from four European Countries. European Journal of Ageing, 16(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0492-1

- Sutherland, S. E., Rehman, U. S., Fallis, E. E., & Goodnight, J. A. (2015). Understanding the phenomenon of sexual desire discrepancy in couples. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 24(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.242.A3

- Træen, B., Stulhofer, A., Janssen, E., Carvalheira, A. A., Hald, G. M., Lange, T., & Graham, C. (2019). Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1256-x

- Waite, L. J., Laumann, E. O., Das, A., & Schumm, L. P. (2009). Sexuality: Measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the national social life, health, and aging study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Science, 64B(1), i56–i66. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp038

- Willoughby, B. J., Farero, A. M., & Busby, D. M. (2014). Exploring the effects of sexual desire discrepancy among married couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0181-2

- Witting, K., Santtila, P., Varjonen, M., Jern, P., Johansson, A., von der Pahlen, B., & Sandnabba, K. (2008). Female sexual dysfunction, sexual distress, and compatibility with partner. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(11), 2587–2599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00984.x

- World Health Organization. (2001). Health and ageing: A discussion paper, preliminary version. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66682

Appendix A.

Wording and construction of the variables used in the actor–partner interdependence model