ABSTRACT

While researchers have thoroughly studied the who, what, and when of first sexual experiences, we know much less about how people construct, experience, and proceed (or not) with sexual pleasure in these experiences and beyond. To address this knowledge gap, the Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing (GAB) coordinated a rapid review of published peer-reviewed research to determine what is currently known about sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences. We found 23 papers exploring this subject and its intersections with sexual health and sexual rights. The results reveal significant gaps in erotic education, gender equity, vulnerability and connection, and communication efficacy; and highlight important domains to consider in future research. Our findings draw out the key features of pleasurable first sexual experience(s), namely that individuals with the agency to formulate their definition and context of what pleasure means to them are more likely to experience pleasure at first sex. This finding points to promising ways to improve first sexual experiences through erotic skills building and through addressing knowledge gaps about having sex for the first time among disadvantaged groups.

Introduction

An individual’s first sexual experiences can be events imbued with great social, cultural, and personal significance; however, this is not always the case – they can also be unremarkable, nondescript, or banal (Carpenter, Citation2001; Smiler et al., Citation2005). In this paper, we define “first sexual experience” as the first time a person has a sexual experience with a partner, whether as an adolescent or adult. We employ an inclusive framing of “sex” that accounts for diversity in sexualities and physiologies and does not limit sexual experience to practices that include or culminate in penile-vaginal intercourse (Hawes et al., Citation2010; Henderson et al., Citation2002). Educational, public health, and sexology practitioners, along with other researchers, have paid much attention to this topic because early-onset and negative first sexual experiences have been constructed as markers of vulnerability tied to short- and long-term health and sexual behavior risks (Higgins et al., Citation2010; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013). This focus is amplified by the fact that, for some young people, their first time having sex is forced or coerced (Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2005). It is commonplace that young women, in particular, have negative first sexual experiences; hence, the narrative around first sexual experience tends to focus on prevention and minimization of risk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2012; Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Garcia-Moreno et al., Citation2005; Holland et al., Citation2000; Reissing et al., Citation2012; Sawyer & Smith, Citation1996; Thompson, Citation1990).

The descriptive characteristics of first sexual experiences, such as the age(s) at which individuals first have sex and socio-demographic characteristics associated with occurrence have been thoroughly examined; however, there has been little research on whether and how people experience pleasure during their first sexual encounter (Higgins et al., Citation2010). The research presented here was motivated by the World Association of Sexology’s definition of sexual pleasure, and the desire to contribute to the implementation of a holistic, rights-based, approach to erotic justice that accounts for structures of power and intersectionality. In this vein, we define sexual pleasure as:

…the physical and/or psychological satisfaction and enjoyment derived from solitary or shared erotic experiences, including thoughts, dreams, and autoeroticism. Self-determination, consent, safety, privacy, confidence, and the ability to communicate and negotiate sexual relations are key enabling factors for pleasure to contribute to sexual health and wellbeing. Sexual pleasure should be exercised within the context of sexual rights, particularly the rights to equality and non-discrimination, autonomy and bodily integrity, the right to the highest attainable standard of health and freedom of expression. The experiences of human sexual pleasure are diverse and sexual rights ensure that pleasure is a positive experience for all concerned and not obtained by violating other people’s human rights and wellbeing. (Global Advisory Board (GAB), Citation2016).

This definition shows the intersection of sexual pleasure with sexual rights and sexual health through self-determination, consent, safety, privacy, and communication with partners (Gruskin et al., Citation2019). Moreover, pleasure is not singular or static but transforms depending on context and experience over the life course.

Historically, there has been a knowledge gap about the ways sexual pleasure is tied to sexual health (Ford et al., Citation2019; Gruskin et al., Citation2019), a concept that Higgins (Citation2018) aptly called the “pleasure deficit” in sexual health research and programming (Dixon-Mueller, Citation1993; Higgins, Citation2018). More recently, there is evidence that sexual pleasure plays a significant role in promoting contraceptive and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use (Higgins, Citation2018). Moreover, there is growing evidence to suggest that pleasure-focused sex education can improve self-esteem and health behaviors (Hanbury & Eastham, Citation2016; Schalet, Citation2009; Scott-Sheldon & Johnson, Citation2006; Singh et al., Citation2020). Yet what we know about pleasure in first sexual experiences and our understanding of what shapes it has yet to be brought together. In this paper, we aimed to fill this gap by synthesizing what is known about sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences.

Method

To assemble the evidence on pleasure in first sexual experiences, we have used a rapid review methodology. Rapid reviews synthesize evidence by simplifying the rigorous components of the systematic review process to produce information in a timely manner (Tricco et al., Citation2015). We selected this methodology as it is particularly useful for maximizing the systematic capture of relevant information and examining new or emerging research topics where there are restrictions on timing and staffing (Tricco et al., Citation2015). As no standardized methods for conducting rapid reviews exists, we have adopted the Tricco et al. (Citation2017) framework that consists of the following steps: needs assessment, topic selection and refinement, protocol development, literature search, screening and study selection, knowledge synthesis, and reporting the findings.

Needs Assessment and Topic Refinement

To better understand their consumers’ needs, Reckitt Benckiser (RB), the maker of Durex, conducted research on “First Timers” to collect narratives relating to sexual discovery and people losing their virginity across sexual orientations. They analyzed a quarter of a million (269,000) public online conversations from the US, UK, Brazil, China, and Russia related to “virginity loss’” in an attempt to better understand young adults’ transitions to sexual activity and ensure their experiences are more pleasurable (Brandwatch Research Services, Citation2019). This study found that many respondents recounted negative first sexual experiences. To respond to these findings, the Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing (GAB), an independent group established by RB that advocates for policy and programming attention to sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure, decided to coordinate a rapid review of the existing literature about first-time sexual experiences to discover the breadth and depth of experiencing pleasure, or lack thereof, in sexual initiation. This work was intended to augment the original survey findings and support taking these findings forward.

Protocol Development

Two of the authors, VB and KQW, developed and shared a protocol with GAB for review and input before undertaking the research (see Supplementary Material).

Literature Search

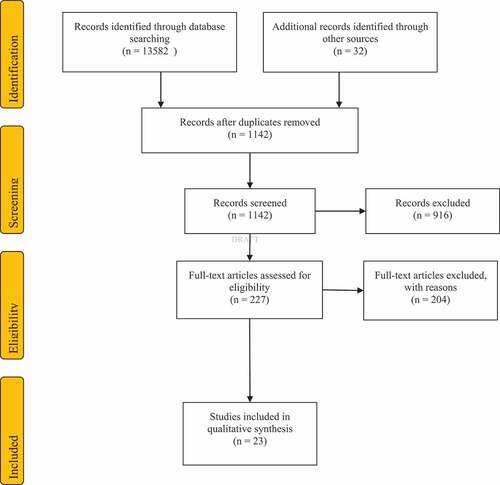

To identify and validate the search terms, we reviewed existing literature on pleasure, with a focus on Higgins and Smith’s (Citation2016) paper, which conceptualizes pleasure as a component of health. We additionally worked with sexual educators, researchers, and GAB members to verify the search string terms. We undertook key term searches in designated databases, including PUBMED, CINAHL, Cochrane, Family Welfare Studies, PyschInfo and Web of Science. We purposefully used an inclusive definition of first sexual experiences that considers diverse sexualities, genders, and bodies and is not limited to penile-vaginal intercourse (Carpenter, Citation2001; Hawes et al., Citation2010; Henderson et al., Citation2002). We intentionally did not focus on “virginity loss,” as historically researchers of the topic have tended to focus on vaginal intercourse primarily among people who identify as heterosexual. We included articles that had a term for sexual debut in the title, retrieved from the Scopus and SocIndex databases, but we did not run the full search terms in these databases as there were too many irrelevant hits. We combined a set of terms to indicate sexual debut and pleasure using Boolean search methods and applied these full strings to all fields in the included databases (except for SocIndex and Scopus, in which we only searched the title). The search terms and their variants are detailed in . These returned hits (n = 13,614) were restricted to manuscripts published between 1990 and May 2020 and were limited to abstracts, papers, and reports in English. The returned hits on our designated search strings were downloaded into Endnote for each database, with the duplicates then removed via Endnote’s de-duplication function (n = 1,142 were retained). We then downloaded these records to an Excel spreadsheet with automated reviewer drop-down categories for data abstraction.

Table 1. Search strings

Screening and Study Selection

To select the included papers, all three reviewers (VB, KQW, and RDS) conducted one-third of the title and abstract screening to assess the papers for inclusion, using a set of standard inclusion criteria. The reviewers co-reviewed approximately 50 records to ensure concordance in the inclusion of records, before continuing with the full review. The remainder of the records were screened by individual reviewers to produce rapid results. These inclusion criteria required the title and abstract to contain language and reference to (1) first sexual experience and (2) sexual pleasure. This process yielded a smaller database for full paper review by one author (n = 227 for full paper review). RDS reviewed the full papers for inclusion and abstracted data from the included papers into a standardized Excel spreadsheet. VB and KQW additionally read the included papers from the full paper screening before writing the paper. We retained twenty-three papers from the full paper review. See for PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram (Khangura et al., Citation2012)

Knowledge Synthesis

For data extraction, RDS reviewed the full paper for each record included in the full paper review and conducted a complete data abstraction of included studies (VB and KQW conducted several of these abstraction activities; however, RDS conducted the majority). All papers included in this final screening were abstracted using a standard data extraction form in Excel. The categories for data extraction include (1) definitions of sexual pleasure used in the included studies, (2) definition of first sexual experience, (3) study objective, (4) study design, (5) results/findings, (6) how sexual pleasure is addressed, (7) authors’ recommendations and (8) methodology (e.g., qualitative/quantitative). It is not typical for reviews that use any kind of “systematic” or “routinized” approach to have a theoretical approach, as the review is designed to explore what others have done regardless of the authors’ orientation; hence, the review was exploratory in nature and was designed to capture and synthesize a range of theoretical perspectives, rather than test a hypothesis or theory.

Addition of Missing Literature on “Virginity Loss”

We had initially avoided the term “virginity loss” in our search as this focuses on heteronormative penile-vaginal penetration; however, because of this approach, some key studies were excluded. We therefore ran a second search using the same search terms but including “virginity loss” that resulted in an additional 32 unique records, which were then reduced to 15 based on the review of the title and abstracts. The full paper review resulted in 10 additional papers being included. In total, these combined searches found 1,142 papers. From these, 227 records were included for a full paper review, with 23 papers subsequently retained.

Results

The results are presented in two parts: first, we detail the challenges in studying the determinants of sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences; and then we examine these determinants is more detail. The online supplementary documents include a table of summary data about each of the studies included in this review.

Description of Studies

The rapid review found 23 studies on sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences. Eight studies were published between 1990–2000; four were published between 2000–2010, and five were published between 2010–2020. The majority of studies were quantitative–16 papers – alongside six qualitative studies and one mixed-method study. The majority of these studies were conducted in high-income (18) and upper-middle-income countries (3).

Many of the studies included in this rapid review (10 of 23) involved quantitative, cross-sectional, retrospective surveys or questionnaires completed by women and men at high schools or colleges in North America or Europe at predominantly White (Caucasian) institutions (Higgins et al., Citation2010; Ishii-Kuntz, Citation1990; Katz & Schneider, Citation2015; Reissing et al., Citation2012; Sawyer & Smith, Citation1996; Schmidt et al., Citation1994; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996; Trotter & Alderson, Citation2007; Weinberg et al., Citation1995). An additional two studies met all the criteria above but restricted their sample to either men or women (Davidson & Moore, Citation1994; Santtila et al., Citation2009). To varying degrees, the studies that included both women and men discussed the implications of the gender context(s) in which they collected their data. However, except for several qualitative studies, the consideration of gender scripts rarely extended beyond perfunctory considerations of potential physiological, psychological, or social differences.

Five studies were conducted in the global south: Nicholas and Tredoux (Citation1996) cross-sectionally interviewed Black South African university students; Osorio et al. (Citation2012) conducted an extensive cross-sectional survey among high school students in the Philippines, El Salvador and Peru; Valencia et al. (Citation2015) conducted a theory-driven qualitative thematic analysis of Colombian undergraduate students’ biographic life stories; Marvan et al. (Citation2018) conducted a cross-sectional survey among public high school students in Xalapa, Mexico; and Delgado-Infante and Ofreneo (Citation2014) conducted a feminist analysis of memory narratives in the Philippines.

Several remaining studies consisted of qualitative interviews and narratives, only sometimes describing a theoretical or analytic framework. For instance, in Holland et al.’s (Citation2000) analysis of young men and young women participating in an AIDS prevention project, the authors present an (assumed) critical feminist analysis of these data without explicitly indicating this as a theoretical orientation. This issue was not limited to the included qualitative papers; out of all of the included papers, only three papers explicitly described a theoretical framework that guided their data collection and analysis (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Santtila et al., Citation2009; Valencia Molina et al., Citation2015)

The remaining three papers consist of two using historical Kinsey datasets (a non-representative sample in the US derived from Alfred Kinsey’s pioneering sexology work) (Rind, Citation2017; Rind & Welter, Citation2014) and one using a cross-sectional online survey, with follow up in-depth written narratives to examine women’s experiences of anal sex (Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013). None of these samples could be considered longitudinal panel data, where the same respondents are followed up over time. Instead, most participants retrospectively reported on their first sexual experience while completing questions on other variables. This is a significant limitation, particularly as many of the authors of the included studies have articulated sexual initiation as a process rather than as a singular event. Prospective studies such as case diary methods could allow researchers to examine the processes and complexities of sexual debut and the development of a pleasure-feeling self in ways that cross-sectional or retrospective data cannot.

An additional critique of the quantitative studies included in this rapid review concerns potential sampling bias in study samples. Sixteen of the 23 included studies collected data from high school or college students. In particular, college students are a biased sample to draw from as they represent different levels of social class and other socio-demographic characteristics than the general population. Thus, the resulting overall view of pleasure during first sexual experience should be talked about as primarily a view of White, middle- to upper-class, heterosexual, educated respondents.

Most of these studies are presented in journals representing the fields of sexology, psychology, or education. There are diverse standards for analysis across different fields of study, and these fields are no exception. Very few of the included quantitative studies carried out multivariate analyses of sexual pleasure during the first time having sex. Not controlling for important socio-demographic and context variables makes the findings in these studies less robust. Additionally, across many of the included studies, pleasure – or a proxy for it – was not included as the primary variable of interest. Instead, we have obtained estimates and associations between first sexual experiences and pleasure because the reviewed studies included these variables to estimate some other outcome, including “sexual dysfunction”, current sexual satisfaction, and reasons for initiating sex. The overall tendency of the included studies to polarize measures and reinforce sexual and pleasure binaries means that only a few studies recognized the complexity and nuance that characterizes first sexual experiences.

Complexities in Studying Sexual Pleasure in First Sexual Experiences

In the papers reviewed, we found that the ways respondents and authors defined first sexual experiences and pleasure or lack thereof were multiple, complex, and socially constructed. A reflection, and a consequence, of the heterogeneous meanings and their applications, is a distinct lack of consistency in how terms like first sexual experience and sexual pleasure were used in the included studies. This lack of consistency hampers the development of meaningful definitions that inform research, policies, and programs. Consequently, affecting the generation of evidence can offer comparable insights into sexual pleasure during people’s first sexual experiences. Consistent definitions and measures allow for meaningful study of social phenomena; however, they can also be culprits in reifying rigid social definitions of acceptable or unacceptable pleasure or sex. Thus, efforts to create standard or consistent measures to improve policies or education should be informed by grounded definitions of first sexual experience and pleasure in their myriad forms. Most papers detailed multiple determinants for pleasure in first sexual experience but used different definitions for similar phenomena; for example, socio-economic determinants were sometimes analyzed as “contextual” factors. In other cases, these were included in a paper’s final analysis as a unique determinant. Given the diversity of meaning, we cannot expect a rigid standardization in how key constructs are defined and measured, yet some points of commonality would greatly facilitate cross-comparison and more generalizable learnings.

First sexual experiences are more than just one thing.

Most of the papers we have reviewed referred to a person’s first sexual experience as a singular, one-off event (e.g., first-time penile-vaginal, oral, or anal sex) and only two discussed it as a psycho-social process (e.g., the transition to a sexual identity). There is a historical tendency for research on this topic to focus on first-time penile-vaginal penetration and erase LGBTQ+ identities (Averett et al., Citation2014: Carpenter, Citation2001). This is reflected in our review, where 17 out of the 23 papers focused on penile-vaginal intercourse, either directly defined or implied as the default definition of first sexual experience (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Davidson & Moore, Citation1994; Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Higgins et al., Citation2010; Holland et al., Citation2000; Marvan et al., Citation2018; Nicholas & Tredoux, Citation1996; Osorio et al., Citation2012; Reissing et al., Citation2012; Rind & Welter, Citation2014; Santtila et al., Citation2009; Sawyer & Smith, Citation1996; Schmidt et al., Citation1994; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996; Valencia et al., Citation2015; Weinberg et al., Citation1995).

Several authors did study multiple sexual activities and different kinds of “first times.” While most studies in this review implicitly referred to heterosexual penile-vaginal penetration, several also referred to the “first” experience of other sexual behaviors (e.g., oral, anal, same-sex experiences or “coming out”) (Ishii-Kuntz, Citation1990; Rind & Welter, Citation2014; Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013). Moreover, Trotter and Alderson (Citation2007) found that college students reported ambiguity regarding what “having sex” meant to them – for example, “having sex” could range from penile-vaginal intercourse to oral intercourse to anal intercourse; however, their respondents defined “virginity loss” much more stringently as penile-vaginal intercourse, with a small minority defining first-time penile-anal intercourse in this way. Stulhofer and Ajdukovic (Citation2013) examined experiences of first anoreceptive sex for heterosexual women. Rind (Citation2017) examined first same-sex contact among women, defined as oral sex, body contact, masturbation, or petting. Ishii-Kuntz (Citation1990) and Thompson (Citation1990) included respondent-defined same-sex intercourse in their studies.

(ii) People use the term “sexual pleasure” in different ways

In the included studies, the authors defined and captured sexual pleasure in different ways. By implication, these differences mean that sexual pleasure as a singular outcome is not comparable across the studies examined. Some authors have measured pleasure using pre-determined categories that study participants’ self-reported on, without providing a clear definition of pleasure (or sometimes lacking one at all), furthering the lack of comparability between studies. Within the included studies, the most common phrases used to define sexual pleasure were: “satisfaction” (this could be sexual, psychological, or physiological), enjoyment, happiness, or affective negative and positive reactions to first sexual experience (Davidson & Moore, Citation1994; Higgins et al., Citation2010; Ishii-Kuntz, Citation1990; Nicholas & Tredoux, Citation1996; Reissing et al., Citation2012; Rind, Citation2017; Rind & Welter, Citation2014; Santtila et al., Citation2009; Sawyer & Smith, Citation1996; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013; Weinberg et al., Citation1995). Participants often responded to these measures by stating how much they agreed with the statement on a Likert scale or by answering dichotomous questions with yes/no or agree/disagree responses. One trend in these studies was a move toward the use of valid scales, development of potential new scales, and expanded response categories as time has progressed. The authors of these studies rarely operationalized pleasure beyond concepts like satisfaction, enjoyment, or happiness to identify which aspects of a person’s first time were pleasurable, and often uncritically equated satisfaction with pleasure without explaining where their definitions of pleasure came from.

In the studies reviewed, most definitions of pleasure have been operationalized in how they are measured, and these tend to be defined by researchers, not by respondents. Thompson’s (Citation1990) older qualitative research found that respondents differently interpreted categories used by researchers to assess affective reactions. For example, Thompson found that the term “pain” did not necessarily signify a negative response, but rather, enduring “pain” could on occasion confer positive meanings, such as courage.

An additional set of authors asked respondents about pleasure indirectly by gauging their reasons for engaging in their first sexual experience (Osorio et al., Citation2012; Schmidt et al., Citation1994; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996). The respondents in these three studies all expressed “sexual arousal” as one reason for starting to engage in sex, often along with measures of peer pressure. These authors generally found little to no relationship between the reason for sexual initiation being arousal and any covariates; however, along with others, they emphasized how their young adult respondents focused on themes of intimacy and closeness, a tendency becoming more prominent in research over time.

Additionally, several (qualitative) studies used grounded definitions of pleasure that emerged from the data itself. None of these studies routinely asked for respondents to define and identify pleasure; rather, this emerged either within thematic narratives or through the authors generating analytic themes to highlight different types of relationships between pleasure, heteronormativity, and agency (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2000; Thompson, Citation1990).

Many studies asked their respondents about regret, guilt, or embarrassment (Ishii-Kuntz, Citation1990; Weinberg et al., Citation1995), pain (Marvan et al., Citation2018; Rind & Welter, Citation2014; Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013) and “emotionally negative” reactions or consequences after first sexual experiences (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Marvan et al., Citation2018; Rind, Citation2017; Rind & Welter, Citation2014). In these studies, the focus on positive or pleasurable experiences was in opposition to or in the absence of negative experiences, such as shame, guilt, and regret. For example, two studies used the First Coital Affective Reaction Scale (FCARS) to measure participants’ responses to a series of “positive” descriptions of their first time (including terms like “happy”, “excited”, “romantic”, “satisfied”, and “pleasure”) and “negative’ descriptions of it (including items such as “confused”, “anxious”, “guilty” and “embarrassed”) (Reissing et al., Citation2012; Santtila et al., Citation2009). These “positive” and “negative” characteristics were then grouped and used to predict outcomes of interest in the studies, suggesting that positive and negative experiences consist of uniform experiences.

Moreover, several groups of authors indicated that emotional reactions to different sexual activities were mixed and contained both positive and negative elements (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2000). This ambivalence may be part of some first sexual experiences, where both happiness and anxiety about performing a novel behavior coincide. In Caron and Hinman’s (Citation2013) study of men’s and boys’ “virginity loss” involving a sexually experienced (so-called “non-virgin”) woman with an inexperienced (so-called “virgin”) man, about a third of the stories were coded as awkward: neither positive nor negative experiences, but something odd or unique.

The Impact and Determinants of Sexual Pleasure in First Sexual Experiences

Accounts of impacts of sexual pleasure in first sexual experience

Five of the studies we reviewed suggested that pleasure is a motivating concept for having sex for the first time (Osorio et al., Citation2012; Schmidt et al., Citation1994; Thompson, Citation1990; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996; Valencia et al., Citation2015). Specifically, the authors of these studies suggested that pleasure or arousal was a significant motivator for young adults, who evaluated their first times in a variety of positive, neutral, and negative ways that speak to the complexity and realities of sex. We can make a few observations by tracking the positive and pleasurable terms across the papers (e.g., excitement, arousal, pleasure, satisfaction, curiosity, desire and happiness). Traeen and Kvalem, (Citation1996) found that sexual arousal motivated their respondents to have sex their first time as did Osorio et al.’s (Citation2012), Schmidt et al.’s (Citation1994), Valencia et al.’s (Citation2015). Thompson’s (Citation1990) qualitative studies pointed to how people found their first sexual experiences as moments of personal and social significance, with the former finding that individuals’ first time were unique and memorable despite reported discomfort and risks. This echoes sentiments across other work that adverse experiences do not automatically negate pleasure. Rather, the studies suggest that people’s first sexual experiences are complex moments when young people crave intimacy, arousal, social standing, pleasure, and adulthood; however, where they find these things, they also frequently encounter guilt, pain, embarrassment, and regret.

Several authors have found associations between people’s first sexual experiences and their later sexual life. For example, Valencia et al. (Citation2015) and Reissing et al. (Citation2012) indicate that reports of pain and trauma during a first sexual experience were related to later development and performance in people’s sexual lives. Similarly, Katz and Schneider’s research (Katz & Schneider, Citation2015) suggested that women’s emotional discomfort during their first time having sex was associated with less sexual self-efficacy in the future. Smith and Shaffer’s (Citation2013) cross-sectional study of “virginity loss” found that participants with more positive first-time sexual experiences (e.g., higher reported intimacy and respect) reported greater feelings of sexual satisfaction and sexual esteem later in life. Reissing et al. (Citation2012) offered a more nuanced life course perspective, suggesting that the emotional responses during the first time having sex, both negative and positive, are continuously negotiated and reinforced over time and mediated through ongoing sexual practices and perceptions of sexual self-efficacy and sexual aversion. Reissing et al. (Citation2012) highlighted how, amongst heterosexual university undergraduates, the ability to effectively mediate emotional responses to first sexual encounters is not wholly in the control of an individual but correlates with a person’s favorable socio-economic conditions.

(ii) Determinants of sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences

Many authors attempted to identify the factors correlated with a positive or pleasurable first sexual experience. In the following section, we outline four common correlates we found in this review: gender, age, the circumstances of the first sexual experience, and consent.

Gendered Difference in Pleasurable First Sexual Experience

A unanimous finding across the included studies was that there are gendered determinants of the experience of pleasure when people first start having sex. The authors of the included studies demonstrated that pleasure is influenced by gender norms, which tend to be tied to heteronormative and misogynistic biases. The cultural expectations surrounding one’s first sexual encounter are often consistent with double standards in sexual scripts, in which men’s sexual behavior is judged by different standards than women. Across the included studies, boys or young men often reported a more positive or pleasurable first time than girls or young women (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Higgins et al., Citation2010; Holland et al., Citation2000; Katz & Schneider, Citation2015; Marvan et al., Citation2018; Reissing et al., Citation2012; Rind & Welter, Citation2014; Schmidt et al., Citation1994; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013).

The first sexual experiences of boys or young men themselves were often characterized as predominantly positive, pleasurable, and empowering rites of passage in which the stigma of “virginity” was lost (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Holland et al., Citation2000). Specifically, boys or young men reported higher levels of physical and psychological satisfaction than girls and young women (for example, see Higgins et al., Citation2010). The main driver of increased pleasure during the first time boys or young men had sex was when they were able to embody a role that fulfilled normalized, sexist, gender dynamics (Marvan et al., Citation2018). The pleasure derived from fulfilling hegemonic gender roles was most common when those boys or young men reported feeling that they occupied a dominating role that allowed for the expression of sexist or “macho” qualities (Marvan et al., Citation2018).

When boys or young men in the reviewed studies did not report pleasure the first time they had sex, the authors often interpreted this response as being due to the inability to fulfil normative sexist gender roles. For example, when men had less sexual experience than their partners, this lack of experience often put their partner in a dominating position that was subsequently less pleasurable for the men (Marvan et al., Citation2018). In Caron and Hinman’s (Citation2013) qualitative interview study, the authors observed that the toxic masculinity of sexist gender roles can create feelings of embarrassment, shame, and emasculation in relation to men and boys’ perceived “virginity” status leading up to their first sexual encounter. While boys or young men may derive pleasure from normalized sexist gender roles in the actual moment itself, it is also the case that leading up to the event and following it, many experience nervousness, disappointment, awkwardness, pressure, anger, or regret (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013).

Finally, it is important to note that the weight of normative gender roles on boys’ or young men’s pleasure in their first sexual encounters in these studies also depended upon local conceptions of gender roles. For example, a comparative qualitative survey of undergraduate US and Swedish students found that US men reported significantly less guilt than Swedish men if they were not in a relationship with the partner with whom they first had sex with (Weinberg et al., Citation1995). The authors suggested that, in Sweden, where egalitarian gender policies are more frequently implemented than in the US, these ideologies may play a role in this finding (Weinberg et al., Citation1995). Further, findings across studies also suggest that adolescent boys seek intimacy, closeness, and fidelity in the first time they have sex, yet these desires are underplayed when their encounters are mediated by heteronormative and misogynistic gender dynamics.

In contrast, girls’ and young women’s first sexual experiences are often reported as negative, including reports of shame, pressure, physical pain, regret, and guilt about their experience (Reissing et al., Citation2012; Sawyer & Smith, Citation1996). Sexist gendered norms create double-bind dynamics where girls or young women are expected to actively negotiate the meaning of their first sexual encounter for themselves in ways that fulfil their desired sexual agency, pleasure, and empowerment, alongside playing passive roles in fulfilling male scripts of dominance (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2000; Thompson, Citation1990). If girls or young women are unable to negotiate meanings for themselves that are empowering and agential, they are less likely to experience pleasure the first time they have sex. Compared to boys or young men, girls or young women are less likely to experience their first sexual encounter as a “milestone” or “accomplishment” which leads to more frequent questioning of why they chose to start to have sex when they did and with whom. Further, (non-panel) longitudinal studies suggest that these sexist expectations of girls or young women worsened between the 1970s and 1990s, with an increase in the number of women reporting unpleasurable first sexual experiences in select contexts (Schmidt et al., Citation1994). Thompson’s (Citation1990) study in the UK has noted that the decrease in pleasure in girls’ and young womens’ first sexual encounters can be related to increased media portrayals of a woman’s sexual and gendered validity as being passive participants in sexual encounters, particularly initial ones.

For women, first sexual experiences tend to be less positive and pleasurable due to the complex negotiations needed to satisfy normalized gender expectations (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2000; Thompson, Citation1990). Indeed, authors have commonly reported that girls or young women attempt to mediate the gendered norms surrounding the first time they have sex by viewing it as an affective experience: specifically, in the context of love and connection. In other words, when there are affective ties and emotional factors, girls and young women are more likely to have positive experiences, or at least the absence of negative ones (e.g., pleasure, or an experience with a lack of regret or pressure) (Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013; Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996; Weinberg et al., Citation1995). Across all studies, it can be observed that there is some association between intimacy and sexual satisfaction for both men and women.

Despite the significant role of gender in determining pleasure in first sexual experiences that many authors demonstrated, Sawyer and Smith (Citation1996) have suggested that both genders’ physical and emotional satisfaction during their first sexual encounters are mediocre, at best, which suggests that the determinant of gender alone does not exclusively explain pleasure in first sexual experiences.

Role of Age in First Sexual Experiences

The studies included in this review provide mixed evidence on the relationship between respondents’ age and their experience of pleasure in their first sexual experiences; while some authors suggested that being older provides maturity, which helps individuals have a more pleasurable first time, others indicate that a younger age also correlates with a pleasurable first time.

Some studies found that older age had a positive impact on experiencing pleasure within first sexual encounters. One survey utilizing Likert scales suggested that older students (16 and older) feel more “cheered up”, better about themselves, and more attractive after first-time sex, while younger students (16 and younger) reported more regret (Marvan et al., Citation2018). Reissing et al. (Citation2012) also found that younger respondents in an 18–29-year-old respondent group had less positive experiences and more regret. Further, Higgins et al. (Citation2010) found that for young people between 18 and 25, an increased age at first heterosexual/penile-vaginal intercourse was associated with psychological satisfaction among White women. However, in their profile of Black South African university students, Nicholas and Tredoux (Citation1996) reported that participants who started having sex earlier reported greater satisfaction at ages 15 and younger.

These results suggest that age is not a conclusive determinant in the experience of pleasure at the first sexual encounter. The background papers used to supplement this review also revealed that a focus on chronological age neglects individual differences in physical and psychological maturity, and rather than chronological age, we should focus on individuals’ readiness to have sex for the first time and the appropriateness of the timing (Carpenter & Garcia, Citation2007; Hawes et al., Citation2010). Further, Trotter and Alderson (Citation2007), included in this review, emphasized that if an individual understands what sex “means” to them, this more accurately indicates their readiness for a sexual debut than age. As such, the use of “age” as a determinant of pleasure in first sexual encounters should not always be viewed chronologically but should focus on whether the individual is able to make sense of starting to have sex within their social and psychological world.

Time, Place, and Circumstance

Many authors pointed out that the immediate circumstances in which a first sexual encounter happens influences the experience of pleasure within it. The conditions identified in this review include whether an initial sexual experience took place within the context of a relationship, the extent of prior positive parental communication, and the time and location of the sexual event itself. Importantly, these specific circumstances are often mediated by gendered determinants.

Several authors indicated that the quality of direct personal relationships with a sexual partner influences whether the first sexual encounter is pleasurable. For example, Higgins et al. (Citation2010) revealed that their participants’ first times were reported as more positive when they happened with a partner or within an established relationship, with this particularly being the case for women. Further, Weinberg et al.’s (Citation1995) survey comparing university students in the US and Sweden demonstrated that more of the women in Sweden reported significantly higher levels of happiness in their first sexual encounters than their US counterparts, specifically because they were more likely to be in relationships (91% vs. 65%). The authors suggested participants’ relationships provided their partners with affective ties that increased pleasure during the first time they had sex. This is reflected by findings from the other included studies that young women and girls were more likely to have positive experiences, or at least an absence of negative ones, (e.g., pleasure, no regret and no pressure) when there were affective ties and emotional factors in place (Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013; Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996; Weinberg et al., Citation1995).

However, Thompson (Citation1990) suggested that it is not the relationship’s affective ties alone that determine pleasure; instead, the affective ties of a relationship are more often a product of an empowering context where, particularly for girls or young women, sexual partners are able to exercise intentionality, sexual self-expression, communication, and agency. In other words, the affective ties of relationships are more likely to empower girls or young women with agency to navigate harmful gendered norms often associated with sexual debuts.

Several authors described the importance of positive parental communication in supporting the development of agency and self-awareness that seems to play a large factor in experiencing a more pleasurable first sexual experience. Sex-supportive parental attitudes, characterized by having open, accepting, and sex-positive conversations, allow for topics such as safe sex practices and an understanding of what sex “means” to the individual within their specific circumstances to be addressed (Santtila et al., Citation2009; Thompson, Citation1990). Several qualitative studies, including a memoir analysis and a grounded theory analysis of interviews, refer to supportive conversations with parents before having sex for the first time; these studies suggested that this practice enables the individual to approach sex with curiosity, self-expression, exploration, sexual initiative, a knowledge of the right to say no, and an awareness of the right to their desire (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Thompson, Citation1990). Authors also highlighted that girls or young women who have had conversations with their parents before having sex for the first time were more likely to navigate and counter heteronormative sexual scripts associated with sexual debuts (Holland et al., Citation2000). Discussing sex with parents can help mediate sexist gendered environments where girls or young women are often unable to speak about their desires in the conversations leading up to and during their sexual debut. This is not to say that parental communication is the sole mechanism to empower individuals to reflect on what they think will happen when they first have sex, and what meaning they give to their first sexual encounter. However, the positive role that parental communication can play points more broadly to the need for individuals (of all genders) to have an open and accepting space free of heteronormative or misogynist social norms being forced upon them, thus enabling them to openly discuss their desires for sexual experiences and what they mean to them. Making this possible provides individuals with the skills needed to create a more comfortable context when they start to have sex.

Both the timing and location of first sexual encounters were also important circumstantial determinants of pleasure in the studies reviewed. For example, Thompson (Citation1990) described the timing of a first sexual experience as a fleeting moment that can often be unplanned: in one case, she gives an example of heterosexual friends who had ended up “pecking” throughout the night at a party, resulting in unplanned sex. Needing to be hasty when having sex for the first time is also associated with fear, lack of “foreplay” and little time to explore pleasure mutually (Valencia et al., Citation2015). Further, in the studies that captured the temporality of first sexual encounters, the participants characterized their experiences as “rushed”, “unexpected”, “surprising”, or as something that needs to be “done” to be gotten over with (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Thompson, Citation1990). Santtila et al. (Citation2009) suggested that when partners were intoxicated, this led to a less positive affective response among male college students. The studies that documented the timing and circumstances of first sexual experiences highlight how individuals are often unable to predict events before they happen and also emphasize the variety of contexts in which first sex may emerge. This unpredictability and contextual variety further points to the need for individuals to know what sex “means” to them so that they are able to adapt to unanticipated situations. When an individual has not had the opportunity to reflect on what they would like to happen when they first have sex, they are more likely to feel the influence of peer pressure, gendered social norms and heteronormative sexual scripts, and have more negative experiences overall (Santtila et al., Citation2009).

Sexual Consent in First Sexual Experiences

The papers we have reviewed contain much discussion about consent as a determinant of pleasure in first sexual encounters. Here, we define sexual consent as “two people being willing to and agreeing to have sex with one another” (Kennedy et al., Citationin press, p. 2). Consent is at the center of free and informed decision-making, which is a crucial component of the right to sexual and reproductive health. While consent is framed as an individual choice, we need to recognize that a person’s capacity to consent – and the actions they can consent to – are constrained or enabled by their social, cultural, and political context, including religion, age, sex, and ethnicity (Kennedy et al., Citationin press). An individual’s knowledge of their sexual interests and desires is seen as crucial in their ability to understand and perform sexual consent.

Thus, the ability to consent in a first sexual encounter often reflects the extent to which an individual has been provided with the time, space, and freedom to consider what sex means to them. Put candidly, Traeen and Kvalem (Citation1996) asked: “How can girls say no to intercourse if they have not learned to say yes?” (p. 300) Knowing what one wants sexually, the expectations around it, and what is being offered, enables all young adults to evaluate a situation and decide if they wish to consent (Thompson, Citation1990; Traeen & Kvalem, Citation1996).

When individuals did not have the opportunity to consider their sexual expectations, there was often confusion about whether they gave consent during their sexual debut. Drawing on interviews with 100 teenage girls, Thompson (Citation1990) documented how young women were unsure of how to distinguish between choice, coercion, voluntary, and involuntary sex. Further, Delgado-Infante and Ofreneo (Citation2014) reported finding ambivalence in women’s knowledge of whether they gave sexual consent in terms of both avoidance and recognition of sexual consent. Researchers in this area often either do not address consent explicitly or use concepts that blur the boundaries around consent. For example, in 2015, Katz & Schneider developed the term “sexual compliance” to capture respondents’ willingness to consent to an unwanted first sexual encounter. Davidson and Moore’s (Citation1994) study of never-married college girls also distinguished between verbal and implied consent to capture respondents’ accounts of agreeing to have sex for the first time. These examples point to a lack of understanding of what sexual consent is and how to exercise it to fulfil personal expectations about first times.

Where individuals in studies did not understand sexual consent and how to communicate it, it was commonly reported that their first sexual experiences was unpleasurable. A lack of consent was characterized by pressure, exploitation, compliance, and/or lack of control or agency in sexual debuts and was often associated with being female (Davidson & Moore, Citation1994; Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Katz & Schneider, Citation2015; Osorio et al., Citation2012; Thompson, Citation1990). Katz and Schneider (Citation2015) described how participants who described themselves as “complying” when they had sex for the first time reported more emotional discomfort from sex than those who did not. The feeling of pressure to have sex for the first time also had long-term effects and increased the odds of participants feeling pressure or a sense of compliance during their most recent sexual experience (Katz & Schneider, Citation2015).

To avoid unpleasurable first sexual experiences, it is important for individuals to understand consent and how to enact it. Delgado-Infante and Ofreneo (Citation2014) suggested that sexual agency, “the ability to recognize one’s sexual feelings or desires and to make choices and act upon these desires” (p. 391) is central to sexual consent. Further, Thompson (Citation1990) stressed how understanding consent should recognize that the contexts in which the consent takes place are mediated by unplanned, fleeting, and rapid experiences, as discussed in the section above. These findings then suggest that understanding and providing consent requires an understanding of one’s expectations and desires at sexual debut and how to communicate these (Delgado-Infante & Ofreneo, Citation2014; Holland et al., Citation2000; Thompson, Citation1990).

Discussion

In this review we set out to explore what is known about sexual pleasure in first sexual experiences. However, throughout the review process, we discovered a high degree of complexity surrounding first sexual experiences that makes pinpointing determinants of pleasure challenging. This finding is complicated by the fact that there are no consistent definitions of pleasurable first sexual encounters, and by the fact that existing research often neglects definitions based on people’s lived experiences.

We found that most of the studies included in our review were more focused on characterizing unpleasurable first sexual experiences than on what pleasure could look and feel like, the contexts that are more conducive to enabling pleasure, and examining how positive and pleasurable first times affect wellbeing. One issue was the lack of a clear definition of sexual pleasure and the slippage with other related concepts about satisfaction and orgasm. Several authors, who were not included in the above results due to not meeting inclusion criteria for the rapid review, offer important starting points to define a positive and pleasurable first sex. For example, Valencia et al. (Citation2015) provided an ideal situation in which: “A sexual debut is configured as a healthy transition when the sexual encounter is agreed upon by both members, when it is planned, takes place within a safe and carefree environment, and flows within the frame of symmetric relationships” (p. 362). Smiler et al. (Citation2005) argued that it is important to widen our perspective on first sexual experiences and recognize them as part of a broader growth of healthy and positive sexuality as a core developmental task of adolescence and early adulthood, rather than as exclusively “risky” experiences for sexual and emotional health. For Smiler et al. (Citation2005) “the emphasis is on safe, respectful, and informed consensual sex that typically occurs within the context of an ongoing relationship and addresses both partners’ desires and emotions (p. 41)” and “positive first coitus where the term positive refers to a sexual experience that is mutual, respectful, and empowering, and not simply risk-free” (p. 51). However, neither of these definitions refer explicitly to pleasure.

Smith and Shaffer (Citation2013), included in the above results, bring us closer to a definition by suggesting that a pleasurable first sexual experience should be marked by feelings such as afterglow (e.g., relaxation and contentment), a sense of connection to one’s partner (e.g., love and intimacy) and greater overall sexual functioning. Nonetheless, these definitions fall short of allowing for the complexity of what pleasure “means” to an individual when considering to have sex for the first time. The suggested definitions remain more conceptual in nature and are difficult to operationalize in terms of measurement. Recent work around “great sex” (albeit not in first sexual experiences) moves beyond looking at sexual function and satisfaction and provides concrete features of the optimal experience that may advance this thinking (Kleinplatz et al., Citation2009; Wampold & Luebbert, Citation2014). The key components identified included being present, connection, deep sexual and erotic intimacy, extraordinary communication, interpersonal risk-taking and exploration, authenticity, vulnerability, and transcendence (Kleinplatz et al., Citation2009).

The following discussion focuses on drawing out the key features of pleasurable first sexual experience(s) identified through this review, namely that individuals with the agency to consider what a pleasurable first sexual experience may mean to them experienced more pleasurable sexual debuts. While shifting gender norms could be an important factor for how future young adults sexually interact with each other, particularly in terms of power differentials and gender transgressions, the studies included in our review do not highlight these findings. Instead, we found that building erotic skills and addressing knowledge gaps about pleasurable first sex for socially disadvantaged groups were important features of pleasurable first sexual experience(s). These findings echo Malhotra et al.’s (Citation2019) commentary suggesting that catalytic change in gender norms for adolescent and sexual reproductive health has yet to be mainstreamed and will be most effective through enhanced investments in leveraging structural drivers of gender inequity.

Building Erotic Skills

Thompson (Citation1990) and Katz and Schneider (Citation2015) suggested that young people should be educated and supported to express and communicate their personal (dis)interest(s) in sex to contribute to more positive and pleasurable first sexual experiences. Explicit discussions about desire and pleasure in sexual debut may help young people understand what their expectations are for feeling comfortable, better assert their sexual interests, and refuse unwanted sex. These discussions provide ways for young people to understand what their sexual debut would “mean” to them and help provide the skills to create a pleasurable first sexual experience (Thompson, Citation1990). This self-knowledge and agency may be central to sexual confidence when first having sex, and could contribute to consent, acceptable timing, autonomous decision-making, and contraceptive protection (Palmer et al., Citation2017).

Several authors in the articles we reviewed suggested a need to focus on erotic skills in sexual education. Thompson (Citation1990) described this as education on “how to masturbate; how to come; how to respect another’s desire; how to bring another – of either gender – to orgasm; how to fuck; and it would include narrative exchange”. Other authors referred to the need for advice on “foreplay” or particular sexual acts, such as anal sex (Stulhofer & Ajdukovic, Citation2013; Valencia et al., Citation2015), knowing the type and length of simulation (Davidson & Moore, Citation1994), and learning how pleasure works (Holland et al., Citation2000).

Such erotic skills education has the ability to increase sexual confidence. As Reissing et al. (Citation2012) suggested: “The belief that one is a competent sexual partner is important to approach sexuality openly and expose oneself to other sexual experiences that have the potential to confirm further and increase sexual self-efficacy” (p. 34). Such information and education can relieve potential awkwardness, discomfort, and anxiety surrounding having sex for the first time, and could include building knowledge, attitudes, and practices around topics such as how to perform oral sex (Vasilenko et al., Citation2015), orgasming and not orgasming during different types of intercourse (Davidson & Moore, Citation1994) and general anxiety about sex (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013; Smith & Shaffer, Citation2013). A strong grasp of erotic skills, as suggested by the authors included in this review, would ultimately enable individuals to have more pleasurable sexual debuts and empower individuals to consider what “works” for them (Caron & Hinman, Citation2013). A caveat here is that we propose caution when considering erotic skill building that encourages a singular idea about the “right” way to do sex and suggest instead that researchers and professionals focus on “skills” that can be tailored to individual interests, feelings, and needs.

Further, supporting open conversation about sexual topics with friends, family, and confidantes may provide an opportunity to frankly discuss what a sexual debut would “mean” to an individual, how they want to make sense of the role of sex within their own life, and the circumstances that could lead to a more pleasurable experience. When having these conversations, supporting young people requires not following rigid algorithms of what the first time “ought” to be like; instead, this support must make room for and explicitly address how sexual debuts are often unexpected, fleeting, and rapid, as well as often being within the context of gendered sexual scripts. As Thompson (Citation1990) suggested, this requires encouraging and enabling individuals to actively think about their desires and the first time they have sex.

Existing sexual education often emphasizes the age of an individual when they start to have sex and on behaviors that are “risky” to sexual health. However, we found that the age of sexual debut is not always an accurate determining variable for a pleasurable first time. Rather, the “maturity” that chronological age claims to represent is more accurately expressed as knowing one’s expectations, having knowledge of what pleasure means for oneself, and possessing an idea of what the most conducive personal and social settings for those experiences could be. While many sex educators focus on reducing sexual health risks by encouraging condom use and knowledge of sexually transmitted infections, they often identify environments to avoid rather than those that may be conducive to a more pleasurable sexual debut.

While existing literature on negative first sexual experiences has allowed policymakers to identify environments to prevent sexual debut, a focus on pleasurable and positive first sexual experiences may provide policymakers with an insight into what types of education and what kind of contexts enable positive and pleasurable sexual debuts and what are the impacts on wellbeing. In other words, the translation of research on pleasurable first sexual experiences into policy does not necessarily only tell individuals what not to do, but can also empower them with skill sets to fulfil their desires in ways that safeguard their health (Ford et al., Citation2019). We recognize that the inclusion of pleasure in sex education is an ideal, or standard to strive for, as there are political, social, and moral barriers to doing so. However, pilot studies or further research on the benefits of erotic education may demonstrate not only sexual benefits but also relationship and psychological benefits.

Several studies not included in this review have also noted the potential benefit of explicitly focusing on pleasure within sex education. These findings show how pleasure has been historically associated with dangerous sexual health practices; however, directly “incorporating pleasure into sexual health education courses allows for sexual expression to be an acceptable part of adolescence” (Koepsel, Citation2016, p. 223) and is more likely to foster communication around safe and pleasurable experiences. When sex education focuses on pleasure and how it is not a fixed or normative entity, it can make space for the “differences in sexual expression” between individuals to be articulated (Koepsel, Citation2016, p. 221). Further, when open conversations about sexual pleasure occur, they enable adolescents to “interrogate where sexual stereotypes come from” (Koepsel, Citation2016, p. 223). This is particularly important for those who have experienced trauma, are from marginalized race and class backgrounds, are disabled, identify as asexual, or have gender identities beyond the heteronormative frame (Koepsel, Citation2016). Thus, a focus on pleasure moves away from disciplining individuals into normative ideas about how they ought to be, and moves toward enabling the discovery of identities in terms of the many different ways and meanings of “having sex”, which both creates the necessary tools for pleasurable first sex and safeguards sexual health.

Our findings are not new; there have been several attempts to address the missing discourse of pleasure in sex education (Fine, Citation1988), but this integration is not straightforward. Wood et al. (Citation2018) and Lamb (Citation2010) discussed how integrating pleasure into sex education can also inadvertently create a “pleasure imperative” and stress specific ideas about the meaning of good sex. Further, other uses of pleasure in sex education have framed it as “problematic” rather than something to be sought after; indeed, Lamb noted: “Pleasure is not typically discussed in a way that is meant to enhance self-knowledge … or [develop] sexual subjectivity. Instead, pleasure is presented as a problem in that it is an obstacle to restraint, abstinence, and health” (Lamb, Citation2010, p. 312). Because of this, the burden of discussing positive first sexual experiences may often fall to parents or friends, or entirely not be addressed (Santtila et al., Citation2009; Thompson, Citation1990).

As such, our findings indicate that when emphasizing pleasure within sex education, it is important to consistently return to the question of what sex “means” to each individual as a central orienting point of discussion. It is crucial to critically evaluate how to reconcile an individual’s understanding of what a pleasurable first sexual experience means for them with other elements of sex education, such as safe sexual practices. Our review also suggests that, in addition to addressing pleasure explicitly, it may be helpful to consider erotic skills building to provide individuals with the tools needed to have safe and pleasurable sexual debuts.

Nuanced Social Stratification

Few studies in this review focus on socio-economic factors, race, or broader marginalized communities in pleasurable first sexual experiences. Most of the included studies disaggregated their findings by gender or study only one sex at a time, but most did not have sufficient samples to examine characteristics such as race, class, or sexual identity or did not measure these characteristics at all. This is compounded by the fact that most of the samples for these studies have been drawn from white Global-North locales and universities or high schools, which inherently produces limitations to the generalizability of the findings to other racial groups. Studies that focus on these issues are often more interested in “at-risk” behaviors at sexual debut that can inform public health initiatives, which can be related to them being part of a more extensive study on HIV or STI prevention. Thompson’s (Citation1990) study is an exception here in that she strategically sampled across a wide variety of respondents; however, her analysis did not explicitly deal with race or class. The only included study in this review that actively tried to address ethnic and racial differences was the Higgins et al. (Citation2010) article; to our knowledge, there have not been any articles explicitly addressing income differences. The authors of most of the included studies have articulated that first sexual experiences are mediated by context, but they primarily focused on the context(s) of intoxication, peer pressure, receipt of sex education, and parental attitudes toward sex.

We must recognize that definitions of pleasurable first sexual experiences, the promotion of erotic education, and supporting sexual consent will happen within contexts of extreme social stratification. People with social advantages are more likely to have the “tools” (e.g., knowledge of safe sex practices and access to comprehensive sex education) to positively and pleasurably navigate their sexual debut. Several authors pointed to the importance of local contexts in sex education. Examples of this include differential access to sexual and reproductive information and health services for particular communities, and an emphasis on embedding local norms, such as gender scripts and marriage, within education programmes (Higgins et al., Citation2010; Marvan et al., Citation2018; Osorio et al., Citation2012).

Because of the unique contextual factors experienced by different communities, it is important to support efforts that respond to these specific needs. This often calls for more targeted interventions. While targeted approaches are beneficial, they are often framed as unsustainable and quickly fall through public health funding “gaps” and “prioritization.” In furthering this research, it is anticipated that programmes need to be adapted to populations’ specific needs.

Conclusion

In this review, we set out to document pleasure with first sexual experiences and its correlates, and we ended up engaging in a much more in-depth consideration of existing research on the complex and nuanced relationship between pleasure and sexual debut. We found that the existing literature offers some insight into pleasure in first sexual experiences but is limited by methodological, definitional, and binary-focused ideas about pleasure, sex, and sexuality. Future work should focus on elements of this review that show promise for increasing pleasure during first sexual experiences – better education around erotic skill building and consent, encouraging a strong sense of self and maturity, affective ties, and good communication with parents and partners. These aspects allowed participants in the studies we reviewed to reject heterosexist and misogynistic sexual norms and define their own, pleasurable, first sexual experience. This type of future research, alongside work that better defines pleasure and first sexual experiences as processes rather than as one-off events, can contribute to ensuring policies and programs that enable an environment where pleasure and sex co-reside.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (56.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the other members of the Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing (GAB), including Doortje Braeken, Vithika Yadav, Jian Chen, Lyubov Erofeeva, Faysal El Kak, Tlaleng Mofokeng, Anton Castellanos Usigli, Pauline Oosterhoff, James Tyrell and Caryn Gooi. The GAB was convened by the Reckitt Benckiser Group. The views expressed in the materials are those of the authors and not of RB.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial interests or benefits associated with the prepared research.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Additional information

Funding

References

- Averett, P., Moore, A., & Price, L. (2014). Virginity definitions and meaning among the LGBT community. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 26(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2014.924802

- Brandwatch Research Services. (2019, November). First timers. RB Internal Report.

- Caron, S. L., & Hinman, S. P. (2013). “I took his V-card”: An exploratory analysis of college students stories involving male virginity loss. Sexuality and Culture, 17(4), 525–539. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9158-x

- Carpenter, L. M. (2001). The ambiguity of “having sex”: The subjective experience of virginity loss in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 38(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490109552080

- Carpenter, L. M., & Garcia, L. (2007). Virginity lost: An intimate portrait of first sexual experiences. American Journal of Sociology, 113(1), 294–296.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2011. MMWR , 61(4). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6104.pdf

- Davidson, J. K., & Moore, N. B. (1994). Guilt and lack of orgasm during sexual intercourse: Myth versus reality among college women. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 20(3), 153–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1994.11074114

- Delgado-Infante, M. L., & Ofreneo, M. A. P. (2014). Maintaining a “good girl” position: Young Filipina women constructing sexual agency in first sex within Catholicism. Feminism and Psychology, 24(3), 390–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514530715

- Dixon-Mueller, R. (1993). The sexuality connection in reproductive health. Studies in Family Planning, 24(5), 269–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2939221

- Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.1.u0468k1v2n2n8242

- Ford, J. V., Corona Vargas, E., Finotelli, I., Fortenberry, J. D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Colemane, A. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587

- García-Moreno, C., Jansen, H., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Global Advisory Board. (2016). Working definition of sexual pleasure. Global Advisory Board for Sexual Health and Wellbeing. Convened by Reckitt Benckiser. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://www.gab-shw.org/our-work/working-definition-of-sexual-pleasure/

- Gruskin, S., Yadav, V., Castellanos-Usigli, A., Khizanishvili, G., & Kismödi, E. (2019). Sexual health, sexual rights and sexual pleasure: Meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 1593787. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787

- Hanbury, A., & Eastham, R. (2016). Keep calm and contracept! Addressing young women’s pleasure in sexual health and contraception consultations. Sex Education,16(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2015.1093925

- Hawes, Z. C., Wellings, K., & Stephenson, J. (2010). First heterosexual intercourse in the United Kingdom: A review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 47(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903509399

- Henderson, M., Wight, D., Raab, G., Abraham, C., Buston, K., Hart, G., & Scott, D. (2002). Heterosexual risk behaviour among young teenagers in Scotland. Journal of Adolescence, 25(5), 483–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2002.0493

- Higgins, J. (2018). The pleasure deficit. Perspect Sex Repro H, 50, 147–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12070

- Higgins, J. A., & Smith, N. (2016). The sexual acceptability of contraception: Defining a critical concept and reviewing the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 417–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1134425

- Higgins, J. A., Trussell, J., Moore, N. B., & Davidson, J. K. (2010). Virginity lost, satisfaction gained? Physiological and psychological sexual satisfaction at heterosexual debut. Journal of Sex Research, 47(4), 384–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224491003774792

- Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Sharpe, S., & Thomson, R. (2000). Deconstructing virginity—young people’s accounts of first sex. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 15(3), 221–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990050109827

- Ishii-Kuntz, M. (1990). Unconsummated homosexual inclinations—Evidence from a college sample. Sociology and Social Research, 74(4), 222–226.

- Katz, J., & Schneider, M. E. (2015). (Hetero)sexual compliance with unwanted casual sex: Associations with feelings about first sex and sexual self-perceptions. Sex Roles, 72(9–10), 451–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0467-z

- Kennedy, C. E., Yah, P. T., & Khosla, R. (in press). A systematic scoping review of informed consent in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters.

- Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews, 1(10). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

- Kleinplatz, P. J., Ménard, A. D., Paquet, M., Paradis, N., Campbell, M., Zuccarino, D., & Mehak, L. (2009). The components of optimal sexuality: A portrait of “great sex”. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 18, 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_4192

- Koepsel, E.R. (2016) The power in pleasure: Practical implementation of pleasure in sex education classrooms. American Journal of Sexuality Education,11(3), 205–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2016.1209451

- Lamb, S. (2010). Feminist ideals of healthy female adolescent sexuality: A critique. Sex Roles, 62(5), 294–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9698-1

- Malhotra, A., Amin, A., & Nanda, P. (2019). Catalyzing gender norm change for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: Investing in interventions for structural change. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), s13–s15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.013

- Marvan, M. L., Espinosa-Hernandez, G., & Orihuela-Cortes, F. (2018). Perceived consequences of first intercourse among Mexican adolescents and associated psycho-social variables. Sexuality and Culture, 22(4), 1490–1506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9539-x

- Nicholas, L., & Tredoux, C. (1996). Early, late and non-participants in sexual intercourse: A profile of black South African first-year university students. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 19(2), 111–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00114783

- Osorio, A., Lopez-del Burgo, C., Carlos, S., Ruiz-Canela, M., Delgado, M., & De Irala, J. (2012). First sexual intercourse and regret in three developing countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.012

- Palmer, M. J., Clarke, L., Ploubidis, G. B., Mercer, C. H., Gibson, L. J., Johnson, A. M., Copas, A. J., & Wellings, K. (2017). Is “sexual competence” at first heterosexual intercourse associated with subsequent sexual health status? Journal of Sex Research, 54(1), 91–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1134424

- Reissing, E. D., Andruff, H. L., & Wentland, J. J. (2012). Looking back: The experience of first sexual intercourse and current sexual adjustment in young heterosexual adults. Journal of Sex Research, 48(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.538951

- Rind, B. (2017). Reactions to first postpubertal female same-sex sexual experience in the Kinsey sample: A comparison of minors with peers, minors with adults, and adults with adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1517–1528. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0876-2

- Rind, B., & Welter, M. (2014). Enjoyment and emotionally negative reactions in minor-adult versus minor-peer and adult-adult first postpubescent coitus: A secondary analysis of the Kinsey data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(2), 285–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0186-x