ABSTRACT

Parents have a critical role to play in the sexual education of their children. We conducted a systematic review of studies assessing the experiences of parents regarding the role they play in the sexual education of their children. We included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies conducted among parents in Europe. We searched PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus, and screened 20,244 unique records. Forty-nine studies enrolling 18,083 unique parents met inclusion criteria. The studies show that parents have ideals regarding the sexual education of their children that center around the importance of trust, open conversations, and honesty. However, challenges and concerns, related to parents’ and children’s gender, children’s age, children’s specific situations, and limited parental knowledge and communication skills prevented them from living up to these ideals. Parents pointed to the role of other institutions as ways to support and strengthen parents’ contributions to the sexual development of their children. We conclude that parents may require guidance and support to identify what is appropriate sexual education for their children, based on age, gender, and other characteristics, how to provide appropriate sexual education, and to strengthen their sexual communication skills and knowledge of contemporary sexual health issues.

The process of raising children involves parents or carers promoting and supporting their children’s development, by transmitting their personal norms and values, and those of the society in which they are imbedded (Bornstein, Citation2012). Parents, including non-biological carers of children, also have a critical role to play in their children’s sexual development, in particular by providing guidance about sexual behaviors, relations, and desires that may affect sexual health outcomes (Lefkowitz & Stoppa, Citation2006; Shtarkshall et al., Citation2007). Sexual development is a multidimensional process encompassing biological, physical, mental, spiritual, social, ethical, religious, cultural, emotional, and behavioral aspects (Tamas et al., Citation2019).

Research has shown that sexual education by parents can have many positive effects on children’s sexual health (Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016; Widman et al., Citation2016). For instance, it was found to increase their children’s sexual knowledge and to promote their resilience to sexually transgressive experiences later in life (Franck et al., Citation2011). Sexual education by parents has also been shown to promote safer sex behaviors, including delayed sexual debut (DiIorio et al., Citation1999; Guilamo-Ramos et al., Citation2012; Lenciauskiene & Zaborskis, Citation2008; Martinez et al., Citation2010), increased contraception, and condom use (DiIorio et al., Citation2007; Widman et al., Citation2016), fewer sexual partners (Secor-Turner et al., Citation2011), and lower risk of sexually transmitted diseases (Coakley et al., Citation2017; Deptula et al., Citation2010; DiIorio et al., Citation2007).

However, despite their potentially critical role, contributing to the sexual education of children can be one of the more difficult tasks for parents (Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016), and parents are, hence, rarely children’s primary or even secondary source of sexual health information (Boyas et al., Citation2012; Epstein & Ward, Citation2008; Secor-Turner et al., Citation2011; Whitfield et al., Citation2013). The need to strengthen the role of parents in the sexual education of their children is highlighted in a recent review of sexual education in the WHO European Region, commissioned by the German Federal Center for Health Education and the International Planned Parenthood Federation European Network (Ketting & Ivanova, Citation2018). This review concluded that while parents are responsible for the sexual education of their children, especially in countries where sexual education programs are underdeveloped, “young people can hardly rely on their parents” (Ketting & Ivanova, Citation2018, p. 61), and instead receive unreliable or distorted information from peers and/or the internet.

Previous systematic reviews on the role of parents in the sexual education of their children have highlighted the positive impacts of sexual education by parents. However, these reviews were generally limited to research on the impact of adolescent-parent communication on reducing sexual risk behaviors and the prevention of adverse sexual health outcomes (e.g., Flores & Barroso, Citation2017). There is a dearth of attention in systematic reviews on research into the role of parents in the broader sexual education of their children, including important issues such as the positive aspects of sex and non-heterosexual identities. Research on parents’ role in sexual education during early childhood is also typically not addressed in systematic reviews (e.g., DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Guilamo-Ramos et al., Citation2012; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016). Furthermore, the experiences of parents with respect to the sexual education of their children are under-addressed, as systematic reviews tend to focus on the communication between parents and children and not on the experience of parents (e.g., Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016). Understanding the experiences of parents provides insights into their ideals, challenges and needs and can guide targeted support to strengthen their role in the sexual education of their children and improve their children’s outcomes. Moreover, systematic reviews on parents’ role in the sexual education of their children mostly include studies that were conducted in North America (e.g., Akers et al., Citation2011; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017) and the United Kingdom (e.g., Turnbull et al., Citation2008; Walker, Citation2004). The aim of this systematic review was to address these important knowledge gaps by synthesizing evidence from research into the experiences of European parents regarding the sexual education of their children. Our systematic review encompasses research into the experiences of parents with the sexual education of children of any age and with respect to any sexuality-related issue.

Method

Search Strategy

We searched electronic databases to identify peer-reviewed papers reporting empirical research into the experiences or needs of European parents regarding the sexual education of their children. Three electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus) were searched for articles published between 1 January 2010 and 16 January 2020. The literature search was designed to be inclusive of diverse adults involved in the parenting of children, including biological and non-biological parents, resident and nonresident parents, step- and adoptive parents, as well as legal guardians and other primary caregivers.

Comprehensive search strings were built that used Boolean operators to combine main terms and variations for parents (i.e., mother, father, guardian, caregiver), parenting (i.e. raising, rearing) sexuality (i.e., sex, puberty), and support needs (i.e., assistance, guidance) (see Supplementary material for the full search string). In addition to the database searches, reference lists of all included articles were searched to identify any papers not found through the electronic database search.

Inclusion Criteria

Papers were included if they were published in a peer-reviewed journal, written in English, included samples of European parents of children aged 0–18 years old, and reported findings from qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research into the experiences or needs of parents regarding their role in the sexual education of their children. We included studies of parents of any children in the identified age range, including parents raising children in specific situations (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, or other sexual orientation or gender identity (LGBTQ+) children, children with an intellectual or physical disability, children who were looked after by foster parents, and children who had experienced sexual abuse). Papers reporting studies of more diverse samples (e.g., including professionals, parents of young adults), were included if the experiences of parents of children aged 0–18 years could be separately identified and extracted.

Data Extraction

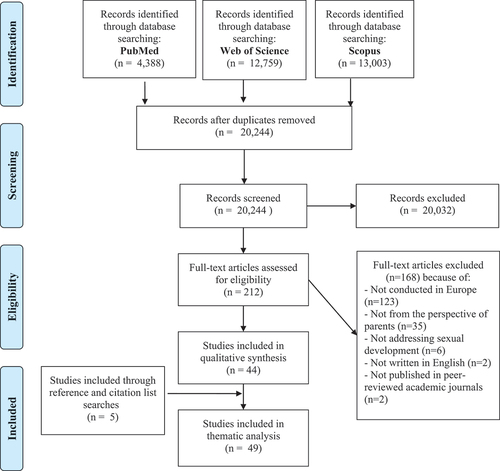

The literature search yielded 30,150 citations. After duplicates were excluded, the titles and abstracts of 20,244 citations were screened, with 214 papers identified for full-text assessment (). Two reviewers (MAJN and CDD) independently screened titles and abstracts of the first 1000 citations with discrepancies reconciled by a third independent reviewer (JDW). As agreement between the two reviewers was very high (99.5%), one reviewer (MAJN) assessed the titles and abstracts of the remaining citations, as well as the full texts. The other researchers (CDD and JDW) were consulted when any uncertainty arose regarding the eligibility of a paper. Forty-four eligible papers were identified, and through examination of their reference lists an additional five papers were found. In total, 49 eligible papers were included in the systematic review.

Key information from the included papers was extracted and tabulated by one investigator (MAJN). Characteristics extracted included country of research, research design, research method, recruitment strategy, sample size, characteristics of participants and their children, and main findings (see Supplementary material). Recorded characteristics of parents included their gender and relationship to their children (e.g., biological parent, stepparent, foster parent, grandparent). Recorded characteristics of the children of participating parents included their age and any specific characteristic (i.e., LGBTQ+ children, children with an intellectual or physical disability, children who were looked after, children who had experienced sexual abuse).

Data Analysis

Findings of included papers were analyzed through three stages of thematic synthesis: coding, developing descriptive themes and the generation of analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). One reviewer (MAJN) coded the results and developed descriptive themes. These were discussed among the research team and following discussions the analytical themes were distinguished to determine main themes and key messages.

Results

Overview of Included Papers

The 49 included papers reported on 41 unique studies. We included multiple papers from the same study as these reported findings based on different subsets of collected data. The papers reported studies conducted in 12 different European countries, with most studies conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 29; ). Most papers reported qualitative research (n = 29) with sample sizes of under 50 participants (n = 34). Across all studies, a total of 18,436 parents were sampled. Accounting for multiple papers reporting on the same study, the total sample consisted of 18,083 unique parents. Most sampled parents were biological mothers. Most papers reported studies with parents of children over the age of 12 (n = 33); few papers focused on studies of parents of children under the age of 12 (n = 13). Some papers reported on studies of parents of children in specific situations, notably LGBTQ+ children (n = 5), children with an intellectual disability (n = 7), children who were looked after (i.e., when parental responsibility is assumed by social services or shared between parents and social services; n = 1), children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (n = 1), and children who had experienced sexual abuse (n = 5).

Table 1. Characteristics of included papers reporting on parental experiences and needs regarding the sexual development and needs of their children (N = 49).

Across papers, seven analytical themes could be distinguished: (1) parents’ ideals regarding the sexual education of their children; (2) the realities parents experienced regarding the sexual education of their children; specific challenges and concerns regarding sexual education related to (3) the gender of parents and children, (4) children’s age, (5) children’s specific situations, and (6) parents’ communication skills; and (7) parents’ views of the role of organizations in the sexual education of their children.

Parents’ Ideals Regarding Their Children’s Sexual Education

Most studies noted that parents believed that the sexual education of their children is important, and found that parents thought they had a significant role to play in the sexual education of their children (Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Howard et al., Citation2016; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Several studies found that parents’ love of their children and their desire to help, protect, and support them guided ideals regarding their children’s sexual education (Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Cummins et al., Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2016; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Platero, Citation2014; Pryde & Jahoda, Citation2018). Parents were found to want to approach the sexual education of their children in a way that was better than the experiences they had with their own parents. Pertinent studies found that most parents indicated that sexuality was seldom discussed with them when they were young (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Stone et al., Citation2013; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011).

Parents were also found to aspire to a more contemporary relationship with their children, based on “trust, mutual disclosure and equality” (Hyde et al., Citation2010, p. 364). This included that parents wanted to be proactive and provide their children with the necessary sexual knowledge to protect them from ignorance (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2017; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, parents also were found to want their children to trust them and come to them when they experienced issues related to sexuality, so that they would be able support their children (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Several studies noted that parents believed that this was best realized in a culture of openness, where all aspects of sexuality were approached with an open mind (Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017).

Parents’ Experienced Realities of Their Children’s Sexual Education

Research has found that, despite parents’ good intentions, the realities regarding the sexual education of their children did not always align with their ideals. Rather than being proactive knowledge-providers, several studies found that parents tended to avoid discussing sexuality and took a more reactive stance, by only talking about sexual issues when their children initiated the conversation (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2016; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2012; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Also, only aspects of sexual knowledge that parents themselves deemed as crucial, such as the notion of “stranger danger” (Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017), were found to be proactively addressed.

Moreover, whilst parents were found to indicate that they would be willing to answer their children’s questions and support their children in their sexual development (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Hyde et al., Citation2010; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017), some studies found that parents indicated that their children generally did not come to them for support and advice on sexuality, and instead obtained information from other sources (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Other research found that when children under the age of 12 occasionally did approach their parents about issues related to sexuality (Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017), parents felt unprepared to respond and either deflected their children’s questions or answered with little forethought, leaving out important values or messages (Stone et al., Citation2017).

Additionally, parents were found to experience the desired honesty and culture of openness as challenging, as they felt compelled to adjust their children’s sexual education to gender norms, their children’s age and the perceived norms of society (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2016; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013, Citation2012; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Consequently, parents tended to leave out important aspects and details. At times, parents reported to even fabricate stories that they deemed more appropriate for their children. For instance, McGinn et al. (Citation2016, p. 586) described how parents created stories of babies being created with “special cuddles” and “being born out of bellybuttons or even ordered and picked up from shops.”

Sexual Education and Parents’ and Children’s Gender

While research found that all parents reported struggling to some extent to talk to their children about issues related to sexuality, men appeared to struggle more than women (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2018; Hyde et al., Citation2012; Kelleher et al., Citation2013; De Looze et al., Citation2015; Turnbull, Citation2012). Bennett et al. (Citation2018) found that fathers struggled with preexisting societal gender roles, whereby not men, but women are responsible for raising children at home, implying that women are also responsible for their children’s sexual education. When fathers were involved in sexual education, some studies found they typically spoke more to they sons than their daughters, as they could relate more to sons’ experiences than to those of their daughters (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2018; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). However, conversations between fathers and sons were described as brief and as lacking detail (Hyde et al., Citation2012). While in other studies some fathers indicated to be open about sexual education if their daughters approached them with questions (Bennett et al., Citation2018), most fathers avoided these conversations (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2018; Hyde et al., Citation2012). It was also found that as issues such as menstruation brought fathers extreme discomfort, the sexual education of their daughters was left to their mothers (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019). In contrast, one study from The Netherlands found that both fathers and mothers provided sexual education more to their daughters than their sons (De Looze et al., Citation2015).

Mothers, as the perceived principal sexual educators, were found to feel the need to speak about sexuality with their sons and daughters (Kelleher et al., Citation2013; Pownall et al., Citation2011; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). However, they reported that it was easier for them to discuss sexuality with their daughters (Pownall et al., Citation2011; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Their discussions with their daughters were noted to differ from fathers’ interactions with their sons, and were described to be more open and to include more details (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Pownall et al., Citation2011; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011).

Parents, irrespective of their own gender, were found to have different standards of sexual education for their daughters and sons. They were noted to believe that their daughters needed protection, as they were perceived to be in a vulnerable position, and could be sexually exploited, taken advantage of or have an unwanted pregnancy (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Howard et al., Citation2016; Hyde et al., Citation2012; Stone et al., Citation2013). Therefore, sex was found to be constructed as something dangerous and something girls should avoid until they are old enough (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Howard et al., Citation2016; Hyde et al., Citation2012; Stone et al., Citation2013). In contrast, parents generally were found to have few concerns about the sexuality of their sons and to accept their sons’ sexual exploration as something natural (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Hyde et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, some parents were found to be concerned that boys could be sexually corrupted by provocative girls or the media (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Hyde et al., Citation2012). Some studies reported that parents engaged their sons in conversations to encourage them to respect girls and practice safe sex (Hyde et al., Citation2012).

Children’s Age and Sexual Education

Children’s age was found to affect parents’ views on what should be included in their sexual education. Most parents were found to feel apprehensive of discussing sexuality with children under the age of 12, as they did not want to “destroy their [child’s] innocence and non-sexual state” (Bennett et al., Citation2017; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, p. 229, Citation2017). Sexual “innocence” was reportedly perceived as precious and fundamental of childhood, and exposing children to sexual knowledge would rob them of their childhood (Bennett et al., Citation2017; Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Therefore, parents wanted to gradually expose their children to information about sexuality, by introducing age-appropriate information.

However, research also found that parents indicated they had no clear way of determining what sexual education was age appropriate (Bennett et al., Citation2017; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). The majority of parents were found to base age appropriateness on their own judgment and the type of questions their children asked (Bennett et al., Citation2017; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011; Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). The uncertainty was found to place them in a vulnerable position, where they feared to be criticized of their judgment by society (Stone et al., Citation2013). Research found that they did not want to be viewed as a bad parent, who ruined their children’s innocence by introducing them to sexual education too early (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Howard et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013), nor did they want to seem irresponsible by leaving their children unaware of the sexual dangers of the real world (Stone et al., Citation2017).

Sexual Education of Children in Specific Situations

Research has found that it is more difficult for parents to provide sexual education to children who are in specific situations, because they identify as LGBTQ+ (cf. Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Cappellato & Mangarella, Citation2014; Gregor et al., Citation2015; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010; Platero, Citation2014), have an intellectual disability (Cummins et al., Citation2018; Dewinter et al., Citation2016; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; Pownall et al., Citation2012, Citation2011; Pryde & Jahoda, Citation2018; Tamas et al., Citation2019), are being looked after (Nixon et al., Citation2019), live with HIV (Gibbs et al., Citation2020), or have experienced sexual abuse (McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Powell & Cheshire, Citation2010; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012).

These children likely have different needs regarding their sexual development and sexual education, and issues to address differ from those of the majority of children and are likely to be socially stigmatized. For example, parents of LGBTQ+ children were reported to experience difficulties in supporting the sexual development of their children, including as a result if their struggles to accept their children’s sexual identity in conservative contexts, such as Italy (Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Cappellato & Mangarella, Citation2014; Gregor et al., Citation2015; Platero, Citation2014). Parents of children with an intellectual disability have described their fears of being judged by society, as providing sexual education to their children could be controversial, especially in more conservative societies such as Northern Ireland (Lafferty et al., Citation2012) and Serbia (Tamas et al., Citation2019). Additionally, parents of children with an intellectual disability reported finding it difficult to identify which sexual information would be appropriate for their children (Cummins et al., Citation2018; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; Pownall et al., Citation2012, Citation2011; Pryde & Jahoda, Citation2018).

Mothers raising children who were infected with HIV at birth were found to avoid discussing their children’s HIV status with them, as they did not want to upset their children, and also discouraged disclosure, as they wanted to protect their children from social and self-stigma (Gibbs et al., Citation2020). Social stigma was also reported to affect the parents of children who had been sexually abused. These parents in particular described the difficulty of discussing (suspicions of) sexual abuse with professional institutions and their own network, as they feared being judged as bad parents, who had been unable to prevent their children’s sexual abuse (McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012).

Parents’ Sexual Communication Skills

A main reported reason why parents did not provide sexual education to their children was their discomfort with the subject of sexuality. Due to the perceived social awkwardness of talking about sex, many studies found that parents reported feeling embarrassed when talking about sexuality with their children (Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Gregor et al., Citation2015; Howard et al., Citation2016; Kesterton & Coleman, Citation2010; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Nixon et al., Citation2019; Pop & Rusu, Citation2019; Pownall et al., Citation2012, Citation2011; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Pop and Rusu (Citation2019) found that embarrassment was greater among parents who were more anxious about communicating their own sexual issues with their romantic partners. Parents also described feeling particularly embarrassed when discussing private aspects of sexuality, such as masturbation, sexual pleasure, and condom usage (Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Pownall et al., Citation2012).

Relatedly, many studies found that parents reported that they lacked the skills or tact to discuss sexuality with their children (Bayley & Brown, Citation2015; Bennett & Harden, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Cummins et al., Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Gregor et al., Citation2015; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Newby et al., Citation2011; Nixon et al., Citation2019; Platero, Citation2014; Pop & Rusu, Citation2019; Pownall et al., Citation2012, Citation2011; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Parents of children under the age of 12 in particular reported avoiding discussing sexuality with their children, because they feared their children’s reaction and did not know how to respond to their children’s sexual curiosity (Howard et al., Citation2016; McGinn et al., Citation2016; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). This resulted in parents using an ad hoc communication style, with little consideration of important values or messages to convey (Stone et al., Citation2017). Parents of teenagers reported avoiding discussing sexuality with their children, because they feared their children’s negative reactions to the subject of sexuality, resulting in infrequent and incomplete communication (Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013).

Reflecting their own limited and fraught experiences with sexual education, parents were also noted to report a perceived lack of sexual knowledge education, which discouraged them to engage in sexuality conversations with their children (Bayley & Brown, Citation2015; Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Hyde et al., Citation2010; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010; Newby et al., Citation2011; Stone et al., Citation2013; Turnbull, Citation2012; Turnbull et al., Citation2013, Citation2011). This was especially noticeable for contemporary issues in sexual education of which parents had little personal knowledge, such as vaccination against human papillomavirus (Marek et al., Citation2011), and the prominence of sex in media (Bragg & Buckingham, Citation2013; Bragg et al., Citation2011). The reported lack of knowledge was greater among parents of children in specific situations, such as those with LGTBQ children (Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Cappellato & Mangarella, Citation2014; Gregor et al., Citation2015; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010; Platero, Citation2014; Sharek et al., Citation2019), children with an intellectual disability (Cummins et al., Citation2018; Dewinter et al., Citation2016; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; Pownall et al., Citation2012, Citation2011; Pryde & Jahoda, Citation2018; Tamas et al., Citation2019), looked after children (Nixon et al., Citation2019), children with HIV (Gibbs et al., Citation2020), or children who were sexually abused (McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012).

Roles of Other Organizations in Sexual Education

Several studies have found that parents looked to organizations on which they could depend to support their children’s sexual education (Alldred et al., Citation2016; Bennett et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Cummins et al., Citation2018; Czerwinski et al., Citation2018; Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Gregor et al., Citation2015; Hudson, Citation2018; Hyde et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; Newby & Mathieu-Chartier, Citation2018; Platero, Citation2014; Stone et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Parents were found to especially see an important role for schools in their children’s sexual education (Depauli & Plaute, Citation2018; Igor et al., Citation2015; Jankovic et al., Citation2013; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010; Turnbull et al., Citation2011). Various studies also found that it was important for parents to have a say in the sexual education schools provided to their children (Alldred et al., Citation2016; Depauli & Plaute, Citation2018; Igor et al., Citation2015; Jankovic et al., Citation2013; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010; Turnbull et al., Citation2011), and parents wanted sexual education to be provided by qualified, trained teachers (Depauli & Plaute, Citation2018; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010).

Some research assessed parents’ views on topics that should be included in school-based sexual education and when these topics should be introduced. Some parents were found to think that topics such as masturbation, pornography and sex work were unsuitable for their children and thought these could encourage inappropriate behavior (Jankovic et al., Citation2013; McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010). Importantly, some parents were found to not want schools to discuss certain topics, such as LGBTQ+-related issues, because they did not want schools to be “dictating what my moral view is or should be” (McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010, p. 393). There were also contradicting views of other parents, who wanted schools to engage with these more socially controversial topics, because they believed these needed to be addressed (McCormack & Gleeson, Citation2010).

In addition to schools, parents were also found to look to other organizations that may play a role in their children’s sexual education, such as parent organizations (Bertone & Franchi, Citation2014; Cappellato & Mangarella, Citation2014; Platero, Citation2014), social and health services (Gregor et al., Citation2015; Hill, Citation2012; Jessiman et al., Citation2017; Lafferty et al., Citation2012; McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Platero, Citation2014; Powell & Cheshire, Citation2010), or medical clinics (Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Platero, Citation2014). These organizations were typically identified by parents of children in specific situations, who likely required more support to address the sexual education needs of their children. These potentially supportive organizations were, however, not always easily accessible to parents. Parents of transgender children (Gregor et al., Citation2015; Platero, Citation2014), parents of children with an intellectual disability (Lafferty et al., Citation2012), and parents of children who experienced sexual abuse (Nixon et al., Citation2019; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012) reported difficulties in identifying the right organization(s) to provide support with the sexual education of their child. Once these services were located, parents were found to welcome their professional involvement (Gibbs et al., Citation2020; Gregor et al., Citation2015; McElvaney & Nixon, Citation2019; Søftestad & Toverud, Citation2012). For instance, Gibbs et al. (Citation2020) reported on parents’ positive experiences with clinicians and support groups for children with HIV. Still, research has also documented instances where parents were disappointed with the professional help offered. These included experiences of caretakers of looked after children who reported a lack of guidance on sexual education, which contributed to confusion and role ambiguity (Nixon et al., Citation2019). Platero (Citation2014) found that parents of transgender children in Spain struggled to receive necessary information, as they dealt with professionals who knew less than them about gender-nonconformity and transgender issues.

Discussion

In reviewing research on the experiences and needs of European parents regarding the sexual education of their children, this review observed that parents are found to have strong ideals regarding the sexual education of their children, which they want to reflect through open conversations, trust, and honesty. Research also showed that, despite good intentions, parents struggle to realize these ideals. They were found to experience difficulties in being open with their children about sexuality, and to adjust sexual education according to traditional gender-related expectations, their children’s age, and their children’s specific situations. In addition, the reviewed research showed that parents sometimes avoid conversations about sexual issues with their children when they felt uncomfortable to communicate about a specific topic, and felt that they lacked knowledge and skills. Parents were also noted to look at organizations, such as schools, parents’ organizations, social and health services or medical clinics, to take responsibility or provide them with support regarding the sexual education of their children.

These results are aligned with findings from previous reviews of research from other geographical locations, notably North America (e.g., Akers et al., Citation2011; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017), and the United Kingdom (e.g., Turnbull et al., Citation2008; Walker, Citation2004). Similar to these earlier reviews, we found that European parents, who tend to be considered progressive when it comes to sexual education, found the sexual education of their children important, but struggled to provide it (DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016; Turnbull et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, these earlier reviews also found that parents adjusted the content of sexual education according to the gender of both themselves and their children (DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016). As in our review, mothers were noted to take a more active role in the sexual education of their children than fathers, and sons were found to receive fewer and less detailed sexual health information and with a different message than daughters. Children’s age was also found to influence sexual education in previous reviews, which similarly reported that parents less likely to talk about sexuality-related issues with children under the age of 12 (DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016; Turnbull et al., Citation2008). In previous reviews, parents were also described to be apprehensive of sexual communication as they felt embarrassed or thought they lacked knowledge or skills, and looked at organizations involved in the education and care of their children to provide them with support regarding sexual education (DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016; Turnbull et al., Citation2008)

Despite the similarity of some of the main findings across our and earlier reviews, our review also provides contrasting and novel insights. Importantly, we conclude that research highlights that parents’ perspectives on sexual education differ significantly. Notably, our review of research in European countries showed that parents aspired to a relationship with their children in which sexual education was a continuous process that reflected open communication and trust. In contrast, previous reviews of research mostly conducted in the United States and United Kingdom concluded that parents had a more conservative stance regarding sexual education (Ashcraft & Murray, Citation2017; DiIorio et al., Citation2003; Flores & Barroso, Citation2017). Previous reviews specifically reported that some parents were concerned that sexual education could encourage children to engage in sexual activity, and that parents considered sexual education to be a one-off event whereby they would need to shock their children with the negative consequences of sex in the hope that they would remain abstinent. Whilst the research we reviewed showed that some European parents had more conservative views of sexual education than others, no research with European parents found that they promoted abstinence as a realistic sexual education objective.

One explanation for this important difference in findings between our and other reviews could be differences in the time during which the reviewed research was conducted. Our review only included research conducted since 2010, reflecting more contemporary views of European parents. However, the relatively recent reviews of Ashcraft and Murray (Citation2017), and Flores and Barroso (Citation2017) also highlighted the more conservative views of parents on sexual education. We propose that the predominance of research in previous reviews on the views on sexual education of parents in North America, notably the US, offers an alternative explanation for these disparate findings. More specifically, a comparison of diverse samples of parents in the US and the Netherlands suggested that the dominant culture regarding sexual education is more conservative in North America, while it is more progressive in Europe (Schalet, Citation2011).

Furthermore, previous reviews observed that the content of sexual education provided by parents was influenced by their ethnic identity and political beliefs (Malacane & Beckmeyer, Citation2016). In the reviewed research with European parents, ethnic identity and political beliefs were, however, not identified as factors that influenced their sexual education of their children. While ethnic identity and political beliefs may not play a (major) role in sexual education by European parents, we suggest that this difference in findings between our and previous reviews is more likely to reflect that few studies of European parents addressed ethnicity and none focused on political beliefs. Future research into the experiences and needs of European parents regarding sexual education may want to address this knowledge gap.

Our review highlights research findings regarding the experiences and needs with sexual education of parents of children in various specific situations, enabling the comparison of parents’ experiences and needs across a range of specific situations. To date, research on the experiences and needs of parents regarding the sexual education of children in specific situations is mostly synthesized in (broader) reviews of sexuality-related issues of children in specific situations, for example, on parents’ role in the (sexual) health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual children (Bouris et al., Citation2010), transgender parenting (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Citation2019), sexuality and decision-making regarding children with an intellectual disability (McGuire & Bayley, Citation2011), disclosure of child sexual abuse (Van Toledo & Seymour, Citation2013), and interventions for parents of children who disclosed sexual abuse (Van Toledo & Seymour, Citation2013). While some previous reviews documented experiences and needs of parents of LGBTQ+ children (Flores & Barroso, Citation2017; Turnbull et al., Citation2008), and of children who had experienced sexual abuse (Flores & Barroso, Citation2017), they did not address parents of children in other specific situations. Our review found that ideals regarding sexual education were largely similar between parents of children who did or did not experience specific situations. Nevertheless, specific situations made the realities of parents’ sexual education of these children more challenging, as more specific knowledge and skills were required and societal norms and values might be less clear about what is appropriate to discuss.

Earlier reviews generally did not address parents’ experiences with respect to discussing more contemporary sexuality-related issues with their children, such as the prominence of sex in the media, and HPV vaccination. Only the more recent reviews of Flores and Barroso (Citation2017) and Ashcraft and Murray (Citation2017) identified social media and HPV vaccination as an emergent issue for parents to address with their children. It should also be noted that whilst parents’ views of sexual education provided at school was addressed in other reviews (Turnbull et al., Citation2008; Walker, Citation2004), these described findings regarding parents’ preferred sexual education content and format in little detail. Our review especially highlighted parents’ disparate views of the role of school in the sexual education of their children.

Implications

This review shows that parents experience several barriers that may prevent them from realizing their ideals regarding the sexual education of their children. Based on the findings of our review, we suggest that parents will likely benefit from support to strengthen their skills and confidence to communicate about sexual issues with their children. The sexual communication self-efficacy of parents can be increased by guidance on how to successfully provide sexual education (Astle et al., Citation2021; Wight & Fullerton, Citation2013). This should include information, including on child sexual development, to assist parents in determining age-appropriate sexual education topics and communication strategies. Sexual education support for parents should also provide actionable examples of effective communication strategies (Wight & Fullerton, Citation2013), including of sexual communication with children under the age of 12 and on topics that parents experience as more challenging, notably sexual orientation and gender identity. Strengthening parents’ sexual communication self-efficacy ensures that they feel more prepared to initiate conversation and respond to children’s questions on sexual topics. Sexual education support is especially needed to enable fathers to contribute to the sexual education of their children (Guilamo-Ramos et al., Citation2012), in particular their daughters. Parents of children in specific situations are also in particular need of support, as they were found to experience a lack of support and uncertainty with respect to their role in the sexual education of their children.

Our review also highlights the importance of addressing social norms that may hinder parents from successfully contributing to their children’s sexual education. We found that parents’ involvement with the sexual education of their children reflected traditional gender roles. Mothers were more involved in the sexual education of their children than fathers, and, when involved, fathers were more likely to engage in communication about sexual topics with their sons than their daughters. We also found that parents were unsure about what is appropriate sexual education for children of different ages and genders, children in specific situations and with respect to more challenging topics, such as sexual orientation and gender identity. Support groups could provide a safe setting for parents to exchange experiences and contribute to supportive social norms (Astle et al., Citation2021; Wight & Fullerton, Citation2013). Also, views on what is appropriate sexual health education should be discussed between parents, teachers, and other school staff and leadership, as well as staff of other organizations that play a role in the sexual education of children. This provides parents with the information they may desire about the sexual education that schools provide (or not), enabling them to assess what further information they may want to provide to their children and align sexual education provided by professionals with their own ideals.

Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations need to be considered when appraising the conclusions of our review. Most parents who participated in the research included in this review were biological mothers, and the perspectives of fathers and other types of parents were underrepresented. It should also be noted that the majority of included studies were conducted in the United Kingdom or Ireland, and findings may not be representative for these and other parts of Europe. Also, most studies used convenience sampling to recruit parents and were based on small samples, possibly resulting in selection bias. Furthermore, most studies analyzed self-report data, which may be affected by memory bias and social desirability bias. Future research may want to prioritize focusing on the perspective of fathers, the experiences of parents outside the UK and Ireland, the perspectives of parents in blended families (e.g., divorced parents, single-parents and LGBTQ+ parents), and parents raising children in specific situations

Conclusion

This systematic review is one of the first to synthesize findings of research concerned with the experiences of parents regarding any aspect of the sexual education of their children. This allowed for the inclusion of research on a wide range of topics. We also included research with a variety of parents and other people providing care to children, allowing for the inclusion of a diverse group of parents in different situations. Lastly, whereas previous reviews predominantly included research with children as well as parents from North America and UK, this review specifically focused on research regarding the perspective of European parents only. The findings of our review suggest that European parents have ideals regarding the sexual education of their children that center around openness and trust, but experience challenges in living up to these ideals. Findings suggest that parents, in particular fathers, may require guidance and support to identify what is age-appropriate sexual education, how to provide appropriate sexual education to their sons as well as daughters, how to address the sexual education needs of children in specific situations, and to strengthen their sexual communication skills and knowledge of contemporary sexual health issues, such as HPV vaccination.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (160.5 KB)Acknowledgments

This study is part of a project funded by Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Seksualiteit under grant 19.006. The authors thank Kristin Jansen, Oka Storms, Hannan Nhass, Simon Timmerman, Nelleke Westerveld, Wilma Schakenraad and Shirin Eftekharijam from Movisie, the Dutch National Centre of Expertise of Social Issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akers, A. Y., Holland, C. L., & Bost, J. (2011). Interventions to improve parental communication about sex: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 127(3), 494–510. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2194

- Alldred, P., Fox, N., & Kulpa, R. (2016). Engaging parents with sex and relationship education: A UK primary school case study. Health Education Journal, 75(7), 855–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896916634114

- Ashcraft, A., & Murray, P. (2017). Talking to parents about adolescent sexuality. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 64(2), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.002

- Astle, S., Toews, M., Topham, G., & Vennum, A. (2021). To talk or not to talk: An analysis of parents’ intentions to talk with children about different sexual topics using the theory of planned behavior. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19, 705–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00587-6

- Bayley, J. E., & Brown, K. E. (2015). Translating group programmes into online formats: Establishing the acceptability of a parents’ sex and relationships communication serious game. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2545-0

- Bennett, C., & Harden, J. (2019). Sexuality as taboo: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis and a Foucauldian lens to explore fathers’ practices in talking to their children about puberty, relationships and reproduction. Journal of Research in Nursing, 24(1–2), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987118818863

- Bennett, C., Harden, J., & Anstey, S. (2017). The silencing effects of the childhood innocence ideal: The perceptions and practices of fathers in educating their children about sexuality. Sociology of Health & Illness, 39(8), 1365–1380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12591

- Bennett, C., Harden, J., & Anstey, S. (2018). Fathers as sexuality educators: Aspirations and realities. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Sex Education, 18(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2017.1390449

- Bertone, C., & Franchi, M. (2014). Suffering as the path to acceptance: Parents of gay and lesbian young people negotiating Catholicism in Italy. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(1–2), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.857496

- Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting, 12(2–3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., Gloppen, K., & Waldmiller, J. M. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5), 273–309. doi:10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1

- Boyas, J., Stauss, K., & Murphy-Erby, Y. (2012). Predictors of frequency of sexual health communication: Perceptions from early adolescent youth in rural Arkansas. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29(4), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0264-2

- Bragg, S., & Buckingham, D. (2013). Global concerns, local negotiations and moral selves: Contemporary parenting and the “sexualisation of childhood” debate. Feminist Media Studies, 13(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.700523

- Bragg, S., Buckingham, D., Russell, R., & Willett, R. (2011). Too much, too soon? Children, ‘sexualization’ and consumer culture. Sex Education, 11(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2011.590085

- Cappellato, V., & Mangarella, T. (2014). Sexual citizenship in private and public space: Parents of gay men and lesbians discuss their experiences of Pride parades. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(1–2), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.857233

- Coakley, T. M., Randolph, S., Shears, J., Beamon, E. R., Collins, P., & Sides, T. (2017). Parent-youth communication to reduce at-risk sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(6), 609–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2017.1313149

- Cummins, C., Pellicano, E., & Crane, L. (2018). Supporting minimally verbal autistic girls with intellectual disabilities through puberty: Perspectives of parents and educators. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(7), 2439–2448. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3782-8

- Czerwinski, F., Finne, E., Alfes, J., & Kolip, P. (2018). Effectiveness of a school-based intervention to prevent child sexual abuse-Evaluation of the German IGEL program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.023

- de Looze, M., Constantine, N. A., Jerman, P., Vermeulen-Smit, E., & ter Bogt, T. (2015). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and its association with adolescent sexual behaviors: A nationally representative analysis in the Netherlands. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.858307

- Depauli, C., & Plaute, W. (2018). Parents’ and teachers’ attitudes, objections and expectations towards sexuality education in primary schools in Austria. Sex Education, 18(5), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1433650

- Deptula, D. P., Henry, D. B., & Schoeny, M. E. (2010). How can parents make a difference? Longitudinal associations with adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(6), 731–739. doi:10.1037/a0021760

- Dewinter, J., Vermeiren, R. R. J. M., Vanwesenbeeck, I., & Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2016). Parental awareness of sexual experience in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 713–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2622–3

- DiIorio, C., Kelley, M., & Hockenberry-Eaton, M. (1999). Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24(3), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00115-3

- DiIorio, C., McCarty, F., Resnicow, K., Lehr, S., & Denzmore, P. (2007). REAL men: A group-randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for adolescent boys. American Journal of Public Health, 97(6), 1084–1089. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.073411

- DiIorio, C., Pluhar, E., & Belcher, L. (2003). Parent-child communication about sexuality: A review of the literature from 1980-2002. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children, 5(3–4), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J129v05n03_02

- Epstein, M., & Ward, L. M. (2008). “Always use protection”: Communication boys receive about sex from parents, peers, and the media. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9187-1

- Flores, D., & Barroso, J. (2017). 21st century parent-child sex communication in the United States: A process review. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 532–548. doi:10.1080/00224499.2016.1267693

- Franck, T., Frans, E., & Van Decraen, E. (2011). Over de Grens? Seksueel opvoeden met het Vlaggensysteem. Movisie. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.movisie.nl/sites/movisie.nl/files/publication-attachment/Over%20de%20grens%20%5BMOV-177637-0.3%5D.pdf

- Gibbs, C., Melvin, D., Foster, C., & Evangeli, M. (2020). “I don’t even know how to start that kind of conversation”: HIV communication between mothers and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(10–11), 1341–1354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318755544

- Gregor, C., Hingley-Jones, H., & Davidson, S. (2015). Understanding the experience of parents of pre-pubescent children with gender identity issues. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0359-z

- Guilamo-Ramos, V., Bouris, A., Lee, J., McCarthy, K., Michael, S. L., Pitt-Barnes, S., & Dittus, P. (2012). Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1313–e1325. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011–2066

- Hafford-Letchfield, T., Cocker, C., Rutter, D., Tinarwo, M., McCormack, K., & Manning, R. (2019). What do we know about transgender parenting?: Findings from a systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1111–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12759

- Hill, A. (2012). Help for children after child sexual abuse: Using a qualitative approach to design and test therapeutic interventions that may include non-offending parents. Qualitative Social Work, 11(4), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325012438078

- Howard, C., Hallam, J., & Brady, K. (2016). Governing the souls of young women: Exploring the perspectives of mothers on parenting in the age of sexualisation. Journal of Gender Studies, 25(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2014.952714

- Hudson, K. (2018). Preventing child sexual abuse through education: The work of Stop it Now! Wales. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 24(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2017.1383088

- Hyde, A., Carney, M., Drennan, J., Butler, M., Lohan, M., & Howlett, E. (2010). The silent treatment: Parents’ narratives of sexuality education with young people. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(4), 359–371. doi:10.1080/13691050903514455

- Hyde, A., Drennan, J., Butler, M., Howlett, E., Carney, M., & Lohan, M. (2013). Parents’ constructions of communication with their children about safer sex. Journal of Cinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3438–3446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12367

- Hyde, A., Drennan, J., Howlett, E., Carney, M., Butler, M., & Lohan, M. (2012). Parents’ constructions of the sexual self-presentation and sexual conduct of adolescents: Discourses of gendering and protecting. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(8), 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.708944

- Igor, K., Ines, E., & Aleksandar, Š. (2015). Parents’ attitudes about school-based sex education in Croatia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0203-z

- Jankovic, S., Malatestinic, G., & Striehl, H. B. (2013). Parents’ attitudes on sexual education–what and when? Collegium Antropologicum, 37(1), 17–22. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/146503

- Jessiman, P., Hackett, S., & Carpenter, J. (2017). Children’s and carers’ perspectives of a therapeutic intervention for children affected by sexual abuse. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12322

- Kelleher, C., Boduszek, D., Bourke, A., McBride, O., & Morgan, K. (2013). Parental involvement in sexuality education: Advancing understanding through an analysis of findings from the 2010 Irish Contraception and Crisis Pregnancy Study. Sex Education, 13(4), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2012.760448

- Kesterton, D., & Coleman, L. (2010). Speakeasy: A UK-wide initiative raising parents’ confidence and ability to talk about sex and relationships with their children. Sex Education, 10(4), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2010.515100

- Ketting, E., & Ivanova, O. (2018). Sexuality education in Europe and Central Asia: State of the art and recent developments (an overview of 25 countries). Federal Centre for Health Education, BZgA. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/379054/BZgA_IPPFEN_ComprehensiveStudyReport_Online.pdf

- Lafferty, A., McConkey, R., & Simpson, A. (2012). Reducing the barriers to relationships and sexuality education for persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629512438034

- Lefkowitz, E. S., & Stoppa, T. M. (2006). Positive sexual communication and socialization in the parent-adolescent context. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2006(112), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.161

- Lenciauskiene, I., & Zaborskis, A. (2008). The effects of family structure, parent-child relationship and parental monitoring on early sexual behaviour among adolescents in nine European countries. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36(6), 607–618. doi:10.1177/1403494807088460

- Malacane, M., & Beckmeyer, J. J. (2016). A review of parent-based barriers to parent–adolescent communication about sex and sexuality: Implications for sex and family educators. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2016.1146187

- Marek, E., Dergez, T., Bozsa, S., Gocze, K., Rebek-Nagy, G., Kricskovics, A., Kiss, I., Ember, I., & Gocze, P. (2011). Incomplete knowledge - unclarified roles in sex education: Results of a national survey about human papillomavirus infections. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20(6), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01258.x

- Martinez, G., Abma, J., & Copen, C. (2010). Educating teenagers about sex in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. Number 44. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530162.pdf

- McCormack, O., & Gleeson, J. (2010). Attitudes of parents of young men towards the inclusion of sexual orientation and homophobia on the Irish post-primary curriculum. Gender and Education, 22(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250903474608

- McElvaney, R., & Nixon, E. (2019). Parents’ experiences of their child’s disclosure of child sexual abuse. Family Process, 59(4), 1773–1788. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12507

- McGinn, L., Stone, N., Ingham, R., & Bengry-Howell, A. (2016). Parental interpretations of “childhood innocence”: Implications for early sexuality education. Health Education, 116(6), 580–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-10-2015-0029

- McGuire, B. E., & Bayley, A. A. (2011). Relationships, sexuality and decision-making capacity in people with an intellectual disability. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(5), 398–402. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328349bbcb

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & The Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Newby, K., Bayley, J., & Wallace, L. M. (2011). “What should we tell the children about relationships and sex?”: Development of a program for parents using intervention mapping. Health Promotion Practice, 12(2), 209–228. doi:10.1177/1524839909341028

- Newby, K. V., & Mathieu-Chartier, S. (2018). Spring fever: Process evaluation of a sex and relationships education programme for primary school pupils. Sex Education, 18(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2017.1392297

- Nixon, C., Elliott, L., & Henderson, M. (2019). Providing sex and relationships education for looked-after children: A qualitative exploration of how personal and institutional factors promote or limit the experience of role ambiguity, conflict and overload among caregivers. BMJ Open, 9(4), e025075. t. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025075

- Platero, R. L. (2014). The influence of psychiatric and legal discourses on parents of gender-nonconforming children and trans youths in Spain. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(1–2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.857232

- Pop, M. V., & Rusu, A. S. (2019). Couple relationship and parent-child relationship quality: Factors relevant to parent-child communication on sexuality in Romania. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(3), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030386

- Powell, L., & Cheshire, A. (2010). A preliminary evaluation of a massage program for children who have been sexually abused and their nonabusing mothers. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538711003627256

- Pownall, J. D., Jahoda, A., & Hastings, R. P. (2012). Sexuality and sex education of adolescents with intellectual disability: Mothers’ attitudes, experiences, and support needs. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.2.140

- Pownall, J. D., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R., & Kerr, L. (2011). Sexual understanding and development of young people with intellectual disabilities: Mothers’ perspectives of within-family context. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116(3), 205–219. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-116.3.205

- Pryde, R., & Jahoda, A. (2018). A qualitative study of mothers’ experiences of supporting the sexual development of their sons with autism and an accompanying intellectual disability. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 64(3), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2018.1446704

- Schalet, A. T. (2011). Not under my roof. University of Chicago Press.

- Secor-Turner, M., Sieving, R. E., Eisenberg, M. E., & Skay, C. (2011). Associations between sexually experienced adolescents’ sources of information about sex and sexual risk outcomes. Sex Education, 11(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2011.601137

- Sharek, D., McCann, E., & Huntley-Moore, S. (2019). A mixed-methods evaluation of a gender affirmative education program for families of trans young People. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 18(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1614504

- Shtarkshall, R. A., Santelli, J. S., & Hirsch, J. S. (2007). Sex education and sexual socialization: Roles for educators and parents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(2), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1363/3911607

- Søftestad, S., & Toverud, R. (2012). Parenting conditions in the midst of suspicion of child sexual abuse (CSA). Child and Family Social Work, 17(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00774.x

- Stone, N., Ingham, R., & Gibbins, K. (2013). `Where do babies come from?’ Barriers to early sexuality communication between parents and young children. Sex Education, 13(2), 228–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2012.737776

- Stone, N., Ingham, R., McGinn, L., & Bengry-Howell, A. (2017). Talking relationships, babies and bodies with young children: The experiences of parents in England. Sex Education, 17(5), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2017.1332988

- Tamas, D., Jovanovic, N. B., Rajic, M., Ignjatovic, V. B., & Prkosovacki, B. P. (2019). Professionals, parents and the general public: Attitudes towards the sexuality of persons with intellectual disability. Sexuality and Disability, 37(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-09555-2

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45), 1471–2288. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Turnbull, T. (2012). Communicating about sexual matters within the family: Facilitators and barriers. Education and Health, 30(2), 40–47. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://sheu.org.uk/sheux/EH/eh302tt.pdf

- Turnbull, T., Van Schaik, P., & Van Wersch, A. (2013). Exploring the role of computers in sex and relationship education within British families. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(4), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.1507

- Turnbull, T., Van Wersch, P., & Schaik, P. (2008). A review of parental involvement in sex education: The role for effective communication in British families. Health Education Journal, 67(3), 182–195. doi:10.1177/0017896908094636

- Turnbull, T., van Wersch, A., & van Schaik, P. (2011). Parents as educators of sex and relationship education: The role for effective communication in British families. Health Education Journal, 70(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896911398817

- van Toledo, A., & Seymour, F. (2013). Interventions for caregivers of children who disclose sexual abuse: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.006

- Walker, J. (2004). Parents and sex education—looking beyond ‘the birds and the bees.’ Sex Education, 4(3), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/1468181042000243330

- Whitfield, C., Jomeen, J., Hayter, M., & Gardiner, E. (2013). Sexual health information seeking: A survey of adolescent practices. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3259–3269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12192

- Widman, L., Choukas-Bradley, S., Noar, S. M., Nesi, J., & Garrett, K. (2016). Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731

- Wight, D., & Fullerton, D. (2013). A review of interventions with parents to promote the sexual health of their children. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(1), 4–27. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.014