?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Sex differences in short-term mating behaviors are well-documented in human sexuality research. Existing studies usually explain sex differences in sexual behaviors through differences in mating preferences, which is theoretically problematic. Using an agent-based model, we investigated the circumstances under which males’ and females’ differential preferences for short-term mating would result in sex differences in short-term mating behaviors. The model showed that when all individuals in a closed heterosexual population were considered, males and females had the same average number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates even when males had stronger preferences for short-term mating. Males (vs. females) had a higher average number of both experiences and mates when analyses were limited to only heterosexual males and females who successfully participated in the mating pool (i.e., those with a non-zero number of short-term mating experiences). Moreover, when males (vs. females) had stronger preferences for short-term mating, gay males had a higher average number of experiences and mates compared to both lesbian females and heterosexual males. These results suggest that even when sex differences in mating preferences exist, the sex differences in short-term mating behaviors only occur among particular populations, or when males’ preferences for short-term mating are not constrained by those of females. Suggestions for future research in human mating psychology and behaviors were provided.

Introduction

Sex differences in sexual behaviors, especially short-term mating behaviors, are well-documented in human sexuality research. For example, research has found that heterosexual males, as compared to heterosexual females, report having a higher average number of past short-term sexual partners (Oliver & Hyde, Citation1993; Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010; Rissel et al., Citation2014), and engage in both short-term mating and extramarital sex more often (Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010). These sex differences have also been observed between gay males and lesbian females and among transgender individuals. Gay males have been found to engage in short-term mating particularly often compared to lesbian females and even to heterosexual males (Bailey et al., Citation1994; Bryant & Demian, Citation1994; Peplau et al., Citation1997, Citation2004). A recent study has also found that male-born individuals scored higher than female-born individuals on all dimensions of sociosexuality, including sexual behaviors, regardless of their gender identities (de Menezes Gomes et al., Citation2020).

In the existing literature, sex differences in actual sexual behaviors are usually explained through the differences in attitudes toward or preferences for short-term mating. For example, many assume that behavioral differences are a direct expression of the psychological ones (e.g., Schmitt et al., Citation2001). Intuitive as this line of reasoning is, there are good reasons to doubt its soundness, especially in the case of heterosexual individuals. This is because any heterosexual sexual encounter involves both a male and a female (the frequency of encounters involving more than two persons is negligible, e.g., Herbenick et al., Citation2017). A new short-term mating experience for a male is, therefore, also a new experience for a female. Likewise, when a male has a new short-term mate, so does his partner. As a result, the psychological differences in short-term mating preferences may not result in behavioral ones in the heterosexual case (Archer, Citation2019).

The present study aimed to address two theoretical issues that have been underexamined in the literature: a) the causal relation between sex differences in mating preferences and those in mating behaviors, and b) the existence of a shared explanation for sex differences in mating behaviors among heterosexual individuals, on the one hand, and those among gay males and lesbian females, on the other. As a starting point, we took sex differences in mating preferences as conceptualized by the sexual strategies theory (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993;, Citation2019), which has been repeatedly supported by empirical investigations (e.g., Schmitt, Citation2003; Walter et al., Citation2020). Using an agent-based model, we investigated whether males' and females’ differential preferences for short-term mating would result in sex differences in short-term mating behaviors, and if so, then under what conditions they would result in differences in the number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates.

Sex Differences in Short-term Mating Preferences

Sex differences in mating preferences have been studied in the light of sexual strategies theory (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993, Citation2019). It posits that since the minimum obligatory investment that males must devote to their offspring (contribution of sperm through one sexual act) is lower than that of females (gestation, labor, and lactation), males tend to be relatively more interested in short-term mating compared to females, that is, in mating behaviors of short duration without commitment (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993). This is because the number of offspring females can produce is limited and cannot be increased by mating with a large number of males, whereas the reverse is the case for males. As a result, males are predicted to not only have a greater interest in short-term mating, but also desire a larger number of short-term mates in a given period and be less selective with respect to accepting a potential mate (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993).

The hypotheses derived from sexual strategies theory have received extensive support in empirical studies. For example, males have reported to be currently seeking short-term mates to a larger extent than females (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993; Schmitt, Citation2003; Schmitt et al., Citation2001), and a larger proportion of males were in any way seeking short-term mates (vs. not seeking; Schmitt, Citation2003). Similar results have been found among both U.S. college students (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993; Schmitt et al., Citation2001) as well as in ten world regions in a cross-cultural study (Schmitt, Citation2003). Similarly, males across the world have also been reported to desire more short-term sexual partners compared to females over different future time periods (e.g., a month, a year; Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993; McBurney et al., Citation2005; Schmitt, Citation2003). The sex differences have been found regardless of whether they were estimated using mean (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993; Schmitt, Citation2003; Schmitt et al., Citation2001), median (Schmitt, Citation2003; Schmitt et al., Citation2001), or percentage (Schmitt, Citation2003) statistics.

As for mating standards, males are less selective in accepting someone as a potential short-term mate. For example, studies using U.S. college samples have found that males’ acceptable minimum percentile ranks of the desirability of a potential short-term sexual partner were lower than those accepted by females, in terms of both the overall desirability and the desirability of individual traits (e.g., social status, attractiveness; Kenrick et al., Citation1990; Regan, Citation1998). Another study also found that when presented with identical descriptions of potential mates, males on average rated them as more desirable than females did (Wiederman & Dubois, Citation1998).

Some evidence shows that sex differences in mating preferences also exist between gay males and lesbian females, suggesting that these differences are based on individuals’ sex rather than their sexual orientation. A survey study using a community sample from the U.S. found that gay males were more interested in short-term mating than lesbian females were, and that this difference was comparable to that existing among heterosexual individuals (Bailey et al., Citation1994). An additional indirect piece of evidence on differential standards for short-term mates comes from a recent study finding that significantly more gay males than lesbian females reported to have accepted a casual sexual offer from a same-sex person (Matsick et al., Citation2021). Past studies suggest that the sex difference in the acceptance rate of casual sexual offers may originate from males' and females’ differential standards for short-term mates (Conley et al., Citation2011; Hald & Høgh-Olesen, Citation2010). Thus, as a postulation, gay males may also have lower standards than lesbian females for short-term mates.

Constraints on Males’ Preferences for Short-term Mating

Since evolutionary theories predict that males have a greater interest in short-term mating than females regardless of sexual orientation, this interest can lead to different behavioral consequences among males depending on whether they are heterosexual (partners being females) or gay males (partners being males). Among heterosexual individuals, sex in most cases involves one male and one female, meaning that males’ relatively high interest in short-term mating can be constrained by females’ preference for long-term relationships (Archer, Citation2019; Symons, Citation1979). This is because males’ short-term mating preferences – with the exception of sexual violence – can only translate into behaviors when there are females willing to have sex with them. When a new short-term mating encounter occurs, both males’ and females’ total number of short-term mating experiences and the number of short-term mates increase by one. Therefore, theoretically speaking, the total number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates must be equal between heterosexual males and females at the population level. In a closed population with equal sex ratio, it follows that the average number of experiences and mates should also be equal between males and females. Following this line of reasoning, we would expect to observe no sex difference in short-term mating behaviors among heterosexual individuals even when there were sex differences in mating preferences.

However, it is important to note that although heterosexual males’ total number of short-term mating would be equal to that of females, this does not necessarily mean that the total number of males and females who have ever had short-term mating must be equal. Empirical studies have found that the proportion of individuals who are sexually inexperienced is slightly higher among males than females in most age groups above 18 years old (Ghaznavi et al., Citation2019; Haydon et al., Citation2014). Therefore, as a postulation, there may be a smaller proportion of males (vs. the proportion of females) who participate in the mating pool and contribute to the total number of short-term mating. For example, suppose that there is a population of 20 individuals with an equal sex ratio. Heterosexual short-term mating have happened n times in this population, but only 3 males and 8 females have had any short-term mating experiences. Since the total number of short-term mating behaviors is the same between males and females, we would expect that in a population of individuals who participate in the mating pool, the average numbers of short-term mating experiences and mates are higher among males than females (e.g., in the aforementioned example, the average number of short-term experiences is for males and

for females who are in the mating pool).

As a comparison, in the cases of gay males and lesbian females, males’ preferences are not constrained by those of females’, but only by those of other males, who, arguably, have a similar strong interest in short-term mating (Archer, Citation2019). This would allow for a more direct behavioral expression of males’ mating preferences. The notion that gay males have less restricted preferences is borne out in the proportion of individuals who have engaged in extradyadic sex (Peplau et al., Citation2004). A study showed that the proportions of heterosexual males and females who had engaged in extradyadic sex were 26% and 21%, respectively, while the numbers among gay males and lesbian females were 82% and 28%, respectively (Peplau et al., Citation2004). This might be because when gay males had the intention to engage in extradyadic sex, their male partners were more likely to agree due to an equally strong interest in short-term mating as compared to heterosexual males’ or lesbian females’ female partners. Therefore, we would expect to observe sex differences in short-term mating behaviors between gay males and lesbian females. Moreover, we would also expect to find that gay males would engage in more short-term mating behaviors compared to heterosexual males since their mating preferences are not constrained by females.

A Simple Model of Short-term Mating Behaviors

By using a spatial agent-based model, the present study investigated whether males' and females’ differential preferences for short-term mating would result in sex differences in short-term mating behaviors, and if they did, under what circumstances. Preferences for short-term mating were operationally defined as the likelihood of engaging in short-term mating upon encountering a mate and the standards for short-term mates (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993). Short-term mating behaviors were operationally defined as the number of short-term mating experiences and the number of past short-term mates (Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010).

We also modeled forming long-term relationships as a background process. A pair of individuals had a possibility to commit to a long-term relationship upon meeting each other. This process was modeled at a behavioral level and the psychological processes behind it were ignored, although we recognized that sex differences may also exist in long-term mating strategy (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993;, Citation2019).

We modeled these processes among both heterosexual individuals and gay males and lesbian females to examine whether constraints set by the opposite sex’s preferences would affect short-term mating behaviors. Individuals’ sexual orientation was conceptualized as categorical in terms of behaviors only in our model. Heterosexual males had short-term mating or formed a long-term relationship only with females, while gay males only with other males, and mutatis mutandis for females.

We formulated the following hypotheses: assuming sex differences in preferences for short-term mating, 1) there would be no sex differences in short-term mating behaviors between heterosexual males and females when considering the full population, 2) a smaller proportion of heterosexual males (vs. heterosexual females) would have ever engaged in short-term mating, 3) in a population of heterosexual individuals who had any short-term mating, males would have a higher average number of short-term mating behaviors than females, 4) gay males would engage in more short-term mating behaviors compared to lesbian females, and 5) compared to heterosexual males.

Method

Model Design

We developed an agent-based model to represent a simplified environment where males and females can move around, search for mates, and form long-term and/or short-term relationships. Space and time were modeled as discrete variables. Space was represented as discrete locations on a two-dimensional 33*33 lattice. Agents’ movement in the space was not meant to simulate physical movement but a state of encountering potential mates. Staying at one location represented being committed to a long-term relationship.

The model measured two outcomes: (1) the number of short-term mating experiences of males and females; (2) the number of short-term mates of males and females. Additionally, we also measured the number of males and females in the mating pool (i.e., those with a non-zero number of short-term mating experiences). The average numbers of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates were calculated by taking the average among the whole population of males and females (Nmale = Nfemale = 150) and among those who had ever engaged in any short-term mating. See the Supplemental Materials for the overview, design concepts, and details (ODD) protocol of the model, which includes detailed scheduling and parameterization. The model can be downloaded from the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/4kf26/. The model was programmed in Netlogo 6.2.1 (Wilensky, Citation1999).

Experiment Design

Using the agent-based model, the present study conducted two 2 (sex difference vs. no difference in the interest in short-term mating likelihood) x 2 (sex difference vs. no difference in mating standards) experiments. Experiment 1 was run among heterosexual agents who only engaged in short-term or long-term relationships with agents of the opposite sex. Experiment 2 was run among gay males and lesbian females who only engaged in short-term or long-term relationships with agents of the same sex.

The interest in short-term mating was modeled as an agent’s likelihood of deciding to have short-term mating at each time step. The standards for short-term mates were modeled as the minimum desirability of a potential mate with whom an agent was willing to have sex. The values of the two parameters were set based on empirical findings in human mating psychology. When there was a sex difference in short-term mating likelihood, males had a 40% likelihood of deciding to engage in short-term mating, while females had a likelihood of 25% (Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993; Schmitt, Citation2003; Schmitt et al., Citation2001). When there was no sex difference in short-term mating likelihood, both females and males had a likelihood of 25%. When there was a sex difference in mating standards, males had a mating standard of 3 (the highest possible value = 10), while females had a standard of 5 (Kenrick et al., Citation1990; Regan, Citation1998), that is, they would not mate with a person with a lower mate value. When there was no sex difference in mating standards, both males and females had a standard of 5.

Procedure

Initial Setup of the Model

In total, 150 females and 150 males were created on the lattice at random locations. All agents were initialized with (1) a three-unit maximum distance by which agents can move away from their birthplace (movement range); (2) a 10% likelihood of two agents forming a long-term relationship upon meeting (To the best of our knowledge, there are no available empirical statistics for the probability of this event. We ran sensitivity analyses on different values of this parameter to check the robustness of our results. See Section C of the supplemental materials.); (3) single status and no long-term partner; (4) a mate value, sampled from a Gaussian distribution (M = 5.0, SD = 1.5); (5) no short-term mate or short-term mating history.

The likelihood of engaging in short-term mating and the standard for short-term mates were initialized to the values as discussed previously. Whether males and females had the same initial values depended on the experimental condition.

Procedures for Heterosexual Agents

At each time step, agents first checked whether they were in a long-term relationship. If they were in a long-term relationship, they did not move. If they were not in a long-term relationship, they set their heading randomly (if they were within the movement range from the birthplace) or faced the birthplace (if they were out of the movement range from the birthplace) and moved by a random distance. The random distance was less than half of the movement range. Then, the agents decided on whether to engage in short-term mating using the predetermined likelihood (either 25% or 40%).

Females checked to see if any males were at the same location. If there were, they randomly chose one of them as a potential short-term mate. If both males and females met each other’s mating standards and both of them decided to engage in short-term mating, they had sex. This would result in increasing both parties’ number of short-term mating experiences by one. They also recorded each other on their respective lists of past short-term mates if they were not on the lists yet.

Then, females randomly selected one male at the same location as their potential long-term partner. There was a 10% of chance that a pair of individuals would form a long-term relationship. After forming a long-term relationship, both males and females changed to coupled status and registered each other as their long-term partner.

Procedures for Gay Male and Lesbian Female Agents

At each time step, males and females moved and decided on short-term mating as the agents did in the heterosexual case. Half of the agents (75 males and 75 females) were also given an initiator status. The initiators checked to see whether there were other agents at the same location. The rest of the procedures were identical to the heterosexual procedures, except that the agents only chose those with the same sex as potential short-term mates or long-term partners.

Simulations

The model was run for 1,000 time steps in each simulation. We ran 10,000 simulations for each experiment, including 2,500 simulations for each condition, and 100 simulations for all sensitivity analyses. We controlled for initializing random seeds in the model runs. All simulations were run using Netlogo 6.2.1 (Wilensky, Citation1999).

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.3 (R Core Team, Citation2022) and the figures were generated by the ggplot2 package (Wickham, Citation2016). Two-tailed independent samples t-tests were used for all statistical comparisons. The data were assumed to be normally distributed within each condition.

Results

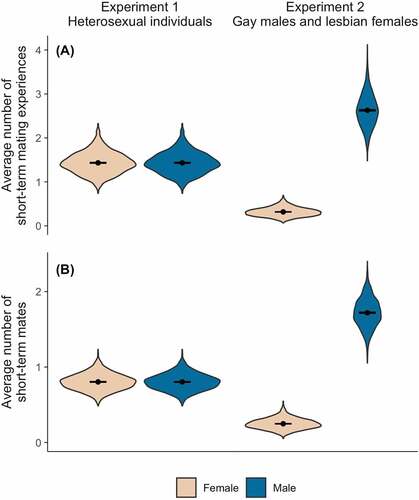

Sex Differences in Short-term Mating Behaviors in the Full Population

The results from Experiment 1 showed that when there were sex differences in preferences for short-term mating, there was no sex difference in the average number of short-term mating experiences among the full population of heterosexual individuals (Mmale = 1.43, SDmale = 0.24; Mfemale = 1.43, SDfemale = 0.24), 95% CI = – 0.01 to 0.01,Footnote1 Cohen’s d = 0.00. Nor was there a difference in the average number of short-term mates (Mmale = 0.80, SDmale = 0.11; Mfemale = 0.80, SDfemale = 0.11), 95% CI = – 0.01 to 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.00 ().

Figure 1. Short-term mating behaviors of males and females after 1,000 time steps in the model when sex differences existed in mating preferences.

The results from Experiment 2 showed that when there were sex differences in preferences for short-term mating, there were sex differences in short-term mating behaviors between gay males and lesbian females (). The average number of short-term mating experiences was higher among gay males (M = 2.63, SD = 0.37) than among lesbian females (M = 0.32, SD = 0.10), t(4,998) = – 301.78, p < .001, 95% CI = – 2.33 to – 2.30, Cohen’s d = 8.54.Footnote2 Similarly, the average number of short-term mates was higher among gay males (M = 1.72, SD = 0.19) than among lesbian females (M = 0.25, SD = 0.07), t(4,998) = – 357.69, p < .001, 95% CI = – 1.48 to – 1.46, Cohen’s d = 10.12.

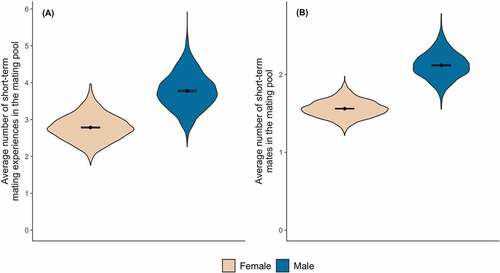

Heterosexual Individuals in the Mating Pool

In Experiment 1, there was a smaller proportion of heterosexual males in the mating pool (M = 0.38, SD = 0.04) compared to females (M = 0.51, SD = 0.05), t(4,998) = 104.85, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.13 to 0.14, Cohen’s d = 2.97. In this population, there were sex differences in short-term mating behaviors when males and females had differential preferences for short-term mating (). The average number of short-term mating experiences was higher among heterosexual males (M = 3.78, SD = 0.50) than among heterosexual females (M = 2.79, SD = 0.35), t(4,998) = – 81.53, p < .001, 95% CI = – 1.02 to – 0.97, Cohen’s d = 2.31. Likewise, the average number of short-term mates was higher among heterosexual males (M = 2.12, SD = 0.17) than among heterosexual females (M = 1.56, SD = 0.11), t(4,998) = – 135.85, p < .001, 95% CI = – 0.57 to – 0.55, Cohen’s d = 3.84.

Figure 2. Short-term mating behaviors of heterosexual males and females in the mating pool after 1,000 time steps in the model when sex differences existed in mating preferences.

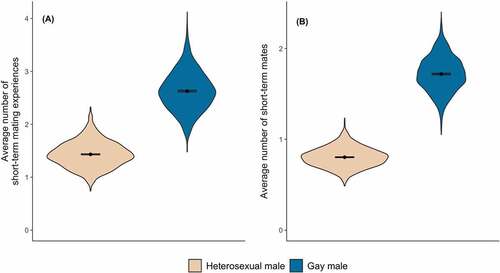

Comparing Heterosexual and Gay Males

Gay males engaged in short-term mating behaviors more than heterosexual males did (). The average number of short-term mating experiences (calculated using the full population of males) was higher among gay males (M = 2.63, SD = 0.37) than among heterosexual males (M = 1.43, SD = 0.24), t(4,998) = – 134.87, p < .001, 95% CI = – 1.21 to – 1.18, Cohen’s d = 3.81. Similarly, the average number of short-term mates (calculated using the full population of males) was higher among gay males (M = 1.72, SD = 0.19) than among heterosexual males (M = 0.80, SD = 0.11), t(4,998) = – 206.91, p < .001, 95% CI = – 0.92 to – 0.91, Cohen’s d = 5.85.

Figure 3. Short-term mating behaviors of heterosexual males and gay males after 1,000 time steps in the model when sex differences existed in mating preferences.

Experimental Conditions Giving Rise to Sex Differences in Short-term Mating Behaviors

We also ran analyses across conditions to see which of the two dimensions of mating preferences contributed to sex differences in short-term mating behaviors.

Among heterosexual individuals, sex differences in short-term mating behaviors, when calculated among individuals in the mating pool, emerged when males and females had different standards for short-term mates. Heterosexual males (vs. heterosexual females) in the mating pool had a higher average number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates as long as they had lower mating standards, even when no sex difference existed in short-term mating likelihood (experiences: Mmale = 2.82, SDmale = 0.36, Mfemale = 2.21, SDfemale = 0.28, Cohen’s d = 1.89; partners: Mmale = 1.76, SDmale = 0.15; Mfemale = 1.38, SDfemale = 0.09, Cohen’s d = 3.13). In comparison, virtually no sex differences in short-term mating behaviors existed when males and females had the same mating standards ().

Table 1. Short-term mating behaviors of heterosexual males and females in the mating pool after 1,000 time steps in the model.

Among gay males and lesbian females, sex differences in short-term mating behaviors emerged both when they had different short-term mating likelihood and when they had different mating standards. Gay males (vs. lesbian females) had a higher average number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates when they had a higher short-term mating likelihood (experiences: Mmale = 0.80, SDmale = 0.23, Mfemale = 0.32, SDfemale = 0.10, Cohen’s d = 2.67; partners: Mmale = 0.52, SDmale = 0.13, Mfemale = 0.25, SDfemale = 0.07, Cohen’s d = 2.60), or when they had lower mating standards (experiences: Mmale = 1.05, SDmale = 0.18, Mfemale = 0.32, SDfemale = 0.10, Cohen’s d = 5.10; partners: Mmale = 0.82, SDmale = 0.12, Mfemale = 0.25, SDfemale = 0.07, Cohen’s d = 5.78). In comparison, virtually no sex differences in short-term mating behaviors existed when gay males and lesbian females had the same short-term mating likelihood and mating standards ().

Table 2. Short-term mating behaviors of gay males and lesbian females after 1,000 time steps in the model.

Sensitivity Analyses

To show the robustness of the above results, we ran additional sensitivity analyses across different likelihood values of forming long-term relationships. The sensitivity analyses replicated the results. We reported the detailed statistics from the sensitivity analyses in the Section C of the Supplemental Materials (https://osf.io/4kf26/).

Discussion

The present study used agent-based modeling to investigate whether males' and females’ differential preferences for short-term mating would result in sex differences in short-term mating behaviors, and if so, then under what conditions they would result in differences in the number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates. We formulated five hypotheses: 1) there would be no sex differences in short-term mating behaviors between heterosexual males and females when considering the full population, 2) a smaller proportion of heterosexual males (vs. heterosexual females) would have ever engaged in short-term mating, 3) in a population of heterosexual individuals who had any short-term mating, males would have a higher average number of short-term mating behaviors than females, 4) gay males would engage in more short-term mating behaviors compared to lesbian females, and 5) compared to heterosexual males. The results from 1,000 time steps in a model simulating males' and females’ mating behaviors provided strong evidence in favor of our hypotheses. First of all, we found no sex differences in short-term mating behaviors between heterosexual males and females when the full population was considered. However, compared to heterosexual females, there was a smaller proportion of heterosexual males participating in the mating pool, but they had higher average numbers of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates. Secondly, gay males had higher average numbers of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates compared to both lesbian females and heterosexual males.

As expected, when all individuals in the population were considered, heterosexual males and females did not differ in short-term mating behaviors despite their differential preferences for short-term mating. This is not surprising since the sex ratio was 1:1 in our model. Heterosexual males and females had an equal total number of both short-term mating experiences and short-term mates. It therefore follows that the average number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates must be equal between males and females as well. However, we did find that when we only looked at individuals in the mating pool (from which more males than females were excluded), males engaged in more short-term mating behaviors compared to females. This was because there were more females than males in the mating pool, resulting in lower averages among heterosexual females despite the equal numbers of experiences and mates in total.

Moreover, sex differences in short-term mating behaviors emerged among individuals in the mating pool when heterosexual males and females had different mating standards, but not when they had different short-term mating likelihood. When females had a higher standard than males, less males than females in the population were above a potential partner’s standard and thus had a chance to have sex with them. This contributed to the unequal number of males and females in the mating pool, which led to sex differences in short-term mating behaviors among this population. In comparison, when males and females had different short-term mating likelihood, the probability of any pair of them ending up having sex is always the product of their individual likelihood (since males and females made decisions independently). As this probability is the same for both parties, the sex difference in short-term mating likelihood did not translate into different behaviors.

In the light of these results, previous empirical observations of sex differences in short-term mating behaviors among heterosexual individuals (e.g., Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010) appear perplexing (e.g., Gurman, Citation1989). Possible explanations for these empirical results that seem illogical considering the simulation findings may include but are not limited to the following features of the observation process. One possibility is sampling bias in the observations (e.g., Wiederman & Dubois, Citation1998) since surveys regarding short-term mating behaviors may tend to attract individuals who already engage in such behaviors. Our results suggest that when this group of individuals is considered, there can be sex differences in short-term mating behaviors that do not exist in the full population. A second explanation is that heterosexual men’s and women’s self-reported sexual behaviors are affected by social desirability bias due to gender norms. Men may overreport since having more sexual partners can show their masculinity and yield them reputation benefits, while women may underreport because this violates the chastity norm (Fisher, Citation2013). A third explanation is that men and women have different estimation strategies of their sexual experiences. Men may tend to approximate and round up, while women’s tendency to count instances may lead to lower estimations (Brown & Sinclair, Citation1999; Mitchell et al., Citation2019).

Among gay males and lesbian females, large sex differences in short-term mating behaviors existed when males and females had differential preferences for short-term mating, which was in line with empirical observations (e.g., Peplau et al., Citation1997, Citation2004). This was likely because the number of short-term mating experiences and short-term mates no longer counted toward males and females simultaneously. Any sex differences in mating preferences would result in differences in behaviors. A closer look at the results did support this postulation. Both a difference in the likelihood of short-term mating and in mating standards alone resulted in sex differences in mating behaviors. This was likely because the former increased the probability of both parties of any gay couple deciding to have short-term mating, and the latter increased the probability of both meeting each other’s standards, compared to the case of a lesbian couple.

Also, as gay males’ preferences for short-term mating were not constrained by those of females, we found that gay males engaged in more short-term mating behaviors compared to heterosexual males. This was consistent with the empirical literature (e.g., Peplau et al., Citation1997). Interestingly, gay males and heterosexual males had the same short-term mating likelihood and the same standards for short-term mates in our model. The only difference was a change in the preferences of potential partners. When males’ partners had stronger preferences for short-term mating (i.e., having males vs. having females as potential partners), males also appeared to engage in more short-term mating behaviors.

Conclusion

Using agent-based modeling to simulate short-term mating behaviors, we found when males (vs. females) had stronger preferences for short-term mating, heterosexual males and females engaged in short-term mating behaviors to the same extent when all individuals in the population were considered. However, among individuals who participated in the mating pool, males had more such behaviors than females. Gay males engaged in more short-term mating behaviors compared to both lesbian females and heterosexual males. Our results highlight the distinction between preferences and behaviors in human mating. Individuals’ mating behaviors do not only depend on one’s own preferences but are also constrained by partners’ preferences.

The present study had several implications for future research. First, research on human short-term mating behaviors should not only focus on the psychological aspect of human mating but should also pay attention to the interaction between individuals’ psychology and its behavioral context. Second, the results cast doubt to the prevalent belief in the sex differences in short-term mating behaviors, especially among heterosexual individuals. Our findings suggest that there may be other factors in the observation process, such as sampling bias, that contribute to the observed differences. Future research in human sexuality should note such possibilities and interpret any observed sex differences in short-term mating behaviors with caution. In addition, we noticed the lack of research on estimating the probability of a pair of individuals forming a long-term relationship and suggest future research to tackle this empirical question. Finally, since we only examined the consequences of people’s preferences, future work can extend to other factors that can affect mating behaviors such as life strategies, environmental pressure for reproduction, and their interactions (Figueredo et al., Citation2004).

Data Availability

All model, data, analysis code, and supplemental materials are available at: https://osf.io/4kf26/.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (19.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Jiannan Shi and Gu Li for providing helpful feedback in the development of this study. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2183485

Notes

1 The confidence intervals reported in this paper are of the differences between the group means under comparison.

2 We thank an anonymized reviewer for pointing out that some observed effect sizes in this study are unusually large. We postulate that this was because there was less variance in our simulated data compared to empirically collected data. There were no measurement errors in the data, and we omitted many factors from the model that might affect short-term mating behaviors. For example, we modeled desirability and mating standards using monotonic scales, but there are many dimensions of these two variables (e.g., appearance, socioeconomic status, age, etc.). This may contribute to greater variance in short-term mating behaviors in a more realistic setting that we were unable to represent in a simplistic model, which can decrease the effect size.

References

- Archer, J. (2019). The reality and evolutionary significance of human psychological sex differences. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 94(4), 1381–1415. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12507

- Bailey, J. M., Gaulin, S., Agyei, Y., & Gladue, B. A. (1994). Effects of gender and sexual orientation on evolutionarily relevant aspects of human mating psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(6), 1081–1093. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.6.1081

- Brown, N. R., & Sinclair, R. C. (1999). Estimating number of lifetime sexual partners: Men and women do it differently. The Journal of Sex Research, 36(3), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499909551999

- Bryant, A. S., & Demian, D. (1994). Relationship characteristics of American gay and lesbian couples. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 1(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J041v01n02_06

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204d

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2019). Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 77–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103408

- Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., Ziegler, A., & Valentine, B. A. (2011). Women, men, and the bedroom: Methodological and conceptual insights that narrow, reframe, and eliminate gender differences in sexuality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(5), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411418467

- de Menezes Gomes, R., de Araújo Lopes, F., & Castro, F. N. (2020). Influence of sexual genotype and gender self-perception on sociosexuality and self-esteem among transgender people. Human Nature, 31(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-020-09381-6

- Figueredo, A. J., Vasquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., & Schneider, S. M. (2004). The heritability of life history strategy: The k-factor, covitality, and personality. Social Biology, 51(3–4), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2004.9989090

- Fisher, T. D. (2013). Gender roles and pressure to be truthful: The bogus pipeline modifies gender differences in sexual but not non-sexual behavior. Sex Roles, 68(7), 401–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0266-3

- Ghaznavi, C., Sakamoto, H., Yoneoka, D., Nomura, S., Shibuya, K., & Ueda, P. (2019). Trends in heterosexual inexperience among young adults in Japan: Analysis of national surveys, 1987– 2015. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6677-5

- Gurman, S. J. (1989). Six of one …. Nature, 12, 342. https://www.nature.com/articles/342012d0

- Hald, G. M., & Høgh-Olesen, H. (2010). Receptivity to sexual invitations from strangers of the opposite gender. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(6), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.07.004

- Haydon, A. A., Cheng, M. M., Herring, A. H., McRee, A.-L., & Halpern, C. T. (2014). Prevalence and predictors of sexual inexperience in adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0164-3

- Herbenick, D., Bowling, J., Fu, T.-C. (Jane), Dodge, B., Guerra-Reyes, L., Sanders, S., Ghaznavi, C., Sakamoto, H., Yoneoka, D., Nomura, S., Shibuya, K., & Ueda, P. (2017). Sexual diversity in the United States: Results from a nationally representative probability sample of adult women and men. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0181198. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181198

- Kenrick, D. T., Sadalla, E. K., Groth, G., & Trost, M. R. (1990). Evolution, traits, and the stages of human courtship: Qualifying the parental investment model. Journal of Personality, 58(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00909.x

- Matsick, J. L., Kruk, M., Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., & Ziegler, A. (2021). Gender similarities and differences in casual sex acceptance among lesbian women and gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(3), 1151–1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01864-y

- McBurney, D. H., Zapp, D. J., & Streeter, S. A. (2005). Preferred number of sexual partners: Tails of distributions and tales of mating systems. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.09.005

- Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Prah, P., Clifton, S., Tanton, C., Wellings, K., & Copas, A. (2019). Why do men report more opposite-sex sexual partners than women? Analysis of the gender discrepancy in a British national probability survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1481193

- Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 29–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.29

- Peplau, L. A., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. (1997). A national survey of the intimate relationships of African American lesbians and gay men: A look at commitment, satisfaction, sexual behavior, and HIV disease. In B. Greene (Ed.), Ethnic and cultural diversity among lesbians and gay men (pp. 11–38). Sage Publications.

- Peplau, L. A., Fingerhut, A., & Beals, K. P. (2004). Sexuality in the relationships of lesbians and gay men. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 349–369). Erlbaum.

- Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Regan, P. C. (1998). Minimum mate selection standards as a function of perceived mate value, relationship context, and gender. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 10(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v10n01_04

- Rissel, C., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M. A., Richters, J., Visser, R. O., De, Grulich, A. E., Simpson, J. M., Rissel, C., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M. A., Richters, J., Visser, R. O., De, Grulich, A. E., & Simpson, J. M. (2014). Heterosexual experience and recent heterosexual encounters among Australian adults: The second Australian study of health and relationships. Sexual Health, 11(5), 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14105

- Schmitt, D. P. (2003). Universal sex differences in the desire for sexual variety: Tests from 52 nations, 6 continents, and 13 islands. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.85

- Schmitt, D. P., Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2001). Are men really more ‘oriented’ toward short-term mating than women? A critical review of theory and research. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 3(3), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616660110119331

- Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. Oxford University Press.

- Walter, K. V., Conroy-Beam, D., Buss, D. M., Asao, K., Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., Aavik, T., Akello, G., Alhabahba, M. M., Alm, C., Amjad, N., Anjum, A., Atama, C. S., Atamtürk Duyar, D., Ayebare, R., Batres, C., Bendixen, M., Bensafia, A., Bizumic, B., … Zupančič, M. (2020). Sex differences in mate preferences across 45 countries: A large-scale replication. Psychological Science, 31(4), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620904154

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org

- Wiederman, M. W., & Dubois, S. L. (1998). Evolution and sex differences in preferences for short- term mates: Results from a policy capturing study. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19(3), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00006-3

- Wilensky, U. (1999). NetLogo. Center for Connected Learning; Computer-Based Modeling. http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/