ABSTRACT

Through two experimental studies (N = 150), we investigated proxemic behaviors featuring gay/straight dyadic interactions. In doing so, for the first time, we relied on an IR depth camera and considered the interpersonal volume between the interactants, a novel feature that exhaustively captures interactants’ proxemic behaviors. Study 1 revealed that the straight participants’ implicit sexual bias – but not the explicit prejudice – significantly predicted their volume while interacting with a study accomplice who was presented as gay (vs. straight). However, unlike previous research, mixed-model analyses revealed the higher their implicit bias was, the smaller the interpersonal volume that they maintained with the gay study accomplice, especially when the conversation focused on an intergroup-related (vs. neutral) topic. Study 2 was mainly designed to deepen this main finding. Results documented that highly implicitly biased participants who maintained a smaller interpersonal volume with a gay (vs. straight) study accomplice were more cognitively depleted after the interaction than low-biased participants, possibly suggesting that highly implicitly biased straight people can control this nonverbal behavior to appear as nonprejudiced in the gay interactant’s eyes. Implications for research on sexual prejudice and intergroup nonverbal behaviors are discussed.

Proxemic behaviors refer to the way people utilize, structure, and orient themselves within the space around them during social interactions. They are an essential part of human communication (e.g., Siegman & Feldstein, Citation2014) that deeply shape the perceived quality of the interaction, often at a level outside individuals’ awareness (e.g., Chen & Bargh, Citation1997). Given their practical and theoretical importance, these behaviors have increasingly been studied by social psychologists in the context of interactions between individuals belonging to different social groups. Similar to other types of nonverbal behaviors, in some cases intergroup proxemic behaviors lead to more strained and unpleasant interaction outcomes than proxemic behaviors between members of the same group (e.g., Dovidio et al., Citation2002). So far, research on intergroup proxemics has mainly focused on interethnic relations, while neglecting this nonverbal behavior within the setting of face-to-face encounters between gay and straight people. To fill this gap, the present work aimed at analyzing antecedents of people’s proxemic behaviors during interactions between straight and gay men. More specifically, we explored whether individual (i.e., sexual prejudice) and situational (i.e., the topic of the conversation) variables would shape their interpersonal volume, which is a novel index that comprehensively captures people’s proxemic behaviors during dyadic interactions. In doing so, for the first time in this field, we employed an IR-depth camera (i.e., the Microsoft Kinect V.2 sensor), that allowed us to obtain a quantitative pattern of this intergroup nonverbal behavior in a fully automatic and non-invasive way during face-to-face interactions.

Proxemic Behaviors During Interpersonal and Intergroup Interactions: Their Meaning and Assessment

Interpersonal distance is considered the most informative aspect of individuals’ proxemics during dyadic interactions, revealing the levels of relational intimacy and deeply affecting the perceived quality of the interaction (Hall, Citation1966). Although the use of physical space during face-to-face interactions is affected by cultural factors (e.g., Sorokowska et al., Citation2017), literature on nonverbal behaviors has commonly maintained and found that the larger the interpersonal distance the individual maintains toward the interactant, the greater is her psychological distance toward this person (see e.g., La Varvera, Citation2013). Inversely, the smaller the interpersonal distance, the greater the psychological intimacy. Such an assumption has been also generally confirmed during intergroup interactions, at least when considering interethnic settings. That is, converging evidence has documented that ethnic majority group members tend to stay more distant when interacting with an ethnic minority (vs. majority) study accomplice (Dovidio et al., Citation1997, Citation2002; Goff et al., Citation2008; Palazzi et al., Citation2016; Trawalter & Richeson, Citation2006), although this effect is moderated by individual and situational factors that will be better outlined below.

Despite the relevance of physical distance to signal the immediacy between interactants, its operationalization is yet quite weak, especially within the intergroup literature, and does not exhaustively capture the general concept of proxemics. That is, it has been mostly limited to a static assessment of the distance maintained by the social actors, that for instance, implied the metrical assessment of a chair placed by a given participant with the chair of her conversation partner (e.g., Goff et al., Citation2008). However, the interactants’ proxemics is somewhat more complex than a static measure of their physical distance, mainly because it is negotiated by both interactants and constantly regulated throughout the interaction. Accordingly, Palazzi et al. (Citation2016) recently proposed and validated the interpersonal volume as a novel feature of proxemic intergroup behaviors, which has been shown to convey the physiological levels of intimacy between two interactants more comprehensively and dynamically than interpersonal distance. Specifically, interpersonal volume is a 3D measure that captures simultaneously the interpersonal distance between the interactants together with the continuous movements of a given interactant towards the other during the interaction. In their study that involved interactions between White participants and Black (vs. White) study accomplices, they found that both the interpersonal volume and distance maintained by participants towards study accomplices significantly correlated – and to a similar degree – with participants’ implicit bias. However, interpersonal volume displayed significant associations also with inner participants’ psychological states, such as stress-related indexes, suggesting that this novel index can capture more exhaustively the psychological intimacy between interactants, than the “simpler” measure of distance.

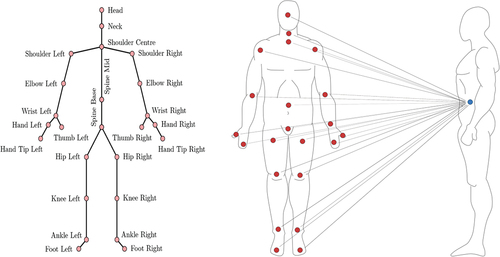

Notably, the conceptualization and assessment of this new proxemic index have been possible thanks to the use of IR-depth camera technologies, which in the last few years has allowed scholars to obtain quantitative measures of interactants’ body movements over the entire course of the interaction. In particular, the Microsoft Kinect V.2 Sensor is a type of IR-depth camera that has been increasingly employed in empirical research to validate and extract nonverbal behaviors during dyadic interactions (see Baur et al., Citation2013; Burba et al., Citation2012; Frauendorfer et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2013; Palazzi et al., Citation2016). Through an infrared projector combined with an infrared camera, the Kinect sensor continuously and unobtrusively records the 3D coordinates of 25 body joints of the individual during the interaction. Then, specific algorithms are applied to the recorded 3D coordinates to obtain measures of specific nonverbal behaviors (for procedural examples of algorithm calculation, see Gatica-Perez et al., Citation2007; Palazzi et al., Citation2016). Inspired by these conceptual and methodological advances, in our studies we employed the Microsoft Kinect V.2 Sensor to analyze the intergroup nonverbal behavior within dyadic straight/gay interactions. More specifically, through this sensor, we investigated the interpersonal volume maintained by straight people while interacting with a gay study accomplice.

Individual and Situational Variables Shaping Intergroup Nonverbal Behaviors and Proxemics

Similar to other forms of intergroup nonverbal behaviors, proxemics is largely dependent on individual and situational variables that feature intergroup interactions. People bring into these interactions prior experiences, attitudes, or beliefs toward the outgroup, that are often expressed in terms of nonverbal behaviors. In their influential Model of Mixed Social Interactions, Hebl and Dovidio (Citation2005) identified a series of personal variables that interact with experiential (e.g., previous experiences of intergroup contact) and relational-situational (e.g., power relations during the interaction) factors in affecting the course of the interaction, both in terms of verbal and nonverbal behaviors.

People’s prejudice toward the outgroup is considered the most relevant personal factor in predicting how people behave during intergroup interactions (e.g., Shelton et al., Citation2009). However, implicit and explicit forms of prejudice differently affect people’s behaviors during the interaction. Explicit prejudice specifically predicts bias in verbal or intentional attitudes and behaviors, whereas implicit bias is more commonly associated with spontaneous and less controllable forms of behaviors, including intergroup nonverbal behaviors. Despite being mainly confined to interethnic settings, a good amount of literature has provided convergent evidence for these assumptions (see Dovidio et al., Citation2006 for a review). For example, Dovidio et al. (Citation1997; see also Dovidio et al., Citation2002) found that White participants’ self-reported levels of prejudice were associated with more negative evaluations of the interaction with an Afro-American partner, whilst higher levels of implicit bias were associated with specific intergroup nonverbal behaviors conveying signals of discomfort (i.e., higher rate of eye blinking and less eye contact) or decreased friendliness. In the same intergroup setting, McConnell and Leibold (Citation2001) reported that White interactants with higher levels of implicit bias spoke less, displayed more speech hesitations, and committed more speech errors when interacting with an Afro-American study accomplice, whilst their explicit levels of prejudice did not correlate with these intergroup nonverbal behaviors. Most interestingly for our studies, converging evidence has also revealed that implicit (vs. explicit) prejudice is a key antecedent of interpersonal distance during intergroup encounters: especially White people with higher (vs. lower) levels of implicit bias tend to stay more distant when interacting with a Black (vs. White) study accomplice (Dovidio et al., Citation1997, Citation2002; Goff et al., Citation2008; Palazzi et al., Citation2016; Trawalter & Richeson, Citation2006).

Taken together, the findings above shed some light on intergroup nonverbal behaviors and proxemics regulating interethnic interactions. Instead, comparatively less research has investigated these behaviors during interactions between gay and straight people. In particular, Knöfler and Imhof (Citation2007) found a different pattern of intergroup nonverbal behaviors when observing interactions with at least one gay person involved in the interaction, compared to purely straight dyads. That is, the participants in mixed dyads enacted a greater amount of self-adaptive behaviors (e.g., face-touch) and fewer and shorter gazes at their partner than participants involved in straight dyads. Although not directly investigating intergroup nonverbal behaviors, Hebl et al. (Citation2002) reported that naïve straight employers spent less time and used fewer words when interacting with a study accomplice who presented himself as gay than a straight applicant. Cuenot and Fugita (Citation1982) explored the predictive role of sexual prejudice in shaping intergroup nonverbal behaviors during gay/straight dyadic interactions. In their study, straight participants interacted with a male or a female study accomplice, portrayed as gay or straight depending on the condition. Results indicated that participants had similar visual interaction patterns with both the gay and the straight study accomplice, but, regardless of the level of explicit prejudice, spoke faster to the gay one, a sign that was interpreted as anxiety. In a more recent and comprehensive set of studies, Dasgupta and Rivera (Citation2006) tested the relation between implicit bias and intergroup nonverbal behaviors in dyadic interactions between a straight participant and a study accomplice presented as gay or straight, depending on the condition. Confirming previous evidence coming from interethnic settings, in their two experiments they showed that implicit measures better predicted intergroup nonverbal behaviors enacted by participants than explicit measures did. Interestingly, they also showed that people under certain conditions can be motivated to correct such behavior and control it. That is, they demonstrated that when conscious egalitarian beliefs were activated, participants were more prone to control and inhibit potential negative intergroup nonverbal behaviors, regardless of their implicit bias. Instead, implicit bias predicted participants’ intergroup nonverbal behaviors (e.g., they smiled less or maintained less relaxed body posture) when such beliefs were not salient, or participants were unable to control their behaviors.

Thus, apart from the few studies mentioned above, the literature on intergroup nonverbal behaviors featuring straight/gay interactions is scarce, especially if considering the relevance of these behaviors for the perceived quality of intergroup interaction. Further, to our knowledge, within this intergroup setting, no studies have explored the antecedents shaping proxemic behavior between interactants, one of the most prominent nonverbal behavior featuring face-to-face interactions and their outcomes. In particular, little is known about the possible role of implicit (vs. explicit) sexual prejudice in affecting this behavior. This latter issue is highly relevant, especially in today’s western societies: even if most social and institutional walls are now eliminated, prejudice toward those who identify or appear LGBTQ+ is still pervasive (Herek & McLemore, Citation2013) and negatively affects the nature of the intergroup relation. For example, Kiebel et al. (Citation2020) documented that feminine gay men are still perceived as low in naturalness and highly homogenous, and that this view deeply increases straight people’s prejudice against them. In the same vein, recent findings revealed that the stereotype depicting gay men as insufficiently masculine (Hunt et al., Citation2016) and homophobic epithets (Fasoli et al., Citation2016) still endure in our societies and deeply contribute to social distancing and discrimination against them.

The overall goal of the present work was to expand these pieces of evidence on the consequences of (implicit) sexual prejudice, by specifically exploring its role in shaping straight people’s proxemic behavior, in terms of interpersonal volume, when interacting with gay men. Further, we analyzed this personal variable when interplaying with a situational variable, i.e., the topic of the conversation, in affecting this behavior. Indeed, research on intergroup nonverbal behaviors revealed that, at least within interethnic interactions, the topic of the conversation is an important situational variable that often interacts with implicit bias in affecting the amount of physical distance maintained by the majority group member toward the minority one (see Trawalter et al., Citation2009 for a review). That is, majority members tend to physically distance more minority partners when the conversation centers around topics that are relevant (vs. non-relevant) for the intergroup relation. In fact, intergroup-related discussions are commonly perceived as threatening and thus elicit intergroup nonverbal behaviors linked with avoiding or discomfort, including increased physical distance. Drawing from these assumptions, here we investigated for the first time whether also in straight/gay interactions the topic of the conversation would affect the interactants’ proxemic behaviors, by considering a more exhaustive index of this behavior than interpersonal distance, i.e., interpersonal volume. In doing so, we assumed that straight people would maintain a larger interpersonal volume when the conversation focused on intergroup-related (vs. neutral) topics.

Overview and Hypotheses of the Present Research

We designed two experimental studies to address the aims outlined above. In both studies, straight participants were first assessed for their levels of explicit and implicit sexual bias. Following this, in Study 1 all of them were asked to have two brief face-to-face conversations – one salient and one non-salient for the intergroup relation – with a male study accomplice who was introduced as a gay or straight man, depending on the experimental condition. All conversations were recorded by the Microsoft Kinect v2 sensor. Then, we extracted a quantitative index of the participants’ proxemics in terms of interpersonal volume during the conversations. Study 2 was mainly conducted to expand the findings of Study 1. First, in this study, we increased the generalizability and ecological validity of our research by involving study accomplices who were not just presented as gay (vs. straight) men, but were indeed gay (vs. straight) men. Second, and more importantly, in Study 2 we added a measure of cognitive performance (i.e., a Stroop color-naming task) aimed at measuring the participants’ cognitive depletion following the conversations. This crucial outcome variable was introduced after observing the main findings of Study 1 and to empirically test whether different participants’ proxemics in terms of regulation of their interpersonal volume would then impact their cognitive resources.

Due to the lack of specific literature on sexual prejudice and people’s proxemics during straight/gay interactions, our hypotheses were mainly drawn from the literature on interethnic nonverbal behaviors. That is, we hypothesized that:

H1a: the participants’ implicit bias – but not the explicit prejudice – would predict a larger interpersonal volume while they were interacting with a study accomplice presented as gay (vs. straight; Study 1) or actually gay (vs. straight; Study 2).

H1b: an such effect should be moderated by the situational variable concerning the conversation topic, i.e., held true (or be stronger) when interactants discussed a topic related to LGB issues (intergroup-related topic) than a neutral one.

H2: the different amount of interpersonal volume that straight participants maintained when interacting with the gay study accomplice (vs. straight) would affect their cognitive resources, depending on their levels of implicit sexual (vs. explicit) bias and the topic of the conversation (Study 2).

Study 1

Study 1 was conducted to provide the first evidence about H1a and b. That is, we expected a three-way interaction between the study accomplice’s sexual orientation, implicit – but not explicit – prejudice, and the conversation topic so that participants’ implicit bias would predict a larger interpersonal volume during the interaction with the study accomplice presented as gay (vs. straight; H1a), especially when discussing a topic related to the intergroup relation (vs. a neutral topic; H1b). As after research suggested that the mere perception that someone is gay (or lesbian) can affect straights’ attitudes and behaviors per se (e.g., Herek et al., Citation2002; Lick & Johnson, Citation2014; Lick et al., Citation2014), in Study 1 the study accomplice’s sexual orientation was manipulated: we involved straight collaborators who were presented as gay or straight to the participants, depending on the experimental condition.

Method

Participants and Experimental Design

A power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., Citation2007) suggested that we needed a sample of at least 82 participants to observe a medium effect size (f = 0.25, with α = .05, power = .80) according to our 2 (study accomplice’s sexual orientation: gay vs. straight) × 2 (conversation topic: intergroup-related vs. neutral) mixed experimental design, with the study accomplice’s sexual orientation as a between-subjects factor and the conversation topic as a within-subjects factor. As we expected a substantial participant loss due to their possible non-straight sexual orientation and data loss due to equipment failure – which is still a common risk when using automated recording devices (see e.g., Chen et al., Citation2015) – the initial sample consisted of 95 participants. They were undergraduates from a large university in the North-West of Italy not attending psychology courses, who were recruited voluntarily by research assistants via e-mail or private messages on social networks. As expected, six participants revealed a non-heterosexual sexual orientation and were, thus, excluded from the main analyses. Seven participants were also excluded, as in the attentional check item they were not able to recall the study accomplice’s sexual orientation. Lastly, we experienced data loss while recording the interaction of four other participants. Hence, the final sample consisted of 78 straight participants (38 women; Mage = 21.30; SD = 2.02).

Procedure and Measures

Participants were individually examined in two main experimental phases and they were told that the research focused on attitudes toward different social groups and impression formation during dyadic interactions. In the first phase, participants were brought to a first room, where their explicit prejudice and implicit bias were assessed. Explicit prejudice was measured with the Italian adaptation of the Attitudes Toward Gay men subscale (Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay men scale, ATLG; Herek, Citation1988). Participants had to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with the 10 statements of the ATG subscale (e.g., “Gay men are disgusting,” “Sex between two men is just plain wrong”) using a 7-step Likert scale (1 = not at all; 7 = extremely). Total scores were obtained by averaging the 10 items (α = .85) so that higher scores indicated higher explicit prejudice towards gay men. Along with the ATG subscale, measures of prejudice towards other minority groups were included as filler scales (e.g., Ethnic Prejudice Scale, Wagner et al., Citation2006), to prevent participants from immediately focusing on the investigated intergroup relation. Afterward, participants’ implicit sexual bias was assessed through an adapted version of the Sexuality IAT (Nosek & Smyth, Citation2007; see also e.g., Anselmi et al., Citation2013; Steffens, Citation2005). A Gay version of the task was created, and participants were requested to categorize as fast and accurately as possible gay- vs. straight-related images or words (e.g., homosexual vs. heterosexual) with positive (e.g., pleasure) vs. negative (e.g., agony) words using two separate keys of the keyboard. The set of images and words was obtained from the Project Implicit Website (https://www.projectimplicit.net/). For the word stimuli, we considered the Italian translation of terms like “homosexual,” “gay,” “heterosexual,” and “straight.” For images, stimuli were “cake topper” wedding figures (depicting an opposite-sex couple or a male-male couple) or bathroom signs (portraying a man and a woman or two men). In the compatible critical block, gay-related words or images and negative words shared the same response key (e.g., E keyboard button), while straight-related words or images and positive words shared the other response key (e.g., I keyboard button). In the incompatible critical block, gay-related words or images and positive words shared the same response key, while straight-related words or images and negative words shared the other response key. The two critical blocks were counterbalanced across participants. An IAT d-score index was then computed (see Greenwald et al., Citation2003), such that higher positive scores indicated higher levels of implicit bias against gay people. After completing the explicit and implicit measures of sexual prejudice, participants were told that they were going to converse with another participant to study the impression-formation process during dyadic interactions. Before the interaction, they were shown a fictitious Facebook profile page in which the study accomplice’s sexual orientation was made salient. In particular, the profile page portrayed the study accomplice as engaged in a straight or gay relationship, depending on the experimental condition. Participants were asked to memorize the information included in the Facebook profile, as this was useful to have an initial acquaintance with the future interactant. To increase the generalizability of the tested effects, two heterosexual male students were involved as study accomplices, which, similar to Dasgupta and Rivera’s (Citation2006) procedure, played both roles (gay vs. straight) and were unaware of the experimental condition they were assigned, to ensure that their behavior would not change inadvertently as a function of the role. Furthermore, study accomplices were asked to act naturally during the interaction and not to judge the participants but to rather support the conversation.

After completing measures of explicit prejudice and implicit bias, and after receiving information about the interactant, participants were brought into another room in which they met the study accomplice they were assigned to. This room was arranged for recording and with artificial lighting on. As our research mainly focused on the participants’ nonverbal behaviors, study accomplices were asked to stand in a particular area of the room to allow the Kinect sensor to easily record the participants’ movements. After receiving instructions about the conversation topic, the participant and study accomplice were left alone in the room, standing, and free to move within the recording stage. In the interaction phase, participants had two brief conversations of three minutes each. The topics of the conversation were counterbalanced across participants and concerned an intergroup-related (i.e., the situation of the gay community in Italy) and a neutral (i.e., public transport in the participants’ city) topic. Participants and the study accomplice’s proxemics were continuously recorded during the two three-minute conversations through the Microsoft Kinect device, set on a table, approximately 1.5 meters from the interactants. The participants’ interpersonal volume was computed as the volume within the spatial coordinates of the participant (all 25 body joints) and the study accomplice’s centroid (see ) and normalized as in Palazzi et al. (Citation2016) (see the Supplementary material for details about the calculation). It was applied frame by frame to the registration and allowed us to obtain repeated measures of volume during both interactions, which were then averaged over time windows of 50 seconds, resulting in four measures for each participant and conversation. For each measure, the higher the value, the larger the volume maintained by the participant towards the study accomplice.

Figure 1. The 25 body joints tracked by a Microsoft Kinect V2 (left); Spatial representation of the Volume index (right).

Following the last conversation, participants were asked to complete the attentional check item (i.e., participants were asked to recall the sexual orientation of the study accomplice they interacted with) and to give information about their sex, age, and sexual orientation (Heterosexual, Homosexual, Other). Eventually, all participants were thanked and fully debriefed.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Explicit prejudice was relatively low across participants (M = 1.71; SD = 0.85). Notably, male participants showed higher prejudice towards gay men (M = 1.93; SD = 1.04) compared to female participants (M = 1.48; SD = 0.52), t(76) = 2.40, p = .019, Cohen’s d = 0.54. Concerning implicit bias, the average d-score was positive (M = 0.45; SD = 0.39) and statistically greater than zero, indicating the presence of implicit bias towards gay men, t(77) = 10.30, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.17, with no different levels between male and female participants, t(76) = 0.98, p = .329, Cohen’s d = 0.22.

Main Analyses

Hypotheses H1a and b were tested using a linear mixed modeling procedure (LMM; Baayen et al., Citation2008) using Jamovi (The Jamovi project, 2019, version 1.1.5.0; Gallucci, Citation2019). We opted for this statistical approach both for taking into account the non-independence of observations and because it is a particularly robust approach when dealing with missing data (Baayen et al., Citation2008), which is a possible issue when recording repeated observations with IR-depth cameras. Before the main analyses, obtained values of interpersonal volume were checked for outliers (i.e., measures deviating more than 2 SD from the mean) and normality. Apart from seven missing values due to equipment failure during the interaction registration, we did not detect any outliers. Furthermore, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the volume values of our samples were normally distributed (Z = 0.05, p = .112).

Our hypotheses were verified through two main LMMs. In the main one, implicit bias was entered as a moderator variable, the experimental condition (study accomplice’s sexual orientation: 1 = gay vs. 2 = straight), the conversation topic (1 = neutral vs. 2 = intergroup-related),Footnote1 and the intercept were entered as fixed effects, while the interpersonal volume as the outcome variable. An independent random intercept was included for each participant, to control the individual variability on the dependent variable. As previous research showed that men and women systematically differ in the amount of interpersonal distance they display during a conversation (see e.g., Bull, Citation2002; Cozzolino, Citation2003), participants’ sex was entered as a covariate, together with the study accomplice’s code and the Kinect registration time window, that resulted in four measures of 50 seconds each per conversation.

Overall, the model explained a significant portion of variance: R2 marginal = 0.39, R2 conditional = 0.88.Footnote2 As shown in , neither the study accomplice’s sexual orientation nor the participants’ implicit bias had a main effect on interpersonal distance. Instead, the topic of the conversation significantly impacted the outcome variable: regardless of the study accomplice’s sexual orientation, the interpersonal volume between the participant and study accomplice was smaller when they discussed the intergroup-related topic (M = 0.199; SD = 0.063) compared to the neutral one (M = 0.205; SD = 0.065), b = −0.005, SE = 0.002, 95%CI [−0.009, −0.001], t(532) = −2.85, p = .005. Further, the two-way interactions between the antecedent variables did not emerge as significant. However, the critical three-way study accomplice’s sexual orientation × conversation topic × implicit bias interaction was significant. In contrast to our expectations, simple slope analyses revealed that when interacting with the gay study accomplice, participants with higher levels of implicit bias (+1SD) tended to maintain a smaller interpersonal volume when discussing the intergroup-related topic compared to the neutral one, b = −0.011, SE = 0.004, 95%CI [−0.019, −0.004], t(532) = −3.12, p = .002. Instead, participants with lower levels of implicit bias (−1SD) kept a similar interpersonal volume with the gay study accomplice, regardless of the conversation topic, b = 0.003, SE = 0.004, 95%CI [−0.005, .010], t(532) = 0.726, p =.468 (see ). Although not crucial to our investigation, we also found a significant effect when the study accomplice was presented as straight, so that participants with lower levels of implicit bias (−1SD) kept a smaller interpersonal volume when the conversation focused on the intergroup rather on the neutral topic, b = −0.009, SE = 0.003, 95%CI [−0.015, −0.002], t(532) = −2.50, p = .013.

Figure 2. Interactive effects of implicit bias and topic on the discussion on participants’ volume. Gay condition. (Study 1).

Table 1. Main and interactive effects of study accomplices’ sexual orientation, conversation topic and implicit bias on interpersonal volume. Study 1.

The above pattern of findings emerged as significant despite the significant effect of the covariates, participants’ sex, and study accomplice’s code. That is, overall male participants kept a larger interpersonal volume (M = 0.23; SD = 0.06) than female participants (M = 0.17; SD = 0.04), b = −0.062, SE = 0.011, 95%CI [−0.082, −0.041], t(722) = −5.71, p < .001. Further, the participants’ interpersonal volume was different depending on the study accomplice who was involved in the interaction. Instead, the Kinect time window did not affect the participants’ volume, suggesting that it was not generally affected by the time course of the interaction.

We then ran a second LMM similar to the first one,Footnote3 in which we entered explicit prejudice rather than implicit bias as a moderator variable. Supporting our hypotheses, explicit prejudice did not affect the participants’ interpersonal volume, neither when considering its main effect, F(1, 71.9) = 1.77, p = .187, nor its two-way,(Fs ≤ 1.75, ps > .190), or three-way interactions, F(1, 532) = 0.07, p = .794 with the other main factors.

Discussion

The above results partially supported our H1, by also revealing an unexpected pattern of findings. On the one hand, as assumed, they revealed that implicit bias – but not explicit prejudice – is a key antecedent of people’s intergroup nonverbal behaviors, at least when considering a proxemics index such as interpersonal volume. On the other hand, the pattern of findings that emerged was opposite to H1a and to previous literature that considered interethnic settings. We found that when interacting with the study accomplice who was presented as gay (vs. straight) about an intergroup-related topic, the participants with higher levels of implicit sexual bias tended to stay closer to him. Thus, implicit sexual bias and the topic of the conversation oppositely impacted the participants’ proxemics compared to what we expected: instead of increasing the physical – and thus presumably the psychological – distance between the interactants, their interplay apparently decreased it. However, we reasoned about a possible alternative interpretation of these unexpected results, which could be due to the specific nature of this proxemic behavior. That is, similar to interpersonal distance, volume is a nonverbal behavior that people can intentionally control more easily than other nonverbal behaviors, such as eye blink or body motion. Thus, at least within gay/straight interactions, it is plausible to imagine that people with high levels of implicit bias intentionally use their distance to manage their self-presentation and to appear non-prejudiced in the view of their partner. As indirect support of this line of reasoning, participants’ scores on the ATG scale were particularly low, thus indicating that participants, including those with high levels of implicit bias, did not explicitly report negative attitudes towards gay men and may not want to appear prejudiced. Further, it is noteworthy that low implicitly biased participants that conversed with the straight study accomplice discussing an intergroup-related topic maintained a smaller interpersonal volume, thus indicating that under these conditions less biased people possibly had a more genuine willingness to have psychological intimacy with the interactant.

Study 2 was specifically designed to expand these findings and empirically corroborate the above assumptions.

Study 2

Study 2 adopted a similar procedure and paradigm to Study 1, with some relevant changes and additions. First, in this study, we did not just manipulate the sexual orientation of straight study accomplices, but we involved study accomplices who were indeed gay and straight men, depending on the experimental condition. In doing so, we aimed to provide a more stringent validation and generalization of our hypotheses, by setting our research into a more “realistic” and ecologically valid situation of intergroup interaction. The generalizability of the tested effects was further obtained by considering a different neutral topic of the conversation (i.e., activities and attractions for young people in one’s towns) than that used in Study 1. Third and most importantly, we detected the participants’ cognitive depletion after each conversation by employing a measure of cognitive performance (i.e., a Stroop color-naming task). This further measure was introduced to empirically verify the possible explanation proposed for the unexpected findings that emerged in Study 1. More clearly, we reasoned that if the interpersonal volume is a proxemic behavior that highly implicitly biased people can control to manage their self-presentation as non-prejudiced individuals, the efforts to control this behavior should then have a cost in terms of cognitive resources. That is, we hypothesized that the regulation of the interpersonal volume assumed when interacting with the gay (vs. straight) study accomplice would affect their cognitive resources (H2), so that the smaller the volume that high implicitly biased participants maintained with the gay study accomplice when talking about an intergroup-related (vs. neutral) topic, the greatest their cognitive depletion and, thus, the worse their performance on the subsequent cognitive task. This hypothesis is consistent with research showing that individuals with high levels of implicit prejudice find intergroup interactions more taxing as a result of the effort to control their behavior (Richeson & Shelton, Citation2003; Richeson & Trawalter, Citation2005; Richeson et al., Citation2005).

Method

Participants and Experimental Design

We employed the same 2 (study accomplice’s sexual orientation: gay vs. straight) × 2 (conversation topic: intergroup-related vs. neutral) mixed experimental design as in Study 1. The initial sample consisted of 95 participants who volunteered to take part in the study and were recruited in a similar way to Study 1. Preliminary inspection of the data led us to exclude 9 participants who belonged to sexual minorities, one participant who failed the attentional check item, and 13 participants for whom we were not able to extract their interpersonal volume from the Kinect records due to equipment failure. The final sample consisted of 72 participants (37 females; Mage = 23.30; SD = 2.64).

Procedure and Measures

Similar to Study 1, participants were first asked to complete the same measures of explicit prejudice (ATG scale; α = .91)Footnote4 and implicit bias towards gay men (Sexuality IAT – Gay version), together with other filler measures (e.g., Islamo-prejudice scale; Imhoff & Recker, Citation2012), and the Stroop color-naming task. In this task, they were instructed to match the color of various words that appeared at the center of the computer by pressing one of four color-coded buttons on the keyboard. Half of the experimental trials were incongruent: color words appeared in a font color different than its semantic meaning (e.g., the “red” word in a green font color). The remaining half of the trials were congruent: the color word appeared with the corresponding font color (e.g., the “red” word in a red font color). We considered the participants’ mean response latency for incongruent trials as their index of cognitive depletion so that the higher latencies the greater their cognitive depletion. Accordingly with the cognitive research on the Stroop task (see e.g., MacLeod, Citation1991 for a review), we specifically focused on incongruent trials as in these participants have to control their responses, by suppressing the reading response and reporting the one matching with the font color.Footnote5 Participants were then led to believe they were going to converse with another participant, who indeed was a gay or straight study accomplice depending on the experimental condition. Similar to the previous study, before the face-to-face interaction participants received information about the study accomplice’s sexual orientation through a fake Facebook profile page that made his sexual orientation salient. In this study, four male study accomplices were involved – two straight men and two gay men – who, similar to Study 1, were just asked to act naturally during the conversation.

In the interaction phase, participants had two brief conversations of the same length (i.e., three minutes each) as in Study 1 with the study accomplice. They were counterbalanced across participants and concerned with an intergroup-related (i.e., the situation of the gay community in Italy) and a neutral (i.e., activities and attractions in the participants’ town) topic. Like in the previous Study 1, both conversations were recorded with a Microsoft Kinect v2 and the participants’ interpersonal volume was computed through the algorithm by Palazzi et al. (Citation2016). The repeated measures of volume during both interactions were then collapsed over time windows of 50 seconds, resulting in four repeated measures for each participant and conversation.

Crucially, after each conversation, participants completed another Stroop color-naming task. Hence, the Stroop color-naming task was administered three times, one before the interactions occurred (i.e., as a baseline measure) and one after each interaction.

At the end of the experimental session, participants were asked to complete the attentional check item, to give information about their sex, age, and sexual orientation, and were finally thanked and fully debriefed.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Consistent with Study 1, overall participants displayed low levels of explicit sexual prejudice (M = 1.79; SD = 1.14), but male respondents had higher explicit prejudice (M = 2.09; SD = 1.33) than female ones (M = 1.52; SD = 0.86), t(70) = 2.17, p = .033, Cohen’s d = 0.51. The mean IAT d-score was positive and greater than zero (M = 0.41; SD = 0.35), revealing the occurrence of implicit bias toward gay men among participants, t(71) = 9.90, p <. 001, Cohen’s d = 1.17), with similar levels across male and female participants, t(70) = 0.47, p = .640, Cohen’s d = 0.11.

Furthermore, an independent sample t-test was run on the Stroop latencies for the incongruent trials measured at the baseline, showing that the latencies did not differ between the crucial experimental condition (confederate’s sexual orientation: 1 = gay; 2 = straight) before the interactions occurred: t(69) = −0.30, p = .76, Cohen’s d = −0.07.

Main Analyses

We first checked the data for outliers and normality. Similar to the previous study, we did not detect any value deviating more than 2 SD from the mean. Furthermore, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the Stroop latencies for incongruent trials were normally distributed, Z = 0.03, p = .645.

Our main assumption (H2) was then verified through a LMM in which the participants’ Stroop latencies for the incompatible trials measured after the interactions (for a similar procedure, see Amato et al., Citation2006) were entered as the main outcome variable. The study accomplice’s sexual orientation (1 = gay vs. 2 = straight) and the topic of the conversation (1 = neutral vs. 2 = intergroup-related) were entered as fixed effects, whilst the participants’ levels of implicit bias and their averaged interpersonal volume during the interactions were considered as moderators. To take into account the repeated-measure nature of the design, we considered the intercepts across participants as the random coefficients of the model. Finally, participants’ sex was entered as a covariate, together with the Stroop task administration time (1 = first administration; 2 = second administration) to check for possible effects of familiarization with the task.

Overall, the model displayed an R2 marginal = 0.06 and an R2 conditional = 0.91. As reported in , no main effects of the considered antecedent variables emerged as significant, whereas the two-way interactions (study accomplice’s sexual orientation × conversation topic) significantly affected participants’ performances on the Stroop task: those who interacted with the gay study accomplice discussing the intergroup topic were then slower in answering the incompatible trials of the Stroop task than those who discussed with him the neutral topic, b = 16, SE = 5.62, 95%CI [5.18, 27.25], t(493) = 2.89, p = .004, whereas participants in the straight study accomplice condition were slower when discussing the neutral than the intergroup-related topic, b = −12.3, SE = 5.18, 95%CI [−22.53, −2.16], t(494) = −2.38, p = .018.

Table 2. Main and interactive effects of study accomplices’ sexual orientation, conversation topic, implicit bias and interpersonal volume on participants’ Stroop performance. Study 2.

Most importantly, the three-way interaction (study accomplice’s sexual orientation × implicit bias × interpersonal volume) interaction emerged as significant. Notably, the simple slope analyses that we conducted to interpret this interaction provided important support for our assumptions: in the gay study accomplice condition (see , graph on the right), for participants with higher levels of implicit sexual bias (+1SD) the smaller the volume that they maintained with the interactant the worse their performance on the Stroop task after the conversations, b = −437.3, SE = 162, 95%CI [−754.9, −119.7], t(553) = −2.71, p = .007. Put differently, among participants with high implicit bias, their cognitive depletion after the conversations was dependent on the interpersonal volume that they held during the conversations: the smaller it was, the greater their subsequent cognitive depletion that they had. Instead, in the same gay study accomplice condition, participants with lower levels of implicit bias (−1SD) did not differ on performances on the Stroop task depending on the volume maintained during the conversations, b = −65.5, SE = 228, 95%CI [−513.6, 328.7], t(550) = −0.29, p = .774

Figure 3. Interactive effects of implicit bias and interpersonal volume on Stroop latencies in milliseconds for the Gay condition (graph on the left) and the Straight condition (graph on the right). (Study 2).

In the straight study accomplice condition, both high and low implicitly biased participants showed similar levels of cognitive depletion, regardless of the volume that they kept with the interactant during the conversations, bs < 390, ts < 1.77, p > .077.

Furthermore, data analyses revealed a significant three-way interaction conversation topic × implicit bias × interpersonal volume. However, the inspection of this interaction (, right panel) revealed that neither implicit bias (± 1 SD) nor the participants’ volume (± 1 SD) significantly affected the participants’ Stroop performance, depending on the topic of the conversation (bs < |306.88|, ts < |1.66|, p > .098 for implicit bias, bs < 52.23, ts < 1.00, p > .323 for interpersonal volume). Finally, the four-way (study accomplice’s sexual orientation × implicit bias × interpersonal volume × topic of the conversation) was not significant, thus suggesting that the topic of the conversation did not interplay with participants’ implicit bias and their proxemics in affecting their cognitive resources.

Discussion

The main findings of this study revealed that for high (vs. low) implicitly biased participants, maintaining a smaller volume with the gay (vs. straight) study accomplice was cognitively demanding and led to worse performance on the subsequent Stroop task, in terms of longer latencies for incongruent trials. Thus, this result confirms our H2, by suggesting that proxemics, at least if considering the interpersonal volume, is a nonverbal behavior that highly implicitly biased people seem to control while interacting with gay men, by using cognitive resources that then result in cognitive depletion. Notably, unlike our hypotheses, these effects emerged regardless of the topic of the conversation, which did not interact with implicit bias in affecting participants’ behavior and related cognitive resources. Instead, the topic of the conversation moderated the experimental condition, so that, regardless of their levels of implicit sexual bias, participants were then more cognitively depleted when discussing with the gay (vs. straight) study accomplice the intergroup-related (vs. neutral) topic.

General Discussion

Overall, our studies documented an intriguing pattern of findings, which only partially confirmed previous research on intergroup nonverbal behavior. Coherent with literature (e.g., Crosby et al., Citation1980; Goff et al., Citation2008; Novelli et al., Citation2010; Palazzi et al., Citation2016) and initial hypotheses (H1a), mixed-model analyses revealed that implicit bias – but not explicit prejudice – is a relevant individual factor shaping people’s proxemic behaviors. That is, results of Study 1 reported that implicit attitudes deeply affect how straight people organize the physical space around them when interacting with a gay partner, especially when the discussion centers around sensitive intergroup topics. However, such an effect pointed in the opposite direction than what we expected: when the study accomplice’s gay (vs. straight) sexual orientation was made salient and the conversation was about the situation of the gay community, participants with higher levels of implicit bias displayed a smaller volume index than those with lower levels. This main result is opposite to previous research, which at least within interethnic relations, has revealed that proxemic behaviors conveying greater psychological distance (e.g., a larger interpersonal distance) are particularly enacted by high rather than low biased people. However, we reasoned that the proxemic behavior displayed by highly implicitly biased participants of our studies would not necessarily reflect a genuine and spontaneous willingness of psychological intimacy with the outgroup partner, but rather a tendency to apparently express behavior that is contrary to their implicit beliefs. Put differently, we reasoned that proxemic behaviors such as interpersonal volume or interpersonal distance are nonverbal cues that people may somewhat intentionally control. Consequently, especially highly implicitly biased people that discussed with a sexual minority partner a sensitive topic may be intentionally inclined to stay closer to him to manifest nonverbal immediacy and, thus, appear non-prejudiced in the gay study accomplice’s eyes. Findings for Study 2 were in line with this reasoning: highly implicitly biased participants that maintained a smaller space volume during the conversation with the gay (vs. straight) study accomplice then performed worse on a Stroop task. Instead, lowly implicitly biased participants and participants who interacted with the straight study accomplice displayed similar performance on the Stroop task, regardless of the interpersonal volume that they maintained with the study accomplice. Thus, especially for highly biased participants, the tendency to have a smaller volume during the mixed interaction was then translated into a worse performance on a cognitive task, which reflects greater use of cognitive resources (i.e., the color-naming Stroop task).

Taken together, we believe that our findings could importantly contribute to the scarce literature on intergroup nonverbal behaviors featuring gay and straight people’s dyadic interactions, by stressing the important role of implicit sexual prejudice in shaping proxemic behaviors. Shedding light on the nature of the relationship between sexual prejudice and intergroup nonverbal behavior appears particularly relevant for different reasons. From a theoretical perspective, sexual prejudice differs from other types of prejudice, especially from the interethnic one, which has been largely investigated within intergroup nonverbal behaviors literature. First, unlike most other types of stigma, the defining features of homosexual group membership are not visible (Cox & Devine, Citation2014; Cox et al., Citation2016) during face-to-face interactions. Second, it is noteworthy that the type of stigma attached to a specific group also affects intergroup interactions, as some biases are inhibited more strongly by social norms and others are more tolerated (Dovidio et al., Citation2006; Hebl & Dovidio, Citation2005). With this regard, although sexual prejudice has been historically more easily accepted and expressed compared to other types of prejudice (Herek & McLemore, Citation2013), recent trends are suggesting that this bias is rapidly changing, and mainly decreasing both in its explicit and implicit forms (Charlesworth & Banaji, Citation2019). These characteristics and changes may also explain the unexpected direction of our main findings, although our studies do not allow us yet to exactly define if (and which) characteristics underlying the implicit attitudes toward gay people may explain such effects.

Further, our results shed important new light on proxemic behaviors underlying dyadic intergroup interactions, by highlighting how the link between proxemic behaviors and psychological immediacy may be somewhat more complex than what scholars have found so far. More specifically, through our studies, we revealed that, at least within straight and gay men interactions, the proxemic feature of space volume is an intergroup nonverbal behavior that highly biased people can intentionally control to possibly display a positive self-image in the interactant’s eyes. However, such willingness to control has its costs for an individual, by leading to greater cognitive resource depletion. This latter finding is also in line with previous literature on ethnic prejudice that documented how White participants, especially if implicitly biased, are often cognitively depleted after interethnic interactions and have worse performances on cognitive tasks (e.g., Richeson & Shelton, Citation2003; Richeson & Trawalter, Citation2005; Richeson et al., Citation2005). This finding may also be interpreted considering Plant and Devine’s (Citation1998) distinction between the internal vs. external motivations to respond without prejudice. Speculatively, it is possible that external motivations to appear non-prejudiced in the minority partner’s eyes lead highly implicitly biased people to assume nonverbal behaviors conveying signals of closeness, such as maintaining a smaller interpersonal volume. In turn, these controlled behaviors caused a backlash in terms of cognitive depletion. This latter speculation would be better investigated in future studies, which should for instance, verify the sequential link between people’s external (vs. internal) motivation to respond without prejudice, their proxemic behaviors during the interaction in terms of interpersonal volume, and their consequent cognitive depletion.

Finally, our research could represent a significant methodological advance for research on nonverbal behaviors within intergroup settings. In fact, for the first time, we analyzed intergroup nonverbal behaviors through the lenses of IR depth cameras. To date, most of the research (e.g., Burba et al., Citation2012; Frauendorfer et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2014) that used these new technologies did not consider intergroup interactions and, thus, did not explore the role of individual or situational variables linked with the group membership. More widespread use of these new technologies within research on intergroup relations could help scholars in obtaining more reliable indexes of nonverbal behaviors and, thus, a more reliable and exhaustive picture of nonverbal dynamics underlying mixed dyadic interactions.

Despite the relevance of the present findings, we note some limitations that could guide future research. The first limitation is related to the sample sizes of our studies. Although they were sufficient to detect medium effect sizes, some significant effects could not emerge as our samples were underpowered to detect them. Thus, future researchers are encouraged to replicate our pattern of findings by considering larger sample sizes. However, it is noteworthy that our studies relied on articulated laboratory procedures and instruments, the reason reaching large sample sizes is often difficult and undoubtedly more difficult than when conducting for example, online surveys. Second, in both studies, we assessed the participants’ explicit prejudice through the ATLG scale. Although it is the most used and validated tool to explicitly measure sexual prejudice, a more confident conclusion about the null effect of this form of prejudice on intergroup proxemic behaviors could be drawn by also considering different self-report measures, such as the Modern Homonegativity Scale (Morrison & Morrison, Citation2002). Third, in our research, we did not assess the perceived quality of the interaction. As nonverbal behaviors can deeply shape such perceptions, understanding how (and if) the pattern of behaviors that we studied is associated with these perceptions could be particularly informative to better interpret our results. For example, it is plausible that the small volume that our highly implicitly biased participants maintained during the interaction could be perceived as a physical threat by our study accomplices, with a consequently decreased perceived quality of the interaction. Fourth, our studies considered undergraduates as participants. It would be interesting to investigate whether our pattern of findings would also emerge with older community samples, assuming that they would have fewer experiences of interaction with gay people and higher levels of prejudice toward them than young people. Finally, for practical reasons, we chose to assess implicit and explicit prejudice right before the interaction. Although a similar procedure has been employed in previous studies and we included filler items to cover our manipulation, it may have triggered participants’ social desirability and somewhat affected their behaviors during the recorded interactions. Future studies might replicate our findings by, for instance, assessing people’s implicit and explicit beliefs toward the outgroup target at a different time than the experimental interactions with the study accomplice.

Conclusions

Nonverbal behaviors are a prominent feature of intergroup communication, including that which characterizes straight and gay people. Thus, understanding the nature of these behaviors and their antecedents is highly relevant, with the ultimate goal to ameliorate the quality of these interactions and, consequently, the attitudes between sexual majority and minority members. We believe that the findings of our research and the instruments that we employed could importantly help to reach this goal and encourage future research in deepening this field of research.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted after receiving ethical approval from the local Ethics Committee. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the AIP and APA ethical guidelines and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Full informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marcello Gallucci for his helpful guidance in statistical analyses. We also would like to acknowledge confederates and participants of our studies for their precious participation in our research

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are not competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available through the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/e8tza/?view_only=64c3a20c32c74a9cb52dd3701543212c).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2192696

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 GAMLj package in Jamovi commonly uses simple contrast coding that compares the reference group to each of the other groups, rather than effect or dummy coding. However, it centers the contrast to 0 (i.e., the average of the sample), so that the other variables’ effects are computed on average.

2 Although there is no full agreement among scholars about which effect sizes to report in LMMs (Lorah, Citation2018), the most common effect size reported is the explained variance. Accordingly, R-squared Marginal and R-squared Conditional are reported for each model as an estimation of the effect sizes.

3 We opted for conducting two separate LMMs to not make them too complex in terms of interactions between the crucial variables. However, a similar pattern of findings also emerged when considering a single LMM: the study accomplice’s sexual orientation × conversation topic × implicit prejudice interaction emerged as significant, F(1,528.0) = 5.76, p = .02, whereas neither the study accomplice’s sexual orientation × conversation topic × explicit prejudice, F(1,528.0) = 0.14, p = .708, nor the four-way study accomplice’s sexual orientation × conversation topic × implicit bias × explicit prejudice, F(1,528.0) = 1.23, p = 0.268, had a significant effect.

4 For brevity and because explicit sexual prejudice was not the focus of Study 2, we did not report the mixed model including this variable in the main text. However, the main findings of this model are available in the Supplementary Material.

5 Following the procedure of Amato et al. (Citation2006), in calculating the Stroop index we decided to only consider latencies associated with the incompatible trials because the most common method to compute it (i.e., comparing the latencies associated with compatible and incompatible trials), resulted in a non-normal data distribution and displayed a high amount of negative values. However, following Trawalter and Richeson’s (Citation2006) procedure, we also computed an index by subtracting latencies associated with control trials from latencies associated with incompatible trials and obtained a normal distribution that still shows negative scores. Overall, the pattern of findings obtained by using this index is similar to those reported in the main Results section (for a more detailed description of these alternative analyses, see the Supplementary Material).

References

- Amato, M. P., Portaccio, E., Goretti, B., Zipoli, V., Ricchiuti, L., De Caro, M. F., Patti, F., Vecchio, R., Sorbi, S., & Trojano, M. (2006). The Rao’s brief repeatable battery and stroop test: Normative values with age, education and gender corrections in an Italian population. Multiple Sclerosis, 12(6), 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458506070933

- Anselmi, P., Vianello, M., Voci, A., & Robusto, E. (2013). Implicit sexual attitude of heterosexual, gay and bisexual individuals: Disentangling the contribution of specific associations to the overall measure. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e78990. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078990

- Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59(4), 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

- Baur, T., Damian, I., Lingenfelser, F., Wagner, J., & Elisabeth, A. (2013). NovA: Automated analysis of nonverbal signals in social interactions. HBU, Conference Proceedings, Human Behavior Understanding: 4th International Workshop (pp. 160–171), Barcelona, Spain. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02714-2_14

- Bull, P. (2002). Communication under the microscope: The theory and practice of microanalysis. Guilford Press.

- Burba, N., Bolas, M., Krum, D. M., & Suma, E. A. (2012). Unobtrusive measurement of subtle nonverbal behaviors with the Microsoft Kinect. In Virtual Reality Short Papers and Posters (VRW), IEEE (pp. 1–4).

- Charlesworth, T. E., & Banaji, M. R. (2019). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. Long-term change and stability from 2007 to 2016. Psychological Science, 30(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618813087

- Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1997). Nonconscious behavioral processes: The self-fulfilling consequences of automatic stereotype activation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33(5), 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1997.1329

- Chen, L., Leong, C. W., Feng, G., Lee, C. M., & Somasundaran, S. (2015). Utilizing multimodal cues to automatically evaluate public speaking performance. 2015 International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction, ACII 2015 (pp. 394–400). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACII.2015.7344601

- Cox, W. T. L., & Devine, P. G. (2014). Stereotyping to infer group membership creates plausible deniability for prejudice-based aggression. Psychological Science, 25(2), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613501171

- Cox, W. T., Devine, P. G., Bischmann, A. A., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Inferences about sexual orientation: The roles of stereotypes, faces, and the gaydar myth. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1015714

- Cozzolino, M. (2003). La comunicazione invisibile. Gli aspetti non verbali della comunicazione [Invisible communication. Non-verbal aspects of communication]. Edizioni Carlo Amore.

- Crosby, F., Bromley, S., & Saxe, L. (1980). Recent unobtrusive studies of Black and White discrimination and prejudice: A literature review. Psychological Bulletin, 87(3), 546–563. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.87.3.546

- Cuenot, R. G., & Fugita, S. S. (1982). Perceived homosexuality: Measuring heterosexual attitudinal and nonverbal reactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 8(1), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616728281016

- Dasgupta, N., & Rivera, L. M. (2006). From automatic antigay prejudice to behaviour: The moderating role of conscious belief about gender and behavioral control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(2), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.268

- Dovidio, J. F., Hebl, M., Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2006). Nonverbal communications, race, and intergroup interaction. In V. Manusov & M. L. Patterson (Eds.), The Sage handbook of nonverbal communication (pp. 481–500). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976152.n25

- Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., & Gaertner, S. L. (2002). Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.62

- Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., Johnson, C., Johnson, B., & Howard, A. (1997). On the nature of prejudice: Automatic and controlled processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33(5), 510–540. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1997.1331

- Fasoli, F., Paladino, M. P., Carnaghi, A., Jetten, J., Bastian, B., & Bain, P. G. (2016). Not “just words”: Exposure to homophobic epithets leads to dehumanizing and physical distancing from gay men. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(2), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2148

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Frauendorfer, D., Schmid Mast, M., Nguyen, L., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2014). Nonverbal social sensing in action: Unobtrusive recording and extracting of nonverbal behaviour in social interactions illustrated with a research sample. Journal of Nonverbal Behaviour, 38(1), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-014-0173-5

- Gallucci, M. (2019). GAMLj: General analyses for linear models. [jamovi module]. https://gamlj.github.io/

- Gatica-Perez, D., Lathoud, G., Odobez, J. M., & McCowan, I. (2007). Audiovisual probabilistic tracking of multiple speakers in meetings. IEEE Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 15(2), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2006.881678

- Goff, P. A., Steele, C. M., & Davies, P. G. (2008). The space between us: Stereotype threat and distance in interracial contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.91

- Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

- Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

- Hebl, M. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2005). Promoting the “social” in the examination of social stigmas. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(2), 156–182. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_4

- Hebl, M. R., Foster, J. B., Mannix, L. M., & Dovidio, J. F. (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: A field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 815–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202289010

- Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25(4), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551476

- Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., & Gillis, J. R. (2002). Victim experiences in hate crimes based on sexual orientation. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00263

- Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826

- Hunt, C. J., Fasoli, F., Carnaghi, A., & Cadinu, M. (2016). Masculine self-presentation and distancing from femininity in gay men: An experimental examination of the role of masculinity threat. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039545

- Imhoff, R., & Recker, J. (2012). Differentiating islamophobia: Introducing a new scale to measure Islamoprejudice and secular Islam critique. Political Psychology, 33(6), 811–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00911.x

- Kiebel, E., Bosson, J. K., & Caswell, A. T. (2020). Essentialist beliefs and sexual prejudice toward feminine gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(8), 1097–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1603492

- Knöfler, T., & Imhof, M. (2007). Does sexual orientation have an impact on nonverbal behavior in interpersonal communication? Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 31(3), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-007-0032-8

- La Varvera, F. (2013). La comunicazione non verbale [Non-verbal communication]. Sovera Edizioni.

- Lee, J. J., Knox, B., & Breazeal, C. (2013, March). Modeling the dynamics of nonverbal behavior on interpersonal trust for human-robot interactions. 2013 AAAI Spring Symposium Series, Palo Alto, Ca, USA.

- Lick, D. J., & Johnson, K. L. (2014). Perceptual underpinnings of antigay prejudice: Negative evaluations of sexual minority women arise on the basis of gendered facial features. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(9), 1178–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214538288

- Lick, D. J., Johnson, K. L., & Gill, S. V. (2014). Why do they have to flaunt it? Perceptions of communicative intent predict antigay prejudice based upon brief exposure to nonverbal cues. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 5(8), 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614537311

- Lorah, J. (2018). Effect size measures for multilevel models: Definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-018-0061-2

- MacLeod, C. (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 163–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.163

- McConnell, A. R., & Leibold, J. M. (2001). Relations among the implicit association test, discriminatory behavior, and explicit measures of racial attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1470

- Morrison, M. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2002). Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(2), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/j082v43n02_02

- Nosek, B. A., & Smyth, F. L. (2007). A multitrait-multimethod validation of the implicit association test: Implicit and explicit attitudes are related but distinct constructs. Experimental Psychology, 54(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169.54.1.14

- Novelli, D., Drury, J., & Reicher, S. D. (2010). Come together: Two studies concerning the impact of group relations on ‘personal space.’ British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466609X449377

- Palazzi, A., Calderara, S., Bicocchi, N., Vezzali, L., Di Bernardo, G. A., Zambonelli, F., & Cucchiara, R. (2016, September). Spotting prejudice with nonverbal behaviours. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing (pp. 853–862). https://doi.org/10.1145/2971648.2971703

- Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 811–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811

- Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does not pay: Effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychological Science, 14(3), 287–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.03437

- Richeson, J. A., & Trawalter, S. (2005). Why do interracial interactions impair executive function? A resource depletion account. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 934–947. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.934

- Richeson, J. A., Trawalter, S., & Shelton, J. N. (2005). African American’s implicit racial attitudes and the depletion of executive function after interracial interactions. Social Cognition, 23(4), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2005.23.4.336

- Shelton, J. N., Dovidio, J. F., Hebl, M., & Richeson, J. A. (2009). Prejudice and intergroup interaction. In S. Demoulin, J.-P. Leyens, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), Intergroup misunderstandings: Impact of divergent social realities (pp. 21–38). Psychology Press.

- Siegman, A. W., & Feldstein, S. (Eds.). (2014). Nonverbal behavior and communication. Psychology Press.

- Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., Hilpert, P., Cantarero, K., Frackowiak, T., Ahmadi, K., Alghraibeh, A. M., Aryeetey, R., Bertoni, A., Bettache, K., Blumen, S., Błażejewska, M., Bortolini, T., Butovskaya, M., Castro, F. N., Cetinkaya, H., Cunha, D., David, D., David, O. A., & Pierce, J. D. (2017). Preferred interpersonal distances: A global comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117698039

- Steffens, M. C. (2005). Implicit and explicit attitudes towards lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 49(2), 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v49n02_03

- Trawalter, S., & Richeson, J. A. (2006). Regulatory focus and executive function after interracial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(3), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.05.008

- Trawalter, S., Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2009). Predicting behavior during interracial interactions: A stress and coping approach. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(4), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309345850

- Wagner, U., Christ, O., Pettigrew, T. F., Stellmacher, J., & Wolf, C. (2006). Prejudice and minority proportion: Contact instead of threat effects. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(4), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900406

- Zhang, Y., Huo, G., Wu, J., Yang, J., & Pang, C. (2014). An interactive oral training platform based on Kinect for EFL learning. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 704, 419–423. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.704.419