ABSTRACT

Pup play is a kink or BDSM activity and subculture that provides opportunities for social and sexual play and exploration. While growing scholarly attention has focused on the diverse dynamics of pup play cultures, and reasons for participation within them, no research has considered how pup play may be attractive for neurodivergent people. This study sample consisted of 413 pup play practitioners from an international internet survey to examine the occurrence of autistic traits and explore characteristics and social connections of people with autistic traits who engage in pup play. Autistic traits were assessed using the Autism-Spectrum Quotient-Short Form (AQ-S), with 1 in 2 participants reporting a score that is indicative of an autism diagnosis, substantially higher than the prevalence of autism in the general population (1 in 44). Using linear and multinomial regression analyses, we found that people with high autistic traits preferred non-flexible roles in pup play, had lower identity resilience, and more restricted sociosexuality. People with high autistic traits were also less likely to belong to pup play social communities or to closer-knit family/pack units despite wishing to and were also less likely to have a strong identification with pup play communities than people with low AQ-S scores. While these findings need to be treated as preliminary based on methodological and sample limitations, this research demonstrates the importance of considering intersections between autistic traits and sexual subcultures and provides evidence that sexuality research would be enhanced by a more inclusive approach to considering neurodivergence more broadly.

Introduction

Kink is an umbrella term for the spectrum of sexual or erotic activities outside of normative versions of sex, undertaken for sensory, emotional, or psychological pleasure. Like BDSM, it can include the exchange of power (or perception of this) and the inflicting or receiving of pain, but it incorporates a broader set of activities and interests than BDSM, such as the wearing of gear or the fetishization of body parts/objects. Kink is consensual, with a shared understanding that the activities are kinky (Wignall, Citation2022, p. 39). A systematic scoping review found 20% of people reported engaging in kink and 40–70% of people reported having kink related fantasies (Brown et al., Citation2020). In a Finnish sample, non-heterosexuals displayed almost twice as much interest in kink compared to heterosexuals (Paarnio et al., Citation2022).

One kink interest that has grown in popularity over the last decade, predominantly within gay male subcultures, is pup play. Pup play is a form of role play in which people imitate a dog or puppy, engaging in associated behaviors including walking on all fours (hands and knees), barking, playing with “dog” toys and other “pups,” and often wearing pup play paraphernalia, including a pup hood, pup tail, and collar/leash (Wignall & McCormack, Citation2017). While individuals can engage in pup play alone, it is mostly performed with other pups or “handlers” (a term for a dominant who looks after the pups; Daniels, Citation2005; Wignall et al., Citation2022).

Various rationales have been described for engaging in pup play, with two overarching motivations: sexual and social motivations (see St Clair, Citation2015; Wignall, Citation2022). Highlighting the former, some people engage in pup play for sexual or erotic pleasure, often incorporating elements of BDSM or other sexual activities alongside pup play such as wearing rubber/leather or explicitly enacting power dynamics (Wignall, Citation2022), as well as obtaining sexual or erotic pleasure from wearing pup play-related gear (Wignall & McCormack, Citation2017). Pup play also allows for individual expression and social connection, with individuals creating a unique “pup identity” and interacting with other pups/handlers and the broader kink subculture, forming social networks online and offline (Matchett & Berkowitz, Citation2023). Individuals can engage in pup play as a form of therapy, relaxation, or escapism from routine life (Lawson & Langdridge, Citation2019). The social connection and sense of community possible through pup play seems especially attractive to individuals who struggle with their mental health (Wignall et al., Citation2022). Like other kink activities (Cascalheira et al., Citation2021), pup play may also allow individuals to reframe traumatic experiences, build self-worth, and reclaim feelings of empowerment. Other vulnerable or marginalized groups, such as neurodivergent people, may be especially drawn to the activity because of the social support aspect that is a valued and visible part of pup play communities.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference encompassing different ways of thinking, feeling, experiencing, and moving through the world (Lilley et al., Citation2022; MacLennan et al., Citation2022). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimated that 1 in 44 American children are autistic; more conservative estimations place this at 1 in every hundred people (Zeidan et al., Citation2022). Autism has been historically defined in relation to social “deficits” and “disinterest” (Jaswal & Akhtar, Citation2019), yet this has been challenged by neurodivergent approaches that adopt the social model of disability (see Pellicano et al., Citation2022; Woods, Citation2017). The social model of disability contends that people with impairments are disabled by dominant social attitudes and the social organization of society rather than any medical condition.

Recent work shows that autistic people have their own distinct social and communicative style (Crompton et al., Citation2020; Howard & Sedgewick, Citation2021): for instance, tending toward a direct and honest style of speech, preferring deeper, more intimate conversation than socially expected small-talk, and finding eye contact painful, aversive or inconducive to communicating with and/or paying attention to others. The discord in communication which occurs between neurotypical and neurodivergent people can make relationships challenging (Davis & Crompton, Citation2021), and many autistic people learn to camouflage or hide their differences as a response to the stigma and social exclusion surrounding autism (Bradley et al., Citation2021; Han et al., Citation2022). Mental ill-health is extremely common in autistic people (Lai et al., Citation2019), in whom suicide rates are markedly elevated (Hedley et al., Citation2022; Moseley et al., Citation2022).

Relationships and sexuality in autistic adults are an under-researched topic, despite the importance of social connection and intimacy for wellbeing (Crompton et al., Citation2020). Through comparison with neurotypical peers, autistic relationships and expressions of sexuality have often been stigmatized (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist & Jackson-Perry, Citation2021), despite many autistic people expressing similar desires for intimacy, closeness and sharing and similar means of achieving the same within relationships (Joyal et al., Citation2021; Sala et al., Citation2020), albeit with important adaptations for sensory and communication differences (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Moseley et al., Citation2022). They do, however, also express a lack of confidence around the expectations, behavior, and communication needs of partners (and potential partners) and their own abilities to interpret and fulfil the same (Hancock et al., Citation2020; Sala et al., Citation2020). These and other barriers, such as their smaller social networks and reduced access to sex education, mean autistic people are less likely to experience and maintain satisfactory relationships (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Yew et al., Citation2021), and are more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse (Griffiths et al., Citation2019; Pearson et al., Citation2022; Stewart et al., Citation2022).

These difficulties may also be amplified by being LGBT or having a minoritized gender and/or sexual identity, as is more common in autistic people (McQuaid et al., Citation2022; Warrier et al., Citation2020). Lack of opportunity for romantic or sexual experiences can be a barrier to realization of an LGBT or queer identity, as can difficulties identifying one’s own emotions and bodily sensations, and lack of mainstream LGBT representations; however, LGBT autistic individuals can also face internalized stigma around one or more of their minoritized identities, or invalidation from people who conflate their autism and their gender or sexual identities (Hillier et al., Citation2020; McAuliffe et al., Citation2023). These studies suggest that while some autistic people receive understanding and acceptance from LGBT communities, others feel ostracized by their autism, particularly in the “gay scene” (Hogan & Micucci, Citation2020).

The prevalence and inclusion of autistic people in kink communities, which overlap substantially with LGBT communities, is presently unknown. Several aspects of kink may appeal to the cognitive and social profile of autistic people, including the clear and explicit communication of boundaries and preferences which may be absent from other sexual encounters, exploration of sensory experiences, and acceptance and celebration of living outside of normative expectations (Pliskin, Citation2022); with some studies supporting this (Pearson & Hodgetts, Citation2023; Schöttle et al., Citation2022; Seers & Hogg, Citation2021).

Pup play and the pup community may appeal to autistic individuals in similar ways, given the opportunity for relaxed and tactile play, and sexual and social interaction within predictable, explicit guidelines (Wignall, Citation2022). Certain activities and approaches may be attractive to autistic processing styles: for instance, since the role of a handler demands high sensitivity to the non-verbal behaviors made by an individual whose gear might obscure their facial expressions, it is possible that autistic individuals might feel more comfortable as pups. Similarly, while some individuals adopt pup and handler roles in a flexible manner, autistic individuals might find it easier to build and inhabit a single role, which could be an important aspect of their self-identity in a world where autism is stigmatized. Early pup play cultures had a strong online presence (Wignall, Citation2017), which might also have been attractive for autistic people who could participate without the pressure of initial in-person interaction. Social motivations for pup play might be very important for these often-marginalized individuals, though the extent to which social motivations are fulfilled might fall short, as reported in relation to LGBT communities.

Aims of Present Study

Using an international dataset of pup play practitioners, we explored the possible prevalence of autism through a commonly used autism screening tool: the Autism-Spectrum Quotient-Short Form [AQ-S] (Hoekstra et al., Citation2011). We secondly explored differences between pup play practitioners as a function of autistic traits. While exploring roles as pups or handlers, we hypothesized that individuals high in autistic traits might be more inclined toward identifying as pups compared to handlers. In that kink activities can be self-restorative and empowering for the survivors of abuse and trauma (Cascalheira et al., Citation2021), we queried whether individuals high in autistic traits, given their vulnerability to exploitation and abuse (Griffiths et al., Citation2019; Stewart et al., Citation2022), might identify strongly with their pup play identities and with the pup community as an integral element of their self-identity. While exploring social and sexual motivations for pup play and the extent to which individuals were socially connected with others in this community, we predicted that social motivations for pup play might be particularly important for individuals higher in autistic traits, although they might not have achieved social inclusion within this community. Since pup play practitioners are a scarcely researched demographic, we also explored whether individuals high in autistic traits differed more generally in relation to their sexual identities and attitudes.

Method

Participants

Six hundred and forty-seven participants were recruited as part of a larger mixed methods study. Data for 234 participants who did not complete the AQ-S were removed prior to analysis. The final sample consisted of 413 participants (average age 31.1 years [SD: 9.7, range: 18–79]). Participants were asked to provide information about gender, sexuality, and ethnicity in open text boxes, and these were then grouped into categories. Genders and sexual orientations are displayed in . Other than those who stated their gender as “trans man” or “trans woman,” an additional 59 participants identified as trans or as having a trans history (25 males, 1 female, 28 people who were non-binary, gender-fluid or genderqueer, and 5 people who were agender). Geographic location and ethnicity are displayed in . Of note, where ethnicities are not provided, this is because of low numbers of responses (e.g., African American was provided by just one participant so was coded as Bi-Racial/Multi-Racial).

Table 1. Gender and sexuality information of participants (n = 413).

Table 2. Geographic location and ethnicity of participants (n = 413).

Procedure and Materials

Ethical approval for the study was granted from Bournemouth University. Data were collected from March 2022 to May 2022. An online survey was advertised through various fora: as An International Study on Pup Play through a leading kink website (Recon.com), on the lead researcher’s social media accounts, and through snowball sampling using the lead researcher’s contacts within international pup play communities. The recruitment materials did not mention autism, nor were autistic spaces or networks targeted as part of the recruitment process.

Inclusion criteria specified participants must be aged 18 years or older and engage in pup play (as a pup, handler, or both). Interested individuals were able to click a link to Qualtrics, a survey hosting platform, and were presented with an information sheet and required to confirm consent to access the survey. The survey took approximately 30–40 minutes to complete; on completion, participants could separately submit their e-mail address into a prize draw for a $150 voucher for a leading online kink store.

The survey began with some demographic questions (including age, gender, sexuality, and whether participants had any diagnosed or suspected mental health conditions), followed by questions about participants’ engagement with pup play (including their role and their motivations for engaging in pup play). Participants then completed several psychometric scales. The demographic questions, pup-related questions, and psychometric scales relevant to this paper, as per their roles in analyses, were:

Independent Variable: Autism-Spectrum Quotient Short-Form (AQ-S) Total Scores

Autistic traits, quantifiable features considered analogous to the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, occur dimensionally within the general population and may reflect varying genetic liability for autism (Abu-Akel et al., Citation2019). The AQ-S (Hoekstra et al., Citation2011) is not a diagnostic test but a screening measure to indicate where full diagnostic assessment may be appropriate. It includes 28 items which map to subscales reflecting autistic-like social behavior, preference for routine, difficulty with attentional switching, social imagination, and fascination with numbers/patterns, which converge on one higher-order factor reflecting autistic traits (total score). Responses to items range from “Strongly agree” (1), “Slightly agree” (2), “Slightly disagree” (3), and “Strongly disagree” (4), with higher scores indicative of more numerous autistic traits.Footnote1 The original study found that a >65 cutoff (total score) could differentiate autistic from non-autistic participants with good sensitivity (.97) and specificity (.82), though a more stringent cutoff was offered at >70 (sensitivity .94, specificity .91). The present study utilized total AQ-S scores, which had good internal consistency (α = .85), as a continuous variable in all analyses.

Dependent Variables

Pup identity, motivations toward pup play, and engagement with the community

While participants completed quantitative and qualitative items concerning their activities, feelings and attitudes around pup play, the present analysis focused on several quantitative variables. These included:

Role during pup play

Asked whether they identified as pups or handlers, participants could respond “Pup” (280 participants [coded 1]), “Pup and Handler (Pup-focused)” (74 participants [coded 2]), “Pup and Handler equally” (13 participants [coded 3]), “Handler and Pup (Handler-focused)” (10 participants [coded 4]) “Handler” (35 participants [coded 5]).

Strength of identification with pup community

A modified version of the Four Item measure of Social Identification (FISI; see Postmes et al., Citation2013) was used to measure participants’ identification with a pup community, and the extent to which their pup identity was an important element of their self-identity. Participants were asked to rate four statements on different components on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (“I identify with the pup community”; “I feel committed to the pup community”; “I am glad to be in the pup community”; “Being a pup/handler is an important part of how I see myself”). The measure had good reliability (α = .87).

Social and sexual motivations for pup play

To understand whether participants considered pup play more of a social or sexual activity (Wignall, Citation2022), participants were asked the following questions: “For you personally, how much is pup play more of a social activity, that’s about connecting with others playfully regardless of sex?”; “For you personally, how much is pup play more of a sexual activity, that’s being erotic and/or sexual with others?” and asked to indicate their answer on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 100 (completely).

Social group and pack membership

Participants were asked whether they belonged to any kind of social group that is part of a pup community (218 said yes [coded 1], 195 said no [coded 2]), and then whether they belonged to a pack or chosen family (105 said yes [coded 1], 141 said no [coded 2], and 167 said that they did not but would like to [coded 3]).

Broader Identity and Sexuality

In addition to the variables focusing on identity and social/sexual motivations during pup play, we examined broader aspects of participants’ sense of identity and sexuality. These included:

Identity Resilience

Identity resilience is conceptualized as a buffer in the face of life stress and challenges to one’s sense of identity and self-worth, being a state of “certainty of who one is and will remain despite individual and social changes that occur” (Breakwell et al., Citation2022). Having greater identity resilience is to have a more stable self-concept, one which facilitates adaptive coping (e.g., seeking of social support) during times of adversity and which can respond to circumstantial changes without serious damage to self-worth, self-efficacy, sense of uniqueness and self-continuity (Breakwell et al., Citation2022, p. 167). We adopted the psychometric test devised by these same authors, which includes 16 items on four subscales of self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-continuity, and self-distinctiveness which converge on a higher-order identity factor. The scale is scored on a 5-point scale (“Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”), with higher overall scores reflecting higher scores in each subscale and higher identity resilience as a whole. Unfortunately, one item from the Distinctiveness subscale failed to display to participants, such that they completed only 15 of the 16 items. The scale nevertheless showed high internal consistency for its total score (α = .85), which was used in the present analysis. The sample’s average score was 52.39 (SD: 9.02, range: 15–75), approximately equivalent to that reported by Jaspal and Breakwell (Citation2022) in another sample of gay men (whose average was 52.89).

Sociosexuality

Participants completed the nine-item Sociosexual Orientation Inventory – Revised (SOI-R; Penke & Asendorpf, Citation2008) scale, which we used as our measure of sociosexuality. The SOI-R includes three items, assessing previous behaviors (e.g., “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months?”), attitudes toward casual sex (e.g., “Sex without love is O.K.”), and sexual desires (e.g., “In everyday life, how often do you have spontaneous fantasies about having sex with someone you have just met?”). Participants rated each item using a nine-point Likert-type scale anchored numerically for previous behaviors, partially anchored from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 9 (“Strongly agree”) for nonmonogamy attitudes, and fully anchored from 1 (“never”) to 9 (“at least once a day”) for sexual desires. The scores for all nine items were aggregated, with higher scores indicative of a heightened global sociosexual orientation (possible range of scores: 9–81). Cronbach’s alpha for the total score showed good internal consistency in our sample (α = .84), whose average score was 53.45 (SD: 14.67, range: 11–81).

Data Analysis

Autistic traits were normally distributed within the sample (W [413] = .996, p = .370). Skewness and kurtosis between −2 and +2 indicated that our continuous dependent variables (the FISI, the IRI, the SOI-R, social and sexual motivations for pup play) were also normally distributed, and homogeneity of variance was likewise confirmed.

Two potential confounds (correlates) of autistic traits were age, where participants with higher autistic traits tended to be younger (r [411] = −.11, p = .028), and mental health conditions. Participants were asked whether they had any diagnosed mental health conditions (“yes” (coded 1), “I think I do, but I am not diagnosed” (also coded 1), or “no” (coded 2)); as is typically the case in autistic populations (Lai et al., Citation2019), participants with higher AQ-S scores tended to endorse diagnosed or suspected mental health condition(s) (r [413] = −.33, p < .001). As such, all subsequent regression analyses controlled for these two covariates in order to examine changes to dependent variables and/or group categorization as a function of AQ-S scores.

Dependent variables related to pup play included four nominal variables (role during pup play, whether participants belonged to a pack [and if not, whether they wanted to], and whether they were a member of any pup play communities) and three continuous variables (ranking of social and sexual motivations for pup play, and FISI scores reflecting strength of pup play identity). While these variables were treated as separate outcome variables and were not highly correlated with one another (VIF between 1.03–1.2), there were, notably, relationships between some of them: individuals who were not in a pack/family and expressed no desire to be so tended not to be involved in any pup play social communities (rs = .15, p = .002); those who were not part of social communities tended to endorse less social (r = −.18, p < .001) and more sexual (r = .14, p = .006) motivations for pup play; greater social motivation was associated with lower sexual motivation and vice versa (r = −.42, p < .001).

For the four nominal variables, three multinomial regressions (p-values corrected to .017) were used to examine whether individuals with higher AQ-S scores: were particularly likely to identify with pup play roles as solely pups, pup and handler (pup-focused), pup and handler equally, pup and handler (handler-focused), or solely handlers; were more or less likely to belong to a pack or wish to belong to a pack; and were more or less likely to belong to a pup play social community (“pup community”). Confidence intervals were set at 95%, and the reference category was always the first.

For the three continuous variables, three linear regressions (p-values corrected to .017) examined changes to social motivations for pup play, sexual motivations for pup play, and strength of identification with pup play communities (with FISI scores as a function of AQ-S scores). For each, age and the presence/absence of mental health conditions were entered in the first block of the model, with autistic traits in the second (VIF between 1.06–1.8 indicated no problematic multicollinearity).

Dependent variables pertaining to broader identity resilience and sociosexuality included continuous IRI and SOI-R scores. Both were analyzed using linear regression (p corrected to .025), modeled as above.

Results

Distribution of Autistic Traits among Participants

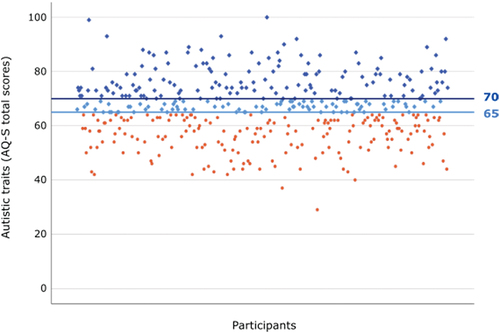

The complete sample had an average AQ-S score of 65.83 (SD: 9.02, range 29–100). The distribution of participant AQ-S scores is displayed in . Approximately 35.4% (146 out of 413) of the sample scored above the stringent cutoff of 70 or above; 55.7% (230) scored at or above the more lenient cutoff of 65.

Figure 1. The distribution of autistic traits among participants.

Characteristics of Pup Play as a Function of Autistic Traits

Multinomial Regression

Together, autistic traits, the dichotomous presence or absence of mental illness, and age predicted a small but significant amount of the variance in participants’ pup play roles (χ2 [12] = 33.01, Nagelkerke R2 = .09, p < .001). AQ-S scores were the only variable which significantly differed between certain endorsed roles (χ2 [4] = 12.16, p = .016). With pups as the reference category which all others were compared against, participants with higher AQ-S scores were more likely to endorse a pup role than: i) one which involved being both pup and handler but pup-focused (B = −.03, Wald χ2 = 5.69, p = .017, OR: .97, CI: .95, 1.00); and ii) one which involved being pup and handler but handler-focused (B = −.08, Wald χ2 = 5.81, p = .016, OR: .93, CI: .87, .99). AQ-S scores did not differ significantly between those participants who were solely pups and those who were solely handlers, or between those who were solely pups and those who took on both roles equally.

Regarding pack membership and involvement in a pup community, whether participants belonged to a pack/family could be significantly predicted by our model with all three variables (χ2 [6] = 14.867, Nagelkerke R2 = .04, p = .021), although this effect did not reach significance according to our adjusted threshold (p = .017). The model’s near significance was driven by an effect of autistic traits (χ2 [2] =7.238, p = .027) where, in contrast with the reference group of individuals who belong to a pack/family, individuals with higher traits were more likely to endorse their desire to belong to a pack/family while not actually being so (B = .03, Wald χ2 = 6.337, p = .012, OR: 1.03, CI: 1.01, 1.06).

Likewise, while the model predicting membership of a pup community was not significant by our corrected significance threshold (χ2 [3] = 7.88, Nagelkerke R2 = .03, p = .049), autistic traits as a variable made a significant contribution within this model (χ2 [1] = 7.79, p = .005), reflecting that participants with higher autistic traits were less likely to belong to a pup community (B = .03, Wald χ2 = 7.57, p = .006, OR: 1.03, CI: 1.01, 1.05).

Linear Regression

Modeled alongside age and mental health conditions, autistic traits did not significantly predict social (F [3, 410] = .49, R2 = .00, p = .685) or sexual motivations (F [3, 410] = 1.37, R2 = .01, p = .252) for pup play, suggesting that those high or low in autistic traits did not differ in their self-reported motivations for pup play.

Taken separately, age and mental health status did not significantly predict strength of pup play identity (F [2, 405] = 2.360, p = .096). The addition of autistic traits to the model significantly increased the amount of variance explained [F [1, 404] = 4.368], but only from 1% to 5%. Accordingly, the model was still not significant in accordance with our corrected threshold (F [3, 407] = 3.04, R2 = .02, p = .029), indicating a tendency for lower FISI scores in participants with higher autistic traits (β = −.11, p = .037). As such, our hypothesis of stronger identification with pup play communities in those with higher autistic traits was not supported; rather, the data suggests that people with higher autistic traits may have a weaker sense of identification with pup play communities.

Broader Identity Resilience and Sociosexuality

While age and sex alone significantly predicted identity resilience (F [2, 408] = 37.81, p < .001), explaining 16% of the variance, the addition of autistic traits to the model resulted in a sizable increase to 29% of variance explained (F change [1, 407] = 73.83, p < .001). In this model (F [3, 407] = 54.32, R2 = .29, p < .001), higher autistic traits (β = −.38, p < .001) and the presence of diagnosed or suspected mental health conditions (β = −.37, p < .001) were associated with lower identity resilience.

Sociosexuality was not predicted by age and mental health status alone (p = .221), but the second level model including AQ-S scores significantly predicted 7% of the variance in sociosexuality (F [3, 407] = 10.898, R2 = .07, p < .001), with participants with more autistic traits exhibiting lower scores in sociosexuality (β = −.28, p < .001). As such, participants with more autistic traits had more conservative approaches to casual sex (“restricted sociosexuality”), whether attitudinally or behaviorally.

Discussion

This study examined the occurrence, characteristics, and social connections of autistic traits among people who engage in pup play, using data from an international study of pup play participants. More than one in two participants (55.7%) had AQ-S scores above 65; just over one in three (35.4%) scored 70 or over, a cutoff which is indicative of individuals with an autism diagnosis, with a sensitivity and specificity of .97 and .94, respectively (Hoekstra et al., Citation2011). The AQ-S is not a diagnostic instrument and so the number of participants who would meet present diagnostic criteria for autism is likely lower than one in three, even if one in three scored above the stringent AQ-S cutoff. Nevertheless, the AQ-S and its parent scale possess moderate convergent validity with gold-standard diagnostic measures (r = .7, in Lugo-Marín et al., Citation2019), and are more inclined, if anything, to false negatives rather than false positives (Bezemer et al., Citation2021). As such, that so many individuals scored above both cutoffs suggests that the prevalence of autism in the sample exceeded the 1% estimated prevalence of autism in the general population (Zeidan et al., Citation2022).

While elevated autistic traits are found in LGBT populations, evidence suggests higher autistic traits are likely in individuals who express sexualities outside of normative heterosexual and gay identity categories (Rudolph et al., Citation2018), and in those who are trans or gender-variant (Pasterski et al., Citation2014; Warrier et al., Citation2020). There is no evidence that cisgender gay men, the majority of our sample, tend toward higher rates of autistic traits. As such, the elevated rates of autistic traits in our sample do not seem to be an artifact of having an LGBT (and primarily gay male) sample, but rather support the contention that pup play may be of particular interest and appeal to people with autistic traits and, indeed, autistic people.

In explaining this elevated occurrence, we caution against simplistic readings that posit a biological or psychological rationale based on deficit models of these groups, given the stigma that is experienced by kinky people and autistic people (Boyd-Rogers & Maddox, Citation2022; Han et al., Citation2022). Instead, adopting the social model of disability, we suggest that pup play may be compatible with an autistic profile in several regards. While mainstream norms of sex are often implicit, kink scenes often have explicit and codified discussions of consent and sexual interests (Fanghanel, Citation2020), thus avoiding some of the difficulties reported by autistic people around negotiating sexual encounters (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Hancock et al., Citation2020). Meeting potential partners can also be difficult for autistic people, given the stigma attached to autism and the associated anxiety (Jones et al., Citation2021), and the communication barriers between autistic minorities and the neurotypical majority (Davis & Crompton, Citation2021; Yew et al., Citation2021). The high visibility of pup play communities online, including social media (Wignall, Citation2017), might facilitate an easier introduction to the community than traditional in-person interactions at kink events (Steinmetz & Maginn, Citation2014), providing a circumscribed setting in which to interact.

In this context, we hypothesized that people with autistic traits might prefer a pup role during pup play. There are fewer rules and responsibilities associated with being a pup compared to a handler, while handlers are required to interpret the needs and behavior of their pup(s). Furthermore, the gear associated with being a pup can restrict sound and vision which may be beneficial for some autistic people who may have sensory sensitivities (Gray et al., Citation2021). However, this role hypothesis was only partially supported: statistical contrasts in multinomial regression suggested that people high in autistic traits tended to prefer a pup role as opposed to one that was flexible (both flexible but pup-focused and flexible but handler-focused), but pups and handlers did not differ statistically in autistic traits. A preference for a single role rather than one that incorporates a degree of flexibility and role-change would be consistent with an autistic profile and was likewise partially supported (other than the finding that high-trait individuals were no more likely to endorse a pup-only role than one that was totally equal), but we suggest that these findings are tentative at present and should be interpreted with caution. Approximately 23% of participants endorsed a “switching” role (whether pup-focused, handler-focused, or totally equal), while pups comprised almost 68% of our sample (the small remainder identifying as handlers). While this partly reflects the popularity of the pup role against that of handler (Wignall et al., Citation2022), the imbalance in our sample precludes confident interpretation of these findings until more rigorous replication.

Regarding strength of association with a pup community, our hypothesis of stronger association for people with autistic traits was not supported. Rather, higher autistic traits tended to be associated with lower FISI scores, suggesting a weaker sense of identification with the pup community, although this relationship did not survive statistical correction. We also found that those with high autistic traits tended toward lower likelihood of belonging to pup play communities and were most likely to endorse not belonging to a family/pack while wanting to. Further research is needed to investigate these findings, but several interpretations might be posited based on existing research. First, it is important to recognize that autistic people are a marginalized group who are at higher risk of social exclusion and victimization (Jones et al., Citation2021). While some engage in camouflaging behaviors as a means of self-protection (Bradley et al., Citation2021; Han et al., Citation2022), others report avoiding contact with other people out of fear (Jones et al., Citation2021). It may be that they avoid close engagement with pup communities for similar reasons. The hybrid (online and offline) nature of pup communities may facilitate access for neurodivergent people, but they may remain in the online sphere and thus have less strong attachments to pup play communities. It is also possible that due to marginalization, social anxiety or other reasons, people with autistic traits (and indeed autistic people) might prefer pup play as a solo or dyadic practice and identity, rather than the community aspects. Notably, the four items of the FISI capture not only self-identification with the community, but self-identification with one’s role during pup play. As such, future measures might tease apart these two potentially contradictory elements and investigate more subtle differences in the way people with high autistic traits engage with pup play and other practitioners.

We also examined broader identity resilience and attitudes, desires and behaviors around sex and relationships, finding that autistic traits are negatively associated with identity resilience, explaining an extra 13% of the variance in identity resilience. This finding is consistent with the literature suggesting lower self-esteem and self-efficacy in autistic adults and individuals with higher autistic traits (Buckley et al., Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2020), and better wellbeing in those with a strong sense of positive distinctiveness (Cooper et al., Citation2021). In the absence of more rigorous measures of psychopathology and other personality attributes, however, part of the variance attributed here to autistic traits may be influenced by third factors. Finally, we found that people with higher autistic traits had lower sociosexuality scores. This corresponds with existing research on autistic people (Del Giudice et al., Citation2014; Ponzi et al., Citation2016), where people with higher autistic traits prefer predictability and relationship stability, low novelty-seeking and risk taking, and experience greater stress in sexual/courtship situations.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this research, including the predominantly community-based sample and recruitment processes, meaning that the findings related to occurrence cannot be generalized to population-wide prevalence. The sample primarily consisted of White, gay men which, although typical of pup play communities (Wignall et al., Citation2022), limits generalization to more diverse samples. Indeed, in the absence of any suitable comparison groups (such as gay men who do not engage in pup play) and given the greater gender and sexual diversity of the autistic community (McQuaid et al., Citation2022; Warrier et al., Citation2020), we cannot negate the possibility that the higher autistic traits of our sample are associated with their minoritized gender/sexual identities, rather than solely reflecting a particular inclination of high-trait individuals toward pup play.

The present study examined potential autism through the metric of autistic traits, quantifiable features considered analogous to autism and possibly reflective of genetic liability to the same (Abu-Akel et al., Citation2019). This approach is common given that many autistic adults remain undiagnosed for a variety of social reasons: many grew up prior to improved clinical recognition of autism in people without intellectual disability, and barriers to obtaining a diagnosis only increase with age (de Broize et al., Citation2022; Crane et al., Citation2018; Wigham et al., Citation2022). However, the chief limitation to using such screening measures as indicative of autism is that while the AQ-S possesses high specificity and sensitivity for autism (Hoekstra et al., Citation2011), it is also sensitive to factors which were not measured and controlled for here, such as generalized anxiety and social anxiety in marginalized groups (Nobili et al., Citation2018). Without clinically validating the presence or absence of autism in participants, it is impossible to ascertain that those over cutoff were autistic or whether traits were artificially inflated by the presence of a confound like anxiety (particularly as many participants self-reported mental health difficulties). Relatedly, it is important to recognize that correlation analysis cannot ascertain a causative role of a specific feature, such as autistic traits (or autism), in the development and expression of sexual preferences. Given these issues, we caution against interpretation of the findings in absolute terms, particularly given the risks that invalid assumptions could pose to already marginalized groups. Importantly, even if levels of autism are lower than the AQ-S scores suggest, the results still point to the presence of significant neurodivergence in the sample and a need to understand neurodiversity in sex research.

Future Directions

This study constitutes a preliminary investigation, and the findings require replication and point to a clear need for more research on autism and kink, as well as neurodivergence in sex research more generally. Alongside more rigorous quantitative approaches, understanding the meaning of relationships suggested in the present data (such as the weaker identification of high-trait adults with the pup community), if valid, necessitates use of qualitative methodologies to understand the motivations and experiences of autistic people who engage in pup play, including perceived benefits and issues they may encounter. While the FISI allowed some insight into attachment to the pup community, much more nuanced questions are required to understand identity and community attachment in these participants. Such research should connect with a broader body of research on the intersections between autism and sexuality that extend beyond deficit models. This research may focus on kink more generally, on other forms of sexualized leisure, and the intersections of technology and sexuality for autistic people. This latter area offers significant avenues for considering how the internet may enhance accessibility and positive engagement in sexual communities for autistic people. It is also important to consider other aspects of neurodivergent identity and experiences, such as anxiety and experiences of marginalization, which might influence courtship behavior and sexual and gender role preferences within the neurodivergent community.

Beyond formally recognized (diagnosed) autism, autistic traits are influential to the romantic and sexual behavior of individuals throughout the general population, despite their surprising omission from research in this field. In addition to their associations with mental ill-health (Liew et al., Citation2015; Pelton et al., Citation2020), several studies link autistic traits with lower relationship satisfaction, lower sexual satisfaction, and courtship difficulties (Beffel et al., Citation2021; Byers & Nichols, Citation2014; Pollmann et al., Citation2010). Thus, an autism diagnosis is not required for high quality sexuality research to expand beyond neurotypical samples and adopt neurodiverse approaches, particularly given the barriers which prevent some from obtaining diagnosis (Wigham et al., Citation2022), and even the stigma which leads some to avoid disclosing their diagnosis (Farsinejad et al., Citation2022). By studying diverse sexual behaviors in the context of neurodivergent features as well as in self-identifying and diagnosed individuals, future research could contribute to the growing literature on neurodivergence that seeks to challenge both infantilization and pathologizing approaches, particularly as it is applied to sexuality (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Egner, Citation2019; Kattari et al., Citation2021). We argue this is particularly important in relation to the intersectional experiences of individuals who are LGBT, whose sexual orientations are often invalidated due to their neurodivergence, especially if they also have an intellectual disability (Abbott, Citation2020; McAuliffe et al., Citation2023).

In conclusion, this study has examined autistic traits of a large community sample of people who engage in pup play. Finding a high occurrence of people with autistic traits above the cutoffs which typically indicate possible autism, we found that participants with autistic traits preferred non-flexible roles (pup or handler), were less likely to belong to pup play social communities or to closer-knit family/pack units despite wishing to, and perhaps accordingly had lower identification with pup play communities than participants with low ASQ scores. They also tended to demonstrate lower identity resilience and more restricted sociosexuality. In so doing, we show that there is a need to consider intersections of autism and sexual subcultures in social science research, and to expand this to consider neurodivergence and sexual cultures more broadly. We call for more research on this topic, including qualitative research that centers the experiences of neurodivergent people in non-stigmatizing ways, in line with the growing research on neurodivergence that has yet to be embraced by sex researchers.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Scoring of the AQ-S differs from its parent scale, the 50-item AQ: the original can be scored from 1–4, but is most frequently scored dichotomously with the two answers indicative of autism (“Strongly” or “Slightly” agree/disagree, depending on the direction of the item) scored 1, the other two 0. As such, AQ-S scores as computed here cannot be transparently compared with scores based on other, dichotomously scored versions of the parent scale.

References

- Abbott, D. (2020). “Tick the straight box”: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT+) people with intellectual disabilities in the UK. In R. Shuttleworth & L. Mona (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of disability and sexuality (pp. 197–207). Routledge.

- Abu-Akel, A., Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S., & Heinke, D. (2019). The distribution of autistic traits across the autism spectrum: Evidence for discontinuous dimensional subpopulations underlying the autism continuum. Molecular Autism, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0275-3

- Barnett, J., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2015). Qualitative exploration of sexual experiences among adults on the autism spectrum: Implications for sex education. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(4), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1363/47e5715

- Beffel, J., Cary, K., Nuttall, A., Chopik, W., & Maas, M. (2021). Associations between the broad autism phenotype, adult attachment, and relationship satisfaction among emerging adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 168(1), Article 110409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110409

- Bennett, M., Webster, A., Goodall, E., Rowland, S., Bennett, M., Webster, A., Goodall, E., & Rowland, S. (2018). Intimacy and romance across the autism spectrum: Unpacking the “not interested in sex” myth. In M. Bennet, A. Webster, E. Goodall, & S. Rowland (Eds.), Life on the autism spectrum: Translating myths and misconceptions into positive futures (pp. 195–211). Springer.

- Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., & Jackson-Perry, D. (2021). Not doing it properly? (Re)producing and resisting knowledge through narratives of autistic sexualities. Sexuality and Disability, 39(2), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-020-09624-5

- Bezemer, M., Blijd-Hoogewys, E., & Meek-Heekelaar, M. (2021). The predictive value of the AQ and the SRS-A in the diagnosis of ASD in adults in clinical practice. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(7), 2402–2415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04699-7

- Boyd-Rogers, C., & Maddox, G. (2022). LGBTQIA+ and heterosexual BDSM practitioners: Discrimination, stigma, tabooness, support, and community involvement. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(7), 1747–1762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-022-00759-y

- Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autistic adults’ experiences of camouflaging and its perceived impact on mental health. Autism in Adulthood, 3(4), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0071

- Breakwell, G., Fino, E., & Jaspal, R. (2022). The Identity Resilience Index: Development and validation in two UK samples. Identity, 22(2), 166–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1957895

- Brown, A., Barker, E., & Rahman, Q. (2020). A systematic scoping review of the prevalence, etiological, psychological, and interpersonal factors associated with BDSM. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(6), 781–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1665619

- Buckley, E., Pellicano, E., & Remington, A. (2021). Higher levels of autistic traits associated with lower levels of self-efficacy and wellbeing for performing arts professionals. PLoS One, 16(2), e0246423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246423

- Byers, E., & Nichols, S. (2014). Sexual satisfaction of high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder. Sexuality and Disability, 32(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-014-9351-y

- Cascalheira, C., Ijebor, E., Salkowitz, Y., Hitter, T., & Boyce, A. (2021). Curative kink: Survivors of early abuse transform trauma through BDSM. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. Online First, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.1937599

- Cooper, R., Cooper, K., Russell, A., & Smith, L. (2021). “I’m proud to be a little bit different”: The effects of autistic individuals’ perceptions of autism and autism social identity on their collective self-esteem. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(2), 704–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04575-4

- Crane, L., Batty, R., Adeyinka, H., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. L. (2018). Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3761–3772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3639-1

- Crompton, C., Hallett, S., Ropar, D., Flynn, E., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). ‘I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 24(6), 1438–1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320908976

- Daniels, M. (2005). Woof! Perspectives in the erotic care and training of the human dog. Nazca Plains Corporation.

- Davis, R., & Crompton, C. (2021). What do new findings about social interaction in autistic adults mean for neurodevelopmental research? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(3), 649–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620958010

- de Broize, M., Evans, K., Whitehouse, A. J., Wray, J., Eapen, V., & Urbanowicz, A. (2022). Exploring the experience of seeking an autism diagnosis as an adult. Autism in Adulthood, 4(2), 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0028

- Del Giudice, M., Klimczuk, A., Traficonte, D., & Maestripieri, D. (2014). Autistic-like and schizotypal traits in a life history perspective: Diametrical associations with impulsivity, sensation seeking, and sociosexual behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(5), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.05.007

- Egner, J. (2019). “The disability rights community was never mine”: Neuroqueer disidentification. Gender & Society, 33(1), 123–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243218803284

- Fanghanel, A. (2020). Asking for it: BDSM sexual practice and the trouble of consent. Sexualities, 23(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719828933

- Farsinejad, A., Russell, A., & Butler, C. (2022). Autism disclosure: The decisions autistic adults make. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 93(5), 101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2022.101936

- Gray, S., Kirby, A., & Graham Holmes, L. (2021). Autistic narratives of sensory features, sexuality, and relationships. Autism in Adulthood, 3(3), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0049

- Griffiths, S., Allison, C., Kenny, R., Holt, R., Smith, P., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Research, 12(10), 1516–1528. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2162

- Hancock, G., Stokes, M., & Mesibov, G. (2020). Differences in romantic relationship experiences for individuals with an autism spectrum disorder. Sexuality and Disability, 38(2), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-019-09573-8

- Han, E., Scior, K., Avramides, K., & Crane, L. (2022). A systematic review on autistic people’s experiences of stigma and coping strategies. Autism Research, 15(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2652

- Hedley, D., Hayward, S., Clarke, A., Uljarević, M., & Stokes, M. (2022). Suicide and autism: A lifespan perspective. In R. Stancliffe, M. Wiese, P. McCallion, & M. McCarron (Eds.), End of life and people with intellectual and developmental disability (pp. 59–94). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hillier, A., Gallop, N., Mendes, E., Tellez, D., Buckingham, A., Nizami, A., & O’Toole, D. (2020). LGBTQ+ and autism spectrum disorder: Experiences and challenges. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1594484

- Hoekstra, R., Vinkhuyzen, A., Wheelwright, S., Bartels, M., Boomsma, D., Baron-Cohen, S., Posthuma, D., & Van Der Sluis, S. (2011). The construction and validation of an abridged version of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ-Short Form). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1073-0

- Hogan, M., & Micucci, J. (2020). Same-sex relationships of men with autism spectrum disorder in middle adulthood: An interpretative phenomenological study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(2), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000372

- Howard, P., & Sedgewick, F. (2021). ‘Anything but the phone!’: Communication mode preferences in the autism community. Autism, 25(8), 2265–2278. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211014995

- Jaspal, R., & Breakwell, G. M. (2022). Identity resilience, social support and internalised homonegativity in gay men. Psychology and Sexuality, 13(5), 1270–1287. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.2016916

- Jaswal, V., & Akhtar, N. (2019). Being versus appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 42, Article e82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X18001826

- Jones, S. C., Gordon, C. S., Akram, M., Murphy, N., & Sharkie, F. (2021). Inclusion, exclusion and isolation of autistic people: Community attitudes and autistic people’s experiences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(3), 1131–1142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04998-7

- Joyal, C., Carpentier, J., McKinnon, S., Normand, C., & Poulin, M. (2021). Sexual knowledge, desires, and experience of adolescents and young adults with an autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12, Article 685256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685256

- Kattari, S., Hecht, H., & Isaacs, Y. (2021). Sexy spoonies and crip sex: Sexuality and disability in a social work context. In S. Dodd (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of social work and sexualities (pp. 269–284). Routledge.

- Lai, M., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

- Lawson, J., & Langdridge, D. (2019). History, culture and practice of puppy play. Sexualities, 23(4), 574–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719839914

- Liew, S., Thevaraja, N., Hong, R., & Magiati, I. (2015). The relationship between autistic traits and social anxiety, worry, obsessive–compulsive, and depressive symptoms: Specific and non-specific mediators in a student sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(3), 858–872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2238-z

- Lilley, R., Lawson, W., Hall, G., Mahony, J., Clapham, H., Heyworth, M., Arnold, S. R., Trollor, J. N., Yudell, M., & Pellicano, E. (2022). ‘A way to be me’: Autobiographical reflections of autistic adults diagnosed in mid-to-late adulthood. Autism, 26(6), 1395–1408. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211050694

- Lugo-Marín, J., Díez-Villoria, E., Magán-Maganto, M., Pérez-Méndez, L., Alviani, M., de la Fuente-Portero, J. A., & Canal-Bedia, R. (2019). Spanish validation of the Autism Quotient Short Form Questionnaire for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(11), 4375–4389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04127-5

- MacLennan, K., O’Brien, S., & Tavassoli, T. (2022). In our own words: The complex sensory experiences of autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(7), 3061–3075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05186-3

- Matchett, R., & Berkowitz, D. (2023). Play, performativity, and the production of a pup identity in the United States. In B. Simula, R. Bauer, & L. Wignall (Eds.), The power of BDSM: Play, communities, and consent in the 21st century (pp. 75–93). Oxford University Press.

- McAuliffe, C., Walsh, R., & Cage, E. (2023). “My whole life has been a process of finding labels that fit”: A thematic analysis of autistic LGBTQIA+ identity and inclusion in the LGBTQIA+ community. Autism in Adulthood, 5(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0074

- McQuaid, G., Gendy, J., Lee, N., & Wallace, G. (2022). Sexual minority identities in autistic adults: Diversity and associations with mental health symptoms and subjective quality of life. Autism in Adulthood, 5(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0088

- Moseley, R., Gregory, N., Smith, P., Allison, C., Cassidy, S., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2022). The relevance of the interpersonal theory of suicide for predicting past-year and lifetime suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 13(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-022-00495-5

- Nguyen, W., Ownsworth, T., Nicol, C., & Zimmerman, D. (2020). How I see and feel about myself: Domain-specific self-concept and self-esteem in autistic adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(913), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00913

- Nobili, A., Glazebrook, C., Bouman, W., Glidden, D., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., & Arcelus, J. (2018). Autistic traits in treatment-seeking transgender adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(12), 3984–3994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3557-2

- Paarnio, M., Sandman, N., Källström, M., Johansson, A., & Jern, P. (2022). The prevalence of BDSM in Finland and the association between BDSM interest and personality traits. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(4), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.2015745

- Pasterski, V., Gilligan, L., & Curtis, R. (2014). Traits of autism spectrum disorders in adults with gender dysphoria. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(2), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0154-5

- Pearson, A., & Hodgetts, S. (2023). “Comforting, reassuring, and … hot”: A qualitative exploration of engaging in bondage, discipline, domination, submission, sadism and (sado)masochism and kink from the perspective of autistic adults. Autism in Adulthood, Online First, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2022.0103

- Pearson, A., Rees, J., & Forster, S. (2022). “This was just how this friendship worked”: Experiences of interpersonal victimization among autistic adults. Autism in Adulthood, 4(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2021.0035

- Pellicano, E., Fatima, U., Hall, G., Heyworth, M., Lawson, W., Lilley, R., Mahony, J., & Stears, M. (2022). A capabilities approach to understanding and supporting autistic adulthood. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(11), 624–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00099-z

- Pelton, M. K., Crawford, H., Robertson, A. E., Rodgers, J., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2020). Understanding suicide risk in autistic adults: Comparing the interpersonal theory of suicide in autistic and non-autistic samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 3620–3637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04393-8

- Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1113–1135. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1113

- Pliskin, A. (2022). Autism, sexuality, and BDSM. Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture, 4(1), 9, 70–91. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought/vol4/iss1/9

- Pollmann, M., Finkenauer, C., & Begeer, S. (2010). Mediators of the link between autistic traits and relationship satisfaction in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0888-z

- Ponzi, D., Henry, A., Kubicki, K., Nickels, N., Wilson, M., & Maestripieri, D. (2016). Autistic-like traits, sociosexuality, and hormonal responses to socially stressful and sexually arousing stimuli in male college students. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 2(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0034-4

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Rudolph, C., Lundin, A., Åhs, J., Dalman, C., & Kosidou, K. (2018). Sexual orientation in individuals with autistic traits: Population based study of 47,000 adults in Stockholm County. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 619–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3369-9

- Sala, G., Hooley, M., & Stokes, M. (2020). Romantic intimacy in autism: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4133–4147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04377-8

- Schöttle, D., Briken, P., Tüscher, O., & Turner, D. (2022). Sexuality in autism: Hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.4/dschoettle

- Seers, K., & Hogg, R. (2021). You don’t look autistic’: A qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of being the ‘autistic other. Autism, 25(6), 1553–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361321993722

- St Clair, J. (2015). Bark! Nazca Plains Corporation.

- Steinmetz, C., & Maginn, P. (2014). The landscape of BDSM venues: A view from down under. In C. Steinmetz & P. Maginn (Eds.), (Sub)urban sexscapes (pp. 117–137). Routledge.

- Stewart, G., Corbett, A., Ballard, C., Creese, B., Aarsland, D., Hampshire, A., Charlton, R. A., & Happé, F. (2022). Traumatic life experiences and post-traumatic stress symptoms in middle-aged and older adults with and without autistic traits. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5669

- Warrier, V., Greenberg, D., Weir, E., Buckingham, C., Smith, P., Lai, M., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17794-1

- Wigham, S., Ingham, B., Le Couteur, A., Wilson, C., Ensum, I., & Parr, J. R. (2022). A survey of autistic adults, relatives and clinical teams in the United Kingdom: And Delphi process consensus statements on optimal autism diagnostic assessment for adults. Autism, 26(8), 1959–1972. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211073020

- Wignall, L. (2017). The sexual use of a social networking site: The case of pup twitter. Sociological Research Online, 22(3), 21–37. http://doi.org/10.1177/1360780417724066

- Wignall, L. (2022). Kinky in the digital age: Gay men’s subcultures and social identities. Oxford University Press.

- Wignall, L., & McCormack, M. (2017). An exploratory study of a new kink activity: “Pup play.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0636-8

- Wignall, L., McCormack, M., Cook, T., & Jaspal, R. (2022). Findings from a community survey of individuals who engage in pup play. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(7), 3637–3646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02225-z

- Woods, R. (2017). Exploring how the social model of disability can be re-invigorated for autism: In response to Jonathan Levitt. Disability & Society, 32(7), 1090–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1328157

- Yew, R., Samuel, P., Hooley, M., Mesibov, G., & Stokes, M. (2021). A systematic review of romantic relationship initiation and maintenance factors in autism. Personal Relationships, 28(4), 777–802. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12397

- Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2696