ABSTRACT

Sexual wellbeing is an important aspect of population health. Addressing and monitoring it as a distinct issue requires valid measures. Our previous conceptual work identified seven domains of sexual wellbeing: security; respect; self-esteem; resilience; forgiveness; self-determination; and comfort. Here, we describe the development and validation of a measure of sexual wellbeing reflecting these domains. Based on the analysis of 40 semi-structured interviews, we operationalized domains into items, and refined them via cognitive interviews, workshops, and expert review. We tested the items via two web-based surveys (n = 590; n = 814). Using data from the first survey, we carried out exploratory factor analysis to assess and eliminate poor performing items. Using data from the second survey, we carried out confirmatory factor analysis to examine model fit and associations between the item reduced measure and external variables hypothesized to correlate with sexual wellbeing (external validity). A sub-sample (n = 113) repeated the second survey after 2 weeks to evaluate test–retest reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis indicated that a “general specific model” had best fit (RMSEA: 0.064; CFI: 0.975, TLI: 0.962), and functioned equivalently across age group, gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status. The final Natsal-SW measure comprised 13 items (from an initial set of 25). It was associated with external variables in the directions hypothesized (all p < .001), including mental wellbeing (0.454), self-esteem (0.564), body image (0.232), depression (−0.384), anxiety (−0.340), sexual satisfaction (0.680) and sexual distress (−0.615), and demonstrated good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.78). The measure enables sexual wellbeing to be quantified and understood within and across populations.

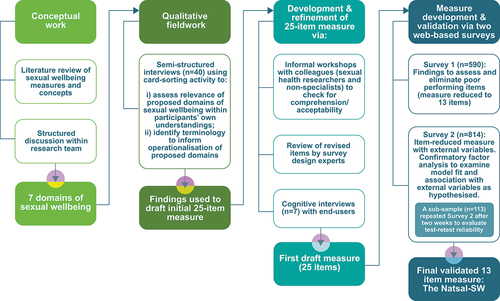

This paper reports on the development and validation of a brief population measure of sexual wellbeing. It is part of a broader project and suite of papers (Mitchell et al., Citation2021; Lewis, Citationin review) which seek to conceptualize and operationalize sexual wellbeing for public health research and practice. We begin by introducing key concepts and considerations from the adjacent fields of subjective and psychological wellbeing. We then review how sexual wellbeing has been defined and measured in sexology, highlighting current gaps. We argue that sexual wellbeing is a multi-dimensional construct, distinct but overlapping with sexual health, sexual justice, and sexual pleasure. We propose that a new measure is required which captures a range of psychosocial dimensions and reflects structural influences on the capacity to experience sexual wellbeing.

Measurement of Subjective/Psychological Wellbeing and the Absence of Sexual Dimensions

Wellbeing can be defined as “feeling good and functioning well” (Ruggeri et al., Citation2020) and can be measured at individual, community, and national levels. While social and economic policies traditionally prioritize material wellbeing (measured via indicators such as income, wealth, and education), there is increasing recognition that psychological and subjective wellbeing also matters for population health (Diener et al., Citation2017). Psychological wellbeing is equated with positive mental health, defined by the World Health Organization as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (World Health Organization, Citation2004, p. 59). Psychological wellbeing includes subjective wellbeing, which broadly refers to cognitive and affective evaluations of one’s life (Diener et al., Citation2003). Self-evaluation of wellbeing is typically based on two different forms of happiness: hedonic (pleasure) and eudaimonic (meaning and purpose) (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001; Seligman, Citation2011). Psychological wellbeing comprises things like autonomy, environmental mastery, positive relationships, meaning or purpose, and self-acceptance. Subjective wellbeing is often narrowly defined and measured as happiness and life satisfaction, but this approach is limited in capturing how people are functioning and their psychological wellbeing (Ruggeri et al., Citation2020). There has been increasing recognition that psychological wellbeing is a multi-dimensional construct, and several key attempts to provide multi-dimensional measurement. For instance, Huppert and So (Citation2013) identified 10 features of flourishing (high well-being) using data from the European Social Survey (Huppert & So, Citation2013) including self-esteem, resilience, meaning, and positive relationships. Validated multidimensional brief measures of subjective wellbeing, such as the Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWEBS, Tennant et al., Citation2007) and the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF, Keyes, Citation2002) have also gained traction in recent years.

Positive relationships are a common indicator of subjective wellbeing but sexual dimensions are typically overlooked (Hooghe, Citation2012). This omission is odd given the centrality of sexuality to human experience and given that sex is a basic human capability (Nussbaum & Sen, Citation1993). We have previously argued that sexual wellbeing could be monitored as a meaningful indicator of population wellbeing (Mitchell et al., Citation2021), for instance, highlighting important inequities in the extent to which people are able to convert resources into health functioning (Lorimer, et al., Citation2022). Supporting this idea, a recent review found strong empirical evidence of the link between poverty and sexual wellbeing, which they defined as “positive, pleasurable, and safe sexual experiences, both physical and psychological, that both enable and intersect with other key elements of sexuality” (Higgins et al., Citation2022, p. 940). The authors proposed three pathways through which “erotic inequalities” emerge: housing and sexual spaces; financial-associated stress; and poverty-fueled lowered expectations for enjoyable sexual experiences (Higgins et al., Citation2022). The argument for including sexuality as an integral part of individual wellbeing has also been made on psychometric grounds: analysis of Flemish population data showed that including an item on sexual satisfaction in a brief (5-item) measure of wellbeing improved the scale properties (Hooghe, Citation2012). The author concluded that “if one wants to arrive at a full understanding of what wellbeing actually means for people, the sexual element cannot be over-looked” (Hooghe, Citation2012, p. 272). This study was ground-breaking in making the case for inclusion of a sexual dimension within a general measure of wellbeing, but the included item was limited to a single item on sexual satisfaction.

The Conceptualization and Measurement of Wellbeing in Sexology

If sexual dimensions are to be included in subjective measures of wellbeing, or tracked as an indicator of population health, then the concept of sexual wellbeing must first be clarified. Good measures of sexual wellbeing are also of direct value in sexology research, for instance to evaluate sexual health interventions. Within the field of sexology, there is burgeoning interest in the definition and measurement of sexual wellbeing. A recent review (Lorimer et al., Citation2019) identified 162 studies in which sexual wellbeing was ostensibly included as an outcome; all studies either purported to directly measure sexual wellbeing or otherwise employed the term in describing their outcomes. Only 10 of the studies explicitly defined sexual wellbeing. The review attested to the wide range of facets of sexuality currently considered as sexual wellbeing, with studies focusing on aspects as diverse as sexual assertiveness, sexual closeness, and gender socialization. There were few multi-domain measures, and the authors lamented the lack of studies focused on socio-cultural features such as sexual health rights, stigma, and freedom to express oneself sexually. Building on the Lorimer review, Sundgren and colleagues recently reviewed 74 psychometric measures of sexual wellbeing (Sundgren et al., Citation2022). Like Lorimer and colleagues, they searched using the term “sexual wellbeing” and identified measures on wide-ranging aspects of sexuality including communication, sexual functioning, and rewards/costs of sexual behavior (Sundgren et al., Citation2022). Neither review identified a single definition or measure that adequately captured sexual wellbeing. Both reviews affirmed that definitional challenges affecting general wellbeing (e.g. subjectivity; variation in individual priorities) also apply to sexual wellbeing.

By nature of their search strategy, the reviews of Lorimer et al. and Sundgren et al. included studies that were seeking to measure other constructs (such as sexual function) but employed sexual wellbeing as a synonym. There are relatively few studies that have measured sexual wellbeing as an explicitly defined construct. Among these, notable earlier attempts tended to conflate sexual wellbeing with sexual satisfaction. For instance, applying the idea of subjective wellbeing as “cognitive and emotional evaluation,” Laumann et al. (Citation2006) extended this to sexual wellbeing, measured via three satisfaction statements (with the physical and emotional relationship and with sexual health/function) plus a statement on the importance of sex.

The interchange of sexual wellbeing with satisfaction is common in contexts such as treatment for sexual difficulties. However, equation of sexual wellbeing with sexual satisfaction may be limited in the same way that equating psychological wellbeing with life satisfaction is limited. Usually assessed as a single item, sexual satisfaction is limited in capturing psychological aspects of sexual wellbeing, including positive emotions and self-esteem. It is also limited in assessing capabilities integral to wellbeing, such as the freedom to express one’s sexuality without censure or retribution (Lorimer et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). For instance, laws prohibiting abortion or homosexuality directly limit capabilities for sexual wellbeing in ways that reach far beyond satisfaction with sexual activity (Lorimer et al., Citation2022). Capability, or freedom to achieve, is an important concept which recognizes structural inequities in opportunities to flourish and demands a focus on justice (Lorimer et al., Citation2022; Willen et al., Citation2022). Sexual satisfaction is also limited in encapsulating the complexity of intra- and interpersonal factors that shape a sense of sexual wellbeing (Lorimer et al., Citation2019). This includes factors such as internalized shame or unresolved issues in a sexual relationship. Crucially, assessment of satisfaction depends on individual expectations of satisfaction and these may be poverty-fueled and/or constrained, particularly among those with less power and agency, and those whose sexual rights are restricted (Higgins et al., Citation2022; McClelland, Citation2010). Finally, responses to questions on sexual satisfaction often focus on event-level assessments rather than more general summations. Assessments of individual sexual events are momentary and can be limited in capturing more stable feelings and thoughts about sexual wellbeing over time (Rosen et al., Citation2015).

In parallel with the subjective wellbeing field, more recent attempts at measurement have recognized sexual wellbeing as a multi-dimensional construct and have proposed a breadth of potential dimensions. Muise et al. (Citation2010) measured four subjective aspects of sexual wellbeing: satisfaction with sexual relationships and functioning; sexual awareness; sexual self-esteem; and body image esteem. In their study of sexual wellness in later life, Syme and colleagues coded participant perspectives on sexual wellbeing and proposed measurement across four dimensions: psychological (cognitions, emotions, and concepts), social (relationship, shared experience), biological/behavioral (functioning, behaviours/script) and cultural (age/time in life, gender/sexual orientation) aspects (373 participants aged 50 plus (Syme et al., Citation2019)). Also focusing on older people (aged 60 plus), Štulhofer et al. (Citation2019) evaluated a five-dimension measure of sexual wellbeing focused on sexual and intimate activities: intimacy during sex, distress over sexual function, frequency of cuddling, sexual satisfaction, and perceived sexual compatibility (Štulhofer et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Another recent five-item measure similarly focused on intimate and sexual activities and was validated in both trans and cis populations (Gerymski, Citation2021).

The Need for a Population-Health Measure of Sexual Wellbeing

In sum, the field of sexology has progressed to viewing sexual wellbeing as multi-dimensional and broader than sexual satisfaction. However, there remains wide variation in aspects included in existing measures, and a tendency to focus on what people do, rather than on how they think or feel (cognitive and affective evaluation). This brings a disconnect between important work on psychological wellbeing, and work within sexology to measure sexual wellbeing. There is also limited effort to encapsulate how sexual wellbeing is shaped by others and by the broader socio-cultural context (Lorimer et al., Citation2022). Narrow conceptualization and measurement of sexual wellbeing limits understanding of how sexuality affects broader wellbeing (Stephenson & Meston, Citation2015) and may mean missed opportunities for sexual health interventions to address issues such as shame and stigma which curb engagement with services and ability to minimize personal risk.

Prior Conceptual Work to Develop the Natsal-SW

To address these gaps, we sought to develop a brief multi-dimensional measure of sexual wellbeing for population surveys. The four key stages of the project are summarised in . In this paper, we describe the third and fourth stages (SW development and refinement, and validation). We first briefly summarize findings from the first and second stages to provide context. The study began with a concept mapping process which included discussion among authors, and engagement with wide-ranging literature, including reviews of sexual wellbeing measures and concepts (McLinden, Citation2017). We proposed that sexual wellbeing should be considered as one of the four pillars of public health research and practice in sexuality, alongside sexual pleasure, sexual justice, and sexual health (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). A crucial insight We gain in differentiating sexual wellbeing from sexual health, pleasure, and justice is that the experiences of sexuality over a lifetime are too nuanced to be usefully conflated. As previously noted, conflation of sexual wellbeing with, for example, sexual satisfaction or sexual function, is a key limitation of existing measures.

We proposed that the sexual wellbeing pillar could comprise seven domains – sexual safety and security, sexual respect, sexual self-esteem, resilience in relation to sexual experiences, forgiveness (of self and others) of sexual harms, self-determination in one’s sex life and comfort with sexuality – and we outlined the connection of each domain to sexual wellbeing and their relevance to public health (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). In accord with some authors’ emphasis on interpersonal and social/cultural influences on sexual wellbeing (see for example, Higgins et al. (Citation2022)), we incorporated domains of sexual respect, sexual forgiveness, and sexual resilience to reflect those essential adaptive capacities that were not well represented in existing measures. The remaining domains – sexual safety and security, sexual self-esteem, sexual self-determination, and sexual comfort – addressed self-perceptions and resonated with domains reflected in other measures of sexual wellbeing.

Subsequently, we undertook qualitative work to explore individual meanings of sexual wellbeing, and to assess whether our seven theoretically proposed domains resonated with participants’ experiences (stage two, ). The qualitative stage is explained briefly below (see Method) and findings are presented in detail elsewhere (Lewis et al., in review). In brief, participants’ accounts confirmed the relevance and inter-relatedness of the seven domains. The salience of each domain depended on the extent to which participants had experienced adversity in that domain, with salience varying mostly by gender and sexual orientation. We also found that social relationships and structural inequalities could strengthen or undermine sexual wellbeing.

Our seven domains thus provide an essential scaffold for conceptualizing and operationalizing sexual wellbeing defined by Muise et al. (Citation2010, p. 917) as the “cognitive and affective evaluation of oneself as a sexual being” (see also similar definitions in Laumann et al. (Citation2006, p. 146), and Træen and Schaller (Citation2010, p. 180) among others). During early project phases, we employed this as a working definition because of the direct link with positive psychology. We later defined sexual wellbeing ourselves as, “sexual emotions and cognitions which include feeling safe, respected, comfortable, confident, autonomous, secure, and able to work through change, challenges, and past traumas”. This enlarged definition reflects the fact that sexual wellbeing contains corrective as well as evaluative functions. By corrective we mean that there is potential for community and individual level interventions to improve sexual wellbeing. By evaluative we mean that sexual wellbeing could be an appropriate outcome – or measurable success indicator – of public health intervention. For instance, a strategy to improve access and quality of sexual health services should have measurable impact on the sexual wellbeing of the target population.

In this, our seven domains of sexual wellbeing provide points for amelioration of factors detracting from wellbeing (for example, psychological recovery from a previous experience of nonconsensual sex), or for increasing wellbeing in response to reinterpreted or new experiences (for example, a new and nurturing sexual relationship). In other words, there exists a balancing loop in which disruptive life experiences can reset sexual wellbeing to a new setpoint or result in return to a previous state. This balancing loop reflects a fluctuating state between one’s ongoing challenges (such as maintaining one’s sexual self-esteem) and resources (such as a current partner who is adoring) (Dodge et al., Citation2012).

In this present study, we describe the process of operationalizing these domains into a valid measure, the Natsal-Sexual Wellbeing measure (Natsal-SW). From the outset we specified that both concept and measure should be (1) (reasonably) distinct from related concepts of sexual health, sexual satisfaction, sexual pleasure or sexual function a (2); be relevant regardless of whether one is sexually active and irrespective of partnership status; focus on aspects of sexuality amenable to change through public health or clinical intervention a (3); and represent a summation of experience and near-future expectations (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). The impetus for this research was to develop a measure for inclusion in the fourth National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-4).

Method

Item Development and Selection

Items for the Natsal-SW were developed via qualitative fieldwork, reviews of existing items and measures, informal workshops, and cognitive interviews. The full program of work is summarized in .

As part of development work for the Natsal-4 survey, we undertook 40 qualitative interviews. We sought to explore participant understanding, experiences, and language in relation to sexual wellbeing, and to assess whether our seven proposed domains aligned with participants’ views and experiences. Interviews were undertaken with participants aged 18 to 59, recruited via a professional agency (http://www.propeller-research.co.uk/). We used quota sampling to ensure variation in terms of age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, current relationship status, area level deprivation, and geographic spread across the UK. Participants were asked to describe what sexual wellbeing meant to them, and to reflect on their experiences in relation to feelings of sexual wellbeing (or otherwise). Participants were also shown 20 different cards, each with a statement representing a first attempt to operationalize the seven domains (Lewis et al., in review). They were asked to comment on whether they viewed each statement as important to their sexual wellbeing and they were encouraged to write their own statement if they felt the original set did not capture all their priorities. The purpose of using statement cards was twofold; first, to stimulate discussion about the domains in terms of their relevance and priority to participant sexual experiences; and second, to surface views on terminology and phrasing that could assist in operationalizing the domains into candidate items. Fuller methodological details are provided elsewhere (Lewis et al., in review).

Alongside the qualitative work, we reviewed existing relevant questionnaire measures for phrasing and wording. Measures of sexual wellbeing were primarily identified from an existing scoping review (Lorimer et al., Citation2019). We searched for further sexuality-related measures via key sources, such as the Handbook of Sexuality Measures (Fisher et al., Citation2013). We also searched for key measures of constructs related to our hypothesized domains (e.g. resilience). Phrasing of newly created and adapted items was informed by phrasing and language used by qualitative interview participants. Draft wording was refined via multiple discussions within the research team, two informal workshops with colleagues outside of the research team, and an expert surgery review by NatCen Social Research (a research partner in the Natsal study, https://natcen.ac.uk/). This process gave rise to a preliminary 25-item measure.

We undertook cognitive interviews (n = 7; identifying as: 4 women, 3 men; 1 transgender, 6 cisgender; 5 heterosexual, 1 homosexual, 1 pan/bi-sexual; 5 white British; 2 Asian British) to investigate acceptability, comprehension, relevance to experience and question order of the preliminary measure. Participants were recruited by the same professional agency using the same sampling approach as the qualitative interviews. Participants self-completed the 25-item draft version of the Natsal-SW and were then asked about their: understanding of questions; thought process in recalling their answers; views on timeframes and response options; feelings about the sensitivity/intrusiveness of the items; and overall experience of completing the measure. Cognitive testing informed refinements in item wording and order (supplementary file).

Measure Formation and Validation

To develop and validate the Natsal-SW measure, we undertook two web-based surveys: firstly, to assess psychometric properties of items and reduce the item number; and secondly, to externally validate the item-reduced version, ascertain fit of the final model, and assess test–retest reliability (see ).

Web-Based Surveys – Sampling

Our first survey included the 25-item draft measure and aimed for approximately 500 participants. This allowed for 20 participants per item and met Comrey and Lee’s (Citation2013) criteria for “very good” in terms of reducing the risk of erroneous results based on chance item correlations. Participants were members of an internet panel administered by a national market research company (YouGov). YouGov maintain data quality within their panel by validating new members, and by close monitoring of “survey behaviour” to eliminate panelists who give inconsistent responses or display low engagement. Panelists aged 16–59 years were selected randomly within nationally representative quotas on region, age within gender, social grade, and educational level. The survey was closed once quota targets were reached. Data were subsequently weighted by region and age within gender.

The second survey included the reduced-item version of the Natsal-SW plus additional variables to enable external validation. We aimed for a larger sample – approximately 800 participants – due to the examination of external validity which involved analyses of the correlations of our derived scale with other measures described below. As above, participants were aged 16–59 and members of the YouGov panel, quota-sampled to be representative on region, age within gender, social grade, and educational level. Participants completing this second survey were invited to complete a follow-up questionnaire comprising only the Natsal-SW’ around 2 weeks later to examine test–retest reliability. The survey link remained open until 100 completed questionnaires had been received, and the sample was weighted to match the original sample profile. The sample breakdown for the surveys is shown in supplementary Table S1.

Comparison Measures and Variables

There is no “gold-standard” or standard measure of sexual wellbeing so testing for criterion validity was not possible. We sought to assess external-criterion validity of the Natsal-SW (survey two), by including measures that in theory should be associated with sexual wellbeing (supplementary Table S2). These were as follows: depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ2], (Löwe et al., Citation2005)); anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-2] (Plummer et al., Citation2016)); general self-esteem (Rosenberg, Citation1965); general wellbeing (WEMWEBS (Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009)); body image (single-item); sexual depression (sub-domain from Sexuality Scale (Snell & Papini, Citation1989)); sexual esteem (sub-domain from Sexuality Scale (Snell & Papini, Citation1989)); sexual function (Natsal-SF (Mitchell et al., Citation2012)); sexual satisfaction; and sexual distress (single items from the Natsal-SF (Mitchell et al., Citation2012)).

Data Analysis

Item Generation from Qualitative Interviews

The qualitative interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim, anonymized, and entered into a qualitative data management software program (Nvivo v.12). A coding framework, comprising both a priori and inductive codes, was developed iteratively through discussion among analysts and by preliminary reading of transcripts (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). A priori codes were based on domains of sexual wellbeing as conceptualized by the research team, regardless of whether the participants themselves engaged the terminology of that domain (e.g., talk of finding closure following a negative event coded under “forgiveness” regardless of whether that term was employed by participant). These codes formed the basis of a chart summarizing patterns of meaning relating to each domain, with analysis focused on meanings, experiences and terminology to support generation of items. We also aggregated “scores” for each of the 20 statement cards according to whether participants ranked them as “very important”, “quite important” or “not that important” to their sexual wellbeing. A subsequent in-depth analysis – elucidating variation in participant views and experiences of sexual wellbeing – is described elsewhere (Lewis et al., in review).

Item Reduction

Given our aim for a brief measure, candidate items which could be dropped from the measure were identified throughout all stages of the analyses. Data collected in the first online survey were used to assess the properties of the candidate items for inclusion in the measure of sexual wellbeing, and to inform which items could be dropped for further iterations of the measure. Our initial strategy for item reduction was based on work by Lamping et al. (Citation2002) and Lamping et al. (Citation2003), whereby “weak” or uninformative items are identified based on criteria including: >5% non-response; >80% selecting the same answer category; <5% aggregate adjacent endorsement frequencies; and particularly low or high correlations with other items. Further psychometric considerations for dropping items were based on the factor analyses, specifically: evidence of cross loadings (items loading on more than one latent factor); low factor loadings (<0.4); and improvement or lack of detriment to the Confirmatory Factor Analysis model fit when dropped. Decisions to drop items were also based on face-validity/conceptual/acceptability considerations, as follows: our preference for positively worded items and applicability regardless of experience; our aim to ensure all original domains had at least one corresponding item in the final measure while minimizing items reliant on having sex in the last month; a desire to minimize conceptual overlap of items; and consideration of any issues raised in the cognitive interviews relating to the comprehension and relevance of items.

Factor Analysis and Measure Fit

Following the initial refinement of candidate items, we conducted exploratory factor analyses (EFA) on the first survey data to examine the underlying structure of the latent construct of sexual wellbeing, i.e., the presence, number and nature of subscales, and redundancies in items. Informed by this, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were carried out using data from the second survey to test and refine the fit of the measurement model suggested by the EFA. We compared the fit of alternative model structures (first-order factors only; second-order model with a higher order latent factor subsuming first-order factors; and a general specific model in which a global latent factor accounts for variation directly in all items) in selecting the structure of the final measurement model. We examined whether the resultant measure functioned equivalently across key population groups (gender, sexual orientation, age group, and relationship status) using multi-group CFA. The final measurement model was then combined with observed covariates as well as external validation criteria to jointly estimate the external validity of the scale in a full structural model, while adjusting for age, education, gender, and marital status. Lastly, using the sub-sample of participants completing the sexual wellbeing measure on two occasions, we calculated the intra-class correlation (ICC) between test scores to assess the test–retest reliability of the measure.

All latent variable analyses were carried out using Mplus Version 8 (Muthen & Muthen, Citation2017), using the Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance estimator as recommended for categorical and ordinal dependent variables (Beauducel & Herzberg, Citation2006). For missing data, we used the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) method which is automatically incorporated into structural equation models. Model fit was assessed with the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) following Yu’s recommendations on their interpretation (Yu, Citation2002).

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for qualitative fieldwork was granted by LSHTM’s research ethics committee (reference 17046 26/4/2019). Ethical approval for the cognitive interviews, measure development and validation was granted by University of Glasgow MVLS ethics committee (reference 200190039) and LSHTM ethics committee (reference 18018).

Results

Qualitative Findings and Cognitive Interviews

Findings from the qualitative interviews are given in detail elsewhere (Lewis et al., in review). In summary, we found that each of the seven domains aligned with participant accounts, either in terms of their personal experience or understanding of the experience of others. The 20 operationalized statements shown to participants were ranked as very or quite important by > 30 (of 40) participants. Three statements were viewed as “not very important” by > 12 participants. These were: (i) “feeling your sexuality is included and/or valued by others”; (ii) “the people around me share the same values in terms of sexuality,” and (iii) “feeling I have opportunities to have sexual experiences.” The first two were carried forward because those rating them as less important acknowledged that, although less relevant to them personally, they could still be important to others whose sexual behavior and orientation differed from normative expression and practice. The third was less good at capturing such inequalities and we considered “opportunity” as an influence on wellbeing rather than integral to the concept itself. The ideas expressed in all the other statements, as well as participant phrasing, terminology and understanding of terms, were considered alongside relevant items from existing measures. This led to a draft set of 25 items which included at least three items from each of the domains and had a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score of 8.1 (understandable to a US eighth grader). Across the seven cognitive interviews, participants took an average of 3.57 min to complete the measure (range 2.45 to 5.50 min, with one outlier of 9.30 min). The interviews confirmed that terminology had generally been understood and viewed as acceptable. Comments from participants led to minor rewording of 13 items, minor revision to response options on four items and re-ordering of two items.

(column 2) presents the initial 25 candidate items taken forward to the web-based surveys.

Table 1. Overview of candidate items for the measure of sexual wellbeing.

Measure Development

590 participants completed the first survey questionnaire which included the 25 candidate items for the sexual wellbeing measure. At this stage, nine items were dropped from further iterations of the draft measure (see ). EFA on the remaining 16 items indicated that three or four latent factors were necessary to account for the responses to all items (eigenvalues: 6.3, 1.9. 1.4, 1.1).

The second survey was completed by 814 respondents. Based on the results of the EFA, we carried out CFA on a model with three first-order factors. At this stage, a further three items were dropped (see ). Informed by the modification indices, we also allowed the error terms of the variables “In the last month, I felt upset with myself about mistakes I made in my sexual past” and “In the last month, I felt upset with others about things they did to me in my sexual past” to correlate. Due to our aim for a single scale of sexual wellbeing, we estimated a second-order model where a higher-order latent factor subsumes the three first-order factors and a general-specific model in which a global latent factor accounts for variation directly in all items. The general-specific model had the best fit to the data (). This model was also equivalent across genders, age-groups, relationship status, and sexual-orientation groups, as demonstrated by the fit indices for models in which the measurement parameters had been set to function equivalently across these groups ().

Table 2. Fit indices of 13-item CFA models.

The model structure and standardized factor loadings are presented in . The factor loadings on the general Natsal-SW factor capture the common variance between the 13 items, i.e., the shared variance that is due to the underlying level of sexual wellbeing. The three specific factors capture the common variance between their respective items, which is not reflective of sexual wellbeing. All items loaded at an acceptable level (>0.4) on the general Natsal-SW factor and did so in the direction expected, so that a higher score for the Natsal-SW factor reflects higher levels of sexual wellbeing.

Table 3. Final CFA model and standardized factor loadings.

External Validity

The finalized measurement model was extended into structural equation models through which we examined the associations between the newly derived Natsal-SW and external measures theorized to be associated with sexual wellbeing (see ). The Natsal-SW measure was negatively associated with current depression (probit coefficient: −0.384, p < .001), current anxiety (probit coefficient: −0.340, p < .001), reporting sexual distress/worry (probit coefficient: −0.615, p < .001) and sexual depression (standardized coefficient: −0.783, p < .001). We found positive associations between the Natsal-SW and higher sexual functioning (standardized coefficient: 0.924, p <.001), mental wellbeing (WEMWEBS) (standardized coefficient: 0.454, p < .001), self-esteem (standardized coefficient: 0.564, p < .001), sexual esteem (standardized coefficient: 0.563, p < .001), better body image (standardized coefficient: 0.232, p < .001), and sexual satisfaction (probit coefficient: 0.680, p < .001).

Table 4. Associations between Natsal-SW and external variables.

Test Re-Test Reliability

The Natsal-SW general factor demonstrated good test re-test reliability, with an intra-cluster coefficient of 0.78 (95% CI: 0.70, 0.84).

Discussion

The Natsal-SW is a brief measure of sexual wellbeing designed for use in surveys of the general population. The 13-item measure captures the seven domains proposed in theoretical groundwork to establish the construct of sexual wellbeing. The domains reflect a definition of sexual wellbeing defined as: “sexual emotions and cognitions which include feeling safe, respected, comfortable, confident, autonomous, secure, and able to work through change, challenges, and past traumas”. Taken together, the measure represents a summative evaluation of sexual experience and near-future expectation (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). The measure has good fit, functions equivalently across age, gender, sexual orientation and relationship status groups, and has good test–retest reliability. It is associated with related concepts – including general wellbeing, general self-esteem and sexual function – in the expected direction.

To our knowledge, this is the first measure of a concept of sexual wellbeing distinct from the three other “pillars” of sexuality: sexual health, sexual justice, and sexual pleasure (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). In aiming for this distinction, we avoid some of the conceptual confusion inherent in existing measures (Lorimer et al., Citation2019). As a measure designed for population-based surveys, the Natsal-SW is relevant regardless of partnership status or whether one is sexually active, and it focuses on aspects of sexuality amenable to change through public health or clinical intervention. Items in the measure primarily focus on cognition and affect. However, items such as acceptance by others, shame about thoughts and desires, and fear for future sex life, also signify the influence of structural factors (such as repressive laws and norms) on individual sexuality (Lorimer et al., Citation2022). The strength of correlation with sexual satisfaction (0.680) suggested that our measure of sexual wellbeing is related but distinct. We found a stronger correlation with the Natsal-SF measure of sexual function (−0.924). This might be because the Natsal-SF includes items on satisfaction, distress, and quality of sexual relationship, as well as sexual difficulties (Supplmentary Table S2).

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this validation study was rigorous conceptual and qualitative work to ensure the face-validity of the measure (Lewis et al., in review). The wording of each item was debated in multiple rounds of discussion both within and beyond the research team, with additional expert advice from professional survey methodologists (https://natcen.ac.uk/). The use of an internet panel as a proxy for the general population allowed assessment of the measure’s psychometric properties and validity, as well as initial description of measure variability; however, representative population samples are required to establish norms and scoring cutoffs.

Regarding limitations, the measure has been developed and validated on a UK population and its validity in other cultural settings is untested. It relies on concepts such as “sexual identity” that may be less familiar in Global South countries. In attempting to design a measure relevant for a general population across a wide adult age range, the measure may not include items specific to subgroups such as young people, and some sexually minoritized groups. Our sample for analysis aimed to be representative of the general population, consistent with the intended use of the Natsal-SW. This meant that numbers of participants reporting certain minoritized identities were small and in analysis we had to omit groups (those who answered the gender question “in another way” or “prefer not to say”) or collapse categories (non heterosexual orientations). That said, the items were all carefully worded for relevance regardless of gender and sexual orientation, and our qualitative work found domains were perceived as more salient where an individual had experienced adversity in that domain, with salience varying mostly by gender and sexual orientation (Lewis et al., in review). Careful future work will also be required to confirm face validity and measurement equivalence in key groups. For instance, a limitation of our development work is that we did not have participants who identified as asexual and some items in the Natsal-SW may feel less relevant to them. For some, 13 items will feel far too few to capture this multi-dimensional and complex construct, while for others, a 13-item measure will feel impractical for evaluating policies and interventions.

As a final methodological note, our decisions on which items to include in the final measure reflected a balance between statistical and theoretical considerations. The measure was not designed to have separate sub-scales which separately assess each of our seven hypothesized domains. We acknowledge that some items originally designed for one domain may reflect others equally well. An example is “Some of my sexual thoughts and desires make me feel ashamed” which was originally designed to capture sexual comfort but which has face validity for the self-esteem and sexual forgiveness domains.

Applications to Policy and Practice

The measure has a range of applications in research, policy, and practice. Its inclusion in national surveys (such as the Fourth National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles) will provide opportunity to explore how sexual wellbeing relates to other areas of sexual enquiry such as experience of risk behavior, sexual difficulties, violence, and sexually transmitted infections. The Natsal-SW has potential as a monitoring or outcome measure in evaluations of interventions (e.g., trials to evaluate the impacts of sex education, or sexual violence reduction initiatives) and in surveillance and monitoring of national sexual health strategies. It was for this reason that we prioritized domains and items that were amenable to change. We also believe the Natsal-SW will be useful in studies with marginalized, risk or trauma affected groups, such as sex workers and sexual assault survivors. Further, it has potential for comparison across cultural contexts, supporting a better understanding of how legal and socio-cultural environments shape sexual wellbeing at a population level. To fulfil this potential, further validation studies in other settings will be required.

Despite its strong measurement properties, we anticipate some hesitation in its acceptance into the public health measures “tool box.” Some resist the idea that wellbeing itself can be a valid goal of public health (Mitchell et al., Citation2021), citing subjectivity and pointing to the strong influence of social and cultural context in both expectation and experience of wellbeing (Carlisle & Hanlon, Citation2008; Crawshaw, Citation2008). There may be political resistance to giving prominence to sexual wellbeing versus prevention of sexual risks and harms (Epstein & Mamo, Citation2017), and resource constraints to using a multi-dimensional measure within monitoring and evaluation. Future work is required to test the ability of the Natsal-SW to assess modifiable change.

We contend that sexual wellbeing is highly relevant to key functions of public health: it can provide a marker of health equity, particularly for those marginalized because of their sexual health, gender identity or sexual orientation; and it provides a population marker of general wellbeing (Mitchell et al., Citation2021). Measurement of sexual wellbeing also supports a life-course perspective that acknowledges sexuality as an important part of healthy aging (Træen & Villar, Citation2020). In the medium term, we hope that the Natsal-SW will also help shift discourse in public health and psychology fields toward inclusion of sexual wellbeing as a dimension of standardized measures of general wellbeing such as WEMWEBS (Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009; Tennant et al., Citation2007). We hope this brief and valid measure will contribute in a practical way to these efforts.

Conclusion

The 13-item Natsal-SW measure distinguishes sexual wellbeing from sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and sexual health and enables sexual wellbeing to be quantified and understood within and across populations. It is focused on cognitions and affect which reflect both individual circumstances and broader socio-cultural and structural influences on the freedom to achieve sexual wellbeing.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (42.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Natsal-4 is a collaboration between University College London, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University of Glasgow, Örebro University Hospital and NatCen Social Research. We thank the study participants for their participation in this research. The Natsal-4 team supported this development work and includes Co-Principal Investigators (Cath Mercer and Pam Sonnenberg); Co-Investigators (Rob Aldridge, Chris Bonell, Soazig Clifton, Anne Conolly, Andrew Copas, Nigel Field, Jo Gibbs, Wendy Macdowall, Kirstin Mitchell, Gillian Prior, Clare Tanton, Nick Thomson, Magnus Unemo); and Natsal4 Development team members (Raquel Boso Perez, Emily Dema, Emma Fenn, Lily Freeman, Malin Karikoski, Claire Lapham, Ruth Lewis, Dhriti Mandalia, Franziska Marcheselli, Karen J. Maxwell, Dee Menezes, Steph Migchelsen, Laura Oakley, Clarissa Oeser, David Reid, Mary-Clare Ridge, Katharine Sadler, Mari Toomse-Smith).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2278530.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beauducel, A., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 13(2), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carlisle, S., & Hanlon, P. (2008). “Well-being” as a focus for public health? A critique and defence. Critical Public Health, 18(3), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590802277358

- Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (2013). A first course in factor analysis. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315827506

- Crawshaw, P. (2008). Whither wellbeing for public health? Critical Public Health, 18(3), 259–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581590802351757

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056

- Diener, E., Pressman, S. D., Hunter, J., & Delgadillo-Chase, D. (2017). If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 133–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12090

- Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2.i3.4

- Epstein, S., & Mamo, L. (2017). The proliferation of sexual health: Diverse social problems and the legitimation of sexuality. Social Science & Medicine, 188, 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.033

- Fisher, T. D., Davis, C. M., & Yarber, W. L. (2013). Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Routledge.

- Gerymski, R. (2021). Short sexual well-being scale – a cross-sectional validation among transgender and cisgender people. Health Psychology Report, 9(3), 276–287. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2021.102349

- Higgins, J. A., Lands, M., Ufot, M., & McClelland, S. I. (2022). Socioeconomics and erotic inequity: A theoretical overview and narrative review of associations between poverty, socioeconomic conditions, and sexual wellbeing. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(8), 940–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2044990

- Hooghe, M. (2012). Is sexual well-being part of subjective well-being? An empirical analysis of Belgian (Flemish) survey data using an extended well-being scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.551791

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110(3), 837–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Lamping, D. L., Schroter, S., Kurz, X., Kahn, S. R., & Abenhaim, L. (2003). Evaluation of outcomes in chronic venous disorders of the leg: Development of a scientifically rigorous, patient-reported measure of symptoms and quality of life. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 37(2), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2003.152

- Lamping, D. L., Schroter, S., Marquis, P., Marrel, A., Duprat-Lomon, I., & Sagnier, P.-P. (2002). The community-acquired pneumonia symptom questionnaire: A new, patient-based outcome measure to evaluate symptoms in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest, 122(3), 920–929. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.3.920

- Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Glasser, D. B., Kang, J.-H., Wang, T., Levinson, B., Moreira, E. D., Nicolosi, A., & Gingell, C. (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3

- Lewis, R. Bosó Pérez, R. Maxwell, K. J. Reid, D. Macdowall, W. Bonell, C. Fortenberry, J. D. Mercer, C. Sonnenberg, P. & Mitchell, K. R.( Research (under review). Conceptualising sexual wellbeing: A qualitative investigation of a conceptual framework to inform development of a measure. The Journal of Sex Research.

- Lorimer, K., DeAmicis, L., Dalrymple, J., Frankis, J., Jackson, L., Lorgelly, P., McMillan, L., & Ross, J. (2019). A rapid review of sexual wellbeing definitions and measures: Should we now include sexual wellbeing freedom? The Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1635565

- Lorimer, K., Greco, G., & Lorgelly, P. (2022). A new sexual wellbeing paradigm grounded in capability approach concepts of human flourishing and social justice. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(10), 1402–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2022.2158236

- Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006

- McClelland, S. I. (2010). Intimate justice: A critical analysis of sexual satisfaction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(9), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00293.x

- McLinden, D. (2017). And then the internet happened: Thoughts on the future of concept mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.10.009

- Mitchell, K. R., Lewis, R., O’Sullivan, L. F., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2021). What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? The Lancet Public Health, 6(8), e608–e613. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00099-2

- Mitchell, K. R., Ploubidis, G. B., Datta, J., & Wellings, K. (2012). The Natsal-SF: A validated measure of sexual function for use in community surveys. European Journal of Epidemiology, 27(6), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-012-9697-3

- Muise, A., Preyde, M., Maitland, S. B., & Milhausen, R. R. (2010). Sexual identity and sexual well-being in female heterosexual university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 915–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9492-8

- Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus version 8 user’s guide. Muthen & Muthen.

- Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (1993). The quality of life. World Institute for Development Economics Research, & Oxford University Press. https://go.exlibris.link/dxMTCq25

- Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Rosen, N. O., Muise, A., Bergeron, S., Delisle, I., & Baxter, M. L. (2015). Daily associations between partner responses and sexual and relationship satisfaction in couples coping with provoked vestibulodynia. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(4), 1028–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12840

- Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A new understanding of happiness and well-being - and how to achieve them. Nicholas Brealey.

- Snell, W. E., & Papini, D. R. (1989). The Sexuality Scale: An instrument to measure sexual‐esteem, sexual‐depression, and sexual‐preoccupation. The Journal of Sex Research, 26(2), 256–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498909551510

- Stephenson, K. R., & Meston, C. M. (2015). The conditional importance of sex: Exploring the association between sexual well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2013.811450

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(15), 15–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

- Štulhofer, A., Jurin, T., Graham, C., Enzlin, P., & Træen, B. (2019). Sexual well-being in older men and women: Construction and validation of a multi-dimensional measure in four European countries. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(7), 2329–2350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0049-1

- Štulhofer, A., Jurin, T., Graham, C., Janssen, E., & Træen, B. (2020). Emotional intimacy and sexual well-being in aging European couples: A cross-cultural mediation analysis. European Journal of Ageing, 17(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00509-x

- Sundgren, M., Damiris, I., Stallman, H., Kannis-Dymand, L., Millear, P., Mason, J., Wood, A., & Allen, A. (2022). Investigating psychometric measures of sexual wellbeing: A systematic review. Sexual & Relationship Therapy, (ahead-of-print), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2022.2033967

- Syme, M. L., Cohn, T. J., Stoffregen, S., Kaempfe, H., & Schippers, D. (2019). “At my age … ”: Defining sexual wellness in mid- and later life. Journal of Sex Research, 56(7), 832–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1456510

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

- Træen, B., & Schaller, S. (2010). Subjective sexual well-being in a web sample of heterosexual Norwegians. International Journal of Sexual Health, 22(3), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611003776087

- Træen, B., & Villar, F. (2020). Sexual well-being is part of aging well. European Journal of Ageing, 17(2), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-020-00551-0

- Willen, S. S., Williamson, A. F., Walsh, C. C., Hyman, M., & Tootle, W. (2022). Rethinking flourishing: Critical insights and qualitative perspectives from the U.S. Midwest. SSM - Mental Health, 2, 100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100057

- World Health Organization. (2004). Promoting mental health: Concepts, emerging evidence, practice: Summary report. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940

- Yu, C.-Y. (2002). Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes [ University of California]. https://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudissertation.pdf