ABSTRACT

Sex toys are easily accessible in many countries in the Western world. Yet, cross-country studies on sex toy ownership and use and their association with relationship, sexual, and life satisfaction are rare. Using a cross-country convenience sample of 11,944 respondents from six European countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, UK), we investigated the rate and factors linked to sex toy ownership and use and their associations with sexual, relationship, and life satisfaction. Data were collected in May and June 2022 through respondent panels by Cint, a market research software platform. Participants received an e-mail invitation for the study and completed an online self-report survey. We found that more than half of respondents owned or had owned a sex toy, with the most common sex toys owned being dildos and vibrators, followed by handcuffs, penis rings, and anal sex toys. Across countries, the majority of sex toy owners reporting using these either alone or with a steady partner (55–65%) and a minority with casual partners (10–15%). Controlling for socio-demographics, parental status, sexual orientation, number of sex partners, and relationship status and length, we found that sex toy ownership and use were significantly associated with higher sexual and life satisfaction, while higher relationship satisfaction was only significantly associated with currently owning a sex toy (but not number of sex toys) and frequency of use with a partner (but not alone). Across results, we generally found little cross-country variation.

Similar to most topics related to sex, the use of sex toys has historically been somewhat controversial, including the concept of engaging in sexual activities for sexual pleasure, providing pleasure without the need of a partner, and the ability to experience sexual pleasure without the need for penetration (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Meiller & Hargons, Citation2019). Some of this controversy may stem from both historical cultural norms and morals and sexual schemas about what constitutes good sex, how to most appropriately reach orgasm or have sex in a relationship (i.e., often through coitus) and the notion of orgasms as the end goal for sexual (relational) activities to be achieved without the aid of sex toys (Crewe & Martin, Citation2017; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). Furthermore, the widespread heteronormative perspective on sexuality, which binds individuals to stereotypical gender roles and behaviors, may not include the use of sex toys or only certain kinds of normative appropriate sex toys (Ayalon et al., Citation2019). Lastly, fear of individuals choosing solo sex over partnered sex, where the improved technology (e.g., sex dolls or robots) becomes a substitute for or threat to a sexual partner, has more recently been voiced (Fahs & Swank, Citation2013; Queen, Citation2013). Nonetheless, sex toys have also been seen as a way to enhance individual and relational sexual pleasure, satisfaction, sexual self-acknowledgment, and sexual health (Piha et al., Citation2020; Queen, Citation2013; Schick et al., Citation2015) or as a symbol for feminist ideals about sexual liberation and equity, new sexual possibilities and sexual self-discovery (Mayr, Citation2022; Nixon & Marco Scarcelli, Citation2022).

Sex Toys Today

Sex toys are not modern-day appliances but have been in use for centuries (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Miranda et al., Citation2019). As seen from the sales and user figures of major sex toy producers and retailers, their purchase and use across different populations, genders, and age groups is widespread and appears to be increasing (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Træen et al., Citation2021). Coming in many types, shapes, colors, sizes, and textures, sex toys are well-known across genders and sexual orientations throughout the Western world (Richters et al., Citation2003, Citation2014; Schick et al., Citation2012). The current labeling system for sex toys differs between studies, where specific categories may include a different set of products depending on the investigation’s focus. Sex toys are often defined as physical products designed with the purpose of enhancing sexual pleasure by improving the nature and quality of the sexual experience through stimulation of different body parts (e.g., genitalia/anus/erogenous zones), with the product often applied directly to the specific body part (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). Alongside, sexual aids are often used to refer to a wider set of products, including BDSM equipment and tools, pornography, erotic lingerie and costumes, and lubricants and pharmaceutical remedies, with the primary purpose of increasing sexual arousal and/or acting as a precursor for sexual activities (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). The term ”sexual aid” is often used in clinical and medical settings, where the purpose of such products is to cope with or treat sexual problems or dysfunctions (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020) in contrast to sex toys, which may more often be used to refer to products that aim to provide sexual pleasure and enhancement merely for hedonistic purposes. For the purpose of this study, the term sex toy is used, and it will refer to all material products used by individuals for sexual pleasure enhancement during solo or relational sexual activities (see for reference). Many countries ban the purchase, possession, and use of sex toys for various religious, cultural, political, or ideological reasons and the vast majority of studies on sex toys have been conducted in Western countries, which are less or nonrestrictive in their juridical and societal approach to sex toys (Council, Citation2020; Kwakye, Citation2020).

Table 1. Survey response rates across countries.

Table 2. Demographics breakdown (in percent) of the sample, by country and for the full sample.

Table 3. Frequencies (in percent) of sex toy ownership and use of sex toys, by country.

Sex Toys in Literature

Research on sex toy ownership, rate of sex toy use, and the effects of their use is relatively scarce and sex toy ownership and sex toy use are not necessarily tied to one another directly. One can own a sex toy (sex toy ownership) without using it (sex toy use) or use it without owning it, such as in the case of a couple using sex toys together when only one of the two have purchased and formally owns them. In addition, sex toy ownership can also be further broken down into ownership through purchase or through gifting. However, the literature rarely specifies between the nuances of sex toy ownership and use when investigating the rate of the two, and often only investigates one without the other. In the empirical part of this study, we do differentiate results on this basis; however, in the literature review of frequency rates below, we do not do so due to the scarcity of studies and huge overlap in frequency rates of sex toy ownership and use.

Broadly speaking, rates of sex toy use suggest large differences in use depending on sample composition, study design, study definition of sex toys, time frame, and nationality/country of study (Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Kwakye, Citation2020; Miranda et al., Citation2019; Richters et al., Citation2014; Schick et al., Citation2012). For example, rates of sex toy use among women range from 21% to 73% and among men 15 to 76% (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Kwakye, Citation2020; Miranda et al., Citation2019; Richters et al., Citation2014; Schick et al., Citation2012).

In reference to specific rates of sex toy use, an Australian study on health and relationships using a representative population-based survey and computer-assisted telephone interviews with 20,094 men and women aged 16–69 years (ASHR, Citation2022) found that 15% of men and 21% of women had used sex toys in the past year (Richters et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the study found that 14% of men and 16% of women reported having used sex toys with a sexual partner in the last year (Richters et al., Citation2014). Much higher rates of use were reported by an online cross-sectional survey study carried out in Germany, investigating sex toy use among 1,723 heterosexual-identifying women and men aged 18–69 (non-probability sample) (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). The study reported that 52% of the population had ever used a sex toy for partnered sex and 45% for solo sex (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). Similar rates of use were reported in a Canadian cross-sectional online survey study investigating women’s vulvovaginal health and hygiene practices involving 1,408 women aged 18–81. This study reported a rate of sex toy use of 52% (Wood et al., Citation2017). Further, an annual report by an Austrian adult store showed that 63% out of 15,104 men and women used vibrators in their sexual activities (Mayr, Citation2021). In a Norwegian population survey study investigating sexual intercourse activities and activities associated with sexual interaction among Norwegian men and women aged 18–89 randomly recruited from Kantar’s Gallup Panel (which is representative of the Norwegian Internet population), it was found that 11% of the sample reported using sex toys during their most recent intercourse (sexual encounter with a partner) (Træen et al., Citation2021). As illustrated by these results, the rates of use vary greatly from study to study depending on what products are investigated and considered sex toys and the time frame studied.

Factors Associated with Sex Toy Use

In terms of factors associated with sex toy use, the research literature has predominantly focused on gender, relationship status, age, educational level, and sexual orientation. For gender, research provides scarce and discordant results as these depend heavily on the sexual orientation of the men and women investigated and the sexual context within which they use sex toys. Among heterosexual men and women, sex toy use during masturbation largely differs, with women using sex toys significantly more than men (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Reece et al., Citation2009) while no significant differences between heterosexual men and women have been found in partnered sex toy use (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Reece et al., Citation2009). However, some gender differences have been found when considering the type of sex toys used and the context of use (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Miranda et al., Citation2019). For example, a national online survey investigating sex toy use among German adults found no overall difference between men and women in regard to the type of sex toys used when these were not gender specific (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). Furthermore, it was found that both men and women used sex toys that were originally designed as gender-specific toys, such as vibrators for women and masturbators for men (toys for the stimulation of the penis and testicles) (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Miranda et al., Citation2019). However, in this study significant gender differences emerged when context of use and sexual user characteristics were factored in. For example, it was found that vagina and vulva stimulators were used by a majority of sex toy-experienced women (i.e., individuals who use sex toys vs. individuals who do not) for solo sex (72%) compared to men (31%) in the last 12 months (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020). However, for partnered sex, these differences were reversed as a significantly higher number of sex toy-experienced men (76%) than women (55%) reported using vagina and vulva stimulators during sex in the last 12 months (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020).

When rates of sex toy use are investigated among self-identified bisexual and homosexual men and women and compared to individuals identifying as heterosexual significant differences in use emerge. Here, the research generally suggests that the highest rates of sex toy use are among bisexual and homosexual individuals. Specifically, over 75% of women who have sex with women and bisexual women and 19–36% of men who have sex with men and bisexual men report vibrator use (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021). Moreover, bisexually-identifying women report greater use of sex toys during intercourse with women than with men over the last 30 days, specifically: vibrator use (25% vs. 12%), non-vibrating dildo (16.5% vs. 6%), non-vibrating double dildo (6% vs. 1%); non-vibrating strap-on (14% vs. 3%), butt plug (4% vs. 3%), and anal beads (2% vs. 1.5%) (Schick et al., Citation2012).

When it comes to the association between sex toy use, on the one hand, and relationship status, age, and educational level, on the other, the results are equivocal (Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Schick et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2017). Some studies suggest that being in a relationship, especially cohabiting, and younger age are positively associated with and predictive of higher sex toy use (e.g. Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Schick et al., Citation2011; Træen et al., Citation2021). Other studies report higher frequency of sex toy use among older age groups, possibly due to younger individuals having less access to or income for such products (Schick et al., Citation2011). While data on educational level are routinely collected, its association with sex toys use is rarely investigated. Schick et al. (Citation2011) found no significant association between educational level and rate of sex toy use, while two studies (one conducted in Canada and the other in the US) reported a positive association between higher educational level and higher sex toy use (Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Wood et al., Citation2017).

Effects of Sex Toy Use

Although scarce, research on the effects of sex toy use has found that individuals who use sex toys predominantly perceive positive effects of their sex toy use (Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Herbenick et al., Citation2009) and that sex toy use is associated with increased sexual pleasure, reduced pain, and enhanced fun and comfort during sex (Fahs & Swank, Citation2013; Schick et al., Citation2015). The use of sex toys is also associated with increased sexual experimentation and expression and improved connection with a partner (Piha et al., Citation2020). Additionally, sex toy use is associated with decreased stress, improved sexual performance, and improved treatment for individuals experiencing sexual dysfunctions (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020; Schick et al., Citation2011).

In relation to women’s health, sex toy use has been associated with increased sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, absence of pain, overall improved sexual functioning, and increased sexual satisfaction (Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Richters et al., Citation2006) as well as sexual pleasure enhancement and recreation (Herbenick et al., Citation2010). Similarly, for men, perceived effects of sex toys are also mostly positive (Reece et al., Citation2009; Satinsky et al., Citation2011). For instance, a US study of sex toy use among 26,257 HIV-positive men who have sex with men found that participants mostly used sex toys out of curiosity, expecting them to be fun, and with the intent of pursuing sexual pleasure and increasing subjective sexual satisfaction (Satinsky et al., Citation2011).

Current Study

In the current study, we sought to extend previous research on sex toys in at least three important ways using a large sample of adults in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, and the UK. First, across these European countries, we investigated rates of sex toy ownership and use and a comprehensive array of predictors of such ownership and use. Second, we examine whether sex toy use was associated with sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction. Third, we assessed whether there were any country differences in these rates and associations. Combined, this allowed for a more comprehensive cross-country investigation of sex toy use, and an exploration of the associations such use may have with sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction, controlling for core socio-demographic variables.

Specifically, the study investigated the following two research questions:

R1.

What are the rates of sex toy ownership and use in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, France, and the UK and what predicts such use?

R2.

Is sex toy ownership and use associated with a) sexual satisfaction, b) relationship satisfaction, and c) life satisfaction in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, France, and the UK?

Method

Procedure

The data were collected by Cint, a globally leading market research software platform, on behalf of Radius, a Danish market research firm, and Sinful ApS, an online international sex toy company based in Denmark. Sinful commissioned Radius to develop the survey and Radius commissioned Cint to collect the data. Cint collaborates with several opt-in respondent panels that recruit participants for surveys. Cint’s panel and sample source partners include market research agencies, media owners, (digital and traditional) publishers, nonprofits, and companies with access to large-scale web traffic. Cint’s panel partners source participants/panelists through a variety of methods to help build diverse, representative, and engaged panel communities. These include e-mail recruitment through a panel owner’s newsletters, specific invitations sent to a panel owner’s database, e-mail recruitment using a permission-based database, telephone-based recruitment, and face-to-face (F2F) based recruitment.

The data were collected in six countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, and the UK) simultaneously, during the period from May 17, 2022 to June 8, 2022; participation was done online. Please see for response rates across countries. The invited sample was selected based on demographics quotas; specifically, interlocked quotas were set up to ensure that the invited sample reflected the population of each country in terms of gender, age, and region of country. Invited participants received an e-mail invitation that used the “brand” of the specific panel of which they were a member. In the e-mail, the participants were informed about the details for the survey, including where to access the full disclosure of incentive terms and conditions applying to the project, the opportunity to unsubscribe or opt-out, and the privacy policy or statement. Furthermore, participants were presented with a welcome statement in the survey, explaining the topic of the survey and that they had the option to not answer questions that they did not feel comfortable responding to. The funder of the survey (Sinful ApS) was not mentioned to the participants as this could have affected their answers. Participants were compensated for survey participation according to the policy of the panel of which they were a member; typically, participants receive points that can be converted to products or services over time.

The researchers at the University of Copenhagen received access to the anonymous data after its collection. The Danish data protections agency provided approval for data processing by the researchers at the University of Copenhagen. In total, 13,173 clicked on the survey link and 12,071 people completed the survey across the six countries (see also ). The data was cleaned prior to being transferred to Sinful ApS, who subsequently sent it to the researchers at the University of Copenhagen. The original cleaning process concerned the removal of respondents that were “speeders” and who “straightlined” through the survey. The data file received by the University of Copenhagen contained 12,044 respondents. For the current article, we elected to focus on those that reported being between the ages of 18 and 80.Footnote1 Subsequently, were focus here on the responses from 11,944 people.

Measures

The questions in the survey were developed specifically for this study, but some questions were inspired by previous research in the field, specifically, the large Danish Population survey study on sexuality conducted in 2018–19 called “Project Sexus” (see https://www.projektsexus.dk/). The survey, called the Sindex, was developed by a working group with representatives from Sinful ApS (their Head of Brand Management, Marketing Director, Art Director, and a Co-founder), and representatives from Radius (a Danish market research firm). The representatives from Radius wrote the first draft of the items, and these were then edited in working group meetings with all representatives. Items were written in English and then translated to the other languages by members of staff at Sinful ApS (Norwegian and French) and by freelance translators (Danish [but proofread by a native speaking employee at Sinful ApS], Finnish, and Swedish). Back-translation techniques were not employed.

Gender

Gender was assessed with an item that asked participants to indicate if they identified as “man,” “woman,” or “other.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options. For analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded “woman” were coded as 1, those that responded “men” were coded as 0, and those that responded “other” were coded as missing (.60% of the total sample).

Age

Age was assessed with an item that asked participants to indicate their age in years with a whole number.

Educational Level

Educational level was assessed with a single question that asked participants what their highest level of completed education was. Response options were country-specific and were therefore recoded to represent “short education” (e.g., primary school, high school, business high school, vocational education; coded as 0), “medium-length education” (e.g., medium-cycle tertiary education, bachelor’s degree; coded as 1) and “long education” (e.g., Master’s and PhD degrees; coded as 2).

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation was assessed with an item that asked participants to indicate their sexual orientation, with the following response options: “Heterosexual,” “Homosexual,” “Bisexual,” “Asexual,” “Other,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options. For analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded “Other” or “I do not know/I do not want to answer” were coded as missing (7.35% of the total sample).

Current Relationship Status

Current relationship status was assessed with a single item that had the following response options: “Single (not dating),” “Single (dating),” “In a relationship (not living together),” “In a relationship (living together),”Footnote2 “Other,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options. For analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded “Other” or “I do not know/I do not want to answer” were coded as missing (2.72% of the total sample).

Length of the Relationship

For respondents in relationships, length of the relationship was assessed with a single item that asked how long they had been in their current relationship, with the following response options: “Less than one year,” “1–3 years,” “4–6 years,” “7–9 years,” “10–12 years,” “13–15 years,” “16–18 years,” “19–20 years,” “More than 20 years,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options; for analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded “I do not know/I do not want to answer” were coded as missing (1.61% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate greater length of the relationship.

Parental Status

Parental status was assessed with a single item asking if the participant had any children, with the following response options: “Yes, they still live at home,” “Yes, but they have moved out/grown up,” and “No.”

Number of Lifetime Sexual Partners

Number of lifetime sexual partners was assessed with a single item that asked how many sexual partners the participant would estimate that they have had in total in their life, with the following response options: “0,” “1–5,” “6–10,” “11–15,” “16–20,” “21–25,” “26–30,” “31–40,” “40–50,” “More than 50,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options; for analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded “I do not know/I do not want to answer” were coded as missing (8.53% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate a higher number of lifetime sexual partners. A mistake by the developers was made concerning the number “40” which was included in two response categories. The way the responses were set up did not allow the authors to correct this mistake.

Sex Toy Ownership

Participants first responded to the following question: “Do you own any sex toys? For example, a vibrator, BDSM-equipment, a penis ring, or a dildo,” to which they could answer “Yes,” “No, but I have owned sex toys in the past,” “No, I have never owned any sex toys” or “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” For descriptive purposes, we retained all response options; for analytic purposes, we recoded the responses, such that those that responded yes were coded as 1 and those that responded no were coded as 0, and those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (6.9% of the total sample).

Those that responded in the affirmative regarding sex toy ownership were subsequently presented with a question that asked them to indicate how many sex toys they approximately owned (a numeric response that ranged from 1 to 100). We elected to cap the variable at 30, such that those that responded with a number greater than 30 were coded as 30. This rescoring applied to less than 2% of the responses and was done to minimize the influence of outliers in the analyses.

Participants were also asked to indicate which sex toys they owned, from the following list: “Dildo,” “Vibrator,” “Penis ring,” “Whip or paddles,” “Anal sex toys,” “Masturbation products for men,” “BDSM-toys,” “Strap-on,” “Handcuffs,” and “Pelvic floor balls.” Multiple responses were permitted; the participant could also indicate “other” (no text entry option was offered) or that they did not know or want to answer.

Interpersonal Context of Sex Toy Use and Frequency of Use

Participants were asked to indicate with whom they used sex toys, with the following response options: “I use them alone,” “I use them with my partner, whom I am in a steady relationship with,” “I use them with partners I am not in a steady relationship with,” “Other,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Multiple responses were permitted. Participants were also asked to indicate how frequently they used them using the following response options: “Every time I am intimate with myself,” “Most times I am intimate with myself,” “Sometimes when I am intimate with myself,” “Rarely when I am intimate with myself,” “Never when I am intimate with myself,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (3.7% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate higher frequency.

Similarly, those that indicated that they were in steady relationships and owned sex toys were asked how frequently they used sex toys with their partner, with the following response options: “Every time we have sex,” “Most times when we have sex,” “Sometimes when we have sex,” “Rarely when we have sex,” “Never,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (1.4% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate higher frequency.

Sexual Satisfaction

Sexual satisfaction was assessed with a single item that asked participants to indicate how satisfied they were with their current sex life in general, with the following response options: “Very satisfied,” “Mostly satisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Mostly dissatisfied,” “Very dissatisfied,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (5.5% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate greater sexual satisfaction.

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed with a single item that asked participants to indicate how satisfied they were with their life in general at the moment, with the following response options: “Very satisfied,” “Satisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Dissatisfied,” “Very dissatisfied,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (3.1% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate greater life satisfaction.

Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was assessed with a single item that asked participants to indicate how satisfied they were overall with their current relationship, with the following response options: “Extremely satisfied,” “Satisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Dissatisfied,” “Extremely dissatisfied,” and “I do not know/I do not want to answer.” Those that responded that they did not know or want to answer were coded as missing (2.1% of the total sample). Higher scores indicate greater relationship satisfaction.

Plan of AnalysisFootnote3

All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4, using list-wise deletion; the raw data were used and no weights were applied. To examine the first research question, we conducted a series of chi-square analyses, to see if there were country differences in ownership of (any) sex toys and specific sex toys, as well as differences in with whom the toy(s) were used. These analyses were followed by a logistic regression seeking to examine whether gender, age, sexual orientation, educational level, parent status, number of sexual partners and relationship status predicted sex toy ownership (yes/no). All respondents were included in these analyses. We then conducted a negative binomial regression that examined whether there were country differences in terms of the number of sex toys owned, as well as whether gender, age, sexual orientation, educational level, parent status, number of sexual partners and relationship status predicted the number of sex toys owned. We conducted a negative binomial regression, as the number of sex toys was a positively skewed, over-dispersed, count variable. We then conducted linear regressions to examine whether the frequency of use of sex toys (whether alone or partnered) was predicted by these same variables. Relationship length was included as a predictor of the frequency of use of sex toys with a partner only.

To examine the second research question, we conducted a series of linear regressions, predicting sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction. We conducted the regressions in multiple steps that included the following variables in step:

demographics predictors (gender, age, sexual orientation, educational level, parent status, number of sexual partners and relationship status)

demographics predictors, and sex toy ownership (yes/not)

demographics predictors and number of sex toys

demographics predictors, number of sex toys, and frequency of use of sex toys alone

demographics predictors, number of sex toys, and frequency of use of sex toys with a steady partner

After examining the main effect of each of the sex toy variables (sex toy ownership, number of sex toys, frequency of use alone and frequency of use with a partner), we added in interactions between these variables and country of assessment in a similar sequence, to see if there were differences in the associations between the sex toy ownership and use predictors and the outcomes by country.

In all regression analyses, age, lifetime number of sexual partners and relationship length were entered as continuous variables, while gender, sexual orientation, educational level, parent status, relationship status, and country of assessment were entered as categorical predictors. Initial assessment of the significance of each predictor was done via Type 3 tests of effect (a type of variable-specific omnibus test, similar to Type 3 sums of squares in ANOVAS). In the case of statistically significant categorical variables, we conducted follow-up tests to specify between which categories there were significant differences. This was accomplished using the LSMEANS statement in SAS; as there were numerous comparisons made (for each variable, we did all pairwise comparisons), we elected to employ a Tukey adjustment to the p-values for each follow-up comparison.

Results

Participants’ Demographics Make-Up

provides a breakdown of the demographic make-up of the sample by country, as well as overall. In general, the sample had a mean age of 42 years, and roughly half the sample was male and of shorter education. The majority of participants reported identifying as heterosexual, being in a relationship and living with their partner. The majority of the sample reported having children and 36% reported having children still living at home. Few (3.4%) reported not having ever had a sexual partner (see ).

Sex Toys Ownership

provides an overview of the frequency of sex toy ownership and use by country. Although many between-country similarities emerged, there were also some noticeable differences. For example, a greater proportion of French respondents indicated not having ever owned a sex toy or not currently owning one, compared to participants from the other countries. Among participants that indicated owning sex toys, the most frequently owned sex toys were dildos and vibrators (roughly 50–60% of the respondents) followed by penis rings, handcuffs, and anal sex toys (roughly 20–25% of the respondents), though respondents from France and the UK indicated owning dildos to a lesser extent than those from other countries. In contrast, more UK respondents than in any other countries indicated owning a vibrator (app. 80%). There were no between country differences in ownership of anal sex toys, BDSM-related toys, strap-ons, and handcuffs.

Predictors of Sex Toy Ownership

The logistic regression examining predictors of ownership of sex toys () correctly classified 67% of the data (i.e., sex toy ownership). Women, younger people, and respondents with a greater number of lifetime sexual partners were more likely to report owning a sex toy (ORgender- male = .522; ORolder age = 0.980: ORsex lifetime partners = 1.161). Those identifying as heterosexual did not differ from those identifying as homosexual in terms of their likelihood of owning sex toys (OR = .957). Those identifying as bisexual were more likely than those identifying as homosexual (OR = 1.435) and those identifying as heterosexual (OR = 1.501) to own a sex toy, while those identifying as asexual were less likely than those identifying as homosexual (OR = .413), bisexual (OR = .288), or heterosexual (OR = .431) to own a sex toy. Respondents with children no longer living at home and non-parents did not differ (OR = 1.000), while respondents with children living at home were more likely to own a sex toy (OR = 1.313), as compared to the two other groups. Respondents in relationships (whether living together or not) and those that were single and dating did not differ in terms of the likelihood of owning a sex toy (ORs = .945–1.111) and these groups were all more likely to own a sex toy as compared to those that were single and not dating (ORs = 1.373–1.525). There were no differences based on educational level. With respect to country of assessment, respondents from France were less likely than respondents from any other countries to own a sex toy (OR = .601–.678), while there were no differences between respondents in the remaining countries.

Table 4. Predictors of ownership of sex toys, number of sex toys, and frequency of use alone and with a partner: type 3 analysis of effects.

Predictors of Number of Sex Toys

The negative binomial regression examining predictors of the number of sex toys owned () suggested that men reported owning more sex toys, relative to women (b = .115, p < .001). A greater number of lifetime sexual partners were associated with owning more sex toys (b = .063, p < .001), while older age was associated with owning fewer sex toys (b = −.012, p < .001). Those identifying as heterosexual reported owning fewer sex toys (M = 1.286) than those identifying as homosexual (M = 1.436, p = .041), bisexual (M = 1.544, p < .001), or asexual (M = 1.710, p = .002). Those identifying as homosexual, bisexual, and asexual did not differ in terms of the number of sex toys (ps = .135–.510). Those that did not have children reported owning fewer sex toys (M = 1.400) than those with children at home (M = 1.535, p < .001) and those with children no longer living at home (M = 1.546, p = .001). Parents with children at home did not differ from parents with children not at home (p = .953).

Those in relationships (whether living together or not; Mliving = 1.577 and Mnot living = 1.494) and those that were single and dating (M = 1.538) did not differ in terms of the number of sex toys owned (ps = .227–.851). However, all of these groups were more likely to own a sex toy as compared to those that were single and not dating (M = 1.366, p-values from <.001 to .044). There were no differences in the number of sex toys owned based on educational level. Respondents from France reported owning fewer sex toys (MFR = 1.1969) than those from all other countries (MDK = 1.683, MSW = 1.547, MNO = 1.513, MFI = 1.619, MUK = 1.404, all p-values < .001), while respondents from Denmark reported owning more sex toys than all other countries (p-values from <.001 to .029), except for Finland (p = .693).

Predictors of Frequency of Use of Sex Toys Alone

The linear regression predicting the frequency of use of sex toys alone accounted for 17% of the total variance (see also ). Younger people (bolder age = −0.026, p < .001) and women (bgender - male = −.707, p < .001) reported using them more frequently. Respondents identifying as heterosexual (M = 3.323) reported using sex toys alone less frequently than did respondents identifying as bisexual (M = 3.561, p = .001) and respondents identifying as homosexual (M = 3.632, p = .004). Respondents that identified as asexual (M = 3.418) did not differ from those of other sexual orientations (ps = .740–.961) and respondents identifying as homosexual did not differ from those identifying as bisexual (p = .907). Respondents with longer educations (M = 3.592) reported using sex toys alone more frequently than did respondents with shorter educations (M = 3.415), while there were no significant differences involving medium length educations (M = 3.444, p’s = .081–.806). Respondents that did not have children reported using sex toys alone less frequently (M = 3.300) than respondents with children at home (M = 3.507, p < .001) and respondents with children no longer living at home (M = 3.644, p < .001). Parents with children at home did not differ from parents with children not at home (p = .065). Respondents in relationships and living with their partner reported using sex toys alone less frequently (M = 3.107) than did respondents in relationships and not living together (M = 3.496, p < .001), those single and dating (M = 3.586, p < .001), and those single and not dating (M = 3.746, p < .001). Respondents in relationship but not living together with their partner used sex toys alone less frequently than respondents who were single and not dating (p = .006) but did not differ from those single and dating (p = .727). Respondents identifying as single and dating did not differ from respondents identifying as single and not dating (p = .135) in their use of sex toys alone. The only significant differences for country were that respondents from the UK reported using sex toys alone less frequently (M = 3.305) than respondents from Sweden (M = 3.554, p = .005), Norway (M = 3.571, p = .002), Finland (M = 3.543, p = .007), and France (M = 3.520, p = .044), but not Denmark (M = 3.410, p = .665).

Predictors of Frequency of Use of Sex Toys with the Partner

The linear regression predicting the frequency of use of sex toys with a steady partner accounted for 7% of the total variance and the results can be found in . Older people (b = −0.012, p < .001) and respondents in longer relationships (b = −0.036, p = .001) reported using them less frequently. Men (relative to women; b = 0.422, p < .001) reported using them more frequently with a partner. There was only one significant difference for sexual orientation, such that respondents identifying as heterosexual (M = 2.931) reported using sex toys with a partner less frequently than respondents identifying as homosexual (M = 3.198, p = .046). Respondents that did not have children reported using sex toys with a partner less frequently (M = 2.714) than respondents with children at home (M = 3.035, p < .001) and respondents with children no longer living at home (M = 3.148, p < .001); parents with children at home did not differ from parents with children not at home (p = .176). There were no significant differences in terms of educational level, number of lifetime sexual partners, nor relationship status. The only significant difference for country of assessment was that respondents from Sweden reported using sex toys with their partner more frequently (M = 3.100) than respondents from Denmark (M = 2.870, p = .034).

Sexual Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Relationship Satisfaction as Outcomes of Sex Toy Ownership and Use

There were several notable main effects of both the demographics and the sex toy-related variables (see ); the proportion of variance explained by inclusion of the variables in step 1 was roughly 9% for sexual satisfaction, 7% for life satisfaction, and 5% for relationship satisfaction. This proportion of variance explained increased significantly when variables related to the frequency of use of sex toys were included. For instance, when the number of sex toys and the frequency of partnered use were included, the proportion of variance explained rose to 15% for sexual satisfaction, 9% for life satisfaction, and 15% for relationship satisfaction. As the results for the demographic variables are extensive, we elected to focus here on country and the sex toy-related predictors. Please see the supplemental file for a breakdown of the effects of the demographic variables.

Table 5. Predictors of sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: type 3 analysis of effects.

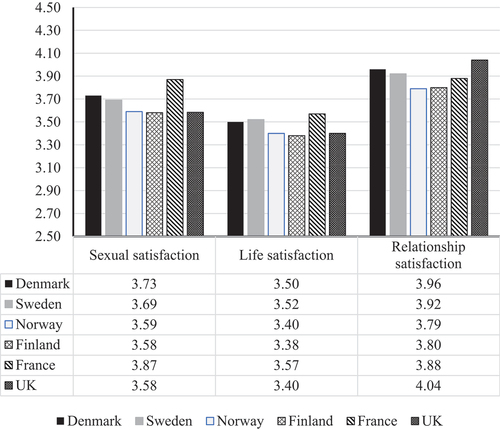

There were significant differences in general level of sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction based on country (see ). Respondents from France reported higher sexual satisfaction than all other countries (all p-values < .01). Respondents from Denmark reported higher sexual satisfaction as compared to respondents from Norway (p = .007), Finland (p = .002), and the UK (p = .001), but not respondents from Sweden (p = .920). Respondents from Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the UK did not differ from each other (ps = .050 to 1.00).

Figure 1. Average levels of sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction, by country.

The pattern of findings was less consistent for life satisfaction and relationship satisfaction. People from France reported higher life satisfaction as compared to people from Finland, Norway, and the UK (ps < .001), but not Denmark and Sweden (p > .340). Respondents from Finland and the UK reported lower life satisfaction as compared to respondents from Denmark (pFI = .008; pUK = .045) and Sweden (pFI = .002; pUK = .010). Respondents from Finland did not differ from those from the UK (p = .993) and respondents from Denmark did not differ from those from Sweden (p = .996). Respondents from Norway reported lower life satisfaction as compared to respondents from Sweden (p < .024).

Lastly, respondents from the UK reported higher satisfaction as compared to respondents from Sweden, Norway, Finland, and France (all p-values = .021–.001) but did not differ from respondents from Denmark (p = .353). Respondents from Denmark reported higher relationship satisfaction as compared to respondents from Finland (p < .001) and Norway (p < .001), and respondents from Sweden reported higher relationship satisfaction than respondents from Norway (p = .029), but not Finland (p = .050).

Sex toy ownership was associated with greater sexual satisfaction (b = 0.090, p < .001), life satisfaction (b = 0.149, p < .001), and relationship satisfaction (b = .037, p < .001), though these effects were fairly small in size. In addition, respondents that reported owning more sex toys endorsed higher levels of sexual satisfaction (b = 0.014, p < .001) and life satisfaction (b = 0.009, p = .010), but not relationship satisfaction (b = 0.005, p = .169). Similarly, higher frequency of use of sex toys alone was associated with greater sexual satisfaction (b = 0.056, p < .001) and life satisfaction (b = 0.053, p < .001), but not relationship satisfaction (b = −0.009, p = .496). Further, higher frequency of use of sex toys with a romantic partner was associated with greater sexual satisfaction (b = 0.293, p < .001), life satisfaction (b = 0.198, p < .001), and relationship satisfaction (b = 0.175, p < .001). There were no significant interactions between these variables and country, suggesting that these associations did not significantly differ across countries of assessment.

Discussion

In response to the first research question, our cross-sectional six-country study of sex toy ownership and use in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, and the UK, found that generally more than half of respondents either owned or had owned a sex toy. Moreover, the most commonly owned sex toys were dildos and vibrators, followed by handcuffs, penis rings, and anal sex toys. Across countries, we found that the majority of sex toy owners reported using these either alone or with a steady partner (roughly 55–65% of respondents), while only a minority reported using sex toys with casual partners (roughly 10–15% of respondents). While these percentages are at the high end of the range of previous research on sex toy ownership, they corroborate previous findings that sex toy use is widespread across different populations, genders, and age groups (Dewitte & Reisman, Citation2021; Döring & Poeschl, Citation2020) and can be considered relatively common.

We speculate that, in the countries studied, the reason for this “normalization” stems from a combination of relatively liberal sexual attitudes across genders, easier and anonymous access to a larger variety of sex toys (i.e. face to face purchase is not needed), increased affordability of sex toys, general population wealth, and an increased focus on sex and sexual satisfaction as an important part of life (Frisch et al., Citation2019; Træen et al., Citation2019). While the use of sex toys in interpersonal sexual relations does not need to rest on the premise of a “steady relationship,” a steady relationship versus a casual relationship often fosters a larger degree of knowledge about each other’s sexual needs and desires, feelings of safety and security, less worry about, and risk of, STI transmission via sex toys, and repeated sexual interactions over prolonged periods of time (Anderson et al., Citation2014; Foxman et al., Citation2006; Hinchliff & Gott, Citation2004; Wentland & Reissing, Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2017). This may promote the use of sex toys or special categories of sex toys and be the reason for our finding of sex toys being used much more often in steady relationships than in casual relationships. Moreover, in regard to men’s toy ownership, earlier research showed that ownership of vibrating condom rings and penile rings were less popular while later in the 2000s they became more commonly used as did male masturbators (e.g. vibrators) (Reece et al., Citation2009). Our percentage of male masturbation products and penis rings ownership corroborates these findings in that a relatively large minority of respondents reported owning these products. This development may have to do with a number of factors, possibly a de-stigmatization of men as owners and users of male-oriented sex toys, companies adjusting their marketing strategies to also target the male demographic, changes in structural obstacles to the use and purchase of such products (e.g., while the anti-obscenity enforcement act of 1998 in Alabama, United States, is still in place, other states, as well as other countries, have become more tolerant and accepting of sex toys) (Lieberman, Citation2016; Miranda et al., Citation2019). In other words, consumer patterns may also change because commercial companies change their marketing approaches according to changes in societal perceptions, such as gender differences in sex toy use and ownership (Ronen, Citation2016).

We found many statistically significant predictors of ownership of sex toys, number of sex toys owned and frequency of use both alone and with a partner. However, with two important exceptions, these emerged as small in magnitude. The two exceptions concerned gender and age, where the predictive magnitudes of these variables on sex toy ownership and use were closer to medium in effect size. For gender, an inconsistent pattern of results emerged. While women were more likely than men to own a sex toy, when comparing men and women, who in fact reported owning sex toys, men reported owning a larger number of sex toys than women. Further, while women reported using sex toys more during sexual activities alone, men more than women reported using sex toys with a partner.

There are a few potential reasons why women may be more likely than men to own and use sex toys during solo sexual activities. One obvious reason may be that it is easier for women to reach orgasm using sex toys or that it may enhance their solo sexual experiences more as compared with men (Fahs & Swank, Citation2013; Herbenick et al., Citation2009). For example, while most men can reach orgasm by “hand jobs” (i.e., without the aid of a sex toy), whether alone or with a partner, women who prefer internal vaginal stimulation for orgasm may need to use a dildo or vibrator to do so as it can be impractical to do this with one’s own hand. Further, and importantly, women are more likely than men to have intercourse that does not result in an orgasm for themselves and may therefore prefer to use sex toys (e.g. a vibrator or dildo) to reach orgasm before, during or after sexual intercourse (Herbenick et al., Citation2023; Richters et al., Citation2006). Another significant reason for the gender differences in sex toy use during solo sexual activities may be that, traditionally, men more than women have used visual sexual stimuli (pornography) during solo sexual activities (Hald et al., Citation2014; Miranda et al., Citation2019) to enhance the sexual experience or reach orgasm. While this by no means excludes the use of sex toys, it may mean that men have been less likely to explore other avenues of sexual enhancement and achieving orgasm, such as with the use of sex toys (Reece et al., Citation2009) especially during solo activities. In support of the latter, vibrator use by men highly depends on partnership status. For example, among a sample of heterosexual men in a nationally representative study in the USA, those who reported vibrator use reported it most commonly used during partnered sexual activities (partnered foreplay and intercourse vs. masturbation; Reece et al., Citation2010).

Past research on age and sex toy use have provided equivocal results (Herbenick et al., Citation2009; Schick et al., Citation2011; Træen et al., Citation2021; Wood et al., Citation2017). The results from our study of age and sex toy ownership and use appear less ambiguous in that younger age was found to consistently and significantly predict sex toy ownership (both ownership and number of sex toys owned) and use (both during sexual activity alone and with a partner). At the time of data collection (Citation2022), the pricing of sex toys was more diversified than ever before, offering both better quality sex toys at lower cost and very cheap sex toys, as compared to previous times. Additionally, in the investigated countries (e.g., Denmark), sex toys have entered mainstream retail or are readily available by anonymous day-to-day postal services. We believe this indicates a greater acceptance of sex toys as a common “commodity” and enables younger generations easier and cheaper access to sex toys than previously (Schick et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2017). There is some evidence to suggest that younger people may be more sexually experimental or less set in their sexual behavior than older people, although this can vary depending on a number of factors (Leveque & Pedersen, Citation2012; Træen et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). One reason why younger people may be more sexually experimental can simply be that, compared to older generations, they have grown up in a more sexually liberated climate that has influenced them toward the development of more liberal sexual attitudes and behaviors that normalize sexual experimentation and increase openness to new sexual experiences, including the use of sex toys (Træen et al., Citation2021). Combined, we suggest that the cost reduction of sex toys, sex toys as an easily available commodity, and the (more) sexually experimental nature of younger people compared to older people, are some of the main drivers of the consistent findings of younger age as a predictor of sex toy ownership and use in this study. At the same time, we acknowledge that the level of sexual experimentation engaged in by an individual is influenced by factors other than age such as societal norms, previous sexual experiences, and (sexual) sensation seeking proclivities (Coyne et al., Citation2019; Træen et al., Citation2021).

In our second research question, we investigated whether sex toy ownership and use were associated with sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and life satisfaction in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, and the UK. Controlling for socio-demographic factors, parental status, sexual orientation, number of sex partners, and relationship status and length, we found that sex toy ownership and use was significantly associated with higher sexual satisfaction and life satisfaction, while higher relationship satisfaction was only significantly associated with currently owning a sex toy (but not number of sex toys) and higher frequency of sex toy use with a partner (but not alone). We also found that these results were consistent across all six countries investigated and that the inclusion of sex toy ownership and use significantly contributed to the total explained variance of sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction.

By far, out of all variables investigated, the strongest contributor to sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction was the frequency of use of sex toys with a partner. While we found many significant predictors of sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction, the magnitude of these were generally small in size, while the magnitudes of frequency of use of sex toys with a partner on sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction were medium in size. The reason for this may be that the frequency of sex toy use with a partner is a proxy for more general feelings of relationship security, safety, open communication, and openness to shared sexual experimentation. These feelings likely allow both for the exploration of sexuality within the couple, for example, using sex toys for fun, to help achieve orgasm, or to experiment and communicate sexually, and promote greater sexual, relationship, and life satisfaction (Bennett et al., Citation2019; Fleishman et al., Citation2020; Herbenick et al., Citation2010; Reece et al., Citation2009, Citation2010; Roels & Janssen, Citation2020; Rubinsky & Hosek, Citation2020; Smedley, Citation2020). To include sex toys in partnered sexual activities usually demands revealing an interest in including them, then deciding on and acquiring the sex toys, and finally negotiation how and when to include these in partnered sexual activities. These “reveal, decision, acquisition and negotiation” processes may be most successfully, if accompanied by more general feelings of relationship security, safety, open communication, and openness. For example, some women feel insecure and embarrassed about introducing vibrators in their sexual lives, as they fear their partner’s reaction, while other women enjoy sex toy purchase and use as a shared experience with their partner (Mayr, Citation2021). However, feelings of relationship security, safety, good communication, and openness may mitigate such fears and insecurities, regardless of gender. In other words, while sex toy use with a partner may promote sexual satisfaction, life satisfaction and relationship satisfaction this relationship is likely bi-directional in nature so that relationship satisfaction, life satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction also influence the frequency of sex toy use with a partner. Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, we cannot investigate this but hope future research in the area will allow for designs that can.

While we found some cross-country differences in the main outcomes, to our surprise, these differences in ownership and user patterns as well as their explanatory power for sexual, relationship, and life satisfaction (even when significant) was generally limited. In fact, the only results that stand out in this regard are those related to patterns of ownership of specific sex toys. Specifically, in France a smaller proportion of people owned a sex toy or owned specific sex toys, in comparison to individuals from the other countries in the study. While these results are not surprising, as they reflect previous findings showing that sexual attitudes, policies and behaviors, and education and beliefs in the Nordic countries are among the most liberal in the world and have been for decades (Fischer et al., Citation2022; Paton et al., Citation2020; Roien et al., Citation2022; Sauer & Siim, Citation2020), we would have expected this to be translated into (even) larger differences in sex toy ownership and use rates when compared with France and the UK. We speculate that the reason for not finding larger differences in ownership and user patterns can be attributed to fewer general differences in sexual attitudes, policies, and behaviors between the European countries investigated. Furthermore, the time frame during which the research was conducted (today as compared to in the past) may also have impacted the findings.

The study offers a unique cross-country investigation of sex toy ownership and use, and their associations with sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction using a large sample of respondents. However, the study was cross-sectional by design, which precludes causal conclusions. Consequently, as also touched upon above, while it may be that, for example, sex toy use may be increasing sexual and relationship satisfaction, it is equally possible that those who already have higher sexual, and relationship satisfaction are also more willing to include sex toys in their solo or partnered sexual activities, because they feel more secure in doing so. The relationships may also be more bi-directional in nature so that, for example, sex toy use increases sexual satisfaction, which then promotes further engagement with and use of sex toys. We think these are important points of clarification in the area and urge future researchers in the area to employ longitudinal and event-contingent designs that are better suited to parse this out. Other study limitations include the nature of the sample. While we used large samples in all countries and the survey was distributed to a representative sample of people based on gender, age, and region of country, previous research also fairly consistently shows that opt-in panels are not really representative of the population (Göritz, Citation2007; Sohlberg et al., Citation2017). For example, opt-in panels tend to prioritize individuals who have an interest in the research at hand, and panels such as those responding to e-mail invitations exclude people who lack access to the Internet and a connecting device, as well as technology skills (Sohlberg et al., Citation2017). Therefore, caution against generalizing the results to the background populations should be taken. Moreover, although sexual cultures across countries may be more similar today compared to pre-Internet times most cited previous research utilized North American samples, which may not provide the best comparison and contextualization of these results based on European samples. Further, as demonstrated by Wong et al. (Citation2023), although great care was taken in translating the surveys to the six different languages, translational bias and issues may also have influenced study results and comparisons across cultures as could differences in response rates across included countries. Finally, our measures of sexual, life and relationship satisfaction were all one item measures. While one item measures in the previous research on sexual, relational, and life satisfaction or related outcomes have been found to be valid and reliable (Cheung & Lucas, Citation2014; Fülöp et al., Citation2022; Jovanović, Citation2016; Jovanović & Lazić, Citation2020; Mark et al., Citation2014; Mellor et al., Citation2008), the estimates obtained by such measures are often crude and lack the ability to differentiate or offer nuanced insights into the areas measured. For example, it may well be that sex toys can increase sexual, life, and relationship satisfaction in some ways, while at the same time decreasing them in other ways, depending on context, sample characteristics, and other confounding factors involved. Therefore, in accordance with other researchers, we suggest further investigations of single item scale validity depending on context and encourage studies in this field to employ more multifaceted measurements of the outcome variables investigated.

In conclusion, the findings offer a cross-country European perspective on the frequency of sex toy ownership and use. We generally found that the majority of respondents owned a sex toy and that the most common sex toys owned were dildos and vibrators, followed by handcuffs, penis rings, and anal sex toys. Further, across countries, the majority of sex toy owners reported using these either alone or with a steady partner (55–65%) and a minority with casual partners (10–15%). Controlling for socio-demographics, parental status, sexual orientation, number of sex partners, and relationship status and length, we found that sex toy ownership and use was significantly associated with higher sexual satisfaction and life satisfaction, while higher relationship satisfaction was only significantly associated with currently owning a sex toy (but not number of sex toys) and frequency of use with a partner (but not alone). Across the results, we generally found little cross-country variation and differences.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sinful ApS for making the data available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2304575.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We elected to cap the age at 80 years, in part because we observed what we judged to be “unbelievable” values. For instance, 29 people reported being 99 or 100 years old, accounting for .24% of the data (those reporting an age between 81 and 98 accounted for only .08% of the data). Moreover, several of these extreme ages were matched with extreme values on the number of sex toys variable (5 people reported being 100 years of age and having 42 sex toys). In total, by capping the age at 80, we removed only 38 participants, corresponding to .32% of the data.

2 It was intended that “Single (dating)” refer to people who are not in a steady relationship (that is, they are single), but are open to and go on dates with one or more people. Conversely, people who are “in a relationship (not living together)” are people who consider themselves in a steady relationship, but do not live with their romantic partner.

3 In the Plan of Analysis and the Results sections, we use the word “predict” to refer to statistical prediction, to estimate associations between variables.

References

- Anderson, T. A., Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2014). A study of human papillomavirus on vaginally inserted sex toys, before and after cleaning, among women who have sex with women and men sexually transmitted infections. 90, 529–531.

- ASHR. (2022). Australian Study of Health and Relationships. https://www.ashr.edu.au/about-ashr

- Ayalon, L., Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Levkovich, I. (2019). Older adults’ coping strategies with changes in sexual functioning: Results from qualitative research. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.11.011

- Bennett, M., LoPresti, B. J., & Denes, A. (2019). Exploring trait affectionate communication and post sex communication as mediators of the association between attachment and sexual satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109505

- Cheung, F., & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Quality of Life Research, 23(10), 2809–2818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4

- Council, W. (2020). Substantive due process and a comparison of approaches to sexual liberty. Fordham Law Review, 89(1), 195–229. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol89/iss1/16

- Coyne, S. M., Ward, L. M., Kroff, S. L., Davis, E. J., Holmgren, H. G., Jensen, A. C., Erickson, S. E., & Essig, L. W. (2019). Contributions of mainstream sexual media exposure to sexual attitudes, perceived peer norms, and sexual behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(4), 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.016

- Crewe, L., & Martin, A. (2017). Sex and the city: Branding, gender and the commodification of sex consumption in contemporary retailing. Urban Studies, 54(3), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016659615

- Dewitte, M., & Reisman, Y. (2021). Clinical use and implications of sexual devices and sexually explicit media. Nature Reviews Urology, 18(6), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-021-00456-2

- Döring, N., & Poeschl, S. (2020). Experiences with diverse sex toys among German heterosexual adults: Findings from a national online survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(7), 885–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1578329

- Fahs, B., & Swank, E. (2013). Adventures with the “plastic man”: Sex toys, compulsory heterosexuality, and the politics of women’s sexual pleasure. Sexuality & Culture, 17(4), 666–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-013-9167-4

- Fischer, N., Graham, C. A., Træen, B., & Hald, G. M. (2022). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1385–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02071-z

- Fleishman, J. M., Crane, B., & Koch, P. B. (2020). Correlates and predictors of sexual satisfaction for older adults in same-sex relationships. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(14), 1974–1998. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1618647

- Foxman, B., Aral, S. O., & Holmes, K. K. (2006). Common use in the General population of sexual enrichment aids and drugs to enhance sexual experience. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 33(3), 156–162.

- Frisch, M., Moseholm, E., Andersson, M., Bernhard Andresen, J., & Graugaard, C. (2019). Sex in Denmark—Key findings from project SEXUS 2017–2018 [English Summary]. Aalborg Universitet; Statens Serum Institut. https://files.projektsexus.dk/2019-10-26_SEXUS-rapport_2017-2018.pdf

- Fülöp, F., Bőthe, B., Gál, É., Cachia, J. Y. A., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2022). A two-study validation of a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction: RAS-1. Current Psychology, 41(4), 2109–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00727-y

- Göritz, A. S. (2007). Using online panels in psychological research. In A. Joinson, K. McKenna, T. Postmes & U. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of internet psychology (pp. 473–485). Oxford University Press.

- Hald, G. M., Seaman, C., & Linz, D. (2014). Sexuality and pornography. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, vol. 2: Contextual approaches (pp. 3–35). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14194-001

- Herbenick, D., Fu, T., & Patterson, C. (2023). Sexual repertoire, duration of partnered sex, sexual pleasure, and orgasm: Findings from a US nationally representative survey of adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 49(4), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2022.2126417

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., Ghassemi, A., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Women’s vibrator use in sexual partnerships: Results from a nationally representative survey in the United States. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 36(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230903375677

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S., Dodge, B., Ghassemi, A., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2009). Prevalence and characteristics of vibrator use by women in the United States: Results from a nationally representative study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(7), 1857–1866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01318.x

- Hinchliff, S., & Gott, M. (2004). Intimacy, commitment, and adaptation: Sexual relationships within long-term marriages. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(5), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504045889

- Jovanović, V. (2016). The validity of the Satisfaction with Life scale in adolescents and a comparison with single-item life satisfaction measures: A preliminary study. Quality of Life Research, 25(12), 3173–3180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1331-5

- Jovanović, V., & Lazić, M. (2020). Is longer always better? A comparison of the validity of single-item versus multiple-item measures of life satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(3), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9680-6

- Kwakye, A. S. (2020). Using sex toys and the assimilation of tools into bodies: Can sex enhancements incorporate tools into human sexuality? Sexuality & Culture, 24(6), 2007–2031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09733-5

- Leveque, H. R., & Pedersen, C. L. (2012). Emerging adulthood: An age of sexual experimentation or sexual self-focus? The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 21(1), 29–40.

- Lieberman, H. (2016). Selling sex toys: Marketing and the meaning of vibrators in early twentieth-century America. Enterprise & Society, 17(2), 393–433. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2015.97

- Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

- Mayr, C. (2021). Beyond plug and play: The acquisition and meaning of vibrators in heterosexual relationships. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12601

- Mayr, C. (2022). Toy stories: The role of vibrators in domestic intimacies. Sexualities, 25(7), 962–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607211000194

- Meiller, C., & Hargons, C. N. (2019). “It’s happiness and relief and release”: Exploring masturbation among bisexual and queer women. Journal of Counseling Sexology & Sexual Wellness: Research, Practice, and Education, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.34296/01011009

- Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020

- Miranda, E. P., Taniguchi, H., Cao, D. L., Hald, G. M., Jannini, E. A., & Mulhall, J. P. (2019). Application of sex aids in men with sexual dysfunction: A review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(6), 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.03.265

- Nixon, P. G., & Marco Scarcelli, C. (2022). Coming of age—The alluring development of sex toys. In E. Rees (Ed.), The Routledge companion to gender, sexuality, and culture (1st ed., pp. 293–303). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367822040-30

- Paton, D., Bullivant, S., & Soto, J. (2020). The impact of sex education mandates on teenage pregnancy: International evidence. Health Economics, 29(7), 790–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4021

- Piha, S., Hurmerinta, L., Järvinen, E., Räikkönen, J., & Sandberg, B. (2020). Escaping into sexual play: A consumer experience perspective. Leisure Sciences, 42(3–4), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1712279

- Queen, C. (2013). Sexual enhancement products. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(12), 3155–3156. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12373

- Reece, M., Herbenick, D., Dodge, B., Sanders, S. A., Ghassemi, A., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Vibrator use among heterosexual men varies by partnership status: Results from a nationally representative study in the United States. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 36(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2010.510774

- Reece, M., Herbenick, D., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., Ghassemi, A., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2009). Prevalence and characteristics of vibrator use by men in the United States. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(7), 1867–1874. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01290.x

- Richters, J., de Visser, R. O., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M. A., Rissel, C., Simpson, J. M., & Grulich, A. E. (2014). Masturbation, paying for sex, and other sexual activities: The second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Sexual Health, 11(5), 461. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14116

- Richters, J., de Visser, R., Rissel, C., & Smith, A. (2006). Sexual practices at last heterosexual encounter and occurrence of orgasm in a national survey. The Journal of Sex Research, 43(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552320

- Richters, J., Grulich, A. E., de Visser, R. O., Smith, A. M. A., & Rissel, C. E. (2003). Sex in Australia: Autoerotic, esoteric and other sexual practices engaged in by a representative sample of adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 27(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00806.x

- Roels, R., & Janssen, E. (2020). Sexual and relationship satisfaction in young, heterosexual couples: The role of sexual frequency and sexual communication. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(9), 1643–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.013

- Roien, L. A., Graugaard, C., & Simovska, V. (2022). From deviance to diversity: Discourses and problematisations in fifty years of sexuality education in Denmark. Sex Education, 22(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2021.1884060

- Ronen, S. (2016). Properly selling the improper. Thresholds, 44, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1162/thld_a_00119

- Rubinsky, V., & Hosek, A. (2020). “We have to get over it”: Navigating sex talk through the lens of sexual communication comfort and sexual self-disclosure in LGBTQ intimate partnerships. Sexuality & Culture, 24(3), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09652-0

- Satinsky, S., Rosenberger, J. G., Schick, V., Novak, D. S., & Reece, M. (2011). USA study of sex toy use by HIV-positive men who have sex with other men: Implications for sexual health. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 22(8), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2011.010488

- Sauer, B., & Siim, B. (2020). Inclusive political intersections of migration, race, gender and sexuality – the cases of Austria and Denmark. Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 28(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2019.1681510

- Schick, V. R., Hensel, D., Herbenick, D., Dodge, B., Reece, M., Sanders, S., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2015). Lesbian- and bisexually-identified women’s use of lubricant during their most recent sexual event with a female partner: Findings from a nationally representative study in the United States. LGBT Health, 2(2), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0058

- Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Rosenberger, J. G., & Reece, M. (2011). Prevalence and characteristics of vibrator use among women who have sex with women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(12), 3306–3315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02503.x

- Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Rosenberger, J. G., & Reece, M. (2012). Variations in the sexual repertoires of bisexually-identified women from the United States and the United Kingdom. Journal of Bisexuality, 12(2), 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2012.674856

- Smedley, D. K. (2020). Links between commitment, financial mutuality, communication, and relationship satisfaction. Brigham Young University Family Perspectives, 1(2), 1–6. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/familyperspectives/vol1/iss2/3

- Sohlberg, J., Gilljam, M., & Martinsson, J. (2017). Determinants of polling accuracy: The effect of opt-in internet surveys. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 27(4), 433–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2017.1300588

- Træen, B., Carvalheira, A. A., Hald, G. M., Lange, T., & Kvalem, I. L. (2019). Attitudes towards sexuality in older men and women across Europe: Similarities, differences, and associations with their sex lives. Sexuality & Culture, 23(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9564-9

- Træen, B., Fischer, N., & Kvalem, I. L. (2021). Sexual intercourse activity and activities associated with sexual interaction in Norwegians of different sexual orientations and ages. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 38(4), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.1912316

- Træen, B., Fischer, N., & Kvalem, I. L. (2022). Sexual variety in Norwegian men and women of different sexual orientations and ages. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1952156