ABSTRACT

Loneliness is prevalent among sexual minority adults and is associated with minority stress. Yet there is limited understanding of how loneliness and minority stress vary across key demographic variables. This cross-sectional study explored age and gender differences in a minority stress model linking sexual orientation marginalization to social and emotional loneliness via proximal stress (internalized homonegativity, concealment, and stigma preoccupation) and via social anxiety and inhibition. The study also assessed age and gender differences in the protective influence of LGBTQ community involvement. 7,856 sexual minority adults from 85 countries completed an online survey. They were categorized as emerging adults (18−24, n = 3,056), young adults (25−34, n = 2,193), midlife adults (35−49, n = 1,243), and older adults (50−88, n = 1,364). Gender identity groups were cisgender men (n = 4,073), cisgender women (n = 3,017), and transgender individuals (n = 766). With each successive age group, there was a lower prevalence of sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and emotional loneliness, along with more community involvement. Sexual orientation marginalization was more pronounced among cisgender women and, especially, transgender individuals. The latter also exhibited the most social anxiety, inhibition, loneliness, and community involvement. Proximal stress was more prevalent among cisgender men than cisgender women and transgender individuals. Multiple group structural equation modeling supported the applicability of the loneliness model across age and gender groups, with only a few variations; these mainly related to how strongly community involvement was linked to marginalization, internalized homonegativity, and social loneliness.

Introduction

Loneliness is a painful emotion resulting from a mismatch between actual and desired relationships (Perlman & Peplau, Citation1981). It manifests in two forms (Weiss, Citation1973). Social loneliness is the perceived absence of a broad supportive network, like friends or family, that provides a sense of belonging, companionship, and community. Emotional loneliness is the perceived lack of closer, intimate attachments, like a spouse or best friend, and is often characterized by feelings of detachment, desolation, and rejection. Depending on one’s unique needs for social connection and intimacy, and how the quality of relationships is perceived, a person may feel lonely on their own, in a relationship, or in a group. The subjective nature of loneliness distinguishes it from the objective state of social isolation. While loneliness evolved to motivate social connection (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2018), unresolved loneliness is linked to increased risk for morbidity and early mortality (Wang et al., Citation2023). Thus, it is a public health issue prompting attention from governments around the world (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport [UK], Citation2018; Office of the United States Surgeon General, Citation2023).

There are various risk factors for loneliness, including a small social network (if a larger one is desired), poor relationship quality, attachment insecurity, unrealistic relationship standards, social anxiety, depression, neuroticism, disability, and genetic factors (de Jong Gierveld et al., Citation2018; Hutten et al., Citation2022; Lim et al., Citation2020). Loneliness can perpetuate itself by promoting social anxiety, hypervigilance, misperception of social cues, social withdrawal, and aversive interactions with others (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2018; Eldesouky et al., Citation2024; Maes, Nelemans, et al., Citation2019; Qualter et al., Citation2015; Spithoven et al., Citation2017).

Sexual Orientation and Loneliness

Sexual minority status is another risk factor for loneliness, as evidenced by studies from various countries (e.g., Buczak-Stec et al., Citation2023; Doyle & Molix, Citation2016; Eres et al., Citation2021; Hsieh & Liu, Citation2021; Marquez et al., Citation2023; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). This vulnerability may be partially attributed to sociodemographic disparities, as these and other studies have found that sexual minorities are more likely to be socially isolated, single, living alone (even when partnered), childless, in less frequent contact with families of origin, and economically disadvantaged (Bränström et al., Citation2023a; Drydakis, Citation2022; Green, Citation2016; Hernández Kent & Scott, Citation2022; Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, Citation2016; Kneale, Citation2016; Peterson et al., Citation2023; Statistics Canada, Citation2021; van Lisdonk & Kuyper, Citation2015). They also tend to report lower levels of perceived social support (Eres et al., Citation2021) and social capital (Doyle & Molix, Citation2016).

Another reason for the sexual orientation disparity in feelings of loneliness may be minority stress: the negative impact of living with a stigmatized identity (Meyer, Citation2003). There are two types of minority stress: distal and proximal. Distal stress involves experiences of marginalization like discrimination, harassment, and violence. Proximal stress refers to internal, subjective reactions to distal stress, and includes concealment of one’s sexual orientation, internalized homonegativity, rejection sensitivity, and stigma preoccupation – an excessive concern about being judged based on one’s sexual orientation (Dyar et al., Citation2018). Research across various age groups and countries has found that both distal and proximal stress are associated with increased loneliness (Hughes et al., Citation2023; Jackson et al., Citation2019; Jenkins Morales et al., Citation2014; Jomar et al., Citation2021; Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, Citation2016; Kittiteerasack et al., Citation2022; Kuyper & Fokkema, Citation2010; Mereish & Poteat, Citation2015).

Mechanisms Linking Sexual Minority Stress and Loneliness

Being marginalized as a sexual minority could increase feelings of loneliness by making one feel different, misunderstood, invalidated, and estranged from others. Additionally, it could exacerbate proximal stressors that impede the formation of new relationships and that adversely impact the quality of existing ones. For instance, internalizing negative perceptions of one’s sexual orientation or same-gender relationships may diminish one’s perceived attractiveness as a friend or partner, and may lead to shame, interpersonal avoidance, concealment of sexual orientation, mistrust, unrealistic relationship standards, and relationship dissatisfaction (Downs, Citation2012; Doyle & Molix, Citation2015; Mereish & Poteat, Citation2015; Pepping et al., Citation2019). Concealing one’s sexual orientation could increase social inhibition, inauthenticity, and relationship strain (Cronin & King, Citation2014; Knoble & Linville, Citation2012; Newheiser & Barreto, Citation2014). Preoccupation with stigma and sensitivity to rejection can foster social anxiety, inhibition, misinterpretation of social cues, and aversive interpersonal behavior (Feinstein, Citation2020). The potential causal role of these factors has been supported by prospective research, which has found that both distal and proximal minority stress are associated with increased loneliness over time (Jackson et al., Citation2019; Vale, Citation2023). Theoretically, loneliness could also exacerbate minority stress through its adverse effects on social cognition and behavior (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2018; Spithoven et al., Citation2017).

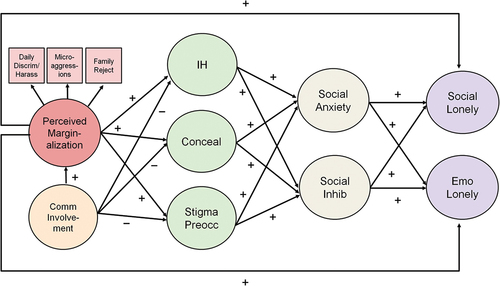

Based on this research, Elmer et al. (Citation2022) proposed a comprehensive model linking minority stress with loneliness (). They found that marginalization, including experiences of discrimination, family rejection, and microaggressions, was positively associated with both social and emotional loneliness. This relationship was partly indirect through the influence of proximal stress—particularly stigma preoccupation—and subsequently through social anxiety and inhibition. Moreover, LGBTQ community involvement seemed to offer protection: among those who were more engaged in the community, the links between marginalization and proximal stress were weaker, as were those between stigma preoccupation and social anxiety, and between social inhibition and social loneliness. While genetic and environmental factors may confound the relationship between minority stress and loneliness (Bailey, Citation2020; Lilienfeld, Citation2017), Elmer et al. (Citation2022) found that their model remained robust even after controlling for dispositional negative affectivity, although the strength of several associations diminished.

Figure 1. Theoretical model linking marginalization and loneliness.

These findings supported Hatzenbuehler’s (Citation2009) psychological mediation framework, which aims to understand how minority stress “gets under the skin.” However, the validity of this loneliness model has not been assessed across key demographic factors like age or gender.

Minority Stress and Loneliness Across Age Groups

While the relationship between age and loneliness is frequently explored in the general population (Hutten et al., Citation2022; Mund et al., Citation2020), it is less frequently examined among sexual minorities. The current study sought to address this gap by assessing the validity of Elmer et al.’s (Citation2022) loneliness model, as well as the prevalence of its underlying factors, across different ages. Four groups were compared based on participants’ age in 2016 (the year of data collection): emerging adults (ages 18–24, born 1992–1998), young adults (ages 25–34, born 1982–1991), midlife adults (ages 35–49, born 1967–1981), and older adults (ages 50–88, born 1928–1966). The selection of these categories was informed by other international studies of loneliness (Delaruelle, Citation2023) and aimed to reflect life course, generational, and maturational differences among sexual minorities globally (Bitterman & Hess, Citation2021; CBRC, Citation2017; Hammack et al., Citation2018; Ipsos, Citation2021; Leonard et al., Citation2012; Meyer et al., Citation2021).

Life Course Transitions

In the general population, loneliness follows a roughly U-shaped curve, with peaks among young people and those aged 70 and above (Mund et al., Citation2020). This pattern may be due in part to life course transitions. For younger people, concerns about fitting in, relocating for education or employment, and not having a partner can increase loneliness, while older adults may grapple with a reduced social network due to retirement, the loss of a partner, or health problems. These challenges may be amplified among sexual minorities. During adolescence, they experience more victimization (Johns et al., Citation2020) and less family support (Watson et al., Citation2019) compared to their heterosexual peers. These disparities may have persistent effects in emerging, young, and middle adulthood, including internalized homonegativity (Puckett, Citation2015), depression (Ryan et al., Citation2009), socioeconomic disadvantage (Drydakis, Citation2019) and, likely, loneliness (Matthews et al., Citation2022). While LGBTQ community involvement can mitigate some of these effects, it could also increase marginalization (Elmer et al., Citation2022), as emerging adults’ community participation tends to be more publicly visible (e.g., attending LGBTQ clubs and pride events). These factors underscore the unique vulnerability of this age group. Fortunately, marginalization and proximal minority stress appear to be less common from emerging to middle adulthood (CBRC, Citation2017; EU, Citation2020; Frost et al., Citation2022; Leonard et al., Citation2012; Meyer et al., Citation2021; Rice et al., Citation2021; Vale, Citation2023; Vale & Bisconti, Citation2021). Over time, emerging sexual minorities may transition to more accepting environments, develop greater comfort with their sexuality, disclose their sexual orientation more widely, and form relationships with sexual minority peers. The transitions could reduce loneliness from emerging to middle adulthood.

The impact of life course transitions on loneliness among older sexual minorities is more nuanced. By virtue of age, they may have experienced more cumulative lifetime marginalization. They may also confront a dual invisibility within both the general population and among their younger peers within the LGBTQ community (Higgins et al., Citation2011; Lyons et al., Citation2015). Older sexual minority men in particular may report feeling marginalized or misunderstood by younger men, who may view them as unattractive or even “predatory” (Armengol & Varela-Manograsso, Citation2022; Willis et al., Citation2022). They may feel especially invisible in mainstream LGBTQ spaces and on digital platforms (CBRC, Citation2017; Cronin & King, Citation2014). These experiences, coupled with age-related stigma, can contribute to self-consciousness (Casey, Citation2019), internalized gay ageism (Wight et al., Citation2015), and a feeling of “accelerated aging” (Schope, Citation2005). In addition, while older sexual minorities are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to communicate with friends (Peterson et al., Citation2023), this may not fully compensate for their weaker or non-existent kinship ties (Green, Citation2016). Friendships may also become strained as peers are relied upon to provide care that would typically be provided by partners or relatives (Hsieh & Liu, Citation2021). A greater reliance on peer support may also pose challenges as friends die, move away, or become ill (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2015). Together, these factors could increase loneliness in this age group. On the other hand, several studies find that older sexual minorities are less likely to experience recent sexual orientation marginalization, anticipated stigma, and internalized homonegativity compared to younger peers (CBRC, Citation2017; EU, Citation2020; Jenkins Morales et al., Citation2014; Lyons et al., Citation2012; Meyer et al., Citation2021; Vale, Citation2023; Vale & Bisconti, Citation2021). These factors could reduce loneliness in this age group.

Generational Differences

Older sexual minorities who came of age before the gay liberation movements of the late 1960s experienced greater and more intense marginalization than their contemporaries (Bitterman & Hess, Citation2021; Hammack et al., Citation2018). This could have contributed to enduring proximal stress, especially concealment of sexual identity (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2015; Grindey-Bell, Citation2021; Higgins et al., Citation2011). Some faced intense challenges coming out later in life, leading to estrangement from friends and family (Cronin & King, Citation2014; Grindey-Bell, Citation2021; Lyons et al., Citation2015). They may also miss the solidarity they experienced during the subsequent gay liberation movement (Higgins et al., Citation2011; Lyons et al., Citation2015). These factors could contribute to greater loneliness in this age group.

By contrast, emerging, young, and midlife adults came of age when acceptance and LGBTQ rights were gradually improving around the world (Flores, Citation2021; Ipsos, Citation2021). As a result, many have developed a growing sense of pride and have disclosed their sexual orientation earlier and more widely (CBRC, Citation2017; EU, Citation2020; Jenkins Morales et al., Citation2014; Meyer et al., Citation2021). These factors may potentially mitigate loneliness in these age groups. Yet stigma persists, so coming out earlier may increase the risk for marginalization, proximal stress, and subsequent feelings of loneliness. In addition, midlife adults, who lived through the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, faced discrimination and experienced trauma from losing friends and partners (Hammack et al., Citation2018; Oswald & Roulston, Citation2020). They were also more vocal about LGBTQ rights, which exposed them to stigma and potentially heightened their sensitivity to present-day marginalization. Indeed, one study identified two peaks in reported past-year marginalization: one in emerging adulthood, as expected, but another smaller one in midlife (Rice et al., Citation2021). This midlife peak was more evident among men, which may reflect the enduring stigma surrounding AIDS and its lasting impact on this group.

Yet despite encountering adversity, midlife and older adults have also exhibited resilience by cultivating LGBTQ communities and chosen families based on friendships (Bitterman & Hess, Citation2021; Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Weeks et al., Citation2001). The loss of friends and partners to AIDS may have fostered stronger bonds with survivors (Cronin & King, Citation2014). For some, marginalization has bolstered their confidence to disclose their sexual orientation (Grindey-Bell, Citation2021). These findings resonate with crisis competence theory, which suggests that adversity can promote mastery and resilience (Friend, Citation1991; Kimmel, Citation1978). Notably, Australian research shows that resilience among sexual minorities is more common with age, peaking around ages 60 to 89 (Leonard et al., Citation2015). These positive factors may contribute to lower levels of loneliness among midlife and older adults compared to their younger counterparts. In addition, the associations between minority stress, social anxiety/inhibition, and loneliness may parallel or even be weaker than those observed among younger individuals. Conversely, the protective influence of LGBTQ community involvement may be stronger with age.

Maturational Changes

In the general population, there is an increase in emotional stability from emerging adulthood until around age 80 (Graham et al., Citation2020). There is also greater focus on positive experiences, emotions, and high-quality relationships, as suggested by socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Citation2006). From emerging adulthood to midlife, there is an increase in perceived control (CBRC, Citation2017; Robinson & Lachman, Citation2017) and awareness that loneliness is often temporary (Qualter et al., Citation2015). These attributes are linked to reduced feelings of loneliness (Buecker et al., Citation2020; Drewelies et al., Citation2017; Qualter et al., Citation2015). Among sexual minorities, there may be greater resilience and less social anxiety with age (Leonard et al., Citation2015; Mahon et al., Citation2022). There may also be a decline in the tendency to perceive, focus on, remember, and worry about marginalization, potentially leading to a diminished impact of minority stress on social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness.

Hypotheses

Due to potentially countervailing influences among older adults, we did not have explicit hypotheses regarding prevalence or the magnitude of associations in our loneliness model for this age group. However, we did propose the following hypotheses for the other age groups:

H1.

Considering positive life course transitions and maturational changes, there is a lower prevalence of sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness from emerging, to young, to middle adulthood.

H2.

Considering positive life course transitions there is a greater degree of LGBTQ community involvement from emerging, to young, to middle adulthood.

H3.

The overall structure of the minority stress loneliness model () is valid across all age groups.

H4.

Considering positive maturational changes in personality, emotions, and coping, there is a weaker association between sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness (especially emotional loneliness) from emerging, to young, to middle adulthood.

H5.

Considering the more visible nature of LGBTQ community involvement among emerging adults, there is a stronger association between community involvement and sexual orientation marginalization for emerging adults vs. others.

H6.

Considering the duration and depth of friendships, especially for earlier generations who relied on support from LGBTQ peers, community involvement has a stronger protective effect against proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness from emerging, to young, to middle adulthood.

Gender Differences

A meta-analysis found that men are at slightly greater risk for both social and emotional loneliness across the lifespan (Maes, Qualter, et al., Citation2019). However, 75% of the studies were Western, with a focus on the US, and did not examine sexual minorities or the impact of marginalization.

Some studies suggest that sexual minority men tend to be less open about their sexual orientation compared to sexual minority women (EU, Citation2020; Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2012), although negligible differences have also been reported (Doan & Mize, Citation2020; Jenkins Morales, Citation2014). Additionally, sexual minority men, particularly gay men, are more likely to be single, living alone, and childless, and have smaller, less diverse, and less supportive social networks compared to sexual minority women (Doan & Mize, Citation2020; Erosheva et al., Citation2016; Hill et al., Citation2020, Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Hughes et al., Citation2023; Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, Citation2016; Lyons et al., Citation2021; Statistics Canada, Citation2021). Due to shorter life expectancy among men in general, sexual minority men often experience the loss of partners at an earlier age, in addition to facing the disproportionate impact of HIV/AIDS (Beam & Collins, Citation2019; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). These factors could increase their risk for loneliness.

Several studies also indicate that sexual minority men are more susceptible than sexual minority women to marginalization and its impact on internalized homonegativity, rejection sensitivity, and loneliness (Feinstein et al., Citation2012; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2013; Hughes et al., Citation2023; Rice et al., Citation2021; Toomey & Russell, Citation2016). Other studies show that while sexual minority women may face comparable or somewhat greater discrimination, harassment, and social exclusion, sexual minority men are disproportionately targeted by violence and threats (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2023; Hill et al., Citation2020; Jenkins Morales et al., Citation2014; Katz-Wise & Hyde, Citation2012; Leonard et al., Citation2012). Fears for their safety may explain why sexual minority men are more likely to conceal their sexual orientation, monitor their behavior in public, and avoid certain places (EU, Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2012). Gender disparities in violence and threats may stem from less accepting and more stigmatizing attitudes toward sexual minority men (Bettinsoli et al., Citation2020; Lyons et al., Citation2021). This is worse for gender nonconforming men, considering the perceived link between gender nonconformity and male homosexuality (Rule, Citation2017). Not only are gender nonconforming men more likely than gender nonconforming women to be perceived as homosexual (Sanborn-Overby & Powlishta, Citation2020), they are subject to increased prejudice and violence (Bränström et al., Citation2023b; Thoma et al., Citation2021). Sexual minority men may also experience unique intraminority stressors, such as competitive pressures arising from the high value placed on physical attractiveness and masculinity. This could lead to self-consciousness and feelings of exclusion (Pachankis et al., Citation2020).

Individuals who actually identify as transgender or gender-diverse face even greater vulnerabilities compared to cisgender peers. They report less acceptance and support from family and coworkers, along with increased violence, discrimination, social exclusion, anticipated rejection, and avoidance of places where they may be mistreated (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2023; EU, Citation2020; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2014; Hill et al., Citation2020; Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2021). These adversities may undermine their resilience (Leonard et al., Citation2015) and explain their higher levels of social anxiety and loneliness, especially if they also identify as sexual minorities (Anderssen et al., Citation2020; Mahon et al., Citation2023; McDanal et al., Citation2023; Yadegarfard et al., Citation2014).

But there may be some mitigating influences. A meta-analysis found that gender nonconforming sexual minorities are less likely to conceal their sexual orientation or experience internalized homonegativity (Thoma et al., Citation2021). These findings may extend to sexual minorities identifying as transgender, as they tend to be more gender nonconforming compared to sexual minorities who identify as cisgender (Toomey et al., Citation2010). It might be more challenging for them to conceal their sexual orientation, as gender nonconformity may signal sexual orientation to others (Rule, Citation2017). Additionally, they may develop crisis competence and a greater sense of pride through navigating social adversity (Thoma et al., Citation2021). These factors could mitigate loneliness in this group.

Finally, in terms of LGBTQ community involvement, it appears that cisgender women and transgender sexual minorities, especially transgender men and non-binary individuals, are more involved than cisgender men and consider it more important to them (Hill et al., Citation2020; Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). Community involvement also appears to have a greater positive impact on the psychological well-being and resilience of transgender sexual minorities compared to their cisgender peers, with cisgender men experiencing the fewest benefits (Leonard et al., Citation2015).

Hypotheses

H7.

The prevalence of sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness is higher among cisgender men than cisgender women.

H8.

Compared to cisgender sexual minorities, transgender sexual minorities experience more sexual orientation marginalization, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness. Conversely, they experience less proximal stress.

H9.

Cisgender women and transgender individuals are more involved in the LGBTQ community than cisgender men.

H10.

The overall structure of the minority stress loneliness model () is valid across all three gender groups.

H11.

The associations between sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness are stronger for transgender individuals and cisgender men compared to cisgender women.

H12.

The protective effect of LGBTQ community involvement against proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness is stronger for cisgender women and transgender individuals compared to cisgender men.

Method

Data Collection

After receiving ethics approval, an online survey was conducted during the spring and summer of 2016. To reach a global audience, we used paid social media click-ads to recruit adults aged 18+ for a study about “LGBTQ social relationships and well-being.” Most respondents were reached through Facebook (83%) or Instagram (4%), with the remainder through various other sites (e.g., Tumblr, Reddit) or email. Ads were targeted to users who had specified in their profile – either publicly or privately – that they were interested in people of the same gender or in LGBTQ topics. To reach people not as open about their sexual orientation, some ads were targeted to those who had specified no sexual preference at all. We also ran a more generic ad, referencing “social relationships and well-being,” with no mention of sexual orientation; 5% of respondents in the current analysis were reached this way. Ads were targeted to maximize diversity in age, gender, ethnoracial identity, relationship status, political orientation, and geography. To minimize comprehension problems, ads were shown to those who had indicated that they understood English. Participants could enter a draw for Amazon gift cards ranging from $20−$200 USD or a donation to a charity of their choice. They completed the survey anonymously using Qualtrics. They were able to pause and resume the survey within two weeks; 94% completed on the same day.

Participants

7,856 self-identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and pan/polysexual individuals from 85 countries were included in the current analysis (; Supplementary Figure S1). The completion rate was similar to other large online studies of minority stress (CBRC, Citation2017; Meyer et al., Citation2020). Item-level missing data were minimal. See Supplementary Appendix A for statistics on completers versus non-completers and the handling of missing data.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Measures

Loneliness

We used the 11-item de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (de Jong Gierveld & Kamphuis, Citation1985). The scale is valid and reliable for use across different countries, ethnicities, and ages (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, Citation2010; Penning et al., Citation2014; Uysal-Bozkir et al., Citation2017; van Tilburg et al., Citation2004). Five positively worded items measure feelings of social embeddedness and a sense of belonging (e.g., “There are plenty of people I can lean on when I have problems”). Six negatively worded items measure feelings of desolation and longing for an intimate attachment (e.g., “I miss having a really close friend”). Respondents indicated their agreement with each statement on a 5-point scale (1 = Yes!, 2 = Yes, 3 = More or less, 4 = No, 5 = No!). Responses were dichotomized:Footnote1 selecting 1, 2, or 3 for a positively worded item suggested social loneliness and was assigned a score of 1; selecting 3, 4, or 5 for a negatively worded item suggested emotional loneliness and was assigned a score of 1. Scores were summed to produce subscale totals for social and emotional loneliness, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. In the current study, internal consistency was strong: McDonald’s omega (ω) = .87 for social loneliness and .86 for emotional loneliness.

Sexual Orientation Marginalization

We used three measures which capture the most common forms of marginalization. Microaggressions were measured using the Second-Class Citizen subscale of the Homonegative Microaggressions Scale (HMS; Wegner & Wright, Citation2016). This subscale asks about experiences that can make sexual minorities feel inferior. Respondents indicated how often in the last twelve months they had experienced each of eight events (e.g., “People telling you to act differently at work, school, or other professional settings in order to hide your sexual orientation”). Response options ranged from 1 (Never/not applicable) to 5 (Constantly). Respondents also indicated how much each experience had bothered them (1 = Not at all/not applicable; 5 = A great deal). For each item, the two responses were multiplied; a scale score was calculated as the mean of the products, with higher scores indicating more experiences of microaggressions. ω = .83.

We measured everyday discrimination/harassment and family rejection using the Daily Heterosexist Experiences Questionnaire (DHEQ; Balsam et al., Citation2013). Respondents indicated how often in the last 12 months they had experienced various heterosexist events. Response options and scoring were the same as for the HMS. We used the 6-item Discrimination/Harassment subscale (e.g., “Being verbally harassed by strangers because you are LGBT”). We also used the 6-item Family of Origin subscale (e.g., “Your family avoiding talking about your LGBT identity”). To focus on marginalization related to sexual orientation and not gender identity, “LGBT” was replaced with “sexual orientation” (e.g., “Being verbally harassed by strangers because of your sexual orientation”). For Discrimination/Harassment, ω = .83; for Family of Origin, ω = .79.

Internalized Homonegativity

We used the six highest-loading items from the 11-item Personal Homonegativity subscale of Mayfield’s (Citation2001) Internalized Homonegativity Inventory (IHNI). This subscale assesses negative emotions and attitudes about one’s sexual orientation (e.g., “I feel ashamed of my homosexuality”). To be more inclusive, “my homosexuality” was changed to “being attracted to people of the same gender.” Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). Scores were averaged to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more internalized homonegativity. ω = .91.

Sexual Orientation Concealment

We used a modified version of the Concealment subscale of the Nebraska Outnesss Scale (Meidlinger & Hope, Citation2014). Respondents indicated how often they avoid mentioning or implying their sexual orientation when interacting with five groups: immediate family, extended family, friends, coworkers/associates, and strangers (0 = Never; 10 = Always). Examples include changing one’s mannerisms or avoiding topics related to sexual orientation or same-gender relationships. “Sexual orientation” was replaced with “attraction to people of the same gender.” Scores were averaged to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more concealment. ω = .82.

Stigma Preoccupation

We used the three-item Acceptance Concerns subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale (LGBIS; Mohr & Kendra, Citation2011). The items assess a person’s worries about how others perceive them based on their sexual orientation (e.g., “I often wonder whether others judge me for my sexual orientation”). “My sexual orientation” was changed to “my attraction to people of the same gender.” Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). Scores were averaged to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more stigma preoccupation. We refer to acceptance concerns as “stigma preoccupation” because the latter more accurately describes the items from this subscale (Dyar et al., Citation2018). ω = .85.

LGBTQ Community Involvement

Based on confirmatory factor analysis with the current sample, we selected the five highest-loading items from the seven-item Involvement with Gay Community Scale (Tiggemann et al., Citation2007). An example item is: “I am actively involved in the LGBTQ community.” Response options ranged from 1 (Not at all true of me) to 7 (Extremely true of me). Scores were averaged to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more community involvement. ω = .82.

Social Anxiety

We used the eight-item Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale−Straightforward Items (BFNE-S; Rodebaugh et al., Citation2004). This scale assesses global fear of negative evaluation (e.g., “I am afraid that people will find fault with me”). Response options ranged from 1 (Not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (Extremely characteristic of me). Scores were summed to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more social anxiety. ω = .95.

Social Inhibition

We used the Social Inhibition subscale of the DS14 Type D Personality Scale (Denollet, Citation2005). Respondents indicated agreement with seven statements (e.g., “I find it hard to start a conversation”). Response options ranged from 0 (False) to 4 (True). Scores were summed to produce a total score, with higher scores indicating more social inhibition. ω = .86.

Demographic Variables

Respondents indicated their sex assigned at birth (male/female) and current gender identity, which was dummy-coded as cisgender woman and transgender/non-binary/other, with cisgender man as the reference. Respondents also indicated their sexual orientation using self-identity labels, which we dummy-coded as mostly gay/lesbian/homosexual; bisexual; queer; and pan/polysexual, with gay/lesbian/homosexual as the reference. These labels corresponded closely with a Kinsey-type measure of sexual attraction (bearing in mind that not everybody defines their orientation solely by sexual attraction). Among cisgender men, 99% indicated sexual attraction to men only, men mostly, or men and women equally; the rest indicated attraction to women mostly, women only, nobody, or were unsure. Among cisgender women, 93% indicated sexual attraction to women only, women mostly, or women and men equally; 5% indicated attraction to men mostly; the remainder indicated attraction to men only, nobody, or were unsure. For those identifying as transgender/non-binary/other, the distributions were more even, as expected. Race/ethnicity was dummy-coded into Latinx/Hispanic, Asian, and Mixed/Multi/Other (no significant differences in the final category), with White as the reference. Country of residence was dummy-coded into eight regions: Latin America/Mexico, UK/Ireland, Western Europe (Other), Eastern Europe, Asia, Australia/New Zealand, South Africa, and Middle East/North Africa, with North America as the reference. Urbanicity was dummy-coded into suburban and small town/rural/remote, with urban as the reference. shows the original response options for the demographic variables. Supplementary Table S1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations between all scales.

Analytic Procedures

To compare mean scores and model associations by age, we divided the full sample into four groups based on respondents’ age at the time of data collection (2016):

Emerging adults: 18–24 years old (M = 20.9, SD = 1.9), born 1992–1998, n = 3,056

Young adults: 25–34 years old (M = 28.7, SD = 2.9), born 1982–1991, n = 2,193

Midlife adults: 35–49 years old (M = 41.2, SD = 4.5), born 1967–1981, n = 1,243

Older adults: 50–88 years old (M = 59.1, SD = 6.4), born 1928–1966, n = 1,364

To compare mean scores and associations by gender, we divided the full sample into three groups:

(E) Cisgender men (n = 4,073)

(F) Cisgender women (n = 3,017)

(G) Transgender (n = 766)

Sexual minorities in categories E and F identified with their gender assigned at birth. Category G included sexual minorities who identified as binary transgender (i.e., transgender man, n = 82; transgender woman, n = 147). It also included people outside the gender binary (e.g., non-binary, gender-queer; n = 440) or who have a binary identity opposite to their gender assigned at birth but who do not specifically identify as a gender minority (n = 39 assigned female at birth; n = 58 assigned male at birth). As the gender minority groups share a common experience – a high degree of stigma and discrimination – we included them in one category for purposes of the current analysis (Bauerband et al., Citation2019; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2014; Reisner et al., Citation2015). See Supplementary Table S2 for detailed demographic characteristics for each age and gender group.

Comparison of Group Means

We compared group means for all variables using ordinary least squares regression, with dummy codes for age and gender. To help reduce substantial skewness of the marginalization and internalized homonegativity scales, we used log-10 versions of these scales, which were then back-transformed. All means were adjusted for sexual orientation, ethnoracial identity, urbanicity, and the nine geographic regions (entered as fixed effects). Age means were adjusted for gender. Gender means were adjusted for age (continuous). Income and partner status were not controlled because these account for important age group differences in the dependent variables.

Linear regression was conducted using the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) function in SPSS 28 (IBM, Citation2022), specifying a normal distribution and identity link function. As the residual error terms were heteroskedastic, this allowed the use of robust standard errors (Huber–White cluster estimators) to compute 95% confidence intervals and significance tests. To facilitate interpretation, we reported y-standardized beta coefficients for age and gender, along with estimated marginal means for each group. We compared these coefficients between pairs of groups, changing the reference categories as needed. Y-standardized coefficients can be interpreted similarly to Cohen’s d. For greater precision, we also reported standardized group differences in latent means, which account for measurement error (see Supplementary Appendix A for procedures). To contextualize effect sizes, we referred to empirically derived reference values for social psychology, with 0.15 suggesting a small difference between groups, 0.36 a medium difference, and 0.65 a large difference (Lovakov & Agadullina, Citation2021).

Specification of the Structural Equation Model

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test our theoretical model () across groups. Unlike ordinary least squares regression, SEM simultaneously models complex relationships among latent variables while accounting for measurement error, providing a comprehensive understanding of the pathways connecting constructs. We formed latent variables (i.e., factors), each with multiple indicators. The marginalization factor was formed using scale totals for everyday discrimination/harassment, microaggressions, and family rejection. The stigma preoccupation factor was formed using the three individual items of the Acceptance Concerns subscale of the LGBIS. Remaining factors were formed using item-to-construct parceling (Little et al., Citation2002), with further adjustment so that items with opposing skew/kurtosis were balanced across parcels (Hau & Marsh, Citation2004). As long as scales are unidimensional, parceling can reduce distributional violations, item error variance, and the number of estimated parameters; this increases reliability, parameter accuracy, and power to detect model misfit (Little et al., Citation2002, Citation2013; Rhemtulla, Citation2016). Supplementary Appendix A lists the procedures we used for model identification and setting the factor scales.

Our structural equation model included a-priori correlations between the three proximal stress factors; between social anxiety and inhibition; and between social and emotional loneliness. These associations were specified by covarying the factors’ residual error terms, given that structural equation modeling does not allow endogenous latent variables to directly covary (Kenny, Citation2011). For all groups, the model was adjusted for sexual orientation, ethnoracial identity, region, and urbanicity. To maximize degrees of freedom and minimize convergence errors, we omitted the control variable dummy code for the small number of respondents from North Africa and the Middle East (n = 66). Age was added as a continuous control variable; this was done even in the age group models in order to account for within-group age variation. Gender was added as a control in the age group models only. As with mean comparisons, income and partner status were not controlled because they are likely mediators between marginalization and loneliness.

Preliminary Model Evaluations

Using AMOS 29 (Arbuckle, Citation2022), we first evaluated the fit of the measurement, structural, and composite models separately for each group (O’Boyle & Williams, Citation2011). We assessed model fit using consensus of several indices. Good fit is suggested by a non-significant chi-square along with values of ≥ .95 for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI, also known as the Non-Normed Fit Index), and ≤ .05 for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Schermelleh-Engel et al., Citation2003). Given that chi-square is often significant with very large samples and degrees of freedom (i.e., oversensitive to trivial misfit) and the fact that other global fit indices can mask localized misfit, we also inspected standardized residual covariances, flagging values greater than 2.58 (i.e., p < .01; Brown, Citation2015). In addition, we flagged modification indices that were notably larger than others. We calculated robust standard errors and 95% confidence intervals using bias-corrected bootstrapping, with 5,000 samples from the original dataset. We used maximum likelihood estimation for preliminary model evaluation and all subsequent analyses.

Multiple Group SEM Invariance Testing

To test for age and gender differences in the overall fit as well as structural parameters of our loneliness model, we used multiple group SEM. As a first step, we verified measurement invariance using a series of nested models, with Models A through D imposing equality constraints on measurement parameters (i.e., equal factor structures, loadings, and full/partial measurement intercepts across groups). Measurement invariance is necessary not only to compare structural equation models across groups, but also to compare observed and latent mean scores (Steinmetz, Citation2013). After testing for measurement invariance, we assessed structural invariance by imposing equality constraints on regression paths between factors (Models E through G). Supplementary Appendix A provides detailed descriptions of each model.

Guidelines for Invariance Testing

A nested model was considered invariant if most of its fit indices were good and not substantially worse than the fit of the prior model. As a preliminary assessment, a non-significant chi-square difference between two models was indicative of invariance. However, with large sample sizes, chi-square can be significant even in the presence of minor group differences. Therefore, we also computed RMSEAd, which is the RMSEA for the chi-square difference test and its degrees of freedom (Savalei et al., Citation2023). Unlike chi-square, RMSEAd tends to stabilize with increasing sample size. It is also more informative than ∆RMSEA, ∆CFI, ∆TLI, and ∆RSMR, which are often insensitive to violations of invariance (Beribisky & Hancock, Citation2023; Savalei et al., Citation2023). RMSEAd ≤ .05 suggests that a nested model fits closely to the previous model. As the difference between two models increases, so does RMSEAd. A 90% confidence interval is also computed for this value.

In addition to RMSEAd, we examined the Akaike Information Criterion and Browne-Cudeck Criterion (BCC). The model with lower AIC and BCC was preferred, with BCC imposing a greater penalty for less parsimonious models. Burnham and Anderson (Citation2002) suggest that a decrease of 4 to 7 points in AIC indicates a “substantially” better model, and a decrease of 10+ points indicates a “considerably” better model. Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values were not reported as they are not available when conducting multiple group analyses in AMOS. To identify non-invariant intercepts and structural paths, we used these fit statistics as well as modification indices (see Supplementary Appendix A).

Given that unbalanced sample sizes can reduce the ability to detect violations of invariance (Yoon & Lai, Citation2018), we repeated all analyses after equalizing group sizes (i.e., selecting random samples of cases to match the size of the smallest age and gender groups). However, we report main results using the full sample in order to provide more stable parameter estimates.

Results

Age Group Comparisons

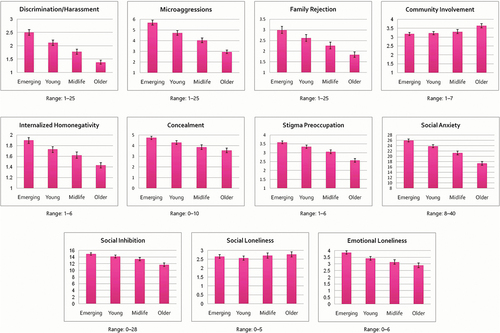

Supporting Hypothesis 1, the adjusted observed means for all forms of marginalization and proximal stress, as well as social anxiety and inhibition, were lower within each successive age group, from emerging to older adults ( and Table S5). The standardized observed and latent mean differences between emerging and young adults, as well as between young adults and midlife adults, were in the small-medium range (Tables S6 and S13). Standardized differences between midlife and older adults were larger, with some in the medium range, although this was likely influenced by the broader age gap between these two groups. Results for loneliness provided mixed support for Hypothesis 1: emotional loneliness was lower within each successive age group (small effect) but social loneliness was relatively stable (; Tables S5, S6, and S13). Inconsistent with Hypothesis 2, community involvement was fairly similar across the first three age groups; however, there was a more notable increase in the older group (small-medium effect; ; Tables S5, S6, and S13). Supplementary analysis with a subset of respondents aged 65–88 (n = 283, Mdn = 68) confirmed the age trends noted above, as these adults reported the least sexual orientation marginalization, proximal stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and emotional loneliness, plus the most community involvement. (For comparative purposes, unadjusted means and unadjusted standardized group differences are shown in Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 2. Age differences in adjusted means with robust 95% confidence intervals. Note: For everyday discrimination/harassment, microaggressions, family rejection, and internalized homonegativity, 95% CIs may not be symmetric around the mean because they were back-transformed from log-10 values. All group means were adjusted for gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnoracial identity, geographic region, and urbanicity.

In support of Hypothesis 3, measurement and structural models had excellent fit for each age group (CFI ≥ .98; TLI ≥ .96; RMSEA/SRMR ≤ .03; Tables S7 and S8). All indicators loaded onto their respective factors, and all factors were related to one another as expected. Residual covariances were small and evenly distributed, indicating minimal local misfit. In each group, RMSEA based solely on the structural model (i.e., structural and control variable paths) was strong (≤ .02), confirming that the good fit of the full SEM model was not due simply to the good fit of the measurement model. This also suggested that the model was robust even when accounting for other demographic differences. For each group, the factor loadings for items, scales, and parcels were similar in both the measurement and structural models, indicating that the addition of structural and control variable paths did not affect the integrity of the measurement model. Most factor associations were significant and in similar directions across age groups (Table S9).

Multigroup fit indices confirmed the presence of configural and metric invariance, and partial scalar invariance, allowing us to compare observed means, latent means, and structural paths across age groups (CFI/TLI ≥ .98; SRMR/RMSEA/RMSEAd ≤ .02; Table S10). The intercepts for several minority stress items, scales, and parcels differed across groups, suggesting some degree of biased responding for similar levels of an underlying factor/trait (see notes for Table S10). However, group differences in latent means did not change much when accounting for non-invariant intercepts (Table S13); this reassured us that both observed and latent mean differences were not substantially influenced by biased responding. Results of configural, metric, and scalar invariance analyses were similar when using equalized sample sizes (not reported); this supplementary analysis did not reveal any additional non-invariant intercepts.

Age differences in the structural weights between latent variables were tested by comparing Models E, F, and G. The fully constrained structural Model F exhibited excellent fit on its own and fairly close fit to the unconstrained Model E (Table S10). This suggested that the structural paths were likely similar in magnitude between age groups, which was inconsistent with Hypothesis 4. Modification indices and formal invariance tests for each structural path revealed only two meaningful differences across age groups. First, there was a significant multigroup difference in the association between community involvement and sexual orientation marginalization (∆χ2 [df = 3] = 59.22, p < .001; RMSEAd = .098). As shown in , and consistent with Hypothesis 5, there was a downward trend in this association across groups, with the association notably higher for emerging adults (significant pairwise comparisons: emerging adults versus others, p < .001; young versus older adults, p = .010). There was also a significant multigroup difference in the association between community involvement and internalized homonegativity (∆χ2 [df = 3] = 30.24, p < .001; RMSEAd = .068). However, in contradiction to Hypothesis 6, there was a slight downward trend in this association across successive age groups (significant pairwise comparisons: emerging versus midlife, p = .039; emerging versus older, p < .001; young versus older, p < .001; midlife versus older, p = .011).

Table 2. Total and direct associations from final partially invariant multigroup Model G.

These two structural differences remained even after constraining control variable paths to equality across groups (note that these latter constraints were for robustness checks only; they were not retained in the final model as we felt they were overly restrictive). Results were also similar when using equalized sample sizes (not reported); this supplementary analysis did not reveal any additional non-invariant intercepts. With the constraints for these two paths freed, the revised partially invariant Model G exhibited excellent fit (CFI = .98; TLI = .97; SRMR = .018; RMSEA = .012, 90% CI [.012, .013]). In addition, despite a significant chi-square difference, RMSEAd indicated that Model G fit similarly to the unconstrained Model E, while AIC and BCC favored Model G for its balance between fit and parsimony (∆χ2 [df = 87] = 141.82, p < .001; RMSEAd = .018, 90% CI [.017, .018]; ∆AIC = −32.18; ∆BCC = −36.77). Therefore, we accepted Model G as our final multigroup age model.

Considering direct and indirect associations plus covariates (not constrained across age groups), Model G explained between 26−27% of variance in social loneliness and 31−36% of variance in emotional loneliness, depending on the age group. The model also explained 18−22% of variance in internalized homonegativity, 14−22% in concealment, 30−34% in stigma preoccupation, 24−26% in social anxiety, and 12−14% in social inhibition.

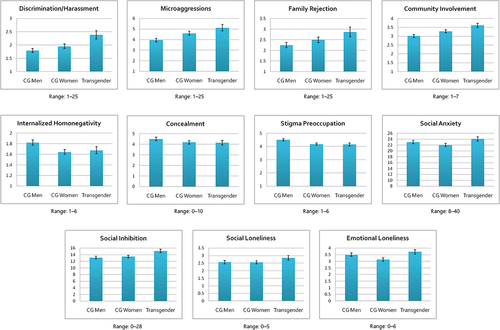

Gender Group Comparisons

The adjusted observed and latent means for all three forms of marginalization were modestly higher among cisgender women versus men (; Tables S5, S6, and S13). These findings contradicted Hypothesis 7, which predicted higher levels of marginalization among cisgender men. However, in support of Hypothesis 7, cisgender men reported higher levels of proximal stress (i.e., internalized homonegativity, concealment, stigma preoccupation) as well as social anxiety and emotional loneliness compared to cisgender women (in a supplementary analysis, the gender difference in emotional loneliness persisted even after accounting for men’s greater likelihood of being single). These effects were fairly small with the largest being for internalized homonegativity and emotional loneliness.

Figure 3. Gender differences in adjusted means with robust 95% confidence intervals. Notes: CG = cisgender. For everyday discrimination/harassment, microaggressions, family rejection, and internalized homonegativity, confidence intervals may not be symmetric around the mean because they were back-transformed from log-10 values. All group means were adjusted for age (continuous), sexual orientation, ethnoracial identity, geographic region, and urbanicity.

In support of Hypothesis 8, transgender individuals reported higher levels of sexual orientation marginalization than both cisgender men (medium difference) and cisgender women (small-medium difference). They also reported more social anxiety, inhibition, and both forms of loneliness; these differences were in the small-medium range, with more pronounced disparities for social anxiety and emotional loneliness when comparing transgender individuals to cisgender women. Transgender individuals were also lower in proximal stress compared to cisgender men (small effect); however, there were no meaningful differences in proximal stress between transgender individuals and cisgender women.

Consistent with Hypothesis 9, cisgender men were lower in community involvement than cisgender women (small-medium effect). Transgender individuals were more involved than both cisgender men (medium effect) and women (small-medium effect).

Supporting Hypothesis 10, the measurement and structural models had excellent fit for each gender group (CFI ≥ .98; TLI ≥ .97; RMSEA/SRMR ≤ .03; Tables S7 and S8). All indicators loaded onto their respective factors, and all factors were related to one another as expected. Standardized residual covariances were small and evenly distributed, indicating no areas of substantial local misfit. In each group, RMSEA based solely on the structural component of the model was strong (≤ .03), indicating that good fit of the structural model was not due simply to good fit of the measurement model. This also suggested that the model was robust even when accounting for other demographic differences. For each group, the factor loadings for items, scales, and parcels were similar in both the measurement and structural models, indicating that the addition of structural and control variable paths did not affect the integrity of the measurement model. Most of the factor associations were significant and in similar directions across all groups (Table S9).

Multigroup fit indices for the measurement models indicated configural and metric invariance, and partial scalar invariance, allowing us to compare observed means, latent means, and structural paths across gender groups (CFI/TLI ≥ .99; SRMR/RMSEA/RMSEAd ≤ .02; Table S11). Intercepts for several items, scales, and parcels differed slightly between groups, suggesting some biased responding (see notes for Table S11). However, group differences in latent means did not change much when accounting for non-invariant intercepts (Table S13); this reassured us that neither the observed nor latent mean differences were substantially influenced by biased responding. Results of configural, metric, and scalar invariance analyses were similar when using equalized sample sizes (not reported); this supplementary analysis did not reveal any additional non-invariant intercepts.

Gender differences in structural weights between latent variables were tested by comparing Models E, F, and G. The fully constrained structural Model F had excellent fit, both independently and in comparison to the unconstrained structural baseline Model E (Table S11). This suggested that all or most of the structural paths were similar in magnitude between gender groups, inconsistent with Hypothesis 11. There were only two notable differences. First, there was a significant multigroup difference in the association between marginalization and concealment (∆χ2 [df = 2] = 10.58, p = .005; RMSEAd = .040). As shown in , this association was modestly stronger for cisgender women compared to cisgender men (p < .001). Second, there was a significant multigroup difference in the negative association between community involvement and social loneliness (∆χ2 [df = 58] = 6.30, p = .043; RMSEAd = .029). In partial support of Hypothesis 12, this association was stronger among transgender sexual minorities compared to cisgender men (p = .014) and cisgender women (p = .027).

These two gender differences remained even after constraining control variable paths to be equal. Results were similar when using equalized sample sizes (not reported), which did not reveal any additional non-invariant structural paths. With the constraints for these two paths released, the revised, partially invariant Model G was an excellent fit (CFI = .98; TLI = .97; SRMR = .016; RMSEA = .015, 90% CI [.014, .015]). Moreover, RMSEAd indicated that Model G fit similarly to the unconstrained Model E, and AIC and BCC favored Model G for its balance between fit and parsimony (∆χ2 [df = 58] = 61.86, p = .34; RMSEAd = .005, 90% CI [.004, .006]; ∆AIC = −54.15; ∆BCC = −57.37). Therefore, we accepted Model G as our final multigroup gender model.

Considering both direct and indirect associations plus covariates (not constrained across groups), Model G explained between 25−31% of variance in social loneliness and 34−37% of variance in emotional loneliness, depending on the gender group. The model also explained 22−26% of variance in internalized homonegativity, 18−23% in concealment, 38−39% in stigma preoccupation, 31−38% in social anxiety, and 13−22% in social inhibition.

Discussion

Age Group Comparisons

Our results paint an interesting picture of the relationship between age, minority stress, and loneliness. In a large, diverse sample of sexual minorities from 85 countries, we found that sexual orientation marginalization and proximal stress were lower among successive age groups, consistent with Hypothesis 1. The general pattern and magnitude of these findings align with studies from individual countries and regions (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2023; CBRC, Citation2017; EU, Citation2020; Frost et al., Citation2022; Leonard et al., Citation2012; Lyons et al., Citation2012; Meyer et al., Citation2021; Rice et al., Citation2021; Vale, Citation2023; Vale & Bisconti, Citation2021). Notably, despite increasing acceptance and rights in the past few decades, LGBTQ emerging adults still experience the most marginalization and proximal stress compared to other generations.

Our findings are generally consistent with life course transitions. While emerging sexual minority adults are at heightened risk for minority stress, this may improve as they become more comfortable with their sexual orientation, transition to more accepting environments, develop greater social confidence, and form broader networks and intimate relationships. Thus, consistent with Hypothesis 1 and other studies, we found that social anxiety and emotional loneliness were less prevalent with age, with small-medium effects (Hughes et al., Citation2023; Mahon et al., Citation2022). In contrast, social loneliness appeared to be relatively stable. It may be that these life course transitions have less impact on social loneliness, or perhaps there are countervailing influences. For example, relationships with friends and extended family can fade as people devote more time to careers and intimate partners (Musick & Bumpass, Citation2012; Sarkisian & Gerstel, Citation2016). In addition, greater LGBTQ community involvement over time may not fully offset weaker kinship ties (Green, Citation2016), the reduction of social networks after retirement, and the strain on relationships that can occur when relying on LGBTQ friends for caregiving (Hsieh & Liu, Citation2021). And although LGBTQ social networks might expand over time, intraminority stress may limit how satisfying they are (Pachankis et al., Citation2020; Parmenter et al., Citation2021).

Maturational changes may also contribute to the age trends we observed. For instance, due to improvements in social cognition, older adults might be less likely to interpret others’ neutral or ambiguous actions as discriminatory. Furthermore, older adults tend to exhibit greater emotional stability and enhanced coping skills, prioritize the quality of relationships over quantity, and understand that loneliness is not necessarily permanent (Carstensen, Citation2006; Qualter et al., Citation2015; Robinson & Lachman, Citation2017). These changes are especially relevant for emotional loneliness. Age differences might also be due to younger people’s more frequent use of social media, where experiences of marginalization and loneliness are often shared; this might amplify vigilance toward discrimination and contribute to vicarious marginalization.

For midlife and older adults, it appears that life course transitions and maturational changes can offset some of the adverse impact of growing up in a less accepting era and enduring the emotional toll of AIDS. However, our study’s oldest group had a median age of 58; the older sexual minorities from the pre-liberation era might not be fairing as well. Still, when examining the smaller subset of people aged 65−88 (median age of 68), we found that they exhibited the least minority stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness, similar to findings by Hughes et al. (Citation2023) and Vale (Citation2023). However, some research involving people who are even older has found greater internalized homonegativity and less sexual orientation disclosure among those aged 80+ versus 50–79, suggesting persistent effects of stigma among pre-liberation sexual minorities (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2015; Jenkins Morales et al., Citation2014; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). Global research with larger, more representative samples spanning wider age ranges would provide more insight about minority stress across the life course.

Partially consistent with Hypothesis 2, we observed relatively uniform levels of LGBTQ community involvement across the first three age groups, with a more notable increase in the oldest group. This contrasts with some studies indicating slightly lower feelings of community belonging and connectedness among older cohorts (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2015; Meyer et al., Citation2021). Although we found that older adults are more engaged with the LGBTQ community, it is possible that their sense of connection to it might be weaker. This may be due to mainstream LGBTQ spaces catering more to young people, as well as real or perceived marginalization from younger peers and a resulting sense of internalized ageism (Armengol & Varela-Manograsso, Citation2022; Cronin & King, Citation2014; Higgins et al., Citation2011; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Wight et al., Citation2015). These reasons may explain why, despite higher levels of community engagement, the oldest group did not experience less social loneliness.

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, we found that the overall structure of our loneliness model applied equally well to all age groups. Yet, despite lower levels of minority stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and emotional loneliness across age groups, the strength of relationships between the factors in our loneliness model were mostly consistent. While not supporting Hypothesis 4, this observation underscores the model’s robustness across age, suggesting that the dynamics between minority stress and loneliness are likely universal. Although experiences of minority stress may decline with age, those who do encounter it seem to be impacted to a similar extent, regardless of their age or growing up in a more accepting social climate.

Only two deviations to these age-invariant associations were observed. First, in partial agreement with Hypothesis 5, LGBTQ community involvement seemed to have a substantially greater impact on experiences of marginalization among emerging and young adults, in comparison to midlife and older adults. This difference is probably attributable to the more publicly visible nature of younger people’s community participation, which not only may reveal their sexual orientation to others but can increase their exposure to vicarious marginalization (Bissonette & Syzmanski, Citation2019). It is also possible that younger people who experience marginalization are more inclined to seek support from the LGBTQ community, which they may find more welcoming than older people do. Second, in contradiction to Hypothesis 6, there was a slight decrease in the association between community involvement and internalized homonegativity across successive age groups. This could be due to the greater stigma faced by earlier generations, which could make the benefits of community involvement less effective. With this exception, we found no other age-related differences in the expected protective influence of community involvement. While inconsistent with Hypothesis 6, this suggests that community involvement, on the whole, remains beneficial across the life course, despite some potential costs.

Gender Group Comparisons

Contrary to Hypothesis 7, we found that sexual orientation marginalization was modestly higher among cisgender women than men. While this finding aligns with some previous research (e.g., Bayrakdar & King, Citation2023), it is unexpected considering the widespread stigma around homosexuality and gender nonconformity in men (Bettinsoli et al., Citation2020; Thoma et al., Citation2021). A possible explanation is that the men in our sample who were noticeably gender nonconforming might have been more likely to identify as transgender rather than cisgender (Toomey et al., Citation2010). Additionally, cisgender women might perceive or focus on marginalization more frequently due to heightened awareness of subtle social cues, or because of a predisposition to rumination (Johnson & Whisman, Citation2013). Nevertheless, these findings should not overshadow the fact that cisgender sexual minority men are at greater risk for more severe outcomes like violence (Bayrakdar & King, Citation2023; Hill et al., Citation2020; Katz-Wise & Hyde, Citation2012). This may explain why, in support of Hypothesis 7, cisgender men reported somewhat more proximal stress than cisgender women. Aware of the potential for violence or other severe reactions from others, they may become preoccupied with stigma, internalize it more readily, and conceal their sexual orientation more frequently.

Also in line with Hypothesis 7, cisgender men were slightly more socially anxious than cisgender women, perhaps due to greater proximal stress and fear of rejection in sexual or romantic contexts (e.g., due to appearance). This was inconsistent with a study which found that cisgender women were more socially anxious, although that study was based on a single country (Mahon et al., Citation2023). Higher levels of proximal stress and social anxiety may partly explain why cisgender men also experienced somewhat more emotional loneliness than cisgender women (a finding that held even when accounting for gender differences in partner status). Although one study noted a similar gender disparity in loneliness (Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019), three others found no appreciable differences (Doyle & Molix, Citation2016; Hughes et al., Citation2023; Kuyper & Fokkema, Citation20100).

Supporting Hypothesis 8, we found that sexual orientation marginalization was most pronounced among transgender sexual minorities. This may stem from the common implicit assumption that gender atypicality signals a non-heterosexual orientation (James et al., Citation2016, p. 131; Rule, Citation2017). In addition, experiences of transgender antagonism might increase vigilance for marginalization related to sexual orientation. Yet consistent with Hypothesis 8 and prior research, transgender individuals reported modestly lower levels of proximal stress than cisgender men, despite experiencing more sexual orientation marginalization (Thoma et al., Citation2021; Timmins et al., Citation2020). This could be attributed in part to crisis competence: facing increased marginalization due to their perceived sexual orientation, transgender sexual minorities might cope by cultivating a stronger sense of pride, being more open about their sexuality, and feeling more comfortable to seek support from the LGBTQ community. However, we found no disparity in proximal stress between transgender individuals and cisgender women. This may be due to the fact that three-quarters of the transgender sample consisted of individuals assigned female at birth; they might encounter fewer negative reactions than those assigned male at birth (James et al., Citation2016), leading to similar levels of proximal stress as cisgender women.

Yet despite possible benefits of crisis competence, transgender sexual minorities still experienced more social anxiety, inhibition, and social and emotional loneliness than cisgender sexual minorities, consistent with other studies (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2011; Mahon et al., Citation2023; McDanal et al., Citation2023).

Supporting Hypothesis 9, transgender sexual minorities were the most involved in the LGBTQ community, followed by cisgender women and then men, generally consistent with studies from the US, Australia, and Israel (Hill et al., Citation2020; Houghton & Quartey, Citation2020; Leonard et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Shnoor & Berg-Warman, Citation2019). Given the greater stigma and isolation experienced by transgender sexual minorities, they may be more inclined to seek support from their peers. Supporting this idea, research from Australia found that non-binary sexual minorities perceived a greater benefit from LGBTQ community involvement compared to other sexual minorities (Hill et al., Citation2020). Additionally, among Australian sexual minorities who were more involved in the LGBTQ community, transgender individuals and cisgender women exhibited greater resilience and less psychological distress than cisgender men (Leonard et al., Citation2015). However, there may be age-related gender differences: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. (Citation2014) found that older transgender sexual minorities, despite being more active in the LGBTQ community and having larger social networks than their cisgender peers, reported lower levels of social support and sense of community belonging. This may be due to transgender stigma within the LGBTQ community or a sense of having less in common with cisgender sexual minorities.

Consistent with Hypothesis 10, we found that the overall structure of our loneliness model applied equally well to all three gender groups. However, in contrast to gender differences in the prevalence of minority stress, social anxiety, inhibition, and emotional loneliness, the strength of associations between the factors in the loneliness model was very similar across groups. While inconsistent with Hypothesis 11, this provides further support that the proposed mechanisms linking minority stress and loneliness are likely universal. There was only one notable group difference: the association between marginalization and concealment was modestly stronger for cisgender sexual minority women than men. It is possible that cisgender women find it easier to “pass” as heterosexual, considering that gender nonconforming women are less likely to be perceived as lesbian or bisexual compared to gender nonconforming men (Sanborn-Overby & Powlishta, Citation2020).

Finally, in partial support of Hypothesis 12, the association between community involvement and social loneliness was stronger for transgender compared to cisgender sexual minorities. This suggests that they experience greater support from their peers and rely on them more for a sense of connection. However, despite greater community involvement and its putative protective effect against loneliness, transgender sexual minorities still reported more social and emotional loneliness compared to their cisgender peers; this underscores the significant adverse impact of stigma in this population.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. We created age groups in an effort to reflect developmental and generational differences among sexual minorities globally (Bitterman & Hess, Citation2021; CBRC, Citation2017; Hammack et al., Citation2018; Ipsos, Citation2021; Meyer et al., Citation2021). However, countries differ in unique cohort influences, developmental milestones, and the pace of LGBTQ acceptance (Hammack et al., Citation2018). Although we controlled for broad geographic regions when examining age trends, future research should examine country-specific age groups/cohorts.

Sexual orientation was assessed using self-identity labels, which may not necessarily correspond with actual sexual or romantic attractions. However, we observed a high concordance between self-identity and Kinsey-type scale scores. Moreover, self-identification may have a greater impact on minority stress than sexual attraction per se. Those who consider themselves sexual minorities or publicly disclose as such may experience more marginalization, social anxiety, and loneliness, regardless of their sexual or romantic attractions.

Some of our subgroups differed substantially on demographic characteristics. For example, nearly three-quarters of older adults identified as men. In addition, three-quarters of transgender individuals were assigned female at birth, with the majority identifying as non-binary. Although efforts were made to control for gender identity and other key demographic variables, care should be taken when generalizing the results to broader populations. Moreover, there were not enough respondents to explore important subgroup differences (e.g., transgender individuals assigned male versus female at birth); this would help identify which groups are at greatest risk for minority stress and loneliness, and elucidate the relative influence of sex versus gender identity on these outcomes.

Two-thirds of our respondents were fairly open about their sexual orientation, and many were at least somewhat involved in the LGBTQ community. Thus, the current sample does not reflect the experience of sexual minorities who have same-gender desire or engage in same-gender sexual behavior, but who do not identify as LGBTQ. These individuals might experience less marginalization but perhaps more proximal stress (e.g., internalized homonegativity) and loneliness.

Although this study had a wider age range than others, it is likely that our recruitment strategy resulted in the underrepresentation of “older-old” adults who are not active on social media but who may be lonelier than others. Similarly, there could have been a survival or selection bias, such that those with age-related health issues due to cumulative minority stress or loneliness did not participate in our study.

We examined past-year marginalization to minimize recall bias and because recent marginalization appears to have a stronger effect on well-being than more distant marginalization (Ejlskov et al., Citation2020; Lyons et al., Citation2021). Future studies could compare the relative impact of past versus recent marginalization on loneliness across age as well as gender groups. Indeed, Hughes et al. (Citation2023) found that loneliness was associated with lifetime marginalization in men, but recent marginalization in women.

We cannot be certain if greater marginalization, social anxiety, inhibition, and loneliness among transgender sexual minorities is due to sexual orientation, gender identity, or both. Even though the wording of our scales focused on sexual orientation and not gender identity, future studies should examine the relative contributions of marginalization due to sexual orientation versus gender identity.