ABSTRACT

Adults entering college, especially autistic individuals, may have a higher likelihood of unwanted or distressing sexual experiences. Additionally, autistic adults appear to endorse dissatisfying sexual education experiences and difficulties with consent cues. The current mixed-methods study examined the types of consent cues college students rely on and potential barriers to seeking sexual consent. We combined data from two studies of undergraduate students: 1) an in-person cross-sectional study exploring conceptualizations and interpretations of consent in autistic and non-autistic young adults (n = 30), and 2) an online, short-term longitudinal study examining predictors of mood concerns in neurodiverse students transitioning into their first semester at 4 northeastern United States university systems in Fall 2022 and 2023 (n = 230). In-person participants completed a semi-structured interview asking about consent expression and interpretation. Participants from both studies completed self-report surveys measuring autistic traits, attitudes and perceptions toward sexual consent, and sexual education history. Qualitative analysis suggested students preferred to rely on explicit verbal consent, but felt they were unusual for doing so. In contrast, quantitatively, students across both studies expressed comfort with explicit verbal consent, to a high and similar degree. Further research may benefit from investigating differences between young adults’ perceived and actual sexual consent preferences of peers, with attention to neurodivergent individuals.

Introduction

Sexual trauma is an important and often-identified risk factor for long-lasting problems, including many psychiatric and physical health concerns (Graham et al., Citation2021; K. Rothman et al., Citation2021; Waigandt et al., Citation1990). There are few environments where these concerns are more salient than an undergraduate campus, especially during the transition to college. In the general population, the first semester of college is a known period of heightened sexual assault risk, particularly for women, often referred to as the “red zone” (Kimble et al., Citation2008). Many contributors to this elevated risk of sexual trauma have been proposed, including the increased presence of alcohol, substance use, and casual sexual encounters in college, compared to other periods of life (Lindo et al., Citation2018; Mellins et al., Citation2017). While accurate prevalence has been difficult to calculate due to shame and fear surrounding reporting, the rate of sexual assault in undergraduates has been estimated to be approximately 20% (Mellins et al., Citation2017; Rosenberg et al., Citation2019) and appears to be associated with numerous declines in wellbeing. In college women, negative consequences of sexual assault have included nearly immediate decreases in academic functioning, as well as greater psychological difficulties and anxiety symptoms nine years later (K. Rothman et al., Citation2021). These negative health effects seem to be particularly salient for gender and sexual minority students, though sexual violence increases the risk of depression and PTSD symptoms for college students of all genders and sexual orientations (Kammer-Kerwick et al., Citation2021).

Existing – though limited – research suggests the risk of unwanted, distressing, and/or traumatic sexual experiences may be higher for autistic adults than their peers (Brown et al., Citation2017; Dike et al., Citation2022; Pecora et al., Citation2019; Sevlever et al., Citation2013; Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018). This risk may be especially high for autistic women, who appear to show increased risk of engagement in unwanted sexual behaviors compared to their non-autistic peers (Pecora et al., Citation2019). These unwanted sexual experiences likely relate to negative health outcomes in autistic people, similar to (or possibly even worse than) what has been observed in the general population: While the longitudinal physical health concerns of autistic adults who have experienced sexual trauma have not been clearly studied, autistic individuals appear to be at greater risk than their non-autistic peers of developing PTSD symptoms following traumatic events (Rumball et al., Citation2020), as defined by the DSM-5, such that the event involved “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (American Psychiatric Association Ed., Citation2013). However, autistic participants also commonly experienced PTSD symptoms following events such as bullying, bereavement, and social difficulties that would not meet traditional DSM-5 criteria for trauma (Rumball et al., Citation2020). Thus, not only do autistic adults appear to endorse high levels of trauma and trauma-related symptomatology, they also may be at heightened risk of developing PTSD symptoms following a wider range of distressing experiences.

In addition to the elevated risk of autistic adults being victims of traumatic events, some research has suggested that autistic individuals may also be more likely to be perpetrators of sexual violence or misconduct (Dike et al., Citation2022; Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018). For example, in a study of parent reports for 63 individuals ages 13–36 (n = 25 autistic), autistic individuals were reported by parents to engage in socially inappropriate behavior toward romantic interests significantly more often than non-autistic individuals (Stokes et al., Citation2007). This behavior included things like inappropriate touching, unwanted sexual comments, engaging in stalking behavior, threatening their romantic interest, and threatening self-harm if interest was not reciprocated. Although greater research is needed in this area – particularly to establish differences in actual rates of sexually inappropriate behaviors, as opposed to differences in parent or teacher awareness of said behavior – this emerging body of literature raises concern.

Despite this emerging picture that autistic students are at heightened risk of both sexual assault victimization and perpetration (Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018), there has not been sufficient research to understand potential causal factors or intervention opportunities. One potential theory for this heightened victimization and perpetration risk is that autistic and non-autistic students may have different understandings of sexual consent cues, possibly due to differences in sexual education experiences and comfort with navigating neurotypical communication norms. Autistic students are less likely to receive sexual education and report feeling that the sexual education they do receive is inadequate (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Hancock et al., Citation2017). Prior literature has also indicated that communication between autistic and non-autistic individuals tends to be more difficult than within-neurotype communication (Chaidi & Drigas, Citation2020; Crompton et al., Citation2020; Cummins et al., Citation2020; Sheppard et al., Citation2016; Ying Sng et al., Citation2018). The precise differences in communication style between autistic and non-autistic students have been difficult to determine – as findings are often contradictory, and there is significant individual variation (Ying Sng et al., Citation2018). Some findings have suggested that there are differences in conversational style, such that autistic individuals may be less responsive to conversational bids and may have a more perseverative conversational style (Ying Sng et al., Citation2018). It is possible that these differences in conversational norms and expectations could cause difficulties in interpreting and communicating something as complex and nuanced as sexual consent across neurotypes, especially if sexual education is not providing students with a “shared language” on how to navigate sexual consent.

Although evidence suggests most sexual assaults are not due to miscommunication of consent cues in the general population and instead are likely related to coercion or ambivalence (Fenner, Citation2017), there are particular populations that prefer or may find additional benefit from the use of explicit verbal consent. For example, fears of misunderstanding nonverbal consent cues seem to persist in some neurodivergent populations (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015). Some autistic participants have expressed that they miss out on romantic opportunities due to not picking up on nonverbal cues; others have reported incorrectly pursuing romantic or sexual encounters that are not desired, for the same reason.

Explicit verbal consent may be one tool to provide a “shared language” to assist in the interpretation and expression of sexual consent cues, without reliance on more unclear behavioral cues. Explicit verbal consent involves clear verbal agreement (e.g., saying “yes”) to specific sexual activities (Wills et al., Citation2021). In addition to improved clarification of interests and comfort levels, explicit verbal consent practices have also been shown to relate to improved sexual satisfaction (Javidi et al., Citation2023). Existing data suggests that most individuals use a combination of verbal and nonverbal behaviors to interpret and express sexual consent (Beres, Citation2014; Fenner, Citation2017; Hickman & Muehlenhard, Citation1999). However, comfort levels with each do vary.

One common concern is that explicitly discussing sexual consent may be seen as unattractive by potential partners or “ruin the mood” (Gibson, Citation2016; Piemonte et al., Citation2022). This may be related to sexual scripts – narratives, influenced by social or cultural norms, that guide expectations for sexual encounters (Piemonte et al., Citation2022): In the United States, mainstream media and pornography often do not highlight consent whatsoever or may indicate a reliance on nonverbal indicators of consent (Piemonte et al., Citation2022). For example, Willis et al. (Citation2019) found that 50 of the best-selling pornographic films in 2015 presented more reliance on implicit and nonverbal consent cues than verbal consent cues (Willis et al., Citation2019). Many individuals define pornography as a primary source of sexual education and knowledge of consent cues (Martellozzo et al., Citation2020; E. F. Rothman & Adhia, Citation2016), and thus these representations in pornography and broader entertainment media likely serve as direct models for viewers’ behavior in the future – as well as contributing to scripts like “Explicit Verbal Consent Isn’t Natural” and “You Should Get ‘Swept Up’ In The Moment” (Willis et al., Citation2019).

These cultural scripts are also influenced by conventional gender roles, including hegemonic masculinity. Prior literature has revealed gender differences in use of and comfort with explicit verbal consent. Common social scripts in the United States consider men to be the initiator in heterosexual sexual encounters – often also pressuring women to be compliant in order to fill gender expectations or build closeness with their male partner (Fenner, Citation2017). These heterosexual scripts thus suggest men are the ones who push or pursue sex, while women are portrayed as sexually reluctant (Bockaj & O’Sullivan, Citation2023). Pressures on men to appear dominant in sexual encounters may contribute to decreased verbal communication; under this theory, it is suggested that if a male verbally communicates during sex, he risks being perceived as unsure or going against ideals of masculinity (Foubert et al., Citation2006; Humphreys, Citation2004).

However, these perspectives are by no means unanimous. The use of explicit verbal consent appears to be becoming more acceptable, even preferable, among young adults, potentially as a result of affirmative consent initiatives and campaigns to advertise how verbal consent can be “sexy” (Beres, Citation2014; Graf & Johnson, Citation2021). Despite the concerns noted previously that many individuals believe that sexual consent discussion would “ruin the mood” of an encounter, some evidence suggests this is not the case. For example, Piemonte et al. (Citation2022) found participants believed erotica in which participants sought verbal consent was just as sexy, if not sexier, than erotica without verbal consent. Similarly, in a vignette study, no differences were found in character enjoyment and sexiness of the situation between enthusiastically expressed verbal or nonverbal consent (Gibson, Citation2016; both conditions were regarded significantly more favorably than when consent was expressed without enthusiasm).

Thus, it is apparent that there are distinct narratives around sexual consent: on one hand, there may be pressure to follow a social script that prioritizes power associated with masculinity and an absence of verbal communication or opportunity to dissent. On the other hand, there is a new push for enthusiastic verbal consent and an emphasis on communication about consent as sexy. Given that undergraduates are likely learning about sexuality and consent from a variety of sources in their life – including formal sexual education, family, peers, media, erotica, and pornography (MacDougall et al., Citation2020) – greater research is needed to understand how young adults make sense of varying scripts and expectations surrounding sexual consent and how they apply these views to their behaviors. This research may be particularly important for undergraduate populations, as students often have an increase in casual sexual activity as they enter college (Lyons et al., Citation2015; Stinson, Citation2010).

The present study sought to explore what types of consent cues or strategies autistic and non-autistic undergraduate students report relying on and the related difficulties they may encounter. In particular, we wanted to learn about participants’ experiences with consent cues, in their own words, to better understand the range of consent expression and interpretation students report, rather than relying on limited options. Furthermore, we sought to compare how beliefs about consent cues may vary by autistic trait levels and between autistic and non-autistic students.

Anticipated Findings

In the current mixed-methods study, we followed an approach of hypothesis generation through qualitative inquiry, followed by hypothesis testing through quantitative methods. We first evaluated qualitative themes related to the types of consent cues participants rely on and associated barriers to seeking sexual consent. We then used these themes to generate quantitative hypotheses to test in a combined sample of participants who participated in an in-person consent-focused study and those participating in a mood-focused online study. Based on qualitative data, we anticipated that students who volunteered to participate in the consent-focused study would feel more able to verbally express and seek explicit consent. We anticipated these students would also have more positive attitudes to discussions of consent and would be less likely to endorse an indirect behavioral approach to consent. We expected that these same patterns would be true of students who were more satisfied with their prior sexual education experiences. In other words, we expected that participants who volunteered freely for a sexual consent study, as well as those reporting greater satisfaction with their formal “sex ed” experiences, would be more likely to endorse explicit verbal consent than those who volunteered for a mood-focused study or were less satisfied with their formal sexual education.

Given the literature previously described (e.g., Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Hancock et al., Citation2017), we anticipated that students who are autistic or who have more self-reported autistic traits (as measured on the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition; SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012) would be less likely to endorse an indirect behavioral approach to consent – meaning they would express less confidence in or reliance on interpretation of nonverbal cues. While we anticipated that students who are autistic or who have more autistic traits may prefer explicit verbal consent over reliance on “body language,” we also hypothesized that, due to poor experiences with sexual education, they would report feeling a greater lack of perceived behavioral control compared to peers with fewer autistic traits. In other words, students with more autistic traits may be less confident in their ability to navigate verbal consent. We expected this effect to be moderated by satisfaction with childhood sexual education experiences.

Method

The present article and analyses are comprised of two studies, conducted among four northeastern, United States public university systems. The first was a cross-sectional, in-person study that explores conceptualizations and interpretations of sexual consent in autistic and non-autistic undergraduate students at a public university in New Jersey (n = 30). This study is titled the Applied Consent Communication Study (ACCS). The second was an online, short-term longitudinal study that explored predictors of mood concerns in students transitioning into their first semester of college at 4 northeastern United States university systems (2 in New Jersey and 2 in New York) in Fall 2022 and 2023 (n = 230). This study is referred to as “2m2×,” due to participants completing 2-minute surveys 2 times per week throughout their semester; however, only baseline measures are relevant for the current analyses. All relevant quantitative self-report measures are shared across the two studies and thus, data were combined. Qualitative findings come solely from the in-person study. Each method of data collection is described in greater detail below.

Method: Study 1 “ACCS”

Participants

In the Applied Consent Communication Study (ACCS), we enrolled 30 young adults to participate in an in-person study, including self-report questionnaires and a semi-structured interview. All participants (n = 30) were undergraduates attending Rowan University during Fall 2023. A total of n = 8 (27%) endorsed a history of a formal autism diagnosis. We attempted to match demographics across our autistic and non-autistic student groups, via one-to-one match. As we enrolled autistic students, we enrolled non-autistic students of a similar age and demographic background, prioritizing gender and sexual orientation when an exact match was not possible. All ACCS participants were required to be between the ages of 18–26 to maximize generational similarity.

For our autistic group, we only enrolled students at this stage in the study who self-reported having a formal diagnosis of autism. Students in our non-autistic group endorsed no history of autism diagnosis or suspicions. Through the eligibility screener, participants also completed the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012), a measure of autistic traits. Eligible non-autistic students had a total T-Score of below 65, which is the lower boundary of the moderate range of scores on this scale and indicates a reduced likelihood of autism.

Procedures

Potential ACCS participants were first asked to complete a brief eligibility screener administered through REDCap, a survey and data management platform designed to collect and store sensitive data (Harris et al., Citation2009, Citation2019). In this screener, potential participants provided their age, gender, sexual orientation, and relevant diagnostic history. They also completed the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012). We used this screener to confirm eligibility and to attempt to match enrolled autistic and non-autistic participants on demographic characteristics, as previously described.

Eligible participants then scheduled a visit to the study team’s lab suite. Following informed consent procedures, participants completed a vignette study activity in which they estimated characters’ likelihood to consent to various sexual activities and then a semi-structured qualitative interview (conducted by the first author for every participant) about expressions of sexual consent and how to navigate determining consent when it is unclear. The semi-structured interview format was flexible, allowing researchers to facilitate participants’ expanding on ideas they wished to discuss further. Thus, all participants had the opportunity to discuss the same core questions, while also allowing for deviations and rapport-building during the interview. Based on focus group feedback, we felt that giving the participants the opportunity to expand freely on their thoughts about consent, while also maintaining some structure and organization would be most appropriate, particularly for autistic participants. Furthermore, a primary purpose of this study was to understand students’ experiences with consent and potentially learn more about support needs and desired future research directions. Therefore, the rich, descriptive nature of qualitative data was considered to be important (Cleland, Citation2017).

Finally, participants completed self-report measures on attitudes toward sexual consent and previous experiences with sex education. The current report focuses on findings from the semi-structured interview and self-report measures, each of which is described further in Measures. This study received approval from the Rowan University Institutional Review Board. Participants received compensation in the form of a $20 visa gift code as thanks for their participation.

We asked participants to reserve one and a half hours for study participation, to allow for a relaxed pace and breaks as needed. However, break requests were rare and study completion was anecdotally noted to often take less than an hour. Several fidget tools were available to all participants throughout participation.

Measures

Participants in ACCS (n = 30) engaged in a semi-structured interview conducted by the first author. They answered open-ended questions about how they express and see others express sexual consent, how they navigate determining consent when it is unclear, and perceived difficulty of navigating sexual consent. Prompting questions included, “What do you think are the most important ways to evaluate consent?,” “How would you figure out whether someone you’re interacting with consents to sexual activity?,” and “Compared to your peers, do you think evaluating sexual consent is easier or harder for you?”

All participants (in both ACCS and 2m2×) completed several self-report measures on REDCap. The Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) was used as a continuous measure of autistic traits (Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012). The SRS-2 is a 65-item self-report scale measuring the presence and severity of social difficulty and repetitive behavior as they relate to autism. The SRS-2 generates a total score as well as scores for each of its five subscales: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and restricted interests and repetitive behavior. The SRS-2 includes clinical ranges of concern for use as an autism screening instrument. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not true, 4 = Almost always true). Example items include “I am much more uncomfortable in social situations than when I am by myself” and “When under stress, I engage in rigid or inflexible patterns of behavior that seem odd to people” (Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012).

The Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R; Humphreys & Brousseau, Citation2010) was used to examine attitudes toward sexual consent, including comfort with verbal explicit consent, use of nonverbal indicators, and beliefs on the importance of confirming consent. This 39-item measure examines attitudes toward consent on a 7-item Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) (Humphreys & Brousseau, Citation2010). Subscales assess (lack of) perceived behavioral control, positive attitude toward establishing consent, indirect behavioral approach to consent, sexual consent norms, and awareness and discussion of consent. Minor revisions were made to this measure to improve readability in our population of interest, following focus group feedback. For example, in the item “I think that consent should be asked before any kind of sexual behavior, including kissing or petting,” petting was replaced with “fondling” due to notes that the word “petting” was confusing.

Current analyses focused on three subscales of the SCS-R: (lack of) perceived behavioral control (11 items), indirect behavioral approach to consent (6 items), and positive attitude towards establishing consent (11 items). The (lack of) perceived behavioral control subscale evaluates how easy or difficult an individual believes it will be to verbally ask for sexual consent, with items such as “I am worried that my partner might think I’m weird or strange if I asked for sexual consent before starting any sexual activity.” Higher scores indicate greater lack of comfort verbally discussing consent, or greater estimated difficulty with consent conversations. In our combined sample, internal consistency of this subscale was strong, Cronbach α = 0.90.

The indirect behavioral approach to consent subscale assesses participants’ tendency to use nonverbal, indirect indicators of consent. It includes items such as “Typically I communicate sexual consent to my partner using nonverbal signals and body language.” In our combined sample, internal consistency was good, Cronbach α = 0.80.

The positive attitude towards establishing consent subscale assesses a participants’ belief in the importance of clear, communicated consent in a variety of sexual relationships, with items such as “I feel that verbally asking for sexual consent should occur before proceeding with any sexual activity.” Internal consistency was excellent, Cronbach α = 0.91.

The Childhood Modeling of Consent Questionnaire (CMCQ) is a series of 11 items created by the first author that together assess how often participants were exposed to conversations about consent as children and how often consent was modeled through basic elements of bodily autonomy. Participants are asked to rate their agreement with a series of items on a 1–5 Likert Scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) following instructions that specify “when we say consent, we mean the freely given verbal or non-verbal communication of a feeling of willingness to engage in an activity.” Example items include “I was encouraged by my family/guardians to ask permission before hugging or touching other people (e.g., friends)” and “I was taught about consent during my K-12 education.” This series of questions was drafted by the first author in collaboration with autistic focus group participants, in order to highlight both the implicit and explicit ways consent may be taught to students in childhood. In focus group conversations, implicit messaging on bodily autonomy was seen as a particularly important area for further assessment.Footnote1 Consistency was good, Cronbach α = 0.80.

Analyses

Thematic Analysis (ACCS)

Given that we sought to interpret qualitative data in such a way to identify themes that may tell us about the broad issue of participants’ experiences and difficulties with consent, thematic analysis was chosen as a flexible analytic tool that meets the present needs. Specifically, the essential structure of Braun and Clarke’s 6-phase analytic plan (Citation2006) was used. Although not an inherent part of the 6-phase model, the research team first became familiar with expected themes and comments that we hypothesized would be relevant. This was done through literature review, reviewing prior qualitative data, discussions with a focus group of autistic adults, and collaboration across the neurodiverse research team. A draft coding framework was created in order to highlight hypotheses and potential categories of themes that would be of interest to research questions.

Next, during data collection, all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Auto-transcription was first completed through the online software Otter.ai and then edited by a research assistant to correct transcription errors. Transcripts were then checked by the first author, who also conducted all interviews. Thus, at least one team member was intimately familiar with all data, having been present for its collection and actively listened to every recording. Other coders additionally reviewed a subset of recordings, both to familiarize themselves with data and to edit transcripts.

Notes on potential themes, code changes, and areas to further discuss with the broader team were made throughout this review process. The first author then led the process of editing and adding to the preliminary codes, to create a more robust coding structure aligned with the data. This step occurred contemporaneously with data collection. Although some a priori codes related to the aims of the broader study were drafted prior to data collection, according to hypotheses, other codes were added in response to observations. For example, a priori codes included noting the sexual consent cue described as “most important” to the participant, as well as specifying multiple types of consent cues that participants might describe relying on, including “explicit verbal” and “nonverbal” cues. After review of data, additional codes were added for consent cues that had not been anticipated – such as the more nebulous category of “vibes” that several participants mentioned during interviews.

To support a shared understanding in coding framework and to aid in training coders new to qualitative analysis, initial transcripts were coded by the full coding team: a randomly selected set of five initial transcripts were coded by all five qualitative coders (one graduate student, one post-baccalaureate research assistant, and three undergraduate research assistants). Following this coding, all coders met and gave input on the coding structure in order to clarify areas of confusion and inductively incorporate observations from data. Following these initial 5 transcripts, all remaining transcripts were coded by two coders. Coders were randomly assigned to each transcript, such that each coder was assigned approximately the same number of transcripts and collaborated with each other coder approximately the same number of times. Thematic analysis was conducted in Delve (Twenty to Nine LLC, Citation2023), using a combined inductive and deductive approach, as previously described.

Coders met with one another to reach final agreement on coding of each transcript, as needed to ensure a final Krippendorff’s alpha over .80 (Artstein & Poesio, Citation2008). The first author then assessed how well codes fit into preliminary themes, and the full study team had the opportunity to refine themes as needed. Refinement and data exploration was done primarily through Delve. Data were split into autistic and non-autistic students and themes both across and between groups were considered. For the present analyses, this process particularly focused on drawing themes from the various codes related to the consent cues participants noted that they and others tended to use or prefer. Examples of several of these initial codes are shown in . The research team began by assessing the frequency of each code, noting ones that were particularly common or uncommon (with no minimum frequency expected). We evaluated overlap in cues – particularly examining excerpts coded with both the marker that participants expressed something to be “most important” for them in evaluating consent and including a specific consent cue. This element of our larger thematic analytic process was the crux of present findings. Themes were reviewed and defined as a research team. Where evidence was deemed insufficient (i.e., minimal participant comments fell into these categories), themes were consolidated or eliminated.

Table 1. Examples of consent cue codes.

Selected example quotations were then edited to match a clean verbatim transcription style for ease of reading (i.e., minor speech errors and filler words were removed). Finally, themes noted in qualitative analysis informed quantitative hypotheses for the larger sample.

Combined Quantitative Analyses (ACCS and 2m2×)

Based on these qualitative data, the study team then generated and tested several hypotheses using quantitative data from the larger, combined dataset. General linear models were used to assess for differences across study samples in (lack of) perceived behavioral control – the subscale which assessed participants’ confidence in seeking verbal explicit consent -, indirect behavioral approach, and positive attitude toward consent. We also assessed for differences in these three variables by childhood sexual education experiences, by autism status (dichotomous), and self-report of autistic traits (continuous variable).

Method: Study 2 “2m2×”

Participants

Eligible participants for 2m2× were required to be 18 years or older and in their first semester enrolled as an undergraduate student at each respective campus (prior experience at other universities was permitted). Exclusion criteria included history of psychosis or bipolar disorder, or current concerns of significant substance-use disorders, as these may obscure the larger study’s mood-focused comparisons across our cohorts of interest.

The online 2m2× participants included 230 students from four public, northeastern U.S. university systems: Rowan University, Montclair State University, Stony Brook University, and City University of New York. Within this sample of 230 students, 113 endorsed a history of either formal autism diagnosis (n = 27) or suspected/heard from others that they may be autistic (n = 86). In both studies, autistic participants were enrolled first, and were then matched with non-autistic students based on age, gender, sexuality, and race/ethnicity.

The inclusion of individuals without a formal autism diagnosis was intended to ensure our sample allowed for the representation of a large range of autistic individuals, including minoritized individuals who may be less likely to have access to formal diagnosis (Wiggins et al., Citation2020), as well as improve recruitment. However, quantitative analyses were conducted both by dichotomous autism status and by continuous measure of autistic traits, particularly to account for the ways we cannot be certain whether everyone in the “autistic” group would meet full diagnostic criteria for autism.

For all quantitative measures, the samples of ACCS and 2m2× were combined. In this combined sample, participants were adults ages 18–35 years old (M = 19.38, SD = 2.08), and 51.5% women, 35.8% men, and 12.7% non-binary or other gender. The most common sexual orientations endorsed were straight (52.7%), bisexual (24.2%), and pansexual (6.9%); most common racial categories endorsed were White (58.8%), Black/African American (14.6%) and Asian (14.6%). About 31% of the sample identified as Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, 17.3% indicated they identified with another racial/ethnic identity that was not listed as an option in the survey. When asked about their parent with the least education as a proxy for socioeconomic status (Diemer et al., Citation2013; Entwisle & Astone, Citation1994; Hazell et al., Citation2022), 48.9% reported this parent completed high school or less, 18.5% reported their parent completed some college, and 30.7% reported their parent received a post-secondary degree. Demographics by study (in-person and online-only) are shown in .

Table 2. Demographics of participants across samples.

Procedures

In the online, short-term longitudinal study, interested students completed an online eligibility screener prior to their first semester at one of the four participating university systems. This eligibility screener contained questions about the participants’ student status (university attended and year in school), diagnostic history, and basic demographic information.

Enrolled participants were then asked to complete an online baseline survey “packet” at the beginning of their semester. This packet included self-report measures of mood, autistic traits, experience with sexual education and consent, childhood trauma, and demographic information. Participants next completed a REDCap survey twice per week from a link texted to their smartphones, and finally an endpoint packet at the conclusion of the semester that repeated many of the baseline measures. These longitudinal processes and additional mood-focused findings are described elsewhere (McKenney et al., Citation2024; McKenney, Brunwasser, et al., Citation2023); however, current analyses focus on baseline data related to understandings of sexual consent collected during Fall 2022 and 2023. The current study and measures received approval from the Rowan University Institutional Review Board, which was the IRB of record for most recruitment sites, as well as Stony Brook University. Participants were compensated up to $75 total in the form of visa gift codes, for completing the majority of study measures.

Measures

Relevant to the current analyses, participants completed self-report measures identical to those that ACCS participants completed, as previously described. These included the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012), Sexual Consent Scale-Revised (SCS-R; Humphreys & Brousseau, Citation2010), and Childhood Modeling of Consent Questionnaire (CMCQ).

Results

Qualitative Observations

In our qualitative data, we found several themes related to comfort navigating sexual consent. Firstly, there was a theme of preference for explicit verbal consent across both autistic and non-autistic students. Of the 30 participants, 24 indicated that they preferred explicit verbal consent in some or all sexual contexts. These 24 participants included 7 autistic students (approximately 88% of autistic participants) and 17 non-autistic students (approximately 74% of non-autistic participants). Of the remaining 6 participants who did not express preference for explicit verbal consent, only 1 specified any preference against verbal consent, which she (a non-autistic, cisgender woman, age 23) associated with feeling introverted and unable to “communicate face-to-face,” at least in terms of initiating consent discussions. This theme of preference for explicit verbal consent was exemplified with quotes such as the following:

I personally think talking works and it’s the most straightforward and least prone to misinterpretation … I think that verbal consent is the easiest thing to do. Might not be the sexiest but it’s simple. Whereas nonverbal, I think that would be really difficult for me. I’ve actually never had an experience without verbal consent. (Autistic cisgender man, age 20)

I have trouble with body language. So I have set the policy and for both of my first kisses there’s been an exchange of ‘can I?’ ‘yes’. (Autistic non-binary person, age 20).

I’m waiting for a strong yes. (Non-autistic cisgender woman, age 19)

It is both parties’ right to communicate [verbally]. And it’s also both parties’ responsibility to communicate. (Autistic cisgender man, age 21)

There was also a subtheme in which 14 participants (n = 5 autistic) indicated they “knew” others did not rely primarily on verbal consent, even though they themselves preferred it. We named this theme divergence between preference and perceived social norms. For example, one participant stated:

I think it [reliance on body language] might be more common than trying to ask for verbal consent. (Autistic cisgender man, age 20)

Participants explained that they see their peers as less likely to engage in explicit verbal consent practices for a variety of reasons, commonly including feeling embarrassed, shy, or concerned that it would “kill the mood.” In some cases, participants expressed a willingness to confirm consent verbally despite uncertainty of how a sexual partner might react. Quotes such as the following illustrate these views:

I’m a big communicator, I don’t care if it would kill the mood. I’m going to use my words if I’m unsure, even in the slightest. (Non-autistic non-binary person, age 19)

I’m literally asking for very clear signals and delineations. I don’t have a soft spot for keeping the magic of the experience and I’m very much ‘I don’t care.’ I need to know this information vitally. And it doesn’t kill my mood. (Autistic non-binary person, age 25)

… even though I’m probably worried about how they react, I just … put myself first with this, because it’s very intimate. It’s just you don’t want to feel violated or get sexually assaulted. (Non-autistic cisgender man, age 22)

Well, I think a lot of people right now, in our day and age are like, ‘Oh, intimacy, you know, I don’t want to have to break the intimacy. I don’t want to ruin the vibe by asking them.’ Well, it’s like, you’re gonna ruin the vibe if you don’t ask. (Non-autistic cisgender man, age 21)

Some participants noted that the uncertainty of how seeking verbal consent would be received had made them less comfortable asking explicitly for consent at times, noting things like they don’t want to “make it weird” (Non-autistic cisgender woman, age 19) or that they have felt “too awkward to actually say that [talk about consent]” (Autistic non-binary person, age 20). One participant described how they overcame this anxiety, with the following:

The thing that was scaring me about asking for consent is like, ‘Oh, what if that person is turned off when I ask that?’ But, now I’ve come to realize, if they are turned off then, they’re not the right person for me, because I should be able to ask for consent freely, and if they’re uncomfortable with that, that’s their fault. (Non-autistic nonbinary person, age 18)

Only one participant noted they themselves found that using – or overusing – explicit verbal consent would make them feel less engaged in the sexual interaction: “If you’re making out with someone, you’re not going to be like, ‘yes, you can do this and this and this,’ because sometimes it kills the mood” (Non-autistic non-binary person, age 24). However, they also noted that explicit consent would be their preference in contexts when enthusiasm was unclear.

For this paper, these qualitative themes were then used to drive quantitative analytic questions. Given that participants in the in-person portion of the study were willingly volunteering to participate in a study focused on sexual consent cues, we anticipated that these participants would tend to report greater perceived behavioral control (i.e., report relative confidence around navigating consent cues) and would endorse feeling more positively about seeking verbal sexual consent than their peers who participated in the online study, which was largely focused on and advertised to be about mood during the transition to college. This hypothesis was then tested quantitatively.

Quantitative

Lack of Perceived Behavioral Control

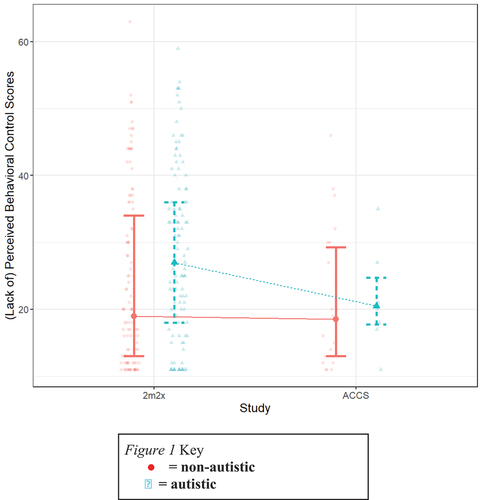

We assessed for differences in the (lack of) perceived behavioral control subscale of the SCS-R between participants in the in-person, consent-focused study (ACCS) and the online, mood-focused study (2m2×). As noted previously, this (lack of) perceived behavioral control subscale evaluates how difficult an individual believes it is to verbally ask for sexual consent. Difference in perceived behavioral control by study (comparing participants in ACCS and in 2m2× via a general linear model) was approaching significance, but with a small effect size, F(1, 250) = 3.77, p = .05, r2 = 0.02. Students in the online mood-focused study (M = 26.20, SD = 13.00) reported being similarly comfortable with navigating sexual consent, particularly verbally, as students in the consent-focused, in-person study (M = 21.40, SD = 9.42). See .

When evaluating differences in perceived behavioral control by SRS-2 scores (a measure of autistic traits), general linear model results showed that students with higher SRS-2 scores endorsed a greater lack of perceived behavioral control, F(1, 250) = 14.35, p = .0002, r2 = 0.05. In other terms, on this quantitative measure, students with more autistic traits endorsed being less confident navigating sexual consent, particularly through explicit verbal consent cues. This effect persisted when controlling for both reported childhood sexual education experiences and whether or not the participant reported having past sexual experiences, F(1,244) = 14.07, p = .0002, r2 = 0.09. Findings were similar when considering differences by self-defined autism group, instead of SRS-2 scores: autistic students (M = 28.06, SD = 12.51) endorsed a greater lack of perceived behavioral control than non-autistic students (M = 23.48, SD = 12.55), when controlling for reported childhood sexual education and prior sexual engagement, F(1, 244) = 8.35, p = .004, r2 = 0.08.

Indirect Behavioral Approach

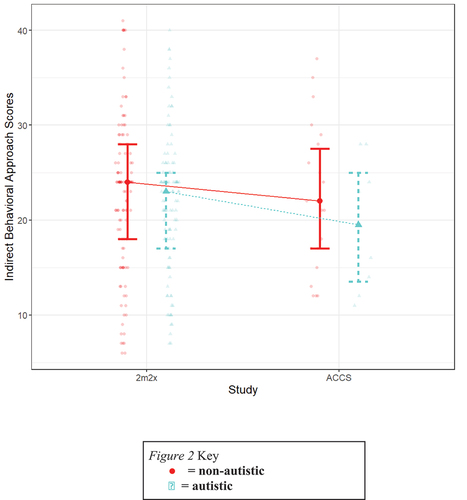

When assessing differences in use of an indirect behavioral approach (e.g., body language, nonverbal signals), there were no significant differences in indirect behavioral approach between in-person consent study participants (M = 21.6, SD = 7.39) and those in the mood-focused online study (M=22.20, SD = 7.73), F(2, 249) = 0.80, p = .45, r2 = 0.001. See .

There were also no significant differences by SRS-2 scores, F(1, 250) = 0.20, p = .66, r2 = 0.007. When looking at differences by self-defined autism groups (autistic including both those with a formal autism diagnosis or suspected autism), there similarly appeared to be no significant differences between autistic (M = 21.61, SD = 7.23) and non-autistic (M = 22.63, SD = 8.05) students’ use of an indirect behavioral approach to consent, F(1, 250) = 1.11, p = .29, r2 = 0.004.

Positive Attitude Towards Consent

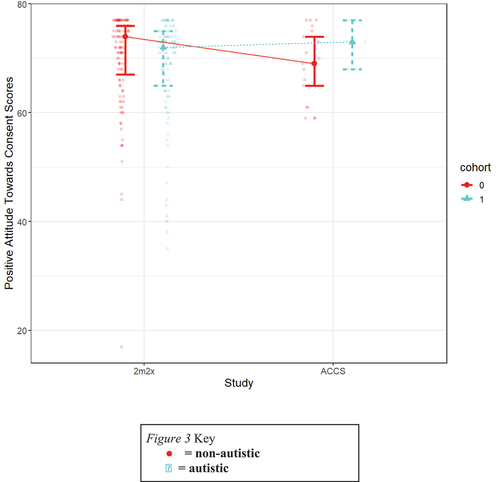

There were no significant differences in positive attitude toward consent between in-person consent study participants (M = 69.80, SD = 5.94) and online, mood-focused study participants (M = 69.30, SD = 9.33), F(1,250) = 0.11, p = .74, r2 = 0.0004.Footnote2 See .

There were no significant differences in positive attitude toward consent by SRS-2 scores, F(1, 250) = 0.39, p = .53, r2 = 0.002. Similarly, no significant differences were detected between autistic (M = 68.70, SD = 9.47) and non-autistic (M = 69.86, SD = 8.55) students, F(1, 250) = 1.04, p = .31, r2 = 0.004.

Discussion

In the current, mixed-method study, we sought to explore students’ preferences regarding and difficulties with sexual consent cues. We first identified a theme of preference for explicit verbal sexual consent among undergraduate participants who self-selected into a study of sexual consent communication, with a subtheme that they believed others likely found this explicit verbal consent “unsexy.” Quantitative data within this study was combined with data from a larger sample of undergraduates in an online-only, mood-focused study (without an emphasis on consent or sexual education in any recruitment materials.) There were no significant differences observed across samples in comfort level with verbally discussing consent (perceived behavioral control), use of an indirect behavioral approach to navigating consent, or positive attitudes to sexual consent communication. This lack of differences noted across samples indicates that acceptability of explicit verbal consent may indeed be shared across undergraduate youth, despite the common within-individual perception that it is unusual or unique to oneself.

Attitudes Towards Sexual Consent Across Studies

From qualitative data, we interpreted a theme of a preference for explicit verbal consent. Interestingly, there was also a subtheme in which participants described believing that others (such as peers) are likely to view asking for sexual consent as awkward or “un-sexy.” Interestingly, there were very few cases of participants endorsing this belief themselves – with several explicitly stating that explicit verbal consent did not “ruin the mood” for them.

Thus, investigators noticed an interesting trend – many participants were referencing feeling that others would disapprove of explicit verbal sexual consent, and yet, we observed few, if any, instances of individuals themselves having a preference against explicit verbal consent (specifically, possibly 1 person out of 30 interviewed, and even then equivocal, as they said they preferred explicit verbal consent in cases of unclear enthusiasm). This led researchers to hypothesize that individuals who participated in a consent-focused study may be unique from the general student population, in their preference for and comfort with explicit verbal consent. We anticipated that students with this interest in consent research might be more likely to feel positively about discussions of consent and endorse explicit verbal approaches to consent. This hypothesis was tested by comparing data from the in-person, consent study participants with the n = 230 participants from an online, short-term longitudinal study on mood symptoms during the transition to college. Contrary to expectations based on qualitative data, there were no differences in attitudes about consent or endorsement of verbal or nonverbal cue usage between participants who volunteered for an in-person consent-focused study (and often deemed themselves to be uniquely driven to rely on verbal consent) and those who participated in a study that tracked mood during the transition to college (and that we had no reason to believe were especially interested in consent).

Across groups, most students endorsed feeling positively toward establishing sexual consent. This may be another area where consent opinions have been improving over time. Whereas some earlier literature described affirmative consent processes as “unrealistic” to many young adults (Curtis & Burnett, Citation2017), this may not be the attitude of the current sample. In the last decade, there has been an increase in affirmative consent programs and policies (Jozkowski, Citation2015) and increased awareness of sexual violence (Jaffe et al., Citation2021). This may contribute to more favorable attitudes toward both consent in general and verbal consent. At the same time, given that this is an evolving cultural phenomenon, students may not have a strong perception of others’ attitudes toward consent, as evidenced by the qualitative sense that students felt others were less likely to feel favorably about explicit consent than them.

Similarly, there were no significant differences observed in perceived behavioral control across the two studies: students appeared to be similarly comfortable navigating sexual consent, particularly using explicit verbal communication, regardless of whether they had self-selected to participate in a consent-focused study or not. There were also no group differences found in use of nonverbal consent cues across the self-selected ACCS participants and the larger, more diffuse 2m2× sample.

This discrepancy between qualitatively-noted beliefs and quantitative findings raises the questions of a) how common is the belief that other people are less comfortable with explicit verbal consent than they are, and b) where are students receiving this message that other people will find it upsetting or undesirable if they ask for verbal consent? These questions are beyond the scope of our current findings; more research is needed to explore how common it may be for individuals to feel that their peers find verbal explicit consent to be undesirable, as well as how this compares to peers’ actual opinions on consent. However, given how prevalent this theme was in our current qualitative data, it is likely worth considering the potential causes and implications of this belief. This finding may be related to the current cultural attitudes toward sexuality and consent at this moment in history: Specifically, young adults may be at a transition point in history, where they are familiar with older sexual scripts with expectations for minimal consent discussion (Willis et al., Citation2019), but they have also been exposed to consent-positive initiatives and similar newer norms in social media (Beres, Citation2014; Graf & Johnson, Citation2021). This could potentially be contributing to a sense of cognitive dissonance, in which they have been collectively taught to emphasize explicit verbal consent however, there is also the feeling that this is different than the predominant cultural expectation. Therefore, they assume that others – even their peers – may be acting differently than them.

Attitudes Towards Sexual Consent by Autism Status

There were no significant differences detected in positive attitude toward consent or indirect behavioral control by SRS-2 scores or self-defined autism status. In other words, students with more autistic traits or those who endorse a history of suspected or diagnosed autism do not appear to be more (or less) likely to feel positively about consent. Students with more autistic traits also do not appear to differ significantly in their reliance on body language cues to navigate sexual consent. This is interesting, given that some previous research has suggested autistic students feel they may struggle more with interpreting consent via body language (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015). Other research has shown, however, that autistic people are not necessarily less skilled at interpreting emotion from body language (Peterson et al., Citation2015). Greater research is needed in the consent context to understand how perceptions of one’s use of body language (measured here via self-report measures) may relate to actual consent behavior.

Although in qualitative data there was a prominent theme of reliance on and preference for explicit verbal consent in both autistic and non-autistic students, quantitative data from autistic students indicated somewhat less comfort with their ability to navigate these sexually consent conversations verbally as compared to non-autistic participants. Students with more autistic traits appeared to endorse a greater lack of perceived behavioral control, meaning they experienced less comfort navigating consent with explicit verbal conversations as compared to their peers with fewer autistic traits. This was as indicated by scores on the (lack of) perceived behavioral control subscale. These differences in subscale scores persisted when controlling for whether students had engaged in sexual experiences previously – indicating level of comfort was not merely a measure of prior experience with consent navigation – as well as how much participants felt that they were taught about consent throughout childhood. Further research may seek to further confirm and explore other causes of these differences by autistic traits. One possibility is that this difference is explained by social anxiety: explicit verbal navigation of consent could be more anxiety-inducing or feel difficult for individuals who have greater social anxiety. Social anxiety commonly co-occurs with autism (Spain et al., Citation2018). Alternatively, or in addition, measure of constructs, including differential interpretations of items between autistic and non-autistic students could play a role in explaining the difference between scores. It is particularly noteworthy, however, that participants with more autistic traits continued to endorse the importance of verbal consent in qualitative interviews, despite this lower comfort with the experience of navigating consent verbally. Thus, this difference in subscale scores should not necessarily be taken as evidence that autistic students are less likely to actually ask for explicit verbal consent. One possibility is that these students are equally likely to engage in explicit verbal consent behaviors, despite it being more difficult or uncomfortable, due to how highly they value it. This is an important area for future research.

Limitations

It was assumed that students who participated in the mood-focused, online study held relatively “typical” consent beliefs as the general student population, and, thus, they were used as a comparison group to the students who enrolled in a consent-focused study. However, it is possible that the students who agreed to participate in the online study were not representative of the general student population. Future research could benefit from continuing to assess consent norms across large and diverse samples of undergraduate students.

As noted in prior publications on the online, mood-focused study (McKenney et al., Citation2024; McKenney, Brunwasser, et al., Citation2023; McKenney, Cucchiara, et al., Citation2023), there are both benefits and drawbacks to the inclusion of individuals who do not have a formal autism diagnosis in the online portion of the study. This methodology may better allow for the inclusion of historically underrepresented groups who may have less access to formal autism diagnoses (Wiggins et al., Citation2020). However, it also limits the diagnostic certainty of our cohorts. For this reason, SRS-2 scores were additionally used as a continuous measure of autistic traits, rather than relying solely on dichotomous autism categories in quantitative analyses.

Finally, further research is needed to clarify individuals’ intended versus actual use of consent cues. In particular, our current data suggested that, qualitatively, autistic participants (as well as many non-autistic participants) placed a high value on the use of explicit verbal consent. Students saw this as an essential way to ensure sexual experiences were consensual, without depending on tools like interpreting body language, which many participants indicated may be unreliable. At the same time, quantitative results suggest that these verbal consent discussions may be experienced as less comfortable for autistic students, compared to non-autistic peers. These two things may not be mutually exclusive – certainly, it is possible to do things that one values and finds important, even if they feel uncomfortable. This could even act as greater evidence of how valued explicit verbal consent is to our autistic participants, given that they qualitatively emphasized its importance, despite it being less comfortable for them. However, the current study is not able to comment on actual consent-seeking behavior outside of self-report measures. To further understand the intersection of consent-related values, anxieties/difficulties, and behaviors in neurodiverse populations, converging evidence across multiple studies and methodologies would be essential.

Implications and Future Directions

The present study suggests that a significant number of undergraduate students may perceive that explicit verbal consent will be looked down upon by peers, and yet this perception of “others’” beliefs is not necessarily backed up by current data. Many college students seem to feel positively about consent, including the use of explicit verbal consent. This discrepancy between beliefs about others’ and peers’ actual stated beliefs could have many different causes, including societal change that has led to dissonant social scripts. However, regardless of the cause, if further data continues to show a difference between perceived and actual consent attitudes of peers, this may lead to a useful opportunity in public awareness messaging and interventions to improve sexual health and safety. For example, differences between perceived and actual attitudes toward consent practices could be clarified through a mechanism such as personalized normative feedback. Personalized normative feedback is a brief intervention in which a provider corrects misconceptions about how often peers may be engaging in (usually problematic) behaviors. For example, personalized normative feedback has been used to correct students’ overestimates of peer drinking habits. This simple, easy to administer intervention of clarifying the drinking norms of peers has been found to reduce heavy drinking behavior in college students (Lewis et al., Citation2014; Wolter et al., Citation2021). Similarly, personalized normative feedback has been used to reduce overestimations of peers’ involvements in sexual hookups, which then contributed to reduced engagement in hookups and reduced sexual victimization (Testa et al., Citation2020). Given this evidence that norms clarification can effectively reduce overinvolvement in potentially harmful behaviors in college students, perhaps we can similarly use feedback on norms to increase involvement in a helpful behavior. As noted in our qualitative findings, many students feel that their peers probably feel negatively about verbal consent. Further research may benefit from evaluating whether showing young adults data demonstrating that most young adults feel positively about and engage regularly in explicit verbal consent practices is beneficial in encouraging verbal consent behaviors.

Comprehensive sexual education models and affirmative consent models often aim to teach students that explicit verbal consent is a beneficial tool to protect themselves and others (Beres, Citation2014; Graf & Johnson, Citation2021; Torres, Citation2023). Yet, sexual education programs often have limited to no guidance on how to normalize talking about consent. Our current findings may suggest that this is a gap in students’ education, such that students are learning the benefits of explicit verbal consent, but are not learning that it is expected or accepted within their peer group. While this may be an area where all students could be better served, this is particularly concerning in the context of autism. Autistic students are at increased risk of sexual assault and abuse victimization (Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018) and perpetration (Dike et al., Citation2022; Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018). Additionally, they often report inadequate sexual education experiences both at school and at home (Ballan, Citation2012; Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015; Hancock et al., Citation2017). Therefore, as we continue to evolve sexual education programming and add creative elements (potentially including personalized normative feedback), it is essential to ensure that this information is accessible to all students and taught inclusively.

The current findings also highlight the dilemmas that may occur when students feel isolated from others’ opinions of consent or feel that they do not share a “language” to communicate about consent. While many of our participants felt that they were still able to ask for explicit verbal consent even when assuming others would not appreciate it, several indicated that this perception of others’ beliefs caused them to hesitate. This leads us to question whether non-integrated sexual education classes could potentially further difficulties in consent communication between students with and without disabilities. While beyond the scope of the current study, it is worth noting that in many states, there are no formal requirements for sexual education for students with disabilities (National Conference of State Legislatures, Citation2020) and there are a limited number of comprehensive sexual education models for this population (Grove et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the limited sexual education that is provided to students with disabilities may vary by the comfort of teachers and parents, meaning it may be significantly different than the curriculum other students are learning and taught separately (Ballan, Citation2012; Wilson & Frawley, Citation2016). Future research is needed to explore whether these differential sexual education lessons further sexual consent “communication gaps” between groups of students. Subsequently, greater research focus on strategies for communicating sexual education knowledge across diverse student populations may be beneficial.

Conclusion

Adults entering college, especially autistic individuals, may have a higher likelihood of encountering unwanted and/or traumatic sexual experiences, raising the potential risk of long-lasting mental and physical health concerns (Brown et al., Citation2017; Dike et al., Citation2022; Pecora et al., Citation2019; Sevlever et al., Citation2013; Weiss & Fardella, Citation2018). Although evidence has suggested that misunderstandings in consent are unlikely to be a causal factor in most incidences of sexual assault (Fenner, Citation2017), autistic students in particular have expressed fear of missed or incorrectly pursued romantic opportunities (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, Citation2015). Some evidence has suggested that nonverbal consent indicators – like body language – may be especially likely to pose a challenge for autistic students. Current findings suggest that explicit verbal consent is thought of positively by many undergraduate students, in both our autistic and non-autistic group and across both students who opted to participate in a consent-focused study and the potentially more general student population, who participated in an online mood-focused study. However, many undergraduates still express concerns that others may not share their opinion and may find explicit verbal consent to be disruptive or “unsexy.”

Compared to non-autistic students, there were no significant differences found in positive attitudes toward consent or in indirect behavioral control within our autistic sample. Additionally, autistic students did not appear to differ in their reliance on body language cues to navigate sexual consent. However, in quantitative data, autistic students reported being less comfortable in their ability to navigate sexual consent conversations verbally, despite qualitatively describing explicit verbal consent as very important. Given these findings, additional research is needed to further understand intended versus actual use of consent cues. If the discrepancy between perceived and actual consent attitudes of peers continues in future studies, it may offer a unique opportunity to improve interventions for sexual health and safety, such as addressing the misconception in public awareness messaging or sexual education courses.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all of the participants, as well as the many offices and individuals who assisted in recruiting participants at Rowan University, Montclair State University, Stony Brook University, and the City University of New York system.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The creation of this measure and the focus group is described in greater detail in the first author’s dissertation (McKenney, Citation2024). However, in brief, the focus group and research team felt that, beyond the potential gaps in explicit sexual education that is more fully represented in existing literature, autistic students may also receive more implicit messages that communicate the importance of compliance and fail to encourage bodily autonomy throughout their childhood (Harte, Citation2019; Späth & Jongsma, Citation2020; Sterman et al., Citation2022). These messages may vary from well-meaning attempts to teach a minimally speaking child to do a task by physically moving their body to the intentionally malicious incidents of abuse that are more commonly experienced by children with disabilities (Baladerian, Citation1991; Mansell et al., Citation1996). From a social learning theory perspective (Kunkel et al., Citation2006), this modeling of bodily autonomy norms (or lack thereof) in childhood may affect autistic people’s later expectations and actions surrounding consent, and thus, we felt it was important for further measurement.

2 For comparison, the creators of the Sexual Consent Scale-Revised reported a mean score of 4.66 for the 11 items of this subscale (Humphreys & Brousseau, Citation2010) – equivalent to a subscale total score of about 51.26 – in their validation sample of 372 undergraduate students published nearly 15 years ago.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (Ed.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Artstein, R., & Poesio, M. (2008). Inter-coder agreement for computational linguistics. Computational Linguistics, 34(4), 555–596. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli.07-034-R2

- Baladerian, N. J. (1991). Sexual abuse of people with developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 9(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01102020

- Ballan, M. S. (2012). Parental perspectives of communication about sexuality in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(5), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1293-y

- Barnett, J. P., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2015). Qualitative exploration of sexual experiences among adults on the autism spectrum: Implications for sex education. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(4), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1363/47e5715

- Beres, M. A. (2014). Rethinking the concept of consent for anti-sexual violence activism and education. Feminism & Psychology, 24(3), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514539652

- Bockaj, A., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2023). Romanticizing the stolen kiss: Men’s and Women’s reports of nonconsensual kisses and perceptions of impact on the targets of those kisses. Journal of Sex Research, 60(8), 1083–1089/ https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2103070

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063o

- Brown, K. R., Peña, E. V., & Rankin, S. (2017). Unwanted sexual contact: Students with autism and other disabilities at greater risk. Journal of College Student Development, 58(5), 771–776. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0059

- Chaidi, I., & Drigas, A. (2020). Autism, expression, and understanding of emotions: Literature review. International Journal of Online and Biomedical Engineering (IJOE), 16(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijoe.v16i02.11991

- Cleland, J. A. (2017). The qualitative orientation in medical education research. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 29(2), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2017.53

- Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social responsiveness scale-second edition (SRS‐2). Western Psychological Service.

- Crompton, C. J., Ropar, D., Evans-Williams, C. V., Flynn, E. G., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism, 24(7), 1704–1712. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320919286

- Cummins, C., Pellicano, E., & Crane, L. (2020). Autistic adults’ views of their communication skills and needs. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(5), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12552

- Curtis, J. N., & Burnett, S. (2017). Affirmative consent: What do college student leaders think about “yes means yes” as the standard for sexual behavior? American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(3), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2017.1328322

- Diemer, M. A., Mistry, R. S., Wadsworth, M. E., López, I., & Reimers, F. (2013). Best practices in conceptualizing and measuring social class in psychological research. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13(1), 77–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12001

- Dike, J. E., DeLucia, E. A., Semones, O., Andrzejewski, T., & McDonnell, C. G. (2022). A systematic review of sexual violence among autistic individuals. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10(3), 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-022-00310-0

- Entwisle, D. R., & Astone, N. M. (1994). Some practical guidelines for measuring youth’s race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Child Development, 65(6), 1521–1540. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131278

- Fenner, L. (2017). Sexual consent as a scientific subject: A literature review. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(4), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2017.1393646

- Foubert, J., Garner, D., & Thaxter, P. (2006). An exploration of fraternity culture: Implications for programs to address alcohol-related sexual assault. College student journal, 40, 361–373.

- Gibson, S. (2016). Can enthusiastic consent be sexy? The influence of consent type on perceived enjoyment and sexiness of sexual encounters related to sexual scripts and consent attitudes. University of Louisiana at Lafayette. https://www.proquest.com/openview/afcb4d495aad737ea0228c7609ccbcda/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

- Graf, A. S., & Johnson, V. (2021). Describing the “gray” area of consent: A comparison of sexual consent understanding across the adult lifespan. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(4), 448–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1765953

- Graham, A. C., Mallinson, R. K., Krall, J. R., & Annan, S. L. (2021). Sexual assault, campus resource use, and psychological distress in undergraduate women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 10361–10382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519884689

- Grove, L., Morrison-Beedy, D., Kirby, R., & Hess, J. (2018). The birds, bees, and special needs: Making evidence-based sex education accessible for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 36(4), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-018-9547-7

- Hancock, G. I. P., Stokes, M. A., & Mesibov, G. B. (2017). Socio-sexual functioning in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analyses of existing literature. Autism Research, 10(11), 1823–1833. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1831

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., & Duda, S. N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Harte, C. (2019). Reframing compliance: Exposing violence within applied behaviour analysis [ Thesis]. City University of Seattle. https://repository.cityu.edu/handle/20.500.11803/811

- Hazell, M., Thornton, E., Haghparast-Bidgoli, H., & Patalay, P. (2022). Socio-economic inequalities in adolescent mental health in the UK: Multiple socio-economic indicators and reporter effects. SSM - Mental Health, 2, 100176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2022.100176

- Hickman, S. E., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1999). “By the semi‐mystical appearance of a condom”: How young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. The Journal of Sex Research, 36(3), 258–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499909551996

- Humphreys, T. (2004). Making sense of sexual consent: Understanding sexual consent: An empirical investigation of the normative script for young heterosexual adults (pp. 209–225). Ashgate.

- Humphreys, T. P., & Brousseau, M. M. (2010). The sexual consent scale–revised: Development, reliability, and preliminary validity. The Journal of Sex Research, 47(5), 420–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903151358

- Jaffe, A. E., Cero, I., & DiLillo, D. (2021). The #MeToo movement and perceptions of sexual assault: College students’ recognition of sexual assault experiences over time. Psychology of Violence, 11(2), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000363

- Javidi, H., Widman, L., Evans-Paulson, R., & Lipsey, N. (2023). Internal consent, affirmative external consent, and sexual satisfaction among young adults. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(8), 1148–1158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2048628

- Jozkowski, K. N. (2015). “Yes means yes”? Sexual consent policy and college students. Change, the Magazine of Higher Learning, 47(2), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2015.1004990

- Kammer-Kerwick, M., Wang, A., McClain, T., Hoefer, S., Swartout, K. M., Backes, B., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2021). Sexual violence among gender and sexual minority college students: The risk and extent of victimization and related health and educational outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 10499–10526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519883866

- Kimble, M., Neacsiu, A. D., Flack, W. F., & Horner, J. (2008). Risk of unwanted sex for college women: Evidence for a red zone. Journal of American College Health, 57(3), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.57.3.331-338

- Kunkel, A., Hummert, M. L., & Dennis, M. R. (2006). Social learning theory: Modeling and communication in the family context. In Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 260–275). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452204420.n17

- Lewis, M. A., Patrick, M. E., Litt, D. M., Atkins, D. C., Kim, T., Blayney, J. A., Norris, J., George, W. H., & Larimer, M. E. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-related risky sexual behavior among college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(3), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035550

- Lindo, J. M., Siminski, P., & Swensen, I. D. (2018). College party culture and sexual assault. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 236–265. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160031

- Lyons, H. A., Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2015). Gender and casual sexual activity from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Social and life course correlates. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(5), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.906032

- MacDougall, A., Craig, S., Goldsmith, K., & Byers, E. S. (2020). #consent: University students’ perceptions of their sexual consent education. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 29(2), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2020-0007

- Mansell, S., Sobsey, D., Wilgosh, L., & Zawallich, A. (1996). The sexual abuse of young people with disabilities: Treatment considerations. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 19(3), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00115683

- Martellozzo, E., Monaghan, A., Davidson, J., & Adler, J. (2020). Researching the affects that online pornography has on U.K. adolescents aged 11 to 16. Sage Open, 10(1), 2158244019899462. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019899462