ABSTRACT

Heterosexual-identified men who have sex with men (H-MSM) are a unique population difficult to identify and recruit for research and practice. Yet, engaging H-MSM remains a top research priority to learn more about this population’s health needs. A scoping review was conducted to develop a stronger understanding of recruitment patterns involving H-MSM in research. The search and screening procedures yielded 160 total articles included in the present study. Most studies relied on venue-based and internet-based recruitment strategies. Thematic analysis was then used to identify three themes. Locations of H-MSM’s sexual encounters related to where sex researchers may recruit participants; sociocultural backgrounds of H-MSM related to important characteristics researchers should acknowledge and consider when working with H-MSM; and engagement with health services related to how H-MSM interact with or avoid HIV/STI testing and treatment and other public health services. Findings suggest H-MSM have sex with other men in a variety of venues (e.g. bathhouses, saunas) but tend to avoid gay-centric venues. H-MSM also are diverse, and these unique identities should be accounted for when engaging them. Finally, H-MSM are less likely to access healthcare services than other MSM, highlighting the need for targeted advertisements and interventions specific for H-MSM.

Research involving MSM mostly centers around gay, bisexual, and other queer-identified (GBQ+) men. Likewise, researchers and practitioners may frequently assume all MSM either identify as GBQ+ or have not yet “come out” (Carillo & Hoffman, Citation2018; Reynolds, Citation2015). However, there is a subset of MSM who identify as heterosexual despite engaging in sex with other men. H-MSM experience sustained discordance between their sexual identity and behaviors (Reback & Larkins, Citation2010). That is, H-MSM are not closeted GBQ+ men; they retain their heterosexuality throughout time and across contexts.

Importantly, heterosexual men are not the only group who experience sexual identity-behavior discordance. Research has shown gay, lesbian, and heterosexual women and adolescents may also experience discordance between their sexual identities, attractions, and behaviors (Mendelsohn et al., Citation2022; Sönmez, Citation2023). H-MSM provide numerous reasons to justify their sexual encounters with other men, including that they are infrequent, accidental, and/or recreational (Reback & Larkins, Citation2010). Others may also engage in same-sex acts to receive drugs and/or money (Fernández-Dávila et al., Citation2008). Regardless of their reasons, scholars and practitioners should accept – not stigmatize – their identities, attractions, and behaviors and acknowledge heterosexuality can be flexible to adequately target and engage H-MSM in research and practice settings (Carillo & Hoffman, Citation2016), as well as to ensure they have access to appropriate health services and information.

Targeting and engaging H-MSM remains a priority for research and practice, especially as H-MSM exhibit several health disparities. For instance, some evidence suggests H-MSM engage in transactional sex, which can increase risks for HIV and other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs; Abdallah et al., Citation2020; Fontdevila, Citation2020). Some evidence also suggests H-MSM have lower odds of HIV testing (Dillon et al., Citation2019) and are less willing to use PrEP to prevent HIV (Lim et al., Citation2017), making them more susceptible to HIV. Moreover, traditional HIV centers focus advertisements on GBQ+ men, leaving H-MSM less inclined to utilize their services (Blas et al., Citation2013; Philbin et al., Citation2018).

In addition, H-MSM report heightened levels of perceived stress compared to concordant heterosexual, gay, and bisexual men and more depressive symptoms compared to concordant heterosexual men (Gattis et al., Citation2012; Krueger et al., Citation2018). Gattis et al. (Citation2012) also found H-MSM have higher levels of anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms, and lower levels of social support than concordant heterosexual men. Sexual identity-attraction discordance is associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Sönmez, Citation2023). H-MSM are also likely to conceal their sexual encounters with other men, which may harm their mental health (Schrimshaw et al., Citation2018).

Because H-MSM tend to conceal their sexual encounters with other men, they are also likely difficult to identify and recruit for research and practice. Indeed, some research suggests H-MSM prefer anonymity (Boyce et al., Citation2012) and avoid GBQ+ spaces (Lemke & Weber, Citation2017), though many research recruitment advertisements appear to depict only GBQ+ men (Blas et al., Citation2013; Philbin et al., Citation2018). H-MSM also tend to have low trust in healthcare practitioners (Stults et al., Citation2020), potentially preventing them from engaging in healthcare services. Researchers and practitioners may experience several challenges without guidance on how to identify and recruit H-MSM. Yet, including them in research and applied interventions is necessary to improve their mental and sexual health and to prevent the ongoing spread of HIV and other STBBIs. Therefore, the present study aimed to synthesize the literature on cisgender H-MSM to offer recommendations for recruiting and engaging with H-MSM. A scoping review was conducted on empirical studies that included cisgender H-MSM to develop a stronger understanding of best practices for recruiting and engaging cisgender H-MSM in research.

Method

This scoping review examined previous research on recruitment practices for H-MSM using Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018). The published protocol for this scoping review contains a more detailed description of the methods (Eaton, Scheadler, Bradley, et al., Citation2023). Other findings from the scoping review related to the identity development, attraction, and behaviors of H-MSM are available elsewhere (Eaton, Scheadler, Kon, et al., Citation2023).

Search Procedure

Thirteen electronic databases (e.g., APA PsychInfo) were searched for relevant literature. The search was conducted between July 19 and August 7, 2022, using keywords such as “heterosexual men who have sex with men” and “sexual identity-behavior discordance.” Broad inclusion criteria were applied to enhance the comprehensiveness of the review. Studies were included if they were: (1) empirical research on heterosexual men with at least one lifetime sexual encounter with other men; (2) published on or after January 1, 2000; and (3) available in English. Cross-sectional and longitudinal as well as qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods designs were considered. In addition, this scoping review did not focus on a specific country or region; studies from any geographic location were considered for inclusion.

Screening

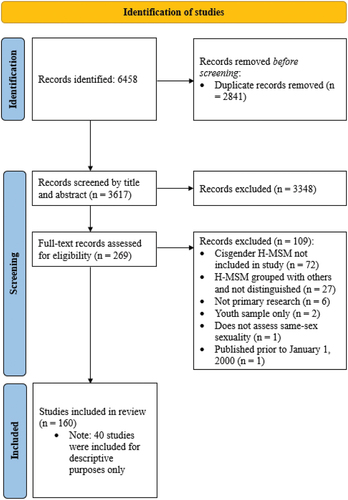

Ultimately, 160 studies were included (see ). Articles were excluded for many reasons such as not including H-MSM in the sample and not distinguishing H-MSM from other heterosexual men or other MSM. Note that 40 articles only reported demographic percentages of H-MSM in their samples. They were not population size estimation studies, nor did they provide further analyses on H-MSM. These 40 articles were included for the sole purpose of estimating the proportion of H-MSM in the broader population. Since these articles did not provide further analysis of H-MSM, these studies were excluded from the thematic analysis.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Research assistants documented details about the samples, methods, and outcomes. Extracted data from the methods sections of the included studies were used to provide an estimate of the population size of H-MSM and to describe current practices in recruiting H-MSM. Meanwhile, extracted data from the results sections of the included studies were subjected to thematic content analysis in order to identify themes that have implications for engaging with H-MSM in research. Procedures for the main analysis are described next.

Ten independent reviewers, including the first author, performed thematic analysis on the 120 articles in the main analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The included articles were divided among the coders. First, each coder familiarized themselves with their assigned studies. Then, using an inductive coding approach, each reviewer coded the extracted data with descriptive and in vivo codes from their assigned studies. Data saturation was reached when no new codes were identified with the extraction of subsequent data. Nevertheless, the research team extracted the data from all 120 records. All the reviewers then met to discuss the codes and identify patterns and themes. The first author then conducted focused coding to organize and consolidate the independent reviews. The first and last author then reviewed the themes for accuracy by revisiting the included studies. Then, the first author wrote a draft of the results. Notably, the draft of the results reflected what reviewers discussed in the aforementioned meeting and was approved by every reviewer. The results presented below focus on the analysis of methodological considerations. Themes related to the identity development, attractions, and behaviors of H-MSM have been published elsewhere.

Importantly, throughout each stage of the study, including during the data extraction and analysis stages, the authors engaged in critical reflexivity. Many members of the research team experience concordance between our sexual identities, attractions, and behaviors and had limited experience working with H-MSM. We regularly discussed our biases and accepted that our roles were to affirm and not criticize the identities of others. The inclusion of H-MSM and social workers who regularly worked with H-MSM on the research team helped to prevent any possible biases from substantially influencing the findings.

Results

Population Size Estimation of H-MSM

All 160 articles were examined to estimate the percentage of H-MSM in more general populations. Nine studies did not specify the number or percentage of H-MSM present in their respective samples. Overall, the percentage of H-MSM in the resulting 151 samples ranged from 0.03% to 100%. Most studies (n = 87) found 10% or less of participants identified as H-MSM distributed at <1% (n = 12), 1–2% (n = 11), 2–3% (n = 12), 3–4% (n = 11), 4–5% (n = 11), and 5–10% (n = 30) The remaining studies found proportions of H-MSM were 10–25% (n = 27), 25–50% (n = 22), 50–99% (n = 4), and 100% (n = 11).

Samples with higher representation of H-MSM had narrower inclusion criteria (e.g., non-gay-identified Black men who have sex with men and women who are 18 years of age or older, have a female primary sexual partner, have engaged in sex with another man in the last 12 months, and have used illicit drugs and/or alcohol in last 12 months; Benoit & Koken, Citation2012) and smaller samples. Samples with higher representation of H-MSM tended to be qualitative and focused on specific racial, ethnic, and/or sexual minority populations. Meanwhile, samples with less representation of H-MSM had broader inclusion criteria (e.g., HIV negative MSM ages 18–25; Vasilenko et al., Citation2018) and larger samples. Samples with broader inclusion criteria tended to be quantitative and focused on less specific populations.

To estimate the proportion of all heterosexual men who were H-MSM, it was necessary to focus only on studies that included both heterosexual men that do have sex with other men as well as heterosexual men that do not have sex with other men (n = 36). Sixteen found less than 3% of their samples consisted of H-MSM and another eight studies found 3–5% of their samples consisted of H-MSM. Fifteen of these studies found 0.5–3.5% of their samples consisted of H-MSM. However, these studies were all from the United States (e.g., Mendelsohn et al., Citation2022), Canada (e.g., Silva & Fetner, Citation2022), and Australia (e.g., Bowring et al., Citation2015). Thus, we can estimate that 0.5–3.5% of all heterosexual men from the US, Canada, and Australia may be H-MSM.

To estimate the proportion of H-MSM among MSM, we focused on studies that specifically recruited MSM (n = 71). Most of these studies (n = 52) included samples where less than 10% of MSM identified as heterosexual. Twenty-eight studies had samples where 1.26–5.4% of MSM identified as heterosexual. These studies were conducted with MSM in a variety of countries all over the world, representing China (Song et al., Citation2013), Peru (Blair et al., Citation2016), Panama (Hakre et al., Citation2014), South Africa (Middelkoop et al., Citation2014), Germany and Austria (Lemke & Weber, Citation2017), the US (Silva, Citation2022) and many others. Thus, based on this subset of studies, it may be likely that 1.26–5.4% of all MSM may identify as heterosexual.

Recruitment Strategies

Strategies to recruit participants were also examined. Most studies utilized nonrandom sampling methods (n = 139, 86.88%). Many included studies (n = 61, 38.13%) relied on multiple strategies (e.g., venue-based and internet-based) to recruit participants. Venue-based recruitment was the most common strategy used across studies (n = 86, 53.75%). See for details about the types of venues from which participants were recruited.

Table 1. Physical venues used to recruit H-MSM in scholarly research.

Internet-based recruitment was the second most common strategy used to access H-MSM (n = 53, 33.13%). Most of these studies did not specify which Internet platform was used to recruit participants (n = 26, 16.25%). Others used Grindr or other MSM social networking platforms (n = 11, 6.83%), Craigslist (n = 10, 6.25%), Facebook (n = 9, 5.63%), Twitter (n = 3, 1.88%), or some other website/platform (n = 13, 8.13%).

Snowball sampling (n = 33, 20.63%) and respondent-driven sampling (n = 17, 10.63%) were also common tactics for recruiting H-MSM. Twenty studies (12.5%) advertised information about their studies in local newspapers/media and/or on flyers distributed to various local businesses and organizations. Some studies also relied on participant observations (n = 7, 4.38%) while others collected data via stratified sampling (n = 6, 3.75%), college classrooms (n = 6, 3.75%), purposive sampling (n = 5, 3.13%), and the researchers’ existing social networks (n = 5, 3.13%).

Moreover, 66 studies (41.25%) provided incentives to participants. Incentives ranged from USD $0.40 to $140. Most of these studies provided participants $20–50 (n = 28, 17.5%) while many offered participants $15 or less (n = 21, 13.13%), and ten studies (6.25%) offered more than $50. Note, though, that 17 studies used respondent-driven sampling where incentives were earned based on self-participation in the study as well as the number of additional participants successfully recruited for the study. Meanwhile, four studies (2.50%) – including three studies that also provided monetary incentives – provided materials such as water bottles, condoms, lubricants, and HIV self-testing kits as incentives. Finally, three studies (1.88%) conducted in colleges or universities provided extra credit or course credit to participants and three other studies (1.88%) provided incentives to participants but did not clarify what this entailed. H-MSM may go to great lengths to conceal their participation in a study, and this may incur expenses for the participants. Providing incentives is particularly important when recruiting and engaging hidden and hard-to-reach populations.

It is also important to examine differences in recruitment strategies between the Global South and Global North. The most notable difference was that studies based in the Global South rarely used Internet-based recruitment (e.g., Shangani et al., Citation2018), whereas studies based in the Global North made greater use of Internet-based recruitment (e.g., Baunach & Burgess, Citation2013). Studies based in the Global South also frequently used snowball sampling or respondent-driven sampling (e.g., Hakre et al., Citation2014). In addition, when using venue-based recruitment strategies, studies based in the Global South largely relied on HIV/AIDS clinics and organizations (Philbin et al., Citation2018). Other venue-based recruitment strategies were lacking in the Global South. Nevertheless, studies in both the Global South and Global North utilized venue-based recruitment strategies and often used multiple recruitment strategies.

Thematic Findings

Three interconnected themes were identified related to recruitment considerations for H-MSM: locations of sexual encounters, sociocultural backgrounds of H-MSM, and engagement with health services. Each theme is described below (see Supplementary File 1 to see each of the included studies).

Locations of Sexual Encounters

Knowledge of where H-MSM engage in sex with other men will help researchers brainstorm where to seek H-MSM for future research participation. As mentioned above, most studies that used venue-based recruitment targeted areas serving H-MSM and other MSM or they targeted areas where H-MSM and other MSM allegedly congregate, such as HIV/AIDS clinics, parks, and GBQ+ bars. However, only 10 studies explicitly inquired about where H-MSM meet and engage in sex with potential partners. These studies found H-MSM engage in sex with other men in a variety of different locations, including bars and saunas, parks, public restrooms, bathhouses, prisons, ships, online, and in street corners and alleys where drugs can also be obtained (e.g., Philbin et al., Citation2018; Reback & Larkins, Citation2010). These locations are all similar in that they are outside the home and may predispose H-MSM to engage in risky sexual behaviors, given the heightened anonymity and lower access to condoms among these locations (Martínez-Donate et al., Citation2009).

Despite heavy reliance on Internet-based recruitment, only two studies reported H-MSM meeting sexual partners online. Interestingly, one study found H-MSM were more likely than gay men to experience Internet cruising as erotic (Robinson & Moskowitz, Citation2013). The authors also noted younger men tend to experience Internet cruising as more erotic than older men do. Further, H-MSM believed seeking men in public, offline spaces is connected to identifying as gay; thus, they turned to the Internet to experience sexual self-expression and satisfaction while remaining anonymous and avoiding the adoption of a gay identity (Robinson & Moskowitz, Citation2013). Relatedly, five studies found H-MSM aim to distance themselves from gay men and avoid gay venues. Lemke and Weber (Citation2017) even noted H-MSM were significantly less likely than other MSM to visit gay bars or clubs, especially if they had female partners and/or had not disclosed their same-sex encounters to others. As such, findings indicate H-MSM choose locations for finding male sexual partners based on the anonymity the location provides.

Sociocultural Backgrounds of H-MSM

A more thorough understanding of the sociocultural backgrounds of H-MSM may also help researchers determine how to more appropriately interact with and target this population. Participants in the included studies represented diverse identities (e.g., Latino, Black, White, Southeast Asian), but only 15 studies explicitly discussed the sociocultural backgrounds of H-MSM. Religiosity was the most common cultural influence mentioned across studies (n = 5). Findings suggest that H-MSM were more likely than other MSM to attend church regularly (Gattis et al., Citation2012) and often felt pressured to conform to religious traditions where opposite-sex marriage is idolized and same-sex sexual behaviors are demonized (e.g., Valera & Taylor, Citation2011). H-MSM in one study associated same-sex sexual behavior with religious sin that can be overcome and argued sins that can be overcome do not represent who one really is, allowing them to avoid adopting a non-heterosexual identity (Valera & Taylor, Citation2011). Two of these studies also mentioned H-MSM were more likely to possess conservative political beliefs (Baunach & Burgess, Citation2013; Silva, Citation2017), suggesting conservative political attitudes may coincide with their religious beliefs.

Three studies suggested identifying as non-White further complicates the experiences of H-MSM. For example, Baunach and Burgess (Citation2013) argued poverty and racism make identifying as non-heterosexual more burdensome for Black Americans in the Deep South because of the need to manage multiple prejudices, including religious stigma from evangelical Protestant Black churches. Gwadz et al. (Citation2006) found young H-MSM were more likely to be Latino, homeless, and of a lower socioeconomic class and were more likely to have experienced childhood adversity. However, Barnshaw and Letukas (Citation2010) found H-MSM were more likely to be White than non-White, but also recognized non-White H-MSM may be more reluctant to disclose same-sex sexual behaviors. Silva (Citation2017) also found White H-MSM in rural communities may not disclose their same-sex sexual behaviors to maintain invisibility and homogeneity in these communities. Seven additional studies found different cultures have different beliefs about same-sex sexuality. While some cultures view same-sex sexuality as immoral (Lane et al., Citation2008), others view phallic penetration as masculine and acceptable (and thus compatible with heterosexual-identification) for insertive partners but unacceptable for receiving partners (e.g., Cardoso, Citation2009). Thus, many different facets of culture seem to play important roles in the experiences of H-MSM and should be considered when targeting this population.

Engagement with Health Services

An awareness of how H-MSM engage with health services will also help researchers identify future pathways for effectively recruiting H-MSM in public health and related studies. Eight studies discussed how H-MSM engage with and experience health services. Three studies found fear of discrimination prevents some H-MSM from seeking sexual health services such as HIV testing (e.g., Margolis et al., Citation2012). Margolis et al. (Citation2012) also mentioned H-MSM are often: afraid to discover they have HIV, unsure where to get tested, lacking the time or resources to be tested, or in denial of the possibility of contracting HIV. Two studies determined H-MSM delay treatment for HIV and other STIs due to fear of discrimination (Philbin et al., Citation2018). Also, Merighi et al. (Citation2011) concluded H-MSM were less likely than gay or bisexual men to have a primary healthcare provider, while Stults et al. (Citation2020) found H-MSM were less likely than gay men to disclose their same-sex sexual behaviors to their healthcare providers. Thus, findings suggest H-MSM are less likely than other MSM to access sexual healthcare services.

Moreover, two of the eight studies described preferences for HIV testing and two others described preferences for certain advertisements. For example, H-MSM are more likely to be tested via social network strategies (i.e., when others in their network recruit them for testing) than via standard care (Baytop et al., Citation2014). This may not be surprising given they also prefer discreet services (Boyce et al., Citation2012). In fact, H-MSM used public health facilities because they were used by all types of people for a variety of reasons, allowing them to blend in with other patients without others assuming they engage in same-sex sexual behaviors (Boyce et al., Citation2012). Two studies then found H-MSM do not feel represented in advertisements for HIV testing and treatment, noting that HIV testing messages usually focus on stereotyped caricatures of young adult gay men (Blas et al., Citation2013; Philbin et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

This scoping review examined the existing research related to the recruitment of H-MSM. Based on the collation of the included studies, we estimate that 0.5–3.5% of all heterosexual men from the US, Canada, and Australia have engaged in sex with another man at least once in their lifetimes. We also estimate that 1.26–5.4% of all MSM identify as heterosexual. Together, these estimates suggest H-MSM are a prevalent population even though they are often ignored. However, these estimates are based on convenience sampling. More accurate estimates may be obtained through future population-based studies.

Results from this review also examined current recruitment practices of studies that included H-MSM and utilized findings from those studies to identify themes that have implications for how researchers should proceed with targeting and engaging with H-MSM. Findings indicated that most studies recruit H-MSM from a variety of venues where MSM are expected to be, such as HIV/AIDS clinics and GBQ+ bars. However, results suggest H-MSM engage in sex with other men in various unique locations but tend to avoid GBQ+ venues. Perhaps, H-MSM select certain venues, such as bathhouses and saunas, because those environments have an expected level of confidentiality – where family may not find out. Meanwhile, other settings might be perceived as riskier and in need of avoidance to prevent others from discovering their same-sex attractions and behaviors. This suggests “straight” or general venues, as well as venues that favor anonymity, may facilitate H-MSM research engagement and participation. For example, websites that encourage general research participation (e.g., Call for Participants website in the United Kingdom; Curtis, Citation2022) may be excellent venues to recruit H-MSM for sex research. Multiple recruitment strategies may also be necessary for engaging H-MSM.

Their diverse cultural identities and backgrounds also provide further insight into where to target recruitment efforts of H-MSM and also influence their attitudes and behaviors, distinguishing them from many other MSM. In particular, H-MSM are more likely than other MSM to uphold conservative and religious values and traditions and attempt to maintain separation from a GBQ+ identity (i.e., keep their same-sex sexual behaviors secret from others). Evidence also indicated that intersectionality of identities is important. H-MSM with different backgrounds and identities are challenged with battling multiple intersecting prejudices related to race, religion, income, and sexuality. Researchers should keep these challenges in mind when designing recruitment materials and interventions and when communicating with H-MSM.

Moreover, H-MSM are less likely than other MSM to access sexual health services for a variety of reasons, including fear and lack of time, resources, and knowledge. H-MSM also prefer discreet services and health advertisements not focused on stereotyped caricatures of young gay men. Yet, most MSM health advertisements target GBQ+ MSM. They also often avoid venues that are associated with GBQ+ populations, including many HIV/AIDS clinics and organizations. For GBQ+ men, research participation inclusive of their identities and experiences can be a beneficial experience facilitating affirmation and validation (Keene et al., Citation2021). H-MSM, though, seem more inclined to seek health services when they can blend in with others. Thus, H-MSM may also be more likely to participate in research studies when recruitment and other study materials and activities allow them to blend in with the general population of men. This must be considered when targeting H-MSM for future research participation.

Ethics must also be considered when engaging H-MSM. Humphrey’s (Citation1970) Tea Room study, in which the researcher discreetly followed men who were having discreet sex with other men – some of whom were H-MSM – is one notable example of how not to engage with H-MSM in research (Moreno & Sisti, Citation2014). Despite advances in research ethics, current problems in H-MSM research engagement persist. This includes defining the population, as researchers disagree on whether H-MSM are closeted GBQ+ men or are experiencing sustained sexual identity-behavior discordance. Controversies in categorization have led to harmful labels like “down-low,” which has racist implications (Ford et al., Citation2007), or “behaviorally bisexual,” which is a misinterpretation of identity (Eaton, Scheadler, Kon, et al., Citation2023). These ethical factors may make H-MSM reluctant to engage with and participate in research.

Finally, these findings underscore several recommendations for future researchers engaging with H-MSM. First, emphasize anonymity and confidentiality as much as possible. For instance, consider allowing participants to have their cameras off if interview data are being collected via Zoom or another similar program. Also, be sure not to judge, question, or challenge H-MSM based on what may appear as a misalignment between their identities, behaviors, attractions, or values. Instead, respect and consider all their identities when conceptualizing studies and designing interventions, recruitment materials, and other research activities. This includes using inclusive advertisements that do not center stereotypical caricatures of GBQ+ MSM. This also includes allowing H-MSM to label themselves; do not label them on their behalf.

In addition, plan for multiple recruitment strategies as one strategy in itself may not be sufficient. Focus less attention on GBQ+ venues unless the study also seeks to include GBQ+ MSM. Also, give less attention to clinics that specifically focus on HIV/AIDS. H-MSM may equate these clinics with GBQ+ venues. Instead, consider partnering with other public health facilities that include a broad range of populations and services. Likewise, be sure to recruit participants where they are expected to be, such as bathhouses, saunas, and cruising parks. Note, though, that these locations may change based on geographic region and culture. If recruiting through in-person methods, be sure to maintain ethical boundaries that emphasize anonymity and consent.

Limitations

While this synthesis reports proportions of H-MSM in mixed samples, the actual number of H-MSM ultimately remains unknown. In addition, a meta-analysis was not feasible given the diverse methods and outcomes within the included studies. This review also only included manuscripts available in English. In addition, not every coder reviewed each included study; other coders may have coded findings from studies slightly differently. Also, despite having community members and other key stakeholders as part of the research team, not all authors were members of this population or had prior experience working with this population. Although including a diverse research team can be valuable, it is possible that the various biases of the different authors influenced how the extracted data were coded and analyzed.

Conclusion

H-MSM remain an understudied population with little guidance on how to target. The present study collated findings from research with H-MSM to identify recommendations for how to effectively target and engage with H-MSM. Findings suggest researchers should recruit H-MSM from non-GBQ+ venues and via advertisements that do not feature stereotypical caricatures of GBQ+ men. Honoring their privacy and accepting their unique cultural identities are also important steps to recruiting H-MSM.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (35.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2380017.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdallah, I., Conserve, D., Burgess, T. L., Adegbite, A. H., & Oraka, E. (2020). Correlates of HIV-related risk behaviors among self-identified heterosexual men who have sex with men (HMSM): Survey of Family Growth (2002, 2006–2010, and 2011–2017). AIDS Care-Psychological & Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 32(12), 1529–1537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1724254

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Barnshaw, J., & Letukas, L. (2010). The low down on the down low: Origins, risk identification and intervention. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2010.19.4.478

- Baunach, D. M., & Burgess, E. O. (2013). Sexual identity in the American Deep South: The concordance and discordance of sexual activity, relationships, and identities. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(9), 1315–1335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.806179

- Baytop, C., Royal, S., McCree, D. H., Simmons, R., Tregerman, R., Robinson, C., Johnson, W. D., McLaughlin, M., & Price, C. (2014). Comparison of strategies to increase HIV testing among African-American gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Washington, DC. AIDS Care-Psychological & Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 26(5), 608–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.845280

- Benoit, E., & Koken, J. A. (2012). Perspectives on substance use and disclosure among behaviorally bisexual Black men with female primary partners. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 11(4), 294–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2012.735165

- Blair, C. S., Segura, E. R., Perez-Brumer, A. G., Sanchez, J., Lama, J. R., & Clark, J. L. (2016). Sexual orientation, gender identity and perceived source of infection among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TW) recently diagnosed with HIV and/or STI in Lima, Peru. AIDS and Behavior, 20(10), 2178–2185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1276-7

- Blas, M. M., Menacho, L. A., Alva, I. E., Cabello, R., Orellana, E. R., & Lama, J. R. (2013). Motivating men who have sex with men to get tested for HIV through the internet and mobile phones: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE, 8(1), e54012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054012

- Bowring, A. L., Vella, A. M., Degenhardt, L., Hellard, M., & Lim, M. S. (2015). Sexual identity, same-sex partners and risk behaviour among a community-based sample of young people in Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.07.015

- Boyce, S., Barrington, C., Bolaños, H., Arandi, C. G., & Paz-Bailey, G. (2012). Facilitating access to sexual health services for men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender persons in Guatemala City. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.639393

- Braun, V., & Clarke, C. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cardoso, F. L. (2009). Similar faces of same-sex sexual behavior: A comparative ethnographic study in Brazil, Turkey, and Thailand. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(4), 457–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360902816866

- Carillo, H., & Hoffman, A. (2016). From MSM to heteroflexibilities: Non-exclusive straight male identities and their implications for HIV prevention and health promotion. Global Public Health, 11(7–8), 923–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1134272

- Carillo, H., & Hoffman, A. (2018). ‘Straight with a pinch of bi’: The construction of heterosexuality as an elastic category among adult US men. Sexualities, 21(1–2), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716678561

- Curtis, T. J. (2022). The sexual behaviour and sexual health of heterosexual-identifying men who have sex with men: Understanding an understudied population to inform public health policy and practice [ Doctoral dissertation, University College London]. UCL Discovery. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10143978/

- Dillon, F. R., Eklund, A., Ebersole, R., Ertl, M. M., Martin, J. L., Verile, M. G., Gonzalez, S. R., Johnson, S., Florentin, D., Wilson, L., Roberts, S., & Fisher, N. (2019). Heterosexual self-presentation and other individual-and community-based correlates of HIV testing among Latino men who have sex with men. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000166

- Eaton, A. D., Scheadler, T. R., Bradley, C., McInroy, L. B., Beer, O. W. J., Beckwell, E., Busch, A., & Shuper, P. A. (2023). Identity development, attraction, and behaviour of heterosexually identified men who have sex with men: Scoping review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02355-6

- Eaton, A. D., Scheadler, T. R., Kon, T., Pang, N., Kwan, S., McDonald, M., Dillon, F. R., McInroy, L. B., Beer, O. W. J., Beckwell, E., Busch, A., Vandervoort, D., Bradley, C., & Shuper, P. (2023). Identity development, attraction, and behaviour of heterosexually-identified men who have sex with men: A scoping review. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3332350/v1

- Fernández-Dávila, P., Salazar, X., Cáceres, C. F., Maiorana, A., Kegeles, S., Coates, T. J., & Martinez, J. (2008). Compensated sex and sexual risk: Sexual, social and economic interactions between homosexually- and heterosexually-identified men of low income in two cities of Peru. Sexualities, 11(3), 352–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460708089424

- Fontdevila, J. (2020). Productive pleasures across binary regimes: Phenomenologies of bisexual desires among latino men. Sexualities, 23(4), 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719839915

- Ford, C. L., Whetten, K. D., Hall, S. A., Kaufman, J. S., & Thrasher, A. D. (2007). Black sexuality, social construction, and research targeting ‘The Down Low’ (‘The DL’). Annals of Epidemiology, 17(3), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.09.006

- Gattis, M. N., Sacco, P., & Cunningham-Williams, R. M. (2012). Substance use and mental health disorders among heterosexual identified men and women who have same-sex partners or same-sex attraction: Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(5), 1185–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9910-1

- Gwadz, M. V., Clatts, M. C., Yi, H., Leonard, N. R., Goldsamt, L., & Lankenau, S. (2006). Resilience among young men who have sex with men in New York City. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 3(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2006.3.1.13

- Hakre, S., Arteaga, G. B., Núñez, A. E., Arambu, N., Aumakhan, B., Liu, M., Peel, S. A., Pascale, J. M., Scott, P. T., & Panama HIV EPI Group. (2014). Prevalence of HIV, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted infections among MSM from three cities in Panama. Journal of Urban Health, 91(4), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-014-9885-4

- Humphreys, L. (1970). Tearoom trade: Impersonal sex in public places. Transaction Publishers.

- Keene, L. C., Dehlin, J. M., Pickett, J., Berringer, K. R., Little, I., Tsang, A., Bouris, A. M., & Schnieder, J. A. (2021). #PrEP4Love: Success and stigma following release of the first sex-positive PrEP public health campaign. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(3), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1715482

- Krueger, E. A., Meyer, I. H., & Upchurch, D. M. (2018). Sexual orientation group differences in perceived stress and depressive symptoms among young adults in the United States. LGBT Health, 5(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0228

- Lane, T., Mogale, T., Struthers, H., McIntyre, J., & Keegles, S. M. (2008). “They see you as a different thing”: The experiences of men who have sex with men with healthcare working in South African township communities. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 84(6), 430–433. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.031567

- Lemke, R., & Weber, M. (2017). That man behind the curtain: Investigating the sexual online dating behavior of men who have sex with men but hide their same-sex sexual attraction in offline surroundings. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(11), 1561–1582. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1249735

- Lim, S. H., Mburu, G., Bourne, A., Pang, J., Wickersham, J. A., Wei, C. K. T., Yee, I. A., Wang, B., Cassolato, M., Azwa, I., & Newman, P. A. (2017). Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men in Malaysia: Findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0182838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182838

- Margolis, A. D., Joseph, H., Belcher, L., Hirshfield, S., & Chiasson, M. A. (2012). ‘Never testing for HIV’ among men who have sex with men recruited from a sexual networking website, United States. AIDS and Behavior, 16(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9883-4

- Martínez-Donate, A. P., Zellner, J. A., Fernández-Cerdeño, A., Sañudo, F., Hovell, M. F., Sipan, C. L., Engelberg, M., & Ji, M. (2009). Hombres Sanos: Exposure and response to a social marketing HIV prevention campaign targeting heterosexually identified Latino men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(Supplement B), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.124

- Mendelsohn, D. M., Omoto, A. M., Tannenbaum, K., & Lamb, C. S. (2022). When sexual identity and sexual behaviors do not align: The prevalence of discordance and its physical and psychological health correlates. Stigma and Health, 7(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000338

- Merighi, J. R., Chassler, D., Lundgren, L., & Inniss, H. W. (2011). Substance use, sexual identity, and health care provider use in men who have sex with men. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(4), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2010.502208

- Middelkoop, K., Rademeyer, C., Brown, B. B., Cashmore, T. J., Marais, J. C., Scheibe, A. P., Bandawe, G. P., Myer, L., Fuchs, J. D., Williamson, C., & Bekker, L.-G. (2014). Epidemiology of HIV-1 subtypes among men who have sex with men in Cape Town, South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 65(4), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000000067

- Moreno, J. D., & Sisti, D. (2014). Biomedical research ethics. In J. D. Arras; E. Fenton, & R. Kukla (Eds.), The Routledge companion to bioethics (pp. 185–199). Routledge.

- Philbin, M. M., Hirsch, J. S., Wilson, P. A., Ly, A. T., Giang, L. M., Parker, R. G., & Newman, P. A. (2018). Structural barriers to HIV prevention among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Vietnam: Diversity, stigma, and healthcare access. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0195000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195000

- Reback, C. J., & Larkins, S. (2010). Maintaining a heterosexual identity: Sexual meanings among a sample of heterosexually identified men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 766–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9437-7

- Reynolds, C. (2015). I am super straight and I prefer you be too. The Journal of Communication Inquiry, 39(3), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859915575736

- Robinson, B. A., & Moskowitz, D. A. (2013). The eroticism of Internet cruising as a self-contained behaviour: A multivariate analysis of men seeking men demographics and getting off online. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(5), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.774050

- Schrimshaw, E. W., Downing, M. J., & Cohn, D. J. (2018). Reasons for non-disclosure of sexual orientation among behaviorally bisexual men: Non-disclosure as stigma management. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0762-y

- Shangani, S., Naanyu, V., Operario, D., & Genberg, B. (2018). Stigma and healthcare-seeking practices of men who have sex with men in Western Kenya: A mixed-methods approach for scale validation. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(11), 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2018.0101

- Silva, T. (2017). Bud-sex: Constructing normative masculinity among rural straight men that have sex with men. Gender & Society, 31(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243216679934

- Silva, T. (2022). Heterosexual identification and same-sex partnering: Prevalence and attitudinal characteristics in the USA. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 2231–2239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02293-9

- Silva, T., & Fetner, T. (2022). Sexual identity‐behavior discordance in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology, 59(2), 156–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12372

- Song, D., Zhang, H., Wang, J., Han, D., Dai, L., Liu, Q., Yu, F., Operario, D., She, M., & Zaller, N. (2013). Sexual risk behaviours and their correlates among gay and non-gay identified men who have sex with men and women in Chengdu and Guangzhou, China. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 24(10), 780–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462413482425

- Sönmez, I. (2023). How does sexual identity-attraction discordance influence suicide risk? A study on male and female adults in the U.S. Archives of Suicide Research, 28(2), 686–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2023.2220757

- Stults, C. B., Grov, C., Anastos, K., Kelvin, E. A., & Patel, V. V. (2020). Characteristics associated with trust in and disclosure of sexual behavior to primary care providers among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States. LGBT Health, 7(4), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2019.0214

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Tunçalp, Ö. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Valera, P., & Taylor, T. (2011). “Hating the sin but not the sinner”: A study about heterosexism and religious experiences among Black men. Journal of Black Studies, 42(1), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934709356385

- Vasilenko, S. A., Rice, C. E., & Rosenberger, J. G. (2018). Patterns of sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections in young men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 45(6), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0000000000000767