ABSTRACT

Drivers of poor sexual health outcomes among Black heterosexual man are poorly understood. Previous research has identified a need to understand Black men’s behavioral experiences and motivators in the UK. This study aimed to address this gap through a phenomenological exploration of the sexual health experiences and motivators of Black heterosexual men with experience of higher-risk sexual behaviors living in London. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 participants (18–58 years) recruited through barbershops. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze the data. Five themes were generated. For relevance, three themes are discussed in this paper: 1) The Black Man’s Battle; 2) Sexual Socialization; and 3) Sexual Behaviors, Relationships, and Health. Race and gender combined to shape experience of sexual socialization. Exposure to explicit media content from a young age promoted multiple sexual partners. Racist sexual stereotypes exposed participants to fetishization and created pressure to meet sexual expectations. Condom use motivators were complex and multifaceted. Experience of institutional racism created a lack of trust in services. However, actual experiences with sexual health services were positive and counteracted the mistrust created by racism. Sexual health services should better tailor their work to Black heterosexual men and diversify their offer. Services should collaborate with Black community organizations to deliver services outside clinical settings.

Introduction

People of Black ethnicityFootnote1 have experienced a disproportionately high burden of sexually transmitted infections (STI) in the United Kingdom (UK) since the late-1980s (Lacey et al., Citation1997), a pattern which appears to be more pronounced among Black men (Public Health England [PHE], Citation2021). Furthermore, heterosexual Black Caribbean people are disproportionately affected by the main bacterial STIs (Gerver et al., Citation2011), whilst the HIV epidemic in the UK has largely been driven by disproportionate HIV diagnoses among Black African heterosexual men and women (Rice et al., Citation2013). This highlights the need for a better understanding of the sexual health needs of Black heterosexual men.

Despite this, ethnic disparities in STI rates remain well documented, yet poorly understood (Jewkes & Dunkle, Citation2017) and simply attributed to a complex interplay of individual and structural level cultural, socioeconomic and behavioral factors (PHE, Citation2019). This ecological model of what underpins disparities must frame the design and development of preventative interventions (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], Citation2021). The experience of Black men and their sexual health is best understood through a wider multi-level picture of the determinants of health.

At individual level, Black men more frequently report higher-risk sexual behaviors, including higher numbers of recent sexual partners and higher rates of concurrent sexual partnerships, condomless sex and assortative sexual mixing patterns (Aicken, et al., Citation2018; PHE, Citation2019; Wayal, Citation2018; Wayal et al., Citation2017). However, critically, research literature evidences how patterns of sexual risk are directly linked to structural-level determinants. For racially minoritized communities, the experience of socioeconomic deprivation (Furegato et al., Citation2016; Mitchell et al., Citation2014; Mohammed et al., Citation2018; Savage et al., Citation2011), racial discrimination (Bowleg et al., Citation2013; Grollman, Citation2017; Krieger, Citation1999; Reed et al., Citation2013; Roberts et al., Citation2012) and exposure to dominant forms of masculinity (R. Connell, Citation1995; McDaid et al., Citation2019) all contribute to increased risk of poorer sexual health outcomes.

Furthermore, exploration of how factors play out at an individual level here in the UK through empirical research on Black-British male sexuality is scarce. Much of the literature, and therefore our understanding of Black male sexuality, originates from research on Black American men (Nwaosu et al., Citation2021). Where studies have been conducted (Aicken et al., Citation2020; Wayal et al., Citation2020; Wayal, Aicken, et al., Citation2018), they have focused on specific health behaviors, including condom use and concurrent sexual partnerships, with limited understanding of cultural, contextual and personal factors that inform the meaning of Black male sexuality.

To this end, the gap in our understanding of a long-standing inequality has been recognized. Previous research has called for work around the sexual health preventative needs of Black heterosexual men (Dunlap et al., Citation2013). More recently, a systematic review (Nwaosu et al., Citation2021) exploring the evidence base for psychosocial interventions around condom use for Black men pointed to the need for research on the sexual health experiences and motivators of Black heterosexual men in the UK in order to inform effective and culturally relevant interventions to increase safer sex behaviors.

Aims of Current Study

This work used an innovative and unique approach to address this need through the accounts of Black heterosexual men with experience of concurrent sexual partnerships and condomless sex living in London. Slight resemblance is seen in the aim of a previous study (Gerressu, Citation2016) which explored how young Black Caribbean men’s perceptions of their male, ethnic and youth identities subsequently influenced their sexual relationships and behavior. However, this work expands on this to include older Black heterosexual men, and explored their sexuality, the social and psychological processes underpinning reported sexual behaviors, and also explored the context of racially minoritized experiences of structural racism and engagement with sexual health services.

This study aimed to answer the following questions:

Among Black heterosexual men with experience of concurrent sexual partnerships and condomless sex:

How does the experience and understanding of being a Black man inform sexual attitudes, relationships, and behaviors?

What are the motivators for condom use and how does this inform STI and pregnancy prevention efforts?

What is the experience of racism and how does this experience inform engagement with sexual health services and interventions?

In summary, this research contributes to the emerging literature by exploring the sexual health experiences and motivators of a marginalized population, Black heterosexual men in London with experience of higher-risk sexual behaviors. Understanding the thought processes that underpin higher-risk sexual behaviors, motivators of protective sexual behaviors, and factors encouraging engaging with sexual health services can help develop local profiles of psychosocial influences on sexual behaviors which are significant to developing tailored, culturally appropriate interventions that aim to reduce poor sexual health outcomes.

Previous research (Gerressu, Citation2016; Wayal et al., Citation2020) has described the influential nature of media content like music and movies on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of Black men in a UK context. Additionally, experiences of racism are said to create mistrust toward health services and delay or discourage engagement (Danso & Danso, Citation2021; PHE, Citation2020). Considering these reports, similar experiences were expected among participants in this study.

Method

A phenomenological approach was adopted as it has been suggested as the most appropriate method for an in-depth exploration of personal meanings of individuals’ lived experiences and behaviors (Polgar & Thomas, Citation2000; Rossman & Rallis, Citation2003). Similarly, one-to-one semi-structured interviews were identified as the most appropriate data collection method to obtain rich and meaningful data of the phenomena whilst providing participants with a safe and non-judgmental space to openly discuss experiences of sex and relationships, a sensitive topic of investigation (Anderson et al., Citation2009; Sim & Waterfield, Citation2019). Previous research (Gerressu et al., Citation2009; Wayal et al., Citation2020) has successfully used one-to-one semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis to obtain and analyze accounts of sexual attitudes and behaviors among people of Black ethnicity in the UK.

Participants

It is well documented that phenomenological studies require less participants than other qualitative methodologies, with a maximum of 10 interviews suggested, and an ideal number toward the top of that suggestion (Moser & Korstjens, Citation2018). This is supported by Creswell (Citation1998) who suggested long interviews with 10 participants for a phenomenological study.

For relevance to the research questions, people were eligible to participate if they: were aged 18+ years; self-identified as Black British, Black African, Black Caribbean or Black Other ethnicity; identified as a cisgendered man; engaged in sexual activity with women only; had current or prior experience of engaging in condomless and condom-protected sex; had current or prior experience of concurrent sexual partnerships; and possessed a good level of English speaking and reading ability.

We avoided recruiting from sexual health clinics to ensure the experiences of those who may have disengaged from mainstream services could be captured. Consequently, barbershops were chosen as the recruitment location as their integral and cultural value within the Black community (Alexander, Citation2003) provided access to Black men who may not be accessed at mainstream health services like sexual health clinics or commercial and social venues like nightclubs and social gatherings. The study was granted ethical approval from the university research ethics committee in July 2020.

Measures

The interview guide (online supplementary file 1) for this study was developed to cover various themes about the sexual health experiences of Black heterosexual men and was informed by previous studies (Gerressu, Citation2016; Wayal et al., Citation2020) which qualitatively explored attitudes and drivers of sexual behaviors among men of Black British and Black Caribbean ethnicities in London, but adapted for relevance to the aims of this study.

Procedure

A combination of snowball and purposive sampling strategies were adopted for recruitment. Initially, three barbershops (one in South London, one in East London and one in West London) with large customer bases and social media followings were identified as recruitment locations. Barbershops were contacted and asked to display the recruitment poster [see online supplementary file] in a visible location within their shop. Barbers were also asked to alert eligible customers of the study. The poster contained a barcode which took participants directly to the study registration page when scanned, where participants could access the study information sheet and privacy notice, register interest in participating, complete a consent form and schedule an initial telephone consultation. As coronavirus restrictions resulted in the closure of barbershops for significant periods, a change in recruitment strategy was enforced. Barbershops were subsequently asked to share an image format of the poster on their respective social media platforms accompanied by a website link to the study registration page to enable customers to express an interest in participation.

Subsequently, individuals who registered to participate were contacted for an initial telephone consultation to determine eligibility, obtain informed consent, agree an interview date and time, and obtain demographic information. To ensure anonymity, participants were asked to choose a pseudonym that they would be referred to in the data. Participants were asked to ensure they had a mobile device or tablet with access to Internet and good network coverage.

Accordingly, interviews were conducted between September 2020 and March 2021 by an experienced sexual health practitioner and researcher educated to Master’s degree level and undertaking a doctoral qualification. Microsoft Teams was used to conduct and record all interviews due to government-imposed coronavirus restrictions on household mixing. Interviews ranged between 1 hour 1 minute and 2 hours 2 minutes. Subsequently, participants received a £30 high-street voucher as a token of appreciation.

Data Analysis

A reflexive thematic analysis was conducted to explore and identify patterns, and draw interpretations from the data. Data analysis was conducted by a doctoral student supervised by two experienced qualitative researchers.

Initially, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim but subsequently transcribed intelligently, omitting fillers like “erm” after five interviews were transcribed. Additionally, transcripts were read repeatedly alongside listening to audio recordings to ensure accuracy and familiarization with data. Initial thoughts on potential codes were noted.

Interview transcripts were uploaded onto Nvivo R1.5 for Windows for analysis. Accordingly, codes and themes were generated inductively, following a non-linear recursive and reflective process. Initial codes were collated, exported to Microsoft Word and reviewed by the supervising members of the research team. Consequently, the entire dataset was recoded to demonstrate progression from semantic to latent analysis. Codes were then organized into broader themes of significance and meaning then refined to ensure representation of the data set. Additionally, subthemes were created and some themes merged and disregarded. Finally, definitions were assigned to themes to ensure a clear scope for each theme.

Results

Participant Demographics

A total of 10 participants participated in the study. Participants were aged between 18 and 58 years with a mean age of 36 years. Strategically, self-identified ethnicity varied across the sample between Black African (n = 4), Black Caribbean (n = 3), mixed Black African, and Caribbean (n = 1) and Black British (n = 2). Similarly, level of educational attainment also varied with Bachelor’s degree (n = 5) the highest qualification reported followed by a level 3 vocational qualification (n = 1), and General Certificate of Secondary Education and other level 2 qualifications (n = 4). Current relationship status varied across the sample between “single” (n = 6), “married” (n = 2), “common law partnership” (n = 1) and “on a break” (n = 1). Notably, six participants reported being a father, of which, all reported having a daughter whilst three also had sons ()

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Qualitative Thematic Analysis

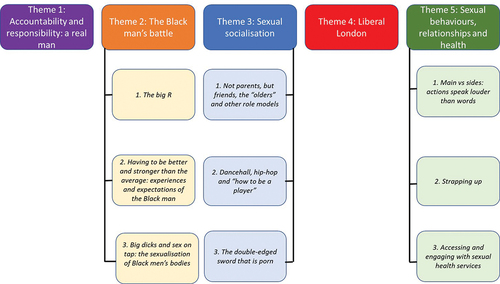

Five themes and nine subthemes were constructed (see for theme diagram). For relevance to the research questions, only themes 2 (the Black man’s battle), 3 (sexual socialization) and five (sexual behaviors, relationships, and health) will be discussed in this article. Crucially, themes are presented and accompanied with verbatim extracts from the anonymized interview transcripts to demonstrate the audit trail from data to themes (Meyrick, Citation2006).

Sexual Socialization

Participants’ experience of the sexual socialization process was uniquely shaped by the intersection of their race and gender.

Participants had little dialog with their parents about sex and relationships due to a generational divide where sex was viewed as a taboo subject within their culture:

With Nigerian culture, talking about sex and things like mental health, they’re very taboo subjects. It’s like you’ll turn 16 and your parents won’t talk to you about sex, but when you hit 25 they’ll be like “when are you going to make me a grandparent?” (Jay-Jay, 37)

At the same time, formal relationships and sex education were irrelevant to their needs:

I think it [relationships and sex education] was pointless man. It was just more of the science side of it. It actually wasn’t sex education. They were just telling us about body parts and stuff. (Ashley, 20)

When I speak to my brother, he’s been there, done that, so he knows [about sex and relationships]. Even though, obviously my parents have been there, he’s [my brother] a couple of years older than me so he understands where I’m coming from. (Ashley, 20)

The songs we were growing up with, rap songs and stuff like that. You used to hear rap lyrics talking about women with booties and stuff like that. That’s when we started to realize other components on women. Sexual kind of stuff. (Ryan, 34)

Music plays a big part. We listen to a lot of dancehall music. Them man are the first to say “man don’t do them tings there [perform oral sex].” We have adopted the Caribbean mentality here in England because in America, them man will tell you straight [they perform oral sex]. But I believe it’s down to the music culture. It’s promoted amongst Black people through our music. (Simon, 50)

There was loads of Black films back in the day, like Baby Boy, or How to Be a Player. Those kind of films that came out in the early 2000s portrayed this [having multiple partners] as the right thing to do. We were watching all those films portraying that kind of image of a Black man. (Ryan, 34)

Obviously it’s glorified in my music in my culture to have multiple partners. But as you grow up you realize that you can only build with one person so it changes your ideology. (Anton, 29)

You look at some pornstars, I always used to compare my manhood to theirs. I had this thing in my early sexual encounters, I always used to ask my partners “did you cum?” (Jay-Jay, 37)

Critically, the stigmatized nature of sex within certain Black communities made it difficult for participants to engage their parents in dialogue about sex and relationships. This resulted in greater reported reliance on informal sources of sex education such as peers and the media. The power of explicit media content (music, films and pornography) was influential on sexual socialization and education from a young age for Black men in this study. That power was reported to diminish with age and maturity, but demonstrates a gap around balanced relationships and sex education tailored for young Black men and their first experiences of relationships and sex.

Sexual Behaviors, Relationships, and Health

Participants described categorizing partners according to the nature of their relationship. However, whilst labels assigned to partners varied, participants generally identified a main partner who they perceived to have the most promising relationship with, and with whom they would allocate more efforts toward:

So in my mind, I have wifey. This would be my main girl. The one I would devote the bulk of my time to, take on dates, it’s not just about sex. We got a shared sense of working towards something, towards the future. (Jay-Jay, 37)

You got a main person, then it’s alright to bareback and explore. Then if you have others that it might only be sexual, then you might be like “if it’s just that then let me protect myself [use a condom].” (Anton, 29)

Several participants talked about negative experiences of using condoms which underpinned a pessimistic attitude toward condoms.

It [using a condom] definitely feels different. A bit more artificial. Definitely doesn’t feel intimate so to speak. The whole thing of sex, it can’t be done on an artificial tip. Well it can be done but you’re not getting the full benefit. (Anton, 29)

I think psychologically I associate using a condom with putting in a poor performance. There’s a psychological thing there where I think I can put in a better performance if I bareback. (Jay-Jay, 37)

Primarily, for some participants, the reason for using condoms was preventing STI acquisition, and this was tailored to trust levels in the different partner types or the suspicion that a partner was actively sexually involved with other men:

If I had an inkling that they [sexual partners] were sleeping with other people then yeah, it [the condom] just went on. (Daniel, 24)

Unquestionably, for Jay-Jay, this was the primary reason for their use, over and above for contraceptive purposes:

I think first and foremost it’s [reason for condom use] STI prevention. I just think STIs, especially AIDS, scare the hell out of me. I’m fortunate that I’ve never contracted an STI but I know people that have and it’s not pleasant when they’re telling you that it burns when they pee, or they have a horrible itch. It’s just always made me feel getting an STI, that’s gonna cause you some level of discomfort. (Jay-Jay, 37)

I think giving someone an STI, it’s kind of embarrassing in a way because a woman would think you’re not clean or you don’t know how to strap-up. For me personally, I see it as an attack on my personal hygiene. The fact that I’m having multiple sexual partners and not having regular tests between them, it’s kind of like a hygiene problem. (Ryan, 34)

Additionally, condom use with multiple partners was motivated by maintaining secrecy through not acquiring an STI:

Don’t get caught cheating first of all because if I catch something then she’ll definitely know that I’ve had sex with another girl. (Ashley, 20)

If you have a kid then its life changing, whereas if you get the short end of the stick in chlamydia or gonorrhea, or something that can be cured, then it’s not. You live to tell another day. (Anton, 29)

If you suspect a girl is sexually promiscuous, then that [reason for using condoms] becomes an STI. Whereas, if you don’t suspect she’s sexually promiscuous, but you don’t see her as the mother of your children, that becomes [reason for using condoms] pregnancy. (Martin, 41)

Use of Sexual Health Services

All participants reported experience of using sexual health clinical services. This was generally in response to STI symptoms:

Things were itching, things were scratching, or things were dripping (LAUGHS) and so it was important to get them seen to. (Marvin, 58)

They [sexual health clinics] open at certain times and obviously because I’m working, I can’t attend certain days. They were open from 9:00 until 14:00. I thought it would be a walk-in clinic, I’d see someone straight away. That wasn’t the case. I had to come back on another day. None of the days that I could have done so I just forgot about it. (Ryan, 34)

Engaging Black men more. Promote more. That’s the two main things. I think if there’s more stuff tailored for Black men, it needs to be promoted more. (Simon, 50)

I think we need to have early intervention where we encourage spaces where we as Black men congregate like barbers and food stalls markets, and just signpost. I know it sounds dumb, but even at raves, even if they have some kind of cubicle in the toilet where while you’re here in the toilet, why not have an STI test. (Jay-Jay, 37)

Obviously, they’ll [sexual health services] have to tap into Black organizations. Whether online, or face to face organizations. There are loads of Black organizations still operating. Nightclubs, places like that. Yes, people are going there to rave but why not? Why not do it in a social gathering? (Simon, 50)

The Black Man’s Battle

The Big R. Participants overwhelmingly described their experiences of racism as perpetrated by institutions rather than individuals. Although often experienced at a personal level, racism was seen as more systemic and structural in nature. Explicit racism could be avoided, but participants were voluntarily and involuntarily required to engage with institutions that perpetrated racism toward them:

We’re still getting arrested at massive rates, we’re still getting harassed on the streets by the Police. The education system is still failing us. It’s just they’re [people perpetrating racism] not calling us n****rs loudly anymore. So the change in behavior hasn’t created a change in outcome. I remember saying to my mum that the maths teacher was racist. My mum looked at me and said, “but you still have to learn maths from him.” (Marvin, 58)

Specifically, the Police were identified as an institution that engaged participants in racially motivated interactions:

I’ve been stopped by police. I like going for walks. It helps with my wellbeing. I remember when I was living at my mum’s and going for a walk. These undercover detectives came out of nowhere and were like “stop, there have been reports of a burglary and we need to search you.” They just searched me and there was no valid reason. It was just that I “fit the description” as always. (Jay-Jay, 37)

Furthermore, the racially motivated interactions included experiencing adultification (Davis & Marsh, Citation2020) as a boy as discussed by Daniel:

You get treated like a level up. The age group up that you are and you see things earlier and for what they really are. I was with my dad one time at the train station. I was probably 8 years old at the time. My dad was a bus driver and had a pass to go through on TFL [Transport for London]. My dad has walked through [the ticket barrier] and shown his badge. As I’m walking through I have been pulled aside by 2 police officers. I’m 8 years old. Two police officers now are questioning me as if I’m a teenager. (Daniel, 24)

Impact of Racism on Trust Towards NHS Services

Participants spoke of various ways their experiences of racism influenced their lives, including their engagement with health services. In this study, institutional racism personally experienced or witnessed created mistrust in health services which could result in avoidance until necessary:

I don’t even go to doctors because it’s a bag of shit, a mess. Unless I’ve got an infection. Not a sexual one, just an infection that you might need antibiotics for. My trust for that is weird. How you’re treated in the world, racism and stuff, you can’t help but see that people might do the same to you. (Anton, 29)

Big Dicks and Sex on Tap

In parallel, participants reported being subjected to racist sexual stereotypes and expectations from a young age. At a basic level, racist sexual stereotypes included expectations of Black male genitalia:

In my opinion, in terms of sex, everyone expects you to have a long dick because you’re Black, and then even more so because you’re tall and Black. There’s comments you get just based on that. (Daniel, 24)

I definitely knew that Black men were good at sex, White men were shit at sex, and that meant I had to be good at sex, didn’t it. We are supposed to be able to fuck good, and lots and often. I definitely knew that Black men had big cocks and White men had little cocks and that meant I had to have a big cock didn’t it. (Marvin, 58)

Moreover, the sexualization of Black male bodies extended to reported experiences of being fetishized by White women:

I suppose one of the things I noticed as a young person was how interested White people were in me sexually. Particularly older White women. I don’t know if that was something about me or about all kinds, but there was definitely a kind of energy from White women who were old enough to know better. I can name four boys in my year who were shagging White teachers at school and that, I know was a fact. That was part of how they saw their whiteness, the teachers, but also part of how they saw our blackness. And even at the time, I knew it had something to do with that. (Marvin, 58)

I feel like Black men are, because of all the porn that’s out there [in society], the ebony porn, depicts us to have large parts down there, it promotes or intrigues females from other cultures and they feel like they need to explore. So I do think sometimes you’re looked at as a bit of an exotic animal. (Anton, 29)

I know they [sexual health clinics] have a triage form and need to ask certain things. I guess when I’m disclosing that in the past 3 months, I have had X amount of partners, I always feel in their head they’re [the clinic staff] kind of judging me. (Jay-Jay, 37)

I can’t speak for all of them [Black men], but I think, let’s say a Black male was going through erection problems or whatever, I don’t think they’d feel comfortable saying that because of how Black males are meant to have tings that are as big as horses. You feel you’re not living up to expectations of you. (Anton, 29)

In one account, this stereotyping was seen in direct racism within clinical advice:

The first time I had sex properly was with a White girl. At the time, she went to a sexual health centre and she relayed that the sexual health nurse said she needs to get checked more regularly because she is having sex with Black men. (Ryan, 34)

It [experience at the sexual health clinic] was quite good, because obviously it’s confidential the way they treated it [the encounter]. Everything that they [the clinic staff] said will take place, took place. Would I have used it again? Oh, hell yes. (Simon, 50)

It [experience at the sexual health clinic] was a positive experience. The woman came to me, she was friendly, told me what the deal is and what’s gonna happen. It [the experience at the clinic] was very friendly, very open and helpful to be honest. (Kamal, 18)

Discussion

This study explored how the experience and understanding of being a Black man informed sexual attitudes, relationships and behaviors, with a focus on partnerships and condom use among Black heterosexual men with experience of concurrent sexual partnerships and condomless sex. As such, it drew on experiences of racism and how this informed their engagement with sexual health services.

Previous research has reported that among second and third generation ethnic minorities, the shared education, societal experiences and influences associated with being London born and educated may result in peer, urban youth culture through acculturation being more influential than ethnic-based cultural influences on sexual networks, behaviors, and beliefs (P. Connell, Citation2004; P. Connell et al., Citation2001). In this study, despite the diversity of cultures represented among participants, there were similarities in educational and societal experiences which influenced sexual attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. In short, participants’ experience of sex and sexual health could be seen through three elements of socializing in London.

First, participants were prematurely and frequently exposed to hypersexualized Black stereotyping in media content that was popular within their community, including films and hip-hop and dancehall music. Critically, the lack of maturity observed in pre-teenage years when participants started accessing these media content, and throughout adolescence meant they were less likely to regard the content absorbed as produced for entertainment purposes solely. Consequently, certain music videos and films became significant in the promotion and normalization of concurrent sexual partners. Similarly, these findings align with a previous qualitative study (Wayal et al., Citation2020) where participants perceived Black Caribbean popular music to encourage concurrent sexual partnerships, especially among men and young people. This matters because young Black men are said to find role models in male artists seen on television as these artists are often perceived as being relatable. They are typically of a similar age, usually come from disadvantaged backgrounds and vocalize stories of going from rags to riches (Greene, Citation2008).

Simultaneously, this was experienced in the context of little open and potentially “balancing” alternative sources of relationships and sex education (RSE), such as parent–child sexual communication and RSE tailored to experiences of young Black men. As a result, participants felt unable to seek advice, guidance, and accurate information from parents, instead turning to friends and older peers. The greater influence of peer-based messaging further reinforced harmful stereotypes. This was then externalized in a range of different partnership types such as “situationships,” “sides” and “mains,” and related levels of condom use in a complex, highly contextualized barometer of trust, safety, and potential parenting ability of partners. This mirrored the findings of a systematic review which reported that men increase their use of condoms in situations where they do not trust that their partner is being faithful to them (Fehr et al., Citation2015), and other related work evidencing condom use behavior is often moderated by partner type; hence, condoms are generally used with new or casual partners and abandoned as relationships become more serious (Carey et al., Citation2010; Chatterjee, Citation2006; Frye et al., Citation2013).

Generally, the relationship with a main partner was perceived as possessing the seriousness, familiarity and trust that eliminated the motivation to use condoms for STI prevention. Consequently, condom use with main partners was underpinned by pregnancy prevention intentions as the primary threat was perceived to arise from the potential lifelong implications of an unintended pregnancy, contradicting the narrative of the “absent Black father” (Coles & Green, Citation2010; Reynolds, Citation2009).

Secondly, being a Black man meant being subjected to and judged according to racist stereotypes that permeated multiple facets of participants’ lives, from interactions with institutions to expectations on sexual anatomy and performance. Participants described being exposed to sexual stereotypes from an early age through racialized pornography and experiencing fetishization. The impact of consuming racialized pornography included distorted perceptions of Black male genitalia, sexual performance and number of sexual partners. Beliefs that Black men possess giant penises and consequently inexhaustible sexual energy are commonly held (Meiu, Citation2009). Participants experienced similar instances of being fetishized and wanting to be “tried,” further compounding the awareness of expectations regarding the sexual anatomy and performance of Black men. These in turn led to a belief among participants that they should be having sex frequently.

Finally, as a group of racially marginalized men, participants experienced challenges across many aspects of their lives and a significant proportion of these were underpinned by racism. However, the way racism was experienced was reported to have changed. Crucially, racism had become less direct and obvious, but experienced as structurally perpetrated by institutions rather than from individuals. Racial biases were embedded across society, organizations and structures which marginalized participants and worsened their experiences e.g., the police and criminal justice system, the education system, the workplace, and the health service. However, unlike avoiding certain regions that could increase susceptibility to direct and individualized racial abuse, these were institutions and organizations that could not be avoided, and participants were forced to engage with from a young age. Subsequently, this created a lack of trust in institutions and organizations, and a perception that they did not care about Black people, including sexual health services.

Consequently, experiences of institutional racism discouraged these men from using sexual health services in two distinct ways. First, a fear of being judged, which is arguably common among many sexual health service users (Balfe et al., Citation2010; Hubach et al., Citation2022; Malta et al., Citation2020), but intensified by a fear of racialized projected stereotypes. To clarify, participants were aware of the hypersexualization of Black men and therefore found disclosure of important clinical information such as number of partners triggered fear of reinforcing those stereotypes. Secondly, a fear of judgment regarding genitals, especially among those who felt that their genitalia did not mirror society’s perception of what Black male genitalia is supposed to look like. Crucially, whether participants were being judged or not, the fear of being judged and the emotional consequences of this remained with them.

Fortunately, despite these fears, reported experiences of accessing sexual health services were overwhelmingly positive, with barriers mitigated by prior positive experiences. Prior positive experiences increased trust in services and promoted utilization. Trust in the health care system and providers has previously been reported as being among the top facilitators influencing young Black men’s engagement with sexual health services (Burns et al., Citation2021).

Implications for Practice

The study findings speak to the experiences of a small group of Black heterosexual men with experience of concurrent sexual partnerships and condomless sex, and as such require confirmation before being generalized. However, they also speak to potential nuanced understanding of an underserved population in sexual health.

First, the unique way that participants experienced sexual socialization suggests a role for school based and external RSE providers. It is important that young Black men are engaged in RSE that appropriately explores and counteracts the messages absorbed from peers and explicit media content, including music, film, and racialized pornography. Centrally, content that lacks diversity is likely to neglect the needs of young Black men who may be absorbing sexual messages from relatable hip-hop and dancehall artists who are perceived to better understand their social positioning than their often White female schoolteacher (Greene, Citation2008). Consequently, resources used for RSE should contain figures relatable to young Black men and better address the messaging in pornography and explicit media content.

Furthermore, a role for parents as educators was also identified. Whether through formal or informal dialog, or observations, it is important that young Black men are exposed to realistic depictions and accurate discussions regarding sex and relationships to counteract messages and expectations acquired from a young age about sexual lifestyles and behaviors. However, the stigmatized nature of sex within some Black communities (Cornelius & Xiong, Citation2015; Dennis & Wood, Citation2012; Kuo et al., Citation2016) may require development of interventions to equip parents of Black boys with the knowledge, skills and confidence to facilitate parent–child sexual communication.

Moreover, the challenge for sexual health services from these lived experience accounts suggest a need for targeted engagement and outreach work. For this group, experiencing symptoms prompted overcoming barriers to services but those who are asymptomatic may not be accessing routine STI testing. Positively, several suggestions were provided regarding how sexual health services can better engage Black men more generally, including the need to expand beyond the clinic into outreach venues that are largely populated by Black men. However, to prevent inappropriate racial profiling and the unintentional reinforcement of racist stereotypes regarding Black male sexuality, the work demands sensitivity, and where possible should be led by communities. As the experiences and behaviors of participants in this study will not be representative of the UK Black male population, initially services should seek to understand the sexual health needs of Black men within their local community, including how they prefer to access services and adapt to meet these needs.

Finally, the findings of this study contribute to the increasing recognition of trust as a barrier to health services, and therefore a determinant of health. Lack of trust in the health service, particularly among racially minoritized communities, discourages these populations from seeking help and support when needed (Georghiou et al., Citation2022). This was exemplified during the rollout of the coronavirus vaccine, during which vaccine uptake was lowest among Black ethnic groups (Razai et al., Citation2021; Robertson et al., Citation2021) because of a lack of trust in institutional information and healthcare providers (Halvorsrud et al., Citation2023). For this group, mistrust came from previous experiences of marginalization and institutional racism. Unfortunately, the medical profession has historically contributed to harming racially minoritized communities, including Black populations, which means rebuilding trust must occur at a systemic level (Khan, Citation2022). Crucially, this indicates a role for national bodies in sexual, reproductive and HIV healthcare, including the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH), the British HIV Association (BHIVA), and the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health (FSRH), to emphasize and promote the need to rebuild trust as a key strategy, including challenging stereotypes of Black male sexuality. In this study, trust in sexual health services was encouraged by previous positive experiences and professionalism, signifying the importance of maintaining and extending this through culturally informed outreach, especially among patients from racially minoritized communities.

Limitations

This study was subject to methodological limitations which must be considered. First, a purposive sampling strategy was adopted to maximize the variation in accounts of experiences obtained through demographic factors like age, ethnicity, employment status, and area of residence. However, the focused participant inclusion criteria restricted the understanding of experiences obtained to this participant group, with transferability of the findings left to the judgment of the reader (Meyrick, Citation2006). The study’s focus on participants with experience of higher-risk sexual behaviors means that the findings may not reflect the broader understanding and experience of being a Black man. Furthermore, the study’s focused inclusion criteria also meant that the experiences of certain subgroups, including recently arrived migrants, heterosexual-identifying men who have sex with men and those with more limited sexual experiences, were not obtained and remain understudied.

Second, of the sample, 50% were educated to degree level. Whilst there are no current data on degree attainment among Black men specifically, 26.4% of 25–64 year-olds in the UK have attained a Bachelor’s degree (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], Citation2022), and the higher educational attainment of these men may afford them certain socioeconomic privileges. Therefore, the voices and accounts of Black men in lower socioeconomic groups may not have been heard.

Additionally, the recruitment strategy of displaying posters on social media and in barbershops consequently placed the onus on interested individuals to contact the researcher and express an interest in participating. This may have limited the sample to those who possessed an interest in the topic being studied and the confidence and ability to contact the researcher and articulate their interest. However, the innovative nature of recruitment via a trusted community hub (barbershops) produced good results, unlike poster adverts in sexual health clinics. Furthermore, the main researcher was also a Black man which may have reassured participants, but also underlines the need to build diversity into both sexual health and research professions.

Finally, coronavirus pandemic restrictions introduced the potential for a skewed sample and obtained accounts of experiences as recruitment disruption caused by coronavirus restrictions meant that only people with an active presence on social media platforms would have been exposed to the study recruitment poster. Furthermore, data collection was limited to virtual interviews which may have impacted the nature of accounts obtained.

Recommendations for Future Research

This study uncovered a shocking dearth of broader research exploring Black masculinity and Black male sexuality in a UK context considering the long-evidenced higher disease burden. As a result, future research is required to increase academic understanding of the way masculinity and sexuality inform the experiences of Black men in a UK context, and to ensure that the understanding remains current and relevant. Critically, as the day-to-day experiences of Black men are often underpinned by racist stereotypes regarding Black masculinity and Black male sexuality, future research should counter narratives against dominant discourses which seek to further marginalize (Harper, Citation2009).

Notably, the qualitative nature of this study means the findings should be explored among the wider Black male population to ensure relevance before being used to underpin development of interventions. Such research should expand on the focused participant inclusion criteria used in this study to maximize the understanding of experiences obtained and increase the potential for transferability.

Additionally, we explored participants’ experiences of concurrent sexual partnerships and motivators of condom use within these. However, as this study did not distinguish between recurrent, first-time, one-time and unknown non-main partners, future research and intervention developers should explore and consider the dynamics of these partnerships, and how these moderate STI threat appraisals and subsequently condom use behavior in a UK context.

Furthermore, this study highlighted a lack of parent–child sexual communication between participants and their parents with barriers including a stigmatized perception of sex within some Black communities as well as being poorly served by formal RSE. Consequently, future research should explore this further and seek to understand how young Black boys in the UK wish to be supported by the range of sources of RSE, including their parents and formal RSE providers. Moreover, this should be complemented by research seeking to understand Black parents’ experiences of facilitating parent–child sexual communication, including successes and challenges encountered, to identify how to support them to confidently facilitate parent–child sexual communication.

Conclusion

The findings from the study contribute to the gap in research on Black masculinity and Black male sexuality in a UK context by highlighting the experiences and motivators of Black heterosexual men in London with experience of concurrent sexual partnerships and condomless sex. Critically, being Black males significantly underpinned the sexual socialization process for participants and subsequently informed their sexual attitudes, relationships, and behaviors. Furthermore, motivators for condom use were complex, multifaceted and situation dependent. Naturally, the nature of racism experienced shifted from individualized and direct racism, including the use of racial slurs, to institutional racism perpetrated by organizations that required frequent usage.

Unsurprisingly, experience of institutional racism created a lack of trust in services, whilst racist sexual stereotypes regarding Black male hypersexualization created a fear of judgment when accessing sexual health services. Nevertheless, participants were still willing to engage with sexual health services when prompted by symptoms of an STI and experiences were positive, rebuilding trust. Consequently, this study supports the emerging identification of trust as a determinant of health by highlighting the way experiences of institutional racism eroded participants’ trust in health services, but also how positive experiences and professionalism when accessing sexual health services counteracts mistrust and promotes engagement. Accordingly, leading advisory bodies including BASHH, BHIVA and FSRH should promote the rebuilding of trust among Black ethnic groups in strategies and policies, and build this through outreach, authentic community-led work and eradication of racist stereotyping in services.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (239.6 KB)Acknowledgments

Thank you to my participants for bravely volunteering to sit down and talk to me about their experiences. Thank you for keeping it real with me. Frankly, without you, this work would not have been possible. I hope I have given your voices the attention they deserve.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2382765

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term “Black” is widely accepted as a racial category; however, we refer to Black ethnic groups only when discussing sexual health outcomes throughout this manuscript as public health authorities collect and report STI epidemiological data according to ethnicity rather than race.

References

- Aicken, C. R., Wayal, S., Blomquist, P., Fabiane, S., Gerressu, M., Hughes, G., & Mercer, C. H. (2020). Ethnic variations in sexual partnerships and mixing, and their association with STI diagnosis: Findings from a cross-sectional biobehavioural survey of attendees of sexual health clinics across England. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 96(4), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053739

- Alexander, B. K. (2003). Fading, twisting, and weaving: An interpretive ethnography of the black barbershop as cultural space. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800402239343

- Anderson, M., Solarin, I., Gerver, S., Elam, G., MacFarlane, E., Fenton, K., & Easterbrook, P. (2009). Research note: The LIVITY study: Research challenges and strategies for engaging with the Black caribbean community in a study of HIV infection. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 12(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570701708584

- Balfe, M., Brugha, R., O’Donovan, D., O’Connell, E., & Vaughan, D. (2010). Triggers of self-conscious emotions in the sexually transmitted infection testing process. BMC Research Notes, 3(1), 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-229

- Bowleg, L., Burkholder, G. J., Massie, J. S., Wahome, R., Teti, M., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2013). Racial discrimination, social support, and sexual HIV risk among Black heterosexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0179-0

- Burns, J. C., Reeves, J., Calvert, W. J., Adams, M., Ozuna-Harrison, R., Smith, M. J., Baranwal, S., Johnson, K., Rodgers, C. R. R., & Watkins, D. C. (2021). Engaging young Black males in sexual and reproductive health care: A review of the literature. American Journal of Men’s Health, 15(6), 155798832110620. https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883211062024

- Carey, M. P., Senn, T. E., Seward, D. X., & Vanable, P. A. (2010). Urban African-American men speak out on sexual partner concurrency: Findings from a qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior, 14(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9406-0

- Chatterjee, N. (2006). Condom use with steady and casual partners in inner city African-American communities. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(3), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2005.018259

- Coles, R. L., & Green, C. (Eds.). (2010). The myth of the missing black father. Columbia University Press.

- Connell, P. (2004). Investigating ethnic differences in sexual health: Focus groups with young people. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 80(4), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2003.005181

- Connell, P., McKevitt, C., & Low, N. (2001). Sexually transmitted infections among Black young people in south-east London: Results of a rapid ethnographic assessment. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 3(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050152484731

- Connell, R. (1995). Masculinities. University of California Press.

- Cornelius, J. B., & Xiong, P. H. (2015). Generational differences in the sexual communication process of African American grandparent and parent caregivers of adolescents. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 20(3), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jspn.12115

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions (Nachdr.). Sage.

- Danso, A., & Danso, Y. (2021). The complexities of race and health. Future Healthcare Journal, 8(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0225

- Davis, J., & Marsh, N. (2020). Boys to men: The cost of ‘adultification’ in safeguarding responses to Black boys. Critical and Radical Social Work, 8(2), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1332/204986020X15945756023543

- Dennis, A. C., & Wood, J. T. (2012). “We’re not going to have this conversation, but you get it”: Black mother–daughter communication about sexual relations. Women’s Studies in Communication, 35(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2012.724525

- Dunlap, E., Benoit, E., & Graves, J. L. (2013). Recollections of sexual socialisation among marginalised heterosexual black men. Sex Education, 13(5), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2013.776956

- Fehr, S. K., Vidourek, R. A., & King, K. A. (2015). Intra- and inter-personal barriers to condom use among college students: A review of the literature. Sexuality & Culture, 19(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-014-9249-y

- Frye, V., Williams, K., Bond, K. T., Henny, K., Cupid, M., Weiss, L., Lucy, D., & Koblin, B. A. (2013). Condom use and concurrent partnering among heterosexually active, African American men: A qualitative report. Journal of Urban Health, 90(5), 953–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9747-x

- Furegato, M., Chen, Y., Mohammed, H., Mercer, C. H., Savage, E. J., & Hughes, G. (2016). Examining the role of socioeconomic deprivation in ethnic differences in sexually transmitted infection diagnosis rates in England: Evidence from surveillance data. Epidemiology and Infection, 144(15), 3253–3262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001679

- Georghiou, T., Spencer, J., Scobie, S., & Raleigh, V. (2022). The elective care backlog and ethnicity. Nuffield Trust. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/the-elective-care-backlog-and-ethnicity

- Gerressu, M. (2016). Understanding poor sexual health in Black British/Caribbean young men in London: A qualitative study of influences on the sexual behaviour of young Black men [ Doctoral thesis]. University College London. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1521018

- Gerressu, M., Elam, G., Shain, R., Bonell, C., Brook, G., Champion, J. D., French, R., Elford, J., Hart, G., Stephenson, J., & Imrie, J. (2009). Sexually transmitted infection risk exposure among Black and minority ethnic youth in northwest London: Findings from a study translating a sexually transmitted infection risk-reduction intervention to the UK setting. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(4), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.034645

- Gerver, S. M., Easterbrook, P. J., Anderson, M., Solarin, I., Elam, G., Fenton, K. A., Garnett, G., & Mercer, C. H. (2011). Sexual risk behaviours and sexual health outcomes among heterosexual Black Caribbeans: Comparing sexually transmitted infection clinic attendees and national probability survey respondents. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 22(2), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2010.010301

- Greene, J. S. (2008). Beyond money, cars and women: Examining black masculinity in hip hop culture. Cambridge Scholars.

- Grollman, E. A. (2017). Sexual health and multiple forms of discrimination among heterosexual youth. Social Problems, 64(1), 156–175. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spw031

- Halvorsrud, K., Shand, J., Weil, L. G., Hutchings, A., Zuriaga, A., Satterthwaite, D., Yip, J. L. Y., Eshareturi, C., Billett, J., Hepworth, A., Dodhia, R., Schwartz, E. C., Penniston, R., Mordaunt, E., Bulmer, S., Barratt, H., Illingworth, J., Inskip, J., Bury, F., … Raine, R. (2023). Tackling barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake in London: A mixed-methods evaluation. Journal of Public Health, 45(2), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac038

- Harper, S. R. (2009). Niggers no more: A critical race counternarrative on Black male student achievement at predominantly white colleges and universities. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390903333889

- Hubach, R. D., Zipfel, R., Muñoz, F. A., Brongiel, I., Narvarte, A., & Servin, A. E. (2022). Barriers to sexual and reproductive care among cisgender, heterosexual and LGBTQIA+ adolescents in the border region: Provider and adolescent perspectives. Reproductive Health, 19(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01394-x

- Jewkes, R., & Dunkle, K. (2017). Drivers of ethnic disparities in sexual health in the UK. The Lancet Public Health, 2(10), e441–e442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30182-2

- Khan, S. (2022). Rebuilding trust in medicine among ethnic minority communities. British Medical Association. https://www.bma.org.uk/news-and-opinion/rebuilding-trust-in-medicine-among-ethnic-minority-communities

- Krieger, N. (1999). Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services, 29(2), 295–352. https://doi.org/10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q

- Kuo, C., Atujuna, M., Mathews, C., Stein, D. J., Hoare, J., Beardslee, W., Operario, D., Cluver, L., & Brown, L. (2016). Developing family interventions for adolescent HIV prevention in South Africa. AIDS Care, 28(sup1), 106–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1146396

- Lacey, C. J. N., Merrick, D. W., Bensley, D. C., & Fairley, I. (1997). Analysis of the sociodemography of gonorrhoea in Leeds, 1989–93. BMJ, 314(7096), 1715–1715. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7096.1715

- Malta, S., Temple‐Smith, M., Bickerstaffe, A., Bourchier, L., & Hocking, J. (2020). ‘That might be a bit sexy for somebody your age’: Older adult sexual health conversations in primary care. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 39(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12762

- McDaid, L., Hunt, K., McMillan, L., Russell, S., Milne, D., Ilett, R., & Lorimer, K. (2019). Absence of holistic sexual health understandings among men and women in deprived areas of Scotland: Qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6558-y

- Meiu, G. P. (2009). ‘Mombasa Morans’: Embodiment, sexual morality, and samburu men in Kenya. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, 43(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2010.9707585

- Meyrick, J. (2006). What is good qualitative research?: A first step towards a comprehensive approach to judging rigour/quality. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(5), 799–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306066643

- Mitchell, H. D., Lewis, D. A., Marsh, K., & Hughes, G. (2014). Distribution and risk factors of trichomonas vaginalis infection in England: An epidemiological study using electronic health records from sexually transmitted infection clinics, 2009–2011. Epidemiology and Infection, 142(8), 1678–1687. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268813002902

- Mohammed, H., Blomquist, P., Ogaz, D., Duffell, S., Furegato, M., Checchi, M., Irvine, N., Wallace, L. A., Thomas, D. R., Nardone, A., Dunbar, J. K., & Hughes, G. (2018). 100 years of STIs in the UK: A review of national surveillance data. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 94(8), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2017-053273

- Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). Sexually transmitted infections: Adopting a sexual health paradigm (S. H. Vermund, A. B. Geller, & J. S. Crowley, Eds.). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25955

- Nwaosu, U., Raymond-Williams, R., & Meyrick, J. (2021). Are psychosocial interventions effective at increasing condom use among Black men? A systematic review. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 32(12), 1088–1105. https://doi.org/10.1177/09564624211024785

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2022). Education at a glance 2022: OECD indicators. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en

- Polgar, S., & Thomas, S. (2000). Introduction to research in the health sciences (4th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Public Health England. (2019). Sexually transmitted infections and screening for Chlamydia in England, 2018. Public Health England. https://pcwhf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/hpr1919stis-ncspann18.pdf

- Public Health England. (2020). Beyond the data: Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-understanding-the-impact-on-bame-communities

- Public Health England. (2021). Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1015176/STI_NCSP_report_2020.pdf

- Razai, M. S., Osama, T., McKechnie, D. G. J., & Majeed, A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ, n513. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n513

- Reed, E., Santana, M. C., Bowleg, L., Welles, S. L., Horsburgh, C. R., & Raj, A. (2013). Experiences of racial discrimination and relation to sexual risk for HIV among a sample of urban Black and African American men. Journal of Urban Health, 90(2), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9690-x

- Reynolds, T. (2009). Exploring the absent/present dilemma: Black fathers, family relationships, and social capital in Britain. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 624(1), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209334440

- Rice, B., Delpech, V., Sadler, K. E., Yin, Z., & Elford, J. (2013). HIV testing in Black Africans living in England. Epidemiology and Infection, 141(8), 1741–1748. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026881200221X

- Roberts, M. E., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Weng, C.-Y., Murry, V. M., Simons, L. G., Simons, R. L., & Lorenz, F. O. (2012). From racial discrimination to risky sex: Prospective relations involving peers and parents. Developmental Psychology, 48(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025430

- Robertson, E., Reeve, K. S., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Moore, J., Blake, M., Green, M., Katikireddi, S. V., & Benzeval, M. J. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 94, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008

- Rossman, G. B., & Rallis, S. F. (2003). An introduction to qualitative research: Learning in the field (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Savage, E., Leong, G., Peters, L., Duffell, S., & Hughes, G. (2011). P1-S5.46 Assessing the relationship between sexually transmitted infection rates, ethnic group and socio-economic deprivation in England. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 87(1), A195.2–A196. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2011-050108.224

- Sim, J., & Waterfield, J. (2019). Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Quality & Quantity, 53(6), 3003–3022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00914-5

- Wayal, S., Aicken, C. R. H., Griffiths, C., Blomquist, P. B., Hughes, G., Mercer, C. H., & Zhang, L. (2018). Understanding the burden of bacterial sexually transmitted infections and trichomonas vaginalis among Black caribbeans in the United Kingdom: Findings from a systematic review. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208315

- Wayal, S., Gerressu, M., Weatherburn, P., Gilbart, V., Hughes, G., & Mercer, C. H. (2020). A qualitative study of attitudes towards, typologies, and drivers of concurrent partnerships among people of Black Caribbean ethnicity in England and their implications for STI prevention. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8168-0

- Wayal, S., Hughes, G., Sonnenberg, P., Mohammed, H., Copas, A. J., Gerressu, M., Tanton, C., Furegato, M., & Mercer, C. H. (2017). Ethnic variations in sexual behaviours and sexual health markers: Findings from the Third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet Public Health, 2(10), e458–e472. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30159-7

- Wayal, S., Reid, D., Blomquist, P. B., Weatherburn, P., Mercer, C. H., & Hughes, G. (2018). The acceptability and feasibility of implementing a bio-behavioral enhanced surveillance tool for sexually transmitted infections in England: Mixed-methods study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(2), e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.9010