ABSTRACT

Authoritarianism emerges in times of societal threat, in part driven by desires for group-based security. As such, we propose that the threat caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with increased authoritarian tendencies and that this can be partially explained by increased national identification. We tested this hypothesis by collecting cross-sectional data from three different countries in April 2020. In Study 1, data from Ireland (N = 1276) showed that pandemic threat predicted increased national identification, which in turn predicted authoritarianism. In Study 2, we replicated this indirect effect in a representative UK sample (N = 506). In Study 3, we used an alternative measure of authoritarianism and conceptually replicated this effect among USA citizens (N = 429). In this US sample, the association between threat and authoritarian tendencies was stronger among progressives compared to conservatives. Findings are discussed and linked to group-based models of authoritarianism.

On March 11th 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic (Cookson, Citation2020), prompting radical action by national governments aimed at slowing the viral spread (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). Often, these actions included closing national borders, restrictions on social behavior, and appeals to national unity. In other words, many governments adopted authoritarian stances to contain the virus.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its implemented countermeasures represent a threat to community health and social stability more generally. COVID-19 has created a devastating death toll alongside a dramatic fall in GDP and employment. Such a pandemic is a unique form of societal threat requiring collective action on an international scale. The threat of the COVID-19 pandemic along with its countermeasures apply equally to health, economic, and social conditions more generally (Van Bavel et al., Citation2020). We characterize this form of societal threat as pandemic threat to convey the scale and depth of public concern.

Under conditions of societal threat, people commonly endorse authoritarian responses (see, Duckitt & Fisher, Citation2003) and this may in part be associated with group-based concerns. Indeed, attempts to foster national unity can undermine tolerance and inclusiveness (López-Alves & Johnson, Citation2018; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2018), especially when driven by threat. At times, during the COVID-19 outbreak national rhetoric explicitly attributed the source of this threat to national out-groups. Other times, these attempts more indirectly amplified the need for order, compliance, and patriotism (Jetten et al., Citation2020). Such security motivated appeals that foster national identity are strongly associated with authoritarianism (e.g., Osborne et al., Citation2017).

The context of COVID-19 provides a novel chance to examine the associations between pandemic threat, authoritarianism, and national identification. In particular, we investigate if pandemic threat is associated with authoritarian tendencies in the general public, and if this is linked to a threat-induced rise in national identification. The article presents three studies that test these proposals in Ireland, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (USA) during the early stages of COVID-19 induced national lockdowns.

Threat increases authoritarianism

In psychological terms, authoritarianism is characterized by respect for authority, desire for order, and fear of outsiders (Altemeyer, Citation1996; Funke, Citation2005). Those high in authoritarianism are more likely to support national governments (Osborne et al., Citation2017), hold socially conservative views (e.g., Van Hiel et al., Citation2004), and display prejudice toward outgroups (Mavor et al., Citation2009; McCann, Citation2008).

The association between threat and authoritarianism is well established (Adorno et al., Citation1950; Fromm, Citation1941; Sales, Citation1973). For example, Fromm (Citation1941) noted the societal instability of the early 20th century as a key antecedent to the rise of authoritarian regimes in 1930’s Europe. On a more individual level, Adorno et al. (Citation1950) framed a fearful childhood environment as the root of authoritarian personality. On a national scale, Sales (Citation1973) analysis of authoritarian policy demonstrated that police budgets, power themes, and prison sentences each tend to increase during times of societal threat. Societal threats are those with the potential to cause harm to large sections of the population (e.g., economic crashes, terrorist threats; Fritsche et al., Citation2011). In times of societal threat, research has shown that the endorsement of authoritarianism increases (Altemeyer, Citation1996; Cohrs et al., Citation2005; Doty et al., Citation1991; Duckitt & Fisher, Citation2003).

Arguably, a pandemic provides ideal conditions for authoritarianism to emerge. As previously highlighted, the COVID-19 global pandemic and its countermeasures have disrupted social order and devastated economic systems (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). Concurrently, authoritarianism partially stems from the threat of social disorder, and those who display authoritarian tendencies strongly fear the actions of social deviants (Kreindler, Citation2005). For example, after the World Trade Center attack of 9/11, authoritarian reactions were positively associated with motivational goals of social control (Cohrs et al., Citation2005). Consistently, there is already evidence that COVID-19 salience increases support for socially conservative policies and candidates (Karwowski et al., Citation2020).

In part, pandemic threat enhances the appeal of authoritarianism by emphasizing the danger of others in an indiscriminate fashion. During a pandemic, every person we encounter poses the threat of infection and mitigation strategies emphasize this fact. In general, perceiving others as more threatening or dangerous can increase levels of authoritarianism (Duckitt et al., Citation2002). In particular, authoritarian traits such as moralization and the condemnation of others may be rooted in the threat of contamination (Haidt & Graham, Citation2007; Wagemans et al., Citation2018). Under threat, people often seek safety in a more cohesive, conservative, and orderly society (Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009) and authoritarian leadership at a national level offers this enhanced social control and group cohesion. In the following section, we make the case that pandemic threat enhances commitment to the national group in particular.

The role of national identification

We argue that national identification has a role to play in linking pandemic threat to authoritarian tendencies. On a general level, in-group identification can assuage feelings of threat and social uncertainty (Guinote et al., Citation2006; Hogg, Citation2007). However, when in-group identification takes a nationalist form, authoritarianism frequently follows (e.g., Osborne et al., Citation2017). Indeed, many models that link threat and authoritarianism highlight the role of in-group identification (Feldman & Stenner, Citation1997; Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009).

Group-based models of the link between threat and authoritarianism emphasize the role of social attitudes and intergroup dynamics (Duckitt, Citation2001; Duckitt et al., Citation2002; Kreindler, Citation2005). For example, the social cohesion model suggests that authoritarian tendencies primarily reflect people’s desire to identify with in-groups and adhere to in-group norms. Similarly, the dual group process model (Kreindler, Citation2005) specifies that both threat and in-group identification are necessary preconditions of authoritarianism. Although these models differ in the extent to which they focus on the desire to protect in-group norms (Kreindler, Citation2005), versus broader social cohesion (Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009), both emphasize the role of in-group identification as a precursor to authoritarianism. This is central to our claim that national identification can serve to link pandemic threat and authoritarianism, in certain contexts.

In times of pandemic threat, large-scale social categories such as the nation, can provide solace and a source of solidarity (e.g., Reicher et al., Citation2010). Indeed, increased national identification in response to political, health, and economic threats has been well documented (Bartolucci & Magni, ; Drury et al., Citation2009; Jay et al., Citation2019). These feelings of connection to others reduce the distress invoked by different forms of threat (Schmid & Muldoon, Citation2015) and identification with a majority group enhances feelings of control (Fritsche et al., Citation2013; Guinote et al., Citation2006), and reduces feelings of uncertainty (Hogg, Citation2007). When social conditions lead individuals to lack feelings of control (e.g., pandemic restrictions), identifying with powerful in-groups can serve as compensation (Fritsche, Citation2013). Importantly, the protection provided by in-group identification is contingent upon levels of group unity and coherence, which can be seen as both a precursor and a consequence of identification (Postmes et al., Citation2013; Roth et al., Citation2019). During a pandemic, a strong sense of national identification may help coordinate collective efforts to manage threat, and foster in-group solidarity (Jetten et al., Citation2020). Heightened national identification and the perceived necessity for people to behave in line with national group norms creates an ideal environment for authoritarianism to emerge. In general, both nationalism and patriotism are positively associated with authoritarian tendencies (e.g., Osborne et al., Citation2017). As stated above, authoritarians favor group conformity, the punishment of non-conformists, and obedience toward group leaders (Duckitt, Citation1989). Consistent with the social cohesion model (Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009), this stems from the belief that stronger, more cohesive in-groups will provide more protection against external threats (Van Leeuwen & Park, Citation2009). Indeed, authoritarians tend to categorize out-groups as immoral and socially deviant (Jackson & Gaaertner, Citation2010; Shaffer & Duckitt, 2013). Thus, the appeal of authoritarianism should depend on the perceived need for others to comply with group norms. During a global pandemic, the necessity for collective adherence to social restrictions that are mandated at a national level enhances this need among the general public. At least to the extent to which they identify with the national group. The above research suggests that the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism should be partially accounted for by national identification. If the protection sought in authoritarianism is associated with a desire for national cohesion, its appeal should be partially driven by national in-group identification.

Research to date on pandemic threat and authoritarianism

Previous research has investigated the link between different forms of disease threat and authoritarianism (e.g., Sturmer et al., Citation2017; Tybur et al., Citation2016). In most cases, studies linking threat to prejudice explore authoritarianism as a moderator. For example, Stürmer et al. (Citation2017), studied responses to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in the Western countries. They found that perceived vulnerability to disease and support for quarantining migrants was associated with authoritarianism. However, the threat of Ebola itself was not associated with authoritarianism. Similarly, Green et al. (Citation2010) found that Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), a highly related concept (Pratto et al., Citation1994), was associated with germ aversion, but not with the more contextualized threat of the avian influenza pandemic. More recently however, Hartman et al. (Citation2021) found evidence that COVID-19 threat specifically was significantly correlated with the endorsement of authoritarian beliefs in both the UK and Ireland. These authors also assessed authoritarianism as a moderator, and found that COVID-19 anxiety was associated with prejudice at high, but not low, levels of authoritarianism.

The above research demonstrates somewhat conflicting results regarding the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism. On the one hand, Ebola or avian flu threat was not associated with authoritarianism, but on the other hand COVID-19 anxiety was associated with authoritarianism. Importantly, these previous studies conceptualize authoritarianism as a stable inter-individual variable. Unlike these previous studies, and in line with research that has clearly demonstrated a link between threats in general and authoritarianism, we frame authoritarianism as a reaction to societal threats that are linked to the desire for group cohesion. From this perspective, the above discrepancies emerge because of the scale of the threat COVID-19 provides to participants is much greater compared to Ebola or avian flu threat. Put simply, Ebola and avian flu did not provide a societal threat in Western nations the way COVID-19 clearly has. In support of this argument, a large-scale study of over 30 nations found that parasite stress consistently predicted traditionalism (Tybur et al., Citation2016), which is an aspect of authoritarianism that concerns in-group norm adherence.

The current research

In the present research, we study the endorsement of authoritarianism as a motivated response to pandemic threat (as opposed to a dispositional underlying ideology that amplifies threat). In line with this reasoning, experimental manipulations have demonstrated that COVID-19 threat increases conservativism (Karwowski et al., Citation2020) and authoritarian tendencies (Blanchet & Landry, Citation2021; Golec de Zavala et al., Citation2021). Consistent with group-based models on authoritarianism that highlight the role of in-group identification, we investigate national identification as a psychological variable that mediates the expected association between threat and authoritarianism. Specifically, we propose that threat can increase the appeal of authoritarianism by enhancing identification with the national group.

Methodological overview

We test a simple mediation model across three different national samples. If part of the association between pandemic threat and authoritarian tendencies can be attributed to a rise in national identification, then in each sample the association between pandemic threat and national identification should in turn explain a proportion of variance in authoritarianism. Across three studies, we test the presence of the predicted indirect effect in each sample. With the present research design we will not demonstrate causation, but we rather aim to identify the hypothesized pattern of findings that is consistent with our overarching theoretical framework across three different nations. In Study 1, we recruited a large community sample of Irish residents, in Study 2 we recruited a nationally representative UK sample, and in Study 3 we tested the same model in a USA sample and sought to further explore the role of political conservatism.

In each study we also test the robustness of our model and assess plausible alternatives (Fiedler et al., Citation2018). In line with the pandemic threat research highlighted above (e.g., Hartman et al., Citation2021) we will test alternative models that frame authoritarianism as a moderator between threat and national identification. On a theoretical level, the alternative model proposes that latent authoritarianism is activated by threatening conditions, and this drives nationalist sentiment. However, we propose that threat can drive national identification, and that national identification has a key role to play in driving authoritarian responses. In particular, authoritarian responses represent an expression of the desire for national group cohesion (Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009). Unlike previous examples of threat-induced authoritarianism (Jost et al., Citation2003), we hypothesize that these effects are not confined to the politically conservative (Yun et al., Citation2019). This is because a pandemic is widely regarded as a legitimate threat to social order by all, and not only by those more sensitive to societal dangers. Accordingly, we test the predicted indirect effect with and without controlling for political conservatism in each sample.

Study 1: Ireland

The aim of Study 1 was to test the predicted indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism through national identification in a community sample of Irish residents.

The first confirmed COVID-19 case on the Island of Ireland was on February 27th 2020 and just under two weeks later, March 10th, 2020, the first death was recorded. In the Republic of Ireland, the acting government responded with partial lockdown by March 13th when many businesses, public buildings, and all education facilities were required to close. By March 24th all non-essential businesses were closed in both Northern Ireland and the Republic. Private health services were brought into public control and comprehensive emergency support payments were implemented in the Republic of Ireland.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 1800 participants by sharing a survey link on various social media platforms from April 7th,2020. Only participants who fully completed the measures for the present research question were included in analyses. This resulted in a sample of 1276 participants (Mage = 39.08, SD = 14.64, range 18–79 years); 1007 identified as women, 255 as men, three as non-binary, one as transgender, and eight undisclosed.

Materials and procedure

The present survey was part of a wider project that included several measures (for the full survey see; https://osf.io/bs897/?view_only=None), here we describe measures relevant for the present research question.

Authoritarianism

An adapted version of the six-item very short authoritarianism scale (VSA; Bizumic & Duckitt, Citation2018) was employed. Before data collection commenced, we removed one item discussing gay marriage and abortion. These issues have recently been the subject of referenda in Ireland that could have influenced the integrity of the measurement. This left us with a five-item scale. Responses were recorded on a 9-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 9 = very strongly agree, (e.g., “What our country needs most is discipline, with everyone following our leaders in unity”; α = .59).

Pandemic threat

We designed a six-item measure of pandemic threat adapted from (Brug et al., Citation2004) to assess threat to health (e.g., “COVID-19 is a threat to the health of people in the national community”) and societal threat (e.g., “COVID-19 will cause economic collapse in my country”). Items were assessed on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; α = .66).Footnote1

National identification

We assessed national identification with the validated single item measure of social identification, “I identify with the national community” rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).Footnote2 Despite being a single item measure it has been shown to correlate well with multi-item measures of social identification and it is estimated to have good reliability (Postmes et al., Citation2013, also see Reysen et al., 2013).

Political conservatism

We assessed general social and economic conservatism by averaging two items on 10-point scales (r = .51), “In general, how liberal or conservative are you on social issues?” (1 = very liberal; 10 = very conservative), and “In general, how left-wing or right-wing are you on economic issues?” (1 = very left-wing; 10 = very right-wing). Higher scores indicate more politically conservative views.

Results and discussion

displays zero-order correlations between all four variables of interest. As predicted, pandemic threat was positively correlated with both national identification and authoritarianism. Furthermore, national identification was positively correlated with authoritarianism.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables.

Mediation analysis

We tested whether the effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism could be partly explained by national identification using mediation analysis. Specifically, ordinary least square path analysis (OLS) and 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples were used to estimate an indirect effect. As anticipated, pandemic threat significantly predicted higher levels of national identification, β = 0.13, SE = 0.04, t(1266) = 4.67, p < .001, 95% CI [0.11,0.27] and national identification predicted authoritarianism, controlling for pandemic threat, β = 0.17, SE = 0.03, t(1265) = 6.10, p < .001, 95% CI [0.12,0.24]. More importantly, the indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism via national identification was statistically significant, β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04].

We further assessed the robustness of this effect by adding political conservatism as a covariate. The indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism through national identification was maintained when controlling for conservativism, β = 0.01, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.004, 0.020] indicating that the relationship between pandemic threat and authoritarianism via national identification is independent from political orientation.Footnote3

Alternative models

In line with Fiedler et al. (Citation2018)’s guidelines for best practice in assessing cross-sectional mediation models, we tested two theoretically plausible alternative models for explaining the relationships between these variables. First, we examined authoritarianism as a moderator of the association between threat and national identification. We regressed national identification onto pandemic threat, authoritarianism (both mean centered) and their interaction. This analysis revealed a non-significant interaction effect, β = −0.03, SE = 0.25, p = .898. Thus, authoritarianism did not moderate the association between threat and national identification.

Next, we investigated authoritarianism as a mediator of the association between pandemic threat and national identification. More specifically we reversed the variables in the b path of our initial model and tested the indirect effect of threat on national identification via authoritarianism. This indirect effect was significant, β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04]. Thus, we cannot rule out this alternative possibility with our Study 1 sample.

These results support our overall hypothesis that national identification partially accounts for the relationship between pandemic threat and authoritarianism. However, given the large overlap in variance across these three measures, we cannot rule out an alternative mediation model. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the implemented authoritarianism measure was low. We require a more precise measure of authoritarianism to disentangle these indirect effects in a further study. However, first, we assessed the support for our hypothesized model with a different national sample.

Study 2: the United Kingdom

The aim of Study 2 was to replicate the indirect effect identified in Study 1, in a different national context. This will provide support for the robustness of our findings as well as its generalizability across different nations.

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the UK was on January 31st, and by March 5th the first death was recorded. Businesses and institutions were advised to close voluntarily in March and by March 23rd the closure of all public buildings and all non-essential businesses was mandated. The UK operates a free national public health system for citizens and within days of the lockdown a job retention scheme and job subsidy scheme were launched. On March 27th, the Prime Minister Boris Johnson tested positive for COVID-19 and was hospitalized for ten days, including three days in intensive care, before making a full recovery.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited on April 11th 2020 from Prolific, a crowdsourcing platform providing nationally representative UK samples, in terms of gender, race, and age. We recruited 506 participants (Mage = 45.48, SD = 15.17, range 19–78 years); 257 women, 248 men, one participant indicated “other.”

Measures

Pandemic threat (α = .76), authoritarianism (α = .74), national identification, and political conservatism (r = .72) were assessed as described in Study 1.

Results and discussion

displays zero-order correlations between all four variables of interest. As in the Irish sample, pandemic threat was positively correlated with both national identification and authoritarianism, and national identification was positively correlated with authoritarianism.

Mediation analysis

As in Study 1, we used OLS and bias-corrected bootstrapping as to estimate the indirect effect. The effect of pandemic threat on national identification was again positive and statistically significant, β = 0.16, SE = 0.04, p < .001, 95% CI [0.07, 0.24]. The effect of national identification on authoritarianism, controlling for pandemic threat was also positive and statistically significant, β = 0.25, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.15, 0.34]. As hypothesized, there was a statistically significant indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism via national identification, β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.06]. Thus, in line with the results of Study 1, increased national identification in response to pandemic threat partially accounted for how pandemic threat is related to authoritarianism. The same mediation model including political conservativism as a covariate (see Study 1) demonstrated the robustness of the indirect effect via national identification, β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01,0.03]. This provides further evidence that the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism is not attributable to differences in political conservatism, but to increased national identification in the general public in response to pandemic threat.Footnote4

Alternative models

We again tested two alternative models of the association between pandemic threat, national identification and authoritarianism. The results corresponded with our Study 1 findings. Specifically, the threat × authoritarianism interaction was not a significant predictor of national identification, b = 0.04, SE = 0.04, t(501) = 1.05, p = .293. However, the indirect effect of threat on national identification through authoritarianism, was significant, β = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.02, 0.08]. Therefore, this alternative pattern of mediation could not be ruled out as a plausible model of our findings.

The replication of results across two studies in different political contexts points to the robustness of the findings as well as its generalizability across different nations. However, we used a short scale of authoritarianism in both instances. As these studies were part of larger surveys, the use of short scales was necessary for the sake of brevity. To counter any possibility that we may have missed some dimension of the authoritarianism concept, in Study 3 we used a more comprehensive measure of authoritarianism. Furthermore, we sought to use this more reliable measure to test alternative mediation models that could not be ruled out in Study 1 or 2.

Study 3: the United States of America

We aimed to test the stability of our mediation model in a third context, and with a more reliable and comprehensive measure of authoritarianism (Funke, Citation2005). These improved measurements and unique study context allowed us to replicate the link between pandemic threat and authoritarianism in more depth, by assessing the role of conservativism in a polarized political climate.

In the USA, a particularly strong partisan divide emerged in response to COVID-19 and the implemented countermeasures, such that individuals on the conservative political right (i.e., “Republicans”), expressed less concern for their health than individuals with more liberal positions (i.e., “Democrats”; Allcott et al., Citation2020; Gollwitzer et al., Citation2020). This presents a situation where people who typically endorse authoritarian values (i.e., conservatives; Bizumic & Duckitt, Citation2018), potentially experienced less threat in response to COVID-19. Thus, we explore if the relationship between threat and authoritarianism is more evident in those with less politically conservative views. This finding would support the predominance of social threat as a driver of authoritarianism, regardless of underlying political ideology. This is a core assumption of the model we present.

To provide context, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the USA was on January 20st and the first death on February 29th. There was no full lockdown imposed at a federal level, but State governors made independent decisions about shelter-in-place rules. By March 31st, 42 out of 50 states had instituted full or partial lockdowns.

Method

Participants

We ran Monte-Carlo simulations with Study 1 and 2 correlation estimates to determine that a minimum sample of 420 participants was required to achieve 80% power for a simple mediation model (Schoemann et al., Citation2017). Our USA sample of 429 participants (Mage = 40.82, SD = 14.09, range 18–89 years; 180 women, 248 men and one with non-disclosed gender) was recruited on May 9th 2020 using MTurk; a crowdsourcing platform.

Materials and procedure

The full survey is available at https://osf.io/bs897/?view_only=None.

Threat and national identification

Pandemic threat (α = .81) and national identification were assessed as described in Study 1.

Authoritarianism

A more comprehensive measure of authoritarianism was employed in Study 3. The right-wing authoritarianism scale (RWA3 D; Funke, Citation2005) captures three aspects of the construct; aggression, submission, and conventionalism. An example item states “What our country really needs instead of more ‘civil rights’ is a good stiff does of law and order.” Responses are given on a 9 point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 9 = strongly agree) As in Studies 1 and 2, we used this measure to assess global authoritarianism (α =.86). Please see supplementary materials for a subscale analysis.

Political conservatism and political identification

Alongside the political conservatism measures, used in Studies 1 and 2 (r = .72 in Study 3), we additionally asked participants; “Which of the following political categories do you identify most with? – Republican; Democrat or Independent” as a measure of political identification.

Results and discussion

displays the zero-order correlations between pandemic threat, national identification, and authoritarianism. As before, pandemic threat was positively, and significantly, correlated with national identification and national identification was similarly correlated with authoritarianism. However, in this US sample, threat did not significantly correlate with authoritarianism.

As anticipated, we found evidence that political conservativism was negatively correlated with pandemic threat (r = −.18, p < .001). We further explore these findings below.

Pandemic threat, political identification and conservatism

We anticipated that the US political climate would influence the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism is this sample. US Republicans are typically high in authoritarianism. Indeed, authoritarianism scores in this sample were significantly higher for Republicans (M = 5.38, SD = 0.94) compared to Democrats (M = 4.21, SD = 1.45), t(332) = 8.28, p < .001, d = 0.96.Footnote5 However, this group were encouraged to dismiss the threat of the virus by their political leaders. This would serve to supress the correlation between pandemic threat and authoritarianism. To investigate this, we assessed how the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism interacts with conservativism in this sample. An independent samples t-test confirmed significantly higher pandemic threat for those identifying as Democrats (M = 5.25, SD = 0.92) compared to Republicans (M = 4.87, SD = 1.32), t(334) = 2.94, p = .004, d = 0.34.

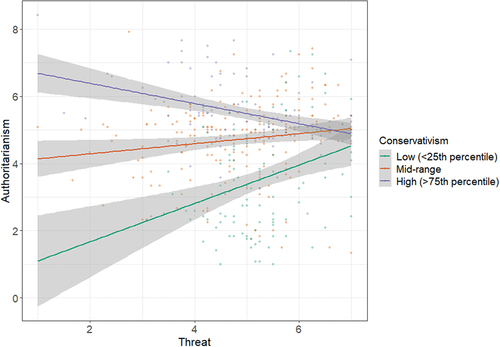

We further tested if political conservativism moderated the effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism using regression analysis. Specifically, we regressed authoritarianism onto pandemic threat, political conservatism (both mean centered) and their interaction. Both threat, b = 0.71, SE = 0.13, p < .001 and conservativism, b = 0.82, SE = 0.10, p < .001 significantly predicted authoritarianism. As anticipated, the threat × political conservatism interaction was significant, b = −0.10, SE = 0.02, p < .001. At low levels of conservativism (−1SD), higher threat predicted higher authoritarianism, b = 0.43, SE = 0.09, p < .001, however, this effect was not present among those high in conservativism (+1SD), b = −0.08, SE = 0.05, p = .109. Thus, pandemic threat was associated with authoritarianism among a subsection of the sample not typically inclined toward authoritarian responses. displays this interaction pattern.

Mediation analysis

To test our main model, we used the same mediation analysis described in Studies 1 and 2. Again, pandemic threat significantly predicted higher levels of national identification, β = 0.23, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.32], which in turn predicted authoritarian tendencies, β = 0.30, SE = .05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.40]. Crucially, there was a significant indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarian tendencies through national identification, β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.10]. Again, this indirect effect remained significant after controlling for political conservatism, β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07].Footnote6

Alternative models

Given the cross-sectional nature of our findings, it is particularly important that we rule out plausible alternative models for our findings (Fiedler et al., Citation2018). As above, we tested if authoritarianism moderated the association between threat and national identification by assessing the authoritarianism × threat interaction. This interaction effect was again, small and non-significant, b = −0.01, SE = 0.04, p = .725. Again, we investigated if authoritarianism mediated the association between threat and national identification. Given the consistent correlations between all three variables, this could not be ruled out in previous studies. Using the more precise measure of authoritarianism administered in this study, we found that there was no significant indirect effect of threat on national identification through authoritarianism, β = 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = .12, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.05]. This gives us additional confidence in the theoretical model we propose.

In summary, we found the hypothesized indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism in a third sample of participants. Furthermore, we found that conservatives experienced lower pandemic threat compared to liberals and the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism was confined to those at lower levels of political conservatism. This further supports our claim that pandemic threat is driving authoritarianism as mediational findings are unlikely to be explained by right-wing “authoritarians” experiencing higher national identification, and higher threat.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic threatened social order and stability on a global scale. Many governments have implemented severe restrictions on social movement, often framed as being for the good of the nation. In this context, and in line with group-based accounts of authoritarianism, we proposed that authoritarian tendencies could emerge from the degree to which people identify with the national group in response to pandemic threat.

Across three different countries, we found evidence supporting the hypothesis that pandemic threat increases authoritarianism and that this effect could be partly attributed to national identification. The plausibility and robustness of these findings is further demonstrated by the fact that the indirect effect of threat on authoritarianism through national identification remains stable after controlling for political conservatism in all three samples, and after using an alternative measure of authoritarianism (Study 3).

Importantly, Study 3 demonstrated that pandemic threat was more strongly associated with authoritarianism for less conservative individuals. Specifically, there was no positive association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism among those who reported high political conservativism. In the USA, attitudes toward COVID-19 rapidly diverged on political party lines (Wise et al., Citation2020), with Democrats more likely than Republicans to express concern about their health, wear masks, and avoid large crowds (Blue, Citation2020). Consistently, those who identified as Republican in Study 3 expressed significantly less pandemic threat compared to Democrats. These findings highlight the role of the political context in the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism.

Theoretical and practical implications

Our findings provide further evidence that authoritarianism is rooted in threat and group-related concerns (Duckitt, 1992; Kreindler, Citation2005). On a theoretical level, this supports motivational models of authoritarianism, which conceptualize it as an expression of the need for in-group cohesion (Duckitt, Citation1989). Social cohesion and collective group action are a public health necessity during times of pandemic (Jetten et al., Citation2020; Vaughan & Tinker, Citation2009). However, defining oneself as an in-group member should increase categorization of groups as sources of safety or threat (Jetten et al., Citation2020; Kreindler, Citation2005). Previous research has demonstrated that threat drives both in-group identification (Fritsche et al., 2010) and authoritarian responses (Jugert & Duckitt, Citation2009). Our results demonstrate that national identification was positively correlated with perceptions of threat from the pandemic. Identification was, in turn, positively correlated with authoritarianism and this association partially explains the threat-authoritarianism link. Those who identify with the in-group, are most likely to endorse authoritarian actions in times of threat.

Practically, this may mean an intolerance toward behaviors that do not conform with national mandates and those who are unable to meet imposed restrictions. Such tendencies could precipitate a rise in support of anti-immigration politics, even among those who typically espouse left-wing views. Indeed, a global pandemic has conflicting implications for intergroup tensions. At times of crisis, national identification and solidarity increase (Jay et al., Citation2019) and, as people begin to share a common perspective, this can foster adherence to public health behaviors (Maher et al., Citation2020). However, an increased emphasis on the mandated behavior of group members can also increase intergroup tension (Cohrs & Asbrock, Citation2009). For example, threats become more likely to be attributed to out-group sources with consequent negative consequences for intergroup intolerance, prejudice, and punishment (McCann, Citation2008). In multicultural societies, many of those that reside within national boundaries do not necessarily share prototypical national group membership (Foran et al., Citation2021). Therefore, any rise in national identification may drive anti-immigrant and anti-ethnic minority sentiment (Wenzel et al., 2008), most often associated with authoritarianism.

Our findings also highlight the key role of political context in these associations. As we anticipated, the effect of threat on authoritarianism was moderated by political orientation in the USA sample (Study 3). The link between threat and authoritarianism was not present among conservatives. An important aspect of the US context was the behavior of the President at the time (Donal Trump). This was a conservative US President who largely played down the threat of the virus and developed an increasingly antagonistic relationship with public health officials. We subsequently tested the presence of this interaction in the UK and Irish samples (see supplementary materials). We found that this moderation was also present in the UK sample, although it was not nearly as pronounced as the US effect. The UK also had a conservative government at the time who were slow to take the threat of the virus seriously, initially adopting for what some perceived as a “herd immunity strategy.” The fact that the interaction was not present in the Irish sample suggests that the national context plays an important role in the association between pandemic threat and authoritarianism (however see, Mirisola et al., Citation2014). Future research should explore how the framing of the pandemic by different political leaders can influence identification and levels of authoritarian endorsement.

Limitations and prospects for future research

The generalizability of our findings is constrained by the representativeness of our samples. Although all three sample were substantial, each relied on online recruitment. In addition, each of sample could be considered as white, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD). As such, we do not have an insight into how pandemic threat interacts with national identification in populations outside this subset. However, UK participants in Study 2 were recruited to represent the population on key demographics which adds to its strengths as a sample. In addition, the findings were highly consistent across each of these studies. Indeed, the purpose of using different countries for each study was to demonstrate that the indirect effect of pandemic threat on authoritarianism though national identification across contexts. Nevertheless, future research could expand on the present findings by recruiting non-WEIRD samples. This would have the additional benefit of exploring the impact collectivist versus individualistic cultures may have on pandemic threat.

As this is cross sectional data, causality cannot be inferred from our analysis. Instead, we present associational patterns to highlight the main variables at play. Of course, there is research to suggest that authoritarians are particularly sensitive to threats (e.g., Butler, 2013), and an alternative model of the data that would reverse the causal direction of the association between threat and authoritarianism. However, we do not see pandemic threat as something that would be enhanced by authoritarianism. Indeed, the threat of previous pandemics was not directly associated with authoritarianism (e.g., Stürmer et al., 2016). Similarly, our findings from Study 3 also suggest pandemic threats have a more complicated relationship with authoritarianism in comparison to other societal threats. Future studies could explore causal associations by manipulating pandemic threat or national identification in an experimental setting. Such research could also test the boundaries of this effect and aim to identify if more inclusive forms of identification, or higher levels of community trust, engender fewer authoritarian tendencies.

On a more general note, we want to stress that there are limits to what individual-level data can tell us about group level phenomenon (Mols, & ‘t Hart, 2018). In particular, our aggregated individual level analysis cannot fully account for the group process at work in linking pandemic threat to authoritarianism. Future research is need to explore both the influence of social context and group processes in more dept. A more methodologically constructivist approach would enable researchers to integrate aspects of the meso and macro-level context more effectively.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and its implemented countermeasures are having devastating social, economic and public health consequences. It is a broad form of social threat. We found that experiences of pandemic threat predict national identification and, in turn, increased authoritarianism. Encouraging collective adherence to pandemic restrictions in order to curtail virus spread, often requires appeals to national pride and identification. However, viruses are carried by “other” people, and this provides an opportunity for some to apportion blame, impose restrictions, and enforce strict punishment upon those who fail to comply. These are central features of authoritarianism. Our evidence suggests that the endorsement of authoritarian values in response to threat may partially be explained by national identification. Promoting collective adherence by appealing to in-groups that are too narrow or non-sufficiently inclusive, risks sowing seeds of discontent and eroding the public solidarity necessary to defeat global pandemics. However, “other” people are also the source of protection from the virus. The flip-side of our findings is that people seek collective identification in response to threat and calls for national unity that are sufficiently inclusive and considerate are more likely to be effective.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://osf.io/bs897/?view_only=None.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (112.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

Data availability statement

The data described in this article are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/bs897/?view_only=None.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paul J. Maher

Paul J Maher is a Social Psychologist and Lecturer at the University of Limerick. His research interests center on emotions, self-regulation, social influence and political polarization.

Jenny Roth

Jenny Roth is a Lecturer at the University of Limerick. Much of her research focusses on the antecedents and consequences of social identification. She is a Social Psychologist that often combines a social cognitive approach to intergroup relations.

Siobhán Griffin

Siobhán Griffin is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Limerick. Her research interests include social identity, emotion regulation, and health.

Aoife Marie Foran

Aoife-Marie Foran is a Social Psychology PhD student at the University of Limerick. Her research interests focus on the link between group processes and health among people living with stigmatised identities.

Sarah Jay

Sarah Jay is a Social Psychologist and Lecturer at the University of Limerick. Her research focuses on group processes and empowerment among marginalised communities.

Cillian McHugh

Cillian McHugh is an experimental psychologist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Limerick. His research focuses on the cognitive and social psychology of morality and moral judgement.

Megan Ryan

Megan Ryan is a Social Psychology PhD student in the University of Limerick. Her research interests include economic inequality, income, stress, and health

Daragh Bradshaw

Daragh Bradshaw is a lecturer in psychology at the University of Limerick. He is interested in research on group membership and identity change.

Michael Quayle

Michael Quayle is a social psychologist working on interdisciplinary approaches to understand social identity, and how active identity production impacts on psychological experiences and outcomes. Currently busy with an ERC-funded project developing a network theory of attitudes.

Orla T Muldoon

Orla Muldoon is Founding Professor of Psychology at University of Limerick. She is a social and political psychologist interested in how systems and structures determine everyday behaviour and health.

Notes

1. Because of a programming error, Societal Threat items were initially scored on a 5-point scale, we transformed responses to a 7-point scale (1 = 1, 2 = 2.5, 3 = 4, 4 = 5.5, 5 =7) in line with the health threat items.

2. The survey used included measured of national prototypically and solidarity. Since in some conceptualizations of the social identification construct these variables are considered distinct aspects of social identification (Leach et al., 2018), we incorporated these measures into additional analysis as a further test of our main hypothesis.

3. Furthermore, the indirect effect remained significant when we tested national prototypicality (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.06]) and solidarity (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.03]) as alternative measure of identification.

4. As in Study 1, the indirect effect remained significant when we tested national prototypicality (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.07]) and solidarity (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.07]) as alternative measures of identification.

5. National identification scores were also significantly higher for Republicans (M = 5.78, SD = 1.01) compared to Democrats (M = 5.29, SD = 1.29), t(332) = 3.74, p <.001, d = 0.41.

6. As in Studies 1 and 2, the indirect effect remained significant when we tested national prototyipicality (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.09]) and solidarity (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07]) as alternative measures of identification.

References

- Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. Harper.

- Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. Y. (2020). Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the Coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104254. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254

- Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Harvard University Press.

- Bartolucci, A., & Magni, M. Survivors' Solidarity and Attachment in the Immediate Aftermath of the Typhoon Haiyan (Philippines). PLoS Currents January 09. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.2fbd11bd4c97d74fd07882a6d50eabf2

- Bizumic, B., & Duckitt, J. (2018). Investigating Right Wing Authoritarianism With a Very Short Authoritarianism Scale. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6(1), 129–150. 10.5964/jspp.v6i1.835

- Blanchet, A., & Landry, N. (2021). Authoritarianism and Attitudes Toward Welfare Recipients Under Covid-19 Shock. Frontiers in Political Science, 3(66088), 35. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.660881

- Blue, Y. (2020, March 18). New coronavirus polling shows Americans are responding to the threat unevenly [Blog post]. https://medium.com/@YouGovBlue/new-coronavirus-polling-shows-americans-are-responding-to-the-threat-unevenly-641026301516

- Brug, J., Aro, A. R., Oenema, A., de Zwart, O., Richardus, J. H., & Bishop, G. D. (2004). SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(8), 1486–1489. 10.3201/eid1008.040283

- Cohrs, J. C., & Asbrock, F. (2009). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice against threatening and competitive ethnic groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(2), 270–289. 10.1002/ejsp.545

- Cohrs, J. C., Kielmann, S., Maes, J., & Moschner, B. (2005). Effects of right‐wing authoritarianism and threat from terrorism on restriction of civil liberties. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 263–276. doi:10.1111/j.1530-2415.2005.00071.x

- Cookson, C. (2020, March 11). WHO labels coronavirus a pandemic. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5946a17c-63bb-11ea-a6cd-df28cc3c6a68

- Doty, R. M., Peterson, B. E., & Winter, D. G. (1991). Threat and authoritarianism in the United States, 1978–1987. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 629–640. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.629

- Drury, J., Cocking, C., & Reicher, S. (2009). The Nature of Collective Resilience: Survivor Reactions to the 2005 London Bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66–95.

- Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology, 24(1), 199–222. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00322

- Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 41–113). Academic Press.

- Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., Du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(1), 75. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.75

- Duckitt, J. (1989). Authoritarianism and group identification: A new view of an old construct. Political Psychology, 10(1), 63–84. doi:10.2307/3791588

- Feldman, S., & Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18(4), 741–770. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00077

- Ferguson, N., Laydon, D., Nedjati Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M., … Dighe, A. (2020). Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand.

- Fiedler, K., Harris, C., & Schott, M. (2018). Unwarranted inferences from statistical mediation tests–An analysis of articles published in 2015. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 75, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.11.008

- Foran, A. M., Roth, J., Jay, J., Griffin, S. M., Maher, P. J., McHugh, C., Bradshaw, D., Ryan, M., Quayle, M., & Muldoon, O. T. (2021). Solidarity Matters: Prototypicality & Minority and Majority Adherence to National COVID-19 Health Advice. International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1), 25. http://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.549

- Fritsche, I., Jonas, E., Ablasser, C., Beyer, M., Kuban, J., Manger, A.-M., & Schultz, M. (2013). The power of we: Evidence for group-based control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.014

- Fritsche, I., Jonas, E., & Kessler, T. (2011). Collective reactions to threat: Implications for intergroup conflict and for solving societal crises. Social Issues and Policy Review, 5(1), 101–136. 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01027.x

- Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. Rinehart & Winston.

- Funke, F. (2005). The Dimensionality of Right-Wing Authoritarianism: Lessons from the Dilemma between Theory and Measurement. Political Psychology, 26(2), 195–218. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00415.x

- Golec de Zavala, A., Bierwiaczonek, K., Baran, T., Keenan, O., & Hase, A. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic, authoritarianism, and rejection of sexual dissenters in Poland. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(2), 250–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000446

- Gollwitzer, A., Martel, C., Brady, W. J., Knowles, E. D., & Van Bavel, J. (2020). Partisan Differences in Physical Distancing Predict Infections and Mortality During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 1186–1197. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00977-7

- Green, E. G., Krings, F., Staerklé, C., Bangerter, A., Clémence, A., Wagner-Egger, P., & Bornand, T. (2010). Keeping the vermin out: Perceived disease threat and ideological orientations as predictors of exclusionary immigration attitudes. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 20(4), 299–316. doi:10.1002/casp.1037

- Guinote, A., Brown, M., & Fiske, S. T. (2006). Minority status decreases sense of control and increases interpretive processing. Social Cognition, 24(2), 169–186. doi:10.1521/soco.2006.24.2.169

- Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When Morality Opposes Justice: Conservatives Have Moral Intuitions that Liberals may not Recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. doi:10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

- Hartman, T. K., Stocks, T. V., McKay, R., Gibson-Miller, J., Levita, L., Martinez, A. P., & Bentall, R. P. (2021). The authoritarian dynamic during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(7), 1274–1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620978023.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050

- Hogg, M. A. (2007). Uncertainty-identity theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 39, pp. 69–126). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)39002-8

- Jackson, L. E., & Gaertner, L. (2010). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their differential use by right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in support of war. Aggressive Behavior, 36(4), 238–50. doi:10.1002/ab.20344

- Jay, S., Batruch, A., Jetten, J., McGarty, C., & Muldoon, O. T. (2019). Economic inequality and the rise of far‐right populism: A social psychological analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 418–428. doi:10.1002/casp.2409

- Jetten, J., Reicher, S. D., Haslam, S. A., & Cruwys, T. (2020). Together apart: The psychology of COVID 19. Sage.

- Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339

- Jugert, P., & Duckitt, J. (2009). A motivational model of authoritarianism: Integrating personal and situational determinants. Political Psychology, 30(5), 693–719. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00722.x

- Karwowski, M., Kowal, M., Groyecka, A., Białek, M., Lebuda, I., Sorokowska, A., & Sorokowski, P. (2020). When in Danger, Turn Right: Does Covid-19 Threat Promote Social Conservatism and Right-Wing Presidential Candidates? Human Ethology, 35(1), 37–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.22330/he/35/037-048

- Kreindler, S. A. (2005). A Dual Group Processes Model of Individual Differences in Prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(2), 90–107. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_1

- López-Alves, F., & Johnson, D. E. (Eds.). (2018). Populist Nationalism in Europe and the Americas. Routledge.

- Maher, P. J., MacCarron, P., & Quayle, M. (2020). Mapping public health responses with attitude networks: The emergence of opinion‐based groups in the UK’s early COVID‐19 response phase. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(3) , 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.123963

- Mavor, K. I., Macleod, C. J., Boal, M. J., & Louis, W. R. (2009). Right-wing authoritarianism, fundamentalism and prejudice revisited: Removing suppression and statistical artefact. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5–6), 592–597. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.12.016

- McCann, S. J. H. (2008). Societal threat, authoritarianism, conservatism, and U.S. state death penalty sentencing (1977-2004). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 913–923. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.913

- Mirisola, A., Roccato, M., Russo, S., Spagna, G., & Vieno, A. (2014). Societal Threat to Safety, Compensatory Control, and Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 35(6), 795–812. doi:10.1111/pops.12048

- Mols, F., & T Hart, P. (2018). Political psychology. In V. Lowndes, M. Marsh, & G. Stoker (Eds.), Theory and methods in political science (pp. 142–157). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2018). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

- Osborne, D., Milojev, P., & Sibley, C. G. (2017). Authoritarianism and National Identity: Examining the Longitudinal Effects of SDO and RWA on Nationalism and Patriotism. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(8), 1086–1099. doi:10.1177/0146167217704196

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. doi:10.1111/bjso.12006

- Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

- Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Haslam, S. A. (2010). The social identity approach in social psychology. In M. S. Wetherell & C. T. Mohanty (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of identities (pp. 45–62). SAGE.

- Roth, J., Mazziotta, A., & Barth, M. (2019). The two-dimensions-five-components structure of in-group identification is invariant across various identification patterns in different social groups. Self and Identity, 18(6), 668–684. doi:10.1080/15298868.2018.1511465

- Sales, S. M. (1973). Threat as a factor in authoritarianism: An analysis of archival data. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 44. doi:10.1037/h0035588

- Schmid, K., & Muldoon, O. T. (2015). Perceived threat, social identification, and psychological well‐being: The effects of political conflict exposure. Political Psychology, 36(1), 75–92. doi:10.1111/pops.12073

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. doi:10.1177/1948550617715068

- Stürmer, S., Rohmann, A., Mazziotta, A., Siem, B., & Barbarino, M.-L. (2017). Fear of Infection or Justification of Social Exclusion? The Symbolic Exploitation of the Ebola Epidemic. Political Psychology, 38(3), 499–513. doi:10.1111/pops.12354

- Tybur, J. M., Inbar, Y., Aarøe, L., Barclay, P., Barlow, F. K., De Barra, M., and Žeželj, I. (2016). Parasite stress and pathogen avoidance relate to distinct dimensions of political ideology across 30 nations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(44), 12408–12413. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607398113

- Van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Crockett, M., & Willer, R. (2020). Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response). Nature human behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. doi:10.31234/osf.io/y38m9

- Van Hiel, A., Pandelaere, M., & Duriez, B. (2004). The impact of need for closure on conservative beliefs and racism: Differential mediation by authoritarian submission and authoritarian dominance. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(7), 824–837. doi:10.1177/0146167204264333

- van Leeuwen, F., & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceptions of social dangers, moral foundations, and political orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(3), 169–173. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.017

- Vaughan, E., & Tinker, T. (2009). Effective health risk communication about pandemic influenza for vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), 324–332. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537

- Wagemans, F. M. A., Brandt, M. J., & Zeelenberg, M. (2018). Disgust sensitivity is primarily associated with purity-based moral judgments. Emotion, 18(2), 277–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000359

- Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C., & Mobbs, D. (2020). Changes in risk perception and protective behavior during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Royal Society Open Science, 7(9), 200742. doi:10.31234/osf.io/dz428

- Yun, L., Vanderloo, L. M., Berry, T. R., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., O’Reilly, N., Rhodes, R. E., Spence, J. C., Tremblay, M. S., & Faulkner, G. (2019). Political orientation and public attributions for the causes and solutions of physical inactivity in Canada: Implications for policy support. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 153. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00153