»The finest silk rug I have seen was the one spread before the famous peacock throne in the audience hall of the Shah, inwoven with pearls.«Footnote 1 When the envoy of the USA S. G. W. Benjamin arrived in Iran in 1883, he did not tire of describing the objects, paintings, and furnishing elements in the palaces he visited, nor of commenting on their ceremonial use, for example, how the Shah »seats himself on the carpet of pearls before the peacock throne«.Footnote 2 Carpets were ubiquitous in the royal palaces of 19th-century Iran, where they did not only embellish rooms, but also structured them by clearly delineating spaces of power, and where they served to visualize and determine political and social hierarchies. At the court of Husayn ͑Alī Mirzā in Shiraz, the delegates of the British embassy had to sit »according to rank on nammeds [felts] laid close to the wall, over the splendid carpet of this room,«Footnote 3 and even at the court of the crown prince ͑Abbās Mirzā, where the rules of etiquette were less strict, George Fowler described the room as »richly carpeted, and nummeds were laid on each side, for the visitors to range themselves according to their rank.«Footnote 4

The space differentiating and honoring function of rugs is well known from the practice of rolling out a red carpet in front of a head of state or a distinguished guest.Footnote 5 Historically, this role of carpets marking »forbidden« or privileged territory reaches back to pre- and early Islamic times,Footnote 6 but it was also taken up by Western rulers, such as, for example, at the court of Louis XIV.Footnote 7 In Versailles, a complicated carpet protocol was followed and, as Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans described, »those of the royal family have no privileges above the other Dukes, excepting in their seats and the right of crossing over the carpet, which is allowed to none but them.«Footnote 8

Whereas to date, scholarship has mainly analyzed the political role of Oriental carpets covering the ground, by introducing pictorial rugs with large-scale human figures into the discussion, this study seeks to show that the political notion of carpets is not only restricted to their use and placement, but relates also to the design of the actual objects themselves. While this has already been observed regarding certain motifs like coats-of-arms on Oriental carpets,Footnote 9 the carpet as a medium for the representation of the human figure has been mostly ignored. In the 19th and early 20th century, the reception of paintings, lithographs, and specifically photographs led to a high number of experiments with portraits in the carpet medium, particularly in Iran and in the Soviet Union. Rather than only enjoying the privilege of stepping onto a carpet connoting power, some persons were actually represented in the central field of a rug. Numerous portrait carpets of rulers are preserved from both regions, a selection of which serves as the basis for this study.

Oriental carpets have long been connected with the portrait genre, albeit generally as a pictorial element within a painting. The tradition of studying Oriental carpets in European art, for example, in the portrait paintings by Lorenzo Lotto, Hans Holbein, or Anthony van Dyck, where rugs cover benches, tables and floors, is well established.Footnote 10 Since the middle ages, painters have been intrigued by Oriental rugs, when they sought to explore the boundaries of the use of perspective, color, and the representation of different materials in their artworks. This paper, however, questions a different process, namely, the specific challenges which rug weavers »faced« when representing portraits on carpets, and the multi-»faceted« and creative solutions they found. Just like pictures or any kind of material objects, carpets have specific qualities prior to their use as image carriers which determine their perception, and they relate to and interact with other media.Footnote 11 The aim of this study is hence threefold: to interrogate the artistic intermedial processes when translating portraits onto carpets, to shed new light on their multiple temporalities, and on the political dimensions of portrait rugs.

»Rugs with faces«: 19th- and early 20th-century Iran

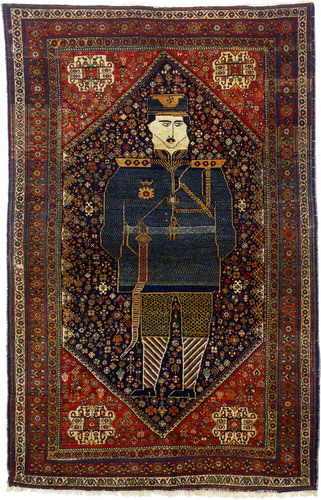

When thinking of Oriental carpets, motifs like geometrical and vegetal ornament, hunting scenes, paradisiacal gardens, or perhaps Portuguese ships arriving at the »shore« of a carpet's central medallion come to mind. Parviz Tanavoli's seminal analysis of large-scale portraits in the carpet medium from Iran, in contrast, has found few followers.Footnote 12 One of these so-called »rugs with faces« (qālīchaha-ya sūrati) is a portrait carpet of Rezā Shāh (217 × 143 cm), which was knotted in Iran in the Abadeh area (). Tanavoli identified the inspirational photograph (), taken when Rezā Khān was still an officer in the army (1921–1925) and dated it to these years.Footnote 13 When compared to the photograph, Rezā's portrait appears mirror-inverted on the carpet and seems to echo the photographic technique of reversing images.Footnote 14 However, numerous differences are notable. The officer's small black and white photograph is monumentalized in the central field of the rug and rendered in a kaleidoscopic range of colors. In contrast to the slender figure shown on the photograph, Rezā's body appears rather clumsy and highly stylized on the carpet. While his figure is separated from the dark ground in the central medallion by a light contour line, his pale face with angularly, but nonetheless finely woven features dominates the upper part of the rug. The design and surface of his military uniform in Western style is represented in greatest ornamental detail and hence reduces the contrast between figure and ground. Furthermore, the medal on his chest, his epaulettes indicating his rank, and the mark on his hat take on a floral appearance and thus recall the blossoms that surround him. The weaver paid particular attention to the different materials and chose diverse ways to evoke their visual effects. While the shiny surface of the officer's polished boots is indicated by large diagonal stripes of red, blue, and white wool, smaller, horizontal stripes suggest his metallic saber. The only surface, which is neither differentiated by the use of different colors nor assimilated to the carpet's ornamentation, is Rezā's skin. This is why – although the outline of his lower jaw and chin clearly takes up the border of the central medallion in its diagonal shape – his face and neck stand out and appear particularly »alien« to the carpet.

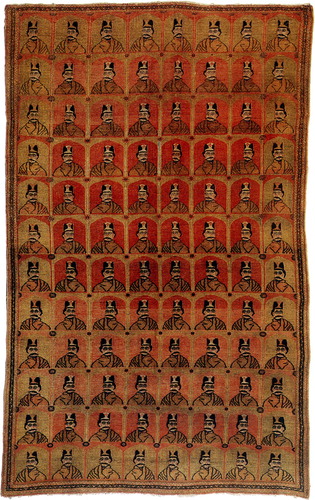

This solution differs categorically from the one employed by a weaver in Dorokhsh in Eastern Iran for a late 19th-century portrait carpet of Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh, which was also based on a photograph (), a 19th-century Iranian »Andy Warhol« in the carpet medium.Footnote 15 Here, instead of enlarging the ruler's portrait, we have the impression that the original photograph had been »transferred« onto the carpet in its exact format and size. The artisan tried to compensate for its smallness by using the traditional Iranian rug design of naqsh-e mokarrar (an all-over repeat pattern), thereby covering the entire rug with portraits of the Shāh.Footnote 16 On the area of 222 × 137 cm, the small portraits are positioned in niches or windows in a grid-like arrangement and repeated 96 times. The artifact hence negotiates both the qualities of the medium of photography with its duplicated images and of the carpet medium consisting of repetitious motifs in a potentially endless structure of warp, weft, and knotted pile. The portraits and the structure of the carpet are in fact entangled since by weaving and knotting the carpet both come into existence simultaneously rather than one being applied on the other – as a painting would have been on a pre-existing picture plain. Yet, as Tanavoli pointed out, monotony was carefully avoided by alternately turning the figure of the Shāh to his left or right and by changing the colors; the use of only three colors and the contrasts of light and shadow seem to allude to the restricted color range on a black and white photograph.Footnote 17 While the ruler is set against a light red background in the center, the border shows him on an ivory ground. This way, not only the Shāh's images received architectural framing devices with illusionistic arcades: by changing the border's color scheme, the weaver also created a frame within the carpet.

After photography had been invented in Europe, cameras arrived in Iran as gifts to the Shāh, where they were initially used by Europeans, but soon also by Iranians.Footnote 18 Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh himself showed a keen interest in the craft and spent much of his time taking photographs, above all portraits and self-portraits. As had been already common practice with regard to ruler portraits in a variety of media in European and Islamic court cultures for centuries,Footnote 19 also official photographs of the Shāh were reproduced and distributed among the government, where they were received as precious gifts and highly honored. According to Tanavoli, this custom was one of the main reasons for the popularity of portrait carpets of the ruling Shāh in the provinces. Since, from a technical point of view, duplicating photographs was still immensely difficult, especially in the rural parts of the country, »one of the easiest ways to make these images accessible was to reproduce them on rugs«,Footnote 20 – a process, which one is tempted to call Photographie im Zeitalter ihrer geknüpften Reproduzierbarkeit (»photography in the age of knotted reproduction«).

However, the story is not that simple. For not only carpet weavers, but also other craftsmen responded to photography. In the 19th century, the ancient technique of tilework was undergoing a revival, and ceramic revetments clad buildings such as the dado lining the vestibule of Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh's dīvānkhānah in the Gulistan Palace in Tehran. Underglaze tiles based on lithographs and photographs were painted in shaded and hatched black or sepia and positioned along the walls, such as we see in a tile depicting the ruler attending a piano recital ().Footnote 21 In contrast to the colorful portrait carpets, the monochrome color range of this tile was clearly intended as a reference to the original photograph. And unlike the rugs that incorporate the portraits into their medium of flatness the eight-pointed star tile opens up to an illusionistic view of a courtyard filled with people and dominated by the perspective dynamics of the strongly aligned lines. While the tile evokes a photograph permanently attached to, »merged« with the wall, portrait carpets were mobile, transportable items. In both cases, however, the fragility of the original photographs was avoided through the use of less ephemeral media – ceramic wall revetments and bulky carpets. Moreover, both – rugs covering walls and floors as well as tiles evoking the palace environment in their decoration – create an intriguing relationship between photography, its reception in other media, and architectural space.

Tilework had been known since the Achaemenid period as a medium for architectural decoration. In fact, equally important to the use and reception of modern media such as photography were references back to the glorious pre-Islamic Persian past, predominantly to the Sasanian kingdom (3rd–7th century CE). While such references have been often stressed for the choice of certain media like rock reliefs or of specific motifs like Persepolis or depictions of Sasanian rulers,Footnote 22 portrait carpets must also be emphasized in this regard. According to the Arab historian and geographer al-Mas'ūdī, the treasury of the Abbasid caliph al-Muntaṣir (861–862) included a legendary carpet:

The large carpet was edged with medallions enclosing pictures of men and an inscription in Persian – a language I read fluently. Now, to the right of the small prayer rug, I saw the portrait of a king with a crown on his head, shown in the posture of one who speaks. I read the inscription, which was as follows: This is the likeness of Shirawaih, murderer of his father, King Parwiz. He reigned six months. I then noticed a number of other portraits of kings and to the left of the small prayer rug, in the last place, was a figure with above it the following words: Portrait of Yazid ibn al-Walid ibn abd al-Malik, murderer of his cousin Walid ibn Yazid ibn Abd al-Malik. He reigned six months.Footnote 23

As noted, in 19th- and early 20th-century Iran, none of the photographs was directly »copied« onto the rug; on the contrary, when they served as models for portrait carpets consisting of warp, weft and knotted pile, their size, layout, colors, and design were considerably altered. Moreover, this translation process was not restricted to the relation between photography and carpets only, but numerous other media were involved. Lithographs and paintings functioned as sources for pictorial rugs as well,Footnote 27 and weavers drew additional inspiration from local wood-block printed or painted qalamkar curtains, where the figures – often in an all-over pattern comparable to the one on Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh's portrait carpet – were already rendered in a textile medium.Footnote 28 In fact, the ruler's likeness appeared in a variety of media, painted on items such as porcelain and pocket watches, and in paintings, rock reliefs, portrait busts, an equestrian statue, and even banknotes – different media that do not only all have their own specific qualities prior to their use as image carriers, but which also have their own history, temporalities, and semantic connotations.Footnote 29

19th- and early 20th-century Persian portrait carpets bear witness to this highly experimental and creative phase regarding the artistic interaction of various media and the portrait genre. Furthermore, notions of time were a particularly significant aspect in this period, characterized by a complex entanglement of visions of the future, present, and past, in which the »newest form of representation, i.e. photography«Footnote 30 played a crucial role. Yet, as we have seen, so too did the ancient Iranian past.

»As if it were alive«: portrait carpets in the Soviet Union

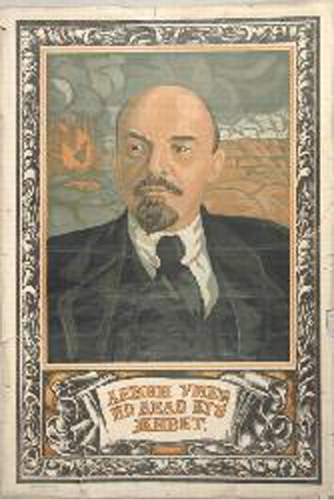

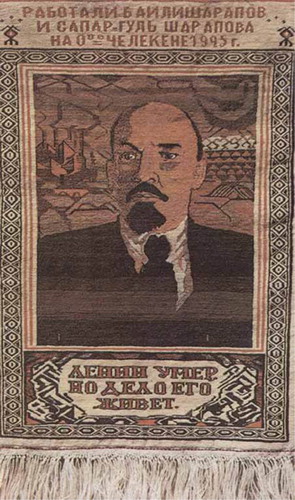

Let us now shift attention to another region. In 1925, the first Soviet portrait carpet was woven in Cheleken, now Chasar, on the shore of the Caspian Sea in Turkmenistan in Central Asia, in the newly founded Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (TSSR) ().Footnote 31 This rug, measuring 100 × 70 cm, represented Lenin ().Footnote 32 The model for the Turkmen weavers was clearly a Russian lithograph of Lenin's portrait issued after his death in 1924 (), which itself was based on a photograph taken in 1920 (). While the lithograph shows Lenin in front of a landscape, which seems to be burning because of the factory smokestacks, and set in a frame decorated with spinning baroque rollwerk ornament, both elements are barely recognizable in the carpet. The frame was even reinterpreted and abstracted into traditional border decoration known from rugs woven in this region. The lithograph's Russian inscription, however, is clearly legible on the carpet: Lenin umer, no delo ego zhivet (»Lenin died, but his cause lives on«). It corresponds with the motif of the »burning landscape«, as if alluding to a phoenix arisen from the ashes.

After his death, Lenin's images gained an icon-like status,Footnote 33 and even literally replaced icons in the so-called »Lenin corners«, a term derived from krasnyj ugolok, the icon corner in Russian houses.Footnote 34 Lenin also became a principal figure in Soviet Central Asia, where folktales described him as the immortal son of the moon and the stars,Footnote 35 and where, in 1927, the newspaper Kyzyl Uzbekistan disputed if Lenin could be called a prophet (agreeing, finally, that he could) and what his position was in comparison to Jesus and Muhammad.Footnote 36 In fact, by changing the pattern to figurative portraits and by taking the carpets from the floor and putting them on the wall, they now resembled political icons, »carpet pictures« framed by traditional border ornaments, a notion, which is enhanced by the carpet's traditional role in both Christian and Muslim contexts of indicating a sacred surface.Footnote 37

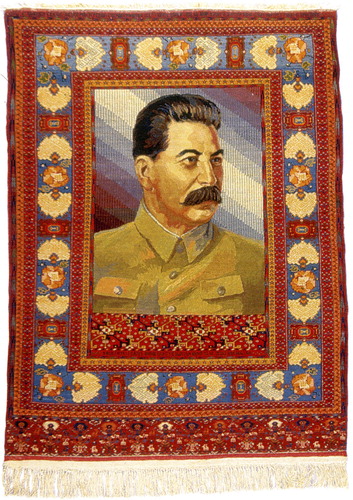

However, one quality related to sacred images (in a textile medium) was not adopted: According to a signature claiming authorship at the upper end of the Lenin rug, Baili Sharapov and Sapargul' Sharapova had woven it in Cheleken in 1925. The weavers' signature clearly specifies the portrait carpet as a manufactum.Footnote 38 In the 1930s, when Stalin replaced Lenin as the most prominent figure in the Soviet Union, his portrait became the favorite subject for carpets, as we see, for example, on a pictorial rug in the Wolfsonian Collection in Miami dated 1936 ().Footnote 39 This artifact also bears the signatures of its two Turkmen weavers, Durli Gusel' Anna and Dursun Anna Klytsh, a fact which is particularly remarkable since a written account is preserved, in which the former describes the weaving of a Stalin carpet:

Everyday I bend over the frame. Already about a third of the rug is ready. My elderly hands have woven many rugs over the last thirty years, but I have never done anything like this. It shines with different colors – azure, tender-white, purple. This is the frame. And above it already transpires the green service jacket, the oval of the face…–Stalin. Together with my daughter Dursun Anna Klytsh, my always-radiant-with-laughter daughter, I am working on the portrait of the biggest, wisest man – Stalin. We used his portraits and busts to study every detail of his face, so that we could copy it precisely onto the rug, and so that the rug portrait looks as if it were alive.Footnote 40

As proclaimed in publications of the time, these portrait carpets were »new, national in their form and socialist in their content«.Footnote 45 Turkmen weavers such as Durli Gusel' Anna and Dursun Anna Klytsh were celebrated for their national craftsmanship apparent in the traditional ornaments as well as for mastering the new challenges related to figurative representation. Traditional ornamentation on these rugs was not only tolerated, on the contrary, it was explicitly welcome,Footnote 46 and successful and creative combinations of figure and ornament were particularly praised.Footnote 47 Such portrait carpets were frequently produced as gifts to be sent to the capital. For example, at the exhibition of Stalin's birthday gifts an enormously large pictorial carpet »from the toiling masses of Azerbaijan« was on display. Measuring 70 m2 and weighing 167 kg, the gigantic artifact, which consisted of yarn of »250 colors and 600 shades«, featured »about 70 pictorial narratives and 300 ornamental motifs«.Footnote 48 This carpet with a portrait of Stalin at center more than 3.5 m high was celebrated in the 1949 Russian newspaper Ogonek as »the most outstanding achievement of the people's applied art, worthy of the greatness of Stalin's era, and with no equivalent in the history of rug weaving in the whole Near East«.Footnote 49

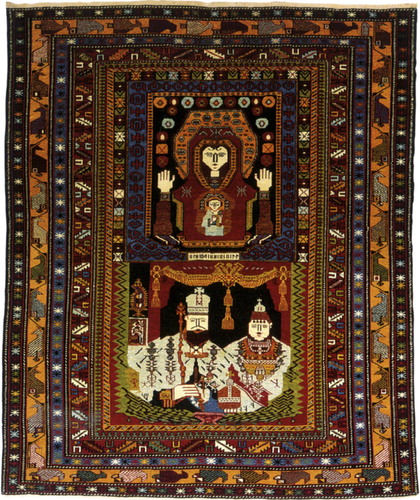

Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov and Olga Sosnina have argued that Turkmen portrait carpets »evoked, in the socialist global chronotope, the legacy of the Russian Empire receiving tributary gifts from its Oriental subjects«.Footnote 50 This interpretation can be supported through studying earlier carpet gifts. In fact, neither the phenomenon of portrait carpets in general, nor of those depicting Russian rulers was new. After their coronation in 1883, Tsar Aleksandr III and his wife Maria Feodorovna received a portrait rug as a gift from weavers of Azerbaijan in the Caucasus (), a region which had been part of the Russian Empire since the beginning of the 1800s.Footnote 51 Framed by traditional Marasali border design, the royal couple – based on a colored lithograph – appears in coronation regalia in the lower part of the central field, whereas, above them, one of the most sacred icons of the Russian Orthodox Church, the Yaroslavskaya Oranta, is represented. The fields are separated through an inscription in pseudo-Cyrillic script. While the weavers' witty and creative interplay of Christian symbols such as the crosses, Mary's stars or the form of the halo with traditional motifs in the upper field are notable, the Virgin, with her raised arms, resembles an outstretched Muslim praying on a rug.

Bilderflugzeuge and geopoetics: the flying (portrait) carpet

Durli Gusel' Anna and Dursun Anna Klytsh's Stalin carpet reveals a highly complex interaction between figurative and non-figurative elements as well (). At first sight, the painting-like composition of the carpet is remarkable: Stalin is represented in the central field surrounded by a border with a Western pattern resembling a picture frame. His face, hair, and green jacket are modeled by a careful play of light and shadows which emphasizes the uneven surface of his worn uniform and the three-dimensionality of his body. He seems to stand behind a balustrade covered with a rug featuring intricate traditional ornament. His representation thus recalls a portrait type which was well known in Europe and – since the 15th-century portrait of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II attributed to Gentile Bellini () – had also been employed to depict Islamic rulers:Footnote 52 The window or baldachin with a balustrade underlines the notion of depth in the composition; it keeps the »sitter» at a respectful distance, while the richly decorated carpet or textile hanging functions as a mark of distinction.

The different temporal layers in the carpet are conspicuous. On the one hand, newly introduced motifs such as Stalin's portrait and the border decoration dominate the composition. On the other hand, the traditional Turkmen ornamentation refers to a centuries-long history of meanings of its own. Third and last, the diagonal multi-colored stripes in the background are reminiscent of early 20th-century experiments with abstract painting. The gradation of the colors reaching from the margins to the center from red, violet, and various shades of blue to white further accentuates Stalin's eyes and the direction of his gaze: the right part of his forehead and his right eye are the most illuminated zones of his face. This postulated clarity of vision, supported by the dynamics achieved through the diagonal lines also corresponds with a trope omnipresent in Stalin's personality cult: Stalin as a representation of the sun or light itself and rays of light emanating from his figure.Footnote 53

However, Stalin is not represented in the medium of painting, but on a rug. While the compartment with traditional Turkmen ornamentation in the inner field – though woven and consisting of colored wool – recalls the representation of an Oriental carpet in portrait painting, this effect is counterbalanced by the lower band with Turkmen ornaments reaching from edge to edge. Together with the long white fringes, this horizontal component undermines the illusion of a picture. The over-all composition of the artifact in fact creates the visual effect of oscillation between picture and rug. In this regard, Durli Gusel' Anna Klytsh's cited statement becomes clearer: It is not Stalin or his portrait that should look »as if it were alive«, but the rug portrait (kovrovyi portret). What at first glance might have only reminded one of Western concepts of portraiture and the look through Alberti's window, is in fact also deeply connected to the medium of the carpet.

In his poem »The Wonderful Carpet« (Chudeznyj Kover, 1949), the poet Platon Voronko advanced this notion even further.Footnote 54 Deep in the Carpathian Mountains, Gutsulka is weaving a carpet featuring Stalin's likeness, while her daughters cannot take their eyes off of him. Both the features of Stalin's face and the rug's vivid colors trigger the girls' imagination; they get the impression of flying on this carpet across rivers, meadows, even flying over Moscow's Red Square. Once the weaving is finished, the Stalin carpet actually takes off and carries both girls around the Soviet Union.

In his famous speech at the Soviet Writers' Congress in 1934, Samuil Marshak had cited the »flying carpet« (kover samolet) as the perfect choice of material for a »Soviet fairy tale« (sovetskaia skazka):

The good thing about the tale of the flying carpet is not that a person can fly through the air on it. That would just make it some kind of Wunderbuch [book of strange events] and no more. The point is that a person who flies on a carpet has good reasons to do so. Without a flying carpet you can't get to the twenty-seventh kingdom on time, and that's what he badly needs to do. The carpet, though, lets him get to a place where no human foot has ever trod, it lets him overtake time itself.Footnote 55

It is intriguing to consider the girls' flight across the Soviet Union on a Stalin carpet in the context of – what has been called – »the spatial poetics« of Stalin's personality cult and »the landscape of Stalinism«.Footnote 57 After a personal meeting with the party leader in 1933, the artist Evgeny Katsman wrote:

Stalin has enchanted us all. What a colossal man! To me he seems as huge and beautiful as nature. I was on the top of Mount Tupik [sic!] in Dagestan during sunset. The mountains radiated like bright gems, I couldn't take my eyes off this, and wanted to remember everything for the rest of my life. Stalin is just like that: I looked at him, wanted to look at him forever and couldn't. I wanted to remember Stalin and couldn't. He very much resembles nature – the oceans, the mountains, the forests, the clouds. You wonder and are amazed and fascinated, but you know that this is nature. But Stalin is the peak of nature – Stalin is the oceans, mountains, forests, clouds, coupled with a powerful mind for the leadership of humanity.Footnote 58

In Voronko's poem, Gutsulka's daughters thus experience Stalin in multiple ways – through the medium of his portrait on the carpet, which protects them and, made of wool, gives them warmth up in the air, as well as through their flight across the Soviet Union and all the elements of nature therein bearing his name. The pliable and easily transportable carpet, once woven and used by nomadic tribes, recalling the tales of One Thousand and One Nights, has not only received a »face«, but an agency of its own. Rather than being only a material image carrier (Bildträger), a Warburgian Bilderfahrzeug or in this case Bilderflugzeug, it is now itself capable of carrying people, and rug, space and mobility are entangled in a wider sense.Footnote 61

Bringing the threads together

The 19th and early 20th century was the heyday of carpet collecting.Footnote 62 Oriental rugs that made their way to the West were used to cover floors, to upholster Russian, European, and Northern American furniture, or they were hung up on walls as precious collectors' items.Footnote 63 However, when Europe and the USA »rediscovered» the Oriental carpet in exhibitions, the interior, painting, literature, and also scholarship, the rugs they focused on were those featuring traditional designs. The »myth of the Oriental carpet« left no room for carpets with large-scale representations of human figures, let alone with portraits.

This study sought to draw attention to the highly active and creative production of portrait carpets in Iran and in the Central Asian periphery of the Soviet Union in the 19th and early 20th century. Weavers responded to portraits rendered in different media, among these photography, and experimented with different approaches when representing them on rugs. The representation of portraits and photographs on various kinds of objects had been common in Europe,Footnote 64 however, rendering portraits in the carpet medium was a particularly polyvalent process.

On the other hand, Iranian and Soviet portrait carpets can be interpreted in relation to Western tapestries. Tapestries featuring ruler portraits had been highly expensive commissions and had played a distinguished role at the various European courts for centuries, also in Imperial Russia; the political significance of ruler portraits in the textile medium was hence well established.Footnote 65 Just as Western tapestries relied on preliminary drawings, paintings, and cartoons, Iranian and Central Asian artisans took their inspiration from various media, several of them – such as photography – newly introduced from the West.

On the other hand, these transfer processes should not be understood as a mere Westernization, nor as a modernization of carpet designs. First, the close cooperation of rug weavers and miniature painters in 16th- and 17th-century Iran is well known, intermedial processes were hence not new regarding the creation of carpets.Footnote 66 Furthermore, the analysis of 19th- and early 20th-century Iranian portrait rugs has shown the various temporal layers of these artifacts comprising both references to the newly introduced medium of photography as well as to Iran's antiquity, especially the Sasanian past. Also, the introduction of large-scale portraits did not supplant traditional carpet ornaments, and weavers achieved complex results when experimenting with figure and ornamentation.

The latter became a crucial aspect in the scholarly and political discourse with regard to portrait carpets in the Soviet Union, as publications of that time revealed. Here, portrait carpets could not only replace aristocratic tapestries, they were also a means to involve and engage artists and craftsmen at the periphery of the Empire in the creation of a multiethnic and multicultural Soviet visual and material culture. And although Soviet carpet manufacturers were soon collectivized and the tribal context was given up,Footnote 67 certain associations connected with the medium itself, such as the notion of the flying carpet, remained and underwent new interpretations.

In the last decade, more and more pictorial carpets received worldwide attention: Afghan war rugs showing repetitious depictions of airplanes, tanks, machine guns, and artillery shells within traditional geometric and floral ornaments, representing human figures, or air planes crashing into the Twin Towers;Footnote 68 as well as pictorial carpets created by contemporary artists like Goshka Macuga who negotiates both the political dimension of rugs and the relationship between knotted pile carpets and the pixels of digital photography, or artworks comprising Soviet portrait carpets like those by Michel Aubry. This new attention to carpets which deviate from the traditional »picture« of the Oriental carpet, gives rise to the hope, that also Iranian, Caucasian, and Soviet portrait carpets will receive more scholarly consideration.

From May 19 to August 31, 2012, Soviet portrait carpets were on display at the State Museum of Political History of Russia in St. Petersburg in the exhibition Pod Kovrom (»Under the Carpet«).Footnote 69 The curators' choice to exhibit the rugs flying up in the air does not only recall different metaphorical, political, and literary narratives related to the medium of the carpet. It also emphasizes the fact that our encounter with rugs is a spatial one and that it is always connected with the body. Carpets determine the body's movement through space. However, once they themselves represent bodies, notably a royal body or the body of a ruler, the interaction between the carpet medium, the represented body, and the body of the beholder is entwined in highly complex ways and always at risk of becoming unstable.Footnote 70 Roles may shift, the beholder may turn into a »betrodder«, – when the portrait rug returns to the floor, when it is used as a bathroom mat like a portrait carpet depicting Muammar al-Gaddafi in a photograph taken by C. J. Chivers of a prison camp directed by rebels in Libya and published in the New York Times in May 2011 ().

Summary

When thinking of Oriental carpets, motifs like geometrical and vegetal ornament, hunting scenes, and paradisiacal gardens usually come to mind. This paper, instead, draws attention to pictorial rugs featuring large-scale portraits that were made in Iran and the Soviet Union in the 19th and 20th century. By shedding light on this hitherto rather neglected group of artifacts and by interrogating the artistic practices and challenges of translating portraits onto carpets, this study will contribute to discussions of artistic intermedial processes, multiple temporalities of artifacts, and the relationship of figure and ornament. Further, it will enhance our understanding of the political dimensions of portrait rugs.

Acknowledgements

I would like to warmly thank Johanna Rosenqvist, Martin Sundberg, Gerhard Wolf and my anonymous reviewer for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions. My thanks also go to Jessica Richardson and Sean Nelson for their thorough and critical reading of this text.

Notes

1. S. G. W. Benjamin, Persia and the Persians, London, 1887, p. 426.

2. Benjamin, 1887, p. 199. For the role of carpets as furnishing elements in 18th- and 19th-century Iran see Hadi Maktabi, »Under the Peacock Throne: Carpets, Felts, and Silks in Persian Painting, 1736–1834«, Muqarnas, No 26, 2009, pp. 317–347.

3. Sir William Ouseley, Travels in Various Countries of the East. More Particularly Persia, 3 vols., London, 1823, vol. 2, p. 12.

4. George Fowler, Three Years in Persia: With Travelling Adventures in Koordistan, London, 1841, p. 317. The Persian word for felt is spelled variously as nummed, nammed or nemmed by different authors.

5. Costanza Caraffa and Avinoam Shalem, »Hitler's Carpet: A Tale of One City«, Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, No 55, 2013, pp. 119–143.

6. Caraffa and Shalem, 2013, pp. 126–132; Avinoam Shalem, »Forbidden Territory. Early Islamic Audience-Hall Carpets«, Halı, No 99, 1998, pp. 70–77.

7. Wolfgang Brassat, »Monumentaler Rapport des Zeremoniells. Charles Le Brun ›tenture de l'Histoire du Roy«, in Zeremoniell als höfische Ästhetik in Spätmittelalter und Früher Neuzeit, ed. by Jörg Jochen Berns and Thomas Rahn, Tübingen, 1995, p. 364; Alberto Boralevi, »The Carpets of ›Le Roi Soleil«, Halı, No 6.1, 1983, pp. 38–39; A. Varron, »Der Teppich als Kennzeichen der Macht«, Ciba-Rundschau II, No 21, 1938, pp. 738–740. See also Edith Appleton Standen, »A King's Carpet«, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, No 13.9, 1955, pp. 257–265.

8. Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans, Secret Memoirs of the Court of Louis XIV and of the Regency Extracted from the German Correspondence of the Duchess of Orleans, Mother of the Regent, London, 1824, p. 418.

9. Kurt Erdmann, Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1970, pp. 207–209.

10. Wilhelm von Bode, Vorderasiatische Knüpfteppiche aus älterer Zeit. Mit Beiträgen von Ernst Kühnel, Leipzig, 1914; Kurt Erdmann, Europa und der Orientteppich, Berlin and Mainz, 1962; The Eastern Carpet in the Western World: From the 15th to the 17th Century, exhibition catalogue, ed. by Donald King and David Sylvester, London, 1983; Rosamond Mack, »Lotto as a Carpet Connoisseur«, Lorenzo Lotto. Rediscovered Master of the Renaissance, exhibition catalogue, ed. by David Alan Brown, Peter Humfrey, and Mauro Lucco, Washington, 1997, pp. 59–68; Mack, Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, Berkeley, 2002, pp. 73–93; Maria Ruvoldt, »Sacred to Secular, East to West: The Renaissance Study and Strategies of Display«, Renaissance Studies, No 20.5, 2006, pp. 640–657; Marco Spallanzani, Oriental Rugs in Renaissance Florence, Florence, 2007.

11. For in-depth discussions of the terms image carrier, media, and intermediality see Hans Belting, An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body, Princeton, 2011; Belting, »Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconology«, Critical Inquiry, No 31.2, 2005, pp. 302–319; Gottfried Boehm, »Vom Medium zum Bild«, in Bild – Medium – Kunst, ed. by Yvonne Spillmann and Gundolf Winter, Munich, 1999, pp. 165–178; James Elkings, The Domain of Images, Ithaca, 1999; William J. T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation, Chicago, 1994.

12. Parviz Tanavoli, Kings, Heroes and Lovers. Pictorial Rugs from the Tribes and Villages of Iran, London, 1994; Tanavoli, »A Celebration of the Human Figure«, Halı, No 80, 1995, pp. 88–96. A compelling in-depth study of an early 20th-century Persian portrait carpet has been recently presented by Charles Kurzman, »Weaving Iran into the Tree of Nations«, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, No 37, 2005, pp. 137–166. Notable in this respect are also discussions of Jewish figurative carpets, cf. Anton Felton, Jewish Carpets: A History and Guide, Woodbridge, 1997; Felton, »Jewish Persian Carpets« Esther's Children: A Portrait of Iranian Jews, ed. by Houman Sarshar, Philadelphia, 2002, pp. 295–309.

13. Cf. Tanavoli, 1994 (Footnotenote 12), pp. 174–175 and Tanavoli, »Royal Exposure« Halı, No 80, 1995, pp. 97–101, here p. 100. See also Reza Sheikh and Farid Fadaizadeh, »The Man who Would be King: The Rise of Rezā Khān (1921–25)«, History of Photography, No 37.1, 2013, pp. 99–116.

14. On the medium of photography see, for example, Ordnungen der Sichtbarkeit: Fotografie in Wissenschaft, Kunst und Technologie, ed. by Peter Geimer, Frankfurt am Main, 2002; Geimer, Theorien der Fotografie zur Einführung, Hamburg, 2010; L'évidence photographique: La conception positiviste de la photographie en question, ed. by Herbert Molderings and Gregor Wedekind, Paris, 2009; Elizabeth Edwards, Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images, London, 2004; Lynda Nead, The Haunted Gallery: Painting, Photography, Film, c. 1900, New Haven, 2007.

15. Cf. Tanavoli, 1994 (Footnotenote 12), pp. 158–159, for the photograph see Tanavoli, 1994, Fig. 26.

16. Cf. Tanavoli, 1995 (Footnotenote 13), p. 100.

17. Cf. Tanavoli, 1994 (Footnotenote 12), p. 158.

18. For the role of photography in Qajar Iran see The First Hundred Years of Iranian Photography, guest ed. by Reza Sheikh and Carmen Pérez González, History of Photography, No 37.1, 2013 with further literature, particularly Layla S. Diba, »Qajar Photography and its Relationship to Iranian Art: A Reassessment«, History of Photography, No 37.1, 2013, pp. 85–98; Ali Behdad, »The Power-Ful Art of Qajar Photography: Orientalism and (Self-)Orientalizing in Nineteenth-Century Iran«, Iranian Studies, No 34.1–4, 2001, pp. 141–151; Sevruguin and the Persian Image: Photography of Iran, 1870–1930, ed. by Frederick N. Bohrer, Washington, Seattle, 1999, pp. 79–98. Elahe Helbig is preparing a PhD thesis on early Iranian photography.

19. For European contexts cf., e.g. Louis Marin, Le portrait du roi, Paris, 1987; Sergio Bertelli, The King's Body: Sacred Rituals of Power in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, University Park, PA, 2001; Christiane Hille, Visions of the Courtly Body: The Patronage of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham, and the Triumph of Painting at the Stuart Court, Berlin, 2012; Marcia Pointon, »›Surrounded with Brilliants‹: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England«, The Art Bulletin, No 83, 2001, pp. 48–71; The Beautiful and the Damned. The Creation of Identity in Nineteenth Century Photography, exhibition catalogue, ed. by Peter Hamilton and Roger Hargreave, London, 2001. For ruler portraits in Safavid Iran see Kishwar Rizvi, »The Suggestive Portrait of Shah ͑Abbas: Prayer and Likeness in a Safavid Shahnama«, The Art Bulletin, No 94.2, 2012, pp. 226–250; Priscilla Soucek, »The Theory and Practice of Portraiture in the Persian Tradition«, Muqarnas, No. 17, 2000, pp. 97–108; Ernst J. Grube and Eleonor Sims, »The Representations of Shah ͑Abbas I«, in L'arco di fango che rubò la luce alle stelle: Studi in onore di Eugenio Galdieri per il suo settantesimo compleanno, ed. by Michele Bernardini, Lugano, 1995, pp. 177–208. At the Safavid court, rulers were also portrayed in the carpet medium, cf. Károly Gombos, »The Esterhazy appliqu« Carpet in Budapest«, in Halı, 3.3, 1981, pp. 217–219.

20. Tanavoli, 1995 (Footnotenote 13), p. 100.

21. Cf. Jennifer M. Scarce, »The Architecture and Decoration of the Gulistan Palace: The Aims and Achievements of Fath ͑Ali Shah (1797–1834) and Nasir al-Din Shah (1848–1896)«, Iranian Studies, No 34.1–4, 2001, pp. 103–116; Scarce, »Ancestral Themes in the Art of Qajar Iran, 1785–1925«, in Islamic Art in the 19th Century. Tradition, Innovation, and Eclecticism, ed. by Doris Behrens-Abouseif and Stephen Vernoit, Leiden and Boston, 2006, pp. 231–256, here 242–246; Scarce, Domestic Culture in the Middle East, Edinburgh, 1996, pp. 54–55.

22. Cf., e.g. J. P. Luft, »The Qajar Rock Reliefs«, Iranian Studies, No 34.1/4, 2001, pp. 31–49; Scarce 2006 (Footnotenote 21).

23. Cf. Meadows of Gold, trans. and ed. by Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone, London and New York, 1989, pp. 268–269.

24. Igor Kopytoff, »The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process«, in The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. by Arjun Appadurai, Cambridge, 1986, pp. 64–91; Avinoam Shalem, »Objects as Carriers of Real or Contrived Memories in a Cross-Cultural Context. The Case of Medieval Diplomatic Presents«, in Migrating Images. Producing… Reading… Transporting… Translating…, ed. by Petra Stegmann and Peter C. Seel, Berlin, 2004, pp. 36–52.

25. As suggested by Arthur U. Pope, A Survey of Persian Art, London and New York, 1939, vol. 6, p. 2277; see also Shalem, 1998 (Footnotenote 6), pp. 74–75; Caraffa and Shalem, 2013 (Footnotenote 5), pp. 129–130.

26. Tanavoli, 1994 (Footnotenote 12), pp. 19–24.

27. Annette Ittig, »Paintings in Carpets. Qajar Roccoco«, Halı, No 27, 1985, p. 35; Jennifer M. Scarce, »The Role of Carpets within the 19th Century Persian Household«, in Halı, No 6.4, 1984, pp. 394–400: 398.

28. Tanavoli, 1994 (Footnotenote 12), p. 10 and Tanavoli, 1994, Fig. 3; Tanavoli, 1995 (Footnotenote 13), p. 101.

29. The artistic reception of photographic images, also photographic portraits in other media had been already common in Europe cf. Jean-Michel Braive, »La photographie dans le mouvement artistique actuel«, Connaissance des arts, No 165, 1965, pp. 88–97; Heinz K. Henisch and Bridget A. Henisch, The Painted Photograph, 1839–1914: Origins, Techniques, Aspirations, University Park, 1996. For ruler images in Iran in different media, some of them referring to European models see Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch 1785–1925, ed. by Layla S. Diba and Maryam Ekhtiar, New York, 1999; Luft, 2001 (Footnotenote 21); Klaus Kreiser, »The Equestrian Statue of the Qajar Ruler Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh in Teheran (1888)«, in Iran und iranisch geprägte Kulturen. Studien zum 65. Geburtstag von Bert G. Fragner, ed. by Markus Ritter, Ralph Kauz, and Birgitt Hoffmann, Wiesbaden, 2008, pp. 389–398, for the banknotes see Kreiser, 2008, p. 392.

30. Behdad, 2001 (Footnotenote 18), p. 141.

31. There is no elaborate study on Soviet portrait carpets, cf. Adrienne Edgar, »Portrait of Lenin. Carpets and National Culture in Soviet Turkmenistan«, in Picturing Russia. Explorations in Visual Culture, ed. by Valerie A. Kivelson and Joan Neuberger, New Haven, 2008, pp. 181–184; Aygul Ashirova, Stalinismus und Stalin-Kult in Zentralasien: Turkmenistan 1924–1953, Stuttgart, 2009, pp. 60–61, 281–283.

32. Edgar, 2008, p. 60, 281; Galina I. Saurova, Iskusstvo Turkmenskoj SSR. The Art of Soviet Turkmenia, Leningrad, 1972, Fig. 10; Istorija kul'tury sovetskogo Turkmenistana (1917–1970) [Cultural History of Soviet Turkmenistan], ed. by A. Karryev, Ashkhabad, 1975, p. 74; Kovry i kovrovye izdelija Turkmenistana [Carpets and Carpet Products of Turkmenistan], ed. by N. Chodzhamuchamedov and N. Dovodov, Ashkhabad, 1983, p. 73.

33. Nina Tumarkin, Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia, Cambridge and London, 1997; Tumarkin, »Religion, Bolshevism, and the Origins of the Lenin Cult«, The Russian Review, No 40.1, 1981, pp. 35–46; Berthold Hinz, »›Iljitsch ist tot, aber Lenin lebt‹. Parabel und Parameter«, in Radical Art History. Internationale Anthologie. Subject: O. K. Werckmeister, ed. by Wolfgang Kersten, Zurich, 1997, pp. 203–211.

34. See also Kliment Red'ko's painting Vosstanie (Resurrection), 1925, referring to the icon type Spas v silach (Christ the Redeemer), and Evgenija Petrova, »Fonti religiose nell'arte del Realismo socialista«, in Realismi socialisti. Grande pittura sovietica 1920–1970, exhibition catalogue [Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni], ed. by Matthew Cullerne Brown and Faina M. Balachovskaja, Milan, 2011, pp. 161–165; Larisa A. Andreeva, Religija i vlast' v Rossii. Religioznye i kvasireligioznye doktriny kak sposob legitimizacii politicheskoy vlasti v Rossii [Religion and Power in Russia. Religious and Pseudo-Religious Doctrines as Method to Legitimate Political Power in Russia], Moscow, 2001.

35. Cf. Otto Unger, Lenin-Märchen: Volksmärchen aus der Sowjetunion, Berlin, 1929, pp. 32–34; A. V. Piaskovskii, Lenin v russkoi narodnoi skazke i vostochnoi legende [Lenin in the Russian Folktale and Oriental Legend], Leningrad, 1930; Alexander A. Panchenko, »The Cult of Lenin and ›Soviet Folklore«, Folklorica, No. 10.1, 2005, pp. 18–38; see also John MacKay, »Allegory and Accommodation: Vertov's Three Songs of Lenin (1934) as a Stalinist Film«, Film History, No 18.4, 2006, pp. 376–391, esp. p. 383.

36. Cf. Ashirova, 2009 (Footnotenote 31), p. 59. For the time under Russian dominion prior to the Soviet Union see Robert D. Crews, For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia, Cambridge, MA, 2006.

37. Patimat R. Gamzatova, »The Oriental Carpet in the Making of Sacred Spaces«, in Ierotopija: Issledovanie sakraln'nych prostranstv, ed. by Aleksej Lidov, Moscow, 2004, pp. 177–181.

38. Gerhard Wolf, Schleier und Spiegel: Traditionen des Christusbildes und die Bildkonzepte der Renaissance, Munich, 2002.

39. John E. Bowlt, »Stalin as Isis and Ra: Socialist Realism and the Art of Design«, The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, No 24, 2002, p. 35–63: 43 and Fig. 7.

40. V. Chepelev, »O novoi tematike v narodnom tvorchestve [On the New Theme in National Heritage]«, Iskusstvo, No 6, 1937, pp. 121–128, here 124–125. The English translation is cited after Cf. Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov and Olga Sosnina, »The Faculty of Useless Things: Gifts to Soviet Leaders«, in Personality Cults in Stalinism, ed. by Klaus Heller and Jan Plamper, Göttingen, 2004, pp. 277–300: 289.

41. Jan Plamper, The Stalin Cult: A Study in the Alchemy of Power, New Haven, 2012, p. 24. See also Victoria E. Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin, Berkeley, 1997; Red Star over Russia. A Visual History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Death of Stalin. Posters, Photographs and Graphics from the David King Collection, exhibition catalogue, ed. by David King, London, 2009.

42. Karen Kettering, »Domesticating Uzbeks: Central Asians in Soviet Decorative Arts of the Twenties and Thirties«, in Colonialism and the Object. Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, ed. by Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, London, 1998, pp. 95–110; Adrienne L. Edgar, »Emancipation of the Unveiled: Turkmen Women under Soviet Rule, 1924–29«, The Russian Review, No 62, 2003, pp. 132–149; Jörg Baberowski, »Stalinistische Kulturrevolution im sowjetischen Orient«, in Kultur in der Geschichte Russlands. Räume, Medien, Identitäten, Lebenswelten, ed. by Bianka Pietrow-Ennker, Göttingen, 2007, pp. 278–293.

43. Cf. Jan Plamper, »Georgian Koba or Soviet ›Father of Peoples‹? The Stalin Cult and Ethnicity«, in The Leader Cult in Communist Dictatorships. Stalin and the Eastern Bloc, ed. by Apor Balázs, Basingstoke, New York, 2004, pp. 123–140; Yuri Slezkine, »The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism«, Slavic Review, No 53.2, 1994, pp. 414–452.

44. The topos of lifelikeness of a portraited figure is also familiar in the Islamic world. In the late 16th century, the Safavid poet and painter Sadeqi Beg »claims that some paintings are so lifelike that all they lack is speech«, Soucek, 2000 (Footnotenote 19), p. 106.

45. A. Gruzhshi, »O narodnom iskusstve [On the Art of the People]«, in Iskusstvo, No 6, 1937, pp. 107–120: 110.

46. See for instance Chepelev's detailed and ideologically grounded explanation on the usefulness of traditional ornament in these works, Chepelev, 1937 (Footnotenote 40), pp. 122–123.

47. Lev M. Levin, Irino S. Leoshkevich, and Suren E. Saruchanov, Khudozhestvennye kovry SSSR [Artistic Rugs of the USSR], Moscow, 1975, p. 53. For the role of »folklore« considered ornament in Central Asian architecture cf. Greg Castillo, »Soviet Orientalism: Socialist Realism and Built Tradition«, Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, No 8.2, 1997, pp. 33–47: 38–39.

48. Ssorin-Chaikov and Sosnina, 2004 (Footnotenote 40), p. 290. Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov, »On Heterochrony: Birthday Gifts to Stalin, 1949«, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, No 12, 2006, pp. 355–375; Dary Vozhdiam/Gifts to Soviet Leaders, exhibition catalogue, ed. by Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov, Moscow, 2006.

49. Ogonek 50, 1949, p. 10. The English translation is cited after Ssorin-Chaikov and Sosnina, 2004 (Footnotenote 40), pp. 290–291.

50. Ogonek 50, 1949, p. 289. For studies of Russian »Orientalisms« cf. Daniel R. Brower and Edward J. Lazzerini, Russia's Orient: Imperial Borderlands and Peoples, Bloomington, 1997; David Schimmelpfennig van der Oye, Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration, New Haven, 2010; Vera Tolz, Russia's Own Orient. The Politics of Identity and Oriental Studies in the Late Imperial and Early Soviet Periods, Oxford, 2011.

51. Cf. Simon Baker, »A Romanov Coronation Rug«, Halı, No 95, 1997, pp. 90–91.

52. Cf. Elizabeth Rodini, »The Sultan's True Face? Gentile Bellini, Mehmet II, and the Values of Verisimilitude«, in The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, ed. by James G. Harper, Farnham, 2011, pp. 21–40. The type is frequently found in Mughal miniature painting, cf. John Seyller, »Payag«, in Masters of Indian Painting, 2 vols., vol. 1, 1100–1650, ed. by Milo C. Beach, Eberhard Fischer, and B. N. Goswamy, Zurich, 2011, p. 332, Fig. 9.

53. Cf. Bowlt, 2002 (Footnotenote 39).

54. Platon Voronko, Stikhotvoreniya i poemy [Poems and Dramatic Poems], Moscow, 1953, pp. 205–206.

55. Samuil Y. Marshak, »Sodoklad«, in Pervyi vsesoiuznyi s'ezd sovetskikh pisatelei 1934: stenograficheskii otchet [1st Soviet Writers' All-Union Meeting 1934: Stenographic Account], Moscow, 1934, pp. 20–38: 27. The English translation is cited after Catriona Kelly, »Riding the Magic Carpet: Children and Leader Cult in the Stalin Era«, Slavonic and East European Journal, No 49.1, 2005, pp. 199–224: 218.

56. Marshak, 1934, pp. 218–219. In contrast, in English children's literature, carpets are compared to »express trains, only in trains you never can see anything because of grown-ups wanting the windows shut; and then they breathe on them, and it's like ground glass, and nobody can see anything« in Edith Nesbit's 1904 novel The Phoenix and the Carpet, cf. Flying Carpets, exhibition catalogue, ed. by Philippe-Alain Michaud, Rome, 2012, p. 58.

57. Cf. Jan Plamper, »The Spatial Poetics of the Personality Cult: Circles around Stalin«, in The Landscape of Stalinism: The Art and Ideology of Soviet Space, ed. by Evgeny Dobrenko and Eric Naiman, Washington, 2003, pp. 19–50. For the concept of geopoetics see Susi K. Frank and Magdalena Marszalek (eds.), Geopoetiken: geographische Entwürfe in den mittel- und osteuropäischen Literaturen, Berlin, 2010.

58. Cited after Plamper, 2003 (Footnotenote 58), p. 25.

59. Plamper, 2003, Fig. 2.2.

60. Plamper, 2003, pp. 24–25.

61. See the project Art, Space, and Mobility in the Early Ages of Globalization: The Mediterranean, Central Asia, and the Indian Subcontinent (MeCAIS) 400–1600, directed by Hannah Baader, Avinoam Shalem, and Gerhard Wolf and funded by the Getty Foundation, Los Angeles, which addresses also historiographies and narratives of the 19th–21st centuries, cf. Gerhard Wolf, »Kunstgeschichte, aber wo? Florentiner Perspektiven auf das Projekt einer Global Art History II«, Kritische Berichte, No 40.2, 2012, pp. 60–68.

62. Regarding Iranian and Central Asian carpets see Leonard Helfgott, »Carpet Collecting in Iran, 1873–1883: Robert Murdoch Smith and the Formation of the Modern Persian Carpet Industry«, Muqarnas, No 7, 1990, pp. 171–181; Svetlana Gorshenina, The Private Collections of Russian Turkestan in the Second Half of the 19th and Early 20th Century, Berlin; 2004, esp. pp. 92–94. For the relationship between Russia and Central Asia at that time see Seymour Becker, Russia's Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865–1924, London, 2004; Alex Marshall, The Russian General Staff and Asia: 1800–1917, London, 2006; Daniel Brower, Turkestan and the Fate of the Russian Empire, London, 2003.

63. Cf. Rodris Roth, »Oriental Carpet Furniture: A Furnishing Fashion in the West in the Late Nineteenth Century«, Studies in the Decorative Arts, No 11.2, 2004, pp. 25–58; G. Lownds, »The Turkoman Carpet as a Furnishing Fabric«, in Turkoman Studies I. Aspects of the Weaving and Decorative Arts of Central Asia, ed. by Robert Pinner and Michael Franses, London, 1980, pp. 96–101. Susan Day, »A connoisseur and a Gentleman. Jules Maciet and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs«, in Halı, 153, 2007, pp. 92–101.

64. See Footnotenote 29.

65. Cf. Wolfgang Brassat, Tapisserien und Politik. Funktionen, Kontexte und Rezeption eines repräsentativen Mediums, Berlin, 1992.

66. Cf. Carpets and Textiles in the Iranian World 1400–1700. Proceedings of the Conference held at the Ashmolean Museum on 30–31 August 2003, ed. by Jon Thompson, Daniel Shaffer, and Pirjetta Mildh, Oxford, Genoa, 2010.

67. Although weavers are at times known by name throughout the history of Soviet carpet weaving, this craft was also collectivized. The first Carpet Union was founded in the TSSR in 1929. In 1933, it comprised already 27,000 artisans (weaving both ornamental and figurative carpets). For the social history of the weaving of portrait carpets, as well as for the cooperation between weavers and painters see Istorija, 1975 (Footnotenote 32), pp. 181–183, 254–255, 345–346, 422–423. See also Adrienne Edgar, »Genealogy, Class, and ›Tribal Policy‹ in Soviet Turkmenistan, 1924–1934«, Slavic Review, No 60.2, 2001, pp. 266–288.

68. Cf. Nigel Lendon, »Beauty and Horror. Identity and Conflict in the War Carpets of Afghanistan«, in Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence. The Proceedings of the 32nd International Congress in the History of Art, ed. by Jaynie Anderson, Carlton, 2009, pp. 678–683; Enrico Mascelloni, War Rugs. The Nightmare of Modernism, Milan, 2009.

70. For the relationship between image, medium, and body cf. Belting, 2011 (Footnotenote 11). For artistic receptions of the courtly and the royal body see Footnotenote 18.