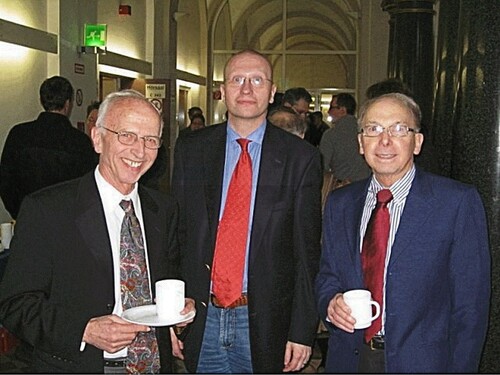

On 12 December 2019, our colleague and friend Professor Dr. Gerhard H. Findenegg (cf. Figure ) passed away after just having completed the eighty-first year of his life. He leaves behind his wife Irmgard Findenegg-Gröll with whom he was married for fifty-four years, their three daughters Klara, Helene, and Eva with their spouses, and seven grandchildren. The Findenegg family lost a loving and caring husband, father, father-in-law, and grandfather who cannot be replaced. At the moment of writing this foreword our thoughts are once again with Gerhard's family.

As his colleagues, we lost a great scientist, an inspiring academic teacher, a wise counsellor as well as a wonderful human being with whom it was always stimulating to interact regardless of whether this interaction was a professional one or in the more private realm. One could engage in deep conversations with Gerhard on almost any topic ranging from international politics over philosophical and social issues all the way to music.

Gerhard was born on 16 November 1938 in Klagenfurt (Austria) where he grew up. During 1944–1948 he attended elementary school in Klagenfurt and St. Georgen, also in Austria. He then moved on to grammar school, again in Klagenfurt, and finished his pre-university education with a baccalaureate degree (Abitur) in 1956 at the age of eighteen. In that same year, Gerhard began his undergraduate studies in Chemistry at the Technische Universität Wien. After graduating in 1960 he moved to the Universität Wien where he enrolled in graduate programmes in Chemistry and Physics. He completed his graduate studies in 1961 and was awarded his doctoral degree at the Universität Wien in 1965. The topic of his thesis was ‘Calorimetric Studies of Non-Electrolyte Solutions’. The Viennese years were an especially important period in Gerhard's life not only from a scientific perspective, but also from a private one because he became acquainted with Irmgard Gröll. The two were married in the same year that Gerhard received his doctoral degree.

After his years in Vienna another important period in Gerhard's life was about to begin in 1966 when the Findeneggs moved to Bristol (United Kingdom) where they stayed until 1968. Gerhard accepted an offer by Douglas H. Everett to become a postdoctoral fellow under his guidance. Everett initiated Gerhard's lifelong interest in adsorption and the wetting of surfaces and interfaces.

The time in Bristol was also a particularly happy period for the young family. Gerhard and Imgard Findenegg's eldest daughter Klara was born in 1967. Irmgard Findenegg has many happy memories of the time spent in Bristol to this day. Coming from a post-World War II Austria, she and Gerhard were completely fascinated by the democracy and the liberty they both experienced in the United Kingdom at the time.

In 1968, after returning from Bristol, Gerhard took up a position as a research assistant, again at the Universität Wien. There he completed his Habilitation in 1973 with a thesis entitled ‘Ordering phenomena at liquid-solid interfaces’, research that was clearly influenced and inspired by his time with Douglas H. Everett in Bristol. In the same year, Gerhard became a professor of Physical Chemistry at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany where he stayed until 1991; he served as Dean of the Faculty of Chemistry during the period 1989-1990.

In 1991 Gerhard left Bochum and accepted an offer from the Technische Universität Berlin (Germany) for one of the Chairs in Physical Chemistry which he held until his retirement in 2005. However, even after retirement, Gerhard remained scientifically active literally until he passed away: his last research paper appeared in print shortly after he was deceased.

Gerhard was an inspiring academic teacher who excelled in the clarity of his presentation and the precision of his writing on the blackboard. He quickly became famous and popular for the lucidity of his lectures among students attending his classes. This was already the case in Bochum and lasted in Berlin for many years after his retirement. Gerhard substituted his younger colleagues Michael Gradzielski and Regine v. Klitzing on numerous occasions if the two had other conflicting appointments. It is particularly noteworthy that Gerhard continued to ‘step into the breach’ so to speak until he reached his late seventies. To appreciate this, one needs to know that it takes about an hour by public transportation to get from Gerhard's former home located on the outskirts of Berlin to the university and that some classes in Physical Chemistry start as early as 8am during the winter months.

Gerhard was full of unconventional thoughts and ideas in conversations with others. He would always treat his conversation partners with politeness and with utmost respect. When on the rare occasion Gerhard regarded another person's response as slightly out of place he would reply ironically with a great sense of humour which usually made the other person reconsider his/ her point of view, laugh, or simply become quiet. In any event, anyone who ever had the privilege to experience these enlightening conversations with Gerhard will surely agree that one always learned something new from talking with him. Most of the time one would look at one's own initial opinions from a different perspective.

Gerhard also had a great knowledge and expertise in music. Among all the different periods of classical music, he was particularly fond of music from the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, he also enjoyed the music of composers of the so-called first and second Viennese Schools. Gustav Mahler ranked prominently among Gerhard's favourite musicians. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, Mahler was both a famous conductor and an equally well-known and influential composer. In the 1960s, when Gerhard was a young man, Mahler was very gradually rediscovered in post-World War II Austria and Germany after having been banned in both countries during the Nazi regime. In the 1960s students were again beginning to study the scores of Mahler's symphonies intensively, rediscovering him as a modern composer of the twentieth century. Gerhard was part of that rediscovery. He maintained a lifelong love for Mahler's overwhelming orchestral pieces.

When German and international friends and colleagues of Gerhard were informed of the very sad news of his death, we received a large number of very moving statements. During an interaction between George Jackson and Martin Schoen at that time, it was suggested by George that Gerhard be honoured with a memorial issue of Molecular Physics. Martin then quickly assembled a team of guest editors (Bob Evans, Jürgen P. Rabe, and Matthias Thommes) to handle the review process once papers had been submitted. This team was completed by George in his capacity as an in-house editor of Molecular Physics. We are also very pleased that Keith E. Gubbins offered to contribute his own personal memories of Gerhard to this foreword which was very much welcomed.

To assemble a team of two theorists and two experimentalists was a good decision because of Gerhard's own broad scientific interests. Gerhard is widely known and well-remembered by his peers in the scientific community for a multitude of scientific achievements including the thermodynamics of interfaces in soft matter, the physical chemistry of surfactant solutions, the adsorption in confined systems and nanomaterials, and the characterisation of materials with X-ray diffraction to name but a few salient areas [Citation1–225]. As a consequence, we now bring together this memorial issue with high-quality contributions from various areas of experimental and theoretical soft matter science and statistical physics.

Naturally, the memories that each author of this foreword has of Gerhard are different. The two people who knew Gerhard for the longest time are Keith and Martin (cf. Figure ). In both cases, this dates back to the late 1970s. Keith was already a well-established professor of Chemical Engineering at Cornell University then, while Martin was a second-semester student of Chemistry at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum before becoming Gerhard's colleague at the Technische Universität Berlin much later in life. Keith shares with readers of this memorial issue the following personal reminiscences of Gerhard:

I first met Gerhard Findenegg in the late 1970s, while visiting Ruhr-Universität Bochum. His doctoral thesis had been on the topic of calorimetric studies of non-electrolyte solutions, under the supervision of Friedrich (‘Fritz’) Kohler, at the Universität Wien. After receiving his doctorate in 1965 he spent several years as Research Assistant at the Universität Wien, and two years as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bristol, with Douglas H. Everett, a well-known expert on physical adsorption. There he worked on the statistical mechanics of chain molecules adsorbed at liquid-solid interfaces. On completing his Habilitation at the Universität Wien, he took up a position as Professor of Physical Chemistry at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum in 1973, and remained there until 1991. Bochum was becoming a centre for research on thermodynamics and statistical mechanics of liquids at the time, counting Gerhard M. Schneider, a world-renowned authority on high-pressure fluid-phase equilibria and supercritical fluid extraction, on its staff. At the Institute of Physics, Johann Fischer, another former doctoral student with Fritz Kohler, was assistant professor, working on the statistical mechanics of adsorption. Not long after Findenegg moved to Bochum, Fritz Kohler left Vienna and joined the Ruhr-Universität Bochum as Professor of Thermodynamics. With the completion of this Viennese trio, Bochum became a center of note in both experimental and theoretical studies of liquids and adsorption.

Somewhat later, in 1984, Findenegg spent a sabbatical at Cornell as Visiting Professor of Chemistry, and I got to know him quite well then. Through several discussions on adsorption and the interfacial phenomena of liquids, I grew to have great respect for his deep insight. While mainly known for his fine experimental work, he had an unusually good knowledge of statistical mechanics and molecular simulation, and this greatly assisted his interpretation of his experimental findings. After he moved to the Technische Universität Berlin (TUB) in 1991, I took the opportunity to visit him when I could, knowing that he would have interesting new research projects and results that meshed with my interests. He had a rather grand suite of offices, which included a conference room, and we would each discuss our recent results and interests. During this discussion, his assistant, Christiane Abu-Hani, would bring us coffee and cookies, something that greatly impressed me, as it would be almost unheard of nowadays in the United States.

Starting in 2002 Gerhard would visit us periodically at North Carolina State University (NCSU) to discuss mutual research interests, and this led to our collaborating on the adsorption of non-ionic surfactants on solid adsorbents. Gerhard had discovered that, in contrast to the usual behaviour in which the adsorption decreases with increasing temperature, for non-ionic surfactants the opposite was the case, at least at near-ambient conditions. Henry Bock (a former doctoral student with Martin Schoen), who at the time was a postdoctoral associate with us in Raleigh, set to work to investigate this intriguing finding. Through a combined theory and molecular simulation study [184], we were able to show that this unusual behaviour was an entropic effect that resulted from the breaking of hydrogen bonds between the hydrophilic head of the surfactant molecules and the water solvent as the temperature was raised. In 2005 Gerhard was appointed Adjunct Professor in the Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering at NCSU, and then his visits became more frequent.

In 2009, a joint research programme on ‘Self-Assembled Soft-Matter Nanostructures at Interfaces’ was proposed, involving TUB, the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, the Max-Planck Institut für Kolloid- und Grenzflächenforschung in Potsdam (Germany), NCSU, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (later joined by Duke University) on the U.S. side. The following year the German team of 11 faculty were awarded a generous grant from the German Science Foundation [International Graduate Research Training Group (IRTG) 1524], and a matching grant was obtained from the U.S. National Science Foundation on the U.S. side. These funds provided for the exchange of doctoral students and faculty over the next nine years (cf. Figure ). Gerhard was one of the key principal investigators in this effort, collaborating with NCSU faculty on various projects, and welcoming their students to his laboratory in Berlin.

With the advent of the IRTG, he would visit us in Raleigh about once a year. During these visits he was generous with his time, meeting with each of my graduate students and postdocs to discuss their research, and offering helpful suggestions. He was much admired by them as a result of this, and for the kindness and consideration he showed to them. During these visits, my wife Pauline and I would usually go with him to our weekend house on the Pamlico River, where he would go jogging at dawn each day. In addition to his science, he was a convivial conversationalist, and knowledgeable about many subjects. We learned much from him about music, art, and European politics. I remember one year we had gone with him to a concert in Raleigh which featured music by Franz Liszt. Over dinner, Gerhard regaled us with anecdotes about Liszt, who was a leader of the New German School of Music. For some reason the one I recall concerned Brahms, who did not approve of the New School of Music, and regarded Liszt as an upstart of limited talent. He would refer to Liszt as ‘that noisemaker from Weimar’.

Gerhard is greatly missed here. We were privileged to know him.

At about the same time as Keith, Martin became acquainted with Gerhard. Martin's memories of Gerhard as an academic teacher, as a scientist, and as a close friend are the following:

My first experience with Gerhard Findenegg was as a second-semester Chemistry student at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. It was my first class in Physical Chemistry, and Gerhard taught a course on Phenomenological Thermodynamics. At the beginning of the first lecture a somewhat small, almost dainty, but agile man entered the lecture hall and quickly went to the podium to begin his lecture. After greeting the class in his distinctly Austrian, charming timbre, he quickly glanced at his notes, put them aside, and started his lecture. During the entire presentation he did not look at his notes again but instead presented his material from memory, something I cannot do and never learned to do even towards the end of my own academic career. This style of Gerhard's lecturing persisted throughout the entire semester. We students were also very much impressed by the clarity of Gerhard's writing and drawing on the blackboard. In addition, he succeeded to overcome the proverbial Mathematics phobia of Chemistry students at least to a certain degree. This quality persisted during the Berlin years as I have been told by some of my own doctoral students who occasionally experienced Gerhard in class many years later.

One of my favourite anecdotes involving Gerhard as an outstanding academic teacher happened when I sat next to him during a scientific talk in the lecture theatre in which I used to teach regularly. The lecture hall is equipped with six blackboards, stacked behind each other in two groups of three each. In the morning of the same day, I had been teaching my statistical thermodynamics class and had forgotten to sponge off the two farthest blackboards in the back. They became visible during the discussion following the seminar talk. Suddenly Gerhard turned to me whispering: ‘Did you give a lecture here today?’. I said: ‘Yes, why?’ and he responded, saying: ‘I am concluding this from the very clear and neat writing and the organization of the material on the blackboard.’ To me, this was the greatest accolade from the grandmaster among all the academic teachers I ever came across.

Gerhard was a particularly broad academician with a strong interest in theoretical work while he himself was an excellent and outstanding experimentalist. This breadth is illustrated by his involvement in theoretical courses. Before I was appointed as Professor of Theoretical Chemistry my position was vacant for a number of years. I only found out later that throughout those years Gerhard had been teaching all the courses in Statistical Thermodynamics to keep this topic an active area of teaching in the department. This sense of responsibility and service was always one of his virtues. Anyone getting a hold of a copy of his book on Statistical Thermodynamics (in German with T. Hellweg) [215] will surely find that he truly mastered this field in its entirety.

Because of Gerhard's strong interest in theoretical work, I had the privilege to publish with him on a number of occasions. Gerhard's approach to experimental versus theoretical methods is perhaps best characterized by saying that as an eminent experimentalist he had a deep understanding of the limitations of experiments. He also understood and appreciated the inherent limitations of theory. This quality is rarely met in science and only the greatest of spirits possess it.

The titles of two of Gerhard's publications with me illustrate how he could intertwine experiment and theory. The first example from 2005 is entitled ‘Phase behavior and local structure of a binary mixture in pores: Mean-field lattice model calculations for analysing neutron scattering data’ (with D. Woywod, S. Schemmel, and G. Rother) [162]. It is an attempt to understand the phase behaviour of an isobutyric acid-water mixture in a controlled-pore glass with simple mean-field lattice-gas calculations carried out by my former doctoral student D. Woywod. The second example from 2017 entitled ‘Adsorption and depletion regimes of a nonionic surfactant in hydrophilic mesopores: An experimental and simulation study’ (with G. Rother, D. Müter, and H. Bock) [221] is a piece of work in which we investigated the different behaviour of a short-chain surfactant in porous silica glass by neutron scattering and extensive molecular dynamics computer simulations.

During the Berlin years and especially in the years after Gerhard's retirement he became a close friend of mine and a highly valuable counsellor whenever I found myself in difficult and challenging situations with colleagues. I would then take a particular route for my walk from home to the office. This route would take me to a point from where I could see Gerhard's office window. Usually, after 8am when the lights were on, I called him from my office and asked if he would give me a couple of minutes of his time. We then sat down in his office and I explained the situation. He would listen, think calmly, and then finally give me his point of view and some advice of how the situation could be resolved best. This advice was always extremely helpful especially in politically difficult situations at the university of which I had to master plenty. Because of Gerhard's death, I feel deprived of this advice and sadly miss him as a wise counsellor.

Shortly after the celebration of his eightieth birthday Gerhard became seriously ill and stopped coming to the office regularly. However, we remained in contact by several phone calls throughout 2019. He would not say much about his health because Gerhard was a rather discrete person who did not want to take centre stage with private and personal matters. However, I do recall that these phone calls usually ended by him saying something optimistic like: ‘I will soon be back at the office.’ On 16 November 2019, I called Gerhard on his birthday for the last time. It took quite some time for him to come to the phone and we only talked very briefly but he seemed to appreciate that I called as always during the last few years. However, this time the phone call did not end in the positive and optimistic tone as all the others throughout this final year of Gerhard's life. Instead, he said: ‘Martin, I don't think I will ever come back.’ These were his last words to me.

What I will always remember about Gerhard Findenegg besides all of the other virtues and scientific achievements that we are honouring here is the portrait of a modest, humble, and discrete man, someone who treated others always with politeness no matter what occasion. To me he remains a role model for how you can be a great scientist and a pleasant and enjoyable person at the same time.

Bob Evans and Gerhard became acquainted as a result of their shared interests in the adsorption and wetting of surfaces and interfaces. In particular, Bob was fascinated by Gerhard's important experimental work on critical adsorption, namely how the Gibbs adsorption diverges in the vicinity of the critical point, reflecting the diverging correlation length. Over the years they met on numerous occasions and became personal friends.

Jürgen Rabe also interacted very closely with Gerhard right from the very beginning when Jürgen became a Professor of Polymer Physics at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. A couple of years later Jürgen succeeded Gerhard as chairman of the Collaborative Research Center 448 ‘Mesoscopically structured composites’ which Gerhard initiated in 1998. Later, when the International Graduate Research Group 1524 ‘Self-assembled Soft Matter Nanostructures at Interfaces’ was established, with Keith and Martin as co-chairs, Jürgen and Gerhard served on the steering committee for nine years. Jürgen recalls:

My first encounter with Gerhard Findenegg occurred in 1990 through my studies of his insightful papers on the adsorption of long-chain alkanes and amphiphiles from organic solutions to the basal plane of graphite. Particularly interesting for me was his view of the two-dimensional crystallization of molecular adsorbates on the chemically inert and atomically flat graphite surface, because it did not require a lattice match between substrate and adsorbate (Findenegg & Liphard, 1987) [62]. This was very different from what I knew from semiconductor physics with reconstructions at interfaces being key, and it inspired me to draw conclusions on the ‘commensurability and mobility in two-dimensional molecular patterns on graphite’ (Rabe & Buchholz, 1991). In fact, this became the starting point for much more to come. We had home-built a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM), allowing video-rate imaging of molecules at atomic scale resolution. However, the high impact in the long run, had to come from establishing also a very good understanding of the chemical physics of interfaces, which was not really well established in German universities’ physics departments at the time. Physical chemists, therefore, had to teach the up-coming chemical physicists, and Gerhard was very important for me in this regard. This led to the establishment of a highly versatile technique, to investigate hybrid systems from inorganic solid surfaces and molecules. Soon, other (semi-)conducting layered crystals could also be employed and today the technique is applied further to the still growing area of 2D-materials, which now not only serve as substrates but also as covers, forming flexible slit-pores, which may be filled by molecules.

My second encounter with Gerhard Findenegg was a long train ride in the mid-1990s, where we had ample time to talk. Both of us were appointed to Berlin: Gerhard from Ruhr-Universität Bochum to Technische Universität Berlin, and I from Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität Mainz to Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, which after the German Unification in 1989 had been largely restructured. During this train ride, I got the clear impression that Gerhard Findenegg welcomed me very warmly, even if Humboldt-Universität had now also become a competitor for local resources. It was the start of a wonderful interaction with Gerhard and also polymer scientists in all of Berlin including Freie Universität Berlin, the Federal Institute of Materials Research, as well as in the surrounding State of Brandenburg Universität Potsdam, the newly founded Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces, and the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Polymer Research. Notabene, West Berlin had its Berlin Association of Polymer Research, but the new appointees in the east of Berlin and Brandenburg were now also invited, which led to the larger Berlin-Brandenburg Association of Polymer Research (BVP).

With this strength, the next logical step was the formation of a big consortium, to acquire a Collaborative Research Center (CRC), funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG). Its title ‘Mesoscopically Organized Composites’ was ideally suited to the competences of the scientific community in the Berlin-Brandenburg area with its four Universities and the surrounding major research institutes, and also timely in the growing field of nanoscience. The CRC 448 was established in 1998, and of course, Gerhard, the physical chemist became the spokesperson, with A.-Dieter Schlüter, the synthetic chemist from Freie Universität Berlin, as the deputy. From the very beginning, it was planned to switch chairpersons half way through so as to keep the whole community on board. In 2004 it was my pleasure to follow Gerhard in this capacity as chair, and Martin Schoen became vice chair, the two of us reflecting both experiment and theory. Certainly, it has been a gift to succeed Gerhard in this capacity, since the whole scientific structure was carefully considered. I learned a lot from it, and I benefitted from this for other endeavours since then.

Gerhard's impact remains very visible, currently also in a subsequent collaborative research center, CRC 951 on Hybrid Inorganic/Organic Systems for Opto-Electronics with a spokesperson from the next scientific generation, Norbert Koch from Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. We miss Gerhard as the insightful and caring person he was, but we keep being reminded of him, when we see what came of it.

Matthias Thommes started in Gerhard´s group as Master (Diplom-Chemiker) student, then continued as a doctoral student at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum and finally moved with him to Berlin in 1991. In the early days in Berlin, Matthias assisted Gerhard in building a new research group there. After obtaining his doctoral degree with Gerhard, Matthias spent one and a half years at the University of Maryland at College Park, USA and then took a position in industry in the US where he quickly moved up the ranks to become Scientific Director at Quantachrome Corporation (Boynton Beach, FL), before moving back to academia now as Professor of Chemical Engineering at the Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen. Matthias recalls:

The first time I saw Gerhard Findenegg was in 1984/85 as a student in the second semester of Chemistry at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. Gerhard was teaching Thermodynamics, which was a mandatory course for all Chemistry students. While I was extremely impressed by the clarity and enthusiasm of his teaching, I could not foresee that a few years later I would be joining his research group, completing both my diploma thesis and PhD thesis under his supervision. However, these first lectures by Gerhard made me interested in Physical Chemistry; in fact, I had come to the Ruhr-Universität Bochum with the goal of majoring in Biochemistry. Finally, I decided to pursue Physical Chemistry and joined Gerhard´s research group in 1988.

During my PhD thesis, we moved with part of our scientific group from Bochum to the Technische Universität in Berlin, as Gerhard had accepted in 1991 the offer to become the Head of the Iwan-N-Stranski Institute (one of the Chairs of Physical Chemistry) of the Technische Universität Berlin. It was an extremely exciting time to be in Berlin, just after the re-unification of Germany, and to have the chance to contribute to the challenging task of successfully setting-up a new research group. To be a student of Gerhard was for me an extremely great privilege and honour. Not only did I learn how to perform careful and reliable experiments, but Gerhard always emphasized the necessity to combine these with theoretical and molecular simulation-based approaches so as to gain a deep understanding of the experimental findings at the microscopic level. This turned out to be an extremely strong fundament to address opportunities and challenges throughout my professional career.

Very often, I think about the frequent scientific meetings with Gerhard during my PhD thesis, which were always a true highlight. At the end of these meetings, I was even more enthusiastic about my research and was full of new ideas. Gerhard Findenegg was a fantastic academic teacher and PhD advisor but also a life-long mentor to me, who would give guidance and advice not only with regard to scientific questions, but also with regard to other important professional questions throughout my career. Gerhard was a true role model not only as a scientist but also as a great person, who always had an open ear for the concerns of his students and co-workers.

Later, when I was working and living with my family in South Florida, Gerhard and Irmgard would visit, often in connection with their visits to North Carolina State University. I am also grateful that Gerhard accepted to lecture at various CPM (Characterization of Porous Materials) symposia (cf. Figure ), which I co-organized with my colleague Prof. Alexander Neimark from Rutgers University. Since 2012, this symposium is being held on a tri-annual basis in Delray Beach FL. We were thrilled that Gerhard was able to attend the CPM-8 meeting in May 2018, where he delivered a wonderful plenary lecture on a novel method for depositing metal oxide nanoparticles in mesopores via eutectic freezing. He had also served as a member of the Honorary Advisory Committee for this well-established symposium series in the area of adsorption and porous materials characterisation.

Figure 4. Gerhard Findenegg and Matthias Thommes at the CPM-7 Symposium, Delray Beach, Florida, USA (2015).

Gerhard is greatly missed and I am extremely grateful and privileged that I had the opportunity to be his student and then later continued to interact with him on both a personal and professional level.

The Editors of Molecular Physics are very honoured to introduce this memorial issue of the journal celebrating Gerhard Findenegg's scientific achievements. The Chair of Editors, George Jackson, first met Gerhard during a research visit to the group of Ian McLure at the University of Sheffield in the early 1990s; George was a young lecturer at the time and had just become an editor of Molecular Physics. The stimulating series of seminars by Gerhard sparked George's long-time interest in the physical properties and phase behaviour of surfactant systems. The contributions by his collaborators, colleagues, and friends collected in this memorial issue are but a small testament of the highest regard and esteem in which Gerhard is held.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

Gerhard Findenegg's Publications:

- G.H. Findenegg, K. Gruber, J.F. Pereira and F. Kohler. Kalorimetrische Messungen an Mischungen von Nichtelektrolyten, Monatsh. Chem. 96, 669–678 (1965). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00909485

- F. Kohler and G.H. Findenegg. Berechnung der thermodynamischen Daten eines ternären Systems aus den zugehöri-gen binären Systemen, Monatsh. Chem. 96, 1228–1251 (1965). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00904272

- G.H. Findenegg, F. Kohler and E. Wilhelm. Wärmekapazität von Polytetrafluoräthylen im Bereich der Umwandlungserscheinungen zwischen 16 und 34°C, Monatsh. Chem. 97, 94–98 (1966). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00905490

- G.H. Findenegg and F. Kohler. Molar Heat Capacity at Constant Volume of Binary Mixtures of 1,2-Dibromo- and 1,2-Dichloroethane with Benzene, Trans. Faraday Soc. 63, 870–878 (1967). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9676300870

- H.E. Affsprung, G.H. Findenegg and F. Kohler. Volumetric and Dielectric Behaviour of Acetic Acid in Mixtures with Nonpolar Liquids, J. Chem. Soc. (London) A. 1968, 1364–1370 (1968). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/j19680001364

- S.G. Ash, D.H. Everett and G.H. Findenegg. Thermodynamics of Adsorption from Solution: Part 3. – The Parallel Layer Model, Trans. Faraday Soc. 64, 2639–2644 (1968). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/TF9686402639

- S.G. Ash, D.H. Everett and G.H. Findenegg. Multilayer Theory for Adsorption from Solution: Mixtures of Monomers + Dimers, Trans. Faraday Soc. 64, 2645–2666 (1968). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9686402645

- E. Wilhelm, R. Schano, G. Becker, G.H. Findenegg and F. Kohler. Molar Heat Capacity at Constant Volume: Binary Mixtures of 1,2-Dichloro- and 1,2-Dibromoethane with Cyclohexane, Trans. Faraday Soc. 65, 1443–1455 (1969). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9696501443

- D.H. Everett and G.H. Findenegg.: A new Precision Enthalpy of Wetting Calorimeter, J. Chem. Thermodynam. 1, 573–578 (1969). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9614(69)90017-2

- D.H. Everett and G.H. Findenegg. Calorimetric Evidence for the Structure of Films Adsorbed at the Solid/Liquid Interface: The Heat of Wetting of Graphon by Some n-Alkanes, Nature. 223, 52–53 (1969). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/223052a0

- G.H. Findenegg. Influence of a Solid Surface on the Density of a Liquid Film, Proc. Intern. Conf. Calorimetry and Thermodynamics, Warschau, 347–351 (1969).

- S.G. Ash, D.H. Everett and G.H. Findenegg. Multilayer Theory for Adsorption from Solution: A General Theory for the Adsorption of r-Mers and its Application to Flexible Tetramers and Trimers, Trans. Faraday Soc. 66, 708–722 (1970). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9706600708

- G.H. Findenegg. Dichte und Ausdehnungskoeffizient Einiger Flüssiger Alkane, Monatsh. Chem. 101, 1081–1088 (1970). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00908551

- S.G. Ash and G.H. Findenegg. Boundary Layers of Pure Liquids at the Graphon Surface, Special Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1, 105–111 (1970). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/sd9700100105

- S.G. Ash and G.H. Findenegg. Calculation of the Interaction Energy Between two Parallel Adsorbing Planes Immersed in a Solution Composed of Molecules of Different Size, Trans. Faraday Soc. 67, 2122–2128 (1971). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/tf9716702122

- G.H. Findenegg. The Volumetric Behaviour of Hydrocarbon Liquids Near the Graphon Surface, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 35, 249–253 (1971). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(71)90117-2

- G.H. Findenegg. Order-disorder Transitions at the Liquid/Solid Interface: Volumetric Behaviour of Primary Aliphatic Alcohols Near the Graphon Surface, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 (68), 1799–1806 (1972). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/f19726801799

- G.H. Findenegg and F. Kohler. Polyatomic Molecules (Chap. 10), Molecular reorientation in liquids (Chap. 11), Associated liquids (Chap. 12). in The Liquid State, edited by F. Kohler (Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1972); ISBN 3-527-25390-4

- G.H. Findenegg. Ordered Layers of Aliphatic Alcohols and Carboxylic Acids at the Pure Liquid/Graphite Interface, J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 (69), 1069–1078 (1973). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/f19736901069

- G.H. Findenegg. Dichte und Ausdehnungskoeffizienten einiger flüssiger Alkohole und Carbonsäuren, Monatsh. Chem. 104, 998–1007 (1973). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00903916

- F. Kohler, G.H. Findenegg and M. Bobik. Mixtures of Trifluoroacetic Acid with Acetic Acid and Carbon Tetrachloride, J. Phys. Chem. 78, 1709–1714 (1974). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/j100610a006

- G.H. Findenegg. Physical Adsorption of Fluids at High Temperatures and High Pressurs, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 78, 1281–1285 (1974). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19740781202

- G.H. Findenegg and J. Fischer. Adsorption of Fluids: Simple Theories for the Density Profile in a Fluid Near an Adsorbing Surface, J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Discuss. 59, 38–45 (1975). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/dc9755900038

- H. Kern and G.H. Findenegg. Grenzschicht langkettiger flüssiger n-Alkane an Graphitoberflächen, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 79, 1162 (1975) (Kurzmitteilung).

- G.H. Findenegg, H. Kern and W. von Rybinski. Prefreezing of n-Alkanes Near Graphite Surfaces, Proc. Fourth Int. Conf. Chem. Thermodyn. VII (4, (1975). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(77)90012-1

- J. Specovius and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption von Gasen bei erhöhten Drücken, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 80, 1232 (1976) (Kurzmitteilung). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.197800007

- H. Kern, W. von Rybinski and G.H. Findenegg. Prefreezing of Liquid n-Alkanes Near Graphite Surfaces, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 59, 301–307 (1977). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(77)90012-1

- D. Baumer, H. Mang and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption perfluorierter Kohlenwasserstoffe an Wasseroberflächen, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 81, 1101 (1977) (Kurzmitteilung).

- J. Specovius and G.H. Findenegg. Physical Adsorption of Gases at High Pressures: Argon and Methane Onto Graphitized Carbon Black, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 82, 174–180 (1978). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.197800007

- J. Fischer, J. Specovius and G.H. Findenegg. Quantitative Beschreibung der Adsorption von Gasen bei erhöhten Drücken, Chem.-Ing.-Techn. 50, 41–42 (1978). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.330500109

- M. Große-Rhode and G.H. Findenegg. Formation of Ordered Monolayers of Alkanes at the Cleavage Face of Nickel Chloride, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 64, 374–376 (1978). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(78)90375-2

- H.E. Kern, A. Piechocki, U. Brauer and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption from Solution of Chain Molecules Onto Graphite: Evidence for Lateral Interactions in Ordered Monolayers, Progr. Colloid Polymer Sci. 65, 118–124 (1978). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0117210

- D. Baumer, H. Mang and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Polar Molecules on the Surface of Water, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 82, 878–882 (1978). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19780820914

- W. von Rybinski and G.H. Findenegg. Chromatographic Study of Mixed gas Adsorption by the Step-and-Pulse Method, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 83, 1127–1130 (1979). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19790831123

- H. Mang and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Study of Surfactant Adsorption at the Aqueous Solution/air Interface, Colloid Polymer Sci. 258, 428–432 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01480836

- H.E. Kern and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption from Solution of Long-Chain Hydrocarbons Onto Graphite: Surface Excess and Enthalpy of Displacement Isotherms, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 75, 346–356 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(80)90460-9

- M. Liphard, P. Glanz, G. Pilarski and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Carboxylic Acids and Other Chain Molecules from n-Heptane Onto Graphite, Progr. Colloid Polymer Sci. 67, 131–140 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0117393

- J. Specovius and G.H. Findenegg. Study of a Fluid/Solid Interface Over a Wide Density Range Including the Critical Region. I. Surface Excess of Ethylene/Graphite, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 84, 690–696 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19800840715

- G.H. Findenegg and J. Specovius. Study of a Fluid/Solid Interface Over a Wide Density Range Including the Critical Region. II. Spreading Pressure and Enthalpy of Adsorption of Ethylene/Graphite, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 84, 696–701 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19800840716

- W. von Rybinski, M. Albrecht and G.H. Findenegg. Study of the Interaction Between Adsorbed Hydrocarbon Molecules on Graphitized Carbon Black Using the Chromatographic Step-and-Pulse Method, Faraday Symposia Chem. Soc. 15, 25–37 (1980). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/fs9801500025

- R. Löring and G.H. Findenegg. The Liquid/Solid Interface of Propane/Graphite. Surface Excess Measurements Over a Wide Temperature Range up to the Critical Point, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 84, 355–361 (1981). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(81)90228-9

- D. Baumer and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Hydrophobic Vapors on the Surface of Water, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 85, 118–127 (1982). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9797(82)90240-5

- U. Fache, G.H. Findenegg, H.E. Kern and M. Liphard. Adsorption at the Graphite/Liquid Interface of a Long-Chain n-Paraffin (Docosane) from Dilute Solutions of non-Polar Solvents. In: Microscopic Aspects of Adhesion and Lubrication (J.M. Georges, ed.) Elsevier, Amsterdam 1982; p. 709–718 ISBN 0-444-42071-1

- M. Albrecht, P. Glanz, G.H. Findenegg: Adsorption Equilibrium of Binary Hydrocarbon Mixtures on Graphitized Carbon Black. In: Adsorption at the Gas-Solid and Liquid-Solid Interface, Vol. 10. (J. Rouquerol and K.S.W. Sing, eds.) Elsevier, Amsterdam 1982; p. 75-88; ISBN 0-444-42087-8

- S. Blümel, F. Köster and G.H. Findenegg. Physical Adsorption of Krypton on Graphite Over a Wide Density Range. A Comparison of the Surface Excess of Simple Fluids on Homogeneous Surfaces, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 (78), 1753–1764 (1982). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/F29827801753

- F. Köster and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption from Binary Solvent Mixtures Onto Silica gel by HPLC Frontal Analysis, Chromatographia. 15, 743–747 (1982). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02261368

- G.H. Findenegg, C. Koch, and M. Liphard. Adsorption of Decan-1-ol from Heptane at the Solution/Graphite Interface, in Adsorption from Solution, edited by R.H. Ottewill, C.H. Rochester, and A.L. Smith (Academic Press, London, 1983), pp. 87–97. ISBN 0-12-530980-5

- G.H. Findenegg, B. Körner, J. Fischer and M. Bohn. Supercritical gas Adsorption in Porous Materials. I. Krypton in Carbon Molecular Sieves, Ger. Chem. Eng. 6, 80–84 (1983).

- J. Fischer, M. Bohn, B. Körner and G.H. Findenegg. Supercritical gas Adsorption in Porous Materials. Prediction of Adsorption Isotherms, Ger. Chem. Eng. 6, 84–91 (1983).

- G.H. Findenegg. High-pressure Physical Adsorption of Gases on Homogeneous Surfaces, in Fundamentals of Adsorption, Vol. 1, edited by A.L. Myers, and G. Belfort (United Engineering Trustees, 1984), pp. 207–218. ISBN 0-8169-0265-8.

- G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption Behaviour of Pure Fluids near the Gas-Liquid Critical Point. Eur. Space Agency, (Spec. Publ.) ESA SP 1983, ESA SP-191 Proc. 4th Eur. Symp. Mater. Sci. Microgravity, 385–391.

- P. Glanz and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Propene and Propane Mixtures on Graphitized Carbon Black. I. Experimental Method and Results, Adsorption Sci. Technol. 1, 41–50 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026361748400100103

- P. Glanz, B. Körner and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Propene and Propane on Graphitized Carbon. II. Analysis of Single gas and Mixed gas Isotherms, Adsorption Sci. Technol. 1, 183–193 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/026361748400100301

- D. Wielebinski and G.H. Findenegg. Measurement of Interfacial Tension in Simple two-Phase Ternary Systems Along an Isothermal Linear Path to the Critical Point, J. Phys. Chem. 88, 4397–4401 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/j150663a043

- G.H. Findenegg and R. Löring. Fluid Adsorption up to the Critical Point. Experimental Study of a Wetting Fluid/Solid Interface, J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3270–3276 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.448036

- B. Heidel and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Study of the Surface of a Liquid Mixture Near a Critical Solution Point, J. Phys. Chem. 88, 6575–6579 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/j150670a020

- S. Blümel and G.H. Findenegg. Critical Adsorption of a Pure Fluid on a Graphite Substrate, Phys. Rev. Letters. 54, 447–450 (1984). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.447

- G.H. Findenegg. Statistische Thermodynamik Band II der Reihe “Grundzüge der Physikalischen Chemie”, edited by R. Haase, Herausgeber (Steinkopff-Verlag, Darmstadt, 1985); ISBN 3-7985-0650-7

- G.H. Findenegg. Thermodynamic and Molecular Aspects of Wetting in Oil-water-Hydrophobic Substrate Systems, in Modern Trends of Colloid Science in Chemistry and Biology, edited by H.-F. Eicke (Birkhäuser, Basel, 1985), pp. 74–96.

- G.H. Findenegg and F. Köster. A new Equation for the Retention of Solutes in Liquid/Solid Adsorption Chromatography with Mixed Mobile Phases, J. Chem.Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 (82), 2691–2705 (1986). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/f19868202691

- U. Bien-Vogelsang and G.H. Findenegg. Monolayer Phase Transitions of Dodecanol at the Liquid/Graphite Interface, Colloids Surf. 21, 469–481 (1986). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-6622(86)80110-X

- G.H. Findenegg and M. Liphard. Adsorption from Solution of Large Alkane and Related Molecules Onto Graphitized Carbon, Carbon. N. Y. 25, 119–128 (1987). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-6223(87)90048-0

- G.H. Findenegg. Experimental and Thermodynamic Aspects of Mixed Gas Adsorption, in: Fundamentals of Adsorption Vol. 2, edited by A.I. Liapis (United Engineering Trustees, New York, 1987), pp. 53–71. ISBN 0-8169-0398-0

- G.H. Findenegg, and M.M. Telo da Gama. Wetting and Adsorption Phenomena, in: Fluid Sciences and Materials Science in Space. A European Perspective, Chap. VI, edited by H.U. Walter (Springer, Berlin, 1987). ISBN 3-540-17862-7

- B. Heidel and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Study of Critical Adsorption at the Surface of a Polymer Solution: Evidence for a Slowly Decaying Interfacial Profile, J. Chem. Phys. 87, 706–713 (1987). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.453567

- C.S. Koch, F. Köster and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Binary Solvent Mixtures in Reversed-Phase Chromatographic Systems. Surface Excess Isotherms and Enthalpies of Displacement, J. Chromatogr. 406, 257–273 (1987). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(00)94034-2

- D. Wielebinski, B. Föllner, K. Selcan, and G.H. Findenegg. Hydrophile-Lipophile Balance and Interfacial Tensions in Water-Hydrocarbon-Surfactant Systems, in Interactions of Water in Ionic and Nonionic Hydrates, edited by H. Kleeberg (Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg, 1987), pp. 241–245.

- R. Süßmann, K. Neumann, G.H. and Findenegg. Hysteresis Effects in the High-Pressure Adsorption of Gases in GRAFOAM Graphite Foam, in Characterization of Porous Solids, edited by K.K. Unger, J. Rouquerol, K.S. Sing, and H. Kral (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1988), pp. 203–212. ISBN 0-444-42953-0

- K. Selcan, K. Köhler and G.H. Findenegg. Interfacial Tensions in Simple oil-Water-Surfactant Systems Near Their Three-Phase Region, Colloid Polymer Sci. 266, 283–290 (1988). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01452591

- D. Wielebinski and G.H. Findenegg. Measurement of low Interfacial Tensions by Capillary Wave Spectroscopy. Study of an oil-Water-Surfactant System Near its Phase Inversion, Progr. Colloid Polymer Sci. 77, 100–108 (1988). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0116767

- G.H. Findenegg, B. Pasucha and H. Strunk. Adsorption of Nonionic Surfactants from Aqueous Solutions on Graphite: Adsorption Isotherms and Calorimetric Enthalpies of Displacement for C8E4 and Related Compounds, Colloids Surf. 37, 223–233 (1989). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-6622(89)80121-0

- R. Süßmann and G.H. Findenegg. Critical Adsorption at the Surface of a Polymer Solution. Analysis of Ellipsometric Data on the Depletion Layer Near the Critical Solution Point, Phys. A. 156, 114–129 (1989). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4371(89)90112-X

- G.H. Findenegg, A. Hirtz, R. Rasch and F. Sowa. Novel Phase Behavior in Three-Component oil-Water-Surfactant Systems. A Truncated Isotropic Channel in the oil-Rich Regime, J. Phys. Chem. 93, 4580–4587 (1989). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/j100348a036

- H. Lewandowski, T. Michalski, and G.H. Findenegg. Multilayer Adsorption and Adsorption/Desorption Hysteresis Phenomena of Fluids Near Their Critical Point, in: Fundamentals of Adsorption, Vol. 3, edited by A. Mersmann (United Engineering Trustees, New York, 1991), pp. 497–506. ISBN 0-8169-0540-1

- A. Hirtz, W. Lawnik and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Study of Critical Adsorption at the Surface of Liquid Mixtures: The System Heptane + Nitrobenzene, Colloids Surf. 51, 405–418 (1990). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-6622(90)80155-W

- T. Rheinländer, H. Dropsch and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption of Short-Chain Polyoxyethylene Alkylethers from Aqueous and non-Aqueous Solutions Onto Graphite, Progr. Colloid Polymer Sci. 83, 59–67 (1990). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0116244

- T. Michalski, A. Benini and G.H. Findenegg. A Study of Multilayer Adsorption and Pore Condension of Pure Fluids in Graphite Substrates on Approaching the Bulk Critical Point, Langmuir. 7, 185–190 (1991). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la00049a033

- K. Bonkhoff, A. Hirtz and G.H. Findenegg. Interfacial Tensions in the Three-Phase Region of Nonionic Surfactant + Water + Alkane Systems. Critical Point Effects and Aggregation Behaviour, Phys. A. 172, 174–199 (1991). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4371(91)90319-8

- A. de Keizer, T. Michalski and G.H. Findenegg. Fluids in Pores: Experimental and Computer Simulation Studies of Multilayer Adsorption, Pore Condensation and Critical-Point Shifts, Pure Appl. Chem. 63, 1495–1502 (1991). doi:https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199163101495

- G.H. Findenegg. Principles of Adsorption on Solid Surfaces and Their Significance in Gas/Solid and Liquid/Solid Chromatography, in Theoretical Advancement in Chromatography and Related Separation Techniques, NATO ASI Series C; Vol. 383, edited by F. Dondi and G. Guiochon (Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1992), pp. 227–260. ISBN 0-7923-1991-5

- G.H. Findenegg, M. Thommes, and T. Michalski. Studies of Critical Point Phenomena of Fluids in Pores and at Interfaces. Proc. VIIIth Europ. Symp. on Materials and Fluid Sciences in Microgravity, Brussels, April 1992, ESA SP-333, pp. 795–800.

- A. Hirtz, K. Bonkhoff and G.H. Findenegg. Optical Studies of Liquid Interfaces in Amphiphilic Systems: How Wetting and Adsorption are Modified by Surfactant Aggregation, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 44, 241–281 (1993). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8686(93)80025-7

- G.H. Findenegg, S. Groß, and T. Michalski. Multilayer Adsorption and Pore Condensation in Controlled-Pore Glass. A Test of the Saam-Cole Theory of Mesopore Filling, in Fundamentals of Adsorption, edited by M. Suzuki (Kodansha, Tokyo, 1993). pp. 161–168. ISBN 4-06-206433-2

- G.H. Findenegg, M. Thommes, and K. Kemmerle. HPT on EURECA: Measurements and First Results, in Proc. of the 44th Congress of the International Astronautic Federation (IAF), IAF-93-J.I.260 (1993).

- G.H. Findenegg, S. Groß, and T. Michalski. Pore Condensation in Controlled-Pore Glass. An Experimental Test of the Saam-Cole Theory, in Characterization of Porous Solids III, edited by J. Rouquerol, F. Rodriguez-Reinoso, K.S.W. Sing, K.K. Unger (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1994), pp. 71–80. ISBN 0-444-81491-4

- M. Thommes, H. Lewandowski and G.H. Findenegg. Critical Adsorption of SF6 on a Finely Divided Graphite Substrate, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 98, 477–481 (1994). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19940980346

- W.H. Lawnik and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Studies of Wetting on low-Energy Surfaces, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 98, 405–408 (1994). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19940980325

- H. Strunk, P. Lang and G.H. Findenegg. Clustering of Micelles in Aqueous Solutions of Tetraoxyethylene-n-Octylether (C8E4) as Monitored by Static and Dynamic Light Scattering, J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11557–11562 (1994). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/j100095a042

- M. Thommes and G.H. Findenegg. Pore Condensation and Critical-Point Shift of a Fluid in Controlled-Pore Glass, Langmuir. 10, 4270–4277 (1994). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la00023a058

- C. Braun, P. Lang and G.H. Findenegg. Surface-induced Shift of the Hexagonal-to-Isotropic Phase Transition in a Lyotropic System Studied by X-ray Reflectivity, Langmuir. 11, 764–766 (1995). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la00003a016

- M. Thommes and G.H. Findenegg. Results of the HPT-Experiment Critical Adsorption on EURECA I, Adv. Space Res. 16, 83–86 (1995). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-1177(95)00274-I

- M. Thommes, G.H. Findenegg and M. Schoen. Critical Depletion of a Fluid in Controlled-Pore Glass. Experimental Results and Grand Canonical Ensemble Monte Carlo Simulation, Langmuir. 11, 2137–2142 (1995). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la00006a048

- E.-M. Kutschmann, G.H. Findenegg, D. Nickel and W. von Rybinski. Interfacial Tension of Alkylglucosides in Different APG/oil/Water Systems, Colloid Polym. Sci. 273, 565–571 (1995). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00658686

- W.H. Lawnik, U.D. Goepel, A.K. Klauk and G.H. Findenegg. Physisorption of Cyclohexane on a SiO2/Si Substrate: Evidence of a Wetting Transition Above the Triple Point, Langmuir. 11, 3075–3082 (1995). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la00008a037

- G.H. Findenegg. Thermodynamik der Grenzflächenerscheinungen in: Lehrbuch der Grenzflächenchemie, Thieme, edited by M.J. Schwuger (Stuttgart, New York, 1996), S. 1-44; ISBN 3-13-137501-9

- M. Thommes, M. Schoen, and G.H. Findenegg. Critical Depletion of Pure Fluids in Colloidal Solids: Results of Experiments on EURECA and Grand Canonical Monte Carlo Simulations, in Materials and Fluids under Low Gravity, Lecture Notes in Physics 464, edited by L.G. Ratke, B. Feuerbacher, H. Walter (Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, 1996), pp. 51–59.

- C. Stubenrauch, E.-M. Kutschmann, B. Paeplow and G.H. Findenegg. Phase Behavior of the System Water + Decane + Decyl Monoglucoside + Decanol, Tenside, Surfactants, Deterg. 33, 237–241 (1996). doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/tsd-1996-330318

- C. Stubenrauch, M. Nydén, G.H. Findenegg and B. Lindman. NMR Self-Diffusion Study of Aqueous Solutions of Tetraoxyethylene n-Octyl Ether (C8E4), J. Phys. Chem. 100, 17028–17033 (1996). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp961741i

- D. Nickel, W. von Rybinski, E.-M. Kutschmann, C. Stubenrauch and G.H. Findenegg. The Importance of the Emulsifying and Dispersing Capacity of Alkyl Polyglucosides for Applications in Detergent and Cleaning Agents, Fett/Lipid. 98, 363–369 (1996). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lipi.19960981105

- A. Hirtz and G.H. Findenegg. The Surface Profile of Aqueous Solutions of an Amphiphile (C10E4) Near Liquid/Liquid Phase Separation Probed by Ellipsometry, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 8, 9541–9546 (1996). doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/8/47/059

- G.H. Findenegg, and M. Thommes. High-pressure Physisorption of Gases on Planar Surfaces and in Porous Materials, in Physical Adsorption: Experiment, Theory and Applications, edited by J. Fraissard, and C.W. Conner, NATO ASI Series C, Vol. 491, 151–179 (1997); ISBN 0-7923-4547-9.

- R. Steitz, C. Braun, P. Lang, G. Reiss and G.H. Findenegg. Preordering Phenomena of Complex Fluids at Solid/Liquid Interfaces, Phys. B. 234-236, 377–379 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-4526(96)00993-3

- Z. Király, R.H.K. Börner and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorption and Aggregation of C8E4 and C8G1 Nonionic Surfactants on Hydrophilic Silica Studied by Calorimetry, Langmuir. 13, 3308–3315 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la9620768

- A. Möller, P. Lang, G.H. Findenegg and U. Keiderling. Micellar Solutions of (-D-Octyl-Glucopyranoside in the Presence of Butanol. A SAXS and Light Scattering Study, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 101, 1121–1128 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19971010807

- Y. Hayami and G.H. Findenegg. Surface Crystallization and Phase Transitions of the Adsorbed Film of F(CF2)12(CH2)16H at the Surface of Liquid Hexadecane, Langmuir. 13, 4865–4869 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la9702446

- C. Stubenrauch, B. Paeplow and G.H. Findenegg. Microemulsions Supported by Octyl Monoglucoside and Geraniol. 1. The Role of the Alcohol in the Interfacial Layer, Langmuir. 13, 3652–3658 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la970180z

- M. Schoen, M. Thommes and G.H. Findenegg. Sorption and Phase Behavior of Near-Critical Fluids Confined to Mesoporous Media, J. Chem. Phys. 107, 3262–3266 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.474707

- G.H. Findenegg and S. Herminghaus. Wetting: Statics and Dynamics, Current Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2, 301–307 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-0294(97)80039-8

- T. Zoungrana, G.H. Findenegg and W. Norde. Structure, Stability, and Activity of Adsorbed Enzymes, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 190, 437–448 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jcis.1997.4895

- J. Schulz, A. Hirtz and G.H. Findenegg. Near-critical Liquid/Liquid Interfaces of Simple and Complex Mixtures Probed by Ellipsometry, Phys. A. 244, 334–343 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4371(97)00298-7

- S. Groß and G.H. Findenegg. Pore Condensation in Novel Highly Ordered Mesoporous Silica, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 101, 1726–1730 (1997). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19971011136

- W. Lawnik, O. Dietsch, A. Fritz, G.H. Findenegg, and S.R. Tennison. Adsorption and Displacement of Formic Acid and Acetic Acid on Microporous Phenolic Resin Carbons, in Characterization of Porous Solids IV, edited by B. McEnaney et al., (The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 1997), pp. 299–305; ISBN 0-85404-782-4.

- Z. Király and G.H. Findenegg. Calorimetric Evidence of the Formation of Half-Cylindrical Aggregates of a Cationic Surfactant at the Graphite/Water Interface, J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 1203–1211 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp972218m

- P. Röcken, A. Somoza, P. Tarazona and G.H. Findenegg. Two-stage Capillary Condensation in Pores with Structured Walls: a non-Local Density Functional Study, J. Chem. Phys. 108, 8689–8698 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.476297

- S. Uredat and G.H. Findenegg. Brewster Angle Microscopy and Capillary Wave Spectroscopy as a Means of Studying Polymer Films at Liquid/Liquid Interfaces, Colloids Surf. A. 142, 323–332 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(98)00360-4

- C. Stubenrauch, S.K. Mehta, B. Paeplow and G.H. Findenegg. Microemulsion Systems Based on a C8/10 Alkyl Polyglucoside: A Reentrant Phase Inversion Induced by Alcohols?, Progr. Colloid Polym. Sci. 111, 92–99 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0118116

- G. Rother and G.H. Findenegg. Monolayer Films of PEO-b-PS Block Copolymers at the air/Water and an oil/Water Interface, Colloid Polym. Sci. 276, 496–502 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s003960050271

- P. Lang, C. Braun, R. Steitz, G.H. Findenegg and H. Rhan. Surface Relaxation of a Hexagonal Lyotropic Mesophase, J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 7590–7595 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp981756b

- A. Möller, P. Lang, G.H. Findenegg and U. Keiderling. Location of Butanol in Mixed Micelles with Alkyl Glucosides Studied by SANS, J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 8958–8964 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp981819q

- C. Stubenrauch and G.H. Findenegg. Microemulsions Supported by Octyl Monoglucoside and Geraniol. 2. A NMR Self-Diffusion Study of the Microstructure, Langmuir. 14, 6005–6012 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la9804637

- R. Steitz, C. Braun, J. Bowers, P. Lang and G.H. Findenegg. Surface Effects Accompanying the L(-to-L(+ Transition of the Amphiphile C12E4 in Water as Studied by Neutron Reflectivity, Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 102, 1615–1619 (1998). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bbpc.19981021121

- G.H. Findenegg, C. Braun, P. Lang, and R. Steitz. Interfacial Effects of Dilute Solutions and Lyotropic Liquid Crystalline Phases of Nonionic Surfactants, in: Supramolecular Structure in Confined Geometries, edited by S. Manne, and G.G. Warr, ACS Symposium Series No. 736, pp. 24–39 (1999)

- S. Uredat and G.H. Findenegg. Domain Formation in Gibbs Monolayers at oil/Water Interfaces, Langmuir. 15, 1108–1112 (1999). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la981264q

- U. Menge, P. Lang and G.H. Findenegg. From oil-Swollen Wormlike Micelles to Microemulsion Droplets: A Static Light Scattering Study of the L1 Phase in the System Water + C12E5 + Decane, J. Phys. Chem. B. 103, 5768–5774 (1999). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp990130y

- E.H.A. de Hoog, H.N.W. Lekkerkerker, J. Schulz and G.H. Findenegg. Ellipsometric Study of the L/L Interface in Phase Separated Colloid–Polymer Suspension, J. Phys. Chem. B. 103, 10657–10660 (1999). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9921607

- U. Menge, P. Lang and G.H. Findenegg. Influence of Temperature and oil-to-Surfactant Ratio on Micellar Growth in Aqueous Solutions of C12E5 with Decane, Colloids Surf. A. 163, 81–90 (2000). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(99)00433-1

- R. Sedev, D. Exerowa and G.H. Findenegg. PEO-PPO-PEO Triblock Copolymers at the Water/air Interface and in Foam Films, Colloid Polym. Sci. 278, 119–123 (2000). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s003960050020

- Z. Király and G.H. Findenegg. Calorimetric Study of the Adsorption of Short-Chain Nonionic Surfactants on Silica Glass and Graphite: Dimethyldecylamine Oxide and Octyl Monoglucoside, Langmuir. 16, 8842–8849 (2000). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la000065f

- R. Lucht, P. Marczuk, C. Bahr and G.H. Findenegg. X-ray Reflectivity Study of Smectic Wetting and Prewetting at the Free Surface of Isotropic Liquid Crystals, Phys. Rev. E. 63, 1704–1708 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.63.041704

- A. Schreiber, I. Ketelsen and G.H. Findenegg. Melting and Freezing of Water in the Pore Space of Ordered Mesoporous Silica Materials, Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys. 3, 1185–1195 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b010086m

- Z. Király, G.H. Findenegg, E. Klumpp, H. Schlimper and I. Dékány. Adsorption Calorimetric Study of the Organization of Sodium n-Decyl Sulfate at the Graphite/Solution Interface, Langmuir. 17, 2420–2425 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la001552y

- J.R. Howse, R. Steitz, M. Pannek, P. Simon, D.W. Schubert and G.H. Findenegg. Adsorbed Surfactant Layers at Polymer/Liquid Interfaces. A Neutron Reflectivity Study, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 3, 4044–4051 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b101517f

- J. Schulz, J. Bowers and G.H. Findenegg. Crossover from Preferential Adsorption to Depletion: Aqueous Systems of Short-Chain CnEm Amphiphiles at Liquid/Liquid Interfaces, J. Phys. Chem. B. 105, 6956–6964 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp010616q

- G.H. Findenegg, J. Schulz, and S. Uredat. Structure of Liquid/Liquid Interfaces Studied by Ellipsometry and Brewster Angle Microscopy, in Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, Vol. 132, edited by Y. Iwasawa, N. Oyama, and H. Kunieda, pp. 1–14 (2001); ISBN 0-444-50651-9

- E. Gedat, A. Schreiber, G.H. Findenegg, I. Shenderovich, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky. Stray Field Gradient NMR Reveals Effects of Hydrogen Bonding on Diffusion Coefficients of Pyridine in Mesoporous Silica, Magnet. Resonance Chem. 39, S149–S157 (2001). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.932

- E. Gedat, A. Schreiber, J. Albrecht, T. Emmler, I. Shenderovich, G.H. Findenegg, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky. 2H-Solid State NMR Study of Benzene-d6 Confined in Mesoporous Silica SBA-15, J. Phys. Chem. B. 106, 1977–1984 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp012391p

- A. Schreiber, H. Bock, M. Schoen and G.H. Findenegg. Effect of Surface Modification on the Pore Condensation of Fluids. Experimental Results and Density-Functional Theory, Mol. Phys. 100, 2097–2107 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00268970210132559

- R. Sedev, R. Steitz and G.H. Findenegg. The Structure of PEO-PPO-PEO Triblock Copolymers at the Water/air Interface, Phys. B. 315, 267–272 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-4526(02)00513-6

- J.R. Howse, E. Manzanares, I.A. McLure, J. Bowers, R. Steitz and G.H. Findenegg. Critical Adsorption and Boundary Layer Structure of 2-Butoxyethanol + D2O Mixtures at a Hydrophilic Silica Surface, J. Chem. Phys. 116, 7177–7188 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1463398

- M. Drach, J. Narkiewicz-Michalek, W. Rudzinski, G.H. Findenegg and Z. Király. Calorimetric Study of Adsorption of non-Ionic Surfactants on Silica gel: Estimating the Role of Lateral Interactions Between Surface Aggregates, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4, 2307–2319 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b200357k

- P. Marczuk, P. Lang, S.K. Mehta and G.H. Findenegg. Gibbs Films of Semi-Fluorinated Alkanes at the Surface of Alkane Solutions, Langmuir. 18, 6830–6838 (2002). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la025596d

- A. Schreiber, S. Reinhardt, and G.H. Findenegg. The Lower Closure Point of the Adsorption Hysteresis Loop of Fluids in Mesoporous Silica Materials, in Characterization of Porous Solids VI, edited by F. Rodriguez-Reinoso, B. McEnaney, J. Rouquerol and K. Unger, Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis 144 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2002), pp. 177–184; ISBN 0-444-51261-6.

- U. Menge, P. Lang, G.H. Findenegg and P. Strunz. Structural Changes of oil-Swollen Cylindrical Micelles of C12E5 in Water Studied by SANS, J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 1316–1320 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp021797e

- T. Fütterer, T. Hellweg, G.H. Findenegg, J. Frahn, A.D. Schlüter and C. Böttcher. Self-assembly of Amphiphilic Poly(Paraphenylene)s: Thermotropic Phases, Solution Behavior, and Monolayer Films, Langmuir. 19, 6537–6544 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la026409e

- R. Steitz, T. Gutberlet, T. Hauss, B. Klösgen, R. Krastev, S. Schemmel, A.C. Simonsen and G.H. Findenegg. Nanobubbles and Their Precursor Layer at the Interface of Water Against a Hydrophobic Substrate, Langmuir. 19, 2409–2418 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la026731p

- I. Shenderovich, G. Buntkowsky, A. Schreiber, E. Gedat, S. Sharif, J. Albrecht, N.S. Golubev, G.H. Findenegg and H.-H. Limbach. Pyridine-15N – A Mobile NMR Sensor for Surface Acidity and Surface Defects of Mesoporous Silica, J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 11924–11939 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0349740

- T. Fütterer, T. Hellweg, and G.H. Findenegg. Particle Characterization by Scattering Methods in Systems Containing Different Types of Aggregates: Aggregation of an Amphiphilic Substituted Poly(paraphenylene) in Micellar Surfactant Solutions. In: “Mesoscale Phenomena in Fluid Systems”, edited by F. Case and P. Alexandridis, ACS Symposium Series, No. 861, chap. 8 (2003).

- U. Voigt, W. Jaeger, G.H. Findenegg and R. von Klitzing. Charge Effects on the Formation of Multilayers Containing Strong Polyelectrolytes, J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 5273–5280 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0256488

- T. Hellweg, S. Schemmel, G. Rother, A. Brûlet, H. Eckerlebe and G.H. Findenegg. De-mixing Dynamics of a Binary Liquid System in a Controlled-Pore Glass. A Neutron Spin-Echo Spectroscopy and Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Study, Eur. Phys. J. E. 12, S1–S4 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1140/epjed/e2003-01-001-9

- A. Nordskog, H. Egger, G.H. Findenegg, T. Hellweg, H. Schlaad, H. von Berlepsch and C. Böttcher. Structural Changes of Poly(Butadiene)-Poly(Ethyleneoxide) Diblock-Copolymer Micelles Induced by a Cationic Surfactant: Scattering and Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy Studies, Phys. Rev. E. 68 (011406), 1–14 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011406

- Y. Qiao, M. Schönhoff and G.H. Findenegg. 2H NMR Investigation of the Structure and Dynamics of the Nonionic Surfactant C12E5 Confined in Controlled-Pore Glass, Langmuir. 19, 6160–6167 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la034471l

- H. Egger, T. Hellweg and G.H. Findenegg. Structure and Elastic Properties of Block Copolymer Bilayers Doped with a Cationic Surfactant, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 5, 3013–3020 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b304555b

- Z. Király and G.H. Findenegg. Mastalir: Chain-Length Anomaly in the two-Dimensional Ordering of the Cationic Surfactants CnTAB at the Graphite/Water Interface Revealed by Advanced Calorimetric Methods, J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 12492–12496 (2003). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp035466t

- G. Rother, D. Woywod, M. Schoen and G.H. Findenegg. Confinement Effect on the Adsorption of a Binary Liquid Mixture in Pores Near Liquid/Liquid Phase Separation, J. Chem. Phys. 120, 11864–11873 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1755667

- H.W. Shi, S. Zhang, R. Steitz, J. Chen, S. Uredat and G.H. Findenegg. Surface Coatings of PEO-PPO-PEO Block Copolymers on Native and Polystyrene-Coated Silicon Wafers, Colloids Surf. A. 246, 81–89 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2004.07.019

- B. Grünberg, T. Emmler, E. Gedat, I. Shenderovich, G.H. Findenegg, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky.: Hydrogen Bonding of Water Confined in Mesoporous Silica MCM-41 and SBA-15 Studied by 1H Solid-State NMR, Chem. Eur. J. 10, 5689–5696 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200400351

- T. Fütterer, A. Nordskog, T. Hellweg, G.H. Findenegg, S. Förster and C. Dewhurst. Characterization of Polybutadiene-Poly(Ethyleneoxide) Aggregates in Aqueous Solutions: A Light- and Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Study, Phys. Rev. E. 70, 041408 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.70.041408

- R. Steitz, P. Müller-Buschbaum, S. Schemmel, R. Cubitt and G.H. Findenegg. Lateral Structure of a Surfactant Adsorbed Layer at a Hydrophilic Solid/Liquid Interface, Europhys. Lett. 67, 962–968 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2004-10135-4

- W. Masierak, T. Emmler, E. Gedat, A. Schreiber, G.H. Findenegg and G. Buntkowsky. Microcrystallization of Benzene-d6 in Mesoporous Silica Revealed by 2H-Solid-State NMR, J. Phys. Chem. B. 108, 18890–18896 (2004). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp047348r

- S. Schemmel, D. Akcakayiran, G. Rother, A. Brûlet, T. Hellweg and G.H. Findenegg. Phase-separation of a Binary Liquid System in Controlled-Pore Glass, Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 790, P 7.2.1 (2004).

- R. Steitz, S. Schemmel, H.W. Shi and G.H. Findenegg. Boundary Layers of Aqueous Surfactant and Block Copolymer Solutions Against Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Solid Surfaces, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 17, S665–S683 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/17/9/023

- D. Woywod, S. Schemmel, G. Rother, G.H. Findenegg and M. Schoen. Phase Behaviour and Local Structure of a Binary Mixture in Pores: Mean-Field Lattice Model Calculations for Analyzing Neutron Scattering Data, J. Chem. Phys. 122, 124510 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1867372

- T. Fütterer, T. Hellweg, G.H. Findenegg, J. Frahn and A.D. Schlüter. Aggregation of an Amphiphilic Poly(p-Phenylene) in Micellar Surfactant Solutions. Static and Dynamic Light Scattering, Macromolecules. 38, 7443–7450 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/ma050318h

- T. Fütterer, T. Hellweg, G.H. Findenegg, J. Frahn and A.D. Schlüter. Aggregation of an Amphiphilic Poly(p-Phenylene) in Micellar Surfactant Solutions. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering, Macromolecules. 38, 7451–7455 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/ma050323l

- Z. Király and G.H. Findenegg. Pulsed-flow Microcalorimetric Study of the Template-Monolayer Region of Nonionic Surfactants Adsorbed at the Graphite/Water Interface, Langmuir. 21, 5047–5054 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la047006c

- K. Ciunel, M. Armélin, G.H. Findenegg and R. von Klitzing. Evidence of Surface Charge at the air/Water Interface from Thin-Film Studies on Polyelectrolyte-Coated Substrates, Langmuir. 21, 4790–4793 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la050328b

- S. Schemmel, G. Rother, H. Eckerlebe and G.H. Findenegg. Local Structures of a Phase-Separating Binary Mixture in a Mesoporous Glass Matrix Studied by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering, J. Chem. Phys. 122, 244718 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1931528

- D. Akcakayiran, D.G. Kurth, S. Röhrs, G. Rupprechter and G.H. Findenegg. Self-assembly of a Metallo-Supramolecular Coordination Polyelectrolyte in the Pores of SBA-15 and MCM-41 Silica, Langmuir. 21, 7501–7506 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la050230x

- T. Hofmann, D. Wallacher, P. Huber, R. Birringer, K. Knorr, A. Schreiber and G.H. Findenegg. Small-angle x-ray Diffraction of Kr in Mesoporous Silica: Effects of Microporosity and Surface Roughness, Phys. Rev. B. 72, 064122 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.064122

- A. Vyalikh, T. Emmler, E. Gedat, I. Shenderovich, G.H. Findenegg, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky. Evidence of Microphase Separation in Controlled Pore Glasses, Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 28, 117–124 (2005). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssnmr.2005.07.001

- A. Schreiber, I. Ketelsen, G.H. Findenegg, and E. Hoinkis. Thickness of Adsorbed Nitrogen Films in SBA-15 Silica from Small-Angle Neutron Diffraction, in Characterization of Porous Solids Vol. VII, edited by P.L. Llewellyn, J. Rouquerol, F. Rodrigues-Reinoso, and N.A. Seaton, pp. 17–24 (2006); ISBN 0-444-52022-8

- Z. Kiraly, G.H. Findenegg and À Mastalir. Adsorption of Dodecyltrimethylammonium Bromide and Sodium Bromide on Gold Studied by Liquid Chromatography and Flow Adsorption Calorimetry, Langmuir. 22, 3207–3213 (2006). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/la053184+

- G.A. Zickler, S. Jähnert, W. Wagermaier, S. Funari, G.H. Findenegg and O. Paris. Physisorbed Films in Periodic Mesoporous Silica Studied by in-Situ Synchrotron Small-Angle Diffraction, Phys. Rev. B. 73, 184109 (2006). doi:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.73.184109

- T. Shin, G.H. Findenegg and A. Brandt. Surfactant Adsorption in Ordered Mesoporous Silica Studied by SANS, Progr. Colloid Polymer Sci. 133, 116–122 (2006). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-32702-9_19

- E. Liu, J.C. Dore, J.B.W. Webber, D. Kushalini, S. Jähnert, G.H. Findenegg and T. Hansen. Neutron Diffraction and NMR Relaxation Studies of Structural Variation and Phase Transformations for Water/ice in SBA-15 Silica, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 18, 10009–10028 (2006). doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/18/44/003

- Z. Király, Á Mastalir, Á Császár, H. Demir, D. Uner and G.H. Findenegg. Liquid Chromatography as a Novel Method for Determination of the Dispersion of Supported Pd Particles, J. Catal. 245, 265–269 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2006.10.016

- G.A. Zickler, S. Jähnert, S. Funari, G.H. Findenegg and O. Paris. Pore Lattice Deformation in Ordered Mesoporous Silica Studied by in-Situ Small-Angle x-ray Diffraction, J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, s522–s526 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889806055968

- A. Vyalikh, T. Emmler, B. Grünberg, Y. Xu, I. Shenderovich, G.H. Findenegg, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky. Hydrogen Bonding of Water Confined in Controlled-Pore Glass 10-75 Studied by 1H-Solid State NMR, Z. Phys. Chem. 221, 155–168 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1524/zpch.2007.221.1.155

- G.H. Findenegg and A.Y. Eltekov.: Adsorption Isotherms of Nonionic Surfactants in SBA-15 Measured by Micro-Column Chromatography, J. Chromatogr. A. 1150 (1-2), 236–240 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2007.01.073

- A. Vyalikh, T. Emmler, I. Shenderovich, G.H. Findenegg, H.-H. Limbach and G. Buntkowsky. 2H-solid State NMR and DSC Study of Isobutyric Acid in Mesoporous Silica Materials, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 2249–2257 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b617744a

- K. Hänni-Ciunel, G.H. Findenegg and R. von Klitzing. Water Contact Angle on Polyelectrolyte-Coated Surfaces: Effect of Film Swelling and Droplet Evaporation, Soft. Mater. 5, 61–73 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15394450701554452

- G. Buntkowsky, H. Breitzke, A. Adamczyk, F. Roelofs, T. Emmler, E. Gedat, B. Grünberg, Y. Xu, H.-H. Limbach, I. Shenderovich, A. Vyalikh and G.H. Findenegg. Structural and Dynamical Properties of Guest Molecules Confined in Mesoporous Silica Materials Revealed by NMR, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 4843–4853 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b707322d

- I.G. Shenderovich, D. Mauder, D. Akcakayiran, G. Buntkowsky, H.-H. Limbach and G.H. Findenegg. NMR Provides Checklist of Generic Properties for Atomic-Scale Models of Periodic Mesoporous Silicas, J. Phys. Chem. B. 111, 12088–12096 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp073682m

- O. Dietsch, A. Eltekov, H. Bock, K.E. Gubbins and G.H. Findenegg. Crossover from Normal to Inverse Temperature Dependence of the Adsorption of Nonionic Surfactants at Hydrophilic Surfaces and Pore Walls, J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 16045–16054 (2007). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0747656

- J. Seyed-Yazdi, H. Farman, J.C. Dore, J.B.W. Webber, G.H. Findenegg and T. Hansen. Structural Characterization of Water and ice in Mesoporous SBA-15 Silicas. 2: The ‘Almost-Filled’ Case for 86 Å Pore Diameter, J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 20, 205107 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/20/205107

- J. Seyed-Yazdi, H. Farman, J.C. Dore, J.B.W. Webber and G.H. Findenegg. Structural Characterization of Water/ice Formation in SBA-15 Silicas. 3: The Triplet Profile for 86 Å Pore Diameter, J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 20, 205108 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/20/205108

- D. Akcakayiran, D. Mauder, C. Hess, T.K. Sievers, D.G. Kurth, I. Shenderovich, H.-H. Limbach and G.H. Findenegg. Carboxylic Acid Doped SBA-15 Silica as a Host for Metallo-Supramolecular Coordination Polymers, J. Phys. Chem. B. 112, 14637–14647 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp804712w

- S. Jähnert, F. Vaca Chávez, G.E. Schaumann, A. Schreiber, M. Schönhoff and G.H. Findenegg. Melting and Freezing of Water in Cylindrical Silica Nanopores, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6039–6051 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b809438c

- G.H. Findenegg, S. Jähnert, D. Akcakayiran and A. Schreiber. Freezing and Melting of Water Confined in Silica Nanopores, ChemPhysChem. 9, 2651–2659 (2008). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.200800616

- S. Jähnert, D. Müter, J. Prass, G.A. Zickler, O. Paris and G.H. Findenegg. Pore Structure and Fluid Sorption in Ordered Mesoporous Silica. I. Experimental Study by in-Situ Small-Angle X-ray Scattering, J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 15201–15210 (2009). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp8100392

- D. Müter, S. Jähnert, J.W.C. Dunlop, G.H. Findenegg and O. Paris. Pore Structure and Fluid Adsorption in Ordered Mesoporous Silica. II. Modeling, J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 15211–15217 (2009). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp810040k

- D. Lugo, J. Oberdisse, M. Karg, R. Schweins and G.H. Findenegg. Surface Aggregate Structure of Nonionic Surfactants on Silica Nanoparticles, Soft Matter. 5, 2928–2936 (2009). doi:https://doi.org/10.1039/b903024g

- D. Mauder, D. Akcakayiran, S.B. Lesnichin, G.H. Findenegg and I.G. Shenderovich. Acidity of Sulfonic and Phosphonic Acid-Functionalized SBA-15 Under Almost Water-Free Conditions, J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 19185–19192 (2009). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jp907058y

- G.H. Findenegg, S. Jähnert, D. Müter and O. Paris. Analysis of Pore Structure and gas Adsorption in Periodic Mesoporous Solids by in-Situ Small-Angle X-ray Scattering, Colloids Surf. A. 357, 3–10 (2010). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.09.053