Each year in early November in Robbins Hall at University of California (UC) Davis, Dr. Kenneth Wells, wearing a white shirt, tie and jacket (), chalk in hand, and book of illustrated notes lying open on the desk, lectured to his 48-student mycology class. He presented clear and well-paced explanations of development in fungi from chytrids to basidiomycetes as well as oomycetes and slime molds. Ken was precise; although students were required to know the names of genera, and not species, his examples always were of individual species, and he was loath to generalize even among related taxa. The high point for Ken came when he discussed repeating spores of Helicogloea or mating systems in Exidia. He told us that these jelly fungi had been good to his family before he sent us into lab to tear them apart. To us, this seemed like a remarkable statement, as jelly fungi are not the most charismatic of organisms.

Students in mycology class weren’t the only ones who must have wondered about Ken‘s research focus on jelly fungi. In 1955, Lindsay Olive was landed with one of Wisconsin state senator William Proxmire’s Golden Fleece awards for wasteful government spending on his sabbatical project, “The jelly fungi of the Society Islands” (Mycologia 81:497).Footnote1 Jelly fungi are mostly not edible, not toxic, not (with the notable exception of Cryptococcus) destructive of human lives or property, and many spend most of their time as almost invisible gelatinous crusts under or on dead wood.

However, the jelly fungi were indeed good to Ken and his family. He studied them through his 34 years as a professor in the Department of Botany at the University of California, Davis, from 1957 to 1991. During this time, the department moved from a converted garage and an old house without decent facilities to Robbins Hall to become one of the strongest botany departments in the world, a rise paralleled by Davis’ Department of Plant Pathology as it, too, expanded in size and renown. Together, they provided remarkable strength in mycology.

Over the years, Ken’s research was well funded by US National Science Foundation (NSF) grants, which let him correspond, collaborate, and conduct field studies throughout the world. Among collaborators who found the jelly fungi equally compelling were Canada’s Bob Bandoni, Germany’s Franz Oberwinkler, and Estonia‘s Ain Raitviir. Jelly fungi even took him on a sabbatical to Romania, where he was allowed to receive Raitviir and work on Russian material. NSF was not his only source of funding; the Fulbright Foundation supported him as a research scholar in Brazil from 1963 to 1964, and he was a grantee at the University of Tübingen, Germany in 1983–1984.

The charm of the jelly fungi lies in their microscopic characters. Mushrooms may be large and glamorous, but at the microscopic level these charismatic fungi settled on producing holobasidia, boring and uniform structures for reproduction. Jelly fungi adventured more widely, developing considerable diversity in microscopic form and function and providing clues to the patterns of early evolution among Basidiomycota. Throughout Ken’s career, microscopy was the key to their study.

When Ken began at Davis in 1957, startup funding had yet to be invented, but his department gave him a microscope. In 1975, he had grant funding to buy a better Zeiss microscope, and about 10 years later he upgraded again to a very fine Zeiss photomicroscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) and phase-contrast optics, which he kept in pristine shape in his office. He spent many a Saturday afternoon in a flannel shirt, with the beginnings of what would now be a highly fashionable beard, examining specimens.

Outside of the jelly fungi, electron microscopy came to UC Davis in the 1960s, and Ken’s colleague, T. Elliot Weier, helped him get started in the art of preparing material for ultrastructural studies. This knowledge launched Ken into a series of pioneering studies of ascus development in Ascobolus stercorarius and basidium development in Schizophyllum commune and Pholiota terrestris. Ken’s adoption of a new technique, electron microscopy, to study fungal evolution was not lost on his students, several of whom adopted another new technique, DNA analysis, to further their studies of fungal evolution.

Three wars played roles in Ken’s becoming a mycologist. He was born in Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1927. Ken’s father had fought in the First World War, caught influenza in 1918, never fully regained his health and died in 1 930 when Ken was 3 years old. His family then moved to Gray’s Branch, Kentucky, living on an acre of land that was a gift from Ken’s grandfather. Working on his grandfather’s farm, Ken grew up absorbing an interest in plants and botany.

Toward the end of the Second World War in 1945, Ken graduated from high school and, encouraged by his mother, he joined the navy to avoid the hardships his father experienced in the infantry during World War I. Things turned out better than expected; the war with Germany ended before Ken joined, and the war with Japan ended when he was in boot camp. He was posted to a water pumping station in a small town on the island of Samar in the Philippines until his discharge in 1946, a posting that let Ken develop an interest in tropical botany and qualify for entry to the University of Kentucky through the GI Bill (Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944).

The GI Bill offered an amazing opportunity for further education to people who would otherwise never have considered more schooling. US universities in 1946 dreaded the influx of GI Bill–sponsored slackers—young men and women from nonacademic backgrounds who barely passed high school and were about to lower their standards of excellence. Surprisingly, those serious and mature veterans turned to be the best class of students ever. Sadly, it took a world war to create unprecedented social mobility by unlocking the hidden potential of what had been poorly motivated high schoolers. Ken was not the only mycologist of his generation to benefit from the GI Bill, among them Robert Gilbertson, Howard Bigelow, and Emory Simmons.

Starting at the University of Kentucky, Ken was told he had to have a major field of study. He had never heard of a major before but decided to go into agronomy to become a farm advisor. He joined the US Army Reserve Officer Training Corps, like many college students of his generation in need of financial assistance. His life then took an unusual turn when he found himself fascinated by fungal life cycles during a botany course taught by plant pathologist Frank T. McFarland. Ken decided to become a mycologist. He was an excellent student and was elected to the honor society Phi Beta Kappa in 1950. Encouraged by McFarland, he then started graduate school in mycology at Purdue University.

The third war to impact Ken’s life was the Korean War, which also began in 1950. In March 1951, Ken, as a member of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), was called up to serve, this time in the army. Again, he was fortunate; he was posted to Munich, Germany. There he met, wooed, and married Ellinor Kirschner, a bright outgoing artist who was as outspoken as Ken was restrained. Ellinor drew illustrations for several of Ken’s publications and developed an aptitude for laboratory work, helping Ken in the laboratory by performing many of the crossing experiments that supported the description of some eight new Exidia species. Ellinor also served Ken and his students by translating, from German to English, Manfred Girbardt’s seminal work on light and electron microscopy of fungal nuclear behavior. Outside the laboratory, Ken and Ellinor raised two children, Henry and Heidi, and later, enjoyed the grandchildren, Henry’s Carly and Sam, and Heidi’s Graydon.

Upon discharge in 1954, Ken restarted graduate school, not at Purdue but under G. W. Martin at the University of Iowa. He completed a thesis on systematics of four genera of jelly fungi in August 1957 and started applying for jobs. In those days, landing a faculty position involved a telephone call between someone looking to hire and a few of their academic friends with graduate students ready to finish. Martin had just retired, but C. J. Alexopoulos had been hired as a new Iowan mycologist, and Dr. Alex mentioned Ken when asked for a graduating student for a position at UC Davis. Ken applied and was UC Davis’ second choice, getting the job when the graduate from Harvard, who was first, declined due to lack of research facilities. We two are deeply indebted to that foolish Harvard graduate.

Ken’s experiences in the military and the university gave him an insightful view of bureaucracy. Although a diligent and effective instructor, he advised us that being fourth author on a minor publication would count more toward promotion than winning a teaching award. He also recounted his brief stint in the Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps, when, as he was walking to trial, the judge told him that it was time to “Get it over and let us give the guilty bastard a fair trial.” Cynical or not, Ken did more than his share for the common good, serving as chair of the UC Davis Department of Botany for 5 years and hosting the joint American Institute of Biological Sciences–Mycological Society of America (AIBS-MSA) annual meeting at Davis in 1988.

We began with Ken in his classroom, lecturing on mycology as he did each fall quarter to students in the Departments of Botany and Plant Pathology, but he was more at home in the field than behind a lectern. In 1974, to give Davis students a taste of field mycology, Ken joined with Harry Thiers (then at San Francisco State University) to lead classes from both campuses on a weekend-long field trip to the wet California coast (). What is now the annual Mendocino Foray expanded to include Berkeley in the 1980s and now comprises those three schools along with California State Universities at East Bay and Fresno, as well as Stanford University. Ken also cared about graduate education and co-taught, with his plant pathologist colleague, Ed Butler, graduate seminars on mycology each spring and fall quarters. These lunch time events were as supremely entertaining as they were instructive because Butler never hesitated to question or comment on every aspect of the student’s presentation while Wells strove to keep the talk on track. Ken’s most lasting graduate teaching was the mentoring of students, and here his thoughtful approach was as deeply appreciated by his students as it was admired by those of others. Ken let one of us pursue a much loved but dead-end project on ectomycorrhizae for a year before suggesting that we switch to a well-funded one on nuclear division in basidiomycetes; never was better advice given or received.

We noted at the outset Ken’s devotion to the jelly fungi. Once, we overheard a conversation between him and a fellow graduate student in which Ken said, “I love the jelly fungi,” to which he quickly added, “Well, like, not love.” Afterward, in conversation with the student, it was agreed that Ken did, in fact, love those fungi. Among Ken’s publications, one stands out, “Jelly Fungi, Then and Now!” (1994, Mycologia 86:18-48), a thorough, beautifully illustrated, and superbly organized review of the field presented as the Annual (now the Karling) Mycological Society of America Lecture of 1992, one of the very few times that an MSA member has been so honored.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (4.3 MB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ellinor K. Wells and to Heidi Booth (née Wells) for providing background information, including a link to a University of California, Davis, video interview with Ken: https://video.ucdavis.edu/media/Kenneth+Wells/0_g9srqz54/25823622, and for reviewing a near-final draft of this memorial. Meredith Blackwell provided insightful reviews as well as the unpublished autobiography that Ken had written when an MSA travel award in his name was first established (SUPPLEMENTARY FIG. 1). We thank Meredith for the strategic reminders that encouraged us to reflect on the life and times of a man whom we appreciated and admired.

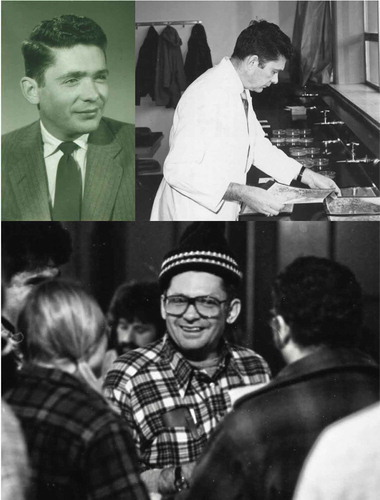

Figure 1. Clockwise from upper left: Ken Wells photographed in the 1950s, Wells developing electron micrographs in the 1960s and Wells regaling students in 1977 on the Mendocino Foray, which he and Harry Thiers at San Francisco State University initiated in the 1970s and which has grown to include UC Berkeley, Stanford University, California State University, East Bay, and California State University, Fresno. Photos from 1950s and 1960s provided by Heidi and Ellinor Wells, photo from 1977 by J. Taylor.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s Web site.

Notes

1 How times have changed; the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) now sponsors the Golden Goose Awards, which “…recognize the tremendous human and economic benefits of federally funded research by highlighting examples of seemingly obscure studies that have led to major breakthroughs and resulted in significant societal impact.” In fact, in 2017, Joyce Longcore won a Golden Goose Award for her systematic work on Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, the chytrid responsible for amphibian decline.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bandoni R, Oberwinkler F, Wells K. 1982. Studies in Heterobasidiomycetes. 19. On the poroid genera of the Tremellaceae. Canadian Journal of Botany–Revue Canadienne De Botanique 60:998–1003.

- Wells K. 1964. Basidia of Exidia nucleata. I. Ultrastructure. Mycologia 56:327–341.

- Wells K. 1965. Ultrastructural features of developing and mature basidia and basidiospores of Schizophyllum commune. Mycologia 57:236–261.

- Wells K. 1970. Light and electron microscopic studies of Ascobolus stercorarius. I. Nuclear divisions in the ascus. Mycologia 62:761–790.

- Wells K. 1978. The fine structure of septal pore apparatus in the lamellae of Pholiota terrestris. Canadian Journal of Botany–Revue Canadienne De Botanique 56:2915–2924.

- Wells K. 1994. Jelly fungi, then and now! Mycologia 86:18–48.

- Wells K, Bandoni RJ. 1985. Interfertility and comparative morphological studies of Tremella mesenterica. Mycologia 77:36–49.

- Wells K, Bandoni RJ. 2001. Heterobasidiomycetes. In: McLaughlin D, McLaughlin E, Lemke P, eds. The Mycota VII Part B. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. p. 85–120.

- Wells K, Oberwinkler F. 1982. Tremelloscypha gelatinosa, a species of a new family Sebacinaceae. Mycologia 74:325–331.

- Wells K, Raitviir A. 1977. The species of Exidiopsis (Tremellaceae) of the USSR. Mycologia 69:987–1007.

- Wells K, Wells EK, eds. 1982. Basidium and basidiocarp: evolution, cytology, function, and development. New York: Springer. XI, 188 p.

Student work supervised by K. Wells

- Berbee ML, Wells K. 1988. Ultrastructural studies of mitosis and the septal pore apparatus in Tremella globospora. Mycologia 80:479–492.

- Berbee ML, Wells K. 1989. Light and electron microscopic studies of meiosis and basidium ontogeny in Clavicorona pyxidata. Mycologia 81:20–41.

- Digby S, Wells K. 1989. Compatibility and development in Ustilago cynodontis. Mycologia 81:595–607.

- Gaboury GE. 1977. Ontogeny of the ascus in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: observations of flat embedded material with the light and electron microscopes [PhD dissertation]. Davis, California: University of California, Davis. 255 p.

- Hanson LC, Wells K. 1991. Characterization of three Tremella species by isozyme analysis. Mycologia 83:446–454.

- Hung CY, Wells K. 1971. Light and electron microscopic studies of crozier development in Pyronema domesticum. Journal of General Microbiology 66:15–27.

- Prusso DC, Wells K. 1967. Sporobolomyces roseus. I. Ultrastructure. Mycologia 59:337–348.

- Sundberg WJ. 1971. A study of basidial ontogeny and meiosis in Schizophyllum commune utilizing light and electron microscopy [PhD dissertation]. Davis, California: University of California, Davis. 156 p.

- Taylor JW, Wells K. 1979. A light and electron microscopic study of mitosis in Bullera alba and the histochemistry of some cytoplasmic substances. Protoplasma 98: 31–62.

- Wong GJ, Wells K, Bandoni RJ. 1985. Interfertility and comparative morphological studies of Tremella mesenterica. Mycologia 77:36–49.

- Wongsthientong S. 1971. Some nutritional and environmental factors controlling basidiocarp formation in Pholiota marginata [MSc dissertation]. Davis, California: University of California, Davis. 67 p.