Robert L. Shaffer, known to his friends as Bob, was a very private, modest, reserved person, who had a commanding knowledge of fungi and exemplified careful competence in all his work. He was born in Long Beach, California, on 29 December 1929. Within a few months of his birth his family moved to Kinsley, Kansas, where he spent his childhood. He received BS and MS degrees from Kansas State College (now Kansas State University) at Manhattan in 1951 and 1952, respectively. His academic interest in fungi was first evidenced in his MS degree with Clark Rogerson that resulted in a coauthored note on Kansas macrofungi (Shaffer and Rogerson Citation1952). From Kansas he moved to New York to attend Cornell where completed his PhD in 1955, working with Richard Korf.

After receiving his doctorate, Bob taught at the University of Chicago from 1955 to 1960 and was hired at the University of Michigan as an assistant professor of botany and curator of fungi for the University of Michigan Herbarium in 1960. Three years later he was promoted to associate professor, and in 1970 he was promoted to full professor. He served as the director of the herbarium for 11 years from 1975 through 1986, and he helped modernize that facility through grants that he authored. In 1982 he was appointed as the first Lewis E. Wehmeyer and Elaine Prince Wehmeyer Professor of Fungal Taxonomy, a position he continued to hold for many years even after his retirement in 1993 (Anonymous Citation2022). Bob served the Mycological Society of America at several levels. He was on the council from 1963 to 1965, served as Secretary-Treasurer from 1968 to 1971, and was President from 1973 to 1974. In addition, he interacted with the North American Mycological Association (NAMA), the premiere amateur mycological society. NAMA recognized Bob for “Contributions to Amateur Mycology,” an award that has only been bestowed on a handful of other professional mycologists.

Bob’s research was in mushroom taxonomy. His earliest published work was on Volvariella, which was a relatively small, seemingly well-defined genus, at least in pre-molecular days. His PhD dissertation was the start of his work on this genus, and he continued with it for several years afterward while at Chicago and after starting at Michigan (Shaffer Citation1957, Citation1962a).

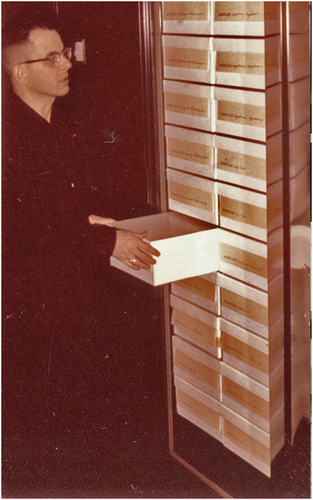

The genus Russula became the focus of his taxonomic work for most of his career. This is a very large, well-defined genus in which species delimitation is exceedingly difficult. In 1965, near the beginning of his work on the genus, Bob took a sabbatical to work in France with Henri Romagnesi (), who was well known for his work on Russula. This interaction likely helped Bob understand European species concepts, and it was also a highly enjoyable interaction that he spoke about glowingly for his whole career. His work on Russula continued for the next several decades, and anyone who visited his herbarium office was likely to find him at the microscope with Russula collections, and notes spread out neatly around him (). His published output on the genus was modest, but to put this in perspective it was almost the only taxonomic work on North American Russula species during that period. The reasons for slow progress on the genus are now clear: the number of species is huge, the differences between them are often subtle, and many of the most obvious features that one might use to separate species are unreliable (Bazzicalupo et al Citation2017). Add these factors to the fact that molecular tools and widespread color imagery were not yet available, and one begins to understand how difficult it was to make taxonomic progress in this genus. Yet he persisted and made lasting contributions at a time when no one else was doing so, and ultimately described 22 species, varieties, or forms of Russula. These include some of our most common North American species, such as Russula silvicola, Russula cerolens, and Russula dissimulans (Homola and Shaffer Citation1975; Shaffer Citation1962b, Citation1964, Citation1970, Citation1972, Citation1975, Citation1989, Citation1990). Even long after his retirement in 1993, Bob continued his interest in fungal phylogeny, when he participated in taxon sampling at the Deep Hypha meeting in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2002.

Figure 1. On sabbatical in France 1965, Bob Shaffer (center with basket), Jocelyn, and Martha. Shaffer to right. Henri Romagnesi seated fourth from left. Courtesy of Martha Nobunaga.

Teaching was an equally important part of Bob’s career, and he taught at many levels. At the undergraduate level, he taught introductory courses in botany, and Introductory Mycology. His course on mycology included all the major groups of Fungi and fungus-like organisms. A lab, weekend field trips, and a culture project were included in his course. In a time before computers, Bob presented the fungi in well-crafted lectures, illustrated with chalk drawings, outlined with impeccable handwriting, and supplemented with selected slides. His calm patience when explaining or re-explaining concepts to students was exceptional.

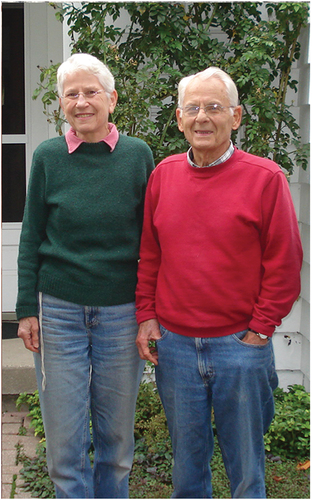

Bob taught several mycology courses at “bug camp,” the University of Michigan’s biological station at Douglas Lake. Higher Fungi was the first course he taught there. This course had been taught for many years by Alexander Smith, but Bob alternated as the teacher in even years from 1962 to 1968. He also must have had some prior association with the course because he spent a summer there in 1957, when Smith was teaching it and when Bob was employed by the University of Chicago. However, the most important event that summer was romantic rather than mycological: he met Jocelyn Gobeille, who worked as a dietician in the camp kitchen. Their chemistry clicked; they married in the fall of 1958 and were nearly inseparable companions for the next 63 years ().

Bob continued to teach the Higher Fungi course at bug camp into the early 1970s, and in 1973 he also taught “Lower Fungi,” a course previously taught by Fred Sparrow. Bob combined these two courses into a general course on Fungi, which he last taught in 1985. This broader fungal course included some culturing and water mold baiting but still focused primarily on collection and identification of macrofungi, and it attracted many mycology students from outside the University of Michigan. Linda Kohn, Kerry O’Donnell, and Jim Anderson (as a guest) are some examples of mycologists that passed through his course. Daily field trips were an integral part of the course, and they revealed a side of Bob that was more extemporaneous, as his thrill of seeing interesting, unexpected, or beautiful fungi was unmistakable and infectious. The course was notoriously demanding, especially the final exam. Nevertheless, the course was also outrageously fun!

These same patterns emerged in Bob’s adult education mushroom class, but here the enthusiasm he had for the course and that he generated within the participants can be easily documented in two ways: (i) He started the class in 1966 and taught it every year until 2017, 52 years in all. The last 24 years was after he had retired. (ii) Most of the class consisted of people that repeated the course for many years. The record for repeating was held by a man who had taken the course every year since 1973. There was a weekly evening lecture, but the heart and soul of the course were the four weekend field trips that started in September and ended in October. These field trips always went to the same four locations in the same order each year: Haven Hill Natural Area, Hudson Mills Metro Park, Stinchfield Woods, and Proud Lake Recreation area. On these trips class members were turned loose to hunt mushrooms, and they returned after a couple hours to spread their finds out on picnic tables. Bob, with help from various veteran class members, sorted out the collections, identified them, and labeled them using a set of laminated cards to produce an ad hoc, outdoor display. When the display was assembled, Bob would discuss some of the interesting finds and answer individual questions about particular collections. While this was going on, Bob’s wife Jocelyn sautéed selected species on a camp stove. Her results were offered up on toothpicks for people to sample as Bob gave his carefully worded warning: “This species is edible for most people, most of the time, if properly prepared.” Lots of interesting mushroom species were cooked up and served in this way: Marasmius oreades, Lepista irina, Entoloma abortiva, Tricholoma myomyces, Armillaria spp., and many others that the less adventurous might not try on their own. He had his favorites (e.g., chanterelles), but the offerings weren’t limited to those. When people were taken by the taste of species that did not impress him, he often remarked: “well, there is no accounting for taste,” and his subtle smile gave away the humor in his otherwise dead-pan delivery. “That’s a distinction without a difference” was another of his humorous quips; this one was applied to characteristics in keys that didn’t hold up to scrutiny. After the display and taste tests were over, a group pot-luck picnic would ensue with many outrageously tasty contributions, coupled with wine and sometimes spirits. All this was done “rain or shine,” and Michigan weather being what it is, conditions could be trying for the faint of heart. However, weather seldom dampened the enthusiasm of this class. I fondly remember a cold, windy, snowy day at Proud Lake with people huddled around the picnic table under the shelter, proposing toasts to Boletinellus merulioides with shots of Slivovitz while finishing their gourmet picnic as the snow accumulated.

Returning to more standard aspects of teaching, Bob mentored three PhD students: Harriet A. Burge (1966), Tina (Gilliam) Davies (1973), and Tom Bruns (1987). As his last graduate student, I can attest that he gave me total freedom to explore my interests while providing enough advice and opportunity to help me successfully navigate graduate school and to ensure my success. The opportunity to be a teaching assistant for his mycology courses on campus and at the summer field station was the best training I ever could have hoped to receive for later teaching similar courses. He was also a diligent, thorough, helpful editor, and the precise language that he employed in his own written and spoken language came through in his edits. His handwritten comments often exceeded the length of my drafts and explained finer points of grammar to me in patient, clear detail.

Despite the time and expertise that he provided to me, he was never a coauthor on any of my papers, even those derived directly from my dissertation. This same pattern is also true for his other two PhD students. In today’s world of multiauthor, collaborative papers, this policy seems almost incredible, but for Bob it was simply the right thing to do: a student’s work was their own. This may have been a common view at the time Bob was starting his career, but he adhered to it long after it was no longer common. This probably reflected a deeper attitude that he held toward doing one’s own work and not taking credit for that of others. His work provides further evidence of this attitude, as his papers were almost all single-authored. He only coauthored a few papers, presumably those where there were true collaborations, and in most of those I suspect he was the primary contributor.

People who met Bob on campus for the first time might have mistaken his quiet, reserved nature for formality or pretense, but his down-to-earth nature and subtle humor put that image to rest for anyone that got to know him. He seemed most at home in blue jeans and a denim jacket, although he rarely wore these on campus. When he concentrated on his work, he often emitted a barely audible, and probably unconscious, hum that radiated his inner happiness. Outside of work he enjoyed an eclectic range of music that spanned from baroque to Willy Nelson. In addition to good food, he loved wine, good and bad, and made some of the latter from Michigan concord grapes. He was an avid gardener and created a beautiful rock-wall garden at his home in Ann Arbor, and he and Jocelyn traveled extensively to exotic, slightly off-beat places such as Peru, India, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Tunisia. Those of us that knew him will miss his presence, especially when mushrooms fruit in Michigan. He is survived by his wife Jocelyn and daughter Martha.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Martha (Shaffer) Nobunaga, Tina (Gilliam) Davies, Aimee Clausen, Kurt Sonen, and Renee Robins for information, and anecdotes on Bob.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

LITERATURE CITED

- Anonymous 2022. Memoir Robert Shaffer, Regents’ Proceedings 75, University of Michigan, Faculty History project. [Accessed May 15, 2022]. http://faculty-history.dc.umich.edu/faculty/robert-shaffer/memoir

- Bazzicalupo AL, Buyck B, Saar I, Vauras J, Carmean D, Berbee ML. 2017. Troubles with mycorrhizal mushroom identification where morphological differentiation lags behind barcode sequence divergence. Taxon. 66(4):791–810.

- Homola RL, Shaffer RL. 1975. A new Russula of the subsection Nigricantes from northeastern North America. Mycologia. 67(2):428–34.

- Shaffer RL. 1957. Volvariella in North America. Mycologia. 49(4):545–79.

- Shaffer RL. 1962a. Synonyms, new combinations, and new species in Volvariella (Agaricales). Mycologia. 54(5):563–72.

- Shaffer RL. 1962b. The subsection compactae of Russula. Brittonia. 14(3):254–84.

- Shaffer RL. 1964. The subsection Lactarioideae of Russula. Mycologia. 56(2):202–31.

- Shaffer RL. 1970. Notes on the subsection Crassotunicatinae and other species of Russula. Lloydia. 33:49–96.

- Shaffer RL. 1972. North American Russulas of the subsection Foetentinae. Mycologia. 64(5):1008–53.

- Shaffer RL. 1975. Some common North American species of Russula subsect. Emeticinae Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia. 51:207–37.

- Shaffer RL. 1989. Four white-capped species of Russula (Russulaceae). Mem N Y Bot Gard. 49:348–54.

- Shaffer RL. 1990. Notes on the Archaeinae and other Russulales. Contrib Univ Michigan Herbarium. 17:295–306.

- Shaffer RL, Rogerson CT. 1952. Notes on the Fleshy Fungi of Kansas. Trans Kansas Acad Sc. 55(3):282–86.