Abstract

Corpus linguistics is, to date, still an underexplored methodology in onomastics. This article seeks to advance the field through a theoretical discussion of onomastic issues from a corpus linguistic point of view. It presents an overview of the linguistic status, meaning and grammar of proper names in order to highlight aspects that lend themselves to corpus linguistic inquiry. Earlier onomastic research is adduced, to highlight how corpus linguistic methods have substantially improved our understanding of names in language use. While previous onomastic work has often concentrated on the description of names in their own right, without necessarily taking the usage context into account, it is argued that the investigation of the semantics and the grammar of names needs to be complemented by work that draws on usage-based, corpus linguistic evidence. A stronger integration of four types of corpus linguistic analysis (frequency analysis, concordance analysis, collocation analysis, keyword analysis) is suggested for future research.

1. Introduction

Historically, onomastic research has drawn on a broad range of methods to shed light on topics such as the history and etymology of names, the meaning and grammar of names, and the social relevance of naming practices (see Eichler et al. Citation1995). Corpus linguistic methods (Biber and Reppen Citation2015; McEnery and Hardie Citation2012; Motschenbacher Citation2018), however, have played a minor role in the field. This relative absence is unfortunate, as corpus-based investigations represent a powerful way to study and empirically verify the linguistic characteristics of names as they surface in actual language use, especially at the semantic and grammatical levels. The performance focus of corpus linguistics sets it apart from other methods in the field of onomastics that are more competence-centred and rely on introspection or the consultation of reference works. This article, therefore, seeks to outline the theoretical foundations for establishing a stronger connection between onomastics and corpus linguistics. More specifically, it delineates central features of proper names and highlights which name-related properties can usefully be studied with corpus linguistic methods.

The term “corpus” has been used in two major senses in name studies. The more traditional usage refers to any linguistic dataset that is used as the basis for an onomastic study. Such corpora are often historical, non-computerised and may well consist of material that constitutes a list of names or data such as address books, telephone books or name indexes (Greule Citation1995). This is not the type of corpus that is relevant here. The more recent notion of “corpus” that lies at the heart of this article is that of a collection of textual data which can be searched through computer software and in which names (and other linguistic forms) occur as parts of larger syntactic constructions.

The following section discusses the linguistic status of proper names, comparing them to common nouns and pronouns as the two word classes that share central properties with proper names (Section 2). Section 3 hones in on the various types of meaning that proper names may carry. This is followed by a selective outline of the grammar of proper names in Section 4. Section 5 presents findings from previous corpus-based name studies. The final section makes suggestions for future corpus-based onomastic research by outlining which kinds of research questions can be explored using corpus linguistic methods (Section 6).

2. The linguistic status of proper names

Proper names have often been compared to common nouns and personal pronouns, with which they share central characteristics (van Langendonck Citation2007, 169–171). For example, like common nouns (and unlike pronouns), proper names form an open word class that easily allows for the addition of new members. They can also be combined with adjectives and other modifiers (the late king – the late Shakespeare – *the late him). In English, neither common nouns nor proper nouns are case-inflected (vs. pronominal case distinctions: I – me, he – him etc.). In languages with grammatical gender, both common nouns and proper nouns possess an inherent grammatical gender value, while pronouns often agree with controller nouns and, therefore, show various grammatically gendered forms.

Along with pronouns, proper names have inherent definiteness. Common nouns, by comparison, require a definite article to become definite (she – Mary – the woman). Proper names and pronouns both serve a referential rather than descriptive function. Moreover, both cannot normally be used in connection with determiners, restrictive adjectives, or restrictive modifiers such as relative clauses and prepositional phrases.

An important terminological distinction exists between “proper nouns” and “proper names”. “Proper nouns” are nouns that are used as names for certain entities, such as persons, cities or countries. In written English, they tend to form single, capitalized orthographic words (e.g. Mary, London, Greece). The term “proper name”, by contrast, denotes a more abstract class of naming expressions of various complexity, including simple proper nouns (London), combinations of proper nouns (London Heathrow), modified proper nouns (Greater London), combinations of common and proper nouns (London Bridge), noun phrases containing a proper noun (Tower of London) or (originally) descriptive noun phrases without any proper noun (Tower Bridge) (Allerton Citation1987, 63–64).

From a cognitive point of view, it is essential to note that proper names exhibit prototype effects, that is, particular (groups of) names may show more or fewer of the grammatical and semantic features generally considered to be typical of names. Tse (Citation2000, 491–493), for example, identifies orthographic, morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria for the identification of proper name (vs. common noun) status. Orthographically, proper names in English are typically marked by initial capitalization (Oxford – *oxford).

Morphologically, a proper name prototypically consists of a singular proper noun that does not allow for pluralization (Oxford – *Oxfords). Similarly, less prototypical proper names that are collective plural forms do not allow for singularization (the Alps – *the Alp). This restriction suggests that proper names do not exhibit a functional grammatical number contrast.

At the syntactic level, the absence of a premodifying article (or any other determiner) is typical of proper names (Oxford – *the Oxford). Proper names are inherently definite and thus generally form full noun phrases on their own. They cannot normally express contrastive definiteness (Oxford – *an Oxford – *the Oxford; *Hague – *a Hague – The Hague). This characteristic indicates that definite articles occurring with proper names do not have the same function as definite articles that occur with common nouns. The latter need the article to become definite and to achieve reference. By contrast, names already inherently possess a definite meaning and a referential function. They, therefore, do not typically allow for a definite article or restrictive modification (Anderson Citation2015, 606–607). Originally non-proper components of proper names are also not contrastive. Whereas a (non-proper) noun phrase like the good book can be contrasted with other noun phrases (the bad book, the interesting book; the good song, the good film), this is not usually possible with proper names (Long Island vs. *Short Island, *Long River).

Semantically speaking, proper names have an identifying function, as they denote a single individual rather than classes of entities. They are often considered to be devoid of lexical meaning, even though they can regularly be traced back to descriptive lexical items (Oxford < originally “passage for oxen”). These etymological meanings, however, are synchronically irrelevant as far as the description of a referent is concerned; and, in many cases, they are no longer transparent. The function of direct referential identification is a characteristic that proper names share with pronouns and noun phrases (or determiner phrases) (Colman Citation2014, 50; Ghomeshi and Massam Citation2009; Lyons Citation1977, 179). This similarity suggests that proper names are more similar to noun phrases than to nouns. This can also be seen in coordinative structures, where names can be combined with noun phrases (Tom and the dog) but not with bare nouns (*Tom and dog) (Ghomeshi and Massam Citation2005, 1). The referential function of proper names is independent of context (for example, Greece always refers to the same entity), whereas noun phrases and pronouns can only identify entities contextually (it depends on the context whether the noun phrase the country or the pronoun it refers to Greece or another country, for example).

Personal names, and in particular given names like Mary or John, are generally considered to be the most prototypical name categories, as they exhibit all of the criteria outlined above (Tse Citation2000, 494). Place names like London, Austria, or Europe are also prototypical proper names. Among place names, however, the incidence of less prototypical cases – that is, cases which do not show some of the features discussed above – is much higher than it is among personal names.

3. The meaning of proper names

The semantic status of proper names has been extensively discussed in linguistics and language philosophy (for detailed overviews of these debates, see Anderson Citation2007; van Langendonck Citation2007). Most linguists agree that proper names are mainly used to refer to certain entities, not to describe them. A central issue in this respect is the question of whether proper names carry a meaning or not – a question that crucially hinges on the notion of “meaning” employed. On the one hand, there are proponents of the view that proper names do not possess a lexical meaning but directly refer to a certain entity. This perspective is sometimes called “the Millian approach”, in honor of its first prominent proponent in the 19th century, John Stuart Mill. In line with this view, names are frequently described as “rigid designators” (Kripke Citation1980) without any lexical meaning that would restrict the number of potential referents (as is typical of common nouns).

On the other hand, there are theorists who argue that proper names do carry certain meanings (e.g. Colman Citation2014; van Langendonck Citation2004, Citation2005). Various types of meaning are potentially relevant here: denotational vs. connotational meanings; lexical vs. proprial meanings; and presuppositional meaning (Nyström Citation2016). Denotation refers to the relation between a certain form and the class of entities to which it can be attributed (the so-called “denotata”). Denotational meaning stays constant across usage contexts and, therefore, largely corresponds to the dictionary definition of a lexical item. Proper nouns are special in this respect, as they denote only one particular entity (and are not normally listed as entries in dictionaries). Of course, there may be several entities in the world that carry the same name (Cambridge in Masachusetts and in the UK; personal given names in general). However, this fact does not mean that the name denotes these referents as a class. For example, a noun like boy denotes all young male human beings, but a name like George does not create a similar, semantically based class of entities (Ghomeshi and Massam Citation2009, 74).

Besides their unique denotation, proper nouns may possess connotative meanings. Language users may have various associations with names depending on their personal knowledge and experience. Take the name Oxford, for instance: for some, it may be a place associated with an academic elite; for others, it may be the place where their grandmother lives. Such connotations can be quite individual (the grandmother association), but often they are shared by many people (the academic elite association). With regard to personal names, they frequently involve connotations concerning the social group to which the name bearer is thought to belong. For example, in German society, some English-based male names (Justin, Kevin) and French-based female names (Chantal, Jacqueline) are stereotypically connected to a lower social-class milieu, while other names like Ronny, Maik, Mandy, Nancy, Dorit or Doreen are stereotypically connected to Eastern Germany or the former GDR (Hayn Citation2016, 99–101).

Another meaning distinction that has a bearing on proper names is between lexical and proprial meanings. Names that are etymologically nontransparent possess a proprial meaning (e.g. London, Prague), as they are exclusively used to identify a certain entity. However, names may contain elements that are homonymous with parts of the lexicon of a language and thus carry a lexical meaning (e.g. New York, Long Island). Even though these elements (new, long, island) may be thought to have no lexical meaning when they form parts of names, their descriptive meaning may in fact be contextually activated. For example, people may be startled if they find that Long Island is not literally a long island. This surprise bears witness to the fact that people treat the lexical meaning as potentially relevant.

Finally, names may carry presuppositional meanings. One such meaning type that is highly common in names is categorical meaning: the perception that a name is connected to a certain kind of basic-level concept category (Nyström Citation2016, 48; van Langendonck Citation2007, 86). For example, even if someone does not know who the referent of a name like Stephanie or Christopher is, that person will still most likely assume that these names refer to a person and that that person may be female or male, respectively. Likewise, Smith is commonly perceived as a personal surname, Birmingham as a place name, Thames as a river name, Lassie as the name of a dog, etc. These categorical name meanings are presupposed, even though they may be contextually incorrect (sometimes Stephanie may be the name of a dog, or Birmingham may be a personal surname). The categorical meaning of names can often be made explicit through extension to a complex phrase (the city of Birmingham, the river Thames, Lassie the dog etc.) or an obligatory name part (e.g. the Czech Republic).1

One recent development in the onomastic discussion of name meaning is the “pragmatic approach”. This approach was developed by Coates (Citation2005, Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2009), who distinguishes between two types of referential modes: onymic reference and semantic reference. Both modes can, in principle, be expressed by both proper names and descriptive noun phrases, even though there is a strong tendency for onymic reference to be performed by means of the former and for semantic reference to be associated with the latter. In other words, “properhood” does not inherently reside in certain forms, but in the onymic use to which forms are put in a communication context. This usage mode is in principle applicable to all kinds of nouns, not just proper names (Coates Citation2006a). Thus, language change processes that involve proper nouns turning into common nouns (Kleenex > kleenex, Band-Aid > band-aid), and vice versa (long island > Long Island) are associated with shifts in the dominant usage patterns of forms.

Using country names as an example, etymologically nontransparent, morphologically simple names like Greece or Norway are commonly used as proper names, that is, for purposes of onymic reference. They tend to denote a unique entity, namely the country in question. In certain contexts, however, these names may be used as common nouns that denote a certain type of the entity denoted by the name (the Greece I used to know, today’s Greece). Conversely, the noun phrase the old vicarage can be used either by exploiting its descriptive semantic content (“an old house where a vicar lives”), or by onymically referring to a specific house (The Old Vicarage), which may not be old or a vicarage but rather a newly established pub (Coates Citation2005, 130).

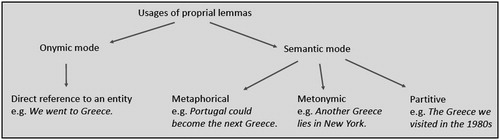

Van Langendonck (Citation2005, 316) postulates an abstract lexematic category, the “proprial lemma”, which unites the various onymic and semantic referential uses of a certain form (see also Vandelanotte and Willemse Citation2002; van Langendonck Citation2007, 7–8; van Langendonck and van de Velde Citation2016, 19–20). Proper names are defined as forms that are onymically used, while proprial lemmas include a number of other usage types, including appellative (a different Oxford) and metalinguistic uses (This city is called Oxford) (van Langendonck Citation2005, 318–321). illustrates the (prototypical) onymic and the (less prototypical) semantic mode with a country name example. In the semantic mode, the name potentially allows for grammatical constructions that would normally be reserved for common nouns (pluralization, restrictive modification; Vandelanotte and Willemse Citation2002, 10).

4. The grammar of names

The grammar of names, and more specifically of English proper nouns, has intrigued linguists for several decades (e.g. Anderson Citation2004, Citation2007; Berezowski Citation1999a; Kałuża Citation1968; Long Citation1969; Matushansky Citation2006; Schlücker and Ackermann Citation2017; Seppänen Citation1982; Sørensen Citation1963; van Langendonck and van de Velde Citation2016). Much of this work has been based on the analysis and discussion of intuitive examples or episodic linguistic evidence. Some studies on place name syntax have an applied linguistic focus, highlighting, for example, the problems that foreign language learners encounter when deciding whether to use a certain place name with or without a definite article. This is a common problem for learners whose L1 does not possess articles, such as in Polish (Berezowski Citation1997, Citation1999b).

Corpus-based studies of proper names and their linguistic constructions remain the exception, even though the grammatical description of English based on corpus evidence has turned into a vibrant field of study for at least two decades (corpus-based name studies are further discussed in Section 5). This not only means that we still have a limited picture of how proper nouns are actually used, but also that the descriptions we have are strongly influenced by notions of how proper nouns should be used in accordance with standard language norms.

This problem is further exacerbated by the fact that much of the work on the grammar of proper nouns identifies patterns that are highly relevant for personal names, as they are the most prototypical name type. Other name types with somewhat different patterns, however, are often ignored. Within the category of place names, for example, there are various subgroups which do not follow the default rule that proper nouns do not take a definite article. While names of cities (London, Berlin), lakes (Lake Geneva, Loch Ness), streets (Oxford Street, Abbey Road), squares (Leicester Square, Picadilly Circus), parks (Central Park, Hyde Park), islands (Shetland, Sicily) or counties (Sussex, Lancashire) are generally used without a definite article, names of rivers (the Thames, the Hudson), oceans (the Atlantic, the North Sea), channels (the Channel, the Suez Canal) or deserts (the Sahara, the Atacama Desert) overwhelmingly take a definite article (for detailed overviews, see Biber et al. Citation1999, 246; Hewson Citation1972, 109; Horowitz Citation1990, 96–98). However, as illustrated by Tse (Citation2005, 218–220), nearly all place name groups show a certain degree of variance with respect to article use. This variation is usually treated as irrelevant in reference grammars. For English country names, for example, earlier linguistic treatises or reference grammars (such as Quirk et al. Citation1985, 296; Jespersen Citation1954, 545) specify general “rules”. Even though such rules may be useful initial yardsticks for foreign language learners, they do not do justice to the high degree of variability we find in concrete usage data.

Place names in general show more variance in their morphological structure than personal names (Back Citation1996; Berger Citation1996; Schnabel-Le Corre Citation2014; Zinkin Citation1969). They are often semantically more transparent and incorporate linguistic material other than proper nouns with a descriptive meaning potential (Tse Citation2005, 28). It has been shown that, with place names, an increase in morphological complexity roughly corresponds to a decrease in the degree of human association of a particular geographical entity type (Anderson Citation2007, 115; van Langendonck Citation2007, 204–210):

Category 1: Monomorphemic forms (zero marking) (e.g. city names): London, Prague

Category 2: Suffixed forms (e.g. country names): Kazakh-stan, German-y

Category 3: Names incorporating a preposed definite article (e.g. river names): the Thames, the Rhine

Category 4: Names incorporating a classifier noun (and a definite article) (e.g. oceans): the Baltic Sea, the Pacific Ocean2

This formal cline has been cross-linguistically verified and reflects a semantic gradation. Cities (and other settlement types) show the highest degree of human association and habitability, and typically have monomorphemic names.3 Countries, as sets of settlements, can be considered as secondarily humanized, with their collective status typically being expressed through suffixation. Rivers show a lower degree of human organization and administration and are used in combination with a definite article, that is, a separate function word. Finally, oceans, as the least humanized geographical entities, regularly contain a classifying noun in their names, in addition to a definite article (van Langendonck Citation1998).

Country names show interesting grammatical idiosyncracies when compared to the category of proper nouns more generally or to place names more specifically. In contrast to other place name categories, which exhibit a dominant pattern of absence or presence of a definite article, country names show more variability in definite article use. As far as anaphoric pronominalization is concerned, country names do not just allow for the normal pattern of singular inanimate pronominalization (Britain – it), but also for the use of female (Britain – she) and plural pronouns (Britain – they). They may allow for singular and plural verbal number concord (the United States has/have…) and show a high degree of variance in the way they form genitive constructions (China’s economy; a map of China). Moreover, placing country names in general in Category 2, as discussed above, is far too simplistic. In English, for example, they represent a structurally diverse group that includes monomorphemic forms (e.g. Greece, Japan, Spain, Zimbabwe), suffixed forms (e.g. German-y, Slovak-ia, Afghan-istan, Chin-a), phrases with incorporated definite articles (e.g. the Congo, the Ukraine, the Vatican), and phrases that incorporate a classifier noun and a definite article (e.g. the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, the United States; see Motschenbacher Citation2020).

5. Corpus-based name studies

Within the field of onomastics, the focus of attention has traditionally been on names in their own right, which means that their linguistic usage context has only insufficiently been taken into consideration. Corpus linguistic studies, which constitute a powerful way of incorporating this aspect, remain the exception in onomastics to date. One group of proper-name related studies that can reasonably well be considered corpus-based are those conducted by Tse using the British National Corpus (BNC) as data (see Tse Citation2004 on personal names, and Tse Citation2003, Citation2005 on organization names). Tse (Citation2005), for example, studies organization names in a 500,000-word newspaper subcorpus of the BNC and presents a number of interesting findings. Organization names are, on average, morphologically more complex than person or place names. The presence or absence of a definite article with such names depends on certain structural aspects. Postmodification by a prepositional phrase (Bank of Iran), premodification by a common noun phrase (Endangered Wildlife Trust) and common noun phrases as heads (Women’s Environmental Network) significantly increase the likelihood of definite article use. Names showing premodification by a proper noun (Buckingham Palace), an acronym (UN Security Council) or a phrasal name (Bernt Carlsson Trust) favor uses without article (Tse Citation2005, 140).

Tse’s (Citation2005) study also contains shorter sections on other proper name types. The section on place names (Tse Citation2005, ch. 3.3), for example, provides corpus-based quantitative evidence of prototypical place-name features. Most place names in Tse’s study consisted of one (62.96%) or two orthographic words (30.24%). Among the one-word place names, 94.38% were proper nouns. Plural place names were invariably found to take a definite article, while singular place names only rarely followed this pattern. Among the multi-word place names, the most common structures showed varied article frequencies. Combinations of proper noun plus common noun (Belton House) exhibited a definite article rate of 32.56% (56 out of 172 names), combinations of adjective plus proper noun (Old Cairo) of 4.71% (4 out of 85 names), and combinations of adjective plus common noun (Golden Temple) of 79.25% (42 out of 53 names) (Tse Citation2005, 72–73). This suggests that the presence of a proper noun within a proper name substantially reduces the likelihood that a definite article is used.

A more recent corpus linguistic study that investigates the grammar of English country names is Motschenbacher (Citation2020). The study uses the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) to shed light on the grammatical behavior of English country names, more specifically on their co-occurrence with a definite article. It is shown that virtually all country names occur with a definite article to some extent and that certain grammatical constructions require the use of a definite article with country names. An inspection of concordance lines reveals that a definite article is normatively required in contexts where a country name forms a specifier within a compound (e.g. the Iraq War). In such cases, the article gives definiteness to a noun phrase that is headed by a noun other than the proper name. Another construction type that calls for definite article use is country names postmodified by a prepositional phrase or a relative clause (e.g. the Iraq of our dreams; the Iraq he knows). In these constructions, the article modifies the country name, which serves as the head of the noun phrase.

Even after ruling out such invariant grammatical contexts, some country names exhibit substantial definite article rates. This proves that the general rule that country names do not occur with a definite article (see, for example, Quirk et al. Citation1985, 291, 293) is an abstraction or oversimplification, and that the situation in actual language use is more complex. Moreover, the study shows that name morphology had a substantial influence on definite article use, with plural forms (e.g. Bahamas, Netherlands), compounds that incorporate a classifier noun (e.g. Czech Republic, United Kingdom), and abbreviations (e.g. UK, USSR) exhibiting the highest definite article rates. Monomorphemic country names (e.g. Egypt, Greece), suffixed country names except plurals (e.g. Germany, Uzbekistan) and country names in which the proper noun is specified by an adjective (e.g. North Korea, New Zealand), by contrast, show low rates of definite article usage.

The findings of the corpus-based studies presented here yield a more detailed, more complex and descriptively more adequate picture of names in actual language use than the prescriptive rules often formulated in grammars and reference works. It is also crucial to note that such usage patterns could not have been empirically documented by methodologies other than corpus linguistics.

6. Looking ahead: The potential of corpus linguistic onomastics

As outlined in the previous section, the findings of the few corpus linguistic onomastic studies that have been conducted to date are promising and, therefore, invite a more systematic integration of corpus linguistics within name studies. In order to achieve this, we need to have a basic understanding of what corpus linguistic methods can do and which aspects of names they are equipped to shed light on.

Corpus linguistics provides powerful empirical methods for studying names in actual language use through frequency-based evidence. It can, therefore, serve to check and refine more traditional, normative descriptions of name usage as found in grammars and other reference works. As a method that also reveals nonstandard language use (see Kjellmer Citation2002), it is an excellent instrument to document variability in the use of names, and it can provide insights into what causes this variability. Corpus linguistics is, therefore, especially useful for the investigation of names and name categories that are less prototypical in their grammatical behavior.

One important point to note is that corpus searches invariably rely on linguistic forms. This means that we can get direct access to any name-related linguistic structure (for example, onomastic affixes, individual names, and grammatical constructions involving names; Schlücker and Ackermann Citation2017) through a creation of pertinent search queries (compare Butler et al. Citation2017). However, functional aspects of names are more difficult to retrieve. “Properhood”, for example, is an abstract functional category that cannot directly be searched for using structurally based search queries.

There are two solutions to this problem. Where resources permit it, corpora can be tagged for certain functions (such as grammatical functions, semantic meanings, pragmatic functions), and then such tags can be incorporated in search queries (see van Dalen-Oskam and van Zundert Citation2004). If this is not possible, access to functional aspects in a corpus will generally be indirect, through linguistic forms. This, in turn, means that the analyst needs to develop a good understanding of the form-to-function mapping that is relevant for the linguistic phenomena that are of interest. With respect to the meaning of names, for example, it is important to note that a corpus search for a specific name will normally yield results that range across the various uses of a proprial lemma (see ), of which the majority, but not all, can be assumed to be onymic uses.

Despite this caveat, corpus linguistics provides powerful methods for investigating how names are used. These methods are mainly quantitative but are generally used in tandem with qualitative modes of analysis, to yield a richer, more comprehensive picture of linguistic phenomena. A common procedure is, for example, to find out what is frequent in a corpus, and then to select these prominent features for a more detailed, qualitative analysis. In the following, I highlight four central types of corpus linguistic analysis and what kinds of name-related research questions they can help answer.

The most basic type of corpus linguistic analysis is frequency analysis. Most corpus linguistic name studies draw on this type of analysis, that is, they analyze how often certain onomastic phenomena occur in a text corpus (e.g. Laversuch Citation2010; Motschenbacher Citation2020; Nick Citation2017; Oelke, Kokkinakis, and Malm Citation2012; Ström Herold and Levin Citation2019; van Dalen-Oskam Citation2012, Citation2016). Such an analysis provides information on the commonness of individual names, onymic affixes and name-incorporating grammatical constructions in language use.

This basic quantitative procedure can be usefully complemented by a qualitative analysis of concordance lines (e.g. Motschenbacher Citation2020), which yields initial evidence for which structures co-occur in the syntactic environment of the name in question. A concordance analysis usually involves the inspection of a random sample of the concordance lines of a search term. It is, therefore, an adequate method to check the syntactic constructions in which a name is typically embedded (for example, whether it takes a premodifying definite article or not). On the semantic level, a concordance analysis can provide information on the semantic prosodies a name is associated with (for example, if it tends to co-occur with terms that carry a positive or negative meaning). Consequently, this type of analysis may be particularly useful for uncovering the connotational meanings of names.

Collocation analysis has, so far, only sporadically been used in onomastic studies. This type of analysis helps to identify which linguistic forms occur unusually frequently, statistically speaking, in syntactic proximity to a search word. It rests on the assumption that the meanings and functions of a term do not exclusively reside in the term itself but also in the forms with which it is frequently used. It can be carried out using a concordance tool such as AntConc (Anthony Citation2018) and allows the specification of various window spans around the search term. With this procedure, we can find out which lexical items or grammatical function words collocate with a particular name (e.g. Vuillemot et al. Citation2009; see Adler, Perkuhn, and Plewnia Citation2017 on the collocates of the German name Griechenland “Greece” in texts published before and after the financial crisis). If we work with semantically tagged data, we can also find out with which semantic categories a name tends to co-occur (see Baker et al. Citation2019; Gregory and Hardie Citation2011 for such analyses of British place names in historical documents). In a similar vein, collocation analysis could, for example, be adduced to find empirical evidence for the degree of human association of individual place names and place name categories. Place names that show a higher degree of human association can be expected to exhibit more personal nouns in the co-text.

A final corpus linguistic method that offers new opportunities for name studies is keyword analysis. This quantitative procedure is based on the comparison of two corpora and can be employed to identify which forms are quantitatively salient in one corpus when contrasted with the other. Keyword analysis can be used to compare corpora documenting different text genres, time periods or regional varieties, for example, thus allowing the analyst to gain a better understanding of how usage context shapes the use of names (van Dalen-Oskam Citation2013; see Motschenbacher Citation2019 for a study in which proper nouns turn out to be substantially involved in the discursive construction of a person before and after his public coming out as a gay man). More generally, a comparison of several corpora dating from different time periods can shed light on language change and the historical development of name-related phenomena (see Vartiainen Citation2019).

As can be seen from the description above, the instruments that corpus linguistics offers have the potential to substantially improve our knowledge about how names are actually used. They are likely to give us a better understanding of how the use of names is shaped by the lexical, grammatical and extralinguistic context, which constructions they engage in, and which meanings they are associated with beside their basic denotation. Previous onomastic work has often concentrated on the description of names on their own, without necessarily taking the usage context into account. Such work can usefully be complemented with research adducing usage-based, corpus linguistic evidence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heiko Motschenbacher

Heiko Motschenbacher is currently a full Professor for English as a Second/Foreign Language at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen. Since November 2017, he’s conducted research on an EU-funded, three-year Marie Curie Global Fellowship in cooperation with Florida Atlantic University, USA, and Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main, Germany. He’s founder and co-editor of the “Journal of Language and Sexuality” (with William L. Leap). His recent publications include the New Perspectives on English as a European Lingua Franca (2013; John Benjamins) and Language, Normativity, and Europeanisation (2016; Palgrave Macmillan). He’s co-edited a special journal issue of “Discourse & Society on Queer Linguistic Approaches to Discourse” (2013, with Martin Stegu), Gender Across Languages: The Linguistic Representation of Women and Men vol. 4 (2015, with Marlis Hellinger), and a special issue of “Language and Sexuality” on Corpus Linguistics in Language and Sexuality Studies. For further information, see www.quinguistics.de.

Notes

1 Alternatively, Anderson does not treat categorical meaning as a presuppositional feature of names but rather describes it in terms of sense (rather than denotation) (Anderson Citation2015, 602–603).

2 This cline is reminiscent, and probably conceptually related, to the well-known animacy hierarchy that has been documented to affect linguistic phenomena such as semantic vs. grammatical agreement in certain satellite types (see Corbett Citation1991).

3 English settlement names are generally monomorphemic. They may contain components such as -ford, -ham, -ton, or -wick, which on the surface look like morphemes but only possess morphemic status from a diachronic point of view (van Langendonck Citation1998, 342).

Bibliography

- Adler, Astrid, Rainer Perkuhn, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2017. “Rettung – Pleite – Griechenland: Wortschatzstatistik in Zeiten der Finanzkrise.” [Rescue – Bankruptcy – Greece: Vocabulary Statistics in Times of the Financial Crisis]. In Wirtschaft erzählen: Narrative Formatierungen von Ökonomie, edited by Irmtraud Behr, Anja Kern, Albrecht Plewnia, and Jürgen Ritte, 213–234. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

- Allerton, David John. 1987. “The Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Status of Proper Names: What Are They, and Who Do They Belong To?” Journal of Pragmatics 11, no. 1: 61–92.

- Anderson, John M. 2004. “On the Grammatical Status of Names.” Language 80, no. 3: 435–474.

- Anderson, John M. 2007. The Grammar of Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, John M. 2015. “Names.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Word, edited by John R. Taylor, 599–615. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anthony, Laurence. 2018. AntConc (Version 3.5.7) [Computer Software]. Tokyo: Waseda University. http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/.

- Back, Otto. 1996. “Typologie der Ländernamen: Staaten-, Länder-, Landschaftsnamen.” [Typology of country names: State, country and areal names]. In Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics, edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger, and Ladislav Zgusta, vol. 2, 1348–1356. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Baker, Helen, Ian N. Gregory, Daniel Hartmann, and Tony McEnery. 2019. “Applying Geographical Information Systems to Researching Historical Corpora.” In Corpus Linguistics, Context, and Culture, edited by Michaela Mahlberg and Viola Wiegand, 109–136. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Berezowski, Leszek. 1997. “Iconic Motivation for the Definite Article in English Geographical Proper Names.” Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 32: 127–144.

- Berezowski, Leszek. 1999a. “English Proper Name Modification and the Article Usage.” Anglica Wratislaviensia 35: 125–135.

- Berezowski, Leszek. 1999b. “Practical Tools to Master Definite Article Usages with English Geographical Names.” In On Language Theory and Practice. Volume 1: Language Theory and Language Use, edited by Maria Wysocka, 59–71. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Berger, Dieter. 1996. “Morphologie und Wortbildung der Ländernamen.” [Morphology and word formation of country names]. In Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics, edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger, and Ladislav Zgusta, vol. 2, 1356–1360. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Longman.

- Biber, Douglas, and Randi Reppen, eds. 2015. The Cambridge Handbook of English Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Butler, James O., Christopher E. Donaldson, Joanna E. Taylor, and Ian N. Gregory. 2017. “Alts, abbreviations, and AKAs: Historical Onomastic Variation and Automated Named Entity Recognition.” Journal of Map & Geography Libraries 13, no. 1: 58–81.

- Coates, Richard. 2005. “A New Theory of Properhood.” In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Onomastic Sciences (Uppsala, 19–24 August 2002), edited by Eva Brylla and Mats Wahlberg, vol. 1, 125–137. Uppsala: Språk- och Folkminnesinstitutet.

- Coates, Richard. 2006a. “Properhood.” Language 82, no. 2: 356–382.

- Coates, Richard. 2006b. “Some Consequences and Critiques of the Pragmatic Theory of Properhood.” Onoma 41: 27–44.

- Coates, Richard. 2009. “A Strictly Millian Approach to the Definition of the Proper Name.” Mind & Language 24, no. 4: 433–444.

- Colman, Fran. 2014. The Grammar of Names in Anglo-Saxon England: The Linguistics and Culture of the Old English Onomasticon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Corbett, Greville G. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eichler, Ernst, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger, and Ladislav Zgusta, eds. 1995. Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics, vol. 1. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Ghomeshi, Jila, and Diane Massam. 2005. “The Dog, the Moon, The Hague, and Canada.” In Proceedings of the 2005 Canadian Linguistics Association Annual Conference, edited by Claire Gurski, 1–12. http://cla-acl.ca/actes-2005-proceedings/.

- Ghomeshi, Jila, and Diane Massam. 2009. “The Proper D Connection.” In Determiners: Universals and Variation, edited by Jila Ghomeshi, Ileana Paul, and Martina Wiltschko, 67–95. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gregory, Ian N., and Andrew Hardie. 2011. “Visual GISting: Bringing Together Corpus Linguistics and Geographical Information Systems.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 26, no. 3: 297–314.

- Greule, Albrecht. 1995. “Methoden und Probleme der corpusgebundenen Namenforschung.” [Methods and problems of corpus-based name research]. In Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics, edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger, and Ladislav Zgusta, vol. 1, 339–344. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Hayn, Evelyn. 2016. You Name It?! Everyday Discrimination Through Accustomed Perception of Personal Names. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität.

- Hewson, John. 1972. Article and Noun in English. The Hague: Mouton.

- Horowitz, Franklin E. 1990. “ESL and Prototype Theory: Zero vs. Definite Article with Place Names.” In Grammatical Studies in the English language, edited by Dietrich Nehls, 95–112. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

- Jespersen, Otto. 1954. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VII: Syntax. Copenhagen: Einar Munksgaard.

- Kałuża, Henryk. 1968. “Proper Nouns and Articles in English.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 6, no. 1–4: 361–366.

- Kjellmer, Göran. 2002. “The Britain: An Unexpected Case of Article Usage in Present-Day English.” In From the COLT’s Mouth – and Others’: Language Corpora Studies in Honour of Anna-Brita Stenström, edited by Leiv Egil Breivik and Angela Hasselgren, 167–180. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Kripke, Saul. 1980. Naming and Necessity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Laversuch, Iman M. 2010. “Margarete and Sulamith Under the Swastika: Girls’ Names in Nazi Germany.” Names 58, no. 4: 219–230.

- Long, Ralph B. 1969. “The Grammar of English Proper Names.” Names 17, no. 2: 107–126.

- Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics: Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Matushansky, Ora. 2006. “Why Rose is the Rose: On the Use of Definite Articles in Proper Names.” Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 6: 285–307.

- McEnery, Tony, and Andrew Hardie. 2012. Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory, and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Motschenbacher, Heiko. 2018. “Corpus Linguistics in Language and Sexuality Studies: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead.” Journal of Language and Sexuality 7, no. 2: 145–174.

- Motschenbacher, Heiko. 2019. “Discursive Shifts Associated with Coming Out: A Corpus‐Based Analysis of News Reports About Ricky Martin.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 23, no. 3: 284–302.

- Motschenbacher, Heiko. 2020. “Greece, the Netherlands and (the) Ukraine: A Corpus-Based Study of Definite Article Use With Country Names.” Names 68, no. 1.

- Nick, Iman M. 2017. “Squaw Teats*, Harney Peak, and Negrohead Creek*: A Corpus-Linguistic Investigation of Proposals to Change Official US Toponymy to (Dis)Honor Indigenous US Americans.” Names 65, no. 4: 223–234.

- Nyström, Staffan. 2016. “Names and Meaning.” In The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming, edited by Carole Hough, 39–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oelke, Daniela, Dimitrios Kokkinakis, and Mats Malm. 2012. “Advanced Visual Analytics Methods for Literature Analysis.” In Proccedings of the 6th Workshop on Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities (LaTeCH 2012), edited by Kalliopi Zervanou and Antal van den Bosch, 35–44. Stroudsburg, PA: Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. Harlow: Longman.

- Schlücker, Barbara, and Tanja Ackermann. 2017. “The Morphosyntax of Proper Names: An Overview.” Folia Linguistica 51, no. 2: 309–339.

- Schnabel-Le Corre, Betina. 2014. “Nouns and Noun Phrases as Modifiers in Complex Toponyms: Structure, Function and Use in German, English and Swedish.” In Names in Daily Life: Proceedings of the XXIV ICOS International Congress of Onomastic Sciences. Annex: Secció 6, edited by Joan Tort i Donada and Montserrat Montagut i Montagut, 1427–1435. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya.

- Seppänen, Aimo. 1982. Restrictive Modification and Article Usage with English Proper Names. Umea: Umea University.

- Sørensen, Holger Steen. 1963. The Meaning of Proper Names with a Definiens Formula for Proper Names in Modern English. Copenhagen: GEC GAD.

- Ström Herold, Jenny, and Magnus Levin. 2019. “The Obama Presidency, the Macintosh Keyboard and the Norway Fiasco: English Proper Noun Modifiers and their German and Swedish Correspondences.” English Language and Linguistics 23, no. 4: 827–854.

- Tse, Grace Y. W. 2000. “Pedagogical Implications of Prototype Theory for the Writing of English Grammar Textbooks: The Case of Proper Names.” In 13th International Symposium on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics: Proceedings, edited by Katerina Nicolaidis and Marina Mattheoudakis, 490–500. Thessaloniki: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

- Tse, Grace Y. W. 2003. “Validating the Logistic Model of Article Usage Preceding Multi-Word Organization Names with the Aid of Computer Corpora.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 18, no. 3: 287–313.

- Tse, Grace Y. W. 2004. “A Grammatical Study of Personal Names in Present-Day English: With Special Reference to the Usage of the Definite Article.” English Studies 85, no. 3: 241–259.

- Tse, Grace Y. W. 2005. A Corpus-Based Study of Proper Names in Present-Day English: Aspects of Gradience and Article Usage. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- van Dalen-Oskam, Karina. 2012. “Personal Names in Literature: A Quantitative Approach.” In Facts and Findings on Personal Names: Some European Examples, edited by Lars-Gunnar Larsson and Staffan Nyström, 153–168. Uppsala: Kungliga Vetenskapssamhället.

- van Dalen-Oskam, Karina. 2013. “Names in Novels: An Experiment in Computational Stylistics.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 28, no. 2: 359–370.

- van Dalen-Oskam, Karina. 2016. “Corpus-Based Approaches to Names in Literature.” In The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming, edited by Carole Hough, 344–354. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Dalen-Oskam, Karina, and Joris van Zundert. 2004. “Modelling Features of Characters: Some Digital Ways to Look at Names in Literary Texts.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 19, no. 3: 289–301.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 1998. “A Typological Approach to Place-Name Categories.” In Scope, Perspectives and Methods of Onomastics: Proceedings of the XIXth International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Aberdeen, August 4–11, 1996, edited by Wilhelm F. H. Nicolaisen, vol. 1, 342–348. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2004. “Proper Names and Forms of Iconicity.” Logos and Language 5, no. 2: 15–30.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2005. “Proper Names and Proprial Lemmas.” In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Onomastic Sciences (Uppsala, 19–24 August 2002), edited by Eva Brylla and Mats Wahlberg, vol. 1, 315–323. Uppsala: Språk- och Folkminnesinstitutet.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2007. Theory and Typology of Proper Names. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- van Langendonck, Willy, and Mark van de Velde. 2016. “Names and Grammar.” In The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming, edited by Carole Hough, 17–38. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vandelanotte, Lieven, and Peter Willemse. 2002. “Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Modification of Proprial Lemmas.” Word 53, no. 1: 9–36.

- Vartiainen, Turo. 2019. “From Twig-Skinny to Kate Moss Skinny: Expressing Degree With Common and Proper Nouns.” English Language and Linguistics 23, no. 4: 901–927.

- Vuillemot, Romain, Tanya Clement, Catherine Plaisant, and Amit Kumar. 2009. “What’s Being Said Near ‘Martha’? Exploring Name Entities in Literary Text Collections.” In IEEE Symposium on Visual Analytics Science and Technology, 2009: Proceedings, edited by John Stasko and Jarke J. van Wijk, 107–114. Piscataway, NJ: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

- Zinkin, Vivian. 1969. “The Syntax of Place-Names.” Names 17, no. 3: 181–198.