Abstract

This study investigates the grammatical behavior of English country names based on corpus linguistic evidence. An overview of the basic patterns of definite article use with country names as commonly described in English reference grammars and of the morphological structures of English country names is presented. Against this backdrop, the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) is used to explore which (groups of) country names occur more or less frequently with a definite article. The data analysis reveals that virtually all of the English country names examined are, to some extent, used in the syntactic position following a definite article. It is shown that certain grammatical constructions call for the use of a definite article in connection with country names. However, the morphology of the country names also has a strong influence on how often they are used with a definite article. Furthermore, it is argued that the minority of English country names that do not fit this morphological pattern may differ because they derive from other place name types that generally take a definite article.

1. Introduction: English country names – Definite article use and morphology

Basic descriptions of article use with English country names, typically found in earlier linguistic treatises or reference grammars (such as Jespersen Citation1954, 545; Quirk et al. Citation1985, 296), tend to be restricted to the following “rules”:

English country names do not take a definite article.

There are certain systematic exceptions: plural names (e.g. the Netherlands), name phrases involving a classifier noun (e.g. the Czech Republic), and abbreviations (e.g. the USA).

For the small group of country names that allow for variation, the unmarked variant without definite article (Ukraine) is usually preferred (vs. the Ukraine).

While these rules capture central aspects of the use of the definite article with country names, they obscure the relatively high degree of variability we find in concrete usage data. Whilst most place name groups exhibit a dominant pattern of absence or presence of a definite article, country names are associated with a higher degree of variability in this respect.

Moreover, English country names are also structurally highly heterogeneous and may exhibit any of the following basic morphological structures:

Category 1: Monomorphemic forms (zero marking): Greece, Japan, Spain, Zimbabwe

Category 2: Suffixed forms: German-y, Slovak-ia, Afghan-istan, Chin-a

Category 3: Names with a preposed definite article: the Congo, the Ukraine, the Vatican

Category 4: Names incorporating a classifier noun (and a definite article): the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, the United States

Category 3 is the major target of this study. It represents a challenging category, as article-based usage patterns are not stable. There is hardly any country name that demonstrates a set behavior regarding definite article usage, either appearing invariably with or without an article. This study sets out to identify which country names show the highest article usage rates and therefore qualify as members of Category 3. There are some country names that have been described as varying to a larger extent between unmarked use and use with a definite article in the earlier research literature (e.g. Cameroon, Gambia, Lebanon, Sudan, Ukraine, Yemen; Millar Citation1996; Tse Citation2005, 62–65). These can be deemed potential candidates for Category 3 status.

Category 4 contains compounds with a classifier head noun, for example in combination with a nationality adjective (Czech Republic, Soviet Union) or other descriptive forms (Ivory Coast, United Kingdom). Within this group, country names that consist exclusively of descriptive, non-proper material may be thought to rely more heavily on individuation through the definite article, with the latter being crucial for marking proper name status (the United Kingdom; the United States vs. a united kingdom; united states).

Definite articles that co-occur with English country names are not “fossilized determiners” (van Langendonck Citation2007, 122), as they are in certain contexts replaceable by other determiners (this Vatican) and can be separated from the name through intervening adjectives (the modern Vatican). They are, therefore, not an intrinsic part of the country name itself (as in the city name The Hague).

Viewed historically, country names that are commonly used with a definite article are likely to develop toward higher rates of article dropping. This is due to the fact that nation building is a relatively recent phenomenon that, in general, took place after the evolution of the geographical names on which country names are often based. The gradual dropping of the article can be explained as a process of increasing human association of a geographical entity through nation building and political institutionalization. In other words, names that originally identified geographical entities with a limited sense of humanization (such as rivers, regions, mountain ranges, etc.) gradually drift formally toward Categories 1 or 2. For example, the name Lebanon originally stood for a mountain range, Congo for a river, Ukraine for a region. This extension of geographical names to country names is a common pattern (see Back Citation1996, 1350–1351).1

Another mechanism that is likely to support such developments is analogical language change. As most English country names are normally used without a definite article, this exerts a certain pressure on country names that commonly co-occur with a definite article to drop it. Furthermore, such a development echoes a wider trend in English to drop definite articles in contexts where their use is redundant or felt to be unnecessary (see Rastall Citation1995).

With those country names that show variation, the unmarked variant is usually considered preferable, as it is normally free of undesirable associations that the article-marked version may possess. Using a country name with a definite article is often perceived to point back to times before the respective geographical entity became an independent nation and may therefore possess a colonial or outdated flavor (e.g. the Congo, the Ukraine; see Piotrowski Citation1998).

Linguistic work that focuses on country names is scarce and in general restricted to small-scale studies. Most of this research has neither analyzed the specific grammatical patterns of country names (vs. other place-name types, for example) nor has it drawn on data from major English reference corpora. Typical examples are Berezowski (Citation1999) and Millar (Citation1996), who do not provide systematic accounts of the grammatical usage patterns of country names but merely discuss some individual names in isolation from the syntactic context. Millar (Citation1996) states that English country names that take the definite article fall into two groups: plural names (island groupings: the Bahamas, the Comoros etc.; unions of regions: the Netherlands, the United States etc.) and names referring to a specific form of government (e.g. the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom). He also notes that many of the country names that take a definite article have alternative articleless designations that are generally used in informal modes of communication, although strictly speaking they may not refer to exactly the same territory (e.g. Holland, America, Britain).

Berezowski (Citation1997, 134) postulates an “iconic principle” (following Hewson Citation1972), which stipulates that the place name types that do not take a definite article are associated with geographical entities that have well defined boundaries, while the definite article is used with the other place name groups “to lend form to otherwise formless referents” (Berezowski Citation1997, 131). Such reasoning, however, is not entirely convincing, as it is hard to see why, for example, rivers should be treated as less well bounded than cities or bays. Berezowski (Citation1999) adduces individual examples as (shaky) evidence that definite article use with country names is also guided by this iconic motivation. This claim remains dubious, since all countries can be assumed to be associated with a similar (perceived) degree of boundedness.

In addition, one finds two small-scale corpus-based studies that focus on country names. The first one, by Piotrowski (Citation1998), deals with the development from the Ukraine to Ukraine in American English, drawing on a corpus of Time Magazine issues. The author shows that the dropping of the definite article coincides with the historical development of Ukraine toward an independent nation in 1991. The second study by Kjellmer (Citation2002) explores the use of the string the Britain in various corpora such as the Cobuild Corpus and the BNC. It finds that, although this phrase looks like non-standard or erroneous language use on the surface, there are certain usage patterns that are in accordance with standard usage (constructions in which the country name functions as a premodifier or is postmodified by a prepositional phrase or restrictive relative clause: the Britain Visitor Centre; the Britain of his youth; the Britain that Queen Victoria reigned over; Kjellmer 2002, 168). Furthermore, Kjellmer uses the Cobuild Corpus to identify a number of singular country names that, contrary to the majority of country names, sometimes take a definite article (Congo: 28.4%, Gambia: 35.2%, Lebanon: 28.2%, Sudan: 17.7%, Ukraine: 48.1%; Kjellmer 2002, 171). Among the “unexpected,” non-standard uses of singular country names with the, Kjellmer finds that many of them are genitives (the Peru’s, the Turkey’s etc.), whose (weak) propensity to take a definite article may be influenced by the fact that genitive forms are homophonous with plural forms, which in general take a definite article (the Netherlands, the Seychelles). Another usage pattern involves the use of country names with a definite article to metonymically refer to a national sportsteam (the Ireland “the Irish team,” the Portugal “the Portuguese team”).

2. Methodological considerations

This study starts from the less traditional hypothesis that all country names show some degree of variation in article usage and seeks to shed light on the factors that may be responsible. It draws on corpus data to investigate the syntactic behavior of country names. As it is expected that country names in actual language use regularly exhibit grammatical patterns that deviate from standard-conforming language use, corpus linguistics seems a particularly apt method for this purpose. Another option would have been to conduct surveys asking native speakers of English how they would use certain country names. Such a procedure, however, is of limited value, as it is likely to elicit norm-conforming linguistic behavior to the detriment of non-standard language use, which subjects would normally either judge to be unacceptable or not cite at all. An analysis of corpus data, by contrast, can produce a richer picture of the linguistic variation that actually occurs.

The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) is used as the dataset for this study. At the time of writing, this corpus contains 520 million words of American English language use in the text categories spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers and academic texts, covering the years 1990 to 2015 (Davies Citation2009, Citation2010).

The question of definite article use in connection with names can be explored on four levels, ranging from broad to more specific research questions:

Which name types (personal names, place names, etc.) take a definite article and which do not?

Which place name types (settlement names, country names, river names etc.) take a definite article and which do not?

Which (groups of) country names take a definite article and which do not?

Under which circumstances does a country name with variable behavior take a definite article?

The limited number of studies and grammatical descriptions that exist concentrate mainly on levels 1 and 2, that is, they discuss which semantically based name types are used with or without a definite article (e.g. Seppänen Citation1982; Quirk et al. Citation1985, 290–291; Horowitz Citation1990; Tse Citation2005).

This study, by contrast, focuses on levels 3 and 4, revealing the grammatical patterns exhibited by country names more specifically. A concentration on country names can be legitimated in three ways: 1. by the high degree of variability this particular place-name group shows, 2. by the fact that country names are less prototypical in their grammatical behavior than other frequently used name types (personal and settlement names), and 3. by the methodological issue that concentrating on a specific place-name type helps the analyst to control for the meaning of names as a potential factor affecting definite article use.

As the corpus linguistic procedure has to rely on linguistic forms to detect names in a corpus by means of a retrieval tool, it is important to note that what is identified by such searches is, strictly speaking, not properhood-related information, but information on the usage of particular “proprial lemmas” (van Langendonck 2005), i.e. forms that are typically used in an onymic function. As country names do not show any consistent formal features that could be exploited in a corpus search query to yield all instances of such names (see Tse Citation2005, 9; Anderson Citation2007, 170), search queries had to be based on individual country names, which proves feasible because country names form a finite set. For this purpose, a list of all currently existing countries was compiled and complemented by names of countries that still existed in the early 1990s (for example, Czechoslovakia, FRG, GDR, USSR, Yugoslavia) and former names of countries which have undergone a name change since that time (for example, Burma, Zaire). This was deemed necessary because the COCA data partly consist of material from the 1990s. For some country names that are ambiguous between proper name and other usages (chad, china, turkey, us vs. Chad, China, Turkey, US), a proper noun part of speech tag (_np*) was added in the search query to make sure that only names are retrieved. For country names that consist of two territorial names, only the first of these two names was tested (e.g. Bosnia instead of Bosnia Herzegovina; Trinidad instead of Trinidad and Tobago). Only the names of a few countries were tested in various forms (e.g. Argentina, Argentine; Britain, Great Britain; Burma, Myanmar; Cote d’Ivoire, Ivory Coast; Korea, North Korea, South Korea; UK, United Kingdom; US, USA, United States).

First, the general frequencies of all country names were identified by searching for them individually. Country names that occurred less than a hundred times in COCA (such as Andorra, Kiribati, Nauru, Tuvalu) were excluded. This leaves us with a list of 200 remaining country names. In a second step, searches for combinations of these country names with a definite article (the Greece, the Ukraine etc.) were carried out.2 With the frequencies retrieved by the two initial queries, the percentage of article use for a given country name was calculated. For some country names, concordance lines of the usages with a definite article were inspected in order to detect grammatical contexts that make article usage more likely.

To relate article usage to name morphology, a structural classification of country names was carried out, distinguishing the morphological Categories 1, 2 and 4, as described in Section 1. Two more categories were included in the morphological categorization, covering names whose structures are not covered by these three categories. Category 5 refers to compounds that consist of a proper noun head and an adjectival specifier (e.g. North Korea, South Africa). Such compounds differ from the name compounds in Category 4 in that they do not incorporate a classifier noun. Category 6 groups together all abbreviations (initialisms such as UK, USSR).

3. Corpus-based analysis of definite article use with country names

3.1. Frequency of morphological structures in the country name sample

A substantial number of the English country names in the sample are morphologically unmarked or monomorphemic. Out of the 200 country names included, 33.5% (67) belong to this group. Suffixed forms account for 104 out of 200 country names (52.0%). Suffix status was determined through contrastive analysis of the country names with morphologically related forms showing identical “proprial stems” (van Langendonck Citation2007, 98). These were often national adjectives, nouns denoting the inhabitants of a country or a language stereotypically associated with a country (for example, -y can be considered a suffix because it conveys the meaning “country” in German-y, in contrast to forms like German-Ø or German-ic). Various suffixes are available for country name formation, including -y (German-y, Hungar-y, Ital-y), -ia (Alban-ia, Bulgar-ia, Slovak-ia), -(i)stan (Afghan-istan, Kazakh-stan, Uzbek-istan), -o (Mexic-o, Montenegr-o) and -a (Burm-a, Canad-a, Chin-a).3 One may also consider the plural suffix -s as a morpheme that is used to form country names, i.e. names of countries that consist of several entities (islands, states etc.; Maldives, Netherlands, Philippines).

The component -land (Fin-land, Swazi-land, Thai-land) may look like a potentially free morpheme in the written medium (which, in turn, would suggest compound status), but the pronunciation of this element differs from that of the noun land ([laend]) in its weakened vowel ([lənd]). Furthermore, there is also a difference in meaning involved (van Langendonck Citation2004, 28). While the reduced form carries the political meaning “country,” the meaning of the noun land is not tied to any form of political organization but rather denotes any wider geographical space. Another piece of evidence that speaks in favor of suffix status is that, for an alternative interpretation as a root, land would have to be considered a classifier noun, and the respective country names representatives of Category 4 rather than 2. However, as we will see later in the analysis, country names ending in -land overwhelmingly do not take a definite article. This indicates that they are more compatible with Category 2.

3.2. Frequency of article-based uses

The frequencies retrieved for article-based country name usage show that the rule that country names do not co-occur with a definite article (see, for example, Quirk et al. Citation1985, 291, 293) is an abstraction or oversimplification, since all but one country name occur with a definite article in COCA (the only exception being Latvia). Similarly, there is no country name that is always used with a definite article. This can be explained through certain contexts where even country names that show a strong inclination to have a definite article may drop it, for example in coordination (the relationship between United States and Israel; COCA) or in headlines (United States to pay $28 million to China; COCA) (see Seppänen Citation1982, 1).

When looking at the percentages of the article-based uses (), one finds that for most country names, the percentaged figures are small. Almost 74% of the country names (148 out of 200) are used following a definite article in less than 4% of their occurrences. The largest group of country names (76) shows percentages below 1%, and one finds a steady decline up to the 50% level. The number of country names stays fairly constant thereafter and only rises back to ten at the 80% level.

Table 1 Distribution of country names in relation to definite article use

The highest occurrence rates with a definite article are shown by three morphologically based groups of country names: plural forms (Type 1: Bahamas, Netherlands, Philippines, Seychelles), name compounds that incorporate a classifier noun (Type 2: Central African Republic, Czech Republic, Dominican Republic, Soviet Union, United Kingdom), and abbreviations (Type 3: FRG, GDR, UK, USSR). Some names are both plural and incorporate a classifier noun, thus combining Types 1 and 2 (Marshall Islands, United Arab Emirates, United States). Type 3 names are, in principle, similar to Type 2 names, as the full forms of the abbreviations contain classifier nouns (Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, United Kingdom, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). It can be concluded that, for the country names that show the highest article frequencies, name morphology causes this pattern. This explains the behavior of all names that show more than 54% article use, as well as that of some that show lower, but still substantial, frequencies (Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, US., USA). Note that none of the country names that belong to Types 1 to 3 show a percentage lower than 22.5%.

It is the behavior of the country names that occur less frequently but still substantially (i.e. with a rate of more than 20%) with a definite article that is more difficult to explain. In this group, two names (Argentine, Vatican) could be considered as related to Type 2, because they can be explained in terms of an omitted classifier noun (the Argentine Republic, the Vatican State). This leaves us with three more names that show an article usage rate of more than 20.0%: Gambia, Congo and Uruguay. Interestingly, these are all originally river names that have later been used to designate a country. It may, therefore, not be surprising that they show higher article frequencies, since river names in English are generally used with a definite article (the Rhine, the Nile, the Thames etc.). In fact, the corpus search queries cannot distinguish between country- and river-related usages. It must, therefore, be assumed that the actual country name usages account for lower percentages. Also note that some names that have been highlighted as article-prone by earlier research show remarkably low percentages (Cameroon 4.9%, Lebanon 1.5%, Sudan 16.5%, Ukraine 14.0%, Yemen 2.0%). This may be the case because their morphology does not support article usage.

3.3. A closer look at article-based uses

Note that the percentages of article use identified in Section 3.2 do not just cover contexts in which definite article use with country names is a marked choice or non-standard usage. Even for country names outside Types 1 to 3, there are a number of grammatical constructions in which article use is normatively required. An inspection of the concordance lines of such country names when they are preceded by a definite article reveals that the six grammatical contexts illustrated in normally require a definite article.

Table 2 Grammatical contexts requiring the use of a definite article with country names

There are potentially more relevant constructions than those illustrated in , but these six constructions turn out to be the most common. Type A refers to cases in which the country name forms the initial component within a nominal compound, that is, the country name is followed by a noun (e.g. the Iraq War). In Type B, the country name modifies a compound that consists of an adjective and a noun, that is, it stands before an adjective (e.g. the Iraq National Museum). Type C unites cases in which the country name forms a component within a complex compound in which the modifying element consists of two coordinated noun phrases (often two country names; e.g. the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts). Type D groups together cases in which a country name is postmodified by a prepositional phrase (e.g. the Iraq of our dreams). Type E describes cases in which the country name is postmodified by a restrictive relative clause introduced by the relativizer that (e.g. the Iraq that was there…). Finally, Type F refers to country names postmodified by a restrictive objective relative clause with an empty relativizer and introduced by a subject pronoun (e.g. the Iraq he knows).

Within the six types, one can distinguish two larger subgroups: compounds in which the country name forms (part of) a specifier (Types A–C), and cases where the country name is followed by a restrictive modifier (Types D–F). These two groups should be kept apart, as only the first group is a matter of semantic properhood, while the cases in the second group cover contexts in which the proper noun is used as a common noun with an appellativized “type of” meaning (see Quirk et al. Citation1985, 290; Vandelanotte and Willemse Citation2002, van Langendonck Citation2007, 124–125). For example, the Iraq of our dreams denotes just one “Iraq type,” as opposed to the real Iraq or the Iraq of the past etc. Furthermore, only the second group actually contains cases in which it is the country name that takes a definite article, while the first group contains constructions in which the article gives definiteness to (non-country-denoting) compounds in which the country name is merely a specifier.

To arrive at a more precise picture of which country names favor definite article use, it was decided to exclude the six construction types in , because they represent contexts in which all country names are used with a definite article. It was then determined how many of the article-based usages of a certain country name do not fall into any of these six construction categories. For the purpose of this study, only those country names that occur with a definite article at least 25 times in COCA (115 in total) were selected.

We can see in that the three morphologically based groups of country names identified above (plural names, names incorporating a classifier noun, abbreviations) again show the highest percentages. This confirms once more that these morphological features trigger article use independently of grammatical context. However, there are some other names that show a relatively high percentage even though they do not belong to any of these three groups. These names include Ukraine (73.5%), Vatican (72.3%), Gambia (71.7%), Sudan (68.9%), Congo (65.5%), and Cote d’Ivoire (55.2%). They regularly seem to take a definite article, even in grammatical contexts where it is not called for (that is, contexts other than Construction Types A to F). illustrates such usages.

Table 3 Percentages of definite article use with country names outside construction types A–F

Table 4 Illustrations of definite article use with country names outside construction types A–F

It is interesting to note that most of the country names that show percentages between 30.0% and 39.9% contain a set of special cases in which the name in question does not refer to a country. For example, the France (39.3%) and the Trinidad (39.5%) include several cases in which reference is made to a ship, or the Jordan (31.1%) and the Niger (30.4%) are often used to refer to the river of the same name. The combination the Turkey (31.3%) reaches a higher percentage because some cases of Turkey have been mis-tagged as proper nouns in the corpus, even though they refer to an animal. As these names have, in principle, lower frequencies, there seems to be a clear usage gap of around 50%, with most country names clustering clearly below that line, and 27 out of 115 names (23.5%) showing higher article usage rates.

3.4. Distribution of definite articles across morphological country name categories

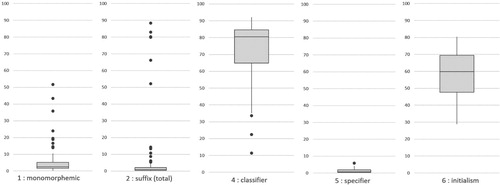

When relating the analysis to the five morphological categories established in Section 2, one finds that these are associated with definite article use to varying extents. presents boxplots for the five categories. The boxes cover the second and third quartile of the data, with the dividing line between the two boxes marking the median. The length of the whiskers is maximally 1.5 times the length of the box. They serve to define those country names that lie above or below them as outliers.

One can see that the highest level of definite article use is associated with compounds involving a classifier noun (median: 80.6%). Within this group, there are also three outliers with somewhat lower frequencies: Cote d’Ivoire (11.4%), Cape Verde (22.5%), and Ivory Coast (33.6%). Cote d’Ivoire and Cape Verde show relatively unusual morphological patterns for English, as the classifier noun stands at the beginning of the compound. The lower percentage of Ivory Coast may be due to analogical pressure from Cote d’Ivoire, which refers to the same country. Another group of country names that is associated with higher frequencies of definite article use is Category 6: initialisms. The median lies at 59.9% and there are no outliers in this category, which attests to its internally homogeneous behavior.

Among the remaining three categories, definite article use is the exception rather than the rule. The smallest median values are exhibited by Category 2, suffixed names, and Category 5, compounds with specifiers (both 0.8%). However, while Category 5 is internally fairly homogeneous, with just one minor outlier (New Zealand: 5.8%), Category 2 shows a relatively large group of outliers that behave quite differently from the rest of the group in that they are associated with clearly higher levels of definite article use. Five of these outliers show frequencies of higher than 65.0%. All of these are plural forms (Seychelles: 66.2%, Maldives: 79.8%, Netherlands: 80.2%, Bahamas: 83.0%, Philippines: 88.3%). Another suffixed form that shows 52.1% definite article use is Gambia. All other outliers show percentages lower than 15%.

A slightly higher tendency of occurrence with a definite article is documented by Category 1: monomorphemic names. The median value is 2.5% in this category, and there are nine outliers with higher frequencies ranging from 14.0% up to 51.7% (Vatican: 51.7%, Congo 43.4%, Argentine: 35.8%, Uruguay: 24.0%, Vietnam: 19.5%, Niger: 18.8%, Sudan: 16.5%, Palestine: 14.5%, Ukraine: 14.0%).

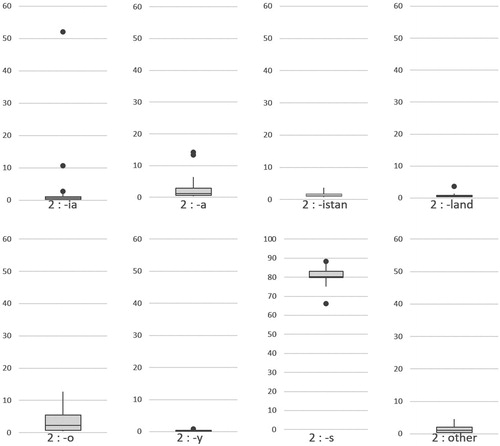

presents boxplots documenting the definite article distribution among the various subgroups of suffixed country names. As has been noted above, the plural formations stand out through their high percentages. If one orders the remaining suffixes from lowest to highest median, one finds that the suffix that avoids article use the most is -y (0.2%), followed by -ia (0.7%), -land (0.7%), other (1.1%), -istan (1.1%), -a (1.2%), and -o (2.3%). There are remarkably few outliers among these seven suffix groups (those of 10% or higher are restricted to two cases ending in -ia and two ending in -a; Georgia: 10.7%, Gambia: 52.1%, Panama: 13.3%, Tonga: 14.2%).

4. Conclusion

This research suggests that corpus linguistics is a useful methodology for the investigation of the grammatical patterns exhibited by proper names in actual language use. Based on corpus linguistic evidence, it shows that name morphology exerts a strong influence on definite article use with country names in American English. Plural names (Netherlands, Seychelles), compound names incorporating a classifier noun (Czech Republic, United Kingdom), and initialisms (GDR, USSR) are associated with the highest article usage rates. By contrast, suffixed country names other than plural formations (Germany, Russia), compound names incorporating specifiers (North Korea, South Africa), and monomorphemic country names (Greece, Norway) possess morphological structures that widely block the use of a definite article. This may be due to the stronger semantic connection of these structures to individuation, while for the other three structure types individuation is compromised to some extent by a collective meaning that calls for individuation through the use of a definite article (plural forms refer to groups of entities; classifier nouns denote a generic category; abbreviations can be ambiguous, and the full forms of country initialisms generally contain a classifier noun). Among the country names that flout these patterns, many can be explained through the origin of the name, which may ultimately be a name of another geographical formation that is less humanized and has been extended to designate a country as part of nation-building processes (such as a river: Congo, Gambia, Niger, Uruguay). Others can be explained in terms of an omitted classifier noun (Argentine, Vatican).

For future research, it would be interesting to study other varieties of English and to conduct cross-linguistic comparisons. In German, for example, article use with country names seems to be strongly connected to the grammatical gender and number of the name, with grammatically feminine and masculine (die Schweiz, die Türkei; der Iran, der Kongo) and plural names (die Niederlande, die Bahamas) being systematically used with a definite article, while the majority of country names, which are grammatically neuter (Russland, Schweden), are generally used without article (see Berger Citation1996; Thieroff Citation2000), except when used in certain grammatical constructions (das Schweden der 70er Jahre “the Sweden of the 70s,” das Russland, das wir besuchten “the Russia that we visited”). The fact that French country names systematically take a definite article (la France, le Mexique; Haschka Citation1989) and are not generally suffixed formations indicates that the definite article in French country names may take over the individualizing function that is in other language fulfilled by suffixes (van Langendonck Citation1998, 342–343).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Other examples: Chad, Gambia, Jordan, Niger, Senegal (rivers and lakes); Mexico, Mozambique (settlements); Trinidad (personal name); Sudan (population).

2 Note that this procedure ignores cases in which one or several adjective phrases stand between the definite article and the country name (e.g. the new Greece).

3 Country names that show non-English morphological patterns (Bo-tswana, Bu-rundi) are likely to be perceived as monomorphemic by English native speakers and were classified accordingly.

Bibliography

- Anderson, John M. 2007. The Grammar of Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Back, Otto. 1996. “Typologie der Ländernamen: Staaten-, Länder-, Landschaftsnamen.” [Typology of Country Names: State, Country and Areal Names]. In Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics: Volume 2, edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger and Ladislav Zgusta, 1348–1356. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Berezowski, Leszek. 1997. “Iconic Motivation for the Definite Article in English Geographical Proper Names.” Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 32: 127–144.

- Berezowski, Leszek. 1999. “Going, Going, Gone? The Future History of the Definite Article in English Names of Countries.” Anglica Wratislaviensia 34: 41–55.

- Berger, Dieter. 1996. “Morphologie und Wortbildung der Ländernamen.” [Morphology and Word Formation of Country Names] In Name Studies: An International Handbook of Onomastics: Volume 2, edited by Ernst Eichler, Gerold Hilty, Heinrich Löffler, Hugo Steger and Ladislav Zgusta, 1356–1360. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Davies, Mark. 2009. “The 385+ Million Word Corpus of Contemporary American English (1990–2008+): Design, Architecture, and Linguistic Insights.” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 14, no. 2: 159–190.

- Davies, Mark. 2010. “The Corpus of Contemporary American English as the First Reliable Monitor Corpus of English.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 25, no. 4: 447–464.

- Haschka, Christine. 1989. “Genus- und Artikelgebrauch bei Ländernamen im Französischen und Deutschen.” [Gender and article usage with country names in French and German]. Lebende Sprachen 34, no. 2: 73–75.

- Hewson, John. 1972. Article and Noun in English. The Hague: Mouton.

- Horowitz, Franklin E. 1990. “ESL and Prototype Theory: Zero vs. Definite Article with Place Names.” In Grammatical Studies in the English Language, edited by Dietrich Nehls, 95–112. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

- Jespersen, Otto. 1954. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VII: Syntax. Copenhagen: Einar Munksgaard.

- Kjellmer, Göran. 2002. “The Britain: An Unexpected Case of Article Usage in Present-Day English.” In From the COLT’s Mouth – and Others’: Language Corpora Studies in Honour of Anna-Brita Stenström, edited by Leiv Egil Breivik and Angela Hasselgren, 167–180. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Millar, Robert McColl. 1996. “‘Why is Lebanon called the Lebanon?’: Some Suggestions for the Grammatical and Sociopolitical Reasonings Behind the Use or Non-Use of the with the Names of Nation States in English.” Notes and Queries 43, no. 1: 22–27.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz. 1998. “Changing Usage in American English: The Case of (the) Ukraine.” Anglica Wratislaviensia 33: 147–154.

- Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. Harlow: Longman.

- Rastall, Paul. 1995. “Definite Article or No Definite Article?” English Today 11, no. 2: 37–39.

- Seppänen, Aimo. 1982. Restrictive Modification and Article Usage with English Proper Names. Umea: Umea University.

- Thieroff, Rolf. 2000. “*Kein Konflikt um Krim: Zu Genus und Artikelgebrauch von Ländernamen.” [*No Conflict Around Crimea: On Gender and Article Use of Country Names]. In Botschaften verstehen: Kommunikationstheorie und Zeichenpraxis. Festschrift für Helmut Richter, edited by Helmut Richter, Ernest W. B. Hess-Lüttich and H. Walter Schmitz, 271–284. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Tse, Grace Y. W. 2005. A Corpus-Based Study of Proper Names in Present-Day English: Aspects of Gradience and Article Usage. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 1998. “A Typological Approach to Place-Name Categories.” In Scope, Perspectives and Methods of Onomastics: Proceedings of the XIXth International Congress of Onomastic Sciences, Aberdeen, August 4–11, 1996. Volume 1, edited by Wilhelm F. H. Nicolaisen, 342–348. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2004. “Proper Names and Forms of Iconicity.” Logos and Language 5, no. 2: 15–30.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2005. “Proper Names and Proprial Lemmas.” In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Onomastic Sciences (Uppsala, 19–24 August 2002), edited by Eva Brylla and Mats Wahlberg, vol. 1, 315–323. Uppsala: Språk- och Folkminnesinstitutet.

- van Langendonck, Willy. 2007. Theory and Typology of Proper Names. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Vandelanotte, Lieven, and Peter Willemse. 2002. “Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Modification of Proprial Lemmas.” Word 53, no. 1: 9–36.