ABSTRACT

With increasing pressure on versatile land for development, the odds appear stacked against protecting this diminishing resource. Unlike development, however, certain food provision is limited to versatile land. In deciding where development and preservation of land for food production should occur, it is critical to identify explicit trade-offs. Yet, little research addresses how these decisions, effectively irreversible, affect a food system for society and future generations. This article reviews recent opportunities and advancements that may help inform science-based policies on these matters, as well as suggesting directions for future research. It revisits the need for a national policy statement on protecting versatile land, a conversation dating back to 1996. The land and soil science community have a responsibility to raise awareness on the collective benefit of protecting this resource and progress its protection in national policy. The alternative may see us repeating the same conversation in another 20 years’ time, the only difference may be the amount of resource remaining.

Introduction

Land is becoming an increasingly contested resource as multiple uses compete for finite areas. Increasing populations, both within New Zealand and globally, expect terrestrial ecosystems to provide sufficient food as well as places to live (Tóth Citation2012; Skog and Steinnes Citation2016), not to mention a plethora of other ecosystem services.

Not all land is equally suited to every end use, however, leading to competition for small areas of high class, versatile land. Versatile land has negligible or minor physical limitations for arable use, typically the product of unique inherent land and soil characteristics and favourable climatic conditions and, therefore, capable of a wide variety of highly productive rural land uses. This finite resource provides many ecosystem services, a few of which (including food provision such as outdoor vegetable production) are limited to this type of land. Additionally, this resource is desirable for development of the built environment, as it tends to be relatively flat to gently rolling land. This is where the issues arise: unlike food provision, development is not limited to versatile land, but once built upon this land’s potential to support and provide primary production services is lost, essentially, irretrievably. Soil sealing, the covering of the ground by an impermeable material, is said to be one of the main causes of soil degradation in the European Union and, among other things, often affects fertile agricultural land (European Commission Citation2016). As a result of urban sprawl onto food-growing land in Melbourne, local vegetable production is expected to reduce from 82% of Greater Melbourne’s needs to 21% by 2050 (Sheridan et al. Citation2015).

Development pressures confronting versatile land in New Zealand

Development pressures on high class, versatile land are not a new land-use issue and date back to at least the 1960s in New Zealand. As has been the case throughout world history, New Zealand’s settlements developed close to highly productive agricultural land (Hunt Citation1959; Coleman Citation1967), precisely because of the opportunity to feed the population. As a consequence, as urban centres grow, they expand onto these neighbouring fertile, high-value productive lands on which food supply depends. It is estimated the majority of versatile land could be depleted within 50–100 years if these trends continue (Rutledge et al. Citation2010). While there have been a few successes in terms of protecting versatile land from development in New Zealand (e.g. Clothier et al. Citation2012), land-use planning has largely resulted in the disproportionate development of versatile land.

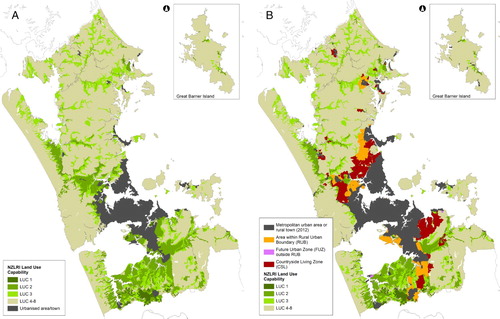

The development of Auckland’s versatile land has been set in train under previous land-use planning regimes and is set to continue in the recently adopted Auckland Unitary Plan. Using the New Zealand Land Resource Inventory (NZLRI) as a baseline, 14% of land use capability (LUC) class 1 land has been or will be encroached upon for various forms of development, as well as 31% of LUC class 2 and 18% LUC class 3 land () (Curran-Cournane et al. Citation2016a). While Auckland represents only 2% of New Zealand’s land area, it has a disproportionate amount of versatile land. The region hosts a highly productive outdoor vegetable sector, contributing over 20% of the nation’s outdoor potato, onion, lettuce, broccoli, cabbage and cauliflower production (Aitken and Hewett Citation2014), a result of highly productive land and frost-free climate. It is unknown how food production will be impacted in the future as a result of the intended development of food-growing land.

Figure 1. Using the NZLRI as a baseline: (A) the distribution of LUC classes 1–3 in Auckland and (B) the Auckland Unitary Plan zoning types.

Development pressures not only exist in terms of urban expansion, but also via the subdivision of rural land for lifestyle properties (Stobbe et al. Citation2009; Andrew and Dymond Citation2013; Inostroza et al. Citation2013). Small parcels of land (8–50 ha and smaller) occupy a significant proportion of the remaining versatile land in Auckland (Curran-Cournane et al. Citation2016c). This occurs around all major populated centres in New Zealand, as Andrew and Dymond (Citation2013) report that one-sixth of lifestyle blocks occupy high-class versatile land (LUC classes 1–2). These pressures are not unique to New Zealand and are shared globally (Stobbe et al. Citation2009; Jiang et al. Citation2013; Skog and Steinnes Citation2016), indicating the simultaneous pressure on land resources and food security occurring worldwide.

Government perspectives on versatile land

In the government’s approach to land management, the priority is placed on ‘releasing’ land for construction rather than for land to be used for current and future food provision and other soil ecosystem services. As evidenced in the Ministry for the Environment’s (MfE) (Citation2016) ‘National Policy Statement for Urban Development Capacity (NPS-UDC)’ and the Productivity Commission’s ‘Using Land for Housing’ (Citation2015) and ‘Better Urban Planning’ (Citation2017) reports, the odds appear stacked against protecting New Zealand’s versatile land from urban development. In the NPS-UDC, a document specifying how to use land, soil is not mentioned at all.

The first reference specifically to ‘high quality soils’ in the ‘Better Urban Planning’ report quotes an abstract from a 1997 speech by the then Minister for the Environment, a non-expert in the subject of soil science, who dismisses the significance of this natural resource with a reference to ‘so called high quality soils’ (p. 107) and deems any potential threat to them as ‘infinitesimal’ (Productivity Commission Citation2017). A close reading of the report suggests that such limited ‘evidence’ and slanted attitudes were used to support the Productivity Commission’s finding F14.1 that ‘a number of historical influences have shaped the planning culture in New Zealand’ including ‘a belief that urban areas need to be contained to protect agricultural soils, and that this was important for NZ’s national identity’ (Productivity Commission Citation2017). Such an approach belies the author’s, and presumably commissioner’s, agenda to create legislation to govern the planning system with ‘a presumption that favours development in urban areas’, a sentiment which comprised the first feature of a proposed future planning framework in the draft for submissions (Productivity Commission Citation2016). This lacked regard for current, internationally peer-reviewed scientific research, findings, and debate in land-use planning and environmental science. It also ascribed agricultural soil preservation to a philosophical standpoint while ignoring its very practical role in feeding a population, not to mention supporting an economy. In the final draft (Productivity Commission Citation2017), the sentiment remains but has been moderated upon advice and further explicated as ‘an appropriate presumption in favour of development for some types of consents, but not others’ (p. 389), to facilitate approvals in the built environment but acknowledging that a presumption may not be appropriate in natural environments where potential pollutant emissions into air, water or land may occur. Such is the narrow scope of environmental effects that neither the land itself nor soil is considered. Substituting a political speech instead of scientific data or analysis reveals the regard for and status of technical expertise in some policy circles. It becomes clear, then, that incorporating scientific information and advice into natural resource management and policy is still challenging for both sides of the science-policy interface.

Challenges associated with protecting versatile land

An age-old argument, that tends to lack substantiated and sound evidence, is that land is worth more under development than under cultivation. Such arguments depend on a narrow neoliberal perspective, tending to recognise the short-term benefits and ignore the longer term costs, assuming the fiction of a free market ‒ a system which can’t predict the needs and aspirations of future generations. Cost–benefit analysis (CBA) assessments have been critiqued for having various limitations when applied in such circumstances as costs and benefits of these land-use activities accrue over very different time horizons (Wegner and Pascual Citation2011; Baveye et al. Citation2016). Discount rates, which express future costs and benefits in terms of present value, act to favour short-term benefits over longer term benefits (Fairgray Citation2017). While this is appropriate in some evaluations, it can be problematic where ecological thresholds exist or the natural resources and ecosystem services are not substitutable, as is the case for versatile land (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017). Wegner and Pascual (Citation2011) suggest the use of CBA should be restricted to the assessment of policies whose impacts do not extend far into the future.

Additionally, market dynamics can be subjectively selected to argue the economic viability of land. There are occasions when a landowner no longer considers his or her block of farmland as economically viable, whether or not it was ever operated as a commercial farm or used for lifestyle block purposes (Curran-Cournane Citation2016). What is ‘economically viable’ can also be very subjective because, land resources being equal, one can argue that a piece of farmland is profitable while a neighbouring property owner can argue otherwise.

In 2015, the dairy prices plummeted to <$4.00 per kilogram of milk solid, with $5.25 needed to break even (DairyNZ Citation2016; Stuff Citation2015). Theoretically, all land under dairying in the country would have therefore been considered to be uneconomically viable, yet the wholesale abandonment of dairy farms did not occur due to a larger suite of economic and other factors. The concept of what is considered to be ‘economically viable’ can therefore be fraught because when based on current land use it is subject to the fluctuating and volatile market as well as the system of policies and regulations that create the market. Additionally, Clothier (Citation2009) argued that the concept of minimum size for an economic farm unit as being quite dated. Using horticulture as an example, Clothier (Citation2009) notes that an owner/proprietor model (i.e. a standalone farm unit with committed machinery and capital assets) is increasingly being replaced by an aggregated agribusiness enterprise model where operations are spread across several blocks of land. Clothier (Citation2009) highlights that the economy of scale of aggregated agribusinesses enables the sharing of equipment, labour, administrative services and capital assets and therefore the actual size of the horticultural block of land in question (4 ha) is not always as relevant as the block’s potential to be fit-for-purpose (i.e. high-class land) within the enterprise’s operation.

It is therefore the inherent qualities of the land which recognise the land’s capability and potential that are important and not solely its current use. The business, and economic viability, of food production may take many forms on a piece of land; the function of food provision itself is the scarce resource. It is, therefore, important that versatile land is preserved to maintain future options – to provide room for food and fibre industries to continue production and manoeuvre to operate in future markets.

The distinction between actual and potential high-value soils for food production was recognised in the previous Town and Country Planning Act (1977). This Act gave way to the Resource Management Act in 1991 which makes no specific mention of ‘versatile’ or ‘high class’ land. Rather Section 5 of the Act uses vague phrasing such as ‘safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air, water, soil and ecosystems’, which has been easily by-passed in court hearings (Mackay et al. Citation2011).

In deciding which land to develop and which to preserve for food production, it is critical to identify explicit trade-offs. Decision makers confront real difficulties evaluating the impacts of development and the evidence to support development can appear incontrovertible given public concern about housing affordability. Evidence on the long-term costs and impacts to a food system for society and future generations is far less well-known. Such matters sit alongside cultural, heritage and environmental interests as well as infrastructural, engineering, transportation and stormwater considerations. However, land-use pressures on versatile land are highly important because not only are these changes effectively irreversible ecologically and environmentally, they also have profound social and economic impacts, especially in farming communities (Curran-Cournane et al. Citation2016b). For example, reverse sensitivity associated with development pressures was identified by a local growers community as one of the key challenges resulting from urban growth and rural fragmentation in Pukekohe (Curran-Cournane et al. Citation2016b).

Opportunities and advancements

Reporting

In 2013, MfE and Statistics New Zealand developed a reporting framework, set out in the Environmental Reporting Act 2015, to ensure the public have reliable, relevant and regular environmental information. New reporting frameworks have since been developed.

Firstly, New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series reports on the state of five environmental domains: air, land, freshwater, marine, and atmosphere and climate. While the specific Land domain report is scheduled for publishing in 2018, the ‘Environment Aotearoa’ (Citation2015) synthesis report offered an overview of the five domains. For the Land section of the report, there was a distinct lack of indicators that reported upon matters and pressures associated with versatile land. Traditionally in New Zealand, soil indicators focus on soil erosion and soil quality. The specific Land domain report therefore presents the opportunity to broaden the perspective by reporting on various indicators and matters associated with rural fragmentation and urban encroachment of versatile land. This enables New Zealanders to have an informed debate about ways to understand and address pressures associated with productive lands.

Secondly, the absence of Land indicators that pertain to versatile land in the national environmental reporting framework to date could be addressed with the development of the Environmental Monitoring and Reporting (EMaR) initiative. EMaR is a partnership between the Local Government New Zealand (LGNZ) Regional Sector and MfE. As with other environmental areas, the EMaR ‘Land’ project aims to achieve nationally consistent and integrated regional-level land and soil monitoring and reporting across New Zealand (Jones et al. Citation2015). The Land Monitoring Forum (LMF), tasked with overseeing the EMaR ‘Land’ project, is a Regional Sector Special Interest Group which was formed by LGNZ in 1999. The forum represents professional and technical experts from all regional councils and unitary authorities throughout New Zealand in roles relating to land and soil science, research, monitoring and input into policy development. Amongst a wide variety of land and soil indicators, the EMaR land initiative will include indicators that monitor and report:

Rural fragmentation

Urban expansion onto versatile land.

These two indicators are at various stages of development and the intention is that the work will eventually be made publically available on Land Air Water Aotearoa (LAWA). It will provide, for the first time, consistently monitored and reported state and trends indicators at the national level.

As well as the development of these metrics, clear definitions and terminology to describe ‘versatile land’ will be established. Currently, a variety of interchangeable terminology is used to describe ‘versatile land’, including reference to ‘high class land/soils’, ‘versatile land/soils’, ‘elite and prime land/soils’. In regards to definitions used to identify versatile land, whether it is the NZLRI (e.g. LUC class 1 and 2) or in conjunction with land evaluation approaches (e.g. Webb et al. Citation1995), the EMaR metrics can progress in the interim to ensure the commencement of reporting. As other resources become available over time, the metrics can be easily revised for state and trends analyses.

The development of land and soil indicators, whether for EMaR, LAWA and/or Environmental Reporting publishing purposes, improves the sharing of resources and public accessibility. While separate reporting platforms, they are not mutually exclusive, and it will therefore be important to ensure the analytical consistency of reported indicators, particularly if the same data sources are used.

Involvement with national submissions

The New Zealand land and soil science community have taken an active interest in participating in recent national submissions, namely the MfE ‘National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity (NPSUDC)’ and the Productivity Commission’s ‘Better Urban Planning (BUP)’ report. While the submissions made by the LMF and the New Zealand Soil Science Society (NZSSS) did not criticise enabling urban growth, each highlighted the fact that not all land is the same and emphasised the importance and value of high-class, versatile land for New Zealand’s prosperity.

In the past, the rural industry sector has been predominantly engaged in the planning system at the regional and national levels. However, there is an important place and need for the scientific community to participate and make evidence-based submissions on matters that relate to land and soil resources and doing so proactively engages and informs policy at the highest level. It will be important to continue to take an active interest in these matters in the future despite whether or not this results in any adjustments of arguments and thinking in final reports, for example, Productivity Commission (Citation2017), where reference to any material submitted by the NZSSS or LMF was overlooked, in contrast to comments and arguments made by other submitters which influenced findings and recommendations. The environmental, economic, and social consequences of losing this natural resource through land development are not appreciated fully in the public discourse, nor has the scientific community fully elucidated the impacts and it will therefore be important to continue to engage and raise the awareness of this moving forward into the future as population and urban growth continue to require trade-offs.

Future research

Currently, New Zealand has no over-arching policy that safeguards food security for the present population or future generations. There also appears to be a clear lack of oversight into how development pressures will affect the food system for society, and there is a considerable absence of funding invested in these research areas.

With an increasing population, New Zealand cannot continue to convert versatile land from agriculture to housing without affecting its food production capability. The question remains as to what the tipping point is before food production is irreversibly affected and fails to meet the needs of the growing population and future generations.

Other questions include the capacity of neighbouring regions to make up shortfalls in food production due to the loss of productive land to housing? Will this have additional implications for environmental pollution and carbon footprints?

There is a misconception that food crops can simply be grown elsewhere, outside land in demand for housing, due to the abundance of land available. However, although land and suitable soil may exist in some parts of other regions, the climate does not permit year-round production of a variety of crops as it does in Auckland. Climate change may significantly affect this so more research is needed to determine how a changing climate will affect all growing regions in New Zealand and expected crop types and yields. This research should include other important factors that influence soil-based food production such as water availability, labour and transport.

These knowledge gaps need to be filled and such research must occur sooner rather than later in order to start understanding the consequences of irreversible land-use decisions that continue to develop versatile land.

National policy statement on protecting versatile land

The current approach to drafting policy statements, strategies and actions plans (e.g. those outlined by the Department of Conservation Citation2010; Ministry for the Environment Citation2014, Citation2016) raises the need for national objectives and policies to ensure the sustainable use of versatile land, a resource of national importance. While representing only a small percentage of New Zealand’s land area, this finite and ever-decreasing resource is in high demand, particularly for land-use activities that are largely irreversible.

The notion for a ‘National Policy Statement on the management of high class soils’ was flagged over 20 years ago in 1996 by the then president of the NZSSS in recognition of the pressures confronting the resource (Basher Citation1996). The need for a national policy on land has since been revisited (e.g. Mackay et al. Citation2011; Andrew and Dymond Citation2013; Singleton Citation2016) and various approaches and strategies have been suggested. For example, Singleton (Citation2016) advocates for a National Policy Statement on Strategic Land Resources that would include ‘National Food Security Zones’ of high-class land protected for exclusively soil-based food production that would give the land the same status and protection as conservation land. Additionally, Horticulture New Zealand (Citation2017) propose a need for a ‘Domestic Food Security Policy’ to ensure the continued sustainable local production of fresh produce for the nation. Whatever the strategic approach it will be important to base an NPS not only on sound technical and scientific advice but one where the potential of land for food production capability is recognised as well as versatile land that is currently being used for soil-based food production. Boundary lines of a safe-guarded area will also need to be carefully placed where soil-based food production will have the least environmental effects in the soil-landscape.

In 2015, work commissioned by the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) entitled ‘Future requirements for soil management in New Zealand’ (Collins et al. Citation2014; Collins et al. Citation2015b; Collins et al. Citation2015a) highlighted the considerable pressure on the availability of land, particularly soils classified as ‘versatile’ in New Zealand. It was suggested that

Greater attention is needed within our policy and planning framework to protect soil functional capacity, reduce the fragmentation of land and loss of versatile soils. This includes the development of regulatory and non-regulatory measures to ensure the full range of services provided by soils is sustained into the future (Mackay et al. Citation2016).

One could argue whether an NPS would even achieve the desired intended outcomes to protect this depleting resource. On the other-hand, it could also be reasonably argued that attempts made to protect versatile land are questionable based on development trends to date. While the soils community have been advocating the value and protection of versatile land for decades it appears voicing the issue to like-minded peers has offered little influence. It would be more effective to debate and progress these land use issues into the realms of policy, law, economics and, of course, politics and decision making.

There are no hard and fast criteria that trigger a National Policy Statement, but good communication and the right timing are conditions that might help to get the prospect placed on the political agenda. Advancing the notion of an NPS will require working with those with technical and scientific expertise as well as collaborating with policy makers and planners. It will be important to continue to work with colleagues at MfE and MPI and to ensure the constant communication of scientific and monitoring advancements (e.g. EMaR indicators) that will help inform sound evidence-based policy on these matters.

One can also learn and build from overseas practices that seek to safeguard agricultural farmland from development. For example, British Columbia (BC), in Canada, is one of the oldest examples where land-use regulation has legislated agricultural land preservation and, as a whole, the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) in BC is considered a success (Nixon and Newman Citation2016).

Conclusion

In a world with increasing uncertainties surrounding the state of natural resources that support regional, national and global food production, such as versatile agricultural farmland, water quality and quantity, and climatic conditions, it would seem prudent to take a precautionary approach towards developing and fragmenting versatile land. A national policy statement would recognise this finite resource and prioritise its protection. As Singleton (Citation2016) notes:

Soil is largely taken for granted and like things taken for granted it is not properly cared for or managed, and then it’s too late. The effects cannot be reversed. For soil the time to act needs to be before you need to, i.e. now.

Among the land and soil science community, there is much motivation and interest in protecting a valuable natural asset. Can we match the progress of the freshwater domain ‒ a resource no longer solely viewed as an environmental concern but also of national socio-economic importance ‒ and raise the general public’s awareness of these land-use matters? It is the role of the land and soil science community to communicate the collective benefit of protecting this resource. In the case of British Columbia, public support for the ‘ALR’ remains strong, primarily for the maintenance of local food production, the economic importance of the agricultural sector, and environmental protection (Androkovich et al. Citation2008). In New Zealand, while it could be argued whether an NPS on protecting versatile land to ensure food security for current and future generations would work, previous attempts made to protect the resource are questionable given development trends to date and therefore an NPS needs to be considered and committed. The challenge is to now progress these land-use matters and protection attempts onto the political agenda which will take time, resources and effort. If not now, the same conversation may be had in another 20 years’ time, when the only difference may be the amount of resource remaining.

Acknowledgements

Craig Fredrickson, Research and Evaluation Unit, Auckland Council, is thanked for the map work. The reviewers of this Short Communication are also acknowledged whose valuable suggestions and feedback have improved the quality of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aitken AG, Hewett EW. 2014. Fresh facts 2014. New Zealand horticulture. ISSN 1177-2190 ISBN 978-0-9876680-6-6. http://www.freshfacts.co.nz/file/fresh-facts-2014.pdf.

- Andrew R, Dymond JR. 2013. Expansion of lifestyle blocks and urban areas onto high-class land: An update for planning and policy. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 43:128–140. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2012.736392

- Androkovich R, Desjardins I, Tarzwell G, Tsigaris P. 2008. Land preservation in British Columbia: an empirical analysis of the factors underlying public support and willingness to pay. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics. 40:999–1013. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800002479

- Basher L. 1996. Re: High class versatile soils and rural subdivision. Copy between the New Zealand Soil Science Society and Minister for the Environment 1996.

- Baveye PC, Baveye J, Gowdy, J. 2016. Soil ‘ecosystem’ services and natural capital: critical appraisal of research on uncertain ground. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 4:609. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2016.00041

- Clothier, B. 2009. Evidence in Chief before the Environment Court in the matter of the Resource Management Act 1991 and the matter of an appeal under Section 120 of the Resource Management Act 1991 between Bunnings Limited (appellant) and Hastings District Council (respondent) APPEAL:ENV-2009-WLG-0182.

- Clothier B, Mackay A, Dominati E. 2012. Natural capital and New Zealand’s Resource Management Act (1991). Joint Soil Science Australian and New Zealand Soil Science Society Soil Science Conference. Soil Solutions For Diverse Landscapes. Wrest Point Hotel and Covention Centre; Dec 2–7; Hobart Tasmania.

- Coleman BP. 1967. The effect of urbanisation on agriculture. In Whitelaw JS, editor. Auckland in ferment. Auckland: New Zealand Geographical Society; p. 102–111.

- Collins A. 2016. The generation game: managing New Zealand’s soil resource to meet current and future needs. New Zealand Society of Soil Science and Soil Science Australia Joint Conference; Dec 12–16; Queenstown.

- Collins A, Mackay A, Basher L, Schipper L, Carrick S, Manderson A, Cavanagh J, Clothier B, Weeks E, Newton P. 2014. Phase 1: looking back. Future requirements for soil management in New Zealand. National Land Resource Centre, Palmerston North.

- Collins A, Mackay A, Hill R, Thomas S, Dyck B, Payn T, Stokes S. 2015a. Phase 3: looking forward. Future requirements for soil management in New Zealand. National Land Resource Centre, Palmerston North.

- Collins A, Mackay A, Thomas S, Garnett L, Weeks E, Johnstone P, Laurensen S, Dyck B, Payn T, Gentile R. 2015b. Phase 2: looking out. Future requirements for soil management in New Zealand. National Land Resource Centre, Palmerston North.

- Curran-Cournane F. 2016. Rebuttal report of Dr Fiona Curran-Cournen on behalf of Auckland Council. Land and soil science. Rural zoning and Ramarama 1 Precinct 1 March 2016.

- Curran-Cournane F, Buckthought L, Golubiewski N. 2016a. The odds are stacked against versatile soil: can we change them? New Zealand Society of Soil Science and Soil Science Australia Joint Conference; Dec 12–16; Queenstown.

- Curran-Cournane F, Cain T, Greenhalgh S, Samarasinghe O. 2016b. Attitudes of a farming community towards urban growth and rural fragmentation – an Auckland case study. Land Use Policy. 58:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.031

- Curran-Cournane F, Lawrence G, Fredrickson C. 2016c. Tracking the progress of the Auckland Plan rural subdivision target (2013 – March 2016). Auckland Council Working Report 2016/003.

- DairyNZ. 2016. DairyNZ: Break-even cost pared back as farmers lift efficiency. [accessed 2016 Aug]. https://www.dairynz.co.nz/news/latest-news/dairynz-break-even-cost-pared-back-as-farmers-lift-efficiency/.

- Department of Conversation. 2010. New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement 2010. Department of Conservation, New Zealand Government. http://www.doc.govt.nz/documents/conservation/marine-and-coastal/coastal-management/nz-coastal-policy-statement-2010.pdf.

- Environment Aotearoa. 2015. Environment Aotearoa 2015 - Data to 2013. New Zealand's Environmental Reporting Series. New Zealand Government. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/Environmental%20reporting/Environment-Aotearoa-2015.pdf.

- European Commission. 2016. European Commission Soil Sealing Guidelines. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/soil/sealing_guidelines.htm.

- Fairgray S. 2017. Land price differentials in Auckland – effect on house prices? A discussion paper. Auckland Council discussion paper. http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/en/planspoliciesprojects/reports/technicalpublications/documents/landpricedifferentialsinaucklandeffectonhouseprices.pdf.

- Greenhalgh S, Samarasinghe O, Curran-Cournane F, Wright W, Brown P. 2017. Using ecosystem services to underpin cost benefit analysis: is it a way to protect finite soil resources?. Ecosystem Services. 27:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.07.005

- Horticulture New Zealand. 2017. New Zealand domestic vegetable production: the growing story 2017 horticulture New Zealand. http://www.hortnz.co.nz/assets/media-release-photos/hortnz-report-final-a4-single-pages.pdfnew.

- Hunt DT. 1959. Market gardening in Metropolitan Auckland. New Zealand Geographer. 15:130–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7939.1959.tb00278.x

- Inostroza L, Baur R, Csaplovics E. 2013. Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: a dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. Journal of Environmental Management. 115:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.11.007

- Jiang L, Deng X, Seto KC. 2013. The impact of urban expansion on agricultural land use intensity in China. Land Use Policy. 35:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.04.011

- Jones H, Drewry J, Burton A, Burgess D, Wyatt, J. 2015. Knowing our land. A review of land and soil state of the environment monitoring and reporting in New Zealand. Scoping report of the Environmental Monitoring and Reporting (EMaR) land project.

- Lowe H. 2016. Editorial – New Zealand Soil News Volume 64 Number 2 May 2016. Newsletter of the New Zealand Society of Soil Science.

- Mackay A, Collins A, Rys G. 2016. Future requirements for soil management in New Zealand. In: Currie LD, Singh R, editors. Integrated nutrient and water management for sustainable farming. http://flrc.massey.ac.nz/publications.html. Occasional Report No. 29. Palmerston North (New Zealand): Fertilizer and Lime Research Centre, Massey University; p. 4.

- Mackay A, Stokes S, Penrose M, Clothier B, Goldson S, Rowarth J. 2011. Land: competition for future use. New Zealand Science Review. 68:67–71.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2014. National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2014. Ministry for the Environment, New Zealand Government. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/fresh%20water/nps-freshwater-ameneded-2017_0.pdf.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2015. Environment Aotearoa 2015 – data to 2013. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series. New Zealand Government. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/environmental%20reporting/environment-aotearoa-2015.pdf.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2016. National Policy Statement for urban development capacity 2016. Ministry for the Environment, New Zealand Government. http://www.mfe.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/towns%20and%20cities/national_policy_statement_on_urban_development_capacity_2016-final.pdf.

- New Zealand Herald. 2016. Food security a late Auckland election issue – New Zealand Herald. [accessed 2016 Oct]. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11722904.

- New Zealand Herald. 2017a. Pukekohe soils sprouting houses – New Zealand Herald. [accessed 2017 Mar]. http://m.nzherald.co.nz/property/news/article.cfm?c_id=8&objectid=11812926.

- New Zealand Herald. 2017b. Urban sprawl and the land that keeps on giving – New Zealand Herald. [accessed 2017 Nov ]. http://www2.nzherald.co.nz/the-country/news/article.cfm?c_id=16&objectid=11944763.

- Newshub. 2017. Government ignores horticulture industry’s calls to protect soils from urban sprawl – Newshub. [accessed 2017 Mar]. http://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2017/03/government-ignores-horticulture-industry-s-calls-to-protect-soils-from-urban-sprawl.html.

- Nixon DV, Newman L. 2016. The efficacy and politics of farmland preservation through land use regulation: changes in southwest British Columbia’s agricultural land reserve. Land Use Policy. 59:227–240. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.07.004

- Productivity Commission. 2015. Using land for housing. New Zealand Productivity Commission. [accessed 2015 Sep]. http://www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/using-land-for-housing-final-report-full%2c%20pdf%2c%204511kb.pdf.

- Productivity Commission. 2016. Better urban planning draft report. New Zealand Productivity Commission. [accessed 2016 Aug]. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/better-urban-planning-draft-report_1.pdf.

- Productivity Commission. 2017. Better urban planning. New Zealand Productivity Commission. [accessed 2017 Feb]. http://www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/master%20compiled%20better%20urban%20planning%20with%20corrections%20may%202017.pdf.

- Rutledge DT, Price R, Ross C, Hewitt A, Webb T, Briggs C. 2010. Thought for food: impacts of urbanisation trends on soil resource availability in New Zealand. Proceedings of the New Zealand Grassland Association. 72:241–246.

- Sheridan J, Larsen K, Carey R. 2015. Melbourne’s foodbowl: now and at seven million. Victorian Eco-Innovation Lab, The University of Melbourne. http://www.ecoinnovationlab.com/wp-content/attachments/melbournes-foodbowl-now-and-at-seven-million.pdf.

- Singleton P. 2016. Letter to the editor – New Zealand Soil News volume 64 Number 3 August 2016. Newsletter of the New Zealand Society of Soil Science.

- Skog KL, Steinnes M. 2016. How do centrality, population growth and urban sprawl impact farmland conversion In Norway? Land Use Policy. 59:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.035

- Stobbe T, Cotteleer G, Eagle A, Vankooten G. 2009. Hobby farms and protection of farmland in British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Regional Science. 32:393–410.

- Stuff. 2015. Fonterra revises down milk price to $3.85. [accessed 2015 Aug]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/dairy/70912048/Fonterra-revises-down-milk-price-to-3-85.

- Tóth G. 2012. Impact of land-take on the land resource base for crop production in the European Union. Science of the Total Environment. 435–436:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.103

- Webb T, Jessen M, Mcleod M, Wilde R. 1995. Identification of high class land. Broadsheet, New Zealand Association of Resource Management, November 1995, 109–114.

- Wegner G, Pascual U. 2011. Cost-benefit analysis in the context of ecosystem services for human well-being: a multidisciplinary critique. Global Environmental Change. 21:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.12.008