ABSTRACT

Whakataukī are part of a strongly developed Māori oral tradition that conveys critical information about aspects of life, society and tribal memory, including ecological knowledge. Such codified knowledge depends on language use and structure as a key mechanism for cultural transmission. Additionally, many meanings may not be apparent without knowing the historical, cultural and linguistic context from which the whakataukī originated. We examined a primary dataset of c. 3500 versions of whakataukī, drawn from collections published after European arrival c. 200 years ago, to determine how marine and freshwater principles, practices and knowledge bases have developed in response to changing environmental and societal contexts in Aotearoa. We present information on marine and freshwater resources contained in whakataukī to shed light on the connections between humans and their environment that transcend prosaic uses and enlighten deeper social and behavioural engagement with the surrounding environment. Understanding past engagement can help shape future marine and freshwater relationships in Aotearoa.

TUHINGA-WHAKARĀPOPOTO

Ko te whakataukī he wāhi nui o te pakari o ngā kōrero tuku iho a te Māori, kei a ia te hōhonu o te whakaatu i te kaikini o te mātauranga e pā ana ki te hauoranga, te hapori, me te mau ā-mahara a ngā iwi, tae atu ana ki te mātauranga o te taiao. He pānga nui ki reira nō te reo me ōna hanga rerenga, he huarahi whakahirahira mō te tuku ahurea. Tua atu o tērā kāhore rā pea he māramatanga ki te kore e mōhiotia te horopaki ā-whakapapa, ā-ahurea, ā-ringikuihi i puta mai ai te whakataukī. Ko tā mātou he tirotiro ki tētahi huinga raraunga hirahira o ētahi whakataukī, tata pea ki te 3500, i tīpakohia mai i ētahi kohinga i tuhia nō muri noa i te taenga mai o te Pākehā. 200 tau pea ki muri. Mai i reira kitea ai te whaonga o te mātāpono, te tikanga, me te mātauranga ā-waitai, ā-waimāori hoki; hei takatūranga ki te takahurihanga o ngā horopaki ā-taiao, ā-pāpori hoki i Aotearoa nei. Anei tā mātou whakaatu i ētahi mōhiohio mō ētahi rawa ā-waitai, ā-waimāori hoki mai i te whakataukī hei whakamārama i ngā hononga i waenganui i te tangata me tōna taiao tua atu o te whakamahinga noa, inā rā he whakamārama kē ake i te hōhonu o ngā pānga ā-ahurea, ā-whanonga ki te paenga o te taiao. Mā te mōhio ki ngā mahi o ngā rā o mua tētahi āwhina nui ki te tārai i ngā hūāngatanga ā-waitai, ā-waimāori hoki o āpōpō ki Aotearoa nei.

Introduction

Māori have a close association, affiliation and connection with the sea, bodies of water and its many manifestations (Best Citation1929; Tipa Citation2009). This close association stems from Māori ancestral seafaring origins in East Polynesia, from where Polynesian ancestors populated the outer regions of the Pacific, finally settling in Aotearoa (Sneider and Kyselka Citation1986; Lewis Citation1994; Evans Citation1997; Prickett Citation2001). These early Polynesian settlers brought with them an extensive Pacific knowledge base; reminders of their tropical Pacific origins are scattered throughout the landscape of Aotearoa and embedded in many places and species names that pay homage to Polynesia (New Zealand Geographic Board Citation1990; Biggs Citation1991; Turoa Citation2000; Riley Citation2001).

Fishing and harvesting of marine and freshwater resources were a core activity of early Māori who were initially concentrated in coastal regions (Best Citation1929; Barber Citation2004; Leach Citation2006; Paulin Citation2007). These settlers used their knowledge of tropical Pacific environments together with developing marine, ecological, horticultural and agricultural knowledge bases (applicable to both the warm subtropical climate in the north and the cooler temperate climate in the south of Aotearoa) to observe, test, develop and re-establish environmental, meteorological, astronomical and marine relationships (King et al. Citation2007; Harris et al. Citation2013; Tāwhai Citation2013). These traditions and observations were embedded in various oral formats including whakataukī/whakatauākī (proverbs), maramataka (lunar calendars), karakia (incantations), pepeha (tribal saying, tribal motto, formulaic expression), whakapapa (genealogy), kupu whakarite (metaphors), kōrero (prose), pūrākau (narratives that contains philosophical thought and worldviews) and waiata (song and chant) (Mead and Grove Citation2001; Tāwhai Citation2013; McRae Citation2017). These oral traditions carry the ecological knowledge that can elucidate Māori relationships with nature. Here, we focus on whakataukī, passed from generation to generation as

a concise phrase, a single statement, a short passage, a brief conversation. Apart from proverbs, epithets, mottos and slogans that arise from pithy comment or observation, there are instructions, intentions, greetings and farewells, predictions and challenges. There are also exchanges between individuals, abbreviated forms of tribal boundaries, as well as quotations from, or summary beginnings and endings to, songs and narratives. Form has to do with function here as well. (McRae Citation2017)

Whakataukī have been examined in a variety of contexts to gain insight on traditional knowledge and practices and contemporary applications, including traditional ecological knowledge (Wehi Citation2009; Wehi et al. Citation2018; Whaanga and Wehi Citation2016), and many other areas of research (see McRae Citation1987; Seed-Pihama Citation2004; Metge and Jones Citation2005; Seed-Pihama Citation2005; Wehi Citation2006; Kawharu Citation2008; Wehi et al. Citation2009; Edwards Citation2010; Pihama et al. Citation2015; Greensill et al. Citation2017; McRae Citation2017). Wehi et al. (Citation2013) examined whakataukī that refer to marine environments and found that these sayings aligned well with broader archaeological data on food sources, but also illuminated connections between humans and their environment that transcend harvesting to reach into patterns of human behaviour and societal development. Here, we develop this approach further. We first focus on expressed relationships between species and ideas in both marine and freshwater whakataukī. Second, we unpack some of the deeper meanings within a subset of whakataukī to demonstrate the transposition/transformation of knowledge to human realms, acting to embed humankind into a worldview where human whakapapa is inside not outside nature.

In this paper, we discuss examples of the various functions of whakataukī and examine the range of relationships demonstrated in whakataukī for marine and freshwater species.

Methods

Dataset

Māori oral tradition was recorded by many early European ethnographers, missionaries, colonial administrators, ethnographers, linguists, explorers and politicians (see Wehi et al. (Citation2018) for details and a discussion of these sources). In short, we used a pariemological dataset of 2669 Māori ancestral sayings (Mead and Grove Citation2001) as our primary dataset, supplemented by additional entries from Grove (Citation1981) (n = 3421).

Data analyses

Qualitative analyses of whakataukī included inspection of word frequencies, determined using an online word counting tool (http://www.textfixer.com/tools/online-word-counter.php). All function words (such as he ‘a’, te/ngā ‘the’ and roto ‘in’) were removed from the dataset using standard UNIX operations (particularly the command line program grep). However, care was taken with words that are both function words (e.g. roto ‘in’) and content words (e.g. roto ‘lake’) in Māori. Temporal assignments of whakataukī were made using linguistic, historical and cultural cues as described in both Wehi et al. (Citation2013) and Wehi et al. (Citation2018). All statistical approaches were implemented in R v. 3.4.3 (R Development Core Team Citation2018).

Results and discussion

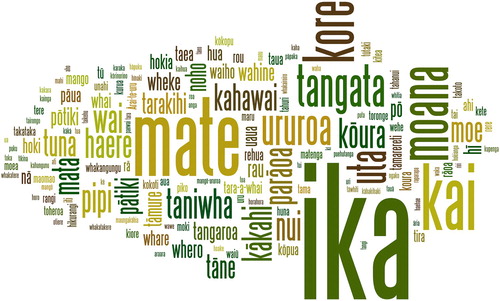

Of the 3421 whakataukī in this dataset, 233 refer to marine and freshwater-based faunal resources. This represents approximately 35% of the faunal whakataukī in the dataset (Wehi et al. Citation2013). The three highest frequency words are the noun ika (fish; n = 44), the stative/noun mate (be dead, deceased, killed, sick, ill, ailing, diseased, beaten, defeated, conquered, misfortune; n = 25) and kai (food; n = 22) (). Many of the references to marine and freshwater fauna occur in generic form; of the 125 references to fish, most are generalised (e.g. ika). Nevertheless, 34 fish species (e.g. tāmure ‘snapper’ Pagrus auratus; hāpuku ‘groper’ Polyprion oxygeneios) are identifiable in the dataset (). Of the marine and freshwater fauna that can be identified in whakataukī, the proportion of marine vs. freshwater is 82% (n = 150) marine and 18% freshwater (n = 32).

Figure 1. Relative frequency of content words in the marine and freshwater subset of Māori whakataukī. Simple function words have been excluded for clarity.

Table 1. Names of freshwater and marine species mentioned in whakataukī database.

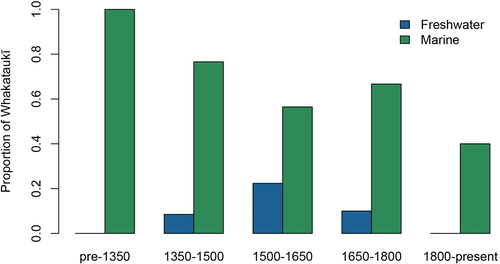

A comparison of marine and freshwater whakataukī showed that references to marine species declined with time while there was a slight increase in references to freshwater species in the period AD 1500–1650 (). This increase was mostly due to references to kākahi (freshwater mussel; Echyridella menziesii), and tuna (eel; Anguilla spp.).

Figure 2. Proportions of whakataukī that mention marine (green) and freshwater (blue) resources scaled by the numbers of whakataukī attributed to different historical time periods.

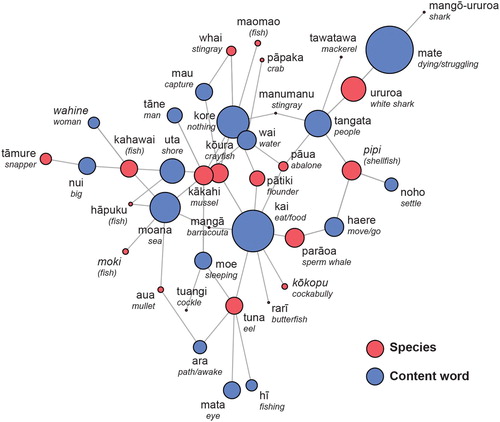

To investigate the relationships of species to the high-frequency words appearing in individual whakataukī, we created a network of species names to high-frequency content words (e.g. where kai and koura, or kai and pātiki, occur in the same whakataukī). This reveals an association between sharks, death (mate) and humans (tangata) (), indicating a strong relationship between shark behaviour (i.e. struggling to death, persistence, perseverance) and desired human attributes in times of war and confrontation. Another relationship from tuna (eel) to kai (food) and fishing, watchfulness vs. sleeping, and pathways (ara) details the importance of alertness and observation. The proximity of fish species and the network to moana (ocean) and uta (towards the shore) gives a good example of spatial proximity to these species, and the noun nui (large) indicates the importance of size with kahawai and tāmure. The network of wai (water) to the shallower species (e.g. pāua, pātiki, pāpaka, whai etc.) and then to kai (food) but also to mau (capture) illustrates a further example of food sources and spatial proximity to harvesting actions. The network to kore (oblivion, annihilation, destruction, nothingness) highlights kore as an intriguing node that encapsulates the destruction and potential of all things, where species are connected to a state of ‘nothingness’ (one meaning of kore) but also the process for the ‘potential for everything’ (a further interpretation of kore).

Figure 3. Network of whakataukī that mention marine and freshwater resources (red) and their association with high-frequency content words (blue). Circle size indicates how common each word is in the whakataukī data set.

The network analysis highlights that specific species are used to portray different values, historical events, chieftainship, or harvesting practices in whakataukī, and a body of ecological and cultural information/understandings is embedded in these networks. For example, the freshwater species kākahi was a highly valued and culturally iconic resource in the central North Island lakes area, as are kōura (crayfish; Paranephrops planifrons), where tuna (eel) were rare or absent. The kākahi whakataukī have a number of functions. For example, they reference cultural traditions that include child rearing practices, Ka whakangotea ki te wai o te kākahi ‘It was suckled on the juice of the freshwater shellfish’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001); industriousness and hard work, Tāne rou kākahi, aitia te ure; tāne moe whare, kurua te takataka ‘If a man dredges mussels, love him well; if he sleeps at home, bang his head’, where women were advised to avoid lazy men; chieftainship, Te kākahi whakairoiro o te moana ‘The ornamented mollusc of the sea’, which alludes to the carved moko and ornaments worn by chiefs (Mead and Grove Citation2001); and rebukes, in this case to an inferior of lesser rank, Māu e kī mai te kākahi whakairoiro o te moana ‘Is it for you to speak as the ornamental mussel of the lake?’, where kākahi whakairoiro is a term that refers to a chief of high rank and a mottled orca (a dominant killer of the sea) (Mead and Grove Citation2001).

Tuna, generically ‘eels’, are a very highly prized freshwater resource and their significance and function is portrayed in the variety and type of whakataukī mentioned in the database. The references to tuna have a number of functions including warfare; He ua ki te pō, he tuna ki te ao ‘Rain at night, eels in the morning’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001). In these examples, ecological knowledge (e.g. of the movement of eels across the land during rain as they move to spawn) may be paired with important cultural messages. Thus, He ua ki te pō, he paewai ki te ao (Grove Citation1981) is an edict of tribal warfare describing a night attack in bad weather has the advantages of low visibility and masking of the sounds, and Moe ana te mata hī tuna, ara ana te mata hī taua ‘The eyes of the eel-fisher are closed in sleep but the eyes of those who fish for war parties remain open’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), is applied to watchfulness in war. Other examples of tuna describe preparation techniques; Me te raparapa tuna ‘Like eels split open for drying’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), Me te whata raparapa tuna e iri ana te tutu ‘The tutu berries are hanging like split eels’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), which outline its preparation technique where tuna is split and hung on a stick in the sun to dry, and culinary practices; Huruhuru kai wawe, tuna whakaoho ‘Feathers eaten hastily, eels alarmed’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), which notes the leaving of feathers on the birds prepared for eating and inadvertently consumed would cause birds and eels to leave their normal habitats, to proper preparation techniques, and other examples instruct us to be prepared; Nāu i whakatakoto i tō hīnaki i te wai tāwawarua anei te waituhi ka taha ‘You set your eel-pot during the main flood, after the first freshet had passed and therefore missed the descending eels’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), outlines that effective actions must be carried out at the right time. In the following example, the morphological qualities of the tuna's slippery skin and its status as a prized food is used to contrast it to a loss where something worthwhile has slipped away; Kua kaheko te tuna i roto i aku ringaringa ‘The eel has slipped through my hands’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001).

Whakataukī may act to recall or recount historical events; He tāmure unahi nui ‘The snapper of big scales’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), which refers to Tūtāmure, a great warrior leader of Te Wakanui, who was named for the tāmure that pricked Kahungunu's finger, and another event when Kahungunu called out to ask who was attacking his pā, and Tūtāmure replied with the following; Ka rangaranga te muri, ka tū ngā tuātara o tāmure ‘When the breeze blows gently will the spines of the snapper stand up’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001). Another whakataukī that is applied to someone who has been raised a noble birth and skilled to carry out difficult tasks mentions the nene, the part at the base of the tongue of the tāmure, which was the most prized part of the fish and only fed to elite and noted warriors; E kī ana ahau, i whāngaia koe ki te nene o te tāmure o Whangāpanui, kia tiu koe, kia oha ‘I think you were fed on the nene of the snapper of Whangāpanui so that you might be active and strong’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001). This example describes the capture of the chief Tamaruarangi and his son Te Rangitūmai and the words that Tamaruarangi spoke to encourage his son to escape and raise an avenging party.

The 38 references to ika are generic in nature containing a range of historical and didactic information on leadership, chieftainship, warfare and societal guidelines. Warfare is a frequent subject of whakataukī, where ika is used as an idiom for an enemy or to refer to a slain warrior, victim, or the first or second person slain in battle, Kei au te mātāika! ‘I have the honour of the first slain’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), a veteran warrior Te ika a Whiro ‘Whiro's fish’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), and to those lost in war where the god of war (Tū) is contrasted to the god of peace (Rongo) and their relationship, Te ika a Tū, te ika a Rongo ‘The fish of Tū, the fish of Rongo’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001). In the example, E kore e mau i a koe te whai i te ika iti, i rāoa ai Tamarereti, ka horo Maungaroa ‘You cannot win the chase of the little fish, by which Tamarereti was choked and Maungaroa fell’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), a war stratagem is presented by contrasting a well-known whakataukī on preparation and small details, He meroiti te ika i rāoa ai a Tamarereti ‘It was a small fish that choked Tamarereti’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), and He paku te ika i rāoa a Tamarereti ‘It was a small fish on which Tamarereti choked’ (Mead and Grove Citation2001), to a historical battle at Whetūmatarau. Tamarereti was a great navigator who sailed into the Antarctic waters only to choke to death while eating a small fish. Here the lesson relates to a little stratagem applied correctly can have outstanding results.

Conclusion

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of whakataukī together with word frequencies, temporal assignments, linguistic, historical and cultural cues, and network analyses combine to illustrate the wealth of traditional ecological knowledge contained in just one form of Māori oral tradition (Wehi et al. Citation2018). The sample of selected examples highlight the complexity of this intrinsic relationship and the various linguistic strategies and layers that were used to embed knowledge of place, space, history, religion, belief and tradition. These cultural lessons, historical recounts and practical observations provide invaluable insight on the type and nature of the interactions that Māori had – and continue to have – with marine and freshwater resources and the changing environmental, societal and cultural landscapes that they occur in. Oral tradition and knowledge of the Māori language can inform and stimulate new perspectives on marine and freshwater policy and practice in Aotearoa in invaluable ways, but it is an area that is often overlooked, undervalued and underestimated and one that requires innate knowledge of oral traditions and practical expertise of traditional ecological knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Hēmi Whaanga http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5415-9960

Priscilla Wehi http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9821-8160

Murray Cox http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1936-0236

Tom Roa http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3774-7891

Ian Kusabs http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1473-7447

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barber I. 2004. Sea, land and fish: spatial relationships and the archaeology of South Island Maori fishing. World Archaeology. 35(3):434–448. doi: 10.1080/0043824042000185829

- Best E. 1929. Fishing methods and devices of the Maori. Vol. 12. Wellington: Dominion Museum. (Dominion Museum Bulletin).

- Biggs B. 1991. A linguist revisits the New Zealand bush. In: Pawley A, editor. Man and a half: essays in pacific anthropology and ethnobiology in honour of Ralph Bulmer. Auckland: Polynesian Society; p. 67–72.

- Edwards WJW. 2010. Taupaenui: Māori positive ageing [doctor of philosophy]. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Evans J. 1997. Nga waka o nehera: the first voyaging canoes. Auckland: Reed.

- Greensill H, Manuirirangi H, Pihama L, Mahealani Miller J, Lee-Morgan J, Campbell D, Te Nana R. 2017. He maimoa i ngā whakatupuranga anamata: Ko te mātauranga taketake o ngā tūpuna me te whakarea tamariki. Te Kōtihitihi: Ngā tuhinga reo Māori. 4:86–96.

- Grove N. 1981. Ngā pēpeha a ngā tīpuna. Wellington: Department of Maori Studies, Victoria University of Wellington.

- Harris P, Matamua R, Smith T, Kerr H, Waaka T. 2013. A review of Māori astronomy in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 16(3):325–336.

- Kawharu M. 2008. Tāhuhu kōrero: the sayings of Taitokerau. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- King DN, Goff J, Skipper A. 2007. Māori environmental knowledge and natural hazards in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 37(2):59–73. doi: 10.1080/03014220709510536

- Leach BF. 2006. Fishing in pre-European New Zealand [Special publication Archaeofauna volume 15]. Wellington: New Zealand Journal of Archaeology.

- Lewis D. 1994. We, the navigators: the ancient art of landfinding in the pacific. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- McRae J. 1987. He pepeha, he whakatauki no Taitokerau. Whangarei: Dept. of Maori Affairs.

- McRae J. 2017. Māori oral tradition. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Mead SM, Grove N. 2001. Ngā pēpeha a ngā tīpuna: the sayings of the ancestors. Wellington: Victoria University Press.

- Metge J, Jones S. 2005. He taonga tuku iho nō ngā tūpuna: Māori proverbial sayings – a literary treasure. Journal of New Zealand Studies. 5(2):3–7.

- New Zealand Geographic Board. 1990. He kōrero pūrākau mo ngā taunahanahatanga a ngā tūpuna: place names of the ancestors, a Māori oral history atlas. Wellington: Author.

- Paulin CD. 2007. Perspectives of Māori fishing history and techniques. Ngā āhua me ngā pūrākau me ngā hangarau ika o te Māori. Tuhinga. 18:11–47.

- Pihama L, Greensill H, Campbell D, Te Nana R, Lee-Morgan J. 2015. He kura pounamu. Hamilton: Te Kotahi Research Institute.

- Prickett N. 2001. Māori origins: from Asia to Aotearoa. Auckland: Auckland Museum.

- R Development Core Team. 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Riley M. 2001. Māori bird lore: An introduction. Paraparaumu: Viking Sevenseas NZ Ltd.

- Seed-Pihama J. 2004. Te waka pakau ki te moana: A translation and examination of various Taranaki ancestral sayings [MA thesis]. Hamilton: University of Waikato.

- Seed-Pihama J. 2005. Māori ancestral sayings: A juridical role. Te Mātāhauariki Institute Occasional Paper Series No.10. Hamilton: Te Mātāhauariki Institute.

- Sneider C, Kyselka W. 1986. The wayfinding art: ocean voyaging in Polynesia. Berkeley (CA): Regents of the University of California.

- Tāwhai W. 2013. Living by the moon: Te maramataka a Te Whānau-ā-Apanui. Wellington: Huia.

- Tipa G. 2009. Exploring indigenous understandings of river dynamics and river flows: a case from New Zealand. Environmental Communication. 3(1):95–120. doi: 10.1080/17524030802707818

- Turoa T. 2000. Te takoto o te whenua o Hauraki: Hauraki landmarks. Auckland: Reed.

- Wehi PM. 2006. Harakeke (Phormium tenax) ecology and historical management by Māori: the changing landscape in New Zealand [Ph.D.]. Hamilton: University of Waikato.

- Wehi PM. 2009. Indigenous ancestral sayings contribute to modern conservation partnerships: examples using Phormium Tenax. Ecological Applications. 19(1):267–275. doi: 10.1890/07-1693.1

- Wehi PM, Cox M, Roa T, Whaanga H. 2013. Marine resources in oral tradition: He kai moana, he kai mā te hinengaro. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures. 2:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.imic.2013.11.006

- Wehi PM, Cox M, Roa T, Whaanga H. 2018. Human perceptions of megafaunal extinction events revealed by linguistic analysis of indigenous oral traditions. Human Ecology. doi:10.1007/s10745-018-0004-0.

- Wehi PM, Whaanga H, Roa T. 2009. Missing in translation: Maori language and oral tradition in scientific analyses of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 39(4):201–204. doi: 10.1080/03014220909510580

- Whaanga H, Wehi PM. 2016. Māori oral tradition, ancestral sayings and indigenous knowledge: learning from the past looking to the future. Langscape. 5(2):56–59.