ABSTRACT

The Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System is founded on partnerships between people, disciplines and knowledge systems. This freshwater management framework is being developed at the scale of the Te Ara Koroka Pounamu Trail. Numerous barriers prevented Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku use of the trail from around the 1880s; however, this cultural landscape and the values, beliefs and practices it supports (past, present and future) are still central to the identity of Murihiku whānau. To help reconstruct and revitalise mātauranga Māori around Te Ara Koroka, historical literature sources were used, alongside cultural value mapping, interviews and contemporary information sources. This paper explores cultural heritage methods to show how indigenous knowledge can be meaningfully and respectfully protected in research programmes. We propose that access requirements and protection mechanisms used by museums, libraries and archives could inform improved processes to better protect mātauranga Māori within the New Zealand science and innovation system.

Glossary of Māori words: Hapū: sub-tribe, extended whānau; Hīkoi: journey; Iwi: tribe; Kaitiaki: guardian; Kaitiakitanga: the exercise of customary custodianship, in a manner that incorporates spiritual matters, by tangata whenua who hold manawhenua status for a particular area or resource; Karakia: incantation, ritual chant, prayer; Kaupapa: aim, purpose, issue, topic; Kaumātua: elder; Ki uta ki tai: ‘from the mountains to the sea’, Ngāi Tahu holistic resource management framework; Manawhenua: traditional/customary authority over a particular area and usage of resources of that area; Mātauranga: knowledge; Maramataka: Māori lunar calendar; Murihiku: tribal region in the southern South Island; Ngāi Tahu: tribal grouping of Ngāi Tahu; Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku: Ngāi Tahu from Murihiku (south of the South Island); Nohoanga: temporary campsite for seasonal gathering of resources; Pounamu: greenstone, New Zealand jade; Rūnanga/Rūnaka: local Māori representative groups/councils, for Ngāi Tahu in contemporary times these are those referred to in the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Act 1996 and in Murihiku include Hokonui Rūnaka, Te Rūnanga o Ōraka-Aparima, Waihōpai Rūnaka, and Te Rūnanga o Awarua; Tangata whenua: people of the land, people who hold manawhenua in an area according to tribal and hapū custom; Taonga tuku iho: treasure/s to be protected for the next generations; Tikanga: rights, customs, accepted protocol, Māori lore or law; Tino rangatiratanga: self-determination; Tuna: eels; Tūpuna: ancestors, grandparents; Waiata: song, chant, psalm. Wānanga: tribal knowledge, learning, to meet discuss and deliberate; Whakapapa: genealogy, ancestry; Whānau: family/ies; Wai: Water; Whakataukī: proverb

Introduction

Water and freshwater ecosystems play a central role in Māori identity, values and uses and are considered a taonga tuku iho (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Citation2013; IAG Citation2015). Māori manage and understand the environment through their unique worldview and knowledge system (mātauranga Māori). Mātauranga originates, and is specific to, geographic place and local context. Roberts (Citation2012) illustrates this ‘place’ as being ‘one’s land, sea, sky and cosmos’. In this paper, we use the following definition for mātauranga Māori: Mātauranga Māori is holistic perspective encompassing all aspects of knowledge and seeks to understand the relationships between all component parts and their interconnections to gain an understanding of the whole system. It is based on its own principles, frameworks, classification systems, explanations and terminology. Mātauranga Māori is a dynamic and evolving knowledge system, has both qualitative and quantitative aspects, and includes the processes for acquiring, managing, applying and transferring that body of knowledge (Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga project team Citation2016).

The inclusion of tangata whenua values in freshwater management and decision-making is required by numerous pieces of legislation and policy including Resource Management Act 1991, Conservation Act 1987, Fisheries Act 1996, and Local Government Act 2002. Treaty of Waitangi Settlements seek to further increase Māori involvement in freshwater co-management and governance (e.g. Waikato River, Te Waihora, Te Arawa Lakes, Whanganui River). However, in New Zealand, current approaches are struggling to respectfully recognise and provide for tangata whenua uses and associations in a climate of multiple and often conflicting demands (e.g. Tipa Citation2012; Tipa et al. Citation2016).

Māori require access to high-quality information that incorporates and moves beyond discipline-specific approaches to meet their unique aspirations and needs (Williams et al. Citation2015). To meet this need requires the involvement of the relevant Māori community/ies to co-develop the decision-making frameworks, produce the required data, as well as providing the assessment and analysis of the information within the appropriate cultural context to ensure it meets their co-management and co-governance needs (Gyopari Citation2015; Tipa et al. Citation2016; Tipa et al. Citation2017).

The Government’s Vision Mātauranga policy framework aims to ‘unlock the innovation potential of Māori knowledge, resources and people to assist New Zealanders to create a better future’ (MORST Citation2005). While the intent of this policy is to be ‘the next step in the ongoing Treaty relationship’ and ‘remain future focused (embedded in opportunities)’ (MORST Citation2009) it has the potential to remove the control and tino rangatiratanga over Māori knowledge and innovation from iwi, hapū and whānau (Mercier Citation2007; Broughton and McBreen Citation2015). The intent of this policy can also be undermined by researchers who dismiss indigenous knowledge as irrelevant or needing to be validated by science methods (Rist and Dahdouh-Guebas Citation2006; Jacobson and Stephens Citation2009).

As mātauranga Māori becomes imbedded in freshwater management, so do the paradigms of those whānau providing the knowledge, meaning greater emphasis and meticulousness is required to articulate and apply that information within the relevant cultural context. As has been witnessed in Waitangi Tribunal hearings, ‘ancestral Māori and modernist propositions are often strategically interwoven, forming a simple complex kaupapa, or argument. The Māori participants typically include not just elders and tribal experts, but also historians, lawyers, scientist, priests, administrators and Tribunal members’ (Salmond Citation2017).

With the increasing influence of mātauranga Māori in improving outcomes for freshwater management, there is a need to develop enduring mechanisms that enable different knowledge systems and disciplines to work in co-production (Berkes Citation2009; Mclean and Cullen Citation2009; Richmond et al. Citation2013), or ‘interface research’ (Durie Citation2004a, Citation2004b; Ahuriri-Driscoll et al. Citation2007; Mercier Citation2007) ensuring the integrity of the respective systems is upheld. New Zealand and international law are currently deficient in being able to protect cultural intellectual property of indigenous knowledge systems (e.g. Waitangi Tribunal Citation2010; Lei Citation2014; Telhure Citation2015). Therefore, incorporation of indigenous knowledge currently relies on the voluntary establishment of robust research and collaborative partnerships that actively facilitate the development of relationships between knowledge holders that are underpinned by appropriate protocols, models and guidelines (e.g. Durie Citation2004a; Hepi et al. Citation2007; Smith Citation2012; Gyopari Citation2015).

Historical information sources are important to inform the contemporary freshwater management context (Tipa Citation2013). Cultural Heritage combines the fields of culture, heritage and development, to support the expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation, including customs, practices, places, objects, artistic expressions and values (ICOMOS Citation2002). However, cultural heritage expertise is seldom used alongside standard scientific approaches in freshwater research. In partnership with Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku, we are incorporating cultural heritage information as one of the knowledge systems used to inform the development of the Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System. This paper explores the use of cultural heritage methodologies in a Crown-funded research programme. We review practices within heritage to identify mechanisms that can assist in building understanding amongst science researchers and their institutions to ensure kaitiakitanga and tino rangatiratanga of mātauranga contributed by Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku are respected and protected. This paper discusses the protection of indigenous intellectual property/ mātauranga Māori–not from a legal perspective, but one drawn from practicality and experience.

Case study approach

Ngā Kete o te Wānanga: Mātauranga Māori, Science and Freshwater management is a research programme that was directed, by the Crown, to explore ‘the optimisation of synergies between mātauranga Māori, science and other knowledge systems will improve decision-making and collaborative freshwater management in New Zealand’. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment also directed that the programme be undertaken in two regions (Murihiku and Canterbury). As the regional case studies have progressed, our rūnanga partnerships have further defined the culturally relevant freshwater management context, scales, and knowledge gaps that are important to them. Mutual needs and benefits are potent drivers for collaboration and knowledge co-production. The identification of questions of common interest is an important pre-condition for the establishment of a dialogue between different knowledge-holders (Gyopari Citation2015). In a climate of multiple demands on the capacity and capability of Māori individuals, whānau, rūnanga and iwi this approach is necessary to create the buy-in and trust that is critical for the long-term benefits of the programme and the likelihood of success in terms of outcomes that are generated for the benefit of New Zealand.

Classification systems of New Zealand’s land, freshwater and marine environments describe selected features within those environments and are used to underpin conservation and resource management (e.g. Threatened Environment Classification, Marine Environment Classification). However, no environmental classification system in New Zealand stems from cultural values or mātauranga Māori, while internationally, indigenous/traditional classification systems have added depth to classifications based on physical and scientific knowledge for natural resources, like soils and snow (Barrera-Bassols et al. Citation2006; Eira et al. Citation2013).

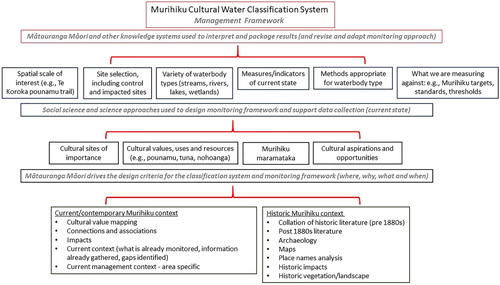

Within Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga, the Murihiku case study proposes to build upon the intent of the Third Schedule of the Resource Management Act i.e. how can we articulate Class C waters (those waters being managed for cultural purposes, where ‘the quality of the water shall not be altered in those characteristics which have a direct bearing upon the specified cultural or spiritual values’). We are developing a Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System (MCWCS) () to strengthen cross-cultural understandings about Murihiku cultural values, and their water-related dependencies–as defined by the Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group–in a robust, respectful and meaningful way. In this framework, we bring knowledge together from various disciplines (including mātauranga Māori, social science, science and cultural heritage) around different cultural value/use thematics that are of importance to Murihiku whānau such as, Wai Tuna, Wai Pounamu, Wai Nohoanga.

Figure 1. Overarching methodology guiding the development of the Murihiku Cultural Water Use Classification System (Source: Kitson et al. Citation2014, Citation2018)

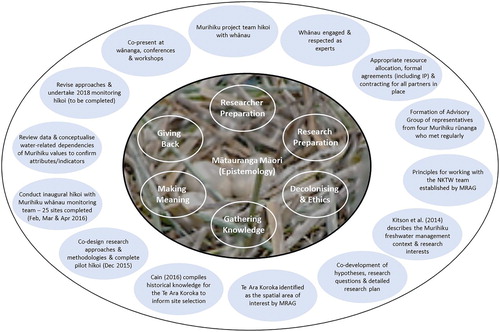

At the onset of the Ngā Kete o te Wānanga programme, an indigenous research approach (Kovach Citation2009) was adapted to guide the research process and principles, in partnership with Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku (Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga project team Citation2016, ).

Figure 2. (Centre circle) A conceptual indigenous research framework adapted from Kovach (Citation2009); and (Outer circle) Some of the actions completed to date in the Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga research programme to adapt and implement this indigenous research framework in the Murihiku takiwā. IP = Intellectual Property, NKTW = Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga, and MRAG = Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group (Source: Williams et al. Citation2018)

The Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group, comprising of nominated members of the four rūnanga in Murihiku, directed the research team to work at the scale of the Te Ara Koroka Pounamu Trail which extends approximately 270 km across the Aparima River, along the Waiau and Mararoa (Maraeroa) rivers, and past Lake Wakatipu (Whakatipu Waimāori) before returning down the Waiau River. This culturally relevant spatial area crosses catchments and jurisdictional boundaries, respecting the context within which the mātauranga of Murihiku whānau who once used the trail was generated, and implementing the Ngāi Tahu resource management principle of ki uta ki tai.

For Māori, ‘the past, the present and the future are viewed as intertwined’ (Rameka Citation2016) and the past is a pillar of their identity, and informs their contemporary and future management contexts (Tipa Citation2013). To inform the development of the MCWCS we drew together historical information sources up to the 1880s. By the 1880s, Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku had stopped using the Te Ara Koroka Pounamu Trail due to access issues and extensive environmental changes that occurred during European settlement. Therefore, a major component of the MCWCS is about reconstructing and revitalising mātauranga Māori around Te Ara Koroka.

Appropriate permissions for using historical information sources

The main tenet of interface research is trust (Hepi et al. Citation2007). For trust to exist, Māori must retain tino rangatiratanga over cultural heritage information. According to tikanga Māori, certain things may be publicly known but not open to the indiscriminate use by all, including members of its own community (Cram Citation2006; Lei Citation2014), and even if it is shared it is still not considered to be in the public domain (Lei Citation2014). Sharing of knowledge by kaitiaki does not transfer the kaitiaki responsibility. This sharing also may not convey an on-going use right, which is bound by the tikanga of the Māori community (Lei Citation2014).

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (Citation2003) describes this as ‘Private domains’ rather than ‘Public domains’. They argue that the ‘public domain’ is purely a construct of the intellectual property system and that it does not take into account private domains established by indigenous and customary legal systems (Dutfield Citation2000; WIPO Citation2003). Part of the protection of such knowledge is not to share it outside the cultural context in which the information was generated and is required to inform. Not sharing also avoids information being misappropriated and misused in outsider contexts.

The MCWCS requires cultural and scientific knowledge systems to be both respected and validated within their own respective systems. As such the research team discussed the management of the permissions and appropriateness of disseminating different historical information source types. For the MCWCS, cultural-historical information is managed two ways: (1) the indigenous research framework and principles that guide the overall research; and (2) caveats for use of heritage data (). These approaches were approved by MRAG in the initial phases of the programme and are constantly referred to.

Table 1. Cultural heritage and historic information sources approved by the Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group for use during the initial phases of the development of the Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System as part of the Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga research programme.

The historical permissions table (see for extracts) contains the key information sources that are used in MCWCS site selection, field work, analysis, reporting and monitoring. The historical information includes written, oral and visual sources. The table provides the day-to-day structure for the management of mātauranga and is based on the tikanga of Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku. The permissions table states what permissions for use are required for each information source and how that information is to be used and disseminated within the programme. For example, publicly released reports and documents are, in the first instance, to use what information is already in the public domain.

Time is also taken to understand what information is actually required for the paper or report, and who the intended audience is. In regard to the development of the MCWCS, most of the information regarding the specific route to Te Koroka remains with the kaitiaki whānau and has not been published. Not all the specific sites or significant places and uses associated with the route to Te Koroka, nor karakia, waiata or whakapapa have been included in the synthesis report. The exclusion of certain knowledge is a deliberate decision by the research team to ensure kaitiaki whānau retain control over how the information is interpreted and reused when shared in the public domain.

The exclusion of selected knowledge held by whānau in papers published under the Ngā Kete o te Wananga programme does not mean that it has not been used to help select what examples to include in the reports and direct the analysis. The information required to inform any analysis is discussed and reviewed with multiple kaitiaki whānau and the Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group. In this programme, the authenticity of knowledge does not come from whose work is cited but that the Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group has approved it.

Historical sources and biases

Myers (Citation1997) states

All research (whether quantitative or qualitative) is based on some underlying assumptions about what constitutes ‘valid’ research and which research methods are appropriate. In order to conduct and/or evaluate qualitative research, it is therefore important to know what these (sometimes hidden) assumptions are.

While the development of the MCWCS looks to use information already in the public domain, whānau expect that the MCWCS will not repeat factually incorrect information or take it out of context. What whānau envisage is that historical information sources are critically analysed within the freshwater management context defined by Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku. In practice, this approach requires a lot of trust between whānau and the researcher, and the assessment of each piece of historical information can be time-consuming.

Accounts and newspaper articles from the 1800s about the environment reflect European attitudes at the time and their biases (Young Citation2004). The identification of potential land for pastoralisation was a preoccupation of the Settler Government. Surveyor’s reports generally include statements about the potential of land for primary production; for example, J Thomson wrote to Captain Cargill in 1857 of his survey of the Waiau area (Southland) ‘Upon the whole the abundance of good pasture and sufficiency of timber appear to be the most useful facts that I have to bring to your notice.’ (Otago Witness, 18 April 1857).

This attitude to land production and creating ‘a Britain of the South’ (Galbreath Citation1993) coincides with a decline in the Māori population. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’, many believed Māori were a dying race. In a rush,

Ethnologists aided by Māori language informants collected a huge volume of information. From these oral and written sources, Pakeha ethnologist rewrote and reconstructed the traditional histories with scant consideration for tribal variations, and presented tribal accounts as common to all Māori. (Haami Citation2012)

The impact of ethnographers is highlighted in the work undertaken by the Society of Māori Astronomy Research and Traditions (SMART):

Discussion between researchers and communities also often include criticism of early ethnographic works, with many Māori doubting the validity of some of the information that was given to the ethnographers by some informants. There also is concern that the sources of the information often were not disclosed by the ethnographers. (Harris et al. Citation2013)

These differences in opinion always need to be considered when using historical information sources. For MCWCS to navigate around the potential issues of bias and the context in which the material was originally written, the historical sources went through an analytical process by working with kaitiaki whānau/rūnanga and triangulation with other disciplines and sources, such as archaeology. By doing so, the assumptions behind the information and the bias of the author and society at the time becomes clearer, and then the dismantled historical information can be culturally reviewed and endorsed. The benefits and issues associated with using three historical written sources to inform our understanding of how Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku valued and used the environment in the past is summarised in .

Table 2. The issues and benefits associated with using historical written sources to inform the development of the Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System as part of the Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga research programme.

How heritage mechanisms can inform research institutions to support kaitiakitanga and tino rangatiratanga of mātauranga by Māori

Carbonell (Citation2004) explains that ‘History involves selection, juxtaposition, and narrative fashioning.’ How this is done and the role of indigenous people in that process has been discussed at length by collection and lending institutions for decades (Schlereth Citation1978; McCarthy Citation2011; Diamond Citation2012; Tapsell Citation2014). The experiences of New Zealand, such as the ground-breaking Te Maori exhibition in 1984/5, are often used internationally as examples of how change can happen within established cultural institutions and professional standards.

Hooper-Greenhill (Citation2000) noted that in a museum context

‘Māori have successfully demanded that their cultural treasures be re-valued. This has meant that Māori objects have been taken out of the natural history and ethnographic collections in which they were formally classified, and are now placed within new contexts where they are able to assert their own aesthetic and cultural identity … Histories are being rewritten from new perspectives and the past is being re-memorised to privilege different events. Formerly silent voices are being heard, and new cultural identities are being forged from the remains from the past.

As recognition of the importance of indigenous knowledge grows, greater efforts are made to protect it, especially in the digital age (Brown and Nicholas Citation2012; Hill et al. Citation2012; Christen Citation2015). Collection and lending institutions in New Zealand have stringent controls on who can access information and for what purpose.Footnote1 For example, the Māori Reference Collection held by the National Library requires the researcher to request access to certain information prior to being able to view it onsite, in the reading room.Footnote2 Another example is the Hocken Library that requires whānau permission for researchers to access information about tūpuna/original material from tūpuna and a clear outline from the researcher of the intended use. Sometimes whānau do decline access which is supported and upheld by the institution (A. Cain, pers. comm.).

A loan agreement is required for when borrowing items from the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. To borrow Māori taonga, the applicant is required to include a letter of support from the appropriate iwi.Footnote3 For Archives New Zealand, restrictions on use are set by the depositing agency. The primarily reason is to protect privacy, but can also relate to material deemed to be of a sensitive nature. Access to restricted records can be provided only with the written permission from the agency responsible for the restriction.Footnote4

Over the years, the value of mātauranga Māori held by collection and lending institutions has evolved and increased. These examples demonstrate how institutions have taken on the role of protecting mātauranga by involving whānau and other agencies in decision-making for access. Consideration is also given to the impact the research will have on that knowledge or the context in which it is interpreted. Staff are employed to oversee the protection of mātauranga and assess requests with on-going self-assessment and criticism on how these institutions could do better. There is the ever-present risk for Māori that aspects of their culture are used in inappropriate or unwelcome ways (Brown and Nicholas Citation2012). As expectations change on what and how information is available, so do access requirements and protection mechanisms.

Discussion

A major component of the MCWCS is about reconstructing and revitalising mātauranga Māori around Te Ara Koroka. Barriers prevented the further use of the trail from around the 1880s; however, this landscape and the cultural values, beliefs and practices it supports (past, present and future) are still central to the identity of Murihiku whānau. We used historical literature sources, alongside cultural value mapping, interviews and contemporary information sources () to recreate the ‘what, where, when and how’ to inform the MCWCS. This research also helps upcoming generations learn about the trail/area/values/uses and build capacity and capability for upcoming freshwater management processes.

This approach provided a Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku historical context that included kaika, nohoanga, methods of travel, and mahinga kai for the purpose of informing contemporary freshwater management. It is through the partnership of these knowledge systems, underpinned by approaches that ensure the integrity of each knowledge system employed, that we can be assured of the robustness and effectiveness of the research outputs and outcomes produced for the benefit of Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku.

In employing different knowledge systems in the research programme, we needed to understand and map out the expectations each discipline brings with it. In our case, this includes the expectations of science, as well as heritage and mātauranga Māori. Each bring their different needs for knowledge protection and dissemination and each ‘are built on distinctive philosophies, methodologies and criteria’ (Durie Citation2004a). The whakapapa of knowledge is important and by employing heritage mechanisms within the MCWCS we have endeavoured to ensure mātauranga Māori not only directs the research, but it remains protected and owned by its respective contributor(s).

There are international expectations for the protection of indigenous knowledge, including the Mataatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples 1993 which include statements to ‘Recognise that indigenous peoples are the guardians of their customary knowledge and have the right to protect and control dissemination of that knowledge.’ ‘Recognise that indigenous peoples also have the right to create new knowledge based on cultural traditions.’ and ‘Accept that the cultural and intellectual property rights of indigenous peoples are vested with those who created them.’

In 2010, New Zealand signed the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration asserts the rights of Indigenous peoples to ‘maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures … ’ and to ‘maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.’Footnote5 In conjunction with indigenous peoples, the government is to take effective measures to recognise and protect these rights.

The on-going evolution of freshwater governance mechanisms in New Zealand also effects the influence of mātauranga Māori. Hill et al. (Citation2012) reviewed four different Australian approaches to environmental projects: indigenous-governed collaborations; indigenous-driven co-governance; agency-driven co-governance; and agency governance. The manifestations of indigenous knowledge and science integration were then analysed according to governance types. They found that there was a corresponding link between the way the integrity of indigenous knowledge was managed and how well it was used in the management approaches. Indigenous governance and Indigenous-driven co-governance provided the most suitable governance types to enable the incorporation of indigenous knowledge with other knowledge systems. This change in power sharing is a foundational challenge for New Zealand in moving forward, where the majority of governance types are most likely to be agency governance or in some cases agency-driven co-governance.

Although appropriate incorporation of mātauranga Māori may require a system change at the national level for the New Zealand science and innovation system, there are measures that can promote indigenous-governed collaborations, and indigenous-driven co-governance within individual research institutes and programmes. Lessons can be learnt from our nation’s museums and libraries where mechanisms and resources are applied to ensure the protection and appropriate use of cultural knowledge. Protection of mātauranga Māori and the continual assessment and evolution of these processes, has become part of their standard operating procedures. This expectation should become ‘business as usual’ within the New Zealand freshwater and marine sciences community.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support, we have had from Ngā Rūnanga ki Murihiku, Murihiku whanau monitoring team and the wider Ngā Kete o te Wānanga research team. In particular, we wish to mihi to Drs Gail Tipa and Erica Williams for the assistance and mentorship in the Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See Digital NZ Copyright, Accessibility, Privacy https://digitalnz.org/copyright-accessibility-privacy

References

- Ahuriri-Driscoll A, Hudson M, Foote J, Hepi M, Rogers-Koroheke M, Taimona H, Tipa G, North N, Lea R, Tipene-Matua B, Symes J. 2007. Scientific collaborative research with Māori communities kaupapa or kūpapa Māori? AlterNative. 3:60–81. doi: 10.1177/117718010700300205

- Barrera-Bassols N, Zinck JA, Van Ranst E. 2006. Local soil classification and comparison of indigenous and technical soil maps in a Mesoamerican community using spatial analysis. Geoderma. 135:140–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.11.010

- Berkes F. 2009. Indigenous ways of knowing and the study of environmental change. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 39:151–156. doi: 10.1080/03014220909510568

- Broughton D, McBreen K. 2015. Mātauranga Māori, tino rangatiratanga and the future of New Zealand science. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 45:83–88. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2015.1011171

- Brown D, Nicholas G. 2012. Protecting indigenous cultural property in the age of digital democracy: institutional and communal responses to Canadian first nations and Māori heritage concerns. Journal of Material Culture. 17:307–324. doi: 10.1177/1359183512454065

- Carbonell BM. 2004. Locating history in a Museum: editor’s introduction. In: Carbonell BM, editor. Museum studies: an anthology of contexts. Oxford: Blackwell; p. 311–314.

- Christen K. 2015. Tribal archives, traditional knowledge, and local contexts: why the ‘s’ matter. Journal of Western Archives. 6(1):1–19. Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/westernarchives/vol6/iss1/3

- Cram F. 2006. Talking ourselves up. AlterNative. 2:28–43. doi: 10.1177/117718010600200102

- Diamond J. 2012. Custom and Toi Māori. In: Keegan D, editor. Huia histories of Māori Ngā Tāhuhu Kōrero. Wellington: Huia Publishers; p. 326–337.

- Durie M. 2004a. Exploring the Interface Between Science and Indigenous Knowledge. 5th APEC Research and Development Leaders Forum: Capturing Value from Science. Christchurch. New Zealand. 22 p. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.507.6505&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Durie M. 2004b. Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Epidemiology. 33:1138–1143. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh250

- Dutfield G. 2000. The public and private domains: intellectual property rights in traditional knowledge. Science Communication. 1:276–277.

- Eira IMG, Jaedicke C, Magga OH, Maynard NG, Vikhamar-Schuler D, Mathiesen SD. 2013. Traditional Sami snow terminology and physical snow classification-Two ways of knowing. Cold Regions Science and Technology. 85:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.coldregions.2012.09.004

- Galbreath R. 1993. Working for wildlife: a history of the New Zealand wildlife service. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books in association with the Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs. 200 p.

- Gyopari M. 2015. A review of the application of frameworks, models and methods for partnering Mātauranga Māori and biophysical science in a fresh water management and transdisciplinary research context. Client Report Wellington (New Zealand): Earth In Mind Limited. 36 p.

- Haami B. 2012. Tā Te Ao Māori writing the Māori world. In: Keegan D, editor. Huia histories of Māori Ngā Tāhuhu Kōrero. Wellington: Huia Publishers; p. 164–195.

- Harris P, Matamua R, Smith T, Kerr H, Waaka T. 2013. A review of Māori astronomy in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 16:325–336.

- Hepi M, Foote J, Marino M, Rogers M, Taimona H. 2007. “Koe wai hoki koe?!”, or “Who are you?!”: issues of trust in cross-cultural collaborative research. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 2:37–53.

- Hill R, Grant C, George M, Robinson CJ, Jackson S, Abel N. 2012. A typology of indigenous engagement in Australian environmental management: implications for knowledge integration and social-ecological system sustainability. Ecology and Society 17:23. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04587-170123.

- Hooper-Greenhill E. 2000. Changing values in the art Museum: rethinking communication and learning. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 6:9–31. doi: 10.1080/135272500363715

- Iwi Advisory Group. 2015. Iwi/Hapū Rights and Interests in Freshwater: Recognition Work-Stream: Research Report. Iwi Chairs Forum, New Zealand. 81 p. http://iwichairs.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IAG-Freshwater-Recognition-Research-Report.pdf

- ICOMOS, International Cultural Tourism Charter. 2002. Principles and Guidelines for Managing Tourism at Places of Cultural and Heritage Significance. ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Committee. International Council on Monuments and Sites. 48 p.

- Jacobson C, Stephens A. 2009. Cross-cultural approaches to environmental research and management: a response to the dualisms inherent in Western science? Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 39:159–162. doi: 10.1080/03014220909510570

- Kitson J, Cain A, Williams E, Blair S, Johnstone MNTH, Davis J, Grey M, Kaio A, Anglem R, Young R, Whaanga D. 2018. Developing a Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System. Report prepared for the Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group, Te Ao Mārama Inc and Ōraka-Aparima Rūnaka. NIWA, Wellington, NZ.

- Kitson J, Te Ao Marama Inc, Murihiku Rūnanga Advisory Group. 2014. Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku Freshwater Management Context. Client Report Prepared by Kitson Consulting Ltd. November 2014. 65 p.

- Kovach M. 2009. Indigenous methodologies: characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 216 p.

- Lei J. 2014. Indigenous cultural heritage and intellectual property rights: learning from the New Zealand experience? Cham: Springer. 327 p.

- McCarthy C. 2011. Museums and Māori heritage professionals indigenous collections current practice. Wellington: Te Papa Press.

- Mclean K, Cullen L. 2009. Research methodologies for the co-production of knowledge for environmental management in Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 39:205–208. doi: 10.1080/03014220909510581

- Mercier OR. 2007. Indigenous knowledge and science. a new representation of the interface between indigenous and eurocentric ways of knowing. He Pukenga Kōrero. 8:20–28.

- Ministry of Science Research Science and Technology (MORST). 2005. Vision Mātauranga: unlocking the innovation potential of Māori knowledge, resources and people. Wellington: MORST. 28p. http://www.mbie.govt.nz/info-services/science-innovation/pdf-library/vm-booklet.pdf

- Ministry of Science Research Science and Technology (MORST). 2009. Evaluation of Vision Mātauranga and the Māori Knowledge and Development output class. File reference: SE233701. October 2009. 59 p.

- Myers MD. 1997. Qualitative research in information systems. Management Information Systems Quarterly. 21:241–242. doi: 10.2307/249422

- Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga project team. 2016. Ngā Kete o Te Wānanga: Mātauranga Māori, Science & Freshwater Management Research Plan. Version 3: Years 4 to 6. November 2016. 81 p.

- Rameka L. 2016. Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on the past’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 17:387–398. doi: 10.1177/1463949116677923

- Richmond L, Rose B, Middleton B, Gilmer R, Grossman Z, Janis T, Lucero S, Morgan T, Watson A. 2013. Indigenous studies speaks to environmental management. Environmental Management. 52:1041–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00267-013-0173-y

- Rist S, Dahdouh-Guebas F. 2006. Ethnosciences–A step towards the integration of scientific and indigenous forms of knowledge in the management of natural resources for the future. Environment. Development and Sustainability. 8:467–493. doi: 10.1007/s10668-006-9050-7

- Roberts M. 2012. Revisiting ‘The natural world of the Māori’. In: Keegan D, editor. Huia histories of Māori Ngā Tāhuhu Kōrero. Wellington: Huia Publishers; p. 33–56.

- Salmond A. 2017. Tears of Rangi: experiments across worlds. Auckland: Auckland University Press. University of Auckland. 512 p.

- Schlereth T. 1978. Collecting ideas and artifacts: common problems of history Museums and history texts. Roundtable Reports. Summer-Fall:: 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40288031.

- Smith LT. 2012. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples, 2nd ed. London and New York: Zed Books. 240 p.

- Tapsell P. 2014. Māori and museums–ngā whare taonga’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/maori-and-museums-nga-whare-taonga.

- Telhure D. 2015. Traditional knowledge: As intellectual property, it’s protection and role in sustainable future. RESEARCH HUB–International Multidisciplinary Research Journal. 2:1–7. Retrieved from www.rhimrj.com.

- Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. 2013. Ngāi Tahu 2025. Christchurch: Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. http://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/NgaiTahu_20251.pdf

- Tipa G. 2012. Environmental flow assessments: a participatory process enabling Māori cultural values to inform flow regime setting. In: Johnston B, Hiwasaki L, Klaver I, Water A, editors. Cultural diversity & global environmental change: emerging trends, sustainable futures? UNESCO International Hydrological Programme; Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN); UNU-IAS Traditional Knowledge Initiative. Center for Political Ecology Dordrecht: Springer; p. 467–491.

- Tipa G, Harmsworth G, Williams E, Kitson J. 2016. Integrating mātauranga Māori into freshwater management, planning and decision making. In: Jellyman PG, Davie TJA, Pearson CP, Harding JS, editors. Advances in New Zealand freshwater sciences. Christchurch, NZ: New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society and New Zealand Hydrological Society.

- Tipa GT. 2013. Bringing the past into our future-using historic data to inform contemporary freshwater management. Kotuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 8:40–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2013.837080.

- Tipa GT, Williams EK, Van Schravendijk-Goodman C, Nelson K, Dalton WRK, Home M, Williamson B, Quinn J. 2017. Using environmental report cards to monitor implementation of iwi plans and strategies, including restoration plans. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 51:21–43. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2016.1268176

- Waitangi Tribunal. 2010. Ko Aotearoa tēnei: a report into claims concerning New Zealand law and policy affecting Māori culture and identity. Te taumata tuatahi. (Waitangi Tribunal report). Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand. 298 p. www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz.

- Williams E, Tipa G, Van Schravendijk-Goodman C, May K, Kitson J, Harmsworth G, Smith H, Kusabs I, Severne C, Ratana K. 2015. Data Management and Knowledge Visualisation Tools for Hapū and Iwi to Support Freshwater Management: a scoping study. Report prepared for the Department of Conservation. January 2015. NIWA Client Report No: WLG2015-17. NIWA, Wellington, NZ. 58 p.

- Williams EK, Watene-Rawiri EM, Tipa GT. 2018. Empowering indigenous community engagement and approaches in lake restoration: an Āotearoa-New Zealand perspective. In: Hamilton D., Collier K., Howard-Williams C., Quinn J., editors. Lake restoration handbook: A New Zealand perspective. Cham: Springer. [accessed 2018 Oct 16 ] https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319930428#aboutBook.

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). 2003. Culture as a commodity? Intellectual property and expressions of traditional cultures WIPO magazine 4:9–15.

- Young DD. 2004. Our islands, our selves: a history of conservation in New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University Press. 298 p.