ABSTRACT

Estuaries support a wide range of human activities and values, but are one of the most anthropogenically impacted ecosystems in the world. Ki uta ki tai is a holistic view of waterways that is embodied within Ngāi Tahu environmental management, which acknowledges the connectivity between environmental systems and people with the environment. While this philosophy is referred to within current policies, management does not effectively account for or reflect this philosophy. This research evaluated indigenous and local socio-cultural values provided by estuarine shellfisheries across Waitaha/Canterbury and found Ngāi Tahu place-based interaction was impacted by management and anthropogenic inputs. Participants’ estuarine stressors aligned with global stressors. Experienced harvesters/fishers adapted their practices to these stressors, while less experienced harvesters/fishers visited high food-risk sites. Effective management requires identifying the risks to socio-cultural values towards accountability of activities, to meet the ethic of ki uta ki tai.

Glossary of Māori words: kaitiaki: an official custodian/guardian as designated by tangata whenua, but the general and traditional role of environment resource managing is practiced by all tangata whenua members; kaitiakitanga: the exercise of customary custodianship/environmental resource management by those who hold mana whenua/moana status for a particular area or resource; kanohi-ki-te-kanohi: face-to-face; kaupapa Māori principles: Māori-specific paradigm and research methodologies; ki uta ki tai: literally ‘inland-coastward’/‘from inland-to-sea’/‘from mountain-to-sea’; koha: gift, gift giving (an act of reciprocity); mahinga kai: ‘places at which food (and other commodities) were extracted or produced’; Māori: literally normal, the indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ); mana whenua: hapū/iwi who hold tribal authority over land or territory in a particular area; mātaitai reserve: customary fishery management area; mātauranga Māori (also shortened to mātauranga): the intellect, knowledge and creativity created by Māori to explain their experience of the world; hapū: ‘sub-tribe’/extended kinship group; iwi: tribe/nation; Ngāi Tahu: the principal tribe with authority of most of Te Wai Pounamu; rāhui: a closure/restriction on harvesting and/or activities within a site, due to, but not limited to, health and environmental disturbances, any incidents from being in the sea, or marine habitat restoration purposes; tangata whenua: the indigenous people of Aotearoa NZ; Te Wai Pounamu: literally ‘The Greenstone Waters’, the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand; tikanga: Māori cultural customs; tūrangawaewae: place where one has rights of residence and belonging through kinship and whakapapa; Waitaha (originally Ngā Pākihi Whakatakataka o Waitaha): Canterbury; whakapapa: genealogy, lineage; whanaungatanga: relationship building, kinship.

Introduction

Estuaries receive terrestrial, freshwater and marine input, which create highly productive environments that are favoured highly by people. These ecosystems provide for recreation, cultural wellbeing, aesthetic, societal traditions and commercial activities (Harmsworth Citation1997; Ghermandi et al. Citation2009; Barbier et al. Citation2011; Clough Citation2013; Thrush et al. Citation2013). However, due to their proximity to major settlements, estuaries are among the most anthropogenically-impacted aquatic ecosystems on earth (Kennish Citation2016).

Ngāi Tahu (a principal indigenous tribe of Te Wai Pounamu/South Island of Aotearoa NZ/New Zealand) are concerned about the on-going degradation of estuarine and coastal shellfisheries/fisheries (Waitangi Tribunal Citation1987; Tau et al. Citation1992; Waitangi Tribunal Citation1992; Hepburn et al. Citation2011; Dick et al. Citation2012; McCarthy et al. Citation2014). Estuaries were part of an extensive mahinga kai network, ‘places at which food and other commodities were extracted or produced’ (Tau et al. Citation1992; Memon et al. Citation2003), which contributed to local tribal economies for hundreds of years (Williams Citation2016).

Although indigenous philosophies are frequently referred to by local authorities, they are not necessarily embedded within an indigenous context. For instance, ki uta ki tai is a Ngāi Tahu environmental ethic that acknowledges the connectivity ‘from mountain to the sea’ as well as the reciprocal relationship between people and the environment (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Citation2003; Tipa et al. Citation2016). The bio-physical component of this philosophy is well-recognised in scientific research and the local council has set an objective to achieve an integrated ‘ki uta ki tai and beyond approach’ to implementing water management from mountain-to-sea by 2020 (Canterbury Water Citation2012; Environment Canterbury Citation2015). Current policies and management do not effectively account for this (Hart & Bryan Citation2008; Phillips et al. Citation2010; Schiel & Howard-Williams Citation2016), nor does it account for local and indigenous values.

Increasingly, indigenous and local values are utilised towards management. For example, indigenous narratives contain detailed explanations of environmental events and ethics (Handy et al. Citation1972; Patterson Citation1994; Lee Citation2009; Berkes Citation2012), which incorporates conservation, cooperation, gathering and preservation technologies towards management (Best Citation1929; Costa-Pierce Citation1987; Smith & Pai Citation1992; Beattie Citation1994; Dacker Citation1994; Anderson Citation1998; Poepoe et al. Citation2003). Interviews with indigenous people are an important and effective way of gathering specialist knowledge of the traditional resource sites (Tipa & Teirney Citation2003) and local peoples perspectives of marine fisheries and management (McCarthy et al. Citation2014; Hughey et al. Citation2016). Cultural health indices have successfully been utilised for waterway and marine environmental decision-making (Tipa & Teirney Citation2003; Walker Citation2009; Schweikert et al. Citation2013).

Given that the rapid loss of culturally-valued ecosystems and landscapes can contribute to social disruptions and societal marginalisation (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005), it is important to understand the values of local and indigenous people. Identifying and understanding the risks of environmental degradation on socio-cultural values is going to be integral to the effective future management and accountability of anthropogenic activities in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) estuaries. This research begins to address this by evaluating the socio-cultural values provided by estuarine shellfishery areas across Waitaha.

Methods

Survey groups, questions and areas

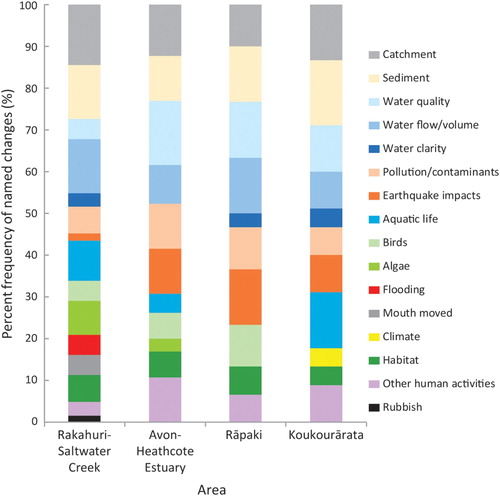

Recreational Participants (RP) and Local Practitioners and Specialists (LPS) were surveyed across four geographically distinct areas (, ): the Rakahuri/Ashley River-Saltwater Creek Estuary (R-SC), the Avon-Heathcote Estuary/Ihutai (AH), Rāpaki Bay (RA), and Koukourārata (KR). Both RA and KR are within mātaitai reserves with rāhui (closure/restriction on harvesting/activities within a site), while AH has permanent warning signs of potential food risks.

Figure 1. Location of study catchments in Waitaha Canterbury. GIS layers downloaded in 2016 (LRIS Citation2012; Canterbury Maps Citation2015; LINZ Citation2015).

Table 1. Number of Local Practitioners and Specialists (LPS), Recreational Participants (RP) and participant experience (years) surveyed across four Waitaha estuaries.

The objective was to interview a representative core of 20 LPS and at least 80 RP across the four estuaries who had varying place-based experiences and cultural affiliations. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Ethics Committee and the Māori Research Advisory Group of the University of Canterbury (HEC 2013/158). Prior to conducting this research, kanohi-ki-te-kanohi engagement was undertaken with hapū/iwi (sub-tribe/tribe).

The RP consisted of on-site ‘beach-going/fisher’ participants who were intercepted ‘on-site’ and were kept anonymous, while LPS were surveyed at an arranged time and place to provide space for discussion. LPS included those who had considerable long-term experience at each area (e.g. Ngāi Tahu, local residents, local environmental committee members, scientists/ecologists and gatherers/fishers). Additional participants were identified using ‘snowball’ sampling (Goodman Citation1961); that is, when interviewees provide future interviewees from among their acquaintances.

The LPS and RP were surveyed with the same questions in a semi-structured format, and two additional questions were asked to LPS to learn about the traditional and current cultural values supported by each estuary (see Supplementary Material). The questions were intended to:

identify who visits the area;

elicit the participants’ main activities and times for visiting;

elicit what fishery/other resource participants may favour or target, and whether there were perceived changes to the relative abundance(s) over time;

elicit the perceived environmental condition of the site and catchment, and whether any changes have occurred over time;

Identify any environmental indicators utilised by participants in association with site, activity and/or value; and

identify current individual practices/behaviours and whether local management was regarded as effective.

The majority of the RP were surveyed over summer 2014/2015 due to very few participants being present in the colder months. Those who were not able to complete the survey on-site were provided with one to take away with them, which were returned by mail (N = 3) or interviewed over the phone (N = 2). The LPS were fully briefed as to the purpose of the survey, consent was sought, and these surveys were voice-recorded, transcribed and then checked by participants prior to analysis.

Analysis

The interviews were analysed using a mixed-methods approach with an explanatory design (Goodrick & Emmerson Citation2009), which focusses on using the quantitative data (e.g. perceived environmental condition score), with use of qualitative descriptions/themes (e.g. environmental/fishery indicators used by participants). Anonymous survey data (n = 106) were entered into NVivo11 for the qualitative analysis and into Microsoft Excel prior to Statistica Version 13 for the quantitative analysis. This data was organised according to participant attributes (location/estuary, group, cultural affiliation and experience).

The Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse nominal answers relating to main activities and environmental scores, which were compared across participant attributes. A Spearman correlation analysis was used to analyse the relationship between participant experiences (<5/10/20/30 years) with perceived environmental condition and change scores. When analysing for correlations between multiple variables the probability of detecting a Type I error false discovery rate increases (McDonald Citation2009); therefore, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to control for this (Benjamini & Hochberg Citation1995). The assumption of normality for each statistical test was checked prior to undertaking the quantitative analyses.

Results

Participant attributes

A total of 83 RP and 23 LPS were surveyed across the four Waitaha estuaries ( and ). In response to the question of ‘cultural affiliation’ it is noted that New Zealand European citizens/residents (NZE) were more uncomfortable in answering this question compared to other ethnicities. Participants were predominantly male (61%) and NZE affiliated (65%) compared to Ngāi Tahu (19%), NZ Māori (i.e. non-Ngāi Tahu; 9%), Cook Island Māori (2%) and visitors/tourists (5%). LPS were generally older (mode: 61–70 y) and more experienced (20–30 y) than RP (mode: 21–50 y and <5–30 y, respectively).

Traditional and current values

Waitaha estuaries are highly valued by LPS affiliated to NZE and Ngāi Tahu. The NZE-affiliated LPS associated cultural and traditional values with their heritage and Ngāi Tahu/mana whenua (people who hold tribal authority over land/territory). The NZE-affiliated LPS and RP enjoyed these places with their families, for leisure and wellbeing. The Ngāi Tahu affiliated LPS associated cultural and traditional values with tūrangawaewae (place where one has rights of residence) and whakapapa (genealogy). Their values are also interconnected with social, ecological, and economical values, for instance, ‘The [tribal] reserves were food gathering areas and at that time our tribe was fisheries dependent; the [tribal] economy was based on subsistence’ (LPS).

The ability for LPS to actively practice Ngāi Tahu values included the above attributes (e.g. whakapapa) and environmental integrity. Over time, these values have been impacted by land-use, contemporary natural resource management and political activities (e.g. drained wetlands, wastewater/industrial inputs, and excluded iwi authority). For instance,

‘Te Ihutai was taken under Public Works Act [1928] in 1956 and left us with one functioning estuary, the Ashley River Estuary [associated with R-SC]. The Crown breached Article Two of the Treaty of Waitangi and the RMA was not yet legislated.’ ‘ … it was confiscated … they took it and didn’t talk to the tribe, they spoke to the trust board.’ (LPS).

In this example, a tribal reserve called Te Ihutai in the Avon-Heathcote Estuary (AH) was acquired without engagement with mana whenua, whose rights and interests were further impacted by the Christchurch Drainage Board wastewater treatment plant. Within the AH there is currently, ‘ … a boundary created by poor environmental health’ (LPS). In addition, the compensation reserve (also named Te Ihutai) near R-SC was impeded upon by the widening of State Highway 74.

Activities

Peoples’ estuarine activities (and the proportion of participants who favoured them) included fishing/harvesting shellfish (29%–100%), leisure (50%–67%), gathering inanimate resources (0%–43%), and ‘other’ activities including kaitiaki tasks, catchment replanting and bird watching (0%–50%). Fishing and harvesting were done for leisure, catch-and-release, consumption, bait, and included monitoring/research of fish/shellfish species by kaitiaki and Ngāi Tahu/NZE environmental researchers/consultants.

Fishing in general as well as for consumption varied by area and participant group. Fishing was mentioned by a higher proportion of LPS (86%) than RP (50%) at R-SC (v²=29.63, DF = 1.0, p < .0001), similarly by both groups at RA and KR (29%–40% and 43%–50%, respectively; p > .05), and only by RP at AH (14%). Consumption was reportedly higher for LPS than RP at R-SC (86% and 45%, respectively; v²=37.01, DF = 1.0, p < .0001) and KR (100% and 67%, respectively; v²=39.32, DF = 1.0, p < .0001), while both groups were similar at RA (24% and 20%, respectively; p > .05), and only RP reported this at AH (19%).

Shellfish harvesting varied by area and participant group, which was reportedly higher at more rural areas, R-SC and KR (78%–81%), compared to AH and RA (31%–50%). Although harvesting for consumption was favoured by all Ngāi Tahu, they perceived that there were site-specific and species-specific restrictions, including poorer ecosystem conditions, especially at AH. Not many RP harvested shellfish (28%), which was mostly done at R-SC (11%) and KR (12%) compared to AH (5%). The rāhui bylaws were reportedly followed at RA and KR, whose shellfisheries were monitored/researched by LPS.

A significantly higher proportion of LPS (35%) compared to very few RP (7%) gathered inanimate objects at each area (p < .0001). Many LPS (88%) were affiliated with Ngāi Tahu and favoured resources such as greywacke rocks for hāngi/earth oven, mud to dye flax, and stones/shells for ornaments or gardens. RP and NZE LPS mostly gathered for ornamental purposes (e.g. shells, stones, sea china).

Swimming and walking/dog-walking were the most popular leisurely activities, although swimming was excluded at AH. Sitting and eating (i.e. picnics) were only mentioned at R-SC and RA and motorised boating/skiing at KR. Additionally, site-specific concerns were raised, including toxic algae and wading at R-SC and poor water quality at AH. Leisure was especially favoured by LPS than RP at R-SC (57% and 20%, respectively; v²=28.79, DF = 1.0, p < .0001), by RP than LPS at KR (67% and 50%, respectively v²=5.92, DF = 1.0, p < .005) and were similar between groups at AH and RA.

Fishery/shellfishery resources and abundance

The proportion of participants that favoured shellfish most commonly mentioned tuangi/tuaki/cockle (Austrovenus stutchburyi; 14%–100%) and pipi/taiwhatiwhati (Paphies australis; 5%–57%), while kūtai/saltwater mussels (multiple species; 20%–50%) were only mentioned at RA and KR. Favoured fish included pātiki/flounder (14%–71%) except at RA, while inanga/whitebait (Galaxias spp.; 35%–71%), tuna/freshwater eel (Anguilla spp.; 5%–71%) was only mentioned at R-SC, salmon/trout (spp.; 5%–43%) more so at R-SC, and ‘fish’ in general (5%–29%) was mentioned most often by RP, generally for catch-and-release purposes. Favoured species, such as cockles were not necessarily harvested at present due to perceived decreased abundances, gathering restrictions (rāhui) and/or poor environmental conditions (e.g. food-safety risks).

Although many LPS (87%) and nearly half of the RP (49%) perceived changes in relative fishery abundance, fewer participants (39% and 10%, respectively) were prepared to quantify this change. Some participants provided qualitative responses and suggested several preferred indicators of health, including fish/shellfish size and condition and catch over time. Overall, many LPS (74%) and fewer RP (20%) were concerned about shellfish compared to fish (52% and 30%, respectively). Also, Ngāi Tahu and experienced RP suggested site-specific concerns (e.g. declined tio/oysters at KR and RA and tuangi/cockles at RA, as well as site-specific food safety across estuaries).

Environmental condition and environmental changes

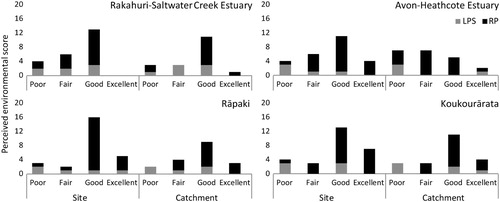

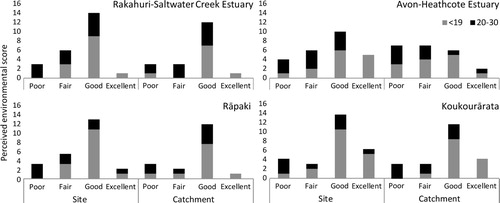

Many LPS (96%–100%) and RP (84%–89%) per area provided environmental condition scores for each area, which differed with participant experience. Perceived environmental condition generally scored positively, except for the AH catchment, which generally rated poor and fair (). Experienced participants (20–30 y) scored each site and catchment lower than less experienced participants (<19 y; ). This was illustrated by the negative correlation between participants’ experience with site (r = −0.39, p < .0001) and catchment scores (r = −0.39, p < .0001). Some of the participant scores were associated with environmental concerns (e.g. earthquake damage, fishery risks) while others were optimistic (e.g. through observing earthquake restoration), which may not reflect the current conditions.

Figure 2. Perceived environmental score by Local Practitioners and Specialists (LPS, n = 5–7) and Recreational Participants (RP, n = 20–21) at each site and catchment.

Figure 3. Perceived environmental score grouped by less experienced (<19 years, n = 45–50) and experienced participants (20–30 years, n = 34–38) at each site and catchment.

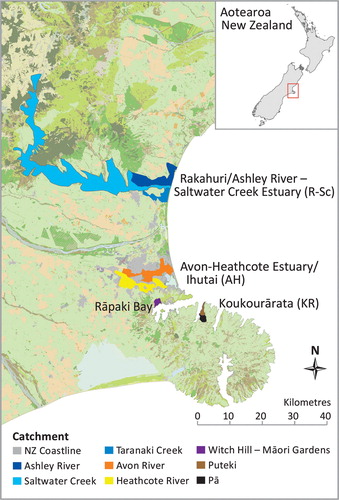

The perceived environmental changes () differed with participant experience and were scored similarly across most estuaries except R-SC. Many LPS (96%) and some RP (45%) agreed that the environment changes have occurred over time, while a few RP (7%) disagreed. Experienced participants recognised more changes over time, which was illustrated by the positive correlation between participants’ experience with environmental change scores (increased with number of changes mentioned; r = 0.61, p < .0001). Of the six commonly perceived changes, four were similar across estuaries: catchment (10%–15%), sediment (11%–16%), water flow (9%–13%) and pollution/contaminants (7%–11%); and two were mentioned less at R-SC: water quality (5%–15%) and earthquake-related impacts (2%–13%).

Environmental indicators

Participants provided up to 40 indicators that they utilised to inform their decision-making about their estuarine activities. These indicators were grouped into five categories: catchment, site condition, estuarine life, local presence/knowledge and management/practices (Supplementary Material). In general, more LPS than RP negatively scored land-use (11% and 1%, respectively), water clarity (17% and 0%, respectively), and sediment and contaminant indices (91% and 8%, 78% and 8%, respectively), and positively scored water flushing/input (26% and 0%, respectively). A higher proportion of LPS than RP scored fish/shellfish indices (43% and 17%), but the participant numbers were similar (n = 10 and n = 14, respectively), which was also observed for other water indices (e.g. water quality and flow, see the Supplementary Material).

Some participants, particularly experienced NZE and Ngāi Tahu, shared qualitative reasons for their scores. For instance, decreased water flow/volume (e.g. land drainage and water extraction) and contaminants have negatively-impacted Ngāi Tahu values. Holistic measures (e.g. cultural health) needed to be protected because ‘the food standard doesn’t provide an indigenous perspective of health’ (LPS). Some of the LPS associated septic tanks and farmland with contaminant/faecal coliform. Experienced NZE and Ngāi Tahu also utilised similar fish/shellfish-specific indices; for instance, higher salinity and tidal-flushing, good sediment quality and sensory cues were associated with healthier fish/shellfish indices and food health/safety. Ngāi Tahu LPS also utilised similar indices when re-seeding/transplanting shellfish, noting that this practice was not undertaken by all hapū. This contrasted with RP who were observed to harvest shellfish/fish at sites near freshwater and food-risk warning signage.

Management

Many LPS (96%) and some RP (39%) responded to the question of management effectiveness. Notably, shellfish harvesting restrictions differed across areas (section 2.2.). A higher proportion of participants agreed that management was effective (44% and 29%, respectively) as opposed to partially effective or ineffective (each 26% and 5%, respectively). Participants’ associated management effectiveness with adequate fishery regulations, amenities and a good community, while ineffective or partially effective management was associated with high harvesting allowances, policing issues, and complexity (e.g. multiple agencies who do not act/interact across land-to-sea systems). In addition, two RP who were tourist had overestimated the harvesting limits.

Discussion

Identifying and understanding the risks of environmental degradation on socio-cultural values is integral to the effective future management and accountability of anthropogenic activities in Aotearoa NZ estuaries. This research begins to address this by evaluating the indigenous and local socio-cultural values provided by estuarine shellfishery areas across Waitaha.

Ngāi Tahu estuarine values are similar with other indigenous people, in that their values and ancestry are inherently interconnected with the environment (Sheehan Citation2001; Flanagan & Laituri Citation2004; Jackson Citation2005), as encapsulated and emphasised by whakapapa: the familial connection of Māori with the environment and its resources (Tomlins-Jahnke & Forster Citation2015). Like the indigenous people of Australia, these values are not compartmentalised (Jackson Citation2006), which contrasts with the dominant way of thinking within contemporary legislation and policy in Aotearoa NZ and Australia (Harmsworth Citation2005; Jackson Citation2006; Davis Citation2008). It is evident that contemporary management and anthropogenic inputs have impacted the ability of Ngāi Tahu hapū to actively practice their estuarine values.

Mahinga kai (inclusive of site, species, and practice) is an important Cultural Health Indicator (CHI) for many hapū/iwi (Tipa & Teirney Citation2003; Schweikert et al. Citation2013; Taiapa et al. Citation2014; Faulkner & Faulkner Citation2017). In this research, experienced fishers changed or ceased their practices due to their perceptions of poorer environmental conditions. Although shellfisheries and fisheries were favoured by many LPS, there were perceived site-specific restrictions due to anthropogenic or natural (earthquake-related) impacts, and/or declining abundances. Impacts on estuarine and coastal water quality is also evident in other areas of Aotearoa NZ having led to the long-term restriction of human contact or food consumption (Ministry for the Environment Citation2012). Experienced Māori and NZE participants’ who were interviewed across Te Wai Pounamu also experienced that inshore seafood catches were more difficult overtime with marked declines occuring from the 1970s (McCarthy et al. Citation2014). This is concerning given the ancestral importance of shellfisheries as indigenous cultural-ecological systems (Niupepa Citation1894; Best Citation1929; Smith Citation2013).

Rather than purely number-based, both Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) ‘data’ is accumulated from many years of observation and form a qualitative mental model (e.g. population trends and animal health/condition) towards their decision-making (Berkes & Berkes Citation2009; Berkes Citation2012). There were limitations in capturing changes in perceived relative fishery/shellfishery abundance over time, although there was consensus amongst Ngāi Tahu participants or experienced fishers (Ngāi Tahu and NZE) regarding fishery/shellfishery densities or poorer conditions. These also corresponded with biophysical study findings, such as low tio/oyster densities or poorer shellfish condition/safety near freshwater input (Murchie Citation2017). Difficulties in describing perceived changes in abundance could be due to place-based restrictions (e.g. perceived poor conditions), a high proportion of participants with minimal experience (47% of the participants had ≤4-years interaction with an estuary), and the use of percentages to quantify relative abundance may not normally be used by participants.

The environmental condition and change scores were influenced by participant experience. A study that compared environmental perception in Aotearoa NZ found that NZ-born participants had significantly more negative views/experiences than those born abroad, and Māori had more negative views/experiences than NZ-born participants for nearly all environments (Kerr et al. Citation2016). In addition, cultural affiliation comparisons found NZE scored higher than Ngāi Tahu at R-SC and both scoring poorly at AH (Murchie Citation2017). It is recommended that socio-cultural values need to distinguish between NZ-born, local and non-local tribal affiliations, as the long-term mātauranga about a particular place is held by local iwi/hapū.

The environmental indices commonly utilised by participants were similar with global estuarine stressors. For instance, major estuarine stressors such as sewage/organic waste, chemical contaminants, and sediment/particulate inputs (Kennish et al. Citation2014) were used by LPS, alongside water attributes, as environmental indices. These environmental stressors can negatively affect estuarine condition, benthic communities and biodiversity (Kennish Citation1997; Edgar & Barrett Citation2002). Ngāi Tahu are averse to taking food from polluted waters, especially water bodies receiving treated and untreated sewage (Tau et al. Citation1992), which is one reason for extending the RA rāhui and avoiding AH. This contrasted with a few RP who harvested/fished in areas of elevated food risks. Concerning, the AH waterways have experienced elevated faecal indicator levels during the Canterbury earthquakes (McMurtrie Citation2012) and prior to this, had received storm water input and pre-2010 treated sewage discharge (Batcheler et al. Citation2009; McMurtrie Citation2010; McMurtrie Citation2012). Hence, the Ngāi Tahu CHI assessment within the AH was scored poorly before and after the Canterbury earthquakes (Pauling et al. Citation2007; Lang et al. Citation2012). In addition, management has been contended recently due to the dumping of Canterbury earthquake-related waste near Te Akaaka Fishery Easement Māori Reserve 896 at R-SC (T.M. Tau, Environmental Court 2016) and due to long-term surrounding land development and land uses (Tau Citation2017).

More holistic and participatory approaches with experienced community and mana whenua are needed to inform the improved management of estuarine systems. It has been suggested that both the sciences and social sciences (including community engagement, Māori values, and policy) should be drawn upon to inform integrated catchment management (Phillips et al. Citation2010; Fenemor et al. Citation2011; Hickey-Elliott Citation2014). Participatory approaches are essential towards embedding management in local and indigenous knowledge and practices (Tipa & Nelson Citation2008; Lyver et al. Citation2016; Sterling et al. Citation2017; McCarter et al. Citation2018). This current study argues that mātauranga Māori and local ecological knowledge of experienced residents are essential. Similar to the Anishinaabe First Nation People of Canada, knowledge is embedded in the land and the people, which requires constant interaction with the land, and maintenance of a web of relationships between people and places (Davidson-Hunt & Berkes Citation2003). This also supports the hypothesis that without intact systems and environmental resources, indigenous peoples cannot nurture these socio-ecological relationships (Simpson Citation2005; McCarthy et al. Citation2014) and iwi cannot uphold kaitiakitanga, which embraces social and environmental guardianship, stewardship, and resource management (Wright et al. Citation1995; Kawharu Citation2000).

Recently, a ki uta ki tai framework has been proposed to underpin the restoration of the Whakaraupō/Lyttelton Harbour, in partnership between Ngāi Tahu hapū and iwi rūnanga, industry, and local authorities (Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke et al. Citation2018). This aligns with the local councils objective to achieve an integrated ‘ki uta ki tai and beyond approach’ to implementing water management from mountain-to-sea by 2020 (Canterbury Water Citation2012; Environment Canterbury Citation2015). This Ngāi Tahu environmental ethic acknowledge both the biophysical connectivity and the reciprocal relationship between people and the environment (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Citation2003; Tipa et al. Citation2016). Therefore, the methods developed in this research could be used to help this partnership better understand and protect socio-cultural values of estuarine health within increasingly anthropogenic systems, towards meeting the ethic of ki uta ki tai.

Conclusion

This research contributes to our understanding of indigenous and local socio-cultural values provided by estuarine shellfisheries across Waitaha. Across generations, Ngāi Tahu estuarine values have been impacted by anthropogenic input and exclusion from decision-making. The environmental indices commonly utilised by participants were similar with global estuarine stressors, which were associated with perceived poorer condition. This has led to experienced participants who no longer gather/fish favoured shellfishery/fishery resources at certain sites, compared to some less experienced participants who gathered in high food-risk sites. Improved management necessitates participatory approaches to better implement the ethic of ki uta ki tai, which acknowledges both the connectivity between land-to-sea and people with the environment.

Supplementary Material Interview forms and Environmental indices

Download MS Word (67 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support and knowledge provided by the participants who were interviewed during this research. Thank you to Toni Wi, who assisted with local recreational surveys, and to NIWA colleagues Dr Erica Williams, Dr Kathryn Davies, Erina Watene-Rawiri, and Aarti Wadhwa for your support and assistance with this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Ani Alana Kainamu-Murchie http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8055-879X

Sally Gaw http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9556-3089

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson A. 1998. The welcome of strangers: an ethnohistory of Southern Māori AD 1650-1850. Dunedin: The University of Otago Press.

- Barbier EB, Hacker SD, Kennedy C, Koch EW, Stier AC, Silliman BR. 2011. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological Monographs. 81(2):169–193. doi: 10.1890/10-1510.1

- Batcheler L, Bolton-Ritchie L, Bond J, Dagg D, Dickson P, Drysdale A, Handforth D, Hayward S. 2009. Healthy Estuary and Rivers of the City. Water quality and ecosystem health monitoring programme of Ihutai. Environment Canterbury Regional Council, Kaunihera Taiao ki Waitaha 72 p.

- Beattie JH. 1994. Traditional lifeways of the southern Māori. Dunedin: Otago University Press in association with Otago Museum.

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological. 57(1):289–300.

- Berkes F. 2012. Sacred ecology. New York: Routledge.

- Berkes F, Berkes MK. 2009. Ecological complexity, fuzzy logic, and holism in indigenous knowledge. Futures. 41(1):6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.003

- Best E. 1929. Fishing methods and devices of the Māori. Wellington: Dominion Museum.

- Canterbury Maps. 2015. Sub-region boundaries, catchments, and rivers. Online database accessed 28 August 2016 https://canterburymaps.govt.nz/. Canterbury, New Zealand.

- Canterbury Water. 2012. Canterbury Water Management Strategy. Final Regional Implementation Programme Including Annex. Canterbury Regional Water Management Committee 58 p.

- Clough P. 2013. The value of ecosystem services for recreation. In: Dymond J, editor. Ecosystem services in New Zealand–conditions and trends. Lincoln: Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare New Zealand; p. 330–342.

- Costa-Pierce BA. 1987. Aquaculture in ancient Hawaii. BioScience. 37(5):320–331. doi: 10.2307/1310688

- Dacker B. 1994. Te Mamae me te Aroha, The pain and the love: a history of Kai Tahu Whanui in Otago, 1844-1994. Dunedin: The University of Otago Press.

- Davidson-Hunt I, Berkes F. 2003. Learning as you journey: Anishinaabe perception of social-ecological environments and adaptive learning. Ecology and Society. 8(1):5.

- Davis M. 2008. Indigenous knowledge: beyond protection, towards dialogue. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. 37(S1):25–33. doi: 10.1375/S132601110000034X

- Dick J, Stephenson J, Kirikiri R, Moller H, Turner R. 2012. Listening to the Kaitiaki: consequences of the loss of abundance and biodiversity of coastal ecosystems in Aotearoa New Zealand. MAI Journal. 1(2):14.

- Edgar GJ, Barrett NS. 2002. Benthic macrofauna in Tasmanian estuaries: scales of distribution and relationships with environmental variables. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 270(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00014-X

- Environment Canterbury. 2015. Canterbury Land and Water Regional Plan. Volume 1. Environment Canterbury Regional Council, Kaunihera Taiao ki Waitaha 384 p.

- Faulkner R, Faulkner L. 2017. Marine Cultural Health Indicator Report. Tū Taiao Ltd, Department of Conservation, Ngāi Toa Rangatira, Greater Wellington Regional Council 17 p.

- Fenemor A, Phillips C, Allen W, Young RG, Harmsworth G, Bowden B, Basher L, Gillespie PA, Kilvington M, Davies-Colley R, et al. 2011. Integrated catchment management—interweaving social process and science knowledge. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 45(3):313–331. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2011.593529

- Flanagan C, Laituri M. 2004. Local cultural knowledge and water resource management: The Wind River Indian Reservation. Environmental Management. 33(2):262–270. doi: 10.1007/s00267-003-2894-9

- Ghermandi A, Nunes PA, Portela R, Rao N, Teelucksingh SS. 2009. Recreational, cultural and aesthetic services from estuarine and coastal ecosystems. Nota di lavoro/Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei: Sustainable development 67 p.

- Goodman LA. 1961. Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 32:148–170. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177705148

- Goodrick D, Emmerson G. 2009. Using Mixed Methods in Research and Evaluation New Zealand, New Zealand Social Statistics Network (NZSSN) Course Booklet (18th–22nd Feburary 2013).

- Handy E, Handy E, Pukui M. 1972. Native planters in old Hawaii: their life, lore, and environment. Honolulu: Hawaìi, Bishop Museum Press. 641 p.

- Harmsworth G. 1997. Māori values for land use planning. New Zealand Association of Resource Management (NZARM) Broadsheet. 97:37–52.

- Harmsworth G. 2005. Good practice guidelines for working with tangata whenua and Māori organisations: Consolidating our learning. Landcare Research 56 p.

- Hart DE, Bryan KR. 2008. New Zealand coastal system boundaries, connections and management. New Zealand Geographer. 64(2):129–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7939.2008.00133.x

- Hepburn CD, Newman J, Moller H. 2011. Ecosystem health within Koukourārata Mātaitai 2008-2010. Dunedin, New Zealand: Te Tiaki Mahinga Kai, University of Otago. 44 p.

- Hickey-Elliott AB. 2014. An integrated catchment management plan toward restoration: sustainable farming with a future focus in the Mangaone West. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Hughey K, Kerr G, Cullen R. 2016. New Zealanders’ perceptions of the state of marine fisheries and their management. Lincoln: Lincoln University. 90 p.

- Jackson S. 2005. Indigenous values and water resource management: a case study from the Northern Territory. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management. 12(3):136–146. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2005.10648644

- Jackson S. 2006. Compartmentalising culture: the articulation and consideration of indigenous values in water resource management. Australian Geographer. 37(1):19–31. doi: 10.1080/00049180500511947

- Kawharu M. 2000. Kaitiakitanga: a Māori anthropological perspective of the Māori socio-environmental ethic of resource management. The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 109(4):349–370.

- Kennish MJ. 1997. Pollution impacts on marine biotic communities. Washington, DC: CRC Press.

- Kennish MJ. 2016. Encyclopedia of estuaries. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. 789 p.

- Kennish MJ, Brush MJ, Moore KA. 2014. Drivers of change in shallow coastal photic systems: an introduction to a special issue. Estuaries and Coasts. 37(1):3–19. doi: 10.1007/s12237-014-9779-4

- Kerr GN, Hughey KF, Cullen R. 2016. Ethnic and immigrant differences in environmental values and behaviors. Society & Natural Resources. 29(11):1280–1295. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1195029

- Lang M, Orchard S, Falwasser T, Rupene M, WIlliams C, Tirikatene-Nash N, Couch R. 2012. State of the Takiwā 2012, Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and its Catchment. Mahaanui Kurataiao Ltd Toru. 48 p.

- Lee J. 2009. Decolonising Māori narratives: Pūrākau as a method. MAI Review. 2(3):79–91.

- LINZ. 2015. New Zealand coastline data service. Accessed 28 August 2016 http://data.linz.govt.nz. New Zealand.

- LRIS. 2012. Land use land cover of New Zealand. Accessed 28 August 2016 https://lris.scinfo.org.nz. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Lyver POB, Akins A, Phipps H, Kahui V, Towns DR, Moller H. 2016. Key biocultural values to guide restoration action and planning in New Zealand. Restoration Ecology. 24(3):314–323. doi: 10.1111/rec.12318

- McCarter J, Sterling EJ, Jupiter SD, Cullman GD, Albert S, Basi M, Betley E, Boseto D, Bulehite ES, Harron R, et al. 2018. Biocultural approaches to developing well-being indicators in Solomon Islands. Ecology and Society. 23(1):32. doi: 10.5751/ES-09867-230132

- McCarthy A, Hepburn C, Scott N, Schweikert K, Turner R, Moller H. 2014. Local people see and care most? Severe depletion of inshore fisheries and its consequences for Māori communities in New Zealand. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 24(3):369–390. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2378

- McDonald JH. 2009. Handbook of biological statistics. Maryland: University of Delaware, Sparky House Publishing. 313 p.

- McMurtrie S. 2010. Heavy metals in fish and shellfish from Christchurch rivers and estuary: 2010 survey. EOS Ecology, Environment Canterbury Regional Council, Kaunihera Taiao ki Waitaha 14 p.

- McMurtrie S. 2012. Heavy metals in fish and shellfish: 2012 survey. EOS Ecology 17 p.

- Memon P, Sheeran B, Ririnui T. 2003. Strategies for rebuilding closer links between local indigenous communities and their customary fisheries in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Local Environment. 8(2):205–219. doi: 10.1080/1354983032000048505

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Ministry for the Environment. 2012. Water quality in New Zealand: understanding the science. Wellington, New Zealand: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Ministry for the Environment. 93 p.

- Murchie A. 2017. ‘Mauka makai’ ‘Ki uta ki tai’: The ecological and socio-cultural values of estuarine shellfisheries in Hawaìi and Aotearoa New Zealand. PhD in Environmental Science. Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, The University of Canterbury. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Niupepa. 1894. Reta Tuku Mai ki te Etita. Accessed 2016 http://www.nzdl.org/. Huia Tangata Kotahi.

- Patterson J. 1994. Māori environmental virtues. Environmental Ethics. 16(4):397–409. doi: 10.5840/enviroethics19941645

- Pauling C, Lenihan TM, Rupene M, Tirikatene-Nash N, Couch R. 2007. State ot the Takiwā, Te Āhuatanga o Te Ihutai: Cultural Health Assessment of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary and its Catchment. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Toru. 76 p.

- Phillips C, Allen W, Fenemor A, Bowden B, Young R. 2010. Integrated catchment management research: lessons for interdisciplinary science from the Motueka Catchment, New Zealand. Marine and Freshwater Research. 61(7):749–763. doi: 10.1071/MF09099

- Poepoe KK, Bartram PK, Friedlander AM. 2003. The use of traditional Hawaiian knowledge in the contemporary management of marine resources. Fisheries Center Research Reports. 11(1):328–339.

- Schiel DR, Howard-Williams C. 2016. Controlling inputs from the land to sea: limit-setting, cumulative impacts and ki uta ki tai. Marine and Freshwater Research. 67(1):57–64. doi: 10.1071/MF14295

- Schweikert K, McCarthy A, Akins A, Scott N, Moller H, Hepburn C, Landesberger F. 2013. A marine cultural health index for sustainable management of mahinga kai in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Dunedin, New Zealand, Te Tiaki Mahinga Kai, University of Otago. No. 15, p 88.

- Sheehan J. 2001. Indigenous property rights and river management. Water Science and Technology. 43(9):235–242. doi: 10.2166/wst.2001.0548

- Simpson LR. 2005. Anticolonial strategies for the recovery and maintenance of indigenous knowledge. The American Indian Quarterly. 28(3):373–384. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2004.0107

- Smith I. 2013. Pre-European Māori exploitation of marine resources in two New Zealand case study areas: species range and temporal change. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 43(1):1–37. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2011.574709

- Smith MK, Pai M. 1992. The Ahupua’a concept: relearning coastal resource management from ancient Hawaiians. The ICLARM quarterly. Naga. 15(2):11–13.

- Sterling EJ, Filardi C, Toomey A, Sigouin A, Betley E, Gazit N, Newell J, Albert S, Alvira D, Bergamini N, Blair M, Boseto D, et al. 2017. Biocultural approaches to well-being and sustainability indicators across scales. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1(12):1798. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0349-6

- Taiapa C, Hale L, Ramka W, Bedford-Rolleston A. 2014. A Framework for the Development of a Coastal Cultural Health Index for Te Awanui, Tauranga Harbour. Manaaki Taha Moana Research Report No. 16., Massey University 94 p.

- Tau TM. 2017. Water Rights for Ngāi Tahu: A Discussion Paper. Ōtautahi, Aotearoa New Zealand, Canterbury University Press, Ngāi Tahu Research Centre. 67 p.

- Tau T, Goodall A, Palmer D, Tau R. 1992. Te Whakatau Kaupapa: Ngāi Tahu resource management strategy for the Canterbury Region. Wellington: Aoraki Press.

- Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke, Canterbury Regional Council, Lyttelton Port Company Limited, Christchurch City Council, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, Tiaki T. 2018. Whaka-ora, Healthy Harbour, Ki Uta Ki Tai. Whakaraupō/Lyttelton Harbour as mahinga kai–warpping our environment in a protectic korowai for us, and our children after us http://healthyharbour.org.nz. Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. 2003. Ki Uta Ki Tai–Mountains to the Sea Natural resource Management: A scoping document for developing Mountains to the Sea Natural Resource Management Tools for Ngāi Tahu Christchurch, New Zealand, A draft prepared by Kaupapa Taiao for ngā Papatipu Rūnanga, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. 42.

- Thrush SF, Townsend M, Hewitt JE, Davies K, Lohrer AM, Lundquist C, Cartner K, Dymond J. 2013. The many uses and values of estuarine ecosystems. In: Dymond JR, editor. Ecosystem services in New Zealand–conditions and trends. Lincoln: Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research; p. 226–237.

- Tipa G, Harmsworth G, Williams E, Kitson J. 2016. Integrating mātauranga Māori into freshwater management, planning and decision-making. Advances in freshwater research. New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Publication, Wellington, New Zealand: 613-631.

- Tipa G, Nelson K. 2008. Introducing cultural opportunities: A framework for incorporating cultural perspectives in contemporary resource management. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 10(4):313–337. doi: 10.1080/15239080802529472

- Tipa G, Teirney L. 2003. A Cultural Health Index for Streams and Waterways: Indicators for recognising and expressing Māori values. Ministry for the Environment 72 p.

- Tomlins-Jahnke H, Forster M. 2015. Waewaetakamiria: caress the land with our footsteps. In: Huaman E, Sriraman B, editor. Indigenous innovation: universalities and peculiarities. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers; p. 43–55.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 1987. Wai 27. Ngāi Tahu claim to Mahinga Kai. Part one: Report on Ngāi Tahu Fisheries Evidence. Waitangi Tribunal, Department of Justice, Tāhū o te Ture, and Southpac Fisheries Consultants 566 p.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 1992. The Ngāi Tahu Sea Fisheries Report 1992 Accessed 29 May 2016 https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68472628/NT%20Sea%20Fisheries%20W.pdf. Wellington, New Zealand.

- Walker D. 2009. Iwi Estuarine Indicators for Nelson. Nelson, Tiakina te Taiao. 22.

- Williams J. 2016. Seafood ‘gardens’. The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 125(4):433–444. doi: 10.15286/jps.125.4.433-444

- Wright SD, Nugent G, Parata HG. 1995. Customary management of indigenous species: a Māori perspective. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 19(1):83–86.