ABSTRACT

Why have mangroves and their ecosystems been so hotly contested over the last quarter century in Aotearoa New Zealand’s northern waters? Central to ‘mangrove mania’ are multiple, competing and often antagonistic perceptions of the perceived risks posed by mangrove presence, their removal and efforts to restore them. Not surprisingly this has led to a chaotic mangrove knowledge space, with significant gaps in knowledge required to understand risks associated with mangrove management. In a socio-ecological investigation of risk questions relating to the mangrove debate, we reveal how localised contestations of mangroves have been ‘arbitrated’ – in different directions. This state of affairs has resulted from several critical threads: from many sources, pressures and intentions, but all involving the often ill-specified lens of public opinion, science practice, environmental management procedures, Māori knowledge, community views, land and inshore development, and consenting processes. We systematically examine the trajectory of these critical threads and their interactions, underlying the mangrove debate and the resulting variability in how risks are portrayed. Our evidence suggests that perceived risk of mangrove expansion, and of mangrove removal impacts, is contested and linked to different desired and imagined futures.

Introduction

Temperate mangroves are indigenous to northern Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa NZ) and present an unusual case where mangroves have shown rapid expansion in recent decades, compared to ongoing declines in most global tropical mangrove forests (Morrisey et al. Citation2010; Lundquist et al. Citation2014b). The narratives surrounding mangrove (Avicennia marina var. australasica) ecosystems over the 25 years are a multi-dimensional juxtaposition of assumptions, perceptions and evolving knowledge set against changing coastal landscapes. While some view mangroves as an invasive ‘coastal weed’ that impacts property values, harbour access and other more ‘valuable’ coastal plant communities, others consider mangroves to be valuable natural ecosystems that require protection (Dencer-Brown et al. Citation2018). Complicated by gaps in scientific knowledge regarding the ecological role of mangroves in Aotearoa NZ and the impacts of removal on estuary ecosystems, the contrasting positions and perceptions have played out in the media, local government processes and within communities.

Smith (Citation2018) suggests that ‘Bringing up the subject of mangroves may be the biggest social faux pas for any chat around the barbecue on the Coromandel’ primarily because of the polarised positions held by different individuals and groups. So how did we get to this? Early discontent with the presence of mangroves at certain locations emerged somewhere in the late 1990s/early 2000s (Horstman et al. Citation2018), because mangroves were thought to be in a place ‘they shouldn’t be’, and as a result were impacting recreation and amenity value of local residents and other participants in estuary-based water activities. Baker (Citation2018) quotes a local resident, ‘I remember when I was at high school in 1957 when we'd bike down the road by the club and swim at the beach every day in summer. It was a shell sand beach and the water was pristine’. Small estuary-care groups formed across the upper North Island, whose core purpose appeared to be mangrove removal to restore beaches to what they once were – a remembered ideal historical state. Almost concurrently, international mangrove conservation organisations and networks were gaining momentum and seeking to cement the ecological, cultural, social and economic values of tropical mangrove communities in planning and practice and to reverse habitat loss (Spalding et al. Citation2010; Friess et al. Citation2012).

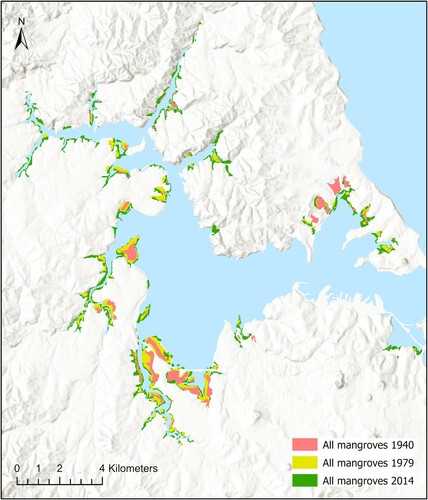

The early management of Aotearoa NZ mangrove systems was limited by gaps in understanding of the role, function and value in the coastal marine area (Morrisey et al. Citation2010). Gaps were often filled by (mis)assumptions based on tropical mangroves. However, research, often in response to mangrove management consenting processes, has filled many of these gaps and quantified differences between roles, functions and ecosystem services provided by Aotearoa NZ’s mangroves. Evidence of mangrove expansion (see, e.g., increase from 1940 to 2014 Waitemata Harbour, central Auckland ; Suyadi et al. Citation2019) also led to research to determine causal links between land-based sediment inputs and mangrove expansion rates (Morrisey et al. Citation2010; Swales et al. Citation2015; Suyadi et al. Citation2019). At the same time, there have been on-going applications by various community groups to remove mangroves (Lundquist et al. Citation2014a), and mixed messages from the Resource Management Act (1991) and Coastal Policy Statement (2010) regarding the protection status of native NZ mangroves.

Figure 1. Change in mangrove distributions in Waitemata Harbour, central Auckland, from 1940 to 2014 (data from Suyadi et al. Citation2019).

Previous researchers have discussed the science (Morrisey et al. Citation2010) and polarisation of the mangrove debate, with a focus on knowledge and contested perspectives (Harty Citation2009; Horstman et al. Citation2018), and attitudes towards mangroves (Dencer-Brown et al. Citation2018; Maxwell Citation2018; Dencer-Brown et al. Citation2019). We offer a reframing of existing knowledge on the mangrove management debate by interrogating what is ‘perceived to be a risk’ by the various groups involved. This novel reframing and re-appraisal offer a more nuanced understanding of the multiple perspectives on removal as well as the on-going influence of science and policy. This is important because the current approaches have described the differences and conflicts surrounding mangrove management (what is disputed) rather than exposing the underlying reasons for these differences (why it is disputed). We provide new insights by asking the question ‘are the perceived risks from mangroves to differing desired future states, actually what is at the centre of the conflict?’ That is to say, do the different estuary environments that people want in the future, play a significant role in how risk is perceived? Different mangrove management options become much more ‘risky’ if they interfere with a desired future state.

Reframing the mangrove debate through a ‘perception of risk’ lens – an alternative approach

Our reframing and reappraisal of the mangrove management debate have been informed by a mixed-method approach using local and international literature reviews, analysis of secondary documents (reports, policy and plans, media webpages, evidence statements from consent processes under the RMA) and supported by first-hand author experiences as researchers and practitioners in the evolving debate over harbour and estuary uses over nearly three decades.

For our inquiry, we describe the perception of risk as to the way that individuals (institutions, communities, groups, iwi and hapū) understand and expect to experience the impact/implications of an event or change or action to/on something they value (e.g. a place or activity, or relationship) or a desired future outcome.

Our investigative strategy is threefold: first, we identify three key influences on the perception of risk as experienced, imagined and stated by stakeholders connected with mangrove management; second, we develop a timeline to highlight the critical threads and their interactions that have impacted mangrove perspectives and management strategies in Aotearoa NZ over time, such as progressive international and local scientific knowledge, and changes in mangrove abundance over time and space. Third, by describing this complex evolution of events and the critical threads and their interactions underpinning the mangrove debate, we seek to expose the role that risk perception has, and continues to play, in mangrove management.

Underlying influences on risk perception

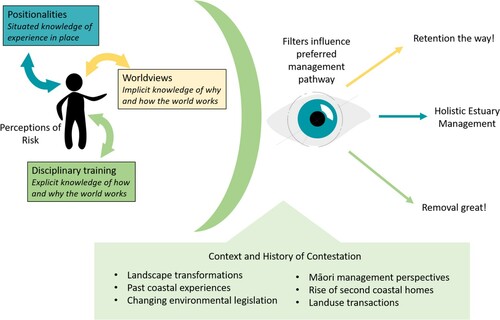

Our previous research (Blackett et al. Citation2021, Le Heron et al. Citationsubmitted) has identified that risk perception is underpinned by three key areas of influence: positionality, disciplinary training and worldviews. These three ‘invisible’ areas of influence operate simultaneously and play a key and often underappreciated role in shaping responses and in the assessment of what is ‘risky’.

Positionality refers to how people are engaging directly in their environment and everyday world and is related to their situation, lived experiences and interests and objectives are. Positionality is a common concept in the social sciences for further information see Warf (Citation2010). An example is coastal property owners who have a strong interest in their immediate surrounding environment and how changes affect things that are of value to them, e.g. buildings natural environments or facilities.

Disciplines are ‘training grounds in thought’ and have led to diverging starting points regarding how to define risk and how to put such knowledge to use. For example, biophysical sciences business analysis and lawyers are trained to think differently about what risk is and how it can be known and described.

Worldviews impact how we think the world works, should work and might be made to work. In the Aotearoa NZ context, we have identified three dominant worldviews:

‘dominant social paradigm’ (DSP) mandates doing things for one’s self and values highly, profit making, and views the world’s resources and human ingenuity as limitless (Dunlap and Liere Citation1984; Dunlap et al. Citation2000; Thomson Citation2013);

‘new environmental/ecological paradigm’ (NEP) that gives priority to preserving ecological processes in harmony with people, and views the world's resources as limited (Dunlap and Liere Citation1984; Dunlap et al. Citation2000; Thomson Citation2013);

‘Te Ao Māori worldview’ that grounds principles and actions in place, relating to people and ecology for collective short and long-term benefits (Harmsworth et al. Citation2013; Harmsworth et al. Citation2016).

offers a static snapshot to unpack that these three underlying influences of risk perception act as interreacting simultaneous filters through which mangrove-related decisions are considered. Later in the paper, we ask what more could be possible if these influences of risk perceptions are identified up-front in decision-making processes. The critical threads and their interactions at work here include co-governance arrangements environmental regulations and policy, council rulings, community group actions and dynamics and Māori management perspectives.

The relationship between perceptions of risk and mangrove management is not a logical or necessarily linear problem to solve. It is grounded in context, history and scale. It is messy. The diagram is a necessary simplification to identify some of the crucial and overlooked elements involved in re-framing and re-appraising risk. Next, we present the evolution of the mangrove debate through time and identify the critical threads that have impacted the varied risk perceptions of mangroves.

The changing Aotearoa New Zealand coastal landscape and the mangrove debate: critical threads through time

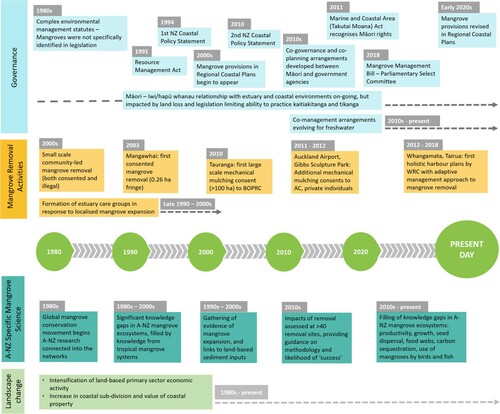

Aotearoa NZ’s coastal landscape has undergone a series of transformations, from the early settlement by Māori, to the emergence of holiday homes in the 1950s, and the on-going gentrification of many northern coastal beaches and estuaries (Horstman et al. Citation2018). Further, our coastal environments will change again as climate change influences the form and function of our coastal lowlands and estuaries (Swales et al. Citation2008; Lundquist et al. Citation2011; McBride et al. Citation2016). This backdrop is important as it provides the stage from which the contested values and risks of mangroves have emerged. These estuarine wetland systems are receiving increasing attention with respect to future risk of decline due to coastal hazards and sea level rise associated with climate change, particularly in recognition of the potential loss of valuable ecosystem services like carbon sequestration. The critical threads underlying this debate are described here and illustrated in .

Māori settlement of the coasts:

Māori have a holistic approach to environmental management. This approach – based on Māori principles and practices – was refined through a close association and respect for the environment. Māori view humans as part of the natural environment that is both material and spiritual, living in a unified socio-spiritual-ecology (Rout et al. Citation2021). At the core of Māori relationships with the environment is the ethic of kaitiakitanga or intergenerational care over the environment. Māori have a timeless responsibility to actively care for their human and nonhuman community; to act with mana (authority and respect), to cherish the natural environment’s tapu (sacredness) and maintain its mauri (life force) (Harmsworth et al. Citation2013; Rout et al. Citation2021). Following colonisation, Māori suffered a loss of mana as land was sold below market rate or stolen and, after massive deforestation and significant loss of native flora and fauna, Aotearoa NZ’s tapu was desecrated and its mauri reduced (Rout et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, the ability of hapū/iwi to enact kaitiakitanga was diminished.

Recent developments in Aotearoa NZ have seen the development of co-governance arrangements between Māori and government agencies for several marine management agreements (see, e.g. Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari (Waikato Regional Council Citation2017; Te Korowai o te Tai ō Marokura Citation2012 and the Integrated Kaipara Harbour Management Group Citation2022). Co-governance arrangements in Aotearoa NZ are formal decision-making agreements between Māori and the NZ government and are based on the Treaty of Waitangi (Maxwell et al. Citation2020a). The treaty provides foundational principles for meaningful partnerships between hapū/iwi and government agencies (Harmsworth et al. Citation2016). Co-management arrangements consider how Māori and government agencies collectively determine the outcomes for ecosystems and the implementation processes required to achieve the desired state (Harmsworth et al. Citation2016). This process usually involves the consideration of Māori values within planning documents. Generally, these plans are concerned with improving the overall mauri (life force) of an ecosystem for collective benefit and are less concerned with managing the aesthetic risk to individual well-being. There is a growing realisation by civil society that understanding Māori views and beliefs is essential for natural resource management decisions (Harmsworth et al. Citation2013). Concerted efforts are being made to adequately acknowledge Māori rights and interests in the co-management of natural resources (Harmsworth et al. Citation2016; Makey and Awatere Citation2018; Maxwell et al. Citation2020b) such as the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011. However, the New Zealand planning conundrum is that while civil society expresses a willingness to work with Māori worldviews, the capability to meaningfully commit to a Māori planning perspective resides with hapū/iwi planners or kaitiaki constrained by capacity. Entities representing Māori interests (e.Rūnanga and Trusts, etc.) are similarly stretched for capacity and resources and must make choices about how and where to engage. This often leads to an underrepresentation of Māori interests in local-level decisions.

European settlement and the expansion of agriculture and horticulture

Mangrove expansion has been linked to land-based sediment inputs due to catchment development to support urbanisation and agricultural development following European colonisation of Aotearoa NZ, including land reclamation and construction of causeways, marinas, landfills, ports and other coastal structures (Dingwall Citation1984; Crisp et al. Citation1990; Morrisey et al. Citation2010). Aerial images have further supported timelines of mangrove expansion, and correlations with catchments development (Swales et al. Citation2015; Suyadi et al. Citation2019).

The environmental movement

Concern regarding the environmental impacts of land-based primary sector economic activity (and dairy-farming in particular), biodiversity and estuarine habitat degradation and loss grew during the 1990s (Crisp et al. Citation1990). Public concern has often translated into increased support of independently funded care groups (streamcare, landcare, estuary care) and environmental advocacy groups (e.g. Forest and Bird, Fish and Game). Community groups and primary industry initiatives and self-regulation have begun to shift land management practices and expectation through stream fencing and planting programmes and farm environmental management plans, e.g. Clean Streams Accord (Fonterra Co-operative Group et al. Citation2003). Biodiversity and care groups have adopted very active roles in the protection and enhancement of locally and nationally valued natural environments.

Settlements and second homes at the coast

The increase of coastal settlements and second home ownership that began in the post-war period (1950s) is attributed by Walters (Citation2019) to the introduction of government-mandated leisure time, better roads, more disposable income and increased middle-class motor vehicle ownership supporting greater mobility. Initially, coastal dwellings were modest (Peart Citation2009), however, wealth accumulation over the following decades has fuelled a buoyant real estate market and led to on-going development, sub-division and gentrification of the coastline, particularly in areas with high amenity value. Multi-million-dollar properties at favoured coastal locations are now the norm rather than the exception. In short, coastal property now represents a significant financial investment and many homeowners hold long associations with specific coastal spaces. Further, there appears to be a set of expectations regarding the maintenance of enjoyed environmental, social and economic settings and uses at the coast. There is a perception that the status quo will remain, or be improved, particularly as regards property values and investments (Blackett et al. Citation2010).

Shifts in environmental legislation

Environmental reform co-evolved with the public and private sector reforms of the mid-1980s to early 1990s. The reforms aimed to streamline a complex plethora of statutes across multiple acts into the Resource Management Act (1991) and implement a more local and effects-based set of policies and plans. As part of the package of reforms, central government stepped away from day-to-day environmental management, leaving the role to City, District, and Regional Councils and Unitary Authorities, while taking account of increased public environmental concern.

Activities in the coastal marine environment are governed by the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (2010) which is given effect to by Regional Policy Statements, Regional (Coastal) Plans and finally District Plans. The NZCPS (2010) provides a series of objectives and policy to guide activity but does not specifically refer to mangroves. It does, however, have objectives and policies giving direction to avoid adverse impacts on indigenous vegetation and retention of public enjoyment, amenity and use of marine environments). Interestingly, the management of coastal wetlands (like mangroves) has potentially shifted with the recent Freshwater Reforms culminating in the National Freshwater Standards (NFS) and National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM) that both came into force in 2020. The new legislation further opens the door to integrated mountains to the sea management of rivers and estuary systems through a recent decision that all wetland systems (including mangroves) are subject to the National Environmental Standards under the NPS-FM (Campbell Citation2021). The implications of this decision for mangrove management remain to be seen.

A present, each regional council/unitary authority creates specific policies, plans and rules regarding activities that are permitted and those which require consent. This has led to regional variation in coastal management and many councils have changed their approach as the mangrove removal debate evolved over the last two decades (), and as knowledge gaps were filled. Each revised plan or variation to an existing plan has re-energised the debate and highlighted that the key differences underlying the mangrove debate are the positions held, and the changing context, as much as the mangroves themselves. Thus a multiplicity of approaches has prevailed both over space and time.

Table 1. Summary of council positions and controls over mangrove removal.

Evolving scientific knowledge of mangrove ecosystems

In 2000, there were significant gaps in scientific knowledge that were filled (in the absence of other data) by overseas research in tropical mangrove systems. Various authors provide a detailed overview of the biology and ecology of the Aotearoa NZ mangrove (Morrisey et al. Citation2010; Lundquist et al. Citation2014b), and substantial research on key roles and services such as trophic roles, productivity, and carbon sequestration have been described in the last decade (Gladstone-Gallagher et al. Citation2014a; Gladstone-Gallagher et al. Citation2014b; Bulmer et al. Citation2016a; Bulmer et al. Citation2016b).

Interestingly, relevant scientific knowledge has evolved along with perceived risks, following unanticipated outcomes of prior consents. Initial consent information and the required monitoring conditions focussed on anticipated risks to conservation values (i.e. impacts on shorebirds) and short-term impacts of sediment transport from removal areas on neighbouring estuarine habitats (seagrass meadows, shellfish beds) (Bay of Plenty Regional Council consents #65505 and 65693). Many estuary care groups in Tauranga Harbour monitored sediment erosion from removal sites, and at Pahurehure Inlet No. 2, the consent to Papakura District Council required extensive monitoring of water column turbidity (Coffey Citation2010). Following degraded health of mud and sandflats following mechanical mulching (Lundquist Citation2012; Lundquist et al. Citation2012), different approaches to monitoring were initiated by Waikato Regional Council, including a triggers and trends approach that identified several likely environmental impacts based on what occurred in Tauranga Harbour (Bulmer et al. Citation2017). New perceived risks were to health via odour and presence of hydrogen sulphide, and to soft sediment fauna and flora through anoxic conditions, nutrient enrichment from decomposing mangrove biomass, and associated sea lettuce blooms, and other conditions resulting in long-term degradation of intertidal sand and mudflats.

We present here the nuances and complexity of the evolving scientific argument for and against mangrove removal, rather than a detailed description of their role and function. A key challenge has been the polarity based on global understanding of tropical mangrove ecosystems as productive, high-value ecosystems that support diverse faunal and floral biodiversity, and often opposing community perceptions of low value, muddy habitats that are expanding. The key differences between tropical mangrove ecosystems and Aotearoa NZ mangrove ecosystems are that: (1) Mangroves are expanding their habitat in Aotearoa NZ. Rates vary between and within estuaries, with average rates of 3–4% per annum seen across decades (Morrisey et al. Citation2010; Suyadi et al. Citation2019); (2) Mangroves in tropical ecosystems are usually in decline due to a number of pressures; (3) Unlike tropical mangroves, Aotearoa NZ mangroves have no fauna or flora that are dependent solely on mangroves, they are not associated with high biodiversity, and they do not have a role as fish nurseries. This creates a tension between ‘accepted’ international mangrove literature and practices, and the NZ experience.

Can mangroves be removed without harm? Will the sand return? There are assumptions by proponents of mangrove removals that when mangroves are removed that sandy beaches will return. A review of over 40 Aotearoa NZ removal sites, varying in age from <6 months to >15 years post-removal suggests that few removals were successful in their objectives of returning recreational and aesthetic value (Lundquist et al. Citation2014a; Lundquist et al. Citationunpublished manuscript). However, adaptive management approaches have resulted in successful, but slow change toward sandier habitats in at least two Coromandel estuaries (Bulmer et al. Citation2017).

In summary

The mangrove removal debate is set within a complex social, cultural, economic and environmental landscape of ongoing change. Values associated with the changing landscape began to collide in the early 1990s when reports first appeared of expanding mangrove populations impacting some peoples’ use values associated with estuaries and began to pose a risk to things of value. Indeed, the status of mangroves as an expanding indigenous plant species has caused consternation and ambiguity through plans and policy discussion and documents. Science knowledge has settled some questions but generated others.

Next, we explore the perceptions of risk that have been assembled over time by the opponents and proponents of mangrove removal.

Risk perception-based arguments for and against mangrove removal

Distinct and ubiquitous positions and perceptions of risk have been constructed in local contexts regarding mangrove expansion and removal. We have generalised and simplified these positions and illustrated both the perceived risk of mangrove removal and retention through a series of examples ().

Table 2. Perceptions of the risks posed by mangroves (compiled from Harty (Citation2009), Prasad and Loren (Citation2012), DeLuca (Citation2015), Maxwell (Citation2018), Baker (Citation2018), Dencer-Brown et al. (Citation2019) and Neilson (Citation2019)).

The pro-mangrove argument regards mangroves as a desirable, natural, native ecosystem, the removal of which presents a risk to the services and value provided by mangroves to humans and other species. For people holding these views, mangrove removal creates a significant risk to biodiversity, conservation efforts and the ecology and mauri of the estuary system, as well as creating aesthetic risks (visual and odour). Dencer-Brown et al. (Citation2019) suggest that these views and their perceived risks are held strongly by conservation organisations who typically hold a similar worldview (refer to ). The desired outcome for these groups is a functioning natural system based around mangroves.

The pro-removal argument regards the risk of mangroves as an invasive (albeit native) species that has limited ecological value and is expanding beyond its normal range, creating ongoing risk to how the beach ‘should be’ – that is sandy and accessible for water-based recreation. Positionality appears to play a considerable role. Proponents of this view are commonly local community groups, often with long associations with place (place attachment), historical knowledge and experience and desired outcome (Dencer-Brown et al. Citation2019). World views and disciplinary training seem less relevant (refer to ).

Hapū/iwi are more likely to consider the perceived risks of mangrove removal or non-removal by exploring the potential impacts on the mauri (well-being) of the ecosystem and also consider the potential impacts on estuarine systems by land-use activities within the entire catchment. This approach is encapsulated in the whakatauki (proverbial saying) ;ki uta ki tai – from the mountains to the sea’ and reinforces a holistic place-based approach to resource management (Harmsworth et al. Citation2013). It is grounded in a Te Ao Māori worldview (see ) but applied locally. Furthermore, Māori perspectives of environmental risk are inherently holistic, multi-dimensional, interconnected, ecosystem-focused and values-based, and can be used to guide more ethical and moral risk assessments (Harmsworth et al. Citation2013). However, there are large gaps in the literature regarding Māori perspectives of environmental risk and a significant need for ongoing research in this area. Hikuroa et al. (Citation2019) have provided examples of mātauranga Māori relevant for hazard management and have demonstrated how mātauranga Māori and science help prepare communities in the event of natural disasters. However, there remains a need to explore specific notions and applications of risk within individual environmental contexts such as the potential risk of activities on the mauri (well-being) of taonga (culturally important species) like fish and shellfish.

There has been a considerable change over the last 20 years in council and scientific response. Councils and planners/policy makers were previously pro-removal, whereas now they are increasingly middle-ground. Scientists, who were initially reluctant to support mangrove removal activities, also now tend to accept the view that some mangroves could be removed, provided removal is carefully undertaken on a case-by-case basis and is informed by an assessment of effects. Co-governance arrangements are also coming into play now in a way that wasn’t a factor twenty years ago (see ). However, data on the risks/benefits of removal to other ecosystems remains incomplete, and whether the sand will return is still unknown. Councils and planners/policy makers and scientists group appear less affected by positionality and attachment to a particular physical location but more by world view and disciplinary knowledge.

The riskscape has changed. Yet, the very different perceptions and relative weightings of the risks and benefits of mangrove removal continue to play a significant role in shaping practice (see ), even as the riskscape evolves.

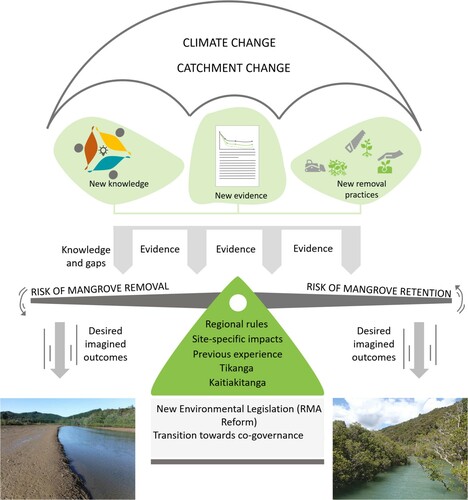

To remove or to leave? What factors have influenced the outcomes?

Resource consent applications for mangrove removal have been granted and declined over the last 20 years. Each decision is part of an evolving storyline where mangrove expansion has continued due to on-going landscape change, coastal property values have increased, regional plans and policy have evolved, science knowledge has continued to advance, and many hapū/iwi have continued to pursue estuary co-management arrangements. The arguments presented by proponents and opponents of mangrove removal have kept pace with these shifting contexts. However, climate change, ongoing shifts in land-use and land-use practices, and the RMA reform will create further change to these contexts.

The balance of factors has a strong temporal element because future decisions will be cognisant of new knowledges, new removal practices, co-management arrangements and deeper understanding of estuary ecosystems. In particular, as scientific knowledge regarding the balance of risk and benefits develops, this may challenge the perception that the beach/estuary will return to a ‘more desired state’ with less risk to use and value. Unsurprisingly, the mangrove removal debate will probably remain a poor choice of barbecue conversation because of the collision of different risk perceptions.

Will a changing climate change shift the mangrove removal debate again?

Several questions arise when considering the role of mangroves in a warming world with on-going sea-level rise that may shift the balance of the mangrove removal debate. Model projections suggest that mangrove habitats may decrease, or may increase, depending on how sea-level rise interacts with changing land use and restoration projects that reduce sediment inputs to coastal and estuarine ecosystems (McBride et al. Citation2016; Rouse et al. Citation2017). Blue carbon or carbon sequestration by estuarine and coastal habitats is being explored for potential inclusion in national climate change mitigation strategies, which could also influence perceptions of the ‘cost’ of mangrove removal; at present, mangroves are neither included for their carbon sequestration benefits, or for costs within the emissions trading scheme (Lundquist et al. Citation2011). Elsewhere, other habitats are perceived to be at risk from mangrove expansion (i.e. shoreward salt marsh habitats), and temperate mangrove expansion in the United States and Australia is seen to be a risk to these other habitats. In Aotearoa NZ, long-term studies of mangrove expansion suggest most of the expansion is seaward, and that risks to saltmarsh habitats to date are limited, however, this could change with sea-level rise resulting in shoreward expansion of mangroves (McBride et al. Citation2016). Mangroves are also likely to have increasing value for coastal protection and reducing sediment erosion in future climates (Lundquist et al. Citation2011; Rouse et al. Citation2017). Will a changing climate alter the perceptions of risk once more and change the way the species is viewed and managed? What will our future relationships with the estuaries be as they shift and change?

Will changing legislation shift the mangrove removal debate again?

Forthcoming RMA reform and the impact of the National Freshwater Standards (NFS) and National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM) will likely have implications for future mangrove management - yet these all remain to be seen.

Conclusion

We argue that exposing the different underlying perceptions of risk associated with mangrove removal and setting it in an evolving storyline of changing landscapes and knowledge begins to explain the spatial and temporal divergence of the outcomes of consent applications. Essentially the role of risk perception in decision-making is strong and often squares proponents and opponents of mangrove removal off against each other because they both have different desired imagined futures for which mangrove are either a threat or a valuable component (). Ambiguity (or gaps) in science knowledge and policy further exacerbates the influence of risk perception.

Figure 4. Current and future factors that influence the outcome of mangrove removal consent application.

Importantly, the paper has demonstrated several relevant considerations for forward-looking holistic estuary management that requires our attention as researchers and practitioners.

First, where governance or knowledge is incomplete and evolving, risk perception and the risk of action on the desired imagined state of the estuary will have a strong influence on the decision-making process. These need exposing and carefully navigating so that more collective futures/outcomes can be imagined.

Second, risk perceptions based on worldview, positionality and discipline underpin the differences in risk perception and are often hidden among other arguments. These should be made visible for informed debate and to avoid disagreement hidden in competing sets of evidence. Positionality is a particular strong factor at the local level.

Third, holistic estuary management will not reach a stable end point – it will be a journey that is continually negotiated between multiple groups because of the ever-shifting context (e.g. climate change and use-change and new governance arrangements) and the emergence of new information – in essence, a more adaptive management strategy. We suggest that the changes in risk perceptions as our estuary systems change and transition is a fruitful new area for research.

Finally, intentions for holistic estuary management will continue to face significant challenges from risk perceptions informed by positionality, particularly when locally important (or desired imagined) outcomes are at stake. If we are to avoid piecemeal localised solutions and transition to cohesive long-term pathways for estuary management, this needs attention.

Overall, the mangrove management debate is set within an evolving storyline of changing landscapes, governance and knowledge that has caused a spatial and temporal divergence of the outcomes of consent applications at a local scale. In particular, because science knowledge is incomplete, inconclusive or not trusted, risk perception underpinned by world view, disciplinary views and positionally plays a significant role in the decision-making process. Lessons from the mangrove removal story for holistic forward-looking estuary management include the need to pay attention to risk perception and the competition between different imagined desired futures; avoiding localised solutions driven by positionality and moving towards more collective larger-scale initiatives inspired by ki uta ki tai ‘mountains to the sea’ concepts; and adopting an adaptive management approach that accepts the evolving story of estuary management in a continually changing world.

Acknowledgements

The authors' contributions were funded by Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge project 3.1 Perceptions of Risk and Uncertainty however, CJL’s contribution was funded by Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge project #UOA20203 ‘Ecological responses to cumulative effects’. We thank Nidhi Yogesh (Figures 2, 3 and 4) and Eva Leunissen (Figure 1) for figure preparation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Auckland Council. 2011. Mangrove management options for the Auckland Council. Auckland Council.

- Auckland Council. 2021a. Auckland Council Regional Plan – Coastal https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/district-and-regional-plans/regional-plans/regional-plan-coastal/Pages/regional-plan-coastal-text.aspx.

- Auckland Council. 2021b. Former Regional Plans https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/district-and-regional-plans/regional-plans/Pages/default.aspx.

- Baker J. 2018. Mudlarks celebrate nine years and 25 hectares of cleared mangroves. Stuff.co.nz, Stuff.

- Bay of Plenty Regional Council. 2019. Bay of Plenty Regional Coastal Environment Plan. https://atlas.boprc.govt.nz/api/v1/edms/document/A3794251/content.

- Blackett P, Hume T, Dahm J. 2010. Exploring the social context of coastal erosion management in New Zealand: what factors drive environmental outcome. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies. 1.

- Blackett P, Awatere S, Le Heron R, Logie J, Hyslop J, Le Heron E. 2021. Why are we always arguing about risk? NZ Marine Sciences Society Conference. July 6–9th 2021. Tauranga.

- Bulmer RH, Lewis M, O’Donnell E, Lundquist CJ. 2017. Assessing mangrove clearance methods to minimise adverse impacts and maximise the potential to achieve restoration objectives. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 51:110–126.

- Bulmer RH, Schwendenmann L, Lundquist CJ. 2016a. Allometric models for estimating aboveground biomass, carbon and nitrogen stocks in temperate Avicennia marina forests. Wetlands. 36:841–848.

- Bulmer RH, Schwendenmann L, Lundquist CJ. 2016b. Carbon and nitrogen stocks and below-ground allometry in temperate mangroves. Frontiers in Marine Science. 3:150.

- Campbell J. 2021. Minister of Conservation V Mangawhai Harbour Restoration Society Incorporated. High Court.

- Coffey B. 2010. During clearance and immediate post clearance ecological monitoring to meet Condition 6 of Permit 35053 that authorises Papakura District Council to clear mangroves from Pahurehure Inlet No. 2. Client report prepared for Auckland Regional Council on behalf of Papakura District Council.

- Crisp P, Daniel L, Tortell P. 1990. Mangroves in New Zealand: trees in the tide. Wellington: GP Books.

- DeLuca S. 2015. Mangroves in NZ – misunderstandings and management. Coasts and Ports Ports Conference Pullman Hotel, Auckland.

- Dencer-Brown AM, Alfaro A, Milne S, Perrott J. 2018. A review on biodiversity, ecosystem services, and perceptions of New Zealand’s mangroves: can we make informed decisions about their removal? Resources. 7:23.

- Dencer-Brown AM, Alfaro AC, Milne S. 2019. Muddied waters: perceptions and attitudes towards mangroves and their removal in New Zealand. Sustainability. 11:2631.

- Dingwall PR. 1984. Overcoming problems in the management of New Zealand mangrove forests. In: Teas HJ, editor. Physiology and management of mangroves. The Hague: Dr W. Junk Publishers; p. 97–106.

- Dunlap RE, Liere K. 1984. Commitment to the dominant social paradigm and concern for environmental quality. Soical Science Quarterly. 65:1013–1028.

- Dunlap RE, Van Liere KD, Mertig AG, Jones RE. 2000. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues. 56:425–442.

- Fonterra Co-operative Group, Regional Councils, Ministry for the Environment, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 2003. Dairying and Clean Streams Accord.

- Friess DA, Krauss KW, Horstman EM, Balke T, Bouma TJ, Galli D, Webb EL. 2012. Are all intertidal wetlands naturally created equal? Bottlenecks, thresholds and knowledge gaps to mangrove and saltmarsh ecosystems. Biological Reviews. 87:346–366.

- Gladstone-Gallagher RV, Lundquist CJ, Pilditch CA. 2014a. Mangrove (Avicennia marina subsp. australasica) litter production and decomposition in a temperate estuary. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 48:24–37.

- Gladstone-Gallagher RV, Lundquist CJ, Pilditch CA. 2014b. Response of temperate intertidal benthic assemblages to mangrove detrital inputs. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 460:80–88.

- Harmsworth G, Awatere S, Robb M. 2016. Indigenous Maori values and perspectives to inform freshwater management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ecology and Society. 21:497–510.

- Harmsworth GR, Awatere S, Dymond JR. 2013. Indigenous Māori knowledge and perspectives of ecosystems. In: Dymond JR, editor. Ecosystem services in New Zealand – conditions and trends. Lincoln: Manaaki Whenua Press; p. 59–79.

- Harty C. 2009. Mangrove planning and management in New Zealand and south east Australia – a reflection on approaches. Ocean & Coastal Management. 52:278–286.

- Hikuroa D, King D, Forsman X. 2019. How indigenous knowledge can reduce risk, facilitate recovery and increase resilience. Earth and Space Science Open Archive 1.

- Horstman EM, Lundquist CJ, Bryan KR, Bulmer RH, Mullarney JC, Stokes DJ. 2018. The dynamics of expanding mangroves in New Zealand. In: Makowski C, Finkl CW, editor. Threats to mangrove forests: hazards, vulnerability, and management. Coastal Research Library. Springer International Publishing; p. 23–51. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73016-5_2.

- Integrated Kaipara Harbour Management Group. 2022. Creating a healthy and productive Kaipara Harbour; [accessed 2022 Feb 3]. https://www.kaiparaharbour.net.nz/.

- Khodabakhshi B. 2017. Benefits, co-benefits and policy implications of restoring coastal wetlands in Auckland: a climate change perspective. Auckland University.

- Le Heron R, Le Heron E PB, Logie J, Awatere S, Hyslop J. submitted. Why do we argue about risk? The invisibility of worldviews in marine decision-making.

- Lundquist C. 2012. Appeals against decisions by BOPRC in relation to the Coastal Environment (Mangrove Management) sections of the Proposed Bay of Plenty Regional Policy Statement (ENV-2012-AKL-000078). Environment Court, Appeals pursuant to Clause 14 of the First Schedule of the Resource Management Act (1991).

- Lundquist C, Hails S, Cartner K, Carter K, Gibbs M. 2012. Physical and ecological impacts associated with mangrove removals using in situ mechanical mulching in Tauranga Harbour. Niwa NIWA technical report; 137. 106 p.

- Lundquist CJ, Hailes S, Carter K, Burgess T. 2014a. Ecological status of mangrove removal sites in the Auckland Region. Prepared by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research for Auckland Council. Auckland Council technical report, TR2014/033 97 p.

- Lundquist CJ, Hailes SF, Carter KJ, Cartner K. Bulmer RH unpublished manuscript. long-term trends in recovery after mangrove removal in Aotearoa New Zealand. Frontiers in Forest and Global Change.

- Lundquist CJ, Morrisey DJ, Gladstone-Gallagher RV, Swales A. 2014b. Managing mangrove habitat expansion in New Zealand. In: Faridah-Hanum I, Latiff A, Hakeem KR, Ozturk M, editor. Mangrove ecosystems of Asia. New York: Springer; p. 415–438.

- Lundquist CJ, Ramsay D, Bell R, Swales A, Kerr S. 2011. Predicted impacts of climate change on New Zealand's biodiversity. Pacific Conservation Biology. 17:179–191.

- Makey L, Awatere S. 2018. He Mahere Pāhekoheko Mō Kaipara Moana–Integrated Ecosystem-Based Management for Kaipara Harbour, Aotearoa New Zealand. Society & Natural Resources. 31:1400–1418.

- Maxwell GS. 2018. Mangroves are assets to the many but a curse to the few – polarised perceptions in New Zealand. ISME/GLOMIS Electronic Journal. 16:19–24.

- Maxwell K, Awatere S, Ratana K, Davies K, Taiapa C. 2020a. He waka eke noa/we are all in the same boat: A framework for co-governance from aotearoa New Zealand. Marine Policy. 121:104213.

- Maxwell KH, Ratana K, Davies KK, Taiapa C, Awatere S. 2020b. Navigating towards marine co-management with indigenous communities on-board the Waka-Taurua. Marine Policy. 111:103722.

- McBride G, Reeve G, Pritchard M, Lundquist C, Daigneault A, Bell R, Blackett P, Swales A, Wadhwa S, Tait A, Zammit C. 2016. The Firth of Thames and Lower Waihou River. Synthesis Report RA2, Coastal Case Study. Climate Changes, Impacts and Implications (CCII) for New Zealand to 2100. . MBIE contract C01X1225. 50 p.

- Morrisey DJ, Swales A, Dittmann S, Morrison MA, Lovelock CE, Beard CM. 2010. The ecology and management of temperate mangroves. Oceanography and Marine Biology. 48:43–160.

- Neilson M. 2019. To mangrove or not to mangrove? Forest & Bird ‘shocked’ over Auckland Council support for Waiuku project. New Zealand Herald. Auckland.

- New Zealand Parliament. 2018. Thames–Coromandel District Council and Hauraki District Council Mangrove Management Bill (Local Bill). As reported from the Governance and Administration Committee https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/SCR_81030/5800e3e437fe2340e5f5cb218dbefba0472ee311.

- Northland Regional Council. 2021. Proposed Regional Plan for Northland Appeal Version. https://www.nrc.govt.nz/media/3ksmwkh5/proposed-regional-plan-updated-appeals-version-november-2021.pdf. 2022.

- Northland Regional Council. 2022. Regional Coastal Plan https://www.nrc.govt.nz/resource-library-summary/plans-and-policies/regional-plans/regional-coastal-plan. Whangarei.

- Peart R. 2009. Castles in the sand: what is happening to the New Zealand coast? Nelson: CraigPotton Publishing.

- Prasad V, Loren A. 2012. Community split over mangroves. Western Leader. Auckland.

- Rouse HL, Bell RG, Lundquist CJ, Blackett PE, Hicks DM, King DN. 2017. Coastal adaptation to climate change in Aotearoa-New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 51:183–222.

- Rout M, Awatere S, Mika JP, Reid J, Roskruge M. 2021. A Māori approach to environmental economics: te ao tūroa, te ao hurihuri, te ao mārama—the old world, a changing world, a world of light. Oxford University Press.

- Smith A. 2018. Mangrove management and how to remove them. Auckland: New Zealand Herald.

- Spalding M, Kainuma M, Collins L. 2010. World atlas of mangroves. London: Earthscan.

- Suyadi GJ, Lundquist CJ, Schwendenmann L. 2019. Land-based and climatic stressors of mangrove cover change in the Auckland Region, New Zealand. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 29:1466–1483.

- Swales A, Bell RG, Gorman R, Oldman JW, Altenberger A, Hart C, Claydon L, Wadhwa S, Ovenden R. 2008. Potential future changes in mangrove-habitat in Auckland's east-coast estuaries. Auckland Regional Council Technical Report no. 079 June 2009 TR079.

- Swales A, Bentley SJ, Lovelock CE. 2015. Mangrove-forest evolution in a sediment-rich estuarine system: opportunists or agents of geomorphic change? Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 40:1672–1687.

- Te Korowai o te Tai ō Marokura. 2012. Kaikoura marine strategy 2012: Sustaining our sea; [accessed 2019 Jun 1]. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE14833036.

- Thames Coromandel District Council. 2017. Have your say. https://www.tcdc.govt.nz/Have-Your-Say/Closed-Consultations/TCDC-and-HDC-Mangrove-Management-Bill-2017/.

- Thomson J. 2013. New ecological paradigm survey 2008: analysis of the NEP results. Waikato Regional Council 74 p.

- Waikato Regional Council. 2017. Sea Change – Tai Timu Tai Pari: Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan Hamilton, New Zealand, Waikato Regional Council.

- Waikato Regional Council. 2019a. Coastal Plan Review – Policy directions paper https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/assets/WRC/WRC-2019/RCPreview-Policy-Direction-Papers.pdf.

- Waikato Regional Council. 2019b. Managing mangroves https://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/services/regional-services/river-and-catchment-management/catchment-management-zone-map/your-catchment-coromandel-zone/looking-forward-to-a-healthier-harbour-in-whangamata/whangamata-mangrove-management.

- Walters T. 2019. Caves to castles: the development of second home practices in New Zealand. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events. 11:1–15.

- Warf B. 2010. Encyclopedia of geography. SAGE Publications.

- Win R, Park S, Quinn A. 2015. Tauranga Harbour Mangrove Management Literature Review. Bay of Plenty Regional Council 20 p.